Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Scepticism is an attitude that treats every claim to truth as up for debate.

Religion, philosophy, science, history, psychology – generally, sceptics believe every source of knowledge has its limits, and it’s up to us to figure out what those are.

Sometimes confused with cynicism, a general suspicion of people and their motives, ethical scepticism is about questioning if something is right just because others say it is. If not, what will make it so?

Scepticism has played a crucial role in refining our basic understandings of ourselves and the world we live in. It is behind how we know everything is made of atoms, time isn’t linear, and that since Earth is a sphere, it’s quicker for planes to fly towards either pole instead of in a straight line.

Ancient ideas

In Ancient Greece, some sceptics went so far as to argue since nothing can claim truth it’s best to suspend judgement as long as possible. This enjoyed a revival in 17th century Europe, prompting one of the Western canon’s most famous philosophers, René Descartes, to mount a forceful critique. But before doing so, he wanted to argue for scepticism in as holistic a fashion as possible.

Descartes wanted to prove certain truths were innate and could not be contested. To do so, he started to pick out every claim to truth he could think of – including how we see the world – and challenge it.

For Descartes, perception was unreliable. You might think the world around you is real because you can experience it through your senses, but how do you know you’re not dreaming? After all, dreams certainly feel real when you’re in them. For a little modern twist, who’s to say you’re not a brain in a vat connected up to a supercomputer, living in a virtual reality uploaded into your buzzing synapses?

This line of thinking led Descartes to question his own existence. In the midst of a deeply valuable intellectual freak out, he eventually came to realise an irrefutable claim – his doubting proved he was thinking. From here, he deduced that ‘if I think’, then I exist.

“I think, therefore I am.”

It’s the quote you see plastered over t-shirts, mugs, and advertising for schools and universities. In Latin it reads, “Cogito ergo sum”.

Through a process of elimination, Descartes created a system of verifying truth claims through deduction and logic. He promoted this and quiet reflection as a way of living and came to be known as a rationalist.

The arrival of the empiricist

In the 18th century, a powerful case was made against rationalism by David Hume, an empiricist. Hume was sceptical of logical deduction’s ability to direct how people live and see the world. According to Hume, all claims to truth arise from experiences, custom and habit – not reason.

If we followed Descartes’ argument to its conclusion and assessed every single claim to truth logically, we wouldn’t be able to function. Navigating throughout the world requires a degree of trust based on past experiences. We don’t know for sure that the ground beneath us will stay solid. But considering it generally does, we trust (through inductive reasoning) that it will stay that way.

Hume argued memories and “passions” always, eventually, overrule reason. We are not what we think, but what we experience.

Perhaps you don’t question the nature of existence at the level of Descartes, but on some level, we are all sceptics. Scepticism is how we figure out who to confide in, what our triggers are, or if the next wellness fad is worth trying out. Acknowledging how powerful our habits and emotions are is key to recognising when we’re tempted to overlook the facts in favour of how something makes us feel.

But part of being a sceptic is knowing what argument will convince you. Otherwise, it can be tempting to reduce every claim to truth as a challenge to your personal autonomy.

Scepticism, in its best form, has opened up mind-boggling ways of thinking about ourselves and the world around us. Using it to be combative is a shortsighted and corrosive way to undermine the difficult task of living a well examined life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 5 OCT 2018

We sat down with Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018 festival director Danielle Harvey to take peak into the inspirations, motivations and challenges behind creating one of the most confronting and thought-provoking events in Australia.

1. It’s been said FODI was Australia’s first disruptive festival. What is it about the festival that resonates so strongly with audiences?

People want more than a headline. They want to hear more in depth analysis and a range of perspectives. To hear straight from the academics, scientists, researchers and not have it filtered, distorted. A live festival doesn’t get more direct.

2. There are so many different ideas, themes and perspectives out there that matter. How do you narrow it down to land this year’s line up?

A lot of vigorous discussion! Myself and the co-curators are always looking at the next thing that’s going to hit, we’ve been very good at looking at the horizon in past festivals, discussing things like Russia, surrogacy and banking all before a scandal breaks.

We also look to the superstars of the non-fiction world, the academics and researchers doing great work and are great communicators. And we look for a multitude of perspectives, beyond politics. A discussion that involves people from across disciplines, experts in their field that bring to light a focus on a particular aspect and when combined help to show the complex nature of many of our biggest ideas and problems.

3. The festival has been going strong for 9 years now. What gets easier, what doesn’t?

This is my 7th FODI. I feel very lucky to have been able to grow my own understanding of the world in a very public way! The easier and harder is the same – finding great people.

Easier because people around the world know about this festival and we have great alumni and reputation, harder because we’ve presented so many amazing people and so many ideas… I look forward to next year… 10 feels like a good ‘best of’ opportunity!

4. What does it take to be a great festival director?

Curiosity about the world. I’ve curated and created a number of festivals – FODI, Antidote, All About Women, BingeFest and Mardi Gras and they always start about thinking about audiences and what they should be able to see/hear/experience. I am insatiably curious and I love finding connections between things.

5. What’s it like to produce a festival like FODI? What does a typical day look like for you?

Talking. Talking. Appreciating the amazing team around me. (I have the best people who do so much). More talking. Noodling on the internet, reading, watching. Talking some more. (I talk to people from all different walks of life to hear what is interesting them).

6. What do you think sets the 2018 festival apart from recent years?

The island! The opportunity to fully immerse yourself in a program sans distractions. It’s all about the ideas and engaging with them deeply this year. The opportunity to include more large scale art and theatre has also made this a very different festival. We have the space and time to do these things on Cockatoo.

7. Why the move to Cockatoo Island and what are the challenges or surprises in setting up a festival in the middle of Sydney Harbour?

Everything has to be barged on! That’s the biggest challenge. It’s an amazing site, full of potential, but it is an island with no real infrastructure. The history of the place is incredibly evocative and any time we go there we are amazed at this little gem sitting on our doorstep. It’s a great place to let your mind and feet wander (and wonder)!

8. Finally, we have to ask. Which bit are you most to looking forward to? What are the must-see events?

That is tough, it will all be great! I am really looking forward to Chuck Klosterman, to Rukmini Callimachi and of course Stephen Fry! I think the ‘Too Dangerous’ panel will also be full of excellent take-aways.

I am also excited about the two art installations – ‘Submission’ and ‘The Hand That Wields It’ these installations are excellent opportunities to see ideas represented in a different way rather than via a talk.

Everything you need to know: The Festival Of Dangerous Ideas 2018

From sex robots to sex clowns, to tying yourself up in lies and rope, this year’s festival on 3 – 4 November takes you beyond the hype and deep into the issues that confront and divide us.

Embrace the festival experience on Cockatoo Island with one-day or full weekend passes. All passes include free return ferry transport.

Featured speakers include ex Westboro Baptist Church follower Megan Phelps-Roper, conservative historian Niall Ferguson; iconoclast Germaine Greer; rock star of AI Toby Walsh; micro-dosing advocate Ayelet Waldman; pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman; academic and activist Mick Dodson and so many more!

To crown FODI 2018, join Stephen Fry at a special event at Sydney Town Hall, where he will deliver an oration on the lost art of fabulous disagreement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2018

The Ethics Centre (TEC) is thrilled to be announced as a finalist for Training and Education Business of the year in the Optus My Business Awards for the second year running.

It’s an honour to be a finalist again after we were awarded winner of the category last year for our Ethical Professional Program.

The inaugural Optus My Business Award program reported record submission numbers this year, with leading SME’s across Australia vying for recognition in the 35 prestigious award categories.

This year we are proud to be finalists for our Ethi-call Counsellor Training Program (ECTP), completed by individuals hoping to become a volunteer Ethi-call Counsellor.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to anyone needing help to make their way through tough ethical challenges in their life. Made possible only through the support of volunteers who provide this service, this year we increased our capacity to deliver sessions by 300% through the ECTP program.

The eighteen-month program blends a diverse mix of learning techniques, resources and support networks to prepare students both emotionally and technically to handle the diverse range of calls received by the Ethi-call helpline.

Through an integrated learning program that bridges theoretical ethics with empathic counselling skills and practical delivery of the Ethi-call model, students are supported to develop the skills and understanding to develop as counsellors.

When asked what makes the ECTP so special, a recent graduate remarked:

“[TEC] Invest a great deal in this new Ethics Counselling Training Program to ensure callers to the Ethi-call service – who usually have extremely complex and often upsetting moral dilemmas in their personal and professional lives – receive the absolute best quality of service possible”

Program Manager Peta Andreone explained:

“Our duty is to ensure counsellors are capable to handle any type of call, and that our callers not only have access to a freely available service, but one that delivers the highest standard of care”

“Counsellors undergo intensive training to be registered through TEC, and participate in ongoing professional development to maintain their credentials annually”

The key innovation to the Ethi-call Counsellor Training Program is the Ethi-call Counselling Model, a working tool that has been developed and refined over the past 27 years.

An independent panel of judges will now review finalist submissions before deciding on this year’s awarded entries. Winners will be announced at a black-tie gala dinner on Friday, 9 November at The Star in Sydney.

Congratulations and good-luck to our fellow finalists in the Training and Education Business of the Year:

Code Camp

Engage & Grow

First Home Buyer Buddy

KICKBrick

Liberate eLearning

PD Training

STEM Punks

TCP Training

The Financial Fox

If you would like to train as an Ethi-call counsellor, send an expression of interested to counselling@ethics.org.au.

If you are facing a difficult ethical dilemma or decision, make a free appointment for a private conversation with an Ethi-call counsellor here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2018

It’s no exaggeration to say the ideas of Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith (1723—1790) have shaped the world we live in.

By providing the core intellectual framework in defence of free markets, he positioned human liberty and dignity at the centre of trade and money – all for the common good.

Adam Smith, the pioneer

In the 18thcentury, the race to colonise as many resource rich places as possible meant powerful countries were often at war. Companies which added to the wealth of empires were protected by grateful governments, creating trade monopolies that seemed impossible to dismantle. This was the heyday of mercantilism.

Smith noticed how these actions created concentrations of wealth, benefiting the wealthy while the labour class struggled to survive. His first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, argued that the virtues of sympathy and reciprocity could tame greed.

His second, The Wealth of Nations, was about promoting a new way of approaching wealth that was as lucrative as it was just. The approach Smith adopted was multifaceted: economic, defensive, legal, and moral.

Smith argued that countries were competing for the wrong thing. Wealth wasn’t to be found in commodities like gold and silver. It resided in human labour and ingenuity. Smith encouraged countries that would normally look externally for wealth, suppressing the labour class and enslaving others, to look internally instead.

If the labour class could have the freedom to pick their job, all the while knowing the government would leave the money they made well alone, why wouldn’t they work hard at it? They would produce goods and services of even higher quality, and the government could buy these and trade them with each other. Everyone wins.

Collaboration would mean countries wouldn’t need to waste money on defence and war. They could save and accumulate capital, and invest that into better machinery, freeing people to work more productively. The labour class would grow richer, and so would the nation.

Smith stressed that in order for a free market to ensure fair pay for fair work, contracts had to be honoured, people had to keep their word, and governments mustn’t get into debt or take people’s property. Theft, negligence, mistakes, or irresponsible government spending must to be managed by the rule of law. And in the case of foreign powers, defence.

Thus, for Smith – a free market must rest on a sound ethical foundation. Given this, he argued for moral education of a kind that would lead people to be honourable and behave justly. This included the rich. Smith thought that an appeal to ‘enlightened’ self-interest might lead them to act honourably. By lavishing praise, accolades, and rewards on those who spend their wealth in charity, the rich gain the status and rank they really desire.

Adam Smith, the legacy

Claims of plagiarism, usury, inconsistency, racism, and all else aside, the major complaint directed towards Smith is his concept of the “invisible hand”. His observation that self-interested individuals end up benefiting the common good – that they are “led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention.” – has prompted some critics to label him naïve, idealistic, or even immoral.

The following quotation (misattributed to John Maynard Keynes) sums it up: “Capitalism is the astounding belief that the wickedest of men will do the wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone”. But that plays into the Smith = laissez-faire trap, and ignores the safeguards he proposed against human corruption.

Smith did not think greed was good, saying this removed “the distinction between vice and virtue”, nor did he believe business interests and the public interest necessarily coincide. Instead, his perspective was that market competition forced people to act in ways that benefited others, regardless of their intention. And when it failed to do that, an overarching authority should step in. For Smith, markets have no intrinsic value – they are merely tools for the betterment of life for all.

No doubt the world we live in now is vastly different to pre-Industrial Scotland. Mass media, the Internet, the textile industry, factory farms, surveillance, housing prices, offshore tax havens…much would have seemed strange and unfamiliar to Smith. But his work and legacy leave a lesson in economics, ethics, and politics – all the more prescient in a world where the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

What do boxers, political figures, and that guy who’s addicted to Reddit all have in common?

They’ve probably employed the techniques of stoicism. It’s an ancient Greek philosophy that offers to answer that million dollar question, what is the best life we can live?

Hard work, altruism, prayer or relationships don’t take the top dog spot for the stoic. Instead, they zoom out and divide the world (if you’ll forgive the simplicity) into black and white: what you can control and what you can’t.

It’s the lemonade school of philosophy. The central tenet being:

“When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.”

Stoics believe that everything around us operates according to the law of cause and effect, creating a rational structure of the universe called logos. This structure meant that something as awful as all your worldly possessions sinking into the ocean (Zeno of Cyprus), or as annoying as missing the last bus by a quarter of a minute, don’t make your life any worse. Your life remains as it is, nothing more, nothing less.

If you suffer, you suffer because of the judgements you’ve made about them. The ideal life where that didn’t happen is a fantasy, and there’s no point focusing on it. Just expect that pain, grief, disappointment and injustice are going to happen. It’s what you do in response to them that counts.

This philosophy was founded by said Zeno, who preached the virtues of tolerance and self control on a stone colonnade called the stoa poikile. It’s where stoicism found its name. It flourished in the Roman empire, with one of its most famous students being the emperor himself, Marcus Aurelius. Fragments of his personal writing survive in Meditations, revealing counsel remarkably humble and chastising for a man of his power.

Stoicism on emotion

Emotion presents an opportunity. There’s a reactive, immediate response, like blaming others when you feel ashamed, or panicking when you feel anxious. But there is a better reaction the stoics aim for. It matches the degree of impact, is appropriate for the context, is rationally sound, and in line with a good character.

Being angry at your partner for forgetting to put away the dishes isn’t the same as being angry at an oppressive government for torturing its citizens. But if it’s the emotion you focus on, all your good intentions aren’t guaranteed to stop you from messing up. After all, the red haze is formidable.

By practising this “slow thinking” and making it a habit, you can cultivate the same self discipline to develop virtues like courage and justice. It’s these that will ultimately give your life meaning.

For others, emotions are more like the weather. It rains and it shines, and you just deal with it.

Stoicism assumes that focusing on control and analysing emotion is how virtues are forged. But some critics, including philosopher Martha Nussbaum, say that approach misses a fundamental part of being human. After all, control is transient too. Emotions – loving and caring for someone or something to such an extent that losing it devastates you – doesn’t make you less human. It’s part of being human in the first place.

Other critics say that it leads to apathy, something collective political action can’t afford. Sandy Grant, philosopher at University of Cambridge, says stoicism’s “control fantasy” is ridiculous in our interdependent, globalised world. “It is no longer a matter of ‘What can I control?’ but rather of ‘Given that I, as all others, am implicated, what should I do?”

Controlling emotion to navigate through life cautiously may not be desirable to you. But it is easy to see how channelling stoicism in certain situations can help us manage life’s unfortunate moments – whether they be missing the bus or something more harrowing.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gordon Young 21 SEP 2018

If the last decade of Australian politics has taught us anything it is this: democracy is a deeply flawed system.

Between the leadership spills, minority governments, ministerial scandals, legal corruption, and campaign donations, democracy is leaving more of us disillusioned and distrustful.

And that’s just in Australia.

Overseas, various ‘democratic’ governments have handed us Brexit, Russian election tampering (both domestically and abroad), the near collapse of the Euro, the Chinese Government’s Social Credit scheme, and the potentially soon-to-be-impeached Trump Presidency.

It’s not surprising that many are looking for an alternative system to run the country. Something simpler, more direct. Something efficient and easy.

Something like capitalism.

This may seem absurd on first reading – after all, how can an economic system replace the political governance of an entire nation? But capitalism is more than how we trade goods and services. It spills into a broader socio-economic theory that claims it can better represent people nationally and abroad than democracy ever could. This is known as neoliberalism.

Neoliberals argue that we don’t need to rely on the promises of unaccountable representatives to run the government. We can let competition decide. Just as a free market encourages better products, why don’t we let the free market encourage better governance?

If Bob does a better job fixing your car than Frank, employ Bob and vote for that quality as the standard. Frank either picks up his game or goes out of business. If your neighbouring electorate’s MP does a better job representing you, pay him and vote for his policy. If people value businesses that treat their employees well, those businesses will succeed and others will change their practices to compete.

Where democracy asks you to trust in the honour of your leaders, and only gives you a chance to hold them to account every few years, neoliberalism lets you exercise your choice every single time you spend your money, every single day.

This is far from fantasy thinking. It is this essential idea that drives ideas like ‘small government’, privatisation of state infrastructure, decreasing business taxes, and cutting ‘red tape’ – remove government interference from the system and leave the decisions up to the people themselves.

On paper it is the perfect system of government – a direct democracy where every citizen constantly drives policy based on what they buy and why.

Great, right? Well, only if you’re a fan of feudalism. Because that is what such a system would inevitably produce.

Consider this: within democracy, who is in control? The elected government obviously has the reigns of power during their term (to a frankly frightening degree), but how do they maintain that power?

By being elected, of course. Whether they like it or not, every three to four years they at least have to pretend they care about the needs of the people. In reality it’s hardly as simple as ‘one person, one vote’ – between campaign donations, lobby groups, ‘cash for access’, and good old-fashioned connections, some citizens will always have more power than others – but the fact remains that within democracy, the people in power still need to care about the whims of their citizens.

Now consider this: within this ideal capitalist, neoliberal, vote-with-your-dollar system, who is in control? If you express your interests in this system through your purchases, then power is dispersed based on how much you spend, right?

Who does the most spending? The people with the most money.

Here is the critical question and the sting in tail of the neoliberalism: why should the people in control of such a society, where power is determined by wealth alone, give the slightest damn about you?

Whether sincere or not, democracy requires the decision makers to court all citizens at least every election (and a lot more frequently than that, if they know what’s good for them). But in a purely capitalist society, why would the power-players ever need to consult those without significant wealth, power, or influence?

Even in a democratic world a mere 62 people already own more money than half of the entire world’s population, and exert titanic power upon the world’s markets that no normal citizen can ever hope to challenge.

Remove the political franchise that democracy guarantees every citizen by default, and you remove any and all controls of how those ultra-rich exert the power this wealth grants them.

So while we may criticise democracy for its inefficiencies, and fantasise how much better it would all be if government ‘were run like a business’, such idle complaints miss the key value of democracy – that in granting each and every citizen the inalienable right to an equal vote, none of them can safely be ignored by those who would aspire to power.

Perhaps you believe that the neoliberal utopia would be a better system, and the 1 percent would never decide to relegate the masses back to serfdom. But the fact that such a decision would now depend entirely on their whims, should be enough to terrify any sane citizen.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2018

A wedding day – and all the kerfuffle beforehand – should come with a warning label. Ethical dilemmas ahead.

Decisions like: “Should I even have a wedding?” “Who should I invite?” “How much should I spend?” “Is this day really just about my partner and I?” “Do I have to invite my embarrassing uncle who drinks too much and flirts with the bridesmaids?” It can drive you spare.

Sure, taking the time to work things out won’t mean you know the right thing to do. But it’ll mean the decisions you come to will have been thoughtful and considered.

So if you’re stuck, start with purpose. What do you believe is the purpose of a wedding? And what actions are in line with that?

Purpose

Say a wedding is meant to be a celebration of the life that you two will build together. If that’s true, would you go into debt for that wedding, knowing that some of that future life will be spent paying it off? That answer really depends on you.

Would it make sense to skimp instead? Maybe. But if a celebration to you includes good food, drinks, live music, and cake, is that in line with the purpose of a wedding either?

“Hey,” you might be thinking. “A wedding isn’t about the two of us. It’s about everyone who’s been a part of our lives.” And fair enough! No one can argue with that. But if you’re juggling venue booking dates, your budget, and your dreams of having a week long wedding in Tahiti, remembering your guests and what they’d want can help you narrow it down. Sometimes multiple ceremonies and parties slim down people’s wallets and annual leave. Other times, it makes for a dream come true. You know your guests – and your purpose – best.

Wedding dilemmas splitting you in two? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you see through chiffon to make decisions you can live by.

Duties

These same questions carry over into duties. Maybe you’re deciding who to invite and who not to. Remembering your duty to yourself, your partner, and your guests can all provide different perspectives. If you think the life you two will have together won’t include distant relatives or friends (especially relationships that were difficult or abusive), would it make sense to have them there on your wedding day?

But if you believe you have a duty to these people to invite them – be they family, old friends, or people you just need to invite – you might feel differently. No matter what you decide it’s worth asking, if you want to keep your guests happy and comfortable, would inviting difficult or disruptive people prevent that?

Consequences

These days, people aren’t the only things we’re concerned about. The impact of our weddings on the environment is something we’re much more conscious of. You might have wanted three thousand silver helium balloons on your wedding ever since you were a child, but you also just watched War on Waste and know that balloons end up in the tummies of lots of birds and turtles. Does the benefit outweigh the harm?

A good way to test if you’re cutting yourself too much slack on something you’d judge others for, is to shine it under the sunlight test. Would you still do it if it’d be on the front page of the newspaper tomorrow?

Character

As with anything, it’s worth considering whether it presents you as the type of person you believe you are – and living the values you and your partner share. Does your wedding display qualities you strive toward, like thoughtfulness, fun, and generosity? Or does it paint you as selfish, unprepared, and demanding? If the wedding you and your partner plan are inspired by shared values, chances are you’re on your way to plan a wedding that reflects these aspirations.

A wedding holds a lot of symbolism because of its importance in culture, religion, and history. Of course, it’s also fraught, often for the exact same reasons. If you’re in a “non-traditional” relationship or you disagree with marriage altogether, you might feel stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Does a wedding fit with the kind of person you want to be? Do you feel a sense of duty – to yourself, to your family, to your wider community, to social media, to God – to have a wedding? Do you believe weddings give you something you can’t get anywhere else? What about the specific traditions that make you ask, “Should I even have that?”

Being respectful of weddings and what they symbolise can make you think about how to make it your own.

Oh, and one final thing for anyone reading this. If you aren’t even sure you want to be with your partner, don’t have a wedding. The risk of a painful, humiliating, and expensive mistake is far too high.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2018

If you were born in 1989 or after, you haven’t yet voted in an election that’s seen a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Some point to social media, the online stomping grounds of digital natives, as the cause of this. As Emma Alberici pointed out, Twitter launched in 2006, the year before Kevin ’07 became PM.

Some blame widening political polarisation, of which there is evidence social media plays a crucial role.

If we take a look though, the thing that keeps killing our PMs’ popularity in the polls and party room is climate and energy policy. It sounds completely anodyne until you realise what a deadly assassin it is.

Rudd

Kevin Rudd declared, “Climate change is the great moral challenge of our generation”. This strategic focus on global warming contributed to him defeating John Howard to become Prime Minister in December 2007. As soon as Rudd took office, he cemented his green brand by ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, something his predecessor refused to do.

There were two other major efforts by the Rudd government to address emissions and climate change. The first was the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme(CPRS) led by then environment minister Penny Wong. It was a ‘cap and trade’ system that had bi-partisan support from the Turnbull led opposition party… until Turnbull lost his shadow leadership to Abbott over it. More on this soon.

Then there was the December 2009 United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, officially called COP15 (because it was the fifteenth session of the Conference of Parties). Rudd and Wong attended the summit and worked tirelessly with other nations to create a framework for reducing global energy consumption. But COP15 was unsuccessful in that no legally binding emissions limits were set.

Only a few months later, the CPRS was ditched by the Labor government who saw it would never be legislated due to a lack of support. Rudd was seen as ineffectual on climate change policy, the core issue he championed. His popularity plummeted.

Gillard

Enter Julia Gillard. She took poll position in the Labor party in June 2010 in what will be remembered as the “knifing of Kevin Rudd”.

Ahead of the election she said she would “tackle the challenge of climate change” with investments in renewables. She promised, “There will be no carbon tax under the government I lead”.

Had she known the election would result in the first federal hung parliament since 1940, when Menzies was PM, she may not have uttered those words. Gillard wheeled and dealed to form a minority government with the support of a motley crew – Adam Bandt, a Greens MP from Melbourne, and independents Andrew Wilkie from Hobart, and Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor from regional NSW. The compromises and negotiations required to please this diverse bunch would make passing legislation a challenging process.

To add to a further degree of difficulty, the Greens held the balance of power in the Senate. Gillard suggested they used this to force her hand to introduce the carbon tax. Then Greens leader Bob Brown denied that claim, saying it was a “mutual agreement”. A carbon price was legislated in November 2011 to much controversy.

Abbott went hard on this broken election promise, repeating his phrase “axe the tax” at every opportunity. Gillard became the unpopular one.

Rudd 2.0

Crouching tiger Rudd leapt up from his grassy foreign ministry portfolio and took the prime ministership back in June 2013. This second stint lasted three months until Labor lost the election.

Abbott

Prime Minister Abbott launched a cornerstone energy policy in December 2013 that might be described as the opposite of Labor’s carbon price. Instead of making polluters pay, it offered financial incentives to those that reduced emissions. It was called the Emissions Reduction Fund and was criticised for being “unclear”. The ERF was connected to the Coalition’s Direct Action Plan which they promoted in opposition.

Abbott stayed true to his “axe the tax” slogan and repealed the carbon price in 2014.

As time moved on, the Coalition government did not do well in news polls – they lost 30 in a row at one stage. Turnbull cited this and creating “strong business confidence” when he announced he would challenge the PM for his job.

Turnbull

After a summer of heatwaves and blackouts, Turnbull and environment minister Josh Frydenberg created the National Energy Guarantee. It aimed to ensure Australia had enough reliable energy in market, support both renewables and traditional power sources, and could meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement. Business, wanting certainty, backed the NEG. It was signed off 14 August.

But rumblings within the Coalition party room over the policy exploded into the epic leadership spill we just saw unfold. It was agitated by Abbott who said:

“This is by far the most important issue that the government confronts because this will shape our economy, this will determine our prosperity and the kind of industries we have for decades to come. That’s why this is so important and that’s why any attempt to try to snow this through … would be dead wrong.”

Turnbull tried to negotiate with the conservative MPs of his party on the NEG. When that failed and he saw his leadership was under serious threat, he killed it off himself. Little did he know he would go down with it.

Peter Dutton continued with a leadership challenge. Turnbull stepped back saying he would not contest and would resign no matter what. His supporters Scott Morrison and Julie Bishop stepped up.

Morrison

After a spat over the NEG, Scott Morrison has just won the prime ministership with 45 votes over Dutton’s 40.

Killers

We have a series of energy policies that were killed off with prime minister after prime minister. We are yet to see a policy attract bi-partisan support that aims to deliver reliable energy at lower emissions and affordable prices. And if you’re 29 or younger, you’re yet to vote in an election that will see a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The undeserved doubt of the anti-vaxxer

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 23 AUG 2018

As the Commonwealth Government ponders its response to the Ruddock Religious Freedom Review, it’s worth considering what people of faith may be seeking to preserve and what limits society might justifiably seek to impose.

The term ‘religious freedom’ encompasses a number of distinct but related ideas. At the core, it’s freedom of belief – in a god, gods or a higher realm or being.

Many religions make absolute (and often mutually exclusive) claims to truth, most of which cannot be proven. Religions rely, instead, on acts of faith. Next comes freedom of worship – the freedom to perform, unhindered, the rituals of one’s faith. Then there is the freedom to act in good conscience – to give effect to one’s religious belief in the course of one’s daily life and, as a corollary, not to be forced to act in a manner that would violate one’s sacred obligations. Finally, there is the freedom to proselytise – to teach the tenets of one’s religion to the faithful and to those who might be persuaded.

In a secular, liberal democracy the four types of religious freedom outlined above – to believe, to worship, to act and to proselytise – attract different degrees of liberty. For example, people are generally free to believe whatever takes their fancy, no matter how ill-founded or bizarre. This is not so in all societies. Some theocracies will punish ‘heretics’ for holding unorthodox beliefs. Acting out of belief – in worship, deeds and proselytising – is often subject to some measure of restraint. For example, pious folk are not permitted to set up a pulpit (or equivalent) in the middle of a main road. They are not permitted to beat a woman, even if the teaching of their religion allows (or requires) her chastisement. They are not permitted to let a child die because of a religious objection to life-saving medical procedures. Nor are they able to teach that some people are ‘lesser beings’, lacking intrinsic dignity, simply because of their gender, sexuality, culture, religion, and so on. In other words, there are boundaries set for the expression of religious belief, whatever those beliefs might be.

It is precisely the setting of such ‘boundaries’ that has become a point of contention. Some Australian religious leaders claim they should be exempt from the application of Australian laws that they do not approve, like anti-discrimination legislation. This is nothing new. As it happens, in Australia, a number of religions have long denied the validity of secular law, even to the extent of running parallel legal systems.

The Roman Catholic Church regularly applies Canon Law in cases involving the status of divorcees, the sanctity of the confessional, and so on. The Government of Australia might recognise divorce, but the Church does not. The following text is taken from the official website of the Archdiocese of Sydney: A divorce is a civil act that claims to dissolve a valid marriage. From a civil legal perspective, a marriage existed and was then dissolved. The Catholic Church … does not recognise the ability of the State to dissolve a marriage. An annulment, on the other hand, is an official declaration by a Church Tribunal that what appeared to be a valid marriage was actually not one (i.e, that the marriage was in fact invalid) [my emphasis].

In a similar vein, the Jewish community maintains a separate legal system that oversees the application of Halakhic Law through the operation of special Jewish religious courts called Beth Din. Given the precedents set by Christians and Jews, it’s not surprising that adherents of other faith groups, notably Muslims, are seeking the same rights to apply religious laws within their own courts and to enjoy exemptions from the application of the secular law.

“Fundamental human rights come as a ‘bundle’. They are indivisible.”

Given all of the above, are there any principles that we might draw on when setting the boundaries to religious freedom?

Human rights

Fortunately, the proponents of freedom of religion have provided an excellent starting point for answering this question. It begins with the core of their argument – that freedom of belief (religion) is a fundamental human right. Their claim is well founded. However, those who invoke fundamental human rights cannot ‘cherry pick’ amongst those rights, only defending those that suit their preferences.

Fundamental human rights come as a ‘bundle’. They are indivisible. It follows from this that if people of faith are to assert their claim to religious freedom as a fundamental human right, then the exercise of that freedom should be consistent with the realisation of all other fundamental human rights. Religious freedom is but one. It follows from this that any legislative instrument designed to create a legal right to freedom of religion must circumscribe that right to the extent necessary to ensure that other human rights are not curtailed. For example, a legal right to religious freedom should not authorise violence against another person. Nor should it permit discrimination of a kind that would otherwise be considered unlawful under human rights legislation.

If there is to be Commonwealth legislation, then it should establish an unrestricted right of belief and a rebuttable presumption in favour of acting on those beliefs. The limits to action should be that the conduct (either by word or deed): does not constrain the liberty of another person, does not subject another person to any form of violence, does not deny the intrinsic dignity of another person and does not violate the human rights of another person. Finally, it is essential that as a liberal democracy any Australian legislation specify that the tenets of a religion only apply to those who have freely consented to adopt that religion.

So, what might this look like in practice – say, in relation to same sex marriage now that it is lawful?

Baking cakes

Nobody should be compelled to believe that same sex marriage is ‘moral’. That is a matter of personal belief unrelated to the law. Second, it should be permissible to teach, to members of one’s faith group, and to advocate, more generally, that same sex marriage is immoral (a view I do not hold). The fact that something is legal leaves open the question of its morality. Third, no person should be required to perform a marriage if to do so would violate the dictates of their conscience. Roman Catholic priests refuse to marry heterosexual divorcees. Such marriages are allowed by the state – yet no priest is forced to perform such a marriage because to do so would make them directly complicit is an act their religion forbids. Such an allowance should only extend to those at risk of becoming directly complicit in objectionable acts. For example, such an allowance should not be granted to a religious baker not wanting to provide a wedding cake to a gay couple. Cakes play no direct role in the formalities of a civil marriage. So, unlike a pharmaceutical company that might justifiably object to becoming complicit through the supply of drugs to an executioner, a baker is never going to be complicit in the performance of a marriage. As such, a baker should be bound by law to supply his or her goods on a non-discriminatory basis. Of course, there will always be some who feel obliged to put the requirements of their religion before the law.

To act according to one’s conscience in an honourable choice. But only do this if you are willing to bear the penalty.

Dr Simon Longstaff is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre: www.ethics.org.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The ethical price of political solidarity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2018

We’ve got NEGs, NEMs, and Finkels a-plenty. Here is a cheat sheet for this whole energy debate that’s speeding along like a coal train and undermining Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s authority. Let’s take it from the start…

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – 1992

This Convention marked the first time combating climate change was seen as an international priority. It had near-universal membership, with countries including Australia all committed to curbing greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol was its operative arm (more on this below).

The Kyoto Protocol – December 1997

The Kyoto Protocol is an internationally binding agreement that sets emission reduction targets. It gets its name from the Japanese city it was ratified in and is linked to the aforementioned UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Protocol’s stance is that developed nations should shoulder the burden of reducing emissions because they have been creating the bulk of them for over 150 years of industrial activity. The US refused to sign the Protocol because the two largest CO2 emitters, China and India, were exempt for their “developing” status. When Canada withdrew in 2011, saving the country $14 billion in penalties, it became clear the Kyoto Protocol needed some rethinking.

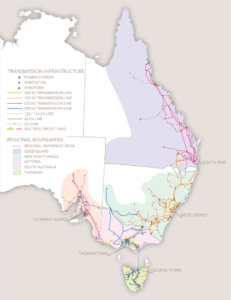

Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) – 1998

Forget the fancy name. This is the grid. And Australia’s National Electricity Market is one of the world’s longest power grids. It connects suppliers and consumers down the entire east and south east coasts of the continent. It spans across six states and territories and hops over the Bass Strait connecting Tasmania. Western Australia and the Northern Territory aren’t connected to the NEM because of distance.

The NEM is made up of more than 300 organisations, including businesses and state government departments, that work to generate, transport and deliver electricity to Australian users. This is no mean feat. Before reliable batteries hit the market, which are still not widely rolled out, electricity has been difficult to store. We’ve needed to continuously generate it to meet our 24/7 demands. The NEM, formally established under the Keating Labor government, is an always operating complex grid.

The Paris Agreement aka the Paris Accord – November 2016

The Paris Agreement attempted to address the oversight of the Kyoto Protocol (that the largest emitters like China and India were exempt) with two fundamental differences – each country sets its own limits and developing countries be supported. The overarching aim of this agreement is to keep global temperatures “well below” an increase of two degrees and attempt to achieve a limit of one and a half degrees above pre-industrial levels (accounting for global population growth which drives demand for energy). Except Australia isn’t tracking well. We’ve already gone past the halfway mark and there’s more than a decade before the 2030 deadline. When US President Donald Trump denounced the Paris Agreement last year, there was concern this would influence other countries to pull out – including Australia. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott suggested we signed up following the US’s lead. But Foreign Minister Julie Bishop rebutted this when she said: “When we signed up to the Paris Agreement it was in the full knowledge it would be an agreement Australia would be held to account for and it wasn’t an aspiration, it was a commitment … Australia plays by the rules — if we sign an agreement, we stick to the agreement.”

The Finkel Review – June 2017

Following the South Australian blackout of 2017 and rapidly increasing electricity costs, people began asking if our country’s entire energy system needs an overhaul. How do we get reliable, cheap energy to a growing population and reduce emissions? Dr Alan Finkel, Australia’s chief scientist, was commissioned by the federal government to review our energy market’s sustainability, environmental impact, and affordability. Here’s what the Review found:

Sustainability:

- A transition to low emission energy needs to be supported by a system-wide grid across the nation.

- Regular regional assessments will provide bespoke approaches to delivering energy to communities that have different needs to cities.

- Energy companies that want to close their power plants should give three years’ notice so other energy options can be built to service consumers.

Affordability:

- A new Energy Security Board (ESB) would deliver the Review’s recommendations, overseeing the monopolised energy market.

Environmental impact:

- Currently, our electricity is mostly generated by fossil fuels (87 percent), producing 35 percent of our total greenhouse gases.

- We’re can’t transition to renewables without a plan.

- A Clean Energy Target (CET), would force electricity companies to provide a set amount of power from “low emissions” generators, like wind and solar. This set amount would be determined by the government.

-

- The government rejected the CET on the basis that it would not do enough to reduce energy prices. This was one out of 50 recommendations posed in the Finkel Review.

ACCC Report – July 2018

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry Report drove home the prices consumers and businesses were paying for electricity were unreasonably high. The market was too concentrated, its charges too confusing, and bad policy decisions by government have been adding significant costs to our electricity bills. The ACCC has backed the National Energy Guarantee, saying it should drive down prices but needs safeguards to ensure large incumbents do not gain more market control.

National Energy Guarantee (NEG)– present 20 August 2018

The NEG was the Turnbull government’s effort to make a national energy policy to deliver reliable, affordable energy and transition from fossil fuels to renewables. It aimed to ‘guarantee’ two obligations from energy retailers:

- To provide sufficient quantities of reliable energy to the market (so no more black outs).

- To meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement (so less coal powered electricity).

It was meant to lower energy prices and increase investment in clean energy generation, including wind, solar, batteries, and other renewables. The NEG is a big deal, not least because it has been threatening Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership. It is the latest in a long line of energy almost-policies. It attempted to do what the carbon tax, emissions intensity scheme, and clean energy target haven’t – integrate climate change targets, reduce energy prices, and improve energy reliability into a single policy with bipartisan support. Ambitious. And it seems to have been ditched by Turnbull because he has been pressured by his own party. Supporters of the NEG feel it is an overdue radical change to address the pressing issues of rising energy bills, unreliable power, and climate change. But its detractors on the left say the NEG is not ambitious enough, and on the right too cavalier because the complexity of the National Energy Market cannot be swiftly replaced.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships