AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 27 FEB 2024

It’s no secret that the world’s largest and most powerful tech companies, including Google, Amazon, Meta and OpenAI, have a single-minded focus on creating Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Yet we currently know as little about what AGI might look like as we do about the risks that it might pose to humanity.

It is essential that debates around existential risk proceed with an urgency that tries to match or eclipse the speed of developments in the technology (and that is a tall order). However, we cannot afford to ignore other questions – such as the economic and political implications of AI and robotics for the world of work.

We have seen a glimmer of what is to come in the recent actors’ industrial action in Hollywood. While their ‘log of claims’ touched on a broad range of issues, a central concern related to the use of Generative AI. Part of that central concern focused on the need to receive equitable remuneration for the ongoing use of digital representations of real, analogue (flesh and blood) people. Yet, their deepest fear is that human actors will become entirely redundant – replaced by realistic avatars so well-crafted as to be indistinguishable from a living person.

Examples such as this easily polarise opinion about the general trajectory of change. At one end of the spectrum are the optimists who believe that technological innovation always leads to an overall increase in employment opportunities (just different ones). At the other end are the pessimists who think that, this time, the power of the technology is so great as to displace millions of people from paid employment.

I think that the consequences will be far more profound than the optimists believe. Driven by the inexorable logic of capitalism, I cannot conceive of any business choosing to forgo the efficiency gains that will be available to those who deploy machines instead of employing humans. When the cost of labour exceeds the cost of capital the lower cost option will always win in a competitive environment.

For the most part, past technical innovation has tended to displace the jobs of the working class – labourers, artisans, etc. This time around, the middle class will bear at least as much of the burden. Even if the optimists are correct, the ‘friction’ associated with change will be an abrasive social and political factor. And as any student of history knows, few political environments are more explosive than when the middle class is angry and resentful. And that is just part of the story. What happens to Australia’s tax base when our traditional reliance on taxing labour yields decreasing dividends? How will we fund the provision of essential government services? Will there be a move to taxing the means of production (automated systems), an increase in corporate taxes, a broadening of the consumption tax? Will any of this be possible when so many members of the community are feeling vulnerable? Will Australia introduce a Universal Basic Income – funded by a large chunk of the economic and financial dividends driven by automation?

None of this is far-fetched. Advanced technologies could lead to a resurgence of manufacturing in Australia – where our natural advantages in access to raw materials, cheap renewable energy and proximity to major population areas could see this nation become one of the most prosperous the world has ever known.

Can we imagine such a future in which the economy is driven by the most efficient deployment of capital and machines – rather than by productive humans? Can we imagine a society in which our meaning and worth is not related to having a job?

I do not mean to suggest that there will be a decline in the opportunity to spend time undertaking meaningful work. One can work without having ‘a job’; without being an employee. For as long as we value objects and experiences that bear the mark of a human maker, there will be opportunities to create such things (we already see the popularity of artisanal baking, brewing, distilling, etc.). There is likely to be a premium placed on those who care for others – bringing a uniquely human touch to the provision of such services. But it is also possible that much of this work will be unpaid or supported through barter of locally grown and made products (such as food, art, etc.).

Can we imagine such a society? Well, perhaps we do not need to. Societies of this kind have existed in the past. The Indigenous peoples of Australia did not have ‘jobs’, yet they lived rich and meaningful lives without being employed by anyone. The citizens of Ancient Athens experienced deep satisfaction in the quality of their civic engagement – freed to take on this work due to the labour of others bound by the pernicious bonds of slavery. Replace enslaved people with machines and might we then aspire to create a society just as extraordinary in its achievements?

We assume that our current estimation of what makes for ‘a good life’ cannot be surpassed. But what if we are stuck with a model that owes more to the demands of the industrial revolution than to any conception of what human flourishing might encompass?

Yes, we should worry about the existential threat that might be presented by AI. However, worrying about what might destroy us is only part of the story. The other part concerns what kind of new society we might need to build. This second part of the story is missing. It cannot be found anywhere in our political discourse. It cannot be found in the media. It cannot be found anywhere. The time has come to awaken our imaginations and for our leaders to draw us into a conversation about whom we might become.

Want to increase our ethical capacity to face the challenges of tomorrow? Pledge your support for an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics. Sign your name here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 6 FEB 2024

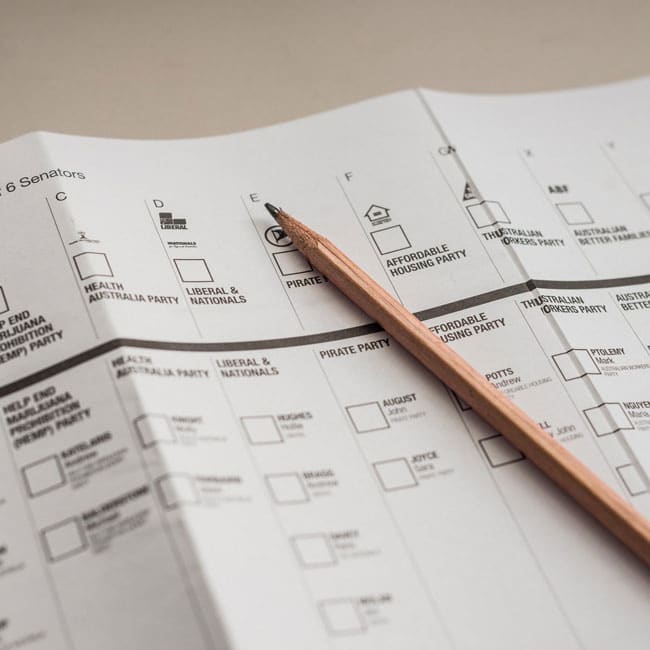

The decision by the Albanese Government to amend the form of the ‘Stage Three Tax Cuts’ – in breach of a much-repeated election promise – has not only unleashed the predictable storm of criticism from the Federal Opposition. More seriously, it has once again raised the question of integrity in politics. Yet, this is a rare case where a broken promise is in the public interest.

The making and breaking of political promises have a special significance in democracies like Australia. Governments derive their legitimacy from the consent of the governed – and consent is meaningless if it is the product of misleading or deceptive information. That is why politicians who deliberately lie in order to secure power should be denied office. It is also why prospective governments should be extremely cautious when making risky promises.

Yet, to argue that ‘keeping promises’ is an essential aspect of building and maintaining trust and legitimacy does not entail that a promise must be kept under any and every circumstance. There may be times when it is literally impossible to keep one’s word – for example, when a government commits to build a facility in a specific location that is later destroyed in a flood. And then there are circumstances where the context is so fundamentally altered as to make the keeping of a promise an act of folly or worse, irresponsibility. President Zelensky is bound to have made many promises to the people of Ukraine prior to the Russian invasion – at least some of which it would be irresponsible to keep in the middle of a war that threatens the very existence of the State.

Some people – notably those who adopt consequentialist forms of ethical reasoning – will argue that a promise should always be broken if, by doing so, a superior outcome is achieved. Others – notably those who place a higher value on acting in conformance with duty (irrespective of the consequences) – will argue that promises should never be broken. I am not inclined to line up with the ‘purists’ on either side. Instead, I prefer an approach in there is acceptance – across the political spectrum – that:

- There is a clear presumption in favour of keeping promises.

- Promises may be broken, but with extreme reluctance, when genuinely in the public interest to do so. That is the breach cannot be justified because it advances the private political interests of an individual or party.

- Any breach must be only to the extent necessary to realise the public interest – and no more.

- Those who break a promise should publicly acknowledge that to do so is wrong and that they are responsible for this choice. That is, they should not seek to deny or lessen the ethical significance of their choice.

Let’s consider how these criteria might be applied in the case of the ‘Stage Three Tax Cuts’.

The key question concerns whether or not it is demonstrably in the public interest to amend the legislated package as it stands. This question cannot be answered by looking at the economic and social implications alone. There is a real risk that trust in government will be eroded – even amongst those who benefit from the changes. And that further erosion in the ‘ethical infrastructure’ of the nation harms us all – not least because of its own tangible economic effects. So, that fact must be weighed in the balance when evaluating the public interest. However, Australia’s ethical infrastructure is also weakened by widening inequality – and by a growing sense of desperation amongst those who feel that their struggles are as much a product of unfairness as they are of forces beyond anyone’s control.

We should never forget that the current cost of living crisis is a form of ethical failure. It was neither inevitable nor necessary. At its root lie the choices made by those who control the levers of economic and political power. As things stand, the community does not trust them to ensure an equitable distribution of burdens and benefits. That widespread popular sentiment is reinforced by daily experience. Ethics – which deals with the way in which choices shape the world we experience – lies at the heart of the current crisis.

So, if changes to the ‘Stage Three Tax Cuts’ can be shown to tilt the table in favour of a more fair and equal Australia, it will have a strong claim to be in the public interest – not least by demonstrating that power can be exercised for the good of all rather than the influential few. Thus, some measure of trust and democratic legitimacy might be restored.

Two final points. First, even with the changes, every Australian taxpayer will continue to be better off than the day before the changes come into effect. To that extent, the policy satisfies the third of the conditions listed above.

Which brings me to the final test: will the Prime Minister and his colleagues accept that the breaking of a political promise is wrong-in-itself – even if necessary to advance the public interest? That would be the brave thing to do. It would involve Anthony Albanese in acknowledging one of the toughest problems in political philosophy – the problem of ‘dirty hands’. This is when a person of principle, as Albanese clearly is, decides to accept the burden of violating their own, deepest ethical sense for the good of others. Then their sense of the moral injury they do to themselves exceeds the bounds of all criticism directed to them by others. They are wounded – and they let us see this.

I believe Anthony Albanese when he says that ‘his word is his bond’. Now, he must own this commitment and acknowledge the cost he and his government must bear in serving the public interest. That will not spare him the pointed criticism of political opponents or of those who sincerely feel their trust betrayed or their interests diminished. However, that honest reckoning is the sacrifice a good person must sometimes make in order better to serve the people.

Image by Mick Tsikas, AAP Photo

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 25 JAN 2024

The recent dispute between Antoinette Lattouf and the ABC has brought into focus the need to address some fundamental questions about the role of journalism, in general, and professional journalists, in particular.

In my opinion, journalism is (or at least should be) practiced as a profession. This is not to ignore the fact that journalists work within an intensely commercial environment. But so do those lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and others who are employed by the private sector. For members of these professions, the fact that they work for, say, ‘industry’ in no way reduces the scope or depth of their professional obligations.

What marks out a profession is first, that its members are obliged to subordinate self-interest in the service of a public good. For example, as Officers of the Court, lawyers are bound by a paramount duty to assist in the administration of justice. This obligation comes before any duty to the client, to the profession or to oneself. Second, each profession exists in relation to its own ‘defining good’. Doctors and nurses work to secure the public good of ‘health’. Members of the profession of arms are supposed to secure the defining good of ‘peace’. Engineers aim for safety, etc. Two professions are oriented towards the good of ‘truth’ – accounting and journalism.

In both cases, the value of ‘truth’ is not in any sense vague or abstract. The preparation of accounts that are ‘true and fair’ is essential to the operation of free markets in which participants make informed decisions. As Adam Smith understood so well, markets can never be ‘free’ if participants lie, cheat, or use power oppressively. Yet, Smith also knew that merchants were always liable to employ such tactics in pursuit of self-interest. Thus, the need for the profession of accounting – made up of people who freely choose to abandon the pursuit of self-interest in service of the public interest and a higher ‘good’.

The role that accountants play in markets is mirrored by the role that journalists play in politics – and especially in democracies. The legitimacy of liberal democracies rests entirely on the consent of the governed. The only consent that counts is that which is free, prior and informed. And consent can never be informed if it is based on lies. That is why those politicians who resort to falsehood in the pursuit of power do so much damage to our democracy.

Unfortunately, just as some merchants can be relied upon to resort to deception in the pursuit of profits, so can some politicians be relied upon to do the same in the pursuit of victory. Professional journalists are supposed to help protect society from that risk – which is why they are so often lauded as the ‘fourth estate’.

I realise that there are some people who claim the title of ‘journalist’ while playing their own part in publishing or broadcasting falsehood, or who lack the ‘disinterested gaze’ that should be demanded of members of this profession. Yet, the fact that some (or even many) fail to uphold professional standards does not mean that the standard is either wrong or pointless.

Now, one might hope that those in charge of the ABC would champion the ideal of professional journalism as outlined above. If so, then you might also hope that they understood what is entailed by commitment to such an ideal. Finally, one might hope that the ABC would have discerned that a core commitment to the truth is fundamentally incompatible with the avoidance of controversy. Put simply, the truth is often controversial – especially when it challenges conventional belief or confronts power (which can reside in ‘settled’ ideas and prejudice as much as in the hands of individuals and institutions).

The truth is often controversial – especially when it challenges conventional belief or confronts power.

That is where I think the ABC ran off the rails. The moment it elevated the ‘avoidance of controversy’ as an end in itself, it set a standard that it is simply impossible for any professional journalist to uphold.

The noted German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, argued that “ought implies can”. That is, one is not morally obliged to do that which is impossible. This clearly applies in cases of actual impossibility (e.g. flying to Mars on the back of a bandicoot). However, I think the maxim also extends to cases where something is ‘impossible’ to do without violating the dictates of a well-informed (and well-formed) conscience. It is in this sense that professional journalists are placed in an impossible position if required to seek and publish the truth without ever courting controversy.

Image by Pat M2007

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

A note on Anti-Semitism

I was recently proud to join hundreds of others in signing an open letter condemning Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and all other forms of discrimination.

The fact that such a letter needed to be written is deeply troubling. However, the world has been witness to the horrific consequences of remaining silent when the beast of race-based hatred begins to stir.

The great attraction of the statement I signed lay in its embrace of a positive principle that extends to every person – irrespective of their identity, conduct or circumstances. The principle of ‘respect for persons’ is the foundation upon which all human rights ultimately rest. It is an affirmation that every person has an irreducible, intrinsic dignity that cannot be reduced or forfeited. Although the rising incidence of Anti-Semitism may have prompted the statement, its concern extends to all who are at risk of harm.

Yet, what exactly is this harm? And how do we properly distinguish between vile acts of Anti-Semitism, on the one hand, and mere criticism on the other? For example, is holding Hamas accountable for the death of innocent non-combatants either ‘Anti-Palestinian’ or ‘Islamophobic? I think not. Nor is it Anti-Semitic to hold the State of Israel to account for acting in conformance with the laws of armed conflict. Both can be held accountable to the same standard without denying the intrinsic dignity of any individual or group.

Expressing sympathy for the plight of ordinary Palestinians, caught in the crossfire of an historically intractable dispute, does not amount to Anti-Semitism. Nor is it ‘genocidal’ to support the existence of the State of Israel (even while condemning many of the actions of its government).

Anti-Semitism is a very distinctive and potent form of evil. It denies the full and equal humanity of Jewish people – and endorses the destruction of their religion, culture, history and bodies. It has its own recognisable symbols – the Nazi Swastika, the ‘Heil Hitler’ salute (and associated symbology) – and revels in the despicable iconography of gas chambers and other elements in the apparatus of the Holocaust. It should be monitored and restrained with every ounce of energy and vigilance we can bring to bear. For where Anti-Semitism lives so there breeds all the other cesspools of hatred and despair.

So, it is unbearably sad when people loosely apply the label ‘Anti-Semitic’ on any occasion where Jewish people experience even the slightest form of annoyance, anger or discomfort.

We have been witness to an example of such ‘fast and loose’ language in the last couple of days. The ‘trigger’ incident was a decision by three actors to wear Palestinian Keffiyeh during the curtain call for Sydney Theatre Company’s opening performance of Chekhov’s The Seagull. The actors took this action without STC’s knowledge and without the support of the other cast members. Whether one agrees with the sentiment behind that statement is beside the point. In practice, they hijacked the company’s stage to make an entirely private, political statement. Now everyone else is left to pick up the pieces.

STC’s audience, supporters and donors are entitled to be annoyed by what occurred. So are the Board, management and members of the STC who had no knowledge of the planned stunt. Yet, nothing that was done on the night amounts to an act of Anti-Semitism. Naïve, perhaps. Unauthorised … certainly! Anti-Semitic … not at all.

To apply that label in the current circumstances is understandable when one considers the raw nerves and ancestral fears that are chafed in response to rising incidents of actual Anti-Semitism. However, over-reacting in this case (or others like it) brings about its own damage – especially when one part of our diverse, multicultural community bands together to boycott (‘cancel’) what it finds offensive. This approach did not help the cause of Christians and Muslims who have sought to censor those who offend or criticise. And I doubt that it will help the Jewish community. A diverse and vibrant community is made to seem monolithic in its outlook and concerns – separate from the whole.

I do not know if there are any Anti-Semites working at STC. However, I would be amazed if there were not at least some ardent critics of Israel (as there are amongst many Jewish people – the world over). But to be a critic of Israel is not the same as being an ‘Anti-Semite’. Of course, one can be both – but the distinction is vital and we all need to discern and apply the difference

Jewish people have every right to speak out when offended (a right we all enjoy). In doing so, they are often driven by fears grounded in millennia of persecution culminating in the Nazi’s ‘final solution’.

We should never be silent or indifferent in the face of Anti-Semitism. However, I fear that being fast and loose in labelling events and people as ‘Anti-Semitic’ risks undermining the significance of that terrible point in human history, which we must never do.

For the Holocaust stands for far more than the fate, alone, of the Jewish people. It is a potent warning of what horrors lurk within the human psyche and the power of that warning must never lose its place in humanity’s collective memory – for it threatens us all.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The rights of children

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 13 NOV 2023

Confronted by the horrors of war between Israel and Hamas, one is naturally drawn to those who offer moral certainty.

After all, it is repugnant to the soul to think that there is no sure ground for the revulsion we feel when confronted by the carnage unleashed on October 7th. Yet, to reject the dead hand of moral relativism does not mean that we must uncritically embrace one side or the other as being either wholly vicious or wholly virtuous.

Here, distinctions matter. For example, there is a vital difference between the Jewish people and the Government of Israel. Likewise, the Palestinian people are not defined by Hamas. When free to do so, many Jews and Palestinians are as one in criticising and condemning the actions of those, in power, who claim to be acting in their name. So, in our search for ethical clarity, we need tools to produce certainty while allowing us to discern relevant distinctions.

By way of background, I should mention that I have been teaching military ethics, both at home and abroad, for more than three decades. In that time, I have typically dealt with what occurs at the ‘pointy end’ of warfighting – with people of all ranks and many cultures. This has included sitting with generals, most of them active operational commanders, from twenty-five nations, as we have discussed some of the most challenging issues ever to be encountered by those who serve in the profession of arms. In the course of my work in this area, we have naturally focused on the requirements of Humanitarian Law and Just War Theory. Those requirements are routinely quoted at times such as these. However, I think that there are even more fundamental principles that can serve us well – whether military or civilian – as we seek to establish firm ground on which to stand.

The first and most fundamental of these principles is that of ‘respect for persons’. This principle requires us to recognise the intrinsic dignity of every person – irrespective of their culture, gender, sex, religion, etc. As such, no person or group can be used merely as a means to some other end. Thus, the prohibition against slavery. No person or group can be deemed ‘less than fully human’ – even those who engage in unspeakably wicked deeds. The torturer or genocidal murderer might forfeit their lives under some systems of justice – but never their intrinsic dignity. That is why we insist on minimum standards of care for prisoners of war – and even war criminals awaiting their fate. Those who deny others intrinsic dignity open the gates to the hells of torture, genocide and the like.

The second principle is captured in an aphorism derived from the Canadian philosopher, Michael Ignatieff. Ignatieff argues that the difference between a ‘warrior’ and a ‘barbarian’ is ‘ethical restraint’. The idea is reflected in principles like those of ‘proportionality’ (minimum force required) and ‘discrimination’ (only legitimate targets) that are a core part of military ethics. However, I think that Ignatieff takes us somewhat deeper. His concept of ethical restraint – as the basis for distinguishing between ‘warriors’ and ‘barbarians’ – asks us not only to consider actions but also intent.

For example, to mount an attack of the kind launched by Hamas on October 7th – with the clear intention of massacring and mutilating innocent civilians – is to be distinguished from military action that tries, with utmost sincerity, to limit the harm caused to non-combatants. Hamas knows that Israel will always prevail in a direct contest of arms. However, following the logic of ‘asymmetric warfare’ it also knows that if it can goad Israel into fighting a ground war in areas heavily populated by civilians then the latter’s strategic strength can be broken in line with a loss of moral authority at home and abroad.

But how do you retain the status of a ‘warrior’ against an opponent who is deliberate in their use of the tactics of the ‘barbarian’ – and whose success absolutely depends on the wounding and death of the innocent?

This brings me to a third principle – familiar the world over. Expressed by the Chinese philosopher, Confucius, in the form, “Do not do to others what you would not have done to yourself”, the same principle (or a version of it) can be found in Jewish writings: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow-man. This is the entire Law, all the rest is commentary” (Talmud, Shabbat 3id – 16th Century BCE). The same sentiment can be found expressed in the Hadith – the sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad who is recorded as having said, “Not one of you truly believes until you wish for others that which you wish for yourself.” In a further formulation of the same basic principle, the Prophet is also recorded as having said, “Do unto all men as you would wish to have done unto you; and reject for others what you would reject for yourself.” Such precepts reflect the essence of the ‘Golden Rule’.

What then might be the implications for the current conflict if this widely recognised principle was given practical effect? Even the most savage Hamas terrorist, with an abiding hatred of the Jewish people, will refuse to countenance that a child of his be raped and murdered in pursuit of his cause. Nor would the most zealous defender of Israel allow the bombing of a Jewish hospital – even if a Hamas command centre is located beneath the structure. One hopes that both would refuse to do to others what they would not have done to their own. In short, the exercise of moral imagination (in which you stand in the others’ shoes) as required by the application of the Golden Rule, should produce just the kind of ethical restraint that Ignatieff calls for.

So, why the carnage?

One explanation lies in the violation of the first principle outlined above. Antisemitism of the kind written into the core ideology of Hamas is fueled by an ancient denial of the full and equal humanity of the Jewish people. It is the same denial that made the Holocaust possible – with Nazi propaganda deliberately dehumanising the Jews by comparing them to vermin. Extermination was the logical next step once the vicious premise had taken root. And that is why it chills one to the bone to hear the Israeli Defence Minister, Yoav Gallant, say that in the latest conflict, “We are fighting against human animals”. Israel is the one nation on earth where we might have hoped such words never to be uttered.

If one seeks moral clarity, it will not be found in a flag around which one can rally. It will not be found in ties of blood or history alone. It lies in the conscious application of principle – without fear or favour, beyond the ties of kinship.

This is not to say that one must set aside emotion. It is proper to grieve for family and friends and those closest to you in belief and culture. But sympathy, grief, anger and a lust for revenge are not the ground on which judgement must rest.

An edited version of this article was originally published in the Australian Financial Review.

Image: Justin Lane / AAP Photo

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

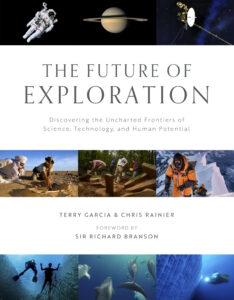

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 NOV 2023

For many years, I took it for granted that I knew how to see. As a youth, I had excellent eyesight and would have been flabbergasted by any suggestion that I was deficient in how I saw the world.

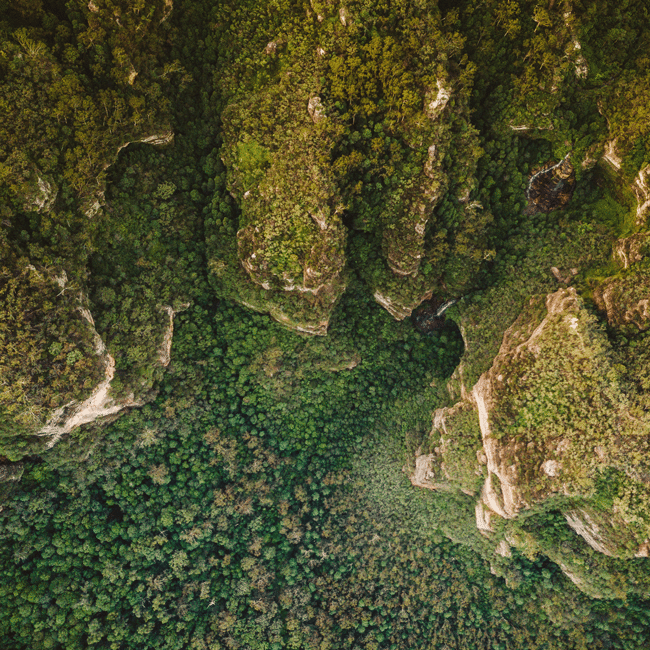

Yet, sometime after my seventeenth birthday, I was forced to accept that this was not true, when, at the end of the ship-loading wharf near the town of Alyangula on Groote Eylandt, I was given a powerful lesson on seeing the world. Set in the northwestern corner of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, Groote Eylandt is the home of the Anindilyakwa people. Made up of fourteen clans from the island and archipelago and connected to the mainland through songlines, these First Nations people had welcomed me into their community. They offered me care and kinship, connecting me not only to a particular totem, but to everything that exists, seen and unseen, in a world that is split between two moieties. The problem was that this was a world that I could not see with my balanda (or white person’s) eyes.

To correct the worst part of my vision, I was taken out to the end of the wharf to be taught how to see dolphins. The lesson began with a simple question: “Can you see the dolphins?” I could not. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t see anything other than the surface of the waves and the occasional fish darting in and out of the pylons below the wharf. “Ah,” said my friends, “the problem is that you’re looking for dolphins!” “Of course, I’m looking for dolphins,” I said. “You just told me to look for dolphins!” Then came the knockdown response. “But, bungie, you can’t see dolphins by looking for dolphins. That’s not how to see. What you see is the pattern made by a dolphin in the sea.”

That had been my mistake. I had been looking for something in isolation from its context. It’s common to see the book on the table, or the ship at sea, where each object is separate from the thing to which it is related in space and time. The Anindilyakwa mob were teaching me to see things as a whole. I needed to learn that there is a distinctive pattern made by the sea where there are no dolphins present, and another where they are. For me, at least, this is a completely different way of seeing the world and it has shaped everything that I have done in the years since.

This leads me to wonder about what else we might not see due to being habituated to a particular perspective on the world.

There are nine or so ethical lenses through which an explorer might view the world. Each explorer will have a dominant lens and can be certain that others they encounter will not necessarily see the world in the same way. Just as I was unable to see dolphins, explorers may not be able to see vital aspects of the world around them—especially those embedded in the cultures they encounter through their exploration.

Ethical blindness is a recipe for disaster at any time. It is especially dangerous when human exploration turns to worlds beyond our own. I would love to live long enough to see humans visiting other planets in our solar system. Yet, I question whether we have the ethical maturity to do this with the degree of care required. After all, we have a parlous record on our own planet. Our ethical blindness has led us to explore in a manner that has been indifferent to the legitimate rights and interests of Indigenous peoples, whose vast store of knowledge and experience has often either been ignored or exploited.

Western explorers have assumed that our individualistic outlook is the standard for judgment. Even when we seek to do what is right, we end up tripping over our own prejudice. We have often explored with a heavy footprint or with disregard for what iniquities might be made possible by our discoveries.

There is also the question of whether there are some places that we ought not explore. The fact that we can do something does not mean that it should be done. Inverting Kant’s famous maxim that “ought implies can,” we should understand that can does not imply ought! I remember debating this question with one of Australia’s most famous physicists, Sir Mark Oliphant. He had been one of those who had helped make possible the development of the atomic bomb. He defended the basic science that made this possible while simultaneously believing that nuclear weapons are an abomination. He put it to me that science should explore every nook and cranny of the universe, as we can only control what is known and understood. Yet, when I asked him about human cloning, Oliphant argued that our exploration should stop at the frontier. He could not explain the contradiction in his position. I am not sure anyone has yet clearly defined where the boundary should lie. However, this does not mean that there is no line to be drawn.

So how should the ethical landscape be mapped for (and by) explorers? For example, what of those working on the de-extinction of animals like the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger)? Apart from satisfying human curiosity and the lust to do what has not been done before, should we bring this creature back into a world that has already adapted to its disappearance? Is there still a home for it? Will developments in artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, and robotics bring us to a point where we need to redefine what it means to be human and expand our concept of personhood? What other questions should we anticipate and try to answer before we traverse undiscovered country?

This is not to argue that we should be overly timid and restrictive. Rather, it is to make the case for thinking deeply before striking out, for preparing our ethics with as much care as responsible explorers used to give to their equipment and stores.

The future of exploration can and should be ethical exploration, in which every decision is informed by a core set of values and principles. In this future, explorers can be reflective practitioners who examine life as much as they do the worlds they encounter. This kind of exploration will be fully human in its character and quality. Eyes open. Curious and courageous. Stepping beyond the pale. Humble in learning to see—to really see—what is otherwise obscured within the shadows of unthinking custom and practice.

This is an edited extract from The Future of Exploration: Discovering the Uncharted Frontiers of Science, Technology and Human Potential. Available to order now.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

We are the Voice

We are the voice! No monarch, no prime minister, no politician can decide how our democracy works. Only we, the people, voting as a whole, can resolve fundamental questions of how we will be governed – and by whom.

And so it has come to us to decide if and how to correct an historic injustice. First perpetrated by British colonists, through the doctrine of ‘terra nullius’ and then compounded by those who drafted the now repealed Section 127 of our nation’s most sacred political document, the Australian Constitution, our ‘original sin’ was to deny the prior existence of Indigenous peoples occupying, for millennia, the territories we now call Australia.

With mixed motivations – some virtuous and some vicious – the colonists sought to silence those whose lands they occupied. Guns, germs and steel – all did their work aided by policies of cultural suppression and assimilation. Yet, while sometimes just a whisper, at other times a mighty roar, the voices of our First Peoples have continued to echo across the lands and waters that make up our modern nation.

The descendants of our First Peoples have now asked us to repair the jagged rip in the fabric of our shared history. Their request is that this be done through the one means directly controlled by Australia’s citizens – an amendment to our Constitution. Their request is that this act of constitutional recognition be in the form of listening. They merely wish to be heard in relation to laws that directly affect their lives. That is all. No right of veto. No right to decide. Not even a right to determine how their voice is to be heard – for that is a matter reserved to Federal Parliament. Just a right to be recognised and heard as a distinct voice, amongst the many others, enshrined in our Constitution.

The debate about how to respond to this request has been intense – occasionally rancorous, confusing and ill-informed. So, here are some of the most important questions to have emerged during the course of debate:

Is the proposal to create the Voice racist?

No. The Voice is intended to recognise First Peoples based on their heritage not their race. As a whole, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders carry within their veins the blood of many races. Some of the staunchest opponents of the voice acknowledge this as a personal truth. The proposed constitutional recognition does not privilege race, it merely recognises people based on their descent from those who held original sovereignty over the lands and waters that, collectively, make up Australia.

Is it not just as wrong to recognise descent as it is race?

Not necessarily so. The Act that establishes the Australian Constitution already applies this principle in Section 2 which reads:

The provisions of this Act referring to the Queen shall extend to Her Majesty’s heirs and successors in the sovereignty of the United Kingdom.

It is the principle of ‘descent’ that made the late Queen Elizabeth our monarch – as it makes Charles our King – as will it make his son and his son rule over us for as long as we remain a constitutional monarchy.

Aren’t Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders divided on this question?

Yes. Some, like critics, such as those amongst the Blak Sovereign movement, demand much more. Others fear that adding a new voice to our Constitution will perpetuate division between the descendants of the First Peoples and those without those ancestral connections. Even so, it is estimated that around 80% of First Nations people support the proposal to recognise them in the Constitution through the establishment of an enshrined Voice to parliament and Government.

However, we should no more expect unanimity amongst our First Peoples than we do amongst any other group. Indigenous people are as divergent in their political opinions as is any other group of Australians.

Besides, if you read the minutes of the earliest constitutional conventions it soon becomes evident that virtually every clause in the current Constitution has been the subject of fierce debate and heated controversies. So, disagreement about potential clauses in our Constitution is nothing new. It is the ‘bread and butter’ of constitutional development and reform.

Is there any guarantee that a Voice will rapidly improve the lives of First Nations people?

A ‘yes’ vote will not immediately solve the problems of post-colonial poverty and disadvantage that blights the lives of so many descendants of our First Peoples. Nor will every grievance be reconciled. But things will be better than before. There will be reasons to hope that progress is possible. Also, it’s pretty clear that what we have been trying up until now has not been working.

What if we change our mind about the need for a Voice?

If at some time in the future the job of listening is done and reconciliation is practically complete, then we can always undo what I hope we will do, together, on October 14th. That’s the most important fact about our Constitution. Nothing is set in stone. Everything can be remade in whatever form the citizens of Australia prefer, from time to time. If something does not work, we can just change it.

Isn’t it undemocratic to confer rights on some citizens that are not enjoyed by others?

Yes, but that is already how our Constitution operates. Australian citizens living in the NT and ACT only have four Senators representing their interests (2 each). Tasmanians have 12 Senators – despite having a population smaller than that of the combined territories. We do not hear too many protests about the ‘undemocratic’ nature of this arrangement.

However, what exactly is the ‘right’ being accorded to First Peoples? And is it a right denied to any others citizen? In fact, the proposed amendment merely confers a right to make representations – and nothing more – which is the same right enjoyed by any Australian citizen whether making representations as an individual, as a member of community defined by ethnicity, faith, location, etc.

How can we vote on constitutional change without first having all of the details about how it will work?

The Australian Constitution contains little detail about how the powers of the Australian Parliament and Government are to be exercised. The Constitution merely lists, in general terms, the various ‘heads of power’ (e.g. see Section 52) – and then leave the rest to parliament and the government to decide the detail. Exactly the same approach is being taken with the proposed Voice. If ‘certainty’ was a precondition for voting in favour of the Constitution, as originally drafted and proposed, then it would never have been passed. Why do we require certainty in this matter alone?

I will be voting ‘yes’ in the referendum. I will do so because I want us to fill a gaping hole in our Constitution. Those who drafted the original document it did a pretty good job. But they left out a crucial ingredient – and we are all poorer for that mistake. The Australian Constitution brought into existence a new nation by preserving the Colonial States in a federation. Even New Zealand was included! But they left out the oldest parts of our nation – the multiple sovereign Indigenous states that existed prior to colonisation. No smaller than places like Monaco, Lichtenstein and San Moreno, our pre-colonial states had well-defined borders, enforceable laws, governance structures and so on.

Like a car without a boot or, a birthday cake without candles or, a paragraph without punctuation, our Constitution works well enough. But it is not complete. It is time that this error was corrected by according our First Peoples a modest but honoured place in our Constitution.

I sincerely believe that the creation of the Voice will benefit the whole nation – not just its First Peoples. It will be a bridge that connects the ancient voice of our country with the modern. It will enable crossings in both directions; making us, as a people, both distinctive and whole.

We are the voice. We need utter just one word to create a new reality… ‘yes’.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Barbie and what it means to be human

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 7 AUG 2023

It was with a measure of apprehension that I recently travelled to the cinema to watch Greta Gerwig’s Barbie.

I was conscious of being an atypical audience member – with most skewing younger, female and adorned in pink (I missed out on all three criteria). However, having read some reviews (both complimentary and critical) I was expecting a full-scale assault on the ‘patriarchy’ – to which, on appearances alone, I could be said to belong.

Warning: This article contains spoilers for the film Barbie

However, Gerwig’s film is far more interesting. Not only is it not a critique of patriarchy as a singular evil, but it raises deep questions about what it means to be human (whatever your sex or gender identity). And it does this all with its tongue firmly planted in the proverbial cheek; laughing not only at the usual stereotypes but, along the way, at itself.

The first indication that this film intends to subvert all stereotypes comes in the opening sequence – an homage to the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s iconic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rather than encountering a giant black ‘obelisk’ that reorients the history of humankind, a group of young girls wake to find a giant Margot Robbie looming over them in the form of ‘Stereotypical Barbie’. Until that time, the girls have been restricted to playing with baby dolls and learning the stereotypical roles allotted to women in a male-dominated world.

What happens next is instructive. Rather than simply putting aside the baby dolls in favour of the new adult form represented by Barbie, the girls embark on a savage work of destruction. They dismember the baby dolls, crush their skulls, grind them into the dirt. This is not a gentle awakening into something that is more ‘pure’ than what came before. From the outset, we are offered an image of humanity that is not one in which the divide between ‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘dominant’ and submissive’, ‘peaceful’ and ‘violent’ is neatly allocated in favour of one sex or another. Rather, virtues and vices are shown to be evenly distributed across humanity in all its variety.

That the violent behaviour of the little girls is not an aberration is made clear later in the film when we are introduced to ‘Weird Barbie’. She lives on the margins of ‘Barbieland’ – both an outcast and a healer – whose status has been defined by her broken (imperfect) condition. The damage done to ‘Weird Barbie’ is, again, due to mistreatment by a subset of girls who treat Barbie in the same way depicted in the opening scenes. Then there is ‘Barbieland’ itself – a place of apparent perfection … unless you happen to be a ‘Ken’. Here, the ‘Patriarchy’ has been replaced by a ‘Matriarchy’ that is invested with all of the flaws of its male counterpart.

In Barbieland, Kens have no status of their own. Rather, they are mere cyphers – decorative extensions of the Barbies whom they adorn. For the most part, they are frustrated by, but ultimately accepting of, their status. The conceit of the film is an obvious one: Barbieland is the mirror image of the ‘real world,’ where patriarchy reigns supreme. Indeed, the Barbies (in all their brilliant variety) believe that their exemplary society has changed the real world for the better, liberating women and girls from all male oppression.

Alas, the real world is not so obliging – as is soon discovered when the two worlds intersect. There, Stereotypical Barbie (suffering from a bad case of flat feet) and Stereotypical Ken are exposed to the radically imperfect society that is the product of male domination. Much of what they find should be familiar to us. The film does a brilliant job of lampooning what we might take for granted. Even the character of male-dominated big business comes in for a delightful serve. The target is Mattel (which must be commended for its willingness to allow itself to be exposed to ridicule – even in fictional form).

Unfortunately, Ken (played by Ryan Gosling) learns all the wrong lessons. Infected by the ideology of Patriarchy (which he associates with male dominance and horse riding) he returns to Barbieland to ‘liberate’ the Kens. The contagion spreads – reversing the natural order; turning the ‘Barbies’ into female versions of the Kens of old.

Fortunately, all is eventually made right when Margot Robbie’s character, with a mother and daughter in tow, returns to save the day.

But the reason the film struck such a chord with me, is because it raises deeper questions about what it means to be human.

It is Stereotypical Barbie who finally liberates Stereotypical Ken by leading him to realise that his own value exists independent of any relationship to her. Having done so, Barbie then decides to abandon the life of a doll to become fully human. However, before being granted this wish by her creator (in reality, a talented designer and businesswoman of somewhat questionable integrity) she is first made to experience what the choice to be human entails. This requires Barbie to live through the whole gamut of emotions – all that comes from the delirious wonder of human life – as well as its terrors, tragedies and abiding disappointments.

This is where the film becomes profound.

How many of us consciously embrace our humanity – and all of the implications of doing so? How many of us wonder about what it takes to become fully human? Gerwig implies that far fewer of us do so than we might hope.

Instead, too many of us live the life of the dolls – no matter what world we live in. We are content to exist within the confines of a box; to not think or feel too deeply, to not have our lives become more complicated as when happens when the rules and conventions – the morality – of the crowd is called into question by our own wondering.

Don’t be put off by the marketing puffery; with or without the pink, this is a film worth seeing. Don’t believe the gripes of ‘anti-woke’, conservative commentators. They attack a phantom of their own imagining. This film is aware without being prescriptive. It is fair. It is clever. It is subtle. It is funny. It never takes itself too seriously. It is everything that the parody of ‘woke’ is not.

It is ultimately an invitation to engage in serious reflection about whether or not to be fully human – with all that entails. It is an invitation that Barbie accepts – and so should we.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 3 JUL 2023

Nothing can or should diminish the good done by Gladys Berejiklian. And nothing can or should diminish the bad. One does not cancel the other. Both are true. Both should be acknowledged for what they are.

Yet, in the wake of Independent Commission Against Corruption’s finding that the former premier engaged in serious corrupt conduct, her political opponent, Premier Chris Minns, has refused to condemn the conduct that gave rise to this finding. Other politicians have gone further, putting personal and political allegiance ahead of sound principle to promote a narrative of denial and deflection.

Political corruption is like a highly contagious virus that infects the cells of the brain. It tends to target people who believe their superior virtue makes them immune to its effects. It protects itself from detection by convincing its hosts that they are in perfect ethical health, that the good they do outweighs the harm corruption causes, that noble intentions excuse dishonesty and that corruption only “counts” when it amounts to criminal conduct.

By any measure, Berejiklian was a good premier. Her achievements deserve to be celebrated. I am also certain that she is, at heart, a decent person who sincerely believes she always acted in the best interests of the people of NSW. By such means, corruption remains hidden – perhaps even from the infected person and those who surround them.

In painstaking legal and factual detail, those parts of the ICAC report dealing with Berejiklian reveal a person who sabotaged her own brilliant career, not least by refusing to avail herself of the protective measures built into the NSW Ministerial Code of Conduct. The code deals explicitly with conflicts of interest. In the case of a premier, it requires that a conflict be disclosed to other cabinet ministers so they can determine how best to manage the situation.

The code is designed to protect the public interest. However, it also offers protection to a conflicted minister. Yet, in violation of her duty and contrary to the public interest, Berejiklian chose not to declare her obvious conflict.

At the height of the COVID pandemic, did we excuse a person who, knowing themselves to be infected by the virus, continued to spread the disease because they were “a good person” doing ‘a good job’? Did we turn a blind eye to their disregard for public health standards just because they thought they knew better than anyone else? Did it matter that wilfully exposing others to risk was not a criminal offence? Of course not. They were denounced – not least by the leading politicians of the day.

But in the case of Berejiklian, what we hear in reply is the voice of corruption itself – the desire to excuse, to diminish, to deflect. Those who speak in its name may not even realise they do so. That is how insidious its influence tends to be. Its aim is to normalise deviance, to condition all whom it touches to think the indefensible is a mere trifle.

This is especially dangerous in a democracy. When our political leaders downplay conflicts of interest in the allocation of public resources, they reinforce the public perception that politicians cannot be trusted to use public power and resources solely in the public interest.

Our whole society, our economy, our future rest on the quality of our ethical infrastructure. It is this that builds and sustains trust. It is trust that allows society to be bold enough to take risks in the hope of a better future. We invest billions building physical and technical infrastructure. We invest relatively little in our ethical infrastructure. And so trust is allowed to decay. Nothing good can come of this.

When our ethical foundations are treated as an optional extra to be neglected and left to rot, then we are all the poorer for it.

What Gladys Berejiklian did is now in the past. What worries me is the uneven nature of the present response. Good people can make mistakes. Even the best of us can become the authors of bad deeds. But understanding the reality of human frailty justifies neither equivocation nor denial when the virus of corruption has infected the body politic.

This article was originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 7 JUN 2023

The unfolding PwC scandal could be considered nothing more than an especially egregious example of ethical failure with dire consequences.

However, there are deeper issues to be examined. The most obvious concerns the proper role of the Australian Public Service, and whether or not efforts by successive governments to hollow it out have caused damage that will take a generation to repair. Less obvious is the damage done to an essential component of Australia’s ethical infrastructure: the professions.

Australian governments have long been captivated by physical and technical infrastructure. Few politicians can resist the opportunity to don a hard hat and hi-vis vest when announcing new investment in road, rail, bridge and dam projects. There is equal pride in initiatives including the National Broadband Network, quantum computing and improved cybersecurity.

Unfortunately, there is little interest in the ethical “infrastructure” that determines the extent of public trust in major public- and private-sector institutions. Without that trust, reform becomes almost impossible – or only after untimely delays and great cost.

As with physical and technical infrastructure, the quality of a nation’s ethical infrastructure has tangible effects on a nation’s economy. For example, Deloitte Access Economics has estimated that just a 10% improvement in ethics, across Australia, would generate an extra A$45 billion in GDP each year.

What is ethical infrastructure?

There are many components to this ethical infrastructure. However, one of the most important is the professions – whose members influence nearly every aspect of our lives. To understand their distinctive role, one needs to recognise the difference between two “worlds”: those of the market on one hand, and the professions on the other.

The essential character of the market was defined by Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith. It is a place where self-interested actors satisfy the wants of others. Smith prohibits lying, cheating or the oppressive use of power – as all harm the free market. Self-interested conduct is mediated by the so-called invisible hand, which Smith argues leads to an increase in the stock of common good. Indeed, that is the test any market must pass: does it, in practice, make us all better off?

The second world – the professions – is, in two respects, the opposite of the market. First, members of the professions do not satisfy the wants of others; they are obliged to serve the interests of others. For example, a diabetic might want to consume a large block of chocolate. The market will happily satisfy this want as long as the customer can pay the tariff. However, a doctor will refuse to provide the chocolate because it is not in the interests of their patient to do so.

Second, professionals are obliged to put aside self-interest in favour of the public good. For example, as officers of the court, lawyers are obliged to help in the administration of justice. This takes precedence over duties to the client and to the profession. Only after all other interests have been served may a lawyer look to their self-interest. The same holds for the members of every true profession.

In recognition of this practice, society enters into a social compact with the professions. It accords status, and gives them access to certain work that others may not do. It establishes privileges (such as the shield laws that protect journalists’ sources). The quality of the social compact waxes and wanes over time – but can exist only for as long as the professions honour their commitment to reject the logic of the market.

The importance of independence

It is the ethical foundations of the professions – in particular the putting aside of self-interest – that makes it possible for Australian governments to outsource public-sector functions to large, professional consulting firms such as PwC. After all, governments have an inalienable duty to act solely in the public interest. It is inconceivable they would turn over any of their functions to a self-interested entity. That would be to invite the fox into the hen house.

Central to each of the “Big Four” consulting firms is their auditing practice. Compared with consulting, auditing is a minnow in terms of revenue and influence. However, there lies the core of accounting’s professional ethos with its commitment to what is true and fair.

Auditors should be the quintessential professionals – independent and divorced from the ethos of the market. So, when an auditing firm, like PwC, works for government, it is assumed they can be trusted. Until they cannot.

What impact will PwC’s behaviour have on other professions?

We do not know the full extent of what happened at PwC. However, it seems likely that, at some point, some part of the firm abandoned the world of the professions in favour of the market – placing self-interest before all other considerations.

Now we are left to wonder. Was this just a small part of PwC, or has the rot infected larger parts of the company? If the professional ethos of PwC has been corrupted, how is this risk being managed in other, similar organisations?

Most troubling of all, can society still rely on the social compact it has struck with the professions more generally? Or has this once-vital piece of ethical infrastructure fallen into disrepair?

Whether you care about the quality of our society, or the economy, or the possibility of progress, you should care about the quality of our nation’s ethical infrastructure. It’s time to reinforce what remains so it’s not all lost, through neglect, cynicism or indifference, and to our considerable cost.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships