Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gordon Young 17 JAN 2019

Few topics bridge the ever widening divide between both sides of politics quite like the need to manage population growth.

Whether it’s immigration or environmental sustainability, fiscal responsibility or social justice. That the global population breached 7.5 billion in 2017 has everyone concerned.

We are at the point where the sheer volume of people will start to put every system we rely on under very serious stress.

This is the key idea motivating the centrist political party Sustainable Australia. Led by William Bourke and joined by Dick Smith, the party advocates for a non-discriminatory annual immigration cap at 70,000 persons, down from the current figure of around 200,000 – aimed at a “better, not bigger” Australia.

Join the first IQ2 debate for 2019, “Curb Immigration”. Sydney Town Hall, 26 March. Tickets here.

While the party has been accused of xenophobic bigotry for this stance, their policy makes clear they are not concerned about an immigrant’s religion, culture, or race. Their concern is exclusively for the stress greater numbers of migrants will place on Australia’s infrastructure and environment.

It is a compelling argument. After all, what is the point of the state if not to protect the interests of its citizens?

A Looming Problem

We should be concerned with the needs and interests of our international neighbours, but such concerns must surely be strictly secondary to our own. When our nearest neighbour has approximately ten times our population, squeezed into a landmass twenty five per cent Australia’s size, and ranks 113 places behind us in the Human Development Index, one can be forgiven for believing that limited immigration is critical for ongoing Australian quality of life.

This stance is further bolstered by the highly isolated, and therefore vulnerable nature of Australia’s ecosystem. Australia has the fourth highest level of animal species extinction in the world, with 106 listed as Critically Endangered and significantly more as Endangered or Under Threat.

Much of this is due to habitat loss from human encroachment as suburbs and agricultural lands expand for our increasing needs. The introduction of foreign flora and fauna can be absolutely devastating to these species, greatly facilitated by increased movement between neighbour nations (hence the virtually unparalleled ferocity of our quarantine standards).

While the nation may be a considerable exporter of foodstuffs, many argue Australia is already well over its carrying capacity. Any additional production will be degrading the land and our ability to continue growing food into the future.

The combination of ecological threats and socio-economic pressure makes the argument for limiting immigration to sustainable numbers a powerful one.

But it is absolutely doomed to failure.

Fortress Australia

If the objective of limiting immigration to Australia is both to protect our environment and maintain high quality of life, “Fortress Australia” will fail on both fronts. Why?

Because it does nothing to address the fundamental problem at hand. Unsustainable population growth in a world of limited resources.

Immigration controls may indeed protect both the Australian quality of life and its environment for a time, but without effective strategic intervention, the population burden in neighbouring countries will only continue to grow.

As conditions worsen and resources dwindle, exacerbated by the impacts of anthropogenic climate change, citizens of those overpopulated nations will seek an alternative. What could be more appealing than the enormous, low-density nation with incredibly high quality of life, right next door to them?

If a mere 10 percent of Indonesians (the vast majority of which live on the coast and are exceptionally vulnerable to climate change impacts) decided to attempt the crossing to Australia, we would be confronted by a flotilla equivalent to our entire national population.

The Dilemma

At this point we have one of two choices: suffer through the impact of over a decade’s worth of immigration in one go or commit military action against twenty-five million human beings. Such a choice is a Utilitarian nightmare, an impossible choice between terrible options, with the best possible result still involving massive and sustained suffering for all involved. While ethics can provide us with the tools to make such apocalyptic decisions, the best response by far is to prevent such choices from emerging at all.

Population growth is a real and tangible threat to the quality of life for all human beings on the planet, and like all great strategic threats, can only be solved by proactively engaging in its entirety – not just its symptoms.

Significant progress has been made thus far through programs that promote contraception and female reproductive rights. There is a strong correlation between nations with lower income inequality and population growth, indicating that economic equity can also contribute towards the stabilisation of population growth. This is illustrated by the decreasing fertility rates in most developed nations like Australia, the UK and particularly Japan.

Cause and Effect

The addressing of aggravating factors such as climate change – a problem overwhelmingly caused by developed nations such as Australia, both historically and currently through our export of brown coal– and continued good-faith collaboration with these developing nations to establish renewable energy production, will greatly assist to prevent a crisis occurring.

When concepts such as immigration limitations seek to protect our nation by addressing the symptoms, we are better served by asking how the problem can be solved from its root.

Gordon Young is an ethicist, principal of Ethilogical Consulting and lecturer in professional ethics at RMIT University’s School of Design.

MOST POPULAR

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

ArticleBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Oliver Jacques 15 JAN 2019

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Australia’s two biggest states are moving in opposite directions when it comes to adoption. While New South Wales is accused of tearing families apart, is Victoria right to deny children a voice?

A new stolen generation is coming to you soon.

Or so you would think if you read the reaction to recent NSW reforms aimed at making adoption easier.

NSW Parliament has passed new laws placing a two year time limit on a child staying in foster care. After this time, the state can pursue adoption if a child can’t safely return home, even if birth parents don’t agree.

Critical articles across media raised the spectre of another stolen generation.

An open letter signed by 60 community groups said the NSW Government was “on a dangerous path to ruining lives and tearing families apart”. Indigenous writer Nayuka Gorrie tweeted, “Adoption without parental consent is kidnapping”.

But should a parent really have the right to block the adoption of the child they neglected?

Laws prohibit journalists from identifying people involved in child protection cases so media coverage rarely includes the views of children, even after they turn 18. The laws exist to protect vulnerable minors, but such voices could add some balance to the debate and explain why NSW is ahead in putting children first.

Foster care crisis

Out-of-home care adoption – where legal parenting rights are transferred from birth parents to foster parents – is extremely rare in Australia. Last year, there were 147 children foster care adoptions. That’s a tiny fraction of the 47,000 Australian children living in out-of-home care.

Previously, kids could be placed in state care simply because they were born to a single mother or an Aboriginal woman.

These days, child protection workers only remove children if their lives are in danger due to repeated abuse or neglect.

While foster care is supposed to be a temporary arrangement, children on average spend 12 years in care, often bouncing from one temporary home to another.

It’s no surprise more than a third of foster children end up homeless soon after leaving care.

Permanent care instead of adoption

While NSW is trying to make adoption easier, Victoria is not. None of the more than 10,000 children in Victorian state care were adopted last year.

Victorian children who can’t return home are placed in ‘permanent care’, where they remain a ward of the state but are housed by the same foster carers until age 18.

Paul McDonald, CEO of Anglicare Victoria, describes permanent care as a “win-win-win” for children, birth parents and foster carers. He argues it provides stability for children without changing their legal status “so dramatically”.

Ignoring children’s voices

Former AFL player Brad Murphy, who grew up in Victorian permanent care, begs to differ. “From a child’s perspective, you don’t always feel secure in permanent care,” he said. “I longed for adoption. I wanted to belong to my foster parents, I wanted the same surname.”

Victoria didn’t allow him to be adopted by his loving foster carers because his birth father wouldn’t provide consent.

Murphy believes the Victoria Government should give children a say. “When I was 3 years old, I was calling my foster carer ‘Mum’, as I do now at age 33. I always knew what I wanted”.

The other problem with denying children an adoption choice is they continue to belong to the state. “Government were making all the decisions in my life. And like everything with government, it’s never done quickly,” Murphy said.

He often missed out on school camps and excursions because bureaucrats didn’t sign off permission.

Brad was placed in foster care at 16 months of age. Soon after, his mother ‘did a runner’ to Western Australia. His father was in jail for most of his childhood.

“I was never going back to my birth parents. If birth parents don’t make any effort to change their ways, why should the child suffer any longer?”

Case for reform

There are other parents, though, who want to change their ways but support is scarce. Housing, counselling and rehab facilities across Australia are lacking for low income families.

Some argue we should devote more resources toward keeping vulnerable families together, rather than promoting adoption reform.

There is no reason why we can’t do both. Help families where change is possible, but give children a choice when it’s not.

Though separating children from birth parents can prove traumatic, so is constant abuse. Some kids are terrified of their parents and want stability and the feeling of belonging with their new family.

In NSW, caseworkers must ask children what they want, if they’re old enough to understand. Prospective adoptive parents must educate kids about their history and culture. Birth parents can remain connected to children when it’s safe and in the child’s interests.

Overseas studies show adopted children have better life outcomes than those who remain in long term foster care.

Adoption won’t work for everyone, but it could benefit many kids.

Those criticising NSW reforms should also ask the Victorian government why it continues to deny children the basic human right to be heard.

Are you facing an ethical dilemma? We can help make things easier. Our Ethi-call service is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Oliver Jacques is a freelance journalist and writer.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

BY Oliver Jacques

Oliver Jacques is a freelance writer and tutor based in Griffith, NSW. His writing has appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, The Guardian, ABC, SBS, Daily Telegraph, Herald Sun, Eureaka Street and The Shovel. He has a Masters Degree in Public Policy at ANU; a graduate certificate in journalism at UTS; and has completed courses in copywriting and search engine optimisation at the Australian Writers Centre.

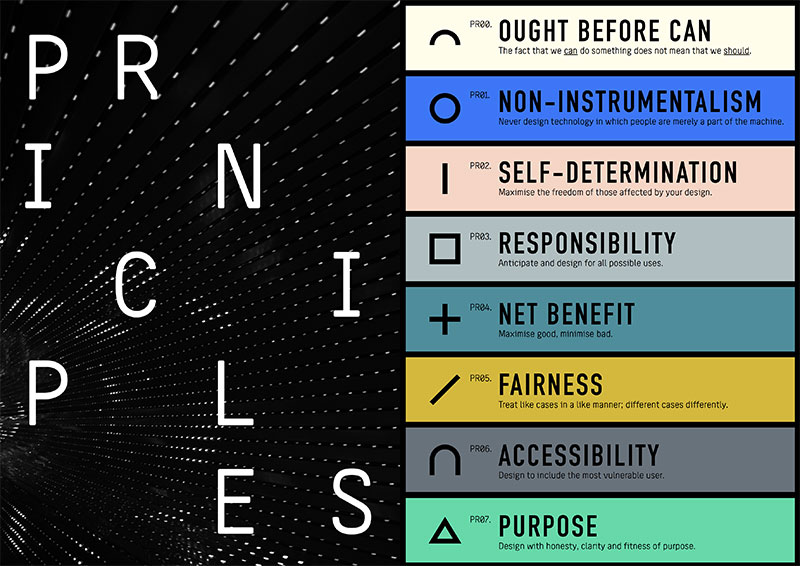

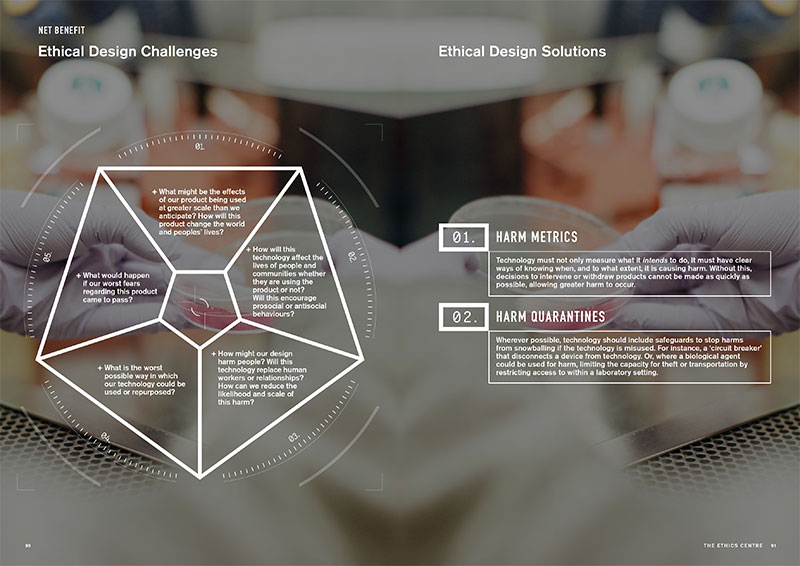

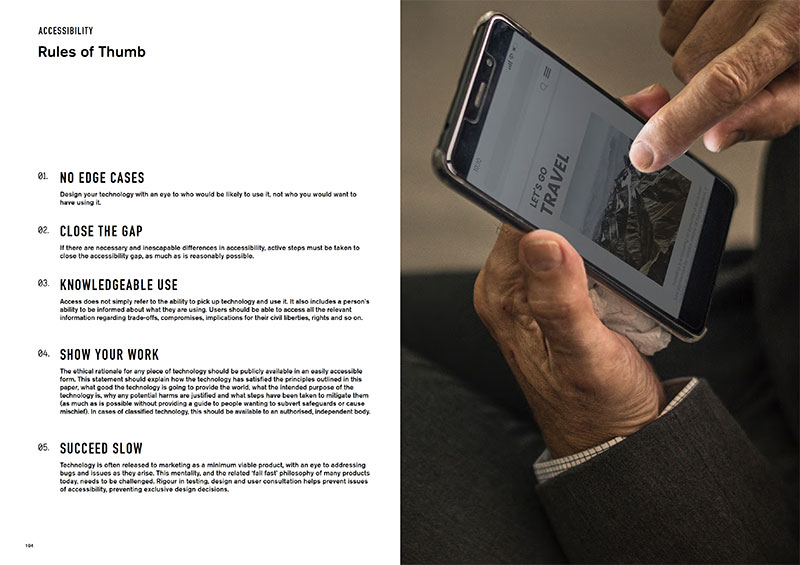

Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology

Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology

Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology

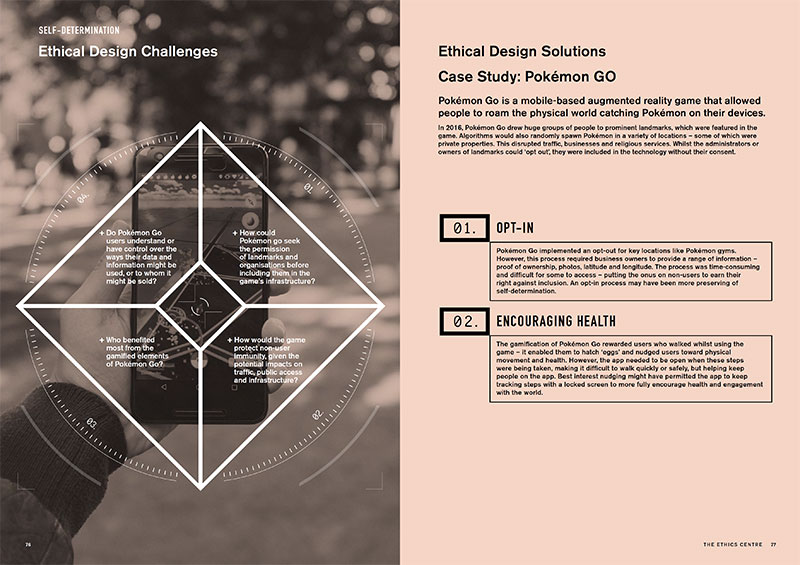

Learn the principles you need to consider when designing ethical technology, how to balance the intentions of design and use, and the rules of thumb to prevent ethical missteps. Understand how to break down some of the biggest challenges and explore a new way of thinking for creating purpose-based design.

You’re responsible for what you design – make sure you build something good. Whether you are editing a genome, building a driverless car or writing a social media algorithm, this report offers the knowledge and tools to do so ethically. From Facebook to a brand new start-up, the responsibility begins with you. In this guide we offer key principles to help guide ethical technology creation and management.

"Technology seems to be at the heart of more and more ethical crises. So many of the ethical scandals we’re seeing in the technology sector are happening because people aren’t well-equipped to take a holistic view of the ethical landscape."

DR MATTHEW BEARD

WHATS INSIDE?

What is ethics + ethical theories

Techno-ethical myths

The value of ethical frameworks

Rules of thumb to embed ethics in design

Case studies + ethical breakdowns

Core ethical design principles

Design challenges + solutions

The future of ethical technology

Whats inside the guide?

AUTHORS

Authors

Dr Matt Beard

is a moral philosopher with an academic background in applied and military ethics. He has taught philosophy and ethics at university for several years, during which time he has been published widely in academic journals, book chapters and spoken at national and international conferences. Matt’s has advised the Australian Army on military ethics including technology design. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement, recognising his “prolific contribution to public philosophy”. He regularly appears on television, radio, online and in print.

Dr Simon Longstaff

has been Executive Director of The Ethics Centre for over 25 years, working across business, government and society. He has a PhD in philosophy from Cambridge University, is a Fellow of CPA Australia and of the Royal Society of NSW, and in June 2016 was appointed an Honorary Professor at ANU – based at the National Centre for Indigenous Studies. Simon co-founded the Festival of Dangerous Ideas and played a pivotal role in establishing both the industry-led Banking and Finance Oath and ethics classes in primary schools. He was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2013.

DOWNLOAD A COPY

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

Ethics programs work in practise

Ethics programs work in practise

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre ethics 19 DEC 2018

New research released today reveals that organisations with clear ethics programs are more likely to be seen as responsible in their business practises by their employees.

The new survey, undertaken by The Institute of Business Ethics (IBE) in partnership with our team at The Ethics Centre (TEC) found that the majority of Australian employees are aware that their organisations have each of the building blocks of an ethics program; a code of ethics, training, and a ‘speak up’ line.

“Ethics at Work” was launched to The Ethics Alliance members this morning through an intimate panel discussion that explored the implications of the findings, featuring Philippa Foster Back of IBE, John Neil and Cris Parker of TEC and Jill Reich of Uniting.

The survey reveals that awareness of ethics programs positively impact how employees feel their company deals with stakeholders. Those with an ethics program are significantly more likely to feel that their organisation acts responsibly in business dealings, at 84 percent. This compares to less than half of those without an ethics program (49 percent). There was one counter-intuitive result where 42 percent agreed their line manager rewards employees who get good results even if it’s through questionable practises.

We’ve spent the last 30 years working with individual organisations to establish ethical frameworks, and worked with many major organisations in recovery from ethical failure. The impact of clear lived values and principles at all levels of an organisation is tremendous, and instrumental to a positive, supportive culture.

The survey also illuminated the role managers play in upholding behaviours within the workplace. Managers were more likely than non-managers to view their organisation positively, both in engagement with stakeholders (77 percent vs 71 percent), and in application of social policy (75 percent vs 67 percent).

It further identifies pressures felt and attitudes toward management positions:

- Managers are more likely to feel pressure to compromise their ethical standards than those not in a management position (by nine percent)

- They were also much more likely to have lenient views toward charging personal entertainment as expenses and using company petrol for mileage

- Employees who have felt pressure to compromise their ethical standards were also more likely to feel their manager failed to promote/reward ethical behaviour (43 percent).

At an employee level, almost one in four reported awareness of misconduct in the workplace, yet worryingly only one in three of those workers decided to speak up.

Of those who have experienced misconduct at work, the most common types were bullying and harassment (41 percent), inappropriate or unethical treatment of people (39 percent) and misreporting of working hours (32 percent).

In addition, more than one in ten (13 percent) have felt pressured to compromise their ethical standards in the workplace.

The Ethics Centre, and our membership program The Ethics Alliance are committed to raising the ethical standards of business in Australia. To find out more about our work visit www.ethics.org.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What is all this content doing to us?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY ethics

'Vice' movie is a wake up call for democracy

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

America has sold a unique brand of exceptionalism.

Some say no modern nation surpasses its military, economic, scientific and cultural prowess. Prominent Americans revere their country as an “empire of liberty”, a “shining city on a hill”, the “last best hope on Earth,” and the “leader of the free world”.

These enduring paeans are an apparent result of America’s political philosophy. By privileging individual freedom for every citizen, the American finds themselves in a unique position all of the time: whenever they choose to do something, they exercise a political right.

This choice has come to be sacred. Vice is about the lengths a self-proclaimed patriot will go to protect it.

When director Adam McKay’s film The Big Short earned him an Oscar for screenwriting, audiences discovered the former SNL comic’s hidden skill – turning concepts that usually made people feel bored or stupid, engaging and funny.

It’s our luck that after the tenth anniversary of 2008 financial crisis, and one month after George H. W. Bush’s funeral, his next target of irreverence would be the shadowy figure of Dick Cheney.

Far from a hagiography, Vice – carried seamlessly by an unrecognisable lead in Christian Bale and a cuttingly ambitious Amy Adams as his wife Lynne – seems an unambiguous condemnation of the Bush-Cheney administration, an ancestor of today’s American right.

This is no typical biopic.

There are no sweeping landscapes and sombre confessionals in red-curtained studios, nor any attempt to feign journalistic objectivity. No off-screen interviewer neatly ties the narrative together and the fourth wall is broken in the first ten minutes.

Absurdity, characters addressing the viewer directly, and thick visual metaphors give Viceits unique personality (wait till you see the scene with the heart). McKay wants you to know he is speaking directly to you. This isn’t a squared off paragraph confined to history books. It is what shaped our present.

Make no mistake: just because it’s opinionated doesn’t mean it isn’t well researched. McKay told the New York Times that the movie encompassed “five decades of Cheney’s life, 200 locations and more than 150 speaking parts”. According to him, a more measured, less confrontational tone wouldn’t have suited the OTT political circus we live in now. “Why be subtle anymore?”

While a conservative backlash is to be expected, this Cheney is no bloodless monster. He’s human. An idealist. His tender love for his daughters and unquestioning devotion to his wife are the same qualities that bond him to the bawdy Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell), and the ranks of a post-Watergate GOP.

He’s a creature of a slower, sweeter time: honed by long scenes of fly-fishing and the vast plains of Wyoming. McKay contrasts this with the energetic, M&M crunching Bush, played by a chameleon-like Sam Rockwell.

Cheney watches and waits. And watches and waits. He leaves no trace. And he is in it for the long haul.

At its core, Vice is a story about democracy. It is a warning that the halls of power rarely grant wishes without demanding a sacrifice, and too often this sacrifice begins with stripping the humanity of the powerless. It is about the special accomplishment of the individual who advances into public life when retreating into privacy is the easiest and most natural thing to do.

It is an admission that envy, chronic discontent and loneliness are intrinsic to democracy, but that its expansive collectivism are how to combat it. It’s all of this, and a demand to keep paying attention.

In his letters, Alexis de Tocqueville speaks of his ambition “to point out if possible to men what to do to escape tyranny and debasement in becoming democratic.”

Philosopher Alexandre Lefebvre offers the following:

“He [Tocqueville] seems to say that tyranny and debasement are part and parcel of becoming democratic. But… [it] works the other way around as well: that in becoming democratic – that is, in becoming properly democratic, democratic in the right way – we can hope to escape the new kinds of tyranny and debasement that democracy brings about…

For as Tocqueville exhorts himself in an unpublished note, we must “use Democracy to moderate Democracy. It is the only path open to salvation to us.”

McKay, and Cheney, would agree.

Vice is released in movie theatres 26 December 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 DEC 2018

Sometimes, good people do bad things. The last year confirmed this. Banks, schools, universities, the military, religious institutions – it seems 2018 left no sector unshaken.

These are the sorts of issues we confront every day at The Ethics Centre. In our reviews and confidential advice we have seen similar patterns repeat over and over again.

Yes, bad apples may exist, but we find ethical issues arise from bad cultures. And even our most trusted institutions, perhaps unwittingly, foster bad behaviour.

That’s why we have an important job. With your support we help society understand why ethical failures happen and provide safeguards lest they repeat.

As The Ethics Centre approaches its 30th birthday, we’d love to say we’re no longer needed. We hoped to bring ethics to the centre of everyday life and think we’ve made a small dent into that task. But there’s no point pretending there’s not a long way to go.

We thank you for supporting us and believing in us and are proud to share the highlights of another busy year with you.

If you’re short on time to read the full report now (and we’d really love you to take a look some time at what a small organisation like ours can achieve), here are seven highlights we’re particularly proud of:

• We launched The Ethics Alliance. A community of organisations unified by the desire to lead, inspire and shape the future of how we do business. In one year, 37 companies have benefited from the innovative tools that help staff at all levels make better decisions.

• We published a paper on public trust and the legitimacy of our institutions. Our conversations with regulators, investors, business leaders and community groups, revealed a sharp decline in the trust of our major institutions. We identify the agenda they need to in order to maintain public trust and contribute meaningfully to the common good.

• We ramped up Ethi-call. Calls to our free, independent, national helpline increased by 74 per cent this year. That’s even more people to benefit from impartial, private guidance from our highly trained ethical counsellors.

• We reviewed the culture of Australian cricket. When the ball-tampering scandal hit the world stage, Cricket Australia asked us to investigate. We uncovered a culture of ambition, arrogance, and control, where “winning at all costs” indicted administrators and players alike.

•We released a guide to designing ethical tech. Technology is transforming the way we experience reality. The need to make sure we don’t sacrifice ethics for growth is more pressing than ever. We propose eight principles to guide the development of all new technologies before they hit the market. You can download it here.

•We redesigned the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. FODI was created to facilitate courageous public conversation. The Ethics Centre and UNSW’s Centre for Ideas collaborated to untether the festival and produce a bold and necessary world-class cultural event. Every session sold out.

• We grew our tenth year of IQ2. We doubled the number of live attendees and tripled the student base showing audiences are more intelligent and hungry for diverse ideas than they are often given credit for. We welcomed a new sponsor Australian Ethical whose values align with our own. There’s never been a better time to support smart, civic, public debate.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Are diversity and inclusion the bedrock of a sound culture?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

Climate change. Nuclear war. Artificial intelligence. A new pandemic.

According to the non-profit organisation 80,000 Hours, these are the greatest threats to humanity today. Yet the big movie studios have been calling it for decades and were pondering the ethics behind these threats long ago.

1. Planet of the Apes (1968)

Seeing Charlie Heston scream in despair at a shattered Statue of Liberty still spooks the most apathetic viewer. And it’s as shocking a warning against nuclear weapons now as it was in the middle of the Cold War 50 years ago.

In Planet of the Apes, humans are being hunted. The primates they once experimented on have grown into intelligent, complex, political creatures. Humanity has regressed into primitive vermin to either be killed outright, enslaved, or used in scientific experiments. The strict ape hierarchy demands utility over compassion, holding a mirror up to the same vices that led humanity to destruction.

—————

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

When a survey of living computer science researchers shows half think there’s a greater than 50 percent chance of “high-level machine intelligence” – one that reaches then exceeds human capabilities – it’s right to be concerned.

2001: A Space Odyssey begins with a jaunty trip to Jupiter. An optimistic team is led aboard by HAL 9000, the ship’s computer, but begin to suspect there’s more to the trip than they’ve been told.

After all, there are two sides to the utilitarian coin. What is murder to us is just programming to a robot.

—————

3. The Matrix (1999)

If reality is a simulation by super intelligent sentient machines, what does any self-respecting hacker do? Start a rebellion.

The Matrix goes even further than 2001: A Space Odyssey. Here, the machines are Descartes’ evil demon, unsatisfied with just killing us. Instead, they mine us for energy to survive, and keep us subservient on a diet of virtual reality. A world of love, work, boring parties, and paying bills occupy us while they use us as slaves.

The point of tension in The Matrix centres around the theory of Plato’s Cave. If you know what everyone is experiencing is an illusion, should you tell them?

—————

4. 28 Days Later (2002)

28 Days Later paints a bleak picture of a world unprepared to deal with the effects of an aggressive pandemic. And it’s not as unbelievable as it may seem. According to 80,000 Hours, the money invested into pandemic research isn’t nearly as much as we need.

From HIV-AIDS, Ebola, and Zika, we’ve seen countries drag their feet over who pays to contain one, or struggle to move people and supplies to where they’re needed.

“When you’re in the middle of a crisis and you have to ask for money”, says Dr. Beth Cameron at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, “you’re already too late”.

—————

5. Children of Men (2006)

What is arguably more important than any of these things is hope. And that’s what our last movie recommendation is about.

After two decades of unexplained female infertility, war, and anarchy, human civilisation is on the brink of collapse. Civil servant Theo Faron has lost all hope as the last generation of his species. Then he meets Kee – an illegal immigrant and the first woman to be pregnant in eighteen years.

The hope for a better future, for a future that is more just and more compassionate, adds intangible meaning to our struggles today. It becomes reasonable to struggle, to suffer, and even to die for this kind of hope.

What makes the hope of today different is that we are now closer to “hypotheticals” than we have ever been.

Are we prepared to turn this hope into action? Effective altruism offers one way to find out.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 12 DEC 2018

Ask just about any parent what they want for their children and they’ll give you roughly the same answers: we want our kids to be happy, healthy and – perhaps most importantly – good.

For many parents, the goal is to raise children who are better than they are, contribute positively to the world around them, challenge cruelty, injustice and ignorance in the world and make a positive difference in other people’s lives.

Basically, what they’re wanting is that their kids grow up to be ethical people. So, if that’s what so many of us want, it’s worth understanding exactly what ethics is and how we might light the ethical spark in the next generation.

Ethics is a branch of philosophy – it asks questions about the nature of goodness, what makes something right and wrong, and what makes life worth living. As a branch of philosophy, it also leaves no stone unturned. It interrogates any and every claim about what’s right, what’s wrong and what’s ‘normal’.

Whenever we make a choice, we change the world in some small way. Before us are a whole bunch of different possible worlds – it’s up to us to decide which one we’ll turn into reality. Ethics helps us make sure we’re choosing the best of those possible worlds, but it takes practice to do it well.

That means if we’re going to help our kids be ethical people, we need to model ethical thinking in our homes and classrooms, on sports fields and video games and wherever kids are making decisions.

But how do we do it? Here are a few tried and true techniques the ABC’s Short & Curly team have used over the last few years.

1. Don’t be afraid to say ‘I don’t know’

It can be scary to say “I don’t know” – especially when we’re having a conversation with kids. As adults, we’re supposed to have all the answers, right? The problem is, sometimes we don’t. And neither do the young people we’re talking to.

The more we pretend we know it all, the more self-conscious others feel about engaging us in a real conversation, or worse – disagreeing with us! Philosophers use discussions and debate as a team activity – we use disagreement and criticism as a way to work together to find out what’s true.

What’s more, our beliefs about how the world works are often conditioned on what we’ve learned or been told is normal. What we know about fairness, honesty or whatever the topic is might not be the final answer – it could be conditioned by norms and beliefs we’ve been conditioned to believe, even if they don’t hold up to close analysis.

2. Be imaginative

Martha Nussbaum, one of the world’s pre-eminent philosophers, says “you can’t really change the heart without telling a story.” We’re narrative creatures – we’ve always used parables, fables, literature and film as ways of understanding the world around us.

Philosophers have tested their ideas through thought experiments and hypotheticals throughout time. They’re super weird, but they make for great road-trip fodder or dinner table debates.

Ethical reflection demands imagination. It requires us to be able to understand experiences we haven’t lived through and to empathise with people who might be radically different to us.

The next time you’re reading a book or watching a movie with your young one, that’s a moment for reflection. Did those characters do the right thing? How do you think that person felt? Would it have been OK if they’d broken that promise?

3. Don’t shut down a question

Some of our favourite one liners are actually really good ways of undermining ethical conversations. “Everybody does it”, “because I said so” and “you’ll understand when you’re older” are good examples. They rely on authority, tradition or experience as ways to cut off what might be a more productive conversation.

Sometimes, there’s not time for an ethical discussion, but rather than shutting it off with a one-liner, make a commitment to talk about it in more detail later, when you’ve got more time to explain yourself.

4. Question your assumptions

Our minds love telling stories – and we hate plot holes. If we don’t have the full story, we’ll often fill in the gaps with assumptions or inferences that don’t capture the full picture. Ethical conversations work best when they start by questioning what we think we know for sure. Are we starting our discussion on a good foundation?

5. Be curious and research

As well as checking our assumptions, ethics requires us to be curious and informed about the world around us. As much as many philosophers would beg to differ, we can’t understand the world from an armchair.

We need to do some research and uncover relevant facts. Bonus – while you’re doing some research together, you might be able to work together to understand the difference between a fact and an opinion, spot dodgy sources or filter out fake news.

6. Listen to and test your emotional responses

Our emotions are an important part of the way we make judgements, but they can sometimes run wild and lead us astray. Just because we find something disgusting, offensive or hurtful, doesn’t make it wrong. And just because we find something pleasant, fun or funny doesn’t mean it’s OK.

Add “yuck” and “yum” to your list of banned arguments – just because something makes you feel squeamish doesn’t make it bad. Listen to your emotions, but get curious about them – they need to be tested like everything else.

One final note: these tips won’t guarantee a kid won’t do the wrong thing sometimes – like all of us. But it will help you have a shared language for communicating, in a meaningful way, why what they did was wrong.

We all make judgements – it’s part of who we are – ethics helps us build the skills and character to ensure we’re making those judgements in ways that are alive to the world around us and the people within it. And like any skill, it’s easier to master if you start young.

The Short & Curly Guide to Life

What makes something good or bad?

Why are things the way they are? How come it’s so hard to work out the right thing to do? The Short & Curly Guide to Life is an imaginative look at some of life’s biggest and trickiest questions. Figuring out what’s right is way more fun than you think!

Short & Curly Guide to Life is on sale at book stores around Australia and via major online retailers. You can also tune into the ABC Radio podcast, Short & Curly, here.

Matt Beard is the resident philosopher on the ABC Podcast Short & Curly, and the author of The Short & Curly Guide to Life (Penguin Random House). Find him on Twitter @matthewtbeard

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

If you’ve ever pondered the meaning of existence or questioned your purpose in life, you’ve partaken in existentialist philosophy.

It would be hard to find someone who hasn’t asked themselves the big questions. What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? Why do I exist? For thousands of years, these questions were happily answered by the belief your purpose in life was assigned prior to your creation. The existentialists, however, disagreed.

Existentialism is the philosophical belief we are each responsible for creating purpose or meaning in our own lives. Our individual purpose and meaning is not given to us by Gods, governments, teachers or other authorities.

In order to fully understand the thinking that underpins existentialism, we must first explore the idea it contradicts – essentialism.

Essentialism

Essentialism was founded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle who posited everything had an essence, including us. An essence is “a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential for a thing to be what it is”. A book’s essence, for example, is its pages. It could have pictures or words or be blank, be paperback or hardcover, tell a fictional story or provide factual information. Without pages though, it would cease to be a book. Aristotle claimed essence was created prior to existence. For people, this means we’re born with a predetermined purpose.

This idea seems to imply, whether you’re aware of it or not, that your purpose in life has been determined prior to your birth. And as you live your life, the decisions you make on a daily basis are contributing to your ultimate purpose, whatever that happens to be.

This was an immensely popular belief for thousands of years and gave considerable weight to religious thought that placed emphasis on an omnipotent God who created each being with a predetermined plan in mind.

If you agreed with this thinking, then you really didn’t have to challenge the meaning of life or search for your purpose. Your God already provided it for you.

Existence precedes essence

While philosophers including Søren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche questioned essentialism in the 19th century, existentialism was popularised by Jean-Paul Sartre in the mid-20th century following the horrific events of World War II.

As people questioned how something as catastrophically terrible as the Holocaust could have a predetermined purpose, existentialism provided a possible answer that perhaps it is the individual who determines their essence, not an omnipotent being.

The existentialist movement asked, “What if we exist first?”

At the time it was a revolutionary thought. You were created as a blank slate, tabula rasa, and it is up to you to discover your life’s purpose or meaning.

While not necessarily atheist, existentialists believe there is no divine intervention, fate or outside forces actively pushing you in particular directions. Every decision you make is yours. You create your own purpose through your actions.

The burden of too much freedom

This personal responsibility to shape your own life’s meaning carries significant anxiety-inducing weight. Many of us experience the so-called existential crisis where we find ourselves questioning our choices, career, relationships and the point of it all. We have so many options. How do we pick the right ones to create a meaningful and fulfilling life?

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does” – John-Paul Sartre

Freedom is usually presented positively but Sartre posed that your level of freedom is so great it’s “painful”. To fully comprehend your freedom, you have to accept that only you are responsible for creating or failing to create your personal purpose. Without rules or order to guide you, you have so much choice that freedom is overwhelming.

The absurd

Life can be silly. But this isn’t quite what existentialists mean when they talk about the absurd. They define absurdity as the search for answers in an answerless world. It’s the idea of being born into a meaningless place that then requires you to make meaning.

The absurd posits there is no one truth, no inherent rules or guidelines. This means you have to develop your own moral code to live by. Sartre cautioned looking to authority for guidance and answers because no one has them and there is no one truth.

Living authentically and bad faith

Coined by Sartre, the phrase “living authentically” means to live with the understanding of your responsibility to control your freedom despite the absurd. Any purpose or meaning in your life is created by you.

If you choose to live by someone else’s rules, be that anywhere between religion and the wishes of your parents, then you are refusing to accept the absurd. Sartre named this refusal “bad faith”, as you are choosing to live by someone else’s definition of meaning and purpose – not your own.

So, what’s the meaning of life?

If you’re now thinking like an existentialist, then the answer to this question is both elementary and infinitely complex. You have the answer, you just have to own it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 10 DEC 2018

Whether you’re a tearer, a folder, a scruncher, or a chucker, there’s nothing like opening a wrapped gift that’s especially suited to you.

Amid the hugs and backslaps it’s hard to say who it’s more satisfying for – the giver or the receiver.

But when little Millie gets the new PlayStation while Amir’s staring at his plastic water gun, the thin film of politeness peels away. We don’t just wonder why we have the gifts we do. We wonder how much they cost.

This holiday season, we’re exploring the ethical dimensions of splurging on gifts. Are there unspoken rules for those with deeper pockets? Is it killing the spirit of generosity to peer at the price tag? Or is keeping mum about money letting us pretend we don’t owe things to each other all the time?

Christmas conundrums? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you navigate any ethical minefields this holiday season.

There are so many different kinds of purposes tied to gift giving on Christmas, or any large celebration. We like to think of these sorts of gifts as intrinsically good, making them different from bribes given for personal gain.

For some, gifts are an informal way to foster love and support in mutual relationships. They encourage closeness and dependencies between social circles to reveal links our individualism tends to hide.

They’re known to shape our moral character and encourage selfless generosity, even to remove feelings of emotional debt that have accumulated throughout the year. Though we speak of gifts as just ways to “show love and appreciation”, our reasons are often more layered than that.

This doesn’t have to be self-indulgent navel-gazing. Examining the purpose of a gift matters because it encourages us to consider if that special, one-of-a-kind purchase is the only way to fulfil it. What duties or consequences should you consider before making that jump?

The duties of gifting

If you are feeling the end of year pinch, you have a duty to yourself to make sure the gift giving season doesn’t put you into financial strife. But if that conflicts with the duty to be fair to your friends and family, ask yourself what matters more. After all, gifts are often an exchange, and appreciating someone’s thoughtfulness can come with offering a similarly tasteful gift of your own.

If the gift is for a friend or peer, we might worry about setting an expectation or precedent we can’t fulfil. If it’s for someone who would struggle to fork out a similar amount of money for a gift, would this leave them feeling uncomfortably tied to you? And if you want to spread the holiday cheer, this leaves your pool of lucky recipients fairly limited.

Nor can the growing consciousness around our impact on the environment be ignored. Are these gifts worth the cost to landfills, unethical supply chains, and our collective duty to preserve the health of the land we live on?

But let’s not dwell on the negative. There are heaps of positive consequences too. Don’t forget the good that comes from making the people around you feel extra special and appreciated. If you struggle with miserliness, or excessive penny pinching, this could be a win-win way to encourage generosity in you, and make someone else very happy. It’s always worth thinking of how your actions reflect your character.

When all is said and done, the holidays are a time to rest. The softening pleasures of food, drink, company and play don’t have to get in the way of a well examined life. In fact, slowing down our frenetic, demanding lives to allow time to recuperate may be just what we need most: the modest admission that we cannot do everything perfectly. Good enough is good enough.

That’s the spirit!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Explainer

Relationships