Office flings and firings

Office flings and firings

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 20 JUL 2017

If you heard the phrase “cheaters never prosper” talked about at AFL headquarters, you’d assume they were talking about performance enhancing drugs, salary cap breaches or breaking the rules to win a game.

This week, as AFL CEO Gillon McLachlan announced the resignations of two senior officials, Richard Simkiss and Simon Lethlean, after they admitted to adulterous affairs with junior staff, the phrase took on a whole new meaning.

The reaction to McLachlan’s decision has been mixed. Some have applauded the move as a strong defence of the AFL’s culture and values. Others have suggested the AFL has gone too far. Writing in The Australian Financial Review, Josh Bornstein suggested office affairs that don’t involve “harassment or stalking or bullying” should “not be grounds for loss of employment”.

Particulars of the AFL case aside, this view is misguided. It conflates ethics and the law and demonstrates a lack of appreciation for the important role values and principles play in corporate governance. Just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s ethical.

Yes, the law should play a role in guiding an organisation when developing an ethical framework. But it is far from sufficient. Arguably, the best test of an organisation’s ethics will arise when they’re operating in areas not covered by the law.

When a power imbalance could potentially cause harm to the more vulnerable party, then we have good reason to question that conduct.

With that said, what should we make of the AFL’s decision? When announcing the resignation of the two senior officials, McLachlan spoke to his organisation’s values. He stated that he would like to lead “a professional organisation based on integrity, respect, care for each other, and responsibility”.

An organisation’s values are affirmed by the actions, choices, and decisions that are made and condoned by its people, especially its most senior leaders. This also was not lost on McLachlan. “I expect that executives are role models and set a standard of behaviour for the rest of the organisation,” he said. “They are judged, as they should be, to a higher standard”.

The response by the Seven West Media board to revelations that their CEO Tim Worner had an adulterous affair with executive assistant Amber Harrison was a little more benign. They engaged a private law firm to undertake an independent investigation into a variety of allegations made by Harrison, including the inappropriate use of company funds and illicit drug use by Worner.

Although the findings of the investigation were not made public, the board concluded there was no evidence supporting the claims of wrongdoing by Worner. Furthermore, they stated he had been disciplined over his “personal and consensual” relationship with Harrison, which it also said was “inappropriate due to his senior position”.

So what are we to make of these seemingly contrasting responses? Should we cast judgement and declare that one organisation is more virtuous than the other?

We must be careful not to instantly assume that an individual who has become involved in an extra-marital affair is less committed to the organisation or its values. Infidelity is not a simple question of character deficiency.

It should be acknowledged that although the two organisations handled the incidents differently, neither condoned the conduct of the leaders involved. When judging the individuals and the organisation’s responses, commentators and the public appear to point to two factors.

The first is the power asymmetry between the people in each of the affairs. This is not unique. Power asymmetries in organisations are inescapable and almost all leaders have at some stage used their power to gain advantage, even if they did so unwittingly. However, when a power imbalance could potentially cause harm to the more vulnerable party then we have good reason to question that conduct.

The second factor inviting people’s judgement is the fact the affairs were adulterous. Understandably, infidelity arouses a range of moral responses. But we must be careful not to instantly assume that an individual who has become involved in an extra-marital affair is less committed to the organisation or its values. Infidelity is not a simple question of character deficiency.

Stories are powerful. After notable incidents like these, they become folklore within organisations.

Whenever a senior executive becomes involved in a regrettable or unsavoury incident similar to these, an employer has no choice but to respond. How they do so is a defining moment for the organisation. Their response (or lack thereof) reveals to us what the organisation really values and how committed it is to those values.

However, judging the appropriateness of the response is difficult. Perhaps the best measure is one we don’t yet have access. Namely, the stories that these events inspire within the organisation.

Stories are powerful. After notable incidents like these, they become folklore within organisations. If they affirm and are aligned to stated values and principles, they can strengthen the organisation’s ethical foundations. If not, people can quickly become cynical, compromising the organisation’s character.

When we look past the salacious gossip surrounding office romances, this is arguably the most important thing to take from these unfortunate incidents. For the sake of the boards at the AFL and Seven West Media, I hope that the stories being told within their organisations are reflective of the values they extol.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The undeserved doubt of the anti-vaxxer

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: The Panopticon

The panopticon is a disciplinary concept brought to life in the form of a central observation tower placed within a circle of prison cells.

From the tower, a guard can see every cell and inmate but the inmates can’t see into the tower. Prisoners will never know whether or not they are being watched.

This was introduced by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. It was a manifestation of his belief that power should be visible and unverifiable. Through this seemingly constant surveillance, Bentham believed all groups of society could be altered. Morals would be reformed, health preserved, industry invigorated, and so on – they were all subject to observation.

Think of the last time you were at work and your boss walked in the room. Did you straighten up and work harder in their presence? Now imagine they were always in the room. They wouldn’t be watching you all the time, but you’d know they were there. This is the power of constant surveillance – and the power of the panopticon.

Foucault on the panopticon

French philosopher, Michel Foucault, was an outspoken critic of the panopticon. He argued the panopticon’s ultimate goal is to induce in the inmates a state of conscious visibility. This assures the automatic functioning of power. To him, this form of incarceration is a “cruel, ingenious cage”.

Foucault also compares this disciplinary observation to a medieval village under quarantine. In order to stamp out the plague, officials must strictly separate everyone and patrol the streets to ensure villagers don’t leave their homes and become sick. If villagers are caught outside, the punishment is death.

In Foucault’s village, constant surveillance – or the idea of constant surveillance – creates regulation in even the smallest details of everyday life. Foucault calls this a “discipline blockade”. Similar to a dungeon where each inmate is sequestered, administered discipline can be absolute in matters of life or death.

On the other hand, Bentham highlights the panopticon’s power as being a “new mode of obtaining mind over mind”. By discarding this isolation within a blockade, the discipline becomes a self-propagating mental mechanism through visibility.

The panopticon today: data

Today, we are more likely to identify the panopticon effect in new technologies than in prison towers. Philosopher and psychologist Shoshanna Zuboff highlights what she calls “surveillance capitalism”. While Foucault argued the “ingenious” panoptic method of surveillance can be used for disciplinary methods, Zuboff suggests it can also be used for marketing.

Concerns over this sort of monitoring date back to the beginning of the rise of personal computers in the late 80s. Zuboff outlined the PC’s role as an “information panopticon” which can monitor the amount of work being completed by an individual.

Today this seems more applicable. Employers can get programs to covertly track keystrokes of staff working from home to make sure they really are putting in their hours. Parents can get software to monitor their children’s mobile phone use. Governments around the world are passing laws so they can collect internet data on people suspected of planning terror attacks. Even public transport cards can be used to monitor physical movements of citizens.

This sort of monitoring and data collection is particularly analogous with the panopticon because it’s a one-way information avenue. When you’re sitting in front of your computer, browsing the web, scrolling down your newsfeed and watching videos, information is being compiled and sent off to your ISP.

In this scenario, the computer is Bentham’s panopticon tower, and you are the subject from which information is being extracted. On the other end of the line, nothing is being communicated, no information divulged. Your online behaviour and actions can always be seen but you never see the observer.

The European Union has responded to this with a new regulation, known as “the right to an explanation”. It states users are entitled to ask for an explanation about how algorithms make decisions. This way, they can challenge the decision made or make an informed choice to opt out.

In these new ways, Bentham’s panopticon continues to operate and influence our society. Lack of transparency and one-way communication is often disconcerting, especially when thought about through a lens of control.

Then again, you might also argue to ensure a society functions, it’s useful to monitor and influence people to do what is deemed good and right.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

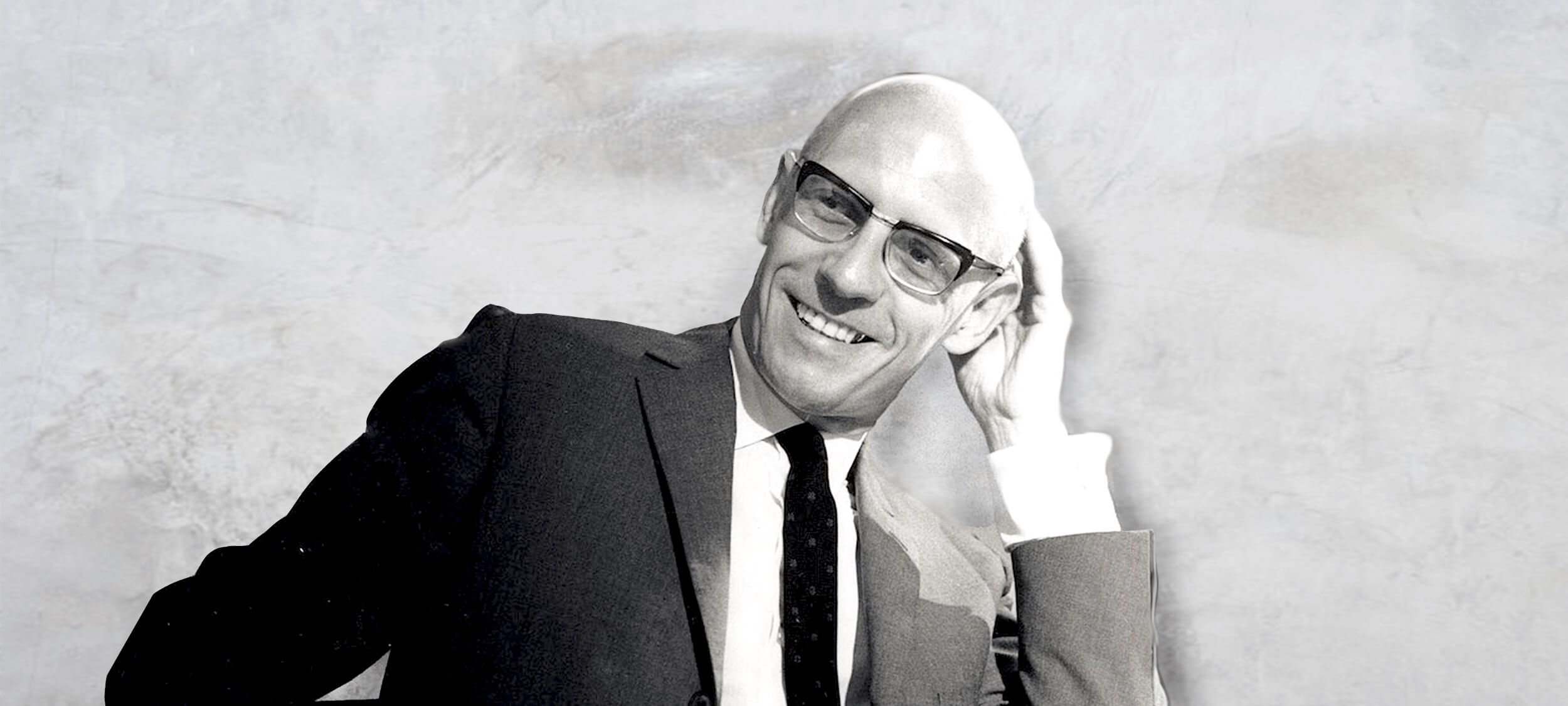

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 13 JUL 2017

Michel Foucault (1926—1984) was a French philosopher, historian and psychologist whose work explored the underlying power relationships in a range of our modern institutions.

Given Foucault’s focus on the ways institutions wield power over us, and that trust in institutions is catastrophically low around the world today, it’s worth having a look at some of the radical Frenchman’s key ideas.

History has no rhyme or reason

At the centre of Foucault’s ideas is the concept of genealogy – the word people usually use when they’re tracing their family history. Foucault thought all of history emerged in the same way a family does – with no sense of reason or purpose.

Just like your existence was the result of a bunch of random people meeting and procreating over generations, he thought our big ideas and social movements were the product of luck and circumstance. He argued what we do is both a product of the popular ways of thinking at the time (which he called rationalities) and the ways in which people talked about those ideas (which he called discourses).

Today Foucault might suggest the dominant rationalities were those of capitalism and technology. And the discourse we use to talk about them might be economics because we think about and debate things in terms their usefulness, efficiency and labour saving. Our judgements about what’s best are filtered through these concepts, which didn’t emerge because of any conscious historical design, but as random accidents.

You might not agree with Foucault. There are people who believe in moral progress and the notion our world is improving as time goes on. However, Foucault’s work still highlights the powerful sense in which certain ideas can become the flavour of the month and dominate the way we interpret the world around us.

For example, if capitalism is a dominant rationality, encouraging us to think of people as economic units of production rather than people in their own right, how might that impact the things we talk about? If Foucault is right, our conversations would probably centre on how to make life more efficient and how to manage the demands of labour with the other aspects of our life. When you consider the amount of time people spend looking for ‘life hacks’ and the ongoing discussion around work/life balance, it seems like he might have been on to something.

But Foucault goes further. It’s not just the things we talk about or the ways we talk about them. It’s the solutions we come up with. They will always reflect the dominant rationality of the time. Unless we’ve done the radical work of dismantling the old systems and changing our thinking, we’ll just get the same results in a different form.

Care is a kind of control

Although many of Foucault’s arguments were new to the philosophical world when he wrote them, they were also reactionary. His work on power was largely a response to the tendency for political philosophers to see power only as the relationship between the sovereign and the citizen – or state and individual. When you read the works of social contract theorists like Thomas Hobbes and Jean Jacques Rousseau, you get the sense politics consists only of people and the government.

Foucault challenged all this. He acknowledged lots of power can be traced back to the sovereign, but not all of it can.

For example, the rise of care experts in different fields like medicine, psychology and criminology creates a different source of power. Here, power doesn’t rest in an ability to control people through violence. It’s in their ability to take a person and examine them. In doing so, the person is objectified and turned into a case (we still read cases in psychiatric and medical journals now). This puts the patients under the power of experts who are masters of the popular medical and social discourses at the time.

What’s more, the expert collects information about the patient’s case. A psychiatrist might know what motivates a person’s behaviour, what their darkest sexual desires are, which medications they are taking and who they spend their personal time with. All of this information is collected in the interests of care but can easily become a tool for control.

A good example of the way non-state groups can be caring in a way that creates great power is in the debate around same sex marriage. Decades ago, LGBTI people were treated as cases because their sexual desires were medicalised and criminalised. This is less common now but experts still debate whether children suffer from being raised by same sex parents. Here, Foucault would likely see power being exercised under the guise of care – political liberties, sexuality and choice in marital spouse are controlled and limited as a way of giving children the best opportunities.

Prison power in inmate self-regulation

Foucault thought prisons were a really good example of the role of care in exercising power and how discourses can shape people’s thinking. They also reveal some other unique things about the nature of power in general and prisons more specifically.

In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault observed a monumental shift in how society dealt with crime. Over a few decades, punishments went from being public, violent spectacles like beheadings, hangings and mutilations to private, clinical and sterile exercises with the prison at the centre of it all. For Foucault, the move represented a shift in discourse. Capital punishment and torture were out, discipline and self-regulation were in.

He saw the new prison, where the inmates are tightly managed and regulated by timetables – meal time, leisure time, work time, lights out time – as being a different form of control. People weren’t in fear of being butchered in the town square anymore. The prison aimed to control behaviour through constant observation. Prisoners who were always watched, regulated their own behaviour.

This model of the prison is best reflected in Jeremy Bentham’s concept of the panopticon. The panopticon was a prison where every cell is visible from a central tower occupied by an unseen guard. The cells are divided by walls so the prisoners can’t engage with each other but they are totally visible from the tower at all times. Bentham thought – and Foucault agreed – that even though the prisoners wouldn’t know if they were being watched at any moment, knowing they could be seen would be enough to control their behaviour. Prisoners were always visible while guards were always unseen.

Foucault believed the panopticon could be recreated as a factory, school, hospital or society. Knowing we’re being watched motivates us to conform our behaviours to what is expected. We don’t want to be caught, judged or punished. The more frequently we are observed, the more likely we are to regulate ourselves. The system intensifies as time goes on.

Exactly what ‘normality’ means will vary depending on the dominant discourse of the time but it will always endeavour to reform prisoners so they are useful to society and to the powerful. That’s why, Foucault argued, prisoners are often forced to do labour. It’s a way of taking something society sees as useless and making it useful.

Even when they’re motivated by care – for example, by the belief that work is good for prisoners and helps them reform – the prison system serves the interests of the powerful in Foucault’s eyes. It will always reflect their needs and play a role in enforcing their vision of how society should be.

You needn’t accept all of Foucault’s views on prisons to see a few useful points in his argument. First, prisons haven’t been around forever. There are other ways of dealing with crime we could use but choose not to. Why do we think prisons are the best? What are the beliefs driving that judgement?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 5 JUL 2017

Where lying is the abuse of truth and harm the abuse of dignity, philosophers associate theft with the abuse of ownership.

We tend to take property for granted. People own things, share things or have access to things that don’t belong to them. We rarely stop to think how we come to own things, whether there are some things we shouldn’t be allowed to own or whether our ideas of property and ownership are adequate for everybody.

This is where English philosopher John Locke comes in.

Locke believed that in a state of nature – before a government, human made laws or an established economic system – natural resources were shared by everyone. Similar to a shared cattle-grazing ground called the Commons, these were not privately owned and so accessible to all.

But this didn’t last forever. He believed common property naturally transformed into private property through ownership. Locke had some ideas as to how this should be done, and came up with three conditions:

- First, limit what you take from the Commons so everyone else can enjoy the shared resource.

- Second, take only what you can use.

- Third, that you can only own something if you’ve worked and exerted labour on it. (This is his labour theory of property).

Though his ideas form the bedrock of modern private property ownership, they come with their fair share of critics.

Ancient Greek philosopher Plato thought collective property was a more appropriate way to unite people behind shared goals. He thought it was better for everyone to celebrate or grieve together than have some people happy and others sad at the way events differently affect their privately-owned resources.

Others wonder if it is complex enough for the modern world, where the resource gap between rich companies and poor communities widens. Does this satisfy Locke’s criteria of leaving the Commons “enough and as good”? He might have a criticism of his own about our current property laws – that they’ve gone beyond what our natural rights allow.

Some critics also say his theory denies the cultivation techniques and land ownership of groups like the Native Americans or the Aboriginal Australians. While Locke’s work serves as a useful explanation of Western conceptions of property ownership, we should wonder if it is as natural as he thought it was.

On the other hand, it’s likely Locke simply had no idea of the way in which Indigenous people have managed the landscape over millennia. Had he understood this, then he may have recognised the way Indigenous groups use and relate to land as an example of property ownership.

Karl Marx, and the closely associated philosophies of socialism and communism, prioritise common or collective property over private forms of property. He thought humanity should – and does – move toward co-operative work and shared ownership of resources.

However, Marx’s work on alienation may be a common ground. This is when people’s work becomes meaningless because they can’t afford to buy the things they’re working to make. They can never see or enjoy the fruits of their labour – nor can they own them. Considering the importance Locke places on labour and ownership, he may have had a couple of things to say about that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Moral hazards

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethical dilemma: how important is the truth?

Ethical dilemma: how important is the truth?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 16 JUN 2017

Someone I know has just told me that the wife of a very good friend had an affair a few years ago.

The thing is that they seem very happy together, as do their children, and they are a solid family unit. The source of information is good, in that I can trust the person telling me, but he heard from someone else rather than ‘knowing’ for himself. What to do now that I have this information? Do I follow the lead to the original source to find out if it’s true? Do I confront my friend’s wife? Tell my friend? Forget about it altogether? If it isn’t true, I risk looking like an idiot; if it is, I risk breaking up a marriage and family. How important is the truth?

It’s tempting to say “this is none of your business – this is a matter for the person who had the affair to own up to”, but I’m not convinced by that. By saying nothing, you’re still making a decision to withhold potentially life-changing information from someone.

Let’s say that if your friend knew of the affair, they’d leave their wife, decide to stop sleeping with them or whatever. By withholding that information, you’re preventing them from making a choice they would otherwise make, which they have the right to make and which might be in their best interests. That’s a serious responsibility to take on, so you’d need to have pretty good reasons to justify saying nothing.

One such reason might be uncertainty. You say you’ve had this information given to you by a trustworthy source, but your source got that information as gossip. So, the question isn’t ‘can I trust my source?’; it’s ‘can I trust gossip?’

Your source might have good reasons to trust that gossip – you should ask what they are. If there aren’t any special circumstances, it’s hard to see on what basis you’d believe the allegations.

Now you’re wondering whether you need to investigate further. You’ve been told something but it’s an unreliable source – should you go out and find a more reliable source to make a decision one way or the other?

If you do decide to pursue the source further, it’s important you recognise exactly what that means. You’ve been told something is true, realised the source is unreliable and then decided it’s your job to try to find another source that proves it to be true. That’s not an impartial way to make the decision.

Most people would think if you only have one source of evidence for a claim and that evidence is bad, then you no longer have any reason to believe the claim. To keep looking for new evidence to prove the claim true is what psychologists call ‘confirmation bias’.

Still, if you have a close enough relationship to your friend you might be willing to fly in the face of reason and leave no stone unturned. But it would be wrong to say you’re obliged to investigate further: there’s just not enough evidence for that.

This article originally appeared in New Philosopher issue #17 on Communication.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

WATCH

Relationships

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

4 questions for an ethicist

4 questions for an ethicist

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 16 JUN 2017

Though not as common as GPs, therapists, or personal trainers, ethicists still have a lot to say about how to live a good life. Here are four of the common questions they get asked.

1. There are so many conflicting versions of ethics out there – legal, social, religious. Which should I listen to?

With all these voices vying for our attention it can be difficult to know who to listen to. An important starting point with ethics is to untangle the nature of these conflicting voices to better be able to hear our own.

Our beliefs and values are influenced by our upbringing, community, professions, and for many people, their faith. It’s useful to think of these voices – social customs, the law and religion – as ‘morality’ rather than ethics.

Morality is a set of deeply held and widely shared norms and rules within a community. Like ethics, morality provides us with opinions, rules, laws, and principles to guide our choices and actions. But unlike ethics, morality can be followed unthinkingly and without asking questions.

Ethics is about reflecting on who we are, what we value, and how we want to live in a world where many others may not share the same values and principles as us.

What makes ethics both timely and timeless is it arises in any moment when we find ourselves faced with the question of what is right. This question is both a philosophical and practical one. Philosophically, it involves exploring the nature of concepts like truth, wisdom, and belief and providing a justification for right and good actions.

On a practical level, it is a question we find ourselves asking every day. Whether it’s the big ethical issues – abortion, capital punishment, immigration – or everyday ethical questions – whether to tell the truth to a friend when it may hurt their feelings, or being asked to provide a reference for a close colleague who isn’t qualified for the job – ethical questions are inescapable parts of being human.

Ethics does not rely on history, tradition, religion, or the law to solely to define for us what is good or right. Ethics is about reflecting on who we are, what we care about, and how we want to live in a world where many others may not share the same values and principles as us.

2. Isn’t ethics just a matter of opinion? If there’s no way to tell who is right and who is wrong, isn’t my opinion as good as anyone’s?

In the 1990s Mike Godwin famously argued when it comes to online arguments, the longer and more heated a debate gets, the more likely somebody will bring up the Nazis in an attempt to close it down.

When it comes to discussions of ethics there is an inverse law which anyone who has taught an ethics class will have experienced. The shorter the conversation about ethics, the greater the likelihood somebody will claim, “Ethics is just personal opinion”.

When the stakes are high, it becomes abundantly clear that we want to hold others to a similar standard of what we think matters.

This view implies ethics is subjective. What follows from this is there are no better or worse opinions on ethics.

However, it would be hard to find someone say in response to being robbed, “The thief had their own values and I have mine, they are entitled to their view, so I won’t pursue this further”. When the stakes are high, it becomes abundantly clear we want to hold others to a similar standard of what we think matters.

We will inevitably reach a point in any discussion of ethics where people will strongly express a fundamental moral belief – for example, it’s wrong to steal, to lie or to harm others. These opinions are the beginning of a common, rational basis for discussions about what we should or shouldn’t do.

And when those discussions become heated, let’s try and leave Hitler out of it.

3. I’m a good person, why do I need ethics?

Ethics helps good people become better people.

Being a good person doesn’t necessarily mean you will always know what’s right. Good people disagree with each other about what is right all the time. And good people often don’t know what to do in difficult situations, especially when these situations involve ethical dilemmas.

We all have the tendency to act unethically given the ‘right’ conditions. Fear, guilt, stress, and anxiety have been shown to be significant factors that prevent us from acting ethically.

Good people make bad choices. Despite the widespread view that bad things happen due to a small percentage of so called ‘evil people’ intentionally doing the wrong thing, the reality is that all of us can make poor decisions.

We all have the tendency to act unethically given the ‘right’ conditions. Fear, guilt, stress and anxiety have been shown to be significant factors that prevent us acting ethically.

Food has been shown to directly influence the quality of decisions made by judges. Other studies have shown that even innocuous influences can have a disproportionate effect on our decisions. For example, smells affect the likelihood a person will help other people.

Ethics is not only about being aware of our values and principles. It is also about being alive to our limited view of the world and striving to expand our horizons by trying to better see the world as it really is.

4. People only do ethics when it makes them look good. Why would anyone put ethics above self-interest?

One argument often heard in philosophy and psychology is that everything we do, from the compassionate to the heroic, is ultimately done for our own benefit. When we boil it down, we only save lives, donate to charity or care for a friend because these things make us feel good or benefit us.

However, despite being a widely held view it is only half the story – and not even the most interesting part of the story. While human beings are undoubtedly self-interested there is a wealth of evidence that shows human beings are hard wired to care for others, including total strangers.

Research has shown the existence of ‘mirror neurons’ in our brains that naturally respond to other people’s feelings.

Ethics is rooted in this fundamental human capacity to be connected to others. It provides a rational foundation for this connection. This is the foundation of empathy. It’s an intrinsic part of what makes us human.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

ExplainerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 2 JUN 2017

When you have a right either to do or not do something, it means you are entitled to do it or not.

Rights are always about relationships. If you were the only person in existence, rights wouldn’t be relevant at all. This is why rights always correspond to responsibilities. My rights will limit the ways you can and can’t behave towards me.

Legal philosopher Wesley Hohfeld distinguished between two sets of rights and responsibilities. First, there are claims and duties. Your right to life is attached to everyone else’s duty not to kill you. You can’t have one without the other.

Second, there are liberties and no-claims. If I’m at liberty to raise my children as I see fit it’s because there’s no duty stopping me – nobody can make a claim to influence my actions here. If we have no claim over other people’s liberties, our only duty is not to interfere with their behaviour.

But your liberty disappears as soon as someone has a claim against you. For example, you’re at liberty to move freely until someone else has a claim to private property. Then you have a duty not to trespass on their land.

It’s useful to add into the mix the distinction between positive and negative rights. If you have a positive right, it creates a duty for someone to give you something – like an education. If you have a negative right, it means others have a duty not to treat you in some way – like assaulting you.

All this might seem like tedious academic stuff but it has real world consequences. If there’s a positive right to free speech, people need to be given opportunities to speak out. For example, they might need access to a radio program so they can be heard.

By contrast, if it’s a negative claim right, nobody can censor anyone else’s speech. And if free speech is a liberty, your right to use it is subject to the claims of other. So if other people claim the right not to be offended, for example, you may not be able to speak up.

There are a few reasons why rights are a useful concept in ethics.

First, they are easy to enforce through legal systems. Once we know what rights and duties people have, we can enshrine them in law.

Second, rights and duties protect what we see as most important when we can’t trust everyone will act well all the time. In our imperfect world, rights provide a strong language to influence people’s behaviour.

Finally, rights capture the central ethical concepts of dignity and respect for persons. As the philosopher Joel Feinberg writes:

Having rights enables us to “stand up like men,” to look others in the eye, and to feel in some fundamental way the equal of anyone. To think of oneself as the holder of rights is not to be unduly but properly proud, to have that minimal self-respect that is necessary to be worthy of the love and esteem of others.

Indeed, respect for persons […] may simply be respect for their rights, so that there cannot be the one without the other; and what is called “human dignity” may simply by the recognizable capacity to assert claims.

Feinberg suggests rights are a manifestation of who we are as human beings. They reflect our dignity, autonomy and our equal ethical value. There are other ways to give voice to these things, but in highly individualistic cultures, what philosophers call “rights talk” resonates for two reasons: individual freedom and equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Hey liberals, do you like this hegemony of ours? Then you’d better damn well act like it

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2017

Simone de Beauvoir (1908—1986) was a French author, feminist and existential philosopher. Her unconventional life was a working experiment of her ideas – that one creates the meaning of life through free and authentic choices.

In a cruel confirmation of the sexism she criticised, Beauvoir’s work is often seen as less important than that of her partner, Jean Paul Sartre. Given the conclusions she drew were hugely influential, let’s revisit her ideas for a refresher course.

Women aren’t born, they’re made

Beauvoir’s most famous quote comes from her best-known work, The Second Sex: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”.

By this she means there is no essential definition of womanhood. Women can be anything, but social norms work hard to fit them into a particular kind of femininity. These social norms are patriarchal and born out of the male gaze.

The Second Sex argues that it’s men who define what women should be. Because men have always held more power in society, the world looks the way men want it to look. An obvious example is female beauty.

Beauvoir holds that through norms around removing body hair, makeup and uncomfortable fashion, women restrict their freedom to serve the male gaze.

This objectification of women goes deeper, until they aren’t seen as fully human. Men are seen as active, free agents who are in control of their lives. Women are described passively. They need to be protected, controlled or rescued.

It’s true, she thinks, that women aren’t always seen as passive objects, but this only happens when they impersonate men.

“Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.”

For Beauvoir, women are always cast into the role of the Other. Who they are matters less than who they’re not: men. This is an enormous problem for the existentialist, for whom the purpose of life is to freely choose who they want to be.

Everyone has to create themselves

As an existentialist, Beauvoir believed people need to live authentically. They need to choose for themselves who they want to be and how they want to live. The more pressure society – and other people – place on you, the harder it is to make an authentic choice.

Existentialists believe no matter the amount of external pressure, it is still possible to make a free choice about who we want to be. They say we can never lose our freedom, though a range of forces can make it harder to exercise. Plus, some people choose to hide from their freedom in various ways.

Some of us hide from our freedom by living in bad faith, embracing the definitions other people put on us. Men are free to reject the male gaze and stop imposing their desires onto women but many don’t. It’s easier, Beauvoir thinks, to accept the social norms we’re born into. To live freely and authentically is the greater struggle.

The importance of freedom led Beauvoir to suggest liberated women should not try to force other women to live their lives in a similar way. If a small group of women choose to reject the male gaze and define womanhood in their own way, that’s great.

But respecting other people means allowing them to live freely. If other women don’t want to join the feminist mission, Beauvoir believed they should not be forced or pressured to do so. This is important advice in an age where online shaming is often used to force people to conform to popular social views.

We’re as ageist as we are sexist

Later in life, Beauvoir applied her arguments about women in The Second Sex to the plight of the elderly. In The Coming of Age, she argued that we make assumptions and generalisations about the elderly and ageing, just like we do about women.

To her, it is as wrong to ‘other’ women because they are different from men, as it is to ‘other’ the elderly because they are different from the young. Feminist philosopher Deborah Bergoffen explains Beauvoir’s view: “As we age, the body is transformed from an instrument that engages the world into a hindrance that makes our access to the world difficult”.

Like women in The Second Sex, the elderly remain free to define themselves. They can reject the idea that physical decline makes them unable to function as authentic human beings.

In The Coming of Age, we see some of the foundations of today’s discussions about ageism and ableism. Beauvoir urges us to come back to a simple truth: the facts of our existence – what our bodies are like, for example – don’t have to define us.

More importantly, it’s wrong to define other people only by the facts of their existence.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

How The Festival of Dangerous Ideas helps us have difficult conversations

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Tough love makes welfare and drug dependency worse

Tough love makes welfare and drug dependency worse

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Nicole Lee The Ethics Centre 17 MAY 2017

“Look, if somebody has got an addiction to drugs and you love them, what do you want to do? You want them to get off it, don’t you?” Malcolm Turnbull said recently in defence of the Coalition’s new plan to conduct drug tests on welfare recipients. “This is a policy that is based on love”.

The policy warrants some analysis – starting with the methodology.

The government plans to conduct drug tests on 5000 welfare recipients in three undisclosed locations as a pilot program – with these locations selected by testing waste water. Just so we’re clear on this, they’ll be testing sewage water for the presence of drugs. So if, for example, Toorak registers a high reading for drugs, welfare recipients in that suburb may be nominated to participate in the pilot program.

It’s not clear whether the government plans to test the sewage pipes of every suburb of Australia, or just the ones with a lot of welfare recipients.

Once this messy, smelly, but undeniably fascinating work has been completed, the policy will operate on a “three strikes” approach. The first positive drug test will place welfare recipients on a cashless debit card that cannot be used for alcohol, gambling or cash withdrawals. A second strike gets you a referral to a doctor for treatment. After three strikes, your welfare payments are cancelled for a month.

Unfortunately, sanctions and punishment won’t help people manage their drug use. Love – even tough love – isn’t going to get us anywhere near a solution. Here’s why.

Drug use and drug dependence aren’t the same thing

Not everyone that takes drugs is dependent on them and not everyone needs treatment. All the drugs on the proposed testing list are used recreationally and the majority of people who use them are not dependent.

Only a relatively small proportion of current users – around 10% – are dependent on alcohol or other drugs. For example, very few people who use ecstasy ever become dependent on it. Only 1% of people seeking help from alcohol and other drug services name it as their primary drug of concern. Seventy percent of people who have used methamphetamine in the last year have used less than 12 times. Around 15 percent are dependent on it.

This means the government is potentially wasting large amounts of money drug testing and sanctioning people who only use occasionally.

It will do more harm than good

Whatever you believe about the morality of drug use, the reality is that just restricting income and expenditure will not stop people using drugs. It’s just not that simple. And it creates a number of potential unintended consequences.

Even if we assume that everyone who uses drugs needs treatment (which is not the case), you can’t just say “Stop it!” and hope that works. Dependence is a chronic and relapsing condition. Anybody who has been a regular smoker or has participated in Dry July probably has some experience of how hard it is to abstain from their drug of choice, even for a short time.

Even if it could stop people using, this proposal doesn’t address any of the broader social risk factors that maintain drug use and trigger relapse.

The idea that taking away money to buy drugs will magically stop people using them is a gross oversimplification of why people use drugs, what happens when they are dependent on them, and why they quit. Theft and other crime may increase as people denied payments find other ways to buy drugs.

Even if it could stop people using, this proposal doesn’t address any of the broader social-risk factors that maintain drug use and trigger relapse: mental health issues, disrupted connection with community, lack of employment and education, housing instability, and poverty.

Worse still, the policy may discourage people who are dependent on drugs from seeking help for fear of losing their benefits.

Drug testing doesn’t reduce drug use or its consequent harms. But what it can do is shift drug use to other (often more dangerous) drugs that are not part of the testing regime. People who use cannabis may switch to more dangerous synthetic cannabinoids and those using ecstasy or methamphetamine may switch to other more harmful stimulants.

It threatens civil liberties

In a workplace context, court rulings clearly indicate that drug testing is only justified on clear health and safety grounds. This is because there is a balance required with privacy and consent. Greg Barnes from the Australian Lawyers Alliance has already highlighted the potential conflict in gaining consent of a vulnerable individual under duress of sanctions.

The measure targets the most vulnerable, poorest, and youngest Australians, potentially further marginalising and stigmatising them. We know that when people feel stigmatised they are less likely to seek the help they need.

Punitive measures just don’t work. They reflect a deep lack of understanding about drug use, its effects and of what works to address drug-related problems.

It creates a “deserving” and “undeserving” dichotomy based on private moral judgements about whether it is right or wrong to use drugs.

It assumes, without evidence, that drug use is a major cause of welfare dependence and a barrier to finding work. Research from the US suggests neither is true.

We need evidence-based policy

It’s difficult to see what the government will achieve from this paternalistic measure. Politically, it may appease the far right’s “tough on drugs” rhetoric – but as a piece of policy, it is unlikely to achieve what it hopes to.

The experience from the US is that punitive measures just don’t work. They reflect a deep lack of understanding about drug use, its effects and of what works to address drug-related problems.

This is not going to reduce drug use or harms. It has the potential to increase crime, infringes on civil liberties and it is going to cost a lot of money that would be better spent in harm reduction and drug treatment.

If the government really wants to put this kind of money into reducing drug use among those on welfare, providing more money to the underfunded treatment sector would be a better place to start.

According to the Drug Policy Monitoring Program at UNSW, drug treatment is funded at less than half the amount the community needs. Yet for every dollar we put into treatment we save $7 in health and social costs. If we want to save money in the budget, it seems like a no-brainer.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The road back to the rust belt

BY Nicole Lee

Dr Nicole Lee is Adjunct Professor at the National Drug Research Institute Curtin University and Director of drug and alcohol consultancy 360Edge.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

In philosophy, vulnerability describes the ways in which people are less self-sufficient than they think.

It explains how factors beyond our control – like other people, events, and circumstances – can impact our ability to live our best lives. The implications of vulnerability for ethics are considerable and wide reaching.

Vulnerability isn’t a new idea. The ancient Greeks recognised tuche – luck – as a goddess with considerable power. Their plays often show how a person’s circumstances alter on the whim of the gods or a random twist of luck (or, if you like, a twist of fate).

This might seem obvious to many people. Of course, external events can affect our lives. If an air conditioning unit falls out of an apartment and lands on my head tomorrow, it’s going to change my circumstances pretty dramatically. But this isn’t the kind of luck philosophers argue is relevant to ethics.

A question of character

The Stoics, a group of ancient Greek philosophers (who are experiencing a revival today) thought only our own choices could affect our character or wellbeing. If I lose my job, my happiness is only affected if I choose to react to my new circumstances badly. The Stoics thought we could control our reactions and overcome our emotions.

The Stoics, much like Buddhist philosophy, thought our main problem was one of attachment. The more attached to external things – jobs, wealth, even loved ones – the more we risk suffering if we lose those things. Instead, they recommended we only be concerned with what we can control – our own personal virtue. For Stoics, we aren’t vulnerable because the only thing that matters can’t be taken away from us: our virtue.

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant had similar thoughts. He believed the only thing that mattered for ethics was that we act with good will. Whatever happened to us or around us, so long as we act with the intention of fulfilling our duties, we’d be in the clear, ethically speaking. It’s our rational nature – our ability to think – that defines us ethically. And thinking is completely within our control.

Both Kant and the Stoics believed the ethical life was invulnerable. External circumstances, like luck or other people, couldn’t affect our ability to make good or bad choices. As a result, whether or not we are ethical is up to us.

Can one ever be self-sufficient?

This idea of self-sufficiency has faced challenges more recently. Many philosophers simply don’t think it’s possible to be self-sufficient to the degree that the Stoics and Kant believed. But some go further – seeing a measure of virtue in vulnerability. For example, vulnerability has become a popular term among psychologists and self-help gurus like Brené Brown. They argue vulnerability, dependency, and luck make up important parts of who we are.

Several thinkers, such as Bernard Williams, Thomas Nagel, and Martha Nussbaum have criticised the idea of self-sufficiency. Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, for example, argues that dependency is in our nature.

We’re all born completely dependent on other people and will reach a similar level of dependency if we live long enough. In the meantime, we’ll be somewhat independent but will still rely on other people for help, for community, and to give meaning to our lives.

MacIntyre thinks this is true even if Kant is right and rational adults are invulnerable to luck (at least in terms of choosing to do their duty). However, against Kant, MacIntyre argues that our capacity for rationality is honed by education and the quality of our education is often beyond our control… as we are dependent on the judgement and circumstances of our parents, society, and so on. Thus, we remain vulnerable in important ways.

Mutual vulnerability

Dr Simon Longstaff, the CEO of The Ethics Centre, has made a different argument in favour of vulnerability. He argues, after Thomas Hobbes, that the reality of mutual vulnerability lies at the heart of how and why we form social bonds. As a result, he argues those who seek to eliminate all forms of vulnerability risk creating a world in which the ‘invulnerable’ show no restraint in their treatment of the vulnerable.

All of this might seem like another academic debate but our understanding of vulnerability has significant consequences for the way we judge ourselves and others. If vulnerability matters, we’re less likely to judge people based on their circumstances. We won’t expect the poor always to lift themselves out of poverty (because unlucky circumstances may deny them the means to do so) nor assume every person struggling with an addiction is necessarily morally deficient. They may simply be stuck with the outcome of events that were (at least initially) beyond their control.

We may also be a little less self-congratulatory. Recognising the ways bad luck can affect people means also seeing how we’ve benefitted from good luck. Rather than assuming all our fortune is the product of hard work and personal virtue, we might be moved by vulnerability to acknowledge how factors beyond our control have worked in our favour.

Finally, vulnerability is one of the concepts that underpins modern debates about privilege and identity politics. If we think people are self-sufficient, we’re less likely to think past injustices have any effect on their present lives. However, if we think factors beyond our control can affect not just our lives but also our character and wellbeing, we might see the claims of minorities in a more open light.

There is a final sense in which vulnerability might be important to ethics. The ‘invulnerable’ person may come to believe their judgement is perfectly formed. They might become ‘immune to doubt’. If people open themselves to the possibility they might be wrong, they live an ‘examined life’ – that is, an ethical life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The Ethics of Online Dating

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology