Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Helen Boyd The Ethics Centre 9 NOV 2015

I’ve been doing work with and for trans women for about 15 years now. And the thing I tell most audiences at the outset is this – once you know one trans person, you know one trans person. That is all you know.

Germaine Greer has met a few trans women and she has made a decision about all trans women. She has decided that trans women are not women.

I am going to give her the benefit of the doubt and assume she is not making such a sweeping statement based on personal and anecdotal evidence. This leaves only biology and theory as ways to determine what defines a woman.

Let’s start with biology.

I believe trans women are not just women, they are female. This is a hang-up on the part of many feminists who are still stuck in some world where biology is destiny. Because if ‘woman’, as de Beauvoir argued, is a social construct, we become women by living as women in the world, by facing oppression based on gender. For some women, that social conditioning starts with birth because of a vagina and a doctor’s declaration. For others, it starts at 15, 45, 75…

There is nothing feminist about asserting the rights of the oppressors over the dignity and value of the oppressed.

Trans women are aware they are female and are meant to have bodies that allow others to gender them correctly. Harry Benjamin, a pioneer in trans issues, saw attempts to change the minds of transgendered people as not only futile but un-Hippocratic. Changing minds caused unnecessarily suffering. So he designed a way to change bodies.

Definitions of sex are based on very little – chromosomes and hormone dominance. The combination of those two is what creates a sexed body, but we also know that bodies with vaginas sometimes come with XY chromosomes and vice versa.

We also really have no idea what part of the brain “tells” us our sex. Mostly, for those of us who are not trans, we never face a disruption between our bodies/glands/hormones and the way we are socialized. Trans people do. Some experience a crippling, brutal disruption. They experience gendered oppression both internally and externally.

Which is all my way of saying ‘female’, like ‘woman’, is an unstable category. Its very definition is changes based on what we know about bodies, chromosomes, hormones, foetal development, and particularly brain sex.

So we turn to theory for a definition of woman instead.

As a feminist my compassion is with those who experience gendered oppression of any kind. My intersectional feminism recognises all women experience gendered oppression in different ways. For black women, gendered oppression is racialized. For poor women, gendered oppression is classed. For trans women, gendered oppression is transphobic.

I don’t know how Germaine Greer missed out on 30+ years of gender theory, positing that woman is a stable, universal and identifiable category. It hasn’t been for a very long time. I also don’t know how she can be any kind of post-structural feminist and not acknowledge that socialization is what makes a woman a woman.

I don’t know of a group of women right now who are more restricted or oppressed by someone else’s definition of ‘woman’ than trans women.

And I don’t know of a group of women right now who are more restricted or oppressed by someone else’s definition of ‘woman’ than trans women (except, of course, black women and lesbians and childfree women and post-menopausal women). ‘Woman’ is, after all, a category of patriarchy’s making.

It pains me to see a feminist borrow tools from the master’s toolbox and call them liberation.

Germaine Greer is wrong. She carries a greater resonance and burden because we expect such remarkable feminism and knowledge from her. She is not dismissible or stupid, but she is still wrong. Everything I know as a feminist is built on inclusion. ‘Woman’ is an alliance, not an identity you choose. It is the sum of all of the parts of what it is to live in a patriarchy and to feel no power and a tremendous threat of violence if you don’t follow the rules.

If there is anyone in the world who is experiencing those things right now, it is trans women. She is not just upsetting people by saying what she says. She is giving those who hate trans women permission to make their lives more miserable. And there is nothing feminist about asserting the rights of the oppressors over the dignity and value of the oppressed.

Her stance is not just harmful and illogical but more than anything else it seems spiteful, exclusive, and lacking in compassion. It is not my feminism, and no feminist worth her salt would exclude other women based on how good or how bad they are at being women. And she is doing exactly that.

Read a different take on trans women and Germaine Greer here, by Aoife Assumpta Hart.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

BY Helen Boyd

Helen Boyd is the author of My Husband Betty and She’s Not the Man I Married: My Life with a Transgender Husband.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Rebecca Roache The Ethics Centre 4 NOV 2015

Despite its usefulness when you lock your keys in the house, or forget about a crucial meeting or trip on your child’s toy, people object to swearing. The justifications are usually moral, or quasi-moral. We’re often told swearing is disrespectful, impolite, aggressive, intimidating or insulting.

It is also common to hear a pragmatic objection to swearing. We risk wearing out swear words by saying them too often. If overused, swear words will lose their power to shock. Too much swearing will result in a bland, emotionally inert vocabulary.

Is this true? Is it already happening?

This pragmatic worry is well founded. Philosopher Joel Feinberg remarked that swear words “acquire their strong expressive power in virtue of an almost paradoxical tension between powerful taboo and universal readiness to disobey”. We need the taboo to make swear words powerful in the first place. And we need to break the taboo in order to make use of their power.

If we are too eager to disobey a taboo then we risk losing the taboo. This frequently happens in other areas of life, often for the better. Public displays of homosexuality were shocking 20 years ago but – at least in the UK and many other countries – not now, largely thanks to an increasing visibility and openness about sexuality.

This might be happening with swearing too. There are more opportunities to encounter swearing, due to increasingly liberal attitudes and the proliferation of uncensored discussion on the internet. A report by the BBC and the ASA (the Advertising Standards Authority) found that “fuck” – once close to the pinnacle of offensiveness – is less shocking than it used to be.

We probably have a few years to go before the Queen uses her Christmas Day speech to report that she has had a “fucking shit year”.

But this underestimates the complexity of how we shock people by swearing. While “fuck” is pretty ubiquitous in some situations, there remains a strong taboo against using it in other contexts. We probably have a few years to go before the Queen uses her Christmas Day speech to report that she has had a “fucking shit year” rather than an annus horribilis. It will be a while before your doctor breaks news of your terminal illness by saying, in a most sympathetic voice, “You are totally fucked”.

And even in contexts where we can swear more freely, much depends on how we swear. Your Facebook friends may not bat an eyelid at your Saturday night status update, “Fucking wasted again”.

You might, however, put a few noses out of joint if you respond to their cheerful birthday wishes with a “Fuck you!” Using swear words to shock is not purely a matter of the availability of shocking words.

In any case, even if “fuck” really were to lose its shock value we still have plenty else to choose from. Many people who don’t mind “fuck” still draw the line at “cunt”. If you really want to get someone’s attention in these enlightened times, you could utter a racist or homophobic slur. The offensiveness of this sort of language has increased at the same time as the offensiveness of “fuck” has decreased.

There are persuasive moral reasons why you shouldn’t use prejudicial language, but the issue here is not the ethics of offensive language, but whether we have any powerful swear words left. The availability of shocking words tracks what people find offensive. As long as we remain offended by something or other, we will have the capacity to offend people by referring to it. And if offensive ways to refer to it don’t exist, we can invent them.

If you’re looking for a way to shock and offend, to express anger or to help you cope with the pain of stepping barefoot on a piece of Lego, you don’t need to resort to hate speech. You don’t need to swear either. Just break a few taboos.

Go on Facebook and tell your best friend his new baby is ugly. Tell your boss she’s put on weight. Loudly summarise your preferred masturbation techniques for the benefit of everyone in your train carriage.

Hell, you don’t even need to use language. Give your colleagues the middle finger. Turn up to work naked. Take a dump in the aisle during a church service. Write an online essay replete with swear words and disconcerting examples.

With a little imagination we can find limitless and powerful ways to offend people if that’s what we want to do. We don’t need to give a fuck about whether our favourite swear words are declining in their capacity to shock.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

BY Rebecca Roache

Rebecca Roache is a British philosopher and Senior Lecturer at Royal Holloway, University of London, known for her work on the philosophy of language, practical ethics and philosophy of mind.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 2 NOV 2015

This article was originally published on The Age.

The decision by Cranbourne Carlisle Primary School in 2015 to allow some of its students a temporary exemption from singing Australia’s national anthem has sparked outrage in some quarters.

Those exempted all belonged to the Shiite faith, a branch of Islam. But I expect these students usually sang the anthem with as much pride as any other Australian child.

However, on this occasion, the opportunity to sing fell during the month of Muharram – a period of mourning during which Shiites remember and honour their founder, Imam Hussein. This is a month of solemnity in which Shiites are to avoid all joyful acts, including singing. It captures some of the tone of the Christian period of Lent which was traditionally a time devoted to pious reflection and avoiding overtly pleasurable activities.

So what might be said about a school’s decision to let children put religious observance ahead of patriotic duty?

There would have been barely a ripple of dissent if the issue had been one of physical capacity.

The first thing to note is there would have been barely a ripple of dissent if the issue had been one of physical capacity. Imagine a young girl who has recently returned to school after throat surgery. She feels fine. Her voice has returned to normal and all discomfort has gone.

However, her doctor has warned she is not to shout or sing for the next month to protect against scarring. She must also avoid dust and smoke, and stay indoors where possible.

Her first day back coincides with the school assembly. By tradition, the school meets under the spreading oaks that are the its finest feature. The classes are formed up around a central pole where the Australian flag is raised each morning as the national anthem is sung by all.

The student wants to join her classmates at assembly and participate equally in the proceedings. Like every child her age, she does not want to stand out from the crowd. But her mother has explained the situation to the school principal, so instead of singing the national anthem with gusto, she finds herself sitting inside her classroom waiting for the others.

Now, would this student, her parents or the school authorities be blamed for not singing the national anthem or for not being at assembly? I think not.

Yet the analogy between this hypothetical and the Carlisle case is good in all respects but one. The risk faced by students at Carlisle was of a spiritual rather than physical order.

The idea of spiritual risk or disorder has become unfamiliar in an increasingly secular society. For many people, it is perplexing that someone might genuinely fear ‘sinful conduct’ or that such a concern takes precedence over civic duty.

Yet not so long ago a majority of Australians believed in hell and the possibility of ‘eternal perdition’. Indeed there are still people who would choose to be imprisoned or die rather than act against their religious beliefs or conscience.

The fact that the spiritual worldview is so unfamiliar to us does not make it any less real or powerful for those who are pious and concerned for the health of their souls.

One might doubt the validity of the metaphysics but not the sincerity of the believers.

The Shiite children of Cranbourne Carlisle Primary School were neither rejecting nor disrespecting Australia when they temporarily withdrew from their assembly. They were protecting their spiritual integrity. They were also accepting the advantages of living in a liberal democratic society that guarantees their right to the peaceful enjoyment of religious freedom.

The children who remained in assembly were singing the national anthem in support of this ideal. For all Australians are young and free.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2015

The New York Times Magazine polled its readers. “If you could go back and kill Hitler as a baby, would you do it?” 42% of people said yes.

Why they decided to ask the question is a mystery, but it sparked a meme that’s been bouncing around the internet ever since. The meme reached its zenith when Huffington Post asked Jeb Bush whether he would do the deed.

“Hell yeah, I would,” he declared. “You gotta step up, man.” Bush acknowledged the inherent fragility of time travel – as explored by scholars Marty McFly and Doc Brown, but ultimately conceded, “I’d do it. I mean, Hitler…”

Before you saddle up behind Jeb on the time travel express to Hitler’s nursery, here are a few things to consider.

Baby Hitler is innocent

Most ethical justifications for killing start with the presumption that people don’t deserve to be killed unless they’ve done something to forfeit their right to life. Depending on who you speak to, this might include being involved in an attack against somebody else, being in the military or even trafficking drugs.

Unless baby Hitler is running a Walter White-esque meth operation out of his preschool, he’s done nothing to forfeit his right to life.

Until he does – say, by orchestrating genocide – Hitler retains it. Killing him as a baby would therefore be wrong.

Acts of evil have personal costs

Knowingly doing the wrong thing – like killing an innocent baby – carries a personal cost. When we transgress against deep moral beliefs we can experience debilitating guilt, shame, anxiety and depression. Such actions can even come to define us permanently.

Some academics are now using the term ‘moral injury’ to describe the personal costs of acting against our moral beliefs. “Don’t kill innocent children” is arguably the most deeply held moral belief any of us have. Violating that norm comes at a severe price.

“Don’t kill innocent children” is arguably the most deeply-held moral belief any of us have. Violating that norm comes at a severe price.

Doing something wrong for the greater good doesn’t always work

German philosopher Immanuel Kant rejected the idea that ethics was just about “the greatest good for the greatest number” (a view known as consequentialism). Instead he argued that ethics was about doing what you are duty-bound to do – such as tell the truth and don’t kill.

He once considered the question of whether you could lie to save someone’s life. A murderer asks you for the location of a certain baby because he wants to murder him. Can you lie to save the baby’s life? Kant argued that you couldn’t – because you can’t guarantee that your lie will save the baby.

If you send the murderer to the bowling alley knowing the baby is upstairs, who’s to say the babysitter hasn’t taken the baby to the bowling alley without your knowledge? Suddenly you’ve told a lie and the baby is still dead, so you’ve made the situation worse overall.

In the case of Hitler, you would need to be certain his death would prevent the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust. If – as many historians contend – the rise of Nazism was a product of a range of social factors in Germany at the time, then killing a baby isn’t going to reverse those social factors. Butchering the babe might even allow for the rise of another power – equal to or worse than Hitler.

And you’ve still killed a baby.

Killing isn’t necessary

Some people argue that killing the innocent might be justified when it is the lesser evil. But even in that case it has to be absolutely necessary. If time travel is possible, it seems unlikely to be necessary to kill baby Hitler as opposed to, say, kidnapping him, adopting him out to a Jewish family or offering him a scholarship to the Vienna School of Fine Arts.

If time travel is possible, it seems unlikely to be necessary to kill baby Hitler.

Human lives are of immense, perhaps even infinite value. To take one – especially an innocent one – when it isn’t absolutely necessary is a serious ethical issue.

Dangerous precedent

Where do we draw the line? Once we’re done with Hitler which baby is on the block next? Pol Pot? Stalin? The guy who spoiled the end of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix for me in high school? We would require a set of consistent, universal ethical principles by which to determine which babies deserve death and which don’t.

Giving baby Hitler all of our murderous attention betrays our cognitive and personal bias – surely there are other worthy candidates? How many lives must a person take before their infant self is a legitimate target for killing? What standard will be applied?

For me, I wouldn’t do it. I mean, just look at baby Adolf…

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Aoife Assumpta Hart The Ethics Centre 30 OCT 2015

Early on in my transition I was physically assaulted whilst boarding a bus. My back had been turned, my hands occupied with digging in my purse for a ticket when a solid fist struck me from the side – a sucker punch.

He yelled “TRANNY!” and trotted away at a mild gait, unhindered by any witnesses.

This thug’s annoyance resulted from me having just declined his offer of a nugget of crack cocaine in exchange for an alleyway blowjob. Since I was a transwoman waiting for public transit, I was clearly available to be propositioned for sex.

I know one thing for certain as I look back on that incident. This vicious bloke had never read Simone de Beauvoir. He had never read Germaine Greer.

And yet according to students from Cardiff University, Germaine Greer is somehow responsible for me getting smacked on the skull because of her views about transgender issues. What are these violent ideas? In her own words:

I don’t think that post-operative transgender men – M to F transgender people – are women . . . I’m not saying that people should not be allowed to go through that procedure, what I’m saying is it doesn’t make them a woman.

A petition written by Cardiff University Students’ Union’s women’s officer reads:

Such attitudes contribute to the high levels of stigma, hatred and violence towards trans people – particularly trans women – both in the UK and across the world.

So, an academic lecturing in Wales who understands “woman” to mean “an adult human female” is complicit in the murder of trans women (often poor and of a racial minority) by savage men (almost always by men)?

Let’s be honest about liberals and their armchair activism. Slagging off older women on Twitter or from the ivory tower is a hell of a lot easier than confronting actual male violence.

Greer, following feminists such as Simone de Beauvoir, assesses that male and female sexuation is not a myth or a personal feeling, but material states of embodiment within ethical circumstances. She rejects a world in which a bepenised Caitlyn Jenner is dubbed Woman of the Year without having actually lived as a woman for an entire year. Greer denies feeling you are actually female inside is enough to define you as female.

Greer denies feeling you are actually female inside is enough to define you as female.

I signed a petition in support of Germaine Greer because I support her right to speak. As an academic I’m not afraid of lively and vigorous argument. As a transsexual I’m tired of my experience being erased in service to genderism. As a human person I would like a world without gender where we’re free to express ourselves regardless of sex.

Trans activists tell us “gender is not sex” like a mantra bereft of enlightenment. Well, what is gender? They never answer. Where did it come from? They never answer.

Sexual difference is the reality of how mammals reproduce. Gender is a socially constructed hierarchy of sex-based norms imposed onto bodies. Feminism contends that the specific reproductive capacities of female persons are exploited and dominated by male power, with gender as a mechanism of control.

Transgenderism, however, disavows that biological sex is an actual, real category people can fall into. Instead, trans activists adhere to the claim that being male or female is a matter of arbitrary opinion. A male must really be female if ‘she’ possesses a subjectively-identifiable cache of feminine personality traits. By her own command, she was always female, will always be female because thinking makes it so.

Greer rejects gender identity as a coherent essence. Attentive to the practical circumstances of sexuality and power, Greer defines woman as the female sex, and this by definition is exclusive of males – no matter how arbitrarily feminine their inner disposition might be.

To claim males who express “feminine” preferences must actually be female inside is to try to turn ideology into reality.

By defining sex as a materially determined fact and not imaginary assignment, Greer states an anthropological truth. You may not fancy her tact but objecting to her tone is not sufficient to overcome the feminist analysis of gender that Greer advances.

Gender is a synthetic ideology imposed on sex. To claim males who express “feminine” preferences must actually be female inside is to try to turn ideology into reality. And it is to do so on the basis of sex-based stereotypes.

Because these views can appear harsh, troubling, and oppositional to the worldview of many trans sympathisers, Greer’s opponents turn to the most regressive, chauvinistic tactic – aggressively enforcing silence. Rather than providing cogent arguments concerning gender identity, trans activists choose the tactic of no platforming.

Why are people afraid of Greer? Because she is a woman saying no to gender.

Read a different take on trans women and Germaine Greer here, by Helen Boyd.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Nikki Coleman The Ethics Centre 14 OCT 2015

The US. military may finally be coming around on the question of women on the front lines.

In a confidential briefing on September 30, military leaders presented their recommendations on having women on the front lines to the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Military Personnel, and Defense Secretary Ashton Carter.

In the 1940s, the US military faced similar debates regarding black service personnel. Arguments regarding unit cohesion and operational capability were the most prominent against integration of white and black personnel. With the power of hindsight, we can see those arguments for what they were – scare tactics intended to keep the military segregated.

The same arguments have returned today. At the command of Secretary Panetta, the US Army underwent a two-year study to develop gender-neutral standards for specialist roles currently closed to women. The success of this standardised approach was demonstrated recently when two women graduated from the Army Ranger School.

There have been vocal critics of allowing women to attempt the Army Ranger School course. Some claim the standards were lowered for these women. This was denied by the Army at the Ranger School graduation ceremony. It was rebuked again by the Chief of Army Public Affairs who described the allegations as “pure fiction”.

These allegations are unlikely to settle down any time soon. A Congressman has requested service records of the women who graduated to investigate “serious allegations” of bias and the lowering of standards by Ranger School instructors.

This incident reveals the depth of scepticism regarding women’s ability to serve alongside men within some quarters. The standardised approach has dismissed the issue of operational capacity – the other arguments against female service are equally weak.

The potential for women to be captured and raped has been raised by opponents of women serving in combat units. This discussion ignores the sad reality – women in defence are much more likely to be sexually assaulted by their own troops than by the enemy. The 2013 Department of Defense report into sexual assault found that while women make up 14.5% of the US military, they make up 86% of sexual assault victims.

Women in defence are much more likely to be sexually assaulted by their own troops than by the enemy.

Of the 301 reports of sexual assault in combat zones in 2013 to the Department of Defence, only 12 were by foreign military personnel. The vast majority of sexual abuse victims in combat areas were abused by their own comrades, not the enemy.

Sexual abuse in the military has been a problem for decades. Why would it increase if we allowed women in combat? Rape of captured soldiers has also not been limited to women. Many men have also been sexually assaulted on capture. Sexual assault in this sphere is not about sexual desire or gratification – it’s about power and denigration of your enemy.

The second argument suggests women in combat units will affect unit cohesion. First, “the boys” won’t be able to be themselves. And second, if a woman is injured in battle men will be unable to focus on the mission and instead will be driven to protect their female colleagues.

The first argument raises a question about military culture. Why is behaviour considered inappropriate around women tolerated at all? The second argument is insulting to currently serving soldiers, whose professionalism and commitment to the mission is questioned.

To suggest soldiers would ignore the mission in favour of some other goal undervalues the extent of their military professionalism.

Soldiers overcome a range of powerful instincts in a firefight – including protecting their own lives. To suggest soldiers would ignore the mission in favour of some other goal undervalues the extent of their military professionalism.

There is also an elephant in the room. Women have been serving in combat roles for years – as pilots, on ships, as interpreters and in female engagement teams. For these women a decision regarding the position of women in combat is irrelevant – they are already on the front lines.

The Australian situation sits in stark contrast to that of the US. Gay and lesbian members have served openly for a decade, women have been fully integrated into combat units since 2013, and the Australian Defence Force now actively recruits transgender personnel.

Australia has been able to integrate women, gay, lesbian and transgender soldiers into combat units without affecting operational capability.

Hopefully the US Defense Secretary will follow the advice of his Chiefs of Staff and the leadership of the ADF. He should allow military personnel to serve in all roles in the military according to universal standards rather than chromosomes or genitalia.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

BY Nikki Coleman

Nikki Coleman is a PhD Candidate and researcher with the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society at UNSW Canberra. In her free time she is the “Canberra Mum” to many officer cadets and midshipmen at ADFA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Chris Fotinopoulos The Ethics Centre 7 OCT 2015

Australia’s persistent anti-euthanasia stance is unfair, cruel and insensitive. It provides limited means to adults of sound mind to die on their own terms.

The current law on euthanasia restricts control and choice for certain terminally ill patients. It does so by denying them access to death-enabling drugs, information on how to administer them and appropriate medical support – including a physician’s assistance when needed.

The law compels certain individuals to die in ways they abhor and cannot easily escape. Meanwhile, others die peacefully and in control – often in their homes surrounded by loved ones and with appropriate medical assistance, albeit clandestine.

I’m always intrigued by the announcement of a prominent Australians death. The deceased invariably dies peacefully at home, with loved ones by their side. Why is it that the powerful and well connected often depart gently? Why are the less privileged compelled to endure irremediable suffering over a prolonged period?

Why it is that the powerful and well connected often depart gently? Why are the less privileged compelled to endure irremediable suffering over a prolonged period?

I’m reminded of a story a young man told me last year. He spoke movingly about how he lost his mother under tragic circumstances that could have been avoided if not for the state’s stance on voluntary euthanasia.

His mother was suffering from a serious long-term mental illness. Her desperate pleas to her doctors to help end a life that she described as “a living hell” were consistently dismissed as irrational. She was ultimately forced to die a violent death at her own hand.

According to her son, the life she foresaw was a life that she did not want. There was very little the medical profession could do to help her end it. His mother’s only option was suicide, which she took one lonely night at home after manically swallowing a cocktail of prescribed pills washed down with alcohol.

Her neighbour discovered her decaying corpse with a plastic bag over its head days after she died what must have been a horrible death.

This had a profound psychological impact on her son. He experienced depression, anxiety and complicated grief. The horror of his mother dying painfully and alone in such a setting is something that will stay with him to his grave.

A humane, just and civilised society should never insist on laws that allow such tragic deaths to continue. It should certainly not allow those rendered powerless through serious illness to suffer horrible deaths of this kind.

Society should do far more to empower the vulnerable through the provision of appropriate medical assistance, guidance and legal support. It should help them govern their life in a way that minimises suffering and delivers dignity in death.

Horrible deaths are not only restricted to the home. They also take place in hospitals and inpatient hospices. Years ago, I spoke with a senior oncologist at The Royal Melbourne Hospital. He spoke candidly about the problem in accessing life-ending medication for his patients.

He spoke of a seriously unwell middle-aged female patient who he regarded as a friend. She had no immediate family or close friends to help her finish her life well. She did not have a network of people who could help enact a plan that allowed her to die peacefully and with dignity in the comfort of her home. The only person who could help was her oncologist but he was legally unable to do what he understood would give her dignity in her death.

In this case both patient and doctor were locked under state control. They were denied choices available to those who have the good fortune, legal nous and medical support to implement their plans away from the state’s reach.

The contradictory and confused nature of our anti-euthanasia laws become apparent when viewed in light of the state’s stance on suicide. Suicide is not illegal. Australians are at liberty to take their own lives through a variety of different means, assuming they have the physical capacity to do so. Despite the grief suicide can cause to bereaved loved ones, it is nearly impossible – and arguably unethical – to prohibit.

A humane, just and civilised society should never insist on laws that allow such tragic deaths to continue.

If someone has the ability to end their life, they are free to do so. But those unable to end their life by their own hand are forced by the law to endure prolonged, unnecessary and irremediable suffering.

Anti-euthanasia advocates often argue palliative care is far more humane and caring than killing. They suggest more funding be directed to palliation rather than amending laws that allow the terminally ill to seek direct death. But those who take this line fail to acknowledge that some patients find death while under palliative sedation repugnant and unacceptable.

Denying a terminally ill person the option of choosing direct death over unwanted palliation is an infringement on their autonomy.

We need to appreciate that palliative care and physician-assisted death are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, terminally ill individuals who have high quality palliative care may be more open to the idea of assisted dying than those who do not.

Research conducted at Brunel University in London found terminal cancer patients in British hospices were more likely to consider doctor-assisted dying than those in hospitals. This contradicts the commonly-held view that assisted dying would decrease if options such as palliation and hospice care were readily available.

Voluntary euthanasia laws would not diminish the value of human life. They would enhance the prospect of a peaceful death by shifting control away from the state and other institutions. If individuals were granted control over this decision they would be empowered to achieve what they believe to be a good death.

If we are committed to delivering a good and peaceful death to all, then the law must extend personal autonomy, greater control and genuine informed choice to all Australians.

Nigel Baggar’s counter-argument is here.

In Australia, support is available at Lifeline 13 11 14, beyondblue 1300 224 636 and Kids Helpline 1800 551 800.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

BY Chris Fotinopoulos

Chris Fotinopoulos is an ethicist, writer and educator. He recently co-authored the Rationalist Society’s submission to the Victorian State Government Inquiry into End of Life Choices.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to respectfully disagree

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 2 OCT 2015

Why do we find it so hard to discuss difficult issues? We seem to have no trouble hurling opinions at each other. It is easy enough to form into irresistible blocks of righteous indignation. But discussion – why do we find it so hard?

What happened to the serious playfulness that used to allow us to pick apart an argument and respectfully disagree? When did life become ‘all or nothing’, a binary choice between ‘friend or foe’?

Perhaps this is what happens when our politics and our media come to believe they can only thrive on a diet of intense difference. Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Things that truly matter just overwhelm us with their significance. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Indeed, I think this must be it. Most of us have a deep-seated dislike of ambiguity. We easily submit to the siren call of fundamentalists in politics, religion, science, ethics … whatever. They sing to us of a blissful state within which they will decide what needs to be done and release us from every burden except obedience.

But there is a price to pay for certainty. We must pay with our capacity to engage with difference, to respect the integrity of the person who holds a principled position opposed to our own. It is a terrible price we pay.

The late, great cultural theorist and historian, Robert Hughes, ended his history of Australia, The Fatal Shore, with an observation we would do well to heed:

The need for absolute goodies and absolute baddies runs deep in us, but it drags history into propaganda and denies the humanity of the dead: their sins, their virtues, their failures. To preserve complexity, and not flatten it under the weight of anachronistic moralising, is part of the historian’s task.

And so it is for the living. The ‘flat man’ of history is quite unreal. The problem is too many of us behave as if we are surrounded by such creatures. They are the commodities of modern society, the stockpile to be allocated in the most efficient and economical manner.

Each of them has a price, because none of them is thought to be of intrinsic value. Their beliefs are labels, their deeds are brands. We do not see the person within. So, we pitch our labels against theirs – never really engaging at a level below the slogan.

It was not always so. It need not be so.

I have learned one of the least productive things one can do is seek to prove to another person they are wrong. Despite knowing this, it is a mistake I often make and always end up wishing I had not.

The moment you set out to prove the error of another person is the moment they stop listening to you. Instead, they put up their defences and begin arranging counter-arguments (or sometimes just block you out).

The moment you set out to prove the error of another person is the moment they stop listening to you.

Far better it is to make the attempt (and it must be a sincere attempt) to take the person and their views entirely seriously. You have to try to get into their shoes, to see the world through their eyes. In many cases people will be surprised by a genuine attempt to understand their perspective. In most cases they will be intrigued and sometimes delighted.

The aim is to follow the person and their arguments to a point where they will go no further in pursuit of their own beliefs. Usually, the moment presents itself when your interlocutor tells you there is a line, a boundary they will not cross. That is when the discussion begins.

At that point, it is reasonable to ask, “Why so far, but no further?” Presented as a case of legitimate interest (and not as a ‘gotcha’ moment) such a question unlocks the possibility of a genuinely illuminating discussion.

To follow this path requires mutual respect and recognition that people of goodwill can have serious disagreements without either of them being reduced to a ‘monstrous’ flat man of history. It probably does not help that so much social media is used to blaze emotion or to rant and bully under cover of anonymity. People now say and do things online that few would dare if standing face-to-face with another.

It probably does not help that we are becoming desensitised to the pain we cause the invisible victims of a cruel jibe or verbal assault. Nor does it help that the liberty of free speech is no longer understood to be matched by an implied duty of ethical restraint.

I am hoping the concept of respectful disagreement might make a comeback. I am hoping we might relearn the ability to discuss things that really matter – those hot, contentious issues that justifiably inflame passions and drive people to the barricades. I am hoping we can do so with a measure of goodwill. If there is to be a contest of ideas, then let it be based on discussion.

Then we might discover there are far more bad ideas than there are bad people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Steve Vanderheiden The Ethics Centre 30 SEP 2015

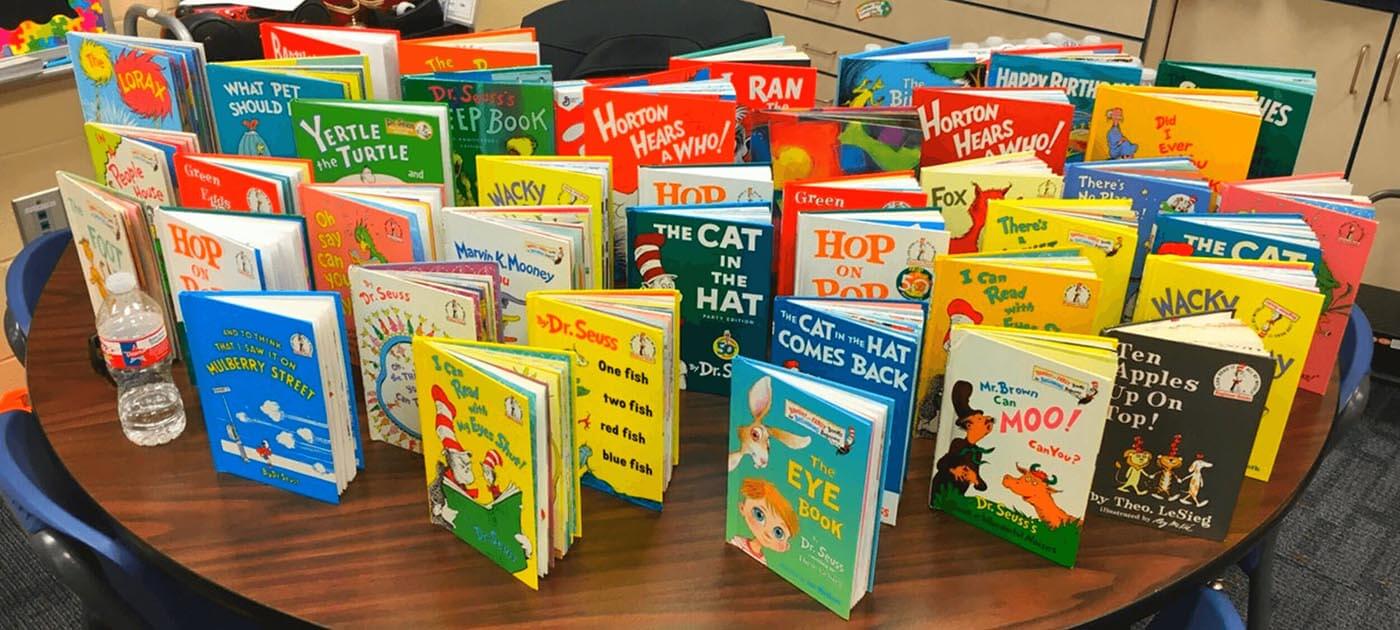

Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax explores the consequences of deforestation and the environmental costs of development. It concludes with the Once-ler, the narrator of the story who is principally responsible for deforestation of the decimated Truffula tree, entrusting its final seed to a young boy. He implores the child, “Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack. Then the Lorax and all of his friends might come back.”

The Once-ler, wracked by guilt for his complicity in this environmental disaster, passes along responsibility for reversing damage done by his generation to a child. The Lorax suggests the young take on duties of planetary stewardship where adults have failed.

Is this fair? Perhaps the generation responsible for mucking up the planet has lost its moral authority to try and save it. So the task of conservation is inherited by those with a longer-term stake in its future.

That adults might vest hope for a better planet in our children is both edifying and deeply troubling. Edifying because the environmental record of the world’s children bests that of adults by default. The young have not yet begun to reproduce the patterns of behavior that implicate their parents – resource depletion, biodiversity loss, climate change…

Troubling because they may reproduce them in future. We cannot realistically expect young people socialised into a world of willful environmental neglect to behave much differently than their parents have. Adults cannot so easily absolve themselves of the responsibility of addressing environmental harm they have caused.

Rather than saving the planet, a more modest objective might be to refrain from making it much worse for our children. Even this is a daunting prospect. Patterns of energy use dependent on fossil fuels all but guarantee that global temperatures will continue to rise. For most, climate change is no longer a debate about “if” but “how severe?”

We may still hope to make the planet better for our children in other ways. For instance, by adding to the richness of human culture and the stock of beneficial technologies. When it comes to climate though, a more appropriate aim might be to refrain from chopping that last Truffula tree. To preserve our remaining forests so our children might be able to see the proverbial Brown Bar-ba-loots, Swomee-Swans or Humming Fish in their native habitats rather than natural history museums.

Doing this will be challenging. It will require an often uncomfortable reflection on what drives global environmental degradation. In Seuss’ tale the insatiable demand for thneeds – the ultimate commodity – drives the Truffula deforestation. This implicates our heedless consumerism in the causal chain of degradation alongside the Once-ler.

When we consume things we don’t need, and when the industry around these commodities is obviously unsustainable despite our obliviousness to this fact, we contribute to resource depletion. What’s more, we add to the attitudes and norms that suggest this is a private matter, answerable only to private consumer preferences and not larger public concerns for equity or sustainability.

Worst of all, we teach our children to do the same.

The first step in reducing our negative impact upon the planet must be to understand how and where we make the impact we do. We need to understand alternatives that yield comparable value to us with a lighter toll upon the planet. Consuming more conscientiously will leave our children a better planet and make them better citizens of it. Though it requires us to consume differently and less.

Thinking about the long-term consequences of our choices will also help. We cannot plausibly claim to value our children’s future while discounting the future value of current investments in sustainable infrastructure or future costs of unsustainable current practices.

To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

Our deeds announce our concern for the welfare of future generations more accurately than our words or thoughts. Thinking about such choices must be accompanied by some changes in course. Citizens must demand better public choices be made rather than acquiescing to worse ones as unavoidable products of political inertia or inviolable market forces.

The tendency to shift problems across borders is no less insidious than passing them to our children or grandchildren. To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

As role models for our children our success in stopping environmental harm will matter less than our sincerity in the efforts we make. If we honestly try to maintain the planet, our example will help make them into the kind of people our planet needs.

For as the Once-ler interprets the Lorax’s cryptic final word, “UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

BY Steve Vanderheiden

Steve Vanderheiden is Associate Professor of Political Science and Environmental Studies at University of Colorado Boulder and Professorial Fellow with the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics (CAPPE) at Charles Sturt University.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Julian Savulescu The Ethics Centre 16 SEP 2015

In 2015, The National Health and Medical Research Council was accepting public submissions regarding sex selection in IVF procedures. It has previously prohibited non-medical sex selection.

This is one of two responses we’ve published on our website. Don’t agree with Julian? Check out Tamara Kayali Browne‘s piece, which argues that IVF sex selection is unethical.

Current NHMRC guidelines prohibit non-medical sex selection by any means. Victoria, Western Australia and South Australia have specifically legislated to ban sex selection using assisted reproduction.

The guidelines are now under review, providing the Australian public, the NHMRC and professionals an opportunity to re-examine their opposition to sex selection.

Opposition to the legalisation of non-medical sex selection illustrates a misunderstanding of the role of law in civil society. If A wants to do X, and B wants to assist A to do X for a price, the sole ground for interfering in their freedom is they will harm someone. Moral disapproval is not a ground for a legal ban.

Who would be harmed by allowing sex selection?

The most obvious candidate is the child. Call him John. The basis of most legislation in assisted reproduction is that the best interests of the child must be paramount. However, it is not against the interests of John to be conceived by sex selection. Indeed, if IVF and sex selection were not performed, John would not exist. John owes his very existence to the act of sex selection.

There is another kind of harm often invoked in these kinds of debates – a moral harm. John is being used as a means to his parents’ ends of having a child whom they have stereotyped goals for. John is being used as an instrument.

People intuitively believe that children should be “gifts”, not valued for particular characteristics, such as sex, intelligence or athletic ability. We ought to give them their own opportunity to make their own life. That is, they should have a right to an open future.

Enter Immanuel Kant

Such objections are best expressed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who said people should always be treated as an end, and never a means.

But what Kant actually said is never treat people merely or solely as a means. We treat people as a means all the time – shopkeepers, salesmen, repair people and doctors. We respect adults by obtaining their consent to treat them as a means.

It is not possible to obtain consent from children – particularly not regarding their creation. What then does it mean to treat a child merely as a means?

People have children for all sorts of reasons – to be a sibling, to hold a marriage together, to care for parents, to be a companion, to realise the parent’s dreams, to take over the family business or to be king of England. Ethically, these reasons aren’t important. What matters is how well they treat their child once it is born, whether male, female, disabled, tall, short, come what may.

Something like this kind of “instrumentalisation” objection might be behind the NHMRC’s policy:

A conditional life

The Australian Health Ethics Committee believes that admission to life should not be conditional upon a child being a particular sex.

Equality of all people should not be conditional upon any characteristic, such as their sex. But there is a distinction between continued existence and coming into existence. Continued existence should not be conditional on sex.

It might be thought the same follows for admission to life. But the NHMRC does allow medically motivated sex selection to guard against certain diseases and disabilities. This suggests admission to existence can be “conditional” upon being healthy and non-disabled.

What “conditional” means here is “based on reasons”. One can have children for reasons, such as being of certain sex, having certain abilities, being healthy or not disabled. As long as one loves the child, gives the child an open future and good life, having reasons to have that child is perfectly ethically acceptable.

For example, a father wants to have a son to take to football matches. He therefore moulds the child to his needs by sex selecting. He can still treat the child, once born, as an end by respecting the child’s own decision to pursue an interest in music instead.

Harmful sexist stereotypes

The final alleged harm is to society, either by reinforcing sexist stereotypes or disturbing the sex ratio. In some parts of India and China, there are six males to five females.

Such harms could be real and might be a legitimate basis for interfering in liberty. But another basic principle is that the least liberty-restricting (least coercive) means should be adopted to prevent harm.

The present ban on non-medical sex selection is very wide-ranging and coercive. Are there less coercive means that would allow some sex selection but not reinforce sexist stereotypes and disturb the sex ratio? There are at least three better policies:

- Sex selection only in favour of girls.

- Sex selection for family balancing. That is, sex selection for the second or third child, when the existing children are all of one sex and the preference is for the opposite sex. In Australia, this is the most common reason for sex selection and a little more than 50 percent select girls.

- Incidental sex selection. A couple having IVF and genetic diagnosis for infertility and screening of disorders, could be allowed to express a preference over the healthy embryos, at the discretion of their doctors.

Each of these strategies is less liberty-restricting and would protect the public interest.

There are no good grounds for the blanket ban on sex selection. Sex selection does not harm the child and any collateral harm (due to discrimination) can be controlled in better ways. A blanket ban is unethical, excessively restricting procreative liberty.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships