Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

Partway through the New Yorker’s profile of leading philosopher David Benatar, there is an anecdote that sums up his ethical position neatly.

A colleague at Benatar’s university announces to the department that she is pregnant. Benatar is pushed by the colleague as to whether he is happy about the news. Benatar thinks, then replies: “I am happy,” he says. “For you.”

Benatar is a leading advocate for the philosophical school known as anti-natalism. For such thinkers, being born is a harm. As it is so cleanly put in the title of his best-known work, Benatar believes that for each of us, it would have been better for us to never have been – non-existence is preferable to existence. Benatar might be happy for his colleague, but he is not happy for the conceived child who now faces a future of pain, distress and fear.

For such a seemingly pessimistic outlook, Benatar’s arguments in favour of anti-natalism are shockingly elegant. Take, for instance, his foundational view: the asymmetry of pleasure and pain. According to Benatar, pain is bad; pleasure is good. An absence of pain is good. But an absence of pleasure is not bad for the person for whom that absence is not a deprivation.

Imagine, for instance, that one day, on a morning stroll, you encounter a branching path. You take the left road. A few metres ahead, you spot a $100 bill lying on the ground. This brings you a deep pleasure. But now let’s say that you never took the left road – that you instead veered right. In this possible world, you do not encounter the $100 bill. If you had taken the left path, you would have. But you don’t know that. You have not been promised any money; you are not aware of what you have lost. Thus, Benatar thinks, you have not been harmed.

This is the key to the anti-natalist position. The child who is never born does not know that they are missing out on the pleasures of life; there is no entity who has been deprived, because there is no entity that exists. Moreover, the child who is born might encounter these pleasures, but they will also encounter a great number of pains. For Benatar, life is a myriad of tiny, complicated discomforts, from being hungry to needing the bathroom. Not bringing a child into the world means avoiding the perpetuation of suffering, saving an entity from a long, painful life for which the only escape – suicide, death, illness – is more pain.

These views may sound, for some, deeply psychologically distressing, and Benatar acknowledges that these are not easy pills to swallow. But he believes that they are necessary truths; that they are, in a sense, inevitable conclusions to be drawn from the nature of being a conscious entity in the world.

“I think that there is something hopeless and psychologically distressing about the nature of sentient life that makes anti-natalism the correct position to hold,” he explains.

Benatar’s position has been criticised by a number of thinkers, most recently by the stoic philosopher Massimo Pigliucci, who argued against the asymmetry of pleasure and pain in a recent blog post. According to Pigliucci, pain need not be morally bad; pleasure need not be morally good. For the stoic, these are “indifferents”, their moral value neutral.

But Benatar believes that Pigliuicci has misattributed claims to him. “The asymmetry I describe is not itself a moral claim – even though it supports moral claims about the ethics of procreation,” he explains. “My claims about pain and pleasure are claims about their prudential value for the person whose pain and pleasure they are – or would be.”

“Anybody – and I am not suggesting that Professor Pigliucci is among them – who denies that pain is intrinsically bad for the person whose pain it is, and that pleasure is intrinsically good for the person whose pleasure it is, does not understand what pain and pleasure are, and how and why they arose evolutionarily. If pain does not feel bad, it is not pain. If pleasure does not feel good, it is not pleasure.”

Others still have compared Benatar’s positions to those held by ecofascists, thinkers who believe that humanity is a virus that is wreaking a havoc on the natural world, and that the only way to avoid this suffering is to force the extinction of the human race. Indeed, there is at least some overlap between ecofascist beliefs and anti-natalist ones – both argue in favour of the end of human life – but Benatar is untroubled by such a connection, for the same reason that “those of us opposed to smoking should not be troubled that the Nazis were also opposed to smoking.”

“Even though (some) anti-natalists think that humans are bad for the environment, this shows only that they agree with the ‘eco’ part of ‘ecofascism’,” Benatar explains. “Anti-natalists are not committed to the ‘fascism’ part – and should, I argue, be opposed to it.”

Benatar’s position might seem deeply cynical, even nihilistic, but there is a strange kind of hope in it too. “Part of the reason why some people may find anti-natalism unthinkable is that they cannot correctly imagine what a world without sentient life would be like,” he explains. For the anti-natalist, there is some comfort to be taken in this potential, consciousness-free world – a world without suffering, without pain, without suicide or famine or death. After all, what, paradoxically, is more optimistic than that?

David Benatar presents The Case for Not Having Children at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

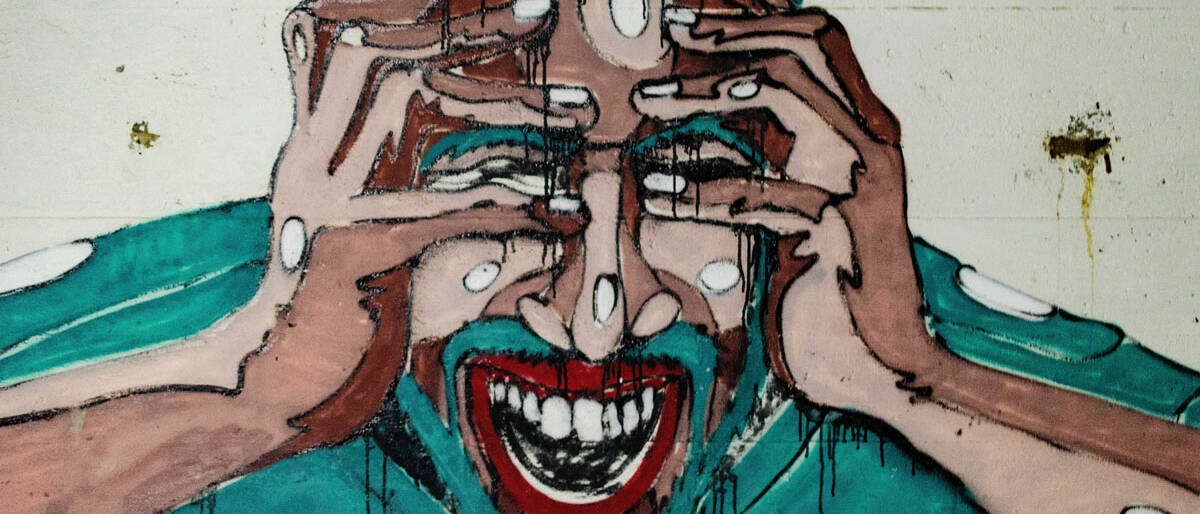

Image by Aarón Blanco Tejedor

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

The case for reskilling your employees

The case for reskilling your employees

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance 5 NOV 2021

Futureproofing the workforce doesn’t just make good business sense, it simply makes sense, writes Paul Rodger.

Like it or not, we’re in the middle of a skills revolution. The effects of digital transformation, environmental change and economic uncertainty have disrupted conventional career pathways, causing businesses to question what skills the workforce needs now and tomorrow.

According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report, as many as 75 million jobs are expected to be displaced by 2022 in 20 major economies. The good news: the report predicts a net increase in jobs by next year – driven by a demand for new capabilities. The bad news: 54 per cent of all employees will need to reskill or upskill in order to meet the demand.

If the global pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that companies are capable of making decisions that can have a good social outcome, even if their motive is ultimately self-interest. Sometimes, doing the right thing just makes business sense.

“Most businesses are actually ethical in nature because to be otherwise is high risk,” says behavioural scientist Dr Attracta Lagan. “Businesses put systems and processes in place to maintain ethical standards, because it’s counter-productive for them not to do so.”

For James Mcilvena, Managing Director of Lee Hecht Harrison (LHH) South APAC, an employment advisory firm specialising in organisational transformation, the question of who should reskill workforces is a no-brainer. “Leaving aside for a moment the kudos that come with doing the right thing, it makes financial good sense for organisations to upskill and reskill their people,” he says.

Aside from keeping institutional knowledge within a business, there is the simple benefit that upskilling and reskilling workers can be done for significantly lower cost than undergoing a restructure, paying out redundancies, and then hiring new staff and onboarding them. Workers need to be considered renewable, not replaceable, Mcilvena says. “Treating people as single-use, like you would a plastic kitchen set, doesn’t make sense from a corporate social responsibility perspective,” he adds.

“Treating people as single-use, like you would a plastic kitchen set, doesn’t make sense from a corporate social responsibility perspective.”

– James Mcilvena, LHH South APAC

Employees who have worked for an organisation for several years have a knowledge of that organisation’s needs, protocols and partner relationships that can’t easily be replicated. An organisation with a flexible and committed workforce is also one that can readily adapt to new shifting business paradigms.

Retaining staff by equipping them with the means to take on new skills has the added advantage of helping a business attract new talent. Staff members who experience the benefits of ongoing career development will usually share their positive experiences with others. Instilling a culture of professional growth can thus help strengthen an organisation’s reputation and bring in new candidates who value reskilling and upskilling opportunities.

“Boards should be kicking arse if management isn’t looking at these aspects of their workforce management,” says Mcilvena.

The need for businesses to stay on the front foot is a view shared by Adecco Group ANZ CEO Preeti Bajaj, who states that organisations’ ability to adapt to digital transformation depends on their levels of maturity.

“We at Adecco work with a spectrum of companies from proactive companies through to those who react in the moment,” she says. “Those that have greater maturity in understanding the reskilling/upskilling challenge have already made the case for workplace change – they have made the case to us and they also drive it internally themselves.”

“[Companies] that have greater maturity in understanding the reskilling/upskilling challenge have already made the case for workplace change.”

– Preeti Bajaj, Adecco Group ANZ CEO

Bajaj strikes a positive note for businesses that have been able to reimagine capitalism and place good outcomes for workers alongside earning a profit. She puts forward the example of Unilever as a company that has successfully reshaped its business around sustainability and practices designed to encourage and retain staff.

“The important point to make is that digital disruption is driving the structural shifts that are forcing organisations back to the drawing board. We’re seeing organisations reshape their business models and using that as an opportunity to incorporate sustainable workplace practices into those business models,” says Bajaj.

Change for the good

When considering the role organisations have to play in safeguarding the employability of their staff we must take into account the interdependent relationship that exists between business and society. “Work is such a major institution that it isn’t right to separate the world of work from the rest of society,” says Dr Lagan. “Big companies around the world recognise that they have an ethical responsibility to ensure that their employees remain employable – if not with them directly, then with someone else.”

Barriers to change exist, as is often the case when there is a need to recalibrate long-held assumptions. Companies must start to consider staff reskilling programs as an investment rather than an expense on a P&L sheet. They must have confidence in their workforce analytics so they can understand what skills they need of their staff – and generate a roadmap so they can equip them with those skills. Governments, too, have a role to play in incentivising businesses, but they need to think beyond short-term election cycles.

On the flipside, there is agreement on how organisations can more readily adapt to change, such as recognising the need for reskilling and upskilling considerations to move outside of HR departments and have them form part of a wider organisational strategy – complete with input by boards and senior management.

“These days organisations need to be learning organisations – everyone needs to have the opportunity to reskill themselves in tune with changes in the marketplace,” says Dr Lagan. “Remember that the technological shifts we’re seeing at the moment can be both an enabler and a threat to employability,” she says. “At the end of the day, to apply an ethical business lens is to make a choice – and the best choice a business can make is one that impacts positively on their employees and wider society.”

“The technological shifts we’re seeing at the moment can be both an enabler and a threat to employability.”

– Dr Attracta Lagan, Co-Principal at Managing Values

Why you should prioritise retaining – not replacing – your employees

• Businesses have a responsibility to ensure their employees remain employable.

• They’re well-placed to understand what skills are needed in future.

• Failure to keep staff acts as a burden to governments, family support networks and an underfunded mental health system.

• Employees are inspired to work for an organisation with social purpose.

• The market will reward businesses whose reskilling programs allow them to remain competitive.

• A culture of upskilling allows for adoption of new technological solutions and innovative business practices.

• Providing personalised career pathways for staff is appealing to the next generation of talent.

62% think businesses have a duty of care to reskill workers whose roles will be made redundant by automation.

– The Ethics Alliance Business Pulse survey

Reflection from Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre

Economies are on the brink of changes that will be at least as profound as the Industrial Revolution in their impact on individuals and whole societies. Technological innovation has the capacity to reshape the world of work, finally relieving humans of the drudgery, exposure to danger and the back-breaking labour that has characterised the work of many, for millennia.

However, the promise of a ‘golden age’ casts a long shadow for those who might be displaced by the automated systems and robots that will usher in almost unimaginable prosperity. Indeed, if any force will slow the process of innovation, it will be the political weight of people who fear (rather than embrace) the future.

It follows that every business (and society as a whole) has a vested interest in ensuring that change is carefully managed in a just and orderly manner.

This article was published as part of Matrix Magazine, an initiative of The Ethics Alliance.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we can’t learn from our past (and shouldn’t try to)

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

COP26: The choice of our lives

COP26: The choice of our lives

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 OCT 2021

There is such a thing as truth. It might be difficult to discern.

Aspects of the truth might vary depending on one’s perspective. However, there are some things that can be known with a certainty sufficient to guide practical action. One of those truths is that life is fragile. The more complex its form, the greater its vulnerability. In the web of life, the severing of one strand can lead the whole to unravel. Cataclysmic failure is not inevitable. It’s just possible – and that is worth knowing. Those who gamble with life take a mighty risk.

In ethics – facts matter. They really matter. Too often, they are ignored by those who think that good intentions are enough. By themselves, good intentions are not enough.

These and other matters are worth bearing in mind as a selection of the world’s leaders gather in Glasgow for COP26. The overwhelming consensus of the world’s leading climate scientists is that life-as-we-know-it is imperiled by the cumulative effects of greenhouse gases. We, humans, are the major source of those emissions. We are the most powerful force on this planet. Our choices shape and make the world what it is.

Ethics is about how these choices are made. It identifies and examines the drivers of choice and ultimately helps us to discern what is good or bad, right or wrong, in the choices we make. At its most fundamental level, ethics underpins the world we make.

So, in every respect, what happens in Glasgow is a matter of ethics.

It is also a matter of politics – and this is where the divorce between ‘ethics’ and ‘politics’ is a cause for concern. The division was never intended to be as great as it has become. For Aristotle, ‘ethics’ and ‘politics’ were intended to be two sides of the same coin. Ethics was concerned with questions about the good life for an individual. Politics was also concerned about questions to do with the good life – but as applied to the community as a whole.

In the lead up to COP26 in Glasgow, we have witnessed a very partial kind of politics that has no apparent concern for the national interest. Instead, the debate about climate change has been recast as a contest between country and city.

In prosecuting their case, the National Party has sought to remain part of the national government while simultaneously trashing the most basic obligation of governments: that they govern for the sake of all.

I should make it clear that when it comes to climate policy, the Ethics Centre has been one of the earliest and most steadfast advocates for a just and orderly transition to a more sustainable future – for everyone affected, not just those living under the National Party’s wing.

The attempt to weaken Australia’s position in Glasgow hinges on a couple of arguments. First, the claim is made that anything Australia does to reduce its contribution to global warming will be ‘futile’ – as our national impact is tiny in comparison to major polluters such as China and India. Second, it is argued that the cost to the economy is just too great to bear – especially for those working in ‘climate exposed’ industries. The National Party then adds to this critique by stating that people living in the cities are asking their country cousins to carry a disproportionate share of the burden.

History reveals what is wrong with such arguments. For example, consider the decision, by a Labor Government, unilaterally to slash tariffs and embark upon an ambitious program to promote free trade. The decision to do so was grounded in a commitment to the national interest and the reasonable belief that, in the long term, the benefits would outweigh the costs – and be shared by all. Back then (as now), Australia represented only around 3% of global trade. In that sense, slashing Australian tariffs could have been presented as a ‘futile gesture’. After all, why cut tariffs in advance of the world’s major economies? And that argument was made by those who opposed trade liberalisation at the time – the Coalition parties.

So, who are the major beneficiaries of free trade? It is the people whom the National Party claims to represent; those working in agriculture, mining and minerals. Who paid the price? Hundreds of thousands of people who lost their jobs in manufacturing – mostly in industries like textiles, clothing, footwear, automotive, etc. And where did most of these people live? In metropolitan areas. So it has been ever since. Australia’s free trade deals inevitably aim to maximise the incomes of people living in rural and regional Australia while leaving the price to be paid by people living in the cities.

Have we heard anyone from the National Party offering sympathy for those who have paid such a high price for regional prosperity? Not a word. Indeed, not a word from anyone. Why the silence? Well, you could put it down to political indifference. Or, it could be that there is now a broad consensus that despite the pain of transition (which typically has been disorderly and unjust), the national interest has been served.

Which brings us back to Glasgow.

Nearly everyone – other than the Federal Government – seems to agree that, for Australia, Glasgow presents a golden opportunity. The adoption of strong, binding targets could enable Australia to become one of the most prosperous nations the world has ever known. We have access to unlimited renewable energy, vast natural resources, a stable socio-economic environment, educated people and so on. We have everything needed to prosper. Indeed, just as it was in Australia’s national interest unilaterally to cut tariffs and embrace free trade, so it is in our national interest to embrace ambitious climate targets – not just for 2050 but by 2030. The stronger the drivers, the better the longer-term outcome.

Yet, even as I write these words, I wonder if this is to miss the point?

As noted above, Aristotle thought ‘ethics’ and ‘politics’ should concern themselves with questions about the ‘good life’. But for whom? For people in the bush? For Australians? For humanity? Or is our duty to ‘life’ itself? Is not the truth about global warming’s threat to life on this planet the ultimate ethical foundation upon which to build strong commitments in Glasgow?

When it comes to life on this planet, there is no ‘town’ and ‘country’, no ‘Coalition and ‘Labor’, no ‘Us’ and ‘Them’. We are all in this together.

I realise that politics is the ‘art of the possible’ – and that the average politician is acutely sensitive to the sentiments of their electorate. However, there are times when, at their best, politicians enlarge our possibilities and in doing so, lead their electorate to a better place. This is why politics used to be considered the most noble calling of a citizen.

Our Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has been wrestling with a form of politics that falls well short of that ideal. It is open to him to choose something better. That is both the gift (and curse) of his humanity. In Glasgow we will see not only what kind of politician Scott Morrison can be on our behalf. We will also get the measure of his capacity to lead. But most importantly, he will reveal the character of his humanity.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: The Panopticon

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Power and the social network

In science, power has a very precise definition. It is the rate at which energy is being transferred – a relationship that is captured in a formula and can be thought of more informally as the amount of “work” being done.

So, in a scientific context – specifically physics, the meaning of power is clear. In contrast, power is a far more complex concept in social sciences – as revealed within a diverse range of human interactions.

There are two prevailing views on the nature of power. The first regards power predominantly as a tool for subjugation, while the second acknowledges its potential for harmful use while also pointing to its potential role in maintaining balance.

Thomas Hobbes championed the first notion, conceptualising one man’s gain in power as another man’s loss. A straightforward illustration of this can be seen in a wrestling match where two people compete, with one eventually winning. That outcome is incompatible with both having equal power. Even if they do so initially, a relative increase in power eventually accrues to the victor.

The second perspective on power is provided by Michel Foucault, who considered its nature to be more subtle and varied. He proposed that power assumes many forms and is invested in many things. This latent power only arises when an individual engages in conversation around ‘regimes of truth’ or understanding. Foucault’s definition of power is thus more charitable. He thinks of power as an entity that resides in all things rather than a structure through which people/things can mobilise control. He notes that power is synonymous with knowledge and fact.

In older structures, such as government and politics, it’s challenging for an individual to lose power entirely. A benefit of having power is that can enhance the credibility and longevity of a person’s philosophy. Even though someone may lose their position and ability to make decisions in government, they often retain their power to exercise influence within their social circles provided their personal credibility remains intact. This is how ‘informal’ power (influence) can shape the exercise of formal power.

This permanence of power is an important determinant of the behaviour of those in power. Confidence in the enduring nature of power (and its ability to ward off adverse consequences) often leads the powerful to make choices that advance their personal interests.

Social media has begun to redefine the nature of power. The dominant platforms have gained tremendous traction over the past decade, and gradually personal identity has become synonymous with online presence. Widespread fame and the attainment of a quasi-celebrity status has given key ‘influencers’ the ability to exercise ‘informal’ (but none the less real) power through the vector of their online followers. But social media fame is even more fickle than that gained through traditional means as its basis is intrinsically unpredictable.

As such, social media provides some useful insights into the new dynamics of power within a technological setting. For example, in the case of social media, power is actually being exercised by those who offer a response to what ‘influencers’ post. When you use social media, you use and direct your power through likes and comments offered in response to what has been posted. However, if you disapprove of something you’ve observed, you can withhold your endorsement or even actively express your disdain through dislikes and critical comments – in other words actively withdrawing your support can be part of a conscious act to diminish the power. So, where does power lie? With the influencers or their potentially fickle followers?

The technology that underpins social media platforms has also ‘democratised’ power in that almost anyone can gain a following and thus have the potential to exert a degree of influence.

It’s much easier now to establish a position of power online than it was traditionally – because of ease of access and the fact that there is no limit to the number of people who can have a platform and broadcast their views widely.

But this increase in access to power is a double-edged sword because, as quick as it is for someone to gain power through today’s media, they can just as easily lose it.

As a result, many ‘celebrities’ have short-lived fame. The fleeting nature of power has extended beyond the realm of social media into the offline world. For example, the twenty-four-hour media cycle and the need to feed an insatiable media ‘beast’ means that politicians now operate under an intense and unceasing public gaze. Even the slightest whiff of scandal can end a career – and end access to a formal source of power.

In modern societies, scrutiny drives and confers power by facilitating influence.

Online power is probably best conceptualised as a mixture of Foucault’s and Hobbes’ descriptions of power.

Overall, we see how our old structures of power perhaps do not adapt easily to the online world. The reachability and balance of the internet make it easier to comment on those in power and hold them accountable for their actions. Ultimately, the dynamic is shifting; while the factors that give people power – influence, connection, and money – remain prevalent on the internet, the power they generate is no longer as enduring.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

WATCH

Relationships

Deontology

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 OCT 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we firmly believe ethics is a joint effort. It’s a conversation about how we should act, live, treat others and be treated in return.

That means we need a range of people participating in the conversation. That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Joshua Pearl as a Fellow. CFA-accredited, and with a Master of Science in Economics and Philosophy from the London School of Economics, Josh is currently a director at Pembroke Advisory. He also has extensive experience as a banking analyst, commercial advisor and political advisor – diverse perspectives that inform his writing.

To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

You have a background in finance, economics and government, and also completed a Master of Science in Economics and Philosophy – what attracted you to the field of philosophy?

I had always read a lot of political philosophy but when I first worked as a political advisor, it really dawned on me how little I actually knew. I figured what better way to learn more than by studying philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Tell us a little bit about your background in finance, and how that shapes your approach to philosophy.

My undergraduate degree was in economics and finance and my first job out of university was with an investment bank. Later on, I worked for an infrastructure development and investment firm. I’ve really enjoyed my professional experience, especially later in my career, though there were times early on when I questioned whether I was sufficiently contributing to society. And in truth, I probably wasn’t.

One way working in finance has helped the way I think about philosophy is that finance is practical. It’s a vocation. So when I think about philosophy I try to answer the “so what” questions. Why should we care about a certain issue? What are the practical implications?

In the context of finance, there are so many practical philosophical questions worth asking. What harm am I responsible for as an investor in a company that manufactures or owns poker machines? Should shareholders be advocating for corporate and regulatory change to help combat climate change? What are the implications of a misalignment between my investments and my personal values? And in the context of economics, philosophical questions are everywhere. What does a fair taxation system look like? How are markets equitable? Is it a problem that central bank policies increase social inequality?

These are super interesting issues (or at least I think so!) that have practical implications.

You mentioned you worked in government as a political advisor – what did you take out of that experience?

It was an amazing experience in so many ways. It was fantastic to work with really interesting people from a variety of backgrounds and have the opportunity to meet so many different members of the community, whom I wouldn’t normally have the opportunity to meet. I also felt very lucky to work for a woman whom I have a lot of respect for. Someone from a non-traditional background who has not only been very successful in her political career but has also contributed to society in a really positive way.

One of my biggest learnings from the experience was how important it is to try and consider issues from a range of multiple perspectives, with the hope of getting closer to some objective view. As part of this process, you realise the legitimate plurality of views that exist and the intellectual and moral uncertainty associated with your own views.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or thinker?

Thomas Nagel is a rockstar. He is in his eighties now and is still teaching at New York University. He is a really clear thinker whose writing is accessible and entertaining, and he isn’t afraid to challenge the orthodox views of society, including in areas such as science, religion and economics.

Nagel is a prolific writer who has undertaken philosophical inquiries across a range of fields such as taxation (the Myth of Ownership), evolution (Mind and Cosmos), and epistemology and ethics (The View from Nowhere). His most famous piece is probably What is it like to be a bat?, a journal article that is a must read for anyone interested in human consciousness.

If I could add a reasonably close second it would be Toby Ord. Ord is a young Australian whose work has already had huge real-world impacts in effective altruism (how can philanthropy be most effective) and the way society thinks about existential human risks. His recent book, The Precipice, was published in 2019 and analysed risks such as comet collisions with Earth, unaligned artificial intelligence and pandemics…

Covid restrictions have of course played havoc on the economy and our personal lives in the past 18 months – how have you been coping personally with lockdowns?

I arrived back in Australia on the very day mandatory hotel quarantine was introduced, so in some sense, everything since then has been a breeze! But to be honest, lockdown hasn’t affected me that much and I’m lucky to live with a really amazing partner. Over the course of lockdown, I’ve read a little more, written a little more, played tennis a little more… and spent way too much time trying to do cryptic crosswords.

Do you see any fundamental changes to our economic systems coming about as a result of the pandemic?

I don’t know that there will be fundamental changes, but I do hope there will be positive incremental changes. One is central bank policy. It seems inevitable that at some stage there will be a review of the RBA and with luck we follow the Kiwis’ lead and ask the RBA to consider how their policies inflate financial asset and house prices – the results of which add substantial risk to the financial system and increase social inequality. The second is what happens if (or perhaps when) Australia considers how to reduce the COVID fiscal debt. I am hopeful that we will consider land and inheritance taxes for reasons of fairness, rather than simply taxing people more for doing productive things like going to work.

As a consultant and Fellow of The Ethics Centre, what does a normal day look like for you?

My days are pretty structured, but the work is really variable.

My consulting focus is on issues at the intersection of finance, economics and government, such as sustainable and ethical business and investment. That might be working on an infrastructure project with an investment bank or government; undertaking a taxation system review for a not-for-profit; or working on ethical and sustainable investing frameworks and opportunities with various institutions, including with The Ethics Centre, which has been fantastic.

As a Fellow of The Ethics Centre, my primary involvement is through writing articles on public policy issues, with the aim of teasing out the relevant philosophical components. Questioning purpose, meaning and morality is part of being human. And it is also something we all do, all of the time. Yet there are very few forums to engage on these topics in a constructive and meaningful way. The Ethics Centre provides a forum to have these conversations and debates, and does so outside of any particular political, corporate or media lens. I think this is a huge contribution that really strengthens the Australian social fabric, so I feel really lucky to be involved with The Ethics Centre community.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

That certainly is the big one! I tend to think about ethics on both a personal and social basis.

On a personal basis, to me, ethics is about determining how best to live your life, informed by such things as your family’s values, social norms, logic and religion. Determining your “ideal life” so to speak. It is then about the decisions made in trying to achieve that ideal, failing to achieve that ideal, and then trying again.

On a social basis, to me, a large part of ethics is the fairness of our social institutions. Our political institutions, legal frameworks, economic systems and corporate structures, as examples. Pretty cool areas, I think.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Hindsight: James Hardie, 20 years on

Hindsight: James Hardie, 20 years on

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance 18 OCT 2021

Two decades ago the scandal surrounding James Hardie switched from the health havoc its products caused to the mishandling of victims’ compensation. In this rare interview with The Ethics Alliance’s Cris Parker, former James Hardie chair Meredith Hellicar reveals how stepping into the firing line left her stronger for the experience.

Corporate scandals can create chaos indiscriminately, far beyond the organisation involved. Lawyers descend, social media accounts are cancelled, computer access denied and journalists start blocking the driveway. Everyone gets hurt. For those who stand accused of transgression, pain is unavoidable. While they try to manage their own crisis, the lives of their families, friends and workmates are also thrown into turmoil.

Meredith Hellicar, former head of James Hardie, is well aware of how unforgiving the Australian public can be. But she still believes it was her duty to step in and help the company she served and the victims of a terrible consequence of its business.

“It has always been inappropriate to speak of the toll this saga took on the personal lives of the board and some executives because of the extent of the horror of dying from mesothelioma,” says Hellicar.

“However, the Hardie people were all humans, too.”

“It has been inappropriate to speak of the toll this saga took on the personal lives of the board and executives … However, the Hardie people were humans, too.”

It’s well documented that ongoing chronic stress can cause or exacerbate many serious health problems. Hellicar says it’s “no coincidence” that one director died of cancer, another had a cancer diagnosis, an investor relations executive suffered a brain aneurysm, an assistant in the office suffered a miscarriage and one of the communications team committed suicide in the two years after the James Hardie scandal became front page news. “But, in the eyes of the public, none of these people deserved anything but derision,” she says.

Lessons learned

Looking back, Hellicar believes there are many lessons – both practical and ethical – from her story for boards and directors in corporate Australia today. Not least that, in a world that demands more corporate governance, keeping up with 1000-page board reports is increasingly impossible. In 2007, the High Court of Australia found the James Hardie board breached its duties by approving the release of a potentially misleading statement to the stock exchange in 2001.

In a world that demands more corporate governance, keeping up with 1000-page board reports is increasingly impossible.

That statement said that the company – which had once dominated the asbestos industry in Australia – had fully funded the foundation responsible for paying compensation to people suffering asbestos-related diseases, such as mesothelioma. It was later found that there was an estimated shortfall in funding of about $1 billion. Justice Ian Gzell of the New South Wales Supreme Court was moved to issue a scathing judgement – and single out Hellicar as “an unsatisfactory witness”.

However, his ruling was controversial. The directors had argued they had not approved the media release. And after appeals in which directors claimed they had been punished enough by the adverse publicity and strong support from prominent Australians, their period of suspension was reduced from five years to two. Talk to many of Australia’s business leaders today and they are quick to voice admiration for Hellicar and respect for the way in which she behaved under fire.

Hellicar had taken the chair of James Hardie from Alan McGregor in August 2004 when his health deteriorated. Hellicar says she wasn’t forced to take on the position of chair, but chose to just before a Royal Commission delivered its report and only weeks before the AGM. As a seasoned director she was well aware this meant she was ultimately responsible for the behaviour of the organisation by being answerable to/accountable for any wrongdoing, regardless of whether or not she was personally culpable and merited condemnation. But she says she felt she was the right person to ensure ongoing support to the victims and reward the shareholders for staying with the company. Australia has the second-highest mesothelioma death rate in the world, with about 700 people dying from it each year. James Hardie’s victims ran a strong media campaign for compensation, fronted by Bernie Banton.

[Hellicar] was well aware … she was ultimately responsible for the behaviour of the organisation … regardless of whether or not she was personally culpable.

At the first opportunity, despite pushback from lawyers, Hellicar apologised to the asbestos victims that the compensation fund had proven to be underfunded. During a judicial inquiry, an investigation and civil action by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), three court cases and a redetermination of penalties over a total of nine years, the seven board members argued they had not approved the statement about compensation funding. Nonetheless, the directors were banned from serving as board members for two years and three months.

Hellicar’s illustrious career had included board positions on AMP, Amalgamated Holdings and the Southern Cross Airport Group. She had also held executive positions such as chief executive of Corrs Chambers Westgarth and managing director of TNT Logistics Asia.

The ban was a shock and the whole process left her “completely destroyed” and “totally reviled”.

Pitfalls for boards

Hellicar speaks of being raised by a father who was a used car salesman and often sacked because he was “obsessed with honesty”. She says honesty is a virtue she herself holds dear. While maintaining that she had tried to do the right thing for people harmed by James Hardie’s asbestos products, Hellicar has accepted the board fell short in its oversight of the executive team.

One of the contributing factors, she says, was “the failure of we directors to fulfil one of the core expectations of company directors; namely, to maintain high-quality peripheral vision and to ask just one more question of management, even in the face of seemingly adequate explanations first time”.

People expect boards to be across absolutely everything occurring in their organisations, but Hellicar says this is an impossible task.

Legal minefields include the assumption of knowledge. If a director has been included on a distribution list of a document, they will have been deemed to have read it, she says.

“Politicians and the media educate society to think that, if you’re the CEO or the board, you have to know everything,” she says. “The moment a CEO says, ‘I didn’t know’, the response comes back: ‘Oh, come on, how could you not know?’”

Before each board meeting, directors receive a board pack of between 200 and 1000 pages that they are expected to read. They may have up to a dozen scheduled meetings each year, extra committee and ad hoc sessions, and serve on several boards.

In an attempt to ensure no stone goes unturned and fully informed decisions are made, corporate governance rules have created an environment that makes it extremely difficult for directors to do their job at the standards expected.

Corporate governance rules have created an environment that makes it extremely difficult for directors to do their job at the standards expected.

Recently at a Governance Institute of Australia function, Philip Chronican, the chairman of National Australia Bank, said: “It’s not enough to turn up to a meeting, review a paper and check that it complies with all the rules and policies … Unless governance has a purpose to it, then it’s just box ticking.”

Hellicar also issued a warning about the tabling of documents at board meetings, “particularly when directors dial into meetings”, she says. “Our US directors on the phone back in 2001 were found by the court at first instance to have approved the release (of the financial state of the compensation fund) because they had not expressly abstained or dissented – even though the court agreed they had not seen it.”

Whether company boards are now ‘fit for purpose’ was the subject of a 2019 paper by Stephen Bainbridge, the William D. Warren Distinguished Professor of Law at UCLA School of Law. “Although directors spend more time on board activities today than they did 50 years ago, they are still ‘part-timers, the vast majority of whom have … employment elsewhere, which commands the bulk of their attention and provides the bulk of their pecuniary and psychic income,” he writes.

Bainbridge argues that directors spend too much time on regulatory and compliance matters, rather than oversight, and suffer a serious ‘information asymmetry’ compared with the full-time executive team.

“Directors … suffer a serious ‘information asymmetry’ compared with the full-time executive team.”

A different standard for women?

Hellicar acknowledges boards have to be held accountable – but she says too often people are demonised when something goes wrong, or a mistake is made. And she feels it is particularly toxic when public shaming leans heavily on questions of sexism.

Catherine Brenner, who was appointed to the board of AMP Life (a subsidiary of AMP), chaired by Hellicar in 2007, stepped down from her role as AMP Chair in 2018. This was in response to issues raised in the 2018 Hayne Royal Commission concerning the preparation of the Clayton Utz report on AMP’s fee for no service issue.

Brenner has been cleared of any personal wrongdoing. However, she was subjected to widespread public criticism regarding her qualifications and much was delivered through a gender lens, describing what she was wearing and questioning her role as a mother.

[Brenner] was subjected to widespread public criticism regarding her qualifications and much was delivered through a gender lens.

Although Brenner stated, “I would not want my experience to prevent others considering a future on listed boards, particularly women, as they bring a very different perspective to men and have much to offer corporate Australia,” the reality is female leadership has stalled.

As of February 2021, 32 per cent of ASX 200 boards are women, but only 10 females hold the CEO roles. Playing an active role in Chief Executive Women (CEW) and the 30% Club, a movement for gender balanced boards, Hellicar feels strongly about the quota merit debate.

“If you have to ask for quotas ‘or’ [make hiring decisions based on] merit then you’re assuming that somehow women are less meritorious than men. There is no evidence at all that women are less intelligent or qualified, none at all!”

Are women subject to more scrutiny and personal abuse when forced to step down from powerful positions? Hellicar says the fact that she was a female in charge intensified reactions.

“I find it ironic that so many of the insults thrown at Julia Gillard – which have, rightly, horrified people – were hurled at me without a word of reproof,” she says. “I received a series of serious death threats, which required security around my home. The media staked out our house from before dawn until after dark, making the trip to school each morning with our daughter both hazardous and stressful for us all.”

Hellicar’s reading of the situation is backed by research, including a study of financial advisors by Mark Egan and colleagues at the Harvard Business School in 2018. Looking at what happens when advisors make mistakes, the researchers found that female financial advisors are 20 per cent more likely to be fired for misconduct than men. They are also 30 per cent less likely to find another job in the industry.

A lack of forgiveness, combined with the vilification of those who knowingly or unwittingly transgress, means that people are under enormous pressure to cover up their errors. The punitive response discourages the sort of transparency that leaders require to deal with risk.

Hellicar says if she had a magic wand, she “would simultaneously inject everyone with this huge dose of kindness and a huge dose of ‘speak up when you see something that you think is wrong’”. She quotes her former James Hardie board colleague, Peter Willcox, who said: “Bad news isn’t like wine. It doesn’t get better with age.”

“Bad news isn’t like wine. It doesn’t get better with age.”

Make a mistake and rebound

Losing her career in the boardroom has had bittersweet consequences for Hellicar. Psychiatry had been a consideration in her university days and realising no ASX-listed company would risk appointing her to the board for fear of persecution, Hellicar reinvented herself by studying a Masters degree in Psychotherapy.

She is now an executive coach (as Australia and New Zealand executive chairman of Merryck & Co.), volunteers as a crisis counsellor with Lifeline once a week and is a mentor for public school students. Hellicar feels you can’t be successful in mentoring roles “unless you’ve got things in your life you’d wish you’d done better”.

Hellicar believes our penal system should be focused on rehabilitation rather than punishment but says that people often (not always) deserve a second chance. She has found strengths of reserve to emerge from the corporate shaming she experienced and is now an active contributor to the ethical education of business leaders and corporate women.

“I have a view that, surely, people are entitled to do something stupid – and they’ll be forgiven. But that’s not how the community thinks anymore. For some reason, we don’t believe people should be allowed to recover from their mistakes,” she says. But “we know people can learn from their mistakes”. The very fact that people have faced a traumatic public failure will sometimes leave them “richer for the experience”.

“Surely, people are entitled to do something stupid – and they’ll be forgiven.”

She adds: “In the US, the more scar tissue you have, the more sought-after you are. Not in Australia.”

“Surely, people are entitled to do something stupid – and they’ll be forgiven.”

The Ethical Lens

Cris Parker

Head of The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Centre Nearly two decades have passed since Meredith Hellicar’s experiences at James Hardie. What can we learn?

1. Respect for person is one of the primary principles in ethics and refers to the consideration and empathy that any human being deserves simply by virtue of being human. It calls on us to respect the intrinsic dignity of anyone. The way we behave towards other people is an expression of our own character and values and so treating people with respect is not motivated by whether they deserve it but rather because doing any less would diminish our own character.

2. Diversity is essential as boards look to navigate the increasing dynamic and complex issues organisations face today – not least to mitigate biases which can either silence voices, such as authority or status quo bias, or which can lead to individuals seeking out like-minded counterparts to corroborate their point of view, such as confirmation bias or group think.

3. Decisions in the board room require stakeholder trade-offs. An organisation possessing a strong ethical foundation developed through a well-defined purpose, values and principles will assist boards as they navigate competing interests and guide decision-making that is just and good.

4. A positive culture in the boardroom is built on transparency and accountability. This means an environment where directors can ask the hard questions, and where executive management are encouraged to share bad news without fear of persecution.

This article was published as part of Matrix Magazine, an initiative of The Ethics Alliance.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Hear no evil’ – how typical corporate communication leaves out the ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 14 OCT 2021

Businesses are having to address complex ethical questions about the extent to which a person’s vaccination status should be a condition of employment.

Here are some guidelines to consider:

1. There is a difference between a mandatory requirement (where there is no choice) and a condition of employment (which people can choose to meet as they think best).

Many jobs impose conditions of employment that relate to a person’s health status (including whether or not they have been vaccinated).

2. Respect and promote the maximum degree of freedom of employees – limited only by what is required to meet one’s obligations to others.

In determining this it’s important to consider:

- The nature of any duties owed to other people – including employees, customers, and members of the community more generally.

- The specific context within which people will come into contact with your employees e.g. frequency, proximity, location – and estimate the way these variables shape ‘the risk envelope’.

3. Determine if a legitimate authority (e.g. a government) has made any rules.

This includes Legislation, regulation, public health orders, etc. that determine how the business must act. For example, governments may set license conditions that ‘tie the hands’ of specific employers.

4. Actively seek alternative means by which employees might perform their roles, even if they are not vaccinated.

Note, alternatives must be practical and affordable.

5. Determine who bears the burden (including the cost) of alternative measures.

For example, should employees who choose not to be vaccinated be required to be masked, or to use rapid antigen testing at their expense?

6. Consider how roles might be reassigned amongst the unvaccinated.

With priority given to those with medical exemptions.

7. Treat every person with respect – ensuring that no person is ridiculed or marginalised because of their choice.

But note that respect for one person or group does not entail agreement with their position; nor does it void one’s obligations to others or your right, as an employer, to advance your own interests.

8. Be prepared to adjust your own position in response to changing circumstances.

Including evidence based on the latest medical research relating to vaccine safety and efficacy, etc.

Read more on the difference between compulsory and conditional requirements here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The case for reskilling your employees

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Recovery should be about removing vulnerability, not improving GDP

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Activist CEO’s. Is it any of your business?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

John Elkington on business sustainability and ethics

John Elkington on business sustainability and ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 11 OCT 2021

John Elkington is a world authority on corporate responsibility and sustainable development. Elkington sat down with The Ethics Centre’s Simon Longstaff to chat about the future of business sustainability.

“I first got involved in the business world in the mid-70s, at a time when business really didn’t want to talk to people who were self-described environmentalists or anything like that. And yet I was an environmentalist.”

John Elkington believes his admiration for the natural world began when he was six or seven. He found himself alone in the middle of a field in Northern Ireland at night, in complete darkness, and to his surprise he looked down and his feet were surrounded by tens of thousands of baby eels. “I put my hands down in the dark and had these things wriggling through my fingers. And I had one of these sort of absolute panic attacks followed by something really quite profound, which has never left me somehow,” he says. “It was a sense of connection.”

Audio: Listen to John Elkington talk about his childhood experiences.

John Elkington has dedicated his professional career to corporate responsibility and sustainable development. In the early 80s, he set up a company called Environmental Data Services, and within 18 months was helping major companies write their first environmental policy statements. His idea was: you can make or save money by doing the right thing on resources and environmental protection. “Even if you’re a small or medium size enterprise you can have a catalytic effect,” he says. “But by the time you get to the size of an Exxon Mobil or a BP or a Shell then you really are having major economic impacts.”

John Elkington on the corporate responsibility movement.

“I think for the last 40 years, business has been encouraged to be more responsible. More transparent and more accountable. The responsibility agenda continues to evolve and expand. And now we’ve got wealth divide on the agenda. We’ve got public access to health care issues. We’ve got tax evasion – more and more issues are coming in which companies are going to have to deal with.

“But the problem is that the whole corporate responsibility movement, of which I’ve been part for so long, has failed in the sense that the systems that we depend on are all wobbling. Our economies are coming apart at the seams – our governments, the political systems, are doing the same. Our societies are under challenge and the biosphere is wobbling in a way that we haven’t seen for a very long time. So corporate social responsibility, as much as I love it, isn’t working.

“Our generational task now is economic, social, environmental, political and cultural regeneration. And the problem is that our current political classes weren’t trained for it. They talk about recovery, but they mean how can we get back on the previous set of rails? And I think the debate now has to be very different.”

Audio: John Elkington talks about the path ahead for corporate responsibility.

Is John Elkington optimistic about the future?

“I think people are increasingly aware that the old order can’t hold, things are coming apart and that’s not going to stop just because we have a new American president. We put on a conference in London in 2020, called the Tomorrow’s Capitalism Forum, and the tagline was “step up or get out of the way”. Now, if you’re in coal that’s not an idea you’d like to embrace if that’s your business. But I think we have misread the urgency of the sort of cataclysmic system changes that are coming towards us. It’s like a tsunami. And it’s very difficult to ride a tsunami. I think we’re now faced with the consequences of what we and previous generations have been doing since the industrial revolution, at least. And we have a very, very short period of time in which to get our act together.”

“I think at the moment, business leaders and some finance leaders are proving more interesting than many political leaders. But this is a political challenge and the politicians have to wake up and get involved.”

Audio: hear John Elkington talk more about tackling climate change.

What keeps John Elkington awake at night?

“We need system change and cultural shifts, which the older generations are going to find profoundly dislocating. One of the things that worries me more than almost anything else is the intergenerational dynamics in all of this. In so many parts of the world you have very rapidly aging populations, and an aging population takes people increasingly to conservatism because they’re only investing for a shorter period of time. So I think there’s a real potential for anger to build up in younger populations. I’m surprised we haven’t seen more of it.”

“I’m 71 but oddly, I feel the next 15 years are going to be the most exciting of my life and the most challenging and the most dangerous politically.”

“We’re in a time of immense turbulence and people will suffer. There will be conflicts, tensions and stresses, which at times will be off the scale. But at the same time I think this is the most exciting period in our collective history, probably for hundreds of years. I’m very excited about the potential because I think it is when old systems come apart that the potential to drive systemic change goes off the scale. So the challenge for leadership I think is immense. And I think in many ways universities and business schools are not yet properly preparing people for that new world.”

John’s advice for future business leaders:

- Get out of your comfort zones and be exposed to different realities.

- Challenge your sense of who you are and what you should be doing.

- Question whether the systems you work in are still fit for purpose.

Audio: Listen to the podcast of John Elkington’s full discussion.

John Elkington is a world authority on corporate responsibility and sustainable development. He is currently Founding Partner and Executive Chairman of Volans, a future-focused business working at the intersection of the sustainability, entrepreneurship and innovation movements.

This episode was made possible with the support of the Australian Graduate School of Management, in the School of Business, at the University of New South Wales. Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast.

Get more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

WATCH

Business + Leadership

The thorny ethics of corporate sponsorships

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Holly Kramer on diversity in hiring

Holly Kramer on diversity in hiring

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 11 OCT 2021

Holly Kramer, Non-Executive Director on the Boards of Woolworths and Fonterra Group, and Pro Chancellor at Western Sydney University, sat down with the Ethics Centre’s Simon Longstaff to chat about the future of business sustainability.

Holly Kramer believes that responsible management has grown in significance exponentially over the last five to ten years. She suggests the old Milton Friedman view of shareholder primacy is a thing of the past, and shareholders are now holding businesses to account and demanding they do the right thing for society.

“There’s a spectrum of different approaches to business stewardship,” she says. “There are those people who don’t understand the way the world has shifted in its attitudes toward corporate responsibility at all. There are those who do understand and “do the right thing” because they know that’s what’s expected of them, and then there are those who do the right thing because it’s simply the right thing to do.”

In the past, business decisions were generally made through the lens of profitability, and the time frame was – at most – a three year view; whereas today, management and boards must take into account the impact of their decisions on multiple stakeholders over longer time horizons, which can sometimes make those decisions seem more challenging.

“Companies are trying to change their metrics of performance. In many companies I’m involved with, you’re measured on financial and non-financial measures; and there is consideration of not just what you’ve achieved but how you’ve gone about it. They’re sometimes called “softer” skills or metrics, but I don’t agree with that characterisation. Acting sustainably requires a broader skill set and tough decisions. A new generation of business leaders are coming through, and they believe it’s important for businesses to be sustainable on every dimension – including diverse and inclusive workplaces, climate friendly practices, meaningful community engagement and leading with purpose.”

“At the end of the day, it’s critical that you hire the right people, people who understand that the decisions they make have a broader impact than just the bottom line. That’s what’s going to make the biggest difference for your business in the long run.”

Audio: Listen to Holly Kramer chat about reconciling doing the right thing with remaining profitable.

Holly Kramer on her career challenges.

“When I was in the telecommunications industry, there was a lot of money to be made from complexity. There were multitudes of calling plans; customers usually struggled to figure out what was the right solution for them. Customers told us that they wanted simplicity. Yet every time we looked at how to make them more simple, we couldn’t make the business case stack up. And so there were often internal struggles within the organisation. We were told: ‘look, if you do this, it will be an NPV negative business case, so we just can’t do it’.

“And while we battled with one another internally, ultimately what happened was that the competitors got there first, gave customers what they wanted and we lost market share as a result. I’ve always believed that when, on first glance, the numbers may not stack up, ultimately either competitors or customers will have the final say.”

Holly Kramer on responding to consumers.

Holly Kramer got her start in marketing, and she leveraged that skill when she started running an affordable fashion brand, so she was well aware that for a business to be successful it must reflect changing consumer needs. “Our starting point was to try and understand our customers as well as we could. Lots of research, lots of personal interaction. We learned early on, for example, that the industry’s idealised version of clothing models – young, skinny, and not diverse – didn’t resonate at all with our customers. They wanted to see the clothes look good on people that looked like them. And to feel good about themselves without the industry defining beauty for them.”

The problem with fashion supply chains.

Simon: “The fashion industry is now having to deal with the question of supply chains. There’s the modern slavery legislation, there’s a consciousness about environmental, social, a range of different issues, but I’m particularly thinking at the moment in the fashion industry where people were selling things like a $1 t-shirt – I really don’t know how anyone can think it’s possible to produce something for so low a price without it having adverse effects for the labour standards in the countries where they’re produced. And I think you encountered some of this during the time you were in the industry?”

Holly: “I was in the fashion industry … when the Rana Plaza tragedy happened in Bangladesh, which focused a lot of the world’s attention on human rights and ethics in the supply chain. However, I was working for a business in Australia that was owned by a parent company in another country. They were from a disadvantaged part of the world that had different standards for what was acceptable practice. And I remember getting challenged about our sourcing decisions because they (the parent company) simply had different standards and priorities than we did. But we had to do what we thought was right and also be consistent with community standards in Australia, where it was important to ensure fair employment practices were maintained in the companies who supplied us.

“The other issue was that a lot of the companies, to mitigate their reputational risk, just pulled their business out of Bangladesh. The problem with that is that you put jobs at risk in countries where the employees are most vulnerable. We had to ensure that our business was commercially viable, but also that we were doing the right thing by the countries we were sourcing from. It’s important to remember that there are no simple solutions. Companies need to consider the outcomes from a number of different angles.”

Audio: Listen to Holly chat about grappling with the ethics of fashion supply chains.

On accounting for diversity.

Over her decades working in the business sector, Kramer has seen boardrooms grapple with the idea of diversity and representation. “Gender is just one proxy for diversity,” she says. “It’s a starting point and it’s easy to measure.”

Kramer believes true diversity lies in having an array of people contributing ideas and solutions and having an environment where different ideas are welcomed. “It’s definitely important, but I don’t necessarily see gender as the most important starting point for diversity. I find it is usually cognitive diversity. Introverts and extroverts. People who like data and people who use intuition. Risk takers and those who are more risk averse. She says she’s always looking for new people who think differently to her because it makes good business sense. Gender is important, and thankfully business has made a lot of progress in that space, but Kramer feels there needs to be ethnic diversity, socioeconomic diversity, as well as generational diversity, which is just as important to achieve.

Holly’s advice for emerging leaders:

- Doing the right thing is good business

- Approach challenges with a long-term lens

- Put yourself in the position of your customers

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast with Holly Kramer here>>

Holly Kramer is a Non-Executive Director on the Boards of Woolworths and Fonterra Group, and she is Pro Chancellor of Western Sydney University. Formerly, she was Deputy Chair of Australia Post and Chief Executive Officer of Best & Less. She has more than 25 years’ experience in general management, marketing and sales including roles at the Telstra, Pacific Brands and Ford Motor Company.

This episode was made possible with the support of the Australian Graduate School of Management, in the School of Business, at the University of New South Wales. Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast.

Get more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dark side of the Australian workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Does Australian politics need more than just female quotas?

Does Australian politics need more than just female quotas?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Joshua Pearl 8 OCT 2021

The Labor Party’s recent decision to parachute Kristina Kenneally into the ethnically diverse electorate of Fowler came at the expense of Tu Le, a female Australian lawyer of Vietnamese background.