Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 12 FEB 2025

Many of us know how easy it is for our New Year resolutions to fail. And that’s ok, we’re only human. But how do we bring about change, if we want to?

For many people, the start of a new year is a time to make resolutions. For others, it’s a time to reflect on how to make the world a little better by becoming a little better as a person.

Unfortunately, for the majority of people, our commitment to change often fails and the gap between our intentions and actions can feel insurmountable. The Ethics Centre’s Director of Innovation and Education, John Neil says this is because, well, we’re human beings. He offers at least three factors behind this:

- We overestimate the power of ‘willpower.’ Often linked to adjacent concepts like resilience and impulse inhibition, the long-standing belief in psychology is that willpower is a finite resource and people have varying reservoirs of it to draw on. The belief was that by bolstering our willpower we’re better able to attain our goals and those that don’t achieve their goals lack willpower. Unfortunately, it’s more complicated than that. Our ability to maintain choices and attain goals is as much about situational context, genetics, and socioeconomic standing as it is about individual psychological traits.

- As a result, any significant behaviour change requires long-standing practice, environmental changes and thoughtfully designed behavioural cues to create pathways of reinforcement to form new habits. In short, even the simplest resolutions require habitual practice.

- Most resolutions are goal-focused – stop smoking, lose weight – so they take on instrumental importance, meaning they focus exclusively on achieving an end state or outcome. With the high difficulty in achieving these outcomes resolutions can become self-defeating – the end becomes the goal rather than a focus on the motivating reason that inspired the goal.

That’s not to say that resolutions are a bad thing. We are hard-wired to demarcate life into phases. Birthdays, seasons, events, and the change of year are all relatively arbitrary events but are full of symbolic significance. They are moments that matter because we invest these occasions with meaning. They can provide a much-needed pause in the busy and difficult aspects of life to reflect and reassess what’s important to us.

So, how can we reset to focus on what we want more of in our lives?

The Ethics Centre has developed Ethics Reboot, a new, free, online 21-day challenge designed to create better habits.

Rather than feeling the pressure to write down a long list of goals, that have little chance of sticking, the course asks you to think instead about the qualities you’d like to cultivate. What qualities for you express the best aspects of a life well lived? Which of those would you choose to have more of in your life?

Some philosophers refer to these qualities as virtues – those behaviours, skills or mindsets that are worthy to be regarded as features of living a good life. Wisdom, justice, and courage were on Aristotle’s shortlist.

Rather than setting goals like reading more books or spending less time on my phone – think instead of the quality you are calling more of into your world – like being curious, courageous or compassionate.

Ethics Reboot provides you with one new quality or virtue to focus on each day for 21 days. Each daily challenge will give you guidance, motivation and inspiration to bring that quality into your every day.

In the midst of busy lives – and an increasingly tumultuous world – the challenge of the course is to carve out a few minutes each day to learn something new, put it into practice and reflect on it’s impact in your life. The result? Creating a new habit of daily self-reflection that might just help kick-start new ways of thinking, being and doing life that little bit better.

The course kicks off from when you sign up and lasts for 21 days – just enough time to develop some fresh new habits. You can join by signing up on our website.

Each day you’ll receive:

- A daily email explainer introducing you to a new virtue

- A guided activity to help practice what you’ve learnt

- A reflection exercise to build your ethical muscle and integrate the virtue into your everyday

In a time where many aspects of life can feel tough, focus on what you can control. And you might just see that resolution through.

Take our 21-day challenge and sign up for Ethics Reboot here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How can we travel more ethically?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The right to connect

The right to connect

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran 28 JAN 2025

Gen Zs are terrifying: we are the wizards of the digital world that is increasingly alien to the older generations.

We are hooked up by the veins to the ever flowing current of information and all of its chaos and simulacra, often seen as being emblematic of technology gone too far; escapists subsumed to a Matrix-like existence.

The other terrifying thing about us: we’re all mentally ill, apparently. So much so that Jonathan Haidt released a book about us called “The Anxious Generation”, expanding on the most popular explanation for rising mental illness in youth: the infamous ‘phone bad’ argument.

This claim has undeniable legitimacy: studies correlate social media usage with mental illness, including rising self-harm ER admissions for American teenage girls. There is no world in which a teen scrolling TikTok in their bed after a long day at school can defend their attention from a trillion-dollar organisation of world-class optimisers. Our generational psyche has been crafted into a consumer mind by a minority of technocrats.

In short, our generation has been raised into addiction. Understandably, this problem is now starting to drive policy, underlying a social media blanket ban for youth, as is being proposed by the Australian government.

I don’t think I would miss social media necessarily. But when I entertain what it would look like to close the portal to that void world, I do wonder: what then would I build on that empty plot?

My addict attention-span, whittled down to the duration of a good reel, attempts to ground itself firmly into the real world: OK, I’ve wasted so much time. I should focus on work — earning money. Money for what? Perpetual rent, until I can double my salary to buy a house. A house for what? My future family. But it feels unfair to have kids in this future, anticipating worsening climate disaster. Can I even manage a family when I can barely manage my own life? Or, well, this is kind of exhausting… I should relax… I’ll just quickly check Instagram to see if my friend sent something funny…

The checking is an itch. I scratch it compulsively when distracted, anxious, bored, or depressed, thereby gaining short-term relief. But like other types of addiction, while the object of addiction makes it worse, it is not the same as the source. Psychiatrist Gabor Mate’s mantra is: “Don’t ask why the addiction, ask why the pain.”

Perhaps my train of thought seems overly catastrophic — the kind of hysteria to be expected from the ‘anxious generation’. But the content of these anxieties driving addiction has real, material legitimacy, and they are not arbitrary. A home, a community, and a safe climate: these are frequently cited themes driving Gen Z’s anxieties.

They are recurring themes because they are how we connect to the outside world. Johann Hari wrote that the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety: it’s connection. A physical home is the cradle of our connection to a place; a safe base. A community and friends who know and care for us is our connection to people, allowing us to develop fluid and dynamic social identities. A safe climate represents the connection to any foundational future; a promise that our actions today are and will continue to be meaningful. Therefore, these basics are also our critical defences against addiction — or more precisely, they are the salve for the part of us that is drawn to the escape it offers.

When basic needs for connection have become unattainable fantasies, it is less mysterious why mental illness in youth may not be easily solved by unplugging.

Home ownership is a pipe dream rather than a mundane right in an absurdly land-rich city like Sydney. Neoliberal market logic reigns supreme over the provision of basic needs, treating houses as a class of speculative investment assets over functional shelter. Alan Kohler notes house prices have increased from four to eight times annual income in one generation. This is not just an aberrant property of Australia, but a global crisis as pointed out by the World Economic Forum.

This alienation is worsened by looming climate disasters which can uproot entire homes, as it does so for many people in rural communities and the global south, with its reach to the rest of the world only being a matter of time. Yet while three-quarters of Australians aged 18-29 believe climate change is a pressing problem, only ~50% of Australians aged over 50 do.

The epidemic of loneliness is also a global epidemic, according to the World Health Organisation. The average person has fewer and fewer friends, with Gen Zs feeling more lonely than other generations, including those aged 65 and over. On the flipside, young people increasingly engage in unsatisfying forms of intimacy like non-committal relationships (situationships) and AI personas such as Character.AI — forms of commoditised connection which, similar to social media, are exacerbating symptoms of disconnection rather than drivers.

There is a clear inequality in the opportunities to build physical, social and lasting connections between young people now and the older generations who also comprise most positions of power. Without recognising this structural unfairness, it is too easy to imagine mental illness as a linear consequence of technology, which incidentally has the unfortunate side effect of hysterical social complaints.

But our ‘hysteria’ is Janus-faced: yes, young people may be ungrounded, overstimulated and sensitive — but we are also flexible, intensely curious, and sensitive. Behind our grief is a quiet hope that needs to be understood and nurtured — never belittled. It is correct but incomplete to say that our generation is overly anxious and negative: many Gen Zs often through social media write letters to MPs, courageously reaching for environmental justice. When understood and armed with the right tools for connection and change, our sensitivity is a source of strength.

Fixing ‘phone bad’ with a blanket ban will not fix the root causes of mental illness, particularly for a generation with so few existing tools for coping and connection. Experts on digital media fear that a social media ban will further isolate already-isolated youth, and with social media being a nexus for youth activism, it will only serve to silence youth voices further. Practically speaking, this legislation has also failed to work in other countries. Fundamentally, the escapism of the digital world is driven by the hostility of the real world towards youth.

What the older generations owe us, then, is to form solutions that sincerely integrate the experiences of youth to treat the structural sources of illness: the lack of Gen Z’s physical security, social connection and a future. Technology should be regulated through a framework of harm reduction, recognising its role as an object of addiction.

Lastly, they should recognise that our visible vulnerability is not the sole problem but reflective of the system’s failures; in the age of climate collapse, we are canaries in a coal mine. That does not make us weak, but protectors of what is soft. And if we are no longer willing to create structures to protect the soft, then what, exactly, do we create our society for?

This is one of the Highly Commended essays in our 2025 Young Writers’ Competition over 18s category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

HSC exams matter – but not for the reasons you think

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran

Marlene Jo Baquiran is a writer and activist from Western Sydney (Dharug land), Australia. Her writing focuses on culture, politics and climate, and is also featured in the book 'On This Ground: Best Australian Nature Writing'. She has worked on various climate technologies and currently runs the grassroots group 'Climate Writers' (Instagram: @climatewriters), which won the Edna Ryan Award for Community Activism.

How to live a good life

What do you need to flourish in life? Philosophy and science suggest there are six key ingredients.

How do you decide where to live, what work to do, what kinds of relationships to cultivate and generally what kind of life to live? These are some of the most important questions we can ask, and the answers we arrive at can have profound impacts on whether we end up flourishing or miserable.

At the heart of these decisions is some implicit idea of what a good life looks like. But which picture should guide our actions? There is no shortage of voices selling us a range of visions of a good life, including our family, the media, pop culture, our workplace and, of course, advertising. We might hear that we should pursue wealth, status, success, comfort, happiness, etc., but philosophers and scientists have shown that these goals don’t necessarily lead to a better life.

So how should you guide the big decisions in your life? Here are six pillars that make up a good life.

Wisdom

Socrates famously said “the unexamined life is not worth living”. This relates to what we call wisdom. It’s a precondition that enables us to understand what a good life is, as well as gain knowledge about ourselves, what makes us tick and what causes our suffering.

Gaining wisdom is a life-long pursuit that requires a healthy dose of what we call ‘loving self-scepticism,’ because we are so good at fooling ourselves into taking the easy option rather than one that will be genuinely rewarding.

You can start cultivating wisdom by engaging in mindful behaviour, where you focus on being aware of your own internal state as well as what’s around you, rather than just running on auto-pilot all the time. You can deepen this by practicing meditation, but that’s not a requirement. Simply acknowledging what’s happening, and then taking time to reflect on it with a critical eye and an open mind can help you to better understand yourself and the world around you.

Purpose

Purpose means pursuing meaningful goals. Of course, many of the goals we pursue are imposed on us, whether that’s due to life’s necessities or because of our responsibilities. But we can also create goals for ourselves, and these often guide our big decisions, such as what career to pursue or whether to become a parent.

The key is pursuing meaningful goals that connect with our intrinsic aspirations rather than just pursuing things that seem important, like money or status, but that don’t actually help us flourish. An intrinsic aspiration is something that you find meaningful in its own right, and these are often activities that don’t just benefit ourselves, but have a positive impact on the world and other people. This could be through the work you do, helping other people in need or bettering your environment, or it could be through the time you spend caring for your family. There is abundant evidence that people who toil to help others report greater life satisfaction, even if they receive less money and status than if they did an easier job.

Agency

Agency is connected to the work we do in the world – your ability to have a sense of control in your life and to attain and practice mastery in what you do.

We probably all know that feeling when we’re deep in a task, using and stretching our abilities, we’re fully present in the moment and lose all sense of time. That’s called a ‘flow’ state, and it’s an indication that you’re exercising your agency. The task itself might even be unimportant: perhaps you’re creating art or music that no-one else will ever see or hear, but it’s in the making that you experience your agency. Some people can connect purpose and agency, and strive for mastery while doing meaningful work – but that’s not required for a good life.

Intimacy

Intimacy speaks to our fundamentally social nature. This means more than just having a lot of friends, in the real or online worlds. Casual friends are fine, but what is truly nourishing is having at least a few close friends, the kind of people around whom we can be our authentic selves, express vulnerability safely, and feel like we are seen and understood while reciprocating back. This could be your partner, but you can also have intimate friends. You don’t need many intimate relationships like this to flourish. Even a handful can give help you live a good life.

Of course, intimate friendships are not easy to cultivate, not least in the massively anonymous, technologically-mediated world many of us live in. One way to build meaningful friendships is to seek out people with similar values to you, whether that be through shared activities or just by keeping an eye out for people you admire and click with.

The trick is then to move from a superficial relationship into a closer one. While we often expect that we have to project our best, most confident and successful persona to the world, it’s actually when we lower the mask slightly, and reveal a bit of who’s underneath – including our uncertainties, anxieties and vulnerabilities – that we can build a deeper connection with someone, especially if they are willing to lower their mask in turn. We can do this by practicing what’s called escalating self-disclosure. This is about gradually lowering that mask and building trust and respect, which can then lead to a closer relationship.

Belonging

In addition to a few intimate friends, we also need to belong. This means that we feel like we’re a member of a social group that we care about, and that we’re seen, recognised and respected by other members of that group. This dimension of social life is often overlooked in modern society, which tends to promote atomic individualism, neglecting the importance of group identity.

We probably already belong to several different identity groups, whether that be connected to ethnicity, religion, local community or even our profession or a hobby. But cultivating a sense of belonging means more than just sharing some customs or activities, it means contributing something meaningful back to that community, and being proud of what your group represents – while also ensuring that belonging doesn’t slip into insularism or elitism.

Elevation

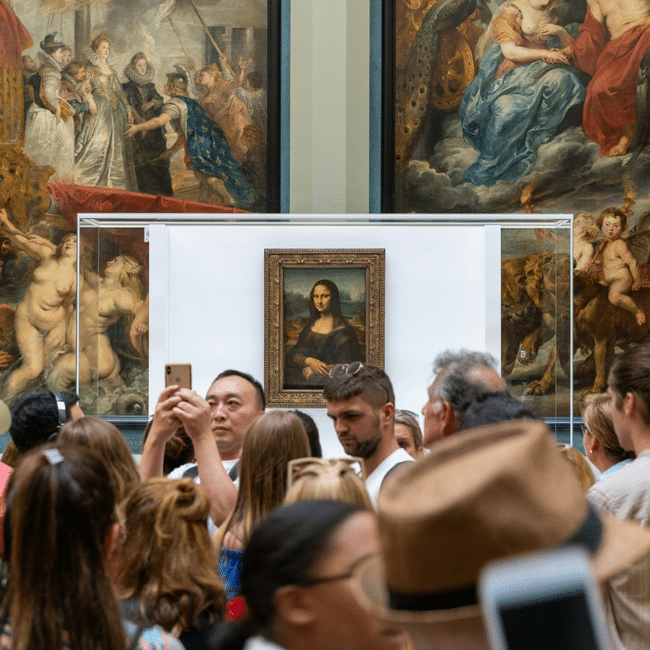

The final pillar of a good life is perhaps an odd one, but is no less important for many people. Elevation is captured in those experiences where we forget about ourselves, our problems, goals and anxieties for a moment, and we allow ourselves to sink into the background, focusing instead on the wonders of the world around us.

We can find elevation by spending time in nature or contemplating the vast stretches of space and time at an observatory or museum. We can find it by connecting with our ancestors by studying history or by walking through a cemetery. We find elevation by recognising the sacred is all around us, not just in religion, but in the rituals, objects and places that we hold dear. We can also experience elevation by acknowledging remarkable people around us, such as those who have performed great acts of kindness, compassion or self-sacrifice. Elevation reminds us that we are just a small part of a bigger system, and it helps us to escape our self-obsession and appreciate the world we live in.

Of course, there’s a lot more to each of these pillars, and different ones will resonate with different people based on your ability to choose how to live your life. But consider this guide to help you start the process of self-examination to discover what constitutes a good life for you.

Ethics Tune Up is an innovative and engaging masterclass series that will take your ethical skills to the next level. Our next series of workshops is running during May and June 2025. Book your tickets here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Academia’s wicked problem

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Being a little bit better can make a huge difference to our mental health

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Tough love makes welfare and drug dependency worse

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Monty Badami 1 NOV 2024

Jill Stark, recently wrote a controversial piece likening athlete Nedd Brockmann’s 1600km charity run to a broader trend of men “repackaging mental health as mental toughness”, where the “blokeification of mental fitness” is “just toxic masculinity rebranded”.

She has since apologised for the headline, acknowledging that it “was reductive and clumsy and failed to capture the complexity of the issue”. But she also received a lot of vitriolic abuse that proved the very things she was trying to call out.

Whilst it’s not new for men to engage in extreme acts to prove themselves, there has been an increase in shirtless men on social media, with rock-hard abs and beards, embarking on extreme ritualistic adventures to reclaim their manhood. Men are going to brutal boot camps to develop their physical wellbeing, mental toughness, and “find their tribe” through a spartan lifestyle, a navy seal mindset and howling at the moon. Beating drums, near-naked wrestling, the rejection of alcohol, drugs, technology, women and other worldly distractions are the homo-social privations in this cult of masculinity, where Jordan Peterson is regularly quoted, and Andrew Tate is tolerated, if not revered.

Whilst I won’t tar Nedd Brockman with the same brush, there’s something about how he’s been received that could be used as a gateway to the manosphere.

The “no pain no gain” movement in men’s mental health, and the performative tribalism that goes along with it, has worrying similarities to the humiliating initiation rituals of university colleges, the military and cults. But it’s not the first time men have desired the return to an idealised “natural”, “tough” and masculine past.

Paradoxically, the term “toxic masculinity” emerged from the mytho-poetic men’s movement of the 80s and 90s. It was an explicit response, by men, to feelings of powerlessness at a time when the feminist movement was challenging traditional male authority. It was an attempt to navigate the social pressures placed upon men to be violent, competitive, independent, and unfeeling.

But toxic masculinity doesn’t simply condemn all men or male attributes. It refers to the rigid and excessive policing of masculine norms, such as dominance, self-reliance, and competition, that are harmful to men, women, and society overall. And this is how the performance of alpha-male, lone-wolf, toughness can be toxic. But we must consider the intent.

Is the focus on toughness an act of self-interest to stroke the ego? Is it necessarily tied to masculinity, and used to dominate other men? Or is it a mechanism for self-understanding, self-growth and service to the community?

How is Brockman’s achievement different to Jessica Watson sailing around the world? Or Grace Tame competing in ultra marathons and processing her trauma? Or Darius Sam, from the Lower Nicola First Nation in Canada, who ran 100 miles to raise awareness around addiction and mental illness, and to grapple with how these issues affected his life?

As an officer in the Australian Army, my training challenged me mentally, physically and emotionally to develop resilience and moral courage. But this was not about glory. My ego actually got in the way when I faced those dark places within. Sitting with my emotions and transcending my ego became a source of profound growth and self-understanding. For Stoics like Aurelius and Epictetus, they taught that resilience comes from within, based on inner values rather than external displays of strength.

When we look cross-culturally, extreme rituals are not only about the promotion of self, or masculinity. Ritual theatre and performance is also a way to create intense social bonds and transcend the self, with adaptive and evolutionary benefits. We can even see this in the strong feelings of community experienced by both men and women who do ultramarathons or cross-fit.

But what troubles me in this discussion is the assumption that external challenges are inherently masculine and performative, and internal ones are somehow feminine and more authentic. It’s a false binary that ignores the fact that this is beyond gender. It ignores how external challenges facilitate the journey within.

But, why do we necessarily associate anger, aggression and competition with masculinity? Why do we associate empathy, nurturing and care with femininity?

I’m not competitive or aggressive. In our home I’m seen as more empathetic. My wife is the opposite. She’s more decisive, and doesn’t like talking about her feelings. Does this make her less of a woman and me less of a man? Of course not. What’s more, we both possess all the qualities listed above, just in different measures.

Essentialist concepts of masculinity ignore the fact that there are many ways to be a man. Whether you define masculinity in “traditional” or “alternative” terms, you are still constraining it, and that can make it toxic.

And so, we need to interrogate the very definition of masculinity itself, so we can safely explore our sex and gender, and find healthy versions of what it means to be human in all its brilliant complexity.

We’re all at different stages of personal growth, so perhaps the answer is not simply “news-jacking” Nedd Brockman, stopping ultra-marathons or ice-baths, and lumping them in the same bucket as toxic “raw-dogging” masculinity. Perhaps the answer is the very thing we want those alpha-males to embody? Perhaps the answer is empathy and compassion?

Rather than pushing these men away, Mike Dyson, founder of The Good Blokes Co, an organisation that runs Healthy Masculinity Retreats, says:

“A lot of men think the conversation about masculinity is negative and dominated by women, so they are disengaging. Nothing is going to change if men are not having this conversation too.”

“We’re seeing a desire of men to explore toughness and resilience – and that’s because our culture of masculinity rewards the performances of toughness. So, we need to meet blokes where they are in order to take them to where they need to go.”

“Rigid masculinity is the thing that gets in the way of true resilience because it stops us talking about our emotions, so we have an opportunity and a responsibility to have a deeper conversation about this with the men in our communities”.

And perhaps that is precisely what Stark and Brockman are allowing us to do right now. We can actually draw men in with the language of mental toughness, and then open the conversation to include other things like service, humility, intimacy, emotional maturity, accountability, calling out your mates, and stopping gender-based violence. And this can be a really important thing to give young men as they navigate the internal and external challenges of what it means to be a man in the world today.

Further resources

Mental Health

Head to Health: https://www.headtohealth.gov.au/

Open Arms: https://www.openarms.gov.au/

Relationships Australia: https://relationships.org.au/

Talk2MeBro: https://www.talk2mebro.org.au/

Community Groups

The Man Walk: https://themanwalk.com.au/

Dads Group: https://www.dadsgroup.org/

Tough Guy Book Club: https://toughguybookclub.com/

Mens Shed: https://mensshed.org/

The Men’s Table: https://themenstable.org/

Immediate Support

Beyond Blue: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/

Men’s Line: https://mensline.org.au/

Lifeline: https://www.lifeline.org.au/

Studies and interactive resources

Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World: https://www.vivekmurthy.com/together-book

The Man Box Study: https://jss.org.au/programs/tmp-research/the-man-box/

The Good Blokes Co: https://www.goodblokes.co/

Healthy Male website: https://www.healthymale.org.au/mens-health-week-2023

For more, tune into the FODI24 panel discussion, Positive Masculinity:

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

BY Monty Badami

Dr Monty Badami is an Anthropologist and the Founder of Habitus, a social enterprise that gives you Lifehacks to be a Good Human! Monty combines evolutionary evidence with cross-cultural research to explain the secret to our adaptability and success as a species. He designs and delivers workshops that help people put more meaning and joy back into their lives.

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Tony Milligan Lena Springer 16 AUG 2024

Parenthood has traditionally been considered the normal outcome of growing up. A side effect of reaching maturity.

Across Europe and the US, only 10%-20% of adults remain childless or (more positively) child free. In some cases, this is accidental. People wait for an ideal time that never arrives – and then it is too late.

Anti-natalism is the philosophical view that it is ethically wrong to bring anyone else into being. The justifications draw upon worries about suffering and choice. And it’s not an exclusively modern attitude. The ancient Greek playwright Sophocles, writing at the end of the 5th century BC, tells us that it is “best of all” not to have been born, because life contains far more suffering than good.

Contemporary anti-natalist arguments add a nuance by focusing on an asymmetry between pain and its absence. The absence of all pain is good, but this good can only be achieved through not bringing anyone into existence at all. The presence of pain is bad, and it is always part of life. So why forego the certainty of a good thing for the certainty of many bad things?

Philosopher David Benatar presents the best known contemporary argument along these lines in his 2006 Sophocles-inspired book, Better Never to have Been:

“It is curious that while good people go to great lengths to spare their children from suffering, few of them seem to notice that the one (and only) guaranteed way to prevent all the suffering of their children is not to bring those children into existence in the first place.”

Other versions of anti-natalism focus instead upon the fact that nobody chooses to exist. Existence is thrust upon us. Inconveniently, this suggests that the vast number of teenagers who tell their parents: “I didn’t ask to be born”, may in fact be budding philosophers.

The problem with anti-natalism

Anti-natalist arguments can sound like something from Oscar Wilde, rather than practical guidance for life. This makes them difficult to challenge. However, one popular response is to say that a refutation is unnecessary.

Having children is part of the canvas on which ethics is painted, rather than part of the picture. The ethical picture can change, but the canvas is not optional. It holds our way of human life in place. Individuals can choose to procreate or not to procreate, but rejecting parenthood entirely has no place within a good society.

Critics find this response evasive. Many of us also wonder why humans are drawn toward parenthood and what we might be missing if we choose not to procreate. Schopenhauer answers the “why” question in The World as Will and Representation (1818) by claiming that biology overrides sound judgement and tricks us into producing the next generation.

But is it really a trick? After all, there do seem to be some important good things bound into parenthood.

The philosophical benefits of parenthood

Plato’s Lysis struggles to identify these good aspects of parental care. His central character, Socrates, gives some young men a hard time when they cannot identify what benefit they bring to their parents. What they fail to recognise is that the goods of parenthood involve seeing a child grow and mature – and finding meaning in the process.

This recognition of the role played by care for others is also present in many religious traditions – particularly in the ways that they address life’s sufferings.

Buddhists celebrate the rebirth of enlightened humans into a world of suffering in the hope that they may help other beings.

Confucians highlight that, across generations, children can care for parents and grandparents.

In both cases, care binds a good society together, in ways that sustain social hope. In contemporary social economy, the younger generation of taxpayers supports older generations as well as childcare.

While non-existence would avoid may bad things, new humans carry the possibility of making the future better than the past. Losing such hope for the future would be terrible all round.

Focusing instead on the lack of choice exercised by a nonexistent, unborn human generates interesting philosophical puzzles, but bypasses what runs philosophically deep. Such as the wonder that the female body is where the creation of all humans happens – the place where every pianist, pickpocket and anti-natalist starts out.

The female power to give birth also counteracts complex forms of sociocultural control and sets in motion practical problems: who will become family members of a new human? Will relatives and our wider society care in the right ways?

Women must make the final decision about giving or not giving birth. At the same time, to give life a sense of meaning, we share our lives with friends, life partners, and children. Disappointment, joy and loss are part of the package. Even Schopenhauer, who spurned parental love, felt the need to lavish care upon his beloved dog.

We can love and find meaning without having children. But parenthood is one of our more entrenched ways of trying to live meaningful lives. For some, there may be no other workable path. Personal histories can lead any of us to feel incomplete without children. More disturbingly, it can lead people to feel like failures if they remain childless. And that, surely, is a bad thing.

In a rare Sydney appearance, philosopher David Benatar presents The Case for Not Having Children at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Sunday 25 August, 2024. Tickets on sale now.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

BY Tony Milligan

Research Fellow in the Philosophy of Ethics, Cosmological Visionaries project, King's College London.

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Nina Hendy 9 APR 2024

Imagine what it must feel like not to receive compulsory superannuation – despite it being a mandated part of our employment landscape for more than three decades. For many Australian workers this is a reality.

The Super Guarantee legislates that employers have to pay super contributions of 11 per cent of an employee’s ordinary time earnings, regardless of whether they’re a casual or full time employee.

But the legislation that is meant to protect working rights falls short for an increasingly large group of workers.

We’re referring to the gig economy, which appeared out of nowhere around 2006 when Menulog launched Australia’s first online meal delivery service and has since grown nine-fold to employ as many as 250,000 workers across platforms such as Upwork, Fiverr, Uber and Airtasker.

While the system is providing Australians with flexibility, autonomy and options for an additional source of income, its participants are also being exploited. More than half of gig workers are under 35 and a similarly a large number are international students and migrants who can struggle to get a foothold onto the career ladder in Australia – sometimes due to language or cultural setbacks. It appears nearly two decades later, the super system appears to still be playing catch-up with a changing workforce.

Despite some contractors being eligible to be paid super if they meet the additional eligibility requirements, gig economy workers miss out on the same rights as most working Australians. These workers trade basic workplace entitlements, such as sick leave and holiday pay, for flexibility, and critically, they also miss out on the Superannuation Guarantee, despite the national mandate.

Scratch the surface, and it’s clear to see that a significant loophole exists in current labour force regulations, meaning that most gig workers are likely to be classified as independent contractors.

The superannuation system was built to ensure that Australians can retire comfortably without having to rely on the Government-funded Age Pension, taking significant pressure off government coffers so that funds can be diverted into health, education and other critical infrastructures.

Quite simply, it’s a crime not to pay super. The Australian Taxation Office clamps down on employers that don’t pay superannuation in full, or who fail to keep adequate records. The system works well, and is under constant review as reforms continue to make improvements solely aimed at growing our retirement nest egg.

But despite the removal of the $450 threshold so that workers earning even a small amount from an employer in a month are still eligible for super, the legislation hasn’t yet caught up with the gig economy, creating a deep chasm between the haves, and the have nots.

This is because most gig workers are paid per job, and not as part of a company’s payroll. In the eyes of the Australian Taxation Office, these workers are considered self-employed, or sole traders. As such, any super they put aside for themselves is a choice, rather than a legal requirement.

As a result, gig workers risk falling well short of the super they should have accrued during their working life, bringing about longer term concerns around financial security. For example, if someone worked in the industry for a decade, their super balance upon retirement would dip to $92,000 less than a minimum wage employee. Consequently, gig economy workers are more likely to rely solely on the government-funded Age Pension in retirement.

This disparity raises questions about current superannuation legislation, which doesn’t go far enough to provide protections for all workers.

While Industry Super chief Bernie Dean has made public calls for gig workers to be paid super so they can be self-sufficient in retirement, it has so far fallen on deaf ears.

Fair Work Legislation sets out to close loopholes by creating minimum standards for all workers and proposes a new definition of casual employment, but until all workers earn the same rate of super regardless of how they are employed, it doesn’t look to be all that fair.

So what is our responsibility to those caught in the gap?

Long term disparities about who is and isn’t entitled to Super raises serious questions about inequities in the system and how we consider all types of workers as part of our community and the economy.

While real change comes with policy and regulation, workers do bear some responsibility to prevent inequity falling on them. With many workers in the industry lacking practical information about their rights, education is paramount. Users of the gig economy should seek to better understand industry rules and their options, which starts by asking the right questions: What protections do I have by taking on this job? What are the risks involved? Am I setting up the right fund for myself? And how can I best think about my future self?

And in the meantime, the law might just catch up with consideration for all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Consent

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

BY Nina Hendy

Nina Hendy is an Australian business & finance journalist writing for The Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The New Daily.

I changed my mind about prisons

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Sophie Yu 14 MAR 2024

Every time the face of a criminal flashed up on the screen of our flatscreen TV, my parents would never hesitate to condemn the perpetrator, and demand the prolonged imprisonment of the thief or shoplifter.

For violent crimes, the death penalty would often come into conversation.

My siblings and I, perched on the leather couch, would listen open-mouthed, our young minds unable to comprehend how anyone would even consider such an act. I thought to myself: anyone who went to jail was inherently evil, different to normal people.

Yet, as I grew older and started to reach beyond the sheltered confines of our upper-middle-class home, that perspective gradually fell apart.

I have come to realise that our prison system is dysfunctional, a warped interpretation of right and wrong. A system designed for retribution, that essentially calls an end to a person’s potential in life, is both ethically and practically malfunctioning. Intended to benefit society through rightful punishment and restorative justice, it is instead one of the largest perpetrators of discrimination and often even worsens a prisoner’s life after release.

For instance, consider the story of Wesley Ford: a gay Whadjuk/Ballardong man, who battled with a drug addiction that fuelled 13 prison stints over two decades. He was just one of the 60% of Australian prison detainees who have been previously incarcerated. We have one of the highest recidivism rates in the world and, in a world where over half of prisoners expect to be homeless after release, and it is nearly impossible to secure employment, is that really such a surprise?

Our sentences do not tend to be harsh enough to fully realise the power of deterrence, nor are the quality or quantity of support services anywhere near sufficient to rehabilitate offenders.

In the words of Ford, ‘There were services there, but it is such a farce, because … they are so few and far between hardly anyone can get onto them.’

This also promotes a cycle of crime, further disadvantaging minority groups. Despite making up only 2% of the overall population, Indigenous Australians constitute nearly 30% of prisoners. They are twice as likely to have been refused bail by police before their first court appearance.

As for a solution, the harsher approach, employed by regimes such as Russia, is evidently unethical. Criminal behaviour must be punished, but the unnecessary imposition of prolonged sentences or even death penalties for minor offenders is closer to a violation of basic human rights, rather than the intended enforcement of justice. This is supported by various ethical frameworks, be it a utilitarian goal to preserve life, or the Christian belief in grace. Instead, especially for those who are low-risk offenders, restorative justice measures should be utilised to punish behaviour whilst also incentivising criminals to make better decisions. This approach has been proven to work, as evidenced by the Norwegian system.

With a system of small, community facilities that focus on rehabilitation and reintegration into society, Norway’s prison system ensures that prisoners do not lose their humanity and dignity whilst incarcerated. The facilities are typically located close to the inmates’ homes, ensuring that they can maintain relationships, and the cells resemble dormitories rather than jails. Norwegian prisoners have the right to vote, receive an education, and see family.

This approach may seem radical, but it has been incredibly successful in Norway. The Scandinavian nation has one of the lowest recidivism rates (20% within 2 years), a dramatic decrease since the 1990s (70-80%, like modern-day USA) when it had a more traditional system. Furthermore, ensuring that prisoners can live normal lives after release benefits the economy. Fewer people in prison means more capable adults available for employment, and many prisoners even leave with additional skills, leading to a 40% increase in employment rates after prison for previously unemployed inmates.

Yet, one drawback is the higher expenses of this system. Norway spends an average of 93,000 USD per year per prisoner, which is potentially unviable for countries with larger prison populations. Such a proposal would also likely be controversial amongst voters, unhappy with their taxpayer dollars being spent on criminals.

And might it be unethical to divert taxpayer funds to lawbreakers? To what extent does one deserve forgiveness? When does an act become unforgivable?

The issue is extremely complex, and realistically, a slightly different setup might be necessary for each unique society. Yet, the approach is undeniably more ethical, and benefits of rehabilitation are well-documented. In Australia, a country with a low population and high recidivism rates, success is highly likely.

Through the recognition that lawbreaking does not definitively indicate moral character and that factors such as socioeconomic status, bias, and even racism can impact the likelihood of incarceration, we can begin to see prisoners as human, too.

Forgiveness is a moral imperative and this is something that our prison system should reflect.

‘I changed my mind about prisons‘ by Sophie Yu is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

BY Sophie Yu

Sophie Yu is a Year 12 student at Redlands, Sydney, where she studies the International Baccalaureate. She is interested in philosophy, culture, and international affairs, and explores these through the mediums of public speaking, writing and the visual arts.

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY Layla Zak-Volpato 12 FEB 2024

“Where ignorance is bliss, tis folly to be wise.” – Thomas Grey

Gen Z live inside of an hourglass. The sand leaks steadily from underneath our feet at an imperceptible rate so that we don’t realise the ground is slipping away until we are plummeting toward the bottleneck. The 21st century has been characterised by the impending, seemingly unstoppable doom of climate change and ecosystem collapse. There is a rising epidemic amongst young people of feelings of anxiety and dread towards a future made uncertain by global warming. This sensation, the drop in the pit of our stomachs from a fall that doesn’t seem to be ending, has caused mixed reactions amongst Gen Z. While those who use sustainability as an antidote to their anxiety are praised, others who appear to act in complete denial of climate change are frequently vilified. Young people who smoke cigarettes and partake in fast fashion appear to show blatant disregard for the impact of their actions on the climate.

Unethical behaviours amongst young people are often attributed to delinquency and delayed cognitive development. While, in some cases, this may be true, the impact of climate change on moral decision-making in today’s youth is often overlooked. Gen Z hold the heavy responsibility of reversing the catastrophic impacts of climate change. As such, partaking in activities that cause both physical and environmental damage may stem from an attitude of wilful ignorance that allows young people to feel momentary freedom from this burden. With a reputation as one of the most climate-conscious generations,

Gen Z is often held to high moral standards regarding social and environmental issues. These standards make very little allowance for complex reactions to climate change that may appear to older generations as apathy. Subsequently, young people are owed a greater deal of compassion and understanding from older generations for their reactions to this unimaginable catastrophe.

Young people of the 21st century appear to be both driving and abating the effects of climate change. Some of the world’s most passionate and radical anti-climate change organisations have been spearheaded by Gen Z – reflecting their climate-consciousness. Yet, paradoxically, young people are the biggest users of disposable vapes and are frequent patrons of fast fashion giants. It’s an easy conclusion to draw that these behaviours (in a time of rampant climate change) seem to reflect opposing ideologies at best and a lack of general empathy at worst. In an article for the online publication Refinery29, ‘Gen Z & the fast fashion paradox’, Fedora Abu describes young people as “environmentally engaged yet seduced by what’s new and ‘now’”.

This attitude represents an oversimplification of the mental and ethical impacts of climate change on young people. Abu depicts Gen Z as a generation whose ethical and moral beliefs are easily corrupted by consumerism-driven desire. Many adults are quick to overlook the extreme mental load felt by Gen Z toward climate change and the emotional maturity that lends itself to this responsibility. Amongst young people, there has been a notable rise in feelings of eco-anxiety – described by the American Psychological Society as a “chronic fear of environmental doom”. Climate-related mental health issues manifest themselves through trauma, shock, substance abuse and depression.

In an online article published by the University of Melbourne about the rise of climate anxiety amongst young people, recommendations to relieve negative emotions include partaking in sustainable consumption (recycling, picking up rubbish etc.) and becoming involved in environmental campaigns. While there is no doubt that sustainable consumption and activism are positive, they may not adequately alleviate the anxiety felt by some young people. Those who structure their lives around sustainability and those who indulge in unsustainable practices may seem like opposing forces; they are, in fact, two sides of the same highly anxious, existential coin – both equally valid reactions to a sense of disillusionment with 21st-century adulthood.

Young people adopted their expectations of adulthood from the media they consumed as children. However, within a rapidly changing world, many feel a sense of disconnect with an experience of adulthood characterised by climate anxiety. Essentially, there’s a resounding sense that we haven’t gotten what was promised. As a child, my mother and I spent our bonding time in front of the TV – together she shared with me the television shows and movies that characterised her childhood and early adulthood. Before I was old enough to recognise it, the formulaic American sitcoms of the 90s and grand, romantic flicks of the 80s (often accompanied by a soundtrack of synth-heavy ballads) had begun to construct my worldview.

Watched in retrospect and with the use of a fully developed brain, however, one aspect is glaringly missing from the portrayal of adulthood presented by the media that raised us – the omnipresent threat of climate change. While only linear time is to blame for the fact that media from the past can’t represent our current reality, there is a sense of cognitive dissonance amongst young people between the future we were raised to expect, and the way adulthood has unfolded before us. For young people, the rampant, mindless consumerism of the 80’s and 90’s appears like a neon-lit mirage. The increased uptake of sustainable practices by large corporations is a movement of the 21st century. As such, many young people have rarely made a purchase without considering the environment.

For older generations, sustainability may provide feelings of empowerment and agency against the overwhelming monolith of climate change. However, sustainable living requires a significant amount of intentional thought against habitual, unsustainable habits built over generations. Within the domestic space, in particular, adopting sustainable approaches such as ‘zero waste’ living requires a significant mental load – the often invisible responsibilities of management and organisation. Whilst young people are rarely the organisers of large households, I believe a similar burden is felt towards sustainable consumerism.

Sustainable consumerism is often denoted as ‘morally good’. Thus, any action or purchase that results in waste or promotes unsustainable production carries negative moral connotations.

Climate-based moral decision-making is largely all that young people have known. In some form, choosing not to consider the planet in every choice can provide young people with a prized commodity – freedom from pressure to act with morality.

For young people, living in wilful ignorance of climate change and damaging the planet (and their bodies) in the process is a form of catharsis and escapism. Drinking from plastic water bottles, smoking chemical-filled cigarettes and purchasing clothes mass-produced in sweatshops allows Gen Z to experience a pantomime of the careless, invincible youth that was promised.

Viewed through a binary moral lens, older generations are quick to criticise young people as careless and apathetic. In reality, there’s an unshakable sense of dread amongst young people that a natural disaster will take our lives by the time we reach our parents’ age. In Thomas Grey’s poem ‘Ode on a distant prospect of Eton college’, he states “Where ignorance is bliss, tis folly to be wise”. In essence, if knowing something harmed you, would you be better off not knowing at all? If there’s one thing that Gen Z know, it’s that there is unavoidable harm in their future. If that is the case, and there’s nothing that can be done, may as well have a cigarette.

‘Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world‘ by Layla Zak-Volpato is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

BY Layla Zak-Volpato

Layla is a 22-year-old writer and poet living and working in and around Eora/Sydney. With an educational background in ecology and wildlife conservation, her work focuses heavily on the ethical and moral dilemmas of the anthropocene. Through a creative lens, Layla examines the intersections between gender, identity, philosophy and environmental issues. She aspires to use these themes as the backbone for a career as a scientific communicator who utilises both creative and informative literary forms.

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Nick Jarvis 30 NOV 2023

There is no denying that alcohol is inextricably linked to Australia’s social DNA. Going to the pub with mates, drinking at a BBQ or picnic, at dinner parties, house parties, birthdays or gigs – all of these link “having a drink” with “having a good time” in our national consciousness.

A Roy Morgan research study in 2022 found that the majority (67.9%) of Australians had consumed alcohol in the last month, with the average Australian consuming nearly 10 litres of pure alcohol a year (2017-18 study).

In fact, a 2021 survey named Australians the heaviest binge drinkers in the world, finding we would binge an average of 27 times a year, almost double the global average – although overall alcohol consumption rates have been dropping since the early 2000s.

When it comes to work, alcohol is closely tied to socialising – Friday after work drinks, celebratory drinks to recognise a goal achieved, Christmas parties, launches, networking events; all of them invariably involve alcohol in some capacity. Some people might even say they can’t stomach a work social event unless alcohol is involved.

In some cultures binging is even built into work culture – in China, heavy drinking after a deal has been sealed is a time-honoured ritual, where everyone involved has to let their guard down and form a “moral contract” bound by heavy drinking together. In Japan, nomikai, or drinking parties, are an integral part of workplace culture for socialising and bonding, and everyone is expected to take part.

Alcohol certainly has its benefits as a social lubricant at work events, allowing people to bond together faster, but it also has its dark side – harassment after the lowering of inhibitions, saying something inappropriate to a colleague, potentially embarrassing yourself in front of your team or clients, even assault can follow heavy drinking with work mates.

Having work social rituals based around the consumption of alcohol is also exclusionary for those who choose not to drink, whether because of physical or mental health reasons, religious or cultural reasons, or because they’ve quit or just don’t want to. People may feel pressured to drink in work social spaces, to be social, to network and keep up with the team. A 2019 survey by the UK’s Drinkaware found that more than half of workers surveyed would like there to be less pressure to drink at work events.

And people are increasingly opting out of alcohol-fuelled leisure time, a trend led by the more risk-aware Gen Z. The 2019 National Drug Strategy Household Survey found that, in 2001, the people most likely to have consumed alcohol daily, used illicit drugs or smoked cigarettes were in their 20s. By 2019, that had changed to people in their 40s and 50s. The survey also found the number of people in their 20s who don’t drink at all increased from 9% to 22% between 2001 and 2019.

The drinks industry has adapted, with sales of zero alcohol substitutes rising over 100% in the two years to 2022, but in many cases our workplaces have not.

As more people are becoming ‘sober curious’, or trying to reduce their alcohol intake, it can make it awkward in the workplace when you decline an “al-desko” beer or to troop along to Friday after work drinks. Missing out on socialising with your colleagues can also be a barrier to making closer connections and friendships.

So what responsibility do workplaces have to their employees to offer alcohol free options for socialising, while also respecting the rights and choices of employees who want to drink responsibly?

Employers are mandated ethically and legally to provide safe, inclusive workplaces, and this should include respecting people’s decision to either drink alcohol or not drink alcohol and still be able to participate socially with their workmates and colleagues.

Rather than banning alcohol at work, providing zero alcohol drink options and alcohol-free bonding activities are an easy way employers can foster an inclusive environment, while respecting individual choice.

Just as we’ve seen the “smokers huddle” outside office buildings dwindle to near invisibility in the past ten years, I predict that we’ll soon see a marked increase in the availability of non-alcoholic options at work events and alternative socialising options that don’t come with any pressure, latent or otherwise, to imbibe. Which can only be a good thing for our livers and work-related hangxiety.

BY Nick Jarvis

Nick Jarvis is a Sydney-based editor and writer on the arts, culture and technology. He's written for The Ethics Centre, the Walkleys, Sydney Festival, Sydney Film Festival, Vice and many Australian arts organisations. He currently works for Sydney Festival.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Capitalism is global, but is it ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Life and Shares

Thinking about investing? Chances are, you’re already playing the game. This new podcast unpicks the share market so you can better understand how the system works.

Did you know that some trading apps use the same psychological tricks as gambling apps? That the big players in financial services can pay to get “privileged access” to the ASX?

Life and Shares is a podcast from The Ethics Centre about the share market. Even if you don’t actively invest, chances are that you are already connected to the share market; as a taxpayer in Australia, a significant amount of your superannuation is already being traded.

In this four-part series, hosted by The Ethics Centre’s Cris Parker, we’ve assembled people from different industries to help you understand the rules of the game so you can make informed decisions. We’re looking beyond the jargon to unpack how the system works and what ethical issues you could – and should – consider if you decide to play.

Some may tell you they can pick a winning share. This series unpicks the share market so that you can make decisions you’ll be proud of.

Available to listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

This podcast is presented by The Ethics Centre. Our work is made possible by donations including the generous support of Ecstra Foundation – helping to build the financial wellbeing of Australians. This series follows the popular first season, Life and Debt.

Life and Shares Podcast Trailer

Whats inside the guide?

EPISODES

EPISODE ONE: PEELING BACK THE LABEL

Let’s break down the jargon: starting with investor classifications.

Did you know that your level of wealth impacts how you can invest in the share market? In this episode, we hear from RMIT Associate Professor Chris Berg who thinks it’s “deeply unethical” that retail investors (‘mum and dad’ investors) don’t have access to the kind of products that rich people do and so are shut out of some of the most lucrative and risky investments… but accountants say there’s a good reason for that.

We also learn about the murky areas of ‘ethical’ and ‘sustainable’ investing and how it differs from ‘responsible’ investing. If an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) is labelled sustainable, is it irresponsible for it to have a large holding in a fossil fuel company? Is ESG reporting the best way to judge which companies are good to invest in?

GUESTS:

- Chris Berg, Associate Professor at RMIT University and Director and Co–founder of the RMIT Blockchain Innovation Hub

- Susheela Peres da Costa, Principal at The Stewardship Centre

EPISODE TWO: WHO'S RUNNING THE SHOW?

If video killed the radio star, have brokerage apps killed the stockbroker? What’s the role of robo-advisers? And how are algorithms shaping the marketplace?

Did you know that the big players in financial services can pay to get “privileged access” to the ASX? We ask Paul Lajbcygier from the Monash Data Futures Institute, is that fair?

We also hear from UNSW Professor Gigi Foster who thinks greed and profit make the market go round – and that’s not a bad thing. But on the other hand, she acknowledges there’s a growing class of people who don’t work for their wages – they just move their investments around.

GUESTS:

-

-

- Gigi Foster, Professor with the School of Economics at the University of New South Wales

- Paul Lajbcygier, Computation Finance expert at the Monash Data Futures Institute

-

EPISODE THREE: IS TRADING GAMBLING?

For the first two months of COVID, nearly 5,000 Australians opened an online trading account… every day. Eighty percent of them lost money.

So, is trading gambling? We speak with a clinical psychologist who’s concerned about the lack of awareness and resources for people addicted to trading. We also speak with co-founder of the International Day Trading Academy Cameron Buchanan, who admits that while trading is gambling, he thinks there’s an essential difference.

GUESTS:

- Cameron Buchanan, Co-founder of the International Day Trading Academy

- Anonymous Guest, Clinical Lead at a gambling treatment centre

Listen to Ep 3 on Apple or Spotify now.

EPISODE FOUR: THE POWER OF PERSUASION

Humans aren’t rational… and yet so much economic modelling assumes we are.

In this episode, we look at a Canadian experiment that investigated the ‘gamification’ of investment apps… and how one minor tweak to the app saw people increase the number of trades by a whopping 40%.

We meet behavioural finance specialists Angel Zhong from RMIT University and Ravi Dutta Powell from The Behavioural Insights Team, who explain how cognitive biases impact how we assess risk and make investment decisions.

GUESTS:

- Angel Zhong, Associate Professor of Finance, RMIT University

- Ravi Dutta-Powell, Senior Advisor, The Behaviour Insights Team