Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2017

Freedom of speech refers to people’s ability to say what they want without punishment.

Most people focus on punishment by the state but social disapproval or protest can also have a chilling effect on free speech. The consequences of some kinds of speech can make people feel less confident in speaking their mind at all.

Since most philosophers agree there is no such thing as absolute free speech, the debate largely focuses on why we should restrict what people say. Many will state, “I believe in free speech except…”. What comes after that? This is where the discussion on what the exceptions and boundaries to free speech are.

Even John Stuart Mill, who is so influential on this topic we need to discuss his ideas at length, thought free speech has limits. You would usually be free to say, “Immigrants are stealing our jobs”. If you say so in front of an angry mob of recently laid off workers who also happen to be outside an immigrant resource centre, you might cause violence. Mill believed you should face consequences for remarks like these.

This belief stems from Mill’s harm principle, which states we should be free to act unless we’re harming someone else. He thought the only speech we should forbid is the kind that causes direct harm to other people.

Mill’s support for free speech is related to his consequentialist views. He thought we should be governed by laws leading to the best long-term outcomes. By allowing people to voice their views, even those we find immoral, society gives itself the best chance of learning what’s “true”.

This happens in two ways. First, the majority who think something is immoral might be wrong. Second, if the majority are right, they’ll be more confident of their position if they’ve successfully argued for it. In either case, free speech will improve society.

If we silence dissenting views, it assumes we already have the right opinion. Mill said “all silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility”.

Accepting the limits of our own knowledge means allowing others to speak their mind – even if we don’t like what they’ve got to say.

As Noam Chomsky said, “If you’re in favour of freedom of speech, that means you’re in favour of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise”.

Free speech advocates tend to limit restrictions on speech to ‘direct’ harms like violence or defamation. Others think the harm principle is too narrow in definition. They believe some speech can be emotionally damaging, socially marginalising, and even descend into hate speech. They believe the speech that causes ‘indirect’ harms should also be restricted.

This leads people to claim citizens do not have the right to be offensive or insulting. Others disagree. Some don’t believe offence is socially or psychologically harmful. Furthermore, they suggest we cannot reasonably predict what kinds of speech will cause offence. Whether speech is acceptable or not becomes subjective. Some might find any view offensive if it disagrees with their own, which would see increasing calls for censorship.

In response, a range of theorists suggest offending is harmful and causes injury. They also say it has insidious effects on social cohesion because it places victims in a constant state of vulnerability.

In Australia, Race Commissioner Tim Soutphommasane is a strong proponent of this view. He believes certain kinds of speech “undermine the assurance of security to which every member of a good society is entitled”. Judith Butler goes further. She believes once you’ve been the victim of “injurious speech”, you lose control over your sense of place. You no longer know where you are welcome or when the next abuse will occur.

For these reasons, those who support only narrow limits to free speech are sometimes accused of prioritising speech above other goods like harmony and respect. As Soutphommasane says, “there is a heavy price to freedom that is imposed on victims”.

Whether you think offences count as harms or not will help determine how free you think speech should be. Regardless of where we draw the line, there will still be room for people to say things that are obnoxious, undiplomatic or insensitive without formal punishment. Having a right to speak won’t mean you are always seen as saying the right thing.

This encourages us to include ideas from deontology and virtue ethics into our thinking. As well as asking what will lead to the best society or which kinds of speech will cause harm, consider different questions. What are our duties to others when it comes to the way we talk? How would a wise or virtuous person use speech?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is the right to die about rights or consequences?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 2 FEB 2017

In years past, one of my roles was to take meteorological readings for the north-west sector of the Gulf of Carpentaria. My job was to relay weather readings to an operator in Katherine.

From there they would be added to the data pool used by the Bureau of Meteorology to track and predict Australia’s weather. Although my part was very basic, it was essential. And so it was that I found myself reading the weather at the height of a tropical cyclone.

I stepped into the maelstrom, physically wrestling the wind and exhilarated by this personal encounter with the unbridled power of nature. Meanwhile, other (perhaps more sensible) people were gathered together in shelters. The same cyclone that made me feel alive left them terrified. One phenomenon, two very different responses.

Whatever divides Trump’s supporters from his critics, they are united by one thing – both groups are being buffeted by powerful winds of change.

For me, that cyclone is like President Trump’s emerging impact on the world. The flurry of claims and counter-claims, fake news, alternative facts and the swirling vortex of presidential orders demonstrate enormous power and have provoked diverse responses.

For some people, President Trump is a thrilling departure from ‘politics as normal’. For others, his conduct is a frightening repudiation of all they believe in. Whatever divides Trump’s supporters from his critics, they are united by one thing – both groups are being buffeted by powerful winds of change. As such, they have a common need to find stable anchor points.

Trump supporters risk being swept away on a tide of populism that knows no boundaries and ultimately eats its own. Critics risk their scepticism giving way to outright cynicism, the kind that inevitably corrodes the bonds of human society. Of the two risks, the latter is the greater. Cynicism often ends in resignation and the hopelessness of despair. Citizens disengage and democracies unravel from within.

Neither outcome – self-defeating populism or rampant despair – is inevitable.

History is full of examples of individuals and societies who have lost their ethical bearings, only later to look back in horror at what has been done.

Core values and principles provide the anchor points needed to hold people steady. They are the ground we return to whenever making conscious decisions about how to live as individuals and as a society. Although the specifics may vary between people, places and times, the basic structure is the same. With one important exception, every human being makes choices informed by their values and principles.

The exception is the problem.

Too often, people act without giving much thought to what they are doing. Instead, habits provide the pattern for accepted behaviour. In these circumstances it is all too easy for good people to drift until they either act badly or become complicit in the bad deeds of others. History is full of examples of individuals and societies who have lost their ethical bearings, only later to look back in horror at what has been done.

An ethical life is a life for the hopeful.

In nearly every case, the majority has made no active choice to take the wrong path. Instead, they have been led there in ignorance by a demagogue or have gone along unwillingly, having lost their capacity to resist to the pits of despair.

At its heart, ethics is about living an ‘examined life’. It is about resisting the temptation to act out of habit alone – even if those habits are virtuous. Although we inherit values and principles from our parents and other people important in our lives, a mature person becomes capable of making these values and principles their own. Their lives will be more than a mere imitation of others. It is only by moving beyond inherited values and moral codes that we can genuinely take responsibility for our own lives.

From a practical point of view, the first step is to establish a conscious, personal inventory of values and principles. You do this by asking “what things are good at their core and worth choosing above other things?” and “what are the right ways to obtain those things?”

An ethical life is a life for the hopeful, a way of living that strengthens the sinews of all those affected by the political project embodied by President Trump. Political bluster can be every bit as dangerous as cyclonic winds. Let’s strengthen the ground on which we meet it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 ethical life hacks

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JAN 2017

It’s not all tough decisions – walking, sleeping and reading are some ways you can seamlessly strengthen your ethical muscles every day. Here are some activities that can help refine your ethics while you’re busy in your day-to-day life.

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to heightened positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, as Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand that other people’s mental states are different from our own, which is a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drunk driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ that weakens our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics from the couch: 5 shows to binge on

Ethics from the couch: 5 shows to binge on

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 4 JAN 2017

Study! Relax!

¿Por qué no los dos?

In the spirit of the Old El Paso school of philosophy, here are five TV shows you can binge watch that will also get you thinking a little about ethics. Quick warning: there are some minor spoilers below.

1. UnREAL

We’re not going to suggest you go back and watch The Bachelor or Survivor Australia (you probably watched them the first time around). Check out UnREAL instead. It’s a fictional look at the thorny ethics of reality TV based around the producers of Everlasting, which is The Bachelor in pretty much everything but name.

<

It’s easy to watch reality TV and assume the people appearing on the shows are fair game for criticism because they signed up to appear on the program. What’s easily forgotten – until you watch UnREAL – is the manipulation undertaken by producers to create drama and ‘good’ television. In season 1, a contestant kills herself as a result of this kind of manipulation, which only sparks higher ratings.

2. Offspring

If you’ve never watched Offspring, you’ve got a lot to catch up on. The feel-good Aussie sitcom was rebooted for a fifth season in 2016 and brought with it a thorny bioethics conundrum: who has the right to a dead man’s sperm?

Offspring centres around Nina Proudman and her family, and also deals with the fallout from the sudden death of Patrick, Nina’s fiancé and father of her daughter. Unknown to Nina, Patrick had some of his sperm frozen during a previous marriage. His ex-wife decides to offer Nina his sperm, in case she would like to have another child to him.

Does Nina have any right to use Patrick’s sperm? Does his ex-wife have any right to offer it to Nina? Patrick donated before he was in a relationship with Nina and we have no idea what his wishes would be for children in the event of his death. How can we respect his wishes in this case?

3. Black Mirror

This isn’t the first time we’ve discussed Black Mirror: Patrick Stokes explored the themes of one episode in his piece on digital death. Black Mirror doesn’t follow a season-long narrative. It’s a bunch of standalone dramas exploring themes around technology, the future and humanity. It can be pretty dystopian but does encourage us to think twice about where today’s technology might be headed.

One episode that hits close to home is “Hated in the Nation”, which has a detective who investigates the deaths of young people subjected to online shaming and social media pile ons. Just because we don’t see the consequences of a mean tweet or aggressive comment, it doesn’t mean we’re not responsible for them.

4. The Good Place

One for the philosopher nerds among us! When Eleanor Shellstrop is killed by a trailer advertising erectile dysfunction drugs, she finds herself in the afterlife. Everything is perfect except Eleanor herself. It turns out the hard-drinking, foul-mouthed woman was meant to go to “the bad place” but a clerical error worked in her favour.

Eleanor enlists the help of her allocated ‘soul mate’ Chidi, who was an ethics professor on earth. He proceeds to help her to reform, teaching her about Kant, Aristotle and the rest. The show basically functions as an introduction to moral philosophy for both Eleanor and viewers, but manages to sneak in a few decent jokes along the way.

5. Cleverman

Mythology and traditional stories have always been good fodder for film and television, so it’s a little surprising Aboriginal stories have been so absent from Australian screens. Ryan Griffen was aware of this absence and wanted to create an Aboriginal superhero for his son. The end product was Cleverman, a dystopian sci-fi series about the Hairypeople – an Indigenous race who live for hundreds of years, have extraordinary strength and grow thick pelts across their body.

The “Hairies” are seen as subhuman, rounded up and kept in a separate part of society called the Zone. The spiritual leader of the Zone is the Cleverman, whose powers include bringing people back from the dead. Cleverman follows a range of narratives around the internal politics of the Zone and the broader social structures that continue to oppress Hairypeople.

What’s important about Cleverman is both its representation, putting Aboriginal faces at the centre of a world based in Dreamtime stories, and the ability – like all sci-fi – to take pressing social issues and explore them in a fictional world.

Questions around Aboriginal identity in the broader Australian community, social attitudes to ‘otherness’, black deaths at the hands of white police officers and the militarisation of government departments are all explored.

You are more than your job

You are more than your job

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 20 DEC 2016

There are many ways we define our personal identity. Often, we define it by the roles we play in life.

We might think of ourselves as a child, parent, sibling, spouse, lover, friend… It is remarkable how we integrate all these different roles and relationships into our own, singular person.

People may often identify themselves according to their work. It’s been happening throughout history, as we can hear in occupational surnames such as Carpenter, Carter, Baker and Wheeler. We even link our identity with what we do for bureaucratic reasons. For example, every traveller is required to state their occupation when departing from or arriving in Australia.

Personal value has shifted focus from our character, personality, and relationships, to our role or place in society. It is no longer a question of who we are but what we do.

Casual conversations, too, eventually veer towards the question, “what do you do?” But a few years ago, I noticed the response to the question “How are you?” was changing from “I’m well” to “I’m busy”. I wondered what lay behind this altered response. What were they trying to say?

I concluded that the words “I am busy” are a proxy for “I am valued/needed”. My worth is affirmed by the fact I am in demand to the point of being busy.

If I’m correct, this marks a subtle but important change. Personal value has problematically shifted focus from our character, personality and relationships to our role or place in society. It is no longer a question of who we are but what we do.

Perhaps we should reflect on some of the deeper questions to do with identity, meaning and value.

For the most part, we might not notice this change in emphasis. However, if what I suspect is true, a holiday such as the enforced Christmas vacation could be a period of stress and dislocation for people who define themselves by their work – especially if they live alone and are without family or friends.

For some people, a job is not only a source of identity, it may also be their principal social environment, providing a regular opportunity for human contact. For such people, being deprived of this context can be a profound loss. To be ‘on leave’ is to be cut off from their principal source of identity.

Those of us with established social networks could help by reaching out to such people and making sure they’re included in holiday celebrations. Among other things, this sends a signal that the person is valued for more than their work.

Work-focused individuals could also volunteer with charities during the holiday season. This would provide a readymade social context and a valuable, alternative source of meaning and identity.

However, especially at Christmas time, perhaps we should reflect on some of the deeper questions dealing with identity, meaning and value. At the heart of ethics is a belief in the intrinsic worth of every person – irrespective of their gender, race, religion, sexuality… or job.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The etiquette of gift giving

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Ruth Quibell The Ethics Centre 14 DEC 2016

I enjoy giving gifts, especially for my children. It’s an opportunity to think about them, who they are now and how they’re developing.

I want the gift I choose to be liked by the person who receives it but I also expect it to do other things. Does this gift tell them they are understood? Loved? Appreciated? Does it reflect our relationship? It’s a bit of a gamble and is easy to get wrong, which is why I’m often a little freer with spending my money and time on a gift than I am usually.

This deeply personal way of thinking about gifts isn’t unusual but it overlooks the shared, ritualised aspects of gift exchange. In childhood we learn a polite dance of expectation and obligation. Even though gift-giving is meant to be spontaneous and honest, it follows a predictable script of performed generosity and gratitude.

In Brooklyn Nine-Nine, the dramatic Gina offers a great example of this. She secretly opens all her presents in advance so she can rehearse her ‘opening’ expressions for later.

A gift might be given freely and without coercion, but it doesn’t come without basic obligations for the receiver of the gift: to accept the gift, to express gratitude, to reciprocate. While a gift might express or help reinforce a relationship, the giver’s intention alone is no guarantee of success.

‘Charity gifts’ like providing clean water for a community overseas are undoubtedly well motivated, but do they serve the same purpose as traditional gift giving?

The rise of ‘charity gifts’ interrupts our usual expectations of a gift as an exchange between two people or families that is motivated by a relationship. Interestingly, by donating money to a charity in another’s name the ordinary social expectations of giving are preserved. The relationship between giver and the nominal recipient of the gift might even be bolstered without any tangible exchange occurring between them.

The ultimate recipient of the gift might benefit from it but they are receiving anonymous charity rather than a gift. You might even argue that they are part of the gift being given. For those considering ‘charity gifts’, it’s worth asking: what are you giving, to who, and why?

You’re unwrapping a present, surrounded by family when you unveil the most garish, knitted socks from great Aunty Mavis. Do you have to keep them? Are you obliged to wear them?

This situation makes the tacit expectations around how to receive gifts more overt. We don’t know much about great Aunty Mavis’s motivations. She might have simply enjoyed knitting the socks and have little interest in our feelings about them. The situation requires what sociologist David Ekerdt calls an “act of reception”. Without it, Mavis’s gift giving gesture will hang in the air like an unshaken hand.

A common response, I suspect, to avoid an uncomfortable situation would be to graciously accept the gift without giving offence, and then to quietly dispose of it later. Think Colin Firth’s character wearing the Christmas themed jumper in Bridget Jones.

Of course, there’s a choice here. I’d probably put the socks on immediately and see what I could discover about them and myself, but I wouldn’t pretend to like them if I didn’t.

Children are often encouraged to write ‘Christmas lists’ and send them to Santa. Later in life, lots of people are explicit in the gifts they want to receive for Christmas or birthdays. Do these trends encourage us to think about gift giving in a different way?

As I write this, my almost eight year old has stuck a sizeable birthday list on the fridge. She wants these things but she also wants me to understand her. Her list is an attempt to ensure I don’t get her wrong. The list is important, but as her parent I don’t only want to give her the things she wants. This is where gifts differ from simply an exchange of money for goods in the market. Gifts entail risky choices and unpredictable receptions.

It feels as though there’s a tension between the act of giving a gift itself, which is an act of generosity, and the general climate of the season, which seems more self-interested. Is that tension inescapable?

Gift giving usually has a dose of both. We give because we want to, but also because we expect something in return. Even if we don’t expect the straightforward exchange of a gift in return, we might hope for a stronger relationship, to be held high in someone’s opinion, or simply to be appreciated as kind, thoughtful or generous.

To be clear, this is not the same variety of self-interest as the stereotypical selfish consumer always hungry for more. It’s self-interest, yet I don’t think there’s anything particularly wrong in wanting our lives to be good with caring relationships. Perhaps when it comes to choosing a gift, we don’t need to be so quick to disown having a pinch or two of self-interest in the gift-giving game. It might even lead to a better choice of gift than great Aunty Mavis’s socks.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

BY Ruth Quibell

Ruth Quibell is a sociologist based in Melbourne. Her most recent book is The Promise of Things.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

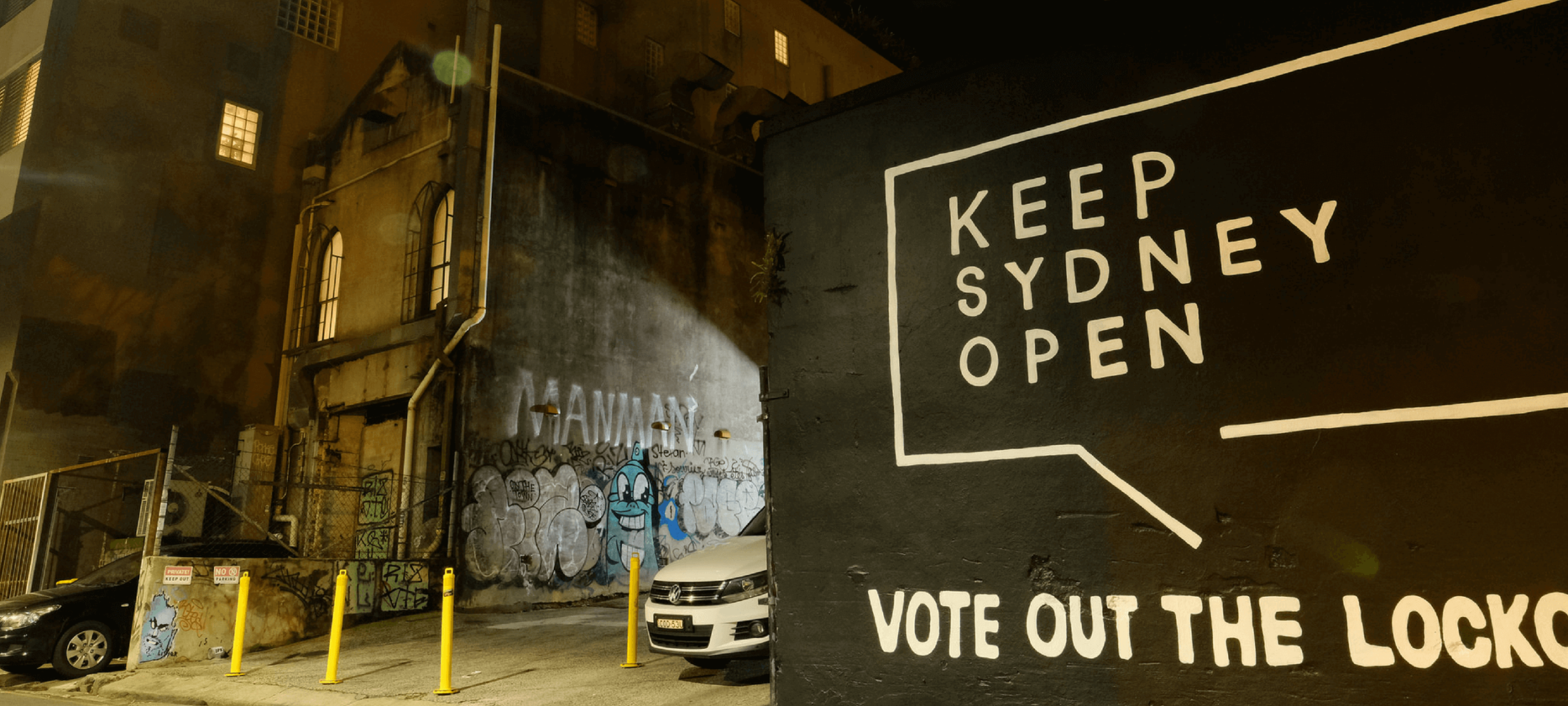

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Jack Hume The Ethics Centre 8 DEC 2016

The New South Wales lockout laws were introduced in early 2014 in the wake of a great tragedy – the loss of human life to alcohol-fuelled violence.

Following the recommendations of an independent inquiry by Ian Callinan QC in 2016, the government decided to soften them. It shows that when we legislate in the wake of a tragedy, our judgement can be reactive. In the future, let’s measure our reactions against evidence.

When lockout laws were introduced in Sydney, alcohol related violence was on a downward trend. Even if people were afraid of becoming victims of violence, they were actually less likely to be attacked than in the past.

There is something to be learned from reflecting on the climate in which these laws were passed. We should be thinking about risks in terms of their likelihood, not in terms of how much we fear them. But that’s very hard, as we can see with another example – shark attacks.

People overestimate the likelihood of a shark attack in the same way they do other events they seriously fear, like terrorism and natural disasters. A study on Australian perception of sharks found that Sydneysiders believe shark attacks occur twice as often as they actually do, and fatal ones four times as often.

“Exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe they occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.”

This isn’t surprising. Research tells us we believe things are more likely to occur if we can easily call to mind examples of when they’ve occurred. And disturbing examples are easier to recall. The process of judging the probability of an event by how easy we find it to think of examples is known as the availability heuristic.

Emotional information is easier to remember, and so the availability heuristic has an interesting relationship with news coverage. Emotional news content prompts our attention, invariably placing demands on further coverage, which we will remember more easily.

News media is highly responsive to issues its audiences are interested in, and as a result those issues get more coverage. This pulls people into a feedback loop whereby their demands for further coverage lead them to believe events are more probable than they really are.

“Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line.”

For example, exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe crimes occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.

Knowing all this, we should expect people to overestimate the probability of events that provoke fear – violence, terrorism, plane crashes and natural disasters – particularly while they’re fresh in our memory. This effect is seen not just in how we speak and think about probability, but in how we act to protect ourselves, which brings us back to NSW policy.

Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line. Lockout laws are said to have been bad for Sydney’s culture and night-time economy. The public backlash forced the review that recommended loosening the reins of the lockout laws.

“Once news providers and their audience are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.”

The point is not whether lockout laws are effective in decreasing the threat of violence (which they have been in Sydney CBD), but the conditions through which they came about. These included media coverage on disturbing and unusual events – in particular, ‘one-punch’ killings – which caused fear and demanded attention, plus a campaign to increase awareness.

When the media reports on disturbing and unusual events at the same time that campaigns are run to increase awareness for them, the basic ingredients for a feedback between news media and its audiences are met. Once news providers and their audiences are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.

Shark nets are installed with the expectation of reducing the risk of shark attacks but they do this at the expense of marine life. They come as a response to the fact Australia has an above average incidence of shark attacks, which appear to be increasing. But let’s put this in perspective – the risk posed by sharks is still extremely low, accounting for two deaths in 2016 and one death in 2017.

The availability heuristic has unconscious components. Usually, people aren’t aware they’re estimating probability based on their fallible and selective memory. When people are unaware of how emotions, personal experiences and exposure to similar events can affect their judgements, they make unconsciously biased decisions.

Without appropriate consideration, people are at risk of basing important decisions on forces they aren’t consciously aware of. They may be led to support invasive or expensive regulations to protect themselves from risks that are highly unlikely. Where these regulations have undesirable side effects, like marine animal deaths, cultural damages to nightlife or the closure of businesses, this can mean real consequences for unreal problems.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

BY Jack Hume

Jack studied Philosophy and Psychology at the University of Sydney, completing his Bachelor of Arts in 2017 with First Class Honours. He has supported The Ethics Centre's Advice & Education team in research capacities over the last two years, contributing to their work on cognitive bias in decision making, and ethics education in financial services. In 2018, he joined the Centre full-time as a Graduate Consultant. He brings insights from contemporary political philosophy, moral psychology and skills in qualitative research to consulting projects across a variety of sectors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2016

We all like to believe we’re careful thinkers who gather and evaluate facts before making a decision. Unfortunately, we’re not.

We tend to seek information we find favourable and which supports what we already think. In short, we reach a conclusion first, then test it against evidence, rather than gather evidence first and evaluate it to make a conclusion.

This is called confirmation bias, which is a type of cognitive bias (like the bandwagon effect, or the availability heuristic) in which we tend to notice or search out information that confirms what we already believe or would like to believe. To avoid the discomfort of finding information that doesn’t support our views or ideas, we will discount or disregard evidence that’s contrary to our beliefs or preferences.

This plays out in similar ways across a range of contexts. In the sciences, theories are developed through falsifying and supporting evidence. Researchers need to recognise their own potential confirmation biases that come with holding a strong view or belief in the face of other evidence.

Confirmation bias plays out both in a range of research disciplines and our everyday decision making. When we research brands or products we tend to seek out information that reinforces our tastes and preferences. For instance, being drawn to reviews favouring brands we already like.

Confirmation bias is also at play in more significant life decisions like superannuation and other investment choices. Often, the greater the significance of a decision, the greater the likelihood that confirmation bias will be in play. If we don’t want to be left behind when we hear friends or colleagues talking about how well an investment is doing, our research will be strongly influenced by the story of our friend’s success. In doing so, we may filter out information that raises red flags and instead focus on the information validating the investment.

Our technology comes full with confirmation bias. Social media news feeds and online sources are ready made filters of information from people who think like us. Paradoxically, the tools and technologies that make information so accessible heighten the likelihood of us being drawn into information loops which reinforce what we think we know. As Warren Buffett famously remarked, “What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact”.

Like several other biases, confirmation biases are an example of ‘motivated reasoning’. Motivated reasoning describes how our judgments are consciously and unconsciously influenced by what we think we know. This shapes how we think about our health, our relationships, how we decide how to vote and what we consider fair or ethical.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2016

‘Ask Me, Tell Me’ is a series created by you. You told us what you want to talk about by contributing your thoughts to an interactive artwork at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

This week: what happens to sex when people can’t trust each other? We look at the ethics and politics of sex.

Sexual ethics is prickly business. For the sake of exploring your contribution dear FODI patron, let’s assume you’re a man who has been lied to by a now pregnant woman who said she couldn’t conceive because she was using contraception.

Speaking of assumptions, it’s easy to assume our personal experiences are common, particularly big, life-changing ones like this. Experience is after all the key learning module in the school of life. But an assessment of the world based on our own experiences or one-off things we see, no matter how prominently they feature in our lives, is not exactly objective (although it’s a common cognitive bias we all can slip into).

Seeing ‘women’ as a group who lie to get pregnant isn’t a fair assessment of all women. Like every other group in society that shares some sort of common ground, women don’t think the same way or collectively decide what’s ethical and what’s not.

Also, there’s not much evidence to support this being a common practice of women other than a poll by That’s Life! magazine.

Nevertheless, none of this is to deny what we’re assuming has happened to you. It’s just pointing out it’s unlikely to be a prevalent phenomenon.

…men could choose to have no legal rights or responsibilities to a child as a way of correcting the alleged power imbalance in which men are held accountable as parents even if they would have preferred a pregnancy be terminated.

Whether or not it’s common for women to fib about using contraception to get pregnant doesn’t change the extent to which you must feel betrayed, trapped, angry and lied to. You’re facing the prospect of a lifelong commitment you believed wasn’t on the cards. Can anything be done about it?

There are a couple of ways to prevent others from finding themselves in the same situation. A Swedish group recently campaigned to give men the right to ‘legally abort’ from children. Under the proposal, men could choose to have no legal rights or responsibilities to a child as a way of correcting an alleged power imbalance that holds men accountable as dads even if they never wanted to be one.

‘Legal abortions’ don’t seem to actually be legal anywhere in the world but the argument in favour of them is that they level the playing field. Many of course would see women as the ones bearing more of the challenges of unwanted pregnancies than men, given they’re the ones who have to carry and give birth to the child.

Nevertheless, ‘legal abortions’ is an idea several thinkers, often women, have been discussing for a while.

Sex is risky – not only because of the possibility of children or infection – but because it leaves us physically and emotionally vulnerable.

An easier option would be for men to take contraception into their own hands. Condoms have been available for a long time. They’re 98% effective, prevent sexually transmitted infections and tend to be cheaper than female methods. And in years to come, a male contraceptive pill may well be available – a promising trial study of a male pill was abandoned due to side effects.

However, trust has become an issue here as well, with some women not having faith in men to take care of contraception. The Guardian columnist Barbara Ellen describes this as “the relentless howl of distrust between the sexes, echoing down the years”. Perhaps the best solution is one in which both men and women use contraception.

In many ways, this is a neat solution but can we really use technology as a substitute for sexual trust? Or, if men and women are doomed to distrust one another as Ellen suggests, what are the consequences of sex without trust? We trust sexual partners to use protection and contraception. We trust them to be concerned for our pleasure as well as theirs, to recognise our boundaries and seek our consent before doing anything to us or demanding anything from us, to respect our privacy and so on. At the heart of all of this is the understanding that sex is risky – not only because of the possibility of babies and infection – but because it leaves us physically and emotionally vulnerable.

Philosopher LA Paul describes becoming a parent as a ‘transformative experience’ – an experience that changes who we are so fundamentally it’s impossible to know whether the person we will become will regret our decision or not.

None of this gives you, FODI punter, much to go on with. You’ve been lied to, you’re facing long term consequences as a result and now you have to choose what kind of parent you want to be. And because you were lied to you’ve been put in this position unjustly and against your will, which is wrong by almost any measure.

Unfortunately, you still have to decide what to do. Philosopher LA Paul describes becoming a parent as a ‘transformative experience’ – an experience that changes who we are so fundamentally it’s impossible to know whether the person we will become will regret our decision or not. By definition, we can’t know what the right thing to do is.

Paul thinks this is true for all parents, not just those facing unwanted pregnancies. Even though there’s not much guidance on what you should do in this situation, it might be reassuring to know every potential parent is facing the same impossible decision. In the end, Paul suggests the best way to make this decision is to base it on what we want to discover, not what we think we’d enjoy.

And if you’re still stuck, you can always contact Ethi-call – The Ethics Centre’s free helpline – where you can speak with one of our counsellors to help make a decision aligned with your own values, principles and conscience.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The road back to the rust belt

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Glover The Ethics Centre 24 NOV 2016

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell observed that it was far easier for a Bishop to relate to a tramp than to a solid member of the working class.

The poverty of the former was wholly obvious, and one could easily enter into his world by tramping with him and offering him a bowl of soup, but entering into the homes and culture of the latter was almost impossible.

In Australia today we might put it differently: it’s often easier for an educated ‘progressive’ to relate to a refugee or an Indigenous person or an LGBTI person than to someone in a Housing Commission suburb.

This is understandable and even laudable. After all, it’s the mark of a civilised community to treat others – even those least like us – with respect and to prioritise those whose needs are the most obvious and urgent. This way of thinking has become increasingly central to our liberal culture.

For example, I have before me a scholarship guide (really an advertising supplement) for some of the nation’s wealthiest private schools. In it you will find scholarships specifically targeted at diverse categories of people whose moral call on us is obvious, but none targeted at children from the old factory suburbs with high unemployment. The closest we get are vague references to help for ‘the children of families who require financial assistance’, which could mean just about anything.

Without noticing it, and often with the very best of intentions, we have stopped thinking and talking about the working class. When I recently wrote a book about one of our most neglected former Housing Commission suburbs, I was surprised at the consternation – even offense – it generated, particularly on the Left. Has it become so unusual to discuss such things? The shock of recent overseas events for such discussion has made this blindspot obvious and acceptable.

Without noticing it, and often with the very best of intentions, we have stopped thinking and talking about the working class.

This seems to me somewhat extraordinary given there are now numerous suburbs in Australia where the unemployment rate has been at 20, 21, 22 and even 33.6 percent for a decade or more. That we have been able to almost completely ignore this level of economic injustice for so long tells us something about how much our way of thinking has changed, amounting almost to a moral blindness. The coming closure of car factories and coal fired power plants across Victoria and South Australia will only make this worse, creating our own versions of America’s rust belt.

These days, it seems, one can be a self-identifying ‘progressive’ without giving much thought at all to what’s happening to the workers and the unemployed. The implication is they represent our economic past, and are therefore not wholly worthy of serious thought. Scratch a socially-progressive economist and you may well find someone who thinks saving manufacturing jobs to be a doubtful investment – perhaps it’s better for the general good such people and places be allowed to quietly disappear. The problem, as Britain and America shows, is they don’t disappear. They collapse in on themselves and get angry.

The way the culture wars have poisoned our political debates means this sort of thing isn’t easy to say without opening oneself up to some charge of illiberalism, so let me be clear: we should treat refugees more humanely, keep aggressively closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and keep expanding the circle of rights to include new categories of difference, but we must also talk about what’s happening to the old working class. We can do all these things simultaneously but at the moment we are not.

Every day this ignoring of the old working class becomes a bigger problem for our democracy. As Brexit and Donald Trump’s victory demonstrate, in an economy that is restructuring, populists will eagerly pounce and turn the sense of neglect felt by ‘the forgotten’ into envy and resentment. The resuscitation of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party shows it may be happening here too. We need to advance on a broader front.

If you want to know why Australia is currently having a debate about Section 18C of the Race Discrimination Act, it’s partly because those who seek to exploit this envy and resentment need to remove laws which restrain the full expression of these negative emotions. The attacks on 18C and the fate of the old working class are ultimately connected.

Some argue the Left’s response must be to abandon what is commonly dismissed as ‘the rights agenda’ and take a more populist stand. This is wrong. The Left, which has traditionally been both liberal and social-democratic, shouldn’t downplay its liberalism but, rather, give new life to the social-democratic half of its equation, which it has been neglecting for too long. This doesn’t mean looking backwards. It means thinking through how our older industrial communities can be revived to take advantage of economic restructuring – instead of treating their interests as an irritating afterthought.

What form this modernised social-democracy will take is as yet to be determined but one thing is clear: it has to start with a moral effort to know what’s going on in the lives of people in the places where we stopped looking a generation ago, and it needs to be followed by a public policy effort that matches the scale of the problem.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture