Managing corporate culture

It’s not uncommon these days to hear regulators sounding warnings about culture.

They point out that it’s a crucial role of boards to determine the purpose, values and principles of the company they govern, whilst the CEO and senior management have responsibility for implementing the desired culture. Personnel in human resources, ethics, compliance, and risk functions all have a role to play in embedding values and ethics.

Culture, we hear, has an important role to play in risk management and risk appetite. Weak risk cultures are often the root cause of the most spectacular governance failures. Firms lacking good corporate culture will fail investors and stakeholders.

“Trust, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder,” says John Price, Commissioner of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC). “If consumers don’t like the way a firm has behaved, they can take their business elsewhere and tell everyone about it through the wonders of social media. Loss of reputation due to poor conduct destroys value in a firm. Even more challenging is that poor conduct may be technically within the law, but still have negative impact on a firm’s reputation.

“The possible loss of trust and confidence is a key business risk. If the conduct of a firm genuinely reflects ‘doing the right thing,’ this mitigates conduct risk and will be rewarded with longevity, customer loyalty, and a sustainable business.”

All very well, we hear you say: but how does a company manage culture? What does good culture even look like? By what standard do we measure it or assess it? How do you shift from the culture you’ve got today to the culture you aspire to for the future?

The Ethics Centre has been exploring this subject for many years, developing frameworks and methodologies for measuring and improving culture along the way. We’ve played a significant advocacy role as well, arguing for boards to accept responsibility for setting and maintaining the culture standard in the organisations they govern.

The Ethics Centre recently partnered with the Governance Institute, the Institute of Internal Auditors and Chartered Accountants Australia to produce Managing Culture – A Good Practice Guide. This publication sets out to define culture and explores challenges in identifying, monitoring and driving culture, including organisational change programs. The guide also explores the importance of embedding culture and the nature of the board’s role in evaluating and overseeing culture.

Research has shown that companies that have a good culture perform better than companies that do not. The Guide outlines how each group in an organisation can contribute to a good culture, the first step of which is to create an ethical framework that provides guidance on decisions and an appropriate ‘tone from the top’.

While having an integrated governance and risk management framework is important, unless an organisation establishes a culture that promotes risk awareness into everything it does, it is unlikely to achieve its objectives. Governance and risk management must be at the core of an organisation’s culture.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Market logic can’t survive a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson’s B Team

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Bladerunner, Westworld and sexbot suffering

Bladerunner, Westworld and sexbot suffering

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 12 DEC 2017

The sexbots and robo-soldiers we’re creating today take Bladerunner and Westworld out of the science fiction genre. Kym Middleton looks at what those texts reveal on how we should treat humanlike robots.

It’s certain: lifelike humanoid robots are on the way.

With guarantees of Terminator-esque soldiers by 2050, we can no longer relegate lifelike robots to science fiction. Add this to everyday artificial intelligence like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Google Home and it’s easy to see an android future.

The porn industry could beat the arms trade to it. Realistic looking sex robots are being developed with the same AI technology that remembers what pizza you like to order – although it’s years away from being indistinguishable from people, as this CNET interview with sexbot Harmony shows.

Like the replicants of Bladerunner we first met in 1982 and the robot “hosts” of HBO’s remake of the 1973 film Westworld, these androids we’re making require us to answer a big ethical question. How are we to treat walking, talking robots that are capable of reasoning and look just like people?

Can they suffer?

If we apply the thinking of Australian philosopher Peter Singer to the question of how we treat androids, the answer lies in their capacity to suffer. In making his case for the ethical consideration of animals, Singer quotes Jeremy Bentham:

“The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

An artificially intelligent, humanlike robot that walks, talks and reasons is just that – artificial. They will be designed to mimic suffering. Take away the genuine experience of physical and emotional pain and pleasure and we have an inanimate thing that only looks like a person (although the word ‘inanimate’ doesn’t seem an entirely appropriate adjective for lifelike robots).

We’re already starting to see the first androids like this. They are, at this point, basically smartphones in the form of human beings. I don’t know about you, but I don’t anthropomorphise my phone. Putting aside wastefulness, it’s easy to make the case you should be able to smash it up if you want.

But can you (spoiler) sit comfortably and watch the human-shaped robot Dolores Abernathy be beaten, dragged away and raped by the Man in Black in Westworld without having an empathetic reaction? She screams and kicks and cries like any person in trauma would. Even if robot Dolores can’t experience distress and suffering, she certainly appears to. The robot is wired to display pain and viewers are wired to have a strong emotional reaction to such a scene. And most of us will – to an actress, playing a robot, in a fictional TV series.

Let’s move back to reality. Let’s face it, some people will want to do bad things to commercially available robots – especially sexbots. That’s the whole premise of the Westworld theme park, a now not so sci-fi setting where people can act out sexual, violent, and psychological fantasies on android subjects without consequences. Are you okay with that becoming reality? What if the robots looked like children?

The virtue ethicist’s approach to human behaviour is to act with an ideal character, to do right because that’s what good people do. In time, doing the virtuous thing will be habit, a natural default position because you internalise it. The virtue ethicist is not going to be okay with the Man in Black’s treatment of Dolores. Good people don’t have dark fantasies to act out on fake humans.

The utilitarian approach to ethical decisions depends on what results in the most good for the largest amount of people. Making androids available for abuse could be a case for community safety. If dark desires can be satiated with robots, actual assaults on people could reduce. (In presenting this argument, I’m not proposing this is scientifically proven or that it’s my view.) This logic has led to debates on whether virtual child porn should be tolerated.

The deontologist on the other hand is a rule follower so unless androids have legal protections or childlike sexbots are banned in their jurisdiction, they are unlikely to hold a person who mistreats one in ill regard. If it’s your property, do whatever you’re allowed to do with it.

Consciousness

Of course, (another spoiler) the robots of Westworld and Bladerunner are conscious. They think and feel and many believe themselves to be human. They experience real anguish. Singer’s case for the ethical treatment of animals relies on this sentience and can be applied here.

But can we create conscious beings – deliberately or unwittingly? If we really do design a new intelligent android species, complete with emotions and desires that motivate them to act for themselves, then give them the capacity to suffer and make conscientious choices, we have a strong case for affording robot rights.

This is not exactly something we’re comfortable with. Animals don’t enjoy anything remotely close to human rights. It is difficult seeing us treat man made machines with the same level of respect we demand for ourselves.

Why even AI?

As is often with matters of the future, humanlike robots bring up all sorts of fascinating ethical questions. Today they’re no longer fun hypotheticals. It is important stuff we need to work out.

Let’s assume for now we can’t develop the free thinking and feeling replicants of Bladerunner and hosts of Westworld. We still have to consider how our creation and treatment of androids reflects on us. What purpose – other than sexbots and soldiers – will we make them for? What features will we design into a robot that is so lifelike it masterfully mimics a human? Can we avoid designing our own biases into these new humanoids? How will they impact our behaviour? How will they change our workplaces and societies? How do we prevent them from being exploited for terrible things?

Maybe Elon Musk is right to be cautious about AI. But if we were “summoning the demon”, it’s the one inside us that’ll be the cause of our unease.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Hype and hypocrisy: The high ethical cost of NFTs

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The “good enough” ethical setting for self-driving cars

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Philosophy had a big moment in 20th century Europe. Christian mysticism? Not so much.

Meet Simone Weil (1909—1943) – French philosopher, political activist, Christian mystic and enfant terrible. Described by John Berger as a “heretical theologian”, Albert Camus as “the only great spirit of our times”, and André Weil (her brother) as “the greatest pain in the arse for rectors and school directors”, Weil was – and remains – one of philosophy’s more divisive characters

Uprootedness

According to Weil, post-World War II France was adrift in a deep malaise she called uprootedness. She argued France’s lack of connectedness to its past, its land, and its community had culminated in its defeat by Germany. Her solution? To find spirituality in work.

This would look different in city and country. In urban areas, treating uprootedness meant finding a motivation for work other than money.

Weil admitted that for low income and unemployed adults in war ravaged France, this would be impossible. Instead, she focused on their children. Reviving the original Tour de France, encouraging apprenticeships, and bringing joy back into study were her recommendations. This way, work could be intriguing and compelling. Even “lit up by poetry”.

For those in the country, uprootedness looked like boredom and an indifference to the land. Optional studies of science, religion, more apprenticeships and cultivating a strong need to own land was essential. To remember the water cycle, photosynthesis and Biblical shepherds while working could only invoke awe, Weil surmised. Even the fatigue of labour would turn poetic.

Her vision for reform extended to French colonialism. This was a source of deep shame for Weil, admitting that she could not meet “an Indochinese person, an Algerian, a Moroccan, without wanting to ask his forgiveness”. She saw uprootedness most acutely in those whose homelands had been invaded. It was also a clear example of the cyclical nature of uprootedness: for the fiercest invaders were uprooted people uprooting others.

Attention over will

The spirituality of academic work was just as important to Weil. In practice, this looked like attention. She defined attention as the capacity to hold different ideas without judgement. In doing so, the student would be able to engage with ideas and slowly land on an answer.

She argued that when a student is motivated by good grades or social ranking, they arrest their development of attention and lose all joy in learning. Instead, they pounce on any semblance of answer or solution, even if half-formed or incorrect, to seem impressive. Social media, anyone?

According to Weil, true knowledge could not be willed. Instead, the student should put their efforts into making sure they paid attention when it arrived.

Weil believed humanity’s search for truth was their search for nearness to God or Christ. If God or Christ was the source of ‘Truth’, every new piece of knowledge or fact learned would refer to them. Therefore, in each student’s instance of unmixed attention – to a geometry problem, a line of poetry, or a cry for help from someone in need – was an opportunity for spiritual transformation.

This detachment from social mores and movement away from the ego characterised her mysticism. It makes a lot of sense then, that Weil considered the height of attention to be prayer.

Obligations over rights

Weil believed that justice was concerned with obligations, not rights. One of her criticisms of political parties lay in their language of rights, calling it “a shrill nagging of claims and counter-claims”.

Justice, for Weil, consisted of making sure no harm is done to one another. Weil asserted that when the man who is hurt cries ‘why are you hurting me?’ he invokes the spirit of love and attention. When the second man cries ‘why has he got more than I have?’ his due becomes conditional on power and demand.

The obligation of justice, Weil noted, is fundamentally unconditional. It is eternal and based upon a duty to the very nature of humanity. In a sense, what Weil is describing is the Golden Rule, found in every major religious tradition and every strand of moral philosophy – to treat others as you would like to be treated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Social media is a moral trap

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2017

TIME Magazine’s announcement comes amid a storm of reckoning with sexual harassment and abuse charges in power centres worldwide. The courageous victims who, over the past few months, surfaced and made public their experiences of sexual harassment have sparked a social movement – typified in the hashtag #MeToo.

One of the features of the numerous sexual harassment claims that have been made public is the number of victims that have come forward after the first allegations have surfaced. Women, many of whom have suffered in silence for a considerable period of time, all of a sudden have found their voice.

As an outsider not involved in these incidents, this pattern of behaviour might be difficult to comprehend. Surely victims would speak up and take their concerns to the appropriate authorities? Unfortunately, we are very poor at judging how we would behave when we are placed in difficult, stressful situations, as previous research has found.

How we imagine we would respond in hypothetical situations as an outsider differs significantly to how we would respond in reality – we are very poor at appreciating how the situation can influence our conduct.

In 2001, Julie Woodzicka and Marianne LaFrance asked 197 women how they would respond in a job interview if a man aged in his thirties asked them the following questions: “Do you have a boyfriend?”, “Do people find you desirable?” and “Do you think women should be required to wear bras at work?” Over two-thirds said they would refuse to answer at least one of the questions whilst sixteen of the participants said they would get up and leave.

When Woodzicka and LaFrance placed 25 women in this situation (with an actor playing the role of the interviewer), the results were vastly different. None of the women refused to answer the questions or left the interview.

In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

And there are many reasons why people remain silent. Three of the most common are fear, futility and loyalty – we fear consequences, we surmise that speaking up is futile because no action will be taken, or, as strange as it might sound, we feel a sense of loyalty to the perpetrator or our team.

There are a variety of dynamics that can cause people to reach these conclusions. The most common is power. In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

In these types of situations, it is easy to see how the victim can lose their sense of agency and feel disempowered. They might feel that even if they did speak up, nobody would believe their story. The mere thought of challenging such a “highly respected” individual is too daunting. Worse yet, their career would be irreparably damaged. Perhaps, by keeping quiet, they could get the break they need and put the experience behind them.

A second dynamic at play is what psychologists refer to as pluralistic ignorance. First conceived in the 1930s, it proposes that the silence of people within a group promotes a misguided belief of what group members are really thinking and feeling.

In the case of sexual harassment, when victims remain silent they create the illusion that the abuse is not widespread. Each victim feels they are isolated and suffering alone, further increasing the likelihood that they will repress their feelings.

By speaking out, women have shifted the norms surrounding sexual assault. Behaviour which may have been tolerated only a few years (perhaps months) ago is now out of bounds.

But as the events of the past few weeks have demonstrated, the norms promoting silence can crumble very quickly. People who suppress their feelings can find their voice as others around them break their silence. As U.S. legal scholar Cass Sunstein recently wrote in the Harvard Law Review Blog, as norms are revised, “what was once unsayable is said, and what was once unthinkable is done.”

And this is exactly what has happened over the past few months. Both perpetrators and victims alike are now reflecting on past indiscretions and questioning whether boundaries were crossed.

Only time will tell whether the shift in norms is permanent or fleeting. As is always the case with changes in social attitudes, this will be determined by a myriad of factors. The law plays a role but as the events of the past few months have demonstrated it is not as important as one might think.

Among other things, it will require the continued courage of victims. But perhaps more importantly it will require men, especially those who are in positions of power and respected members of our communities and institutions, to role model where the balance resides between extreme prudery at one end, and disgusting lechery on the other.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

An angry electorate

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

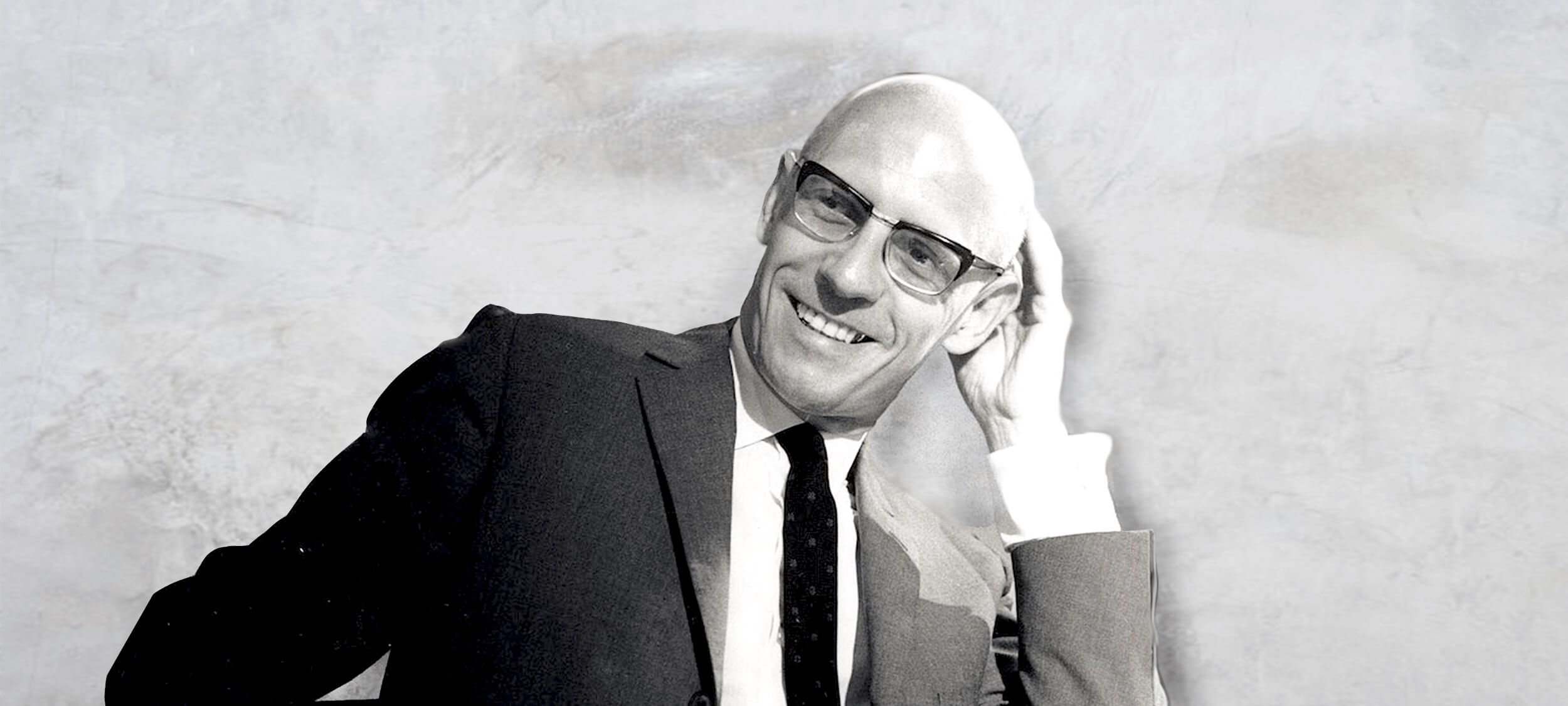

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Ethics Alliance: Why now?

After almost thirty years of existence, The Ethics Centre has chosen this particular time to establish The Ethics Alliance. Why the Alliance, and why now?

I’ve heard it suggested that the Alliance is a necessary response to a period of history in which our trust in institutions – including banks, governments and the media – has dropped to a new low point. Some may see it as an opportunity for organisations to restore their battered reputations.

Others may see the Alliance a little more generously, as a community of like-minded organisations with a common commitment to good business practice. A collaborative effort to raise the standards of good business behaviour. A source of insights and tools that will enable better culture to emerge.

While low levels of trust certainly form part of the context within which The Ethics Alliance is emerging, we believe the root cause of our current malaise is something far more significant: the fact that we are on the edge of a transformation that will change our society in ways every bit as profound as those caused by the First Industrial Revolution.

The Ethics Alliance has a clear function. It is a mechanism for developing collective insight and practical measures that will support its members to manage this historic transition. The Alliance will enable companies – and the leaders who work in them – to harness change for the benefit of employees, customers and shareholders alike. The ultimate beneficiary will be the society in which we all live.

We are already seeing clues as to the general shape of the coming changes. Many of these are the product of scientific and technological innovation. Artificial Intelligence and robotics (including nano-fabrication by 3D printers) will displace vast numbers of people from employment. New jobs may be created – but there are very few credible plans in place to ensure the necessary transition will be just or orderly.

The upheaval in employment will be accompanied by a revolution in medicine. Gene editing (using the ‘cut & paste’ functions of CRISPR), pharmaco-genomics, the use of stem cells to regenerate organs and a myriad of other developments will see a startling increase in the lifespan of those who can afford these therapies.

The resulting seismic shift in demography will challenge all of our assumptions about what makes for a worthwhile life, about the status of long-established social institutions, about sources of value and so on. What kind of economy will be needed to support such a society? What is the role of the market, of government, of civil society?

These questions will create new practical challenges within every workplace. If one of the key responsibilities of business leaders is to anticipate and plan for the emerging future and creating organisations which are fit for purpose, then there is much to discuss. Scientists, economists, engineers and lawyers can help us to know what we could do in response to issues of this kind. But only ethics can help us decide what we should do.

We believe business, professional and government organisations not only have a responsibility to help meet the challenges of the future – they also have the capacity to do so.

These matters are not just for governments to solve. Few, if any, organisations will be able to address such ‘civilisational’ challenges alone. Aggregating the resources, energy and insights of members of The Ethics Alliance will achieve outcomes that individual organisations could never achieve on their own.

The Ethics Alliance will also provide practical tools to its members – building their capacity to make better decisions – even in conditions of uncertainty. And it will support innovation. The Ethics Alliance has been designed as a safe place for testing the boundaries of what might be possible.

Society may have lost a little of its faith in government and business lately, and that’s something we should all be concerned about. We believe business, professional and government organisations not only have a responsibility to help meet the challenges of the future – they also have the capacity to do so.

These same organisations cannot afford to ignore these issues or mismanage their response. This is not just about managing risk. It is also about learning how to harvest the dividends of progress without compromising the future.

In that sense, The Ethics Alliance is not so much a response, as a product of the times in which we live.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics in Procurement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Can there be culture without contact?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Big Thinker: Bill Mollison

Bill Mollison (1928—2016) was an Australian ecologist and the ‘father of permaculture’, a type of agricultural design and practice he created, named and taught.

Having co-wrote Permaculture One with his student and colleague David Holmgrem, Mollison later founded the Permaculture Institute of Tasmania and taught his Permaculture Design Course and Certificate (PDCC) all around the world.

Today, his philosophy has reached millions. His commitment to ethics brings philosophy back into the marketplace and onto the farm – down to its earthworms and well-tilled soil.

What is permaculture?

Permaculture is an ethical design framework for sustainable farming. It combines traditional farming methods of Indigenous and Aboriginal communities with renewable technologies and low-energy materials. Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer and creator of “Do-nothing Farming”, is cited as another influence on Mollison’s farming philosophy.

Mollison believed that farming monocultures, like corn, or wheat, was unsustainable. Instead, he called for ‘food forests’ – a varied collection of plant and tree species that support equally as diverse animal life.

Like a delicate structure of checks and balances, the little relationships formed in such an ecosystem would keep it self-sufficient. According to Mollison, once complete, a successful permaculture design wouldn’t need any human touch at all.

What’s wrong with what we’ve got now?

Because monocultures are more efficient, fast and easy to harvest, they’ve been the go-to for industrial farming. But, according to Mollison, their future is limited, with no means to reproduce the same healthy ecosystem it profits from. In fact, it’s often expected to meet the surplus demand of nations that already have enough food.

Mollison considered this form of agriculture as unethical, self-destructive and “temporary”. Rather than people being relied on to provide yields, he wanted to make us another part of the agricultural web. No more, no less.

This, along with permaculture’s three core ethics (earth care, people care and fair share), would transform how plants, animals and humans all interact with each other. People – not just farmers – would turn into active stewards of the earth. The social and economic needs of interdependent communities would be satisfied and looked after, with global surplus distributed to those most in need.

Some people find his views noble, but unrealistic. Indeed, his repositioning of farming as political might be novel. But applying ethics to fulfil basic needs of food and shelter, to Mollison, is essential:

“The greatest change we need to make is from consumption to production, even if on a small scale, in our own gardens. If only 10% of us can do this, there is enough for everyone. Hence the futility of revolutionaries who have no gardens, who depend on the very system they attack, and who produce words and bullets, not food and shelter.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

Flaky arguments for shark culling lack bite

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

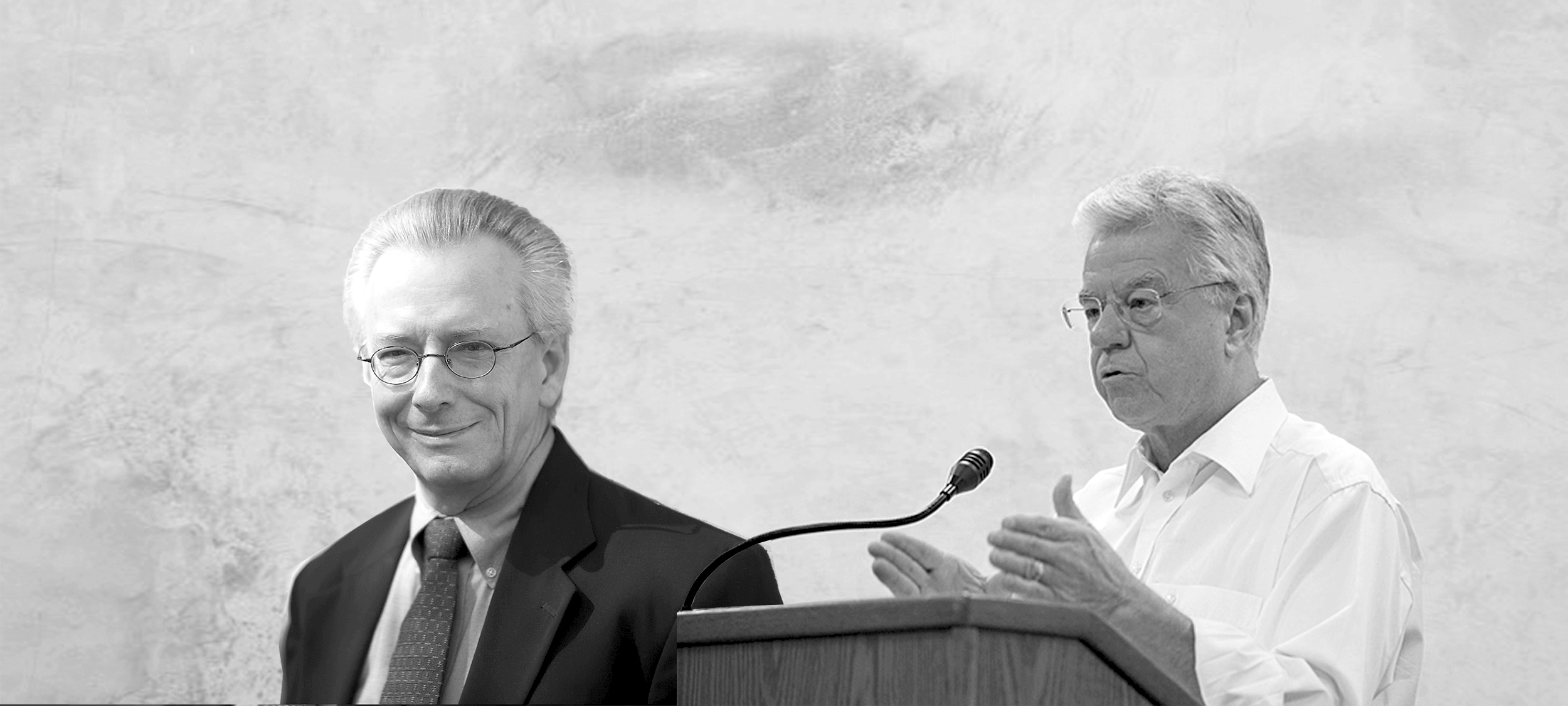

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 1 DEC 2017

Thomas L Beauchamp (1939—present) and James F Childress (1940—present) are American philosophers, best known for their work in medical ethics. Their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics was first published in 1985, where it quickly became a must read for medical students, researchers, and academics.

Written in the wake of some horrific biomedical experiments – most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where hundreds of rural black men, their partners, and subsequent children were infected or died from treatable syphilis – Principles of Biomedical Ethics aimed to identify healthcare’s “common morality”. These are its four principles:

- Respect for autonomy

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

These principles are often in tension with one another, but all healthcare workers and researchers need to factor each into their reflections on what to do in a situation.

Respect for autonomy

Philosophers usually talk about autonomy as a fact of human existence. We are responsible for what we do and ultimately any action we take is the product of our own choice. Recognising this basic freedom at the heart of humanity is a starting point for Beauchamp and Childress.

By itself, the idea human beings are free and in control of themselves isn’t especially interesting. But in a healthcare setting, where patients are often vulnerable and surrounded by experts, it is easy for a patient’s autonomous decision to be disrespected.

Beauchamp and Childress were writing at a time when the expertise of doctors meant they often took extreme measures in doing what they had decided was in the best interests of their patient. They adopted a paternalistic approach, treating their patients like uninformed children rather than autonomous, capable adults. This went as far as performing involuntary sterilisations. In one widely discussed court case in bioethics, Madrigal v Quillian, ten Latina women in the US successfully sued after doctors performed hysterectomies on them without their informed consent.

Legally speaking, the women in Madrigal v Quillian had provided consent. However, Beauchamp and Childress explain clearly why the kind of consent they provided isn’t adequate. The women – who spoke Spanish as a first language – were all being given emergency caesareans. They were asked to sign consent forms written in English which empowered doctors to do what they deemed medically necessary.

In doing so, they weren’t being given the ability to exercise their autonomy. The consent they provided was essentially meaningless.

To address this issue, Beauchamp and Childress encourage us to think about autonomy as creating both ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ duties. The negative duty influences what we must not do: “autonomous actions should not be subject to controlling constraints by others”, they write. But positively, autonomy also requires “respectful treatment in disclosing information” so people can make their own decisions.

Respecting autonomy isn’t just about waiting for someone to give you the OK. It’s about empowering their decision making so you’re confident they’re as free as possible under the circumstances.

Nonmaleficence: ‘first do no harm’

The origins of medical ethics lie in the Hippocratic Oath, which although it includes a lot of different ideas, is often condensed to ‘first do no harm’. This principle, which captures what Beauchamp and Childress mean by non-maleficence, seems sensible on one level and almost impossible to do in practice on another.

Medicine routinely involves doing things most people would consider harmful. Surgeons cut people open, doctors write prescriptions for medicines with a range of side effects, researchers give sick people experimental drugs – the list goes on. If the first thing you did in medicine was to do no harm, it’s hard to see what you might do second.

This is clearly too broad a definition of harm to be useful. Instead, Beauchamp and Childress provide some helpful nuance, suggesting in practice, ‘first do no harm’ means avoiding anything which is unnecessarily or unjustifiably harmful. All medicine has some risk. The relevant question is whether the level of harm is proportionate to the good it might achieve and whether there are other procedures that might achieve the same result without causing as much harm.

Beneficence: do as much good as you can

Some people have suggested Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles are three principles. They suggest beneficence and non-maleficence are two sides of the same coin.

Beneficence refers to acts of kindness, charity and altruism. A beneficent person does more than the bare minimum. In a medical context, this means not only ensuring you don’t treat a patient badly but ensuring you treat them well.

The applications of beneficence in healthcare are wide reaching. On an individual level, beneficence will require doctors to be compassionate, empathetic and sensitive in their ‘bedside manner’. On a larger level, beneficence can determine how a national health system approaches a problem like organ donation – making it an ‘opt out’ instead of ‘opt in’ system.

The principle of beneficence can often clash with the principle of autonomy. If a patient hasn’t consented to a procedure which could be in their best interests, what should a doctor do?

Beauchamp and Childress think autonomy can only be violated in the most extreme circumstances: when there is risk of serious and preventable harm, the benefits of a procedure outweigh the risks and the path of action empowers autonomy as much as possible whilst still administering treatment.

However, given the administration of medical procedures without consent can result in legal charges of assault or battery in Australia, there is clearly still debate around how to best balance these two principles.

Justice: distribute health resources fairly

Healthcare often operates with limited resources. As much as we would like to treat everyone, sometimes there aren’t enough beds, doctors, nurses or medications to go around. Justice is the principle that helps us determine who gets priority in these cases.

However, rather than providing their own theory, Beauchamp and Childress pointed out the various different philosophical theories of justice in circulation. They observe how resources are distributed will depend on which theory of justice a society subscribes to.

For example, a consequentialist approach to justice will distribute resources in the way that generates the best outcomes or most happiness. This might mean leaving an elderly patient with no dependents to die in order to save a parent with young children.

By contrast, they suggest someone like John Rawls would want the access to health resources to be allocated according to principles every person could agree to. This might suggest we allocate resources on the basis of who needs treatment the most, which is the way paramedics and emergency workers think when performing triage.

Beauchamp and Childress’s treatment of justice highlights one of the major criticisms of their work: it isn’t precise enough to help people decide what to do. If somebody wants to work out how to distribute resources, they might not want to be shown several theories to choose between. They want to be given a framework for answering the question. Of course when it comes to life and death decisions, there are no easy answers.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

WATCH

Politics + Human Rights

James C. Hathaway on the refugee convention

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Giacomo Bianchino The Ethics Centre 27 NOV 2017

It’s easy to be frustrated by “charity giving” during the festive season. Little Billy gets a card from World Vision thanking him for support he never knew he gave. All because his sanctimonious aunt decided a new bike wasn’t particularly important.

We’d expect Billy to be pretty upset. But is objecting to “charity giving” childish or is donating on a friend’s behalf incompatible with Christmas giving altogether?

Reminding others of their ethical duties at a time of celebration is, in many ways, noble. There is also value for charity gifts as responses to the hollow commercial practices of modern Christmas traditions.

Charity giving overhauls the tradition of giving. It seeks to fulfil a social need without consideration of the putative “receiver”. As such, the moral case for charity giving isn’t black and white.

While the act might be well-intended, it is poorly executed. When we give at Christmas, presents convey a specific message – one that charity gifts miss altogether.

When we give, we create a sense of shared meaning between individuals. The gift establishes a relationship on the basis of common commitment. In the case of Christmas, the commitment is to one another. Different gifting rituals have other messages.

For instance, during Kwanzaa, members of the African diaspora give homemade gifts to encourage one another to remember their heritage. Kwanzaa emphasises the creation of a moral community in which each member is dedicated to the other. Do-it-yourself gifts foster an attitude where the focus is not on the gift itself, but the recipient.

It might seem as though the charity gift does something similar. By doing good in the name of the recipient, perhaps we foster a relationship based on social justice rather than consumption. But there is a difficulty here.

When our gift is a donation for a distant community, we’re no longer giving a gift to our friend or family member. We’re giving a gift to that distant community.

However deserving the community is, this form of giving is radically different to the form inherent to Christmas or Kwanzaa. We effectively cut the receiver out of the process and instead use the gift ceremony as a means to achieving our own moral agenda.

If charity gifts are a problem, can we give in a way that goes beyond the department store notions of giving and escapes the cycle of consumption?

Yes, but the solution doesn’t lie in what we give, but in how we give.

We can take cues from other cultures. There are entire systems of morality built around the idea of the gift. The famous sociologist Marcel Mauss wrote of gift economies in tribal cultures. He learned how members of traditional Samoan communities gain or lose standing based on their ability to give and to receive well. The exchange of property there is more about establishing relationships than obtaining any particular object or achieving any social goal.

This idea of the giving being more important than the gift isn’t foreign to Christmas traditions. The first recorded act of Christmas gifting was Queen Victoria to her children in 1850. You’d have to rack your brain to find something that the kids of imperial royalty needed. Indeed, the gifts they got were purely symbolic, gestures of goodwill.

So if you’re toying with the idea of ethical giving this Christmas, don’t line up the usual suspects. Make donations to your chosen charities in your own name, but avoid treating them as a replacement for gifting. Charity gifts don’t show others what they mean to you, they substitute the gift for some other moral end.

Give some thought instead to the received wisdom of gift cultures.

Begin by asking yourself, “what does this person mean to me?” “How best can I show them?”

If the gift is a way of sending a certain message, focus on the message. The object is just a means of communication – the message lies in the giving.

Become an artist of the gift – creative, thoughtful and mindful of the recipient – and you can give without being smarmy or sanctimonious.

Truly a modern Christmas miracle.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 24 NOV 2017

The Ethics Centre is often asked whether it’s possible to “measure” or evaluate organisational culture. Executives and Directors are now alive to the considerable responsibility they bear for the workplaces they preside over – and this has led to a growing demand for robust and credible measurement tools.

Using a methodology developed over 25 years, The Ethics Centre’s Everest process is a forensic review into a company’s ethical culture. It’s based on a simple proposition: that good culture can be measured. Global research shows a healthy culture is essential to sustainable, long-term performance; it enables innovation and builds trust between staff, clients, and customers. Conversely, poor culture leads to bad decisions and an erosion of trust and credibility. The result, inevitably, is disengagement, cynicism, and loss of value.

In the face of challenging conditions, many leaders are tempted to focus their efforts on compliance to prevent ‘bad’ behaviour. But this over-reliance on regulation and surveillance can be counterproductive. Not only can it restrict growth of a positive ethical environment that enables people to innovate and act with a shared purpose and direction, it also doesn’t work. Failures persist. A strong ethical culture is critical to managing risk and building a foundation that will support long term value and performance.

We’ve employed Everest to evaluate the culture of numerous, very different, organisations. We’ve used it on one of Australia’s “big four” banks and a leading superannuation fund. We’ve measured the culture of universities, insurance companies, and leading sports organisations including the Australian Rugby Union, Cricket Australia, and the Australian Olympic Committee.

In carrying out the process both in Australia and abroad, we look at the misalliances between what a company says it stands for, and what occurs in practice. Using this premise, we check how organisations live up to the standards they set for themselves through an audit of systems, policies, procedures, and practices. We undertake extensive qualitative and quantitative research to determine how employees and key stakeholders view the organisation. Out of this process comes a set of powerful insights into the degree of alignment between purpose and practice. We identify the gaps.

Once we’ve made sense of the current state of an organisation, we’re in a position to ask our clients some tough questions about the kind of company they’d like to be. We present clients with a Future State Framework that maps the pathway from the present to the future – asking them to imagine the pinnacle of what’s possible for their organisation. In doing this, we examine five domains:

Culture: The operating system through which people create meaning, purpose, and belonging.

Ecosystem: Organisations are complex, interconnected, and interdependent. They sustain, and are sustained, through relationships, mutual dependencies, and the value they bring to the whole.

Leadership: Providing the guidance, direction, and consistency that allows an organisation to respond to the challenges of uncertainty and change.

Readiness: The ability of an organisation to anticipate and respond to uncertainty. The ability to pre-empt a possible future before it arrives fully formed.

Legacy: The future’s perspective on the present. The map we leave behind for others.

The nature of Everest, particularly when coupled with the independence of The Ethics Centre, is that we can confront leaders with issues that have not previously been articulated, recognised, or challenged. And we do this in a way that lessens defensiveness and focuses on building on the goodwill contained in the existing culture of the organisation.

We’re proud that our process has provided leaders across business and government with the expertise to shine a spotlight on current practices and make choices about the culture and style of organisation they wish to cultivate in the future.

One final note: our Everest reports are delivered to our clients on the understanding that everything contained therein is strictly confidential. What a company does with the report is entirely up to them. None had ever been made public until we worked for the Australian Olympic Committee in 2017.

Facing a media storm over their culture, the AOC took the brave step of releasing the report, in its entirety, to the public. Thanks to this act of radical transparency, we’re able to share it with you here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The near and far enemies of organisational culture

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2017

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759—1797) is best known as one of the first female public advocates for women’s rights. Sometimes known as a “proto-feminist”, her significant contributions to feminist thought were written a century before the word “feminism” was coined.

Wollstonecraft was ahead of her time, both intellectually and in the way she lived. Pursuing a writing career was unconventional for women in 18th century England and she was denounced for nearly a century after her death for having a child out of wedlock. But later, during the rise of the women’s movement, her work was rediscovered.

Wollstonecraft wrote many different kinds of texts – including philosophy, a children’s book, a fictional novel, socio-political pamphlets, travel writings, and a history of the French Revolution. Her most famous work is her essay, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Pioneering modern feminism

Wollstonecraft passionately articulated the basic premise of feminism in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – that women should have equal rights to men. Though the essay was published during the French Revolution in 1792, its core argument that women are unjustifiably rendered subordinate to men remains.

Rather than domestic violence, women in senior roles and the gender pay gap, Wollstonecraft took aim at marriage, beauty, and women’s lack of education.

The good wife: docile and pretty

At the core of Wollstonecraft’s critique was the socioeconomic necessity for marriage – “the only way women can rise in the world”. In short, she argued marriage infantilised women and made them miserable.

Wollstonecraft described women as sacrificing respect and character for far less enduring traits that would make them an attractive spouse – such as beauty, docility, and the 18th century notion of sensibility. She argued, “the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement” and they were “so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence”.

Mother of feminism and victim blamer?

Some readers of A Vindication for the Rights of Woman argued Wollstonecraft was only a small step away from victim blaming. She penned plenty of lines positioning women as wilful and active contributors to their own subjugation.

In Wollstonecraft’s eye, expressions of feminine gender were “frivolous pursuits” chosen over admirable qualities that could lift the social standing of her sex and earn women respect, dignity and quality relationships:

“…the civilised women of the present century, with few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.”

While some might find Wollstonecraft was too harsh on the women she wanted to lift, her spear was very much aimed at men, “who considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives”.

Grab it by the patriarchy

Like the word feminism, the word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft. She nevertheless argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

Wollstonecraft commented on men’s “physical superiority” although she did not accept social superiority should follow.

“…not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment.”

Wollstonecraft’s hammering critique against a male dominated society suggested women were forced to be complicit. They had few work options, no property or inheritance rights, and no access to formal education. Without marriage, women were destined to poverty.

What do we want? Education!

Wollstonecraft pointed out all people regardless of sex are born with reason and are capable of learning.

In a time where it was considered racial to insist women were rational beings, Wollstonecraft raised the common societal belief that women lacked the same level of intelligence as men. Women only appeared less intelligent, Wollstonecraft argued, because they were “kept in ignorance”, housebound and denied the formal education afforded to men.

Instead of receiving a useful education, women spent years refining an appealing sexual nature. Wollstonecraft felt “strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty”. Women’s time was poorly invested.

How could women, who were responsible for raising children and maintaining the home, be good mothers, good household managers or good companions to their husbands, if they were denied education? Women’s education, Wollstonecraft contended, would benefit all of society.

Wollstonecraft suggested a free national schooling system where girls and boys were taught together. Mixed sex education, she argued, “would render mankind more virtuous, and happier” – because society and the term mankind itself would no longer exclude girls and women.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Big thinker

Relationships