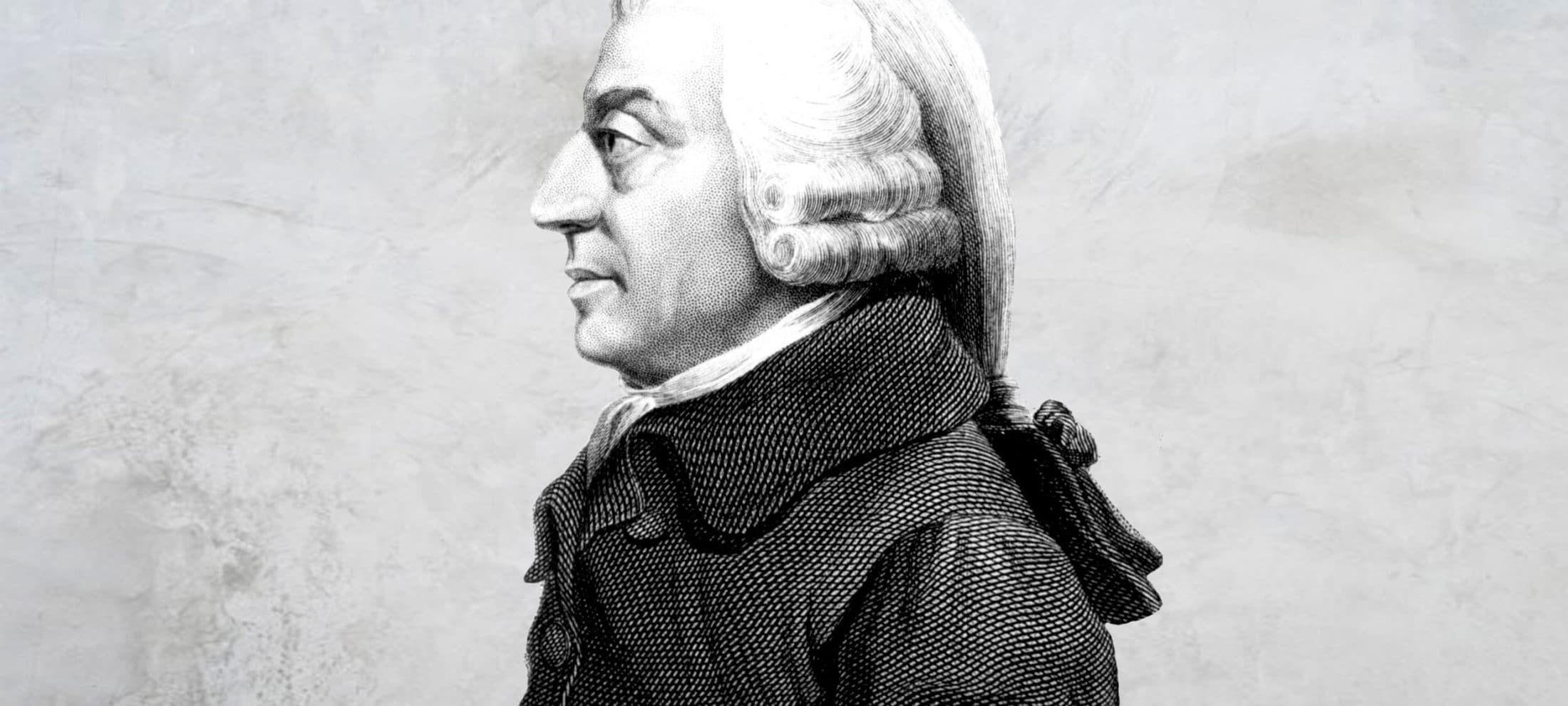

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2018

It’s no exaggeration to say the ideas of Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith (1723—1790) have shaped the world we live in.

By providing the core intellectual framework in defence of free markets, he positioned human liberty and dignity at the centre of trade and money – all for the common good.

Adam Smith, the pioneer

In the 18thcentury, the race to colonise as many resource rich places as possible meant powerful countries were often at war. Companies which added to the wealth of empires were protected by grateful governments, creating trade monopolies that seemed impossible to dismantle. This was the heyday of mercantilism.

Smith noticed how these actions created concentrations of wealth, benefiting the wealthy while the labour class struggled to survive. His first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, argued that the virtues of sympathy and reciprocity could tame greed.

His second, The Wealth of Nations, was about promoting a new way of approaching wealth that was as lucrative as it was just. The approach Smith adopted was multifaceted: economic, defensive, legal, and moral.

Smith argued that countries were competing for the wrong thing. Wealth wasn’t to be found in commodities like gold and silver. It resided in human labour and ingenuity. Smith encouraged countries that would normally look externally for wealth, suppressing the labour class and enslaving others, to look internally instead.

If the labour class could have the freedom to pick their job, all the while knowing the government would leave the money they made well alone, why wouldn’t they work hard at it? They would produce goods and services of even higher quality, and the government could buy these and trade them with each other. Everyone wins.

Collaboration would mean countries wouldn’t need to waste money on defence and war. They could save and accumulate capital, and invest that into better machinery, freeing people to work more productively. The labour class would grow richer, and so would the nation.

Smith stressed that in order for a free market to ensure fair pay for fair work, contracts had to be honoured, people had to keep their word, and governments mustn’t get into debt or take people’s property. Theft, negligence, mistakes, or irresponsible government spending must to be managed by the rule of law. And in the case of foreign powers, defence.

Thus, for Smith – a free market must rest on a sound ethical foundation. Given this, he argued for moral education of a kind that would lead people to be honourable and behave justly. This included the rich. Smith thought that an appeal to ‘enlightened’ self-interest might lead them to act honourably. By lavishing praise, accolades, and rewards on those who spend their wealth in charity, the rich gain the status and rank they really desire.

Adam Smith, the legacy

Claims of plagiarism, usury, inconsistency, racism, and all else aside, the major complaint directed towards Smith is his concept of the “invisible hand”. His observation that self-interested individuals end up benefiting the common good – that they are “led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention.” – has prompted some critics to label him naïve, idealistic, or even immoral.

The following quotation (misattributed to John Maynard Keynes) sums it up: “Capitalism is the astounding belief that the wickedest of men will do the wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone”. But that plays into the Smith = laissez-faire trap, and ignores the safeguards he proposed against human corruption.

Smith did not think greed was good, saying this removed “the distinction between vice and virtue”, nor did he believe business interests and the public interest necessarily coincide. Instead, his perspective was that market competition forced people to act in ways that benefited others, regardless of their intention. And when it failed to do that, an overarching authority should step in. For Smith, markets have no intrinsic value – they are merely tools for the betterment of life for all.

No doubt the world we live in now is vastly different to pre-Industrial Scotland. Mass media, the Internet, the textile industry, factory farms, surveillance, housing prices, offshore tax havens…much would have seemed strange and unfamiliar to Smith. But his work and legacy leave a lesson in economics, ethics, and politics – all the more prescient in a world where the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 20 AUG 2018

Feminist firebrand or second wave scourge? When The Female Eunuch was published to international success, it was obvious Germaine Greer (1939—present) had hit a nerve – something she continues to do.

This article contains language and content that may be offensive to some readers.

Germaine Greer is an Australian writer and public intellectual who rose to international influence with her book published in 1970, The Female Eunuch. It was a watershed text in second wave feminism, a bestseller around the world, and it made Greer a household name.

Greer’s infamously bold voice and sense of humour permeates throughout the book. Her strong character and take no prisoners approach to public debate saw her regularly contribute to panels and broadcast media. Greer was launched into the public eye as a young, bolshie feminist star.

Since then, Greer has written many books spanning literature, feminism and the environment. She has become one of Australia’s most ‘no-platformed’ thinkers. Almost five decades on, we take a look at her contributions to feminist philosophy.

Human freedom is intrinsically tied to sexual freedom

Greer is a liberation, rather than equality feminist. She believed achieving true freedom for women meant asserting their uniquely female difference and “insisting on it as a condition of self-definition and self-determination”.

Greer wanted to be certain about this female difference, and for her, this certainty started with the body.

You can think of Greer’s claims like this:

- Women are sexually repressed.

- Men are not sexually repressed.

- The difference between men and women is their biological sex.

- Biological sex determines if you’re sexually repressed or not.

The second part of her argument is as follows:

- Women are expected to be ‘feminine’.

- Women are sexually repressed.

- The expectation to be ‘feminine’ is sexually repressive.

Greer is scathing in her portrayal of ‘femininity’. She claimed it kept women docile, repressed, and weak. It stifled women’s sexual agency, hence the ‘eunuch’, which was intrinsically tied to their humanity.

Only by liberating women sexually could they remove this imposed submissiveness and embrace the freedom to live the way they wanted.

“The freedom I pleaded for twenty years ago was freedom to be a person, with dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood. Freedom to run, shout, talk loudly and sit with your knees apart.” – Germaine Greer (1993)

A feminist utopia is an anarchist utopia first

In the London Review of Books 1999, Linda Colley wrote, “Properly and historically understood, Greer is not primarily a feminist. More than anything else, she should be viewed as a utopian.”

For Greer, the greatest danger of the widespread female eunuch is not an unfulfilling sex life. It is in her being so concerned with femininity that she is incapable of political action. Greer believed this social conditioning was dire and its enforcers so embedded that revolution rather than reform was required.

Greer called for this revolution to start in the home. She spoke openly about topics that at the time were taboo: menstruation, hormonal changes, pregnancy, menopause, sexual arousal and orgasm. She decried the agents of femininity that she felt kept women trapped: makeup, constricting clothing, feminine hygiene products, stifling marriages, misogynistic literature and female sexual competitiveness. She reserved her greatest fury for widespread consumerism, which she believed kept women dependent on the systems that forged their own oppression.

Like Mary Wollstonecraft before her, Greer argued neither men nor women benefited from this. She called upon women to rebel again these “dogmatists” and create a world of their own. But the solution she presents is exploratory instead of pragmatic. Perhaps women could live and raise their children together, making their own goods and growing their own food. It would be somewhere pleasant like the rolling landscapes of Italy, with local people to tend house and garden. (It’s unclear whether these local people would be liberated too.)

Intellectual criticisms

Greer’s celebration of non-monogamous sex in The Female Eunuch and her derision of Western society’s obsession with sex in Sex and Destiny led critics to label her ideas slipshod and too inconsistent for a public intellectual.

The root of most criticisms and controversies surrounding Greer, tend to stem from her view of the sexes. Like other second wave feminists, she suggested biological sex determined women’s oppression. This stands in stark contrast to the perspectives of third wave feminists and queer theorists, such as Judith Butler, for whom gender’s learned behaviours play the crucial role.

Greer and her contemporaries are often criticised by third and fourth wave feminists for predicating their philosophies on a male/female binary. A binary that does not account for the broad chromosomal spectrums found among intersex people or the many ways in which individuals feel and express their gender.

Infamous commentary

Greer is not the docile feminine woman she warned of in The Female Eunuch. She has long been celebrated for bucking trends and being refreshingly bold and frank. She is also heavily criticised for being rude, offensive and out of touch. She has been described as having “the self-awareness of a sweet potato”, a “misogynist”, and “a clever fool”.

After she extolled the work of Australia’s first female Prime Minister Julia Gillard on an episode of ABC’s Q&A, she was slammed for criticising Gillard’s body and clothing:

“What I want her to do is get rid of those bloody jackets … They don’t fit. Every time she turns around you’ve got that strange horizontal crease which means they cut too narrow in the hips. You’ve got a big arse Julia…”

Social media lit up with calls for Greer to “shut up” after she linked rape and bad sex in the age of #MeToo:

“Instead of thinking of rape as a spectacularly violent crime – and some rapes are – think about it as non-consensual, that is, bad sex. Sex where there is no communication, no tenderness, no mention of love. We used to talk about lovemaking.”

It is probably Greer’s public statements around transgender women that have attracted the most protest. In an interview after an intense no-platforming campaign to cancel a lecture Greer was scheduled to give at Cardiff University on women and power in the 20th century, she said, “Just because you lop off your penis and then wear a dress doesn’t make you a fucking woman”.

This sentiment probably links with Greer’s ideas on sexed bodies. A sympathetic reading of the comment might see it as one about being born into oppression – a rather second wave feminist sentiment that echoes the racial and queer politics of the same era. An idea that’s sometimes cited as analogous to Greer’s controversial comment is that you cannot understand what it is to be black, unless you were born black and experienced discriminations since the day of your birth. Perhaps she was suggesting we cannot understand the oppression experienced by women and girls unless we are born into a female body. Perhaps not. Either way, the comment was received as incredibly offensive and naive to transgender women’s experiences.

“People are hurtful to me all the time. Try being an old woman. I mean for goodness sake! People get hurt all the time. I’m not about to walk on eggshells.” – Germaine Greer, 2015

Greer and second wave feminists generally are at odds with intersectional feminism which is prominent today. Intersectional feminism holds that many factors beyond sex marginalise people – age, race, nationality, disability, class, faith, sexual orientation, gender identity… Different women will be oppressed to varying degrees.

Whether Greer is a trailblazer or tactless provocateur, it is doubtless her ideas have influenced the political and personal and landscapes of gender relations and feminist thinking.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 JUL 2018

Women’s oppression comes down to biological differences – so get rid of them. If you can put a man on the moon, you make a mechanical womb and gestate a baby without a woman.

These were the arguments of Shulamith Firestone (1945—2012), writer, artist and feminist, whose book, The Dialectic of Sex, argued the structure of the biological family was primarily to blame for the oppression of women.

With a radical and uncompromising vision, she advocated for the development of reproductive technologies that would free women from the responsibilities of childrearing, dismantle the hierarchy of family life, and set the foundations for a truly egalitarian society.

The girlhood of a radical thinker

Firestone was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in Ottawa, Canada in 1945. Her mother was a Holocaust survivor that came from a lineage of rabbis and scholars, and her father was a travelling salesmen.

Firestone possessed a fierce intelligence and strong will from a young age and regularly came into conflict with the stringent gender norms that her religious father imposed. When she questioned why she had to make her brother’s bed in the morning, her father replied, “because you’re a girl.”

In the late 1960s, Firestone left home to study art in Chicago and then New York, where she joined left wing political movements and came of age intellectually. While she was free from her father’ tyranny, she saw the same sexism that had controlled her life at home across all areas of society. It was a time when women held almost no major elected positions, abortion was illegal, rape a stigma to be borne alone, and home making seen as a woman’s highest calling.

As a response to this, Firestone began studying history and feminist literature, hoping to understand the root cause of women’s oppression, which resulted in the publication of The Dialectic of Sex in 1970.

The Dialectic of Sex

While other feminist writers and philosophers proposed that the cause of women’s oppression was, at root, political and cultural, Firestone made a radical departure, positing that the inequality between men and women stemmed from fundamental biological differences – most notably that women had to carry, give birth to, and nurse babies.

This biological reality, Firestone argued, created an “unequal power distribution” within families. Because women were responsible for a child’s care, they became dependant on men to provide for them while they were unable to leave the home. This in turn gave rise to a hierarchy within the family in which babies were dependant on mothers, mothers on their husbands, and husbands on no one.

Firestone argued that over the course of human history, society itself had come to mirror the structure of the biological family and was the source from which all other inequalities developed.

Women were expected to stay at home and care for children, which held them back from becoming financially independent and achieving political agency.

If the feminist movement was to overcome male domination, it had to reckon with the fundamental biological reality that underpinned it.

“The end goal of feminist revolution must be… not just the elimination of male privilege, but of the sex distinction itself.”

While questioning the fundamental biological conditions was not conceivable in previous centuries, Firestone said the great advancements that had accrued in science and technology in the 20th century made it possible to imagine a future in which the reproductive role of women was outsourced to “cybernetic machines”. She believed if the same energy and resources were put into developing reproductive technologies as had been put into other projects, like sending a human to the moon, then it could be achieved in decades.

What held this research back, Firestone suggested, was institutional resistance from men in positions of power who did not want to disrupt the existing hierarchy.

“The problem becomes political … when one realises that, though man is increasingly capable of freeing himself from the biological conditions that created his tyranny over women and children, he has little reason to want to give this tyranny up.”

The true feminist cause, then, was to demand reproductive technology that could free women from what had previously been a biological destiny. Firestone believed if this was achieved, and reproduction was no longer the sole responsibility of women and their bodies, the family would undergo a radical restructuring, a flattening of the patriarchal hierarchy, which would then be mirrored in a more egalitarian society itself.

Brilliant and preposterous

The Dialectic of Sex caused a stir from the moment it was published. It was hard for critics to deny Firestone’s prodigious intellect, but they wrote off her ideas as too radical, too utopian, and too ridiculous to warrant serious engagement. Her theory of gender inequality was called “brilliant” and “preposterous” in the same review by one New York Times critic.

The book’s publication caused a greater rift between Firestone and her family, and her staunch line on biological inequality alienated her from some feminist groups. By the 1980s, when the backlash against radical feminism had taken hold of mainstream American culture, Firestone retreated to a small apartment in Manhattan where she spent her days painting in isolation. She was found dead in August 2012 at the age of 67.

In the 50+ years since Firestone published The Dialectic of Sex, we have seen enormous and rapid technological developments in many areas, and yet reproductive technologies like artificial wombs are still seen as an unlikely and unwanted science from a dystopian sci-fi future. Our culture, for the most part, still associates artificial wombs with the 1932 novel Brave New World, in which Aldous Huxley imagined a future where foetuses are grown in “bottles” in vast state incubators. For Huxley, the idea of severing the biological tie between mother and child was the centrepiece of his dystopian vision, the essential metaphor of a society that had become ethically set adrift.

Reading Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex – a brilliant, passionate and uncompromising book – forces us to confront that the way technology progresses is informed by political motivations, and that science is not neutral, but can be used to reinforce and perpetuate unequal distributions of power.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

“The pen would smoothly write the things it knew, but when it came to love it split in two, a donkey stuck in mud is logic’s fate – Love’s nature only love can demonstrate.” – Rumi

Rumi (1207—1273) has long been recognised as one of the most important contributors to Islamic literature and Sufism, the spiritual and mystic element of Islam. His enormous collection of mystical poetry is considered among the best that has ever been produced. His seminal text is the Masnavi, a six book poem written in rhyming couplets. It is so revered as an expression of Godly knowledge that it is referred to as “The Koran in Persian”.

What is Sufism?

To understand Rumi, you need to understand Sufism. It is often misrepresented as a sect, school, or deviant form of Islam but is better described as a distinct stream in Islamic spirituality. Sufism was first embodied by Muhammad and his early followers, then medieval scholars like Abu Hamid Al-Ghazzali, Ibn Arabi, and of course, Rumi.

Sufism is characterised by its focus on moral cultivation and establishing a personal connection to God through reforming, disciplining, and purifying the ego. It seeks to attain this intuition of God through disciplines that practice an austere lifestyle known as ascetism. One example of this is dhikr, a form of worship where you become absorbed in rhythmic repetitions of God’s name.

Sufism seeks a type of knowledge outside worldly intellect – one that is intuitive and is inextricably tied to the Divine.

Life of Rumi

Rumi, known in Iran and Central Asia as Mowlana Jalaloddin Balkhi, was born in 1207 in the province of Balkh, which is now the border region between Afghanistan and Tajikistan. His family left when he was a child shortly before Genghis Khan and his Mongol army arrived. They settled permanently in Konya, central Anatolia, which was formerly part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Rumi was probably introduced to Sufism through his father, Baha Valad, a popular preacher who also taught Sufi piety to a group of disciples.

The turning point in Rumi’s life came in 1244 when he met a wandering Sufi in Konya called Shamsoddin of Tabriz. Shams, as he was most often referred to by Rumi, taught him the most profound levels of Sufism, transforming him from a devout religious scholar to an ecstatic mystic.

Rumi died on 17 December 1273 shortly after completing his work on the Masnavi. His passing was deeply mourned by the citizens of Konya, including the Christian and Jewish communities. His disciples formed the Mevlevi Sufi order and named it after Rumi, whom they referred to as ‘Our Master’ (which translates to Mevlana in Turkish and Mowlana in Persian). They are better known in the West as the Whirling Dervishes, because of the distinctive dance they now perform as one of their central rituals.

Rumi’s death is commemorated annually in Konya, attracting pilgrims from all corners of the globe and every religion. The popularity of his poetry has risen so much in the last couple of decades that the Christian Science Monitor identified him as the most published poet in America in 1997 and UNESCO declared 2007 to be the Year of Rumi.

Overvaluing intellect

Rumi, like most Sufis, praised the intellect and considered its refinement a religious imperative. But he was clear about the types of knowledge he believed it could sufficiently possess. He considered o domain the sentimental and material world, not the theoretical and metaphysical one.

Rumi’s caution was this: when one relies solely on their own intellect to understand Being and Reality, they risk confining their understanding to a mortal and ultimately finite resource – themselves. He regarded it a folly of the ego to believe one’s intellect limitless and warned against reducing God to abstract puzzles in order to maintain that belief. Rumi scorned placing the intellect too high and pursuing knowledge for knowledge’s own sake.

“He knows a hundred thousand superfluous matters connected with the (various) sciences, (but) that unjust man does not know his own soul.

He knows the special properties of every substance, (but) in elucidating his own substance (essence) he is (as ignorant) as an ass.” – Rumi

The transcendence of man

So, if intellect isn’t enough, what is? Rumi would say, ‘Divine love.’

This divine love can also be translated as grace or friendship with God. In the Islamic worldview, humanity is unique in its capacity to autonomously know God, and this gives people an honoured status. Even so, no human can achieve divine love out of their own efforts. They can only be granted it.

Rumi was of the view that seeking essential knowledge – knowledge about the essence of humanity – was a way one might be granted divine love. It was the best type of knowledge, because it was tied to questions of meaning, purpose, and death. In other words, knowing yourself was a means of knowing God.

According to the Sufis, knowledge of God comes in three levels: material, conceptual, and experiential. Think of it as the different between knowing an apple exists, reading a detailed Wikipedia page about it, and eating one in the flesh. All three are different forms of knowing what an apple is – but each deepens in understanding. The last level is transformative in a way the other two are not. Try explaining what an apple tastes like to someone who has never had one. You may come very close, but they will never know what you mean unless they take a bite themselves.

Likewise, the Sufis believed that the highest knowledge of God was something that could only be experienced. To read and contemplate upon God or the universe was one thing. But experiencing God was something totally different, something impossible to intellectualise.

Rumi believed manifesting the four virtues – courage, wisdom, and temperance, which when balanced, lead to perfect justice, the fourth virtue – would lead to some form of transcendence above the hubbub of life’s claims and counterclaims. But when every human being’s views cannot be divorced from their experience, how was this possible?

For Rumi, this highlighted humanity’s dependence on God. Only a friend of God, or Wali, could be objective enough to see truth and loving enough to be just.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

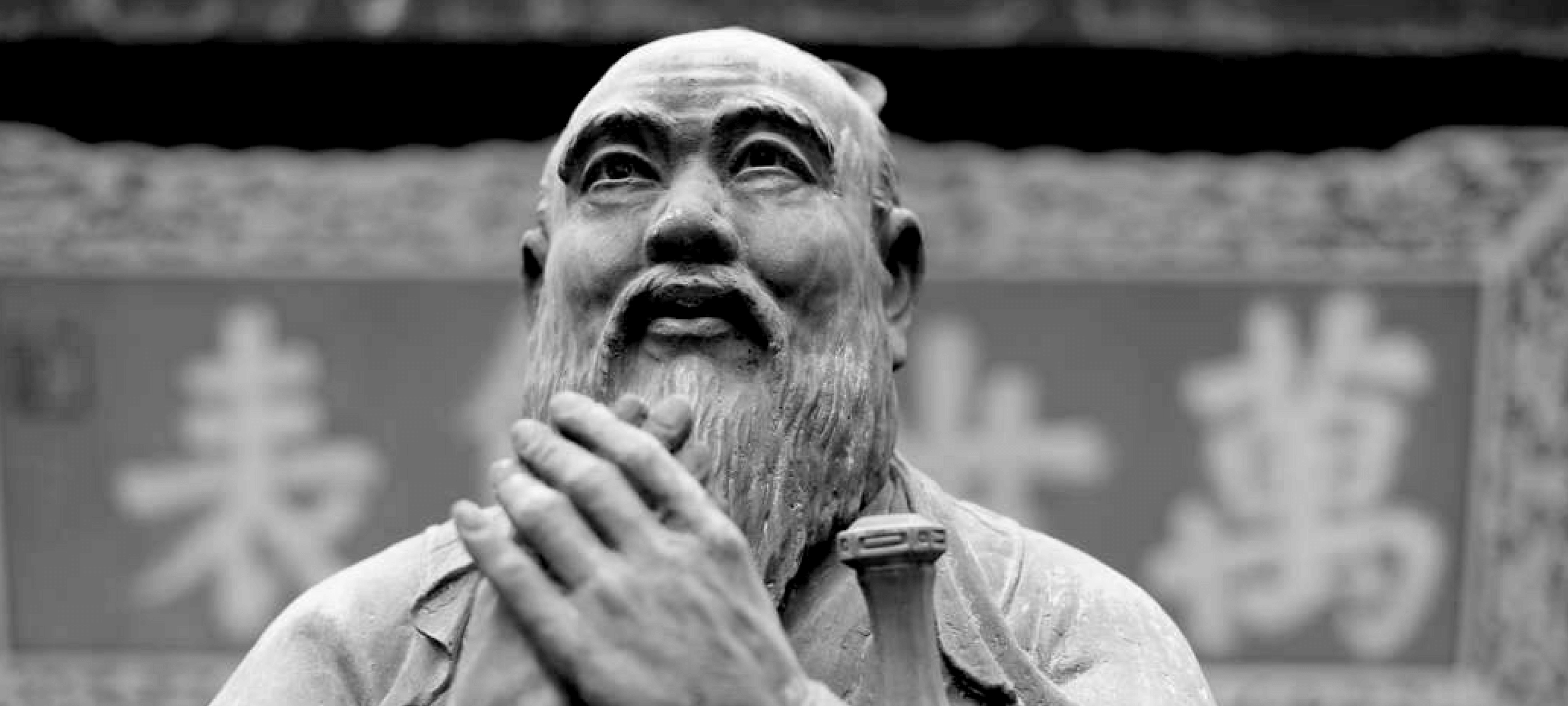

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

Confucius (551 BCE—479 BCE) was a scholar, teacher, and political adviser who used philosophy as a tool to answer what he considered to be the two most important questions in life… What is the right way to rule? And what is the right way to live?

While he never wrote down his teachings in a systematic treatise, bite sized snippets of his wisdom were recorded by his students in a book called the Analects.

Underpinning Confucian philosophy was a deeply held conviction that there is a virtuous way to behave in all situations and if this is adhered to society will be harmonious. Confucius established schools where he gave lectures about how to maintain political and personal virtue.

“It is virtuous manners which constitute the excellence of a neighborhood.”

His ideas set the agenda for political and moral philosophy in China for the next two millennia and are emerging once again as an influential school of thought.

Humble beginnings

Confucius was born in 551 BC in a north-eastern province of China. His father and mother died before he was 18, leaving him to fend for himself. While working as a shepherd and bookkeeper to survive, Confucius made time to rigorously study classic texts of ancient Chinese literature and philosophy.

At the age of 30, Confucius began teaching some of the foundational concepts he formulated through his studies. He developed a loyal following and quickly rose up the political ranks, eventually becoming the Prime Minister of his province.

But at the age of 55 he was exiled after offending a higher ranking official. This gave Confucius an opportunity to travel extensively around China, advising government officials and spreading his teachings.

He was eventually invited back to his home province and was allowed to re-establish his school, which grew to a size of 3000 students by the time he died at age 72.

The golden age

Underpinning much of Confucius’ thought was a belief that Chinese society had forgotten the wisdom of the past and that it was his duty to reawaken the people, particularly the young, to these ancient teachings.

Confucius idealised the historical Western Zhou Dynasty, a time, he claimed, when living standards were high, people lived and worked in peace and contentment, the leaders carried out their duties in accordance with their rank, and the social order was stable and harmonious.

Confucius devoted his life to teaching the wisdom of this ancient society to his contemporaries in the hope of reinventing it in the present. For this reason, he didn’t claim to be an original thinker, but a receptacle of past wisdom. “I transmit but do not innovate”, he said.

Dao, de, and ren

While Confucius never wrote a systematic philosophical treatise, there are three intertwined concepts that run through his philosophy: Dao, De, and Ren.

Dao: Confucius interpreted Dao to mean a Way of living, or more specifically the right Way of living. This was not a concept he made up. It was already a central part of Chinese belief systems about the natural order of the universe. Dao is a slippery but profound concept suggesting there is a singular Way to live that can be intuited from the universe, and that all of life should be directed towards living this Way. If the Way is followed, the individual and society will be in perfect harmony.

De: Confucius saw De as a type of virtue that lay latent in all humans but that had to be cultivated. It was the cultivation of this virtue, Confucius believed, that allowed a person to follow the Way. It was in family life that people learned how to cultivate and practice virtuous behaviours. In fact, many of the main Confucian virtues were derived from familial relationships. For example, the relationship between father and son defined the virtue of piety and the relationship between older and younger siblings defined the virtue of respect. For this reason, Confucian ethics did not leave much room for an individual to exist outside of a family structure. Knowing where you stood in your family and your society was key to living a virtuous life.

Ren: While most Confucian virtues were cultivated within a strict social and family structure, ren was a virtue that existed outside this dynamic. It can be translated loosely as benevolence, goodness, or human-heartedness.

Confucius taught that the ren person is one who has so completely mastered the Way that it becomes second nature to them. In this sense ren is not so much about individual actions but what type of person you are. If you perform your familial duties but do not do so with benevolence, then you are not virtuous. Ren was how something was done, rather than the act itself.

Contemporary influence and relevance

Confucius’ influence on Chinese society during his life and in the two millennia since has been enormous. His sound bite like philosophies became China’s handbook on politics and its code of personal morality.

“He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.”

It wasn’t until Mao’s Cultural Revolution that some of the basic tenets of Confucian ethics were publicly denounced for the first time. Mao was future oriented and utopian in his politics, and so Confucius’ idea of governance and ethics based in the ancient classics was considered dangerous and subversive. In fact, Mao’s Red Guards referred to the old sage as “The Number One Hooligan Old Kong”.

But in the past decade, the Communist Party has realised Confucius’ teachings might be useful again. The surge of wealth that has accompanied free market capitalism in China has meant that many of Mao’s ideologies no longer make sense for the government. This has prompted a resurgence of State led interest in Confucius as an alternative ideological underpinning for the current government.

While this is seen by many as a way for China to build a political future based on its philosophical past, others feel that the Communist Party has emphasised Confucian ideas about hierarchical social structure and obedience, while sidelining notions of virtue and benevolence.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

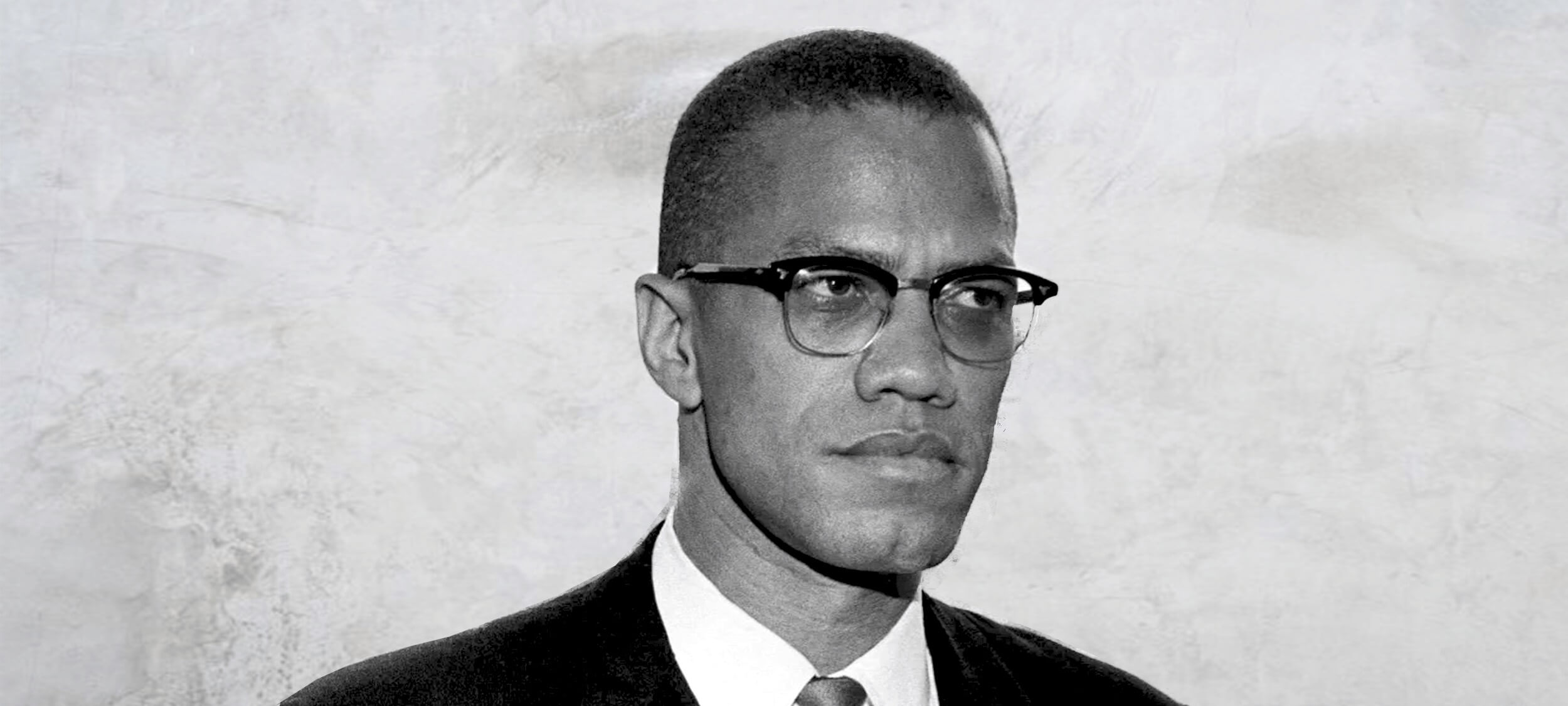

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 7 FEB 2018

Malcolm X (1925—1965) was a Muslim minister and controversial black civil rights activist.

To his admirers, he was a brave speaker of an unpalatable truth white America needed to hear. To his critics, he was a socially divisive advocate of violence. Neither will deny his impact on racial politics.

From tough childhood to influential adult

Malcolm X’s early years informed the man he became. He began life as Malcolm Little in the meatpacking town of Omaha, Nebraska before moving to Lansing, Michigan. Segregation, extreme poverty, incarceration, and violent racial protests were part of everyday life. Even lynchings, which overwhelmingly targeted black people, were still practiced when Malcolm X was born.

Malcolm X lost both parents young and lived in foster care. School, where he excelled, was cut short when he dropped out. He said a white teacher told him practicing law was “no realistic goal for a n*****”.

In the first of his many reinventions, Malcolm Little became Detroit Red, a ginger-haired New York teen hustling on the streets of Harlem. In his autobiography, Malcolm X tells of running bets and smoking weed.

He has been accused of overemphasising these more innocuous misdemeanours and concealing more nefarious crimes, such as serious drug addiction, pimping, gun running, and stealing from the very community he publicly defended.

At 20, Malcolm X landed in prison with a 10 year sentence for burglary. What might’ve been the short end to a tragic childhood became a place of metamorphosis. Detroit Red was nicknamed Satan in prison, for his bad temper, lack of faith, and preference to be alone.

He shrugged off this title and discarded his family name Little after being introduced to the Nation of Islam and its philosophies. It was, he explained, a name given to him by “the white man”. He was introduced to the prison library and he read voraciously. The influential thinker Malcolm X was born.

Upon his release, he became the spokesperson for the Nation of Islam and grew its membership from 500 to 30,000 in just over a decade. As David Remnick writes in the New Yorker, Malcolm X was “the most electrifying proponent of black nationalism alive”.

Be black and fight back

Malcolm X’s detractors did not view his idea of black power as racial equality. They saw it as pro-violent, anti-white racism in pursuit of black supremacy. But after his own life experiences and centuries of slavery and atrocities against African and Native Americans, many supported his radical voice as a necessary part of public debate. And debate he did.

Malcolm X strongly disagreed with the non-violent, integrationist approach of fellow civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. The differing philosophies of the two were widely covered in US media. Malcolm X believed neither of King’s strategies could give black people real equality because integration kept whiteness as a standard to aspire to and non-violence denied people the right of self defence. It was this take that earned him the reputation of being an advocate of violence.

“… our motto is ‘by any means necessary’.”

Malcolm X stood for black social and economic independence that you might label segregation. This looked like thriving black neighbourhoods, businesses, schools, hospitals, rehabilitation programs, rifle clubs, and literature. He proposed owning one’s blackness was the first step to real social recovery.

Unlike his peers in the civil rights movement who championed spiritual or moral solutions to racism, Malcolm X argued that wouldn’t cut it. He felt legalised and codified racial discrimination was a tangible problem, requiring structural treatment.

Malcolm X held that the issues currently facing him, his family, and his community could only be understood by studying history. He traced threads between a racist white police officer to the prison industrial complex, to lynching, slavery, and then to European colonisation.

Despite his great respect for books, Malcolm X did not accept them as “truth”. This was important because the lives of black Americans were often hugely different from what was written about – not by – them.

Every Sunday, he walked around his neighbourhood to listen to how his community was going. By coupling those conversations with his study, Malcolm X could refine and draw causes for grievances black people had long accepted – or learned to ignore.

We are human after all

Dissatisfied with their leader, Malcolm X split from the Nation of Islam (who would go on to assassinate him). This marked another transformation. He became the first reported black American to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. In his final renaming, he returned to the US as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

On his pilgrimage, he had spoken with Middle Eastern and African leaders, and according to his ‘Letter from Mecca’ (also referred to as the ‘Letter from Hajj’), began to reappraise “the white man”.

Malcolm X met white men who “were more genuinely brotherly than anyone else had ever been”. He began to understand “whiteness” to be less about colour, and more about attitudes of oppressive supremacy. He began to see colonialist parallels between his home country and those he visited in the Middle East and Africa.

Malcolm X believed there was no difference between the black man’s struggle for dignity in America and the struggle for independence from Britain in Ghana. Towards the end of his life, he spoke of the struggle for black civil rights as a struggle for human rights.

This move from civil to human rights was more than semantics. It made the issue international. Malcolm X sought to transcend the US government and directly appeal to the United Nations and Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead.

In a way, Malcolm X was promoting a form of globalisation, where the individual, rather than the nation, was on centre stage. Oppressed people took back their agency to define what equality meant, instead of governments and courts. And in doing so, he linked social revolution to human rights.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

McKenzie… a fractured cog in a broken wheel

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Philosophy had a big moment in 20th century Europe. Christian mysticism? Not so much.

Meet Simone Weil (1909—1943) – French philosopher, political activist, Christian mystic and enfant terrible. Described by John Berger as a “heretical theologian”, Albert Camus as “the only great spirit of our times”, and André Weil (her brother) as “the greatest pain in the arse for rectors and school directors”, Weil was – and remains – one of philosophy’s more divisive characters

Uprootedness

According to Weil, post-World War II France was adrift in a deep malaise she called uprootedness. She argued France’s lack of connectedness to its past, its land, and its community had culminated in its defeat by Germany. Her solution? To find spirituality in work.

This would look different in city and country. In urban areas, treating uprootedness meant finding a motivation for work other than money.

Weil admitted that for low income and unemployed adults in war ravaged France, this would be impossible. Instead, she focused on their children. Reviving the original Tour de France, encouraging apprenticeships, and bringing joy back into study were her recommendations. This way, work could be intriguing and compelling. Even “lit up by poetry”.

For those in the country, uprootedness looked like boredom and an indifference to the land. Optional studies of science, religion, more apprenticeships and cultivating a strong need to own land was essential. To remember the water cycle, photosynthesis and Biblical shepherds while working could only invoke awe, Weil surmised. Even the fatigue of labour would turn poetic.

Her vision for reform extended to French colonialism. This was a source of deep shame for Weil, admitting that she could not meet “an Indochinese person, an Algerian, a Moroccan, without wanting to ask his forgiveness”. She saw uprootedness most acutely in those whose homelands had been invaded. It was also a clear example of the cyclical nature of uprootedness: for the fiercest invaders were uprooted people uprooting others.

Attention over will

The spirituality of academic work was just as important to Weil. In practice, this looked like attention. She defined attention as the capacity to hold different ideas without judgement. In doing so, the student would be able to engage with ideas and slowly land on an answer.

She argued that when a student is motivated by good grades or social ranking, they arrest their development of attention and lose all joy in learning. Instead, they pounce on any semblance of answer or solution, even if half-formed or incorrect, to seem impressive. Social media, anyone?

According to Weil, true knowledge could not be willed. Instead, the student should put their efforts into making sure they paid attention when it arrived.

Weil believed humanity’s search for truth was their search for nearness to God or Christ. If God or Christ was the source of ‘Truth’, every new piece of knowledge or fact learned would refer to them. Therefore, in each student’s instance of unmixed attention – to a geometry problem, a line of poetry, or a cry for help from someone in need – was an opportunity for spiritual transformation.

This detachment from social mores and movement away from the ego characterised her mysticism. It makes a lot of sense then, that Weil considered the height of attention to be prayer.

Obligations over rights

Weil believed that justice was concerned with obligations, not rights. One of her criticisms of political parties lay in their language of rights, calling it “a shrill nagging of claims and counter-claims”.

Justice, for Weil, consisted of making sure no harm is done to one another. Weil asserted that when the man who is hurt cries ‘why are you hurting me?’ he invokes the spirit of love and attention. When the second man cries ‘why has he got more than I have?’ his due becomes conditional on power and demand.

The obligation of justice, Weil noted, is fundamentally unconditional. It is eternal and based upon a duty to the very nature of humanity. In a sense, what Weil is describing is the Golden Rule, found in every major religious tradition and every strand of moral philosophy – to treat others as you would like to be treated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Bill Mollison

Bill Mollison (1928—2016) was an Australian ecologist and the ‘father of permaculture’, a type of agricultural design and practice he created, named and taught.

Having co-wrote Permaculture One with his student and colleague David Holmgrem, Mollison later founded the Permaculture Institute of Tasmania and taught his Permaculture Design Course and Certificate (PDCC) all around the world.

Today, his philosophy has reached millions. His commitment to ethics brings philosophy back into the marketplace and onto the farm – down to its earthworms and well-tilled soil.

What is permaculture?

Permaculture is an ethical design framework for sustainable farming. It combines traditional farming methods of Indigenous and Aboriginal communities with renewable technologies and low-energy materials. Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer and creator of “Do-nothing Farming”, is cited as another influence on Mollison’s farming philosophy.

Mollison believed that farming monocultures, like corn, or wheat, was unsustainable. Instead, he called for ‘food forests’ – a varied collection of plant and tree species that support equally as diverse animal life.

Like a delicate structure of checks and balances, the little relationships formed in such an ecosystem would keep it self-sufficient. According to Mollison, once complete, a successful permaculture design wouldn’t need any human touch at all.

What’s wrong with what we’ve got now?

Because monocultures are more efficient, fast and easy to harvest, they’ve been the go-to for industrial farming. But, according to Mollison, their future is limited, with no means to reproduce the same healthy ecosystem it profits from. In fact, it’s often expected to meet the surplus demand of nations that already have enough food.

Mollison considered this form of agriculture as unethical, self-destructive and “temporary”. Rather than people being relied on to provide yields, he wanted to make us another part of the agricultural web. No more, no less.

This, along with permaculture’s three core ethics (earth care, people care and fair share), would transform how plants, animals and humans all interact with each other. People – not just farmers – would turn into active stewards of the earth. The social and economic needs of interdependent communities would be satisfied and looked after, with global surplus distributed to those most in need.

Some people find his views noble, but unrealistic. Indeed, his repositioning of farming as political might be novel. But applying ethics to fulfil basic needs of food and shelter, to Mollison, is essential:

“The greatest change we need to make is from consumption to production, even if on a small scale, in our own gardens. If only 10% of us can do this, there is enough for everyone. Hence the futility of revolutionaries who have no gardens, who depend on the very system they attack, and who produce words and bullets, not food and shelter.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

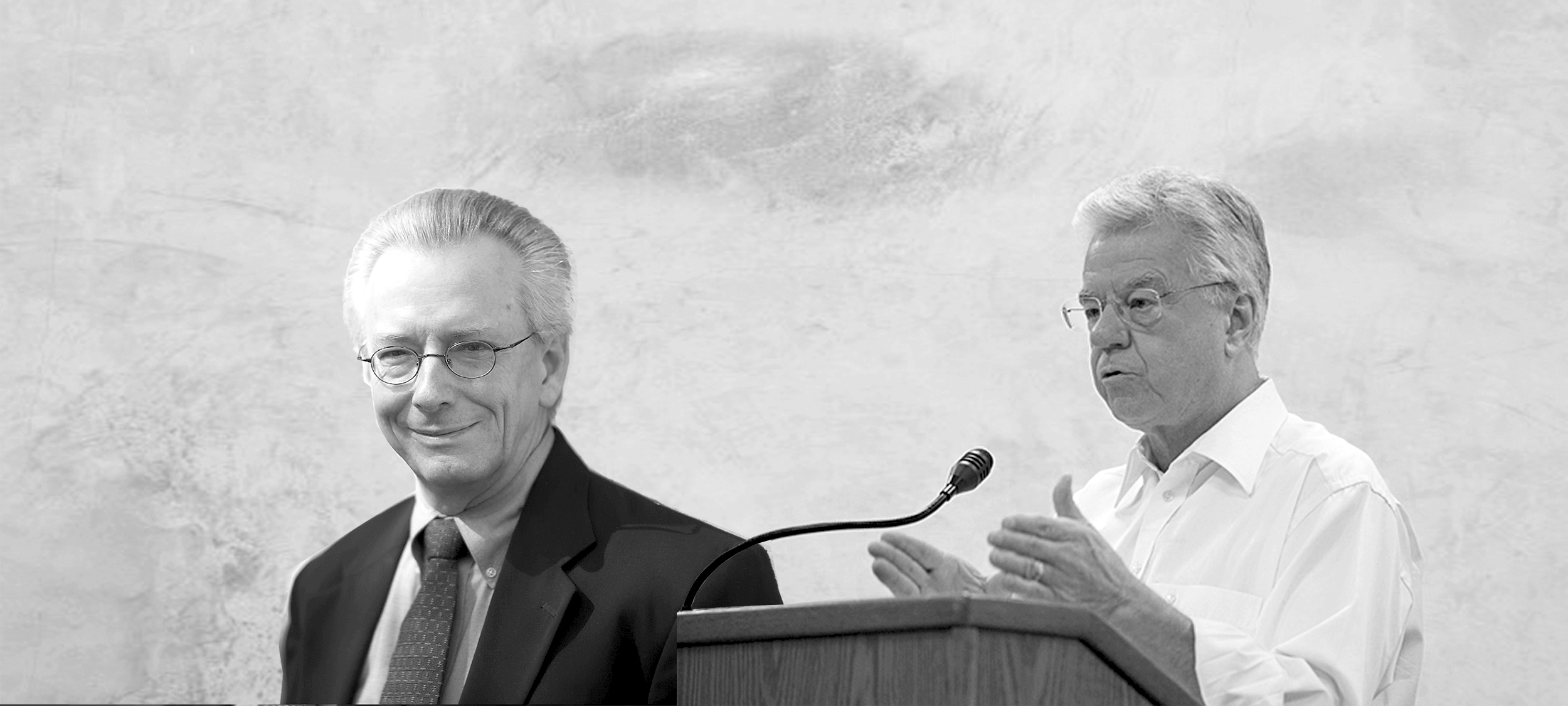

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 1 DEC 2017

Thomas L Beauchamp (1939—present) and James F Childress (1940—present) are American philosophers, best known for their work in medical ethics. Their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics was first published in 1985, where it quickly became a must read for medical students, researchers, and academics.

Written in the wake of some horrific biomedical experiments – most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where hundreds of rural black men, their partners, and subsequent children were infected or died from treatable syphilis – Principles of Biomedical Ethics aimed to identify healthcare’s “common morality”. These are its four principles:

- Respect for autonomy

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

These principles are often in tension with one another, but all healthcare workers and researchers need to factor each into their reflections on what to do in a situation.

Respect for autonomy

Philosophers usually talk about autonomy as a fact of human existence. We are responsible for what we do and ultimately any action we take is the product of our own choice. Recognising this basic freedom at the heart of humanity is a starting point for Beauchamp and Childress.

By itself, the idea human beings are free and in control of themselves isn’t especially interesting. But in a healthcare setting, where patients are often vulnerable and surrounded by experts, it is easy for a patient’s autonomous decision to be disrespected.

Beauchamp and Childress were writing at a time when the expertise of doctors meant they often took extreme measures in doing what they had decided was in the best interests of their patient. They adopted a paternalistic approach, treating their patients like uninformed children rather than autonomous, capable adults. This went as far as performing involuntary sterilisations. In one widely discussed court case in bioethics, Madrigal v Quillian, ten Latina women in the US successfully sued after doctors performed hysterectomies on them without their informed consent.

Legally speaking, the women in Madrigal v Quillian had provided consent. However, Beauchamp and Childress explain clearly why the kind of consent they provided isn’t adequate. The women – who spoke Spanish as a first language – were all being given emergency caesareans. They were asked to sign consent forms written in English which empowered doctors to do what they deemed medically necessary.

In doing so, they weren’t being given the ability to exercise their autonomy. The consent they provided was essentially meaningless.

To address this issue, Beauchamp and Childress encourage us to think about autonomy as creating both ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ duties. The negative duty influences what we must not do: “autonomous actions should not be subject to controlling constraints by others”, they write. But positively, autonomy also requires “respectful treatment in disclosing information” so people can make their own decisions.

Respecting autonomy isn’t just about waiting for someone to give you the OK. It’s about empowering their decision making so you’re confident they’re as free as possible under the circumstances.

Nonmaleficence: ‘first do no harm’

The origins of medical ethics lie in the Hippocratic Oath, which although it includes a lot of different ideas, is often condensed to ‘first do no harm’. This principle, which captures what Beauchamp and Childress mean by non-maleficence, seems sensible on one level and almost impossible to do in practice on another.

Medicine routinely involves doing things most people would consider harmful. Surgeons cut people open, doctors write prescriptions for medicines with a range of side effects, researchers give sick people experimental drugs – the list goes on. If the first thing you did in medicine was to do no harm, it’s hard to see what you might do second.

This is clearly too broad a definition of harm to be useful. Instead, Beauchamp and Childress provide some helpful nuance, suggesting in practice, ‘first do no harm’ means avoiding anything which is unnecessarily or unjustifiably harmful. All medicine has some risk. The relevant question is whether the level of harm is proportionate to the good it might achieve and whether there are other procedures that might achieve the same result without causing as much harm.

Beneficence: do as much good as you can

Some people have suggested Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles are three principles. They suggest beneficence and non-maleficence are two sides of the same coin.

Beneficence refers to acts of kindness, charity and altruism. A beneficent person does more than the bare minimum. In a medical context, this means not only ensuring you don’t treat a patient badly but ensuring you treat them well.

The applications of beneficence in healthcare are wide reaching. On an individual level, beneficence will require doctors to be compassionate, empathetic and sensitive in their ‘bedside manner’. On a larger level, beneficence can determine how a national health system approaches a problem like organ donation – making it an ‘opt out’ instead of ‘opt in’ system.

The principle of beneficence can often clash with the principle of autonomy. If a patient hasn’t consented to a procedure which could be in their best interests, what should a doctor do?

Beauchamp and Childress think autonomy can only be violated in the most extreme circumstances: when there is risk of serious and preventable harm, the benefits of a procedure outweigh the risks and the path of action empowers autonomy as much as possible whilst still administering treatment.

However, given the administration of medical procedures without consent can result in legal charges of assault or battery in Australia, there is clearly still debate around how to best balance these two principles.

Justice: distribute health resources fairly

Healthcare often operates with limited resources. As much as we would like to treat everyone, sometimes there aren’t enough beds, doctors, nurses or medications to go around. Justice is the principle that helps us determine who gets priority in these cases.

However, rather than providing their own theory, Beauchamp and Childress pointed out the various different philosophical theories of justice in circulation. They observe how resources are distributed will depend on which theory of justice a society subscribes to.

For example, a consequentialist approach to justice will distribute resources in the way that generates the best outcomes or most happiness. This might mean leaving an elderly patient with no dependents to die in order to save a parent with young children.

By contrast, they suggest someone like John Rawls would want the access to health resources to be allocated according to principles every person could agree to. This might suggest we allocate resources on the basis of who needs treatment the most, which is the way paramedics and emergency workers think when performing triage.

Beauchamp and Childress’s treatment of justice highlights one of the major criticisms of their work: it isn’t precise enough to help people decide what to do. If somebody wants to work out how to distribute resources, they might not want to be shown several theories to choose between. They want to be given a framework for answering the question. Of course when it comes to life and death decisions, there are no easy answers.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2017

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759—1797) is best known as one of the first female public advocates for women’s rights. Sometimes known as a “proto-feminist”, her significant contributions to feminist thought were written a century before the word “feminism” was coined.

Wollstonecraft was ahead of her time, both intellectually and in the way she lived. Pursuing a writing career was unconventional for women in 18th century England and she was denounced for nearly a century after her death for having a child out of wedlock. But later, during the rise of the women’s movement, her work was rediscovered.

Wollstonecraft wrote many different kinds of texts – including philosophy, a children’s book, a fictional novel, socio-political pamphlets, travel writings, and a history of the French Revolution. Her most famous work is her essay, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Pioneering modern feminism

Wollstonecraft passionately articulated the basic premise of feminism in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – that women should have equal rights to men. Though the essay was published during the French Revolution in 1792, its core argument that women are unjustifiably rendered subordinate to men remains.

Rather than domestic violence, women in senior roles and the gender pay gap, Wollstonecraft took aim at marriage, beauty, and women’s lack of education.

The good wife: docile and pretty

At the core of Wollstonecraft’s critique was the socioeconomic necessity for marriage – “the only way women can rise in the world”. In short, she argued marriage infantilised women and made them miserable.

Wollstonecraft described women as sacrificing respect and character for far less enduring traits that would make them an attractive spouse – such as beauty, docility, and the 18th century notion of sensibility. She argued, “the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement” and they were “so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence”.

Mother of feminism and victim blamer?

Some readers of A Vindication for the Rights of Woman argued Wollstonecraft was only a small step away from victim blaming. She penned plenty of lines positioning women as wilful and active contributors to their own subjugation.

In Wollstonecraft’s eye, expressions of feminine gender were “frivolous pursuits” chosen over admirable qualities that could lift the social standing of her sex and earn women respect, dignity and quality relationships:

“…the civilised women of the present century, with few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.”

While some might find Wollstonecraft was too harsh on the women she wanted to lift, her spear was very much aimed at men, “who considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives”.

Grab it by the patriarchy

Like the word feminism, the word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft. She nevertheless argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

Wollstonecraft commented on men’s “physical superiority” although she did not accept social superiority should follow.

“…not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment.”

Wollstonecraft’s hammering critique against a male dominated society suggested women were forced to be complicit. They had few work options, no property or inheritance rights, and no access to formal education. Without marriage, women were destined to poverty.

What do we want? Education!

Wollstonecraft pointed out all people regardless of sex are born with reason and are capable of learning.

In a time where it was considered racial to insist women were rational beings, Wollstonecraft raised the common societal belief that women lacked the same level of intelligence as men. Women only appeared less intelligent, Wollstonecraft argued, because they were “kept in ignorance”, housebound and denied the formal education afforded to men.

Instead of receiving a useful education, women spent years refining an appealing sexual nature. Wollstonecraft felt “strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty”. Women’s time was poorly invested.

How could women, who were responsible for raising children and maintaining the home, be good mothers, good household managers or good companions to their husbands, if they were denied education? Women’s education, Wollstonecraft contended, would benefit all of society.

Wollstonecraft suggested a free national schooling system where girls and boys were taught together. Mixed sex education, she argued, “would render mankind more virtuous, and happier” – because society and the term mankind itself would no longer exclude girls and women.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture