Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 3 MAR 2022

The invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in the early hours of 24 February 2022 came as a violent shock to most onlookers.

Even after the visible buildup of Russian forces and weeks of sabre rattling by Russian President Vladimir Putin, the images of rockets striking apartment blocks and tanks rolling through city streets triggered an outpouring of support for Ukraine from people within Australia and around the world.

But those who dwell on social media might have seen some voices express a different perspective: that the focus on Ukraine is suggestive of a darker underlying bias on behalf of the onlookers; that the conflict has only gained so much attention because the victims of the war are white Europeans.

The argument suggests that if the victims were non-white, such as those involved in the ongoing wars in Yemen, Syria or Ethiopia, then the media and Western onlookers would be far less engaged.

So is it wrong to focus our attention acutely on the war in Ukraine while investing less energy on conflicts in other parts of the world, especially if those conflicts affect non-white people? Is it OK to care more about a war in Europe than it is a war in Africa or the Middle East?

We can unpack the argument in a few different ways. The least charitable interpretation is that it’s an accusation of racism, suggesting that people who care about the war in Ukraine only care because the victims are white. That might be true for some onlookers, but it’s highly doubtful that this applies to the majority of people.

Rather, there are many reasons why someone in Australia might place great significance on the events unfolding in Ukraine. First of all is the shock factor, particularly given the relative stability and lack of open wars between nations in Europe since the end of the Second World War. This means the war in Ukraine is not just a concern for that region but is of tremendous global significance, with the potential to reshape the geopolitical landscape in a way that could affect people around the world. In this way, the war in Ukraine very much qualifies as being worthy of our attention due to its historical significance.

There’s also the matter of familiarity, in the sense that Ukraine is a modern, industrialised and democratic nation that shares many political and moral values with countries like Australia. Beyond the human toll, the invasion represents an attack against values that most Australians cherish.

Many Australians also have friends, family or coworkers with connections to Ukraine or other European countries who are impacted by the war. To them, the war is not just news of distant events but is felt in their immediate circles in a way that other conflicts might not be. Of course, there are many Austrlians who are also affected by conflicts in other parts of the world, such as in Syria and Yemen.

Finally, on a more mundane level, the war in Ukraine is likely to have a material impact on our lives through its destabilisation of the international economy, as well as on commodity prices such as wheat and oil, in a way that most other ongoing conflicts don’t.

All this said, while the above can help explain why someone might take a more acute interest in the war in Ukraine, it doesn’t answer the ethical question of whether they should take greater interest in conflicts elsewhere at the same time. It’s possible that these explanations don’t justify an undue focus on one population experiencing conflict rather than another.

A more charitable interpretation of the argument is that all suffering deserves our attention, all violence deserves our rebuke and all people involved in wars deserve our empathy. This stems from a universalist ethic, such as that promoted by philosophers like Peter Singer. It argues that all people deserve equal concern, no matter their background, ethnicity or nationality. Singer famously argued that if you’d dive into a pond to save a drowning child, even at the cost of muddying your clothes and being late to work, then you ought to be willing to incur a similar cost to save the life of a dying child on the other side of the world.

From this perspective, the same reasons that justify our empathy towards the suffering of the Ukrainian people should similarly apply to the people of Yemen, Ethiopia, Syria and elsewhere.

However, a truly universalist ethic is difficult, if not impossible, to fully achieve in practice. Few people would be willing to take the ethic to the extreme, and treat strangers in distant countries with as much care and concern that they reserve for our family. If this is so, then it is difficult to know where to draw the line around who deserves more or less of our concern.

Furthermore, everybody has a finite budget of time, emotional energy and power to act. It is not possible to be engaged with every conflict, every injustice and every instance of ethical wrongdoing taking place in the world, let alone to be able to act on them. It might be reasonable for people to choose where to invest their limited energy, or to preserve their energy for causes they can positively impact. That doesn’t mean they don’t care about other issues, only that they’ve chosen to do good where they can.

Which brings us to the most charitable interpretation of the argument, which is that any conflict should remind us of the horrors of war, and should motivate us to extend our empathy to people who are suffering anywhere in the world. The saturation media footage of violence and destruction in Ukraine can help us better understand the plight of people living through other conflicts. The plight of embattled civilians in Kyiv can help us better understand and empathise with people living in Aleppo in Syria or Sanaa in Yemen.

It is unlikely that those promoting this argument on social media would want people to retreat from engaging with all news of conflict or suffering, whether it is in Europe or elsewhere. Rather, we might forgive people for having some bias in where they choose to direct their attention, while reminding them that all people are deserving of ethical consideration. Moral consideration need not be a zero-sum game; elevating our concern for one population doesn’t have to come at the expense of concern for others.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ukraine hacktivism

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 MAR 2022

As reported by David Crowe in the Sydney Morning Herald, Ukraine’s Foreign Minister, Dmytro Kuleba, has recently called on individuals, from other countries, to join the fight against Russia’s invasion.

“Foreigners willing to defend Ukraine and world order as part of the International Legion of Territorial Defence of Ukraine, I invite you to contact foreign diplomatic missions of Ukraine”, he said on Sunday night.

It is important to note that it is illegal for Australians to take up this call. As things stand, Australians commit a criminal office if they fight for any formation other than properly constituted national armed forces. This prohibition was introduced to deter and punish Australians hoping to fight in the ranks of ISIS. However, it applies far more generally. As such, it proscribes an age-old practice of individuals engaging in warfare in support of causes they wish to champion. Unlike mercenaries (who will fight for whichever side will pay them the better price), there have been people, throughout history, willing to risk their lives and limbs for idealistic reasons.

More recent examples include those who joined the International Brigade to fight Fascist forces in Spain during the early part of the Twentieth Century, those who joined the Kurds to oppose ISIS, in recent years, and also those who fought with and for ISIS in order to establish a Caliphate in the Middle East.

It should be noted that the choices mentioned above are not morally equivalent – even though the underlying motivation is, essentially, the same. Those who opposed Fascism in the 1930s did not employ terrorism as a principal tactic. ISIS did – unrestrained by any of the ethical limitations arising out of the Just war tradition.

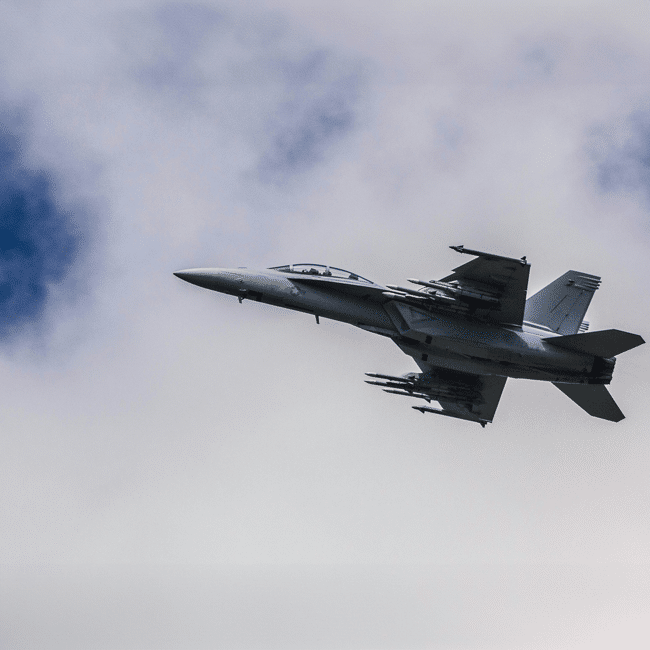

That tradition was developed to deal with forms of war which took place in real time and across real battlespaces where combatants and non-combatants could be killed by a direct encounter with a lethal weapon or its effects.

In recent days, this discussion has taken on a new character as volunteer ‘hacktivists’ have taken up virtual arms, on Ukraine’s behalf, in a cyber-war against Russian forces. Once again, there are non-Ukrainian nationals engaged in a conflict that pits them against an aggressor – not for financial reward, not for reasons of self-preservation but simply because they feel compelled to defend an ideal. Of course, there are bound to be some amongst their ranks who are just in it for the mischief. However, I think most will be sincere in their conviction that they are doing some good.

That said, there is some truth to the old adage that ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions’. It is not enough to be realising a noble purpose. One also needs to employ legitimate means. It is this thought that lies behind the observation, by Canadian philosopher Michael Ignatieff, that the difference between a ‘warrior’ and a ‘barbarian’ lies in ethical restraint.

In an ideal world, those who belong to the profession of arms are trained to apply ethical restraint in their use of force. The allegations levelled against a few members of the SAS, in Afghanistan, indicate that there can be a gap between the ideal and the actual. However, in the vast majority of cases, Australia’s professional shoulders serve as ‘warriors’ rather than ‘barbarians’.

But what of the ethical restraint required of volunteer cyber-warriors? There are some general observations, as outlined by Dr Matt Beard and I in our publication Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology. Our first principle is that ‘CAN does NOT imply OUGHT’. That is, the mere fact that you can do something does not mean that you should!. However, I think that some of the traditional ethical restraints derived from ‘just war theory’ should also apply.

There are three principles of particular importance. First, you need to be satisfied that you are pursuing a just cause. Self-defence and the defence of others who have been attacked without just cause have always been allowed – with one proviso … your own use of force must be directed at securing a peace that is superior to that which would have prevailed if no force had been used.

That accounts for the ends that one might pursue. When it comes to the means, they need to accord with the principles of ‘discrimination’ and proportionality’. The first says that you may only attack a legitimate target (a combatant, military infrastructure, etc.). The second requires you only to use the minimal amount of force needed to achieve one’s legitimate ends.

President Putin’s forces have violated all three principles of just war. He has invaded another nation without just cause. He is targeting non-combatants (innocent women and children) and he is employing weaponry (and threatening an escalation) that is entirely disproportionate.

The fact that he does so does not justify others to do the same.

Volunteer cyber-warriors have to be extremely careful that in their zeal to harm Putin and his armed forces, they do not deliberately (or even inadvertently) harm innocent Russians who have been sucked into one man’s war.

Of course, this means fighting with the equivalent of ‘one arm tied behind the back’. The temptation is to fight ‘fire with fire’ – but that only leads to the loss of one of one’s ‘moral authority’. The hard lessons of history have taught us that this is a potent weapon in itself.

The law might not prevent a cyber-warrior from fighting on the side of Ukraine from a desk somewhere in Australia. However, one should at least pause to consider the ethical dimension of what you propose to do and how you propose to go about it.

There can be honour in being a cyber-warrior. There is none in being a cyber-barbarian.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Reports

Science + Technology

Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 28 FEB 2022

Euphoria has been, for almost two years now, approaching a fever pitch of horror, addiction, heartbreak and self-destruction.

Its assembled cast of characters – most notably Rue (Zendaya), who starts the first season emerging straight out of rehab – sit constantly on the verge of total nervous collapse. They are always one bad party away from cataclysmic suffering, their lives hanging in a painful balance between “just about getting by” and “absolute devastation.”

Indeed, even if its utter melodrama means that Euphoria doesn’t actually reflect how high school is – who could cram in that much explosive melancholy before the lunch bell? – it certainly reflects how high school feels. There are few experiences more tortured and heightened than being a teenager, when your whole skin feels on fire, and possibilities splinter out from in front of your feet at every single moment. There is the sense of the future being unwritten; of your life being terrifyingly in your own hands.

But what does Euphoria’s constant hysteria do to its viewers, particularly its younger ones? If the devastation of adolescence really is that severe, then are artists failing, somehow, if they merely reflect that devastation? Should we ask our art to serve an instructional purpose; to pull us out of the traps we have built for ourselves? Or should art settle into those traps, letting their metal teeth sink into their skin?

Image: Euphoria, HBO

The Long History Of “Evil” Art

The question of the moral responsbility of artists is particularly pertinent in the case of Euphoria because of its emphasis on what have been typically viewed as “illicit” activities, from drug-taking to underage sex. These are – to the great detriment of a truly free society – taboo subjects, deemed inappropriate for discussion in public spaces, and condemned to be whispered, rather than shouted about.

Indeed, there is a long history of conservatives and moral puritans rallying against artworks that they feel ‘glamorize’ or somehow indulge bad and illegal behaviour. Take, for instance, the Satanic Panic that gripped the United Kingdom in the ‘80s. Shortly after the advent of home video, the market became flooded with what were then termed “video nasties”, a wave of cheaply made horror films that actively marketed themselves for their moral repugnance. The point was how many taboos could be broken; into how much blood and muck and horror that filmmakers could sink themselves, like half-formed and discarded babies being thrown to rest in a mud puddle.

This, to many pro-censorship thinkers at the time, was seen as a kind of moral crime – an unspeakable act, with the ability to influence and addle the minds of Britain’s younger generation. The demand from conservatives was that art be a way of modelling good ethical behaviour, and the worry, expressed furiously in the tabloids, was that any other alternative would lead to the breakdown of society itself.

So no, the question as to whether art should be instructional is not new; the fear that it might lead the minds of the younger generation astray far from fresh. Euphoria might seem relentlessly modern, with its lived-in cinematic voice, and its restless politics. But it is part of a tradition of artworks that submerge themselves in darkness and despair; vice and what some, most of them on the right, deem the immoral.

The Unspoken Becomes Spoken

The mistake made, however, by those who imagine such art is failing an explicit moral purpose, a kind of sentimental education, rests on an outdated and functionally useless understanding of morality. These critics imagine that there is just one way to live well. They believe in uncrossable boundaries of taboo and immorality; that there are iron-wrought moral rules, and that any art that breaks those rules will lead to some kind of negative and harmful shifting of what is acceptable amongst the citizens of any democratic society.

But why should we believe that morality is so strict? We would do well to move away from an objective, centralised view of morality, where there exists a list of rules, printed in indelible ink somewhere, that are inflexible and pre-ordained. Societally, as well as personally, change is the only constant. If we abide by a set of constructed ethical principles that do not reflect that change, we will be forever torn between a possible future and a weighty past, bogged down in a system of conduct that no longer represents the complexity of what it means to be human.

If we have any true moral imperative, it is to constantly be in the process of testing and re-shaping our morals. It was John Stuart Mill who developed a similar concept of truth – who believed that we could only remain honest, and democratic, if we were forever challenging that which we had taken for granted. Art is a process of this moral re-shaping. Great art need not shy away from that which we hold to be “good” or “right”, or, on the flipside, “harmful” and “taboo.”

It is not that art need to be amoral, free from ethical concerns, with artists resisting any urge to provide some form of moral instruction – it is that we need to let go of the idea that this moral instruction can only take the form of propping up old and unchanging notions of goodness. The immoral and the moral are only useful concepts if they teach us something about how to live, and they will only teach us something about how to live if we make sure they are forever being tested and examined.

Finding Yourself

Image: Euphoria, HBO

This is what Euphoria does. By basking in that which has been taken as illicit – in particular, the sex and chemical lives of America’s teenagers – the show makes the unspoken spoken. It draws into focus an outdated and ancient view of the good life, and challenges us to stare our conceptions of self-perpetuation and self-destruction in the face.

Rue, forever in the process of re-shaping herself in the shadow of her great addiction, makes mistakes. Cassie (Sydney Sweeney), Euphoria’s shaking, panic-addled heart, makes even more. Both of them stray from pre-written social conceptions of the “good girl”, dissolving an ancient and harmful angel/whore dichotomy, and proving that there are no static boundaries between what is admirable and what is abhorrent.

Just as the show itself skirts back and forth across the line between our notions of the ethical and the immoral, so too do these characters forever find themselves testing the limits of what is good for them, and those around them. They are flawed, vulnerable people. But in these flaws – in this very notion of trembling possibility, the rules of good conduct forever being written in sand – they do provide us with a moral education. Not one that rests on simplistic notions of what we should do, and when. But one that proves that as both a society, and as individuals in that society, we should always be taking that which has been shrouded in darkness and throw it – sometimes painfully – into the light.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Joseph Earp 22 FEB 2022

Dr. Chris Letheby, a pioneer in the philosophy of psychedelics, is looking at a chair. He is taking in its individuated properties – its colour, its shape, its location – and all the while, his brain is binding these properties together, making them parts of a collective whole.

This, Letheby explains, is also how we process the self. We know that there are a number of distinct properties that make us who we are: the sensation of being in our bodies, the ability to call to mind our memories or to follow our own trains of thought. But there is a kind of mental glue that holds these sensations together, a steadfast, mostly uncontested belief in the concrete entity to which we refer when we use the word “me.”

“Binding is a theoretical term,” Letheby explains. “It refers to the integration of representational parts into representational wholes. We have all these disparate representations of parts of our bodies and who we were at different points at time and different roles we occupy and different personality traits. And there’s a very high-level process that binds all of these into a unified representation; that makes us believe these are all properties and attributes of one single thing. And different things can be bound to this self model more tightly.”

Freed from the Self

So what happens when these properties become unbound from one another – when we lose a cohesive sense of who we are? This, after all, is the sensation that many experience when taking psychedelic drugs. The “narrative self” – the belief that we are an individuated entity that persists through time – dissolves. We can find ourselves at one with the universe, deeply connected to those around us.

Perhaps this sounds vaguely terrifying – a kind of loss. But as Letheby points out, this “ego dissolution” can have extraordinary therapeutic results in those who suffer from addiction, or experience deep anxiety and depression.

“People can get very harmful, unhealthy, negative forms of self-representation that become very rigidly and deeply entrenched,” Letheby explains.

“This is very clear in addiction. People very often have all sorts of shame and negative views of themselves. And they find it very often impossible to imagine or to really believe that things could be different. They can’t vividly imagine a possible life, a possible future in which they’re not engaging in whatever the addictive behaviours are. It becomes totally bound in the way they are. It’s not experienced as a belief, it’s experienced as reality itself.”

This, Letheby and his collaborator Philip Gerrans write, is key to the ways in which psychedelics can improve our lives. “Psychedelics unbind the self model,” he says. “They decrease the brain’s confidence in a belief like, ‘I am an alcoholic’ or ‘I am a smoker’. And so for the first time in perhaps a very long time [addicts] are able to not just intellectually consider, but to emotionally and experientially imagine a world in which they are not an alcoholic. Or if we think about anxiety and depression, a world in which there is hope and promise.”

A comforting delusion?

Letheby’s work falls into a naturalistic framework: he defers to our best science to make sense of the world around us. This is an unusual position, given some philosophers have described psychedelic experiences as being at direct odds with naturalism. After all, a lot of people who trip experience what have been called “metaphysical hallucinations”: false beliefs about the “actual nature” of the universe that fly in the face of what science gives us reason to believe.

For critics of the psychedelic experience then, these psychedelic hallucinations can be described as little more than comforting falsehoods, foisted upon the sick – whether mentally or physically – and dying. They aren’t revelations. They are tricks of the mind, and their epistemic value remains under question.

But Letheby disagrees. He adopts the notion of “epistemic innocence” from the work of philosopher Lisa Bortolotti, the belief that some falsehoods can actually make us better epistemic agents. “Even if you are a naturalist or a materialist, psychedelic states aren’t as epistemically bad as they have been made out to be,” he says, simply. “Sometimes they do result in false beliefs or unjustified beliefs … But even when psychedelic experiences do lead to people to false beliefs, if they have therapeutic or psychological benefits, they’re likely to have epistemic benefits too.”

To make this argument, Letheby returns again to the archetype of the anxious or depressed person. This individual, when suffering from their illness, commonly retreats from the world, talking less to their friends and family, and thus harming their own epistemic faculties – if you don’t engage with anyone, you can’t be told that you are wrong, can’t be given reasons for updating your beliefs, can’t search out new experiences.

“If psychedelic states are lifting people out of their anxiety, their depression, their addiction and allowing people to be in a better mode of functioning, then my thought is, that’s going to have significant epistemic benefits,” Letheby says. “It’s going to enable people to engage with the world more, be curious, expose their ideas to scrutiny. You can have a cognition that might be somewhat inaccurate, but can have therapeutic benefits, practical benefits, that in turn lead to epistemic benefits.”

As Letheby has repeatedly noted in his work, the study of the psychiatric benefits of psychedelics is in its early phases, but the future looks promising. More and more people are experiencing these hallucinations – these new, critical beliefs that unbind the self – and more and more people are getting well. There is, it seems, a possible world where many of us are freed from the rigid notions of who we are and what we want, unlocked from the cage of the self, and walking, for the first time in a long time, in the open air.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 FEB 2022

Ethics is about engaging in conversations to understand different perspectives and ways in which we can approach the world.

Which means we need a range of people participating in the conversation.

That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Dr Tim Dean as our Senior Philosopher. An award-winning philosopher, writer, speaker and honorary associate with the University of Sydney, Tim has developed and delivered philosophy and emotional intelligence workshops for schools and businesses across Australia and the Asia Pacific, including Meriden and St Mark’s high schools, The School of Life, Small Giants and businesses including Facebook, Commonwealth Bank, Aesop, Merivale and Clayton Utz.

We sat down with Tim to discuss his views on morality, social media, cancel culture and what ethics means to him.

What drew you to the study of philosophy?

Children are natural philosophers, constantly asking “why?” about everything around them. I just never grew out of that tendency, much to the chagrin of my parents and friends. So when I arrived at university, I discovered that philosophy was my natural habitat, furnishing me with tools to ask “why?” better, and revealing the staggering array of answers that other thinkers have offered throughout the ages. It has also helped me to identify a sense of meaning and purpose that drives my work.

What made you pursue the intersection of science and philosophy?

I see science and philosophy as continuous. They are both toolkits for understanding the world around us. In fact, technically, science is a sub-branch of philosophy (even if many scientists might bristle at that idea) that specialises in questions that are able to be investigated using empirical tools, hence its original name of “natural philosophy”. I have been drawn to science as much as philosophy throughout my life, and ended up working as a science writer and editor for over 10 years. And my study of biology and evolution transformed my understanding of morality, which was the subject of my PhD thesis.

How does social media skew our perception of morals?

If you wanted to create a technology that gave a distorted perception of the world, that encouraged bad faith discourse and that promoted friction rather than understanding, you’d be hard pressed to do better than inventing social media. Social media taps into our natural tendencies to create and defend our social identity, it triggers our natural outrage response by feeding us an endless stream of horrific events, it rewards us with greater engagement when we go on the offensive while preventing us from engaging with others in a nuanced way. In short, it pushes our moral buttons, but not in a constructive way. So even though social media can do good, such as by raising awareness of previously marginalised voices and issues, overall I’d call it a net negative for humanity’s moral development.

How do you think the pandemic has changed the way we think about ethics?

The COVID-19 pandemic has both expanded and shrunk our world. On the one hand, lockdowns and border closures have grounded us in our homes and our local communities, which in many cases has been a positive thing, as people get to know their neighbours and look out for each other. But it has also expanded our world as we’ve been stuck behind screens watching a global tragedy unfold, often without any real power to fix it. But it has also made us more sensitive to how our individual actions affect our entire community, and has caused us to think about our obligations to others. In that sense, it has brought ethics to the fore.

Tell us a little about your latest book ‘How We Became Human, And Why We Need to Change’?

I’ve long been fascinated by the story of how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today. Morality has played a key part in that story, helping us to have empathy for others, motivating us to punish wrongdoing and giving us a toolkit of moral norms that can guide our community’s behaviour. But in studying this story of moral evolution, I came to realise that many of the moral tendencies we have and many of the moral rules we’ve inherited were designed in a different time, and they often cause more harm than good in today’s world. My book explores several modern problems, like racism, sexism, religious intolerance and political tribalism, and shows how they are all, in part, products of our evolved nature. I also argue that we need to update our moral toolkit if we want to live and thrive in a modern, globalised and diverse world, and that means letting go of past solutions and inventing new ones.

How do you think the concepts of right and wrong will change in the coming years?

The world is changing faster than ever before. It’s also more diverse and fragmented than ever before. This means that the moral rules that we live by and the values that drive us are also changing faster than ever before – often faster than many people can keep up. Moral change will only continue, especially as new generations challenge the assumptions and discard the moral baggage of past generations. We should expect that many things we took for granted will be challenged in the coming decades. I foresee a huge challenge in bringing people along with moral change rather than leaving them behind.

What are your thoughts on the notion of ‘cancel culture’?

There are no easy answers when it comes to the limits of free speech. We value free speech to the degree that it allows us to engage with new ideas, seek the truth and to be able to express ourselves and hear from others. But that speech comes at a cost, particularly when it allows bad faith speech to spread misinformation, to muddy the truth, or dehumanise others. There are some types of speech that ought to be shut down, but we must be careful how the power to shut down speech is used. In the same way that some speech can be in bad faith, so too can be efforts to shut it down. Some instances of “cancelling” might be warranted, but many are a symptom of mob culture that seeks to silence views the mob opposes rather than prevent bad kinds of speech. Sometimes it’s motivated by a sense that a speaker is not just mistaken but morally corrupt, which prevents people from engaging with them and attempting to change their views. This is why one thing I advocate strongly for is rebuilding social capital, or the trust and respect that enables good faith discourse to occur at all. It’s only when we have that trust and respect that we will be able to engage in good faith rather than feel like we need to resort to cancelling or silencing people.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Ethics is what makes our species unique. No other creature can live alongside and cooperate with other individuals on the scale that we do. This is all made possible by ethics, which is our ability to consider how we ought to behave towards others and what rules we should live by. It’s our superpower, it’s what has enabled our species to spread across the globe. But understanding and engaging with ethics, figuring out our obligations to others, and adapting our sense of right and wrong to a changing world, is our greatest and most enduring challenge as a species.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Stopping domestic violence means rethinking masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

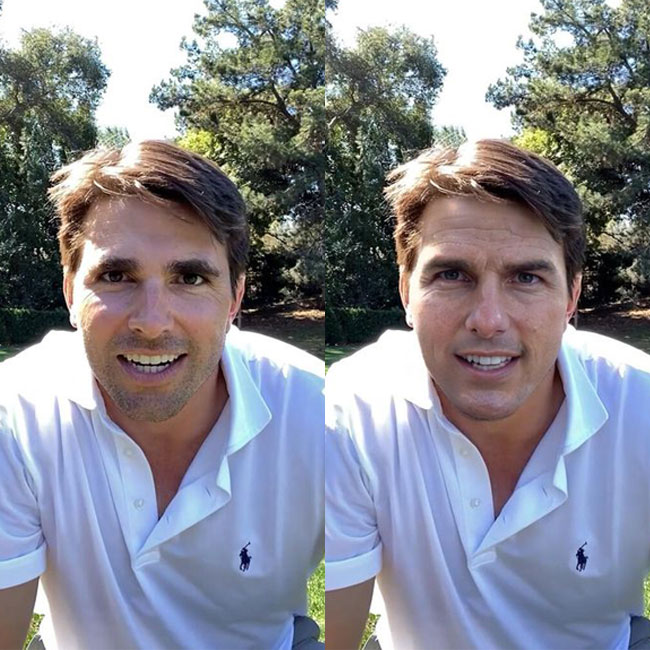

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Mehhma Malhi 18 FEB 2022

The use of deepfake technology is increasing as more companies devise different models.

It is a form of technology where a user can upload an image and synthetically augment a video of a real person or create a picture of a fake person. Many people have raised concerns about the harmful possibilities of these technologies. Yet, the notion of deception that is at the core of this technology is not entirely new. History is filled with examples of fraud, identity theft, and counterfeit artworks, all of which are based on imitation or assuming a person’s likeliness.

In 1846, the oldest gallery in the US, The Knoedler, opened its doors. By supplying art to some of the most famous galleries and collectors worldwide, it gained recognition as a trusted source of expensive artwork – such as Rothko’s and Pollock’s. However, unlike many other galleries, The Knoedler allowed citizens to purchase the art pieces on display. Shockingly, in 2009, Ann Freedman, who had been appointed as the gallery director a decade prior, was famously prosecuted for knowingly selling fake artworks. After several buyers sought authentication and valuation of their purchases for insurance purposes, the forgeries came to light. The scandal was sensational, not only because of the sheer number of artworks involved in the deception that lasted years but also because millions of dollars were scammed from New York’s elite.

The grandiose art foundation of NYC fell as the gallery lost its credibility and eventually shut down. Despite being exact replicas and almost indistinguishable, the understanding of the artist and the meaning of the artworks were lost due to the lack of emotion and originality. As a result, all the artworks lost sentimental and monetary value.

Yet, this betrayal is not as immoral as stealing someone’s identity or engaging in fraud by forging someone’s signature. Unlike artwork, when someone’s identity is stolen, the person who has taken the identity has the power to define how the other person is perceived. For example, catfishing online allows a person to misrepresent not only themselves but also the person’s identity that they are using to catfish with. This is because they ascribe specific values and activities to a person’s being and change how they are represented online.

Similarly, deepfakes allow people to create entirely fictional personas or take the likeness of a person and distort how they represent themselves online. Online self-representations are already augmented to some degree by the person. For instance, most individuals on Instagram present a highly curated version of themselves that is tailored specifically to garner attention and draw particular opinions.

But, when that persona is out of the person’s control, it can spur rumours that become embedded as fact due to the nature of the internet. An example is that of celebrity tabloids. Celebrities’ love lives are continually speculated about, and often these rumours are spread and cemented until the celebrity comes out themselves to deny the claims. Even then, the story has, to some degree, impacted their reputation as those tabloids will not be removed from the internet.

The importance of a person maintaining control of their online image is paramount as it ensures their autonomy and ability to consent. When deepfakes are created of an existing person, it takes control of those tenets.

Before delving further into the ethical concerns, understanding how this technology is developed may shed light on some of the issues that arise from such a technology.

The technology is derived from deep learning, a type of artificial intelligence based on neural networks. Deep neural network technologies are often composed of layers based on input/output features. It is created using two sets of algorithms known as the generator and discriminator. The former creates fake content, and the latter must determine the authenticity of the materials. Each time it is correct, it feeds information back to the generator to improve the system. In short, if it determines whether the image is real correctly, the input receives a greater weighting. Together this process is known as generative adversarial network (GAN). It uses the process to recognise patterns which can then be compiled to make fake images.

With this type of model, if the discriminator is overly sensitive, it will provide no feedback to the generator to develop improvements. If the generator provides an image that is too realistic, the discriminator can get stuck in a loop. However, in addition to the technical difficulties, there are several serious ethical concerns that it gives rise to.

Firstly, there have been concerns regarding political safety and women’s safety. Deepfake technology has advanced to the extent that it can create multiple photos compiled into a video. At first, this seemed harmless as many early adopters began using this technology in 2019 to make videos of politicians and celebrities singing along to funny videos. However, this technology has also been used to create videos of politicians saying provocative things.

Unlike, photoshop and other editing apps that require a lot of skill or time to augment images, deepfake technology is much more straightforward as it is attuned to mimicking the person’s voice and actions. Coupling the precision of the technology to develop realistic images and the vast entity that we call the internet, these videos are at risk of entering echo chambers and epistemic bubbles where people may not know that these videos are fake. Therefore, one primary concern regarding deepfake videos is that they can be used to assert or consolidate dangerous thinking.

These tools could be used to edit photos or create videos that damage a person’s online reputation, and although they may be refuted or proved as not real, the images and effects will remain. Recently, countries such as the UK have been demanding the implementation of legislation that limits deepfake technology and violence against women. Specifically, there is a slew of apps that “nudify” any individual, and they have been used predominantly against women. All that is required of users is to upload an image of a person. One version of this website gained over 35 million hits over a few days. The use of deepfake in this manner creates non-consensual pornography that can be used to manipulate women. Because of this, the UK has called for stronger criminal laws for harassment and assault. As people’s main image continues to merge with technology, the importance of regulating these types of technology is paramount to protect individuals. Parameters are increasingly pertinent as people’s reality merges with the virtual world.

However, like with any piece of technology, there are also positive uses. For example, Deepfake technology can be used in medicine and education systems by creating learning tools and can also be used as an accessibility feature within technology. In particular, the technology can recreate persons in history and can be used in gaming and the arts. In more detail, the technology can be used to render fake patients whose data can be used in research. This protects patient information and autonomy while still providing researchers with relevant data. Further, deepfake tech has been used in marketing to help small businesses promote their products by partnering them with celebrities.

Deepfake technology was used by academics but popularised by online forums. Not used to benefit people initially, it was first used to visualise how certain celebrities would look in compromising positions. The actual benefits derived from deepfake technology were only conceptualised by different tech groups after the basis for the technology had been developed.

The conception of such technology often comes to fruition due to a developer’s will and, given the lack of regulation, is often implemented online.

While there are extensive benefits to such technology, there need to be stricter regulations, and people who abuse the scope of technology ought to be held accountable. As we see our present reality merge with virtual spaces, a person’s online presence will continue to grow in importance. Stronger regulations must be put into place to protect people’s online persona.

While users should be held accountable for manipulating and stripping away the autonomy of individuals by using their likeness, more specifically, developers must be held responsible for using their knowledge to develop an app using deepfake technology that actively harms.

To avoid a fallout like Knoedler, where distrust, skepticism, and hesitancy rooted itself in the art community, we must alert individuals when deepfake technology is employed; even in cases where the use is positive, be transparent that it has been used. Some websites teach users how to differentiate between real and fake, and some that process images to determine their validity.

Overall, this technology can help individuals gain agency; however, it can also limit another persons’ right to autonomy and privacy. This type of AI brings unique awareness to the need for balance in technology.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

The great resignation: Why quitting isn't a dirty word

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Jack Derwin 17 FEB 2022

More than 47 million Americans quit their jobs last year, a new record for the United States. While it is most obvious in North America, a form of ‘The Great Resignation’ phenomenon is showing up in Australia as well.

Recent surveys suggest that almost one in two Australian workers are currently looking to switch jobs, with more than one million people accepting new ones between September and November alone. That part matters, making the local trend more akin to a ‘Great Reshuffle’, in the words of Australia’s own Treasurer.

The fact is most people aren’t throwing off the shackles of capitalism and running from the workforce altogether. Rather an astounding number are simply searching for something better – and fast.

Workers are motivated to leave

The pandemic has understandably taken a toll. Exhausted frontline and public-facing workers have operated under heavy stress for two years. If they haven’t been locked down or quarantined then they have faced the genuine risk of contracting the virus. It’s no wonder then that the highest number of resignations have come from healthcare with retail not far behind. Meanwhile sectors like the arts have been quietly decimated.

Professionals fortunate enough to work from home have faced a different set of challenges, whether losing contact with colleagues or having the lines between their professional and personal lives blur.

Whether the pandemic led to burnout or gave workers time to reflect and reconsider their choices, much has changed since 2020. Whether they are fed up with the old or energised to start something new, the result is the same. They’re ready to move on.

It’s the economy, stupid

That’s not to say we lived in some kind of capitalist utopia before March 2020. Indeed since 2013, wages in Australia haven’t meaningfully grown across industries, placing increasing pressure on workers over the last decade to either demand or find their own pay rises.

Yet the record economic stimulus unleashed during the pandemic is changing that dynamic. Almost $300 billion in government spending helped expand the economy while JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments have kept households either in work or able to live without it.

Such was the level of support during the pandemic that overall Australians are actually, on average, better off now than they were before it to the point where we are collectively sitting on $260 billion in savings right now.

Meanwhile job openings are 45% higher now than they were pre-pandemic and unemployment has plummeted to its lowest level since 2008. Before that you’d have to go back to the 1970s to find anything comparable. Simply put, Australian workers are in hot demand at the same time they are in short supply.

This is an environment in which, for the first time in recent memory, workers have genuine bargaining power in their current role as well as when negotiating for their next one. As the recovery remains uneven, there’s certainly an incentive to jump from one industry to another with mid-career professionals currently the most likely to switch careers entirely.

But whether it’s asking for a raise, finding a new job or taking time out altogether, this period has largely been a coup for employees.

Don’t let guilt boss you around

Rather than celebrating or exploiting this new power dynamic, many feel uneasy however at the thought of demanding more, let alone quitting their job.

Economically speaking, this makes no sense. Resignations aren’t a sign of fickleness. Workers that can freely pursue their interests and abilities in a more productive way are instead part of a healthy and efficient economy.

‘The Great Reshuffle’ can be seen as much a consequence of an economy that wasn’t previously functioning as it is the emergence of meaningful choice for a workforce that has been long without it.

Yet despite these sound economic and personal rationales, there remains a stigma attached to separating from our workplaces and going our own way. The idea of quitting can conjure up feelings of guilt, failure and even betrayal despite what we may stand to gain from it.

This is perhaps inevitable. Our jobs absorb eight or more hours a day, or more time than most people spend with their loved ones. Whether or not we grumble about them, they are so embedded in our culture and language that we talk about our ‘work lives’ as if they were interchangeable with our ‘real lives’.

Then there is a certain dependence associated with work. Beyond simply a paycheck, a profession creates a sense of identity and purpose. Consider the refrain ‘I am a doctor/a hairdresser/a butcher’. We are our occupation, or, more specifically, we are our current job. Significantly, this desire for the personal value of work has only increased during the pandemic.

In combination these ties can bind. The responsibility of a role can naturally and subconsciously manifest as an unreasonable obligation to stay in one, no matter how uncomfortable, ill–suited or even toxic it may be.

All of these factors help to stoke a sense of loyalty that is impossible to ignore. The fact that our motivations for leaving are all our own, whether to pursue a raise, a promotion or some other desire, only amplifies this further as we inevitably place our own interests above those of our employer and colleagues.

As a consequence, a resignation can feel an awful lot like infidelity. Despite our acceptance into the tribe, it is ultimately our decision, and ours alone, to leave it behind.

Bite the bullet

Resignation however remains a valuable right and a vital avenue of self-empowerment and self-determination.

An autonomous individual has an obligation to themselves to pursue the opportunities that interest and suit them and to find work that is both fulfilling and sustainable, or to exit employment that is harmful or boring.

There is also nothing shameful about periods of unemployment should we demand or desire some time out of the workforce. There is fortunately a growing appreciation of our wellbeing as people beyond our status as workers.

Whereas once gaps in resumes may have been viewed as red flags for prospective employers, there is a deeper understanding of the challenges behind them, whether related to family obligations, mental and emotional health or the pursuit of study or other interests.

There are of course different ways to leave work.

How to quit ethically

First, reflect on what is driving your decision. Is it a boss that micromanages, substandard pay and conditions, an unfair workload or a lack of opportunities?

If it is a single issue in isolation, consider seriously whether there are any possible remedies. Sometimes a frank discussion with an employer or manager can drastically improve a situation but first they need to know what is wrong. Businesses, especially at the moment, are motivated to retain staff and often may simply be unaware of what they can do better.

If you’re certain that your employment has become untenable, then you can be comforted by the fact that there is no other solution and feel justified in your decision to depart.

To counter any ill feelings of guilt that may arise, we need to interrogate its source. Generally guilt is brought on by the knowledge that an action has or will harm someone else or be immoral. In the context of resigning, it’s helpful to zoom out and consider the real world ramifications.

This analysis should both appreciate the real benefits of leaving and recognise the often minor costs. For example, by changing roles you may be in a better position to find or accept fulfilling work, or a job that allows you the flexibility you need to lead a more contented life.

By leaving, your manager may have to recruit someone else to do your job. This may inconvenience them for a few hours but will the business collapse as a result? It’s highly unlikely. In fact, they may well find someone more fitting for the role. Resignations simply aren’t a zero-sum game.

Nor does your decision represent a moral transgression. We know that resignations are a natural feature of any workplace. Feelings to the contrary can be mitigated by instead focusing on resigning appropriately.

Again it’s helpful to articulate your reasons to yourself before sharing them with a manager. Plan out how you will do it rather than letting yourself crack under pressure. Practice how you might break the news to your workplace. Schedule a private meeting, talk through why you’re leaving respectfully and end on good terms.

If you’re worried about offending your boss, don’t be. It’s unhelpful and unnecessary to lie or deceive them in an attempt to mitigate guilt. Instead keep your head high. By voicing your concerns you may help improve the workplace for future staff on your way out.

Ultimately, if you’re ready to go then resigning is in everyone’s best interests. If your job isn’t working out for you, quit feeling conflicted and throw in the towel.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The case for reskilling your employees

BY Jack Derwin

Jack is a Sydney-based writer and journalist, specialising in business and economics. His reporting has appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Financial Review, Business Insider and the Asahi Shimbun among others.

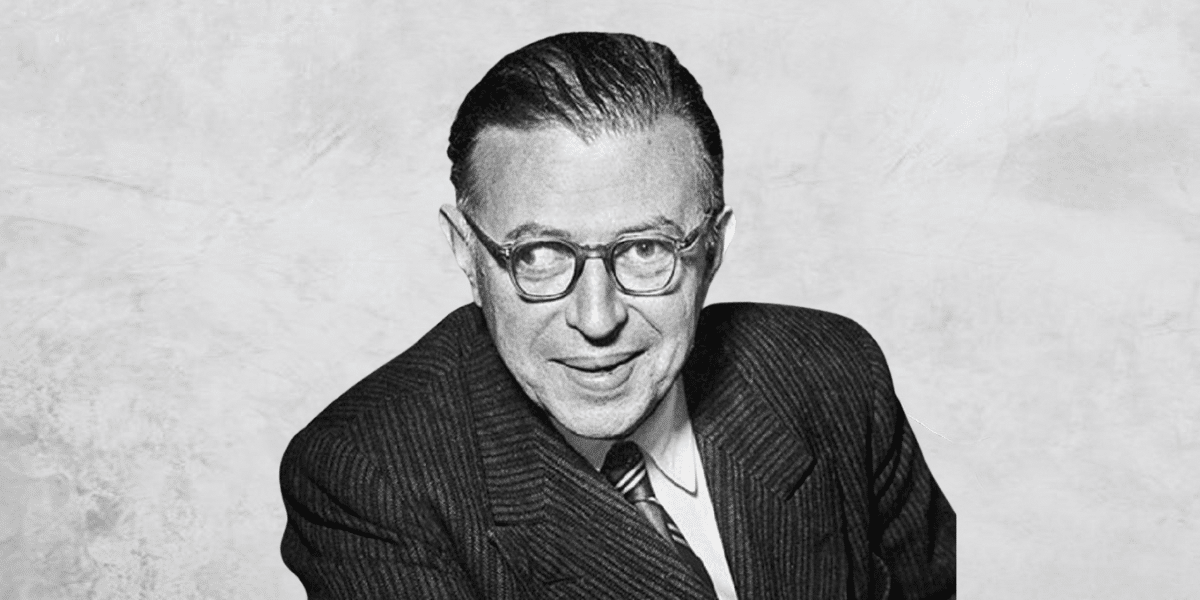

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) is one of the best known philosophers of the 20th century, and one of few who became a household name. But he wasn’t only a philosopher – he was also a provocative novelist, playwright and political activist.

Sartre was born in Paris in 1905, and lived in France throughout his entire life. He was conscripted during the war, but was spared the front line due to his exotropia, a condition that caused his right eye to wander. Instead, he served as a meteorologist, but was captured by German forces as they invaded France in 1940. He spent several months in a prisoner of war camp, making the most of the time by writing, and then returned to occupied Paris, where he remained throughout the war.

Before, during and after the war, he and his lifelong partner, the philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir, were frequent patrons of the coffee houses around Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. There, they and other leading thinkers of the time, like Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, cemented the cliché of bohemian thinkers smoking cigarettes and debating the nature of existence, freedom and oppression.

Sartre started writing his most popular philosophical work, Being and Nothingness, while still in captivity during the war, and published it in 1943. In it, he elaborated on one of his core themes: phenomenology, the study of experience and consciousness.

Learning from experience

Many philosophers who came before Sartre were sceptical about our ability to get to the truth about reality. Philosophers from Plato through to René Descartes and Immanuel Kant believed that appearances were deceiving, and what we experience of the world might not truly reflect the world as it really is. For this reason, these thinkers tended to dismiss our experience as being unreliable, and thus fairly uninteresting.

But Sartre disagreed. He built on the work of the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl to focus attention on experience itself. He argued that there was something “true” about our experience that is worthy of examination – something that tells us about how we interact with the world, how we find meaning and how we relate to other people.

The other branch of Sartre’s philosophy was existentialism, which looks at what it means to be beings that exist in the way we do. He said that we exist in two somewhat contradictory states at the same time.

First, we exist as objects in the world, just as any other object, like a tree or chair. He calls this our “facticity” – simply, the sum total of the facts about us.

The second way is as subjects. As conscious beings, we have the freedom and power to change what we are – to go beyond our facticity and become something else. He calls this our “transcendence,” as we’re capable of transcending our facticity.

However, these two states of being don’t sit easily with one another. It’s hard to think of ourselves as both objects and subjects at the same time, and when we do, it can be an unsettling experience. This experience creates a central scene in Sartre’s most famous novel, Nausea (1938).

Freedom and responsibility

But Sartre thought we could escape the nausea of existence. We do this by acknowledging our status as objects, but also embracing our freedom and working to transcend what we are by pursuing “projects.”

Sartre thought this was essential to making our lives meaningful because he believed there was no almighty creator that could tell us how we ought to live our lives. Rather, it’s up to us to decide how we should live, and who we should be.

“Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.”

This does place a tremendous burden on us, though. Sartre famously admitted that we’re “condemned to be free.” He wrote that “man” was “condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.”

This radical freedom also means we are responsible for our own behaviour, and ethics to Sartre amounted to behaving in a way that didn’t oppress the ability of others to express their freedom.

Later in life, Sartre became a vocal political activist, particularly railing against the structural forces that limited our freedom, such as capitalism, colonialism and racism. He embraced many of Marx’s ideas and promoted communism for a while, but eventually became disillusioned with communism and distanced himself from the movement.

He continued to reinforce the power and the freedom that we all have, particularly encouraging the oppressed to fight for their freedom.

By the end of his life in 1980, he was a household name not only for his insightful and witty novels and plays, but also for his existentialist phenomenology, which is not just an abstract philosophy, but a philosophy built for living.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Research shows that physical appearance can affect everything from the grades of students to the sentencing of convicted criminals – are looks and morality somehow related?

Ancient philosophers spoke of beauty as a supreme value, akin to goodness and truth. The word itself alluded to far more than aesthetic appeal, implying nobility and honour – it’s counterpart, ugliness, made all the more shameful in comparison.

From the writings of Plato to Heraclitus, beautiful things were argued to be vital links between finite humans and the infinite divine. Indeed, across various cultures and epochs, beauty was praised as a virtue in and of itself; to be beautiful was to be good and to be good was to be beautiful.

When people first began to ask, ‘what makes something (or someone) beautiful?’, they came up with some weird ideas – think Pythagorean triangles and golden ratios as opposed to pretty colours and chiselled abs. Such aesthetic ideals of order and harmony contrasted with the chaos of the time and are present throughout art history.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c.1490

These days, a more artificial understanding of beauty as a mere observable quality shared by supermodels and idyllic sunsets reigns supreme.

This is because the rise of modern science necessitated a reappraisal of many important philosophical concepts. Beauty lost relevance as a supreme value of moral significance in a time when empirical knowledge and reason triumphed over religion and emotion.

Yet, as the emergence of a unique branch of philosophy, aesthetics, revealed, many still wondered what made something beautiful to look at – even if, in the modern sense, beauty is only skin deep.

Beauty: in the eye of the beholder?

In the ancient and medieval era, it was widely understood that certain things were beautiful not because of how they were perceived, but rather because of an independent quality that appealed universally and was unequivocally good. According to thinkers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, this was determined by forces beyond human control and understanding.

Over time, this idea of beauty as entirely objective became demonstrably flawed. After all, if this truly were the case, then controversy wouldn’t exist over whether things are beautiful or not. For instance, to some, the Mona Lisa is a truly wonderful piece of art – to others, evidence that Da Vinci urgently needed an eye check.

Consequently, definitions of beauty that accounted for these differences in opinion began to gain credence. David Hume famously quipped that beauty “exists merely in the mind which contemplates”. To him and many others, the enjoyable experience associated with the consumption of beautiful things was derived from personal taste, making the concept inherently subjective.

This idea of beauty as a fundamentally pleasurable emotional response is perhaps the closest thing we have to a consensus among philosophers with otherwise divergent understandings of the concept.

Returning to the debate at hand: if beauty is not at least somewhat universal, then why do hundreds and thousands of people every year visit art galleries and cosmetic surgeons in pursuit of it? How can advertising companies sell us products on the premise that they will make us more beautiful if everyone has a different idea of what that looks like? Neither subjectivist nor objectivist accounts of the concept seem to adequately explain reality.

According to philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Francis Hutcheson, the answer must lie somewhere in the middle. Essentially, they argue that a mind that can distance itself from its own individual beliefs can also recognize if something is beautiful in a general, objective sense. Hume suggests that this seemingly universal standard of beauty arises when the tastes of multiple, credible experts align. And yet, whether or not this so-called beautiful thing evokes feelings of pleasure is ultimately contingent upon the subjective interpretation of the viewer themselves.

Looking good vs being good

If this seemingly endless debate has only reinforced your belief that beauty is a trivial concern, then you are not alone! During modernity and postmodernity, philosophers largely abandoned the concept in pursuit of more pressing matters – read: nuclear bombs and existential dread. Artists also expressed their disdain for beauty, perceived as a largely inaccessible relic of tired ways of thinking, through an expression of the anti-aesthetic.

Nevertheless, we should not dismiss the important role beauty plays in our day-to-day life. Whilst its association with morality has long been out of vogue among philosophers, this is not true of broader society. Psychological studies continually observe a ‘halo effect’ around beautiful people and things that see us interpret them in a more favourable light, leading them to be paid higher wages and receive better loans than their less attractive peers.

Social media makes it easy to feel that we are not good enough, particularly when it comes to looks. Perhaps uncoincidentally, we are, on average, increasing our relative spending on cosmetics, clothing, and other beauty-related goods and services.

Turning to philosophy may help us avoid getting caught in a hamster wheel of constant comparison. From a classical perspective, the best way to achieve beauty is to be a good person. Or maybe you side with the subjectivists, who tell us that being beautiful is meaningless anyway. Irrespective, beauty is complicated, ever-important, and wonderful – so long as we do not let it unfairly cloud our judgements.

Step through the mirror and examine what makes someone (or something) beautiful and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for the Ethics of Beauty on Thur 29 Feb 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why morality must evolve

If you read the news or spend any time on social media, then you’d be forgiven for thinking that there’s a lack of morality in the world today.

There is certainly no shortage of serious social and moral problems in the world. People are discriminated against just because of the colour of their skin. Many women don’t feel safe in their own home or workplace. Over 450 million children around the world lack access to clean water. There are whole industries that cause untold suffering to animals. New technologies like artificial intelligence are being used to create autonomous weapons that might slip from our control. And people receive death threats simply for expressing themselves online.

It’s easy to think that if only morality featured more heavily in people’s thinking, then the world would be a better place. But I’m not convinced. This might sound strange coming from a moral philosopher, but I have come to believe that the problem we face isn’t a lack of morality, it’s that there’s often too much. Specifically, too much moral certainty.

The most dangerous people in the world are not those with weak moral views – they are those who have unwavering moral convictions. They are the ones who see the world in black and white, as if they are in a war between good and evil. They are ones who are willing to kill or die to bring about their vision of utopia.

That said, I’m not quite ready to give up on morality yet. It sits at the heart of ethics and guides how we decide on what is good and bad. It’s still central to how we live our lives. But it also has a dark side, particularly in its power to inspire rigid black and white thinking. And it’s not just the extremists who think this way. We are all susceptible to it.

To show you what I mean, let me ask you what will hopefully be an easy question:

Is it wrong to murder someone, just because you don’t like the look of their face?

I’m hoping you will say it is wrong, and I’m going to agree with you, but when we look at what we mean when we respond this way, it can help us understand how we think about right and wrong.

When we say that something like this is wrong, we’re usually not just stating a personal preference, like “I simply prefer not to murder people, but I don’t mind if you do so”. Typically, we’re saying that murder for such petty reasons is wrong for everyone, always.

Statements like these seem to be different from expressions of subjective opinion, like whether I prefer chocolate to strawberry ice cream. It seems like there’s something objective about the fact that it’s wrong to murder someone because you don’t like the look of their face. And if someone suggests that it’s just a subjective opinion – that allowing murder is a matter of personal taste – then we’re inclined to say that they’re just plain wrong. Should they defend their position, we might even be tempted to say they’re not only mistaken about some basic moral truth, but that they’re somehow morally corrupt because they cannot appreciate that truth.

Murdering someone because you don’t like the look of their face is just wrong. It’s black and white.

This view might be intuitively appealing, and it might be emotionally satisfying to feel as if we have moral truth on our side, but it has two fatal flaws. First, morality is not black and white, as I’ll explain below. Second, it stifles our ability to engage with views other than our own, which we are bound to do in a large and diverse world.

So instead of solutions, we get more conflict: left versus right, science versus anti-vaxxers, abortion versus a right to choose, free speech versus cancel culture. The list goes on.

Now, more than ever, we need to get away from this black and white thinking so we can engage with a complex moral landscape, and be flexible enough to adapt our moral views to solve the very real problems we face today.

The thing is, it’s not easy to change the way we think about morality. It turns out that it’s in our very nature to think about it in black and white terms.

As a philosopher, I’ve been fascinated by the story of where morality came from, and how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today.

Evolution plays a leading role in this story. It didn’t just shape our bodies, like giving us opposable thumbs and an upright stance. It also shaped our minds: it made us smarter, it gave us language, and it gave us psychological and social tools to help us live and cooperate together relatively peacefully. We evolved a greater capacity to feel empathy for others, to want to punish wrongdoers, and to create and follow behavioural rules that are set by our community. In short: we evolved to be moral creatures, and this is what has enabled our species to work together and spread to every corner of the globe.

But evolution often takes shortcuts. It often only makes things ‘good enough’ rather than optimising them. I mentioned we evolved an upright stance, but even that was not without cost. Just ask anyone over the age of 40 years about their knees or lower backs.

Evolution’s ‘good enough’ solution for how to make us be nice to each other tens of thousands of years ago was to appropriate the way we evolved to perceive the world. For example, when you look at a ripe strawberry, what do you see? I’m guessing that for most of you – namely if you are not colour blind – you see it as being red. And when you bite into it, what do you taste? I’m guessing that you experience it as being sweet.

However, this is just a trick that our mind plays on us. There really is no ‘redness’ or ‘sweetness’ built into the strawberry. A strawberry is just a bunch of chemicals arranged in a particular way. It is our eyes and our taste buds that interpret these chemicals as ‘red’ or ‘sweet’. And it is our minds that trick us into believing these are properties of the strawberry rather than something that came from us.

The Scottish philosopher David Hume called this “projectivism”, because we project our subjective experience onto the world, mistaking it for being an objective feature of the world.

We do this in all sorts of contexts, not just with morality. This can help explain why we sometimes mistake our subjective opinions for being objective facts. Consider debates you may have had around the merits of a particular artist or musician, or that vexed question of whether pineapple belongs on pizza. It can feel like someone who hates your favourite musician is failing to appreciate some inherently good property of their music. But, at the end of the day, we will probably acknowledge that our music tastes are subjective, and it’s us who are projecting the property of “awesomeness” onto the sounds of our favourite song.

It’s not that different with morality. As the American psychologist, Joshua Greene, puts it: “we see the world in moral colours”. We absorb the moral values of our community when we are young, and we internalise them to the point where we see the world through their lens.

As with colours, we project our sense of right and wrong onto the world so that it looks like it was there all along, and this makes it difficult for us to imagine that other people might see the world differently.