Exercising your moral muscle

Exercising your moral muscle

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 8 SEP 2021

Day-to-day decisions carry more weight in the context of the pandemic.

Previously simple choices like whether or not to go to the shops are now shadowed by dire consequences, and the act of constantly weighing up those consequences can lead to ‘moral fatigue’.

“This is the kind of wearing down of a person who is constantly making ethical decisions in conditions of fundamental ambiguity,” Ethics Centre executive director Dr Simon Longstaff recently told the ABC.

“It’s the sense of the weight of your decision that can be the source of the fatigue.”

Much like physical exercise, Dr Longstaff says there are ways to exercise our moral muscle so that it becomes stronger. Our choices matter because of the cumulative effect they have, and if exercised every day, building up moral fitness can also help prevent moral injury and its effect on our mental health.

Here are four ways to exercise your moral muscle and help with decision-making:

- Build a support system of friends and family members around you who are open to the conversation. Nobody can be expected to know exactly what to do in any given situation, but having a support system of peers, friends and family to bounce ideas off and get perspective can be invaluable.

- Is there urgency to the problem? If not, setting it aside for a period of time and going for a walk can help with clarity. “Allowing a bit of time and literally going for a walk is one of the really good things you can do,” Dr Longstaff says. “It’s amazing how much just walking helps things just sort out in your own mind.”

- All muscles need time to recover, so factor in rest days to help manage mental exhaustion and take time to do something you enjoy. “Think creatively about ‘what makes me happy in life? What are the things that I really love doing, that I find relaxing?’,” researcher and psychologist Professor Jolanda Jetten told the ABC. “We know that feeling in control is a very good predictor of good health, physical and mental. People should think of ways they can encounter situations and contexts where they feel fully in control, where they don’t have to worry.”

- If all else fails, or you’re not sure who to talk to, make a booking with the Ethics Centre’s hotline Ethi-call and speak with a qualified counsellor to help shape your perspective and find a pathway that’s right for you.” A service like Ethi-call helps you become really clear about the facts of the matter,” Dr Longstaff says. “Most importantly, what it does is give you the ability to shape your perspective so you can see the problem from different angles, and in that you might open up an option that never occurred to you that resolves the situation.”

Free, independent helpline Ethi-call provides guidance and support to anyone facing a difficult ethical dilemma or decision. Book a call with a qualified counsellor here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics from the couch: 5 shows to binge on

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

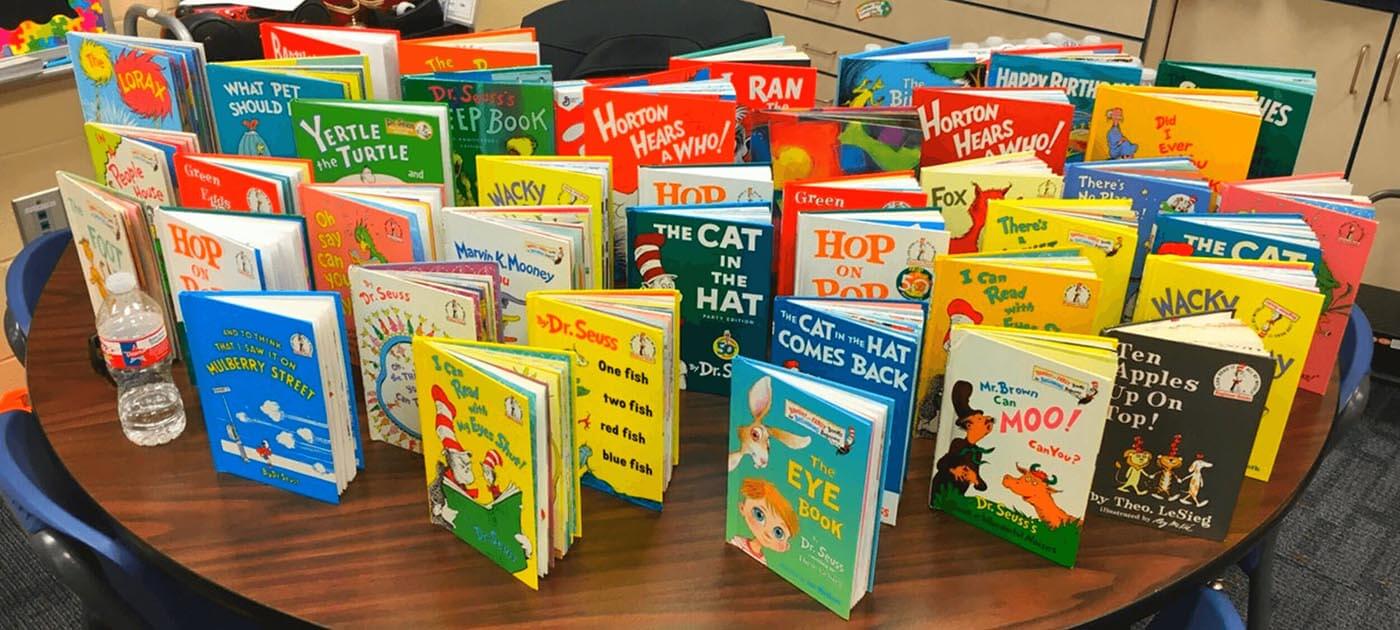

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Violent porn and feminism

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan The Ethics Centre 1 SEP 2021

Does pornography, especially violent pornography, contribute to gender-based violence, and if so, is censorship the answer? Or can the pornographic industry coexist with the drive towards gender equality?

We occupy a world plagued by sexual and gender-based violence. The United Nations declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) asserts that such violence need be recognised as “a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women”.

Globally in 2017, 219 women were killed each day by either a member of their own family or by their own intimate partner. Debates about the complex causes of such violence and reasons for the persistence of gender inequality remain. The role that pornography may play in both the maintenance and propagation of these harms is one of many factors considered relevant to the debate. Specifically, ethicists are needed to address the question: Could pornography and feminism be compatible bedfellows after all?

Renowned feminist philosopher Catherine Mackinnon argues that pornography “works as primitive conditioning”, meaning that its content is likely to inform the desires and subsequent actions of its viewers. Mackinnon asserts that if pornographic images are violent, this is likely to result in unwanted sexual violence being inflicted onto others by pornography’s consumers.

Contemporarily, debate and disagreement persist regarding how pornography should be managed for adult audiences.

Various philosophers and feminist theorists, such as Mackinnon, argue in favour of some form of criminal action being taken against certain types of pornography due to its capacity to harm women. In 1983, Mackinnon, alongside feminist writer and activist Andrea Dworkin, brought forward an Antipornography Civil Ordinance which proposed that pornography needs to be treated as a violation of women’s civil rights. The pair aimed to remove the freedom of speech protections pornography had been granted under United States law. The ordinance was ultimately struck down by the courts.

Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

To this day, feminists remain largely divided over MacKinnon’s antipornography ordinance. Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

Calls to dismantle the industry of pornography are often taken to be synonymous with feminist action. In such cases, this action is thought to be the best means of protecting women from an industry rife with exploitation. Similarly, calls to cease pornographic productions are often thought to serve the function of preserving women’s dignity by allowing them to avoid careers centred around sexual objectification.

However, demands for censorship or a general production shutdown of pornographic films are also calls to severely limit the career opportunities and subsequently the financial resources of pornographic actresses. Doing so may risk further degrading these workers’ rights. The profitability and questionable legality of the porn industry often permits it to function below industry standard, resulting in inadequate worker protections being extended to porn actors and actresses.

Stoya is a female adult entertainer who has spoken openly about a form of feminism which she worries hates both sex work and pornography. She is concerned that female sexuality is only being embraced within narrow margins, neglecting the possibility that hardcore pornography may empower women, both actresses and viewers, rather than degrade them. Stoya argues that a contemporary feminism which celebrates women’s right to work and earn an independent wage is flawed if it simultaneously rebukes women who freely choose to perform in pornography to acquire that wage. For Stoya, performing in hardcore pornography (produced under fair working conditions) does nothing to degrade the status of female performers. Rather, it stands as a celebration of a tirelessly campaigned for and emancipated female sexuality.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared. Doing so puts these women at increased risk of assault and exploitation out of fear their allegations will not be trusted or that they will meet with legal consequences. Stoya herself brought forward rape charges against famous male pornstar James Deen, and she holds that the remedy to such injustices lies in improving workers’ rights and the legislative systems surrounding the industry of pornography, rather than in trying to shut down the industry altogether.

This lack of regulation constitutes an injustice far greater than the supposed, yet largely unarticulated, harm of women being free to use their naked bodies for profit. The mere existence of agential and passionate hardcore pornographic actresses importantly signals the beginnings of a world where women’s bodies are no longer policed in ways which unjustifiably align sex with shame and exploitation.

So long as the porn industry is made to function on par with other industry’s standards, there is no reason to consider the bodies of female pornographic actresses anymore degraded, or exploited, than non-pornographic actresses, tradespeople, or frontline healthcare workers.

Calls to censor or morally condemn pornography are often less concerned with the rights of pornographic actresses and more with the potentially negative impact pornography has on its consumers. There are concerns, for example, that viewing violent pornography may increase sexual assault rates, a causal link which is yet to be definitively established. However, even if particular depictions of women’s bodies were found to increase the likelihood that men assault women, it is not immediately apparent that the desirable solution would be to forbid those depictions.

This censorship style solution shares particular characteristics with victim blaming culture, in which victims are blamed for the actions of perpetrators. In both victim blaming and pro-censorship anti-porn positions, the onus of change is placed on those who are determined to be the cause of any given injustice. The pornographic actress, for example, is told she cannot continue to do her work, instead of alternative interventions being sought which target perpetrators who may have been inspired by viewing particular pornographic depictions. We do not think it suitable to tell women to wear more clothing to stop men raping them; why should matters of pornography be handled any differently?

There are more desirable, alternative solutions to address contemporary issues of misogyny. First is the formation and endorsement of a safe and responsible pornography industry where the agency and security of actors and actresses is guaranteed. Unfortunately there will always be room for exploitation and abuse, however, these risks can be mitigated by extending workers’ rights and fair working conditions to pornographic actors in the same way such rights are endowed to workers in other industries.

Content subscription service Onlyfans stands as a site moving the pornography industry in this direction by allowing performers greater control over their content and income. OnlyFans allows performers to safely and independently produce pornographic content. However, the platform hasn’t avoided trouble for hosting adult content: Onlyfans recently announced it would be banning explicit content in a bid to attract investors, only to reverse its decision within a week after outcry from users.

Ongoing periphery interventions are also required to address gender-based violence and gender inequality more generally, such as improved sex education curriculums which provide more comprehensive education on consent and respectful relationships to school age children.

Interventions such as bolstering the regulatory bodies surrounding pornography and improving sex-ed curriculums allows societies to place adequate accountability on those who commit or are at risk of committing acts of violence against women. These interventions should be favoured over those which risk undermining the agency of both female performers and consumers of pornography.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality. Theorists and feminists alike need to engage in critical discourse regarding where the onus of change need be placed. The porn industry, pornographic actresses and perpetrators of violence against women are all potential targets of this change. The decisions we make regarding what actions should be taken will determine whether or not pornography is compatible with contemporary feminism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 AUG 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we believe ethics is a collaboration – a conversation between diverse people trying to figure out how to act, live and make good decisions.

This means we need a range of people participating in the conversation, of all ages. Thanks to our donor, Chris Cuffe AO at Third Link Investment Managers, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Daniel Finlay to Youth Engagement. Daniel is a graduate from the University of Sydney with a Bachelor of Arts and Science (Hons) and a Postgraduate Certificate in Publishing. He also received Class I Honours for his thesis in ethical philosophy. To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

Tell us, what attracted you to philosophy?

My first philosophy-related class was called Bioethics and I actually took it because I had come back from a break and couldn’t continue my psychology units until the next semester. But from the moment I left the first tutorial, I knew this was where I would end up going. The unit was practical ethics with a focus on humans and their bodies. The topics we covered ranged from black-market organ selling to sex work to people suffering from body integrity identity disorder (BIID). The BIID discussion particularly made me realise how many questions we have to face that simply don’t have neat or obvious answers. BIID is a very rare disorder where a healthy person very strongly desires to amputate one or more of their limbs. And here we were, a group of fresh-faced 19-year-olds, trying to figure out what the hell to do with that information.

That sounds like an interesting place to start. Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions. How are you dealing with it and what do you hope we’ll be able to bring out the other side?

Honestly, I’m part of the lucky few who haven’t been too flipped around by the lockdowns. I do very much miss rock climbing and have admittedly fallen back into lazy habits without it, but on the whole I can deal with being at home very easily because that’s where I like to spend most of my time regardless.

I’m hoping that we all come out of this with a bit more patience. COVID has obviously slowed a lot of things down for a lot of people. Media content is coming out slower, packages are constantly delayed, work projects put on the back-burner. Hopefully most people come out the other side of this with the realisation that most things aren’t as urgent as they sometimes seem, and a little patience when dealing with fellow humans can go a long way.

With all that time at home, you must have developed some guilty pleasures during the pandemic. Can you share one with us?

I wish I had something quirky or funny to share but the sad reality is my guiltiest pleasure is just watching TikToks at midnight in bed instead of getting a reasonable night’s sleep.

Pretty sure that you aren’t alone there. So, what does a standard day in your life look like?

Mostly playing games, watching Netflix/YouTube and managing an online Discord community I run. At the moment, I’m researching how, when and why young people engage with ethics in their lives and offering a younger perspective on a range of projects. Whenever I find the energy, I do try to make time for reading (I’ve recently gotten back into some fantasy novels), walking, listening to podcasts, rock climbing, writing and annoying my cat, Panda.

Let’s wrap up close to home. What does ethics mean to you and why are you interested in bringing it to the attention of young people?

To me, ethics is about learning to live with ourselves in a way that is sustainable. Part of that process is learning how to question ourselves, other people, systems and structures. It’s about identifying assumptions and patterns in our beliefs and behaviours and learning to discard or modify the unfounded ones.

I’m interested in bringing it to a younger audience because I think studying ethics and critical thinking is such an important part of developing the cognitive resources needed to make significant change in the world in a responsible and empathetic way. I’ve already seen firsthand, from being a Primary Ethics teacher, the immense good that this can do, so if I can help bring these resources into the brains of passionate teenagers then I think the world will be much better off.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Big thinkerScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 18 AUG 2021

We’re all familiar with the Einsteins and Hawkings of history, but there are many who have influenced the direction and development of science. Here are seven scientists and philosophers who have shaped how science is practiced today.

Tim Berners-Lee

Sir Timothy Berners-Lee (1955-present) is an English computer scientist. Most notably, he is the inventor of the World Wide Web and the first web browser. If not for his innovative insight and altruistic intent (he gave away the idea for free!), the way you’re viewing this very page may have been completely different. These days, Berners-Lee is fighting to save his vision. The Web has transformed, he says, and is being abused in ways he always feared – from political interference to social control. The only way forward is pushing for ethical design and pushing back against web monopolisation.

Legacy: The World Wide Web as we know it.

Jane Goodall

Dame Jane Goodall (1934-present) is an English primatologist and anthropologist. Over 60 years ago, Goodall entered the forest of Gombe Stream National Park and made the ground-breaking discovery that chimpanzees make and use tools and exhibit other human-like behaviour, including armed conflict. Since then, she has spent decades continuing her extensive and hands-on research with chimpanzees, written a plethora of books, founded the Jane Goodall Institute to scale up conservation efforts, and is forever changing the way humans relate to animals.

Legacy: “Only if we understand, will we care. Only if we care, will we help. Only if we help, shall all be saved.”

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. He is best known as one of the greatest philosophers of science in the twentieth century, having contributed a new and novel way of thinking about the methodology of science. Against the prevailing empiricist idea that rationally acceptable beliefs can only be justified through direct experience, Popper proposed the opposite. In fact, Popper argued, theories can never be proven to be true. The best we can do as humans is ensure that they are able to be false and continue testing them for exceptions, even as we use these assumptions to further our knowledge. One of Popper’s most enduring thoughts is that we should rationally prefer the simplest theory that explains the relevant facts.

Legacy: The idea that to be scientific is to be fallible.

Marie Curie

Marie Curie (1867-1934) was a Polish-French physicist and chemist. She was a pioneer of radioactivity research, coining the term with her husband, and discovered and named the new elements “polonium” and “radium”. During the course of her extensive career, she was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize, and the first to be awarded two Nobel Prizes in two scientific fields: physics and chemistry. Due to the underfunded research conditions of time and ignorance about the danger of radiation exposure, it’s thought that a large factor in her death was radiation sickness.

Legacy: Discovering polonium and radium, pioneering research into the use of radiation in medicine and fundamentally changing our understanding of radioactivity.

René Descartes

René Descartes (1596-1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician and scientist. Descartes is most widely known for his philosophy – including the famous “I think, therefore I am” – but he was also an influential mathematician and scientist. Descartes’ possibly most enduring legacy is something high school students are very familiar with today – coordinate geometry. Also known as analytic or Cartesian geometry, this is the use of algebra and a coordinates graph with x and y axes to find unknown measurements. Descartes was also interested in physics, and it is thought that he had great influence on the direction that a young Isaac Newton took with his research – Newton’s laws of motion were eventually modelled after Descartes’ three laws of motion, outlined in Principles of Philosophy. In his essay on optics, he independently discovered the law of reflection – the mathematical explanation of the angle at which light waves are reflected.

Legacy: “The seeker after truth must, once in the course of his life, doubt everything, as far as is possible.”

Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) was an English chemist and X-ray crystallographer who is most famous for her posthumous recognition. During her life, including in her PhD thesis, she researched the properties and utility of coal, and the structure of various viruses. She is now often referred to as “the forgotten heroine” for the lack of recognition she received for her contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA. Even one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the DNA double helix suggested that Franklin should have been among the recipients, but posthumous nominations were very rare. Unfortunately, this was not her only posthumous brush with a Nobel Prize, either. One day before she and her team member were to unveil the structure of a new virus affecting tobacco farms, Franklin died of ovarian cancer. Over two decades later, her team member went on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the continued research on the virus. Since her death, she has been recognised with over 50 varying awards and honours.

Legacy: Foundational research that informed the discovery of the structure of DNA, coal and graphite.

Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky (1928-present) is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist and social/political critic. While Chomsky may be better known as a political dissident and social critic, he also played a foundational role in the development of modern linguistics and founded a new field: cognitive science, the scientific study of the mind. Chomsky’s research and criticism of behaviourism saw the decline in behaviourist psychology, and his interdisciplinary work in linguistics and cognitive science has gone on to influence advancements in a variety of fields including computer science, immunology and music theory.

Legacy: Establishing cognitive science as a formal scientific field and inciting the fall of behaviourism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

A framework for ethical AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2021

When big decisions loom, it’s often easy to get stuck ruminating all the possible ways to proceed, how it might go wrong, or get confused by taking on too much external advice and input.

Of all the ways you might act, which is the best? Which of all the possibilities should you choose?

Putting ethics at the centre of your thinking can help. It offers a framework for evaluating life’s difficult decisions, which invariably involve questions about what’s good and what’s right.

These five steps can help you move toward a solution that is in alignment with your purpose, values and principles.

1. Check in with your body

Take a moment to drop into your body. Often, we rush headlong into considering without pausing to reflect on how we feel. Our emotions play a major role in our decisions – both consciously and unconsciously. Stop for a moment and pay attention to your feelings; what are they telling you about what matters most?

You may not unlock immediate clarity, and that’s ok. Just begin by recognising and labelling the emotions that arise. Often these feelings are a compass pointing you to what matters most to you.

2. Question your assumptions and identify the facts.

Often when we feel uncertain, it’s because we are lacking information that is required to make a considered decision. What do you know about the choice in front of you? Write down all the facts that you know about your options.

Now test your thinking. Is there anything you are assuming to be true that may not be? Bracket fears or other people’s opinions for a moment and just focus on what you know to b be true. Be aware of jumping to any conclusions around the circumstance, people involved or potential outcomes.

By looking at the situation more objectively, you can identify what you actually know, and what you need to know. Now ask yourself: do you have all the facts and information that you need to make an informed decision? If there are gaps, write a list of the questions you need answers to, and seek the information that you need to have more factual data to consider.

3. Consider how the options relate to your values.

It’s time to get clear on what matters most to you. That is the key to unlocking your values. Our values are like signposts, they indicate what’s most important to us. It can help to consider the situation through the lens of what you consider most ethically relevant, starting with values that matter most to you such as honesty, transparency, kindness, or integrity. Your values also reflect what you stand for, desire or seek to protect, such as financial security, freedom, creativity, family or community for example.

4. What are the lines you won’t cross?

Next, bring into consideration your principles. If values are the signposts, then principles are the guide rails that keep us on track. They apply to the pursuit of many different types of goals and help when values conflict with one another. Principles can’t be selectively applied. Once adopted, they apply to every decision.

You may value success but not lying or cheating is a solid principle to guide how you achieve success.

You might have just a handful of principles that you personally live by. Check in to make sure that the decision you make doesn’t cause you to cross any of those guide rails.

5. Decide on what matters, and why.

Unpack all of the reasons you might decide in each way and with all of the information on the table – rule out any option that moves you away from your purpose, values and principles, and ultimately, seek out the decision that best aligns with them.

Decision-making is complex at the best of times. But sometimes life can present us with a choice where there is no right option – or where both pathways are wrong. When those moments strike it can feel impossible to find a pathway forward.

You don’t have to navigate it alone. Ethi-call is a free helpline designed to provide structured support and guidance through those very difficult decisions.

Appointments are with trained ethics counsellors who take you through a series of questions that will help clarify the situation and shine a light on what is most important to you.

Make a booking at www.ethi-call.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

ExplainerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JUL 2021

Imagine waking up in a bed, disoriented, bleary-eyed and confused.

You can’t remember how you got to there, and the bed you’re in doesn’t feel familiar. As you start to get a sense of your surroundings, you notice a bunch of medical equipment around. You notice plugs and tubes coming out of your body and realise you’re back-to-back with another person.

A glimpse in the mirror tells you the person you’re attached to is a world-famous violinist – one with a fatal kidney ailment. And now, you start to realise what’s happened. Last night, you were invited to be the guest of honour at an event hosted by the Society of Music Lovers. During the event, they told you about this violinist – whose prodigious talent would be taken from the world too soon if they couldn’t find a way to fix him.

It looks like, based on the medical records strewn around the room, the Society of Music Lovers have been scouring the globe for someone whose blood type and genetic markers are a match with the violinist.

A doctor enters the room, looking distressed. She informs you that the Society of Music Lovers drugged and kidnapped you, and had your circulatory system hooked you up to the violinist. That way, your healthy kidney can extract the poisons from the blood and the violinist will be cured – and you’ll be completely healthy at the end of the process. Unfortunately, the procedure is going to take approximately 40 weeks to complete.

“Look, we’re sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you–we would never have permitted it if we had known,” the doctor apologises to you. “But still, they did it, and the violinist is now plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it’s only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment and can safely be unplugged from you.”

After all, the doctor explains, “all persons have a right to life, and violinists are persons. Granted you have a right to decide what happens in and to your body, but a person’s right to life outweighs your right to decide what happens in and to your body. So you cannot be unplugged from him.”

This thought experiment originates in American philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson’s famous paper ‘In Defence of Abortion’ and, in case you hadn’t figured it out, aims to recreate some of the conditions of pregnancy in a different scenario. The goal is to test how some of the moral claims around abortion apply to a morally similar, contextually different situation.

Thomson’s question is simple: “Is it morally incumbent on you to accede to this situation?” Do you have to stay plugged in? “No doubt it would be very nice of you if you did, a great kindness. But do you have to accede to it?” Thomson asks.

Thomson believes most people would be outraged at the suggestion that someone could be subjected to nine months of medical interconnectedness as a result of being drugged and kidnapped. Yet, Thomson explains, this is more-or-less what people who object to abortion – even in cases where the pregnancy occurred as a result of rape – are claiming.

Part of what makes the thought experiment so compelling is that we can tweak the variables to mirror more closely a bunch of different situations – for instance, one where the person’s life is at risk by being attached to the violinist. Another where they are made to feel very unwell, or are bed-ridden for nine months… the list goes on.

But Thomson’s main goal isn’t to tweak an admittedly absurd scenario in a million different ways to decide on a case-by-case basis whether an abortion is OK or not. Instead, her thought experiment is intended to show the implausibility of the doctor’s final argument: that because the violinist has a right to life, you are therefore obligated to be bound to him for nine months.

“This argument treats the right to life as if it were unproblematic. It is not, and this seems to me to be precisely the source of the mistake,” she writes.

Instead, Thomson argues that the right to life is, actually, a right ‘not to be killed unjustly’.

Otherwise, as the thought experiment shows us, the right to life leads to a situation where we can make unjust claims on other people.

For example, if someone needs a kidney transplant and they have the absolute right to life – which Thomson understands as “a right to be given at least the bare minimum one needs for continued life” – then someone who refused to donate their kidney would be doing something wrong.

Thinking about a “right to life” leads us to weird conclusions, like that if my kidneys got sick, I might have some entitlement to someone else’s organs, which intuitively seems weird and wrong, though if I ever need a kidney, I reserve the right to change my mind.

Interestingly, Thomson’s argument – written in 1971 – does leave open the possibility of some ethical judgements around abortion. She tweaks her thought experiment so that instead of being connected to the violinist for nine months, you need only be connected for an hour. In this case, given the relatively minor inconvenience, wouldn’t it be wrong to let the violinist die?

Thomson thinks it would, but not because the violinist has a right to use your circulatory system. It would be wrong for reasons more familiar to virtue ethics – that it was selfish, callous, cruel etc…

Part of the power of Thomson’s thought experiment is to enable a sincere, careful discussion over a complex, loaded issue in a relatively safe environment. It gives us a sense of psychological distance from the real issue. Of course, this is only valuable if Thomson has created a meaningful analogy between the famous violinist and what an actual unwanted pregnancy is like. Lots of abortion critics and defenders alike would want to reject aspects of Thomson’s argument.

Nevertheless, Thomson’s paper continues to be taught not only as an important contribution to the ethical debate around abortion, but as an excellent example of how to build a careful, convincing argument.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On policing protest

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 29 JUN 2021

Decisions are a part of being human. But that doesn’t mean they are easy.

Whether big or small, when a choice creates an ethical conflict, or where no option feels right, the path forward can seem out of sight.

These three philosophical concepts are designed to help deliver clarity in complexity. Next time you find yourself facing a dilemma, try running it through each of these to shed new light on the scenario.

The Golden Mean

When you’re trying to work out what the virtuous thing to do in a particular situation is, look to what lies in the middle between two extreme forms of behaviour (the middle being the mean). The mean will be the virtue, and the extremes at either end, vices. One end will usually be an excess, the other end a deficiency.

For example, in a situation that requires courage, there may be one extreme where you might act recklessly, and the other, do nothing out of cowardice. The virtuous response is the mean between these two.

The Sunlight Test

This test a simple way to test an ethical decision before you act on it. Ask yourself: ‘Would I do the same thing if I knew my actions would end up on the front page of the newspaper tomorrow?’

By imagining if your decision – and the reasons you made it – were public knowledge, we must consider our willingness to stand by that choice in a public forum.

Would you be proud of the action if people you most admire knew what you’d done and why? Would you be able to defend your choice? Would other people agree, or at least understand, why you did what you did?

This simple thought exercise helps give clarity on your motivations – so you can see clearer whether the choice is motivated by what is good or right, or by self-interest, reward, external pressures or opinions.

Plato’s Cave

One well known thought experiment is Plato’s allegory of the cave. It goes like this. Prisoners are chained up facing a wall deep within a cave. A fire behind them casts just enough light for them to see images upon the wall, which have been cast by puppeteers. Knowing no alternative, the prisoners believe what they see and hear to be the whole reality.

As the Philosopher John Locke said, “No man’s knowledge here can go beyond his experience”. When faced with a decision, consider the day-to-day experiences, lessons, conversations and modelled behaviour that is shaping what you believe to be ‘reality’.

Are shadow puppets (bias) driving your actions? Can you step outside your own projections on the wall to consider new perspectives and ideas? Can you separate truth from fiction? By challenging the things you believe to be true in any scenario you can make sure that your assumptions hold up to scrutiny.

Still stumped: Ask yourself these three questions:

What are your duties and responsibilities in this situation and to whom?

What counts as a good outcome and how will you know?

What would the wisest person you know say to do in this situation?

Ethi-call is a free helpline designed to provide structured guidance through life’s most challenging dilemmas. If you, or a loved one are facing a decision that leaves you with a bad feeling and no right way out, a conversation can help.

Appointments are with trained ethics counsellors who take you through a framework of prompts and questions that will help clarify the situation and shine a light on what is most important to you.

Make a booking at www.ethi-call.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Get mad and get calm: the paradox of happiness

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

Love has historically played a big role in how we understand the task of treating other people well. Many moral systems hold that love is foundational to doing right.

The Bible, for example, commands us to “love thy neighbour” – not merely to respect or value them, but to love them. Thousands of years later, philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch wrote that “loving attention” is the core of morality.

In our contemporary understanding of the word, love seems to involve partiality. In all kinds of settings from romantic love to the love in friendship or familial love, loving people seems to mean not loving others. We love our wife, not our neighbours’ wife. We love our friends and our parents, not our boss’ friends or our bus drivers’ father.

In fact, we might think that someone does not love their spouse in any meaningful sense of the word if they also say they love all other people equally – the celebrated essence of love seems to involve choosing some people over others.

This partiality affects our actions as well as our emotions: our parents, friends, and spouses receive more prioritisation, gifts, and emotional attention from us than strangers. This is a celebrated and joyful feature of human life.

Could love in fact be immoral – or amoral? Could behaving lovingly and behaving ethically be two separate tasks – tasks that might sometimes come into conflict?

Morality, has often been thought of as essentially neutral. That is, the moral gaze looks at everyone as equals; not favouring one person over another simply because of our relationship with them. Kantian ethicists, for instance, hold that all people deserve ethical treatment simply because they are persons.

Anyone who is a person deserves to have others not lie to them, disrespect them, enslave their body or seize their property. Thus, the only thing the moral gaze is concerned with is whether someone is a person – and since all people are persons, the moral gaze looks upon all of us equally.

Consequentialist ethics contains a similar commitment to neutrality. For a consequentialist, the moral measure of an action is whether it maximises value. Whose value is maximised has no special claim to our attention; the more value, the better, whether it accrues to my mother or to yours. Since the moral gaze looks to creating the most happiness, it looks at all people equally – as equal vectors of possible happiness.

If morality contains a commitment to neutrality – and if love contains a commitment to partiality – then the moral gaze and the loving gaze might conflict. It might even be the case that love demands acting in ways that morality seems to forbid.

Imagine that you are on a ship which begins to sink. You have held onto the railing but other passengers have not been so lucky, and in the water before you are several strangers struggling to stay afloat. Also in the water, struggling alongside the strangers, is your wife. Are you permitted to throw your wife the one remaining life jacket? Or is her right to life no stronger than any of the strangers’? Love seems to demand that we save our wife, but morality, if it is neutral, seems to offer no automatic reason why we should.

The philosopher Bernard Williams saw a way out of this puzzle. He argued that any person standing on the boat in this situation, who starts thinking about what morality demands, might reasonably be charged with having “one thought too many”. The person should not think “my wife is in the water – what does morality require I do?”. They should simply think “my wife is in the water,” and throw the life jacket.

Williams’ view was that a morally good person is not always thinking about what is morally justifiable. Perhaps, counterintuitively, being a truly ethical person means not always looking through the moral gaze. The question still remains – do love and morality ask us for different things?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

When we ask ‘what is it ethical for me to do here?’, ethicists usually start by zooming out.

We look for an overarching framework or set of principles that will produce an answer for our particular problem. For instance, if our ethical dilemma is about eating meat, or telling a white lie, we first think about an overarching claim – “eating meat is bad”, or “telling lies is not permissible”.

Then, we think through what could make that overarching claim true: what exactly is badness? The hope is that we will be able to come up with an independently-justified, holistic view that can spit out a verdict about any particular situation. Thus, our ethical reasoning usually descends from the universal to the particular: badness comes from causing harm, eating meat causes harm, therefore eating meat is bad, therefore I should not eat this meat in front of me.

This methodology has led to the development of many grand unifying ethical systems; frameworks that offer answers to the zoomed-out question “what is it right to do everywhere?”. Some emphasise maximising value; others doing your duty, perfecting your virtue, or acting with love and care. Despite their different answers, all these approaches start from the same question: what is the correct system of ethics?

One striking feature of this mode of ethical enquiry is how little it has agreed on over 4,000 years. Great thinkers have been wondering about ethics for at least as long as they have wondered about mathematics or physics, but unlike mathematicians or natural scientists, ethicists do not count many more principles as ‘solid fact’ now than their counterparts did in Ancient Greece.

Particularists say this shows where ethics has been going wrong. The hunt for the correct system of ethics was doomed before it set out: by the time we ask “what’s the right thing to do everywhere?”, we have already made a mistake.

According to a particularist, the reason we cannot settle which moral system is best is that these grand unifying moral principles simply do not exist.

There is no such thing as a rule or a set of principles that will get the right answer in all situations. What would such an ethical system be – what would it look like; what is its function? So that when choosing between this theory or that theory we could ask ‘how well does it match what we expect of an ethical system?’.

According to the particularist, there is no satisfactory answer. There is therefore no reason to believe that these big, general ethical systems and principles exist. There can only be ethical verdicts that apply to particular situations and sets of contexts: they cannot be unified into a grand system of rules. We should therefore stop expecting our ethical verdicts to have a universal-feeling structure, like “don’t lie, because lying creates more harm than good”.

What should we expect our ethical verdicts to feel like instead? What does particularism say about the moment when we ask ourselves “what should I do?”. The particularist’s answer is mainly methodological.

First, we should start by refining the question so that it becomes more particular to our situation. Instead of asking “should I eat meat?” we ask “should I eat this meat?”. The second thing we should do is look for more information – not by zooming out, but by looking around. That is, we should take in more about our exact situation. What is the history of this moment? Who, specifically, is involved? Is this moment part of a trend, or an isolated incident?

All these factors are relevant, and they are relevant on their own: not because they exemplify some grand principle. “Occasion by occasion, one knows what to do, if one does, not by applying universal principles, but by being a certain kind of person: one who sees situations in a certain distinctive way”, wrote John McDowell.

Particularism, therefore, leaves a great deal up to us. It conceives of being ethical as the task of honing an individual capacity to judge particular situations for their particulars. It does not give us a manual – the only thing it tells us for certain is that we will fail if we try to use one.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

ExplainerClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2021

Imagine for a second that the entire human race has gone extinct, with the exception of one man.

There is no hope for humankind to continue. We know, as a matter of certainty, that when this person dies, so too does the human race.

Got it? Good. Now, imagine that this last person spends their remaining time on Earth as an arbiter of extinction. Being themselves functionally extinct, they make it their purpose to eliminate, painlessly and efficiently, as much life on Earth as possible. Every living thing: animal, plant, microbe is meticulously and painlessly put down when this person finds it.

Intuitively, it seems like this man is doing something wrong. But according to New Zealand philosopher Richard Sylvan (though his argument was published under the name Richard Routley before he took his wife’s name when he married in 1983), traditional ethical theories struggle to articulate exactly why what they’re doing is wrong.

Sylvan, developing this argument in the 1960’s, argues that traditional Western ethics – which at the time consisted largely of variations of utilitarianism and deontology – rested on a single “super-ethic”, which states that people should be able to do what they wish, so long as they don’t harm anyone – or harm themselves irreparably.

A result of this super-ethic is that the dominant Western ethical traditions are “simply inconsistent with an environmental ethic; for according to it nature is the dominion of man and he is free to deal with it as he pleases,” according to Sylvan. And he has a point: traditional formulations of Western ethics have tended to exclude non-human animals (and even some humans) from the sphere of ethical concern.

Traditional formulations of Western ethics have tended to exclude non-human animals (and even some humans) from the sphere of ethical concern.

In fairness, utilitarianism has a better history with considering non-human animals. The founder of the theory, Jeremy Bentham, insisted that since animals can suffer, they deserve moral concern. But even that can’t criticise the actions of our last person, who delivers painless death, free of suffering.

Plus, most versions of utilitarianism focus on the instrumental value of things (basically, their usefulness). Rarely do we consider the fact that when we ask “is it useful?” we’re making an assumption about the user – that they’re human.

Immanuel Kant’s deontology begins with the belief that it is human reason that gives rise to our dignity and autonomy. This means any ethical responsibilities and claims only exist for those who have the right kind of ability: to reason.

Now, some Kantian scholars will argue that we still shouldn’t treat animals or the environment badly because it would make us worse people, ethically speaking. But that’s different to saying that the environment deserves our ethical consideration in its own right. It’s like saying bullying is wrong because it makes you a bad person, instead of saying bullying is wrong because it causes another person to suffer. It’s not all about you!

Sylvan describes this view as “human chauvinism”. Today, it’s usually called “anthropocentrism”, and it’s at the heart of Sylvan’s critique. What kind of a theory can condone the kind of pointless destruction that the Last Man thought experiment describes?

Since Sylvan published, a lot has changed – especially with regard to the animal rights movement. Indeed, Australian philosopher Peter Singer developed his own version of consequentialism precisely so he could address some of the problems the theory had in explaining the moral value of animals. And we can now pretty easily say that modern ethical theories would condemn the wholesale extinction of animal life from the planet, just because humans were gone.

But the questions go deeper than this. American philosopher Mary Anne Warren creates a similar thought experiment. Imagine a lab-grown virus gone wrong, that wipes out all human and animal life. That would be bad. Now, imagine the same virus, but one that wiped out all human, animal and plant life. That would, she thinks, be worse. But why?

What is it that gives plants their ethical status? Do they have intrinsic value – a value in and of themselves, or is their value instrumental – meaning they’re good because they help other things that really matter?

One way to think about this is to imagine a garden on a planet with no sentient life. Is it better, all things considered, for this garden to exist than not? Does it matter if this garden withers and dies?

Or to use a real-life example: who suffered as a result of the destruction of the Jukaan Gorge – a sacred site to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people? Western thought conceptualises this as wrong to destroy this site because it was sacred to people. But for Indigenous philosophical traditions, the destruction was a harm done to the land itself. The land was murdered. The suffering of people is secondary.

Sylvan and others who call for an ecological ethic, believe the failure for Western ethical thought to conceptualise of murdered land or what is good for plants is an obvious shortcoming.

This is revealed by our intuition that the careless destruction of the Last Man on Earth is wrong, even if we can’t quite say why.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Big thinker

Climate + Environment

Big Thinker: Henry Thoreau

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights