Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 FEB 2022

Ethics is about engaging in conversations to understand different perspectives and ways in which we can approach the world.

Which means we need a range of people participating in the conversation.

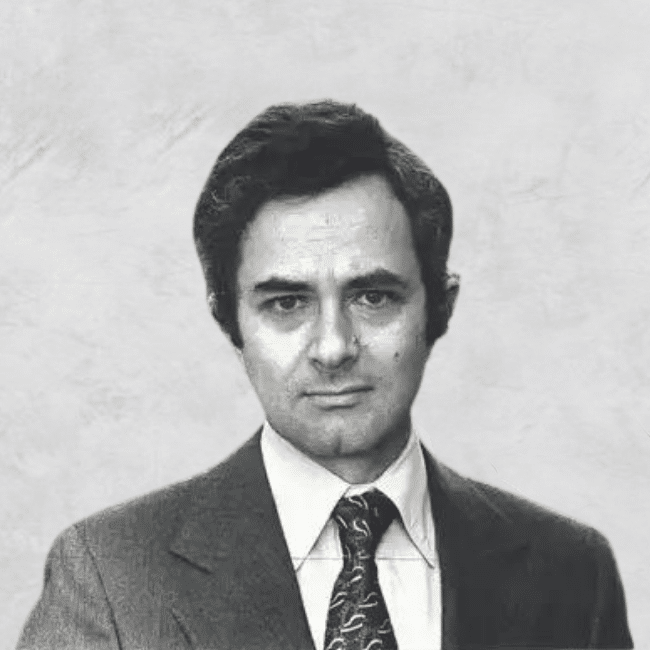

That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Dr Tim Dean as our Senior Philosopher. An award-winning philosopher, writer, speaker and honorary associate with the University of Sydney, Tim has developed and delivered philosophy and emotional intelligence workshops for schools and businesses across Australia and the Asia Pacific, including Meriden and St Mark’s high schools, The School of Life, Small Giants and businesses including Facebook, Commonwealth Bank, Aesop, Merivale and Clayton Utz.

We sat down with Tim to discuss his views on morality, social media, cancel culture and what ethics means to him.

What drew you to the study of philosophy?

Children are natural philosophers, constantly asking “why?” about everything around them. I just never grew out of that tendency, much to the chagrin of my parents and friends. So when I arrived at university, I discovered that philosophy was my natural habitat, furnishing me with tools to ask “why?” better, and revealing the staggering array of answers that other thinkers have offered throughout the ages. It has also helped me to identify a sense of meaning and purpose that drives my work.

What made you pursue the intersection of science and philosophy?

I see science and philosophy as continuous. They are both toolkits for understanding the world around us. In fact, technically, science is a sub-branch of philosophy (even if many scientists might bristle at that idea) that specialises in questions that are able to be investigated using empirical tools, hence its original name of “natural philosophy”. I have been drawn to science as much as philosophy throughout my life, and ended up working as a science writer and editor for over 10 years. And my study of biology and evolution transformed my understanding of morality, which was the subject of my PhD thesis.

How does social media skew our perception of morals?

If you wanted to create a technology that gave a distorted perception of the world, that encouraged bad faith discourse and that promoted friction rather than understanding, you’d be hard pressed to do better than inventing social media. Social media taps into our natural tendencies to create and defend our social identity, it triggers our natural outrage response by feeding us an endless stream of horrific events, it rewards us with greater engagement when we go on the offensive while preventing us from engaging with others in a nuanced way. In short, it pushes our moral buttons, but not in a constructive way. So even though social media can do good, such as by raising awareness of previously marginalised voices and issues, overall I’d call it a net negative for humanity’s moral development.

How do you think the pandemic has changed the way we think about ethics?

The COVID-19 pandemic has both expanded and shrunk our world. On the one hand, lockdowns and border closures have grounded us in our homes and our local communities, which in many cases has been a positive thing, as people get to know their neighbours and look out for each other. But it has also expanded our world as we’ve been stuck behind screens watching a global tragedy unfold, often without any real power to fix it. But it has also made us more sensitive to how our individual actions affect our entire community, and has caused us to think about our obligations to others. In that sense, it has brought ethics to the fore.

Tell us a little about your latest book ‘How We Became Human, And Why We Need to Change’?

I’ve long been fascinated by the story of how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today. Morality has played a key part in that story, helping us to have empathy for others, motivating us to punish wrongdoing and giving us a toolkit of moral norms that can guide our community’s behaviour. But in studying this story of moral evolution, I came to realise that many of the moral tendencies we have and many of the moral rules we’ve inherited were designed in a different time, and they often cause more harm than good in today’s world. My book explores several modern problems, like racism, sexism, religious intolerance and political tribalism, and shows how they are all, in part, products of our evolved nature. I also argue that we need to update our moral toolkit if we want to live and thrive in a modern, globalised and diverse world, and that means letting go of past solutions and inventing new ones.

How do you think the concepts of right and wrong will change in the coming years?

The world is changing faster than ever before. It’s also more diverse and fragmented than ever before. This means that the moral rules that we live by and the values that drive us are also changing faster than ever before – often faster than many people can keep up. Moral change will only continue, especially as new generations challenge the assumptions and discard the moral baggage of past generations. We should expect that many things we took for granted will be challenged in the coming decades. I foresee a huge challenge in bringing people along with moral change rather than leaving them behind.

What are your thoughts on the notion of ‘cancel culture’?

There are no easy answers when it comes to the limits of free speech. We value free speech to the degree that it allows us to engage with new ideas, seek the truth and to be able to express ourselves and hear from others. But that speech comes at a cost, particularly when it allows bad faith speech to spread misinformation, to muddy the truth, or dehumanise others. There are some types of speech that ought to be shut down, but we must be careful how the power to shut down speech is used. In the same way that some speech can be in bad faith, so too can be efforts to shut it down. Some instances of “cancelling” might be warranted, but many are a symptom of mob culture that seeks to silence views the mob opposes rather than prevent bad kinds of speech. Sometimes it’s motivated by a sense that a speaker is not just mistaken but morally corrupt, which prevents people from engaging with them and attempting to change their views. This is why one thing I advocate strongly for is rebuilding social capital, or the trust and respect that enables good faith discourse to occur at all. It’s only when we have that trust and respect that we will be able to engage in good faith rather than feel like we need to resort to cancelling or silencing people.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Ethics is what makes our species unique. No other creature can live alongside and cooperate with other individuals on the scale that we do. This is all made possible by ethics, which is our ability to consider how we ought to behave towards others and what rules we should live by. It’s our superpower, it’s what has enabled our species to spread across the globe. But understanding and engaging with ethics, figuring out our obligations to others, and adapting our sense of right and wrong to a changing world, is our greatest and most enduring challenge as a species.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

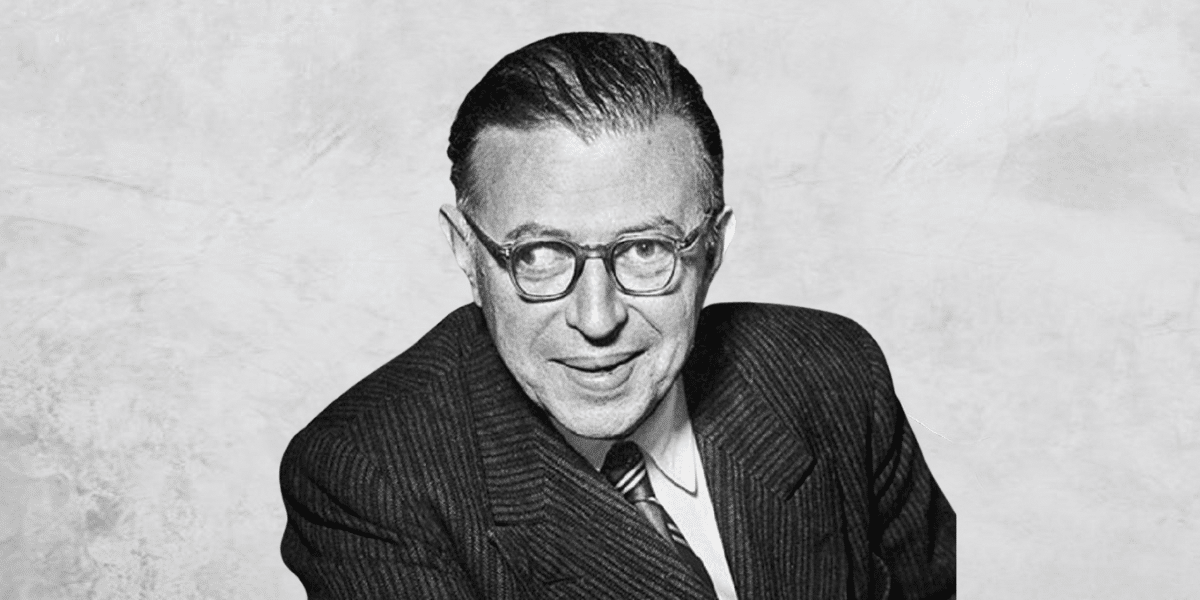

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) is one of the best known philosophers of the 20th century, and one of few who became a household name. But he wasn’t only a philosopher – he was also a provocative novelist, playwright and political activist.

Sartre was born in Paris in 1905, and lived in France throughout his entire life. He was conscripted during the war, but was spared the front line due to his exotropia, a condition that caused his right eye to wander. Instead, he served as a meteorologist, but was captured by German forces as they invaded France in 1940. He spent several months in a prisoner of war camp, making the most of the time by writing, and then returned to occupied Paris, where he remained throughout the war.

Before, during and after the war, he and his lifelong partner, the philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir, were frequent patrons of the coffee houses around Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. There, they and other leading thinkers of the time, like Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, cemented the cliché of bohemian thinkers smoking cigarettes and debating the nature of existence, freedom and oppression.

Sartre started writing his most popular philosophical work, Being and Nothingness, while still in captivity during the war, and published it in 1943. In it, he elaborated on one of his core themes: phenomenology, the study of experience and consciousness.

Learning from experience

Many philosophers who came before Sartre were sceptical about our ability to get to the truth about reality. Philosophers from Plato through to René Descartes and Immanuel Kant believed that appearances were deceiving, and what we experience of the world might not truly reflect the world as it really is. For this reason, these thinkers tended to dismiss our experience as being unreliable, and thus fairly uninteresting.

But Sartre disagreed. He built on the work of the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl to focus attention on experience itself. He argued that there was something “true” about our experience that is worthy of examination – something that tells us about how we interact with the world, how we find meaning and how we relate to other people.

The other branch of Sartre’s philosophy was existentialism, which looks at what it means to be beings that exist in the way we do. He said that we exist in two somewhat contradictory states at the same time.

First, we exist as objects in the world, just as any other object, like a tree or chair. He calls this our “facticity” – simply, the sum total of the facts about us.

The second way is as subjects. As conscious beings, we have the freedom and power to change what we are – to go beyond our facticity and become something else. He calls this our “transcendence,” as we’re capable of transcending our facticity.

However, these two states of being don’t sit easily with one another. It’s hard to think of ourselves as both objects and subjects at the same time, and when we do, it can be an unsettling experience. This experience creates a central scene in Sartre’s most famous novel, Nausea (1938).

Freedom and responsibility

But Sartre thought we could escape the nausea of existence. We do this by acknowledging our status as objects, but also embracing our freedom and working to transcend what we are by pursuing “projects.”

Sartre thought this was essential to making our lives meaningful because he believed there was no almighty creator that could tell us how we ought to live our lives. Rather, it’s up to us to decide how we should live, and who we should be.

“Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.”

This does place a tremendous burden on us, though. Sartre famously admitted that we’re “condemned to be free.” He wrote that “man” was “condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.”

This radical freedom also means we are responsible for our own behaviour, and ethics to Sartre amounted to behaving in a way that didn’t oppress the ability of others to express their freedom.

Later in life, Sartre became a vocal political activist, particularly railing against the structural forces that limited our freedom, such as capitalism, colonialism and racism. He embraced many of Marx’s ideas and promoted communism for a while, but eventually became disillusioned with communism and distanced himself from the movement.

He continued to reinforce the power and the freedom that we all have, particularly encouraging the oppressed to fight for their freedom.

By the end of his life in 1980, he was a household name not only for his insightful and witty novels and plays, but also for his existentialist phenomenology, which is not just an abstract philosophy, but a philosophy built for living.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Research shows that physical appearance can affect everything from the grades of students to the sentencing of convicted criminals – are looks and morality somehow related?

Ancient philosophers spoke of beauty as a supreme value, akin to goodness and truth. The word itself alluded to far more than aesthetic appeal, implying nobility and honour – it’s counterpart, ugliness, made all the more shameful in comparison.

From the writings of Plato to Heraclitus, beautiful things were argued to be vital links between finite humans and the infinite divine. Indeed, across various cultures and epochs, beauty was praised as a virtue in and of itself; to be beautiful was to be good and to be good was to be beautiful.

When people first began to ask, ‘what makes something (or someone) beautiful?’, they came up with some weird ideas – think Pythagorean triangles and golden ratios as opposed to pretty colours and chiselled abs. Such aesthetic ideals of order and harmony contrasted with the chaos of the time and are present throughout art history.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c.1490

These days, a more artificial understanding of beauty as a mere observable quality shared by supermodels and idyllic sunsets reigns supreme.

This is because the rise of modern science necessitated a reappraisal of many important philosophical concepts. Beauty lost relevance as a supreme value of moral significance in a time when empirical knowledge and reason triumphed over religion and emotion.

Yet, as the emergence of a unique branch of philosophy, aesthetics, revealed, many still wondered what made something beautiful to look at – even if, in the modern sense, beauty is only skin deep.

Beauty: in the eye of the beholder?

In the ancient and medieval era, it was widely understood that certain things were beautiful not because of how they were perceived, but rather because of an independent quality that appealed universally and was unequivocally good. According to thinkers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, this was determined by forces beyond human control and understanding.

Over time, this idea of beauty as entirely objective became demonstrably flawed. After all, if this truly were the case, then controversy wouldn’t exist over whether things are beautiful or not. For instance, to some, the Mona Lisa is a truly wonderful piece of art – to others, evidence that Da Vinci urgently needed an eye check.

Consequently, definitions of beauty that accounted for these differences in opinion began to gain credence. David Hume famously quipped that beauty “exists merely in the mind which contemplates”. To him and many others, the enjoyable experience associated with the consumption of beautiful things was derived from personal taste, making the concept inherently subjective.

This idea of beauty as a fundamentally pleasurable emotional response is perhaps the closest thing we have to a consensus among philosophers with otherwise divergent understandings of the concept.

Returning to the debate at hand: if beauty is not at least somewhat universal, then why do hundreds and thousands of people every year visit art galleries and cosmetic surgeons in pursuit of it? How can advertising companies sell us products on the premise that they will make us more beautiful if everyone has a different idea of what that looks like? Neither subjectivist nor objectivist accounts of the concept seem to adequately explain reality.

According to philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Francis Hutcheson, the answer must lie somewhere in the middle. Essentially, they argue that a mind that can distance itself from its own individual beliefs can also recognize if something is beautiful in a general, objective sense. Hume suggests that this seemingly universal standard of beauty arises when the tastes of multiple, credible experts align. And yet, whether or not this so-called beautiful thing evokes feelings of pleasure is ultimately contingent upon the subjective interpretation of the viewer themselves.

Looking good vs being good

If this seemingly endless debate has only reinforced your belief that beauty is a trivial concern, then you are not alone! During modernity and postmodernity, philosophers largely abandoned the concept in pursuit of more pressing matters – read: nuclear bombs and existential dread. Artists also expressed their disdain for beauty, perceived as a largely inaccessible relic of tired ways of thinking, through an expression of the anti-aesthetic.

Nevertheless, we should not dismiss the important role beauty plays in our day-to-day life. Whilst its association with morality has long been out of vogue among philosophers, this is not true of broader society. Psychological studies continually observe a ‘halo effect’ around beautiful people and things that see us interpret them in a more favourable light, leading them to be paid higher wages and receive better loans than their less attractive peers.

Social media makes it easy to feel that we are not good enough, particularly when it comes to looks. Perhaps uncoincidentally, we are, on average, increasing our relative spending on cosmetics, clothing, and other beauty-related goods and services.

Turning to philosophy may help us avoid getting caught in a hamster wheel of constant comparison. From a classical perspective, the best way to achieve beauty is to be a good person. Or maybe you side with the subjectivists, who tell us that being beautiful is meaningless anyway. Irrespective, beauty is complicated, ever-important, and wonderful – so long as we do not let it unfairly cloud our judgements.

Step through the mirror and examine what makes someone (or something) beautiful and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for the Ethics of Beauty on Thur 29 Feb 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Kate Manne (1983 – present) is an Australian philosopher who works at the intersection of feminist philosophy, metaethics, and moral psychology.

While Manne is an academic philosopher by training and practice, she is best known for her contributions to public philosophy. Her work draws upon the methodology of analytic philosophy to dissect the interrelated phenomena of misogyny and masculine entitlement.

What is misogyny?

Manne’s debut book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny (2018), develops and defends a robust definition of misogyny that will allow us to better analyse the prevalence of violence and discrimination against women in contemporary society. Contrary to popular belief, Manne argues that misogyny is not a “deep-seated psychological hatred” of women, most often exhibited by men. Instead, she conceives of misogyny in structural terms, arguing that it is the “law enforcement” branch of patriarchy (male-dominated society and government), which exists to police the behaviour of women and girls through gendered norms and expectations.

Manne distinguishes misogyny from sexism by suggesting that the latter is more concerned with justifying and naturalising patriarchy through the spread of ideas about the relationship between biology, gender and social roles.

While the two concepts are closely related, Manne believes that people are capable of being misogynistic without consciously holding sexist beliefs. This is because misogyny, much like racism, is systemic and capable of flourishing regardless of someone’s psychological beliefs.

One of the most distinctive features of Manne’s philosophical work is that she interweaves case studies from public and political life into her writing to powerfully motivate her theoretical claims.

For instance, in Down Girl, Manne offers up the example of Julia Gillard’s famous misogyny speech from October 2012 as evidence of the distinction between sexism and misogyny in Australian politics. She contends that Gillard’s characterisation of then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott’s behaviour toward her as both sexist and misogynistic is entirely apt. His comments about the suitability of women to politics and characterisation of female voters as immersed in housework display sexist values, while his endorsement of statements like “Ditch the witch” and “man’s bitch” are designed to shame and belittle Gillard in accordance with misogyny.

Himpathy and herasure

One of the key concepts coined by Kate Manne is “himpathy”. She defines himpathy as “the disproportionate or inappropriate sympathy extended to a male perpetrator over his similarly, or less privileged, female targets in cases of sexual assault, harassment, and other misogynistic behaviour.”

According to Manne, himpathy operates in concert with misogyny. While misogyny seeks to discredit the testimony of women in cases of gendered violence, himpathy shields the perpetrators of that misogynistic behaviour from harm to their reputation by positioning them as “good guys” who are the victims of “witch hunts”. Consequently, the traumatic experiences of those women and their motivations for seeking justice are unfairly scrutinised and often disbelieved. Manne terms the impact of this social phenomenon upon women, “herasure.”

Manne’s book Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women (2020) illustrates the potency of himpathy by analysing the treatment of Brett Kavanaugh during the Senate Judiciary Committee’s investigation into allegations of sexual assault levelled against Kavanaugh by Professor Christine Blassey Ford. Manne points to the public’s praise of Kavanaugh as a brilliant jurist who was being unfairly defamed by a woman who sought to derail his appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States as an example of himpathy in action.

She also suggests that the public scrutiny of Ford’s testimony and the conservative media’s attack on her character functioned to diminish her credibility in the eyes of the law and erase her experiences. The Senate’s ultimate endorsement of Justice Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court proved Manne’s thesis – that male entitlement to positions of power is a product of patriarchy and serves to further entrench misogyny.

Evidently, Kate Manne is a philosopher who doesn’t shy away from thorny social debates. Manne’s decision to enliven her philosophical work with empirical evidence allows her to reach a broader audience and to increase the accessibility of philosophy for the public. She represents a new generation of female philosophers – brave, bold, and unapologetically political.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical school of thought that, broadly, is interested in the effects and usefulness of theories and claims.

Pragmatism is a distinct school of philosophical thought that began at Harvard University in the late 19th century. Charles Sanders Pierce and William James were members of the university’s ‘Metaphysical Club’ and both came to believe that many disputes taking place between its members were empty concerns. In response, the two began to form a ‘Pragmatic Method’ that aimed to dissolve seemingly endless metaphysical disputes by revealing that there was nothing to argue about in the first place.

How it came to be

Pragmatism is best understood as a school of thought born from a rejection of metaphysical thinking and the traditional philosophical pursuits of truth and objectivity. The Socratic and Platonic theories that form the basis of a large portion of Western philosophical thought aim to find and explain the “essences” of reality and undercover truths that are believed to be obscured from our immediate senses.

This Platonic aim for objectivity, in which knowledge is taken to be an uncovering of truth, is one which would have been shared by many members of Pierce and James’ ‘Metaphysical Club’. In one of his lectures, James offers an example of a metaphysical dispute:

A squirrel is situated on one side of a tree trunk, while a person stands on the other. The person quickly circles the tree hoping to catch sight of the squirrel, but the squirrel also circles the tree at an equal pace, such that the two never enter one another’s sight. The grand metaphysical question that follows? Does the man go round the squirrel or not?

Seeing his friends ferociously arguing for their distinct position led James to suggest that the correctness of any position simply turns on what someone practically means when they say, ‘go round’. In this way, the answer to the question has no essential, objectively correct response. Instead, the correctness of the response is contingent on how we understand the relevant features of the question.

Truth and reality

Metaphysics often talks about truth as a correspondence to or reflection of a particular feature of “reality”. In this way, the metaphysical philosopher takes truth to be a process of uncovering (through philosophical debate or scientific enquiry) the relevant feature of reality.

On the other hand, pragmatism is more interested in how useful any given truth is. Instead of thinking of truth as an ultimately achievable end where the facts perfectly mirror some external objective reality, pragmatism instead regards truth as functional or instrumental (James) or the goal of inquiry where communal understanding converges (Pierce).

Take gravity, for example. Pragmatism doesn’t view it as true because it’s the ‘perfect’ understanding and explanation for the phenomenon, but it does view it as true insofar as it lets us make extremely reliable predictions and it is where vast communal understanding has landed. It’s still useful and pragmatic to view gravity as a true scientific concept even if in some external, objective, all-knowing sense it isn’t the perfect explanation or representation of what’s going on.

In this sense, truth is capable of changing and is contextually contingent, unlike traditional views.. Pragmatism argues that what is considered ‘true’ may shift or multiply when new groups come along with new vocabularies and new ways of seeing the world.

To reconcile these constantly changing states of language and belief, Pierce constructed a ‘Pragmatic Maxim’ to act as a method by which thinkers can clarify the meaning of the concepts embedded in particular hypotheses. One formation of the maxim is:

Consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of those effects is the whole of our conception of the object.

In other words, Pierce is saying that the disagreement in any conceptual dispute should be describable in a way which impacts the practical consequences of what is being debated. Pragmatic conceptions of truth take seriously this commitment to practicality. Richard Rorty, who is considered a neopragmatist, writes extensively on a particular pragmatic conception of truth.

Rorty argues that the concept of ‘truth’ is not dissimilar to the concept of ‘God’, in the way that there is very little one can say definitively about God. Rorty suggests that rather than aiming to uncover truths of the world, communities should instead attempt to garner as much intersubjective agreement as possible on matters they agree are important.

Rorty wants us to stop asking questions like, ‘Do human beings have inalienable human rights?’, and begin asking questions like, ‘Should we work towards obtaining equal standards of living for all humans?’. The first question is at risk of leading us down the garden path of metaphysical disputes in ways the second is not. As the pragmatist is concerned with practical outcomes, questions which deal in ‘shoulds’ are more aligned with positing future directed action than those which get stuck in metaphysical mud.

Perhaps the pragmatists simply want us to ask ourselves: Is the question we’re asking, or hypothesis that we’re posing, going to make a useful difference to addressing the problem at hand? Useful, as Rorty puts it, is simply that which gets us more of what we want, and less of what we don’t want. If what we want is collective understanding and successful communication, we can get it by testing whether the questions we are asking get us closer to that goal, not further away.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Thomas Nagel (1937-present) is an American philosopher whose work has spanned ethics, political philosophy, epistemology, metaphysics (the nature of what exists) and, most famously, philosophy of the mind.

An academic philosopher accessible to the general public, an atheist who doubts the materialist theory of evolution – Thomas Nagel is a considered nuanced professor with a rebellious streak.

Born in Belgrade Yugoslavia (present day Serbia) to German Jewish refugees, Nagel grew up in and around New York. Studying first at Cornell University, then the University of Oxford, he completed his PhD at Harvard University under John Rawls, one of the most influential and respected philosophers of the last century. Nagel has taught at New York University for the last four decades.

Subjectivity and Objectivity

A key theme throughout Nagel’s work has been the exploration of the tension between an individual’s subjective view, and how that view exists in an objective world, something he pursues alongside a persistent questioning of mainstream orthodox theories.

Nagel’s most famous work, What Is It Like to Be a Bat? (1974), explores the tension between subjective (personal, internal) and objective (neutral, external) viewpoints by considering human consciousness and arguing the subjective experience cannot be fully explained by the physical aspects of the brain:

“…every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected with a single point of view, and it seems inevitable that an objective, physical theory will abandon that point of view.”

Nagel’s The View From Nowhere (1986) offers both a robust defence and cutting critique of objectivity, in a book described by the Oxford philosopher Mark Kenny as an ideal starting point for the “intelligent novice [to get] an idea of the subject matter of philosophy”. Nagel takes aim at the objective views that assume everything in the universe is reducible to physical elements.

Nagel’s position in Mind and Cosmos (2012) is that non-physical elements, like consciousness, rationality and morality, are fundamental features of the universe and can’t be explained by physical matter. He argues that because (Materialist Neo-) Darwinian theory assumes everything arises from the physical, its theory of nature and life cannot be entirely correct.

The backlash to Mind and Cosmos from those aligned with the scientific establishment was fierce. However, H. Allen Orr, the American evolutionary geneticist, did acknowledge that it is not obvious how consciousness could have originated out of “mere objects” (though he too was largely critical of the book).

And though Nagel is best known for his work in the area of philosophy of the mind, and his exploration of subjective and objective viewpoints, he has made substantial contributions to other domains of philosophy.

Ethics

His first book, The Possibility of Altruism (1970), considered the possibility of objective moral judgments and he has since written on topics such as moral luck, moral dilemmas, war and inequality.

Nagel has analysed the philosophy of taxation, an area largely overlooked by philosophers. The Myth of Ownership (2002), co-written with the Australian philosopher Liam Murphy, questions the prevailing mainstream view that individuals have full property rights over their pre-tax income.

“There is no market without government and no government without taxes … [in] the absence of a legal system [there are] … none of the institutions that make possible the existence of almost all contemporary forms of income and wealth.”

Nagel has a Doctor of Laws (hons.) from Harvard University, has published in various law journals, and in 1987 co-founded with Ronald Dworkin (the famous legal scholar) New York University’s Colloquium in Legal, Political, and Social Philosophy, described as “the hottest thing in town” and “the centerpiece and poster child of the intellectual renaissance at NYU”. The colloquium is still running today.

Alongside his substantial contributions to academic philosophy, Nagel has written numerous book reviews, public interest articles and one of the best introductions to philosophy. In his book what does it all mean?: a very short introduction to philosophy (1987), Nagel leads the reader through various methods of answering fundamental questions like: Can we have free will? What is morality? What is the meaning of life?

The book is less a list of answers, and more an exploration of various approaches, along with the limitations of each. Nagel asks us not to take common ideas and theories for granted, but to critique and analyse them, and develop our own positions. This is an approach Thomas Nagel has taken throughout his career.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: David Hume

There are few philosophers whose work has ranged over such vast territory as David Hume (1711—1776).

If you’ve ever felt underappreciated in your time, let the story of David Hume console you: despite being one of the most original and profound thinkers of his or any era, the Scottish philosopher never held an academic post. Indeed, he described his magnum opus, A Treatise of Human Nature, as falling “stillborn from the press.” When he was recognized at all during his lifetime, it was primarily as a historian – his multi-volume work on the history of the British monarchy was heralded in France, while in his native country, he was branded a heretic and a pariah for his atheistic views.

Yet, in the many years since his passing, Hume has been retroactively recognised as one the most important writers of the Early Modern era. His works, which touch on everything from ethics, religion, metaphysics, economics, politics and history, continue to inspire fierce debate and admiration in equal measure. It’s not hard to see why. The years haven’t cooled off the bracing inventiveness of Hume’s writing one bit – he is as frenetic, wide-ranging and profound as he ever was.

Empathy

The foundation of Hume’s ethical system is his emphasis on empathy, sometimes referred to as “fellow-feeling” in his writing. Hume believed that we are constantly being shaped and influenced by those around us, via both an imaginative, perspective-taking form of empathy – putting ourselves in other’s shoes – and a “mechanical” form of empathy, now called emotional contagion.

Ever walked into a room of laughing people and found yourself smiling, even though you don’t know what’s being laughed at? That’s emotional contagion, a means by which we unconsciously pick up on the emotional states of those around us.

Hume emphasised these forms of fellow-feeling as the means by which we navigate our surroundings and make ethical decisions. No individual is disconnected from the world – no one is able to move through life without the emotional states of their friends, lovers, family members and even strangers getting under their skin. So, when we act, it is rarely in a self-interested manner – we are too tied up with others to ever behave in a way that serves only ourselves.

The Nature of the Self

Hume is also known for his controversial views on the self. For Hume, there is no stable, internalised marker of identity – no unchanging “me”. When Hume tried to search inside himself for the steady and constant “David Hume” he had heard so much about, he found only sensations – the feeling of being too hot, of being hungry. The sense of self that others seemed so certain of seemed utterly artificial to him, a tool of mental processing that could just as easily be dispatched.

Hume was no fool – he knew that agents have “character traits” and often behave in dependable ways. We all have that funny friend who reliably cracks a joke, the morose friend who sees the worst in everything. But Hume didn’t think that these character traits were evidence of stable identities. He considered them more like trends, habits towards certain behaviours formed over the course of a lifetime.

Such a view had profound impacts on Hume’s ethics, and fell in line with his arguments concerning empathy. After all, if there is no self – if the line between you and I is much blurrier than either of us initially imagined – then what could be seen as selfish behaviours actually become selfless ones. Doing something for you also means doing something for me, and vice versa.

On Hume’s view, we are much less autonomous, sure, forever buffeted around by a world of agents whose emotional states we can’t help but catch, no sense of stable identity to fall back on. But we’re also closer to others; more tied up in a complex social web of relationships, changing every day.

Moral Motivation

Prior to Hume, the most common picture of moral motivation – one initially drawn by Plato – was of rationality as a carriage driver, whipping and controlling the horses of desire. According to this picture, we act after we decide what is logical, and our desires then fall into place – we think through our problems, rather than feeling through them.

Hume, by contrast, argued that the inverse was true. In his ethical system, it is desire that drives the carriage, and logic is its servant. We are only ever motivated by these irrational appetites, Hume tells us – we are victims of our wants, not of our mind at its most rational.

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

At the time, this was seen as a shocking inversion. But much of modern psychology bears Hume out. Consider the work of Sigmund Freud, who understood human behaviour as guided by a roiling and uncontrollable id. Or consider the situation where you know the “right” thing to do, but act in a way inconsistent with that rational belief – hating a successful friend and acting to sabotage them, even when on some level you understand that jealousy is ugly.

There are some who might find Hume’s ethics somewhat depressing. After all, it is not pleasant to imagine yourself as little more than a constantly changing series of emotions, many of which you catch from others – and often without even wanting to. But there is great beauty to be found in his ethical system too. Hume believed he lived in a world in which human beings are not isolated, but deeply bound up with each other, driven by their desires and acting in ways that profoundly affect even total strangers.

Given we are so often told our world is only growing more disconnected, belief in the possibility to shape those around you – and therefore the world – has a certain beauty all of its own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2021

Autonomy is the capacity to form beliefs and desires that are authentic and in our best interests, and then act on them.

What is it that makes a person autonomous? Intuitively, it feels like a person with a gun held to their head is likely to have less autonomy than a person enjoying a meandering walk, peacefully making a choice between the coastal track or the inland trail. But what exactly are the conditions which determine someone’s autonomy?

Is autonomy just a measure of how free a person is to make choices? How might a person’s upbringing influence their autonomy, and their subsequent capacity to act freely? Exploring the concept of autonomy can help us better understand the decisions people make, especially those we might disagree with.

The definition debate

Autonomy, broadly speaking, refers to a person’s capacity to adequately self-govern their beliefs and actions. All people are in some way influenced by powers outside of themselves, through laws, their upbringing, and other influences. Philosophers aim to distinguish the degree to which various conditions impact our understanding of someone’s autonomy.

There remain many competing theories of autonomy.

These debates are relevant to a whole host of important social concerns that hinge on someone’s independent decision-making capability. This often results in people using autonomy as a means of justifying or rebuking particular behaviours. For example, “Her boss made her do it, so I don’t blame her” and “She is capable of leaving her boyfriend, so it’s her decision to keep suffering the abuse” are both statements that indirectly assess the autonomy of the subject in question.

In the first case, an employee is deemed to lack the autonomy to do otherwise and is therefore taken to not be blameworthy. In the latter case, the opposite conclusion is reached. In both, an assessment of the subject’s relative autonomy determines how their actions are evaluated by an onlooker.

Autonomy often appears to be synonymous with freedom, but the two concepts come apart in important ways.

Autonomy and freedom

There are numerous accounts of both concepts, so in some cases there is overlap, but for the most part autonomy and freedom can be distinguished.

Freedom tends to broader and more overt. It usually speaks to constraints on our ability to act on our desires. This is sometimes also referred to as negative freedom. Autonomy speaks to the independence and authenticity of the desires themselves, which directly inform the acts that we choose to take. This is has lots in common with positive freedom.

For example, we can imagine a person who has the freedom to vote for any party in an election, but was raised and surrounded solely by passionate social conservatives. As a member of a liberal democracy, they have the freedom to vote differently from the rest of their family and friends, but they have never felt comfortable researching other political viewpoints, and greatly fear social rejection.

If autonomy is the capacity a person has to self-govern their beliefs and decisions, this voter’s capacity to self-govern would be considered limited or undermined (to some degree) by social, cultural and psychological factors.

Relational theories of autonomy focus on the ways we relate to others and how they can affect our self-conceptions and ability to deliberate and reason independently.

Relational theories of autonomy were originally proposed by feminist philosophers, aiming to provide a less individualistic way of thinking about autonomy. In the above case, the voter is taken to lack autonomy due to their limited exposure to differing perspectives and fear of ostracism. In other words, the way they relate to people around them has limited their capacity to reflect on their own beliefs, values and principles.

One relational approach to autonomy focuses on this capacity for internal reflection. This approach is part of what is known as the ‘procedural theory of relational autonomy’. If the woman in the abusive relationship is capable of critical reflection, she is thought to be autonomous regardless of her decision.

However, competing theories of autonomy argue that this capacity isn’t enough. These theories say that there are a range of external factors that can shape, warp and limit our decision-making abilities, and failing to take these into account is failing to fully grasp autonomy. These factors can include things like upbringing, indoctrination, lack of diverse experiences, poor mental health, addiction, etc., which all affect the independence of our desires in various ways.

Critics of this view might argue that a conception of autonomy is that is broad makes it difficult to determine whether a person is blameworthy or culpable for their actions, as no individual remains untouched by social and cultural influences. Given this, some philosophers reject the idea that we need to determine the particular conditions which render a person’s actions truly ‘their own’.

Maybe autonomy is best thought of as merely one important part of a larger picture. Establishing a more comprehensively equitable society could lessen the pressure on debates around what is required for autonomous action. Doing so might allow for a broadening of the debate, focusing instead on whether particular choices are compatible with the maintenance of desirable societies, rather than tirelessly examining whether or not the choices a person makes are wholly their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

WATCH

Relationships

Virtue ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five subversive philosophers throughout the ages

Philosophy helps us bring important questions, ideas and beliefs to the table and work towards understanding. It encourages us to engage in examination and to think critically about the world.

Here are five philosophers from various time periods and walks of life that demonstrate the importance and impact of critical thinking throughout history.

Ruha Benjamin

Ruha Benjamin (1978–present), while not a self-professed philosopher, uses her expertise in sociology to question and criticise the relationship between innovation and equity. Benjamin’s works focus on the intersection of race, justice and technology, highlighting the ways that discrimination is embedded in technology, meaning that technological progress often heightens racial inequalities instead of addressing them. One of the most prominent of these is her analysis of how “neutral” algorithms can replicate or worsen racial bias because they are shaped by their creators’ (often unconscious) biases.

“The default setting of innovation is inequity.”

J. J. C. Smart

J.J.C. Smart (1920-2012) was a British-Australian philosopher with far-reaching interests across numerous subfields of philosophy. Smart was a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities at its establishment in 1969. In 1990, he was awarded the Companion in the General Division of the Order of Australia. In ethics, Smart defended “extreme” act utilitarianism – a type of consequentialism – and outwardly opposed rule utilitarianism, dubbing it “superstitious rule workshop”, contributing to its steadily decline in popularity.

“That anything should exist at all does seem to me a matter for the deepest awe. But whether other people feel this sort of awe, and whether they or I ought to, is another question. I think we ought to.”

Elisabeth of the Bohemia

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618–1680) was a philosopher who is best known for her correspondence with René Descartes. After meeting him while he was visiting in Holland, the two exchanged letters for several years. In the letters, Elisabeth questions Descartes’ early account of mind-body dualism (the idea that the mind can exist outside of the body), wondering how something immaterial can have any effect on the body. Her discussion with Descartes has been cited as the first argument for physicalism. In later letters, her criticisms prompted him to develop his moral philosophy – specifically his account of virtue. Elisabeth has featured as a key subject in feminist history of philosophy, as she was at once a brilliant and critical thinker, while also having to live with the limitations imposed on women at the time.

“Inform your intellect, and follow the good it acquaints you with.”

Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE–399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy, though almost all we know of him is derived from the work of others, like Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes. Socrates is known for bringing about a huge shift in philosophy away from physics and toward practical ethics – thinking about how we do live and how we should live in the world. Socrates is also known for bringing these issues to the public. Ultimately, his public encouragement of questioning and challenging the status quo is what got him killed. Luckily, his insights were taken down, taught and developed for centuries to come.

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

Francesca Minerva

Francesca Minerva is a contemporary bioethicist whose work includes medical ethics, technological ethics, discrimination and academic freedom. One of Minerva’s most controversial (if misunderstood) contributions to ethics is her paper, co-written with Alberto Giubilini in 2012, titled “After-birth Abortion: why should the baby live?”. In it, the pair argue that if it’s permissible to abort a foetus for a reason, then it should also be permissible to “abort” (i.e., euthanise) a newborn for the same reason. Minerva is also a large proponent of academic freedom and co-founded the Journal of Controversial Ideas in an effort to eliminate the social pressures that threaten to impede academic progress.

“The proper task of an academic is to strive to be free and unbiased, and we must eliminate pressures that impede this.”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 11 NOV 2021

The scenario is familiar to us all. Company X is in crisis. A series of poor management decisions set in motion a sequence of events that lead to an avalanche of bad headlines and public outcry.

When things go wrong for an organisation – so wrong that the carelessness or misdeeds revealed could be considered ethical failure – responsibility is shouldered by those who are the final decision makers. They are and should be held accountable.

Boards of organisations, and the individual directors that comprise them, collectively make decisions about strategy, governance and corporate performance. Decisions that involve the interests of shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and the wider community. They will also involve competing values, compromises and tradeoffs, information gaps and grey areas.

In the recent 2021 Future of the Board report from The Governance Institute of Australia, respondents were surveyed to consider the most valued attributes for future board directors. Strategic and critical thinking were once again ranked the highest, closely followed by the values of ethics and culture as the two most important areas that boards need to focus on to prevent corporate failure. A culture of accountability, transparency, trust and respect were viewed as a top factor determining a healthy dynamic between boards and management.

Ethics plays a central role in the decisions that face Boards and directors, such as:

- What constitutes a conflict of interest and how should it be managed?

- How aggressive should tax strategies be?

- What incentive structures and sales techniques will create a healthy and ethical organisational culture?

- What about investments in organisations that profit from arms and weaponry?

- How should organisations manage the effects technology has on their workforce?

- What obligation do organisations have to protect the environment and human rights?

Together, The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) and The Ethics Centre have developed a decision-making guide for directors.

Ethics in the Boardroom provides directors with a simple decision-making framework which they can use to navigate the ethical dimensions of any decision. Through the insights of directors, academics and subject matter experts, the guide also provides four lenses to frame board conversations. These lenses give directors the best chance of viewing decisions from different perspectives. Rather than talking past each other, they will help directors pinpoint and resolve disagreement.

- Lens 1: General influences – Organisations are participants in society through the products and services they offer and their statuses as employers and influencers. The guide invites directors to seek out the broadest possible range of perspectives to enhance their choices and decisions. It also suggests that organisations should strive for leadership. What do you think about companies that take a stance on matters like climate change and same sex marriage?

- Lens 2: The board’s collective culture and character – In ethical decision making, directors are bound to apply the values and principles of their organisation. As custodians, they must ensure that culture and values are aligned. The guide invites directors to be aware that ethical decision-making in the boardroom must be tempered. Decision making shouldn’t be driven by: form over substance, passion over reason, collegiality over concurrence, the need to be right, or legacy. Just because a particular course of action is legal, does that make it right? Just because a company has always done it that way, should they continue?

- Lens 3: Interpersonal relationships and reasoning – Boards are collections of individuals who bring their own individual decision-making ‘style’ to the board table. Power dynamics exist in any group, with each person influencing and being influenced by others. Making room for diversity and constructive disagreement is vital. How can chairs and other directors empower every director to stand up for what is right? How do boards ensure that the person sitting quietly, with deep insights into ethical risk, has the courage to speak?

- Lens 4: The individual director – Directors bring their own wisdom and values to decision making. But they also might bring their own motivations that biases. The guide invites directors to self-reflect and bring the best of themselves to the board table. How can we all be more reflective in our own decision making?

This guide is a must-read for anyone who has an interest in the conduct of any board-led organisation. That includes schools, sports clubs, charities and family businesses as well as large corporations.

Behind each brand and each company, there are people making decisions that affect you as a consumer, employee and citizen. Wouldn’t you rather that those at the top had ethics at the front of their mind in the decisions that they make?

Click here to view or download a copy of the guide.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Market logic can’t survive a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Dame Julia Cleverdon on social responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership