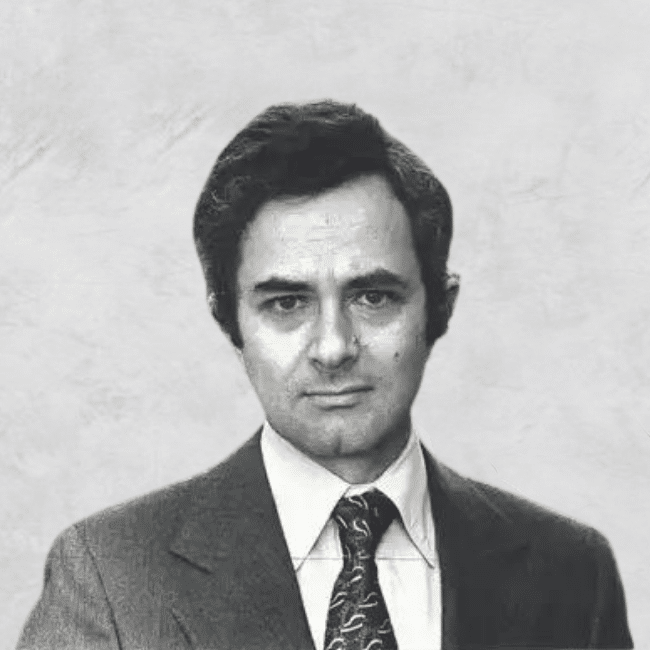

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Thomas Nagel (1937-present) is an American philosopher whose work has spanned ethics, political philosophy, epistemology, metaphysics (the nature of what exists) and, most famously, philosophy of the mind.

An academic philosopher accessible to the general public, an atheist who doubts the materialist theory of evolution – Thomas Nagel is a considered nuanced professor with a rebellious streak.

Born in Belgrade Yugoslavia (present day Serbia) to German Jewish refugees, Nagel grew up in and around New York. Studying first at Cornell University, then the University of Oxford, he completed his PhD at Harvard University under John Rawls, one of the most influential and respected philosophers of the last century. Nagel has taught at New York University for the last four decades.

Subjectivity and Objectivity

A key theme throughout Nagel’s work has been the exploration of the tension between an individual’s subjective view, and how that view exists in an objective world, something he pursues alongside a persistent questioning of mainstream orthodox theories.

Nagel’s most famous work, What Is It Like to Be a Bat? (1974), explores the tension between subjective (personal, internal) and objective (neutral, external) viewpoints by considering human consciousness and arguing the subjective experience cannot be fully explained by the physical aspects of the brain:

“…every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected with a single point of view, and it seems inevitable that an objective, physical theory will abandon that point of view.”

Nagel’s The View From Nowhere (1986) offers both a robust defence and cutting critique of objectivity, in a book described by the Oxford philosopher Mark Kenny as an ideal starting point for the “intelligent novice [to get] an idea of the subject matter of philosophy”. Nagel takes aim at the objective views that assume everything in the universe is reducible to physical elements.

Nagel’s position in Mind and Cosmos (2012) is that non-physical elements, like consciousness, rationality and morality, are fundamental features of the universe and can’t be explained by physical matter. He argues that because (Materialist Neo-) Darwinian theory assumes everything arises from the physical, its theory of nature and life cannot be entirely correct.

The backlash to Mind and Cosmos from those aligned with the scientific establishment was fierce. However, H. Allen Orr, the American evolutionary geneticist, did acknowledge that it is not obvious how consciousness could have originated out of “mere objects” (though he too was largely critical of the book).

And though Nagel is best known for his work in the area of philosophy of the mind, and his exploration of subjective and objective viewpoints, he has made substantial contributions to other domains of philosophy.

Ethics

His first book, The Possibility of Altruism (1970), considered the possibility of objective moral judgments and he has since written on topics such as moral luck, moral dilemmas, war and inequality.

Nagel has analysed the philosophy of taxation, an area largely overlooked by philosophers. The Myth of Ownership (2002), co-written with the Australian philosopher Liam Murphy, questions the prevailing mainstream view that individuals have full property rights over their pre-tax income.

“There is no market without government and no government without taxes … [in] the absence of a legal system [there are] … none of the institutions that make possible the existence of almost all contemporary forms of income and wealth.”

Nagel has a Doctor of Laws (hons.) from Harvard University, has published in various law journals, and in 1987 co-founded with Ronald Dworkin (the famous legal scholar) New York University’s Colloquium in Legal, Political, and Social Philosophy, described as “the hottest thing in town” and “the centerpiece and poster child of the intellectual renaissance at NYU”. The colloquium is still running today.

Alongside his substantial contributions to academic philosophy, Nagel has written numerous book reviews, public interest articles and one of the best introductions to philosophy. In his book what does it all mean?: a very short introduction to philosophy (1987), Nagel leads the reader through various methods of answering fundamental questions like: Can we have free will? What is morality? What is the meaning of life?

The book is less a list of answers, and more an exploration of various approaches, along with the limitations of each. Nagel asks us not to take common ideas and theories for granted, but to critique and analyse them, and develop our own positions. This is an approach Thomas Nagel has taken throughout his career.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Mehhma Malhi 3 DEC 2021

The pandemic has increased the duty we have to other members of our communities.

Different groups of people have different interests, but balancing these interests can cause conflict and friction.

Given Australia’s hard lockdown stance, many people could not wait to lift the restrictions and return to their daily routines. However, in relieving people from these restrictions, we also leave vulnerable populations exposed.

Who do we have a more significant duty towards?

There were discussions around school kids and their right to access education, conversations about teen and adult mental health, and calls to vaccinate the elderly. However, a group that was affected by all these considerations and needed further contemplation was ignored – those with disabilities.

While we are interested in protecting all people, if we do not ensure the safety of the most vulnerable in a population, we fail – we blatantly show that we do not value their needs in conjunction with evaluating a safe society.

The Ethics Centre’s Dr. Simon Longstaff stated recently on Q&A that ‘it is unforgivable that we have to have this conversation … where the most vulnerable members of our community have been left exposed. We should not … expect those people with … vulnerabilities to bear the burden of what we would prefer to do.’

While mental health costs of lockdowns are in favour of opening, Dr. Longstaff warned that ‘we as a society are going to have to accept that those who become infected and die will be something we have to wear on our own conscience.’

Phase 1A of Australia’s vaccine rollout, was initiated in February with the intention of targeting essential healthcare workers and those most vulnerable, such as the elderly and those with disabilities. However, in June only 1 in 5 people with a disability had been vaccinated, and less than 50% of support workers had received both doses of a vaccine. Yet, there was a dramatic increase in October to 70% of individuals being vaccinated.

The marked uptake was likely due to lockdown measures being lifted, as many people wanted the vaccine but could not receive it due to lack of accessibility.

In order to receive a vaccination, people had to contact their GP or later on could book one online.

On the face of it, these distribution procedures seem reasonable but there were significant problems that severely limited access. Having to make a GP appointment simply to obtain a vaccination referral was an unnecessary step that made it particularly difficult for those with disabilities, many of whom are dependent upon others to assist them.

Further, despite being a part of Phase 1A, many people with a disability could not receive the vaccine until lockdown had been lifted and support networks were reinstated. There was no follow-up, reassurance, or support to ensure that those who wanted to receive the vaccine could promptly do so. Therefore, as vaccine distribution moved from one phase to the next, it left an increasing number of those with disabilities behind.

Secondly, for similar reasons, internet access is more difficult for many of those with disabilities and the Department of Health website was not particularly user-friendly. It did not include larger, more legible text or have text to speech which would have helped those with limited sight or those who have trouble reading. Additionally, the high demand for vaccination meant that timeslots were severely limited and if they were available, they were usually inconvenient.

This was especially problematic for those with disabilities because it was not always clear which facilities were equipped with accessible features. To obtain informed consent, centres would need to have staff who are able to understand sign-language and provide information leaflets in braille. Much of this burden of providing additional support and care fell on already stretched family members and carers who, because of lockdown, may already have been working from home and home-schooling children.

What should Australia have done?

First and foremost, the relevant authorities should have ensured that almost 90%+ of each phase was vaccinated before moving to the next phase. In doing so, they would have needed to provide adequate support for those in Phase 1A and set up additional measures as required.

- Vaccine facilities should have been situated close to care facilities.

- Carers and parents should have been able to book their vaccines with individuals.

- Vaccine facilities ought to have implemented “safe” times or locations whereby those with disabilities could show up with no appointment.

What is perhaps irreconcilable is that while these requests/services were prepared during the pandemic, they were simply unavailable due to lack of federal organisation. There are many hospitals around Australia that have rehabilitation medical departments, all of which have specialised members and facilities. Despite notifying the government that they have experience and the equipment to convert into vaccination sites for those living with disabilities, they were not used.

The distribution of the vaccine in Australia was not organised in a manner that was empathetic to individuals living with a disability. I agree with the Royal Commission and Dr Longstaff that ending lockdown and opening without first ensuring high vaccination rates in this vulnerable community was unconscionable and unforgivable.

The lockdown was organised in a manner that did not respect the needs of particular populations. It once again highlights the inequity that people with disabilities face and places the responsibility of any harm to these individuals squarely on society. It was our duty to protect one another from harm during the pandemic, and we have failed a significant group within Australia’s population.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

Big Thinker: David Hume

There are few philosophers whose work has ranged over such vast territory as David Hume (1711—1776).

If you’ve ever felt underappreciated in your time, let the story of David Hume console you: despite being one of the most original and profound thinkers of his or any era, the Scottish philosopher never held an academic post. Indeed, he described his magnum opus, A Treatise of Human Nature, as falling “stillborn from the press.” When he was recognized at all during his lifetime, it was primarily as a historian – his multi-volume work on the history of the British monarchy was heralded in France, while in his native country, he was branded a heretic and a pariah for his atheistic views.

Yet, in the many years since his passing, Hume has been retroactively recognised as one the most important writers of the Early Modern era. His works, which touch on everything from ethics, religion, metaphysics, economics, politics and history, continue to inspire fierce debate and admiration in equal measure. It’s not hard to see why. The years haven’t cooled off the bracing inventiveness of Hume’s writing one bit – he is as frenetic, wide-ranging and profound as he ever was.

Empathy

The foundation of Hume’s ethical system is his emphasis on empathy, sometimes referred to as “fellow-feeling” in his writing. Hume believed that we are constantly being shaped and influenced by those around us, via both an imaginative, perspective-taking form of empathy – putting ourselves in other’s shoes – and a “mechanical” form of empathy, now called emotional contagion.

Ever walked into a room of laughing people and found yourself smiling, even though you don’t know what’s being laughed at? That’s emotional contagion, a means by which we unconsciously pick up on the emotional states of those around us.

Hume emphasised these forms of fellow-feeling as the means by which we navigate our surroundings and make ethical decisions. No individual is disconnected from the world – no one is able to move through life without the emotional states of their friends, lovers, family members and even strangers getting under their skin. So, when we act, it is rarely in a self-interested manner – we are too tied up with others to ever behave in a way that serves only ourselves.

The Nature of the Self

Hume is also known for his controversial views on the self. For Hume, there is no stable, internalised marker of identity – no unchanging “me”. When Hume tried to search inside himself for the steady and constant “David Hume” he had heard so much about, he found only sensations – the feeling of being too hot, of being hungry. The sense of self that others seemed so certain of seemed utterly artificial to him, a tool of mental processing that could just as easily be dispatched.

Hume was no fool – he knew that agents have “character traits” and often behave in dependable ways. We all have that funny friend who reliably cracks a joke, the morose friend who sees the worst in everything. But Hume didn’t think that these character traits were evidence of stable identities. He considered them more like trends, habits towards certain behaviours formed over the course of a lifetime.

Such a view had profound impacts on Hume’s ethics, and fell in line with his arguments concerning empathy. After all, if there is no self – if the line between you and I is much blurrier than either of us initially imagined – then what could be seen as selfish behaviours actually become selfless ones. Doing something for you also means doing something for me, and vice versa.

On Hume’s view, we are much less autonomous, sure, forever buffeted around by a world of agents whose emotional states we can’t help but catch, no sense of stable identity to fall back on. But we’re also closer to others; more tied up in a complex social web of relationships, changing every day.

Moral Motivation

Prior to Hume, the most common picture of moral motivation – one initially drawn by Plato – was of rationality as a carriage driver, whipping and controlling the horses of desire. According to this picture, we act after we decide what is logical, and our desires then fall into place – we think through our problems, rather than feeling through them.

Hume, by contrast, argued that the inverse was true. In his ethical system, it is desire that drives the carriage, and logic is its servant. We are only ever motivated by these irrational appetites, Hume tells us – we are victims of our wants, not of our mind at its most rational.

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

At the time, this was seen as a shocking inversion. But much of modern psychology bears Hume out. Consider the work of Sigmund Freud, who understood human behaviour as guided by a roiling and uncontrollable id. Or consider the situation where you know the “right” thing to do, but act in a way inconsistent with that rational belief – hating a successful friend and acting to sabotage them, even when on some level you understand that jealousy is ugly.

There are some who might find Hume’s ethics somewhat depressing. After all, it is not pleasant to imagine yourself as little more than a constantly changing series of emotions, many of which you catch from others – and often without even wanting to. But there is great beauty to be found in his ethical system too. Hume believed he lived in a world in which human beings are not isolated, but deeply bound up with each other, driven by their desires and acting in ways that profoundly affect even total strangers.

Given we are so often told our world is only growing more disconnected, belief in the possibility to shape those around you – and therefore the world – has a certain beauty all of its own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Big thinker

Relationships

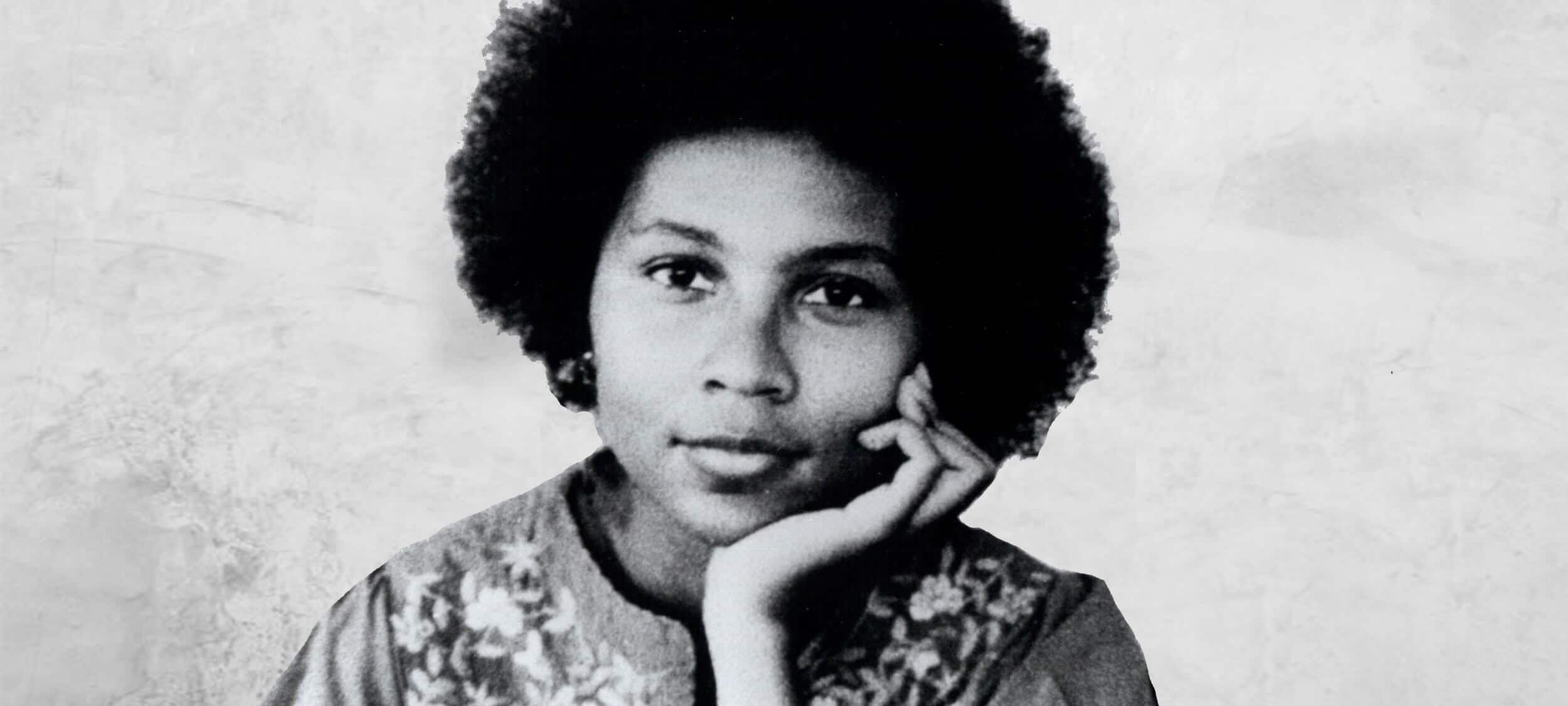

Big Thinker: bell hooks

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The self and the other: Squid Game's ultimate choice

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 25 NOV 2021

In the world of Netflix’s smash hit Squid Game, a collection of desperate people must make a terrible choice: they can either keep living their lives, which are filled with debt and suffering, or they can submit to the titular competition, a series of contests based on children’s games. If they win these contests, their debts will be absolved. If they lose, they will die.

*Spoiler warning for Squid Game

The Australian philosopher Peter Singer would call this an “ultimate choice.” Although on the surface, it is a decision as to whether or not to live with debt, in a much deeper sense, it’s a decision about how to live. The very foundational beliefs of Squid Game’s frantic characters are being challenged. What matters to these people? What do they want out of life? And, just as importantly, how far will they go to get it?

The State of Nature

Squid Game depicts a world of pure barbarism: guided by their desperation, its characters form alliances only when it is mutually beneficial to them, and are often as quick to betray one another. In episode three, for instance, Sang-woo uses insider knowledge of the next contest to get himself ahead, concealing from his supposed allies that he is already aware of what is about to occur.

True acts of kindness sometimes flash through like fish glimpsed at the bottom of a river – consider Hwang Jun-ho, whose participation in the world of Squid Game is guided by the love of his brother – but such moments of empathy are few and far between.

The depiction of such a blood-thirsty, self-interested world is one the philosopher Thomas Hobbes played upon in his construction of the “state of nature.” According to Hobbes, human beings who exist in this state live in a way that is “nasty, brutish, and short.” In such a primal state, one without government, there is no centralised means of understanding or enforcing what is right and wrong, and self-interest is the name of the game.

“So long a man is in the condition of mere nature, (which is a condition of war,)” Hobbes wrote, “private appetite is the measure of good and evil.”

Hobbes believed that the only way to avoid this state of nature was to submit to a governing force – to hand oneself over to a power that could create and enforce a set of rules, known as the social contract. The world of Squid Game contains such a governing force, the shadowy world of the VIPs, who run the games for their own amusement.

But rather than guiding the games’ participants out of the state of nature, the VIPs further deepen and enforce it. The rules that they develop are explicitly designed to keep the desperate players in a world of confusion and barbarism, where self-interest is rewarded, and chaos is the name of the game. The lives of the participants are nasty, brutish, and short, and their spurning of ethics in favour of desperate attempts to get ahead is actively rewarded by a system that runs, above all else, on violence.

The suspension of the moral code

This system, vicious as it is, pushes ordinary people to extraordinary lengths. The characters of Squid Game are, for the most part, simply and vividly drawn – they are defined above all else by their desire to absolve their debts and live freely. That one desire is all it takes for them to suspend the usual moral code that most of us live by, and to act in frequently horrific ways.

Even Sang-Woo, one of the more honorable characters in the show, ends up making deeply immoral choices, culminating in his decision to hurl the glassmaker off a platform in a final act of desperation. He has no stable set of ethics – his code is shaped by a system that thrives on horror and pushes human beings to consider their fellow brethren as little more than tools to be used and discarded at whim.

In this way, Squid Game offers a gleefully cruel riposte to the notion of virtue ethics. Its characters do not act in consistent, moral ways, as virtue ethics imagines that agents do. Although it takes a combination of financial ruin and a system deliberately designed to sow mistrust and horror for them to abandon their usual moral principles, it still brings up some uncomfortable questions about how easily we might abandon our ethics in the real world.

With a kind of horrifying elegance, the show also reveals just how fragile our notion of solidarity can be. We might want to believe that there are bonds between ourselves and even total strangers that cannot be broken – a kind of communal well-spring of trust that stops abject violence from breaking out. But dangle the mere proposition of a debt-free life in front of people willing to do anything to save themselves and their families, and this sense of community breaks horribly down. The show’s participants are alienated not only from their own moral code, but from each other. They are strangers in the deepest sense of the term, the simple, child-like games of the show’s title obliterating any sense of shared humanity.

But can these participants be blamed for their actions? Derek Parfit, the English philosopher, would argue not. It was he who developed the notion of “blameless immorality”, conditions under which people can be forced into vicious actions for which they are not culpable. The heroes of Squid Game are propping up a system that perpetuates further horror, certainly, but their autonomy has been radically diminished. They are little more than puppets, guided by powers outside of their control, their actions no longer their own.

Ethics Versus Self-Interest: The False Choice

Squid Game rests on the principle that self-interest and ethics are at loggerheads with one another – that choosing to do good for others leads necessarily to a sacrifice for oneself. Yet, it’s worth analysing this supposed dichotomy between self-interest and a good, ethical life.

Certainly, the notion that helping others requires us to sacrifice something for ourselves is an old, pervasive myth – it’s why we can view do-gooders as suckers, wasting time on the help of others instead of getting ahead. As Singer notes, such a view was particularly prevalent in the ‘80s with the rise of Wall Street, a world where duping the market – and even your supposed friends – had considerable benefits.

Act immorally – lie, cheat and steal – and you too could become a power player, with more wealth than you dreamed of.

But is there really such a distinction between being self-interested and acting ethically? Could it not be that this is merely an old capitalist myth, designed to perpetuate a system that thrives on “othering” and isolation? After all, viewing our interests as separate from those around us requires us to believe that we are sealed off from the social world, that there is some kind of line to be drawn between behaviours that are meaningfully “ours” and those that belong to others.

In actual fact, it is worth moving away from such an individualist notion of the self, and towards a more communal one. As it happens, the characters of Squid Game are actively hurt by the ways that they are forced to view themselves as alienated from their fellow competitors. It benefits only the show’s mysterious villains, explicitly capitalist and murderous sociopaths, for the heroes of Squid Game to believe in the line between what will help them, and what will help their friends. When, in the penultimate episode, Gi-hun suggests to Sae-byeok that they team up against Sang-Woo, Gi-hun makes the fatal mistake of believing that she has anything to gain through Sang-Woo’s misfortunes.

Such a move away from individuation is not easy. Indeed, Squid Game has a breathtaking nihilism to it –there is no easy way for the characters to escape this deep alienation from one another. The system does not permit it. In the words of Audre Lorde:

“…the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

As philosopher Mark Fisher once wrote in his explication of capitalist realism (the notion that capitalism has pervaded every aspect of human life and is now essentially inescapable), even the ways in which Squid Game’s doomed characters attempt to overthrow their bonds are subsumed as part of those very bonds themselves.

Just as anti-capitalism becomes tainted by capitalism, the means of overthrowing the system sold as one more product, the characters of Squid Game have no recourse by which to escape the individuation that they are fatally trapped in. Their very attempts to connect with one another are undermined by the rules of each game, like the marble game, where voluntarily made pairs are then forced to kill each other.

Squid Game is thus a word of warning. In its terror and violence, it is a reminder to always strive for community, away from individuation and towards a system in which we see fellow agents as more alike us than not. Hope might not be possible for the show’s protagonists, whose very rebellion is neutered at every turn. But, if we resist the moral alienation and deep individuation thrust upon us by capitalism, it might be possible for us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2021

Autonomy is the capacity to form beliefs and desires that are authentic and in our best interests, and then act on them.

What is it that makes a person autonomous? Intuitively, it feels like a person with a gun held to their head is likely to have less autonomy than a person enjoying a meandering walk, peacefully making a choice between the coastal track or the inland trail. But what exactly are the conditions which determine someone’s autonomy?

Is autonomy just a measure of how free a person is to make choices? How might a person’s upbringing influence their autonomy, and their subsequent capacity to act freely? Exploring the concept of autonomy can help us better understand the decisions people make, especially those we might disagree with.

The definition debate

Autonomy, broadly speaking, refers to a person’s capacity to adequately self-govern their beliefs and actions. All people are in some way influenced by powers outside of themselves, through laws, their upbringing, and other influences. Philosophers aim to distinguish the degree to which various conditions impact our understanding of someone’s autonomy.

There remain many competing theories of autonomy.

These debates are relevant to a whole host of important social concerns that hinge on someone’s independent decision-making capability. This often results in people using autonomy as a means of justifying or rebuking particular behaviours. For example, “Her boss made her do it, so I don’t blame her” and “She is capable of leaving her boyfriend, so it’s her decision to keep suffering the abuse” are both statements that indirectly assess the autonomy of the subject in question.

In the first case, an employee is deemed to lack the autonomy to do otherwise and is therefore taken to not be blameworthy. In the latter case, the opposite conclusion is reached. In both, an assessment of the subject’s relative autonomy determines how their actions are evaluated by an onlooker.

Autonomy often appears to be synonymous with freedom, but the two concepts come apart in important ways.

Autonomy and freedom

There are numerous accounts of both concepts, so in some cases there is overlap, but for the most part autonomy and freedom can be distinguished.

Freedom tends to broader and more overt. It usually speaks to constraints on our ability to act on our desires. This is sometimes also referred to as negative freedom. Autonomy speaks to the independence and authenticity of the desires themselves, which directly inform the acts that we choose to take. This is has lots in common with positive freedom.

For example, we can imagine a person who has the freedom to vote for any party in an election, but was raised and surrounded solely by passionate social conservatives. As a member of a liberal democracy, they have the freedom to vote differently from the rest of their family and friends, but they have never felt comfortable researching other political viewpoints, and greatly fear social rejection.

If autonomy is the capacity a person has to self-govern their beliefs and decisions, this voter’s capacity to self-govern would be considered limited or undermined (to some degree) by social, cultural and psychological factors.

Relational theories of autonomy focus on the ways we relate to others and how they can affect our self-conceptions and ability to deliberate and reason independently.

Relational theories of autonomy were originally proposed by feminist philosophers, aiming to provide a less individualistic way of thinking about autonomy. In the above case, the voter is taken to lack autonomy due to their limited exposure to differing perspectives and fear of ostracism. In other words, the way they relate to people around them has limited their capacity to reflect on their own beliefs, values and principles.

One relational approach to autonomy focuses on this capacity for internal reflection. This approach is part of what is known as the ‘procedural theory of relational autonomy’. If the woman in the abusive relationship is capable of critical reflection, she is thought to be autonomous regardless of her decision.

However, competing theories of autonomy argue that this capacity isn’t enough. These theories say that there are a range of external factors that can shape, warp and limit our decision-making abilities, and failing to take these into account is failing to fully grasp autonomy. These factors can include things like upbringing, indoctrination, lack of diverse experiences, poor mental health, addiction, etc., which all affect the independence of our desires in various ways.

Critics of this view might argue that a conception of autonomy is that is broad makes it difficult to determine whether a person is blameworthy or culpable for their actions, as no individual remains untouched by social and cultural influences. Given this, some philosophers reject the idea that we need to determine the particular conditions which render a person’s actions truly ‘their own’.

Maybe autonomy is best thought of as merely one important part of a larger picture. Establishing a more comprehensively equitable society could lessen the pressure on debates around what is required for autonomous action. Doing so might allow for a broadening of the debate, focusing instead on whether particular choices are compatible with the maintenance of desirable societies, rather than tirelessly examining whether or not the choices a person makes are wholly their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 19 NOV 2021

You’re at your desk when a complaint comes in about a comment by a senior employee on their social media account.

The post had nothing to do with their job, yet the complainant was able to track the person down at work – helped by the fact the same photo appeared on both the employee’s personal account and your company’s website.

What should you do? How do you reconcile the employee’s right to express their personal views with the need to protect your organisation’s good name?

At a recent gathering of The Ethics Alliance, members agreed that such dilemmas are increasingly common.

It’s a complex and rapidly shifting environment. Organisations are or are expected to be driven by purpose, one which considers society as a whole in its pursuit of success and can lose community trust if they fail to satisfy their multiple stakeholders. In parallel employers encourage diversity and inclusion, while asking staff to be authentic and “bring your whole self to work”. Tensions will inevitably arise.

In today’s organisations, people need to do more than just comply with rules – they are often required to make judgment calls. This became more formalised in the early 2000s when codes of conduct started being replaced by codes of ethics.

This stems partly because of the rapid rate of change in business: products and services can be replicated so quickly that companies are known not so much for what they make, but for what they “mean” and how they behave.

So what happens when differing values between individual and organisational values play out through social media?

One key insight shared at the Ethics Alliance gathering is that both risk and responsibility are greater for people who are more senior in the hierarchy. There was a consensus that clear policies are crucial, but that there is no one-size-fits-all solution, incidents need to be seen through multiple lenses and considered on a case-by-case basis.

For example, an organisation has an obligation to protect staff who speak out on its behalf from trolling, and to recognise that just as corporate values evolve, so too do the personal values of individuals. And if a complaint is judged to be trivial or mischievous, a representative might offer an apology on behalf of the organisation but not even inform the person targeted, because that would be neither necessary nor helpful. In such a grey area, flexibility is vital.

Law firm Gilbert + Tobin’s social media policy prohibits posts that are illegal, are derogatory of G+T, its employees or clients, or constitute serious misconduct such as disclosure of confidential information. As well, staff must not publish or post material that may reasonably be considered offensive, obscene, defamatory, threatening, harassing, bullying, discriminatory, hateful, racist, sexist or homophobic.

The policy has flexibility built in. Anna Sparkes, Chief People Officer says that if a post could be associated with Gilbert + Tobin, the poster must add a disclaimer stating that their views do not represent those of the firm. And if a complaint were received, the outcome would depend on the actions, whether the individual could be identified as being an employee, and whether there was a direct breach of the social media policy.

For property investment fund Charter Hall, if a senior executive has views that do not accord with major tenants or investors, there is the potential to affect the business. This is true of many organisations.

Charter Hall’s Head of People Emma Stewart says: “If I sign a contract that says, I’m signing up for this, knowing that I’m agreeing to not bring the brand and reputation of the organization into disrepute, then unfortunately or fortunately I’ve got to accept that that may come with some compromises, and I’ve got to be okay with that if I’m prepared to continue the employment arrangement.”

Organisations also need to be aware that if the compromise is too great within the workplace, the employee may be at risk of “moral injury”. Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay, the foundational voice on the subject, describes it as “the soul wound inflicted by doing something that violates one’s own ethics, ideals, or attachments”.

In such a case, both the organisation and the individual may need to decide whether the relationship is tenable. For the employee, prolonged pressure to act in ways that feel inauthentic and not aligned with personal values may also affect their ability to perform well in other aspects of their job. For both psychological safety and practical reasons, it may be better to part ways.

Tim Costello, the Director of Ethical Voice and former CEO of World Vision Australia, shares these concerns about “the interdependence and the extraordinary shared vulnerability between a corporate reputation and an employee’s own convictions”.

“You’re so entwined. It’s got really tricky in my own mind now,” he said.

Tim also feels the online world has hampered his ability to tailor a speech to a particular audience. “It has profoundly limited free speech.”

And he laments the loss of “that private area where you work out where you’re at, rock on rock, stone on stone, sharpen and revise”.

“I’m an extrovert, I process things aloud,” he said. “Anything can be tweeted in real time while you’re talking, before you’ve even finished your point.”

Ideas about social media and the public expression of values are being put to the test with a federal government bill suggesting changes to governance standard three in the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Regulation 2013 to expand the scope of impermissible activities that registered charities must not engage in or promote others to engage in.

Consequences are that charities will be stripped of their Deductible Gift Recipient status if an employee or volunteer commits a minor offence.

For example, a charity could lose DGR status if a staffer put up a social media post in support of a rally that turned violent, or if a volunteer put stickers on private property.

While it is widely understood that the proposed law is aimed at environmental groups, Tim Costello says the bill is “legislative over-reach” that would stifle all organisations’ ability to do advocacy.

Certainly, such a law would impose a “one size fits all” approach to a varied sector and a huge range of behaviours when multiple lenses are vital.

For organisations navigating these waters, it is essential first to clarify what they stand for and then to communicate these values to all stakeholders, particularly employees. When it comes to resolving problems, policies on social media and other out-of-work-hours behaviour provide a strong foundation, but complex situations require a flexible approach. Today’s solutions may need to be adapted to work in the evolving world tomorrow.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Five subversive philosophers throughout the ages

Philosophy helps us bring important questions, ideas and beliefs to the table and work towards understanding. It encourages us to engage in examination and to think critically about the world.

Here are five philosophers from various time periods and walks of life that demonstrate the importance and impact of critical thinking throughout history.

Ruha Benjamin

Ruha Benjamin (1978–present), while not a self-professed philosopher, uses her expertise in sociology to question and criticise the relationship between innovation and equity. Benjamin’s works focus on the intersection of race, justice and technology, highlighting the ways that discrimination is embedded in technology, meaning that technological progress often heightens racial inequalities instead of addressing them. One of the most prominent of these is her analysis of how “neutral” algorithms can replicate or worsen racial bias because they are shaped by their creators’ (often unconscious) biases.

“The default setting of innovation is inequity.”

J. J. C. Smart

J.J.C. Smart (1920-2012) was a British-Australian philosopher with far-reaching interests across numerous subfields of philosophy. Smart was a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities at its establishment in 1969. In 1990, he was awarded the Companion in the General Division of the Order of Australia. In ethics, Smart defended “extreme” act utilitarianism – a type of consequentialism – and outwardly opposed rule utilitarianism, dubbing it “superstitious rule workshop”, contributing to its steadily decline in popularity.

“That anything should exist at all does seem to me a matter for the deepest awe. But whether other people feel this sort of awe, and whether they or I ought to, is another question. I think we ought to.”

Elisabeth of the Bohemia

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618–1680) was a philosopher who is best known for her correspondence with René Descartes. After meeting him while he was visiting in Holland, the two exchanged letters for several years. In the letters, Elisabeth questions Descartes’ early account of mind-body dualism (the idea that the mind can exist outside of the body), wondering how something immaterial can have any effect on the body. Her discussion with Descartes has been cited as the first argument for physicalism. In later letters, her criticisms prompted him to develop his moral philosophy – specifically his account of virtue. Elisabeth has featured as a key subject in feminist history of philosophy, as she was at once a brilliant and critical thinker, while also having to live with the limitations imposed on women at the time.

“Inform your intellect, and follow the good it acquaints you with.”

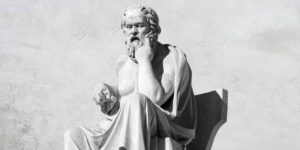

Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE–399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy, though almost all we know of him is derived from the work of others, like Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes. Socrates is known for bringing about a huge shift in philosophy away from physics and toward practical ethics – thinking about how we do live and how we should live in the world. Socrates is also known for bringing these issues to the public. Ultimately, his public encouragement of questioning and challenging the status quo is what got him killed. Luckily, his insights were taken down, taught and developed for centuries to come.

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

Francesca Minerva

Francesca Minerva is a contemporary bioethicist whose work includes medical ethics, technological ethics, discrimination and academic freedom. One of Minerva’s most controversial (if misunderstood) contributions to ethics is her paper, co-written with Alberto Giubilini in 2012, titled “After-birth Abortion: why should the baby live?”. In it, the pair argue that if it’s permissible to abort a foetus for a reason, then it should also be permissible to “abort” (i.e., euthanise) a newborn for the same reason. Minerva is also a large proponent of academic freedom and co-founded the Journal of Controversial Ideas in an effort to eliminate the social pressures that threaten to impede academic progress.

“The proper task of an academic is to strive to be free and unbiased, and we must eliminate pressures that impede this.”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 11 NOV 2021

The scenario is familiar to us all. Company X is in crisis. A series of poor management decisions set in motion a sequence of events that lead to an avalanche of bad headlines and public outcry.

When things go wrong for an organisation – so wrong that the carelessness or misdeeds revealed could be considered ethical failure – responsibility is shouldered by those who are the final decision makers. They are and should be held accountable.

Boards of organisations, and the individual directors that comprise them, collectively make decisions about strategy, governance and corporate performance. Decisions that involve the interests of shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and the wider community. They will also involve competing values, compromises and tradeoffs, information gaps and grey areas.

In the recent 2021 Future of the Board report from The Governance Institute of Australia, respondents were surveyed to consider the most valued attributes for future board directors. Strategic and critical thinking were once again ranked the highest, closely followed by the values of ethics and culture as the two most important areas that boards need to focus on to prevent corporate failure. A culture of accountability, transparency, trust and respect were viewed as a top factor determining a healthy dynamic between boards and management.

Ethics plays a central role in the decisions that face Boards and directors, such as:

- What constitutes a conflict of interest and how should it be managed?

- How aggressive should tax strategies be?

- What incentive structures and sales techniques will create a healthy and ethical organisational culture?

- What about investments in organisations that profit from arms and weaponry?

- How should organisations manage the effects technology has on their workforce?

- What obligation do organisations have to protect the environment and human rights?

Together, The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) and The Ethics Centre have developed a decision-making guide for directors.

Ethics in the Boardroom provides directors with a simple decision-making framework which they can use to navigate the ethical dimensions of any decision. Through the insights of directors, academics and subject matter experts, the guide also provides four lenses to frame board conversations. These lenses give directors the best chance of viewing decisions from different perspectives. Rather than talking past each other, they will help directors pinpoint and resolve disagreement.

- Lens 1: General influences – Organisations are participants in society through the products and services they offer and their statuses as employers and influencers. The guide invites directors to seek out the broadest possible range of perspectives to enhance their choices and decisions. It also suggests that organisations should strive for leadership. What do you think about companies that take a stance on matters like climate change and same sex marriage?

- Lens 2: The board’s collective culture and character – In ethical decision making, directors are bound to apply the values and principles of their organisation. As custodians, they must ensure that culture and values are aligned. The guide invites directors to be aware that ethical decision-making in the boardroom must be tempered. Decision making shouldn’t be driven by: form over substance, passion over reason, collegiality over concurrence, the need to be right, or legacy. Just because a particular course of action is legal, does that make it right? Just because a company has always done it that way, should they continue?

- Lens 3: Interpersonal relationships and reasoning – Boards are collections of individuals who bring their own individual decision-making ‘style’ to the board table. Power dynamics exist in any group, with each person influencing and being influenced by others. Making room for diversity and constructive disagreement is vital. How can chairs and other directors empower every director to stand up for what is right? How do boards ensure that the person sitting quietly, with deep insights into ethical risk, has the courage to speak?

- Lens 4: The individual director – Directors bring their own wisdom and values to decision making. But they also might bring their own motivations that biases. The guide invites directors to self-reflect and bring the best of themselves to the board table. How can we all be more reflective in our own decision making?

This guide is a must-read for anyone who has an interest in the conduct of any board-led organisation. That includes schools, sports clubs, charities and family businesses as well as large corporations.

Behind each brand and each company, there are people making decisions that affect you as a consumer, employee and citizen. Wouldn’t you rather that those at the top had ethics at the front of their mind in the decisions that they make?

Click here to view or download a copy of the guide.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Perils of an unforgiving workplace

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Lying is something we’ve all done at some point and we tend to take its meaning for granted, but what are we really doing when we lie, and is it ever okay?

A person lies when they:

- knowingly communicate something false

- purposely communicate it as if it was true

- do so with an intention to deceive.

The intention to deceive is an essential component of lying. Take a comedian, for example – they might intentionally present a made-up story as true when telling a joke, engaging in satire, etc. However, the comedian’s purpose is not to deceive but to entertain.

Lying should be distinguished from other deviations from the truth like:

- Falsehoods – false claims we make while believing what we say to be true

- Equivocations – the use of ambiguous language that allows a person to persist in holding a false belief.

While these are different to lying, they can be equally problematic. Accidentally communicating false information can still result in disastrous consequences. People in positions of power (e.g., government ministers) have an obligation to inform themselves about matters under their control or influence and to minimise the spread of falsehoods. Having a disregard for accuracy, while it is not lying, should be considered wrong – especially when as a result of negligence or indifference.

The same can be said of equivocation. The intention is still there, but the quality of exchange is different. Some might argue that purposeful equivocation is akin to “lying by omission”, where you don’t actively tell a lie, but instead simply choose not to correct someone else’s misunderstanding.

Despite lying being fairly common, most of our lives are structured around the belief that people typically don’t do it.

We believe our friends when we ask them the time, we believe meteorologists when they tell us the weather, we believe what doctors say about our health. There are exceptions, of course, but for the most part we assume people aren’t lying. If we didn’t, we’d spend half our days trying to verify what everyone says!

In some cases, our assumption of honesty is especially important. Democracies, for example, only function legitimately when the government has the consent of its citizens. This consent needs to be:

- free (not coerced)

- prior (given before the event needing consent)

- informed (based on true and accessible information)

Crucially, informed consent can’t be given if politicians lie in any aspects of their governance.

So, when is lying okay? Can it be justified?

Some philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant, argue that lying is always wrong – regardless of the consequences. Kant’s position rests on something called the “categorical imperative”, which views lying as immoral because:

- it would be fundamentally contradictory (and therefore irrational) to make a general rule that allows lying because it would cause the concepts of lies and truths to lose their meaning

- it treats people as a means rather than as autonomous beings with their own ends

In contrast, consequentialists are less concerned with universal obligations. Instead, their foundation for moral judgement rests on consequences that flow from different acts or rules. If a lie will cause good outcomes overall, then (broadly speaking) a consequentialist would think it was justified.

There are other things we might want to consider by themselves, outside the confines of a moral framework. For example, we might think that sometimes people aren’t entitled to the truth in principle. For example, during a war, most people would intuit that the enemy isn’t entitled to the truth about plans and deployment details, etc. This leads to a more general question: in what circumstances do people forfeit their right to the truth?

What about “white lies”? These lies usually benefit others (sometimes at the liar’s expense!) or are about trivial things. They’re usually socially acceptable or at least tolerated because they have harmless or even positive consequences. For example, telling someone their food is delicious (even though it’s not) because you know they’ve had a long day and wouldn’t want to hurt their feelings.

Here are some things to ask yourself if you’re about to tell a white lie:

- Is there a better response that is truthful?

- Does the person have a legitimate right to receive an honest answer?

- What is at stake if you give a false or misleading answer? Will the person assume you’re telling the truth and potentially harm themselves as a result of your lie? Will you be at fault?

- Is trust at the foundation of the relationship – and will it be damaged or broken if the white lie is found out?

- Is there a way to communicate the truth while minimising the hurt that might be caused? For example, does the best response to a question about an embarrassing haircut begin with a smile and a hug before the potentially hurtful response?

Lying is a more complex phenomenon than most people consider. Essentially, our general moral aversion to it comes down to its ability to inhibit or destroy communication and cooperation – requirements for human flourishing. Whether you care about duties, consequences or something else, it’s always worth questioning your intentions to check if you are following your moral compass.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

Partway through the New Yorker’s profile of leading philosopher David Benatar, there is an anecdote that sums up his ethical position neatly.

A colleague at Benatar’s university announces to the department that she is pregnant. Benatar is pushed by the colleague as to whether he is happy about the news. Benatar thinks, then replies: “I am happy,” he says. “For you.”

Benatar is a leading advocate for the philosophical school known as anti-natalism. For such thinkers, being born is a harm. As it is so cleanly put in the title of his best-known work, Benatar believes that for each of us, it would have been better for us to never have been – non-existence is preferable to existence. Benatar might be happy for his colleague, but he is not happy for the conceived child who now faces a future of pain, distress and fear.

For such a seemingly pessimistic outlook, Benatar’s arguments in favour of anti-natalism are shockingly elegant. Take, for instance, his foundational view: the asymmetry of pleasure and pain. According to Benatar, pain is bad; pleasure is good. An absence of pain is good. But an absence of pleasure is not bad for the person for whom that absence is not a deprivation.

Imagine, for instance, that one day, on a morning stroll, you encounter a branching path. You take the left road. A few metres ahead, you spot a $100 bill lying on the ground. This brings you a deep pleasure. But now let’s say that you never took the left road – that you instead veered right. In this possible world, you do not encounter the $100 bill. If you had taken the left path, you would have. But you don’t know that. You have not been promised any money; you are not aware of what you have lost. Thus, Benatar thinks, you have not been harmed.

This is the key to the anti-natalist position. The child who is never born does not know that they are missing out on the pleasures of life; there is no entity who has been deprived, because there is no entity that exists. Moreover, the child who is born might encounter these pleasures, but they will also encounter a great number of pains. For Benatar, life is a myriad of tiny, complicated discomforts, from being hungry to needing the bathroom. Not bringing a child into the world means avoiding the perpetuation of suffering, saving an entity from a long, painful life for which the only escape – suicide, death, illness – is more pain.

These views may sound, for some, deeply psychologically distressing, and Benatar acknowledges that these are not easy pills to swallow. But he believes that they are necessary truths; that they are, in a sense, inevitable conclusions to be drawn from the nature of being a conscious entity in the world.

“I think that there is something hopeless and psychologically distressing about the nature of sentient life that makes anti-natalism the correct position to hold,” he explains.

Benatar’s position has been criticised by a number of thinkers, most recently by the stoic philosopher Massimo Pigliucci, who argued against the asymmetry of pleasure and pain in a recent blog post. According to Pigliucci, pain need not be morally bad; pleasure need not be morally good. For the stoic, these are “indifferents”, their moral value neutral.

But Benatar believes that Pigliuicci has misattributed claims to him. “The asymmetry I describe is not itself a moral claim – even though it supports moral claims about the ethics of procreation,” he explains. “My claims about pain and pleasure are claims about their prudential value for the person whose pain and pleasure they are – or would be.”

“Anybody – and I am not suggesting that Professor Pigliucci is among them – who denies that pain is intrinsically bad for the person whose pain it is, and that pleasure is intrinsically good for the person whose pleasure it is, does not understand what pain and pleasure are, and how and why they arose evolutionarily. If pain does not feel bad, it is not pain. If pleasure does not feel good, it is not pleasure.”

Others still have compared Benatar’s positions to those held by ecofascists, thinkers who believe that humanity is a virus that is wreaking a havoc on the natural world, and that the only way to avoid this suffering is to force the extinction of the human race. Indeed, there is at least some overlap between ecofascist beliefs and anti-natalist ones – both argue in favour of the end of human life – but Benatar is untroubled by such a connection, for the same reason that “those of us opposed to smoking should not be troubled that the Nazis were also opposed to smoking.”

“Even though (some) anti-natalists think that humans are bad for the environment, this shows only that they agree with the ‘eco’ part of ‘ecofascism’,” Benatar explains. “Anti-natalists are not committed to the ‘fascism’ part – and should, I argue, be opposed to it.”

Benatar’s position might seem deeply cynical, even nihilistic, but there is a strange kind of hope in it too. “Part of the reason why some people may find anti-natalism unthinkable is that they cannot correctly imagine what a world without sentient life would be like,” he explains. For the anti-natalist, there is some comfort to be taken in this potential, consciousness-free world – a world without suffering, without pain, without suicide or famine or death. After all, what, paradoxically, is more optimistic than that?

David Benatar presents The Case for Not Having Children at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

Image by Aarón Blanco Tejedor

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships