What do we want from consent education?

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 11 MAY 2021

In mid-April this year a government-funded video was released which aimed to teach high-school aged Australians about sexual consent.

The video, which attempted to emphasise the importance of sexual consent by discussing the forced consumption of milkshakes, was widely criticised around the globe. It has since been removed from ‘The Good Society’ site, with secretary of the Department of Education Dr Michele Bruniges citing “community and stakeholder feedback” as reason for the action.

Widespread criticism of the video can be found online about the video’s sole use of metaphor to describe consent. Less present in the discussions is consensus on what a good consent education video would look like.

The underlying assumption in the video released by The Good Society is that issues of sexual consent can be managed by teaching adolescents that the rights of an individual are violated when an aggressor forces a ‘no’, or a ‘maybe’, into a ‘yes’. And, the video tells us, “that’s NOT GOOD!“.

Is it sufficient to tell adolescents to respect the rights of their peers in order to overcome issues of sexual violence? While rights may help us discuss what it is we want our societies to look like, they fail to assist us in getting others to care for, or value, the rights of others.

Sally Haslanger, Ford Professor of Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) argues that actions are shaped by culture, and that cultures are effectively networks of social meanings which work in a variety of ways to shape our social practices. To change undesirable social practices, cultural change must also occur.

For example, successfully managing traffic is not just achieved by passing traffic laws or telling drivers that breaking the law is ‘not good’. Instead, Haslanger tells us that it requires inculcating “public norms, meanings and skills in drivers”. That is, we need a particular type of culture for traffic laws to adequately do what it is we want them to do. Applying this idea to sexual consent, we see that we are required to educate populations about why violating the preferences of our peers is indeed ‘not good’, after all.

Skirting around the issue fails to provide resources to move our culture to better recognise the deep injustice and harms of sexual violence.

Vague, euphemistic videos will likely fail to play even a minor role in transforming our current culture into one with fewer instances of sexual violence. This is due largely to the fact that Australia is comprised of social and political systems which fail to take the violence experienced by women and girls seriously.

Haslanger suggests that interventions such as revised legislation and moral condemnation will be inadequate when enforced onto populations whose values are incompatible with the goals of such interventions.

Attempting to address issues of sexual misconduct indirectly – as seen by The Good Society video – are likely to be unsuccessful in creating long term behavioural change. Skirting around the issue fails to provide resources to move our culture to better recognise the deep injustice and harms of sexual violence.

As Haslanger tells us, so long as we are a culture which has misogyny embedded into it, social practices will continue to develop that cause people to act in misogynistic ways. We are required to reshape our culture in a way that changes the value and importance of women.

So long as we are a culture which has misogyny embedded into it, social practices will continue to develop that cause people to act in misogynistic ways.

So, what will shift and transform embedded cultural practices? A better approach advocates educating audiences why consent is valuable, not just how to go about getting it. A population which fails to value the bodily autonomy and preferences of each of its members equally is not a population that will go about acquiring consent in successful and desirable ways.

Quick fix solutions such as ambiguously worded videos on matters of consent are likely to do very little for adolescents in a school system absent of a comprehensive sexual education, and where conversations on sexual conduct and interpersonal relationships remain marginalised.

We need to aim to create a generation of adolescents who are taught why sexual consent is important and why they should value the preferences of their peers. A culture which continues to keep sex ‘taboo’ by failing to explicitly discuss sexual relationships and the reasons why disrespecting bodily autonomy is “NOT GOOD!” will be one which fails to resolve its endemic misogyny and disregard for the lives of women and girls.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

It’s time to consider who loses when money comes cheap

It’s time to consider who loses when money comes cheap

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Joshua Pearl 21 APR 2021

Monetary policy has yielded substantial social and economic benefits to modern economies.

Not least the achievement of low and predictable price stability. But to whose benefit?

It’s no secret that monetary policy increases the wealth inequality gap. That’s because it benefits those with assets, and by doing so it widens the chasm between the very rich and everyone else, making many Australians – in particular, the least financially secure – worse off.

While governments and central banks are openly aware of the inequalities these policies create, they have not taken measures to appropriately address the issue – the first step of which would be to update the RBA’s mandate.

Let me explain why. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has again announced that it’s kept the official cash rate on hold at 0.1 per cent, with the possibility it will remain thus until 2024. An RBA document released under a Freedom of Information request estimated that a permanent 1% cash rate reduction increases house prices by 30% over a three-year period.

For a middle-class family who own a $800k (median Australian) home, a 1% interest rate reduction increases their wealth by $240k. For the very rich who own a $100m portfolio of properties, their wealth increases by $30m, a windfall gain $29.76m greater than that of the middle-class.

For the one-third of Australians who do not own a home, not only does their net wealth remain unchanged, but the cost of entry becomes substantially higher. They are forced to work, save and pay more for essential assets such as housing, perpetuating the cycle and widening the gap.

The fiscal equivalent is government awarding a grant of $30m to people with $100m in assets; $240k to people with $800k in assets; and nothing to people without assets.

You don’t need to be an arch-communist to consider these outcomes unfair. However, the nature of the unfairness will depend upon the theory of justice invoked. For example, equality of outcome theory finds the unequal impacts of monetary policy unjust because Australians end up with different outcomes.

Alternatively, a Rawlsian theory of justice contends that social inequality is permissible only where the inequality benefits the least well-off to the greatest extent possible – a principle known as the difference principle. For a Rawlsian, existing monetary policies are unjust because there are alternate policies (including tax and transfer and direct cash transfer policies), that would be of greater benefit to the least well-off members of society.

The theory of justice I find most compelling is equality of opportunity. Like most theories of justice, equality of opportunity can be interpreted in different ways. What I have in mind is substantive equality of opportunity theory, which holds a fair society as one where individuals with the same level of talent and motivation, have the same prospects for success, regardless of their place in the social system.

Most Australians believe equality of opportunity is an important feature of our national ethos. Indeed, many Australian politicians cite equal opportunity as a key element of a just society (even if this rhetoric is not always followed with policy). Yet what we are seeing here is falling short of that ideal.

Monetary policy that penalises the least well-off and rewards people based on their starting level of wealth does not provide Australians with equal opportunity.

Indeed, justifying why the very rich deserve windfall gains is challenging unless one ascribes to the slightly perverse virtue theory that to have wealth is to deserve more wealth.

One solution is for government to tax and transfer windfall monetary policy gains. This policy might allocate an equal benefit to each Australian, or otherwise ensure each Australian has an equal opportunity to benefit.

While simple in theory, there are several practical shortcomings with this approach. One issue is measurement: for any asset value increase, determining the increase due to monetary policy versus other factors, such as asset improvements, is not straightforward. Another issue is timing: there is typically a substantial lag between monetary policy actions and asset value increases.

However, it seems to me, the most substantial issue is political pressure from vested interest groups. Taxing assets – regardless of whether people have earned those assets or the assets were merely granted to them through government policy – is eminently harder than simply not transferring windfall wealth in the first place.

Finding prevention, rather than jumping straight to the cure, has the added benefit of avoiding the unnecessary social antagonism that occurs when creating groups of “us” (the “lifters” who are taxed) and “them” (the “leaners” who receive).

A preventative solution can be found in updating the RBA’s mandate, a change that might take on various degrees. The more substantiative update would be to require all future monetary policy to produce no negative impact on wealth inequality. This would make some existing policies unviable or mean that if pursued they must be coupled with additional mechanisms that even up the ledger for the middle and lower classes.

A middle ground alternative might merely begin by requiring the RBA to consider unfair wealth impacts as tiebreakers. For example, when all other features of opposing policy are equal, that which provides all Australians equal opportunity to benefit would be considered preferential. This mandate should require the RBA to consider various options and justify those adopted on the principle of fairness, relative to the alternatives that were overlooked.

Reserve Bank Governor, Dr Philips Lowe recently stated that the responsibility for controlling asset prices is not that of the RBA: “That’s not our mandate. I don’t think it’s sensible and I don’t think it’s even possible”.

That the RBA cannot and does not control asset prices is similar to the fact that the RBA cannot and does not control the social phenomenon of inflation.

Yet the RBA can and does influence asset prices, simply look at the ripple effect of the 0.1% cash rate. The RBA can and does also target asset prices, noting the RBA bond-buying programs which are designed to prop up bond prices. To suggest otherwise is misleading.

Like any other public institution, the RBA is accountable to those they serve – the general public – not to their own ends. And the Australian public may want a little more rigour in that accountability than, ‘that’s not our mandate’ when dismissing the policy options put forth by economists such as Milton Friedman, Frederic Mishkin and Patrick Honohan.

It might be true that alternative policy options such as cash transfers through the budget (where the central bank issues money directly to the government who distribute it) or direct cash transfers (where the central bank issues money directly) are unworkable.

However, allowing the RBA to dismiss their policies’ negative effects because their mandate does not require this consideration, is not something Australians should consider acceptable.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Holly Kramer on diversity in hiring

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Banks now have an incentive to change

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why businesses need to have difficult conversations

BY Joshua Pearl

Joshua Pearl is the head of Energy Transition at Iberdrola Australia. Josh has previously worked in government and political and corporate advisory. Josh studied economics and finance at the University of New South Wales and philosophy and economics at the London School of Economics.

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Lauren Rosewarne 19 APR 2021

In recent weeks, Unilever—the company behind a swag of domestic and personal care brands like Ponds and Lynx and Vaseline—announced that it would abandon “excessive digital alterations” in its advertising.

This isn’t a new public preoccupation for the company: in the 2010s one of its brands, Dove, aimed to position itself as a progressive corporation passionate about self-esteem and body image. Cue soap sales pitches packaged up with messages about hair-love and the perils of Photoshop.

I’m less interested in Unilever’s latest marketing gimmick, and much keener to examine the cultural debates that such a move contributes to.

In conversations with students about pop culture it quickly becomes apparent that most are convinced that The Media is a problem. Entertaining, enthralling, escapist, sometimes even educative – but a problem nonetheless. Students are always exceedingly well prepared to talk about the ways that The Media impacts self-esteem and are often armed with data on the extent of digital manipulation, ready to share robust views on “bias”.

Admittedly, I quite love that media literacy is like fluoride in the water for a generation and thoroughly appreciate that they can spot a filter or digital liposuction-induced wall-warp a mile away.

Being able to detect these things is an essential skill in navigating the glossy touts covering our screens. But such skills often lead to overconfidence about the next bit of the equation: what happens after we view all these artfully tweaked photos. About the consequences.

Such ideas aren’t new. Debates about the power and influence of media have kept scholars busy for over a century: radio was going to dangerously distract us, television was going to morally corrupt us, and the addictive properties of the internet would prevent us ever again turning away from our screens.

In discussing media content, in recognising a digitally altered photograph, we seem to dramatically overestimate our ability to predict what’s done with this information. Somehow apparently, instinctually, we just know that these images contribute to how we feel about our bodies, our relationships, our happiness. We just know that if The Media did a “better job” —reflected our lives more accurately, portrayed us in our full diversity and complexity —we’d have a better, more tolerant, less violent and vitriolic world.

In recognising a digitally altered photograph, we seem to dramatically overestimate our ability to predict what’s done with this information.

In talking about The Media as though it’s just one thing, one entity, and that the meetings are held on Thursdays to plot an agenda, overlooks not only the enormous variety of content—produced by different people in different countries with different budgets and different politics—but with the overarching agenda of just making money.

The output that we’re discussing when we refer to The Media —films and television and advertisements and news —are commercial endeavours. Content can absolutely be commercial and creative, or commercial and ideological. But when the primary goal is making money, suddenly all the social engineering often speculated upon is, in fact, just ways of interpreting content made purely to capture and hold our attention long enough to pay the bills.

Add to this, the nature of contemporary media consumption means not only are we getting a broader range of content but we’re dipping in and out of different eras of productions too: new episodes of shows stream on the same platforms as decades old movies and series. Add to this our ready access to content created all over the world. Such a broad catalogue complicates the idea of homogenous messages about anything, let alone beauty standards or cultural values.

The nature of pop culture means its content is consciously created for a broad audience. This doesn’t mean it’s not artistic or political or renegade —it can and sometimes is all of these things. But material produced for a popular audience is primarily made to make money; everything else it might achieve is an externality. Presuming all content producers are somehow in cahoots on an external cultural agenda is misguided.

Kidding ourselves that it’s the job of entertainment media to educate or flatter, overlooks the commercial underpinnings of pop culture.

Placing blame on The Media for our fraught feelings about our bodies, bank balances, love life overlooks there is no single Media entity but rather thousands of individual views, clicks, and likes that we electively undertake and which each play parts in shaping our world views, and which validate the very production decisions we often decry.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

BY Lauren Rosewarne

Lauren Rosewarne is an Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of 11 books, her latest—Why We Remake: The Politics, Economics and Emotions of Film and TV Remakes—was released in 2020.

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2021

It’s not easy to provide a clear definition of emotions. Philosophers and psychologists still haven’t agreed on what they are or whether they’re ethically important.

Most of us have lots of emotions and can name a dozen off the top of our heads pretty quickly. But there’s a lot more to understand. Why do they matter? Are we in control of our emotions? Should we prioritise our reason over our emotion?

Let’s take a look at what philosophy has to say.

Plato: reason rules emotion

For Ancient Greek philosopher Plato, emotion was a core part of our mind. But although it was core, he didn’t think emotions were very useful. He suggested we imagine our mind like a chariot with two horses. One horse is noble and cooperative, the other is wild and uncontrollable.

Plato thought the chariot rider was our reason and the two horses were different kinds of emotions. The noble horse represents our ‘moral emotions’ like righteous anger or empathy. The cranky horse represents more basic passions like rage, lust and hunger. Plato’s ideas set the precedent for Western philosophy in placing reason above and in control of our emotions.

Aristotle: what you feel says something about you

Aristotle had similar ideas and believed the wise, virtuous person would feel the right emotions at the right times. They would be depressed by sad things and angered by injustice. He also believed this appropriate kind of feeling was an important measure of whether you were a good person. He didn’t think you could separate the kind of person you were from the way you felt.

So if you find it funny when someone slips over in a puddle, Aristotle would argue that says something about you. It doesn’t matter whether you then offer them a towel or ask if they’re okay. The amusement you felt in response to their suffering reflects your character. He thought your job is to work hard so instead of laughing at such situations, you feel empathy and concern.

Hume: emotion rules reason

Scottish philosopher David Hume thought this view was naive. He famously said reason is “the slave of the passions”. By this he meant our emotions lead our reason – we never choose to do anything because reason tells us to. We do it because an emotion pushes us to act. For Hume, reason isn’t the charioteer driving our emotions, it’s more like the wagon being pulled along with no control over where it’s headed. It’s the horses – our emotions – calling the shots.

Hume and his friend Adam Smith developed a theory of moral sentiments that used emotion as the basis for their ethical theory. For them, we act virtuously not because our reason tells us it’s the right thing to do, but because doing the right thing feels good. We get a kind of ‘moral pleasure’ from acting well.

Kant: emotion strips our agency

Immanuel Kant thought this whole approach was entirely wrongheaded. He believed emotion had no place in our ethical thinking. For Kant, emotions were pathological – a disease on our thinking. Because we have no control over our emotions, Kant thought allowing them to govern our thinking and action made us ‘automated’, and that it is the only reason that made us autonomous and capable of making truly free decisions.

Freud: our unconscious drives us

More recent ideas have questioned whether there is such a thing as ‘pure reason’ (a concept Kant named one of his books after). Psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud encouraged us to see our motivations as driven by unconscious urges and inclinations. More recent work in neuroscience has revealed the role unconscious bias and heuristics play in our beliefs, thinking and decisions.

This might make us wonder whether the idea that reason and emotion are two separate, rival forces is accurate. Another mode of thinking suggests our emotions are part of our reason. They express our judgements about how the world is and how we’d like it to be. Are we passive victims of our emotions? Do we spontaneously ‘explode’ with anger? Or is it something we choose? Our answer will help us determine how we feel about things like ‘crimes of passions’, impulsive decisions and how responsible we are for the feelings of other people.

Carol Gilligan: What is this sexist nonsense?

You may have noticed that all the names on this list so far are men. For psychologist Carol Gilligan, that’s not a coincidence. In her influential work In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development, Gilligan argued that the widespread suspicion of ethical decisions made on the basis of emotion, concern for other people and a desire to maintain relationships was sexist. Most theorists had argued that reason, not emotion, should drive our decisions. Gilligan pointed out that most of the ‘bad’ ways of making decisions (like showing care for certain people or using emotion as a guide) tended to be the ways women reasoned about moral problems. Instead, she argued that a tendency to pay mind to emotions, value care and connection and prioritise relationships were different modes of moral reasoning; not suboptimal ones.

For a long time, reason and emotion have been pitted against one another. Today, we’re starting to understand that, in many ways, emotions and reason are the same. Our emotions are judgements about the world. Our reasoning is informed by our mood, our environment and a range of other factors. Perhaps the question shouldn’t be “should we listen to our emotions?” but instead “how do we develop the right emotional responses at the right time?” That way, we can rely on our emotions as one of many pieces of information we can use to make better decisions.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are there limits to forgiveness?

There is a moment of gut-wrenching horror in Simon Wiesenthal’s The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.

It begins with Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, at the bedside of a fatally wounded German soldier.

“I am resigned to dying soon,” the soldier said to him. “But before that I want to talk about an experience which is torturing me. Otherwise, I cannot die in peace.” Comforted by Wiesenthal’s attention, the soldier began to confess to his role in a barbaric war crime where around two hundred Jewish men, women, and children were marched into a house and burned alive.

“I must tell you of this horrible deed,” cried the soldier. “Tell you because – you are a Jew.”

The soldier begs for the forgiveness that would grant him a peaceful death. His voice quivered, his hand trembled; his exhaustion and remorse were palpable. But Wiesenthal said nothing. He turned and left the soldier without a word.

A day later, he found out the soldier had died, unforgiven.

Perversely cruel as it might seem, the moment haunts Wiesenthal. Was it wrong to withhold forgiveness to the soldier, given he seemed genuinely repentant?

The Sunflower poses an invitation. “Ask yourself a crucial question, ‘what would I have done?’”, Wiestenthal dares the reader.

Wiesenthal tasks philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and genocide survivors with answering the very same question and features their responses throughout the book.

It’s true that many of us will not find ourselves in such a harrowing situation. But some will. Victims of crime can be invited to participate in restorative justice programs where they face the person who has wronged them. One in five Australian women above fifteen years old have been sexually assaulted or threatened – usually by someone they know.

In these cases, a victim may face an ethical dilemma they haven’t chosen. One that feels cruel to subject them to: they must decide whether to grant or withhold forgiveness.

Earning forgiveness

Should we forgive those who have wronged us? What makes someone worthy of forgiveness? Can forgiveness be wrong?

These questions are important for two reasons. First, forgiveness doesn’t always come naturally. At the moment when we’ve been wronged – often severely and traumatically – it’s doubly difficult to meditate on the ethics of forgiveness.

It’s painful, confusing and morally loaded: after all, who wants to be the person who doesn’t forgive when people who do – even when it seems impossible – is held up as a paragon of virtue and humanity?

But second, we need to understand how forgiveness should work because we’re all going to seek forgiveness at some point. We will all wrong someone else at some stage, in big ways or small. If we’ve done some work thinking about how we want to forgive, we’ve got a roadmap to follow when we’re the ones seeking forgiveness.

In Wiesenthal’s case, the genuine remorse shown by the German soldier is what troubles him. He believes the soldier is truly sorry for what he did. Not everyone agrees – was this man remorseful, or was he just scared to die? But whether or not the soldier was remorseful, we tend to agree that remorse matters for forgiveness. If someone is remorseful, we can at least think about forgiving them. If there’s no remorse, it doesn’t seem like a moral challenge to withhold forgiveness.

Genuine remorse

But expressing remorse is hard. It takes more than the non-pologies theologian L. Gregory Jones calls “spinning sorrow”. It involves acknowledging responsibility and wrongdoing. “I’m sorry you were offended” isn’t remorse. It’s performative, and puts the onus on the victim for their own suffering. In short, it says you were offended; I didn’t do anything offensive. Your suffering is on you. That’s not remorse, that’s pig-headedness.

Remorse demands us to understand the full extent of our wrongdoing.

That it was wrong, why it was wrong, and how that wrongdoing has harmed someone else. Which gives us good reason to think that Wiesthenthal’s soldier is not genuinely remorseful.

The horror of the Holocaust depended on the systematic denial of Jewish personhood. They weren’t seen as individuals – people with lives complex, unique, and infinitely valuable. Instead, they were objects to be treated as others saw fit.

By treating Wiesenthal as ‘a Jew’ – a generic placeholder for the actual people the solider murdered – the German soldier is continuing on with the same abhorrent thinking that led to his crimes in the first place. He doesn’t understand the depth of what he did. How can he then apologise in a way that warrants forgiveness?

The politics of forgiveness

To step away from Wiesenthal’s case for a second, how often do we witness apologies that fail to show any awareness of the source of the wrongdoing? On a political level, we see apologies offered by those who continue to benefit from those injustices. Does this constitute remorse, or a genuine understanding of the wrongdoing?

Take political apologies, for instance: some naysayers to Australia’s National Apology to the Stolen Generations argued that the people apologising weren’t the ones who had done anything wrong. The claim here is if we haven’t done anything wrong, we don’t need to be forgiven; and if we don’t need to be forgiven, why would we apologise?

This perhaps misses an important consideration.

If we continue to benefit from a past wrong and fail to address the source of the continued disadvantage, there is a sense in which we’ve prolonged the wrongdoing.

However, it also calls our attention to the role of status in forgiveness. I cannot offer an apology for a wrong I haven’t been involved in.

Equally, I cannot forgive unless I have been wronged, which also complicates the politics of forgiveness: who has the moral authority to forgive? Could Wiesthenthal, who was treated as a ‘generic Jew’ by the soldier, actually forgive – even if he wanted to? After all, the soldier’s crimes did not directly harm him.

Eva Kor was a Holocaust survivor who offered forgiveness to Josef Mengele, doctor of the notorious ‘twin experiments’ in Auschwitz. Her actions brought criticism from other survivors, who said Kor wasn’t entitled to offer forgiveness on behalf of others. Nor should she pressure them to forgive when they were not ready.

Jona Laks, another ‘Mengele twin’, refused to forgive. In Mengele’s case, this is understandable. But what if there was genuine remorse, a commitment to change, and steps to address the wrongdoing? Would it be wrong to refuse forgiveness?

On some occasions, it seems so. For instance, we consider pettiness – when someone is unable to move past very slight or non-existent wrongs – as a vice, or a mark of bad character. I’m not suggesting a Holocaust survivor (or any Jewish person) who refused to forgive the Nazis under any condition was being petty, but this takes us back to the question posed earlier.

Is there anything that’s unforgiveable?

This brings us to the final question: are there some things which are unforgiveable? How should we think about them?

Maybe. Philosopher, Hannah Arendt believed that unforgiveable crimes were those where no punishment could be given that would be proportionate to the crime itself. Where no atonement is possible, no forgiveness is possible. For Arendt, these crimes are an evil beyond redemption.

In contrast, French philosopher Jacques Derrida argued that conditional forgiveness is in fact, not forgiveness. By withholding forgiveness until considerations (like remorse) are met, Derrida believed that we are forgiving someone who is already innocent – that is, someone who no longer needs forgiveness. Only the unremorseful person remains guilty, and only the unremorseful person actually needs forgiveness.

As a result, Derrida concludes with a paradox: only the unforgiveable can be truly forgiven.

Derrida traces his thinking back to religious traditions where forgiveness is unconditional and uneconomic. It is a gift, not a transaction. This is a view L. Gregory Jones believes is centrally important to avoid “weaponising forgiveness”.

I think it’s important to remember that forgiveness should always be a gift and not an expectation. It’s unfair to expect any person who has been victimized, especially if it’s raw, to be ready to forgive.

And — this is particularly important in domestic violence and other kinds of forgiveness — the expectation of forgiveness is also used as a weapon to punish and perpetuate a cycle. It’s often the case in domestic violence, for example, where the abuser will come and say, “you need to forgive me because you’re a Christian” and the person feels obligated to do that. All that does is perpetuate and intensify the violence rather than remedy it.

So how should we think about Wiesenthal’s case? What would we do? It seems quite evident that he had no duty to forgive this Nazi – and that perhaps he had no right to do so. However, if we set aside the question of legitimacy, how might he make this decision?

Some philosophers have argued that self-respect is central to the way we think about forgiveness. Forgiveness involves a recognition that we have value – that we did not deserve to be wronged, and the other person should not have wronged us.

By forgiving, we assert our status in the moral community – our dignity.

However, others might believe such forgiveness reduces their self-worth – especially if this forgiveness leaves the wrongdoer better off than the victim. Forgiveness can grant peace to wrongdoers – as the German soldier knew – but often leaves the victim alone in their trauma.

Author Susan Cheever once wrote that “Being resentful is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die”. For some, this may be true. For others, forgiving might be like giving someone a drink while you are dying of thirst.

Should Wiesenthal have forgiven the soldier? It might all depend on what he could swallow and still look at himself in the mirror.

It may all come down to what he wanted to see when he looked in the mirror.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

How avoiding shadow values can help change your organisational culture

How avoiding shadow values can help change your organisational culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY John Neil Michelle Bloom The Ethics Centre 15 MAR 2021

Governing culture is a board’s most challenging task. John Neil and Michelle Bloom of The Ethics Centre outline the dangers of “shadow values”. Here’s how to walk the talk.

This article was first published in the March 2021 edition of Company Director magazine for the Australian Institute of Company Directors.

While an organisation might be measured by its share price, profitability or reputation, it is defined by its culture. Culture matters because it influences everything an organisation does. It defines not only individual and team performance, it also influences how organisations manage, change and navigate complexity and uncertainty. While it is critical to an organisation’s performance and reputation, culture is notoriously difficult to identify, measure and evaluate. As a result, understanding and governing culture is a perennial challenge for boards. This is because it is comprised of implicit and explicit dimensions. It includes the shared values, principles and beliefs of people, how they work together and with each other. Many of these dimensions are visible, but many are not.

On the face of it, corporate values of excellence, respect, integrity and communication are admirable and worthy. Most organisations would be happy to identify with them. But Enron espoused these values only 12 months before declaring bankruptcy in 2001 — the largest in US history. The company had received plaudits for its 64-page code of ethics and Fortune magazine named it “America’s Most Innovative Company”. It had received numerous awards for its corporate citizenship and environmental policies.

Enron’s failings have been well documented as the prototypical case study of what can happen when an organisation decouples values from its behaviours. Less well-documented is how the implicit and unstated dimensions of an organisation’s culture shape and influence for better or worse. These aspects of culture determine what and how things get done in organisations and are driven by the implicit values/principles people hold.

“The biggest challenge for boards in governing culture is that while unspoken dimensions are difficult, but not impossible, to identify and measure, they are more powerful than the official ones because they operate below the surface.” – John Neil, The Ethics Centre

The dark side

The biggest challenge for boards in governing culture is that while unspoken dimensions are difficult, but not impossible, to identify and measure, they are more powerful than official ones because they operate below the surface. They are key to changing an organisation’s culture because they more closely reflect its actual operating culture — its “shadow” values and principles. In psychology, the alter ego is the dark side of human nature. Jung identified it as the “shadow” to describe the subterranean aspects of the psyche; those unpleasant traits we prefer to hide. As in the psyche, the shadow gains its power in an organisation by being repressed and unacknowledged, which manifests in unintended, often detrimental behaviours.

Shadow values are typically cultivated in environments where organisations are stressed by the complexity of changes occurring or a lack of focus on supporting cultural alignment with existing values and principles.

In our work with a financial services company, our evaluation revealed each of its official organisational values had powerful corollaries (shadow values) that served to shift the organisation off course significantly. One of these official values was excellence. While officially expressed in a tagline, it was experienced and evaluated in ways such as “having pride in our work”, “being willing to challenge”, and “continuous improvement”. We also found it manifested itself through a powerful shadow side driven by the unstated value of success — in behaviours such as “individualistic”, “maintain status”, and “hit targets at all cost”.

The key driver of this shadow value was an unwavering focus on “the numbers”. While the measurement of inputs, and outcomes was regarded as a management responsibility, in this individualistically success-oriented culture, hard metrics such as hitting the numbers came to serve as the sole measure of success. Individual behaviours became distorted in pursuit of that goal alone, obscuring non-financial costs and risks, which, when not easily calculable are not seen, let alone prioritised. Unintended consequences of not being aware of or managing shadow values were highlighted in the Banking Royal Commission.

Alternate shadows

The connotations of “shadow” overstate the negative effect of these values. While an organisation’s shadow values at their worst are less constructive mutations of the official ones and will always benefit from being exposed and dealt with, there are two other types, both potentially of great value for an organisation to identify and unlock.

The first is neutral in relation to the existing values/principles but offers significant potential for tipping into positive or negative manifestations. In our work with the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC), its value of excellence — with associated behaviours and traits of exemplary performance and achievement by elite Olympic athletes — was undermined by a powerful shadow cast by the implicit value of pragmatism.

The second type of alternate shadow values reinforce, amplify or supplement official values and principles. These were also present at the AOC (see breakout, right).

In our work with a large superannuation fund, a primary shadow value was that of harmony, operating below the stated value of excellence. The value of excellence was commonly expressed in behaviours such as “keeping costs low”, “continuous improvement” and “leading the industry”. The shadow value of harmony in its most positive expression meant people were respected and included. At its worst, it manifested in the avoidance of conflict, resulting in over-consultation, delaying and avoiding difficult decisions. As a result, excellence was hamstrung by a lack of agility and responsiveness to the changing environment and competitive pressures, with innovative ideas often deferred until unreasonably high standards of mitigation were in place.

Getting below the surface

Particularly for boards wanting a “true read” of a culture, a challenge is getting below the surface-level reporting facade. Because of its intangible nature, culture is not easily distilled into standard metrics. Complaints, grievance resolution time, staff turnover and engagement surveys provide a limited view of the dynamics underpinning the culture — but often, they are the board’s only sources of information. While they may identify a range of proxies for an explicit culture, they are of little use in identifying implicit beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that actually drive the operating culture.

A significant limitation is a reliance on self-reporting. One organisation we worked with displayed a widespread cultural practice in staff surveys and performance reviews. “Click five to stay alive” referred to the five-point Likert scales used to evaluate a leader’s performance — and to an expectation for subordinates to rate leaders as a “five” across all evaluation criteria to avoid recriminations. Not only did these reports give an inaccurate evaluation of performance, they also underlined a range of potential shadow values linked to inappropriate use of positional power, fear of reprisals and lack of trust.

Unless board members are particularly proactive through direct engagement with staff, having visibility of the actual operating culture beyond what management reports provide is difficult. While there is no substitute for direct engagement — in particular with how the executive team works — using tools that better uncover shadow values can help boards better see the risks and opportunities below the surface — and thereby govern more effectively.

John Neil is Director of Innovation and Michelle Bloom Director of Consulting and Leadership at The Ethics Centre. They offer Shadow Value Assessments, working directly with organisations to identify and remedy the alignment gap between the official values and the lived culture and behaviours. Find out more.

Case study: Australian Olympic Committee

Pragmatism was held in high regard as a leadership trait in the AOC. This infiltrated into ways of working and modes of governance. When the organisation shifted into “games mode” where pressures on effective delivery were intense, pragmatism exercised its greatest influence. At times, the ends justified the means, with governance standards, and operating processes temporarily suspended to expedite results. But organisational challenges compounded over time. When the AOC switched back into “non-delivery mode”, it was difficult to recalibrate around its official values, principles and sanctioned ways of working.

In our work with the AOC, we also found shadow values that reinforced the official values. There was a consistently understood and practically used principle of “athletes first”, which reinforced and amplified each of the official values, in particular that of excellence. While not recognised as an official value or principle, it influenced many desirable behaviours, judgements and decisions directly in service of the needs of athletes. In other organisations it may have been expressed as an official value of “service” or a principle such as “act in the client’s best interest”. But as a shadow principle, it was no less effective than these stated principles. It was commonly applied as a rule of thumb to many decisions made throughout the organisation — and most people defaulted to it.

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Louise Richardson-Self 10 MAR 2021

On 4 March 2021 Attorney General Christian Porter identified himself as the unnamed Minister who had been accused of a 1988 rape in a letter sent to the Prime Minister and some senators.

He strenuously denies any wrongdoing and has refused to step down from his role.

ABC News reports that ‘the letter urges the Prime Minister to set up an independent parliamentary investigation into the matter’ — but should there be an investigation?

The Problem With Testimony

When it comes to accusations of sexual assault, it seems like the situation comes down to a clash of ‘testimony’ — she said, he said. But who is to be believed?

Testimony, to clarify, isn’t just any old speech act. Testimony is speech that is used as a declaration in support of a fact. “The sky is blue” is testimony; “I like strawberries” isn’t.

Generally, people are hesitant to accept testimony as good, or strong evidence for any sort of claim. This is not because testimony is always unreliable, but because we think that there are more reliable methods of attaining knowledge.

Other methods include direct experience (living through or witnessing something), material collection (looking for evidence to support the truth of a claim), or through the exercise of reason itself (for instance, by way of logic or deductive reasoning).

In this case, it seems like what would need to occur is a fact-finding mission which could add weight either to the testimony of either Porter or the alleged victim.

What is very surprising, then, is that only some people support such an investigation, while others have rejected the move as unnecessary, including Prime Minister Scott Morrison. These people deem Porter’s testimony credible. But should they?

Judging Credibility

It isn’t strange to find that people are willing to treat testimony as sufficient evidence for a claim. We often do. Testimony is used in trials. Every news report is testimony. The scientific truths we have learn from books or YouTube are testimony. You get the picture. We may think we are always sceptical of testimony, but we could hardly get by without it.

So, we do rely on testimony. Just not all testimony. When it comes to believing testimony, what we’re really doing is judging the speaker’s credibility. The question is thus: should we trust what a specific person says about a specific matter in a specific context?

The problem is that we’re actually not very good at working out which speakers are credible and which aren’t. Often we get it wrong. And sometimes we get it wrong because of implicit biases—biases about types of people, biases about institutions, and the sway of authority.

As philosopher Miranda Fricker has pointed out, when people do not receive the credibility they are due—whether because they receive too much (a credibility excess) or too little (a credibility deficit)—and the reason they do not receive it is because of such biases, then a testimonial injustice occurs.

“Being judged credible to some degree is being regarded as more credible than others, less credible than others, and equally credible as others,” explains philosopher José Medina.

In a she said, he said case, if we judge one person as credible, we’re also discrediting the other.

Fricker explains that testimonial injustice produces harms. First, there is a harm caused to the listener: because they didn’t believe testimony they should have, they failed to acquire some new knowledge, which is a kind of harm.

However, testimonial injustices also harms the speaker. When someone’s testimony is doubted without good reason, we disrespect them by doubting their ability to convey truth – which is part of what defines us as humans. This means testimonial injustices symbolically degrade us qua [as] human. Basically, to commit a testimonial injustice means we fail to treat people in a fundamentally respectful way. Instead, we treat them as less than fully human.

Is there a Credibility Deficit or Excess in Porter’s case?

Relevant to the issue of credibility attribution in the wake of a sexual assault allegations is the perception (and fear) shared by many that women lie about sexual assault.

In fact, approximately 95% of sexual assault allegations are true. This means it is highly improbable (but not impossible) that the alleged victim made a false claim.

It is not just stereotyping about lying and vindictive women that can interfere with correct credibility attribution. As Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has reminded us, Porter “is entitled to the presumption of innocence, as any citizen in this country is entitled.”

This commitment we share to presume innocence unless or until guilt is proven is a significant bulwark of our ethico-legal value system.

However, in a case of “she said, he said”, his entitlement to the presumption of innocence automatically generates the assumption that the victim is lying. Given that false rape allegations are so infrequent, the presumption of innocence unfairly undermines the credibility of the complainant almost every time.

This type of testimonial injustice may seem unavoidable because we cannot give up the presumption of innocence; it is too important. However, the insistence that Porter receive the presumption of innocence rather than insisting we believe the statistically likely allegations against him may point to another problem with the way assign credibility.

As philosopher Kate Manne has observed, particularly when it comes to allegations made by women of sexual assault by men, the accused are often received with himpathy—that is, they receive a greater outpouring of sympathy and concern over the complainants. She explains, “if someone sympathizes with the [accused] initially…he will come to figure as the victim of the story. And a victim narrative needs a villain…”

So here’s the rub.

If a great many people in a society share the view that women lie, then they tacitly see complainants as uncredible.

And if a great many people in a society feel sorry for certain men who are accused of sexual assault, then they are likely to side with the accused. In turn, those who are accused of sexual assault (usually, men) will automatically receive a credibility excess.

Is this what has happened in Porter’s case? Note that an investigation could lend credibility to either party’s claims. This is where the police would normally step in.

Didn’t the Police Investigate and Exonerate Porter?

You would be forgiven for thinking that NSW Police had conducted a thorough investigation and had cleared Porter’s name judging by the way some powerful parliamentary figures have responded to Porter’s case.

For example, in his dismissal of calls for an independent investigation, Scott Morrison said that it “would say the rule of law and our police are not competent to deal with these issues.” Likewise, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said: “The police are the only body that are authorised to deal with such serious criminal matters.” Nationals Senator Susan MacDonald also opposed the investigation, saying: “We have a system of justice in this country [and] a police service that is well resourced and the most capable of understanding whether or not evidence needs to go to trial — and they have closed the matter.”

Case closed. This must mean that there’s no evidence and that an independent inquiry would be pointless, right?

Not quite. NSW Police stated that there was “insufficient admissible evidence” to proceed with an investigation. They did not say that there was no evidence of misconduct. Moreover, the issue for criminal proceedings is that the alleged victim did not make a formal statement before she took her own life.

In other words, the complainant’s testimony does not get to count as evidence because, technically, there is no testimony on the record.

Preventing Testimonial Injustice

Since the alleged victim had not made a formal statement to Police at the time of her death, the call for an investigation into Porter’s conduct can be seen as a means of ensuring Porter does not receive a testimonial credibility excess and the complainant a testimonial credibility deficit.

To stand by Porter’s testimony in a context where it is widely – and falsely – believed that women make false rape allegations, and where the police are seen as the only body capable of exercising an investigation (when in fact they are not), would be to commit a testimonial injustice.

As former Liberal staffer and lawyer Dhanya Mani says, “The fact that the police are not pursuing the matter for practical reasons does not preclude or prevent the Prime Minister from undertaking an inquiry into a very serious allegation… And that inquiry will either exonerate Christian Porter and prove his innocence or it will prove otherwise.”

It is important to understand that an independent investigation is not bound by the exact same evidentiary rules as are the police and courts. It may be possible for others to testify on her behalf. Other evidence which is inadmissible in court may be admissible here. An independent investigation at least offers the possibility that the complainant’s testimony will get a fair hearing.

Also worth noting is where the presumption of innocence would end. For a crime, guilt should be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. For civil cases, that standard is “on the balance of probabilities”. What standard should an independent investigation use? I would suggest the latter, precisely because testimony is likely to be all the evidence there is.

To prevent a testimonial injustice—attributing too much credibility, or too little, to someone undeserving of it—these allegations must be investigated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

BY Louise Richardson-Self

Louise Richardson-Self is a Lecturer in Philosophy and Gender Studies at the University of Tasmania and an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Awardee (2019). Her current research focuses are the problem online hate speech, and the tension between LGBT+ non-discrimination and religious freedom. She is the author of Justifying Same-Sex Marriage: A Philosophical Investigation (2015) and her second book, Hate Speech Against Women Online: Concepts and Countermeasures is due for publication in 2021.

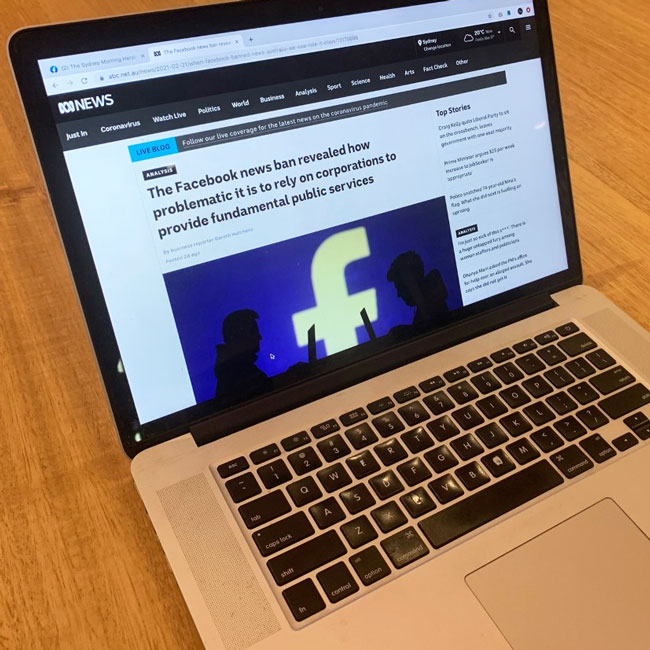

Who's to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 25 FEB 2021

News will soon return to Facebook, with the social media giant coming to an agreement with the Australian government. The deal means Facebook won’t be immediately subject to the News Media Bargaining Code, so long as it can strike enough private deals with media companies.

Facebook now has two months to mediate before the government gets involved in arbitration. Most notably, Facebook have held onto their right to strip news from the platform to avoid being forced into a negotiation.

Within a few days, your feed will return to normal, though media companies will soon be getting a better share of the profits. It would be easy to put this whole episode behind us, but there are some things that are worth dwelling on – especially if you don’t work in the media, or at a social platform but are, like most of us, a regular citizen and consumer of news. Because when we look closely at how this whole scenario came about, it’s because we’ve largely been forgotten in the process.

Announcing Facebook’s sudden ban on Australian news content last week, William Easton, Managing Director of Facebook Australia & New Zealand wrote a blog post outlining the companies’ reasons. Whilst he made a number of arguments (and you should read them for yourself), one of the stronger claims he makes is that Facebook, unlike Google Search, does not show any content that the publishers did not voluntarily put there. He writes:

“We understand many will ask why the platforms may respond differently. The answer is because our platforms have fundamentally different relationships with news. Google Search is inextricably intertwined with news and publishers do not voluntarily provide their content. On the other hand, publishers willingly choose to post news on Facebook, as it allows them to sell more subscriptions, grow their audiences and increase advertising revenue.”

The crux of the argument is this. Simply by existing online, a news story can be surfaced by Google Search. And when it is surfaced, a whole bunch of Google tools – previews, summaries from Google Home, one-line snippets and headlines – give you a watered-down version of the news article you search for. They give you the bare minimum info in an often-helpful way, but that means you never click the site or read the story, which means no advertising revenue or way of knowing the article was actually read.

But Facebook is different – at least, according to Facebook. Unless news media upload their stories to Facebook, which they do by choice, users won’t see news content on Facebook. And for this reason, treating Facebook and Google as analogous seems unfair.

Now, Facebook’s claims aren’t strictly true – until last week, we could see headlines, a preview of the article and an image from a news story posted on Facebook regardless of who posted it there. And that headline, image and snippet are free content for Facebook. That’s more or less the same as what Facebook says Google do: repurposing news content that can be viewed without ever having to leave the platform.

However, these link previews are nowhere near as comprehensive as what Google Search does to serve up their own version of news stories for the company’s own purpose and profit. Most of the news content you see on Facebook is there because it was uploaded there by media companies – who often design video or visual content explicitly to be uploaded to Facebook and to reach their audience.

However, on a deeper level, there seem to be more similarities between Google and Facebook than the latter wants to admit, because the size and audience base Facebook possesses makes it more-or-less essential for media organisations to have a presence there. In a sense, the decision to have a strategy on Facebook is ‘voluntary’, but it’s voluntary in the same way that it’s voluntary for people to own an attention-guzzling, data sucking smartphone. We might not like living with it, but we can’t afford to live without it. Like inviting your boss to your wedding, it’s voluntary, but only because the other options are worse.

Facebook would likely claim innocence of this. Can they really be blamed for having such an engaging, effective platform? If news publishers feel obligated to use Facebook or fall behind their competitors that’s not something Facebook should feel bad about or be punished for. If, as Facebook argue, publishers use them because they get huge value from doing so, it does seem genuinely voluntary – desirable, even.

Even if this is true, there are two complications here. First, if news media are seriously reliant on Facebook, it’s because Facebook deliberately cultivated that. For example, five years ago Facebook was a leading voice behind the ‘pivot to video’, where publishers started to invest heavily in developing video content. Many news outlets drastically reduced writing staff and investment in the written word, instead focussing on visual content.

Three years later, we learned that Facebook had totally overstated the value of video – the pivot to video, which served Facebook’s interests, was based on a self-serving deception. This isn’t the stuff of voluntary, consensual relationships.

Let’s give Facebook a little benefit of the doubt though. Let’s say they didn’t deliberately cultivate the media’s reliance on their platform. Still, it doesn’t follow obviously from this that they have no responsibility to the media for that reliance. Responsibility doesn’t always come with a sign-up sheet, as technology companies should know all too well.

French theorist Paul Virilio wrote that “When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution.” Whilst Virilio had in mind technology’s dualistic nature, modern work in the ethics of technology invites us to interpret this another way.

If inventing a ship also invents shipwrecks, it might be up to you to find ways to stop people from drowning.

Technology companies – Facebook included – have wrung many a hand talking about the ‘unintended consequences’ of their design and accepting responsibility for them. In fact, speaking before a US Congress Committee, Mark Zuckerberg himself conceded as much, saying:

“It’s clear now that we didn’t do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm, as well. And that goes for fake news, for foreign interference in elections, and hate speech, as well as developers and data privacy. We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake. And it was my mistake. And I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I’m responsible for what happens here.”

It seems unclear why Facebook recognised their responsibility in one case, but seem to be denying it in another. Perhaps the news media are not reliant – or used by – Facebook in the same way as they are Google, but it’s not clear this goes far enough to free Facebook of responsibility.

At the same time, we should not go too far the other way, denying the news media any role in the current situation. The emergence of Facebook as a lucrative platform seems to have led the media to a Faustian pact – selling their soul for clicks, profit and longevity. In 2021 it seems tired to talk about how the media’s approach to news – demanding virality, speed, shareability – are a direct result of their reliance on platforms like Facebook.

The fourth estate – whose work relies on them serving the public interest – adopted a technological platform and in so doing, adopted its values as their own: values that served their own interests and those of Facebook rather than ours. For the media to now lament Facebook’s decision as anti-democratic denies the media’s own blameworthiness for what we’re witnessing.

But the big reveal is this: we can sketch out all the reasons why Facebook or the media might have the more reasonable claim here, or why they share responsibility for what went down, but in doing so, we miss the point. This shouldn’t be thought of as a beef between two industries, each of whom has good reasons to defend their patch.

What needs to be defended is us: the community whose functioning and flourishing depends on these groups figuring themselves out.

Facebook, like the other tech giants, have an extraordinary level of power and influence. So too do the media. Typically, we don’t to allow institutions to hold that kind of power without expecting something in return: a contribution to the common good. This understanding – that powerful institutions hold their power with the permission of a community they deliver value to – is known as a social license.

Unfortunately, Facebook have managed to accrue their power without needing a social license. All power, no permission.

This is in contrast to the news media, whose powers aren’t just determined by their users and market share, but by the special role we afford them in our democracy, the trust and status we afford their work isn’t a freebie: it needs to be earned. And the way it’s earned is by using that power in the interests of the community – ensuring we’re well-informed and able to make the decisions citizens need to make.

The media – now in a position to bargain with Facebook – have a choice to make. They can choose to negotiate in ways that make the most business sense for them, or they can choose to think about what arrangements will best serve the democracy that they, as the ‘fourth estate’, are meant to defend. However, at the very least they know that the latter is expected of them – even if the track record of many news publishers gives us reason to doubt.

Unfortunately, they’re negotiating with a company whose only logic is that of a private company. Facebook have enormous power, but unlike the media, they don’t have analogous mechanisms – formal or informal – to ensure they serve the community. And it’s not clear they need it to survive. Their product is ubiquitous, potentially addictive and – at least on the surface – free. They don’t need to be trusted because what they’re selling is so desirable.

This generates an ethical asymmetry. Facebook seem to have a different set of rules to the media. Imagine, for a moment, if the media chose to stop reporting for a fortnight to protest a new law. The rightful outrage we would feel as a community would be palpable. It would be nearly unforgivable. And yet we do not hold Facebook to the same standards. And yet, perhaps at this point, they’ve made themselves almost as influential.

There’s a lot that needs to happen to steady the ship – and one of the most frustrating things about it is that as individuals, there isn’t a lot we can do. But what we can do is use the actual license we have with Facebook in place of a social license.

If we don’t like the way a news organisation conducts themselves, we cancel our subscriptions; we change the channel. If you want to help hold technology companies to account, you need to let your account to the talking. Denying your data is the best weapon you’ve got. It might be time to think about using it – and if not, under what circumstances you might.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2021

We believe conversations matter. So when we had the opportunity to chat with Tim Soutphommasane we leapt at the chance to explore his ideas of a civil society. Tim is an academic, political theorist and human rights activist. A former public servant, he was Australia’s Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission from 2013 – 2018 and has been a guest speaker at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. Now a professor at Sydney University, he shared with The Ethics Centre his thoughts on the role of the media, free speech, racism and national values.

What role should the media play in supporting a civil society?

The media is one place where our common life as a society comes into being. It helps project to us our common identity and traditions. But ideally media should permit multiple voices, rather than amplify only the voices of the powerful. When it is dominated by certain interests, it can destroy rather than empower civil society.

How should a civil society reckon with the historical injustices it benefits from today?

A mature society should be able to make sense of history, without resorting to distortion. Yet all societies are built on myths and traditions, so it’s not easy to achieve a reckoning with historical injustice. But, ultimately, a mature society should be able to take pride in its achievements and be critical of its failings – all while understanding it may be the beneficiary of past misdeeds, and that it may need to make amends in some way.

Should a civil society protect some level of intolerance or bigotry?

It’s important that society has the freedom to debate ideas, and to challenge received wisdom. But no freedom is ever absolute. We should be able to hold bigotry and intolerance to account when it does harm, including when it harms the ability of fellow citizens to exercise their individual freedoms.

What do you think we can do to prevent society from becoming a ‘tyranny of the majority’?

We need to ensure that we have more diverse voices represented in our institutions – whether it’s politics, government, business or media.

What is the right balance between free speech and censorship in a civil society?

Rights will always need to be balanced. We should be careful, though, to distinguish between censorship and holding others to account for harm. Too often, when people call out harmful speech, it can quickly be labelled censorship. In a society that values freedom, we naturally have an instinctive aversion to censorship.

How can a society support more constructive disagreement?

Through practice. We get better at everything through practice. Today, though, we seem to have less space or time to have constructive or civil disagreements.

What is one value you consider to be an ‘Australian value’?

Equality, or egalitarianism. As with any value, it’s contested. But it continues to resonate with many Australians.

Do you believe there’s a ‘grand narrative’ that Australians share?

I think a national identity and culture helps to provide meaning to civic values. What democracy means in Australia, for instance, will be different to what it means in Germany or the United States. There are nuances that bear the imprint of history. At the same time, a national identity and culture will never be frozen in time and will itself be the subject of contest.

And finally, what’s the one thing you’d encourage everyone to commit to in 2021?

Talk to strangers more.

To read more from Tim on civil society, check out his latest article here.

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Brother is coming to a school near you

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Settler rage and our inherited national guilt

Settler rage and our inherited national guilt

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Sarah Maddison 21 JAN 2021

Professor Marcia Langton offers a distinctive term for settler-Australian racism towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She calls it the ‘settler mentality’. In her FODI Digital lecture Langton suggests that the experience of living unjustly on stolen Indigenous lands has produced in settler Australians a ‘peculiar hatred’ expressed through ‘settler rage against the people with whom they will not treat.’

While Langton observes the manifold evidence of ‘classical, formal racism’, she maintains that the underlying problem in Australia is ‘a settler population that cannot come to terms with its Indigenous population.’ Here, Langton touches upon a long running debate among scholars seeking to understand the ongoing conflict in Indigenous-settler relations. For some, race—and racism—are the primary lens for understanding both historical and contemporary injustice.

On this view, colonialism is in service to racism, enabling a white supremacist nation to take root on this continent. There is an abundance of evidence to support that claim, for example in the history of eugenicist practices in Australia including the ‘degrees of blood’ that for decades were used to justify the separation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families.

But for me there has always been more weight to support the counter view expressed by Langton.

Racism is real, certainly, but it operates in service to colonialism.

Colonialism cares less about the skin colour of the peoples it dispossesses and far more about accessing and controlling their land. It is in pursuit of land and the resources in and of that land that colonisers everywhere have committed atrocities against Indigenous peoples.

Australia is no exception. It is colonisation and the subsequent failure to negotiate treaties with First Nations on this continent that give rise to the settler state’s moral and legal illegitimacy. Colonisation is violent—no people anywhere in the world have been dispossessed of their land peacefully, and again, Australia is no exception.

Despite the state’s steadfast refusal to properly acknowledge this history, the evidence of over a century of frontier warfare is no secret. It never has been.