Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

In philosophy, vulnerability describes the ways in which people are less self-sufficient than they think.

It explains how factors beyond our control – like other people, events, and circumstances – can impact our ability to live our best lives. The implications of vulnerability for ethics are considerable and wide reaching.

Vulnerability isn’t a new idea. The ancient Greeks recognised tuche – luck – as a goddess with considerable power. Their plays often show how a person’s circumstances alter on the whim of the gods or a random twist of luck (or, if you like, a twist of fate).

This might seem obvious to many people. Of course, external events can affect our lives. If an air conditioning unit falls out of an apartment and lands on my head tomorrow, it’s going to change my circumstances pretty dramatically. But this isn’t the kind of luck philosophers argue is relevant to ethics.

A question of character

The Stoics, a group of ancient Greek philosophers (who are experiencing a revival today) thought only our own choices could affect our character or wellbeing. If I lose my job, my happiness is only affected if I choose to react to my new circumstances badly. The Stoics thought we could control our reactions and overcome our emotions.

The Stoics, much like Buddhist philosophy, thought our main problem was one of attachment. The more attached to external things – jobs, wealth, even loved ones – the more we risk suffering if we lose those things. Instead, they recommended we only be concerned with what we can control – our own personal virtue. For Stoics, we aren’t vulnerable because the only thing that matters can’t be taken away from us: our virtue.

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant had similar thoughts. He believed the only thing that mattered for ethics was that we act with good will. Whatever happened to us or around us, so long as we act with the intention of fulfilling our duties, we’d be in the clear, ethically speaking. It’s our rational nature – our ability to think – that defines us ethically. And thinking is completely within our control.

Both Kant and the Stoics believed the ethical life was invulnerable. External circumstances, like luck or other people, couldn’t affect our ability to make good or bad choices. As a result, whether or not we are ethical is up to us.

Can one ever be self-sufficient?

This idea of self-sufficiency has faced challenges more recently. Many philosophers simply don’t think it’s possible to be self-sufficient to the degree that the Stoics and Kant believed. But some go further – seeing a measure of virtue in vulnerability. For example, vulnerability has become a popular term among psychologists and self-help gurus like Brené Brown. They argue vulnerability, dependency, and luck make up important parts of who we are.

Several thinkers, such as Bernard Williams, Thomas Nagel, and Martha Nussbaum have criticised the idea of self-sufficiency. Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, for example, argues that dependency is in our nature.

We’re all born completely dependent on other people and will reach a similar level of dependency if we live long enough. In the meantime, we’ll be somewhat independent but will still rely on other people for help, for community, and to give meaning to our lives.

MacIntyre thinks this is true even if Kant is right and rational adults are invulnerable to luck (at least in terms of choosing to do their duty). However, against Kant, MacIntyre argues that our capacity for rationality is honed by education and the quality of our education is often beyond our control… as we are dependent on the judgement and circumstances of our parents, society, and so on. Thus, we remain vulnerable in important ways.

Mutual vulnerability

Dr Simon Longstaff, the CEO of The Ethics Centre, has made a different argument in favour of vulnerability. He argues, after Thomas Hobbes, that the reality of mutual vulnerability lies at the heart of how and why we form social bonds. As a result, he argues those who seek to eliminate all forms of vulnerability risk creating a world in which the ‘invulnerable’ show no restraint in their treatment of the vulnerable.

All of this might seem like another academic debate but our understanding of vulnerability has significant consequences for the way we judge ourselves and others. If vulnerability matters, we’re less likely to judge people based on their circumstances. We won’t expect the poor always to lift themselves out of poverty (because unlucky circumstances may deny them the means to do so) nor assume every person struggling with an addiction is necessarily morally deficient. They may simply be stuck with the outcome of events that were (at least initially) beyond their control.

We may also be a little less self-congratulatory. Recognising the ways bad luck can affect people means also seeing how we’ve benefitted from good luck. Rather than assuming all our fortune is the product of hard work and personal virtue, we might be moved by vulnerability to acknowledge how factors beyond our control have worked in our favour.

Finally, vulnerability is one of the concepts that underpins modern debates about privilege and identity politics. If we think people are self-sufficient, we’re less likely to think past injustices have any effect on their present lives. However, if we think factors beyond our control can affect not just our lives but also our character and wellbeing, we might see the claims of minorities in a more open light.

There is a final sense in which vulnerability might be important to ethics. The ‘invulnerable’ person may come to believe their judgement is perfectly formed. They might become ‘immune to doubt’. If people open themselves to the possibility they might be wrong, they live an ‘examined life’ – that is, an ethical life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAY 2017

If you’ve read the Harry Potter series – and let’s face it, many of us have – you will have gained insight into a number of things: the value of friendship, the nature of heroism, the redeeming power of love… the list goes on.

But amidst all the magic, there’s one lesson you might have missed – a lesson which is crucial to the way we think and talk about ethics. In Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Harry is able to secure the titular stone and keep it away from the villainous Voldemort for one simple reason. Even though the stone is powerful, Harry has no desire to use it.

Genius wizard Dumbledore protects the stone with an enchantment. Any person who wanted to use the stone to become immortal would never be able to access it. Only someone who wanted the stone for the right reasons would be successful. The benefits, in other words, were only available to people who didn’t want them.

If your only reasons for committing to ethics are external – because of what ethics will give you – then your motivation will come and go.

Working in ethics, it’s tempting to present the external benefits the ethical life provides to people. In convincing people to set aside self interest and do what’s right, we sometimes appeal to people’s self interest. We use the very logic we’re trying to unwind.

For example, we convince a business to take ethics seriously because it’ll enable them to recruit and keep better staff (it does). We tell a person that living ethically is more likely to make them popular, employable and happy, which it might.

The problem is, if we’re serious about getting people to live ethically, even if we win the argument, we’ve failed in achieving our goal. As soon as someone commits to acting ethically for instrumental reasons – to make money, become popular or whatever – they’re no longer doing it because they think it’s right, they’re doing it because they think it’s effective.

This is a problem. If your only reasons for committing to ethics are external – because of what ethics will give you – then your motivation will come and go. The moment ethics doesn’t help you keep staff or stay popular, your reasons for committing to living an ethical disappear.

Genuine ethical behaviour isn’t only about doing the right thing, it’s about doing it for the right reasons. It means doing what’s ethical because it’s ethical, not because it’ll give us some other advantages.

The debates around torture are a good example of this. Recently, many opponents to torture have argued ‘torture doesn’t work’, so we shouldn’t do it. But this suggests that if torture did work, we wouldn’t have any problem with it. The logic of the argument supports abandoning torture but it also supports undertaking further research to find forms of torture that do work.

But the ethical argument against torture isn’t that it doesn’t work, it’s that even if it did work, it would be wrong. In whatever walk of life you apply it, ethical demands are at their strongest when they force you to choose between what’s beneficial and what’s right.

When someone starts to use the language of ethics to pursue their own ends, they often reveal themselves through hypocrisy. Often, they abandon their so-called values when the costs get too high.

It’s easy to do the right thing when it benefits you. Ethics asks you to set aside what’s convenient, profitable or comfortable and do what’s right. Genuine ethical behaviour isn’t only about doing the right thing, it’s about doing it for the right reasons. It means doing what’s ethical because it’s ethical, not because it’ll give us some other advantages.

In short, ethics is a totally different language to that of self interest, efficiency or effectiveness. It uses different arguments, demands a different kind of thinking and asks us to reconsider our priorities.

It’s only those who are authentically committed to ethics for its own sake who inspire support and trust in the long term.

The reason this is tricky for ethicists is because ethics is a Philosopher’s Stone of sorts. It does offer lots of benefits. But like the enchanted stone in Harry Potter, these benefits are only available to the people for whom ethics isn’t about achieving them.

People value authenticity and loathe hypocrisy. When someone starts to use the language of ethics to pursue their own ends, they often reveal themselves through hypocrisy. Often they abandon their so called values when the costs get too high. When this happens, the good will and support offered by others will disappear.

It’s only those who are authentically committed to ethics for its own sake who inspire support and trust in the long term. Like the magic stone, the benefits of ethics don’t come to those who seek them, they are given to those who deserve them.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 2 MAY 2017

Kwame Anthony Appiah (1954-current) is a British born, American-Ghanaian philosopher.

He is best known for his work on cosmopolitanism, a philosophy that holds all human beings as members of a single, global community. A professor of philosophy and law at New York University, he also writes the popular everyday advice column ‘The Ethicist’ in the New York Times.

We’re responsible for every human being

Because Appiah is a cosmopolitan (meaning “citizen of the world”), he believes we have just as much moral responsibility to our neighbours as we do those halfway across the world. Our obligations to other people transcend national borders, the same way they bypass political ideas and religious beliefs.

However, these obligations shouldn’t mean treating yourself unjustly. Appiah doesn’t advocate for giving everything away so you are worse off than the people you are trying to help.

By focussing too much on eliminating everything bad from the world, Appiah worries we’d fulfil our duties to others at the expense of our duties to ourselves. We’d let go of everything that makes life worth living and meaningful.

He also thinks we’re more productive when we work together. He sees our duties to others as collective rather than individual. The best way to help other people is to unite and ensure nations can provide citizens with what they need to live a good life. This means working with international aid organisations and governments. We’re all in this together.

What unites us is stronger than what divides us

For Appiah, the other basic principle of cosmopolitanism is valuing people’s differences.

“Because there are so many human possibilities worth exploring, we neither expect nor demand that every person or every society should converge on a single mode of life.”

It’s not enough to campaign for international human rights for everyone. These matter, but we should also care about the specific things that give people’s lives meaning – culture, religion, art and so on.

Besides, underneath cultural differences are often shared values and practices. Whether it’s art, friendship, norms of respect or a belief in good and evil, the things that seem so different are often based in ideas we all share.

Moral progress isn’t made by argument

In The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen Appiah argues that seriously unjust practices aren’t defeated by new moral arguments. Instead, they’re defeated by changing attitudes about what’s honourable or shameful.

Appiah points to the overthrow of slavery in Britain and the US as being largely a product of honour. Even though slave owners and traders were aware of moral arguments defending the humanity of their so called stock, that didn’t provide the impetus to change. What really overthrew it was public criticism. The appeal to honour had far more influence than any moral and philosophical ideals.

We can see honour as the middle ground between narrow self interest and self sacrificing altruism. Appiah’s point is a powerful one for people wanting to make change in the world. It would be great if everyone did the right thing for its own sake but sometimes we need a push. Honour, praise and shame can be just the thing.

It’s important to note Appiah thinks honour and ethics are separate. What is seen as honourable isn’t always the same as what’s right. Killing someone in defence of your honour is one clear example.

What’s more, as anyone who has ever logged onto Twitter knows, praise and shame can be abused. Because they are so effective at changing people’s behaviour, it’s tempting to use them when it’s entirely inappropriate. And sometimes this has disastrous effects.

The deeper point is we aren’t purely rational creatures. We work on emotion and our thoughts and actions are driven by cultural attitudes and judgements.

Being aware of this means we might be able harness our communal nature as a force for good and speak both to people’s heads and hearts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: John Rawls

Is there a way to really get our societies to be fair for everyone?

This was the question John Rawls (1921-2002), American political philosopher and author of A Theory of Justice, attempted to answer. His work centres on social justice, privilege, and the distribution of resources in a society.

Rawl’s cake

Imagine it’s your birthday. Your parents decide to throw a party for you and your friends. When it’s time to cut the cake, your mother tells you, “You can cut the cake in whatever way you want to but you can’t choose the slice that you’ll get to have”.

Maybe you’d like a bigger slice of that cake. But since you don’t want to risk getting a small slice, you decide to cut equal sizes for everyone. Now you and your friends are happily munching away, knowing the cake was distributed as fairly as possible.

Fairness demands ignorance

Rawls thought most people’s definition of justice reflected what was good for them instead of anything shared or universal. You might think justice means owning the resources you’ve inherited, or you might think justice is about redistributing them. Whether intentionally or not, we all define justice in a way that gets us a little higher on the ladder. (Big slice for you, small slice for everyone else.)

To get to the core of things, Rawls asks us to imagine a situation where society doesn’t exist yet and no one knows where they will end up in life. What kind of society would you join knowing you could be somehow disadvantaged? If you entered this new world with no parents from childhood, a physical disability, intellectual impairment, financial hardship, or no access to school, what would you want it to be like?

If we each play along with Rawl’s hypothetical, we are likely to imagine fairness in a particular way. Rawls thought we would only join a society where everyone, no matter what circumstances we were born in, has their needs met.

Inequality needs to benefit everybody

Rawls’ conception of justice was based on society’s equal distribution of resources according to two principles.

The first principle is the equality principle. This says everyone should have access to the broadest possible range of civil liberties. Here the only limitation on our freedoms is what is necessary to give other people the same level of freedom. For this system to be fair, you can only be as free as everyone else.

The second principle is the difference principle. Any inequalities in society are only justified under two conditions:

1. There must be equality of opportunity. If there are going to be inequalities – like some people earning more money than others – they should be available to everyone. For example, if access to education increases people’s earning capacity, everyone should have the same access to education so everyone has the same chance to grow their wealth.

2. If there are any social disadvantages, they need to benefit the least advantaged people most. Rawls thought we should only be permitted to grow our personal wealth if we used it to benefit the poor. He wanted to keep the socioeconomically disadvantaged within a reasonable distance of the financially elite by redistributing resources. This was what he saw to be the fairest possible system.

If we were to imagine what the difference principle might look like in practice, it could be policies permitting people to leave inheritance to their children if the state is allowed to tax and distribute it to the poor.

Rawls’ challenge for political philosophy is to question whether a merit based system is as fair as people think. Was it only your work that got you to where you are today or did luck also play a role? If it was the latter, what does that tell us about justice?

Be consistent

Rawls was dedicated to finding the most reasonable political system possible. He believed the first step was to fill our parliaments with reasonable people. It might sound like a no brainer, but by reasonable he meant those with consistency and coherence between their various opinions and beliefs. He called this “reflective equilibrium”.

Imagine someone believes if employees do the same work, they should receive the same wage. Imagine they also opposed striving for pay parity between men and women. Rawls would say this person’s political beliefs are incompatible and therefore unreasonable. To achieve reflective equilibrium, one of these views will have to shift.

In fact, Rawls thought achieving genuine reflective equilibrium was impossible. Instead, we should try to get as near as we can to perfect synergy.

For those of us interested in ethics and politics, the reflective equilibrium is an important idea. We often form opinions based on gut reaction, instinct, or by focussing on the specifics of a situation.

Each of these approaches can at times be unreasonable and inconsistent. By forcing us to test how our different beliefs fit together, Rawls encourages us to do something very basic but very important: make sure our set of beliefs make sense.

First published March 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Brother is coming to a school near you

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: The principle of charity

Ethics Explainer: The principle of charity

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 10 MAR 2017

The principle of charity suggests we should try to understand ideas before criticising them.

Arguments should aim at finding the truth, not winning the fight. This means we should be charitable to people we’re in conversation with by trying to find as much sense in their thinking as we can.

The basic idea behind the principle of charity is thinking well of people. Those we’re debating are intelligent and unlikely to be advancing stupid or illogical ideas. When a charitable listener hears something that doesn’t make sense to them, they will try to work out what was really meant.

Almost everyone takes shortcuts when making arguments. Sometimes we assume people understand us better than they actually do. Maybe we don’t include all of the premises of our argument and make it hard for others to know why we believe what we believe. These and other shortcuts can be an obstacle to productive debate.

Let’s take same sex marriage. Someone might say they support it because “all kinds of love should be treated the same”. Taken literally, this is obviously false. We shouldn’t treat the love a stalker shows to their victim the same way we treat the love a close romantic couple share. They’ve taken a shortcut that affects how their argument could be interpreted.

Using the principle of charity, we would interpret their argument as “all kinds of love between consenting adults should be treated the same”. For a discussion to be successful, we need to do our best to understand what a person means rather than what they explicitly say.

There are a few advantages to using the principle of charity. First, we show respect to our opponents as thinkers and as people. We don’t assume we’re smarter than them at the outset. Instead, we use arguments as an opportunity to learn.

Second, we give ourselves the chance to hone important ethical skills. We exercise imagination and empathy to understand someone else’s view before going on the attack.

Some people might think the principle of charity is another argument for allowing intolerable views to survive unchallenged. This isn’t the case. Charity is only the first step in an argument. First, we listen and only then do we respond. Our response is more likely to be convincing because we’ve taken the opposing argument seriously.

The opposite of the principle of charity is the straw man. This happens when we intentionally misrepresent our opponent’s position to argue against something we can easily defeat. Just like it would be easier to defeat a straw man than a real person, it’s easier to defeat a bad argument we’ve created than someone’s actual position. Unfortunately for those who use it, it’s a logical fallacy.

Winning an argument against a straw man achieves nothing. It might make us feel clever but it doesn’t help anybody’s thinking or understanding. By contrast, charity reminds us in any debate we’re trying to find the truth, not win the argument.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 1 MAR 2017

“Find a job you’ll love and you’ll never work a day in your life!” There are different claims about who coined this phrase but it’s stood the test of time. Like most one-liners, it’s easier said than done.

Most people need two things from their work. They need to earn enough to support all the other areas of their life and they need to feel dignified while doing it. Neither is an easy find.

We tend to know how much income we need but a sense of dignity and meaning can be elusive. You might want creative output, a good work/life balance or a sense of achievement earned through a ‘hard day’s work’. It’s easier to know what kind of work will suit you if you’ve taken Socrates’ advice: know thyself.

Still, insights from philosophy and psychology can help us spot some of the things that tend to give people a sense of meaning in their jobs.

You’ve gotta want it

This is the basic idea behind the ‘find a job you love’ proverb. If you’re doing something you enjoy, it won’t feel like a chore. If you’re motivated by income, prestige or something external, it will be hard to find the work itself fulfilling.

The philosopher Bernard Williams distinguishes ‘internal’ and ‘external’ motivations. We have an external motivation to do something if it would be good for us to do it, whether we want to or not. Internal motivations are things we personally want to do.

For example, if we’re sick, it is good for us to take medicine – that’s an external motivation. If we actually want to get better, we’ve also got an internal motivation. If we want a few more days off work, there’s no internal motive to get better, even though being healthy is better than being sick, generally speaking.

Williams thought external motivations alone couldn’t make us do something. We need some internal motivators to get us off the couch. Williams might not be right. Lots of people probably show up to work because they need to make ends meet but there’s still a lesson in his distinction. Salaries, prestige or fringe benefits won’t be enough to give us a lasting sense of meaning – we need to feel personally engaged with what we’re doing.

Look beyond official duties

Sometimes the core activities of our work won’t give us internal motivation. It might be some unofficial role our job enables us to fulfil.

Psychologist Barry Schwartz uses the example of Luke, a hospital janitor (his official title was “hospital custodian”). It’s unlikely Luke wakes up passionate about working light bulbs and shiny urinals. He found meaning in the parts of his work that extended beyond his official duties:

“The researchers asked the custodians to talk about their jobs, and the custodians began to tell them stories about what they did. Luke’s stories told them that his “official” duties were only one part of his real job, and that another central part of his job was to make the patients and their families feel comfortable, to cheer them up when they were down, to encourage them and divert them from their pain and fear, and to give them a willing ear if they felt like talking.”

The meaningful work Luke performed sat outside he things the hospital paid him for. Despite this, it still gave him enough satisfaction to keep showing up.

See your role in the bigger picture

Hospital janitors are a font of wisdom. Schwartz also describes how Ben and Corey, also janitors, found meaning. They recognised their role within the broader purpose of the hospital – to provide care for people who need it:

“Luke, Ben, and Corey were not generic custodians. They were hospital custodians. They saw themselves as playing an important role in an institution whose aim is to see to the care and welfare of patients.”

They would stop mopping floors if patients were walking the corridors for rehab or hold off from vacuuming when family were sleeping in the patient lounge. They weren’t just keeping things tidy and in working order. In a hospital, cleanliness staves off infection and can save lives. The context and purpose of their work gave it new meaning.

Find space for choice

Peter Cochrane, entrepreneur and technologist, thinks many jobs are taking what’s human out of their human employees. In the documentary The Future of Work and Death, he says, “When I go into companies I often ask the question, ‘Why are you employing people? You could get monkeys or robots to do this job.’ The people are not allowed to think – they are processing. They’re just like a machine.”

At an absolute minimum, feeling dignified at work means feeling like our humanity is being recognised. We want to be treated as people, not things. It’s important we find spaces in our work where we can be autonomous: making decisions for ourselves, exercising our creativity and asserting our ability to think freely.

It’s not a perfect fix

We must acknowledge the limitations of this advice. Our basic needs for food, housing, and the rest require many of us to persevere with work we find undignifying or meaningless.

But if you’re lucky enough to enjoy some choice in where you work and are unhappy in your current role, take a second to think – are you missing one of the above? At least you’ll know what to look for next time!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

James Hird In Conversation Q&A

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ready or not – the future is coming

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

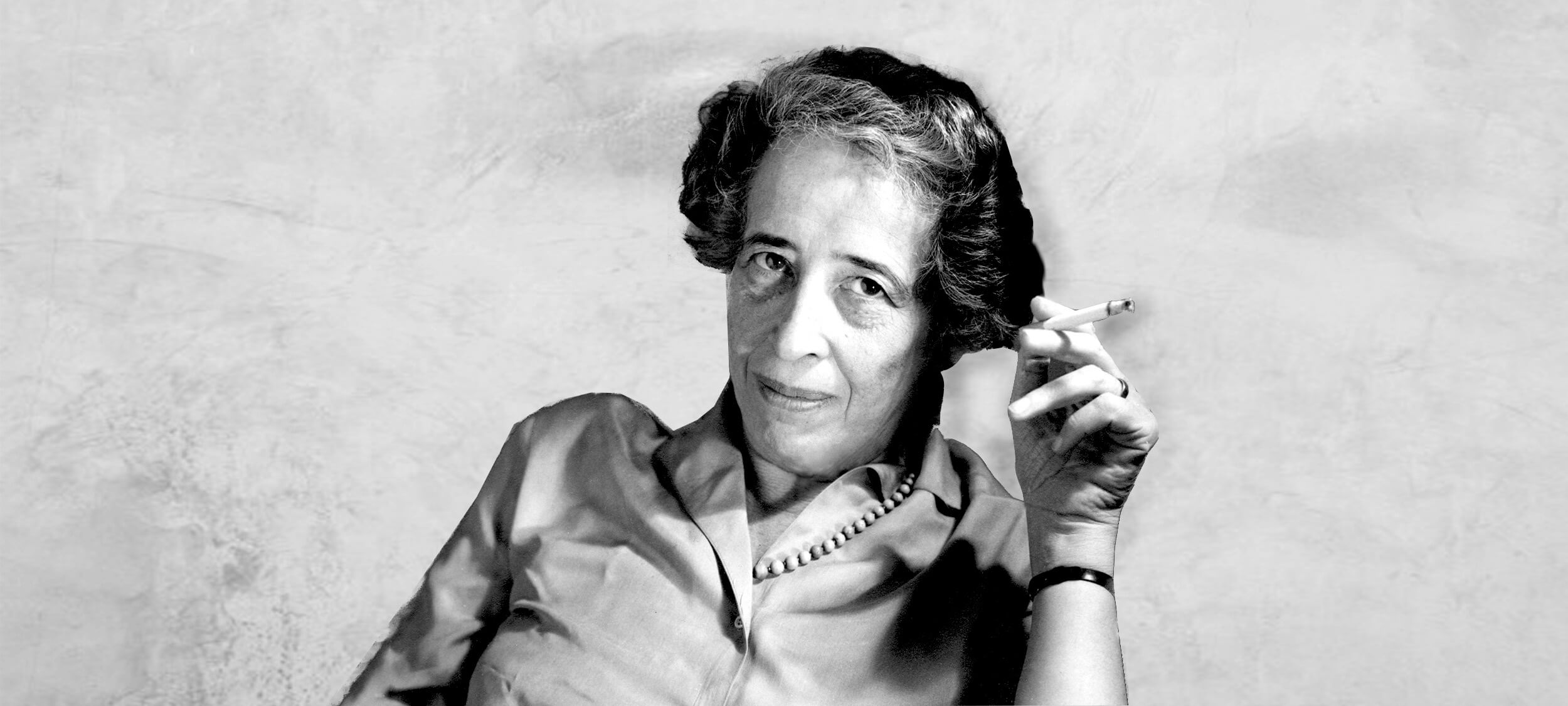

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades.

We are still learning from this seminal political theorist. Her book The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon in 2017, more than 60 years after it was first published.

Evil doesn’t need malicious intentions

Arendt’s most well known idea is “the banality of evil”. She explored this in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat who shared the first name of Hitler, Adolf Eichmann. This later became a book called Eichmann in Jerusalem: Reflections on the Banality of Evil.

In Eichmann, Arendt found a man whose greatest crime was a lack of thinking. His role was to transport Jewish people from German occupied areas to concentration camps in Poland. Eichmann did not kill anyone first hand. He was not involved in designing Hitler’s final solution. But he oversaw the trains that took millions of people to their deaths. They were gassed in chambers or died along the way or in camps due to starvation, overwork, illness, cold, heat, or brutality. Eichmann’s only defence for his involvement in this atrocity was obedience to the law and fulfilling his duty.

Eichmann was so steadfast with this line of reasoning he even referenced the philosopher Immanuel Kant and his theory of moral duty. Kant argued morality was acting on your obligations, not your emotions or what will bring you benefit. For Kant, the person who helps the beggar out of empathy or a belief assisting is a pathway to heaven is not doing an act of good. Kant felt everyone is morally obliged to help the beggar, and they are especially virtuous if they act on this duty despite feeling repulsed or no rewarding sense of doing good.

This does not really suit Eichmann’s argument because Kant was emphasising our ability to reason above emotion. This is precisely where Eichmann failed. We can only guess but it seems likely he did his job without asking questions while feeling a sense of comfort in the safety of his salary and senior position during volatile times.

Arendt believed it was this lack of true thinking and questioning that paved the way to genocide. Evil on the scale of Nazism required far more Adolf Eichmanns than Adolf Hitlers.

Totalitarianism needs political apathy

In studying the causes of WWII, Arendt came across “the masses”. She believed totalitarian regimes needed this to succeed.

By “the masses”, she meant the enormous group of people who are politically disconnected from other members of society. They don’t identify with a particular class, religion, or group. Their lack of group membership deprives them of common interests to demand from government. These people have no interest in politics because they don’t have political clout. They are an unorganised cohort with different, often conflicting desires whose needs are easily disregarded by politicians.

But although these people take no active interest in politics they still hold expectations for the state. If politicians fail those expectations they face “the loss of the silent consent and support of the unorganised masses”. In response, they “shed their apathy” and look for an outlet “to voice their new violent opposition”.

The totalitarian leader emerges from this “structureless mass of furious individuals”. With the political apathy of the masses turned to hostility, leaders will rise by breaking established norms and ignoring the way politics is usually done. Arendt dramatically says they prefer “methods which end in death rather than persuasion”. In short, they’re less likely to build politics up than they are to tear it down because that’s what the masses want.

If this all sounds depressing, there is a solution embedded in Arendt’s writing: political engagement. The masses arise when individuals are lonely and politically disconnected. They are defined by a lack of solidarity or responsibility with other citizens.

By revitalising our political community we can recreate what Arendt sees as good politics. This is when people feel a sense of personal and political responsibility for the nation and are able to band together with other citizens who have common interests. When citizens are connected in solidarity with one another, the mass never occurs and totalitarianism is held at bay.

When work defines you, unemployment is a curse

Not all Arendt’s work was concerned with war and totalitarianism. In The Human Condition, she also offers a general critique of modernity. Drawing on Karl Marx, Arendt thought the industrial age transformed humanity from thinkers into “working animals”.

She thought most people had come to define themselves by their work – reducing themselves to economic robots. Although it’s not a central point of Arendt’s analysis, this reduction is a product of the same forces she sees in the banality of evil. It’s a triumph of ‘doing’ over ‘thinking’ and of humans finding easy ways to define themselves.

Arendt wasn’t just concerned because people were reducing themselves to working drones. She also worried the industrial age which had just redefined them was also about to rob them of their new identities. She believed within a few decades, technology would replace factory jobs. Many people’s work would vanish.

“What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of labourers without labour, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.”

In a time when automation now threatens over half of jobs on average in OECD countries, Arendt’s predictions seem timely. Can we shift our identity away from work in time to survive the massive job reduction to come?

Published February 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2017

Freedom of speech refers to people’s ability to say what they want without punishment.

Most people focus on punishment by the state but social disapproval or protest can also have a chilling effect on free speech. The consequences of some kinds of speech can make people feel less confident in speaking their mind at all.

Since most philosophers agree there is no such thing as absolute free speech, the debate largely focuses on why we should restrict what people say. Many will state, “I believe in free speech except…”. What comes after that? This is where the discussion on what the exceptions and boundaries to free speech are.

Even John Stuart Mill, who is so influential on this topic we need to discuss his ideas at length, thought free speech has limits. You would usually be free to say, “Immigrants are stealing our jobs”. If you say so in front of an angry mob of recently laid off workers who also happen to be outside an immigrant resource centre, you might cause violence. Mill believed you should face consequences for remarks like these.

This belief stems from Mill’s harm principle, which states we should be free to act unless we’re harming someone else. He thought the only speech we should forbid is the kind that causes direct harm to other people.

Mill’s support for free speech is related to his consequentialist views. He thought we should be governed by laws leading to the best long-term outcomes. By allowing people to voice their views, even those we find immoral, society gives itself the best chance of learning what’s “true”.

This happens in two ways. First, the majority who think something is immoral might be wrong. Second, if the majority are right, they’ll be more confident of their position if they’ve successfully argued for it. In either case, free speech will improve society.

If we silence dissenting views, it assumes we already have the right opinion. Mill said “all silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility”.

Accepting the limits of our own knowledge means allowing others to speak their mind – even if we don’t like what they’ve got to say.

As Noam Chomsky said, “If you’re in favour of freedom of speech, that means you’re in favour of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise”.

Free speech advocates tend to limit restrictions on speech to ‘direct’ harms like violence or defamation. Others think the harm principle is too narrow in definition. They believe some speech can be emotionally damaging, socially marginalising, and even descend into hate speech. They believe the speech that causes ‘indirect’ harms should also be restricted.

This leads people to claim citizens do not have the right to be offensive or insulting. Others disagree. Some don’t believe offence is socially or psychologically harmful. Furthermore, they suggest we cannot reasonably predict what kinds of speech will cause offence. Whether speech is acceptable or not becomes subjective. Some might find any view offensive if it disagrees with their own, which would see increasing calls for censorship.

In response, a range of theorists suggest offending is harmful and causes injury. They also say it has insidious effects on social cohesion because it places victims in a constant state of vulnerability.

In Australia, Race Commissioner Tim Soutphommasane is a strong proponent of this view. He believes certain kinds of speech “undermine the assurance of security to which every member of a good society is entitled”. Judith Butler goes further. She believes once you’ve been the victim of “injurious speech”, you lose control over your sense of place. You no longer know where you are welcome or when the next abuse will occur.

For these reasons, those who support only narrow limits to free speech are sometimes accused of prioritising speech above other goods like harmony and respect. As Soutphommasane says, “there is a heavy price to freedom that is imposed on victims”.

Whether you think offences count as harms or not will help determine how free you think speech should be. Regardless of where we draw the line, there will still be room for people to say things that are obnoxious, undiplomatic or insensitive without formal punishment. Having a right to speak won’t mean you are always seen as saying the right thing.

This encourages us to include ideas from deontology and virtue ethics into our thinking. As well as asking what will lead to the best society or which kinds of speech will cause harm, consider different questions. What are our duties to others when it comes to the way we talk? How would a wise or virtuous person use speech?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 JAN 2017

When we say someone or something has dignity, we mean they have worth beyond their usefulness and abilities. To possess dignity is to have absolute, intrinsic and unconditional value.

The concept of dignity became prominent in the work of Immanuel Kant. He argued objects can be valuable in two different ways. They can have a price or dignity. If something has a price, it is valuable only because it is useful to us. By contrast, things with dignity are valued for their own sake. They can’t be used as tools for our own goals. Instead, we are required to show them respect. For Kant, dignity was what made something a person.

Dignity through the ages

Beliefs about where dignity comes from vary between different philosophical and religious systems. Christians believe humans have dignity because they’re made in the image of God. This is called imago dei. Kant believed humans possessed dignity because they’re rational. Others believe dignity is a way of recognising our common humanity. Some say it’s a social construct we created because it’s useful. Whatever its origin, the concept has become influential in political and ethical discourse today.

A question of human rights

Dignity is often seen as a central notion for human rights. The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the “inherent dignity” of “all members of the human family”. By recognising dignity, the Declaration acknowledges ethical limits to the ways we can treat other people.

Kant captured these ethical limits in his idea of respect for persons. In every interaction with another person we are required to treat them as ends in themselves rather than tools to achieve our own goals. We fail to respect people when we treat them as tools for our own convenience or don’t give adequate attention to their needs and wishes.

When it comes to practical matters, it’s not always clear what ‘dignity and respect for persons’ require us to do. For example, in debates around assisted dying (also called assisted suicide or euthanasia) both sides use dignity to argue for opposing conclusions.

Advocates believe the best way to respect dignity is by sparing people from unnecessary or unbearable suffering, while opponents believe dignity requires us never to intentionally kill someone. They claim dignity means a person’s value isn’t diminished by pain or suffering and we are ethically required to remind the patient of this, even if the patient disagrees.

Who makes the rules?

There are also disputes about exactly who is worthy of dignity. Should it be exclusive to humans or extended to animals? And do all animals possess intrinsic value and dignity or just specific species? If animals do have dignity, we’re required to treat them with same respect we afford our fellow human beings.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 ethical life hacks

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JAN 2017

It’s not all tough decisions – walking, sleeping and reading are some ways you can seamlessly strengthen your ethical muscles every day. Here are some activities that can help refine your ethics while you’re busy in your day-to-day life.

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to heightened positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, as Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand that other people’s mental states are different from our own, which is a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drunk driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ that weakens our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The principle of charity

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships