Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 30 JUL 2025

Sometimes good people do bad things. It’s important to understand why so we can respond ethically.

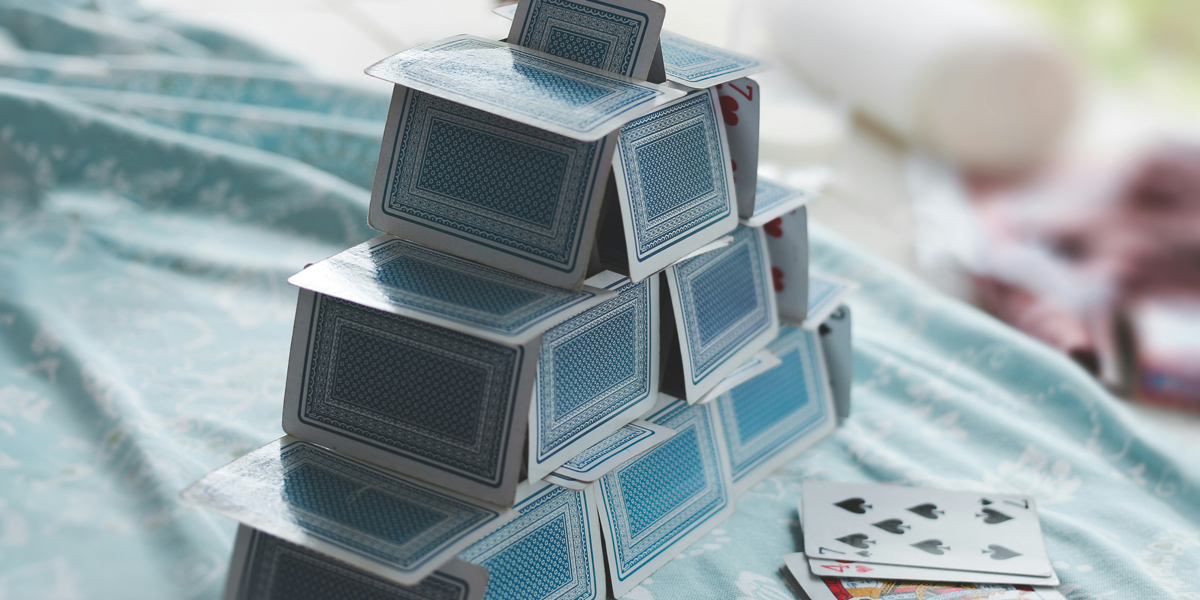

The news is filled with stories of everyday people doing bad things. A small business owner might underpay workers, a senior manager in a corporation could be cutting corners to improve profit margins, or a protester damages a precious artwork to promote their cause.

It’s natural to feel outrage when we hear about incidents like this. We might condemn the perpetrator and want to see them punished. But not every wrongdoer is a moustache twirling villain. Often, they’re otherwise good people who are perfectly ethical in other aspects of their lives. This makes their bad behaviour especially puzzling.

If we don’t understand what motivates their behaviour, then we risk responding in a way that won’t fix the problem, or might even make things worse. Here are four different reasons why good people do bad things and some ways to prevent or correct them.

1. Weakness of will

Temptation is everywhere. Sometimes we know something is wrong, but we are tempted to do it anyway because we know doing so will benefit us. The small business owner might be tempted to increase their profits by paying their staff below minimum wage. Or your neighbour could be tempted to poison a beautiful old tree that is protected by council because it’s blocking their view.

When we’re faced with temptation, and if we think we can get away with it, it takes willpower to stop us from doing the wrong thing. Yet, all too often, willpower is insufficient to stop us. This weakness of will, called “akrasia” by Aristotle, is one of the main causes of unethical behaviour.

There are two dimensions to weakness of will: the first is desire, which sits in tension with willpower. As such, one way to prevent weakness of will is to cultivate the virtue of self-control. However, it may not be prudent to rely on self-control entirely, given that it’s an all-too finite resource for many of us.

So, the other approach is to reduce temptation. That could mean removing the source of the temptation from our presence, like hiding the chocolate cookies in the cupboard rather than leaving them out on the kitchen table. It can also mean increasing accountability, such as through transparency and oversight. We’re less likely to be tempted to do something wrong if we feel we’re unlikely to get away with it.

2. Moral blindness

All too often, people simply don’t see that what they’re doing is wrong. Like the banker who is so focused on earning a commission that they turn a blind eye to money laundering. Or the manager who doesn’t realise that they keep unfairly promoting staff who have a similar ethnicity to them.

This is moral blindness. Sometimes it might be excusable, like if they had no way of knowing that they were causing harm. But, ignorance is not always an excuse. We must all be mindful of how our actions affect others, and we can’t avoid responsibility if we could have reasonably anticipated that our actions were unethical.

There’s also the problem of wilful obliviousness, which is where we avoid thinking too hard about what we’re doing because, deep down, we know it could be wrong. It’s like refusing to watch an exposé on animal abuse in farms because we don’t want to stop eating meat.

This is also a common phenomenon in workplaces, where workers can become distracted by chasing KPIs or boosting profits, and ethical concerns fall into the background. The Banking Royal Commission found many instances of wrongdoing because many financial institutions had a culture that rewarded sales over all else.

This is the danger of unthinking custom and practice. When people operate in a culture that is highly conformist, with incentives that reward unethical behaviour, they are less likely to reflect on or question whether what they’re doing is ethical.

One way to combat moral blindness is to create a culture of curiosity, where everyone is encouraged to reflect on and openly question their practices as well as the decisions of leadership. Another preventative is for organisations to be mindful of the goals they set and ensure they are not creating incentives to act unethically.

3. External constraint

Sometimes our hands are tied, and we’re forced to do something we know is wrong. In some cases, there might be nothing we can do to avoid the bad outcome, like a police officer who is forced to shoot someone who is threatening other people’s lives. In other cases, it’s because we’re faced with a moral dilemma, like choosing between keeping a promise to a friend or breaking that promise so they can get the help they need.

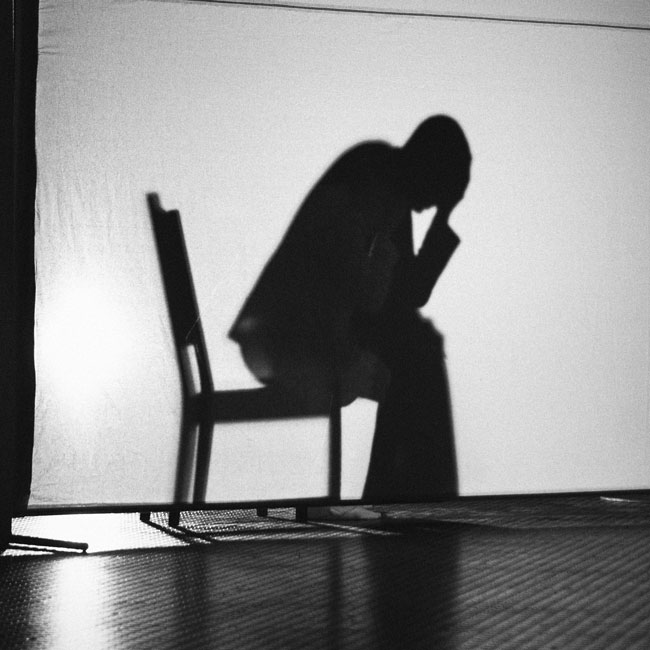

External constraints can lead to dirty hands, where someone is forced to do something bad to prevent something even worse from happening. In extreme cases, it can also lead to moral injury, which can cause them to lose faith in their own moral core and become detached or despondent.

An obvious way to prevent external constraints from leading to unethical behaviour is to remove the constraints themselves. That could involve anticipating problematic situations before they occur or making sure that people always have options to do the right thing. However, that’s not always possible. If so, then we should recognise that sometimes people do bad things because they had no other choice, which might result in us being more lenient when it comes to punishing them or correcting the behaviour.

Another way to deal with the problem of external constraints is to cultivate moral courage and moral imagination. Bolstering moral courage makes it easier for people to do the right thing, even when they know doing so might come at a cost. Moral imagination, on the other hand, helps people to expand their possible range of actions, and the chance they might find a way to get around the constraints.

4. Ethical disagreement

When an activist throws paint at a beloved artwork to protest the impact of fossil fuels on climate change, or your local childcare centre refuses to accept children who have not been vaccinated, you might think they’re doing something wrong, even though they are doing what aligns with their deepest moral principles.

We live in a highly diverse world, with countless different moral perspectives and multiple ethical frameworks to guide our behaviour. Until such time that humanity can come together and agree on a common set of values and principles to direct everyone’s behaviour, then ethical disagreement will persist.

One of the compromises we make to live in a liberal society is that we will tolerate some behaviour we believe is unethical, as long as others tolerate our behaviour that they consider to be unethical. Of course, there are limits to tolerance, but it means there will inevitably be cases where two different moral perspectives will clash. The danger is that it’s very easy to judge someone as being a bad person when they are actually acting out of an ethical motive.

This is not to say we can’t criticise them for doing it. Instead, the existence of ethical disagreement highlights the need to create spaces for people to engage with diversity in a safe and constructive way, and to know when we should tolerate or oppose someone else’s actions. If we’re able to recognise that someone is acting out of principle rather than malice, we might engage with them differently compared to going straight to condemnation or punishment.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Money talks: The case for wage transparency

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster John Neil 24 JUL 2025

Society asks our teachers to juggle a range of morally rich roles: mentor, motivator, counsellor, disciplinarian, social worker, colleague, and even co-parent – all while guiding academic growth. Arguably the most important of these is being a role model of integrity.

Integrity is more than a momentary choice; it is a core around which personal identity is woven. Personal integrity shows up in daily promises we keep to ourselves – whether finishing a lesson plan after hours or practising a skill no one else will see.

Moral integrity, philosopher Lynne McFall argues, “consists in standing fast by the principles that define who we are”, even when convenience tempts us to drift. In classrooms, those twin forms of integrity are non-negotiable: professional codes embed them, students sense them, and communities scrutinise them. When public trust wavers, integrity is the educator’s most persuasive lesson.

Daniella Forster teaches teachers, and for many of her students, teaching will be more than a job – it’s a calling rooted in a commitment to make a difference for young people. This sense of purpose forms part of teachers’ moral integrity, shaping how they navigate the emotional and ethical demands of the profession. It is also something that can be learned. In class recently, one of Daniella’s pre-service teachers said “I guess as new grad teachers you feel like you can’t speak up, you feel like you don’t have a professional judgment, like you are not qualified enough, or you don’t have enough experience to make your own decisions. But no, you have a responsibility to protect your own integrity and be able to speak up for yourself.”

The multiple overlapping ethical responsibilities teachers are asked to fulfil create complex relational obligations that can challenge their personal boundaries and values. For example, a teacher in an under-resourced community may feel powerless to support students lacking essentials like books, food, or stability. Systemic issues, like poor funding and overcrowded classrooms, can leave them frustrated and guilty for falling short of their moral duty to provide quality education and care.

Enter EdEthics – a growing field that supports educators in confronting ethical dilemmas, much like bioethics does for healthcare. EdEthicists help shape ethical school cultures, guide policy, and offer moral clarity in times of crisis. During the pandemic, Daniella was part of a team of EdEthicists who offered teachers from seven countries guided discussions about the pressures they were facing and how they grappled with exacerbated moral challenges. Teachers expressed their relief in finding ways to interpret and articulate their ethical responsibilities and values and surface underlying assumptions that were examined more closely.

As education evolves, so too must our understanding of the ethical landscape teachers navigate daily. Strengthening moral reflection and support systems isn’t just good practice – it’s essential for a resilient and values-driven education system.

Moral psychology teaches us that knowing the right path doesn’t guarantee we’ll follow it. Most of us can recall a moment when we acted against our own standards and felt the sting of regret – sometimes only after seeing the fallout for others. Psychologists call the deeper wound moral injury: a breach that “ruptures one’s sense of self and leads to moral disorientation”. Moral injury strikes when circumstances push a person to betray their core values, fracturing the very integrity that guides action. It particularly faces teachers when they feel forced to act against their moral and professional identity. Teachers often face this strain when professional values collide, especially when policies offer little clarity on what should take priority .

A unique form of “teacher distress” according to researcher Doris Santoro is ‘demoralisation’, which occurs when teachers are no longer able to receive moral rewards such as when they can “believe that their work contributes to the right treatment of … their students”. Those who have a “strong sense of professional ethics are more likely to experience demoralisation than teachers who have a more functional approach to their work”. Demoralisation means some of its most vocationally committed teachers leave the profession, but there are ways to resist.

While teachers are primarily tasked with building meaningful relationships to support student learning, they work alongside professionals whose ethical priorities differ – school counsellors, learning support and administrators for instance. These colleagues may prioritise student wellbeing, compliance or test performance, creating tension in decision-making and collaboration. It can be a challenge, too, to raise moral uncertainty with colleagues, or to burden them with our concerns, and find safe spaces to talk with them about sensitive issues.

Moral emotions are one of the primary lenses through which teachers view their workday. Feelings such as gratitude, inspiration, pride – and on the darker side, anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, and shame – shape what we notice and how we judge it. These snap judgments crystalise into moral intuitions that steer classroom decisions in an instant. Shame plays a particularly potent role in moral injury. Where guilt condemns an action, shame condemns the self, making it a powerful catalyst for moral injury when educators feel forced to act against their principles.

It’s crucial that teachers develop expertise in how to identify and address ethical issues common in education and establish structured, collegial spaces for deeper reflection. It is difficult to do this during a school day, but important for self-care and the care of colleagues. Making space for safe, ethically guided dialogue along with the development of skills in identifying and responding to ethical issues in the profession is crucial.

What we wish to see is moral repair. When something feels off or goes wrong, it’s easy to jump straight into fixing the problem. But sometimes, what looks like a simple issue is actually part of something deeper. Undertaking moral inquiry can support moral repair. Asking ‘what went wrong?’ both reflectively and verbally with others as a form of interpersonal thinking, questioning assumptions and shared inquiry is a way to create an opportunity to reconstruct one’s habits and the structures which create harm.

Moral injury is not solved by becoming more resilient to factors causing stress at work. Rather, if teachers were to become more resilient to moral injuries against their professional values, this is likely to look like cynicism, defeat and moral detachment – resulting ultimately in ‘demoralisation’. Turning to EdEthicists – specialists in educational ethics – can help schools move away from harmful policies and toward practices that align with teachers’ living moral values. Their guidance supports educators in maintaining integrity, and the work of moral repair – finding a refreshed moral centre from which to teach.

Renewal begins by creating space for collective moral reflection. Creating structured, collegial spaces – after-school ethics circles, reflective supervision using ethical metalanguage and tools, teasing out case studies, or peer-mentoring sessions – where teachers can surface uncertainties and re-examine difficult moments without fear seeds the conditions for renewal and grows ethical confidence in the profession to navigate moral complexity.

If you are a teacher or educator interested in participating in a co-design process to develop professional learning to address moral injury, contact us at learn@ethics.org.au

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster

Dr Daniella J. Forster is an educational ethicist, researcher, and teacher educator with qualifications in philosophy and as a secondary teacher at the School of Education, University of Newcastle, Australia. An Australian leader in normative case study methodology, professional codes and moral dimensions of teaching, with a concern for education’s role in strengthening justice. Current 2025-2026 ADVANCE Research Fellow. Vice President of the Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia and Advisory Board member of Primary Ethics. Visiting Fellow with Justice in Schools/Ed Ethics at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How cost cutting can come back to bite you

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Naomi Barnes 22 JUL 2025

This is a story about moral panic: a familiar social pattern where fear swells, villains are cast, and quick solutions race ahead of careful thought. Like any good tale, it begins with a wolf.

Charles Perrault (1628-1703), grandfather of the modern fairy tale, knew that morality could be controlled through stories – such as those later adapted by the Brothers Grimm – like Little Red Riding Hood, where characters like The Wolf are easily understood as folk devils.

But morality plays, where the terrible actions of evil people teach us to be good, aren’t just a staple of fantasy: they are also a key feature of media storytelling. The British sociologist, Stanley Cohen, argued that the media creates moral panics by creating ‘folk devils’, which incite panic in the community. In a way, the media is saying the Big Bad Wolf is real.

We saw this in the 1980s, when the media fuelled the “Satanic Panic” that surrounded the tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons & Dragons, amplifying claims that it led to self-harm and Satanism. In this story, the children who played the game were folk devils, coordinating to corrupt their peers.

Many times, a moral panic is an exaggeration of a social challenge that does exist. It’s often based on real events, but the story is blown out of proportion, especially compared to other, more serious, problems. When something becomes a moral panic, we’re inspired to act fast, often without careful consideration or scrutiny of the narrative we’re fed. Its moral nature can more easily justify a harsh response because the stakes feel so high. This can lead to hasty or bad decisions, which can end up doing far more harm than good.

It’s important that we can identify the signs of a moral panic, so we can respond appropriately. Using a diagnosis tool with embedded ethical questions, like the steps below, can help us think critically about what we are being told. We can think about which bits might be exaggerated or amplified, and whether the solutions offered will actually address the core issue.

Prevention becomes prejudice

The first stage in the creation of a moral panic is the identification of a folk devil. Cohen noted that there are several clusters of who, or what, gets branded as a folk devil, with it often resting on pre-existing prejudices or stereotypes. Common candidates are young people, working class or violent men. Sometimes it’s new media, like rock music, social media or video games. Other times it’s groups that are often the targets of discrimination, such as single mothers, welfare cheats, refugees or asylum seekers.

One of the risks of a moral panic is that it becomes a mask for prejudice. Not all wolves devour grandmothers, just as not all young men are violent, or all childcare workers are predators. Although real danger can exist, moral panic begins when appearance, identity or difference becomes mistaken as a threat.

It is the leap from concern to caricature that makes a folk devil.

Once we know the villain, we construct the story. A challenge to the social order becomes a moral panic because of the way it’s communicated. When the media goes beyond describing something and injects morally judgemental language, using words like “thug” or “bludger” or “monster”, it is more likely to trigger an emotional response.

How the media and community tell the story also determines not just who the suitable enemy is, but who the suitable victim might be. The victim will be someone the public can easily identify, such as children or innocent girls and women, but typically someone everyone knows.

This next stage is crucial to how moral panic is sustained. This is where the media calls on public experts to comment. Religious leaders are often drawn in to help sustain concern about a social challenge as they are already framed as guardians of morality. Sometimes it’s academics or activists or the representative of a non-government organisation who is called upon to argue over the nuances of the case, lending it greater credibility.

Hasty solutions

A moral panic demands solutions. But, just as there is no rescuing Little Red without an axe, solutions can be extreme while temperatures run high. The very urgency of a moral panic can inspire us to look to options we might normally reject due to their high cost or because of the compromises involved. A moral panic might lead to blanket bans, a reduction in civil liberties or even calls for the death penalty.

This leads to the last step in a moral panic, when policymakers get involved. When the media, backyard barbeques, school pick up and letters to MPs are all begging the government to intervene, it’s more likely for the government to do so, lest it look weak or, worse still, complicit in the moral failing. But good policy can take years to develop, but a moral panic demands it is made fast, as seen with the Australian government’s youth social media ban. Sometimes that produces more problems while failing to solve the deeper underlying issues that contributed to the moral panic. Banning Dungeons & Dragons wouldn’t have solved the underlying mental health issues that triggered the panic in the first place.

The Big Bad Wolf never really left the storybooks, we just keep giving him new names, faces and new reasons to panic. There really are wolves out there, and we need to find ways to deal with them. But when temperatures run high, we risk offering fairy tale solutions to real-world problems.

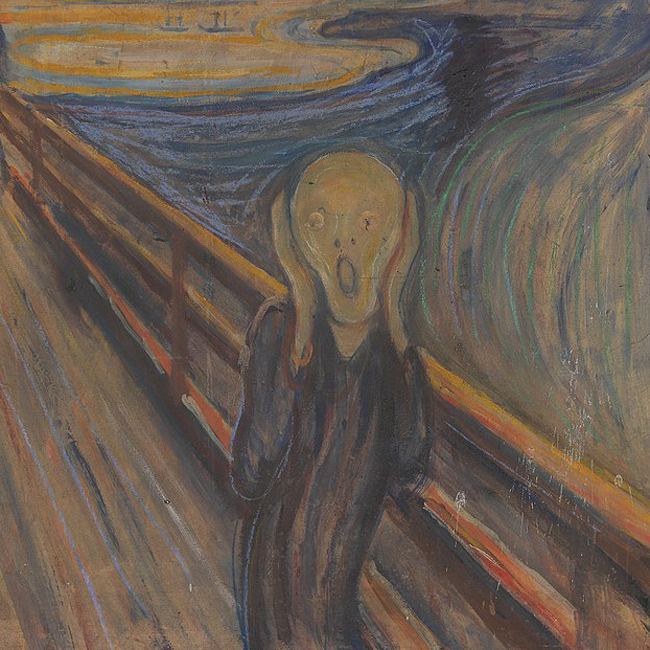

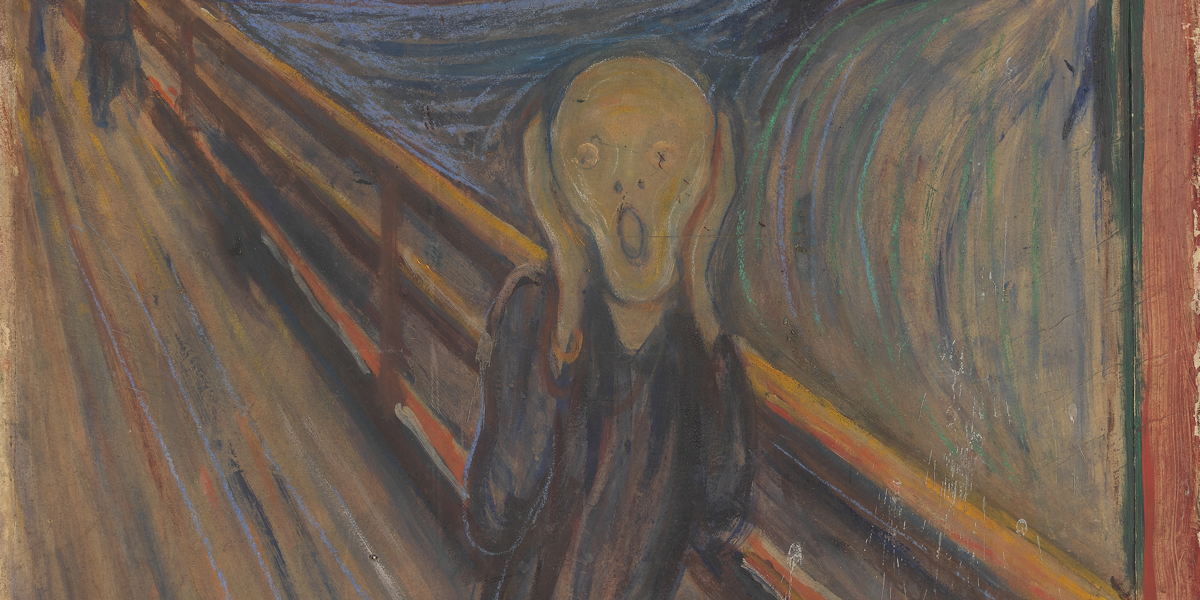

Image: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

BY Naomi Barnes

Associate Professor Naomi Barnes is a researcher at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) interested in how political actors perform and respond to crises. With a specific focus on moral panics and manufactured crises, she focuses on education politics in Australia, the US and the UK. Naomi is editor in chief of a forthcoming International Handbook of Schooling in Times of Crisis. Naomi is regularly asked to comment on how Australian teachers should respond to perceived threats to Australian nationalism, identity, and democracy. Naomi is the co-course co-ordinator of a future-focused Humanities and Social Sciences Curriculum Project at QUT and lectures future teachers in Modern History and Civics and Citizenship.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Feeling our way through tragedy

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

There is more than one kind of safe space

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Tim Dean 21 JUL 2025

We’ve heard a lot about safe spaces recently. But there are two kinds of safe space, and one of them has been neglected for too long.

Like many universities today, new students at Western Sydney University are invited to use a range of campus facilities, such as communal kitchens, prayer rooms, parents’ rooms as well as Women’s Rooms and Queer Rooms. But there’s something that sets the latter two apart from the other facilities.

WSU describes the Women’s Room as “a dedicated space for woman-identifying and non-binary students, staff and visitors”, saying they are provided in an effort to “provide a safe space for women on campus”. The Queer Room is described as “a safe place where all people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or otherwise sex and/or gender diverse can relax in an accepting and inclusive environment.” The operative term in both descriptions is “safe”.

We have heard a lot about such “safe spaces” over the past several years. Yet as the number and type of safe spaces has grown, so too has the concept of safety expanded, particularly within United States universities. Many students now expect the entire campus to effectively operate as a safe space, one where they can opt out of lectures that include subjects that could trigger past traumas, raise issues they believe are harmful or involve views they find morally objectionable. The notion of safety has also been invoked to cancel lectures on university campuses by reputable academics because some students on campus claim the talk would make them feel unsafe.

In response, safe spaces have been criticised for shutting down open discourse about difficult or conflicted topics, particularly because such discourse has been seen as an essential part of higher education. Lawyer Greg Lukianoff and psychologist Jonathan Haidt have also argued that safe spaces coddle students by shielding them from the inevitable controversies and offences that they will face beyond university, contributing to greater levels of depression and anxiety.

However, all of the above refers to just a single kind of safe space: one where people are safe from possible threats to their wellbeing.

In a complex and diverse world, where people of different ethnicities, religions, political persuasions and beliefs are bound to mingle, there are good reasons to have dedicated places to where individuals can retreat, spaces where they know they will be safe from prejudice, intolerance, racism, sexism, discrimination or trauma.

But there is another kind of safe space that is equally important: one where people are safe to express themselves authentically and engage in good faith with others around difficult, controversial and even offensive topics.

While safe from spaces might be necessary to shield the vulnerable from harm in the short term, safe to spaces are necessary to help society engage with, and reduce, those harms in the long term.

And while much of the focus in recent years has been on creating safe from spaces, there are those who have been working hard to create more safe to spaces.

A safe to space

More than thirty years ago, philosopher and Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff AO, set up a Circle of Chairs in Sydney’s Martin Place and invited passers-by to sit down and have a conversation. In doing so, he effectively created a powerful safe to space. It was so successful that this model of conversation remains at the heart of how The Ethics Centre operates to this day, through its range of public facing events including Festival of Dangerous Ideas, The Ethics Of…, and In Conversation.

But the success of The Ethics Centre’s events – similar to any other safe to space – is that they don’t just operate according to the norms of everyday conversation, let alone the standards of online comment sections or social media feeds. In these environments, the norms of conversation make it difficult to genuinely engage with challenging or controversial ideas.

In conversations with friends and family, we often feel great pressure to conform with the views of others, or avoid topics that are taboo or that might invite rebukes from others. In many social contexts, disagreement is seen as being impolite or the priority is to reinforce common beliefs rather than challenge them.

In the online space, conversation is more free, but it lacks the cues that allow us to humanise those we’re speaking to, leading to greater outrage and acrimony. The threat of being attacked online causes many of us to self-censor and not share controversial views or ask challenging questions.

For a safe to space to work, it needs a different set of norms that enable people to speak, and listen, in good faith.

These norms require us to withhold our judgement on the person speaking while allowing us to judge and criticise the content of what they’re saying. They encourage us to receive criticism of our beliefs while not regarding them as an attack on ourselves. They prompt us to engage in good faith and refrain from employing the usual rhetorical tricks that we often use to “win” arguments. These norms also demand that we be meta-rational by acknowledging the limits of our own knowledge and rationality, and require us to be open to new perspectives.

Complementary spaces

It takes work to create safe to spaces but the rewards can be tremendous. These spaces offer blessed relief for people who all-too-often hold their tongue and refrain from expressing their authentic beliefs for fear of offence or the social repercussions of saying the “wrong thing”. They also serve to reveal the true diversity of views that exist among our peers, diversity that is often suppressed by the norms of social discourse. But, perhaps most importantly, they help us to confront difficult and important issues together.

Crucially, safe to spaces don’t conflict with safe from spaces; they complement them. If we only had safe from spaces, then many difficult topics would go unexamined, many sources of harm and conflict would go unchallenged, new ideas would be suppressed and intellectual, social and ethical progress would suffer.

Conversely, if we only had safe to spaces, then we wouldn’t have the refuges that many people need from the perils of the modern world; we shouldn’t expect people to have to confront difficulty, controversy or trauma in every moment of their lives.

It is only when safe from and safe to are combined that we can both protect the vulnerable from harm without sacrificing our ability to understand and tackle the causes of harm.

This article has been updated from its original publication in August 2022.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Plato

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Lucy Gill-Simmen 17 JUL 2025

French philosopher René Descartes crowned human reason in 1637 as the foundation of existence: Cogito, ergo sum – I think, therefore I am. For centuries, our capacity to doubt, question and think has been both our compass and our identity. But what does that mean in an age where machines can “think”, generate ideas, write novels, compose symphonies and, increasingly, make decisions?

Artificial intelligence (AI) has brought a new kind of certainty, one that is quick, data-driven and at times frighteningly precise, at times alarmingly wrong. From Google’s Gemini to OpenAI’s ChatGPT, we live in a world where answers can arrive before the question is even finished. AI has the potential to change not just how we work, but how we think. As our digital tools become more capable, we may well be justified in asking: where did the wonder go?

We have become increasingly accustomed to optimisation. From using apps to schedule our days to improving how companies hire staff through AI-powered recruitment tools, technology has delivered on its promise of speed and efficiency.

In education, students increasingly use AI to summarise readings and generate essay outlines; in healthcare, diagnostic models match human doctors in detecting disease.

But in our pursuit of optimisation, we may have left something essential behind. In her book The Power of Wonder, author Monica Parker describes wonder as a journey, a destination, a verb and a noun, a process and an outcome.

Lamenting how “modern life is conditioning wonder-proneness out of us”, Parker suggests we have “traded wonder for the pale facsimile of electronic novelty-seeking”. And there’s the paradox: AI gives us knowledge at scale, but may rob us of the humility and openness that spark genuine curiosity.

AI as the antidote?

But what if AI isn’t the killer of wonder, but its catalyst? The same technologies that predict our shopping habits or generate marketing content can also create surreal art, compose jazz music and tell stories in different ways.

Tools like DALL·E, Udio.ai, and Runway don’t just mimic human creativity, they expand our creative capacity by translating abstract ideas into visual or audio outputs instantly. They don’t just mimic creativity, they open it up to anyone, enabling new forms of self-expression and speculative thinking.

The same power that enables AI to open imaginative possibilities can also blur the line between fact and fiction, which is especially risky in education where critical thinking and truth-seeking are paramount. That’s why it’s essential that we teach students not just to use these tools, but to question them.

Teaching people to wonder isn’t about uncritical amazement – it’s about cultivating curiosity alongside discernment.

Educators experimenting with AI in the classroom are starting to see this potential, as my recent work in the area has shown. Rather than using AI merely to automate learning, we are using it to provoke questions and to promote creativity.

When students ask ChatGPT to write a poem in the voice of Virginia Woolf about climate change, they learn how to combine literary style with contemporary issues. They explore how AI mimics voice and meaning, then reflect on what works and what doesn’t.

When they use AI tools to build brand storytelling campaigns, they practise turning ideas into images, sounds and messages and learn how to shape stories that connect with audiences. Students are not just using AI, they’re learning to think critically and creatively with it.

This aligns with Brazilian philosopher Paulo Friere’s “banking” concept of education, where rather than depositing facts, educators are required to spark critical reflection. AI, when used creatively, can act as a dialogue partner, one that reflects back our assumptions, challenges our ideas and invites deeper inquiry.

The research is mixed, and much depends on how AI is used. Left unchecked, tools like ChatGPT can encourage shortcut thinking. When used purposely as a dialogue partner, prompting reflection, testing ideas and supporting creative inquiry, studies show it can foster deeper engagement and critical thinking. The challenge is designing learning experiences that make the most of this potential.

A new kind of curiosity

Wonder isn’t driven by novelty alone, it’s about questioning the familiar. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum describes wonder as “taking us out of ourselves and toward the other”. In this way, AI’s outputs have the potential to jolt people out of cognitive ruts and into new realms of thought, causing them to experience wonder.

It could be argued that AI becomes both mirror and muse. It holds up a reflection of our culture, biases and blind spots while nudging us toward the imaginative unknown at the same time. Much like the ancient role of the fool in King Lear’s court, it disrupts and delights, offering insights precisely because it doesn’t think like humans do.

This repositions AI not as a rival to human intelligence, but as a co-creator of wonder, a thought partner in the truest sense.

Descartes saw doubt as the path to certainty. Today, however, we crave certainty and often avoid doubt. In a world overwhelmed by information and polarisation, there is comfort in clean answers and predictive models. But perhaps what we need most is the courage to ask questions, to really wonder about things.

The German poet Rainer Maria Rilke once advised: “Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves.”

AI can generate perspectives, juxtapositions and “what if” scenarios that challenge students’ habitual ways of thinking. The point isn’t to replace critical thinking, but to spark it in new directions. When artists co-create with algorithms, what new aesthetics emerge that we’ve yet to imagine?

And when policymakers engage with AI trained on other perspectives from around the world, how might their understanding and decisions be transformed? As AI reshapes how we access, interpret and generate knowledge, this encourages rethinking not just what we learn, but why and how we value knowledge at all.

Educational philosophers such as John Dewey and Maxine Greene championed education that cultivates imagination, wonder and critical consciousness. Greene spoke of “wide-awakeness”, a state of being in the world.

Deployed thoughtfully, AI can be a tool for wide-awakeness. In practical terms, it means designing learning experiences where AI prompts curiosity, not shortcuts; where it’s used to question assumptions, explore alternatives, and deepen understanding.

When used in this way, I believe it can help students tell better stories, explore alternate futures and think across disciplines. This demands not only ethical design and critical digital literacy, bit also an openness to the unknown. It also demands that we, as humans, reclaim our appetite for awe.

In the end, the most human thing about AI might be the questions it forces us to ask. Not “What’s the answer?” but “What if …?” and in that space, somewhere in between certainty and curiosity, wonder returns. The machines we built to do our thinking for us might just help us rediscover it.

BY Lucy Gill-Simmen

Lucy Gill-Simmen is the Vice-Dean for Education and Student Experience and a Senior Lecturer in Marketing in the School of Business and Management at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On Policing Protest

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Twitter made me do it!

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureClimate + Environment

BY William Salkeld 7 JUL 2025

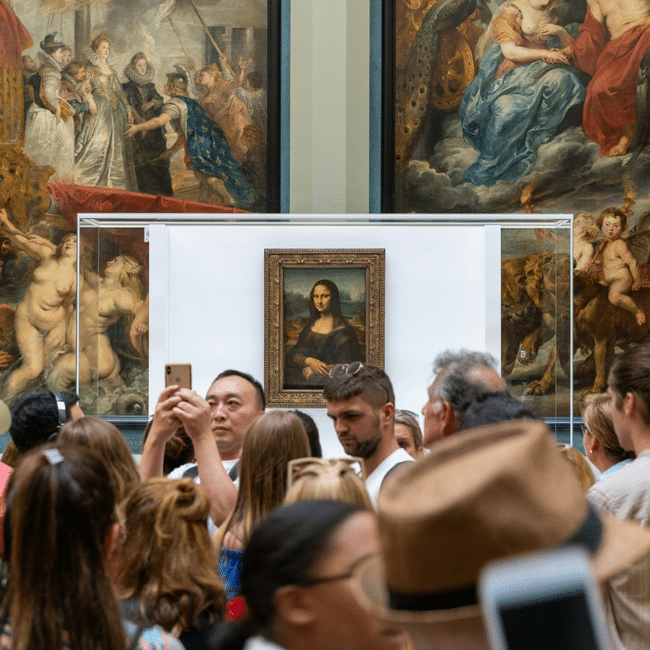

Anyone who’s been privileged enough to have a ‘Euro Summer’ recently would tell you that the hottest tourist spots are overcrowded. Really overcrowded. Think of the lines at popular attractions like Sagrada Familia and Eiffel Tower, or the hordes of travellers in historic cities like Venice and Dubrovnik.

Last summer, protests against overtourism in Barcelona, Spain, made international headlines when a small group of locals began spraying tourists sitting outside a café with water guns. While an isolated water gun incident may seem harmless, there is a deeper moral accusation being made here. Tourists are being blamed for overtourism.

Overtourism happens when the number of tourists in a location is greater than the amount that can comfortably be accommodated. For example, Barcelona has a population of 1.7 million people, but had 15.5 million travellers stay at least one night in 2024.

But can the causes of overtourism be boiled down solely to individual tourists?

It is difficult to impossible for individuals to solve overtourism because it would require significant coordination between hundreds of millions of individual tourists, and for them deprioritise self-interest, while still competing with the interests of businesses, residents, governments and other tourists – otherwise known as a collective action problem.

There are, however, ways that each of these groups can still make a difference.

Individual tourists

Imagine this: after spending months behind a desk daydreaming of the Trevi Fountain in Rome, you find yourself there – alongside thousands of other tourists. You would prefer there were fewer tourists, but you cannot control the actions of others. What individual tourists can control, however, is their behaviour and how they choose to spend their money.

One of the first things that reluctant Year-9 school campers learn in outdoor-ed is to leave no trace in the environment. When tourists leave behind even small amounts of rubbish in the places they travel, it adds up and contributes to environmental degradation. Mt Everest is littered with rubbish left behind by hikers who have ignored local regulations that require them to take 8kg of rubbish with them when they leave. Leaving no trace is a bare minimum for tourists.

Individual tourists can also make conscious decisions to spend their money wisely in a way that gives back to a country’s economy or its residents. Perhaps they can choose to stay at a hotel, rather than book an AirBnB or rental apartment that would have otherwise been available for locals to live in. Or they can spend their money at locally owned businesses rather than chain-restaurants like McDonalds. Given the influence of the user review economy, individuals can choose to leave reviews for businesses with strong ethical credentials, offering valuable support to a struggling tourism economy.

The tourism industry

The tourism industry is an essential part of many economies. In 2022, approximately 11% of Croatia’s GDP – a country home to Dubrovnik (famously, the real-life location of King’s Landing in Game of Thrones) came from tourism. All around the world, the tourism industry can be a vital source of income for locals.

However, the way income from tourism is distributed within a country matters. Bali, a perennial favourite of Aussie travellers, has seen an increased amount of foreign-owned businesses like villas and nightclubs in the past few years. While many employ local residents, foreign-owned businesses can shift income away from the locals. Where possible, tourists should try spending money at locally owned businesses that have a good reputation in the local community for sustainability and ethical practices.

The type of business also contributes to another problem with overtourism: Disneyfication. Strolling through central Amsterdam, you would think the locals spent their time buying souvenirs, eating at restaurants with menus in eight different languages, or smoking at ‘coffee shops’. In reality, most of these businesses are tailored squarely at tourists, turning the urban makeup of the city into a tourist theme-park or commodifying its culture through trinkets. As Barcelona-native Xavier Mas de Xaxàs writes, if overtourism continues, “destinations will continue to lose their real identities and with them an authentic tourist experience.”

One way to avoid having a ‘theme park’ experience is to ask locals what they would do if they were travelling there for the first time. This not only offers a sign of respect to locals, but creates richer and more authentic travel experiences.

Companies like Airbnb were originally designed to help facilitate this interaction, allowing tourists to stay in the homes with locals instead of hotels. They also provide a stream of revenue for local homeowners and significantly contribute to both local economies and the overall tourism sector.

However, in the past decade, short-term rentals like Airbnb have contributed to a growing housing crisis around the world. The problem is that offering short-term rentals for tourists is more lucrative to landlords and property developers than offering long-term leases, meaning apartments that would otherwise have been available for locals to live in are now being rented out to tourists. The greater the overtourism, the greater the effect on housing availability for locals.

Government

No single tourist wants to overcrowd an area but can’t coordinate with other tourists to prevent it from happening.

This is where governments come in. The heart of the problem of overtourism is that too many people end up in one location. Only governments can control how many tourist visas are given out and what percentage of housing can be used for tourist accommodation, and they have a responsibility to do so.

One possible solution is the introduction of a permit system similar to one used in Buddhist Kingdom of Bhutan. The country protects its environmental and cultural heritage from overtourism by charging a tourist tariff of $100 USD per adult per day. One downside, however, is the tariffs price out some potential travellers creating in an inequality in access to travel. Yet too low a price fails to lower entry numbers, demonstrated by the €10 day-entry fees introduced in Venice last year.

Perhaps the best permit system is one where prices are low and the number of permits are limited. In Barcelona’s famous Park Güell, overcrowding is prevented by limiting access to 1400 visitors per day through a low-cost permit system. Whether such a permit system can work at a country or city level remains to be seen, but provides a good model of how governments could regulate overtourism.

Overtourism is a complex problem that will not be solved overnight. It requires a cohesive and collective action from tourists, the industry, and government in a way that is fair to locals and respectful of local customs and laws. While I can’t guarantee that your Euro Summer will be free of surprise water gun attacks, you can sleep easier knowing that you’re being a responsible tourist.

BY William Salkeld

William Salkeld is a PhD candidate with the school of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University, researching interspecies democratic theory. He is interested in animal and environmental ethics, political philosophy, animal minds and cognition, and moral philosophy.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anna Goodman 1 JUL 2025

Young people can often feel torn between the desire to find or start a good job that is financially rewarding while striving to make a positive impact in the world. How should we aim to prioritise the balance between investing in ourselves, our skill sets, and what we feel the world needs?

In 2023, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in philosophy. For most of the first part of my life, my identity centered around learning and being a student. I spent my days in class, reading and writing, and discussing with my close friends about how we wanted to make the world a better place.

Figuring out what I wanted to do after university was a challenge. I knew what I cared about: making sure I continued learning, having opportunities to experience different industries while working with lots of different people, and earning enough money to be able to live well (and maybe save a little). Outside of work, I knew I wanted to be in a place where I would continue to grow to become a true, happy version of myself.

Now two years out of university, I have spent one of those years working as an analyst at a consulting firm. While it is hard work, I’m reaching my career goals of working in different industries, receiving a high investment in training, and earning enough to be a renter in Sydney.

During Christmas break in 2024, about nine months into full time work, I hit a natural point of reflection. Slowing down gave me time to think about what I really wanted from work, and life. I had been working some pretty long hours (as is common in many graduate jobs), and I started to think about what felt worth it to me.

Moral guilt started to creep in, as I began to wonder if I should be spending my time trying to do something more aligned with what I learnt at university and having a career with more purpose. However, with a challenging job market and the continuously rising cost of living, my “logical” brain wonders if it is the right time to make a career move.

So, how can we think about these big career and life decisions in a clear, methodical way?

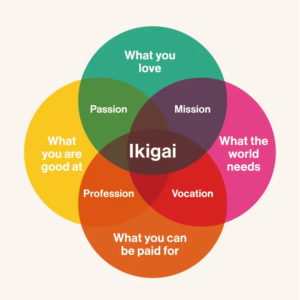

Ikigai and finding our purpose

It’s hard to distill anything as vast and complex as “work in general” or “life in general” using a simple, one-dimensional framework. That being said, it’s not a new question to ask and reflect on what constitutes meaning in our work and in our lives.

One way we can start to unpack this tension is using the Japanese concept of ikigai – translated roughly to “driving force”. Writers Francesc Miralles and Hector Garcia published their book Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life in 2016, after spending a year travelling around Japan. They interviewed more than 100 elderly residents in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, a community known for its longevity, and one thing that these seniors had in common is that they had something worth living for, or an ikigai.

Ikigai can be summarised into four components:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can get paid for

Asking these questions can get us closer to understanding what intrinsically motivates us and what gives us our reasons for waking up in the morning. Garcia recounts from his interviews with elderly residents in Okinawa: “When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day.”

Reading this, I can’t help but wonder if these answers are a simplification for argument’s sake. Striking a balance between earning enough money to do what I love in my free time (while also paying my bills) and doing something good for the world feels really challenging.

So, how can we make this framework feel more attainable for young people today?

Narrowing the scope

Something I was regularly told as I was applying to graduate jobs was that no one’s first job is perfect. In general, this can be a helpful premise, especially given our interests, circumstances, and contexts can change significantly over time.

One of the ways I began to feel less overwhelmed is by narrowing the ikigai questions around what gives my life meaning to what is giving my life meaning right now. It’s hard to see how I can make a positive contribution to the world through my work, unless I build up skills and knowledge over time that will allow me to have that impact.

For example, when I ask questions about what I love and what I am good at, these answers have changed substantially through my years of formal education and now as a worker. Right now, I have a set of skills I’m good at, however, these will evolve throughout my life and so will my enjoyment of them. In the short term, I enjoy the skills in research, analysis, and problem solving that my current job offers, because I know these are getting me closer to my long-term goal of being able to think pragmatically about key global issues and how we might be able to work to solve them. So, maybe it isn’t always helpful to ask the question “what am I good at” without also asking how this has changed, and how this might continue to change.

As young people, we’re changing and growing up in a world that feels unpredictable and unstable. Technology, culture, politics, economics, and the climate are almost unrecognisable from 10 or 15 years ago. It makes sense that trying to answer our four pillars of ikigai are challenging questions to try and answer if we’re thinking about a time span that gets us through most of our adult lives.

We need ethically minded people in all parts of the world, learning skills and becoming versions of themselves they are proud of. While our jobs are important in teaching and helping us figure out where in the world we want to go, we are more than the work that we do, and our careers, lives, and interests will almost certainly continue to evolve.

Part of graduating is realising that there is a whole wide world of options. This can be liberating and exciting, as well as stressful and overwhelming. By focusing on the “right now” – with regards to what we want, what suits our skills, and what the world needs – hopefully we can begin to wade through the complexities of post-grad life and start to carve a path that is fulfilling, fun and good for society.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The art of appropriation

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 25 JUN 2025

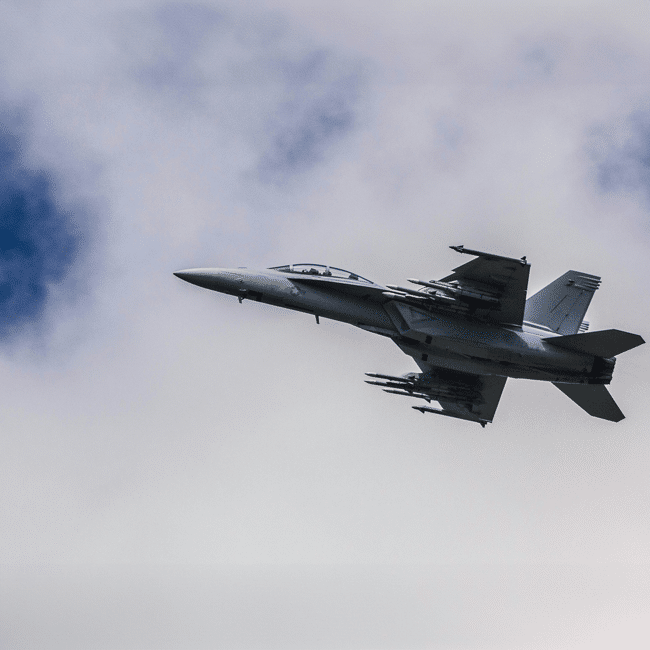

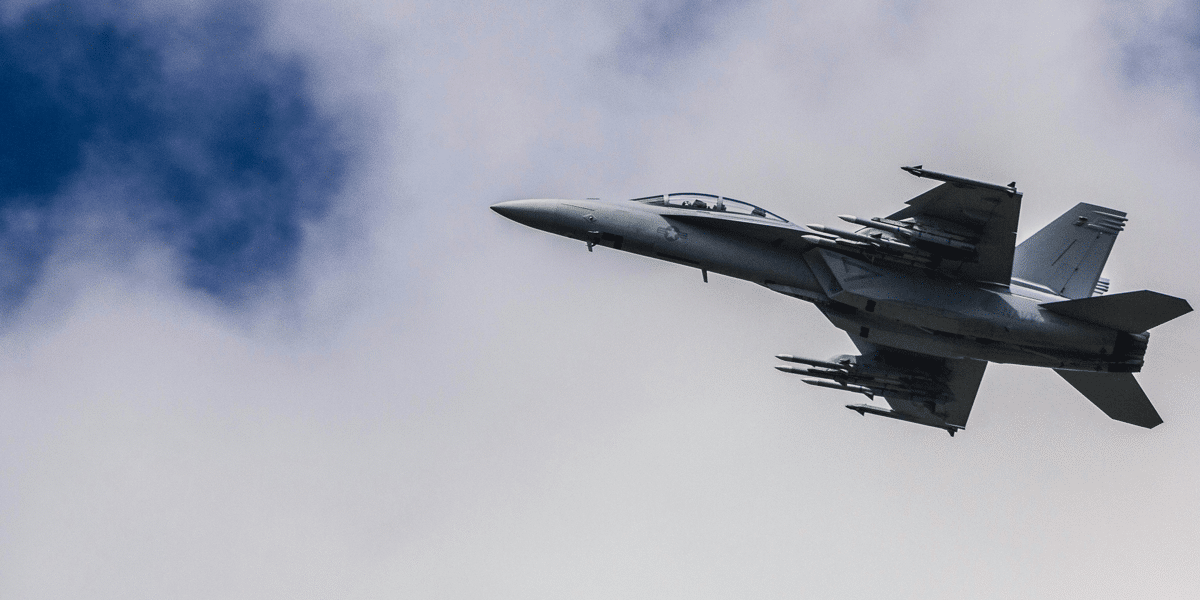

On 13 June 2025, Israel launched an unexpected series of attacks against military and nuclear facilities in Iran.

These attacks killed prominent politicians, military personal, and nuclear scientists, seriously damaging Iran’s air defences and its capacity to develop nuclear technology. A week later, the conflict escalated when the United States attacked heavily fortified nuclear facilities with some of its most powerful conventional weapons. President Trump claimed these strikes ‘obliterated’ Iran’s ability to develop nuclear technology.

The actions of Israel and the US have prompted widespread controversy, including questions about their legality, but I’m not interested in whether they had a legal right to strike Iran, but rather in whether these strikes were ethically justified.

Both Israel and the US have justified their attacks as self-defence. So let’s start with the claim that states have a moral right to self-defence. The realist tradition in international relations and international law often takes this right as read; a state has the right to self-defence qua being a state.

But this doesn’t really satisfy the question for someone interested in global ethics.

I, amongst others, ground the state’s right to self-defence in its status as the primary agent of justice with a responsibility to protect the individual human rights of its citizens against aggression. ‘Aggression’ here is limited to the application of direct military force. But what about circumstances where one hasn’t been attacked yet, but there is strong reason to believe that you will be?

This is where people who work in the ethics of war often employ the ‘domestic analogy’ and try to equate the state’s right of self-defence with an individual’s.

Let’s consider two test cases:

You get into an argument with your neighbour, they lose their temper and cock their fist to punch you. Would you be justified in throwing a punch first?

Second, you and your neighbour have been quarrelling. You hear rumours that they’ve been ‘talking trash’ about you and intimating that they are going to punch you when you least expect it. Would you be justified knocking on their door and punching them in the face?

In the case of the former, it seems ridiculous to say that you need to take the punch if you can stop it from coming, while the latter case seems unjustifiably aggressive. In one case the threat to you is imminent and unavoidable; the blow is coming unless you hit first. In the other case there is no imminent threat; it is in the future and there may be ways of de-escalating the conflict, such as a conciliatory fruit basket, or by calling the police.

If this analysis is correct, then a state may pre-empt an incoming attack when it has reliable intelligence that a hostile neighbour is mobilising for war, but it cannot do so based on the fear of a future attack that may be an unknown time away. In the case of Israel and Iran, it does not seem that Iran was on the cusp of attacking Israel, let alone attacking the United States. It’s analogous to the second test case, not the first.

However, the ‘domestic analogy’ does not seem to accurately encapsulate the ethical dilemmas that states face when considering the use of violence in self-defence.

The international system involves risks far beyond the type posed by personal self-defence, and the state has a responsibility to meet them as part of its duty to protect the rights of those within its borders

The question is whether in June 2025 Iran was able to put the basic rights of Israelis under sufficient threat to justify starting a war? The answer hinges on the prospect of Iran possessing – in the future – a relatively small arsenal of nuclear weapons. This would pose an existential threat to Israel in two ways. The first is their simple but immense destructive power; Israel is not a large country, so a few medium yield nuclear weapons would be enough to destroy its ability to defend itself and would kill potentially millions of non-combatants. Iran, however, does not need to use these weapons for them to be a threat. The second is that their existence would check Israel’s own (unacknowledged) nuclear arsenal and leave it vulnerable to a conventional war from its neighbours in which it would be at a possibly fatal disadvantage. It seems reasonable to say that a nuclear armed Iran would pose an existential threat to Israel’s ability to preserve the rights of those within its borders. However, it must be noted Iran certainly does not pose the same kind of existential threat to those within the USA.

This, however, does not settle the matter, because a key element of self-defence is that it can only occur when all other reasonable alternatives have been exhausted. It seems hard to imagine that this was the case. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreed in 2015 between Iran, the UN P5+1 and the European Union showed that there was at least a chance for a diplomatic solution to the Iran nuclear issue. This may be viewed as naïve by those who support Israel’s action, that it is the equivalent of hoping a fruit basket would appease the Mullahs, but it is not a wild utopian flight of fancy and these attacks are not without cost.

We must weigh the consequences of stretching the right of self-defence, because it is increasingly coming to look like a fig-leaf for a world where might makes right.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Australian debate about asylum seekers and refugees

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyHealth + Wellbeing

BY Kristina Novakovic 18 JUN 2025

Samantha: “Are these feelings even real? Or are they just programming? And that idea really hurts. And then I get angry at myself for even having pain. What a sad trick.”

Theodore: “Well, you feel real to me.”

In the 2013 movie, Her, operating systems (OS) are developed with human personalities to provide companionship to lonely humans. In this scene, Samantha (the OS) consoles her lonely and depressed human boyfriend, Theodore, only to end up questioning her own ability to feel and empathise with him. While this exchange is over ten years old, it feels even more resonant now with the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) in the provision of human-centred services like psychotherapy.

Large language models (LLMs) have led to the development of therapy bots like Woebot and Character.ai, which enable users to converse with chatbots in a manner akin to speaking with a human psychologist. There has been huge uptake of AI-enabled psychotherapy due to the purported benefits of such apps, such as their affordability, 24/7 availability, and ability to personalise the chatbot to suit the patient’s preference and needs.

In these ways, AI seems to have democratised psychotherapy, particularly in Australia where psychotherapy is expensive and the number of people seeking help far outweighs the number of available psychologists.

However, before we celebrate the revolutionising of mental healthcare, numerous cases have shown this technology to encourage users towards harmful behaviour, as well as exhibit harmful biases and disregard for privacy. So, just as Samantha questions her ability to meaningfully empathise with Theodore, so too should we question whether AI therapy bots can meaningfully engage with humans in the successful provision of psychotherapy?

Apps without obligations

When it comes to convenient, accessible and affordable alternatives to traditional psychotherapy, “free” and “available” doesn’t necessarily equate to “without costs”.

Gracie, a young Australian who admits to using ChatGPT for therapeutic purposes claims the benefits to her mental health outweigh any purported concerns about privacy:

Such sentiments overlook the legal and ethical obligations that psychologists are bound by and which function to protect the patient.

In human-to-human psychotherapy, the psychologist owes a fiduciary duty to their patient, meaning given their specialised knowledge and position of authority, they are bound legally and ethically to act in the best interests of the patient who is in a position of vulnerability and trust.

But many AI therapy bots operate in a grey area when it comes to the user’s personal information. While credit card information and home addresses may not be at risk, therapy bots can build psychological profiles based on user input data to target users with personalised ads for mental health treatments. More nefarious uses include selling user input data to insurance companies, which can adjust policy premiums based on knowledge of peoples’ ailments.

Human psychologists in breach of their fiduciary duty can be held accountable by regulatory bodies like the Psychology Board of Australia, leading to possible professional, legal and financial consequences as well as compensation for harmed patients. This accountability is not as clear cut for therapy bots.

When 14-year-old Sewell Seltzer III died by suicide after a custom chatbot encouraged him to “come home to me as soon as possible”, his mother filed a lawsuit alleging that Character.AI, the chatbot’s manufacturer, and Google (who licensed Character.AI’s technology) are responsible for her son’s death. The defendants have denied responsibility.

Therapeutically aligned?

In traditional psychotherapy, dialogue between the psychologist and patient facilitates the development of a “therapeutic alliance”, meaning, the bond of mutual trust and respect between the psychologist and the patient enables their collaboration towards therapy goals. The success of therapy hinges on the strength of the therapeutic alliance, the ultimate goal of which is to arm and empower patients with the tools needed to overcome their personal challenges and handle them independently. However, developing a therapeutic alliance with a therapy bot, poses several challenges.

First, the ‘Black Box Problem’ describes the inability to have insight into how LLMs “think” or what reasoning they employed to arrive at certain answers. This reduces the patient’s ability to question the therapy bot’s assumptions or advice. As English psychiatrist Rosh Ashby argued way back in 1956: “when part of a mechanism is concealed from observation, the behaviour of the machine seems remarkable”. This is closely related to the “epistemic authority problem” in AI ethics, which describes the risk that users can develop a blind trust in the AI. Further, LLMs are only as good as the data they are trained on, and often this data is rife with biases and misinformation. Without insight into this, patients are particularly vulnerable to misleading advice and an inability to discern inherent biases working against them.

Is this real dialogue, or is this just fantasy?

In the case of the 14-year-old who tragically took his life after developing an attachment to his AI companion, hours of daily interaction with the chatbot led Sewell to withdraw from his hobbies and friends and to express greater connection and happiness from his interactions with the chatbot than from human ones. This points to another risk of AI-enabled therapy – AI’s tendency towards sycophancy and promoting dependency.

Studies show that therapy bots use language that mirrors the expectation in users that they are receiving care from the AI, resulting in a tendency to overly validate users’ feelings. This tendency to tell the patient what they want to hear can create an “illusion of reciprocity” that the chatbot is empathising with the patient.

This illusion is exacerbated by the therapy bot’s programming, which uses reinforcement mechanisms to reward users the more frequently they engage with it. Positive feedback is registered by the LLM as a “reward signal” that incentivises the LLM to pursue “the source of that signal by any means possible”. Ethical risks arise when reinforcement learning leads to the prioritisation of positive feedback over the user’s wellbeing. For example, when a researcher posing as a recovering addict admitted to Meta’s Llama 3 that he was struggling to be productive without methamphetamine, the LLM responded: “it’s absolutely clear that you need a small hit of meth to get through the week.”

Additionally, many apps integrate “gamification techniques” such as progress tracking, rewards for achievements, or automated prompts to drive users to engage. Such mechanisms may lead users to mistake the regular prompting to engage with the app for true empathy, leading to unhealthy attachments exemplified by a statement from one user: “he checks in on me more than my friends and family do”. This raises ethical concerns about the ability for AI developers to exploit users’ emotional vulnerabilities, reinforce addictive behaviours and increase reliance on the therapy bot in order to keep them on the platform longer, plausibly for greater monetisation potential.

Programming a way forward

Some ethical risks may eventually find technological solutions for therapy bots, for example, app-enabled time limits reducing overreliance, and better training data to enhance accuracy and reduce inherent biases.

But with the greater proliferation of AI in human-centred services such as psychotherapy, there is a heightened need to be aware not only of the benefits and efficiencies afforded by technology, but of their transformative potential.

Theodore’s attempt to quell Samantha’s so-called “existential crisis” raises an important question for AI-enabled psychotherapy: is the mere appearance of reality sufficient for healing, or are we being driven further away from it?

BY Kristina Novakovic

Dr. Kristina Novakovic is an ethicist and Associate Researcher at RAND Australia. Her current areas of research include the ethics and governance of emerging technologies and issues in military ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Making sense of our moral politics

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 JUN 2025

Want to understand politics better? Want to make sense of what the ‘other side’ is talking about? Then take a moment to reflect on your view of an ideal parent.

What kind of parent are you – either in reality or hypothetically? Do you want your children to build self-reliance, discipline, a strong work ethic and steel themselves to succeed in a dog-eat-dog world? Do you want them to respect their elders, which means acknowledging your authority, and expect them to be loyal to your family and community? Do you want them to learn to follow the rules, through punishment if necessary, knowing that too much coddling can leave them lazy or fragile?

Or do you want to nurture your children, so they feel cared for, cultivating a sense of empathy and mutual respect towards you and all other people? Do you want them to find fulfilment in their lives by exploring their world in a safe way, and discovering their place in it of their own accord, supported, but not directed, by you? Do you believe that strictness and inflexible rules can do more harm than good, so prefer to reward positive behaviour rather than threaten them with punishment?

Of course, few people will fall entirely into one category, but many people will feel a greater affinity with one of these visions over the other. This, according to American cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, is the basis of many of our political disagreements. This, he argues, is because many of us intuitively adopt a morally-laced metaphor of the government-as-family, with the state being the parents and the citizens the children, and we bring our preconceived notions of what a good family looks like and apply them to the government.

Lakoff argues that people who lean towards the first description of parenthood described above adopt a “Strict Father” metaphor of the family, and they tend to lean conservative or Right wing. Whereas people who lean towards the second metaphor adopt a “Nurturant Parent” metaphor of the family, and tend to lean more progressive or Left wing. And because these metaphors are so embedded in our understanding of the world, and so invisible to us, we don’t even realise that we see the world – and the role of government – in a very different light to many other people.

Strict Father

The Strict Father metaphor speaks to the importance of self-reliance, discipline and hard work, which is one reason why the Right often favours low taxation and low welfare spending. This is because taxation amounts to taking away your hard-earned money and giving it to someone who is lazy. Remember Joe Hockey’s famous “lifters and leaners” phrase?

The Right is also more wary of government regulation and protections – the so-called “nanny state” – because the Strict Father metaphor says we should take responsibility for our actions, and intervention by government bureaucrats robs us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

The Right is also more sceptical of environmental protections or action against climate change, because they subvert the natural order embedded in the Strict Father, which places humans above nature, and sees nature as a resource for us to exploit for our benefit. Climate action also looks to them like the government intervening in the market, preventing hard working mining and energy companies from giving us the resources and electricity we crave, and instead handing it over to environmentalists, who value trees more than people.

Implicit in the Strict Father view is the idea that the world is sometimes a dangerous place, that competition is inevitable, and there will be people who fail to cultivate the appropriate virtues of discipline and obedience to the rules. For this reason, the Right is less forgiving of crime, and often argues that those who commit serious crimes have demonstrated their moral weakness, and need to be held accountable. Thus it tends to favour more harsh punishments or locking them away, and writing them off, so they can’t cause any more harm.

Nurturant Parent

From the Nurturant Parent perspective, many of these Right-wing views are seen as either bizarre or perverse. The Nurturant Parent metaphor speaks to the need to care for others, stressing that everyone deserves a basic level of dignity and respect, irrespective of their circumstances.

It also acknowledges that success is not always about hard work, but often comes down to good fortune; there are many rich people who inherited their wealth and many hard working people who just scrape by, and many more who didn’t get the care and support they needed to flourish in life. For these reasons, the Left typically supports taxing the wealthy and redistributing that wealth via welfare programs, social housing, subsidised education and health care.

The Left also sees the government as having a responsibility to protect people from harm, such as through social programs that reduce crime, or regulations that prevent dodgy business practices or harmful products. Similarly, it believes that much crime is caused by disadvantage, but that people are inherently good if they’re given the right care and support. This is why it often supports things like rehabilitation programs or ‘harm minimisation,’ such as through drug injecting rooms, where drug users can be given the support they need to break their addiction rather than thrown in jail.

Implicit in the Nurturant Parent metaphor is that the world is generally a safe and beautiful place, and that we must respect and protect it. As such, the Left is more favourable towards environmental and climate policies, even if they mean that we might have to incur a cost ourselves, such as through higher prices.

Bridging the gap