The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 7 DEC 2018

Before there were candles and doughnuts, there was a Greek king and some very pissed off Jews.

Right now, Jews all around the world are observing Hanukkah. It began on the 2nd of December and will last until the 10th.

Even though it’s nicknamed “The Festival of Lights” for its distinctive candles, Hanukkah is also a nod to military rebellion. Here’s how the story goes.

It’s the second century BCE. The Greek Selucid Empire is in power and Antiochus, the king, wants the Jewish community to finally abandon their traditions and fully embrace wider Greek culture.

Some Jews had already assimilated. But for Antiochus to have total control over the empire, the pocket of devout ones need to as well. Since they’re not giving up without a fight, he decides imperial force is necessary.

Antiochus vandalises their most sacred temple and bans Jews from praying or performing ritual sacrifice there. An altar to Zeus is propped up, pigs are sacrificed on it, Sabbath is forbidden and circumcision is banned. Dissenters are killed. Judaism is outlawed by the state.

Predictably, there is large scale revolt. The Maccabees, a Jewish warrior family, violently seize the temple back. Once they and their allies purify it to their standards and replace the pagan icons with their own, they finally light the menorah, the sacred lampstand in the temple.

There’s only just enough oil to light the candles for one day. But according to legend, these candles miraculously stayed lit for eight entire days, marking them as a victorious time of “joy and honour”.

This is why on Hanukkah, Jews traditionally eat festive foods fried in oil and light their own lamps. Each day, they eat potato fritters called latkes and jelly doughnuts called soufjanyiot, sing special songs, play dreidel games and recite prayers. People give presents and money, and kids get chocolate coins. It’s an eight-day feast of leisure.

But it wasn’t always like that. Some rabbis have understandably been uncomfortable with Hanukkah’s military undertones. Others have pointed out that celebrating the conflict between Jewish secularism and fundamentalism is a little odd.

But with the advent of Zionism and the state of Israel, Hanukkah has taken on new life. From a minor holiday that emphasised the miracle of the oil, Hanukkah today is seen as a symbol of resistance against injustice and oppression.

It’s now been nearly eight decades since the Holocaust. There is a menorah in Midtown Manhattan dedicated to the victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue mass shooting. There is another in front of Brandenburg Gate where the Nazi flags once hung.

Amid rising concern over anti-Semitism, illiberalism in Israel, and contradictions of ‘Jewish Christmas’, maybe it’s the historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah that is the most Jewish thing of all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

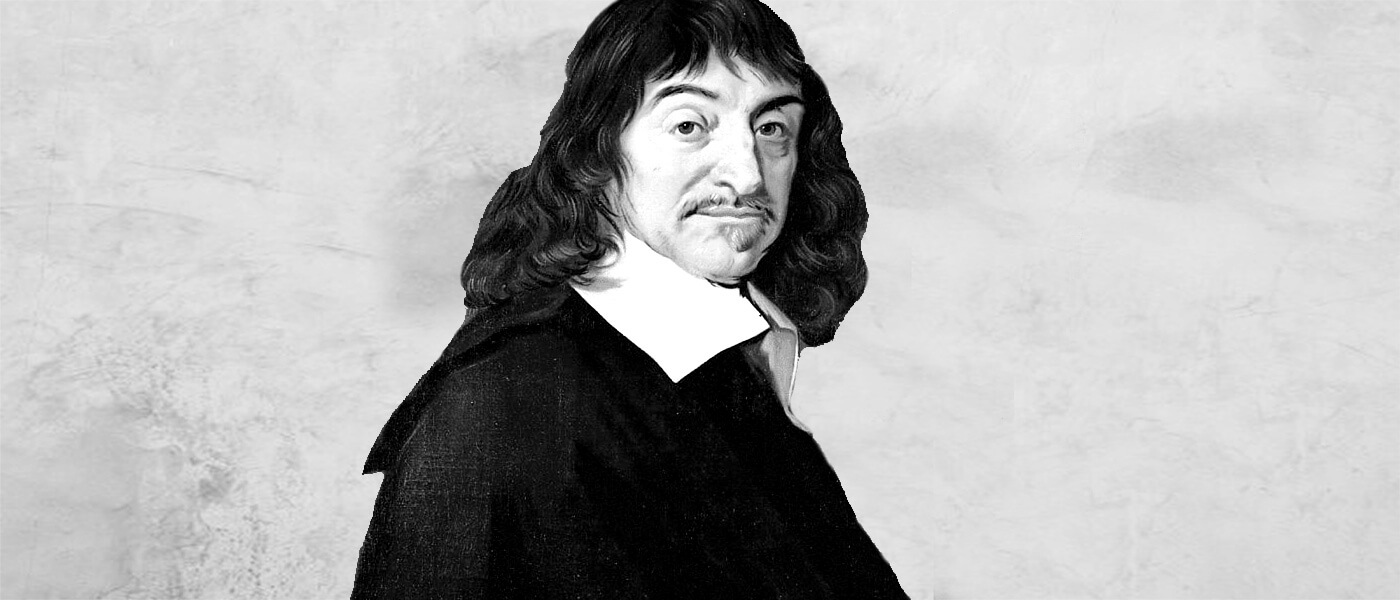

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 23 NOV 2018

Technology needs to be designed to a set of basic ethical principles. Designers need to show how. Matt Beard, co-author of a new report from The Ethics Centre, demands more from the technology we use every day.

In The Amazing Spider-Man, a young Peter Parker is coming to grips with his newly-acquired powers. Spider-Man in nature but not in name, he suddenly finds himself with increased reflexes, strength and extremely sticky hands.

Unfortunately, the subway isn’t the controlled environment for Parker to awaken as a sudden superhuman. His hands stick to a woman’s shoulders and he’s unable to move them. His powers are doing exactly what they were designed to do, but with creepy, unsettling effects.

Spider-Man’s powers aren’t amazing yet; they’re poorly understood, disturbing and dangerous. As other commuters move to the woman’s defence, shoving Parker away from the woman, his sticky hands inadvertently rip the woman’s top clean off. Now his powers are invading people’s privacy.

A fully-fledged assault follows, but Parker’s Spider-Man reflexes kick in. He beats his assailants off, sending them careening into subway seats and knocking them unconscious, apologising the whole time.

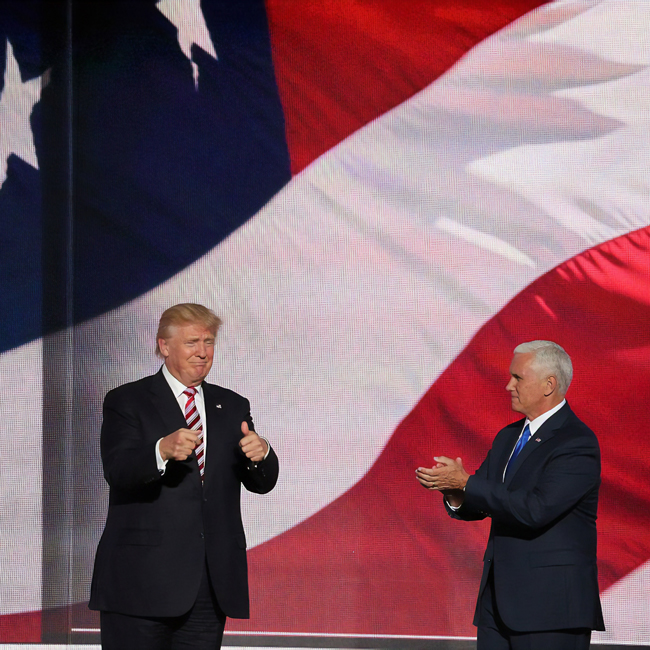

Parker’s unintended creepiness, apologetic harmfulness and head-spinning bewilderment at his own power is a useful metaphor to think about another set of influential nerds: the technological geniuses building the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’.

Sudden power, the inability to exercise it responsibly, collateral damage and a need for restraint – it all sounds pretty familiar when we think about ‘killer robots’, mass data collection tools and genetic engineering.

This is troubling, because we need tech designers to, like Spider-Man, recognise (borrowing from Voltaire) that “with great power comes great responsibility”. And unfortunately, it’s going to take more than a comic book training sequence for us to figure this out.

For one thing, Peter Parker didn’t seek and profit from his powers before realising he needed to use them responsibly. For another, it’s going to take something more specific and meaningful than a general acceptance of responsibility for us to see the kind of ethical technology we desperately need.

Because many companies do accept responsibility, they recognise the power and influence they have.

Just look at Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony before the US Congress:

It’s not enough to connect people, we need to make sure those connections are positive. It’s not enough to just give people a voice, we need to make sure people aren’t using it to harm other people or spread misinformation. It’s not enough to give people control over their information, we need to make sure the developers they share it with protect their information too. Across the board, we have a responsibility to not just build tools, but to make sure those tools are used for good.

Compare that to an earlier internal memo – which was intended to be a provocation more than a manifesto – in which a Facebook executive is far more flippant about their responsibility.

We connect people. That can be good if they make it positive. Maybe someone finds love. Maybe it even saves the life of someone on the brink of suicide. So we connect more people. That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people.

We can expect more from tech companies. But to do that, we need to understand exactly what technology is. This starts by deconstructing one of the most pervasive ideas going around called “technological instrumentalism”, the idea that tech is just a “value-neutral” tool.

Instrumentalists think there’s nothing inherently good or bad about tech because it’s about the people who use it. It’s the ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’ school of thought – but it’s starting to run out of steam.

What instrumentalists miss are the values, instructions and suggestions technologies offer to us. People kill people with guns, and when someone picks up a gun, they have the ability to engage with other people in a different way – as a shooter. A gun carries a set of ethical claims within it – claims like ‘it’s sometimes good to shoot people’. That may indeed be true, but that’s not the point – the point is, there are values and ethical beliefs built into technology. One major danger is that we’re often not aware of them.

Encouraging tech companies to be transparent about the values, ethical motivations, justifications and choices that have informed their design is critical to ensure design honestly describes what a product is doing.

Likewise, knowing who built the technology, who owns it and from what part of the world they come from helps us understand whether there might be political motivations, security risks or other challenges we need to be aware of.

Alongside this general need for transparency, we need to get more specific. We need to know how the technology is going to do what it says it’ll do and provide the evidence to back it up. In Ethical by Design, we argue that technology designers need to commit to a set of basic ethical principles – lines they will never cross – in their work.

For instance, technology should do more good than harm. This seems straightforward, but it only works if we know when a product is harming someone. This suggests tech companies should track and measure both the good and bad effects their technology has. You can’t know if you’re doing your job unless you’re measuring it.

Once we do that, we need to remember that we – as a society and as a species – remain in control of the way technology develops. We cultivate a false sense of powerlessness when we tell each other how the future will be, when artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence and how long it will be until we’ve all lost our jobs.

Technology is something we design – we shape it as much as it shapes us. Forgetting that is the ultimate irresponsibility.

As the Canadian philosopher and futurist Marshal McLuhan wrote, “There is absolutely no inevitability, so long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

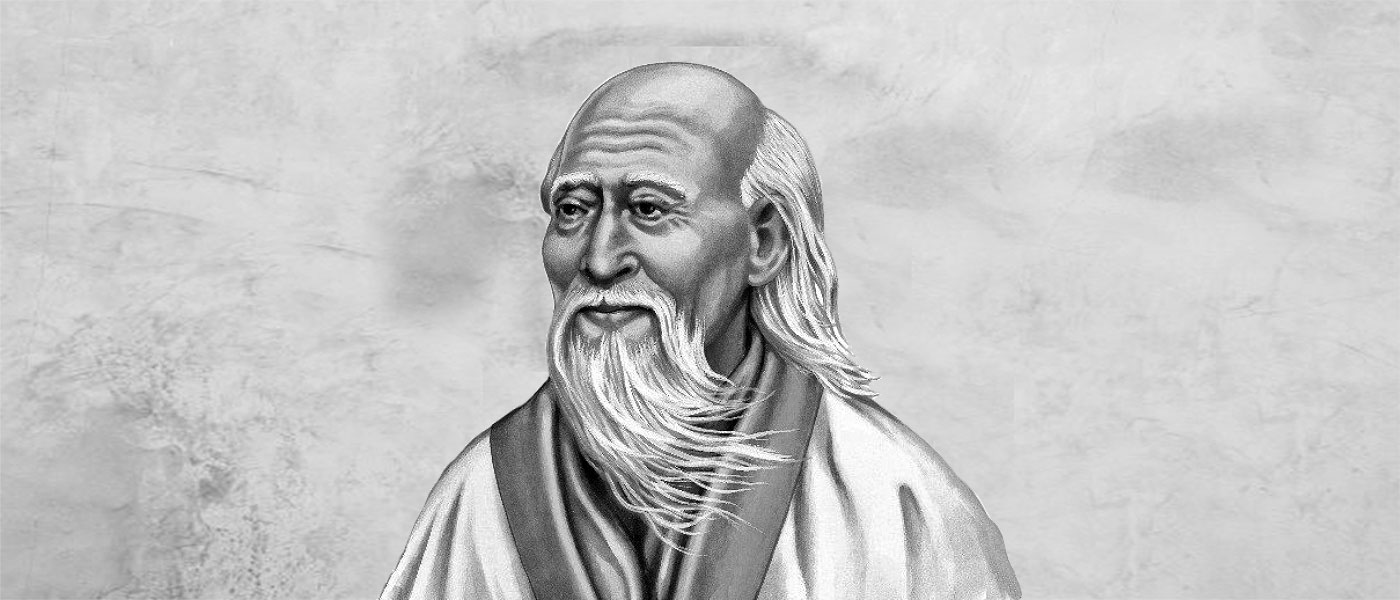

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Elisabeth Shaw 23 NOV 2018

If the problem isn’t in your head or before your eyes, check your ethics.

Ethical decision making isn’t always easy. It can cause stress, anxiety and conflict. Elisabeth Shaw helps ease the tension.

We tend to see human suffering as having two separate branches: psychological and physical. Life events like loss, abuse, disasters or health issues blend the two together, but rarely do we consider including a third. Ethical.

Rita and her two sisters were grieving their mother’s death. Rita had been named as executor.

Over the last few months, Rita had been researching her family tree. She talked with her mother about her memories. Rita learned her mother had a boyfriend she left when she chose her father, and that she deeply regretted her decision.

In my experience as a team leader for Ethi-call, a helpline for people working through ethical conflicts and dilemmas, I commonly hear of peoples’ worry, anxiety and internal conflict about the decisions at hand. People who are anxious tend to ruminate, become preoccupied, sometimes withdraw from social supports and can have disrupted sleep. This can further compromise good decision making.

Research on emotions and ethical decision-making consistently notes the importance of fostering greater emotional capacity and skill. People who are stressed, tired or emotionally conflicted may find the requirement to make quick yet effective and sound decisions more challenging.

A couple of weeks before she died she confessed to Rita she had a son to that man. He had been offered for adoption – a decision that affected her whole life. Rita located the son through an online search.

But emotional maturity is a life-long project. When we are faced with an ethical decision, we have to act quickly and decisively. Sometimes the emotional capacity we need is not yet developed. What should we do?

We now understand unethical decision making tends to be more intuitive and automatic. By contrast, ethical decision making is rational, considered and deliberate. You may not be aware of the ethical dimension of your decision or that you’ve acted unethically – “it just seemed like the thing to do”.

She told her sisters, as Rita believed her mother would want her to find him and include him in the Will distribution. But her siblings were horrified at her proposal. “It’s him or us!” they said.

Stressed people often isolate themselves, making decisions based on anxiety, urgency and reactivity. Isolation is a major issue. Our desire to get rid of a burdensome problem can spur us to act quickly, without taking adequate time for reflection. We are also limited by our own imaginations and life experience.

Rita was torn in her loyalty to her mother, her commitment to family and her siblings. All options seemed flawed and her grief was compounding her distress.

Comparing notes with others can help us see more possibilities and calm ourselves enough to proceed effectively. At the same time, consulting too many people – or worse, the wrong people – can be equally distressing. Hearing conflicting, dogmatic opinions can be stressful as we worry about being judged negatively for declining to act on someone else’s advice.

What we’ve learned from our callers is that they want a pressure-free, neutral and objective space to explore their concerns. Without the bias of colleagues or close friends and the pressure of fast decision making, people can often find their own wisdom and create a reasonable and effective plan of action.

Ethi-call is one way to discover such a space, but it isn’t the only option. We can unlock our own ethical resources by reaching out to wise friends or mentors, allowing adequate time for reflection without being rushed or by challenging ourselves to think more creatively.

Rita thought she had to make a definite decision but she had more work to do before she could. Time was on her side – the probate process can be a long period and lots happened in her family in a short period.

Ethical issues are not always neatly resolved. They need to be deconstructed and disentangled, and achieving room to breathe and think is quite a lot in itself. Sorting out all the different influences, options and relationships takes time and careful thought. But taking care to find a framework to progress the decision, to come to a values driven plan and then live peacefully with one’s decision is work worth doing.

Was Rita leaping to conclusions about her mother’s wishes? Did her brother want to be part of the family at all? With time Rita was able to determine how she felt and how to act. What she ended up doing doesn’t matter. What matters is the way she reached her decision.

Are you currently dealing with an ethical dilemma? A conversation with an objective, independent person can really help. Book a free call with Ethi-call, our confidential ethics helpline.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

BY Elisabeth Shaw

Elisabeth Shaw is a clinical and counselling psychologist, CEO of Relationships Australia and Senior Consultant at The Ethics Centre.

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 NOV 2018

Being tied in a knot of lies, the danger of scepticism, micro-dosing LSD and dismantling bi-partisan politics were just some of the themes threaded throughout this year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

Thousands crossed the threshold into the Festival’s new home on Cockatoo Island. Two days, 31 sessions, and 45 speakers later, they left with a feast of ideas and new perspectives.

For the first time, the island’s unique location and new full-day festival pass meant that you could delve deeper into FODI than ever before.

Caliphate host Rukmini Callimachi shared aching stories of violence and honour in ISIS camps; conservative historian Niall Ferguson forced us all to rethink before we retweet; and pop-culture savant Chuck Klosterman had us empathising with the unlucky aliens who colonise us.

“Hard truths, fleshy realities, blunt edged disagreement and sharp new ideas – all mixed together with a throng of people in an iconic location that spoke alongside the artists and speakers. It was a brilliant amalgam, FODI at its best,” said Dr Simon Longstaff, co-founder, co-curator, and executive director of The Ethics Centre.

For the first time, the island’s unique location and new full-day festival pass format allowed FODI-goers to attend a number of the 31 sessions and delve deeper into different topics and viewpoints while enjoying talks and panels, art installations, ethics workshops and even a touch of cabaret!

Even the master-of-all-trades, Stephen Fry, couldn’t avoid the glamour. A standing ovation roared through Sydney’s Town Hall for his delivery of the inaugural keynote, The Hitch. In honour of his dear friend, the late Christopher Hitchens, Fry had the sold-out venue in oscillating between stitches of laugher and solemn agreement when he lamented the lost art of disagreement in an age of deepening extremes.

Thinkers from around the globe tackled issues of truth, trust and technological disruption, including Caliphate podcast host and New York Times ISIS foreign correspondent Rukmini Callimachi, British conservative commentator Niall Ferguson, AI man-of-the-moment Professor Toby Walsh, and pop-culture savant Chuck Klosterman.

The sold out festival drew crowds of over 16,500 seats across the weekend, with #FODI trending across social media channels all weekend.

The Centre is enormously proud of this festival which we started a decade ago to provide a space to talk about the issues that divide and baffle us without tearing tearing ourselves and each other apart. And we’re thrilled it’s been a continued success in 2018 with a fantastic new partner, The University of New South Wales Centre for Ideas, and a fitting new home.

If you weren’t able to join us, many of our sessions were recorded and we’ll be releasing them over the coming weeks and months.

We’ll keep you posted in our enews or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn for more release updates.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Corporate whistleblowing: Balancing moral courage with moral responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

From capitalism to communism, explained

From capitalism to communism, explained

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 NOV 2018

Everything, from your clothes to your phone to the train you last caught, has gone through what economists call ‘the means of production’.

This is the way a commercial good or service is created and sold, all the way from its raw materials to how it arrives in your hands… or to your platform.

Most of these things (also referred to as capital) can only be created as a result of collective effort. No individual can reliably ensure everyone in a country of twenty-five million has a safe way to dispose of their waste or a place to go to when they’re sick. One person can’t even meet the most basic requirement of that population and ensure sure everyone is fed.

Of course, these things cost money to maintain. Whenever cost is involved, people want to know who pays. This is where it gets hairy. If one person owns ‘the means of production’, they have to pay for everything – and keep any and all profit made. If everyone involved owns ‘the means of production’ collectively, they share the cost – and any profit.

This is where the branches of different economic systems begin.

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic systemwhere the ‘means of production’ and resulting capital are owned by private individuals and businesses. It is based on voluntary relationships of supply and demand instead of centralised (usually government) planning.

This system is rooted in classical liberal philosophy and its conception of the rational, freethinking, autonomous individual. It claims market competition forces people to act in a way that benefits others, regardless of their intention.

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system borne out of opposition to capitalism where the ‘means of production’ are collectively owned and shared. It prioritises production for use rather than profit and achieves this through centralised planning – like a government.

The value of whatever is produced is determined by the amount of time and labour required, not market supply and demand. Socialism claims sharing resources and work according to need, rather than competition, creates a more equitable and secure society.

Communism

Communism is a utopian political economic system where a society is reorganised without hierarchy, states, money or class. The ‘means of production’ are shared communally and private property is non-existent or severely restricted. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the seminal political pamphlet on this, A Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Communism’s modern adherents claim it has not happened yet, while its critics cite Maoist China, Stalin’s Soviet Union, the Cold War, and many other historical crises to signal its danger.

Fascism

Fascism is an economic system based on self-sufficiency of the state, ethnic purity, and one-party ownership over the means of production. There’s usually a dictatorial leader and little to no tolerance of political opposition. Fascism claims the strength of a nation comes from unity and unity depends on fixed identities.

Though commonly associated with Nazi Germany, many other countries have been considered fascist at some point too, such as Brazil, Iraq and Japan.

Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire translates to ‘leave alone’ or ‘let them do’. Laissez-faire is an economic system that leaves transactions and trade free from government regulation, subsidies, tariffs, and privileges. It claims the economy is a natural system and the market is an organic part of it. Government interference hinders something nature can mediate.

Which economic-political system is best?

When discussing what economic system we prefer, it’s important to know what we’re talking about. The economies of most modern countries today are rarely pure capitalism or pure socialism. Most have a mixed capitalist system where private individuals or businesses make profit off labour, while operating within government regulations.

At the bare bones of economic theory, you find philosophy. Questions like ‘What is the purpose of government?’, ‘What is a human right?’, ‘What can we expect from our relationships?’, or ‘What does equality and justice look like?’ inform the different perspectives that manifest into policy.

Which one would you stand for?

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 NOV 2018

Your child is getting married. A mixture of pride, grief and trepidation have been gathering steam for a while now.

You don’t know how you’re going to feel on the day, but when you see your child go through one of the most ubiquitous rites of passage there is, you can’t guarantee there won’t be tears of love.

Except for one snag.

You don’t like their fiancé.

It’s heartbreaking. What should have been a moment of elation at your child’s joy is soured. You don’t understand why they’re making such a huge commitment to their partner or how you will live with that choice.

Perhaps you don’t think they’re good enough, or you don’t get along with them as much as you’d like. Maybe you see them bringing unhappiness into your child’s life – now or in the future. They might have strange attitudes to parenting or relationships. They might seem plain dangerous. Either way, there’s one question you’re asking…

What should you do?

In this situation, consider what a good parent looks like. Do they support, protect, and nurture their child? Do they allow them to make their own mistakes? Are they honest and fair?

Being honest may mean causing great hurt. Being fair may mean accepting the consequences of your child’s independence. Protecting your child may mean treating your fears as truth. But to what end? And by what means?

Wedding dilemmas splitting you in two? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you see through chiffon to make decisions you can live by.

On one hand, what actions present you as the person you want to be? Are they the actions of someone courageous, patient, and wise? Or someone petty, panicky, and controlling?

On the other hand, what actions risk damaging the relationship between you and your child? Or your future child-in-law? What situation necessitates speaking up? Or more drastic measures?

If you decide your concerns aren’t that serious, is there a way you could use this situation to build a stronger relationship with your child and a better understanding of the partner they love?

A lot of the time, when we are faced with an ethical dilemma, we see in binaries. Black or white, either or. Taking the time to slow down our thinking and consider the situation in different ways can help new pathways emerge – even if that means stepping back and living with the decisions another person has made.

So, before you end up expressing your reservations in panic, blame, and threats to boycott the wedding, take a breath. Step back, contemplate who you aspire to be as parent, what actions you feel are right and available to you and get creative.

If you or someone you know is experiencing violence and need help or support, please contact 1800RESPECT. Call 000 for Police and Ambulance help if you are in immediate danger.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The danger of a single view

There are times in the history of every nation when its character is tested and defined. Too often it happens with war, natural disasters or economic collapse. Then the shouting gets our attention.

But there are also our quieter moments – the ones that reveal solid truths about who we are and what we stand for. We are in one of those moments right now.

How should we recognise Indigenous Australians? Can our economy be repaired in an even-handed manner? How will we choose if forced to decide between China and the United States? How do we create safe ways for people seeking asylum? Can we grow our economy and protect our people and environments? These are just some of the questions we face.

And here’s another question. Do we have the capacity to talk about these things without tearing ourselves and each other apart? There are some safe places for open conversation about difficult questions. Twenty five years ago I began work at The Ethics Centre, a not-for-profit dedicated to creating such questions.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas is one such place. This weekend, 1400 Sydneysiders will gather at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas – in a brand new home on Cockatoo Island – to explore different views and perspectives on issues surrounding truth, trust and the battle of polarities in our society.

Why host a festival to explore dangerous ideas?

Sadly, there is a growing ‘fragility’ across Australian society. The demand for crystalline ideological purity (you’re completely ‘with us’ or ‘against us’) puts us at risk of a fractured and stuffy world of absolutes.

Too often, I see conversations shut down before they have even begun. People with a contrary point of view are faced with outrage, shouted down or silenced by others driven by the certainty of righteous indignation. In such a world, there is no nuance, no seeking to understand the grey areas or subtleties of argument.

“Attempts to prove to people that they are wrong just leads to stalemate. Barricades go up and each side lobs verbal ‘grenades’. There is another way. “

This phenomenon crosses the political spectrum – embracing ‘conservatives’ and ‘progressives’ alike. In my opinion, it is the product of a self-fulfilling fear that our society’s ‘ethical skin’ is too thin to survive the prick of controversy and debate. This is a poisonous belief that drains the life from a liberal democracy.

Fortunately, the antidote is easily at hand. In essence we need to spend less time trying to change other people’s minds and more in trying to understand their point of view – by taking them entirely seriously.

Why make this change? Because attempts to prove to people that they are wrong just leads to stalemate. Barricades go up and each side lobs verbal ‘grenades’. There is another way. We could allow people to work out what the boundaries are for their own beliefs. Working out the lines we cannot cross is often the first step towards others and can only happen constructively when people feel safe. Giving people the space to fall on just the right side of such lines can make a world of difference.

So I wonder, might we pause for a moment, climb down from our battle stations and call a cease-fire in the wars of ideas? Might we recognise the person on the other side of an issue may not be unprincipled? Perhaps they’re just differently principled. Can we see in the face of our ideological opponent another person of good will? What then might we discover about each other; what unites and what divides? What then might we understand about the issues that will define us as a people?

Let’s rediscover the art of difficult discussions in which success is measured in the combination of passion and respect. Let’s banish the bullies – even those who claim to be ‘well-intentioned’. They have no place in the conversations we now need to have.

Follow the #FODI conversation on Twitter, and keep an eye on our Instagram for on the ground action at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Scepticism is an attitude that treats every claim to truth as up for debate.

Religion, philosophy, science, history, psychology – generally, sceptics believe every source of knowledge has its limits, and it’s up to us to figure out what those are.

Sometimes confused with cynicism, a general suspicion of people and their motives, ethical scepticism is about questioning if something is right just because others say it is. If not, what will make it so?

Scepticism has played a crucial role in refining our basic understandings of ourselves and the world we live in. It is behind how we know everything is made of atoms, time isn’t linear, and that since Earth is a sphere, it’s quicker for planes to fly towards either pole instead of in a straight line.

Ancient ideas

In Ancient Greece, some sceptics went so far as to argue since nothing can claim truth it’s best to suspend judgement as long as possible. This enjoyed a revival in 17th century Europe, prompting one of the Western canon’s most famous philosophers, René Descartes, to mount a forceful critique. But before doing so, he wanted to argue for scepticism in as holistic a fashion as possible.

Descartes wanted to prove certain truths were innate and could not be contested. To do so, he started to pick out every claim to truth he could think of – including how we see the world – and challenge it.

For Descartes, perception was unreliable. You might think the world around you is real because you can experience it through your senses, but how do you know you’re not dreaming? After all, dreams certainly feel real when you’re in them. For a little modern twist, who’s to say you’re not a brain in a vat connected up to a supercomputer, living in a virtual reality uploaded into your buzzing synapses?

This line of thinking led Descartes to question his own existence. In the midst of a deeply valuable intellectual freak out, he eventually came to realise an irrefutable claim – his doubting proved he was thinking. From here, he deduced that ‘if I think’, then I exist.

“I think, therefore I am.”

It’s the quote you see plastered over t-shirts, mugs, and advertising for schools and universities. In Latin it reads, “Cogito ergo sum”.

Through a process of elimination, Descartes created a system of verifying truth claims through deduction and logic. He promoted this and quiet reflection as a way of living and came to be known as a rationalist.

The arrival of the empiricist

In the 18th century, a powerful case was made against rationalism by David Hume, an empiricist. Hume was sceptical of logical deduction’s ability to direct how people live and see the world. According to Hume, all claims to truth arise from experiences, custom and habit – not reason.

If we followed Descartes’ argument to its conclusion and assessed every single claim to truth logically, we wouldn’t be able to function. Navigating throughout the world requires a degree of trust based on past experiences. We don’t know for sure that the ground beneath us will stay solid. But considering it generally does, we trust (through inductive reasoning) that it will stay that way.

Hume argued memories and “passions” always, eventually, overrule reason. We are not what we think, but what we experience.

Perhaps you don’t question the nature of existence at the level of Descartes, but on some level, we are all sceptics. Scepticism is how we figure out who to confide in, what our triggers are, or if the next wellness fad is worth trying out. Acknowledging how powerful our habits and emotions are is key to recognising when we’re tempted to overlook the facts in favour of how something makes us feel.

But part of being a sceptic is knowing what argument will convince you. Otherwise, it can be tempting to reduce every claim to truth as a challenge to your personal autonomy.

Scepticism, in its best form, has opened up mind-boggling ways of thinking about ourselves and the world around us. Using it to be combative is a shortsighted and corrosive way to undermine the difficult task of living a well examined life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Double-Effect Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 5 OCT 2018

We sat down with Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018 festival director Danielle Harvey to take peak into the inspirations, motivations and challenges behind creating one of the most confronting and thought-provoking events in Australia.

1. It’s been said FODI was Australia’s first disruptive festival. What is it about the festival that resonates so strongly with audiences?

People want more than a headline. They want to hear more in depth analysis and a range of perspectives. To hear straight from the academics, scientists, researchers and not have it filtered, distorted. A live festival doesn’t get more direct.

2. There are so many different ideas, themes and perspectives out there that matter. How do you narrow it down to land this year’s line up?

A lot of vigorous discussion! Myself and the co-curators are always looking at the next thing that’s going to hit, we’ve been very good at looking at the horizon in past festivals, discussing things like Russia, surrogacy and banking all before a scandal breaks.

We also look to the superstars of the non-fiction world, the academics and researchers doing great work and are great communicators. And we look for a multitude of perspectives, beyond politics. A discussion that involves people from across disciplines, experts in their field that bring to light a focus on a particular aspect and when combined help to show the complex nature of many of our biggest ideas and problems.

3. The festival has been going strong for 9 years now. What gets easier, what doesn’t?

This is my 7th FODI. I feel very lucky to have been able to grow my own understanding of the world in a very public way! The easier and harder is the same – finding great people.

Easier because people around the world know about this festival and we have great alumni and reputation, harder because we’ve presented so many amazing people and so many ideas… I look forward to next year… 10 feels like a good ‘best of’ opportunity!

4. What does it take to be a great festival director?

Curiosity about the world. I’ve curated and created a number of festivals – FODI, Antidote, All About Women, BingeFest and Mardi Gras and they always start about thinking about audiences and what they should be able to see/hear/experience. I am insatiably curious and I love finding connections between things.

5. What’s it like to produce a festival like FODI? What does a typical day look like for you?

Talking. Talking. Appreciating the amazing team around me. (I have the best people who do so much). More talking. Noodling on the internet, reading, watching. Talking some more. (I talk to people from all different walks of life to hear what is interesting them).

6. What do you think sets the 2018 festival apart from recent years?

The island! The opportunity to fully immerse yourself in a program sans distractions. It’s all about the ideas and engaging with them deeply this year. The opportunity to include more large scale art and theatre has also made this a very different festival. We have the space and time to do these things on Cockatoo.

7. Why the move to Cockatoo Island and what are the challenges or surprises in setting up a festival in the middle of Sydney Harbour?

Everything has to be barged on! That’s the biggest challenge. It’s an amazing site, full of potential, but it is an island with no real infrastructure. The history of the place is incredibly evocative and any time we go there we are amazed at this little gem sitting on our doorstep. It’s a great place to let your mind and feet wander (and wonder)!

8. Finally, we have to ask. Which bit are you most to looking forward to? What are the must-see events?

That is tough, it will all be great! I am really looking forward to Chuck Klosterman, to Rukmini Callimachi and of course Stephen Fry! I think the ‘Too Dangerous’ panel will also be full of excellent take-aways.

I am also excited about the two art installations – ‘Submission’ and ‘The Hand That Wields It’ these installations are excellent opportunities to see ideas represented in a different way rather than via a talk.

Everything you need to know: The Festival Of Dangerous Ideas 2018

From sex robots to sex clowns, to tying yourself up in lies and rope, this year’s festival on 3 – 4 November takes you beyond the hype and deep into the issues that confront and divide us.

Embrace the festival experience on Cockatoo Island with one-day or full weekend passes. All passes include free return ferry transport.

Featured speakers include ex Westboro Baptist Church follower Megan Phelps-Roper, conservative historian Niall Ferguson; iconoclast Germaine Greer; rock star of AI Toby Walsh; micro-dosing advocate Ayelet Waldman; pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman; academic and activist Mick Dodson and so many more!

To crown FODI 2018, join Stephen Fry at a special event at Sydney Town Hall, where he will deliver an oration on the lost art of fabulous disagreement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Big thinker

Relationships

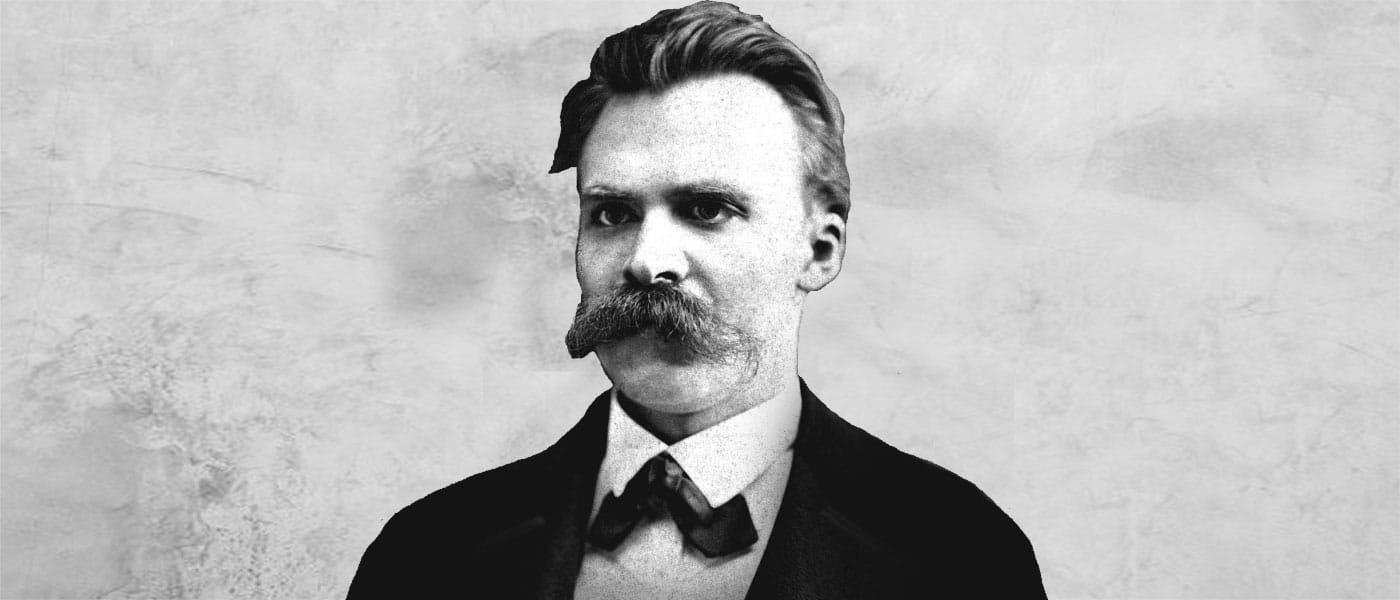

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2018

The Ethics Centre (TEC) is thrilled to be announced as a finalist for Training and Education Business of the year in the Optus My Business Awards for the second year running.

It’s an honour to be a finalist again after we were awarded winner of the category last year for our Ethical Professional Program.

The inaugural Optus My Business Award program reported record submission numbers this year, with leading SME’s across Australia vying for recognition in the 35 prestigious award categories.

This year we are proud to be finalists for our Ethi-call Counsellor Training Program (ECTP), completed by individuals hoping to become a volunteer Ethi-call Counsellor.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to anyone needing help to make their way through tough ethical challenges in their life. Made possible only through the support of volunteers who provide this service, this year we increased our capacity to deliver sessions by 300% through the ECTP program.

The eighteen-month program blends a diverse mix of learning techniques, resources and support networks to prepare students both emotionally and technically to handle the diverse range of calls received by the Ethi-call helpline.

Through an integrated learning program that bridges theoretical ethics with empathic counselling skills and practical delivery of the Ethi-call model, students are supported to develop the skills and understanding to develop as counsellors.

When asked what makes the ECTP so special, a recent graduate remarked:

“[TEC] Invest a great deal in this new Ethics Counselling Training Program to ensure callers to the Ethi-call service – who usually have extremely complex and often upsetting moral dilemmas in their personal and professional lives – receive the absolute best quality of service possible”

Program Manager Peta Andreone explained:

“Our duty is to ensure counsellors are capable to handle any type of call, and that our callers not only have access to a freely available service, but one that delivers the highest standard of care”

“Counsellors undergo intensive training to be registered through TEC, and participate in ongoing professional development to maintain their credentials annually”

The key innovation to the Ethi-call Counsellor Training Program is the Ethi-call Counselling Model, a working tool that has been developed and refined over the past 27 years.

An independent panel of judges will now review finalist submissions before deciding on this year’s awarded entries. Winners will be announced at a black-tie gala dinner on Friday, 9 November at The Star in Sydney.

Congratulations and good-luck to our fellow finalists in the Training and Education Business of the Year:

Code Camp

Engage & Grow

First Home Buyer Buddy

KICKBrick

Liberate eLearning

PD Training

STEM Punks

TCP Training

The Financial Fox

If you would like to train as an Ethi-call counsellor, send an expression of interested to counselling@ethics.org.au.

If you are facing a difficult ethical dilemma or decision, make a free appointment for a private conversation with an Ethi-call counsellor here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights