Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 FEB 2026

Boycotts can be an effective mechanism for making change. But they can also be weaponised or harmful. Here are some tips to ensure your spending aligns with your values.

There I was, strolling through campus as an undergraduate in the 1990s, casually enjoying a KitKat, when I was accosted by a friend who sternly rebuked me for my choice of snack. Didn’t I know that we were boycotting Nestlé? Didn’t I know about all the terrible things Nestlé was doing by aggressively promoting its baby formula in the developing world, thus discouraging natural breastfeeding?

Well, I did now. And so I took a break from KitKats for many years. Until I discovered the boycott had started and been lifted years before my run-in with my activist friend. As it turned out, a decade prior to my campus encounter, Nestlé had already responded to the boycotters’ concerns and had subsequently signed on to a World Health Organization code that limited the way infant formula could be marketed. So, while my friend was a little behind on the news, it seemed the boycott had worked after all.

Boycotts are no less popular today. In late 2025, dozens of artists pulled their work from Spotify and thousands of listeners cancelled their accounts after discovering that the company’s CEO, Daniel Ek, invested over 100 million Euros into a German military technology company that is developing artificial intelligence systems. In 2023, Bud Light lost its spot as the top-selling beer in the United States after drinkers boycotted it following a social media promotion involving transgender personality, Dylan Mulvaney. The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement has been promoting boycotts of Israeli products and companies that support Israel for over a decade, gaining greater momentum since the 2023 war in Gaza. And there are many more.

As individuals, we may not have the power to rectify many of the great ills we perceive in the world today, but as agents in a capitalist market, we do have power to choose which products and services to buy.

In this regard, our dollar is our voice, and we can choose to use that voice to protest against things we find morally problematic. Some people – like my KitKat-critical friend – also stress that we must take responsibility for where our money flows, and we have an obligation to not support companies that are doing harm in the world.

However, thinking about whom we support with our purchases puts a significant ethical burden on our shoulders. How should we decide which companies to support and which to avoid? Do we have a responsibility to research every product and every company before handing over our money? How can we be confident that our boycott won’t do more harm than good?

Buyer beware

Boycotts don’t just impose a cost on us – primarily by depriving us of something we would otherwise purchase – they impose a cost on the producer, so it’s important to be confident that this cost is justified.

If buying the product would directly support practices that you oppose, such as damaging the environment or employing workers in sweatshops, then a boycott can contribute to preventing those harms. We can also choose to boycott for other reasons, including showing our opposition to a company’s support for a social issue, raising awareness of injustices or protesting the actions of individuals within an organisation. However, if we’re boycotting something that was produced by thousands of people, such as a film, because of the actions of just one person involved, then we might be unfairly imposing a cost on everyone involved, including those who were not involved in the wrongdoing.

Boycotts can also be used threaten, intimidate or exclude people, such as those directed against minorities, ethnic or religious groups, or against vulnerable peoples. We need to be confident that our boycott will target those responsible for the harms while not impinging on the basic rights or liberties of people who are not involved.

There are also risks in joining a boycott movement, especially if we feel pressured into doing so or if activists have manipulated the narrative to promote their perspective over alternatives. Take the Spotify boycott, for example. It is true that Spotify’s CEO invested in a military technology company. However, many people claimed that company was supplying weapons to Israel, and that was a key justification for them pulling their support for Spotify. However, Helsing had no contracts with Israel and was, instead, focusing its work on the defence of Ukraine and Europe – a cause that many boycotters might even support.

Know your enemy

The risk of acting on misinformation or biased perspectives places greater pressure on us to do our own research, and it’s here that we need to consider how much homework we’re actually willing or able to do.

In the course of writing this article, I delved back into the history of the Nestlé boycott only to find that another group has been encouraging people to avoid Nestle products because it doesn’t believe that the company is conforming to its own revised marketing policies. Even then, uncovering the details and the evidence is not a trivial undertaking. As such, I’m still not entirely sure where I stand on KitKats.

While we all have an ethical responsibility to act on our values and principles, and make sure that we’re reasonably well informed about the companies and products that we interact with, it’s unreasonable to expect us to do exhaustive research on everything that we buy. That said, if there is reliable information that a company is doing harm, then we have a responsibility to not ignore it and should adjust our purchasing decisions accordingly.

Boycotts also shouldn’t last for ever; an ethical boycott should aim to make itself redundant. Before blacklisting a company, consider what reasonable measures it could take for you to lift your boycott. That might be ceasing harmful practices, compensating those who were impacted, and/or apologising for harms done. If you set the bar too high, there’s a risk that you’re engaging in the boycott to satisfy your sense of outrage rather than seeking to make the world a better place. And if the company clears the bar, then you should have good reason to drop the boycott.

Finally, even though a coordinated boycott can be highly effective, be wary of judging others too harshly for their choice to not participate. Different people value different things, and have different budgets regarding how much cost they are willing to bear when considering what they purchase. Informing others about the harms you believe a company is causing is one thing, but browbeating them for not joining a boycott risks tipping over into moralising.

Boycotts can be a powerful tool for change. But they can also be weaponised or implemented hastily or with malicious intent, so we want to ensure we’re making conscious and ethical decisions for the right reasons. We often lament the lack of power that we have individually to make the world a better place. But if there’s one thing that money is good at, it’s sending a message.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just War Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

360° reviews days are numbered

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

On policing protest

On policing protest

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 16 FEB 2026

I was not there when police confronted people at Sydney Town Hall, protesting against the visit of Israeli President Herzog. So, the best I can do is offer a way of assessing what took place – once all of the evidence is before us.

A fundamental principle of policing is that it is most effective when practised with the consent of the community. With that consent in hand, police are accorded extraordinary powers that may not be exercised by ordinary citizens. Those powers include the right to use force in the discharge of their duties. However, these are not ‘unbridled’ powers. Rather, the use of force is hemmed in by a series of legal and ethical boundaries that must not be crossed.

The application of such boundaries is especially important when police are authorised to use lethal force. However, whether armed or not, the ethos of policing is supposed to be conditioned by two fundamental considerations.

First, all police in Australia exercise what is known as the ‘original authority of the constable’. This is a special kind of authority intended to ensure that police uphold the peace in an even-handed manner, without regard to a person’s wealth, status or office. Originally conceived in medieval times, it ensures that all are equal before the law. One aspect of this ‘original authority’ is the right (or, perhaps, the duty) to exercise discretion when employing the special powers conferred on police. It is for this reason that there is a general expectation that police should warn rather than punish people when that would be sufficient to achieve the proper ends of law enforcement.

And what are those ends? To the surprise of many (including some police) the role of policing is not to apprehend criminals so that they may be brought before the courts. Nor is it simply to ‘enforce the law’. Both of those elements of policing are important. However, they are in service of a more general purpose which is to uphold the legal and moral rights of citizens (only some of which are codified in law). This is why society frowns on the actions of those rare police who, say, plant evidence on a suspect in hope of proving their presumed guilt. You cannot uphold the legal and moral rights of citizens by violating the legal and moral rights of citizens! It is only when police act in a manner consistent with their overarching purpose that the community extends the trust required for policing to be maximally effective.

The main point to note here is that the best way to prevent crimes and other harms is for communities to be intolerant of those who engage in harmful (and especially criminal) conduct. In turn, the communities that most trust their police are also those most intolerant of crime and other antisocial behaviour. For the avoidance of doubt, let me make it clear that I do not consider peaceful protesting to be ‘antisocial behaviour’. Rather, it plays a vital role in a vibrant democratic society.

The second basic fact that conditions policing is related to the asymmetry of power between police and citizens. The most obvious sign of that asymmetry is that, with only a few exceptions, only police may be armed in the course of daily civic life. However, with great power comes great responsibility. In this case, the use of force, by police, must be proportionate and discriminate. That is, force may only be applied to the minimal degree necessary to secure the peace.

Policing is dangerous work. But beyond the risk of physical harm, police are often taunted and insulted – especially by seasoned provocateurs who are trying to bait police to lose control. That is why police require training to resist the all-too-human tendency towards self-protection or retaliation. Again, this is essential to maintaining community trust and consent.

The public needs to be convinced that police have the training and discipline to apply minimal force – no matter what the provocation.

Given all of the above, what questions might we ask about the way police engaged with protesters gathered at the Sydney Town Hall? Did police exercise discretion in favour of the citizens to whom they are ultimately accountable? Was their use of force discriminate and proportional? Did the police exercise maximum restraint – no matter what the provocation?

As to where we might go from here, I think that we would all be well served if the politicians who set the laws within which police operate and the leadership of NSW police all stopped for a moment to ask, “Will the thing we next do build or undermine the trust and consent of the community as a whole?”.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Explainer

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z’s future

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

What it means to love your country

What it means to love your country

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran 4 FEB 2026

The idea of patriotism has become increasingly contentious in Australia, particularly on January 26, with much wariness and controversy over what to call the day itself.

January 26 is a reopening of the deep wound of colonisation for many Indigenous Australians. It can also be, to a lesser extent, a confusing day to be an Australian patriot who is simultaneously ashamed of their country’s colonial past.

Australia’s colonial roots have always loomed large in its young history, but it is helpful to know that the experience of being conflicted about one’s allegiance to country is not new.

In 1943, the Jewish-heritage French philosopher Simone Weil wrote her last text dissecting the difficulty of patriotism while in WWII France. France had built its modern identity on Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality and universal human rights. Yet at Weil’s time of writing, it was actively building a colonial empire and collaborating with the German fascist state which violated these principles.

In a similar vein, modern Australia prides itself on a narrative of multiculturalism, wealth and safety, whilst also being built on the injustices of colonialism. It is increasingly suffering from fraying social cohesion as a result of this inconsistency. The controversy around January 26 is one clear recurring symptom of this.

Weil would have classified herself as a French patriot, but she was also one of its harshest critics. In her philosophy, love of country and criticism of its past are not mutually exclusive; in fact, love of country can only be authentic if it also includes honest criticism.

Patriotism in its best form is the compassionate love of one’s country and the people, communities, history and memories that comprise it.

But to Weil, this patriotism becomes maligned when it is not based in compassion, and instead entails blind allegiance to an abstract nation or symbol – something she called ‘servile love’, which she names as the ugly shadow of patriotism: nationalism.

In her vocabulary, nationalism is more extreme than loving your country; it is about engaging in idolatry and worshipping a false image of one’s country that is based on wishful thinking, rather than truth.

The wishful thinking of nationalism means making oneself ignorant through selective memory: erasing the difficulties of the past in a hurry to create a new, sanitised future. It uses boastful pride to cover up past shames.

In the same way that it is difficult to respect the integrity of an individual who is insecure about admitting their wrongs and will only assert the ways in which they are right, a nation that also cannot integrate its failings will find it hard to sustain respect.

It’s important to note that this is a collective responsibility: generational injustice requires generational reparation, and it is not possible for sole individuals to bear the whole burden of either harm or reparation for entire generations.

What makes a patriot?

In Weil’s framework, the distinction between patriotism (healthy) and nationalism (unhealthy) is ‘rootedness’, which Weil identifies as one of the deepest but most difficult to identify human needs.

A ‘rooted’ individual, community, or nation is one that is mature and connected to its history deeply enough that it has the resilience to withstand criticisms and accommodate the nurturance of many types of people.

Weil writes: “A human being is rooted through their real, active and natural participation in the life of a collectivity that keeps alive treasures of the past and has aspirations of the future.”

To Australia’s credit, there are many ways in which collective participation is healthy and available to many, which allows people from many walks of life to be rooted here.

Some often-cited reasons: being able to enjoy relative peace and comforts; fond memories of swimming at the beach or hiking nature trails (“Australia is the only country proud of its weather” – the allegations are true!); its cultural diversity. There are many patriots to whom the flag does not represent racism and exclusion, because in it they see genuine, cultivated attachments to their country. They are not focused on asserting the superiority of an identity, but on honouring a meaningful relationship with one’s community and environment – strong roots.

Yet social cohesion feels more fragile lately, partly because of the belief that the ‘rootedness’ of other communities comes at the expense of theirs. Acknowledging that bigotry and a history of colonialism still gnaw at Australia’s national identity feels like a concession or weakness to other communities – but strength can only be built from integrity rather than denial.

It is not talking about a nation’s injustices that threatens its identity, but rather, lies. Weil writes: “This entails a terrible responsibility. Because what we are talking about is recreating the country’s soul, and there is such a strong temptation to do this by dint of lies and partial truths, that it requires more heroism to insist on the truth.”

To those who have been uprooted – whether they are displaced from actual homes, felt excluded or otherised by their fellow neighbours, or felt seething hatred and even violence towards their community – it is difficult to engage with collective life when it lacks common ground built from truth.

If we accept Weil’s claim that rootedness is a fundamental human need, love and criticism of one’s country could be understood as separate species that grow from the same fertile ground: a desire to belong to and steward the country they share.

When it comes to January 26, a call to recognise it as ‘Invasion Day’ is a legitimate criticism because it is truthful to historical events. Australian patriots should not feel threatened if their love of country is deep and sincere; they should take courage that there is a way to mature the national identity in a way that is based in truth, which can allow for the roots of many to grow in its soil.

To Weil, diverse co-existence enriches a community such that “external influences [are not] an addition, but … a stimulus that makes its own life more intense.”

For any patriot, prejudice and lies are the enemy, not their own community.

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran

Marlene Jo Baquiran is a writer and activist from Western Sydney (Dharug land), Australia. Her writing focuses on culture, politics and climate, and is also featured in the book 'On This Ground: Best Australian Nature Writing'. She has worked on various climate technologies and currently runs the grassroots group 'Climate Writers' (Instagram: @climatewriters), which won the Edna Ryan Award for Community Activism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Australian debate about asylum seekers and refugees

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Does 'The Traitors' prove we're all secretly selfish, evil people?

Does ‘The Traitors’ prove we’re all secretly selfish, evil people?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 21 JAN 2026

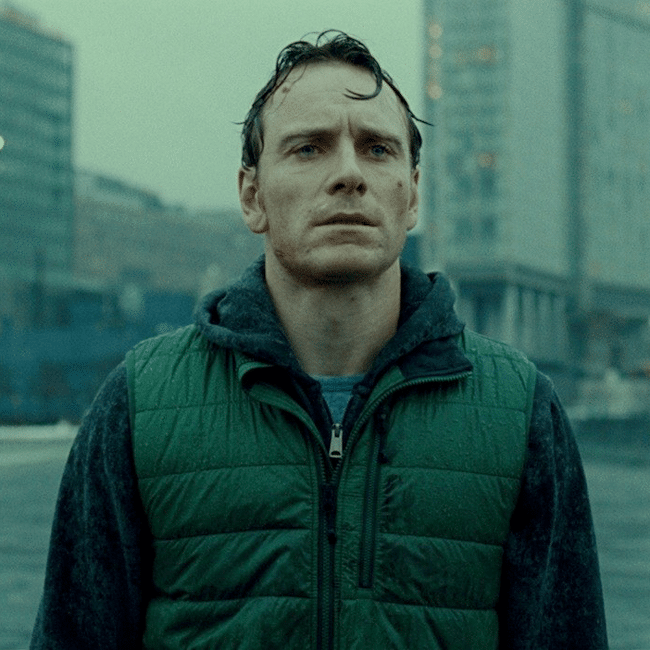

For decades, Alan Carr has been one of British TV’s most unfailingly friendly faces. He’s carved out his niche thanks to a persona modelled on your best friend after a few chardonnays; fun and occasionally rude, but always deeply, resolutely kind. Which is precisely why his maniacal turn on Celebrity Traitors was such a headline-grabbing event.

The highly successful reality show is essentially a glorified game of heads down thumbs up: out of a group of contestants, a select few are secretly designated as “the traitors”, able to dispatch other contestants. The non-traitors must work together to identify the bad apples in their midst – if they do, then they walk home with prize money. If they don’t, then the traitors win.

Almost as soon as he discovered he was a traitor, Carr went to work dispatching his other contestants with a single-minded intent. In an early shocking moment, he even booted off his real-life good mate Paloma Faith, the speed and severity with which he went about his work rivalled only by his masterful manipulation of those around him. Time and time again, he actively leveraged his kindly persona, playing up his inherent trustworthiness. And in the face of accusations, he pleaded his innocence.

It worked. Carr ended up walking away with the biggest haul of the season – but not without breaking down in tears, a sudden flash of guilt overwhelming him.

Which begs the question: does self-interested behaviour actually benefit the self? And moreover, is it really true that when given the slightest motivation for unethical action, most of us would sell out, and “murder” our best mate?

The social contract and the state of nature

The question of what incentive people have to remain ethical is oft-debated in the annals of philosophy. One answer, provided by the theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau, is based on the perceived inherent nastiness at the heart of human beings. According to Rousseau, we organise ourselves into societies where we all agree not to harm or steal from one another, in order to avoid what he called “the state of nature.”

According to Rousseau, the state of nature is a fundamentally lawless societal structure, where individuals do what they want, when they want: this, he says, is how it goes in the natural world, where birds steal each other’s eggs, and lions tear sick zebras limb from limb. There’s total freedom in the state of nature, sure, but it’s not particularly pleasant.

The social contract is a means, therefore, of playing to people’s self-preservation drive, rather than their compassion for their fellow human beings. In the social contract, we all collectively agree not to harm or steal from the other, but only because we want to ensure a world where they don’t harm or steal from us. On this picture of human nature, we’re all chomping at the bit to go full Alan Carr, and betray those around us for our own good – but we don’t, simply in order to avoid getting Alan Carr’d by someone else.

One second away from nastiness

This belief in our fundamentally selfish nature was reinforced throughout the post-war period, where a number of psychological studies aimed to prove that human beings will unleash unkindness with only the lightest of pressures. The most famous such study was the Stanford Prison Experiment, where a group of unassuming civilians were ordered to roleplay being either a jailor or an inmate. Quickly, the jailors went mad with power, escalating the roleplay to such a dangerous level that the whole experiment had to be aborted.

The Stanford Prison Experiment was precisely so shocking because the jailors didn’t even have a pot of gold waiting for them at the end of the experiment: they appeared to wield their power for no other reason than they enjoyed it.

A similar conclusion was reached with the Milgram experiment. In that trial, a group of random civilians were ever-so-gently pressured into delivering what they believed were fatal electric shocks to other civilians that were getting answers in a test wrong (the whole thing was actually a set-up; no-one was harmed). Almost all of them went along with the proceedings happily.

Take these conclusions, and the likes of Alan Carr don’t seem as much like the exception to the rule, but the rule itself.

The better angels of our nature

But should we accept these conclusions? For a start, it’s worth noting that participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment were explicitly instructed to behave badly: it wasn’t something that they came up with by themselves. And in the face of Rousseau’s fundamentally lonely and cruel picture of humanity, let’s consider our extraordinary capacity for empathy.

Because here’s the thing: while we do have evidence that people can be led away from their fundamental values by either money or pressure from an authority figure, a la the Milgram experiment, we also have a great deal of evidence that most people feel an automatic, unthinking empathy towards their fellow human beings. Even Philip Zimbardo, one of the key architects of the Stanford Prison Experiment, advanced the theory of “the banality of heroism”. According to such a view, we all have unbelievable reserves of courage and fellow-feeling within us – heroic acts aren’t, actually, outside of the norm, but something that we’re all capable of.

It is worth noting, after all, that people who are led to act in a self-interested way are exactly that: led astray. Without intervention, people have a fundamentally collective view of humanity. Sure, we can be manipulated. But we all have a natural, unthinking goodness.

Which might then explain Alan Carr’s tears at the end of the traitors. While it’s true he was incentivised to behave “badly”, he knew that it was bad. And in an era where individualism and egomania is being pushed down our throats more than ever, we should remember that within us lies a strong sense of right and wrong, and a deep reserve of concern for our fellow human beings – Rousseau be damned.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 JAN 2026

The sequence of events that led to the cancellation of Adelaide Writers Week revolve around two central questions. First, what, if any, should be the limits of free speech? Second, what, if anything, should disqualify a person from being heard? In the aftermath of the Bondi Terror Attack, the urgency in answering these questions has seen the Commonwealth Parliament recalled specifically to debate proposed legislation that will, amongst other things, redefine how the law answers such questions.

Beyond the law, what does ethics have to say about such fundamental matters in which freedom, justice and security are in obvious tension?

I have consistently argued for the following position. First, there should be a rebuttable presumption in favour of free speech. That is, our ‘default’ position is that there should be as much free speech as possible. However, I have always set two ‘boundary conditions’. First, there should be a strict prohibition against speech that calls into question or denies the intrinsic dignity and humanity of another person. Anything that implies that one person is not as fully human as another would be proscribed. This is because every human rights abuse – up to and especially including genocide – begins with the denial of the target’s humanity. It is this denial that makes it possible for people to do to others what would otherwise be inconceivable. Second, I would prohibit speech that incites violence against an individual or group.

As will be obvious, these are fairly minimal restrictions. They still leave room for people to cause offense, to harangue, to stoke prejudice, to make people feel unsafe, and so on. That is why I have come to the view that something more is needed. In the past, I have struggled to find a principle that would allow for the degree of free speech that is needed to preserve a vibrant, liberal democracy while, at the same time, limiting the harm done by those who seek to wound individuals, groups or the whole of society by means of what they say.

In particular, how do you respond to someone who foments hatred of others – but falls just short of denying their humanity?

It recently occurred to me that the principle I have been looking for can be found in the most unlikely of places: the football field. I was never any good at sport and was always the obvious ‘weak link’ in any team. So, I took a particular interest in the maxim that one should “play the ball and not the person”. Of course, the idea is not exclusively one for sport. Philosophy has long decried the validity of the ad hominem argument – where you attack the person advancing an argument rather than tackle the idea itself. Christianity teaches one to ‘loathe the sin and love the sinner’. In any case, whether one takes the idea from the football field or the list of logical fallacies or from a religion, the idea is pretty easy to ‘get’. In essence: feel free to discuss what is being done – condemn the conduct if you think this justified. However, with one possible exception, do not attack those whom you believe to be responsible.

The one possible exception relates to those in positions of power – where a decent dose of satire is never wasted. That said, the powerful can make bad decisions without being bad people – and calling their integrity into question is often cruel and unjustified. Beyond this, if powerful people preside over wrongdoing, then let the courts and tribunals hold them to account.

The ‘play the ball’ principle commends itself as a practical tool for distinguishing between what should and should not be said in a society that is trying to balance a commitment to free speech with a commitment to avoid causing harm to others. It is especially important that this curbs the tendency of ‘bad faith’ actors (especially those with power) to cultivate an association between certain ideas and certain people. For example, we see this when someone who merely questions a political, religious or cultural practice is labelled as a ‘bigot’ (or worse).

In practice, we will now explicitly apply the ‘play the ball’ principle when curating of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) – adding it to the matrix of issues we take into account when developing and presenting the program. FODI seeks to create spaces where it is ‘safe to’ encounter challenging ideas. For example, it should be possible to discuss events such as: the civic rebellion and repression in Iran, the Russian war with Ukraine, Israel’s response to Hamas’ terror attack, and so on … without attacking Iranians, Shia, Russians, Ukrainians, Israelis or Palestinians. Indeed, I think most Australians want to be able to discuss the issues – no matter how challenging – knowing that they will not be targeted, shunned or condemned for doing so.

I recognise that there are a couple of weaknesses in what I have outlined above. First, I know that some people identify so closely with an idea that they feel personally attacked even by the most sincerely directed question or comment.

Yet, in my opinion, a measure of discomfort should not be enough to silence the question. We all need to be mature enough to distinguish between challenges to our beliefs and threats to our identity.

Second, while the prohibition against the incitement of violence is clear, the other two I have proposed are much more ambiguous. As such, they might be difficult to codify in law.

Even so, these are principles that I think can be applied in practice – especially if we are all willing to think before we speak. A civil society depends on it.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

ExplainerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 14 JAN 2026

Ethical non-monogamy (ENM), also known as consensual non-monogamy, describes practices that involve multiple concurrent romantic and/or sexual relationships.

What it’s not

First up, it’s important to distinguish the two types of non-monogamy that are often conflated with ENM:

Polygamy, the most prominent kind of culturally institutionalised non-monogamy, is the practice of having multiple marriages. It is a historically significant practice, with hundreds of societies around the world having practiced it at some point, while many still do.

Infidelity, or non-consensual non-monogamy, is something we colloquially refer to as cheating. That is, when one or both partners in a monogamous relationship engage in various forms of intimacy outside of the relationship without the knowledge or consent of the other.

All-party consent

So, what makes ethical non-monogamy, then?

One of the defining features of ethical non-monogamy is its focus on consent.

Polygamy, while it can be consensual in theory, more often occurs alongside arranged marriages, child marriages, dowries and other practices that revoke the autonomy of women and girls. Infidelity is of course inherently non-consensual, but the reasons and ways that it happens inversely influence ENM practices.

Consent needs to be informed, voluntary and active. This means that all people involved in ENM relationships need to understand the dynamics they’re involved in, are not being emotionally or physically coerced into agreement, and are explicitly assenting to the arrangement.

Open communication

There are a multitude of ways that ENM relationships can operate, but each of them relies on a foundation of honesty and effective communication (the basis of informed consent). This often means communicating openly about things that are seen as taboo or unusual in monogamous relationships – attraction to others, romantic or sexual plans with others, feelings of jealousy, vulnerability, or inadequacy.

While all ENM relationships require this commitment to open communication and consent, there can be variation in how that looks based on the kind of relationship dynamic. They’re often broken up into broad categories of polyamory, open relationships, and relationship anarchy.

Polyamory refers to having multiple romantic relationships concurrently. Maintaining ethical polyamorous relationships involves ongoing communication with all partners to ensure that everyone understands the boundaries and expectations of each relationship. Polyamory can look like a throuple, or five people all in a relationship with each other, or one person in a relationship with three separate people, or any other number of configurations that work for the people involved.

Open relationships are focused more on the sexual aspects, where usually one primary couple will maintain the sole romantic relationship but agree to having sexual experiences outside of the relationship. While many still rely on continued communication, there is a subset of open relationships that operate on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. This usually involves consenting to seeking sexual partners outside of the relationship but agreeing to keep the details private. Swinging is also a popular form of open relationship, where monoamorous (romantically exclusive) couples have sexual relations with other couples.

Relationship anarchy rejects most conventional labels and structures, including some of the ones that polyamorous relationships sometimes rely on, like hierarchy. Instead, these relationships are based on personal agreements between each individual partner.

What all of these have in common is a firm commitment to communicating needs, expectations, boundaries and emotions in a respectful way.

These are also the hallmarks of a good monogamous relationship, but the need for them in ethical non-monogamy is compounded by the extra variables that come with multiple relationship dynamics simultaneously.

There are many other aspects of ethical relationship development that are emphasised in ethical non-monogamy but equally important and applicable to monogamous ones. These includes things like understanding and managing emotions, especially jealousy, and practicing safe sex.

Outside the relationships

Unconventional relationships are unrecognised in the law in most countries. This poses ethical challenges to current laws, including things like marriage, inheritance, hospital visitation, and adoption.

If consenting adults are in a relationship that looks different to the monogamous ones most laws are set around, is it ethical to exclude them from the benefits that they would otherwise have? Given the difficultly that monogamous queer relationships have faced and continue to face under the law in many countries, non-monogamy seems to be a long way from legal recognition. But it’s worth asking, why?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Daniel Finlay 8 JAN 2026

As a 16-year-old, I argued with my vegan friend about the various faults in his logic: how he couldn’t possibly be healthy, how we were meant to eat animals, and all the rest. I never could have imagined how embarrassed it would make me many years later.

I wasn’t particularly familiar with veganism as a teenager, but I have always loved animals. While the fervour to prove it wrong dissipated, my knowledge and exposure to it remained very minimal, like most people’s. A little later, I briefly dated someone who was vegetarian, who inevitably but mostly passively increased my exposure and knowledge. I decided to start looking into the validity of my confident preconceptions and realised that they were either completely unfounded or just exaggerated. It wasn’t many years later when I woke up in the middle of the night and decided that I needed to change my actions.

Veganuary

Coincidentally, 2014 was the year that I began changing my lifestyle to better reflect my values – the same year that a British nonprofit began an annual challenge called Veganuary: a call for people to try eating as if they were vegan for the first month of the year. You sign up for free and are provided with daily emails for a month that include information like recipes, cookbook pages, meal plans and general advice for how to navigate the change in habits.

All of this is well and good if you’re already curious about the idea of reducing your animal consumption, but what if you’re not? Let me try and pique your curiosity.

Why you should care

You might already consider yourself someone who cares. Most people do love animals in theory. If you see an injured bird, a run-over kangaroo, or an abused dog, you’re likely to have a compassionate response. But decades of socialisation, billions of dollars in misrepresentative marketing, and the ever-increasing distance between consumers and production means it’s easier than ever to ignore how our values contradict our everyday actions.

So please indulge me by considering the following responses to common arguments for eating animals.

To begin, let’s get the practical stuff out of the way:

Where will I get my protein? We need meat/dairy/eggs to give us all the nutrients we need.

This argument is as unfounded as it is ubiquitous, and one I wasn’t immune to earlier in my life either. Unfortunately, agricultural lobbying groups are much better at getting into the minds of average consumers, otherwise it would be common knowledge that all major dietetic associations agree on the safety (and benefits) of balanced vegan diets (and all types of vegetarian diets). That’s not to demonise the health of any other kind of balanced diet – you can be perfectly healthy on a regular omnivorous diet – but the ethical argument for showing compassion to animals doesn’t require it to be healthier than eating animals, only that it’s not bad for us. The overwhelming evidence shows that it is not.

The question is not “can I?” but “how would I like to?” That’s why something like Veganuary is such a good introduction, because having the initial support to change your shopping and eating habits makes the transition much easier.

It’s too hard.

Maintaining a balanced omnivorous diet is also too hard for most Australians – doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try! Sometimes we have to do difficult things for our own good or the good of others. You will likely find though, as I did, that the hardest part of changing your lifestyle is the social aspect. People can be judgemental, defensive, aggressive, and downright cruel despite your best attempts to minimise the impact that your choices have on others. Contrastingly, changing habits can be difficult in the short term but they soon become second nature. Staple recipes are easily replaced and substituted with similar-tasting alternatives.

Okay so maybe it won’t make my life worse personally, but it’s so bad for the environment. All those almond trees and soy crops use so much water and cause deforestation. We need animals to feed everyone.

Almond water usage obsession arose initially during the early-mid 2010s Californian droughts, where the majority of the world’s almonds are grown, at a time when almond consumption was skyrocketing. I’m not going to rush to almond’s defense, as we should definitely be prioritising mass consumption of soy and oat milk instead, but if we do want to compare it to the animal-derived alternative then almond is still better, using almost half the amount of water and causing almost five times less CO2 emissions.

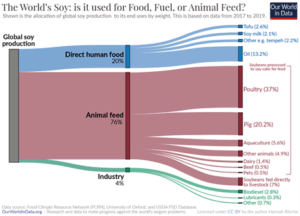

The idea that the soy used for soy milk, tofu, tempeh, etc is driving deforestation is another common myth:

“In fact, more than three-quarters (77%) of global soy is fed to livestock for meat and dairy production. Most of the rest is used for biofuels, industry, or vegetable oils. Just 7% of soy is used directly for human food products such as tofu, soy milk, edamame beans, and tempeh.”

Even further than this, the amount of land cleared for cow pastures is over 7 times that for total soy production. If you’re worried about the environment, reducing or eliminating your animal consumption is the best place to start.

I’ve heard that farming vegetables kills more animals (mice, insects, etc) than eating meat, so if we care about animals, we should really keep eating them.

As we’ve seen, most of these crops go to feeding farmed animals, which means that it is still much preferable to consume these crops ourselves, rather than producing magnitudes more to feed other animals to be killed. The same logic applies if you’re someone who would like to argue that plants have feelings, too.

If you’d like to read more about the arguments against veganism, please see here.

Starting the year right

The overarching consideration here from an ethical standpoint is to reduce unnecessary suffering. For me, this comes mainly from a consequentialist perspective. Suffering is bad, we want to see and contribute to less of it. Eating meat, dairy and eggs necessitates immense amounts of unnecessary suffering and death (even if you think killing an animal that lived a good life is okay, we cannot feed the world with that kind of production – factory farms exist to fill the demand). Therefore, we should stop contributing to that demand.

My suggestion isn’t to make a permanent change overnight, but simply to try something new. You can join millions of other people around the world who are trying out a month of reduced animal harm through Veganuary. Or maybe you’re someone who says things like “I could go vegan except I love cheese too much”. Well, use the start of this year to try being vegan except for cheese. You’ll probably find that the hardest part of doing good is taking the first uncomfortable step.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

The Bondi massacre: A national response

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 JAN 2026

What is the best response to the massacre of Jewish people at Bondi Beach? I ask that question knowing that the best response may not be the most popular.

For example, the debate about whether or not there should be a Federal Royal Commission has made it abundantly clear that people can reasonably and sincerely disagree about what should be done. The same debate has also revealed that some people have deliberately (and others inadvertently) politicised what should be a matter of broad national consensus – with the ideal response being of a kind that meets a number of core criteria. If ever there was a time to set politics aside in favour of a singular compassion for the Jewish Community and a high regard for the national (rather than partisan) interest, then this was it.

Although united in grief and anger, the Jewish Community is not of a single mind about what should now be done. Differences of opinion are to be expected. It is wrong to expect any group of people to hold a common position simply because they share aspects of identity. Furthermore, while the Jewish Community was the explicit target of the terrorists’ attack – and bore the brunt of the carnage – they are not the only Australians to have been wounded by the murderous rampage that took place on the first night of Hanukkah. The whole nation has been scarred … and now a host of other communities are left to ask, “What caused this to happen? What can be done to prevent this in the future? Who’s next?”.

Bearing all of this in mind, I have come to the conclusion that the best possible response cannot lie in a single measure. Instead, I think the whole nation will be best served by a multi-layered approach. Importantly, such an approach would see the Commonwealth Government go well beyond where it currently stands – but in a direction that, I propose, eclipses what has been called for so far.

Each element of our national response needs to be ‘fit-for-purpose’; tailored to meet a specific need. So, what are those needs? First, the Jewish Community needs answers about what caused the Bondi Massacre – and how it might have been prevented. Second, the nation needs to know if there is anything more that could have been done by our national intelligence and security services to identify and therefore prevent the terrorists from acting. Third, we all need to understand the genesis of hate-crimes (of which antisemitism is an especially virulent, but not the only, form) in Australia – and how this might be combatted in favour of resilient bonds of social cohesion that would enable us to maintain a vibrant, multicultural society in which every person can flourish, free from fear or prejudice.

The first need will be met by the proposed NSW Royal Commission that enjoys the unfettered support of the Commonwealth Government and its departments and agencies. That support needs to be offered with the whole-hearted endorsement of the Prime Minister and unwavering direction from his Cabinet. The Commonwealth should offer binding undertakings to hold to account any of its officers, including members of past and present Commonwealth governments, who are found by the Royal Commission to have contributed to the events in Bondi – either by act or omission. Under these conditions, the proposed NSW Royal Commission will be in a position to address all of the issues arising out of the specific terrorist attack of 14 December.

The second need will be met by the Richardson Review. It will be focused and completed within a relatively short period of time. Anyone who knows or who has worked with Dennis Richardson AC knows that the inquiry will be thorough and exacting. The general public may not see all that he finds and recommends – as national-security considerations will take priority for the sake of us all. However, we can trust that nothing will be overlooked.

The third need can be answered by a National Commission of Inquiry. Unlike a Royal Commission that has a defined legal form – and often seeks to find fault and punish wrongdoers – this Commission would be required to look at the deeper causes of which the Bondi Massacre is a treacherous and violent eruption. Those causes affect multiple communities – indeed, they are a cancer eating away at the soul of Australia. The Commission should have broad powers – but it should especially be enabled to convene individuals and groups from across the nation – to hear the stories of what is happening, the impact of hatred and what can be done to prevent this from metastasising into violence.

In my opinion, we should also put the lens on multiculturalism so that rather than merely celebrating the worthy characteristics of separate communities, we learn how to strengthen the bonds between them – and commit to doing so in practice.

I know that there will be some people in the community, especially the Jewish Community, who would prefer to see the Prime Minister establish a Royal Commission to investigate the scourge of antisemitism. There is something distinctive about the hatred directed at Jews – almost unfathomable given its dark persistence over millennia. However, what I have in mind would allow the Jewish experience to be given full voice – but in conditions where we see how it relates to the experience of others in the community. In itself, that will help forge common bonds – as always happens when we see ourselves reflected in the lives of others. Given the searing nature of events, a proposed Commission should prioritise its examination of antisemitism, before all else, reporting on this within twelve months of being established.

In putting forward this proposal, I sincerely believe that nothing will be lost – and much will be gained. I hope that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese might establish a Commission that embraces the whole nation – in all of its marvellous diversity – in order to find light at this terrible moment of darkness.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture

Read me once, shame on you: 10 books, films and podcasts about shame

Feeling our way through tragedy

The emotions we feel in the wake of a tragedy, like the Bondi Beach shooting, are as intense as they are natural. What matters is how we act on them.

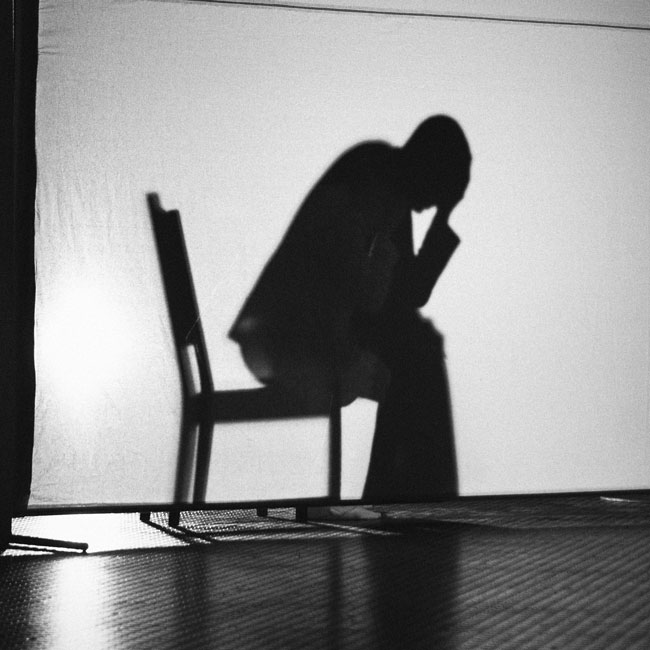

It was a typical relaxed summer Sunday evening. We had just finished dinner and I was on the couch watching TV while my wife was in the other room catching up with family over a video call. Then a wayward notification caused me to idly glance at my phone. A headline popped up on the screen, I caught my breath and switched on the news.

And in a matter of moments, the peace was shattered as the news came in that two men had opened fire on a group of people enjoying their own relaxed summer Sunday evening celebrating Hanukkah on Bondi Beach. A wave of emotions followed: horror, grief and outrage, followed by a gnawing sense of uncertainty. Were any of my friends or family there? What could drive someone to commit such an atrocity? Is anywhere safe?

These are typical emotions when confronted by sights such as these. The feelings well up from our bellies, fill our chest, overwhelm our minds. They are as primitive as they are potent. And they demand closure.

Yet emotions like these can be channelled in many different ways. Some forms of emotional closure are healthy. But other courses can end up causing more harm, either to ourselves or to others. And while it is easy to let these types of emotions consume us, it is crucial that we act on them ethically.

Horror and hope

Many creatures experience fear. It is a natural response to threat, and a potent motivator to remove ourselves from its presence. But our species is unique – as far as we know – in our ability to experience horror. Horror is also bound up with shock, disgust and dread. It is a response to the most acute violations of our humanity. The thing is, we don’t only experience horror when we are under threat, but when someone else is threatened. Underneath horror is a recognition of our shared sacred humanity and a revulsion at its desecration.

The problem is that the sense of horror triggered by an attack such as that at Bondi Beach on 14 December 2025 can change the way we see the world. In our aroused state, we become hyper vigilant to cues that might indicate future threats. And those cues will be associated with the location of the shooting, perhaps making us reluctant to go to Bondi Beach, or even causing us to fear going out in public at all.

If we allow emotion to take over, it can make the world feel less safe and other people seem more threatening.

But that response overlooks the fact that, despite the magnitude of the atrocity, this is an incredibly rare event perpetrated by only a few people. The fact that our feeling of horror is shared by millions of others around Australia and the world should serve as a reminder that the vast majority of us care deeply about our shared humanity, and it is those people that make the world safe. Should we retreat from the world out of fear, we do ourselves, and every decent horrified person around us, a disservice.

Following horror might be an overwhelming grief at the pain and suffering inflicted upon innocent people. This grief can lead to a feeling of powerlessness and despondency, one that again nudges us to retreat from the world. But, as painful as it is, our grief is proportional to our love. If we didn’t care for the lives of others – even people we have never met and will never know – then we wouldn’t feel grief. So we needn’t let grief strip us of our agency. Instead, we can let it remind us to lean into love and motivate us to reach out to others with greater patience and understanding.

A fire for justice

Possibly the most dangerous emotion in this list is outrage. This is another primitive emotion that motivates us to correct wrongdoing and punish wrongdoers. Outrage demands satisfaction, but it’s often not fussy about how that satisfaction is achieved. Great evils have been committed at the hand of outrage, and great injustices perpetrated to satisfy its call.

We must acknowledge when we feel outrage but be wary of its call to immediately find someone to blame and punish. Within an hour of the shooting, the media was already mentioning a name of one of the attackers, feeding the audience’s hunger for justice. But in its haste, it caught up an innocent man who then experienced unwarranted threats. Others rushed to blame the authorities for failing to prevent the attack or refusing to combat antisemitism.

Even when things look clear at first glance, we must remind ourselves that it’s all too easy to blame the wrong person or seek punishment just for the sake of satisfaction. And sometimes there is no one person to blame. Sometimes the causes of an atrocity are complex and interlaced. Sometimes there were multiple causes and nothing anyone could have done to prevent it. So we must temper outrage with a deeper commitment to genuine justice, lowering the temperature and working to understand the whole picture before calling for punishment.

I acknowledge that it can be difficult to pause in the heat of the moment, especially when we only have a fragmentary grasp of what’s going on and what caused it.

In times of uncertainty or ambiguity, we crave clarity and certainty. We seek out and latch on to the first available narrative that seems to make sense of a great tragedy. We like the feeling of being certain more than we like doing the work to interrogate our beliefs to ensure they warrant certainty.

We thus have a tendency to be drawn to narratives that align with our pre-existing beliefs or biases. Uncertainty and ambiguity can be like a Rorschach test. The patterns we see tell us more about ourselves than reality. If we don’t want to exacerbate injustice by generating or sharing false narratives that can cause real harm, we need to learn to sit with the uncertainty and dwell in the ambiguity. We are not naturally inclined to do so, but that only means we need to practice getting better at it.

The very fact we typically experience emotions like horror, grief, outrage and uncertainty speak to our deeper humanity. They speak to how much we care about others and living in a world where everyone deserves to be safe and thrive. If we allow the better angels of our nature to rise to the surface, and resist the temptation to satisfy our emotions in ways that cause more harm, we can respond in a genuinely ethical way.

Image by ZUMA Press, Inc / Alamy

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 DEC 2025

On behalf of everyone who works at The Ethics Centre – our board, staff and volunteers – I am writing to all of our members and supporters to offer our heartfelt sympathy to those affected by the terrorist attack that took place, in Bondi, last night.

Some might observe that this is not the biggest atrocity to have taken place in the world this year. However, I do not believe that atrocities should be ranked according to the numbers of people killed and maimed. What defines such events, as evil, lies in the perpetrator’s intent to harm people; not because of what they have done, or what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Last night was not an indiscriminate act of terror. People were targeted merely for being Jewish – men, women, children … people of every type and description. Whether you lived or died had nothing to do with one’s politics or opinions about the world. Simply being Jewish – indeed, simply being in the midst of the Jewish community – was enough for you to be targeted. This was antisemitism in its most violent form.

As I write this note, we still do not know what motivated the terrorists. However, nothing can make good what they did – cold-blooded murder can never be justified … no matter who does the killing, no matter who is the victim, no matter how many reasons are advanced.

Now, I fear that the cycle will take another turn for the worse. Members of other communities will fear that they will be tarred with the same brush as the terrorists – no matter what they have done, no matter what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Surely, surely it is time to stop this vicious wheel from turning.

At The Ethics Centre, we believe in the intrinsic dignity of all persons – without exception. This recognition has no boundaries and, difficult as it may be, must extend even to those who visit terror upon us. At times like this, we should embrace our common humanity – and not give way to those who would stoke and exploit divisions for their own ends.

Many people will be hurting today – even if far removed from the carnage. Many will be angry or confused, or feeling helpless or just numb. I think I have felt all of those emotions since the tragic events of last evening began to unfold. However, in the midst of all of this, we can hold onto the fact that what happens next is not inevitable.

Our governments will take the lead in providing security – but only we, the people, can create the conditions of ‘belonging’ in which every person can feel safe in the warm embrace of a society that recognises the intrinsic dignity of all. In this, let’s not forget the bravery of those who confronted the gunmen, who rendered first aid, who comforted the dying or offered sanctuary within their homes. These people show what is possible when the good in us comes forth.

Making and sustaining just such a society – even in the face of terror – is what each of us can do. I hold onto that – and in the midst of pain and confusion hope you might do the same.

Image: Paul Lovelace / Alamy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics programs work in practise

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights