Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 23 MAR 2020

Many Australians are encountering the phenomenon of rationing for the first time in their lives. For the moment, rationing is sporadic and confined to items like toilet paper and beans. However, how will we respond when rationing moves from consumables to life itself?

Given the finite number of beds in intensive care units, respirators, etc. in Australia, the harsh truth is that if there is mass contagion, giving rise to critical illness on a broad scale, there will not be enough medical resources to sustain the lives of all who need care.

In those circumstances, medical staff and families will need to exercise triage – put simply, the practice of prioritising access to scarce medical resources. Not everyone will be chosen. Some of those at the end of the line will die.

This is the harsh reality behind abstract talk of ‘flattening the curve’. Governments and their advisers are now working to reduce the number of COVID-19 infections in the hope that they can prevent the overloading of our limited resources. In doing so, they recognise that the risks cannot be overcome by throwing money at the problem.

There is an upper limit in terms of equipment and trained personnel – there is just not an endless supply of either and no amount of money can solve that problem once the number of people seeking care exceeds the effective places available.

That is why every person must now do what they can to minimise the risk of mass infection. Doing so may not confer an individual benefit. However, the decision to wash one’s hands regularly and practice prudent forms of social distancing may make all the difference when it comes to avoiding the tipping point between a medical system that can cope and one that is forced to engage in triage.

So, how will clinicians choose if the worst fears are realised? In medical ethics, the general approach to triage is to prioritise according to two dimensions. First, a patient will be assessed in terms of their physical capacity to respond to the treatment that is available. Put simply, the less likely a person is to respond to medical care, the lower they will be ranked on the list. In a time of scarcity, there is little justification for devoting precious resources to cases that are judged to be futile.

Second, a patient will be assessed in terms of their relative circumstances – including age, stage of life, etc. For example, a forty year old parent of three children will rank higher than a seventy year old with no dependents. Both principal factors intersect – and will be qualified (to some degree) by secondary concerns – such as the relative burden of any proposed treatment on the patient.

If the worst predictions come true, such choices may need to be made on a daily basis. It will not only be the doctors who have to decide. Families will also be drawn into the decision making process. Should that time arise, it will be essential that we all embrace some fundamental distinctions. For example, there is a profound difference between preserving life on the one hand and merely extending the process of dying, on the other.

The medical technology used in both cases is the same. It is the ethical discernment that makes the difference. If pressure mounts on intensive care units, then we can expect more families and loved ones to be asked if continuing treatment is not only futile but also denying another person a chance of life. Who of us is prepared for such a conversation?

None of this is meant to suggest that some lives are intrinsically more valuable than others. They are not – we are all equal in our possession of fundamental dignity. Nor does resort to triage imply indifference to the wellbeing of those who cannot receive life saving care. Those who miss out will be given the most compassionate care available as they die. Nobody need suffer.

Finally, we should spare a thought for those who may be called to make these difficult decisions. The physical, emotional and spiritual toll will be immense.

No amount of reason or decision making aids can prevent the abrasive effects on the human psyche of triage. Medical professionals, families, members of the wider community … we will all need support.

I hope that we can avoid arriving at a point where such decisions have to be made. It is the job of government to ensure that we are protected from such times. Whether they have done enough, early enough is yet to be decided.

In the meantime, if ever you wondered about the relevance of ethics to everyday life – just look around you.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Double-Effect Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 20 MAR 2020

In Mitch Albom’s best-selling novel, Five People you Meet in Heaven, a man named Eddie dies.

His entry into heaven is a reckoning: Eddie must meet with five people who had a significant impact on his life, or on whom he had a significant impact. Of the five people Eddie meets, only two are known to him; three are strangers.

The premise seems implausible at first. Surely, the people we spend the most time with – those we love and share our time and energy with – are the ones we impact, and are impacted by, most. However, what Albom’s novel reveals is a truth we all accept but frequently fail to live by: the fact that, as philosopher Carol Gilligan puts it: “we live on a trampoline – if we move, it affects a whole lot of people.”

The reason we fail to live by this basic truth is because so many people are invisible to us. We’ll never share their joys, hear their pain or witness their suffering. They could lead lives of utter bliss or abject misery and we’d never know. This leads us to assume that if we don’t know about them, then we can’t affect them, and vice versa.

Of course, this is nonsense – and we’ve never had so striking an example as we do now, wrestling with how we respond to the novel coronavirus and the threat of COVID-19. Most of those who are threatened by this virus are invisible to us. We’ll never know their names or see their faces. We’ll never know most of the people who miss out on groceries because of our actions at the supermarket, or who have taken our fair share in a moment of selfish desperation.

Despite the fact we all know the ties that bind us together extend further than our eyesight does, it seems clear that many are still struggling to see how that applies during a pandemic. We have seen cases in Australia of people placed in isolation ducking out for a trip to the shops, exposing others to immense risk, people flagrantly disregarding advice around social distancing and isolation and welfare recipients expected to continue to fulfil ‘mutual obligations’ despite it placing them at risk of infection.

How do we account for the gap between what we know – that we’re connected to one another – and the way that so many of us are behaving?

It takes moral imagination to remember the people we can’t see – to give them fair representation in our weighing up of how we should act.

But that imagination can be stymied because it butts heads with a competing force, that unsurprisingly, comes from economics: moral hazard. Whilst moral imagination asks us to apportion our attention, care and concern to those who are most at risk; moral hazard thinking encourages us to offset as much of our own risk onto others as possible.

Moral hazard thinking allows us to justify a quick sojourn to grab a coffee, despite having been in contact with person who is suspected of being infected. Moral hazard thinking that allows us to be wilfully blind to the effects on the community that stem from hoarding essentials. There are personal gains to be had by putting ourselves ahead of everyone else – but the fact that so many are succumbing to the temptation is perhaps a measure of how far we have to go to arrive at a point where, as poet Mary Richards described it, we can open our “moral eye” to see what – and crucially who – really matter.

Richards believes poetry and literature can provide a pathway to opening the moral eye. Other research attributes moral imagination to childhood and upbringing; experience of diversity; a sense of safety and communal security and face-to-face encounters with those who we’re failing to consider.

However, each of these pieces of research is about developing moral imagination. We should also take a second to think about what’s required to put it into practice. For so many of us, the fact we don’t remember the people we can’t see isn’t due to lack of ability, it’s because we’re choosing to look away. We have a nagging sense, in the corner of our mind, that there’s someone else we could consider – someone whose perspective would force us to change our behaviour. And it’s easier to turn away.

But true moral imagination – and moral redemption – lies on the other side of looking. It begins when we dare to understand the other person as having a claim against us. We need to accept them as people who can burden us with their needs, and who do – and should – rely on us. As philosopher Eleanor Gordon-Smith recently wrote:

“We have to start caring about strangers, richly caring – caring in the way that makes us prepared to put their wellbeing before our own. What will unite us right now, and God knows we could use it, is finally seeing each other as worth making sacrifices for.”

In The Five People You Meet in Heaven, the last person Eddie meets is a child – a civilian caught in a war zone in which Eddie was a soldier. Eddie set fire to the building where she was burned to death. For his entire life, he knew he’d seen a shadow moving and suspected there was someone there, but never indulged the thought. He decided instead to turn away. Until at last, at the end of his life, he finally faces her – and permits himself to see what he did to her. Instead of turning away, he bears witness to what he’s done. And in doing so, he’s not only redeemed of the guilt, he’s able to see himself anew.

After the war, Eddie worked in maintenance for an amusement park. After parting ways with his ‘fifth person’, having shown the courage to face what he’d done and who he’d harmed, he is then able to recognise all the lives he’s saved. Surrounding him in heaven are countless faces – all people who lived because of his ordinary, quiet work. People he never met, would never know, but who lived because of what he did.

This is the pivot that our moral imagination requires of us. We shouldn’t see the social distancing, isolation, quarantine, travel bans and the host of other impositions on our behaviour as frustrations or burdens to be resented and worked around where possible. We should see it as an opportunity to rescue people. To save their lives.

Even though they’ll never know our names or see our faces, grandkids will be given a Christmas with a grandparent they never knew was at risk; someone will receive a piece of advice they never would have heard; a cancer patient will make it to the end of therapy and learn they’re cancer-free.

It seems easier to turn away from the uncomfortable truth. To focus on the risks and benefits to us without bearing in mind the possible effects on the unseen masses.

But doing so makes our world so small. It robs them of the community care and support they deserve, and it robs us of a richer way of thinking about ourselves and our relationships with others.

Call it a circle of life, a trampoline, a moral community or whatever you will. Just have the courage to see it for what it is: a demand and an opportunity to be better.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 20 MAR 2020

For the parents of school age children, the coronavirus pandemic presents challenging ethical decisions.

On one hand, all available medical evidence suggests ordinarily healthy children are at no risk of harm from COVID-19. While they can present with minor symptoms if infected, there’s believed to be no lasting injury. The nation’s formally appointed medical advisers have advised that schools should stay open, at least for now. Despite this, there’s considerable agitation amongst parents facing this decision, a number are already voting with their feet by not sending their kids to school.

The situation is made more difficult for parents thanks to contrary medical advice from credible informal sources. Likewise, parents are wrestling with apparent conflicts in policy settings – indoor gatherings of 100 or more are deemed hazardous (500 if outdoors), and we’re implored to adhere to social distancing, yet schools are deemed to be exempt from these restrictions.

Part of the problem is that governments are seen to be lacking transparency around why these contradictions exist. So, many parents are left to wonder if their children and their families are being asked to bear risks for the sake of others – and to do so without any opportunity to consent to the role they are being asked to play.

So, what should parents do? Here are some questions we can ask ourselves:

-

What are the facts?

Have I sought information from the most authoritative sources, not just those with the loudest voice or widest following? Am I listening to those specifically qualified to speak on the matter or am I sifting information to suit my pre-existing preferences (what we know as confirmation bias)?

-

Do my children and family matter more than others?

Does my duty to my immediate family take precedence over obligations to all others in my wider community, including relative strangers? Who will bear the ultimate burden of my decision? For example, some of the reasons for the government wanting schools to remain open are to allow emergency workers with children to attend to their duties and to help prevent the economy from shutting down due to employees being diverted to child-caring duties. All of this confers benefits on wider society.

-

Am I claiming a privilege I don’t deserve?

what would I decide if I found myself in the position of the most vulnerable person in society? Not everyone has the same choices in life. For example, the very wealthy will often be able to afford a period without employment income, while others will struggle to meet the most basic needs. So, is the option to withdraw your child from school something that you can ‘afford’ to do – but not others with fewer financial resources, or less support, more generally?

-

Is fear distorting my judgement?

Am I misjudging the real level of risk? And in doing so, am I discounting the opportunities for my children? For example, has the school put in place hygiene measures and the monitoring and testing of symptoms as part of their regime? Does that offer an environment that is only marginally less safe than your home – especially if you and other family members still intend to come and go from the house, as required from time to time?

-

Am I being proportionate in my response?

Am I considering opportunities as well as risks, and weighing them up in a manner that allocates appropriate weight to each? In making this assessment should the interests of society as a whole be given priority? For example, if the risks to my children and family are very low, but the effective costs of my decision on others are very high, have I good enough reasons to explain to others why my small gain is worth their large level of pain? If your decision to withdraw your child tips the school into closure, will you be imposing a burden on others that they cannot afford to bear?

-

What are my ‘non-negotiables’?

Are there certain decisions that I would regret making for the rest of my life? For example, if your child did become infected at school – could you live with the fact that you had allowed exposure? Would it matter so much if you knew that infection would have only minor consequences for the child? Likewise, could you live with yourself or another family member being exposed to risk of infection due to your child attending school?

-

How might history judge my decision?

Would an independent and unbiased judge find the decision you make wanting? Indeed, would you remain confident in your choices if you know it would be a leading news story in the months or years to come? Imagine people in the future considering your decision and its motivations. Would they endorse those choices, given the information and options that are available to you now?

-

Are there creative alternatives that would resolve the dilemma?

Is it possible to reconcile competing interests by proposing a novel solution? For example, could society close schools while making alternative arrangements for the safe care of the children of people working in essential services. Is it possible to maintain a flourishing economy while whole families work from home for extended periods?

There are no ready-made answers to ethical dilemmas. As such, ethics does not demand an illusory form of ethical perfection. Reasonable people can and do disagree about the answers to challenging ethical questions – such as how best to respond to the emergence of COVID-19. That is fine – especially in circumstances where the best option available is simply the ‘least bad’. All that ethics requires is that, as a minimum, we stop and think, tie our decisions back to an explicit framework of values and principles and make a conscientious judgement of how competing interests should be ranked in our estimation of what it is right and good to do.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

How to live a good life

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 MAR 2020

One of the most difficult decisions an employer will ever have to make is whether or not to dismiss employees during an economic downturn.

Invariably, those at risk of losing their jobs are competent, hard-working and loyal. They do not deserve to be unemployed – they are simply the likely victims of circumstances.

As one employer said to me recently, “I hate the idea of having to be ruthless – but I need to sack forty to save the jobs of four hundred”. So, what are the key ethical considerations an employer might take into account?

-

Save what can be saved

There is no honour in destroying all for the sake of a few. Even the few will eventually perish in such a scenario.

-

Give reasons

Be open and truthful. Throw open the books so that people can see the proof of necessity.

-

Retain the essential

Some people are of vital importance to the life of an organisation. However, when all other things are equal, protect the most vulnerable.

-

Cut the optional

The luxuries, the ‘nice-to-haves’ should not be funded. Use income for the essential purpose of preserving jobs.

-

Treat everyone with compassion

Both those who leave and those who remain will be wounded by the decisions you make – no matter how necessary.

-

Share the pain

consider offering everybody the opportunity to work less hours, for less money, in order to save a few jobs that might otherwise be lost.

-

Seek volunteers

If sacrifices must be made, invite your colleagues to be part of the decision. Some might prefer to step down – their reasons will vary. Honour their choice.

-

Honour your promises

If you have made a specific commitment to a member of staff, then you are bound by it – even in a crisis – unless it is impossible to discharge your obligation.

-

Minimise the damage

Those who lose their jobs should not be abandoned. How can they be supported by means other than a salary?

-

Look to the future

Make sure that your organisation has a purpose that can inspire those who remain – and justify the losses suffered during the worst of times.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethics of making money from JobKeeper

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 13 MAR 2020

In the sixteenth century, a cool thing to do if you were a political philosopher was to contrast human beings in society, with human beings as they would be if there were no society.

This thought experiment, performed by Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan, paints a pretty bleak picture of humanity. Hobbes described his picture of the “state of nature” – a world without society as:

“A time of war, where every man is enemy to every man… there is no place for industry… no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

This bleak picture of humanity – a time where people would clash and war over their own interests, with no hope for co-operation or camaraderie – is precisely why Hobbes thought we needed the state.

Nobody wants to live in the state of nature; it sucks. Instead, we all hand over a portion of our power to the state, who then create a world where everyone can get by and, ideally, flourish.

And, as a bonus, with a state to run the show, we can start to think about things like justice, ethics and morality. In the state of nature, Hobbes surmised these wouldn’t exist. He writes:

“The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law, where no law, no injustice. Force, and fraud, are in war the cardinal virtues.”

I can’t help but think of Hobbes at the moment, as I wander through supermarkets empty of supplies. I imagine the swollen pantries, garages and bathrooms across Australia, stockpiled in preparation for a pandemic that threatens us all. Individuals are scrambling for resources, squirrelling away supplies and taking care of their own interests first. It sounds a lot like we’ve reverted back to our nasty, brutish nature.

That probably wouldn’t surprise Hobbes. His state of nature isn’t meant to describe an actual period in human development; it’s a philosophical ghost story. It’s not a story about who we are, but who we might be if there were no law, order or state to restrain us.

Despite this, we should reflect on how, irrespective of all the social infrastructure Australia seems to offer, we’ve seen self-interest dominate on such a grand scale. The panic buying, hoarding, racism and at times scapegoating responses all demand interrogation.

How can this happen? How, in a time when we do have notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, can parents – OK, this parent – be scrambling around supermarkets looking for children’s pain medication for his teething daughter to no avail? How can wipes and nappies be in such short supply? When Hobbes envisioned the ‘war of all against all’, he didn’t envision the goal to be a clean bum in a time of crisis – yet here we are.

Three Australian women fight over toilet paper. pic.twitter.com/EAhErm4QaD

— DailyMirror (@Dailymirror_SL) March 8, 2020

We can perhaps find an answer, and some guidance, in the work of fellow social contract philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau thought Hobbes hadn’t gotten to the nub of the issue. The problem with the state of nature wasn’t lawlessness. Rather, it’s the belief that people live in perpetual competition to one another. Hobbes introduces the state to stop us from killing each other as a way of getting ahead, but he leaves in place the source of the problem: the mindset that we need to “get ahead” of one another.

Instead, Rousseau spent an enormous amount of energy discussing what he called “the general will”. This was his fix to Hobbes’ problem. To stop people from acting in competition to one another his idea was simple: decisions should be made with reference to what the whole of society, willing together, would support as a good idea. This way, nobody would be permitted to take more common resources than they needed, or was deemed fair under the circumstance. This way, no individual could have undue influence over society.

Imagine that. Imagine what happens if people rock up at the supermarket and think: what does everyone need right now? Imagine a mindset, a society and a marketplace where mutual obligation, care and concern were the primary motivators instead of self-interest. Imagine how much more – or less – toilet paper you’d have now. Imagine how much more sleep I’d have if my daughters teething pain could be medicated.

Unfortunately – and tellingly for us today – Rousseau told us that many societies would be unable to develop a sense of the general will if individuals lacked the virtue to set aside their personal self-interest.

However, I think Rousseau is being unfair here. Virtues aren’t practiced in a vacuum, they’re enabled or disabled by the context and the environment. And our society allows an enormous space where people are permitted – and encouraged – to pursue their own self-interest without regard for others. The market.

The influence of the market on, and at times over, the state is conspicuous in trying to understand why our shelves are so bare. When we act in the market, we act as consumers. And as consumers, there is only one rule: consume. If that everyone else misses out, so be it. Like Hobbes’s state of nature, the laws of consumption have no sense of right or wrong, justice or injustice.

Ethically, what’s required of us is to step into an environment of consumption without becoming consumers. Instead it requires us to maintain ourselves as citizens, who have concern for those around us and are eager to act in the shared interest and common good of all.

In part, it’s on us as individuals, not to leave our humanity and morality at the door of the supermarket. But it’s also on the market to more clearly align itself to the general will. Corrections that prevent overbuying toilet paper are an obvious step in that direction, but it’s akin to howling at the moon. The panic will shift to another product, and soon we’ll be playing whack-a-mole with a panicked consumer population who see their own security and comfort in competition with that of other people.

At times when we’re threatened and feel unsafe, our instinct is to batten down the hatches. However, that’s a game that guarantees there will be winners and losers. If we can find a way to see beyond ourselves, to pass a roll of paper under the stall to a neighbour, we might just find a way to get through this together.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 MAR 2020

The response to the novel coronavirus COVID-19 (now called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2) has been fascinating for a number of reasons. However, two matters stand out for me.

The first matter concerns the way that our choice of narrative framework shapes outcomes. From what we know of SARS-CoV-2 it is highly infectious and produces mortality rates in excess of those caused by more familiar forms of coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold. However, given that ‘novelty’ and ‘danger’ are potent tropes in mainstream media, most coverage has downplayed the fact that human beings have lived with various forms of coronavirus for millennia.

The more familiar we are with a risk, the more likely we are to manage it through a measured response. That is, we avoid the kind of panicky response that leads people to hoard toilet paper, etc. We can see how a narrative of familiarity works, in practice, by comparing the discussion of SARS-CoV-2 with that of the flu.

John Hopkins reports that an estimated 1 billion cases of flu (caused by a different type of virus) lead to between 291,000 and 646,000 fatalities worldwide each year. That is the norm for flu. Yet, our familiarity with this disease means that the world does not shut down each flu season. Rather than panic, we take prudent measures to manage risk.

I do not want to understate the significance of SARS-CoV-2, nor diminish the need for utmost care and diligence in its management. This is especially so given human beings do not possess acquired immunity to this new virus (which is mutating as it spreads). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 is currently thought to generate mortality rates greater than most strains of the flu.

However, despite this, I wonder if society would have been better served by locating this new virus on the spectrum of diseases affecting humanity – rather than as a uniquely dangerous new threat.

This brings me to the second matter of interest that I think worth mentioning. Like many others, I have been struck by the universal commitment of Australia’s leading politicians to legitimise their decisions by relying on the advice of leading scientists.

I do not know of a single case of a politician refusing to accept the prevailing scientific consensus. As far as I know, there has been nothing said along the lines of, “all scientific truth is provisional” or “some scientists disagree”, etc. I have not heard politicians denying the need to take action because it might put some jobs at risk. Nor has anyone said that action is futile ‘virtue signalling’ because a tiny nation, like Australia, can hardly affect the spread of a global pandemic.

As such, I have been left wondering how to explain our politicians’ commitment to act on the basis of scientific advice when it comes to a global threat such as presented by SARS-CoV-2 – but not when it comes to a threat of equal or greater consequence such as presented by global warming.

Taken together – these two issues raise many important questions. For example: are we only able to mount a collective response under conditions of imminent threat? If so, is this why politicians so often play upon our fears as the means for securing our agreement to their plans? Does this approach only work when the risks can be framed in terms of our individual interests – and perhaps those of our immediate families – rather than the common good? Or, more hopefully, can we embrace positive agendas for change?

For my part, I still believe that people are open to good arguments … that they can handle complex truths – if only they are presented in accessible language by people who deserve to be trusted. It’s the work of ethics to make this possible.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 6 MAR 2020

A virus knows no race. It is indifferent to your religion, your culture and your politics. All a virus ‘cares about’ is your biology … For that, one human is as good as any other.

Despite this, it’s easy enough to find recent reports of Australians experiencing discrimination for no reason other than their Chinese family heritage.

Such attacks are examples of racism – the irrational belief that an individual or group possesses intrinsic characteristics that justify acts of discrimination. That this is occurring is not in doubt.

For example, Australia’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Brendan Murphy has seen enough of such behaviour to make explicit reference to the phenomena, labelling xenophobia and racial profiling as “completely abhorrent”.

Professor Murphy’s position is one of principle. However, there is also a practical aspect to his admonition. Managing the risks of an outbreak of a pathogen like the novel coronavirus COVID-19 requires health officials and the wider community to make rational choices based on an accurate assessment of risk. Racism is irrational. It distorts judgement and draws attention away from where the risks really lie. Ethically it is wrong. Medically, it is idiotic and dangerous.

This rise in racism, prompted by the emergence of COVID-19, reveals how thin the veneer of decency is that keeps latent racist tendencies in check. It seems that, given half-a-chance, the mangy old dog of Sinophobia is ready to raise its head, no matter how long it has laid low.

Of course there is nothing new about Sinophobia in Australia. Fear of the ‘yellow peril’ is woven through the whole of Australia’s still-unfolding colonial history. Many factors have stoked this fear, including: persistent doubts about the legitimacy of British occupation of an already settled continent, ignorance of (and indifference to) Chinese history and culture, the European cultural chauvinism that such ignorance fosters, the belief that numerical supremacy is, ultimately, a determining force in history, the need to find scapegoats when the dominant culture falters, and so on.

Whatever the historical cause of this persistent fear, the present ‘trigger’ is the inexorable rise of China as an economic and military super power – a power that is increasingly inclined to demand (rather than earn) deference and respect.

The situation is made more volatile by the growing tendency for the China of President Xi Jinping to link its power and success to what is uniquely ‘Chinese’ about its history and character. Add to this a broadly accepted Chinese cultural preference for harmony and order and the nation is often presented as if it is a ‘monolithic whole’ – not just in terms of its autocratic government but in its essential character.

Unfortunately, all of this feeds the beast of racist prejudice. Those who feel threatened by the changing currents of history seize on even the flimsiest threads of difference and use these to weave a narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’ – in which others are presented as being essentially and irremediably different. This is the racists’ central trope – that difference is more than skin deep! Biology makes you one of ‘us’ or you are not.

It’s nonsense. Yet, it’s a nonsense that sticks in some quarters, especially during times of uncertainty such as this; when the general public is feeling betrayed by the elites, when institutions have lost trust and have weakened legitimacy and when increasing numbers of people fear for their future and that of their families.

Unfortunately, tough times provide fertile ground for politicians who are willing to derive electoral dividends by practising the politics of exclusion. It is a cheap but effective form of politics in which people define their shared identity in terms of who is kept outside the group.

It is far harder to practise the politics of inclusion – in which disparate groups find a common identity in the things they hold in common. This too can work, but it takes great energy and superior skills of leadership to achieve this outcome. Yet, it is the latter approach that Australia must look for, if only as a matter of national self-interest.

This is because racist attacks against Australians of Chinese descent also have a significant national security dimension. As I have written elsewhere, social cohesion is a vital component of a nation’s ‘soft power’ when defending against foes who covertly seek to ‘divide and conquer’.

The risk of such attacks is increasing as the world drifts back to a pre-Westphalian strategic environment in which the international, rules-based order breaks down and nations freely interfere with the domestic affairs of their rivals. In these circumstances, the last thing Australia needs is deepening divisions based on spurious beliefs about supposed racial deliveries.

Those who create or exploit those divisions wound the body politic, weaken our defences and undermine the public interest.

All of that said, it is important not to overstate the dimensions of the problem. Australia is a notable successful multicultural nation where harmonious relations prevail. This is despite there being an undercurrent of racism that has been more or less visible throughout Australia’s modern history.

Racism is never justified. Not by the fact that it is found to the same degree in other societies, and not even when its manifestation is rare. Although it offers little comfort, it should also be acknowledged that discrimination is as much a product of other forms of prejudice concerning religion, gender, culture, etc.

We have the capacity to do and be better. This is a choice we can and should make for the sake of our fellow citizens – whatever their background – and in the interests of the nation as a whole.

So, given that China is not likely to take a backwards step and Australians of Chinese background cannot (and should not) disguise their heritage, how should we respond to the latest bout of Sinophobia?

Attack prejudice with fact

A first step should be to follow the example of Australia’s Chief Medical Officer and attack prejudice with the facts. Professor Murphy’s example showed how facts about medicine can be deployed to calm fears and neutralise racist myths. This approach should be extended to other areas. For example, more should be known of the long history and extraordinary contribution of Australians of Chinese heritage.

This account should not merely tell the story of elite performance, economic contribution, etc. It should also speak of those who have fought in Australia’s wars, built its infrastructure, educated its children, nursed its sick … and so on. In short, we need to see more of the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Reframe the narrative

Second, we need to reframe the narrative about China and the Chinese. Today, most commentary portrays China as both a security threat and an economic enabler. It is both. However, this is only a small part of the story.

For the most part, we see little of the life of the Chinese people. We are largely ignorant of the achievements of their remarkable civilisation. One might think that the closeness of the economic relationship might be a positive factor. However, regular reporting about Australia’s economic dependence on China, is not helping the situation.

I know that this will seem counter-intuitive to some. However, the more we speak of Chinese students propping up our universities, of Chinese tourists sustaining our tourism industry and of Chinese consumers boosting our agricultural exports … the more it makes it sound as if the Chinese are little more than an economically essential ‘necessary evil’ – a ‘commodity’ that comes and goes in bulk.

This view of the Chinese negatively influences attitudes towards Australia’s own citizens of Chinese descent. Fortunately, a solution to the ‘commodification’ of the Chinese is at hand, if only we wish to embrace it. The large number of Chinese students who study in Australia offer an opportunity to build better understanding and stronger relationships.

Unfortunately, the Chinese student experience in Australia is reported not to be as positive as it should be. Too many arrive without the English language skills to engage more widely with the community. Too many find themselves lonely and isolated. Too many find solace in sticking with those they know and understand. With some justification, large numbers feel as if they are little more than a ‘cash cow’.

Invest in ethical infrastructure

Third, we need to invest in Australia’s own ‘ethical infrastructure’ – much of which is damaged or broken. We need to repair our institutions so that they act with integrity and merit the trust of the wider community. We need to work on the core values and principles that underpin social cohesion.

Part of this task must be to come to terms with the truth about the colonisation of Australia. This is not to invoke the ‘black arm band’ view of history. The truth is both good and bad. However, whatever its character, our truth remains untold. I sincerely believe that Australia’s ‘soft power’ is weaker than it would otherwise be, if only we could address this unfinished business.

Alleviate fear

Fourth and finally, the measures outlined above will be ineffective unless we also name the latent fears of average Australians. People across the nation want these ‘bread and butter’ issues to be acknowledged and addressed:

- How safe is my job?

- If I lose my current job, will I find another?

- If I can’t find another job, how will I pay my bills?

- Will I be cared for if I get sick?

- Will my children get an education that equips them to live a good life in the future?

- Can I move about with relative ease and efficiency?

- How will the nation feed itself?

- Are we safe from attack?

- Who can step in cases of natural disaster or man-made calamity?

- Why are our leaders not held to account when we are?

- Why can’t I be left alone to do as I please?

- Who cares about me and those I care about?

Failure to speak to the truth of these deep concerns leaves the field wide open for the lies of those who would stoke the fires of racism.

Unravel the complexities of the political relationship between China and Australia at ‘The Truth About China’, a panel conversation at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Saturday 4 April. Tickets on sale now

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why compulsory voting undermines democracy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Danielle Harvey The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

When we settled on Town Hall as the venue for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) 2020, my first instinct was to consider a choir. The venue lends itself to this so perfectly and the image of a choir – a group of unified voices – struck me as an excellent symbol for the activism that is defining our times.

I attended Spinifex Gum in Melbourne last year, and instantly knew that this was the choral work for the festival this year. The music and voices were incredibly beautiful but what struck me most was the authenticity of the young women in Marliya Choir. The song cycle created by Felix Riebel and Lyn Gardner for Marliya Choir embarks on a truly emotional journey through anger, sadness, indignation and hope.

A microcosm of a much larger phenomenon, Marliya’s work shows us that within these groups of unified voices the power of youth is palpable.

Every city, suburb and school has their own Greta Thurnbergs: young people acutely aware of the dangerous reality we are now living in, who are facing the future knowing that without immediate and significant change their future selves will risk incredible hardship.

In 2012, FODI presented a session with Shiv Malik and Ed Howker on the coming inter-generational war, and it seems this war has well and truly begun. While a few years ago the provocations were mostly around economic power, the stakes have quickly risen. Now power, the environment, quality of life, and the future of the planet are all firmly on the table. This has escalated faster than our speakers in 2012 were predicting.

For a decade now the FODI stage has been a place for discussing uncomfortable truths. And it doesn’t get more uncomfortable than thinking about the future world and systems the young will inherit.

What value do we place on a world we won’t be participating in?

Our speakers alongside Marliya Choir will be tackling big issues from their perspective: mental health, gender, climate change, indigenous incarceration, and governance.

First Nation Youth Activist Dujuan Hoosan, School Strike for Climate’s Daisy Jeffery, TEDx speaker Audrey Mason-Hyde , mental health advocate Seethal Bency and journalist Dylan Storer add their voices to this choir of young Australians asking us to pay attention.

Aged from 12 to 21, their courage in stepping up to speak in such a large forum is to be commended and supported.

With a further FODI twist, you get to choose how much you wish to pay for this session. You choose how important you think it is to listen to our youth. What value do you put on the opinions of the young compared to our established pundits?

Unforgivable is a new commission, combining the music from the incredible Spinifex Gum show I saw, with new songs from the choir and some of the boldest young Australian leaders, all coming together to share their hopes and fears about the future.

It is an invitation to come and to listen. To consider if you share the same vision of the future these young leaders see. Unforgivable is an opportunity to see just what’s at stake in the war that is raging between young and old.

These are not tomorrow’s leaders, these young people are trying to lead now.

Tickets to Unforgivable, at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Saturday 4 April are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Sunlight Test

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

BY Danielle Harvey

Danielle Harvey is Festival Director of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. A curator, creative producer and director, Harvey works across live performance, talks, installation, and digital spaces, creating layered programs that connect deeply with audiences.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

This is what comes after climate grief

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Ketan Joshi The Ethics Centre 21 JAN 2020

I can’t really lie about this. Like so many other people in the climate community hailing from Australia, I expected the impacts of climate change to come later. I didn’t define ‘later’ as much other than ‘not now, not next year, but some time after that’.

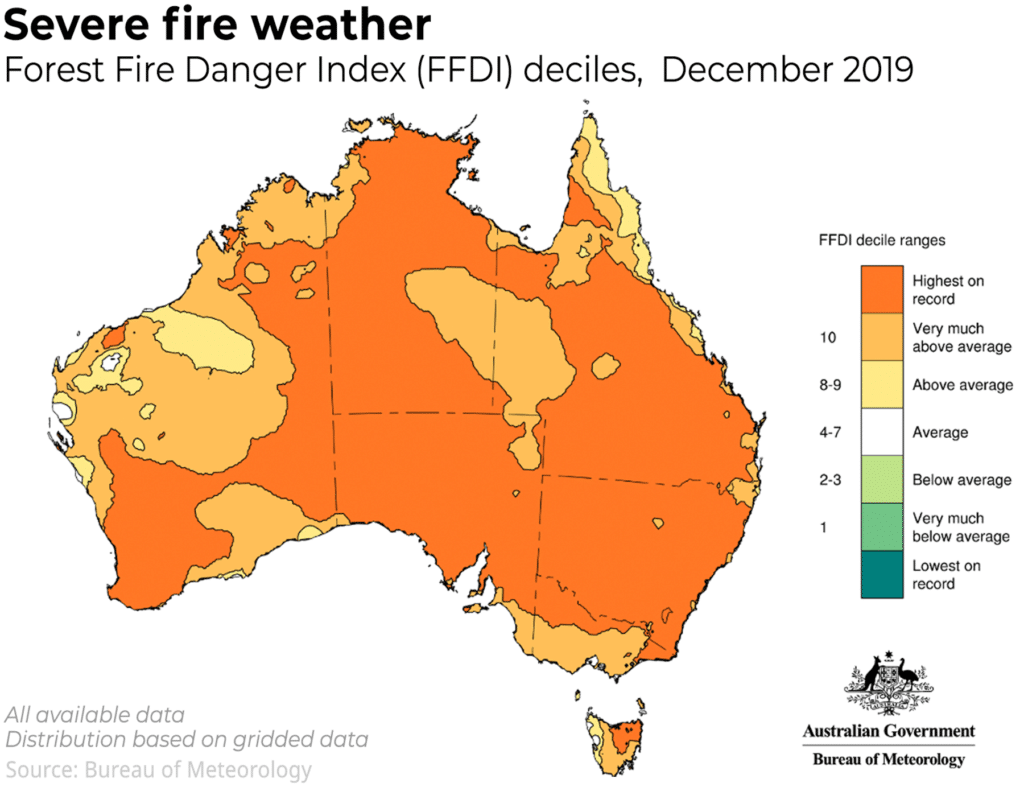

Instead, I watched in horror as Australia burst into flames. As the worst of the fire season passes, a simple question has come to the fore. What made these bushfires so bad?

The Bureau of Meteorology confirms that weather conditions have been tilting in favour of worsening fire for many decades. The ‘Forest Fire Danger Index’, a metric for this, hit records in many parts of Australia, this summer.

The Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub is unequivocal: “Human-caused climate change has resulted in more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires in recent decades for many regions of Australia…These trends are very likely to increase into the future”.

Bushfire has been around for centuries, but the burning of fossil fuels by humans has catalysed and worsened it.

Having moved away from Australia, I didn’t experience the physical impacts of the crisis. Not the air thick with smoke, or the dark brown sky or the bone-dry ground.

But I am permanently plugged into the internet, and the feelings expressed there fed into my feed every day. There was shock at the scale and at the science fictionness of it all. Fire plumes that create their own lightning? It can’t be real.

The world grieved at the loss of human life, the loss of beautiful animals and ecosystems, and the permanent damage to homes and businesses.

Rapidly, that grief pivoted into action. The fundraisers were numerous and effective. Comedian Celeste Barber, who set out to raise an impressive $30,000 AUD, ended up at around $51 million. Erin Riley’s ‘Find a Bed’ program worked tirelessly to help displaced Australians find somewhere to sleep. Australians put their heads down and got to work.

It’s inspiring to be a part of. But that work doesn’t stop with funding. Early estimates on the emissions produced by the fires are deeply unsettling. “Our preliminary estimates show that by now, CO2 emissions from this fire season are as high or higher than the CO2 emissions from all anthropogenic emissions in Australia. So effectively, they are at least doubling this year’s carbon footprint of Australia”, research scientist Pep Canadell told Future Earth.

There is some uncertainty about whether the forests destroyed by the blaze will grow back and suck that released carbon back into the Earth. But it is likely that as fire seasons get worse, the balance of the natural flow of carbon between the ground and the sky will begin to tip in a bad direction.

Like smoke plumes that create their own ‘dry lightning’ that ignite new fires, there is a deep cyclical horror to the emissions of bushfire.

It taps into a horror that is broader and deeper than the immediate threat; something lingers once the last flames flicker out. We begin to feel that the planet’s physical systems are unresponsive. We start to worry that if we stopped emissions, these ‘positive feedbacks’ (a classic scientific misnomer) mean we’re doomed regardless of our actions.

“An epidemic of giving up scares me far more than the predictions of climate scientists”, I told an international news journalist, as we sat in a coffee shop in Oslo. It was pouring rain, and it was warm enough for a single layer and a raincoat – incredibly strange for the city in January.

She seemed surprised. “That scares you?” she asked, bemused. Yes. If we give up, emissions become higher than they would be otherwise, and so we are more exposed to the uncertainties and risks of a planet that starts to warm itself. That is paralysing, to me.

It is scarier than the climate change denial of the 2010s, because it has far greater mass appeal. It’s just as pseudoscientific as denialism. “Climate change isn’t a cliff we fall off, but a slope we slide down”, wrote climate scientist Kate Marvel, in late 2018.

In response to Jonathan Franzen’s awful 2019 essay in which he urges us to give up, Marvel explained why ‘positive feedbacks’ are more reason to work hard to reduce emissions, not less. “It is precisely the fact that we understand the potential driver of doom that changes it from a foregone conclusion to a choice”.

A choice. Just as the immediate horrors of the fires translated into copious and unstoppable fundraising, the longer-term implications of this global shift in our habitat could precipitate aggressive, passionate action to place even more pressure on the small collection of companies and governments that are contributing to our increasing danger.

There are so many uncertainties inherent in the way the planet will respond to a warming atmosphere. I know, with absolute certainty, that if we succumb to paralysis and give up on change, then our exposure to these risks will increase greatly.

We can translate the horror of those dark red months into a massive effort to change the future. Our worst fears will only be realised if we persist with the intensely awful idea that things are so bad that we ought to give up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conservatism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The ethical price of political solidarity

BY Ketan Joshi

Was a speaker at IQ2: It's too soon to ditch fossil fuels. He is a science communicator with over eight years experience across The Monthly, Gizmodo, Cosmos and with the CSIRO.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Extending the education pathway

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

In the course of 2019, The Ethics Centre reviewed and adopted a new strategy for the five years to 2024.

The key insight to emerge from the strategic planning process was that the Centre should focus on growing its impact through innovation, partnerships, platforms and pathways.

We focus here on just one of those factors – ‘pathways’ and, in particular, the education pathway.

The Ethics Centre is not new to the education game. To this day, the establishment of Primary Ethics – which teaches tens of thousands of primary students every week in NSW – is one of our most significant achievements.

As Primary Ethics continues to break new ground, we feel it’s time to bring our collective skills to bear along the broader education pathway.

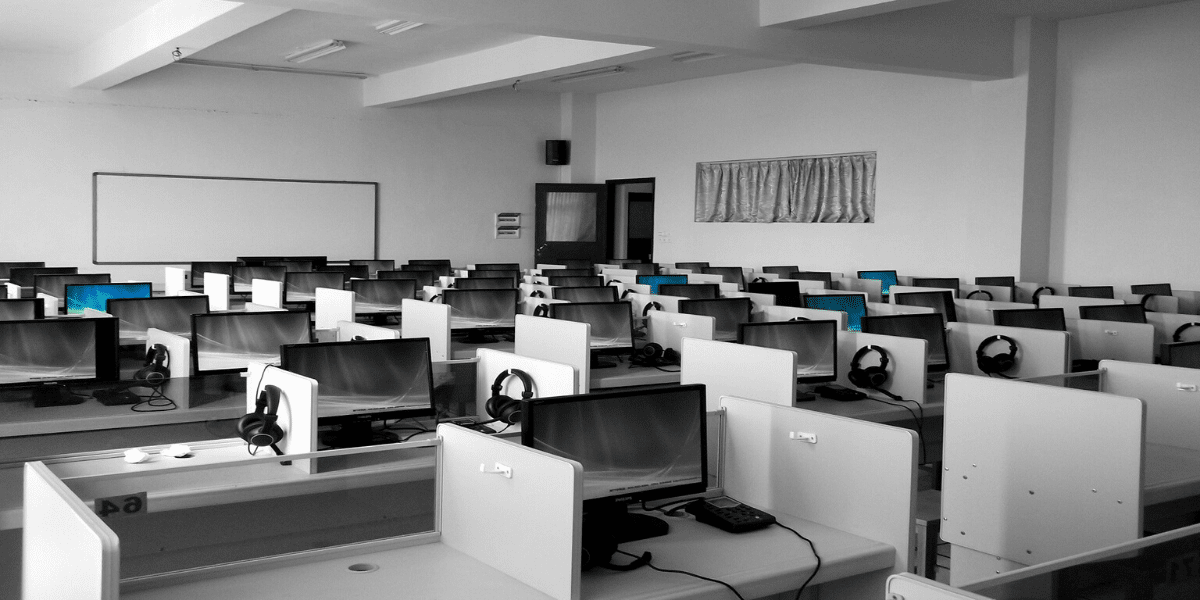

With this in mind, we’re delighted to report that The Ethics Centre and NSW Department of Education and Training have signed a partnership to develop curriculum resources and materials to support the teaching and learning of ethical deliberation skills in NSW schools, including within existing key learning areas.

This exciting project will see us working with and through the Department’s Catalyst Innovation Lab alongside gifted teachers and curriculum experts – rather than merely seeking to influence from the outside.

In addition, we have also formed a further partnership with one of the Centre’s Ethics Alliance members, Knox Grammar School. This will involve the establishment of an ‘Ethicist-in-residence’ at the school, the application of new approaches to exploring ethical challenges faced by young adults, and the development of a pilot program where students in their final years of secondary education undertake an ethics fellowship at the Centre.

In due course, we hope that the work pioneered in these two partnerships and others will produce scalable platforms that can be extended across Australia. Detailed plans come next, and we believe the potential for impact along this pathway is significant.

We believe ethics education is a central component of lifelong learning – extending from the earliest days of schooling through secondary schooling, higher education and into the workplace.

The broadening of the education pathway therefore provides new opportunities for The Ethics Centre and Primary Ethics to work together – sharing our complementary skills and experience in service of our shared objectives, for the common good.

If you have an interest in supporting this work, at any point along the pathway, then please contact Dr Simon Longstaff at The Ethics Centre, or Evan Hannah, who leads the team at Primary Ethics.

Dr Simon Longstaff is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre: www.ethics.org.au

Evan Hannah can be contacted via Primary Ethics at: www.primaryethics.com.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture