CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 6 MAR 2020

A virus knows no race. It is indifferent to your religion, your culture and your politics. All a virus ‘cares about’ is your biology … For that, one human is as good as any other.

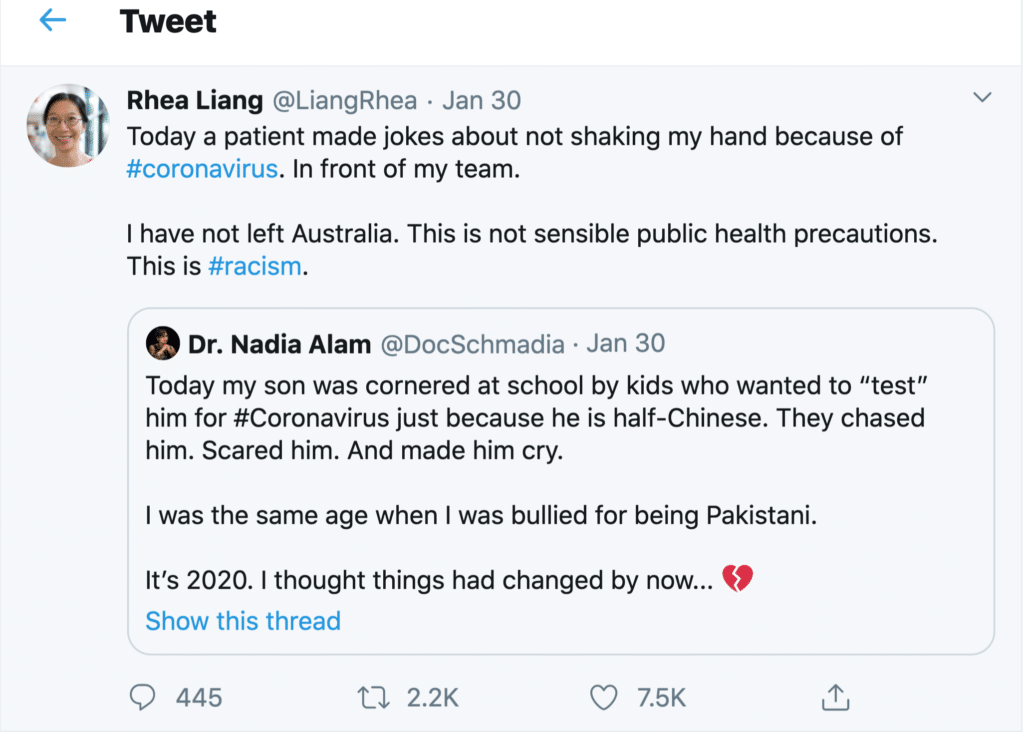

Despite this, it’s easy enough to find recent reports of Australians experiencing discrimination for no reason other than their Chinese family heritage.

Such attacks are examples of racism – the irrational belief that an individual or group possesses intrinsic characteristics that justify acts of discrimination. That this is occurring is not in doubt.

For example, Australia’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Brendan Murphy has seen enough of such behaviour to make explicit reference to the phenomena, labelling xenophobia and racial profiling as “completely abhorrent”.

Professor Murphy’s position is one of principle. However, there is also a practical aspect to his admonition. Managing the risks of an outbreak of a pathogen like the novel coronavirus COVID-19 requires health officials and the wider community to make rational choices based on an accurate assessment of risk. Racism is irrational. It distorts judgement and draws attention away from where the risks really lie. Ethically it is wrong. Medically, it is idiotic and dangerous.

This rise in racism, prompted by the emergence of COVID-19, reveals how thin the veneer of decency is that keeps latent racist tendencies in check. It seems that, given half-a-chance, the mangy old dog of Sinophobia is ready to raise its head, no matter how long it has laid low.

Of course there is nothing new about Sinophobia in Australia. Fear of the ‘yellow peril’ is woven through the whole of Australia’s still-unfolding colonial history. Many factors have stoked this fear, including: persistent doubts about the legitimacy of British occupation of an already settled continent, ignorance of (and indifference to) Chinese history and culture, the European cultural chauvinism that such ignorance fosters, the belief that numerical supremacy is, ultimately, a determining force in history, the need to find scapegoats when the dominant culture falters, and so on.

Whatever the historical cause of this persistent fear, the present ‘trigger’ is the inexorable rise of China as an economic and military super power – a power that is increasingly inclined to demand (rather than earn) deference and respect.

The situation is made more volatile by the growing tendency for the China of President Xi Jinping to link its power and success to what is uniquely ‘Chinese’ about its history and character. Add to this a broadly accepted Chinese cultural preference for harmony and order and the nation is often presented as if it is a ‘monolithic whole’ – not just in terms of its autocratic government but in its essential character.

Unfortunately, all of this feeds the beast of racist prejudice. Those who feel threatened by the changing currents of history seize on even the flimsiest threads of difference and use these to weave a narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’ – in which others are presented as being essentially and irremediably different. This is the racists’ central trope – that difference is more than skin deep! Biology makes you one of ‘us’ or you are not.

It’s nonsense. Yet, it’s a nonsense that sticks in some quarters, especially during times of uncertainty such as this; when the general public is feeling betrayed by the elites, when institutions have lost trust and have weakened legitimacy and when increasing numbers of people fear for their future and that of their families.

Unfortunately, tough times provide fertile ground for politicians who are willing to derive electoral dividends by practising the politics of exclusion. It is a cheap but effective form of politics in which people define their shared identity in terms of who is kept outside the group.

It is far harder to practise the politics of inclusion – in which disparate groups find a common identity in the things they hold in common. This too can work, but it takes great energy and superior skills of leadership to achieve this outcome. Yet, it is the latter approach that Australia must look for, if only as a matter of national self-interest.

This is because racist attacks against Australians of Chinese descent also have a significant national security dimension. As I have written elsewhere, social cohesion is a vital component of a nation’s ‘soft power’ when defending against foes who covertly seek to ‘divide and conquer’.

The risk of such attacks is increasing as the world drifts back to a pre-Westphalian strategic environment in which the international, rules-based order breaks down and nations freely interfere with the domestic affairs of their rivals. In these circumstances, the last thing Australia needs is deepening divisions based on spurious beliefs about supposed racial deliveries.

Those who create or exploit those divisions wound the body politic, weaken our defences and undermine the public interest.

All of that said, it is important not to overstate the dimensions of the problem. Australia is a notable successful multicultural nation where harmonious relations prevail. This is despite there being an undercurrent of racism that has been more or less visible throughout Australia’s modern history.

Racism is never justified. Not by the fact that it is found to the same degree in other societies, and not even when its manifestation is rare. Although it offers little comfort, it should also be acknowledged that discrimination is as much a product of other forms of prejudice concerning religion, gender, culture, etc.

We have the capacity to do and be better. This is a choice we can and should make for the sake of our fellow citizens – whatever their background – and in the interests of the nation as a whole.

So, given that China is not likely to take a backwards step and Australians of Chinese background cannot (and should not) disguise their heritage, how should we respond to the latest bout of Sinophobia?

Attack prejudice with fact

A first step should be to follow the example of Australia’s Chief Medical Officer and attack prejudice with the facts. Professor Murphy’s example showed how facts about medicine can be deployed to calm fears and neutralise racist myths. This approach should be extended to other areas. For example, more should be known of the long history and extraordinary contribution of Australians of Chinese heritage.

This account should not merely tell the story of elite performance, economic contribution, etc. It should also speak of those who have fought in Australia’s wars, built its infrastructure, educated its children, nursed its sick … and so on. In short, we need to see more of the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Reframe the narrative

Second, we need to reframe the narrative about China and the Chinese. Today, most commentary portrays China as both a security threat and an economic enabler. It is both. However, this is only a small part of the story.

For the most part, we see little of the life of the Chinese people. We are largely ignorant of the achievements of their remarkable civilisation. One might think that the closeness of the economic relationship might be a positive factor. However, regular reporting about Australia’s economic dependence on China, is not helping the situation.

I know that this will seem counter-intuitive to some. However, the more we speak of Chinese students propping up our universities, of Chinese tourists sustaining our tourism industry and of Chinese consumers boosting our agricultural exports … the more it makes it sound as if the Chinese are little more than an economically essential ‘necessary evil’ – a ‘commodity’ that comes and goes in bulk.

This view of the Chinese negatively influences attitudes towards Australia’s own citizens of Chinese descent. Fortunately, a solution to the ‘commodification’ of the Chinese is at hand, if only we wish to embrace it. The large number of Chinese students who study in Australia offer an opportunity to build better understanding and stronger relationships.

Unfortunately, the Chinese student experience in Australia is reported not to be as positive as it should be. Too many arrive without the English language skills to engage more widely with the community. Too many find themselves lonely and isolated. Too many find solace in sticking with those they know and understand. With some justification, large numbers feel as if they are little more than a ‘cash cow’.

Invest in ethical infrastructure

Third, we need to invest in Australia’s own ‘ethical infrastructure’ – much of which is damaged or broken. We need to repair our institutions so that they act with integrity and merit the trust of the wider community. We need to work on the core values and principles that underpin social cohesion.

Part of this task must be to come to terms with the truth about the colonisation of Australia. This is not to invoke the ‘black arm band’ view of history. The truth is both good and bad. However, whatever its character, our truth remains untold. I sincerely believe that Australia’s ‘soft power’ is weaker than it would otherwise be, if only we could address this unfinished business.

Alleviate fear

Fourth and finally, the measures outlined above will be ineffective unless we also name the latent fears of average Australians. People across the nation want these ‘bread and butter’ issues to be acknowledged and addressed:

- How safe is my job?

- If I lose my current job, will I find another?

- If I can’t find another job, how will I pay my bills?

- Will I be cared for if I get sick?

- Will my children get an education that equips them to live a good life in the future?

- Can I move about with relative ease and efficiency?

- How will the nation feed itself?

- Are we safe from attack?

- Who can step in cases of natural disaster or man-made calamity?

- Why are our leaders not held to account when we are?

- Why can’t I be left alone to do as I please?

- Who cares about me and those I care about?

Failure to speak to the truth of these deep concerns leaves the field wide open for the lies of those who would stoke the fires of racism.

Unravel the complexities of the political relationship between China and Australia at ‘The Truth About China’, a panel conversation at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Saturday 4 April. Tickets on sale now

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How can we travel more ethically?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Nick Evans 19 FEB 2020

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you’ve heard of the outbreak of coronavirus, officially called “SARS-CoV-2”, that has caused disease primarily in Wuhan, China.

The virus, which causes a disease called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has spread to 25 countries, infected more than 73,000 people, and caused 1,873 deaths. The World Health Organization has declared the outbreak a “Public Health Emergency International Concern” and more than 50 countries — against the WHO’s advice — have implemented travel restrictions and quarantines in an attempt to prevent the spread of the disease.

There’s been a lot of worry about this coronavirus, but arguably the thing that is driving this worry is uncertainty. It can’t be the deaths alone – fewer than 1,900 people have died of COVID-19. In contrast, since October, 14,000 people in the USA alone have died of influenza.

Unlike the 1918 influenza pandemic or the 2009 influenza pandemic, both of which killed young people faster than normal flu, the people who are dying of COVID-19 are typically old, have pre-existing diseases that make them vulnerable to pneumonia (one of the main ways COVID-19 kills you), or are heavy smokers.

Despite its rapid increase in cases in China — driven, in part, by a change in definition of how they count cases — the number of cases elsewhere has stayed relatively low.

A reported 2.5 per cent of the patients diagnosed in China have died, yet fewer than 0.4 per cent of patients elsewhere in the world have died – a bit more than seasonal flu, but not much, and not as widely.

So why the fear? And why the fantastical conspiracies: tens of thousands dead but hidden in China; a laboratory escape; or even a biological weapon? There are surely a lot of reasons: the actions of the Chinese government during the 2003 SARS outbreak; general distrust of China in a media responding to Washington’s belligerence; and some enterprising grifters out to make their name or make a buck.

Still, these all take hold in an environment of uncertainty. And in ethics, how we deal with uncertainty is a tricky case. A classic example of why uncertainty can be tricky from the perspective of ethics goes something like this.

Say I ask you to play a game: I roll a normal dice; if it lands 1-5, you get $1; if it lands on a 6, you pay me $2. To many people this seems like a good deal. Five chances to win; one to lose. You should expect, mathematically, to win 50c each game. But what if I pull out a weird, many sided dice with 120 sides. If the dice land 1-119, you get $1. But if it lands 120, I get $59. It might feel different, but the expectation (again, mathematically) remains the same.

Now imagine a huge dice in which that one chance of a loss was $10,000, or even $1 million… Part of the reason it feels different is psychological. After all, $59, or $10,000 is so much more than $2, and so even though your chances of losing are decreasing, the pit in your stomach at the thought of losing $10,000 is probably a lot more. Moreover, you’re risking that for $1 each time. Sounds like playing with fate, and you might not want to play with fate when fate could take your house if it wins.

Another part of the reason it feels different is that we don’t often encounter — or at least don’t recognise — extreme cases in our lives where we face a small chance of a huge loss. My colleagues and I have looked at this phenomena in the case of things like laboratory safety, or industrial regulations. But the same goes for things like pandemics.

Coronaviruses circulate in animal populations, usually certain species of bat, and typically don’t infect humans.

Occasionally a virus does, often through an intermediate species, and the results can be bad. It can be really hard to figure out how bad, though. So we don’t know when these viruses will appear, or how bad they are going to be.

Given that, it can be really easy to get complacent before the fact, and even easier to overreact after the outbreak starts. This leads us to take drastic actions such as to violate human rights in the name of protecting public safety (or at least appearing to protect safety), even when those actions are shown to be ineffective. But this is because instead of winning a dollar, preparedness costs us that dollar. It’s hard to get governments to spend dollars today that might not benefit us until 2030, but if we wait until we need it, we could lose everything.

It turns out that the best solution to these scary, uncertain diseases is to invest, as a society, day to day. That costs resources, but it’ll help out when the “big one,” the next 1918 flu, comes. COVID-19 is unlikely to be that kind of pandemic, but even it is testing global health systems.

We need, as a society, to get better at dealing with the uncertain, by investing in preparedness today.

Better healthcare systems; more nurses, doctors, and scientists; a more aware community; local plans for infection control that match the plans of national governments; and protections for people in quarantine so they don’t lose their livelihoods or, as is the case in some countries, have to pay for their own quarantine when they aren’t even sick.

These investments cost governments money. They cost us taxes. But if you’re scared of COVID-19, with all its uncertainty, you should be much more scared that we’re not doing the ordinary, everyday things that’ll keep us safe.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Where do ethics and politics meet?

BY Nick Evans

Dr Nicholas G. Evans is an assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts Lowell who focuses the majority of his research on national security and the ethics of emergent technologies. Nick also maintains an active research program on the ethics of infectious disease, with a focus on clinical and public health decision making during disease pandemics.

The virtues of Christmas

The virtues of Christmas

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 20 DEC 2019

Christmas is upon us. It’s a time of giving. A time for celebrating with family and love ones. And a time to navigate a number of sticky ethical challenges.

It starts early in the morning; the gifts are distributed, and you unwrap Grandma’s exquisitely wrapped parcel only to reveal a hideous pair of underwear that may have once been in fashion during the great depression. You immediately call on your best poker face, but it may have already betrayed your disappointment. Should you lie and say, ‘thanks Nan, I really love them?’

Next comes the Christmas lunch tirade; you’re seated next to an opinionated uncle you only see once a year at Christmas who, predictably, after too many of his favourite Christmas beverages begins an annual festive diatribe that escalates rapidly from the opinionated to the offensive. Do you speak your mind?

Finally, the inevitable clash with your mother in law; she cannot help being critical about everything surrounding the festivities. The inevitable flare-up will happen after clearing away lunch, which you like to refer to it as the annual arm wrestle, a well-worn conflict over everything from how to stack the dishwasher to how the kids can and cannot play. This year will no doubt be worse as you are hosting the event. Do you stand your ground?

Most of us ask “What should I do?” when we think about ethics. However, we can approach it another way by asking, “What kind of person should I be?” Philosophical thinkers in this tradition turn to virtue ethics for the answers.

While it’s one thing to ask what kind of person should I be, it’s another thing to know how to live as that person. For Aristotle the answer to both of these questions is to act virtuously. Acting as though we already possess the best virtues is how we develop a virtuous character.

And if ever there was a time to test out the virtues of our character, it’s Christmas.

Virtue ethics, unlike other approaches, does not provide specific rules for addressing ethical questions. Instead, good actions are those that a person of good character would display. Aristotle, one of the most influential philosophers in this tradition, developed a comprehensive system of virtue ethics.

Let’s take a look at how it can help us navigate the minefield of Christmas’ annual dilemmas.

The underwear from Grandma? If asking what should you do, you might take a lead from consequentialism. You could simply smile and say ‘I love it Grandma’. After all, she meant well, a white lie makes her happy, keeps the economy ticking and doesn’t rock the family emotional boat. It produces the best overall outcome.

Other philosophers might suggest a different approach. Those in the deontological tradition, such as Immanuel Kant would argue that lying of any kind is unethical, even those white lies that are intended to spare someone’s feelings.

Unlike other approaches to ethics, virtue ethics does not rely on rules to guide action. While ‘do not lie,’ is a rule, ‘being honest’ is a virtue.

However, a virtue, on its own, doesn’t tell us too much that is helpful because virtues are interrelated, you can’t have one virtue without having others. To have a virtue is to be a particular type of person with a particular mindset and outlook on life. They are what’s called a ‘multi-track disposition’ – they go all the way down.

Honesty is not the only virtue at stake here. Acting virtuously requires us to calibrate between virtues. Because Grandma has the best intentions, she will no doubt take your honesty to heart. Honestly speaking your mind could be selfish at one extreme, and while a white lie at the other end might be considered selfless. What sits between these extremes Aristotle called the Golden Mean.

What would a fair person do? They might tell Grandma that they appreciate the thought but would like to do justice to her intentions by exchanging the gift for something that they will like, wear and remember Grandma every time they put it on.

So, let’s see what virtue ethics can teach us about managing that outspoken uncle. Imagine that dessert is now served and your uncle has flipped the switch to obnoxious. You try and avoid engaging with his tirades every year, but this year he is particularly offensive. His views are not only a dampener on the festive feels, but several members of the family are visibly hurt and upset by some of his more extreme views.

All families have their patterns that play out when people come together and the pre-determined roles we all play are difficult to shift.

What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining what a virtuous character would do in this situation we can start to practically explore how to become the best version of ourselves.

In the virtue ethics approach imagination is important in helping to shift unthinking and prescribed patterns of behaviours. What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining what a virtuous character would do in this situation we can start to practically explore how to become the best version of ourselves.

A virtuous person might ask themselves ‘how would I like to be treated if I were them?’ This particular uncle may not have many opportunities in their daily life to be heard. In many of the virtue ethics traditions compassion is a cardinal virtue. Exercising the virtue of compassion allows us to not only avoid rushing to judgement, but also gives us space to disarm the triggers that usually fire off in response to his toxic views.

The virtue of temperance – self-control and restraint – also helps here. While his views may trigger you strongly, appealing to logic with counterarguments will most likely not be effective.

It is almost impossible to change a person’s strongly held views with counter-logic. Paraphrasing back the points and emotions they are expressing not only lets them know their experience matters but also provides a circuit breaker by reflecting back their views. Research suggests that engaging in this way can make someone feel more understood and, as a result, less defensive or difficult.

When unsure about what the best virtue looks like in practice, virtue ethics suggests looking to someone of good character for direction by imagining how they would act in the same situation. Moral exemplars are an important feature of virtue ethics. Ethics is messy and no decision procedure provides a precise algorithm which will tell us definitively what to do when faced with difficult choices. Moral exemplars are people in our world who possess the best form of the virtues. Knowing what to do is not simply a matter of internalising a rule; for Aristotle virtue ethics it is about doing the right thing at the right time, in the right way and for the right reason. Moral exemplars help show us the way.

So, when it comes to the inevitable clash with your mother in law, imagine what someone you admire most would do. A moral exemplar might act intentionally with the virtues of humility, grace and generosity, showing her that what is important in hosting Christmas is not the power struggle to control the day but respecting differences and others’ boundaries. They might find ways to include some of her traditions in the day.

The development of character is at the heart of virtue ethics. We develop that character throughout our life through the virtues and in doing so we make wise choices.

This Christmas people may be looking at you to be that person.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 DEC 2019

If you’re looking for ways to support a more ethical life, here are five simple lifestyle changes that can help get you there.

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to an increase in the experience of positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand other people’s mental states are different from our own. It’s a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drink driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ – weakening our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 19 DEC 2019

The kids are on school holidays but the lessons don’t have to end there. Christmas time offers a great opportunity to teach our kids about ethics. Philosopher Dr Matt Beard shares his top stories for sharing ethical ideas with your children.

1. How the Grinch Stole Christmas – Doctor Seuss

The Grinch is a lonely monster who lives by himself on Mt Crumpit. Bothered by the Christmas noise from nearby Whoville he decides to spoil their fun. Disguised as a particularly ugly Santa Clause, the Grinch sneaks down the chimneys of the people of Whoville and steals their gifts. But to the Grinch’s surprise, he can’t dent the Whos’ Christmas spirit and his heart starts to melt.

“What if Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from a store? What if Christmas… perhaps… means a little bit more?”

This classic by Doctor Seuss is more relevant than ever for kids growing up in an age when the holiday season is increasingly commercialised. The Whos lose all their ‘stuff’ but don’t lose their sense of Christmas. How would you or your kids feel if there were no presents at Christmas? What would you celebrate?

2. The Selfish Giant – Oscar Wilde

Not technically a Christmas story, but still a lovely one for this time of year. It’s the tale of a selfish giant who first refuses to allow children to play in his gardens and then has a change of heart.

This story has extra resonance for readers within the Christian tradition (and kids may need an explainer as to what the ending means), but the message does transcend religion. Talk to your kids about how selfishness can be isolating, joys shared are joys multiplied and the importance of showing kindness to whomever we meet – strong, weak, tall, clever or otherwise.

3. The Lump of Coal – Lemony Snicket

Coal is the perennial threat against children – bad kids get given coal. But what happens when a lump of coal is good? What happens if the child who receives it wants to make art? And do all kids who receive a lump of coal turn out rotten?

Lemony Snicket’s short story big questions of authenticity and purpose through a living lump of coal that flees a barbeque in search of it’s own purpose. After some failed endeavours he meets a department store Santa who puts him into his ‘bratty’ son’s stocking.

But his son doesn’t feel punished. Together with the lump of coal they become successful artists and open a restaurant in Korea.

“It is a miracle if you can find true friends, and it is a miracle if you have enough food to eat, and it is a miracle if you get to spend your days and evenings doing whatever it is you like to do.”

It’s not your typical Christmas story, but that’s part of the appeal. Are we forced to be the people we’re born as? The Lump of Coal teaches us gratitude for the everyday and an ability to overcome social origins of birth.

4. The Gift of the Magi – O Henry

This is a personal favourite and a good one to read before you take your kids off for a last minute Christmas shop. A married couple, both hard up for money, are desperate to buy each other wonderful gifts. Della wants to buy James a superb chain for his watch, which is his prized possession. To pay for it she sells her hair – her pride and joy, and James’ too. She buys James a fetching chain only to learn he has sold his watch to buy her a new set of combs!

“But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.”

The Gift of the Magi could seem absurd to some – to highlight the pointlessness of our obsession with giving. But that wasn’t the message O Henry hoped readers would take away. He wanted to highlight the true meaning of gift giving – a thoughtful gesture to rekindle a connection to the other person.

5. The Original Christmas Story

Whether or not you’re religious, the origins of Christmas lie in the same story – of a baby in a manger, surrounded by shepherds, angels and wise men. Props aside there are universal messages to be gleaned from religious stories and traditions.

The Christian story holds that the world’s saviour arrived as a newborn child into a stable for farm animals. It’s worth having a talk about how this image contrasts with our usual ideas about power.

Do we sometimes dismiss people because of where they’ve come from or how much money they have?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Agape

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 18 SEP 2019

I recently came across a quote from philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau, talking about what it means to live well:

“To live is not to breathe but to act. It is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence. The man who has lived the most is not he who has counted the most years but he who has most felt life. Men have been buried at one hundred who have died at their birth.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I found myself nodding sagely along as I read. Because life isn’t something we have, it’s something we do. It is a set of activities that we can fuse with meaning. There doesn’t seem much value to living if all we do with it is exist. More is demanded of us.

Rousseau’s quote isn’t just sage; it’s inspiring. It makes us want to live better – more fully. It captures an idea that moral philosophers have been exploring for thousands of years: what it means to ‘live well’ – to have a life worth living.

Unfortunately, it also illustrates a bigger problem. Because in our current reality, not everyone is able to live the way Rousseau outlines as being the gold standard for Really Good LivingTM.

This is a reality that professionals working in the aged care sector should know all too well. They work directly with people who don’t have full use of their organs, their faculties or their senses. And yet when I presented Rousseau’s thought to a room full of aged care professionals recently, they felt the same inspiration and agreement that I’d felt.

That’s a problem.

If the good life looks like a robust, activity-filled life, what does that tell us about the possibility for the elderly to live well? And if we don’t believe that the elderly can live well, what does that mean for aged care?

If you have been following the testimony around the Aged Care Royal Commission, you’ll be aware of the galling evidence of misconduct, negligence and at times outright abuse. The most vulnerable members of our communities, and our families, have been subject to mistreatment due in part to a commercial drive to increase the profitability of aged care facilities at the expense of person-centred care .

Absent from the discussion thus far has been the question of ‘the good life’. That’s understandable given the range of much more immediate and serious concerns facing the aged care sector, but it is one that cannot be ignored.

In 2015, celebrity chef and aged care advocate Maggie Beer told The Ethics Centre that she wanted “to create a sense of outrage about [elderly people] who are merely existing”. Since then she has gone on to provide evidence to the Royal Commission, because she believes that food is about so much more than nutrition. It’s about memory, community, pleasure and taking care and pride in your work.

Consider the evidence given around food standards in aged care. There have been suggestions that uneaten food is being collected and reused in the kitchens for the next meal; that there is a “race to the bottom” to cut costs of meals at the expense of quality, and that the retailers selling to aged care facilities wildly inflate their prices. The result? Bad food for premium prices.

We should be disturbed by this. This food doesn’t even permit people to exist, let alone flourish. It leaves them wasting away, undernourished. It’s abhorrent. But what should be the appropriate standard for food within aged care? How should we determine what’s acceptable? Do we need food that is merely nutritious and of an acceptable standard, or does it need to do more than that?

Answering that question requires us to confront an underlying question:

Do we believe aged care is simply about providing people’s basic needs until they eventually die?

Or is it much more than that? Is it about ensuring that every remaining moment of life provides the “sentiment of existence” that Rousseau was concerned with?

When you look at the approximately 190,000 words of testimony that’s been given to the Royal Commission thus far, a clear answer begins to emerge. Alongside terms like ‘rights’, ‘harms’ and ‘fairness’ –which capture the bare minimum of ethical treatment for other people – appear words such as ‘empathy’, ‘love’ and ‘connection’. These words capture more than basic respect for persons, they capture a higher standard of how we should relate to other people. They’re compassionate words. People are expressing a demand not just for the elderly to be cared for, but to be cared about.

Counsel assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Gray QC, recently told the commission that “a philosophical shift is required, placing the people receiving care at the centre of quality and safety regulation. This means a new system, empowering them and respecting their rights.”

It’s clear that a philosophical shift is necessary. However, I would argue that what’s not clear is if ‘person-centred care’ is enough. Because unless we are able to confront the underlying social belief that at a certain age, all that remains for you in life is to die, we won’t be able to provide the kind of empowerment you felt reading Rousseau at the start of this article.

There is an ageist belief embedded within our society that all of the things that make life worth living are unavailable to the elderly. As long as we accept that to be true, we’ll be satisfied providing a level of care that simply avoids harm, rather than one that provides for a rich, meaningful and satisfying life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Amy Gray 22 AUG 2019

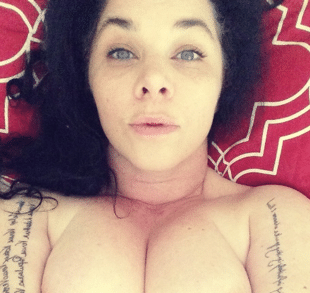

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. By emphasising the potential for women to be made victims, we ignore the ways a woman’s body can be an expression of power.

According to the prevailing moral panic of the day, young women take naked selfies in order to please others and not themselves. This, we’re told, leaves them vulnerable to exploitation because women must always be vulnerable.

It’s as though the only mystery afforded to women is not their thoughts or talents but what lies underneath their clothes. Go no deeper than the skin. Deny any complexity that might present her as a human with needs separate from what men may want.

This seems to be a narrative we teach teenagers. My daughter was taught that not only was there no legal recourse for photos shared without consent (untrue) but that the effects on women were so catastrophic that they should never send a naked photo (also, untrue). This happened on International Women’s Day, as if to remind us of our to-do list.

Inevitably, they learn what we teach. When I worked with teens on a short film, they told me how boys pestered every girl in their class for naked selfies. The girls didn’t even think it was sexual; more of a competitive collection like Pokemon Go but for undeveloped breasts. The requests were thought of as frustrating but normal, because “that’s just how they are”. Yet despite the mundanity of such a frequent request, the same teens sincerely believed leaked selfies would hound a woman to her grave.

Naked selfies carry many gendered clashes. I’ve always gasped at the difference between gendered aesthetics: I’ll rush to clean my room, groom and put on makeup before getting into an appropriate outfit of sorts before painstakingly composing shots; men just send a close-up photo of their cock jutting from a thicket of pubes.

It’s an effective example of the differences between the male and female gaze. A woman prepares because she is conditioned to know what men find attractive and that she is expected to deliver that. Men, conditioned to expect immediate access regardless of merit, put almost zero thought into their selfies. In the rare case they do, they project an image of themselves they want to see, rather than women who mirror what men want to see.

This positioning reinforces the power dynamic in heterosexual sexting. Men expect entertainment and women entertain at threat of exposure (also expected).

But why does the power lie with men?

On image sharing site Imgur, men enthusiastically share photos of naked women, even creating themed days for certain ‘types’ of women. But the images presented reflect the male gaze – photos taken of women, not by women.

Generally, whenever women posted selfies on Imgur, sexualised or not, she was immediately inundated with caustic remarks to stop being an exhibitionist (a polite euphemism for attention whore). That these are the same men who think nothing of going into a woman’s DMs to ask for naked photos is just another layer to it all. There is a clear mode of production, where women are the object and men remain in control of when and how they are seen. This is where the phrase “tits or get the fuck out” shows its intent: give us the body parts, not the entire body.

Perhaps this is because it is easier to sexually appreciate an object that has not been humanised or seen as an individual. When things are anonymised or presented in such a volume that they lose all semblance of individuality, they become an object that can be appreciated or abused without shame.

The power balance still rests with men – naked women are objects men readily expect, and demand to be presented in anticipated service of them. In this position of power, men expect women to arouse them, yet rarely consider whether women are aroused. Amazingly, we rarely discuss whether women find joy or pleasure in taking naked selfies, whether for themselves or others because we can’t move past women’s seemingly inevitable victimhood.

I’ve taken naked selfies for well over a decade. I first worried if photos might leak but, somewhat ironically, this concern has disappeared as I do more work in public. In Doing It: Women Tell the Truth About Great Sex, an anthology about sex, I wrote of how selfies can become graphic storytelling that not only builds intimacy but also an understanding of my sexuality and my sexual aesthetic pleasure. It is a power I never want to give up, so the book also contains a naked photo of me I had taken for a lover. It is a deliberate attempt to interrupt the means of production and also claim space within my sexuality, one that is defined by myself, not others.

When the photo was republished (with consent) by SBS, I wrote that “this is not some wishy-washy Stockholm syndrome masquerading as empowerment – there is ferocity in my choice”. It remains true today. By claiming my agency as an individual who feels pleasure and expression, I realise that confidence is not only crucial for my personal survival under patriarchy framed solely for men, but it is also a political act I can define as I choose. It makes me aware that my body, choices and actions are decided by me without reference to others’ expectations and that I contain greater complexity the roles of servant or victim that society allows.

Around this time, Mia Freedman wrote an article entitled ‘The conversation we have to have: Stop taking nude selfies’. Promoting the article on Twitter, Freedman wrote “taking nude selfies is your absolute right. So is smoking. Both come with massive risks.” In response, I took another naked selfie, but this time with a cigarette draped from my mouth and ‘fuck off’ written on my chest in black lipstick. I posted it everywhere without care because – again – my body, choices and actions are decided by me. I made the choice that and every day is that I will not have victims presented as complicit in their abuse. Because the fault will always be with the abuser, not the abused.

An act of power

Despite their conflicting emotions, publishing naked selfies taken in either arousal or anger are fearsome in their power. They are as much a rejection of victimhood as they are an opportunity for retribution. People can try to weaponise my body against me, but I will do it first and use it against them because I know its power.

This is why patriarchal structures and men condition women into submissive disempowerment. Women’s bodies are defined narrowly as vessels for pleasures and service for others, not ourselves. Such narrow and compliant definitions intentionally belie the power and complexity we contain.

Stories abound throughout history of the malevolent power of women’s bodies, so profound was male unease surrounding bloods and births. Women were told their vaginas ruined ship rope or their menstruation damned success. This was an admission women’s bodies were terrifying in their otherness but was also an excuse to contain them to the home rather than out in the community where they might gain power or control.

But history tells us many women believed in the power of their bodies. Balkan women would stand out in the fields, flashing their vaginas to the sky to quell thunderstorms. The Finnish believed in the magic of harakointi, using their exposed bodies to bless or curse on whim. Sheela-na-gigs (carvings of women often found in European architecture) embraced their power by spreading their labia, not to please or welcome men, but scare off evil. Women would lift their skirts to make others laugh in feasts for Roman gods and goddesses or lure lovers. More recently, women have exposed their bodies to protest petroleum in Nigeria or civil war in Liberia in acts of political, angry anasyrma.

Reframing the dialogue

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. Women are presented as passively-defensive vessels in a state of perpetual victimhood. We are tasked with hiding our shameful-yet-coveted nakedness from people who expect to see us but only under their strict conditions.

A truer representation is that power exerts in all manners of life, including how we sexually communicate as equal, consenting partners. The moral panic should focus on when power corrupts that balance and how to correct it, not how to maintain the same corruption.

Join us as on 18 September for an an intimate conversation with Sexologist, Nikki Goldstein and art curator Jackie Dunn to unwrap the ethical dimensions of being nude. Get your ticket to The Ethics of Nudity here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Join our newsletter

BY Amy Gray

Amy Gray is a Melbourne-based writer interested in feminism, popular and digital culture and parenting. follow her on twitter @_AmyGray_

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 28 APR 2019

The Ethics Centre (TEC) has often been called upon to assist sporting organisations with ethical crisis.

The Ethics Centre recently took advantage of an opportunity to discuss two recent cases regarding ethical sport dilemmas with a group of HR Sport Executives. It was an enlightening experience and we’d like to share it with you.

As a reminder, TEC undertook two high-profile reviews of sporting organisations over the last 18 months, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and Cricket Australia (CA).

The first of these explored the comparison between sportsmanship and the ‘pragmatic’ or even gamesmanship* approach to its administration. Bringing the two approaches was problematic and culminated in disenchantment, frustration and an organisational culture that neither represented the best of sport or organisational administration.

The Centre delivered a warts-and-all report with 17 recommendations, all of which were accepted. Recent discussions with AOC reveal a major shift in the culture of the organisation over the last 12 months, under the leadership of CEO Matt Carroll and the Head of People and Culture, Amie Wallis. AOC staff need to be congratulated for what they have achieved.

The other engagement was with Cricket Australia, a culture and governance review in response to the ball-tampering incident at the Newlands Ground in South Africa during an international test match in March 2018. It was clearly against the rules.

The initial attempts of the players to conceal what they were doing is testament to this. But it wasn’t as clean-cut as that. The incident seemed to represent an attack on something sacred to Australians. Many fans reacted as if they were personally afflicted.

Our interviews and surveys of CA staff, players, cricket officials, sponsors and members of the public often explored the difference between sportsmanship and gamesmanship. Comparisons were drawn between ball-tampering, sledging and the underarm bowling incident in 1981 during a One Day International cricket match between Australia and New Zealand.

We recently had the good fortunate of being invited to a discussion about such issues with a group of HR executives, representing some of the major professional sporting organisations in Australia, from Horse Racing to Rugby, organised by Mercer Australia.

And of course we accepted.

We put to them the observation that when there is fraud in government, the actions are often labelled corruption, as they signify a greater social betrayal than a breach of the law. Fraud in the private sector doesn’t attract the same moral outrage and avoids the ‘corruption’ label, with one exception: sport. Sport also uses the word ‘corruption’ to describe fraudulent behaviour. We asked why.

The group started with the suggestion that people take sport personally, as we all feel part of it and we all feel like we own it. We play it to pursue the best in us, we barrack for our team, we involve our children in it and we use it as a tool to teach our children about values, about what is important in life.

We all feel obliged to have an opinion about it, perhaps as Australians. This is probably why people feel fraud in sport is a moral issue that goes beyond compliance with the law, a social ‘evil’ that the word ‘corruption’ better conveys. There was also the feeling that corruption is used because it reveals the interconnected network that comes with fraud in sport.

When asked about the dilemmas in sport more broadly, many spoke about the challenge players experience balancing their need to win and earn income, with their long-term wellbeing.

Players often hide their injuries to avoid being dropped from teams. These injuries are often physical, but sometimes they are mental. The period where an athlete is most successful financially is narrow. The pressure to sacrifice their long-term health as a result is real.

As HR professionals they also spoke of their dilemmas, when they need to balance advocacy for the individual player with the best interests of the company or business side of the sport. They spoke of this also in relation to the management of the team, when the coach feels the need to let someone play because their family is present, even though it may not be in the best interest of a win.

They spoke about how officials are tempted to overlook bad leadership of team leaders when the characters themselves raise the winning morale of the team. Some spoke about the challenges of being considerate of a person’s background, but also being clear that it did not excuse bad behaviour such as sexual harassment.

We see related dilemmas in other sectors currently under the public spotlight. It is accepted that the unique relationship between sport and ethics has been neglected by philosophers.

There may be much to be learnt by our experience of sport, and how its values are brought to the wider theatre of life. These discussions help us reach a better understanding about these relationships.

* Gamesmanship is built on the principle that winning is everything. Athletes and coaches are encouraged to bend the rules wherever possible in order to gain a competitive advantage over an opponent.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethics in engineering makes good foundations

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

When you hire a philosopher as your ethicist, you are getting a unicorn

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Does Australian politics need more than just female quotas?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kate Prendergast 24 APR 2019

It began in Oakden. Or, it began with the implosion of one of the most monstrously run aged care facilities in Australia, as tales of abuse and neglect finally came to light.

That was May 2017. Two years on, we are in the midst of the first Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, announced following a recommendation by the Scott Morrison government.

The first hearings began this year in Oakland’s city of Adelaide. They have seen countless brave witnesses come forward to share their experiences of what it’s like to live within the aged care system or see a loved one deteriorate or die – sometimes peacefully, sometimes painfully – within it.

In May, the third hearing round will take place in Sydney. This round will hear from people in residential aged care, with a focus on people living with dementia – who make up over 50 percent of residents in these facilities.

With our burgeoning ageing population, the number of people being diagnosed with dementia is expected to increase to 318 people per day by 2025 and more than 650 people by 2056.

Encompassing a range of different illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and Lewy body disease, its symptoms are particularly cruel, dissolving intellect, memory and identity. In essence, dementia describes the gradual estrangement of a person from themselves – and from everyone who knew them.

It is one of the most prevalent health problems affecting developed nations today – and one of the most feared. Contrary to widespread belief, one in 15 sufferers are in their thirties, forties and fifties.

Physical restraints

How do you manage these incurable conditions? How can you humanely care for the remnants of a person who becomes more and more unrecognisable?

One thing the Royal Commission has made clear: you don’t do it by defaulting to dehumanising mechanisms of restraint.

Unlike in the UK or the US, there are currently no regulations around use of restraints in aged care facilities. It is commonly resorted to by aged care workers if a patient displays physical aggression, or is a danger to themselves or others.

Yet it is also used in order to manage patients perceived as unruly in chronically understaffed facilities, when the risk of leaving them unsupervised is seen to be greater than the cost of depriving them their free movement and self-esteem. The problem of how to minimise harm in these conditions is an ongoing and high-pressure dilemma for staff.

Readers may remember the distressing footage from January’s 7.30 Report, in which dementia patients were seen sedated and strapped to chairs. One of them was the 72-year-old Terry Reeves. Following acts of aggression towards a male nurse, he was restrained for a total of 14 hours in a single day. His wife, however, had authorised that her husband be restrained with a lap belt if he was “a danger to himself or others”.

Maree McCabe, director of Dementia Australia, is vocal about why physical restraints should only be used as a last resort.

“We know from the research that physical restraint overall shows that it does not prevent falls,” she says. “In fact it may cause injury, and it may cause death.”

While there are circumstances where restraint may be appropriate McCabe says, “it is not there as a prolonged intervention”. Doing so, she says, “is an infringement of their human rights”.

After the 7.30program aired and one day before the Royal Commission hearings began, the federal government committed to stronger regulations around restraint, including that homes must document the alternatives they tried first.

Restraint by drugging

Another kind of restraint which has come into focus through the Royal Commission is chemical restraint. Psychotropic medication is currently prescribed to 80 percent of people with dementia in residential care – but it is only effective 10 percent of the time.

“We need to look at other interventions,” says McCabe. “The first to look at is: why is the person behaving in the way that they are? Why are they responding that way? It could be that they’re in pain. It could be something in the environment that is distressing them.”

She notes people with dementia often have “perceptual disturbances” – “things in the environment that look completely fine to us might not to someone living with dementia”. Wouldn’t you act out of character if your blue floor suddenly became a miniature sea, or a coat hanging on the door turned into the Babadook?

“It’s about people understanding of what it’s like to stand in the world of people living with dementia and simulate that experience for them,” says McCabe.

Whether through physical force or prescription, a dependence on restraint shows the extent to which dementia is misunderstood at the detriment of the autonomy and dignity of the sufferers. This misunderstanding is compounded by the fact that dementia is often present among other complex health problems.

Yet, and as the media may sensationally suggest, the aged care sector isn’t staffed by the callous or malicious. It is filled with good people, who are often overstretched, emotionally taxed and exhausted.

Dementia Australia is advocating for mandatory training on dementia for all people who work in aged care. This covers residential aged care, but could also extend to hospitals. Crucially, it encompasses community workers, too.

“Of the 447,000 Australians living with dementia, 70 percent live in the community and 30 percent live alone,” notes McCabe. “It’s harder to monitor community care, it’s less visible and less transparent. We have to make sure that the standards are across the board.”

It is only through listening to people living with dementia – recognising that while yes, they have a degenerative cognitive disease, they deserve to participate in the decision-making around their life and wellbeing – that our approach to it has evolved. Previously, people believed that it was dangerous to allow sufferers to cook, even to go out unaccompanied.

Likewise, it is crucial that we continue to afford people with dementia the full rights of personhood, however unfamiliar they may become. Only then can meaningful reform be made possible.

Besides, if for no other reason (and there are many other reasons), action is in our own selfish interest. The chances, after all, that you or someone you love will develop dementia are high.

MOST POPULAR

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 22 MAR 2019

Play fair or play to win. The interests of an individual player versus the team. Bad leaders who get good results.

These are just some of the common ethical tensions occurring throughout elite Australian sport. And they lead to corruption.

The Ethics Centre undertook two high profile reviews of sporting organisations over the past 18 months, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and Cricket Australia (CA).

Australian Olympic Committee

Our AOC review explored the comparison between sportsmanship and gamesmanship. Sportsmanship is the fair, honest and decent treatment of others in competition. Gamesmanship, on the other hand, is built on the principle that winning is everything. Athletes and coaches are encouraged to plot, ploy and bend the rules wherever possible in order to gain a competitive advantage over opponents.

Bridging the two approaches was problematic. It culminated in disenchantment, frustration and an organisational culture within AOC that neither represented the best of sport or organisational administration.

The Ethics Centre delivered a warts-and-all report with 17 recommendations, all of which were accepted.

Recent discussions with AOC reveal a major shift in the culture of the organisation over the last 12 months, under the leadership of CEO Matt Carroll and the head of people and culture, Amie Wallis. AOC staff need to be congratulated for their achievements.

Ball tampering and Cricket Australia

The other engagement was with Cricket Australia – a culture and governance review in response to the ball tampering incident in South Africa in March 2018, something that was clearly against the rules.

Initial attempts by players to conceal what they were doing was testament to this, but it wasn’t as clean cut as that. The incident seemed to represent an attack on something sacred to Australians. Many fans reacted as if they were personally afflicted.

Our subsequent interviews and surveys with CA staff, players, officials, sponsors and members of the public often explored the difference between sportsmanship and gamesmanship.

Comparisons were drawn between ball tampering, sledging and the underarm bowling incident in 1981 during a One Day International cricket match between Australia and New Zealand.

Sporting HR executives

We recently had the good fortunate of being invited to a discussion about such issues with a group of HR executives, representing some of the major professional sporting organisations in Australia, from Horse Racing to Rugby, organised by Mercer Australia.

We put to them the observation that when there is fraud in government, the actions are often labelled corruption, as they signify a greater social betrayal than a breach of the law. Fraud in the private sector doesn’t attract the same moral outrage and avoids the label of corruption. But there is one exception. Sport also uses the word corruption to describe fraudulent behaviour. We asked why.

The group started with the suggestion people take sport personally, as we all feel part of it and like we own it. We play it to pursue the best in us, we barrack for our team, our kids play it, and we use it as a tool to teach our children about values and what is important in life. We feel obliged to have an opinion about it, perhaps as Australians.

This is probably why people feel fraud in sport is a moral issue that goes beyond compliance with the law, a social ‘evil’ that the word ‘corruption’ better conveys. There was also the feeling that corruption is used because it reveals the interconnected network that comes with fraud in sport.

When asked about the dilemmas in sport more broadly, many spoke about the challenge players experience balancing their need to win and earn income, with their long-term wellbeing. Players often hide injuries to avoid being dropped from teams. These injuries are often physical, and sometimes mental. The period where an athlete is most successful financially is narrow. This creates pressure to sacrifice long-term health.

As HR professionals they also spoke of their dilemmas, when they need to balance advocacy for the individual player with the best interests of the company or business side of the sport. They spoke of this also in relation to the management of the team, when the coach feels the need to let someone play because their family is present, even though it may not be in the best interest of a win.

They spoke about how officials can overlook bad leadership when the characters themselves raise the winning morale of teams. Some spoke about the challenges of being considerate of a person’s background, but also being clear that it did not excuse bad behaviour such as sexual harassment.

We see related dilemmas in other sectors currently under the public spotlight. It is accepted that the unique relationship between sport and ethics has been neglected by philosophers.

There may be much to be learned by our experience of sport, and how its values are brought to the wider theatre of life. These discussions help us reach a better understanding about these relationships.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights