Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 8 FEB 2024

How a 1990s science-fiction show reminds us that just because we can do something, it doesn’t always mean we should.

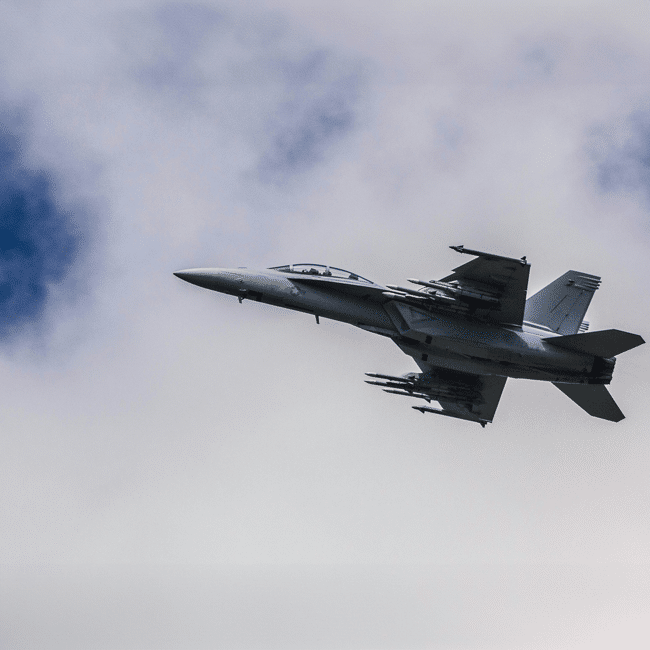

Captain Jean-Luc Picard commands the USS Enterprise-D, a 600-metre-long starship that runs on antimatter, giving it virtually unlimited energy, and wielding weapons of devastating power.

In its journeys across the stars, depicted in Star Trek: The Next Generation, the crew of the Enterprise-D is often forced to draw on all its resources to overcome tremendous challenges. But that’s not what the show is really about.

If there’s one theme that pervades this iteration of Star Trek, it’s not how Picard and his crew use their prodigious power to get their way, it’s how their actions are more often defined by what they choose not to do. Countless times across the 176 episodes of the show, they’re faced with an opportunity to exert their power in a way that benefits them or their allies, but they choose to forgo that opportunity for principled reasons. Star Trek: The Next Generation is a rare and vivid depiction of the principle of ethical restraint.

Consider the episode, ‘Measure of a Man’, which sees Picard defy his superiors’ order to dismantle his unique – and uniquely powerful – android second officer, Data. Picard argues that Data deserves full personhood, despite his being a machine. This is even though dismantling Data could lead to the production of countless more androids, dramatically amplifying the power of the Federation.

One of the paradigmatic features of The Next Generation is its principle called the Prime Directive, which forbids the Federation from interfering with the cultural development of other planets. While the Prime Directive is often used as a plot device to introduce complications and moral quandaries – and is frequently bent or broken – its very existence speaks to the importance of ethical restraint. Instead of assuming the Federation’s wisdom and technology are fit for all, or using its influence to curry favour or extract resources from other worlds, it refuses to be the arbiter of what is right across the galaxy.

This is an even deeper form of ethical restraint that speaks to the liberalism of Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s creator. The Federation not only guides its hand according to its own principles, but it also refuses to impose its principles on other societies, sometimes holding back from doing what it thinks is right out of respect for difference.

The 1990s was another world

There’s a reason that restraint emerged as a theme of Star Trek: The Next Generation. It was the product of 1990s America, which turned out to be a unique moment in that country’s history. The United States was a nation at the zenith of its power in a world that was newly unipolar since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It was an optimistic time, one that looked forward to an increasingly interconnected globalised world, where cultures could intermix in the “global village,” with its peace guarded by a benevolent superpower and its liberal vision. At least, that was the narrative cultivated within the US.

In a time where the US was unchallenged, moral imagination turned to what limits it ought to impose on itself. And Star Trek did what science fiction does best: it explored the moral themes of the day by putting them to the test in the fantasy of the future.

Today’s world is different. It’s now multipolar, with the rise of China and belligerence of Russia coinciding with the erosion of America’s power, political integrity and moral authority. The global outlook is more pessimistic, with the shadow of climate change and the persistence of inequality causing many to give up hope for a better future. Meanwhile, globalisation and liberalism have retreated in the face of parochialism and authoritarianism.

When we see the future as bleak and feel surrounded by threats, ethical restraint seems like a luxury we cannot afford. Instead, the moral question becomes about how far we can go in order to guard what is precious to us and to keep our heads above literally rising waters.

The power not to act

Yet ethical restraint remains an important virtue. It’s time for us to bring it back into our ethical vocabulary.

For a start, we can change the narrative that frames how we see the world. Sure, the world is not as it was in the 1990s, but it’s not as bleak as many of us might feel. We can be prone to focusing on the negatives and filling uncertainties with our greatest fears. But that can distort our sense of reality. Instead, we should focus on those domains where we actually have power, as do many people living in wealthy developed countries like Australia.

And we should use our power to help lift others out of despair, so they’re not in a position where ethical restraint is too expensive a luxury. Material and social wealth ultimately make ethics more affordable.

Just as importantly, restraint needs to become part of the vocabulary of those in positions of power, whether that be in business, community or politics.

Leaders need to implicitly understand the crucial distinction between ought and can: just because they can do something, it doesn’t mean they should.

This is not just a matter of greater regulation. For a start, laws are written by those in power, so they need to exercise restraint in their creation. Secondly, regulation often sets a minimum floor of acceptable behaviour rather than setting bar for what the community really deserves. It also requires ethical literacy and conviction to act responsibly within the bounds of what is legally permitted, not just a tick from a compliance team.

If you have power, whether you lead a starship, a business or a nation, then the greater the power you wield, the greater the responsibility to have to wield it ethically, and sometimes that means choosing not to wield it at all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

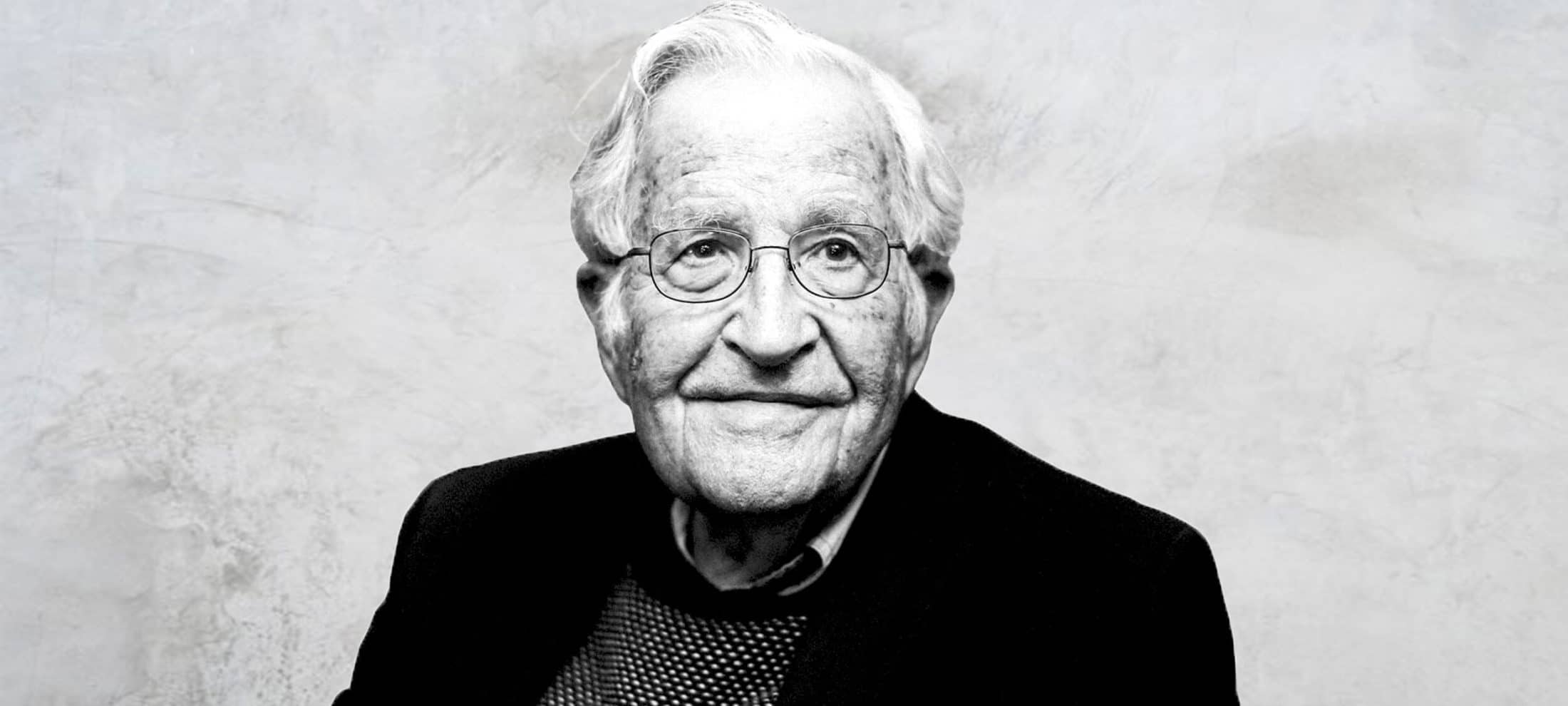

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 15 DEC 2023

Can we be too nice? On the surface, it seems absurd to say we should put a cap on how nice we should be. But if we overdo it, we can end up shirking our other ethical obligations.

Skim the headlines or scroll through social media and you’d be forgiven for concluding that there’s a serious deficit of niceness in the world today, and if only people were a little more kind, compassionate and giving, then the world would be a much better place.

Imagine a nicer world where other drivers consistently backed off to let you merge lanes, or shrugged off your occasional failure to check a blind spot with a smile and a wave. Imagine a workplace where everybody lifted each other up, and covered for you when you needed a break. Imagine a world with more Dumbledores and fewer Snapes. Imagine a world without Karens.

Most philosophers have sought such a world by urging us to cultivate niceness. Confucious promoted the foundational virtue of ren, often translated as benevolence or humanity. Aristotle argued that the path to flourishing lay in cultivating virtues like magnanimity, generosity and patience. Christian scholars promoted temperance was a cardinal virtue. In more modern times, Peter Singer has said we ought to take the compassion we feel towards close family and friends and expand it to cover all sentient creatures, human and animal. In short: be nice.

But there’s also a catch with niceness. If we take it to excess, we can leave ourselves vulnerable to exploitation, fail in our ethical duties and even undermine the very moral foundations of our community.

This is because a world where everyone is fully trusting and selflessly giving is a ripe hunting ground for those who are willing to abuse that trust and get ahead by stepping on the backs of others.

The paradox of niceness

This phenomenon can be modelled using the popular game theoretic thought experiment, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine a situation where two bank robbers are arrested and held in separate cells, unable to communicate with each other. The police have no other witnesses, so they’re relying on the suspects’ testimony to prove the case against them. If both suspects confess, they’ll both receive a five-year sentence. If they both remain silent, then the police will only be able to charge them with a minor offense carrying a one-year sentence. However, if one of them testifies while their partner remains silent, then the dobber will be set free while their partner will go to jail for 10 years.

On the surface, it seems sensible for them both to remain silent. That would be the “nice” thing to do because it benefits them both. But there’s a twist. If one of the suspects believes that their partner will remain silent, then they have an opportunity to testify against them and get off scott-free, while their partner is thrown in the slammer. They also know that if they remain silent, then their partner will have an opportunity to dob them in. As a result, the most reasonable thing for either of them to do is dob on the other, which means they both end up with a harsher penalty than if they’d both cooperated and stayed silent.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma models a fundamental truth when it comes to social interaction: if we we’re nice, we all benefit, but there will always be a temptation to exploit the charity of others to get ahead, and in doing so, we can end up destroying the possibility of cooperation altogether.

There have been whole virtual tournaments using the Prisoner’s Dilemma to see what kinds of strategies – whether “nice” or “nasty” – will yield the best results for the agents playing the game. And it’s from these tournaments that another twist emerges.

In a single Prisoner’s Dilemma game, the nasty dobber has the upper hand, especially if their partner is nice. However, when the same agents play the game over and over, it turns out that it pays to be nice, because you’re likely to be punished in the next game if you’ve been nasty. When you add in some real-world flavour to the game, like making it so that agents can sometimes mistakenly defect when they meant to cooperate, it’s the nicer agents that come out on top.

But these simulations show that niceness has its limits. Those agents that are unconditionally nice tend to get exploited by nasty ones. However, those strategies that are conditionally nice, and that defect only to punish bad behaviour, do best of all.

Toxic niceness

Back in the real world, what this means is that it is possible to be too nice. If we’re unconditionally generous and forgiving, then we leave ourselves open to exploitation by people who will take advantage of our niceness.

It’s likely we all know someone who is a natural giver, someone whose empathy is overflowing and who goes out of their way to help everyone around them. These people are often much loved, but they can also be crushed under the weight of their own compassion, sometimes neglecting their own wellbeing, and it’s not uncommon for others to take advantage of their generosity.

Such unconditional niceness can also prevent us from punishing those who deserve it. You may have also worked for a manager who was overly forgiving, not only of minor transgressions, but also behaviour that was toxic or harmful to others. Punishment is inherently unpleasant, and the overly nice can be reluctant to mete it out, staying their hand while wrongdoers run amok. That not only undermines the moral community, but it makes it harder to hold people to account for their actions, preventing them from growing by learning from their mistakes.

Niceness is good. Be nice. But not so nice that you allow others to be nasty.

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

The Yes campaign is failing. If nothing changes soon, then October 14 will see constitutional reform fail, setting back recognition and reconciliation by years, if not decades.

And no amount of impassioned speeches by politicians, mass rallies by the Yes faithful, uplifting advertisements or – dare I say – editorial columns are likely to shift the needle towards Yes.

This is because voters who are currently unsure or leaning towards No have tuned out the “official” platforms. Their trust in mainstream media outlets has collapsed to single digit figures. It’s not even that they’ve switched to social media. It turns out that the only ones who have their ear are friends, family and colleagues. In this age of mass cynicism and social media schisms, it’s good old-fashioned relationships that still matter.

So, if you believe in the Voice, as I do, if you believe it represents an opportunity for Australia to take meaningful steps towards reconciliation with First Nations peoples, and if you believe it could be a stepping stone to a more unified Australia that each of us can be proud of, then your time to act is now.

But how? The key is to leverage the power of relationships and dive into conversations with your friends and relatives, especially people over the age of 55, who are currently the most likely to vote No. That’s your parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, or if you’re in that age group yourself, your childhood friends or neighbours.

If the prospect of starting a “political” conversation with family members fills you with dread, that’s understandable. These conversations often succumb to pitfalls that only increase animosity and polarisation. But get them right and they can be transformational. If you’re brave enough to strike up a conversation over the dinner table, here’s how to do so constructively. In fact, these tips can help you have better conversations regardless of how you intend to vote.

First: show respect. It’s all too easy (and, in some circles, encouraged) to believe that those who disagree with us must be either stupid or malicious. Sometimes they are. But signalling disrespect is a surefire way to kill any possibility of persuasion. Even the faintest whiff of disrespect triggers defensiveness, and when that happens, constructive conversation is over.

One way to show respect is to hold your tongue and listen – really listen. Often, people get belligerent because they don’t feel heard. That means two of the biggest tools in your arsenal are your ears. Just listening carefully, asking a few questions and repeating back a summary of what they have said can be transformative. It makes them feel heard and it gives you a fighting chance of understanding where they’re coming from.

Do this before you’ve shared your views. Our natural tendency when we hear someone say something we don’t agree with is to immediately open our mouths and tell them that we think differently. But this sets you at loggerheads from the outset. Instead, hold back. Hear them out and show you’re interested into getting to the bottom of the matter. That way it’s not a tug of war between the two of you but one where you’re on the same side pulling against ignorance.

While listening, you’re likely to hear them offer reasons to support their view. Some will be authentic, but many will be post-hoc rationalisations of deeper unstated motivations. You can spot a post-hoc rationalisation because when you show that it’s false, it doesn’t change their mind. That means it was never the real motivation for their beliefs, just a distraction.

The trick is not to challenge or fact check post-hoc rationalisations head-on but to change the way they perceive the issue in the first place. Once you’ve generated enough goodwill, offer an alternative perspective on the issue. You don’t need to encourage, let alone demand, they adopt your perspective, just offer it as your reason for voting the way you intend to.

You’re nearly done. If you’ve made it this far, you’ve done just about all anyone can do in a single conversation. Thank them and move on to something else. Let them mull over your perspective, and perhaps in the next conversation you might be able to go deeper. Minds rarely change in a single sitting.

Of course, there will be times when the conversation goes off the rails. Maybe your discipline cracks and you scoff at one of their remarks. Perhaps they refuse to engage in good faith. Maybe they just want to troll you to get a reaction. If any of these happen, back out. Focus instead on reinforcing the relationship based on other shared values – family, sport, food, whatever it is that brings you together – so perhaps in the next conversation they won’t feel the need to get defensive, or offensive.

Good conversations, particularly persuasive ones, take work. But it is possible to avoid the worst pitfalls and have a constructive discussion. If even a few unsure voters are swayed, it could shift the tide of the referendum. And given the Voice is about being heard, it’s rather fitting each of our voices could help make the difference.

An edited version of this article appears in The Sydney Morning Herald.

Image: AAP Image/Jono Searle

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 9 AUG 2023

If we are to engage with the ethical complexity of the world, we need to learn how to hold two contradictory judgements in our mind at the same time.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

– Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

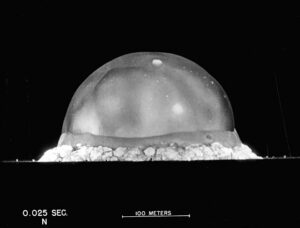

A fraction of a second after the first atomic bomb was detonated in New Mexico in 1945, a dense blob of superheated gas with a temperature of over 20,000 degrees expanded to a diameter of 250 metres, casting a light brighter than the sun and illuminating the surrounding valley as if it were daytime. We know what the atomic blast looked like at this nascent moment because there is a black and white photograph of it, taken using a specialised high-speed camera developed just for this test.

I vividly remember seeing this photo for the first time in a school library book. I spent long stretches contemplating the otherworldly beauty of the glowing sphere, marvelling at the fundamental physical forces on display, awed and diminished by their power. Yet I was also deeply troubled by what the image represented: a weapon designed for indiscriminate killing and the precursor to the device dropped on Nagasaki, taking over 200,000 lives – most civilians.

I’m not the only one to have mixed feelings about the atomic test. The “father” of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer – the subject of the new Christopher Nolan film – expressed pride at the accomplishment of his team in developing a weapon that could end a devastating war, but he also experienced tremendous guilt at starting an arms race that could end humanity itself. He reportedly told the U.S. President Harry S. Truman that his involvement in developing the atomic bomb left him feeling like he had blood on his hands.

In expressing this, Oppenheimer was displaying ethical ambivalence, where he held two opposing views at the same time. Today, we might regard Oppenheimer and his legacy with similar ambivalence.

This is not necessarily an easy thing to do; our minds often race to collapse ambivalence into certainty, into clean black and white. But it’s also an important ethical skill to develop if we’re to engage with the complexities of a world rendered in shades of grey.

In all things good, in all things bad

It’s rare that we come across someone or something that is entirely good or entirely bad. Fossil fuels have lit the darkness and fended off the cold of winter, but they also contribute to destabilising the world’s climate. Natural disasters can cause untold damage and suffering, but they can also awaken the charity and compassion within a community. And many of those who have offered the greatest contributions to art, culture or science have also harboured hidden vices, such as maintaining abusive relationships in private.

When confronted by these conflicted cases, we often enter a state of cognitive dissonance. Contemplating the virtues and vices of fossil fuels at the same time, or appreciating the art of Pablo Picasso while being aware of his relationship towards women, is akin to looking at the word “red” written in blue ink. Our minds recoil from the contradiction and race to collapse it into a singular judgement: good or bad.

But in our rush to escape the discomfort of dissonance, we can cut ourselves off from the full ethical picture. If we settle only on the bad then we risk missing out on much that is good, beautiful or enriching. The paintings of Picasso still retain their artistic virtues despite our opinion of its creator. Yet if we settle only on the good, then we risk excusing much that is bad. Just because we appreciate Picasso’s portraits doesn’t mean we should endorse his treatment of women, even if his relationships with those women informed his art.

Ambivalence doesn’t mean withholding judgement; we can still decide that the balance falls clearly on one side or the other. But even if we do judge something as being overall bad, we can still appreciate the good in it.

The key is to learn how to appreciate without endorsement. Indeed, how to appreciate and condemn simultaneously.

This might change the way we represent some historical figures. If we want to acknowledge both the accomplishments and the colonial consequences of figures like James Cook, that might mean doing so in a museum rather than erecting statues, which by their nature are unambiguous artifacts intended to elevate an individual in the public eye.

Despite our minds yearning to collapse the discomfort of ambivalence into certainty, if we are to engage with the full ethical complexity of world and other people, then we need to be willing to embrace good and bad simultaneously and with nuance, even if that means holding contradictory attitudes at the same time.

So, while I remain committed to the view that nuclear weapons represent an unacceptable threat to the future of humanity, I still appreciate the beauty of that photo of the first atomic test. It does feel contradictory to hold these two views simultaneously. Very well, I contradict myself. I, like every facet of reality, contain multitudes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 13 JUN 2023

A cornerstone of ethics is our fundamental human need to be recognised for who we are and who we want to be.

When I was on the cusp of my teenage years, I discovered who I was. At least, I thought I did. For a middle-class white kid growing up on the north shore of Sydney in the late 1980s, I was surrounded by a homogeneous sameness to which I only belonged by default.

I didn’t feel any strong connection to the dominant Anglo-Australian culture: I didn’t go to church; I didn’t participate in that other religion, sport; and I only begrudgingly watched Hey Hey It’s Saturday. There was nothing there that spoke to my desire to have some grounding that could tell me who I was, what made me different.

And then I saw it, a documentary series produced by the BBC on the Celtic peoples. Despite my rather trivial genealogical association with the Celts – my ancestors originated from across the British Isles – I entirely lacked any cultural connection. Yet I had an overwhelming sense that these were ‘my people,’ and that I could connect myself to their history and culture, and share in their pride and tragedy.

I hastily bought a Celtic cross pendant. I read folk tales of Lugh of the Long Arm and the Tuatha Dé Danann. And, most pretentiously, I started correcting people about my ethnicity, identifying not as Australian or Anglo, but as a proud Celt. I was insufferable.

But this connection to a people and a culture stirred something within me. It satisfied a deep need to belong to something larger than myself, yet it was also something that set me apart from those around me. It gave me an identity.

A few years later, when I was on the cusp of adulthood, I lost that Celtic cross in a field somewhere in Byron Bay, and the cringe that I felt about replacing it forced me to revisit my appropriated identity and ask whether this was really me. It prompted me to reflect on who I was and who I wanted to be, and sparked a journey to build a new identity – a journey that is ongoing.

Identity crisis

Herein lies one of the great challenges of the modern world. Unlike our ancestors, who knew exactly who they were by virtue of the communities they were born (and died) in, the postmodern condition is that our identity is not handed to us: it’s left for us to discover – or to create.

This is both liberating and a curse. It’s liberating because our ancestors had little power to challenge their identity, especially if it ran against the current of their cultural norms. Their free ticket to belong came with no refunds.

The postmodern condition is a curse because we’re effectively dropped into the most diverse, fragmented and generally anxiety-inducing cultural morass in the long history of our species, and left to figure out how to piece together an identity without even a pamphlet to instruct us on how to do so.

Adding to the challenge is the existence of countless religions, corporations, sub-cultures, grifters, conspiracy theorists and self-help book authors who are only too eager to recruit you into their ranks, whether it’s to your benefit or not.

Yet build an identity we must. We are perhaps unique among the animals for having a reflective sense of who we are. We tell ourselves stories about ourselves, and these stories recursively influence who we are. Despite thinkers from the Buddha to David Hume arguing – quite persuasively, in my opinion – that there is no stable ‘self’ at the core of our identity, it’s almost impossible to live without some narrative that explains who we are and directs us towards who we want to be.

The ethics of recognition

Our identity doesn’t just play a descriptive role, explaining who we are, it plays a normative role too. It’s the seat of our dignity, the home of our values and defines what, and who, we stand for.

This is why identity is of central importance to ethics. Indeed, some thinkers, such as Georg Hegel, and Francis Fukuyama after him, have argued that a key feature of ethics is a fundamental desire for recognition. Both draw on the Ancient Greek concept of thymos, a term borrowed from Plato, which represents the spirited part of human nature that seeks recognition of its dignity.

They argue that our desire to be recognised as authentic human beings, with desires, values, rights and an inherent sense of pride based on the identity we choose for ourselves, is one of the driving forces of history, not least politics. Fukuyama famously argued that the arc of history bent towards liberal democracy, rather than any other political ideology, because it best satisfies our desire for recognition.

Yet our desire for recognition is not limited to our personal identity; it also applies to our group identities. This is behind the rise of so-called ‘identity politics,’ where individuals vote on behalf of the groups to which they belong rather than purely for their own self-interest. After all, you can’t truly understand who someone is without also understanding all the groups to which they belong.

Identity is powerful, which is why The Ethics Centre is exploring its ethical dimensions in this special series of articles. We’ve invited philosophers and commentators to tease out how identity influences our ethical views, looking at how the search for recognition is shaping the modern world and how it’s proving to be a liberating force but also a stifling one. We’ll be examining issues across politics race, culture, gender, sexual identity, and more.

We don’t assume we’ll be able to solve these issues here, but what we can do is help reveal how so many of the seemingly disparate ethical challenges of our time are grounded in one driving force: our desire to know ourselves.

This article is part of our Why identity matters series.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 1 JUN 2023

A truly ethical life requires that we let go of cynicism and strive for a better world.

Long after we’ve forgotten the gags, the on- and off-field shenanigans, and even most of the characters’ names, I suspect we’ll still remember how watching Ted Lasso made us feel.

That’s what makes this American sitcom about an endlessly optimistic NFL coach making the most of an English football team so remarkable today. It’s a show that subverts our expectations about what a typical TV show is all about. Instead of commenting on the ills of the world, or just making fun of them, Ted Lasso – both the character and the show – is devoid of cynicism.

Besides being a refreshing break from the bleak TV that populates our streams, there’s an important ethical message lurking behind Ted’s blunt moustache: in order to become better people and make the world a better place, we need to let go of cynicism.

Cynicism is rife these days. Largely for good reason. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed at the sheer number and scale of the problems we face today. And it’s easy to lapse into despondency when those in power repeatedly fail to address them. Add to this the increasingly polarised political atmosphere, and the growing sense that the “other side” is not just wrong but is morally bankrupt, and it’s easy to lose faith in human goodness altogether.

Given that popular storytelling is often a reflection of the time we’re living in, it’s no coincidence that it, too, has given over to cynicism. Series like Game of Thrones, White Lotus, Succession, House of Cards and Curb Your Enthusiasm depict duplicitous individuals who are far more consumed by expanding their power and/or covering up their insecurities than changing the world for the better or lifting up those around them.

We relate to these shows. We love to hate the Machiavellian villains. But this kind of storytelling comes at a moral cost. When art only acts as an exaggerated mirror, and only reflects back the worst of our nature, it’s no wonder that we have come to regard any magnanimous gesture with suspicion and any appeal to right the world’s wrongs as being naïve or in vain.

This is the heart of cynicism: a fundamental lack of faith in others’ intentions, an abandonment of hope that the world can be made better, as well as a tacit acknowledgement that we’re powerless to fix any of this ourselves.

The first Cynical age

Cynicism is not unique to our time. There have been other cynical ages, including the one in which the term was coined.

In the late fourth century BCE, corresponding with the rise to power of Alexander of Macedon, Greece also slipped into an age of cynicism. Prior to Alexander, Greece was a land of innovation, progress and (at least for a certain class of Greeks) seemingly boundless possibilities, driven by greater political participation by the people in city states like Athens.

Greek philosophy in the times before Alexander reflected that sense of empowerment and optimism. Thinkers from Pythagoras to Plato debated topics like justice, love, virtue and how to build the perfect state. They acknowledged human failings, but they believed we could – and should – rise above them.

But when Alexander and his successors shifted political power from individuals to concentrate it in the hands of a glory-seeking elite, philosophy shifted also. As Bertrand Russell put it in his History of Western Philosophy, philosophers “no longer asked: how can men create a good State? They asked instead: how can men be virtuous in a wicked world, or happy in a world of suffering?”

During this post-Classical era, four main schools of thought emerged from Greek thinkers, each with its own spin on how to cope in a corrupt world. Epicurus taught that happiness comes from diminishing our desires and learning to accept mortality. The Stoics believed that liberation from suffering came from within, cultivated by personal wisdom and self-control. The Sceptics gave up on the idea of truth altogether. And the Cynics – from whom we get the modern term – rejected all social conventions, including wealth, status or even basic material goods, in favour of living in accordance with raw nature.

It’s probably no coincidence that during our own time, when many of us feel a growing sense of powerlessness to fix the world’s ills, utopian visions have given way to a resurgence of these views. Indeed, Stoicism is undergoing a boom today. It seems many of us have given up trying to change the world for the better. Instead, we’re trying to adapt ourselves to cope with the way it is.

In walks Ted

Ted Lasso represents the peak in a growing trend against cynicism in media, the vanguard of which were Parks and Recreation, Schitt’s Creek and The Good Place. These are shows that subvert the typical formula of modern storytelling. Instead of depicting exaggerated versions of people at their worst, they show us exaggerated versions of people at their best. They tell stories where virtues like positivity, charity and forgiveness are not weaknesses that will be exploited by others but are strengths that help overcome the challenges we face.

That takes courage on behalf of the showrunners. It risks people dismissing uncynical shows as being unrealistic. And of course they are unrealistic, but no more so than the cynical series. But where many shows today are purely about illuminating and critiquing the ills of the world, they have little interest in offering solutions. Non-cynical shows, on the other hand, accept the critique has been made but offer us something ambitious to aim for.

Ethics requires moral imagination, which is the ability to picture the full range of possible choices open to us. And cynicism kills moral imagination. As author Sean P. Carlin puts it, “the stories we tell about the world in which we live are only as aspirational—and inspirational—as the moral imagination of our storytellers.”

Ted Lasso expands our moral imagination. Instead of dismissing people as only being self-interested or cruel, we can picture them as struggling with their own demons and offer them help.

Rather than only seeing the bleakest version of our future, moral imagination encourages us to see the world we want to live in and work towards making it happen, not ignoring the challenges we face but motivating us to overcome them.

While Ted Lasso is paradigmatically non-cynical in the modern sense, there is an interesting hint of the original philosophical Cynicism in the character of Ted. Like Diogenes, the paragon of Cynicism in the ancient world, Ted rejects the conventional metrics of success defined by the society around him. He’s uninterested in wealth or status, and justice to him means more than revenge. He repeatedly, and seemingly authentically, asserts that it’s not winning or losing that matters to him, it’s helping his players be the best versions of themselves they can be.

He also goes through his own arc to embrace another aspect of ancient Cynicism: shamelessness. The Cynics believed that conventions and social norms were bunk. Thus, they felt no shame, because they felt no discomfort in violating social expectations that they dismissed as vacuous. Likewise, Ted goes through his own journey with his anxiety, eventually opening up about it and demonstrating his contempt for norms that would shame him for it.

But Ted Lasso also transcends ancient Cynicism, just as it illustrates a better path than ancient Stoicism. It’s not just about how individuals can come to thrive by learning to cope in a disappointing world. It’s about how assuming the worst about others, and falling into the trap of suspicion and defensiveness, contributes to making the world even more disappointing.

Ted Lasso is not just entertaining. It carries an important ethical message about the virtue of releasing ourselves from cynicism. Yes, it’s unrealistic, but it reminds us that it’s worth having something to aim for, even if it’s likely to forever remain just out of reach.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Deontology

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Critical thinking in the digital age

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 1 MAY 2023

We have a well-worn script for how to behave when a public figure does something wrong. What we don’t have is a script for what to do if they make amends.

First comes the outrage, then the sharing, then the public condemnation, where the force of thousands of indignant wills declare that the wrongdoer is no longer a member of our moral community. Then we cancel.

This script is powerful. It is predictable. It helps remove a perceived threat. But it doesn’t heal the moral wound. It doesn’t rebalance the scales. It doesn’t include lines for rehabilitation, re-education or rebuilding moral capital. The script only tells us how to push people out.

What we need is another script, one we can use if they make amends. If the wrongdoer owns what they’ve done, if they express genuine contrition and issue a heartfelt apology, if they demonstrate a lasting change to their behaviour for the better, what do we do?

The missing script

The first thing to decide is whether we’re in a position to forgive at all. There are a couple of reasons why we might not be. For a start, we might not even be the right person to judge in the first place.

Many of us are quick to judge these days. The media and internet have opened us up to a world of outrages that call out for condemnation, and the frantic pace of modern discourse makes us feel like we must have an opinion on every issue. We are also often motivated to show solidarity with our in-group by sharing outrage over the same subjects, even if we know little about them. And the logic of second-order punishment – where we punish those who refuse to punish wrongdoers – means we fear retribution from our own team if we don’t jump on the outrage train.

But none of these are good reasons to jump to a hasty conclusion, based on a news headline, a couple of tweets and a few second-hand hot takes. Many of the issues we face are more complex than can be understood, let alone judged, without careful consideration. Many of the details are hidden from our view or veiled by the hasty or biased interpretations of others.

The second reason as individuals we might not be in a position to forgive is that sometimes the only person who can forgive is the individual who was harmed. I can’t unilaterally forgive a thief for stealing from you, or a celebrity for cheating on their partner. I simply lack the standing to speak on behalf of the person who was harmed.

However, there are cases where we, as members of a moral community, can be in a position to judge – and forgive – an act of wrongdoing. Acts of stealing or infidelity don’t just harm the victims, they violate the norms of our community. That’s why we still get outraged at things that don’t impact us directly or offensive acts that have no apparent victim.

This is a different kind of forgiveness. It’s not speaking on behalf of the victim, it’s speaking on behalf of the moral community. If the wrongdoer apologises and makes amends to those they’ve harmed, the community can accept that apology, drop the enmity towards them and welcome them back into the fold.

This kind of “public forgiveness” is an important part of a healthy moral community. Without it, the community pursues a purity culture that only knows how to push people out.

Set the bar

The next thing we should ask ourselves: what would the wrongdoer need to do to justify our forgiveness?

For some wrongdoers, the answer will be “there’s nothing they can do”. There are such things like terrorist attacks, mass shootings, genocide and violent sexual assault that we might not reasonably expect anyone to forgive, especially those directly affected.

However, we need to think carefully about what is considered unforgiveable, and not allow that category to grow too large.

Only the most serious moral transgressions should be considered unforgiveable. For everything else, we need to set the bar high enough that wrongdoers must earn their forgiveness, but not so high that the pariahs will one day outnumber the pure.

Similarly, when it comes to character there may be people whose behaviour is so consistently bad that we can conclude that they are beyond redemption. But we must be very cautious about inferring too much about character from only one example of wrongdoing.

There has been a trend in recent years of leaping from outrage at a particular act – say a poorly worded tweet or an off-colour joke – to condemnation of the individual’s entire moral fibre. It’s a tendency to see the slightest slip as revealing deeper moral corruption, proving they are unworthy of forgiveness or rehabilitation.

While it’s tempting to see others as having an immutable moral fibre and painting them as either virtuous or wicked, we must remember our moral fibre is malleable. Throughout the course of our lives, our own moral views evolve with changes in our circumstances and the influence others have on us. We must believe the same of others too. This means setting a very high bar before judging character.

Open the door

Once we have set an appropriately high bar, we should invite people clear it. We should look for signs that they are aware that what they did was wrong. They should own their actions and show they can articulate how they harmed others. This involves them recognising how their act was received, even if they didn’t intend for it to be received that way.

We should also look for signs of genuine remorse, which suggests that the wrongdoer shares our negative judgement of what they did. It shows their moral standards are aligned with ours.

When assessing a public apology, we can look for “costly” gestures that make that apology more likely to be authentic. A murmured apology in private, or delivered at a curated press conference may be less authentic than an unscripted public statement. Emotion matters too, but we should recognise that not all people feel or express emotion in the same way; just because someone isn’t in tears doesn’t mean they are not sincere.

Ultimately, what is most deserving of forgiveness is not words but actions. If someone changes how they behave in an enduring way, then that’s the most reliable sign that they have realigned their values to accord with those of the community. At that point, we should be inclined to invite them back into the moral community.

The final stage of the new script for public forgiveness mirrors the script for sharing outrage. Public forgiveness needs to be expressed in public. And those witnessing public forgiveness should read that as an opportunity to re-evaluate their own judgements of the wrongdoer and decide if they, too, are ready to forgive.

There are times when condemnation is justified. There are times when people ought to be cancelled. But if it’s a one-way street, we risk living in a culture where the circle of what – or who – is acceptable is forever shrinking. We need to have a pathway to redemption and forgiveness, and that pathway needs to become a script that we can all apply.

For a deeper dive on Cancel Culture, David Baddiel, Roxane Gay, Andy Mills, Megan Phelps-Roper and Tim Dean present Uncancelled Culture as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

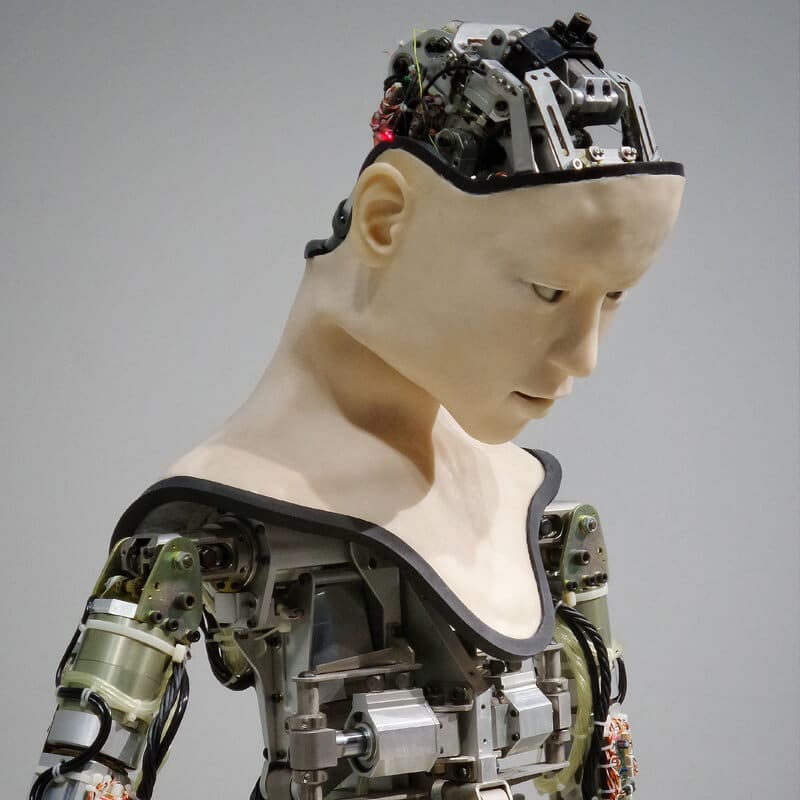

AI is not the real enemy of artists

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 2 FEB 2023

Artificial intelligence is threatening to put countless artists out of work. But the greatest threat to artists is not AI, it’s capitalism. And AI could be the remedy.

“Socrates taking a selfie, Instagram, shot outside the Parthenon, wearing a white toga, white beard, white hair, sunlit.” That’s all the AI image generator Stable Diffusion needed to create the cover image for this article.

But instead of using artificial intelligence, I could have hired a photographer or purchased an image from a stock library to adorn this article. In doing so, I would have funnelled money to a human, who might have spent it on something else created by another human. Instead, I used AI, and no money left my pocket to flow through the economy.

And therein lies the threat posed by artificial intelligence to artists: when AI can produce nearly endless creative works at near zero marginal cost, what will this mean for people who make a living via their artistic talents?

While people have lamented the prospect of AI destroying jobs for years, the discussion has remained largely theoretical. Until now. With the advent of generative AI tools that are readily available to the public, like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E and ChatGPT, the prospect of massive job losses in creative industries is rapidly becoming a reality. Not surprisingly, many creative workers – including artists, illustrators, photographers and copywriters – are fearful for their livelihoods, and not without reason.

If we believe that creative expression is inherently meaningful, and the works it produces are intrinsically valuable, then this assault on artists’ jobs would be a net loss for humanity. It’s one thing for machines to replace labourers on farms; it’s another thing entirely for AI to empty studios of artists.

But despite all the lamentations about the impact of AI on art, when I dug deeper, I realised that it’s not really AI that poses the greatest threat to art. It’s capitalism. And instead of AI accelerating the decline of art, it could actually be the key that unshackles us from our current form of scarcity capitalism and allows art to genuinely flourish.

The alienation of art

As soon as art is brought into the market, it changes. Instead of a work’s value being defined in terms of its meaning or cultural significance, it becomes defined in terms of how much someone else is willing to pay for it. Art effectively becomes a product to be bought and sold.

Given the cost of producing art – and by “art” I mean all modes of creative expression, including music, dance, poetry, fiction, etc. – and the necessity of earning money to exchange for other goods, then art necessarily becomes professionalised.

This creates distinctions between different categories of artist. One is between those who create art for fun, so-called ‘amateurs’ (from the Latin amare, meaning “one who loves”), and those who create art for money, whom we can call ‘professionals’. The latter group, and society in general, tend to look down upon amateurs as engaging in art only frivolously or lacking the talent to make it in the competitive market.

The other distinction is among professionals, and is between those who work as commercial illustrators, designers, photographers, musicians, copywriters, etc., and the very small subset of their number, whom we might call ‘purists’, who are skilled or lucky enough to be able to produce the art they want, and can make a living out of it, either through selling to enthusiasts or collectors, or by securing grants. The purists, in turn, tend to look down on professionals as being sell-outs, or lacking the talent to make it in the rarefied art world.

The capitalist dynamic that produces these distinctions has the unfortunate consequence that many people choose not to create art at all, either because they don’t believe they are skilled enough to compete in the market, as if that were the only standard by which one might be measured, or they consider amateur art to be less than worthy. As a result of the commercialisation of art, there are likely many fewer painters, dancers, musicians and poets, than there might otherwise be.

Who’s under threat?

It’s important to recognise that when it comes to AI, it’s primarily the professionals who are at risk. These are the artists who produce the kinds of products that AI is increasingly able to create at lower cost.

AI doesn’t appear to present much of threat to purists, given that grant-givers and collectors are often spending based on the name in the corner as much as the other marks on the canvas, as it were. Purists can also do something that AI can’t: translate their personal experiences into creative expression. Amateurs are also not much at risk from AI because they don’t, for the most part, seek to derive an income from their works.

If we focus on professionals, we can see something else that the commodification and professionalisation of art have done: alienate the artist from their work.

Professionals often work to a brief defined by another person. Their art is often a means to a commercial end, such as capturing a prospective customer’s attention with a graphic or jingle, or by gussing up the interior of a restaurant. Some of this work can be deeply meaningful and rewarding, but much of it is far removed from what the artist would otherwise create were they not in dire need of money to pay the bills.

As one commenter on YouTube remarked: “As an artist I’m constantly conflicted with needing to make art that has ‘market value’ and can be sold to someone to financially support myself, and just making art for art’s sake because I want to make something that I like, and to express myself through the power of creativity.”

This alienation of the artist from the work they genuinely wish to produce has been discussed at length as far back as by Karl Marx. It’s also the reason why Pablo Picasso joined the Community Party.

It means that much of the art produced by professionals is, by its commercial nature, also helping to reinforce the very commercial system that binds it. This undermines one of the core social functions of art, which is to be a form of political expression, often employed to highlight and challenge the power structures that stifle and oppress humanity.

From this perspective, I saw that capitalism has already made the world hostile to art. AI is just worsening the situation of those have chosen to make a career out of their artistic talents.

AI acceleration

I can see two bad responses to this situation. The first is to attempt to stuff the AI genie back in the bottle. Some are attempting to do that right now, primarily through a series of court cases against some of the major generative AI companies under the pretence of copyright violation.

The outcome of these cases (assuming they are not settled or dismissed) will likely have a tremendous impact on the future of generative AI. However, it’s far from clear that US copyright law, where the cases are being held, will find that generative AI has done anything illegal. At best, the courts might require that artists are able to opt-in or opt-out of the datasets used to train AI. But even that seems unlikely.

The second bad response is to let AI run unfettered within the current economic paradigm, where it could destroy more jobs than it creates, put millions of professional artists out of work, and concentrate wealth and exacerbate inequality to an unprecedented degree. Should that happen, it’d create a genuine dystopia, and not just for artists.

The good news is that I can see at least one good solution. This is to leverage the power of AI to dramatically boost productivity and lower costs, and use that new wealth to improve everyone’s lives through a mechanism such as a universal basic income, greater subsidies or public funding, a shorter working week or a combination of them all.

I’m not alone in endorsing this idea about transforming capitalism. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, which created ChatGPT and DALL-E, has argued something very similar in an essay called Moore’s Law for Everything. In it, he states that “we need to design a system that embraces this technological future and taxes the assets that will make up most of the value in that world – companies and land – in order to fairly distribute some of the coming wealth. Doing so can make the society of the future much less divisive and enable everyone to participate in its gains.”

This would likely be a multi-decadal project, but it would set us on a course that would decouple the work that we do from the income that we earn. This could release artists from the shackles of capitalism, as they’ll be increasingly able to produce the art that is meaningful for them without requiring that it be saleable in a competitive market.

It’d also free up more time for amateurs to explore their creative potential, possibly resulting in an explosion of art. Imagine how many people would pick up a paintbrush, pen or piano if they had the time and financial security to do so.

Much of that creative output will be low quality, but that’s not the point. If we believe that the creative act is inherently valuable, then it’s worth it. Plus, there are likely many people of startling artistic talent who are currently otherwise occupied earning a living to be able to explore and develop their abilities.

The decoupling of art from the market could also help liberate its political power, enabling more artists to question, challenge and offer solutions to society’s many problems without having their livelihood threatened.

The big question is how do we get from a world where AI is stripping people of their livelihoods to one where AI is freeing them from toil? There are no easy answers to that question. But it’s crucial to focus our attention on the root cause of the problem that artists face today, and that’s not AI, it’s capitalism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 29 NOV 2022

Religious holidays like Christmas are not just for believers. They involve rituals and customs that can help reinforce social bonds and bring people together, no matter what their beliefs.

What is Christmas all about? On the one hand, it’s a traditional Christian religious holiday that celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ, the son of God. On the other hand, it’s a commercial frenzy, where people battle crowds in vast shopping centres blanketed in themed decorations to buy disposable trinkets that are destined to be handed over to disappointed relatives straining, but failing, to smile with their eyes.

Either way, if one is not overly devout or materialistic, Christmas might seem like something worth giving a miss. And if you’ve lost your religion entirely, it might seem appropriate to dispense with Christmas traditions.

The same applies for major holidays celebrated by other religions. If you do abandon Christmas – or Hanukkah, Diwali, Ramadan, etc – you’ll be missing out on an opportunity to participate in a ritualistic practice that is about more than the scriptures suggest, and certainly more than the themed commercial advertising represents.

This is because religious holidays like Christmas are not what they seem. They are not fundamentally about spirituality, as they purport to be. They’re certainly not about boosting economic activity, even if that’s what they’ve become. Rather, they’re about bringing people together to create shared meaning.

Anyone can benefit from this effect if they participate in the rituals and traditions of a religious holiday, including people of that religion who are no longer believers, as well as those outside of the culture who are welcomed in.

Do you believe in Santa Claus?

Religiosity is in decline in most countries around the globe, Australia included. In fact, Australia is in the top five nations in the world in terms of the proportion of self-declared atheists. And “no religion” is the fastest growing group, jumping from less than 1% of the population in 1966 to 38% in the latest Census figures from 2021. These numbers are even higher for young people, which suggests the move away from religion will continue into the future.

For the ‘new atheists,’ this looks like a good thing. Thinkers such as Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris famously argued that religion is dangerous force that spreads unscientific beliefs and perpetuates social divisions. They have urged people to drop their spiritual beliefs and embrace a secular rational lifestyle.

There are merits to their arguments, but their bundling of religions’ problematic metaphysics with the traditions and rituals they promote overlooks that the two are not necessarily connected: one need not believe that three wise men tracked a mystical light in the sky to the birthplace of Jesus so they could give him gold, frankincense and myrrh in order to hand over a present to a loved one. It’s like how we already agree that one need not believe in Santa Claus in order to stuff the odd stocking.

The other thing the scorched Earth version of atheism overlooks is that the decline of religiosity has corresponded with an increase in social fragmentation in the modern world. Many people feel a sense of social isolation and disconnection from those around them, even if they live in the midst of a metropolis, which is contributing to the growing crisis in mental health.

This is not a new phenomenon. A similar pattern was observed by sociologists such as Émile Durkheim and Ferdinand Tönnies in the late 19th century. They attributed it to the rise of individualism over community as modern societies expanded following the industrial revolution. The erosion of community meant that individuals were left to seek their own meaning and purpose in life, as well as forge their own social connections.

This lean towards individualism affords each person some freedom in choosing what is meaningful for them, but it also involves a lot of work; it’s no mean feat to single-handedly create a grand structure to make sense of the world, to inform what we should value and what morals we should abide by. And there are many forces that are only too happy to sell their own vision to the individual, including all manner of pseudo-spiritual causes, conspiracy theories and self-help gurus. But the strongest force today is capitalism, which sells a vision of work and consumption that is superficially appealing but which many find to be ultimately hollow and unfulfilling.

One of the mechanisms sociologists identified that helped to ameliorate the individualistic tendency towards social disconnection and isolation was religion. But it wasn’t the spiritual dimensions of religion that did the most work, it was the rituals and traditions that brought people together to reinforce social connections and create shared meaning.

Rituals like gathering for an annual feast with family, which signifies a break from everyday consumption and gives us an opportunity to show care and respect for others as we feed them. Or gift-giving, which motivates us to think carefully about the most important people in our lives – who they are, what they care about, what they lack – and encourages us to find or make something, or use our wealth, to bring them joy. Even singing carols has an effect. The act of singing in unison is a potent way of bonding with those around us, and even the habit of complaining about our most hated Christmas tunes can bring people together.

Come together

There are many more rituals involved with Christmas, and many analogous rituals associated with the festivals of other religions.

While their surface details and spiritual justifications may differ, at their heart they’re all about one thing: bringing us closer together. They’re a form of social glue that is arguably much needed in today’s world.

While the differences between traditions can be a source of division, and the rise of multiculturalism and sensitivity towards other cultures can be a source of reservation when it comes to participating in rituals that are not ‘our own,’ we still have a lot to gain by continuing to practise festive rituals, even if we no longer subscribe to their supernatural pretexts. We also have a lot to offer if we welcome those of other cultural and religious traditions to share our rituals, and if we remain open to learn from and share in theirs.

On the surface, Christmas looks like it’s about spirituality or like it’s been co-opted by the market. But deep down, it’s one of many religious festivals that we can draw on to enrich our lives, ground ourselves in our family and community, and a way to create meaningful experiences with others to help us all live a good life.

Join Dr Tim Dean for The Ethics of Holidays on the 8th of December at 6:30pm. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Tim Dean 9 NOV 2022

Many believe that sport transcends politics. But it can also be used as a political tool to distract attention from human rights abuses, making sportspeople and fans complicit.

Legions of football fans with faces daubed in their national colours fill the spotless new stadium and explode into a roar when their team lands the ball in the back of net at the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar.

From the promotional video alone, the scene seems to exemplify what people love about big sporting events: the emotional highs and lows; the vibrant carnivale atmosphere; the fierce competitive spirit; the skill of the athletes.

But to the millions of migrant workers in Qatar, many of whom helped build the very stadiums that are to host the games, the World Cup likely means something very different.

Qatar has long been criticised for the kafala system of sponsorship-based employment for foreign workers, which has led to underpayment, wage theft and unsafe working conditions, leaving workers powerless to change their employment circumstances. Qatar also has a history of women’s oppression, with women requiring permission from a male guardian to exercise many basic rights, such as pursuing higher education, working in certain jobs or traveling abroad. LGBTI people have also been subject to discrimination and abuse in the country, even on the lead-up to the World Cup.

So it is no accident Qatar is spending billions to host the World Cup, with estimates suggesting the government has pumped over $US 220 billion into the event – more than fifty times what Germany spent in 2006 when it hosted.

This is ‘sportswashing.’ The Qatari government is hoping it can appropriate the positive associations fans have with football to elevate its own status on the international stage and distract from its ongoing human rights violations.

And Qatar is not alone in the practice: Saudi Arabia, another nation with a problematic human rights record, has spent over $US 2 billion on its LIV Tour for golf; and China, criticised for its ongoing persecution and internment of its Uyghur minority, spent billions hosting the 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

But what’s so bad about a country with a troubling human rights record supporting or hosting an unrelated sporting competition? Does watching or travelling to that country to attend the competition make spectators complicit in human rights abuses? And shouldn’t sport be kept separate from politics? To answer these questions, we first need to be clear about what sportswashing is.

What is sportwashing?

Sportswashing refers to states – sometimes individiuals or corporations – that seek to use sport to bolster their image by distracting from their wrongdoing. It’s typically not just a matter of hosting games or supporting a national team but rather pumping money into sport specifically to change people’s attitudes about them.

Why sport?

Sport is more than just entertainment. It exemplifies what many people believe to be noble or aspirational virtues: discipline, hard work, individual excellence, teamwork. For spectators, sport generates intense feelings of belonging and a shared identity that verges on the sacred; a win for one’s team elevates oneself and one’s whole community. Sport also reaches a wide audience, including people who may not actively follow politics or world affairs.

So if a regime wants to bolster its reputation around the world, it’s hard to beat tapping into the positive associations people have with sport, especially high profile sports like golf, football or the Olympics. And all you need to do it is enough money. But what does all this money really achieve?

First impressions

What springs to mind when you think of Qatar? For many people whatever it is will be informed by what’s in the media. And if the media has been focusing on Qatar’s human rights violations, it’s these that can define their impression of the country.

This is why nations like Qatar are so keen to offer you new impressions. One function of sportswashing is to saturate the news – and internet search results – with topics other than human rights. If people know little about Qatar, and the World Cup pushes its human rights violations to the second page of Google’s search results, then fewer people will be made aware of them.

There’s another upshot of sportswashing: given many people have powerful feelings about sport, if the majority of the news they hear about Qatar is connected to their beloved game, then their feelings for sport can bleed over into their impression of the country.

Once that positive connection with sport is established, it can come to clash with negative associations they have about human rights violations, causing cognitive dissonance, which describes a tension between two opposing ideas. Most people tend to dislike the feeling of dissonance and will seek to eliminate it, often by ejecting one of the dissonant thoughts. Sportswashing nations hope that the ejected thought is the one about human rights rather than sport.

This is where sportswashing becomes ethically problematic. To the degree that it distracts from wrongdoing, such as human rights violations, it can contribute to the perpetuation of that wrongdoing. Countries are often motivated to enact reforms when they experience pressure from other states, especially large democractic states that are reacting to internal public pressure. If the population is distracted by sport, then public pressure can wane.

Just not cricket

Sportswashing is insidious, as it co-opts something that is otherwise benign and makes those who innocently endorse it complicit in achieving a political end.

But just because someone was not aware of, or chose to ignore, the political dimension of the sporting event, that doesn’t mean they are absolved of responsibility. Sadly, sportswashing makes anyone involved in it complicit to some degree.

If we believe that our ethical obligations extend to those parts of the world that we affect through our actions, then we must consider how our spectating or participating in a sportswashing event might contribute to perpetuating human rights abuses. If we are paying to attend a sportswashed event, we are contributing financially to enabling that event to take place, and through our attendance, we are normalising that activity for others.

There is an even greater ethical weight placed on the shoulders of sportspeople, who are often viewed as role models and whose behaviour can be seen to normalise certain values. This is why we place such emphasis on sportspeople behaving responsibly on and off the field, such as in nightclubs or in their private relationships.

If a sportsperson accepts money to participate in a sportswashed event, that sets a standard for others. And if they are aware of the ethically problematic nature of their hosts, then this opens them to a charge of hypocrisy, as in the case of Phil Mickelson, one of the world’s top golfers, who accepted $US 200 million to join the LIV Tour despite admitting he was aware of Saudi Arabia’s “horrible record on human rights”.

Washing sport

However, there are ways of pushing back against sportswashing. The first is to refuse to support it financially, such as by not buying tickets to the events or subscriptions to the coverage in the media. For some, this will mean missing out on watching a sacred sporting event, and it’s important not to understate how big a cost that might be for them.

However, if they choose to watch, they can consider how to reduce or nullify the impact of the sportswashing. That could involve informing themselves and others about the true state of affairs, reducing the informational distortion caused by sportswashing. In fact, there is evidence that Qatar’s World Cup sportswashing gambit may be backfiring by drawing attention to the very human rights issues it hopes to distract from.

Sportspeople have an even greater responsibility but also a greater potential impact for good. Some have refused to participate in sportswashed events, such as golfer Tiger Woods, who reportedly turned down an offer in excess of $US 700 million to join the Saudi-backed LIV Tour.

In some cases, participating in a sportswashed event can be offset if the individuals work to counter the sportswashed narrative, as in the case of the Australian Soccerros, who released a protest video about human rights in Qatar. While they are playing in the World Cup, they have used their platform to support migrant workers and the decriminalisation of same-sex relationships in Qatar. Football Australia also released a similar written statement. Arguably, more Australians now know about Qatar’s human rights record than if the state had never been chosen to host the World Cup.

When states are involved in funding sport, then sport can no longer be said to be removed from politics. Through sportswashing it becomes a political tool. If we want to maintain sport as a pure and sacred pursuit, then we must consider how we choose to engage with it and how we might avoid or counteract the power of sportswashing to distract or normalise wrongdoing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Kimberlé Crenshaw

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

An angry electorate

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights