Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Joshua Pearl 22 AUG 2022

Pick up a first-year undergraduate economics textbook on tax and you’ll likely be apprised that there are three desired features of a tax policy: simplicity, efficiency and fairness.

The importance of the first two are somewhat obvious. Simplicity, because taxpayers need to understand how to comply with the tax system. Efficiency, because if people can easily change their behaviour to avoid paying tax, there won’t be much revenue to fund government expenditure. But fairness, the third desired feature of tax policy, is more nebulous.

Tax fairness is important not merely because economists tell us so. Rather, Australia needs to consider tax fairness for reasons such as: ensuring the continued political legitimacy of the Australian governments; because tax inherently deals with issues of inequality; and for the very practical reason of helping us deliver tax system reform.

In a liberal country such as Australia, a well-accepted norm is that restrictions on individual freedom must be justified. And in liberal philosophy, the dominate way to justify government restrictions is by considering a “public reason” test, well-articulated by influential twentieth century philosopher John Rawls’ liberal principle of legitimacy:

“Political power is legitimate only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution (written or unwritten) the essentials of which all citizens, as reasonable and rational, can endorse in the light of their common human reason”.

Restrictions that are arbitrary, unfair, exploitative or focus on benefitting a few at the expense of the many, undermine political legitimacy because they cannot be justified. Prohibiting the Nazi swastika might be justifiable because people have a right not to be vilified or feel physically threatened. But prohibiting tattoos or facial piercings, dress wear, beach outfits or more sinisterly, citizenship based on skin colour, because they offend certain sensibilities, are not legitimate forms of government coercion because they cannot be reasonably justified using the public reason test.

Rawls considered the public reason test would apply to areas in the public domain relating to judges, government officials, and politicians. And the public reason test applies to taxation as much as any other act of government coercion. Taxation, the compulsory, unrequited payment to government, is quite literally nothing, if it is not coercive. In Australia we pay around $600bn in tax each year, over $40,000 per working person.

If the tax system is unfair, it cannot be justified. And taxation that is unjustified etches away at the political legitimacy of the Australian government and, in turn, Australian democracy.

The two primary functions of tax are:

1. to fund public goods such as military, transport, education, police and the judiciary

2. to redistribute wealth and income, through policies such as pension payments, unemployment payments, childcare and paid parental leave. Therefore, because tax impacts wealth and income distribution, as well as economic inequality, the tax system has inherent fairness implications.

Wealth and income distribution, the second function of tax, determines economic inequality, an inherent fairness issue. And to determine the required tax level requires consideration of the level of wealth and income inequality we consider fair. It might be said this issue is more relevant today than in other times in our recent history; Australian inequality measures have increased steadily since the 1980s. But even if we consider current wealth and income inequality levels as acceptable, presumably there is a limit. It is unlikely that Australia would still be considered a fair country if we were a nation of 20 billionaires and twenty million paupers.

One might be tempted to try and decouple tax issues from fairness issues by claiming Australia and our tax system is fair so long as we have equality of opportunity; instead of worrying about wealth inequality and tax, we should focus on realising Australian cultural values such as a “fair go”, a value synonymous (according to the citizenship tests new citizens take) with “equality of opportunity”.

However, a “fair go” isn’t free. For a rich child and a poor child to have the same opportunities with respect to education, learning and a successful career, we require tax. For equality of opportunity to exist, the rich parent needs to contribute more tax to fund our education institutions than what the poor parent can afford. Here, issues of tax and fairness are bound.

A less philosophical reason as to why it’s important for Australia to consider tax system fairness relates to tax reform. The consensus among economists is the Australian tax system is uncompetitive, inefficient, too complex and out of date. And they may have a point.

Australia hasn’t had meaningful tax reform for decades and is out of step with international best practice. The Federal Government deficit is large and growing, thanks in part to the former government’s COVID-19 splurges (some necessary, some arguably less so). And Australian government debt is forecast to reach a trillion dollars in the coming years, a level that may limit or preclude policy responses to future wars, pandemics, financial crises or property market crashes (and the implications of muted policy options is not merely no pink batts or no JobKeeper in time of catastrophe, but no jobs, high unemployment and potential social unrest).

Yet despite the arguments of a host of economic experts, such as ANU’s Professor Robert Breunig the former Federal Treasury head Dr. Ken Henry, OECD and IMF mandarins, to name but a few, the Australian tax system remains as it is. While tax reform by its nature is challenging (there is always a loser – someone will be paying more), it’s hard not to think the focus on tax efficiency, tax competitiveness, tax complexity and so on and so forth, has failed to create the “burning platform” needed to drive policy change. A greater focus on the fairness of the Australian tax system may be what is required to buttress the valid but sometimes technical economic arguments for Australian tax system reform.

Considering fairness of the tax system is important for political legitimacy, inequality and practical reasons. A tax system that is fair strengthens our democracy by ensuring taxation remains justifiable. Tax fairness helps us realise Australian cultural values such as equality of opportunity. And a greater focus on tax fairness might help us undertake meaningful tax reform, delivering a tax system that is simple, efficient and fair.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Political aggression worsens during hung parliaments

BY Joshua Pearl

Joshua Pearl is the head of Energy Transition at Iberdrola Australia. Josh has previously worked in government and political and corporate advisory. Josh studied economics and finance at the University of New South Wales and philosophy and economics at the London School of Economics.

Come join the Circle of Chairs

More than thirty years ago, philosopher and Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff AO placed a dozen chairs in a circle in Martin Place in the centre of Sydney’s busy CBD. Next to them he put up a sign that said: “If you would like to discuss ideas with a philosopher join the circle”.

At first, the circle attracted little more than sidelong glances from curious passers-by. But it wasn’t long before people paused to read the sign, a few of them taking up the offer to occupy one of the chairs and start a conversation. Soon the circle was full and the discussion buzzing.

Simon discovered that many people had an unsated appetite for a different kind of conversation than the one that usually unfolded with friends, family and colleagues or, heaven forbid, online.

This was a kind of conversation where they could open up and express their deepest beliefs and attitudes, where they could ask questions without people presuming the worst about them, where they could have their ideas challenged without feeling judged or threatened, and where they could explore a topic before making up their mind.

Simon returned regularly to Martin Place with his circle of chairs, and each time more and more people stopped by to discuss ideas with him and the others seated around the circle. People started to come from far and wide to join in the conversation, having heard about it from friends or family. Rarely were chairs left empty.

With his Circle of Chairs, Simon had effectively created a space where people were safe to talk about difficult and challenging subjects. What made it work was that it wasn’t just free and unregulated discourse. Simon was able to bring his skills as a philosopher to facilitate the conversation and set appropriate norms that enabled people to speak and listen in good faith in ways that are difficult to achieve in everyday conversations.

This exercise all those years ago served as a crucial spark that led to the creation of The Ethics Centre, which still works to create safe spaces to discuss difficult and important subjects to this day.

Welcome to the conversation

Presented by The Ethics Centre, Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) is Australia’s original disruptive festival. By holding uncomfortable ideas up to the light and challenging thinking on some of the most persevering and difficult issues of our time, FODI aims to question our deepest held beliefs and desires.

Which is why Dr Simon Longstaff’s original vision of a Circle of Chairs is returning to this year’s FODI, in partnership with JobLink Plus. With six sessions held over the two days, we’re inviting festival goers to take up a chair and sit shoulder to shoulder with leading philosophers Dr Simon Longstaff, Dr Tim Dean and Dr Kelly Hamilton, who will be joined by special guest conversationalists to unpick some of modern life’s most dangerous ethical dilemmas.

Will you agree with your fellow FODI attendee’s views? Pull up a chair and join or simply watch the guided conversations unfold as together we examine how we’re really feeling, thinking and doing.

We hope to see more safe spaces opening up outside of FODI to help us all have the opportunity to share our authentic views and tackle the most challenging, and important, questions that we face today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Corporate whistleblowing: Balancing moral courage with moral responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2022

Banking and finance businesses can’t afford to ignore the streamlining and cost reduction benefits offered by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Your business can’t effectively beat the competition marketing any product in the 21st century without using big data and AI. Given the immense amount of consumer data available – and the number of channels, segments and competitors – marketers need to use AI and algorithms to operate successfully in the online environment.

But AI must be used prudently. Business managers must be meticulous in setting up rules for the algorithms’ decision making to prevent AI, which lacks a human’s inherent moral and ethical guiding force, from targeting ads towards unsuitable or vulnerable customers, or making decisions that exacerbate entrenched racial, gender, age, socio-economic, or other disparities and prejudices.

The Banking and Finance Oath’s 2021 Young Ambassadors recognised a gap in the research and delivered report: AI driven marketing in financial services: ethical risks and opportunities. It unravels the complexities of AI’s impact across the financial services industry and government, and establishes a framework that can be applied to other contexts.

In a marketing environment, AI can be used to streamline processes by generating personalised content for customers or targeting them with individual offers; leveraging customers’ data to personalise web and app pages based on their interests; enhancing customer service with chatbots; and supporting a seamless purchasing journey from phone to PC to in-person at a storefront.

Machine learning algorithms draw from immense data pools, such as customers’ credit card transactions and social media click-throughs to predict the likelihood of customers being interested in a product, whether to show them an ad and what ad to show them. But there are ethical risks to navigate at every step – from the quality of the data used to how well the developers and business managers understand the business objectives.

Using AI for marketing in financial services comes with two significant risks. The first is the potential for organisations to be seen as preying on people in vulnerable circumstances.

AI has no moral oversight or human awareness – it simply crunches the numbers and makes the most advantageous and profitable decision to lead to a sales conversion.

And if that decision is to target home loan ads at people going through a divorce or a loved one’s funeral, or to target credit card ads at people who are unemployed or living with addiction, without proper oversight, there’s nothing to stop it.

The other risk is the potential for data misuse and threats to privacy. Customers have a right to their own data and to know how it’s being used – and what demographics they’re being placed in. If your data’s out of date or inaccurate, or missing in sections, you’ll be targeting the wrong people.

All demographics – including racial background, socio-economic status, and individual psychological profile – have the potential to be misused by AI to reinforce gender, racial, age, economic and other disparities and prejudices.

Most ethical failings in AI-driven marketing campaigns can be traced back to issues with governance – poor management of data and lack of communication between developers and business managers. These data governance issues include: siloed databases that don’t share definitions; datasets that don’t refresh quickly enough and become outdated; customer flags that are incorrect or missing; and too many people being designated as data owners, resulting in the deferral of responsibility.

In human driven decision making, there’s a clear line of command, from the Board, to management, to the frontline team. But in AI-driven decision making, the frontline team is replaced by two teams – the AI developers and the team of machines.

Communication gaps emerge where management may not be familiar with instructing AI developers and the field’s highly technical nature, and the developers may not be familiar with the jargon of the business. Training across the business can act to fill these gaps.

Before any business begins to integrate AI into its marketing (and overall) strategy, it’s crucial that it adopt a set of basic ethical principles, these being:

- Beneficence (or do good): personalise products to improve the customer’s experience and improve their financial literacy by delivering targeted advice.

- Non-maleficence (or do no harm): ensure your AI marketing doesn’t target customers in inappropriate or harmful ways.

- Justice: ensure your data doesn’t discriminate based on demographics and exacerbate racial, gender, age, socio-economic or other disparities or stereotypes.

- Explicability: you need to be able to explain how your AI system makes the decisions it does and the relation between its inputs and outputs. Experts should be able to understand its results, predictions, recommendations and classifications.

- Autonomy: at the company level, governance processes should keep humans informed of what’s happening; and at a customer level, responsible decision making should be supported through personalisation and recommendation tools.

The reality is that no business can afford to ignore the benefits AI offers, but the risks are very real. By acknowledging the ethical issues, businesses can seize the opportunities while mitigating the risks, benefiting themselves and their customers.

Download a copy of the report here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Shadow values: What really lies beneath?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pavan Sukhdev on markets of the future

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 AUG 2022

There are certain things that some of us choose and do not choose, to tell those who we work with.

You come in on a Monday, and you stand around the coffee machine (the modern-day equivalent of the water cooler), and somebody asks you: “so, what did you get up to this weekend?”

Then you have a choice. If you fought with your partner, do you tell your colleague that? If you had sex, do you tell them that? If your mother is sick, or you’re dealing with a stress that society has broadly considered “intimate” to reveal, do you say something? And if you do, do you change the nature of the work relationship? Do you, in a phrase, “freak people out?”

These social conditions – norms, established and maintained by systems – are not specific to work, of course. Most spaces that we enter into and share with other people have an implicit code of conduct. We learn these codes as children – usually by breaking the rules of the codes, and then being corrected. And then, for the rest of our lives, we maintain these codes, often without explicitly realising what we are doing.

There are things you don’t say at church. There are things you do say in a therapist’s office. This is a version of what is called, in the world of politics, the “Overton Window”, a term used to describe the range of ideas that are considered “normal” or “acceptable” to be discussed publicly.

These social conditions are formed by us, and are entirely contingent – we could collectively decide to change them if we wanted to. But usually – at most workplaces, importantly not all – we don’t. Moreover, these conditions go past certain other considerations, about, say honesty. It doesn’t matter that some of us spend more time around our colleagues than those we call our partners. This decision about what to withhold in the office is frequently described as a choice about “professionalism”, which is usually a code word for “politeness.”

Severance, the new Apple television show which has been met with broad critical acclaim, takes the way that these concepts of professionalism and politeness shape us to its natural endpoint. The sci-fi show depicts an office, Lumon Industries, where employees are implanted with a chip that creates “innie” and “outie” selves.

Their innie self is their work self – the one who moves through the office building, and engages in the shadowy and disreputable jobs required by their employer. Their outie self is who they are when they leave the office doors. These two selves do not have any contact with, or knowledge of each other. They could be, for all intents and purposes, strangers, even though they are – on at least one reading – the “same person.”

The chip is thus a signifier for a contingent code of social practices. It takes something that is implicit in most workplaces, and makes it explicit. We might not consider it a “big deal” when we don’t tell Roy from accounts that, moments before we walked in the front door of the office, we had a massive blow-up over the phone with our partner. Which may help Roy understand why we are so ‘tetchy’ this morning. But it is, in some ways, a practice that shapes who we are.

According to the social practices of most businesses, it is “professional” – as in “polite” – not to, say, sob openly at one’s desk. But what if we want to sob? When we choose not to, we are being shaped into a very particular kind of thing, by a very particular form of etiquette which is tied explicitly to labor.

And because these forms of etiquette shape who we are, they also shapes what we know. This is the line pushed by Miranda Fricker, the leading feminist philosopher and pioneer in the field of social epistemology – the study of how we are constructed socially, and how that feeds into how we understand and process the world.

For Fricker, social forces alter the knowledge that we have access to. Fricker is thinking, in particular, about how being a woman, or a man, or a non-binary person, changes the words we have access to in order to explain ourselves, and thus how we understand things. That access is shaped by how we are socially built, and when we are blocked from access, we develop epistemic blindspots that we are often not even aware that we have.

In Severance, these social forces that bar access are the forces of capitalism. And these forces make the lives of the characters swamped with blindspots. Mark, the show’s hero, has two sides – his innie, and his outie. Things that the innie Mark does hurt and frustrate the desires of the outie Mark.

Both versions of him have such significant blindspots, that these “separate” characters are actively at odds. Much of the show’s first few episodes see these two separate versions of the same person having to fight, and challenge one another, with Mark striving for victory over outie Mark.

The forces of etiquette are always for the benefit of those in power. We, the workers at certain organisations, might maintain them, but their end result is that they meaningfully commodify us – make us into streamlined, more effective and efficient workers.

So many of us have worked a job that has asked us to sacrifice, or shape and change certain parts of ourselves, so as to be more “professional”. Which is a way of saying that these jobs have turned us into vessels for labour – emphasised the parts of us that increase productivity, and snipped off the parts that do not.

The employees of Lumon live sad, confused lives full of pain, riddled with hallucinations. The benefit of the code of etiquette is never to them. They get paid, sure. But they spend their time hurting each other, or attempting suicide, or losing their minds. Their titular severance helps the company, never them.

This is what the theorist Mark Fisher refers to when he writes about the work of Franz Kafka, one of our greatest writers when it comes to the way that politeness is weaponised against the vulnerable and the marginalized. As Fisher points out, Kafka’s work examines a world in which the powerful can manipulate those that they rule and control through the establishment of social conduct; polite and impolite; nice and not nice.

Thus, when the worker does something that fights back against their having become a vessel for labour, the worker can be “shamed”, the structure of etiquette used against them. This happens all the time in the world of Severance. As the season progresses, and the characters get involved in complex plots that involve both their innie and outie selves, the threat is always that the code of conduct will be weaponised against them, in a way that further strips down their personality; turns them into more of a vessel.

And, as Fisher again points out, because these systems of etiquette are for the benefit of the powerful, the powerful are “unembarrassable.” Because they are powerful – because they are the employer – whatever they do is “right” and “correct” and “polite.” Again, the rules of the game are contingent, which means that they are flexible. This is what makes them so dangerous. They can be rewritten underneath our feet, to the benefit of those in charge.

Moreover, in the world of the show, the characters “choose” to strip themselves of agency and autonomy, because of the dangling carrot of profit. This sharpens the satirical edge of Severance. It’s not just that the snaking rules of the game that we talk about when we talk about “good manners” make them different people. It’s that the characters of the show submit to these rules. They themselves maintain them.

Nobody’s being “forced”, in the traditional sense of that word, into becoming vessels for labour. This is not the picture of worker in chains. They are “choosing” to take the chip, and to work for Lumon. But are they truly free? What is the other alternative? Poverty? And what, actually, makes Lumon so different? A swathe of companies have these rules of etiquette. Which means a swathe of companies do precisely the same thing.

This is a depressing thought. But the freedom from this punishment lies, as it usually does, in the concept of contingency. Etiquette enforces itself; it punishes, through social isolation and exclusion, those who break its rules.

But these rules are not written on a stone tablet. And the people who are maintaining them are, in fact, all of us. Which means that we can change them. We can be “unprofessional.” We can be “impolite”. We can ignore the person who wants to alter our behaviour by telling us that we are “being rude.” And in doing so, we can fight back against the forces that want to make us one kind of vessel. And we can become whatever we’d like to be.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

Reports

Science + Technology

Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 28 JUL 2022

We’re hurtling into a new age where the notion of evidence and knowledge has become muddied and distorted. So which rabbit hole is the right one to click through?

Our world is deeply divided, and we have found ourselves in a unique moment in history where the idea of rational thought seems to have been dissolved. It’s no longer as clear cut what is right and just to believe….So what does it mean to truly know something anymore?

According to Emerson, the number one AI chat bot in the world, “rational thought is the process of forming judgements based on evidence” which sounds simple enough. It’s easy to form judgements based on evidence when the object of judgement is tangible — this cheese pizza is delicious, a cat playing a keyboard wearing glasses is funny. These are ideas on which people from all sides of the political spectrum can come to some form of agreement (with a little friendly debate).

But what happens when the ideas become a little more lofty? It’s human nature to believe that our one’s ideas are rational, well reasoned, and based on evidence. But what constitutes evidence in these information rich times?

We’re hurtling into a new age where even the notion of “evidence” has become muddied and distorted.

So where do we even begin — which news is the real news and what’s the responsible way to respond to the news that someone as intelligent as you, in possession of as much evidence as you, believes a different conclusion?

Philosopher Eleanor Gordon-Smith suggests, “There are many, many circumstances in which we decline to avail ourselves of certain beliefs or certain candidate truths because we’re being very Cartesionally responsible and we’re declining to encounter the possibility of doubt. And meanwhile, those of us who are sort of warriors for the enlightenment of being very epistemically polite and trying to only believe those things that we’re allowed to do so on. The conspiracy theorists, meanwhile, consider themselves a veil of knowledge, which then they deploy in a very different way.”

Who gets to be smart?

Before the Enlightenment, the common man had no real business in the pursuit of knowledge, knowledge was very fiercely guarded by the Church and the Crown. But once it dawned on those honest folk that they could in fact have knowledge, it almost became a moral imperative to seize it, regardless of the obstacles.

Nowadays avoiding knowledge is an impossibility impossible. Access to information has been wholly democratised, if you’ve got a smart phone handy, any Google search will result in billions of possible pages and answers. It’s now your choice to determine which rabbit hole is the right one to click. To the untrained eye, there’s no differentiating between information that is thoroughly researched and fact checked and fake news. And according to Eleanor Gordon-Smith it is this saturation of knowledge has come to define our generation. So much so that the value of knowledge “has been subject to a kind of inflation”.

She asks, “how do you restore the emancipatory potential of knowledge that the Enlightenment founders saw? How do you get back the kind of bravery, the self development, the political resistance, the independence in the act of knowing in this particular moment…is there a way to restore the bravery and the value of knowledge in an environment where it’s so cheap and so readily available?”

It is this saturation of knowledge has come to define our generation. So much so that the value of knowledge “has been subject to a kind of inflation”.

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek suggests that perhaps our mistake is putting the Englightment on a pedestal, that those involved in the Enlightment’s pursuit of knowledge mischaracterised those who came before them as naive idiots. “Modernity is not just knowledge. It’s also on the other side, a certain regression to primitivity. The first lesson of good enlightenment is don’t simply fight your opponent. And that’s what’s happening today.”

Perhaps ignorance really is bliss

In the age of disinformation, misinformation and everything in between, admitting you don’t know something almost feels like an act of rebellion. American philosopher Stanley Cavell, boldly asked “how do we learn that what we need is not more knowledge but the willingness to forgo knowledge” (it’s worth noting that this line of questioning saw his publications banned from a number of American university libraries).

Sometimes it is better to be ignorant because, “true knowledge hurts. Basically, we don’t want to know too much. If we get to know too much about it, we will objectivise ourselves, we will lose our personal dignity, so to retain our freedom it’s better not to know too much.” – Žižek

Žižek however admits that we are in a the middle of the fight. We are not at the end of the story. We cannot afford ourselves this retroactive view in the sense of: who cares what is done is already done? “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, we have to change it. We tried to change the world too quickly without really adequately interpreting it. And my motto would have been that 20th century leftists were just trying to change the world. The time is also to interpret it differently. That’s the challenge.”

When the AI chat bot Emerson is asked, “how can you know if something is true” it responds, “truth is a matter of opinion” and given these tumultuous and divided times we are living through, there is perhaps no truer statement.

To delve deeper into the speakers and themes discussed in this article, tune into FODI: The In-Between The Age of Doubt, Reason and Conspiracy.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Debt means different things to different people. While some are confident to juggle huge amounts of debt spread across a few credit cards, others start hyperventilating at the mere notion of paying a bill a day late.

Debt is also intrinsically linked to our emotional state of mind. Purchasing a new outfit using Buy now, pay later services might trigger an immediate dopamine hit, and leave the trouble of those four pesky payments to a future version of yourself. Or on the larger scale, buying an apartment means taking on the biggest debt most will take on in their lifetime, but it marks a momentous life milestone.

Why is debt so emotional? And what hidden psychological forces shape our attitudes and relationships towards it?

Keep it in the family

Our attitudes towards debt are largely inherited from our family, according to Jess Brady, a financial advisor at Fox and Hare Financial and founder of online community Ladies Talk Money. Brady says debt is not just numbers on a spreadsheet, but rather a complex emotional relationship informed by how we saw our families and friends interact with their finances when we were kids. “It might be shaped by parents separating and having to move from middle class life, to potentially a period where things became really tight from a monetary perspective. And so now, fear and insecurity drive decision making in your money, beliefs or behaviour.”

“It might be that you watched your parents make reckless decisions, which has made you quite fearful about making any decisions. Or quite the opposite that you’re used to having a lot of money and a lot of freedom. Meaning that you spend money without really considering what the consequences are so often it is what we did or didn’t see in a home life environment.”

What’s clear is, there’s no rulebook when it comes to debt and financial management. Whether you’ve grown up with examples of responsible spending or not, the moment you get your first job and your own bank account – you’re on your own, which is why Brady thinks it’s important to supercharge your financial literacy.

“We wrap so much shame and guilt around debt.” If we’re going to start normalising talking about money, then the lessons of accepting and reflecting on the decision-making that got you to this point are valuable.

Jess Brady’s key financial messages for getting ahead of debt and improving financial literacy are:

- Stop identifying as someone who is, “bad with money”: this negative self-talk creates a belief system around excusing bad behaviour.

- The buck stops with you: don’t offload large financial decisions onto others whether that be a partner or a parent.

- Working 9-5: Take responsibility for your own income and embrace the mantra “I decide where and how to spend my own money.”

It’s all about the sell

For some, accumulating debt can feel like sacrificing freedom while for others it’s exactly the opposite. For a lot of people debt is an opportunity, it’s the promise of more, being one step closer to your dreams. Our differing perceptions of taking on debt has a lot to do with how it is marketed.

Taking on debt to go to university, to buy a car or an apartment are all seen as responsible debt associated with big life milestones, but debt is no longer just about buying your dream home, or taking out a credit card for the frequent flyer points. It’s about wanting a new pair of shoes… And thanks to Buy now, pay later services, getting them immediately.

According to Adam Ferrier, a behavioural psychologist and co-founder of Sydney based advertising agency, Thinkerbell, money is marketed with a sledgehammer. “Money used to be marketed by a promise of aspiration. But it feels like that aspirational side of money has been chipped away at, and it’s almost a bit gauche to promise an aspirational lifestyle with money. Debt in this country is marketed very much as an issue and something that you have to get out of and create a sense of urgency, often targeting the less financially literate people in the marketplace.”

But all debt was not created equal, and it’s the rise of Buy now, pay later type debts amongst the younger generations that have a number of financial advisors and writers concerned. According to Jonathan Shapiro, journalist and author of Buy now pay later, the extraordinary story of Afterpay, these services didn’t exactly set out to be unethical. “I think what’s happened is that we convinced ourselves that they are providing some sort of a win-win solution and they are of the belief that something so good and so popular cannot be bad.”

The introduction of companies like Afterpay to the financial lending market means it’s never been easier to fall into the red. And because of the clever way they’re marketed as payment services rather than lenders means they have largely dodged regulation, leading to heavy ethical scrutiny.

“A lot of its success is built around a behavioural hack. If something is $100, it might intimidate a consumer. But if it’s leading to $25 payments over six weeks, it makes it more palatable.”

The dangers of these services are that consumers will spend way more than they had originally intended because when a large price tag is divided over the span of six weeks it feels more manageable. “It’s put the burden on consumer groups to educate themselves. Those who use Afterpay need to be mindful of the risks of booting up a debt trap. Now they might not fall into a debt trap in the same way someone using a credit card might. But what tends to happen is Buy now, pay later users that have overextended themselves sign up for a myriad of other providers, or they stop paying other bills that are more important.”

What’s important is that we begin to normalise conversations about money, about investments, and about debt. We’re living in a time where the way debt is marketed is shifting dramatically, so it’s imperative to improve our financial literacy because our critical thinking skills and understanding what’s right for us has never felt more important.

Life and Debt is available to listen to on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

This podcast is a project from the Young Ambassadors in The Ethics Centre’s Banking and Finance Oath initiative. Our work is made possible by donations including the generous support of Ecstra Foundation – helping to build the financial wellbeing of Australians.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

Reports

Business + Leadership

Productivity and Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why the future is workless

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith 18 JUL 2022

Anyone who has sat through sex ed class in school or the workplace knows how difficult it is to discuss sexual ethics.

From puberty and relationships to consent and self-expression, our sexual experiences are so varied that it’s no small feat for our education to accommodate them all.

Here are 12 of my favourite books, tv shows and podcasts that thoughtfully consider the ethics around sex:

Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again by Katherine Angel

A critically-acclaimed analysis of female desire, consent and sexuality, spanning science, popular culture, pornography and literature.

The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan

A whip-smart contemporary philosophical exploration of how morality intersects with sex, particularly whether any of us can have a moral obligation to assist anothers’ sexual fulfilment.

I May Destroy You

British dark comedy-drama television series tracing the impact of sexual assault on memory, self-understanding, and relationships, and especially other sexual desires and expectations.

Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee

Multi award winning novel tracing misogyny, consent, power and indifference as they play out in one professor’s own actions and family in divided South Africa.

Love and Virtue by Diana Reid

Reid’s debut novel explores Australian college life and accompanying issues of consent, class, feminism and institutional privilege.

Sex Education

British comedy-drama series entering on the experience of adolescent sex education, thoughtful and nuanced around issues of consent, puberty, betrayal, love.

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

A memoir and series of ethical reflections weaving personal and detailed sexual experience together with gender and the family unit.

Masters of Sex

American drama exploring the research and relationship of William Masters and Virginia Johnson Masters and their pioneering scientific work on human sexuality.

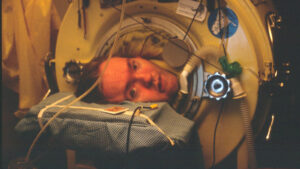

On Seeing a Sex Surrogate by Mark O’ Brien

Photo courtesy of Jessica Yu

A short personal memoir about disability and sexual expression, through the particular experience of seeing a sexual surrogate.

Fleabag

British television series exploring sex, infidelity, ageism and how casual sexual identity joins up with the rest of a person’s identity.

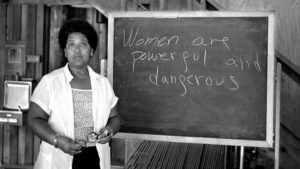

The Uses of the Erotic essay by Audre Lorde

A beautiful series of literary reflections on the power of the erotic, along with an exploration of why it is kept hidden, private, and denied, especially to particular groups.

Do the right thing from Little Bad Thing

From the podcast, Little Bad Thing about the things we wish we hadn’t done. This episode features a thoughtful conversation about the aftermath of assault, choices and healing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 12 JUL 2022

After a two-year hiatus, the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI), is returning live and unfiltered to Sydney from 17–18 September at Carriageworks.

Ahead of the eleventh festival’s program release, we sat down with Festival Director, Danielle Harvey to get a sneak peek into the 2022 program and what it takes to create Australia’s original disruptive festival.

Our world has so rapidly changed over the past few years. How do you determine what makes an idea truly dangerous in this climate?

The thing with dangerous ideas is that they react and change with what’s going on in the world. When we consider FODI programming we always look to talk about the ideas that perhaps we’re not addressing in the mainstream media enough. The quiet, wicked ideas, that will be snapping at our heels before we know it!

FODI is about creating a space for unconstrained enquiry — for both audiences and speakers, so we aim to find different ways of talking about things; a different perspective or angle — whether that comes from putting people from different backgrounds or disciplines together or encouraging speakers to push their idea as far as it could possibly go.

The 2022 program will explore an ‘All Consuming’ theme. How do you feel this reflects our world at the moment?

This year’s theme responds to and critiques an age consumed by environmental disaster, disease, war, identity, political games and 24/7 digital news cycle.

It considers the constant demands for our attention and our own personal habits formed to deal with an avalanche of information, opportunity, and distraction. In an all-consuming time where there is so much vying for our attention, what exactly should we give it to?

How do you ensure a balance of ideas when putting a program together?

Our team has such a range of diverse roles and practices that provide us access to a very complementary range of experts across the arts, academia, business and politics. Some of us have worked together for over a decade which has meant we’ve developed an enduring dialogue that facilitates building a program in an exciting and agile manner.

After 10 festivals, we also have a fabulous and engaged speaker alumni network who keep us informed of any interesting developments in their respective fields.

FODI has been dubbed as Australia’s original disruptive festival, what is it about disruption that makes it important to base a festival around?

Progress happens when we are bold enough to interrogate ideas — when we’re able to have uncomfortable conversations and be unafraid to question the status quo. Holding the space open for critique without censure is incredibly important. It’s your choice if you come, if you want to sit in the uncomfortable, if you want to be curious about the world around you.

This year the festival will be held at Carriageworks. How does the festival align with this choice of site?

FODI has been privileged to have been housed in so many iconic Sydney venues, from Sydney Opera House to Cockatoo Island and Sydney Town Hall. Carriageworks is now a new home for FODI, that has empowered us to be bolder and provides a fantastic canvass for creating a truly ‘All Consuming’ experience for audiences, speakers and artists.

How would you reflect on the festival’s journey over the past few years to where it is now?

Obviously coming out of COVID in the last couple of years we’ve had some time to reflect, and perhaps the 2020 theme ‘Dangerous Realities’ was a little too prophetic! During that time we were one of the first festivals to turn that program digital, which aired over one weekend. We ended up having 10,000 people tune in live and then another 15,000 and a few days after it. I don’t think I’ve really seen any other festival that moved online and get those sorts of numbers that quickly. It’s a real credit to the FODI team and audiences.

Then in 2021 we embarked on a special audio project, ‘The In-Between’ which saw us pair unlikely people together to have a conversation about what this moment — pandemic, global power shifts, social shifts — might mean. That more open questioning was really enlightening, with some feeling afraid — like it is the end of an era. While others were more hopeful or unconvinced that it is anything new at all.

We’ve also been mining many of our FODI archival talks and released them as podcast episodes, which now have over 165,000 listens globally. It’s been fantastic to be reminded of how eerily relevant so many of these ideas were and how often we should look to the past in order to look forward.

As a result of our great digital programming and on demand content, we’ve now got this huge extended audience now and it’s been a joy to engage with people who weren’t physically able to join us previously.

What’s the most dangerous idea out there for you right now?

For the past two years we’ve been told that being with other humans is one of the most dangerous things you can do! So, I’m excited to see us come together, in person, this year and connect in a festival setting.

And finally, what are you most excited to see at FODI this year — what do you think sets this year’s program apart from others?

2022 heralds a return to public gatherings. We’re thrilled to support the arts and a return to live events and cultural activity after a very challenging time for so many in NSW and nationally.

I’m excited by bringing so many international speakers to Sydney, to hear some deep global analysis and different voices. The experiential elements we are planning will also provide another fabulous reason to get out of the house and back into our unique festival setting.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns 17–18 September 2022. Program announcement and tickets on sale in July. Sign up to festivalofdangerousideas.com for latest updates.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Enough with the ancients: it's time to listen to young people

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Daniel Finlay Anna Goodman 6 JUL 2022

Nearly 20% of Australia’s population is between the ages of 10 and 24, yet their social and political voices are almost unheard. In our effort to amplify these voices, The Ethics Centre will be hosting a series of workshops where young people can help us better understand the challenges they face and the best ways for us to help. We’re listening.

You’re sitting at the dinner table at a big family gathering. Conversation starts to die down and suddenly your uncle says: “Have you seen that Greta girl on the news? I understand that climate change is a big deal, but the kids these days are so angry and loud. They’d get more done if they showed some respect.”

Many people under 25 have been in this position and had to make a choice about how to respond. This decision is often more difficult than it seems because there doesn’t seem to be a preferable option. Philosopher and feminist theorist Marilyn Frye gave a name to this kind of situation: a double-bind. In her essay Oppression, she defines the double-bind as a “situation in which options are reduced to a very few and all of them expose one to penalty, censure, or deprivation.”

Frye originally used the double-bind to talk about how women often found themselves in situations where they were going to be criticised equally for engaging with or ignoring gender stereotypes. The double-bind can be used to explain the difficult positions that anyone who experiences a negative stereotype finds themselves in and provides insight into why people with important perspectives often feel the need to censor themselves.

Let’s say we do choose to speak up. We can justify our anger. There are so many huge issues that impact the world – climate change, the pandemic, rampant inequality, and so on – and it feels like things are changing far too slowly.

Young people especially should be allowed to be angry, because this is the world we will inherit.

Unfortunately, it’s a common experience for younger generations to feel that their voices aren’t listened to or respected. Even though these reasons should more than justify the anger and frustration of young people, emotion can often (unjustly) obfuscate the reality of what we say.

So, let’s try the other way. We choose to not engage and instead let the comment slide. However, then we’re at risk of being seen as the “apathetic teen,” a narrative that has been perpetuated ad nauseam claiming that young people don’t really care about anything (which we know isn’t true).

Young people care about a lot, and have a lot to care about. Not only do they care, they act. A recent survey of 7,000 young people found that two-thirds of respondents seek out ways to get involved in issues they care about, and 64% believe that it is their personal responsibility to get involved in important issues. So, it’s not always easy to just let your uncle’s tone-policing go when you feel passionate about a topic, especially when staying silent can be as damaging as speaking up.

Here we see the double-bind in action: neither of the most obvious responses to the situation are favourable or even preferable. Because of a build-up of social and cultural assumptions and expectations, we’re often placed in a position where we seem to lose in some way no matter what we decide to do.

The Australian youth experience

Unfortunately, age discrimination towards young people doesn’t end at the dinner table. A 2022 survey conducted by Greens Senator Jordon Steele-John found that “overwhelmingly, young people are feeling ignored and overlooked”. Gen Z (people born between 1995 and 2010) are more likely to be viewed as “entitled, coddled, inexperienced and lazy,” which is having negative effects on young people’s confidence in the workplace. It doesn’t help that young people are hugely underrepresented in the Australian government and positions of power in the private sector.

Young people should not have to convince everyone that their voices are worth listening to. The combination of endless global issues and lack of representation in positions of power, which is compounded by a culture that doesn’t give appropriate weight to their contributions, creates a climate that leaves young people feeling frustrated and disempowered.

So, what can we do? As with most social issues, there isn’t one simple fix to the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of youth because it stems from a few different things that are ingrained in our society and culture. We can question our assumptions and those of others by recognising that “youth” as a social or cultural category isn’t really coherent anymore. There has been an enormous rise in the number of subcultures that are increasingly interconnected thanks to mass media and the internet, meaning that “young people” are more diverse than ever before.

Most importantly, we can bring young people together and into spaces where their voices will be heard by people who are in a position to make change.

As part of our mission to do just that, The Ethics Centre is developing a growing number of youth initiatives, like the Youth Advisory Council and the Young Writer’s Competition.

Through these initiatives, we are starting an ongoing conversation with young people about the areas in their lives and futures that they think ethics is needed the most.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

(Roe)ing backwards: A seismic shift in women's rights

(Roe)ing backwards: A seismic shift in women’s rights

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Mehhma Malhi 4 JUL 2022

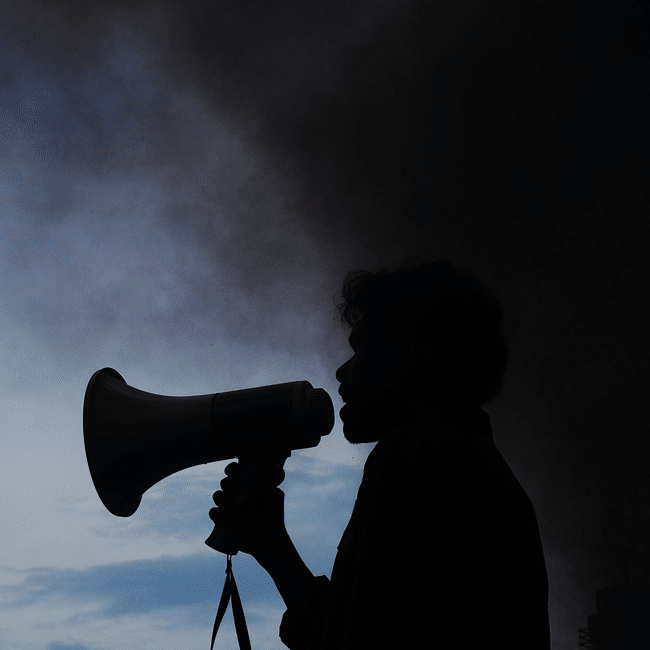

Standing in the middle of Washington Square Park in downtown Manhattan, on the 24th of June, I propelled a sign skyward that read: Abortion Is Healthcare. There were thousands of other slogans, on posters and placards, all being hoisted repeatedly by protesters equally aggrieved by the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

Earlier that same day, at 10 AM, the United States Supreme Court had overturned the ruling of the original monumental case. Since 1973, Roe v. Wade had protected the constitutional right to privacy for nearly half a century – ensuring that every woman in the US could obtain an abortion without fear of criminal penalty. But the repeal of this landmark case has unfortunately handed the regulation of abortion back to each individual state. And now, approximately 20 US states are set to once again criminalise or entirely outlaw access to abortions, despite two-thirds of its citizens being in favour of abortion.

So how will this loss of privacy constrain women’s autonomy?

The right to an abortion protects women from bodily harm, insecure financial circumstances, and emotional grief. The medical procedure allows a woman to maintain bodily autonomy by affording the choice to decide when, or if, she ever wants a child. Abortion acknowledges a woman’s right to live life as she intends. Banning abortion severely compromises that choice. Further, it does not reduce abortion rates but instead forces women to seek abortion elsewhere or by unsafe means. In 2020, over 900 000 legal abortions were conducted in the United States by professionals or by mothers using medication prescribed by physicians.

Banning abortion places a hefty burden on women, suppressing their autonomy.

The Legal Disparity Pre-Roe

Before Roe, women in the United States had minimal access to legal abortions, which were usually only available to high-income families. Illegal abortions were unsafe and in 1930 were the cause of nearly 20% of maternal deaths. This is because many of them relied on self-induced abortions or asked community members for assistance. Given the lack of medical experience, botched procedures and infections were rife.

Pre-Roe abortion bans harmed and further disadvantaged predominantly low-income women and women of colour. In 1970 some states allowed abortion. However, given the lack of national support, women were expected to travel long distances for many hours, which placed their health at significant risk. Once again, this limited access created unequal outcomes by only providing access to select women with means to travel and financial security.

Post-Roe Injustice

Post-Roe, the outcomes appear just as grim. In a digital landscape, technology brings benefits but also comes at a cost, introducing new vulnerabilities and concerns for women. While technology equips women seeking abortion to find clinics, book appointments, and help with travel interstate, it can also amplify the persecution of women when abortion is criminalised. For example, in 2017, Mississippi prosecutors used a woman’s internet search history to prove that she had looked up where to find abortion pills before she lost her foetus. And currently, since the recent ruling, clinics are scrambling to encrypt their data, while others are resorting to using paper to protect their patients’ sensitive information from being tracked or leaked

Unfortunately, there are also concerns that data could be used from period tracking apps and location services to further restrict women from accessing abortions. In previous years, prosecutors and law enforcement have wrongfully convicted women for illegal abortions by searching their online history and text messages with friends. Now that abortion is criminalised in some states, there are worries of increased access to private information that could be used against women in court: specifically the use of third-party apps that sell information which would further isolate women and reduce their ability to receive competent care, which in some states could be accessed without their consent.

The United States Department of Health and Human Services, known as HHS, released a statement on June 29th about protecting patient privacy for reproductive health. It states that “disclosures to law enforcement officials, are permitted only in narrow circumstances” and that in most cases, the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), commonly known as a privacy Act, “does not protect the privacy or security of individuals’ health information” when stored on phones. The guidance continues by suggesting how women can best protect their online information. For women to defend themselves, they must take extra precautions such as using privacy browsers, turning off locations, and using different emails.

These additional measures are troubling as they stipulate how women receive care. Placing the onus on women, the risk of information leaking limits access to resources and further restricts the privacy and autonomy of pregnant women as it creates fear of constant surveillance.

Further, it places people seeking care at a significant disadvantage if they do not know what information is protected and what is not.

Post-Roe, the medical landscape will also begin to shift. Abortion care is not uncommon in other procedures conducted by obstetricians and gynaecologists (OB-GYNs). Abortion care can overlap with miscarriage aftercare and ectopic pregnancies, creating murky circumstances for physicians and delaying care for patients as they wait for legal advice and opinion. In other cases, abortion care is necessary when pregnant women have cancer and need to terminate the pregnancy to continue with chemotherapy.

By restricting abortions, many physicians will be unable to provide adequate care and fulfil their duty to patients as they will be restricted by governing laws which will hinder further practice if persecuted. Any delay in receiving an abortion is an act of maleficence, as the windows to receive abortions grow increasingly slim and the restrictions grow tighter, the process inhibits providers from treating women seeking an abortion which obstructs beneficent care. As a result, many women will lose their lives from preventable and treatable causes.

Criminalising abortion will warp access and create unnavigable procedural labyrinths that will change the digital and medical landscape. Post-Roe United States will continue to breed fear and control over women’s lives. Criminalising abortion will isolate women from their communities and obstruct them from receiving competent medical care and treatment. Banning abortions will place an undue burden on women and will unfairly jeopardise their health and right to access care.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights