The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 16 MAR 2020

It was at the last Festival of Dangerous Ideas in November 2018, that our keynote speaker – celebrated writer, actor and bon vivant Stephen Fry – made the prophetic statement, “It’s not dangerous ideas that should concern us, it’s dangerous realities.”

We liked the line so much we used it as the theme for our tenth festival, scheduled to take place at Sydney Town Hall on 3-5 April. But as of today, we’re devastated to advise that the Festival won’t be happening. Like thousands of other events, ours may no longer proceed following the NSW Government’s (Minister of Health) ban of non-essential gatherings of 500 people or more.

Faced with the rapidly evolving situation around COVID-19 and relying on the best available medical advice, this is a possibility we’ve been grappling with, and agonising over, for the last two weeks – until the point where the choice was taken from our hands.

Although this decision is an incredible blow, the health of our audience, staff, speakers, artists and the wider public, is what matters most.

For some ticket holders, this cancellation will probably come as a relief. There’s already a high level of anxiety in the community about attending events of any kind. In the greater scheme of things, missing a couple of festival sessions – or a night at the theatre – is no more than a minor inconvenience. It might also be experienced as a reprieve for the speakers who were booked to travel halfway around the world to attend the Festival; navigating travel bans and the risk of illness, flight delays or mandatory quarantine periods to do so.

FODI takes many months – and thousands of hours – of creativity and painstaking human effort to become reality. If you had attended the festival, you would have heard from over 50 speakers, including exiled activist Edward Snowden (no stranger to self-isolation), climate change journalist, David Wallace-Wells, the celebrated Harvard professor, Michael Sandel, and technology critic, Evgeny Morozov. You would have heard Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton was to talk about her experience in one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in Australian history. And you would have encountered the extraordinary contrarian, Roxane Gay.

Beyond talks – and in the realm of the arts – you could have engaged with a remarkable new work called Unforgivable, featuring youth activists and a young 18-person strong indigenous choir. There was also going to be an opportunity for anyone to interact with PIG – a giant transparent piggybank into which people could donate (or withdraw) money in the full glare of public scrutiny. PIG was to have sat outside the QVB in the heart of Sydney for an entire week, prompting conversation about generosity and the hierarchy of human needs. It’s a conversation that has taken on a new relevance, today.

Major events like ours operate on a financial knife-edge. Just breaking even is a challenge in the best of times. So, the cancellation of FODI is not only heart-breaking. It also risks being financially crippling. Given this, we are asking our supporters, sponsors and ticket holders to consider donating their contributions to The Ethics Centre. Every cent will help us survive this financial upheaval and carry on our work.

If you would like to support The Ethics Centre, you can do so here.

Personally, our team is dealing with a deep sense of disappointment – that something we’ve been working towards for a long time, is now never going to happen.

That said, although we are down, we are definitely not out! FODI will be back – its tenth anniversary merely postponed until better times. It’s the original festival for stroppy people who want to push the boundaries. And it remains the best!

We thank all of our speakers, staff, supporters and ticket holders for their patience and understanding.

This dangerous reality arrived ahead of schedule.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 13 MAR 2020

In the sixteenth century, a cool thing to do if you were a political philosopher was to contrast human beings in society, with human beings as they would be if there were no society.

This thought experiment, performed by Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan, paints a pretty bleak picture of humanity. Hobbes described his picture of the “state of nature” – a world without society as:

“A time of war, where every man is enemy to every man… there is no place for industry… no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

This bleak picture of humanity – a time where people would clash and war over their own interests, with no hope for co-operation or camaraderie – is precisely why Hobbes thought we needed the state.

Nobody wants to live in the state of nature; it sucks. Instead, we all hand over a portion of our power to the state, who then create a world where everyone can get by and, ideally, flourish.

And, as a bonus, with a state to run the show, we can start to think about things like justice, ethics and morality. In the state of nature, Hobbes surmised these wouldn’t exist. He writes:

“The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law, where no law, no injustice. Force, and fraud, are in war the cardinal virtues.”

I can’t help but think of Hobbes at the moment, as I wander through supermarkets empty of supplies. I imagine the swollen pantries, garages and bathrooms across Australia, stockpiled in preparation for a pandemic that threatens us all. Individuals are scrambling for resources, squirrelling away supplies and taking care of their own interests first. It sounds a lot like we’ve reverted back to our nasty, brutish nature.

That probably wouldn’t surprise Hobbes. His state of nature isn’t meant to describe an actual period in human development; it’s a philosophical ghost story. It’s not a story about who we are, but who we might be if there were no law, order or state to restrain us.

Despite this, we should reflect on how, irrespective of all the social infrastructure Australia seems to offer, we’ve seen self-interest dominate on such a grand scale. The panic buying, hoarding, racism and at times scapegoating responses all demand interrogation.

How can this happen? How, in a time when we do have notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, can parents – OK, this parent – be scrambling around supermarkets looking for children’s pain medication for his teething daughter to no avail? How can wipes and nappies be in such short supply? When Hobbes envisioned the ‘war of all against all’, he didn’t envision the goal to be a clean bum in a time of crisis – yet here we are.

Three Australian women fight over toilet paper. pic.twitter.com/EAhErm4QaD

— DailyMirror (@Dailymirror_SL) March 8, 2020

We can perhaps find an answer, and some guidance, in the work of fellow social contract philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau thought Hobbes hadn’t gotten to the nub of the issue. The problem with the state of nature wasn’t lawlessness. Rather, it’s the belief that people live in perpetual competition to one another. Hobbes introduces the state to stop us from killing each other as a way of getting ahead, but he leaves in place the source of the problem: the mindset that we need to “get ahead” of one another.

Instead, Rousseau spent an enormous amount of energy discussing what he called “the general will”. This was his fix to Hobbes’ problem. To stop people from acting in competition to one another his idea was simple: decisions should be made with reference to what the whole of society, willing together, would support as a good idea. This way, nobody would be permitted to take more common resources than they needed, or was deemed fair under the circumstance. This way, no individual could have undue influence over society.

Imagine that. Imagine what happens if people rock up at the supermarket and think: what does everyone need right now? Imagine a mindset, a society and a marketplace where mutual obligation, care and concern were the primary motivators instead of self-interest. Imagine how much more – or less – toilet paper you’d have now. Imagine how much more sleep I’d have if my daughters teething pain could be medicated.

Unfortunately – and tellingly for us today – Rousseau told us that many societies would be unable to develop a sense of the general will if individuals lacked the virtue to set aside their personal self-interest.

However, I think Rousseau is being unfair here. Virtues aren’t practiced in a vacuum, they’re enabled or disabled by the context and the environment. And our society allows an enormous space where people are permitted – and encouraged – to pursue their own self-interest without regard for others. The market.

The influence of the market on, and at times over, the state is conspicuous in trying to understand why our shelves are so bare. When we act in the market, we act as consumers. And as consumers, there is only one rule: consume. If that everyone else misses out, so be it. Like Hobbes’s state of nature, the laws of consumption have no sense of right or wrong, justice or injustice.

Ethically, what’s required of us is to step into an environment of consumption without becoming consumers. Instead it requires us to maintain ourselves as citizens, who have concern for those around us and are eager to act in the shared interest and common good of all.

In part, it’s on us as individuals, not to leave our humanity and morality at the door of the supermarket. But it’s also on the market to more clearly align itself to the general will. Corrections that prevent overbuying toilet paper are an obvious step in that direction, but it’s akin to howling at the moon. The panic will shift to another product, and soon we’ll be playing whack-a-mole with a panicked consumer population who see their own security and comfort in competition with that of other people.

At times when we’re threatened and feel unsafe, our instinct is to batten down the hatches. However, that’s a game that guarantees there will be winners and losers. If we can find a way to see beyond ourselves, to pass a roll of paper under the stall to a neighbour, we might just find a way to get through this together.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 MAR 2020

The response to the novel coronavirus COVID-19 (now called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2) has been fascinating for a number of reasons. However, two matters stand out for me.

The first matter concerns the way that our choice of narrative framework shapes outcomes. From what we know of SARS-CoV-2 it is highly infectious and produces mortality rates in excess of those caused by more familiar forms of coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold. However, given that ‘novelty’ and ‘danger’ are potent tropes in mainstream media, most coverage has downplayed the fact that human beings have lived with various forms of coronavirus for millennia.

The more familiar we are with a risk, the more likely we are to manage it through a measured response. That is, we avoid the kind of panicky response that leads people to hoard toilet paper, etc. We can see how a narrative of familiarity works, in practice, by comparing the discussion of SARS-CoV-2 with that of the flu.

John Hopkins reports that an estimated 1 billion cases of flu (caused by a different type of virus) lead to between 291,000 and 646,000 fatalities worldwide each year. That is the norm for flu. Yet, our familiarity with this disease means that the world does not shut down each flu season. Rather than panic, we take prudent measures to manage risk.

I do not want to understate the significance of SARS-CoV-2, nor diminish the need for utmost care and diligence in its management. This is especially so given human beings do not possess acquired immunity to this new virus (which is mutating as it spreads). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 is currently thought to generate mortality rates greater than most strains of the flu.

However, despite this, I wonder if society would have been better served by locating this new virus on the spectrum of diseases affecting humanity – rather than as a uniquely dangerous new threat.

This brings me to the second matter of interest that I think worth mentioning. Like many others, I have been struck by the universal commitment of Australia’s leading politicians to legitimise their decisions by relying on the advice of leading scientists.

I do not know of a single case of a politician refusing to accept the prevailing scientific consensus. As far as I know, there has been nothing said along the lines of, “all scientific truth is provisional” or “some scientists disagree”, etc. I have not heard politicians denying the need to take action because it might put some jobs at risk. Nor has anyone said that action is futile ‘virtue signalling’ because a tiny nation, like Australia, can hardly affect the spread of a global pandemic.

As such, I have been left wondering how to explain our politicians’ commitment to act on the basis of scientific advice when it comes to a global threat such as presented by SARS-CoV-2 – but not when it comes to a threat of equal or greater consequence such as presented by global warming.

Taken together – these two issues raise many important questions. For example: are we only able to mount a collective response under conditions of imminent threat? If so, is this why politicians so often play upon our fears as the means for securing our agreement to their plans? Does this approach only work when the risks can be framed in terms of our individual interests – and perhaps those of our immediate families – rather than the common good? Or, more hopefully, can we embrace positive agendas for change?

For my part, I still believe that people are open to good arguments … that they can handle complex truths – if only they are presented in accessible language by people who deserve to be trusted. It’s the work of ethics to make this possible.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

COP26: The choice of our lives

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 9 MAR 2020

Prominent contemporary American political philosopher, Michael J. Sandel’s (1953—present) work on justice, ethics, democracy and markets has connected with millions around the world.

His popular first year undergraduate course, Justice, became Harvard University’s first freely available course – online and televised.

Sandel’s Socratic approach connects moral and political theories and concepts to everyday life, helping to engage his audience in otherwise complex philosophical ideas.

He recognises, “there is a great hunger…to engage in serious reflection on big, ethical questions that matter politically, but also that matter personally.”

We all face ethical and political dilemmas, decisions and disagreements. These are not always easy to resolve and often bring us into conflict with others whose views differ from our own. Sandel is quite clear on the remedy, that “we need to rediscover the lost art of democratic argument” and this is precisely what he models and facilitates.

Who we are

Sandel is known for emphasising the social aspects of our identities. He says that we think of ourselves “as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons or daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic”, which illustrates our attachment to others as well as our contextual social reality. In this way he offers a critique of Rawlsian liberalism.

Liberalism, and particularly the view espoused by John Rawls in his 1971 book A Theory of Justice, sees people as highly individualised, rational and focussed on defending their rights. On this view, the government’s role is to protect individual freedom and fairly obtain and distribute resources.

Rawls’ famous thought experiment of the ‘veil of ignorance’ asks us to imagine ourselves prior to knowing who we are going to be in the world. If we do not know whether we will be male or female, able-bodied or beautiful or the opposite, or which race, class, or religion we will belong to, we should be able to fairly decide on the best policies by which a society should operate. This is the best way, Rawls believed, to achieve justice.

Conversely, Sandel argues that humans cannot be neutral in this way. When figuring out what we should do, people bring their “moral and spiritual encumbrances, traditions, and convictions” with them to the negotiating table.

In this way, talk of rights can only be understood in relation to what people think of as good, valuable and important in their lives, which is connected to their social and material circumstances. Thus, the abstract thought experiment Rawls details simply won’t work.

Civic engagement

Against the view that we are always free to choose what and who we care about and which are our special obligations, Sandel points out that certain commitments, such as those to our family and our political community, bind and restrict us in certain ways.

Precisely because we cannot be disinterested or disconnected when it comes to matters of political decision making, Sandel emphasises the importance of finding ways to support and increase civic engagement – as evidenced in his TED talk, The lost art of democratic debate, watched by over 1.4 million people.

By having a positive and active national political community that works towards the good of all, we can make sense of justice for real people situated in real world contexts. In this respect, he believes dialogue and respectful disagreement are vital.

“If everyone feels they are heard, even if they don’t get their way, they will be less resentful than if we pretend we are going to decide policy in a way that is neutral.”

Market societies

Something that really concerns Sandel is how we, in developed countries, have gone from having a market economy to becoming market societies. What this means is that everything is up for sale. If market thinking and market values dominate, then other values – those of the good life, education, relationships, and creativity – are squeezed out.

If everything is valued first and foremost economically, then the difference between the haves and have-nots matters. If money buys you a better education, better health care, better legal representation, as well as more material possessions and business opportunities, the cycle of poverty becomes increasingly insurmountable.

The ‘luck’ of being born into wealth should not count more towards one’s success than hard work, natural talent or intelligence. Yet this is increasingly evident in today’s world and, in this way, inequality and affluence determine much more than they should. As a result, the notion of ‘merit’ is loaded.

Sandel claims we live in a meritocratic society, yet merit itself is a tyrannical construct:

“The notion that your fate is in your hands, that ‘you can make it if you try!’ is a double-edged sword. Inspiring in one way, but invidious in another. It congratulates the winners, but denigrates the losers, even in their own eyes”.

Instead, we need to be more inclusive and recognise that everyone has a role to play in our shared fate, regardless of who is wealthy or poor. In order to move forward together, “we need to find our way to a morally more robust discourse, one that takes seriously the corrosive effect of meritocratic striving on the social bonds that constitute our common life.”

Posing provocative questions such as: Should you pay a child to read a book? Should a prisoner pay to upgrade their accommodation? Can we place a monetary value on the Great Barrier Reef? Sandel compels us to consider what values should govern civic life, and how we might rethink the role of the market in a democratic society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: The Panopticon

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is every billionaire a policy failure?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 6 MAR 2020

A virus knows no race. It is indifferent to your religion, your culture and your politics. All a virus ‘cares about’ is your biology … For that, one human is as good as any other.

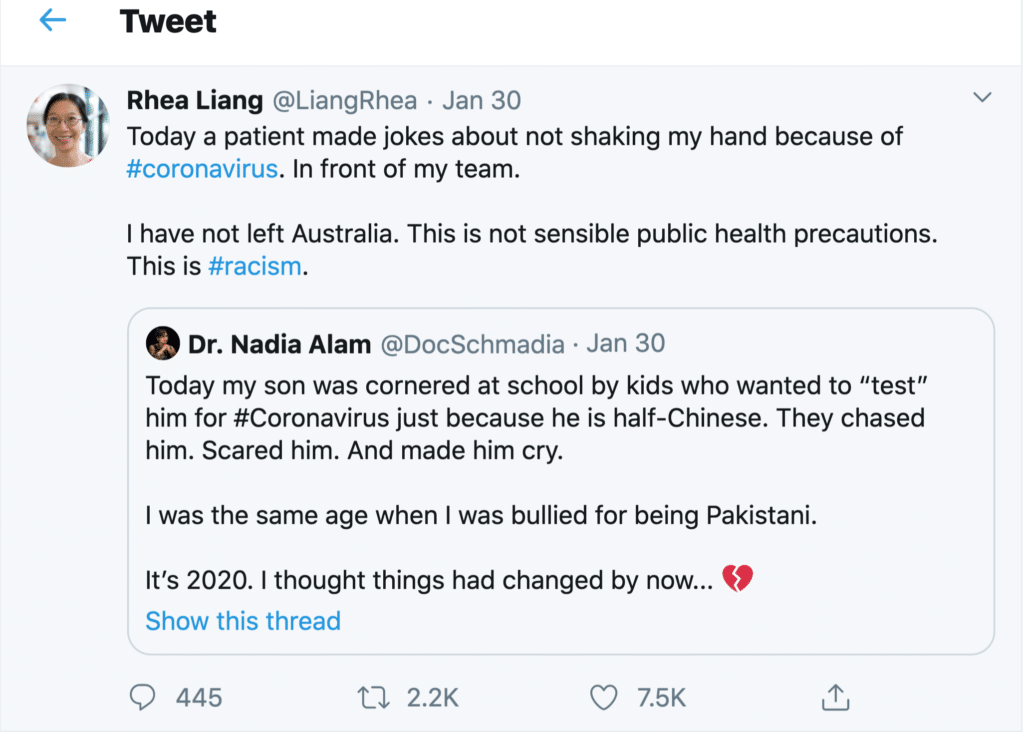

Despite this, it’s easy enough to find recent reports of Australians experiencing discrimination for no reason other than their Chinese family heritage.

Such attacks are examples of racism – the irrational belief that an individual or group possesses intrinsic characteristics that justify acts of discrimination. That this is occurring is not in doubt.

For example, Australia’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Brendan Murphy has seen enough of such behaviour to make explicit reference to the phenomena, labelling xenophobia and racial profiling as “completely abhorrent”.

Professor Murphy’s position is one of principle. However, there is also a practical aspect to his admonition. Managing the risks of an outbreak of a pathogen like the novel coronavirus COVID-19 requires health officials and the wider community to make rational choices based on an accurate assessment of risk. Racism is irrational. It distorts judgement and draws attention away from where the risks really lie. Ethically it is wrong. Medically, it is idiotic and dangerous.

This rise in racism, prompted by the emergence of COVID-19, reveals how thin the veneer of decency is that keeps latent racist tendencies in check. It seems that, given half-a-chance, the mangy old dog of Sinophobia is ready to raise its head, no matter how long it has laid low.

Of course there is nothing new about Sinophobia in Australia. Fear of the ‘yellow peril’ is woven through the whole of Australia’s still-unfolding colonial history. Many factors have stoked this fear, including: persistent doubts about the legitimacy of British occupation of an already settled continent, ignorance of (and indifference to) Chinese history and culture, the European cultural chauvinism that such ignorance fosters, the belief that numerical supremacy is, ultimately, a determining force in history, the need to find scapegoats when the dominant culture falters, and so on.

Whatever the historical cause of this persistent fear, the present ‘trigger’ is the inexorable rise of China as an economic and military super power – a power that is increasingly inclined to demand (rather than earn) deference and respect.

The situation is made more volatile by the growing tendency for the China of President Xi Jinping to link its power and success to what is uniquely ‘Chinese’ about its history and character. Add to this a broadly accepted Chinese cultural preference for harmony and order and the nation is often presented as if it is a ‘monolithic whole’ – not just in terms of its autocratic government but in its essential character.

Unfortunately, all of this feeds the beast of racist prejudice. Those who feel threatened by the changing currents of history seize on even the flimsiest threads of difference and use these to weave a narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’ – in which others are presented as being essentially and irremediably different. This is the racists’ central trope – that difference is more than skin deep! Biology makes you one of ‘us’ or you are not.

It’s nonsense. Yet, it’s a nonsense that sticks in some quarters, especially during times of uncertainty such as this; when the general public is feeling betrayed by the elites, when institutions have lost trust and have weakened legitimacy and when increasing numbers of people fear for their future and that of their families.

Unfortunately, tough times provide fertile ground for politicians who are willing to derive electoral dividends by practising the politics of exclusion. It is a cheap but effective form of politics in which people define their shared identity in terms of who is kept outside the group.

It is far harder to practise the politics of inclusion – in which disparate groups find a common identity in the things they hold in common. This too can work, but it takes great energy and superior skills of leadership to achieve this outcome. Yet, it is the latter approach that Australia must look for, if only as a matter of national self-interest.

This is because racist attacks against Australians of Chinese descent also have a significant national security dimension. As I have written elsewhere, social cohesion is a vital component of a nation’s ‘soft power’ when defending against foes who covertly seek to ‘divide and conquer’.

The risk of such attacks is increasing as the world drifts back to a pre-Westphalian strategic environment in which the international, rules-based order breaks down and nations freely interfere with the domestic affairs of their rivals. In these circumstances, the last thing Australia needs is deepening divisions based on spurious beliefs about supposed racial deliveries.

Those who create or exploit those divisions wound the body politic, weaken our defences and undermine the public interest.

All of that said, it is important not to overstate the dimensions of the problem. Australia is a notable successful multicultural nation where harmonious relations prevail. This is despite there being an undercurrent of racism that has been more or less visible throughout Australia’s modern history.

Racism is never justified. Not by the fact that it is found to the same degree in other societies, and not even when its manifestation is rare. Although it offers little comfort, it should also be acknowledged that discrimination is as much a product of other forms of prejudice concerning religion, gender, culture, etc.

We have the capacity to do and be better. This is a choice we can and should make for the sake of our fellow citizens – whatever their background – and in the interests of the nation as a whole.

So, given that China is not likely to take a backwards step and Australians of Chinese background cannot (and should not) disguise their heritage, how should we respond to the latest bout of Sinophobia?

Attack prejudice with fact

A first step should be to follow the example of Australia’s Chief Medical Officer and attack prejudice with the facts. Professor Murphy’s example showed how facts about medicine can be deployed to calm fears and neutralise racist myths. This approach should be extended to other areas. For example, more should be known of the long history and extraordinary contribution of Australians of Chinese heritage.

This account should not merely tell the story of elite performance, economic contribution, etc. It should also speak of those who have fought in Australia’s wars, built its infrastructure, educated its children, nursed its sick … and so on. In short, we need to see more of the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Reframe the narrative

Second, we need to reframe the narrative about China and the Chinese. Today, most commentary portrays China as both a security threat and an economic enabler. It is both. However, this is only a small part of the story.

For the most part, we see little of the life of the Chinese people. We are largely ignorant of the achievements of their remarkable civilisation. One might think that the closeness of the economic relationship might be a positive factor. However, regular reporting about Australia’s economic dependence on China, is not helping the situation.

I know that this will seem counter-intuitive to some. However, the more we speak of Chinese students propping up our universities, of Chinese tourists sustaining our tourism industry and of Chinese consumers boosting our agricultural exports … the more it makes it sound as if the Chinese are little more than an economically essential ‘necessary evil’ – a ‘commodity’ that comes and goes in bulk.

This view of the Chinese negatively influences attitudes towards Australia’s own citizens of Chinese descent. Fortunately, a solution to the ‘commodification’ of the Chinese is at hand, if only we wish to embrace it. The large number of Chinese students who study in Australia offer an opportunity to build better understanding and stronger relationships.

Unfortunately, the Chinese student experience in Australia is reported not to be as positive as it should be. Too many arrive without the English language skills to engage more widely with the community. Too many find themselves lonely and isolated. Too many find solace in sticking with those they know and understand. With some justification, large numbers feel as if they are little more than a ‘cash cow’.

Invest in ethical infrastructure

Third, we need to invest in Australia’s own ‘ethical infrastructure’ – much of which is damaged or broken. We need to repair our institutions so that they act with integrity and merit the trust of the wider community. We need to work on the core values and principles that underpin social cohesion.

Part of this task must be to come to terms with the truth about the colonisation of Australia. This is not to invoke the ‘black arm band’ view of history. The truth is both good and bad. However, whatever its character, our truth remains untold. I sincerely believe that Australia’s ‘soft power’ is weaker than it would otherwise be, if only we could address this unfinished business.

Alleviate fear

Fourth and finally, the measures outlined above will be ineffective unless we also name the latent fears of average Australians. People across the nation want these ‘bread and butter’ issues to be acknowledged and addressed:

- How safe is my job?

- If I lose my current job, will I find another?

- If I can’t find another job, how will I pay my bills?

- Will I be cared for if I get sick?

- Will my children get an education that equips them to live a good life in the future?

- Can I move about with relative ease and efficiency?

- How will the nation feed itself?

- Are we safe from attack?

- Who can step in cases of natural disaster or man-made calamity?

- Why are our leaders not held to account when we are?

- Why can’t I be left alone to do as I please?

- Who cares about me and those I care about?

Failure to speak to the truth of these deep concerns leaves the field wide open for the lies of those who would stoke the fires of racism.

Unravel the complexities of the political relationship between China and Australia at ‘The Truth About China’, a panel conversation at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Saturday 4 April. Tickets on sale now

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

‘Woke' companies: Do they really mean what they say?

‘Woke’ companies: Do they really mean what they say?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Alliance The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

Virtue-signalling has a bad name. It is often derided as the boasting people do to feel superior – even when they have no intention of living up to the ideal.

It is like when they posted Facebook videos of pouring icy water over their own heads, hashtagged #IceBucketChallenge, but raised no money for research into Motor Neurone Disease.

Or when $US5.5 billion fast food company KFC appeared to use the challenge as a branding exercise, offering to donate up to $10,000 if its own buckets were used.

But here’s the thing: despite free riders and over-eager marketers, the 2014 viral campaign raised more than $A168 million in eight weeks and was able to fully fund a number of research projects.

If some of those getting in on the act gave nothing for the cause, does it matter? It is possible that, by flooding social media with the images, they helped build momentum for an extraordinarily successful campaign.

So, can virtue signalling also have a positive spin?

Conservative British journalist and former banker, James Bartholemew, claims to have invented the term “virtue signalling” in a column for The Spectator in 2015. He wrote: “It’s noticeable how often virtue signalling consists of saying you hate things.”

He says virtue signalling is often a person or brand attempting to aggrandise or promote themselves.

If you were frank, Bartholemew explains, what you would actually say is: “I care about the environment more than most people do” or “I care about the poor more than others”.

“But your vanity and self-aggrandisement would be obvious…”

Bartholemew says the term “virtue signalling” is pejorative in nature: “It is usually used as a judgement on what somebody else is saying. It is a judgement just like saying that somebody is boring or self-righteous. So it is not going to be used to praise somebody, but for taking a particular position.”

Virtue signalling: An attempt to show other people that you are a good person, for example by expressing opinions that will be acceptable to them, especially on social media.

Cambridge Dictionary definition.

It is social bonding

Philosopher and science writer, Dr Tim Dean, says virtue signalling has a social purpose – even when it is disingenuous. It expresses solidarity with a peer group, builds social capital and reinforces the individual’s own social identity.

“It sometimes becomes more important to believe and to express things because they are the beliefs that are held by my peer group, than it is to say things because we think they are true or false,” he says.

A secondary purpose according to Dr Dean is to distinguish that social group from all others, sometimes by saying something other groups will find disagreeable.

“I think a distant tertiary function is to express a genuinely held and rationally considered and justifiable belief.

“We are social first and rational second.”

Organisations use virtue signalling to broadcast what they stand for, differentiating themselves from the rest of the market by promoting themselves as good corporate citizens. Some of those organisations will be primarily driven by the marketing opportunity, others will be on a genuine mission to create a better planet.

A classic act of virtue signalling was the full-page advertisement in the New York Times, taken out last year by more than 30 B Corporations to pressure “big business” into putting the planet before profits. B Corps are certified businesses that balance profit and purpose, such as Ben and Jerry’s, Body Shop, Patagonia and the Guardian Media Group.

“We operate with a better model of corporate governance – which gives us, and could give you, a way to combat short-termism and the freedom to make decisions to balance profit and purpose,” the B Corps declared in their advertisement.

Their stated aim was to chivvy along the leaders in the Business Roundtable: 181 CEOs who had pledged to pledged to do away with the principle of shareholder primacy and lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders – customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders.

Whose business is it?

There are some questions leaders should consider before they sign their organisations up to a campaign. In whose interests is a company acting if it lobbies for a social or political cause? How does it decide which issues are appropriate for its support?

The questions are of particular concern to conservatives, who have watched the business community speak up on issues such as gender targets, climate change and an Australian republic.

When the CEO of Qantas, Alan Joyce, pledged his company’s support in favour of the right of gay couples to marry, in 2017, it raised the ire of the conservative think-tank, The Centre For Independent Studies (CIS).

Last year, the centre published Corporate Virtue Signalling: How to Stop Big Business from Meddling in Politics – a book by its then-senior research fellow, Dr Jeremy Sammut.

At the launch of his book last year, Sammut noted recent developments that included Rio Tinto and BHP becoming the first companies to support Indigenous recognition in the Australian Constitution, a group of leading company directors forming a pressure group to push the Republican cause in Australia, while industry super funds were using their financial muscle to force companies to endorse “so-called socially responsible climate change” and industrial relations policies that aligned with union and Labor Party interests.

“If the proponents of CSR [corporate social responsibility] within Australian business, get their way, the kind of political involvement that we saw from companies during the same-sex marriage debate will be just a start,” Sammut said.

“It’s going to prove to be just the tip of the political meddling by companies in social issues that really have very little to do with shareholders’ interests, and the true business of business.”

Sammut pointed the finger at CSR professionals in human resources divisions and consultancy firms: “… they basically have an activist mindset and use the idea of CSR as a rubric, or a license, to play politics with shareholders money.”

Their ultimate ambition is to “subvert the traditional role of companies and make them into entities that campaign for what they call systemic change behind progressive social, economic, and environmental causes – all under the banner of CSR.”

Decide if it is branding or belief

It is not only the conservatives who view corporate virtue signalling with deep suspicion, those who may be considered “woke” (socially aware) can also view the practise with cynicism – especially when they have seen so many organisations pretend to be better than they are.

Dr Tim Dean notes there is a difference between corporate virtue signalling and marketing. While the former reinforces social bonds within a particular group, marketing appeals to people’s values in an attempt to elevate the company’s status, improve the brand and increase sales.

“I have some wariness around corporate statements of support for issues that are outside of their products and services, because I see there is a certain amount of disingenuousness about it.”

When a company promotes a stance on a social issue, it is often unclear whether it is supported by the CEO, the board, or the employees.

“ … if it’s separate from the work that they do, or does not relate directly to the structure, that’s where I think it’s a little more difficult to know exactly what the motivation is and whether we can trust it,” says Dean.

“Now, there are certainly times when we need to stand up for our moral beliefs and make public statements, even when we think they’re going to be strongly opposed. But I think I see that as more of an individual obligation rather than a business’s obligation.”

He says, when organisations are considering taking a moral stance, they should first ask themselves:

- Why are you doing it? Is it an honestly-held belief, or marketing?

- Whose views are you representing? What proportion of employees supports your stance?

- Is it any of your business’ business? Does it fit with the values of your organisation?

- Why do it as an organisation, rather than as individuals?

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Recovery should be about removing vulnerability, not improving GDP

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z’s future

Join our newsletter

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

If a company wants to be trusted, it must be much more than merely competent. And, compared with community expectations around ethics, an ability to do the job is a relatively minor concern.

We now know ethical concerns are three times more important than being able to do the job to the expected standard, thanks to a recent global poll by the Edelman Trust Barometer.

Australia has been in a state of distrust for almost a decade, with an increasingly cynical and disappointed public, drip-fed on a regular diet of corporate and institutional scandals.

The recent bushfires made matters worse, with Australians feeling they were no longer in control, according to Edelman Australia CEO Michelle Hutton.

“The lack of empathy, authenticity and communications crushed trust across the country,” she told the Australian Financial Review.

The majority of the mass population do not trust their institutions to do what is right, according to the Barometer.

Executive director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff, warns that important institutions in Australia are getting “perilously close” to losing their legitimacy – which creates anger, insecurity and fear.

None of those things allow a society to enjoy the kind of settled peace that it would aspire to, he said recently.

“Trust is an issue because most of our institutions have betrayed their purpose. I don’t think they set out to do it in a deliberate way. I think they forgot their purpose, whether it’s churches or banks or in politics,” he said on the ABC’s Q&A programme in February.

Longstaff defines trust as an ability to rely on somebody to do what they have said, even when no one is watching them.

The Edelman Trust Barometer divides company trust scores into four elements, and ability (or competence) accounted for 24% of the total. Ethical concerns make up the remainder: integrity 49%, purpose 12%, and dependability 15%.

The researchers find the reason for the general lack of trust in institutions is that none are regarded as both competent and ethical.

Among the institutions – business, government non-government organisations (NGOs) and the media – only the NGOs were seen as ethical (but not competent) and only business was found to be competent (but not ethical).

Part of the explanation for the poor regard for business ethics could be explained by the tendency of companies to give a higher priority to communicating their performance than their commitment to ethics and integrity, or their purpose and vision for the future, say the researchers.

“At the same time, stakeholder expectations have risen,” they say.

“Consumers expect the brands they buy to reflect their values and beliefs, employees want their jobs to give them a sense of purpose, and investors are increasingly focused on sustainability and other ethical commitments as a sign of a company’s long-term operational health and success.

“Business is already recognised for its ability to get things done. But to earn trust, companies must make sure that they are acting ethically, and doing what is right. Because for today’s stakeholders, competence is not enough.”

Dr Longstaff says regaining trust starts with owning up to mistakes.

“What we can expect of ourselves firstly sincerity, and then think before you act. Do that, and you can reasonably be assured that the trust that you hope for will be bestowed.”

How to rebuild trust:

Adopting a minimum threshold of fundamental values and principles can restore trust and minimise the risk of corporate failure.

- Respect people. Everyone has intrinsic value – regardless of their age, gender, culture, and sexual orientation. A person should never be used merely as a means to an end or as a commodity. This principle forbids wrongs, such as forced labour and supports the practice of stakeholder engagement.

- Do no harm. The goods and services should confer a net benefit to users without doing harm. Those who profit from engaging in harmful activity should disclose the nature of the risk.

- Be responsible. Benefits should be proportional to responsibility. One should look beyond artificial boundaries (such as the legal structures of corporations) to take into account the “natural” value-chain, such as how supply chains are viewed and concerning matters like corporate tax and its avoidance and evasion. This principle takes into account asymmetries in power and information to the detriment of weaker third parties.

- Be transparent and honest. These values are fundamental to the operation of free markets, in which stakeholders can make fully-informed decisions about the extent (of their involvement with the corporation. Corporations need to disclose details of the ethical frameworks that they employ when deciding whether or not a decision is “good” or “right”.

Source: Edelman Trust Barometer. An online survey in 28 markets of more than 34,000 people. Fieldwork was conducted between October 19 and November 18, 2019. A supplementary study was conducted in Australia in February 2020 to account for the bushfires. In Australia, 1,350 people were polled.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Can there be culture without contact?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Alliance The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

As Australians watched their country burn over the summer school holidays, we were all given an unforgettable reminder about what leadership in a crisis looks like.

We now know it looks like the 150,000 volunteer firefighters across Australia who left their families to face down monster infernos, making split-second decisions to attempt a rescue or save themselves.

The face of leadership is covered by a protective mask on an 11-year-old Mallacoota boy, Finn Burns at the helm of an outboard motor, steering to safety his mother, brother and family dog. Behind them, the sky glows a dirty blood-red as if from another planet.

Leadership is embodied in all the so-called “ordinary” people who leapt into action with garden hoses, set up evacuation centres, jumped into their boats to ferry supplies to cut-off communities, launched fundraisers and scoured the smouldering landscape to rescue wildlife.

These leaders took the initiative when the authorities were unavailable or overwhelmed by the scope of the disaster.

Everyday Australians stepping up

NSW Transport Minister and Malua Bay resident, Andrew Constance, recounted on ABC’s Q&A program: “There were community relief centres that were set up immediately after that fire event, without the involvement of government. That was what was heartening. It was in Cobargo, Quaama, everywhere.

“I think the passion that people brought to that period, immediately after those nasty fire events, was something special. So, you can’t bottle it, you can’t pay for it, government can’t deliver it.”

Sitting in the ABC’s studio in Queanbeyan, just days after fighting fires on his own property and evacuating to the beach, the enormity of the experience was written on his exhausted face. He spoke about how he was still reeling and would get counselling to help through the aftermath.

Leadership consultant, Wayne Burns, lost a house at Lake Conjola to the fires and reflected on the difference between leadership and authority, penning an opinion piece in the Sydney Morning Herald.

“Leadership is an art exercised and practised deliberately. It is about influencing, encouraging, inspiring, and sometimes pushing and cajoling without being asked,” he writes.

“Leadership does not require authority, although it helps if a leader has the authority to direct and command resources.”

Filling a leadership vacuum

Speaking to The Ethics Centre of his experience at Lake Conjola, Burns says: “The people who had authority were overwhelmed. A lot was happening very quickly.”

He says that while those in government and emergency services were doing their best, they could not step beyond the authority of their official roles.

This created a “vacuum” which was filled by people who did not have authority, he says. These people took the initiative to do what needed to be done, commandeering water tanks and tools and making decisions about the property of other people.

“They stepped out of their everyday role, whether this was as a neighbour or as a retired person, and they created themselves a position of informal leadership.”

In Burns’ street, a retired engineer stayed behind in his home and became the unofficial spokesperson and decision-maker for around 24 neighbours. He negotiated with utilities companies, organised for dangerous trees to be cut down, helped Police track down residents, obtained access for insurance assessors, and arranged for spraying for asbestos.

“We all gave him informal power to make decisions on our behalf because we knew he had our interests at heart and we knew he was capable and we trusted him. So, it’s a transfer of trust from those with formal authority to those with informal authority,” says Burns, who studied leadership at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

US management consultant, Gary Hamel, says people who wonder if they are a leader should imagine themselves with no power.

“If, given this starting point, you can mobilise others and accomplish amazing things, then you’re a leader. If you can’t, well then, you’re a bureaucrat,” writes Hamel in an article with Polly LaBarre.

Withdrawing consent to be led

Burns says Australians traditionally have a respect for authority and become indignant if officials let them down. When that happens, they may refuse to recognise the legitimacy of those leaders.

In January, angry Cobargo, NSW, locals turned on Prime Minister Scott Morrison, with some refusing to shake his hand. “In that situation, the Prime Minister has the authority, but he wasn’t afforded the informal leadership by those people, who had withdrawn from him their permission for him to lead them,” says Burns.

Policies, procedures and protocol can constrain people in authority. However, in a crisis, greater leadership can sometimes be shown by those who step beyond their authorised roles. Burns points to Minister Constance, who broke ranks politically to criticise the Federal Government’s response to the bushfire emergency.

Minister Constance told a television interviewer that the Prime Minister had probably “got the welcome he deserved” when he visited Cobargo without alerting Constance, who is the local member.

He also criticised some of the nation’s well-known charities for their slowness in delivering aid.

Burns says that Minister Constance demonstrated natural leadership in his actions facing into the crisis.

“He stepped up and he really led that community because he knew what was happening, he knew what they needed. He really did stick his neck out and rock the boat,” says Burns of Constance.

But it’s also okay to be a follower

Burns says the people most likely to step up into informal leadership have self-belief and some understanding of the legal or physical risks they are taking. “There is no personality type, there are no natural-born leaders – they don’t exist – people just decide to act.”

Burns says there is also nothing wrong with being a follower: “Not everyone wants, or can, lead.” The role those individuals can play is to put their trust into someone who has their confidence. “That person may not know the answer, but can bring people together to get the answer.”

If you are interested in discussing any of the topics raised in this article in more depth with The Ethics Centre’s consulting team, please make an enquiry via our website.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

What are millennials looking for at work?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Consent

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to build a successful culture

How to build a successful culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

They say that what gets measured, gets managed (or improved). But when it comes to measuring corporate culture, that’s an idea that needs unpacking.

The corporate sector has traditionally taken a quantitative approach to risk management and governance. Compliance, regulation, risk and legislative frameworks are applied, analysed, audited and reported-on to varying degrees of accuracy and certainty.

Unfortunately, these management mechanisms do not in themselves lead to effective governance as evidenced by a multitude of corporate scandals and collapses. Overconfidence in the science of risk management can lead to faulty corporate governance – and could well lead to disaster.

The art of risk management and governance lies in the capability of directors and executives to navigate and understand the highly complex and unpredictable set of human behaviours and interactions that make up a modern organisation.

The current scientific approach to risk management is insufficient when seeking to mitigate non-financial risks to business success – leaving companies vulnerable to catastrophic levels of exposure. There is now a shift in thinking and an appreciation that the intangible qualities of culture are critical to the issue of risk management and corporate governance.

Can you measure culture?

The subtle aspects of an organisation, such as values, motivations and political dynamics, are difficult to measure, influence and describe, let alone govern effectively. Performance management and processes, culture and engagement surveys, leadership competency assessments and organisational development initiatives are designed to create visibility of these aspects of organisations, but they often fall short by not accounting for the hidden, unspoken and un-self-aware aspects of human agents and the social systems in which they operate.

For over 20 years The Ethics Centre has been developing a unique approach to navigating these complexities – and, in the process, to accurately measure and understand culture.

Our Everest process assesses the level to which an organisation’s lived culture, and the actual systems and processes that drive the business, align with their intended ethical framework. Through in-depth exploration and analysis, gaps between the ideal and the actual culture of a business emerge, along with areas where formal systems and behaviours are misaligned to the stated values and principles.

Everest digs far deeper than a standard organisational review, identifying themes that relate to experiences over time and between groups of people, and reflecting them against the organisation’s formal policies and procedures. It enables companies to build a climate of trust for clients, shareholders and regulators; to unify employees around a common purpose and encourage values-aligned behaviour; to develop consistency between what you say you believe in and how you act; and to enable consistent decision making. Ultimately reducing the risk of ethical failure and poor decisions.

The Ethics Centre’s Everest process is a tried and tested methodology that produces invaluable insights and recommendations for change. In just the past five years, Everest has been deployed to assess the organisational culture of one of Australia’s largest banks, a major superannuation fund, a leading energy company, a major telco, a mining company and a wagering company – amongst many others.

Transforming organisations

Whilst most of our clients have chosen to keep their Everest reports confidential, two recent clients – The Australian Olympic Committee and Cricket Australia – elected to publicly release the reports into their organisations.

In both instances, these acts of “radical transparency” acted as a circuit-breaker following periods of widespread negative coverage. The release of these reports allowed the organisations to re-boot with renewed purpose and energy.

According to Matt Carroll, the widely-respected CEO of the AOC, “the review conducted by The Ethics Centre provided us with the platform to reset the organisation. We are committed to building a culture that is fit for purpose and aligned to our values and principles.”

Our report on Cricket Australia – following the infamous ball-tampering incident in 2018 – ran to 147 pages and contained 42 detailed recommendations. Our key finding was that a focus on winning had led to the erosion of the organisation’s culture and a neglect of some important values. Aspects of Cricket Australia’s player management had served to encourage negative behaviours.

It was clear, with the release of the report, that many things needed to change at Cricket Australia. And change they did. Cricket Australia committed to enacting 41 of the 42 recommendations made in the report, along with widespread renewal of their executive team and board.

“With culture, it’s something you’ve got to keep working at, keep your eye on, keep nurturing,” says CA’s chairman Earl Eddings. “It’s not: we’ve done the ethics report, so now we’re right.”

Most of the corporate collapses and scandals that have occurred lately were not the result of inadequate risk management, poorly crafted strategy or an absence of appropriate policies. Nor were they caused by incompetence or poorly trained staff.

In almost every case, it is becoming apparent that the causes lay in the psychology, ethics and beliefs of individuals and in an organisational culture that rewards short term value extraction over long term, sustainable value creation.

This misalignment between the espoused purpose, values and principles of an organisation and the real-time decisions being made each day can increase reputational and conduct risk leading to an erosion of trust, disengagement and poor customer outcomes.

Even companies with no burning platform benefit from the rigorous corporate health-check that Everest provides. To quote Ian Silk, CEO of another Everest client Australian Super:

“In my darkest moments I just wondered if we had all drunk the Kool-Aid, and whether the staff surveys reflected the facts. So I thought a really good way to test this would be to get The Ethics Centre to come in and do an entirely independent, entirely objective test of the culture and the ethics in the organisation.”

If you are interested in discussing any of the topics raised in this article in more depth with The Ethics Centre’s consulting team, please make an enquiry via our website.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Housing affordability crisis: The elephant in the room stomping young Australians

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ready or not – the future is coming

Ready or not – the future is coming

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

We are living in an exceptional era of human history. In a blink of the historical time scale, our species now have the skills to explore the universe, map and modify human genes and develop forms of intelligence that may far surpass their creators.

In fact, given the speed, unpredictability and sheer scale of what was previously unthinkable change, it’s actually better to talk of the future in the plural rather than the singular: the ‘futures’ are coming.

With the convergence of genetic engineering, AI and neurotechnology, entirely unique challenges arise that could test our assumptions about human identity and what connects us together as a species. What does the human experience mean in an era of augmentation, implantation, enhancement and editing of the very building blocks of our being in the future? What happens when we not only hack the human body, but the human mind?

The possible futures that are coming will arrive with such speed that those not ready for them will find themselves struggling to know how to navigate and respond to a world unlike the one we currently know. Those that invest in exploring what the future holds will be well placed to proactively shape their current and future state so they can traverse the complexity, weather the challenges, and maximise the opportunities the future presents.

The Ethics Centre’s Future State Framework is a tailored, future-focused platform for change management, cultural alignment and staff engagement. It draws on futuring methodologies, including trend mapping and future scenario casting, alongside a number of design thinking and innovation methodologies. What sets Future State apart is that it incorporates ethics as the bedrock for strategic and organisational assessment and design. Ethics underpins every aspect of an organisation. An organisation’s purpose, values and principles set the foundation for its culture, gives guidance to leadership, and sets the compass needed to execute strategy.

The future world we inhabit will be built on the choices we make in the present. Yet due to the sheer complexity of the multitudes of decisions we make every day, it’s a future that is both unpredictable and emergent. The laws, processes, methods and current ways of thinking in the present may not serve us well in the future, nor contribute best to the future that we want to create. By envisioning the challenges of the future through an ethics-centred design process, the Future State Framework ensures that organisations and their culture are future-proof.

The Future State Framework has supported numerous organisations in reimagining their purpose and their unique economic and social role in a world where profit is rapidly and radically being redefined. Shareholder demand is moving beyond financial return, and social expectations toward the role of corporations are shifting dramatically into the future.

The methodology helps organisations chart a course through this transformation by mapping and targeting their desired future state and developing pathways for realising it. It been designed to support and guide both organisations facing an imminent burning platform and those wanting to be future forward and leading – giving them the insight to act with purpose – fit for the many possibilities the future might hold.

If you are interested in discussing any of the topics raised in this article in more depth with The Ethics Centre’s consulting team, please make an enquiry via our website.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we need land tax, explained by Monopoly

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership