Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Sometimes life can seem overwhelming. Often, it’s because we can’t help focusing on the bad stuff and forgetting about the good.

Don’t feel too bad. We’re hard-wired to be more impacted by negative events, feelings and thoughts than those things that are positive. Surprisingly, when experiencing two experiences that have equal intensity, we’ll get stuck on the negative rather than the positive.

This psychological phenomenon is called negativity bias, which is a type of unconscious bias. Unconscious biases are attitude and judgements that aren’t obvious or known to us but still affect our thinking and actions. They are often in play despite the fact we may consciously hold a different view. They’re not called unconscious for nothing.

This is an especially tricky aspect of negativity bias since we tend not to notice ourselves latching onto the negative aspects of any given situation, which makes preventing a psychological spiral all the more difficult.

We’ve all experienced how easy it is to spiral due to the one hater who pops up in in our Insta or Twitter feed despite the many positive comments we could be basking in. This is the pernicious power of negativity bias – we are disproportionately affected by negative experiences rather than the positive.

Remember that time a co-worker or friend said something irritating to you near the beginning of the day and it remained in your mind the whole day, despite other positive things happening like being complimented by a stranger and getting lots of work done? Of course you remember it. Because our memories are also drawn like a magnet to those negative experiences even when far outweighed by the positive experiences that surrounded it. You might have finished that day still feeling down because you hadn’t been able to forget about the comment, despite the day on the whole having been pretty good.

Something that’s been prevalent for the past two years is negativity around various COVID-19 measures. It’s easy for us to focus on the frustration of forgetting to take our mask with us somewhere or the inconvenience of constantly checking-in. Often these small things can linger in our minds or affect our moods, while small positive things will go almost unnoticed.

Negativity bias can also affect things outside our mood. It can affect our perceptions of people and our decision making.

It also causes us to focus on or amplify the negative aspects of someone’s character, resulting in us expecting the worst of them or seeing them in a broadly negative light. Assuming someone’s intentions are negative is a common way that arguments and misunderstandings occur.

It can also heavily affect our decision-making process, an effect demonstrated by Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who were groundbreakers in uncovering the role of unconscious bias. Over-emphasising negative aspects of situations can, for example, cause us to misperceive risk and act in ways we normally wouldn’t. Imagine walking down the street and losing $50. How does that feel? Now imagine walking down that same street and finding $50. How different does it feel to find, rather than lose $50? Kahneman used this experiment to show that we are loss averse – even though the amount is the same, most people will feel worse having lost something than having found something, even when it is of equal value.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. Research suggests that this bias comes from our early need to be attentive to danger, and there are various ways we can remain attentive to possible threats while stemming the effect of negativity on our mental state.

Minimising negativity bias can be difficult, especially when we focus on compounding problems, but here are a few things to remind ourselves of that can help combat negativity spirals.

- Make the most of positive moments. It’s easy to fall into a habit of glossing over small victories but taking a few minutes to slow down and appreciate a sunny day, or a compliment from a friend, or a nice meal can help to take the negative winds out of our sails.

- Actively self-reflect. This can include things like recognising and acknowledging negative self-talk, trying to reframe the way you speak about things to others in a more positive light and double-checking that when you do interpret something as negative that it is proportionate to the threat or harm it poses. If it’s not, take some time to reassess.

- Develop new habits. In combination with making an effort to recognise negative thought patterns, we can develop habits that help to counteract them. Pay attention to what activities give you mental space or clarity, or tend to make you happy, and try to do them when you can’t quite shake the negativity off. It could be as simple as going for a walk, reading a book, or listening to feel-good music.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Mehhma Malhi The Ethics Centre 27 SEP 2021

Recently, the Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, announced that Paralympians will be paid the same bonuses as Olympians.

Specifically, medalists that win gold will receive a $20,000 bonus, and those that win a silver or bronze will get $15,000, and $10,000 respectively. Remarkably, prior to this announcement Paralympians received no payment whatsoever for representing their country and for their incredible efforts.

In his speech, Morrison noted that the Paralympic team won a phenomenal 60 medals and described this achievement as having “national significance.” It appears that the exceptional performance of our Paralympians has prompted this change to the funding model. But while this is a welcome development and clearly a step in the right direction, the reasons for this shift in thinking and change in policy warrant further consideration.

Firstly, it seems unfair and perhaps reductive to award the Paralympic team equal compensation only if they perform exceptionally as a collective. The team only garnered support for its campaign because it won a large number of medals that surpassed the collective achievements of our Olympians. One can’t help wondering had they not done so well would the Government have recognised their achievements and made this change?

On the other hand, this cannot be the only reason for the change in position as no such bonuses were considered in 2016 when Paralympians won even more medals – 81 in total. Therefore, perhaps the decision reflects more the thinking of the incumbent government instead of a more pervasive bias?

Either way, it is evident that such stark differences in pay partly occur because of deep-seated discrimination and that in reality individuals in minority groups have to go the extra mile to ‘prove’ their worth. Additionally, whilst our Olympians and Paralympians compete for their country, there is an explicit recognition that their individual efforts are partly compensated by the monetary award. The lack of payment undermines this.

Curiously, the Australian Government sets aside more than $50 million for high-performance grants that support both Olympians and Paralympians. But the fact that this budget is shared makes it even harder to comprehend why it has taken so long to recognise this disparity and attempt to correct it. However, leaving aside for a moment the reasons why this has occurred, let’s consider what makes this form of pay discrimination inequitable from an ethical perspective. Broadly, there are two main reasons.

First, the pay bonus is not an additional sum of money that athletes receive on top of their salary. Instead, it is usually their primary source of income. In other words, it is not a bonus at all, and athletes that don’t receive any such grants or awards must rely heavily on family support or sponsorships following sporting events to sustain themselves. Therefore, in addition to being an ‘award’ that serves the purpose of providing open acknowledgement of achievement, the bonus is in fact a monetary necessity. Therefore, for Australia to preferentially award athletes competing in the Olympics suggests that Paralympians are regarded less favourably and may in some way be considered as less worthy.

If the difference arose purely due to insufficient funds and a limited budget, then the most equitable approach would be to share the bonuses and split them equally between the two groups of athletes. But this has clearly not been the stance adopted to date.

Instead, the bonuses are a clear example of pay discrimination and the marked inequity denies the Paralympians what they rightly deserve. After all, the Paralympians train and work just as hard as Olympians. Furthermore, finding appropriate training facilities and resources for athletes with disabilities is far more challenging and costly than it is for those without any limitations. Places with the necessary specialised equipment and ease of access are scarce. And so, if anything, the budget for the Paralympic committee should be larger not smaller.

Further, Paralympic athletes are subject to pay discrimination as they are denied chances to receive sponsorships. There ought to be additional enhancements put in place to ensure the success of Paralympians. Traditionally, the Paralympics have been broadcast at odd hours and the advertising leading up to them is comparatively modest. This is in part driven by a lack of advertising and compounded by broadcasting schedules and limited Paralympian visibility. This means that sponsors are less likely to partner with Paralympians and the majority never receive lucrative sponsorships that would not only help the promotion of them as a brand but also contribute directly and meaningfully to their finances.

For all these reasons, it is necessary that the government, advertising agencies, and Paralympic and Olympic committees examine these issues and devise means of alleviating the financial stress placed upon athletes. Currently, athletes who want to compete and succeed in their sports have no choice but to accept rewards that are below par. The most important reason however, as to why these issues need to be addressed is that the differential treatment of Paralympians perhaps undermines the core tenet of amateur sport – that competition should fair and open to everyone equally.

Paralympians should not be penalised just because they have a strong desire to represent their country and compete. The creation of the Paralympics was based on the need for equal opportunity – surely this should be reflected in how we recognise those that show courage in participation and excel.

Image credit: Nick Miller, Paralympics, London 2012

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Caitlin Roper The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2021

In a piece published here earlier this month, ethics teacher Georgia Fagan argued that violent pornography was not incompatible with feminism – that it could even be a ‘feminist choice’ compatible with ‘gender equality’. Naturally those of us who have engaged in this field for many years did a double-take.

Fagan argues that feminist efforts to dismantle the pornography industry deny the rights of female performers to “use their naked bodies for profit”. She claims such content represents a “celebration” of “emancipated female sexuality”.

The notion that violent pornography can be ‘feminist’ is evidence of one of two assumptions; that filmed acts of male violence against women for men’s sexual gratification can be a feminist endeavour, or that the violence done to women in the production of pornography does not count as violence. As feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon noted, pornography is a record of men’s violence against women. It is not fantasy, not speech, but acted out on the bodies of real women who are directly used to produce it – “what pornography does, it does in the real world”.

Mainstream pornography is the graphic, sexualised depiction of male dominance and female subordination. It eroticises men’s violence, aggression, cruelty, degradation and humiliation of women. It is hate speech, anti-woman propaganda and sexual terrorism against women. It dehumanises women as sexual objects existing wholly for men’s sexual use and abuse, as whores who love to be fucked, a set of hands and holes, as “cumdumpsters”. As such, feminists have argued that pornography – particularly, violent pornography – is at odds with women’s dignity, humanity and human rights.

Research bears this out. A 2010 content analysis of popular porn videos found that 88.2% of scenes contained physical aggression, and that perpetrators were usually male and the targets of their aggression overwhelmingly female. Research has also found pornography consumption is statistically significantly correlated with physical abuse (both victimisation and perpetration), sexual abuse (both victimisation and perpetration), acceptance of rape myths and negative gender equitable attitudes.

The defence of pornography as “empowering” for women is rooted in liberal ‘choice’ feminism, which is centred around individual empowerment rather than challenging power structures that harm women collectively. There is no recognition of women as a sex-class, with a shared condition or experience of oppression, and no acknowledgement of the social constraints under which women make choices. Rather than a collective movement to liberate women as a whole from oppression, ‘choice’ feminism serves to justify women’s participation in harmful and misogynistic practices at the expense of women as a class.

But focusing on individual women and their consent to male violence and abuse invisibilises those who perpetrate, produce, profit from and take pleasure in viewing it – men.

The reality is many women are seriously harmed in the production of pornography. They report experiencing violence and rape (as Stoya, the porn star Fagan quotes, has), coercion, exploitation, drug and alcohol abuse, trauma and suicidality. Some leave the industry after just months with irreparable damage to their bodies.

The mainstreaming and proliferation of pornography has not emancipated women and girls outside the industry who are forced to engage with men and boys who are regular consumers of it. In addition to a climate of sexual harassment, including daily requests for nudes and sexual moaning in the classroom by male classmates, young women and girls report feeling pressured to participate in painful, degrading and unwanted sex acts their male partners have seen in pornography. They report being expected to want to be choked, hit, have anal sex (coerced anal sex is rising) and to have their faces ejaculated on – the signature acts of the porn industry.

Young women have “unlimited rape stories”, documented in the thousands of accounts from Sydney students compiled by Chanel Contos. Recently at the consent roundtable she organised, domestic violence workers described the link between porn and violence against women, describing the majority of porn which depicts “aggressive, non-consensual, violent, and degrading behaviour.”

Violent pornography influences consumers’ sexual appetites, attitudes and practices and women and girls are paying the price – some even with their lives. A 2019 study from Indiana School of Public Health found that nearly a quarter of women in the US have felt scared during sex, having been choked without warning by their male sexual partners. UK-based campaign We Can’t Consent To This has documented at least 60 cases so far where women have been killed by men who have claimed it was due to “rough sex” or a “sex game gone wrong”.

While we support sexual consent education as a possible solution, better education around consent will have limited success when boys are being raised on and regularly masturbating to violent and misogynist pornography depicting women enjoying being degraded and brutalised.

“Either it is ethical and honourable to ‘play with’ and promote the dynamics of humiliation and violence that terrorise, maim and kill women daily, or it is not.”

As feminist researcher Rebecca Whisnant wrote of so-called feminist pornography, “Either it is ethical and honourable to ‘play with’ and promote the dynamics of humiliation and violence that terrorise, maim and kill women daily, or it is not.”

Violent pornography is the filmed abuse of women, and as such, both the production and consumption of it are fundamentally at odds with women’s human rights. It can only be defended if we accept that men’s sexual gratification is more valuable than women’s humanity.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Blame

In an age of ubiquitous media coverage on anything and everything, most people see blaming behaviour every day. But what exactly is blame? How do we do it? Why do we do it?

During the 2019-20 bushfires, the Prime Minister Scott Morrison was blamed for taking a vacation during an environmental crisis. During a peak in the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, protestors in Australia blamed individual police and the government at large for the historical and present violent mistreatment of First Nations people.

Maybe you still blame your overly angry high school teacher for making you an anxious person. Maybe you blamed your co-worker recently for standing you up on your weekly Zoom call.

Whatever the stakes, we are all familiar with blaming, but could you explain what it is?

At a very basic level, blame is considered a negative reaction that we have towards someone we perceive as having broken a moral norm, leaving us feeling wronged.

There are several theories of blame that explore different interpretations of how exactly it works, but an overarching distinction is that of how or whether it’s communicated.

On the one hand, we have communicative blame – this is the outward behaviour that indicates one person blames another for something. When we yell at someone for running a red light, scold a politician on social media, or tell someone we are disappointed with their actions, we are communicating blame. Sometimes blame can even be communicated subtly, in the small ways we speak or act.

Some people think that it’s necessary for blame to be communicated – that blame without this overt aspect isn’t quite blame. On the other hand, some people think that there can be internal blame, where a person never outwardly acknowledges that they blame someone for something but still holds an internalised judgement and emotion or desire – imagine someone who holds a grudge against a friend who moved across the world but doesn’t speak to them anymore.

When we think about blame, we have to ask ourselves why do we blame, what does it do and when is it ok?

A common answer looks towards history and especially religion. In the Bible, for example, blame is often seen to hold us to account and discourage dissent. Blame has often been (and is still) used as a social and political indicator of what’s acceptable to citizens and/or governments.

This is more obvious when we consider communicative blame. Take for example, the way that the Australian public and news media communicated their blame of the Prime Minister during his bushfire vacation. These expressions ranged from simply showing dissatisfaction, to more complex indications of a desire for change and a serious acknowledgement of a moral failing.

And it also goes the other way. During the 2021 daily COVID-19 press conferences, various politicians have been quick to communicate their blame towards various groups of people flouting public health orders.

But is this type behaviour always okay? Is it always effective? These are the kinds of questions ethicists ask and attempt to answer when thinking at things like blame. One way to think about these questions is to look at them through different ethical frameworks.

Consequentialism tells us to pay attention to the outcomes of our actions, dispositions, attitudes, etc. A consequentialist might argue that we shouldn’t communicate blame if it would cause worse consequences than if we kept it to ourselves.

For example, if a child does something wrong, a consequentialist might say that sometimes it’s better to not outwardly blame them and instead do something else. Perhaps give them the tools to fix the mistake or praise them for a different aspect of the situation that they did well.

Less intuitively, though, is the implication that sometimes it will be wrong to blame someone for something, even if they deserve it! Say you have a friend who is very contrarian and does the wrong thing on purpose to get attention. Some consequentialists might say that it is wrong to communicate blame to them because under these circumstances you’re encouraging the behaviour, since they want the attention of being blamed. This might be a frustrating conclusion for people who think others get what they deserve by being blamed.

A deontologist might help them here and say that if someone is blameworthy then they deserve to be blamed and it is our duty to blame them, regardless of the consequences. Some deontologists might say that as long as our intentions are good, then we have a responsibility to blame wrongdoers and show them their moral failing.

Some different issues arise with that. Does this mean we are obligated to blame someone who “deserves it”? What about in situations where blaming would have really bad consequences? Is it still our duty to blame them for their wrongdoing?

Next time you go to blame someone, think about your intentions and what you are hoping to achieve by taking that action. It might be that you’re better off keeping it to yourself or finding a more positive way to frame the situation. Maybe the best consequences are to be gained by blaming or maybe you do just deserve to get that frustration off your chest.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Normativity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Exercising your moral muscle

Exercising your moral muscle

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 8 SEP 2021

Day-to-day decisions carry more weight in the context of the pandemic.

Previously simple choices like whether or not to go to the shops are now shadowed by dire consequences, and the act of constantly weighing up those consequences can lead to ‘moral fatigue’.

“This is the kind of wearing down of a person who is constantly making ethical decisions in conditions of fundamental ambiguity,” Ethics Centre executive director Dr Simon Longstaff recently told the ABC.

“It’s the sense of the weight of your decision that can be the source of the fatigue.”

Much like physical exercise, Dr Longstaff says there are ways to exercise our moral muscle so that it becomes stronger. Our choices matter because of the cumulative effect they have, and if exercised every day, building up moral fitness can also help prevent moral injury and its effect on our mental health.

Here are four ways to exercise your moral muscle and help with decision-making:

- Build a support system of friends and family members around you who are open to the conversation. Nobody can be expected to know exactly what to do in any given situation, but having a support system of peers, friends and family to bounce ideas off and get perspective can be invaluable.

- Is there urgency to the problem? If not, setting it aside for a period of time and going for a walk can help with clarity. “Allowing a bit of time and literally going for a walk is one of the really good things you can do,” Dr Longstaff says. “It’s amazing how much just walking helps things just sort out in your own mind.”

- All muscles need time to recover, so factor in rest days to help manage mental exhaustion and take time to do something you enjoy. “Think creatively about ‘what makes me happy in life? What are the things that I really love doing, that I find relaxing?’,” researcher and psychologist Professor Jolanda Jetten told the ABC. “We know that feeling in control is a very good predictor of good health, physical and mental. People should think of ways they can encounter situations and contexts where they feel fully in control, where they don’t have to worry.”

- If all else fails, or you’re not sure who to talk to, make a booking with the Ethics Centre’s hotline Ethi-call and speak with a qualified counsellor to help shape your perspective and find a pathway that’s right for you.” A service like Ethi-call helps you become really clear about the facts of the matter,” Dr Longstaff says. “Most importantly, what it does is give you the ability to shape your perspective so you can see the problem from different angles, and in that you might open up an option that never occurred to you that resolves the situation.”

Free, independent helpline Ethi-call provides guidance and support to anyone facing a difficult ethical dilemma or decision. Book a call with a qualified counsellor here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Social media is a moral trap

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Violent porn and feminism

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan The Ethics Centre 1 SEP 2021

Does pornography, especially violent pornography, contribute to gender-based violence, and if so, is censorship the answer? Or can the pornographic industry coexist with the drive towards gender equality?

We occupy a world plagued by sexual and gender-based violence. The United Nations declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) asserts that such violence need be recognised as “a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women”.

Globally in 2017, 219 women were killed each day by either a member of their own family or by their own intimate partner. Debates about the complex causes of such violence and reasons for the persistence of gender inequality remain. The role that pornography may play in both the maintenance and propagation of these harms is one of many factors considered relevant to the debate. Specifically, ethicists are needed to address the question: Could pornography and feminism be compatible bedfellows after all?

Renowned feminist philosopher Catherine Mackinnon argues that pornography “works as primitive conditioning”, meaning that its content is likely to inform the desires and subsequent actions of its viewers. Mackinnon asserts that if pornographic images are violent, this is likely to result in unwanted sexual violence being inflicted onto others by pornography’s consumers.

Contemporarily, debate and disagreement persist regarding how pornography should be managed for adult audiences.

Various philosophers and feminist theorists, such as Mackinnon, argue in favour of some form of criminal action being taken against certain types of pornography due to its capacity to harm women. In 1983, Mackinnon, alongside feminist writer and activist Andrea Dworkin, brought forward an Antipornography Civil Ordinance which proposed that pornography needs to be treated as a violation of women’s civil rights. The pair aimed to remove the freedom of speech protections pornography had been granted under United States law. The ordinance was ultimately struck down by the courts.

Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

To this day, feminists remain largely divided over MacKinnon’s antipornography ordinance. Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

Calls to dismantle the industry of pornography are often taken to be synonymous with feminist action. In such cases, this action is thought to be the best means of protecting women from an industry rife with exploitation. Similarly, calls to cease pornographic productions are often thought to serve the function of preserving women’s dignity by allowing them to avoid careers centred around sexual objectification.

However, demands for censorship or a general production shutdown of pornographic films are also calls to severely limit the career opportunities and subsequently the financial resources of pornographic actresses. Doing so may risk further degrading these workers’ rights. The profitability and questionable legality of the porn industry often permits it to function below industry standard, resulting in inadequate worker protections being extended to porn actors and actresses.

Stoya is a female adult entertainer who has spoken openly about a form of feminism which she worries hates both sex work and pornography. She is concerned that female sexuality is only being embraced within narrow margins, neglecting the possibility that hardcore pornography may empower women, both actresses and viewers, rather than degrade them. Stoya argues that a contemporary feminism which celebrates women’s right to work and earn an independent wage is flawed if it simultaneously rebukes women who freely choose to perform in pornography to acquire that wage. For Stoya, performing in hardcore pornography (produced under fair working conditions) does nothing to degrade the status of female performers. Rather, it stands as a celebration of a tirelessly campaigned for and emancipated female sexuality.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared. Doing so puts these women at increased risk of assault and exploitation out of fear their allegations will not be trusted or that they will meet with legal consequences. Stoya herself brought forward rape charges against famous male pornstar James Deen, and she holds that the remedy to such injustices lies in improving workers’ rights and the legislative systems surrounding the industry of pornography, rather than in trying to shut down the industry altogether.

This lack of regulation constitutes an injustice far greater than the supposed, yet largely unarticulated, harm of women being free to use their naked bodies for profit. The mere existence of agential and passionate hardcore pornographic actresses importantly signals the beginnings of a world where women’s bodies are no longer policed in ways which unjustifiably align sex with shame and exploitation.

So long as the porn industry is made to function on par with other industry’s standards, there is no reason to consider the bodies of female pornographic actresses anymore degraded, or exploited, than non-pornographic actresses, tradespeople, or frontline healthcare workers.

Calls to censor or morally condemn pornography are often less concerned with the rights of pornographic actresses and more with the potentially negative impact pornography has on its consumers. There are concerns, for example, that viewing violent pornography may increase sexual assault rates, a causal link which is yet to be definitively established. However, even if particular depictions of women’s bodies were found to increase the likelihood that men assault women, it is not immediately apparent that the desirable solution would be to forbid those depictions.

This censorship style solution shares particular characteristics with victim blaming culture, in which victims are blamed for the actions of perpetrators. In both victim blaming and pro-censorship anti-porn positions, the onus of change is placed on those who are determined to be the cause of any given injustice. The pornographic actress, for example, is told she cannot continue to do her work, instead of alternative interventions being sought which target perpetrators who may have been inspired by viewing particular pornographic depictions. We do not think it suitable to tell women to wear more clothing to stop men raping them; why should matters of pornography be handled any differently?

There are more desirable, alternative solutions to address contemporary issues of misogyny. First is the formation and endorsement of a safe and responsible pornography industry where the agency and security of actors and actresses is guaranteed. Unfortunately there will always be room for exploitation and abuse, however, these risks can be mitigated by extending workers’ rights and fair working conditions to pornographic actors in the same way such rights are endowed to workers in other industries.

Content subscription service Onlyfans stands as a site moving the pornography industry in this direction by allowing performers greater control over their content and income. OnlyFans allows performers to safely and independently produce pornographic content. However, the platform hasn’t avoided trouble for hosting adult content: Onlyfans recently announced it would be banning explicit content in a bid to attract investors, only to reverse its decision within a week after outcry from users.

Ongoing periphery interventions are also required to address gender-based violence and gender inequality more generally, such as improved sex education curriculums which provide more comprehensive education on consent and respectful relationships to school age children.

Interventions such as bolstering the regulatory bodies surrounding pornography and improving sex-ed curriculums allows societies to place adequate accountability on those who commit or are at risk of committing acts of violence against women. These interventions should be favoured over those which risk undermining the agency of both female performers and consumers of pornography.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality. Theorists and feminists alike need to engage in critical discourse regarding where the onus of change need be placed. The porn industry, pornographic actresses and perpetrators of violence against women are all potential targets of this change. The decisions we make regarding what actions should be taken will determine whether or not pornography is compatible with contemporary feminism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 AUG 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we believe ethics is a collaboration – a conversation between diverse people trying to figure out how to act, live and make good decisions.

This means we need a range of people participating in the conversation, of all ages. Thanks to our donor, Chris Cuffe AO at Third Link Investment Managers, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Daniel Finlay to Youth Engagement. Daniel is a graduate from the University of Sydney with a Bachelor of Arts and Science (Hons) and a Postgraduate Certificate in Publishing. He also received Class I Honours for his thesis in ethical philosophy. To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

Tell us, what attracted you to philosophy?

My first philosophy-related class was called Bioethics and I actually took it because I had come back from a break and couldn’t continue my psychology units until the next semester. But from the moment I left the first tutorial, I knew this was where I would end up going. The unit was practical ethics with a focus on humans and their bodies. The topics we covered ranged from black-market organ selling to sex work to people suffering from body integrity identity disorder (BIID). The BIID discussion particularly made me realise how many questions we have to face that simply don’t have neat or obvious answers. BIID is a very rare disorder where a healthy person very strongly desires to amputate one or more of their limbs. And here we were, a group of fresh-faced 19-year-olds, trying to figure out what the hell to do with that information.

That sounds like an interesting place to start. Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions. How are you dealing with it and what do you hope we’ll be able to bring out the other side?

Honestly, I’m part of the lucky few who haven’t been too flipped around by the lockdowns. I do very much miss rock climbing and have admittedly fallen back into lazy habits without it, but on the whole I can deal with being at home very easily because that’s where I like to spend most of my time regardless.

I’m hoping that we all come out of this with a bit more patience. COVID has obviously slowed a lot of things down for a lot of people. Media content is coming out slower, packages are constantly delayed, work projects put on the back-burner. Hopefully most people come out the other side of this with the realisation that most things aren’t as urgent as they sometimes seem, and a little patience when dealing with fellow humans can go a long way.

With all that time at home, you must have developed some guilty pleasures during the pandemic. Can you share one with us?

I wish I had something quirky or funny to share but the sad reality is my guiltiest pleasure is just watching TikToks at midnight in bed instead of getting a reasonable night’s sleep.

Pretty sure that you aren’t alone there. So, what does a standard day in your life look like?

Mostly playing games, watching Netflix/YouTube and managing an online Discord community I run. At the moment, I’m researching how, when and why young people engage with ethics in their lives and offering a younger perspective on a range of projects. Whenever I find the energy, I do try to make time for reading (I’ve recently gotten back into some fantasy novels), walking, listening to podcasts, rock climbing, writing and annoying my cat, Panda.

Let’s wrap up close to home. What does ethics mean to you and why are you interested in bringing it to the attention of young people?

To me, ethics is about learning to live with ourselves in a way that is sustainable. Part of that process is learning how to question ourselves, other people, systems and structures. It’s about identifying assumptions and patterns in our beliefs and behaviours and learning to discard or modify the unfounded ones.

I’m interested in bringing it to a younger audience because I think studying ethics and critical thinking is such an important part of developing the cognitive resources needed to make significant change in the world in a responsible and empathetic way. I’ve already seen firsthand, from being a Primary Ethics teacher, the immense good that this can do, so if I can help bring these resources into the brains of passionate teenagers then I think the world will be much better off.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2021

When big decisions loom, it’s often easy to get stuck ruminating all the possible ways to proceed, how it might go wrong, or get confused by taking on too much external advice and input.

Of all the ways you might act, which is the best? Which of all the possibilities should you choose?

Putting ethics at the centre of your thinking can help. It offers a framework for evaluating life’s difficult decisions, which invariably involve questions about what’s good and what’s right.

These five steps can help you move toward a solution that is in alignment with your purpose, values and principles.

1. Check in with your body

Take a moment to drop into your body. Often, we rush headlong into considering without pausing to reflect on how we feel. Our emotions play a major role in our decisions – both consciously and unconsciously. Stop for a moment and pay attention to your feelings; what are they telling you about what matters most?

You may not unlock immediate clarity, and that’s ok. Just begin by recognising and labelling the emotions that arise. Often these feelings are a compass pointing you to what matters most to you.

2. Question your assumptions and identify the facts.

Often when we feel uncertain, it’s because we are lacking information that is required to make a considered decision. What do you know about the choice in front of you? Write down all the facts that you know about your options.

Now test your thinking. Is there anything you are assuming to be true that may not be? Bracket fears or other people’s opinions for a moment and just focus on what you know to b be true. Be aware of jumping to any conclusions around the circumstance, people involved or potential outcomes.

By looking at the situation more objectively, you can identify what you actually know, and what you need to know. Now ask yourself: do you have all the facts and information that you need to make an informed decision? If there are gaps, write a list of the questions you need answers to, and seek the information that you need to have more factual data to consider.

3. Consider how the options relate to your values.

It’s time to get clear on what matters most to you. That is the key to unlocking your values. Our values are like signposts, they indicate what’s most important to us. It can help to consider the situation through the lens of what you consider most ethically relevant, starting with values that matter most to you such as honesty, transparency, kindness, or integrity. Your values also reflect what you stand for, desire or seek to protect, such as financial security, freedom, creativity, family or community for example.

4. What are the lines you won’t cross?

Next, bring into consideration your principles. If values are the signposts, then principles are the guide rails that keep us on track. They apply to the pursuit of many different types of goals and help when values conflict with one another. Principles can’t be selectively applied. Once adopted, they apply to every decision.

You may value success but not lying or cheating is a solid principle to guide how you achieve success.

You might have just a handful of principles that you personally live by. Check in to make sure that the decision you make doesn’t cause you to cross any of those guide rails.

5. Decide on what matters, and why.

Unpack all of the reasons you might decide in each way and with all of the information on the table – rule out any option that moves you away from your purpose, values and principles, and ultimately, seek out the decision that best aligns with them.

Decision-making is complex at the best of times. But sometimes life can present us with a choice where there is no right option – or where both pathways are wrong. When those moments strike it can feel impossible to find a pathway forward.

You don’t have to navigate it alone. Ethi-call is a free helpline designed to provide structured support and guidance through those very difficult decisions.

Appointments are with trained ethics counsellors who take you through a series of questions that will help clarify the situation and shine a light on what is most important to you.

Make a booking at www.ethi-call.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 29 JUN 2021

Decisions are a part of being human. But that doesn’t mean they are easy.

Whether big or small, when a choice creates an ethical conflict, or where no option feels right, the path forward can seem out of sight.

These three philosophical concepts are designed to help deliver clarity in complexity. Next time you find yourself facing a dilemma, try running it through each of these to shed new light on the scenario.

The Golden Mean

When you’re trying to work out what the virtuous thing to do in a particular situation is, look to what lies in the middle between two extreme forms of behaviour (the middle being the mean). The mean will be the virtue, and the extremes at either end, vices. One end will usually be an excess, the other end a deficiency.

For example, in a situation that requires courage, there may be one extreme where you might act recklessly, and the other, do nothing out of cowardice. The virtuous response is the mean between these two.

The Sunlight Test

This test a simple way to test an ethical decision before you act on it. Ask yourself: ‘Would I do the same thing if I knew my actions would end up on the front page of the newspaper tomorrow?’

By imagining if your decision – and the reasons you made it – were public knowledge, we must consider our willingness to stand by that choice in a public forum.

Would you be proud of the action if people you most admire knew what you’d done and why? Would you be able to defend your choice? Would other people agree, or at least understand, why you did what you did?

This simple thought exercise helps give clarity on your motivations – so you can see clearer whether the choice is motivated by what is good or right, or by self-interest, reward, external pressures or opinions.

Plato’s Cave

One well known thought experiment is Plato’s allegory of the cave. It goes like this. Prisoners are chained up facing a wall deep within a cave. A fire behind them casts just enough light for them to see images upon the wall, which have been cast by puppeteers. Knowing no alternative, the prisoners believe what they see and hear to be the whole reality.

As the Philosopher John Locke said, “No man’s knowledge here can go beyond his experience”. When faced with a decision, consider the day-to-day experiences, lessons, conversations and modelled behaviour that is shaping what you believe to be ‘reality’.

Are shadow puppets (bias) driving your actions? Can you step outside your own projections on the wall to consider new perspectives and ideas? Can you separate truth from fiction? By challenging the things you believe to be true in any scenario you can make sure that your assumptions hold up to scrutiny.

Still stumped: Ask yourself these three questions:

What are your duties and responsibilities in this situation and to whom?

What counts as a good outcome and how will you know?

What would the wisest person you know say to do in this situation?

Ethi-call is a free helpline designed to provide structured guidance through life’s most challenging dilemmas. If you, or a loved one are facing a decision that leaves you with a bad feeling and no right way out, a conversation can help.

Appointments are with trained ethics counsellors who take you through a framework of prompts and questions that will help clarify the situation and shine a light on what is most important to you.

Make a booking at www.ethi-call.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

Love has historically played a big role in how we understand the task of treating other people well. Many moral systems hold that love is foundational to doing right.

The Bible, for example, commands us to “love thy neighbour” – not merely to respect or value them, but to love them. Thousands of years later, philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch wrote that “loving attention” is the core of morality.

In our contemporary understanding of the word, love seems to involve partiality. In all kinds of settings from romantic love to the love in friendship or familial love, loving people seems to mean not loving others. We love our wife, not our neighbours’ wife. We love our friends and our parents, not our boss’ friends or our bus drivers’ father.

In fact, we might think that someone does not love their spouse in any meaningful sense of the word if they also say they love all other people equally – the celebrated essence of love seems to involve choosing some people over others.

This partiality affects our actions as well as our emotions: our parents, friends, and spouses receive more prioritisation, gifts, and emotional attention from us than strangers. This is a celebrated and joyful feature of human life.

Could love in fact be immoral – or amoral? Could behaving lovingly and behaving ethically be two separate tasks – tasks that might sometimes come into conflict?

Morality, has often been thought of as essentially neutral. That is, the moral gaze looks at everyone as equals; not favouring one person over another simply because of our relationship with them. Kantian ethicists, for instance, hold that all people deserve ethical treatment simply because they are persons.

Anyone who is a person deserves to have others not lie to them, disrespect them, enslave their body or seize their property. Thus, the only thing the moral gaze is concerned with is whether someone is a person – and since all people are persons, the moral gaze looks upon all of us equally.

Consequentialist ethics contains a similar commitment to neutrality. For a consequentialist, the moral measure of an action is whether it maximises value. Whose value is maximised has no special claim to our attention; the more value, the better, whether it accrues to my mother or to yours. Since the moral gaze looks to creating the most happiness, it looks at all people equally – as equal vectors of possible happiness.

If morality contains a commitment to neutrality – and if love contains a commitment to partiality – then the moral gaze and the loving gaze might conflict. It might even be the case that love demands acting in ways that morality seems to forbid.

Imagine that you are on a ship which begins to sink. You have held onto the railing but other passengers have not been so lucky, and in the water before you are several strangers struggling to stay afloat. Also in the water, struggling alongside the strangers, is your wife. Are you permitted to throw your wife the one remaining life jacket? Or is her right to life no stronger than any of the strangers’? Love seems to demand that we save our wife, but morality, if it is neutral, seems to offer no automatic reason why we should.

The philosopher Bernard Williams saw a way out of this puzzle. He argued that any person standing on the boat in this situation, who starts thinking about what morality demands, might reasonably be charged with having “one thought too many”. The person should not think “my wife is in the water – what does morality require I do?”. They should simply think “my wife is in the water,” and throw the life jacket.

Williams’ view was that a morally good person is not always thinking about what is morally justifiable. Perhaps, counterintuitively, being a truly ethical person means not always looking through the moral gaze. The question still remains – do love and morality ask us for different things?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

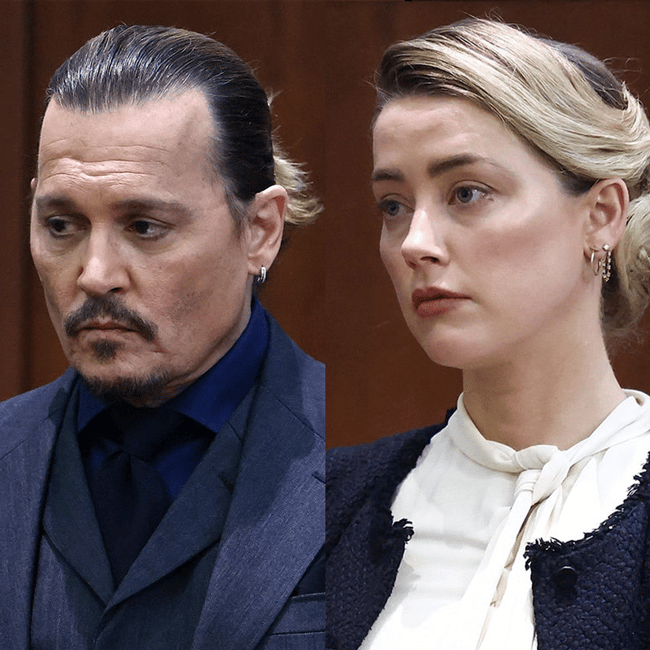

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why we find conformity so despairing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture