McKenzie... a fractured cog in a broken wheel

McKenzie… a fractured cog in a broken wheel

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

In many cases, the response to scandal is often as instructive as an assessment of its cause. So it has proved to be in the case of the issues that led to the resignation of Senator Bridget McKenzie as a Federal Government Minister.

The findings of the Auditor General unleashed a fair amount of anger and disgust – especially amongst community groups who were deemed to be meritorious recipients of funding but who missed out due to political considerations.

While I understand the outrage, strong emotions can make us blind to areas of ethical importance. As citizens, we need to notice the rapid normalisation of deviance that is eroding the foundations of our representative democracy.

In this, we should look to the insights of Edmund Burke who recognised the role played by traditions and conventions in maintaining the integrity of institutions and societies.

Those who know my writings might be surprised to find me ‘channelling’ Burke. For three decades, I have warned of the perils of unthinking custom and practice. But note that my target has always been practices and arrangements that are unthinking. I am a great admirer of customs and practices that derive their life from a conscious application of purpose, values and principles.

Too often, it is the dead hand of tradition that leads institutions to betray their underlying purposes, lose legitimacy and invite revolution. In that sense, I think that Edmund Burke and I would be in perfect accord.

I also think that Burke would be deeply concerned by the radical turn away from convention taken by the government of Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, in response to the ANAO’s ‘Sports Rort’ Report.

The government’s response has been marked by a persistent refusal to acknowledge and uphold, in practice, a couple of fundamental principles. First, that public power and monies (levied by taxes) should be used exclusively for public purposes. Second, that Ministers are responsible for all that is done in their name.

Instead, the government and its representatives have sought to distract the public by laying some false trails. They have claimed that ‘no rules were broken’. They have argued that the ‘ends justified the means’. They have suggested that the Minister should be excused from responsibility for the activities of her advisers (and possibly advisers in the offices of other ministers) who shaped decisions according to the political interests of the Coalition parties.

The fact that Senator McKenzie resigned over a ‘technical breach’ of the Ministerial Code – without any sense of remorse or censure for the way she exercised discretion in the allocation of public funds – has reinforced the public’s perception that politics and ethics have become estranged.

Just the other day someone said to me, “I can’t believe you expected anything different …”. The person then paused, in mid-sentence, and said, “Did I really just say that …? What has happened to us?”. Indeed, how have we come to accept such low standards as ‘normal’? When will we realise that we are being robbed of our reasonable expectations as citizens in a democracy?

Our government’s behaviour may deserve moral censure. However, we should not let this obscure the fact that its response to the ‘Sports Rort’ reveals a woeful lack of commitment to the preconditions for a functioning representative democracy. It is this, more than anything else, that should really worry us.

“Our government’s behaviour may deserve moral censure. However, we should not let this obscure the fact that its response to the ‘Sports Rort’ reveals a woeful lack of commitment to the preconditions for a functioning representative democracy.”

One result of a lack of clear commitment to ethics within government has been the growing demand for a Federal Integrity Commission. The idea is popular with the general public – who are sick of being held accountable for their conduct while watching the most powerful people in the nation letting each other off the hook. Given this, the major political parties are committed to the creation of this new, independent oversight body.

Personally, I think it incredibly sad that it has come to this. That multiple generations of politicians, from across the political spectrum, have made this necessary is an indictment of their stewardship of our democratic institutions.

However, if it is to be done, then it must be done well. There is no point in the Parliament putting in place a ‘paper tiger’ limited to reviewing the most extreme cases of ethical failure by the smallest possible subset of public officials. It is for that reason, I support the Beechworth Principles which were launched this week.

We deserve governments that earn our trust and preserve their legitimacy. Is that really too much to ask of our politicians?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Ethics, morality & law

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccines: compulsory or conditional?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On policing protest

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Danielle Harvey The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

When we settled on Town Hall as the venue for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) 2020, my first instinct was to consider a choir. The venue lends itself to this so perfectly and the image of a choir – a group of unified voices – struck me as an excellent symbol for the activism that is defining our times.

I attended Spinifex Gum in Melbourne last year, and instantly knew that this was the choral work for the festival this year. The music and voices were incredibly beautiful but what struck me most was the authenticity of the young women in Marliya Choir. The song cycle created by Felix Riebel and Lyn Gardner for Marliya Choir embarks on a truly emotional journey through anger, sadness, indignation and hope.

A microcosm of a much larger phenomenon, Marliya’s work shows us that within these groups of unified voices the power of youth is palpable.

Every city, suburb and school has their own Greta Thurnbergs: young people acutely aware of the dangerous reality we are now living in, who are facing the future knowing that without immediate and significant change their future selves will risk incredible hardship.

In 2012, FODI presented a session with Shiv Malik and Ed Howker on the coming inter-generational war, and it seems this war has well and truly begun. While a few years ago the provocations were mostly around economic power, the stakes have quickly risen. Now power, the environment, quality of life, and the future of the planet are all firmly on the table. This has escalated faster than our speakers in 2012 were predicting.

For a decade now the FODI stage has been a place for discussing uncomfortable truths. And it doesn’t get more uncomfortable than thinking about the future world and systems the young will inherit.

What value do we place on a world we won’t be participating in?

Our speakers alongside Marliya Choir will be tackling big issues from their perspective: mental health, gender, climate change, indigenous incarceration, and governance.

First Nation Youth Activist Dujuan Hoosan, School Strike for Climate’s Daisy Jeffery, TEDx speaker Audrey Mason-Hyde , mental health advocate Seethal Bency and journalist Dylan Storer add their voices to this choir of young Australians asking us to pay attention.

Aged from 12 to 21, their courage in stepping up to speak in such a large forum is to be commended and supported.

With a further FODI twist, you get to choose how much you wish to pay for this session. You choose how important you think it is to listen to our youth. What value do you put on the opinions of the young compared to our established pundits?

Unforgivable is a new commission, combining the music from the incredible Spinifex Gum show I saw, with new songs from the choir and some of the boldest young Australian leaders, all coming together to share their hopes and fears about the future.

It is an invitation to come and to listen. To consider if you share the same vision of the future these young leaders see. Unforgivable is an opportunity to see just what’s at stake in the war that is raging between young and old.

These are not tomorrow’s leaders, these young people are trying to lead now.

Tickets to Unforgivable, at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Saturday 4 April are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Plato

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are witnessing just how fragile liberal democracy is – it’s up to us to strengthen its foundations

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

BY Danielle Harvey

Danielle Harvey is Festival Director of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. A curator, creative producer and director, Harvey works across live performance, talks, installation, and digital spaces, creating layered programs that connect deeply with audiences.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data and Development

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

An examination of the profound loss of trust in liberal democratic institutions and the rise of populism.

Until quite recently, the liberal democracies of the West seemed to have it all. Led by the United States, they had defeated the Soviet Union to win the Cold War.

They had created an unprecedented level of prosperity. They had projected their culture – with its underlying values and principles – into every corner of the world.

Yet, in almost no time at all, the threads have been unravelling. Major institutions have lost the trust of the people. Ideological divisions have deepened and potentially destructive forms of populism have been unleashed.

Today, the global, rules-based order is looking shaky and we seem doomed to return to a world where nations act alone and ‘might is right’. How did this happen? What went wrong?

This essay traces how Enlightenment ideals shaped the hopes and expectations of citizens – only to be betrayed by leaders who forgot the defining purposes of the institutions they lead.

"A political system based on the intrinsic dignity of citizens has been replaced with one defined by a series of transactions, in which the government has become a 'providore' hawking its goods to customers whose currency is a vote."

DR SIMON LONGSTAFF

WHAT'S INSIDE?

History of the enlightenment

Current and future states

Recovering intrinsic dignity

The ethics of building anew

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

This is what comes after climate grief

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Ketan Joshi The Ethics Centre 21 JAN 2020

I can’t really lie about this. Like so many other people in the climate community hailing from Australia, I expected the impacts of climate change to come later. I didn’t define ‘later’ as much other than ‘not now, not next year, but some time after that’.

Instead, I watched in horror as Australia burst into flames. As the worst of the fire season passes, a simple question has come to the fore. What made these bushfires so bad?

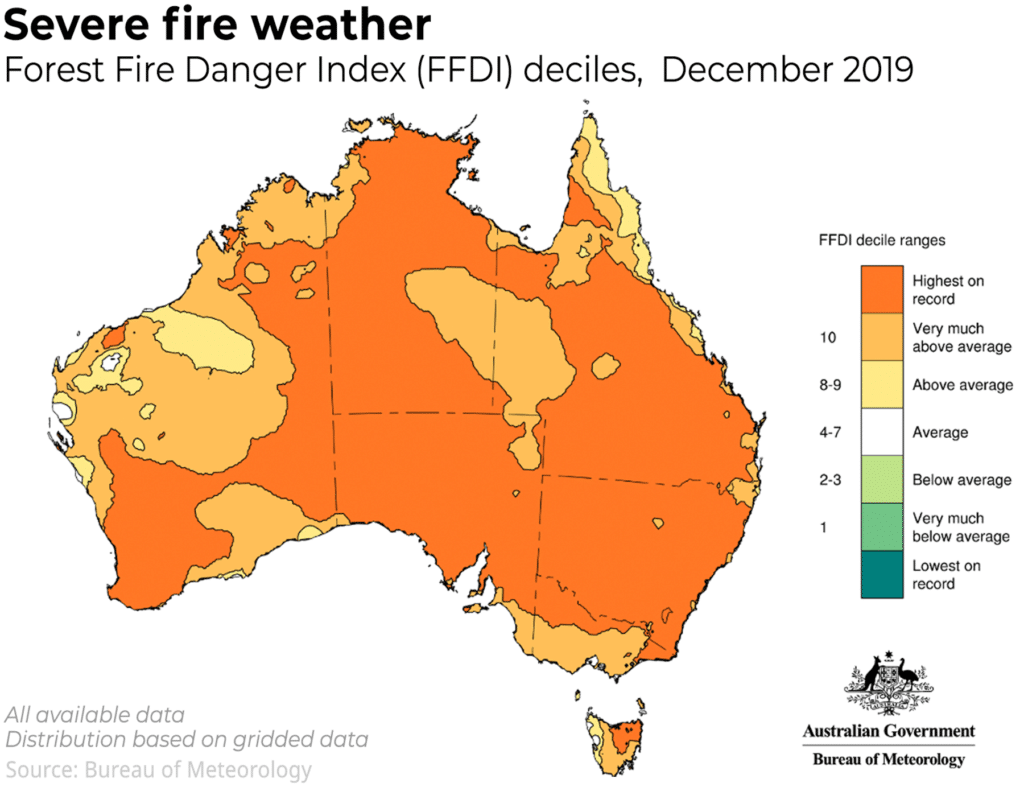

The Bureau of Meteorology confirms that weather conditions have been tilting in favour of worsening fire for many decades. The ‘Forest Fire Danger Index’, a metric for this, hit records in many parts of Australia, this summer.

The Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub is unequivocal: “Human-caused climate change has resulted in more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires in recent decades for many regions of Australia…These trends are very likely to increase into the future”.

Bushfire has been around for centuries, but the burning of fossil fuels by humans has catalysed and worsened it.

Having moved away from Australia, I didn’t experience the physical impacts of the crisis. Not the air thick with smoke, or the dark brown sky or the bone-dry ground.

But I am permanently plugged into the internet, and the feelings expressed there fed into my feed every day. There was shock at the scale and at the science fictionness of it all. Fire plumes that create their own lightning? It can’t be real.

The world grieved at the loss of human life, the loss of beautiful animals and ecosystems, and the permanent damage to homes and businesses.

Rapidly, that grief pivoted into action. The fundraisers were numerous and effective. Comedian Celeste Barber, who set out to raise an impressive $30,000 AUD, ended up at around $51 million. Erin Riley’s ‘Find a Bed’ program worked tirelessly to help displaced Australians find somewhere to sleep. Australians put their heads down and got to work.

It’s inspiring to be a part of. But that work doesn’t stop with funding. Early estimates on the emissions produced by the fires are deeply unsettling. “Our preliminary estimates show that by now, CO2 emissions from this fire season are as high or higher than the CO2 emissions from all anthropogenic emissions in Australia. So effectively, they are at least doubling this year’s carbon footprint of Australia”, research scientist Pep Canadell told Future Earth.

There is some uncertainty about whether the forests destroyed by the blaze will grow back and suck that released carbon back into the Earth. But it is likely that as fire seasons get worse, the balance of the natural flow of carbon between the ground and the sky will begin to tip in a bad direction.

Like smoke plumes that create their own ‘dry lightning’ that ignite new fires, there is a deep cyclical horror to the emissions of bushfire.

It taps into a horror that is broader and deeper than the immediate threat; something lingers once the last flames flicker out. We begin to feel that the planet’s physical systems are unresponsive. We start to worry that if we stopped emissions, these ‘positive feedbacks’ (a classic scientific misnomer) mean we’re doomed regardless of our actions.

“An epidemic of giving up scares me far more than the predictions of climate scientists”, I told an international news journalist, as we sat in a coffee shop in Oslo. It was pouring rain, and it was warm enough for a single layer and a raincoat – incredibly strange for the city in January.

She seemed surprised. “That scares you?” she asked, bemused. Yes. If we give up, emissions become higher than they would be otherwise, and so we are more exposed to the uncertainties and risks of a planet that starts to warm itself. That is paralysing, to me.

It is scarier than the climate change denial of the 2010s, because it has far greater mass appeal. It’s just as pseudoscientific as denialism. “Climate change isn’t a cliff we fall off, but a slope we slide down”, wrote climate scientist Kate Marvel, in late 2018.

In response to Jonathan Franzen’s awful 2019 essay in which he urges us to give up, Marvel explained why ‘positive feedbacks’ are more reason to work hard to reduce emissions, not less. “It is precisely the fact that we understand the potential driver of doom that changes it from a foregone conclusion to a choice”.

A choice. Just as the immediate horrors of the fires translated into copious and unstoppable fundraising, the longer-term implications of this global shift in our habitat could precipitate aggressive, passionate action to place even more pressure on the small collection of companies and governments that are contributing to our increasing danger.

There are so many uncertainties inherent in the way the planet will respond to a warming atmosphere. I know, with absolute certainty, that if we succumb to paralysis and give up on change, then our exposure to these risks will increase greatly.

We can translate the horror of those dark red months into a massive effort to change the future. Our worst fears will only be realised if we persist with the intensely awful idea that things are so bad that we ought to give up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

BY Ketan Joshi

Was a speaker at IQ2: It's too soon to ditch fossil fuels. He is a science communicator with over eight years experience across The Monthly, Gizmodo, Cosmos and with the CSIRO.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Extending the education pathway

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

In the course of 2019, The Ethics Centre reviewed and adopted a new strategy for the five years to 2024.

The key insight to emerge from the strategic planning process was that the Centre should focus on growing its impact through innovation, partnerships, platforms and pathways.

We focus here on just one of those factors – ‘pathways’ and, in particular, the education pathway.

The Ethics Centre is not new to the education game. To this day, the establishment of Primary Ethics – which teaches tens of thousands of primary students every week in NSW – is one of our most significant achievements.

As Primary Ethics continues to break new ground, we feel it’s time to bring our collective skills to bear along the broader education pathway.

With this in mind, we’re delighted to report that The Ethics Centre and NSW Department of Education and Training have signed a partnership to develop curriculum resources and materials to support the teaching and learning of ethical deliberation skills in NSW schools, including within existing key learning areas.

This exciting project will see us working with and through the Department’s Catalyst Innovation Lab alongside gifted teachers and curriculum experts – rather than merely seeking to influence from the outside.

In addition, we have also formed a further partnership with one of the Centre’s Ethics Alliance members, Knox Grammar School. This will involve the establishment of an ‘Ethicist-in-residence’ at the school, the application of new approaches to exploring ethical challenges faced by young adults, and the development of a pilot program where students in their final years of secondary education undertake an ethics fellowship at the Centre.

In due course, we hope that the work pioneered in these two partnerships and others will produce scalable platforms that can be extended across Australia. Detailed plans come next, and we believe the potential for impact along this pathway is significant.

We believe ethics education is a central component of lifelong learning – extending from the earliest days of schooling through secondary schooling, higher education and into the workplace.

The broadening of the education pathway therefore provides new opportunities for The Ethics Centre and Primary Ethics to work together – sharing our complementary skills and experience in service of our shared objectives, for the common good.

If you have an interest in supporting this work, at any point along the pathway, then please contact Dr Simon Longstaff at The Ethics Centre, or Evan Hannah, who leads the team at Primary Ethics.

Dr Simon Longstaff is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre: www.ethics.org.au

Evan Hannah can be contacted via Primary Ethics at: www.primaryethics.com.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A burning question about the bushfires

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

At the height of the calamity that has been the current bushfire season, people demanded to know why large parts of our country were being ravaged by fires of a scale and intensity seldom seen.

In answer, blame has been sheeted home to the mounting effects of climate change, to failures in land management, to our burgeoning population, to the location of our houses, to the pernicious deeds of arsonists…

However, one thing has not made the list, ethical failure.

I suspect that few people have recognised the fires as examples of ethical failure. Yet, that is what they are. The flames were fuelled not just by high temperatures, too little rain and an overabundance of tinder-dry scrub. They were also the product of unthinking custom and practice and the mutation of core values and principles into their ‘shadow forms’.

Bushfires are natural phenomena. However, their scale and frequency are shaped by human decisions. We know this to be true through the evidence of how Indigenous Australians make different decisions – and in doing so – produce different effects.

Our First Nations people know how to control fire and through its careful application help the country to thrive. They have demonstrated (if only we had paid attention) that there was nothing inevitable about the destruction unleashed over the course of this summer. It was always open to us to make different choices which, in turn, would have led to different outcomes.

This is where ethics comes in. It is the branch of philosophy that deals with the character and quality of our decisions; decisions that shape the world. Indeed, constrained only by the laws of nature, the most powerful force on this planet is human choice. It is the task of ethics to help people make better choices by challenging norms that tend to be accepted without question.

This process asks people to go back to basics – to assess the facts of the matter, to challenge assumptions, to make conscious decisions that are informed by core values and principles. Above all, ethics requires people to accept responsibility for their decisions and all that follows.

This catastrophe was not inevitable. It is a product of our choices.

For example, governments of all persuasions are happy to tell us that they have no greater obligation than to keep us safe. It is inconceivable that our politicians would ignore intelligence suggesting that a terrorist attack might be imminent. They would not wait until there was unanimity in the room. Instead, our governments would accept the consensus view of those presenting the intelligence and take preventative action.

So, why have our political leaders ignored the warnings of fire chiefs, defence analysts and climate scientists? Why have they exposed the community to avoidable risks of bushfires? Why have they played Russian Roulette with our future?

It can only be that some part of society’s ‘ethical infrastructure’ is broken.

In the case of the fires, we could have made better decisions. Better decisions – not least in relation to the challenges of global emissions, climate change, how and where we build our homes, etc. – will make a better world in which foreseeable suffering and destruction is avoided. That is one of the gifts of ethics.

Understood in this light, there is nothing intangible about ethics. It permeates our daily lives. It is expressed in phenomena that we can sense and feel.

So, if anyone is looking for a physical manifestation of ethical failure – breathe the smoke-filled air, see the blood-red sky, feel the slap from a wall of heat, hear the roar of the firestorm.

The fires will subside. The rains will come. The seasons will turn. However, we will still be left to decide for the future. Will our leaders have the moral courage to put the public interest before their political fortunes? Will we make the ethical choice and decide for a better world?

It is our task, at The Ethics Centre, to help society do just that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to respectfully disagree

We seem to have no trouble hurling opinions at each other. It is easy enough to form into irresistible blocks of righteous indignation. But discussion – why do we find it so hard?

What happened to the serious playfulness that used to allow us to pick apart an argument and respectfully disagree? When did life become ‘all or nothing’, a binary choice between ‘friend or foe’?

Perhaps this is what happens when our politics and our media come to believe they can only thrive on a diet of intense difference. Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Things that truly matter just overwhelm us with their significance. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Indeed, I think this must be it. Most of us have a deep-seated dislike of ambiguity. We easily submit to the siren call of fundamentalists in politics, religion, science, ethics… whatever. They sing to us of a blissful state within which they will decide what needs to be done and release us from every burden except obedience.

But there is a price to pay for certainty. We must pay with our capacity to engage with difference, to respect the integrity of the person who holds a principled position opposed to our own. It is a terrible price we pay.

The late, great cultural theorist and historian Robert Hughes ended his history of Australia, The Fatal Shore, with an observation we would do well to heed.

“The need for absolute goodies and absolute baddies runs deep in us, but it drags history into propaganda and denies the humanity of the dead: their sins, their virtues, their failures. To preserve complexity, and not flatten it under the weight of anachronistic moralising, is part of the historian’s task.”

And so it is for the living. The ‘flat man’ of history is quite unreal. The problem is too many of us behave as if we are surrounded by such creatures. They are the commodities of modern society, the stockpile to be allocated in the most efficient and economical manner.

Each of them has a price because none of them is thought to be of intrinsic value. Their beliefs are labels, their deeds are brands. We do not see the person within. So, we pitch our labels against theirs – never really engaging at a level below the slogan.

It was not always so. It need not be so.

I have learned one of the least productive things one can do is seek to prove to another person they are wrong. Despite knowing this, it is a mistake I often make and always end up wishing I had not.

The moment you set out to prove the error of another person is the moment they stop listening to you. Instead, they put up their defences and begin arranging counter-arguments (or sometimes just block you out).

Far better it is to make the attempt (and it must be a sincere attempt) to take the person and their views entirely seriously. You have to try to get into their shoes, to see the world through their eyes. In many cases people will be surprised by a genuine attempt to understand their perspective. In most cases they will be intrigued and sometimes delighted.

The aim is to follow the person and their arguments to a point where they will go no further in pursuit of their own beliefs. Usually, the moment presents itself when your interlocutor tells you there is a line, a boundary they will not cross. That is when the discussion begins.

At that point, it is reasonable to ask, “Why so far, but no further?” Presented as a case of legitimate interest (and not as a ‘gotcha’ moment) such a question unlocks the possibility of a genuinely illuminating discussion.

To follow this path requires mutual respect. Recognition that people of good will can have serious disagreements without either of them being reduced to a ‘monstrous’ flat man of history. It probably does not help that so much social media is used to blaze emotion or to rant and bully under cover of anonymity. People now say and do online things few would dare if standing face-to-face with another.

It probably does not help that we are becoming desensitised to the pain we cause the invisible victims of a cruel jibe or verbal assault. Nor does it help that the liberty of free speech is no longer understood to be matched by an implied duty of ethical restraint.

I am hoping the concept of respectful disagreement might make a comeback. I am hoping we might relearn the ability to discuss things that really matter – those hot, contentious issues that justifiably inflame passions and drive people to the barricades. I am hoping we can do so with a measure of good will. If there is to be a contest of ideas, then let it be based on discussion.

Then we might discover there are far more bad ideas than there are bad people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data and Development

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data & Development

Understand the ethical considerations in using big data across aid and development projects, and get a practical framework for decision making.

The increasing focus on impact, and its measurement is not solely about accountability. Instead, in this paper Dr Simon Longstaff presents why it’s driven by the desire to do as much good as possible in resource-constained conditions.

Traditionally the evaluation and monitoring of development based projects has been undertaken on the ground. However new technologies, big data, and AI have given rise to a host of possibilities, and with them, new ethical considerations.

The paper draws on insights generated by a project by Australia’s Department for Foreign Affairs, of which The Ethics Centre has been in consultation.

It offers an example Ethical Framework for decision making in new technology innovation for womens’ empowerment in Afghanistan, and a host of core tenants or considerations specific to the measurement and evaluation of development projects across areas of organisation, projects and data.

The report also provides a practical understanding of the components of an Ethical Framework, the virtue of ethical restraint, and the role of value driven decision making to benefit vulnerable groups in aid development work. Plus access a decision making model to slow down thinking and consider new perspectives.

It’s a great resource for anyone working with or associated with aid work domestically or internationally, particularly those involved in evaluation, measurement and data collection.

"The ethical impulse that drives innovation in development is to be admired. It is the same impulse that has led a range of actors to explore the possibilities of new technologies – not least in the field of data science – to improve the quality of monitoring and evaluation"

DR SIMON LONGSTAFF

WHAT'S INSIDE?

Ethical restraint

Empowering the vulnerable

Ethical Framework

Ethical decision making model

AUTHORS

Authors

Dr Simon Longstaff

Dr Simon Longstaff has been Executive Director of The Ethics Centre for 30 years, working across business, government and society. He has a PhD in philosophy from Cambridge University, is a Fellow of CPA Australia and of the Royal Society of NSW, and an Honorary Professor at ANU National Centre for Indigenous Studies. Simon was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2013.

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

The virtues of Christmas

The virtues of Christmas

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 20 DEC 2019

Christmas is upon us. It’s a time of giving. A time for celebrating with family and love ones. And a time to navigate a number of sticky ethical challenges.

It starts early in the morning; the gifts are distributed, and you unwrap Grandma’s exquisitely wrapped parcel only to reveal a hideous pair of underwear that may have once been in fashion during the great depression. You immediately call on your best poker face, but it may have already betrayed your disappointment. Should you lie and say, ‘thanks Nan, I really love them?’

Next comes the Christmas lunch tirade; you’re seated next to an opinionated uncle you only see once a year at Christmas who, predictably, after too many of his favourite Christmas beverages begins an annual festive diatribe that escalates rapidly from the opinionated to the offensive. Do you speak your mind?

Finally, the inevitable clash with your mother in law; she cannot help being critical about everything surrounding the festivities. The inevitable flare-up will happen after clearing away lunch, which you like to refer to it as the annual arm wrestle, a well-worn conflict over everything from how to stack the dishwasher to how the kids can and cannot play. This year will no doubt be worse as you are hosting the event. Do you stand your ground?

Most of us ask “What should I do?” when we think about ethics. However, we can approach it another way by asking, “What kind of person should I be?” Philosophical thinkers in this tradition turn to virtue ethics for the answers.

While it’s one thing to ask what kind of person should I be, it’s another thing to know how to live as that person. For Aristotle the answer to both of these questions is to act virtuously. Acting as though we already possess the best virtues is how we develop a virtuous character.

And if ever there was a time to test out the virtues of our character, it’s Christmas.

Virtue ethics, unlike other approaches, does not provide specific rules for addressing ethical questions. Instead, good actions are those that a person of good character would display. Aristotle, one of the most influential philosophers in this tradition, developed a comprehensive system of virtue ethics.

Let’s take a look at how it can help us navigate the minefield of Christmas’ annual dilemmas.

The underwear from Grandma? If asking what should you do, you might take a lead from consequentialism. You could simply smile and say ‘I love it Grandma’. After all, she meant well, a white lie makes her happy, keeps the economy ticking and doesn’t rock the family emotional boat. It produces the best overall outcome.

Other philosophers might suggest a different approach. Those in the deontological tradition, such as Immanuel Kant would argue that lying of any kind is unethical, even those white lies that are intended to spare someone’s feelings.

Unlike other approaches to ethics, virtue ethics does not rely on rules to guide action. While ‘do not lie,’ is a rule, ‘being honest’ is a virtue.

However, a virtue, on its own, doesn’t tell us too much that is helpful because virtues are interrelated, you can’t have one virtue without having others. To have a virtue is to be a particular type of person with a particular mindset and outlook on life. They are what’s called a ‘multi-track disposition’ – they go all the way down.

Honesty is not the only virtue at stake here. Acting virtuously requires us to calibrate between virtues. Because Grandma has the best intentions, she will no doubt take your honesty to heart. Honestly speaking your mind could be selfish at one extreme, and while a white lie at the other end might be considered selfless. What sits between these extremes Aristotle called the Golden Mean.

What would a fair person do? They might tell Grandma that they appreciate the thought but would like to do justice to her intentions by exchanging the gift for something that they will like, wear and remember Grandma every time they put it on.

So, let’s see what virtue ethics can teach us about managing that outspoken uncle. Imagine that dessert is now served and your uncle has flipped the switch to obnoxious. You try and avoid engaging with his tirades every year, but this year he is particularly offensive. His views are not only a dampener on the festive feels, but several members of the family are visibly hurt and upset by some of his more extreme views.

All families have their patterns that play out when people come together and the pre-determined roles we all play are difficult to shift.

What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining what a virtuous character would do in this situation we can start to practically explore how to become the best version of ourselves.

In the virtue ethics approach imagination is important in helping to shift unthinking and prescribed patterns of behaviours. What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining what a virtuous character would do in this situation we can start to practically explore how to become the best version of ourselves.

A virtuous person might ask themselves ‘how would I like to be treated if I were them?’ This particular uncle may not have many opportunities in their daily life to be heard. In many of the virtue ethics traditions compassion is a cardinal virtue. Exercising the virtue of compassion allows us to not only avoid rushing to judgement, but also gives us space to disarm the triggers that usually fire off in response to his toxic views.

The virtue of temperance – self-control and restraint – also helps here. While his views may trigger you strongly, appealing to logic with counterarguments will most likely not be effective.

It is almost impossible to change a person’s strongly held views with counter-logic. Paraphrasing back the points and emotions they are expressing not only lets them know their experience matters but also provides a circuit breaker by reflecting back their views. Research suggests that engaging in this way can make someone feel more understood and, as a result, less defensive or difficult.

When unsure about what the best virtue looks like in practice, virtue ethics suggests looking to someone of good character for direction by imagining how they would act in the same situation. Moral exemplars are an important feature of virtue ethics. Ethics is messy and no decision procedure provides a precise algorithm which will tell us definitively what to do when faced with difficult choices. Moral exemplars are people in our world who possess the best form of the virtues. Knowing what to do is not simply a matter of internalising a rule; for Aristotle virtue ethics it is about doing the right thing at the right time, in the right way and for the right reason. Moral exemplars help show us the way.

So, when it comes to the inevitable clash with your mother in law, imagine what someone you admire most would do. A moral exemplar might act intentionally with the virtues of humility, grace and generosity, showing her that what is important in hosting Christmas is not the power struggle to control the day but respecting differences and others’ boundaries. They might find ways to include some of her traditions in the day.

The development of character is at the heart of virtue ethics. We develop that character throughout our life through the virtues and in doing so we make wise choices.

This Christmas people may be looking at you to be that person.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 DEC 2019

If you’re looking for ways to support a more ethical life, here are five simple lifestyle changes that can help get you there.

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to an increase in the experience of positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand other people’s mental states are different from our own. It’s a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drink driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ – weakening our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships