Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 10 OCT 2015

In the flurry of emotion and analysis that followed the fatal shooting of police accountant Curtis Cheng in Parramatta by 15-year-old Farhad Jabar on 2 October 2015, one fact was more or less overlooked.

A child had been killed.

One of the tragedies of extremism is the way it can make us contemplate or perform acts that ordinarily are unthinkable. The police constable who shot and killed Jabar probably never imagined having to kill a child. And yet on that Friday afternoon, the unthinkable occurred.

Farhad Jabar didn’t seem like your typical kid. He shot a man in cold blood. It’s alleged he was reciting “Allahu Akbar” in the gunfight preceding his death, and a letter containing extremist rantings was reportedly found in his backpack.

We shouldn’t forget the fact of Jabar’s childhood. The police constable who killed him won’t – killing a child is arguably the ultimate moral line in the sand.

But Jabar was a child. At his death he was effectively a child soldier – having allegedly been radicalised by extremist groups in Sydney.

We know how groups abroad use child soldiers, but we’ve rarely been confronted by it directly. We don’t see child soldiers in Australia. The context in this case – extremism, the murder of police staff and allegations of terrorism – made us less sensitive to the fact Jabar was a child.

This insensitivity needn’t be the subject of public cultural haranguing but we shouldn’t forget the fact of Jabar’s childhood. The police constable who killed him won’t – killing a child is arguably the ultimate moral line in the sand.

Even the “American Sniper” Chris Kyle revolted at the idea of killing a child. Although the American Sniper film depicts Bradley Cooper’s Kyle taking the shot, the actual sniper never did so. In his book he writes, “I wasn’t going to kill a kid, innocent or not”.

Jabar was not innocent in any morally relevant sense. His actions meant he had forfeited his right not to be attacked – he had already killed one person and intended to kill several more.

The moral responsibility of the police officers was to neutralise the threat, and it’s reasonable to assume that no less harmful means were available. Killing may well have been the only option.

The constable was innocent of any wrongdoing. It was not the constable’s fault Jabar murdered a man in cold blood. Nor that there were no other means of neutralising him as a threat. In this sense, the constable was duty-bound to shoot Jabar.

But knowing that you’ve done your duty is likely to be cold comfort.

In my experience researching moral psychology among soldiers and veterans, I’ve learned that certain actions “stick” to the psyche more than others. The “stickiest” among them are acts that transgress deeply held moral and cultural norms.

These acts needn’t be crimes, either. Surviving when comrades did not, training accidents and collateral damage can all produce profound moral and psychological distress. In his book What it is Like to Go to War, veteran Karl Marlantes writes:

“Killing someone without splitting oneself from the feelings that the act engenders requires an effort of supreme consciousness that, quite frankly, is beyond most humans.”

How much worse is the killing of a child?

In similarly tragic cases, the military sphere has forms of counselling that aim to do one of two things. They might ignore the moral question altogether and treat this trauma as basic PTSD – Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – which it isn’t. Or they might explain the moral error in judgement – “you think you’ve done something wrong, but you actually haven’t”.

Neither would likely be helpful in a case like this.

Trauma related to the moral character of one’s actions isn’t PTSD in the standard sense. PTSD is about fear for one’s safety. This form of trauma, which I and others refer to as moral injury, is about guilt. Jonathan Shay, the psychiatrist who coined the term, calls this kind of trauma a “soul wound”.

“It’s not your fault” is well intended but – especially when repeated insistently – it can invalidate laudable moral emotions.

Pointing out the error in judgement will probably be equally ineffective. “It’s not your fault” is well intended but – especially when repeated insistently – it can invalidate laudable moral emotions. To feel remorse at having killed a child – even a child soldier like Jabar – is to accurately grasp the tragedy of what has transpired.

Australian philosopher Rai Gaita suggests cases like this reveal the problems with our concept of responsibility. He writes, it is “wrong to say that we should concern ourselves with what we did rather than with the fact that we did it”.

Gaita tells us remorse “is a kind of dying to the world”. We don’t yet know with certainty the best ways to address remorse in therapy, but a likely starting point is for us as a community to recognise the tragedy of what transpired in Parramatta.

A child was killed. And a good person was forced to kill him.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

COP26: The choice of our lives

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Chris Fotinopoulos The Ethics Centre 7 OCT 2015

Australia’s persistent anti-euthanasia stance is unfair, cruel and insensitive. It provides limited means to adults of sound mind to die on their own terms.

The current law on euthanasia restricts control and choice for certain terminally ill patients. It does so by denying them access to death-enabling drugs, information on how to administer them and appropriate medical support – including a physician’s assistance when needed.

The law compels certain individuals to die in ways they abhor and cannot easily escape. Meanwhile, others die peacefully and in control – often in their homes surrounded by loved ones and with appropriate medical assistance, albeit clandestine.

I’m always intrigued by the announcement of a prominent Australians death. The deceased invariably dies peacefully at home, with loved ones by their side. Why is it that the powerful and well connected often depart gently? Why are the less privileged compelled to endure irremediable suffering over a prolonged period?

Why it is that the powerful and well connected often depart gently? Why are the less privileged compelled to endure irremediable suffering over a prolonged period?

I’m reminded of a story a young man told me last year. He spoke movingly about how he lost his mother under tragic circumstances that could have been avoided if not for the state’s stance on voluntary euthanasia.

His mother was suffering from a serious long-term mental illness. Her desperate pleas to her doctors to help end a life that she described as “a living hell” were consistently dismissed as irrational. She was ultimately forced to die a violent death at her own hand.

According to her son, the life she foresaw was a life that she did not want. There was very little the medical profession could do to help her end it. His mother’s only option was suicide, which she took one lonely night at home after manically swallowing a cocktail of prescribed pills washed down with alcohol.

Her neighbour discovered her decaying corpse with a plastic bag over its head days after she died what must have been a horrible death.

This had a profound psychological impact on her son. He experienced depression, anxiety and complicated grief. The horror of his mother dying painfully and alone in such a setting is something that will stay with him to his grave.

A humane, just and civilised society should never insist on laws that allow such tragic deaths to continue. It should certainly not allow those rendered powerless through serious illness to suffer horrible deaths of this kind.

Society should do far more to empower the vulnerable through the provision of appropriate medical assistance, guidance and legal support. It should help them govern their life in a way that minimises suffering and delivers dignity in death.

Horrible deaths are not only restricted to the home. They also take place in hospitals and inpatient hospices. Years ago, I spoke with a senior oncologist at The Royal Melbourne Hospital. He spoke candidly about the problem in accessing life-ending medication for his patients.

He spoke of a seriously unwell middle-aged female patient who he regarded as a friend. She had no immediate family or close friends to help her finish her life well. She did not have a network of people who could help enact a plan that allowed her to die peacefully and with dignity in the comfort of her home. The only person who could help was her oncologist but he was legally unable to do what he understood would give her dignity in her death.

In this case both patient and doctor were locked under state control. They were denied choices available to those who have the good fortune, legal nous and medical support to implement their plans away from the state’s reach.

The contradictory and confused nature of our anti-euthanasia laws become apparent when viewed in light of the state’s stance on suicide. Suicide is not illegal. Australians are at liberty to take their own lives through a variety of different means, assuming they have the physical capacity to do so. Despite the grief suicide can cause to bereaved loved ones, it is nearly impossible – and arguably unethical – to prohibit.

A humane, just and civilised society should never insist on laws that allow such tragic deaths to continue.

If someone has the ability to end their life, they are free to do so. But those unable to end their life by their own hand are forced by the law to endure prolonged, unnecessary and irremediable suffering.

Anti-euthanasia advocates often argue palliative care is far more humane and caring than killing. They suggest more funding be directed to palliation rather than amending laws that allow the terminally ill to seek direct death. But those who take this line fail to acknowledge that some patients find death while under palliative sedation repugnant and unacceptable.

Denying a terminally ill person the option of choosing direct death over unwanted palliation is an infringement on their autonomy.

We need to appreciate that palliative care and physician-assisted death are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, terminally ill individuals who have high quality palliative care may be more open to the idea of assisted dying than those who do not.

Research conducted at Brunel University in London found terminal cancer patients in British hospices were more likely to consider doctor-assisted dying than those in hospitals. This contradicts the commonly-held view that assisted dying would decrease if options such as palliation and hospice care were readily available.

Voluntary euthanasia laws would not diminish the value of human life. They would enhance the prospect of a peaceful death by shifting control away from the state and other institutions. If individuals were granted control over this decision they would be empowered to achieve what they believe to be a good death.

If we are committed to delivering a good and peaceful death to all, then the law must extend personal autonomy, greater control and genuine informed choice to all Australians.

Nigel Baggar’s counter-argument is here.

In Australia, support is available at Lifeline 13 11 14, beyondblue 1300 224 636 and Kids Helpline 1800 551 800.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

BY Chris Fotinopoulos

Chris Fotinopoulos is an ethicist, writer and educator. He recently co-authored the Rationalist Society’s submission to the Victorian State Government Inquiry into End of Life Choices.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to respectfully disagree

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 2 OCT 2015

Why do we find it so hard to discuss difficult issues? We seem to have no trouble hurling opinions at each other. It is easy enough to form into irresistible blocks of righteous indignation. But discussion – why do we find it so hard?

What happened to the serious playfulness that used to allow us to pick apart an argument and respectfully disagree? When did life become ‘all or nothing’, a binary choice between ‘friend or foe’?

Perhaps this is what happens when our politics and our media come to believe they can only thrive on a diet of intense difference. Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Things that truly matter just overwhelm us with their significance. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Indeed, I think this must be it. Most of us have a deep-seated dislike of ambiguity. We easily submit to the siren call of fundamentalists in politics, religion, science, ethics … whatever. They sing to us of a blissful state within which they will decide what needs to be done and release us from every burden except obedience.

But there is a price to pay for certainty. We must pay with our capacity to engage with difference, to respect the integrity of the person who holds a principled position opposed to our own. It is a terrible price we pay.

The late, great cultural theorist and historian, Robert Hughes, ended his history of Australia, The Fatal Shore, with an observation we would do well to heed:

The need for absolute goodies and absolute baddies runs deep in us, but it drags history into propaganda and denies the humanity of the dead: their sins, their virtues, their failures. To preserve complexity, and not flatten it under the weight of anachronistic moralising, is part of the historian’s task.

And so it is for the living. The ‘flat man’ of history is quite unreal. The problem is too many of us behave as if we are surrounded by such creatures. They are the commodities of modern society, the stockpile to be allocated in the most efficient and economical manner.

Each of them has a price, because none of them is thought to be of intrinsic value. Their beliefs are labels, their deeds are brands. We do not see the person within. So, we pitch our labels against theirs – never really engaging at a level below the slogan.

It was not always so. It need not be so.

I have learned one of the least productive things one can do is seek to prove to another person they are wrong. Despite knowing this, it is a mistake I often make and always end up wishing I had not.

The moment you set out to prove the error of another person is the moment they stop listening to you. Instead, they put up their defences and begin arranging counter-arguments (or sometimes just block you out).

The moment you set out to prove the error of another person is the moment they stop listening to you.

Far better it is to make the attempt (and it must be a sincere attempt) to take the person and their views entirely seriously. You have to try to get into their shoes, to see the world through their eyes. In many cases people will be surprised by a genuine attempt to understand their perspective. In most cases they will be intrigued and sometimes delighted.

The aim is to follow the person and their arguments to a point where they will go no further in pursuit of their own beliefs. Usually, the moment presents itself when your interlocutor tells you there is a line, a boundary they will not cross. That is when the discussion begins.

At that point, it is reasonable to ask, “Why so far, but no further?” Presented as a case of legitimate interest (and not as a ‘gotcha’ moment) such a question unlocks the possibility of a genuinely illuminating discussion.

To follow this path requires mutual respect and recognition that people of goodwill can have serious disagreements without either of them being reduced to a ‘monstrous’ flat man of history. It probably does not help that so much social media is used to blaze emotion or to rant and bully under cover of anonymity. People now say and do things online that few would dare if standing face-to-face with another.

It probably does not help that we are becoming desensitised to the pain we cause the invisible victims of a cruel jibe or verbal assault. Nor does it help that the liberty of free speech is no longer understood to be matched by an implied duty of ethical restraint.

I am hoping the concept of respectful disagreement might make a comeback. I am hoping we might relearn the ability to discuss things that really matter – those hot, contentious issues that justifiably inflame passions and drive people to the barricades. I am hoping we can do so with a measure of goodwill. If there is to be a contest of ideas, then let it be based on discussion.

Then we might discover there are far more bad ideas than there are bad people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Steve Vanderheiden The Ethics Centre 30 SEP 2015

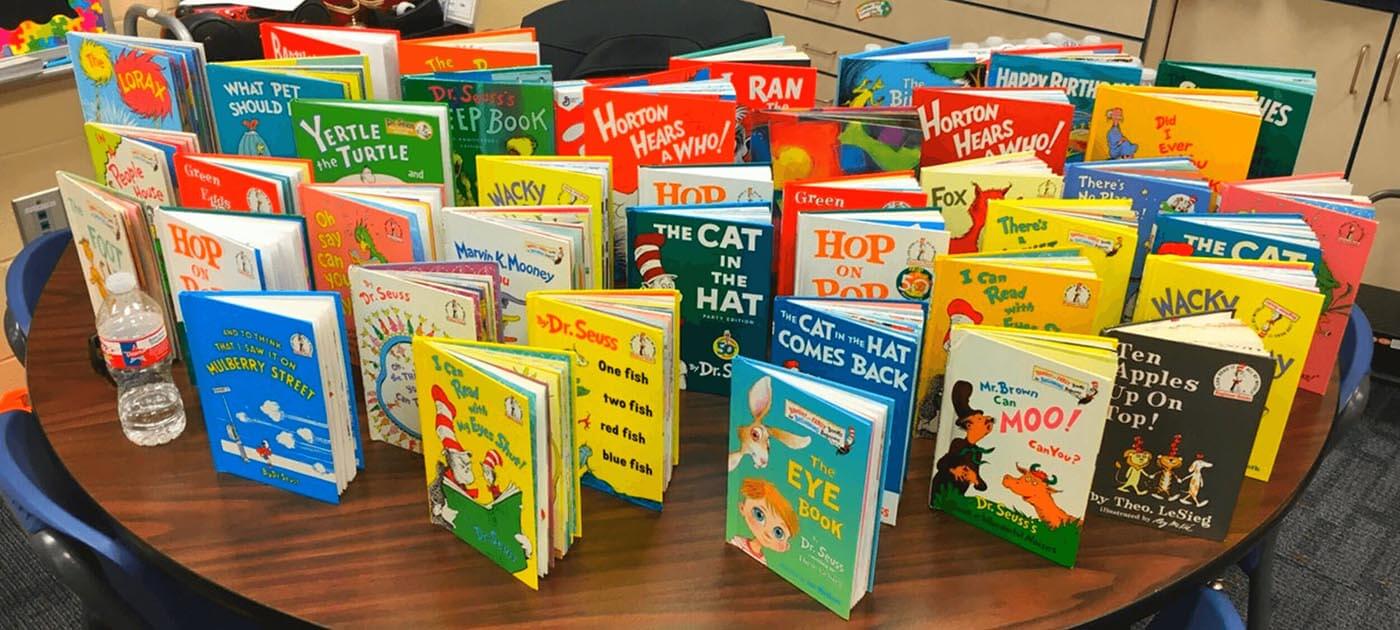

Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax explores the consequences of deforestation and the environmental costs of development. It concludes with the Once-ler, the narrator of the story who is principally responsible for deforestation of the decimated Truffula tree, entrusting its final seed to a young boy. He implores the child, “Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack. Then the Lorax and all of his friends might come back.”

The Once-ler, wracked by guilt for his complicity in this environmental disaster, passes along responsibility for reversing damage done by his generation to a child. The Lorax suggests the young take on duties of planetary stewardship where adults have failed.

Is this fair? Perhaps the generation responsible for mucking up the planet has lost its moral authority to try and save it. So the task of conservation is inherited by those with a longer-term stake in its future.

That adults might vest hope for a better planet in our children is both edifying and deeply troubling. Edifying because the environmental record of the world’s children bests that of adults by default. The young have not yet begun to reproduce the patterns of behavior that implicate their parents – resource depletion, biodiversity loss, climate change…

Troubling because they may reproduce them in future. We cannot realistically expect young people socialised into a world of willful environmental neglect to behave much differently than their parents have. Adults cannot so easily absolve themselves of the responsibility of addressing environmental harm they have caused.

Rather than saving the planet, a more modest objective might be to refrain from making it much worse for our children. Even this is a daunting prospect. Patterns of energy use dependent on fossil fuels all but guarantee that global temperatures will continue to rise. For most, climate change is no longer a debate about “if” but “how severe?”

We may still hope to make the planet better for our children in other ways. For instance, by adding to the richness of human culture and the stock of beneficial technologies. When it comes to climate though, a more appropriate aim might be to refrain from chopping that last Truffula tree. To preserve our remaining forests so our children might be able to see the proverbial Brown Bar-ba-loots, Swomee-Swans or Humming Fish in their native habitats rather than natural history museums.

Doing this will be challenging. It will require an often uncomfortable reflection on what drives global environmental degradation. In Seuss’ tale the insatiable demand for thneeds – the ultimate commodity – drives the Truffula deforestation. This implicates our heedless consumerism in the causal chain of degradation alongside the Once-ler.

When we consume things we don’t need, and when the industry around these commodities is obviously unsustainable despite our obliviousness to this fact, we contribute to resource depletion. What’s more, we add to the attitudes and norms that suggest this is a private matter, answerable only to private consumer preferences and not larger public concerns for equity or sustainability.

Worst of all, we teach our children to do the same.

The first step in reducing our negative impact upon the planet must be to understand how and where we make the impact we do. We need to understand alternatives that yield comparable value to us with a lighter toll upon the planet. Consuming more conscientiously will leave our children a better planet and make them better citizens of it. Though it requires us to consume differently and less.

Thinking about the long-term consequences of our choices will also help. We cannot plausibly claim to value our children’s future while discounting the future value of current investments in sustainable infrastructure or future costs of unsustainable current practices.

To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

Our deeds announce our concern for the welfare of future generations more accurately than our words or thoughts. Thinking about such choices must be accompanied by some changes in course. Citizens must demand better public choices be made rather than acquiescing to worse ones as unavoidable products of political inertia or inviolable market forces.

The tendency to shift problems across borders is no less insidious than passing them to our children or grandchildren. To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

As role models for our children our success in stopping environmental harm will matter less than our sincerity in the efforts we make. If we honestly try to maintain the planet, our example will help make them into the kind of people our planet needs.

For as the Once-ler interprets the Lorax’s cryptic final word, “UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

BY Steve Vanderheiden

Steve Vanderheiden is Associate Professor of Political Science and Environmental Studies at University of Colorado Boulder and Professorial Fellow with the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics (CAPPE) at Charles Sturt University.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Defining mental illness – what is normal anyway?

Defining mental illness – what is normal anyway?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anke Snoek The Ethics Centre 22 SEP 2015

The fact that mental illness remains poorly understood is not particularly surprising. Even the authoritative Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders struggles to reach a defensible definition – and it’s in its fifth edition!

Mental illness is often perceived as a chemical imbalance in the brain. This certainly accounts for an element of mental illness, but not all of it. We need to recognise that our definitions of illness are determined as much by our interpretations of those physical or mental changes as they are by the changes themselves.

We define illness based on whether a physical or mental change is incompatible – that is, maladaptive – with a person’s environment. Because our environments are both social and physical, our definitions entail value judgements of how an individual should behave.

The late Oliver Sacks described an island on which hereditary total colour blindness meant the majority of the population were born colour-blind. As such, communal practices reflect the needs of the majority – colour-blind people. The community is most active at dusk and dawn because the light at those times provides the best vision. Non-colour blindness is maladaptive on the island because social practices are designed around colour blindness.

This highlights the cultural influences involved in defining illness. In the case of mental illness, the normative element – what society sees as acceptable or unacceptable – is often more controversial and difficult to identify.

Each era tends to have a mental illness du jour, which seems to emerge as a product of social changes and the incompatibility of certain behaviours with those changes. One era’s shaman is another’s schizophrenic.

In the 1960s a movement called “anti-psychiatry” emerged under the influence of French philosopher Michel Foucault. The movement critiqued the assumptions underlying our concept of mental illness.

Anti-psychiatrist Thomas Szaz considers a person who believes he is Napoleon. To diagnose a disorder, the clinician would need to prove the patient is not Napoleon. Because Western society does not tend to embrace the idea of reincarnation, the man’s belief is maladaptive to his environment. But it would not be so everywhere. Societies with a firm faith in reincarnation, for instance, may not see the man’s beliefs as evidence of mental illness. John of God, a faith healer in Brazil, claims over 20 entities including King Solomon use his body as a healing vessel. Rather than being institutionalised, he is venerated.

In these cases social perception seems to be influencing our definitions of mental illness. Many will argue that the illnesses themselves still exist, but that cultural beliefs simply lead to a failure to diagnose. This may be true, but other cases are less clear. In some situations, culture itself may be the cause of mental illness.

Take the sculptress Camille Claudel. She decided to pursue a career in arts – an unusual decision in the 19th century. Claudel fell in love with the pre-eminent sculptor Auguste Rodin. She became his lover, and they started working together.

Claudel rose from his student to his equal, but Rodin’s reputation distracted from her own achievements. Over time, this led to feelings of exploitation, and paranoia. She was forcibly admitted to a mental institution, where she lived for 30 years.

In a letter, her brother explained to her, “genius doesn’t become women”. Was Claudel suffering a psychological illness, or reacting in the way we’d expect of someone continually overlooked and exploited?

The story of “hysteria” is a less tragic case. In the 19th century, European women began to challenge oppressive, patriarchal value systems. They became depressed, unruly, and threw tantrums. Sexual adventures and explorations were considered symptoms of hysteria.

Some believed hysteria to be a symptom of women’s maternal yearnings. Later, Sigmund Freud suggested hysteric women were sexually unfulfilled, so the prevailing treatment for hysteria became the massage of female genitals by doctors – physician-assisted masturbation.

Of course, we now know hysteria isn’t real. The diagnosis pathologised – made abnormal – women’s reasonable expectation for political freedom and sexual autonomy.

This highlights the fact that each era tends to have a mental illness du jour, which seems to emerge as a product of social changes and the incompatibility of certain behaviours with those changes. One era’s shaman is another’s schizophrenic.

Joan of Arc’s claims to hear the voice of God weren’t widely disputed. Today, we’d suspect she was in need of psychological intervention. Clare of Assisi lived an ascetic life to honour God. She spent the last 27 years of her life in bed, too weak to move. Today, she’d be treated for anorexia nervosa – instead, she was named as a saint.

What is our mental illness du jour? Dutch scientist and author Trudy Dehue describes a “depression epidemic”. She argues many cultures today fail to allow for the possibility people might not always be happy. Social norms make being happy a kind of imperative – “thou shalt be happy”.

The identification of new disorders and increasing diagnoses of previously uncommon ones can reveal social changes. For instance, less play-oriented modes of education may make ordinary childhood spontaneity seem deviant. Increasing rates of ADHD diagnosed among children might have less to do with behavioural problems in children and more to do with our expectations of both them and their attention spans.

That’s not to say mental illness isn’t real, but what we define as a mental illness doesn’t develop in a vacuum. The medical system has a great deal to offer the mentally unwell. We could further support them by acknowledging how our own assumptions of what constitutes ‘normal’ influences our attitudes toward mental illness.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Julian Savulescu The Ethics Centre 16 SEP 2015

In 2015, The National Health and Medical Research Council was accepting public submissions regarding sex selection in IVF procedures. It has previously prohibited non-medical sex selection.

This is one of two responses we’ve published on our website. Don’t agree with Julian? Check out Tamara Kayali Browne‘s piece, which argues that IVF sex selection is unethical.

Current NHMRC guidelines prohibit non-medical sex selection by any means. Victoria, Western Australia and South Australia have specifically legislated to ban sex selection using assisted reproduction.

The guidelines are now under review, providing the Australian public, the NHMRC and professionals an opportunity to re-examine their opposition to sex selection.

Opposition to the legalisation of non-medical sex selection illustrates a misunderstanding of the role of law in civil society. If A wants to do X, and B wants to assist A to do X for a price, the sole ground for interfering in their freedom is they will harm someone. Moral disapproval is not a ground for a legal ban.

Who would be harmed by allowing sex selection?

The most obvious candidate is the child. Call him John. The basis of most legislation in assisted reproduction is that the best interests of the child must be paramount. However, it is not against the interests of John to be conceived by sex selection. Indeed, if IVF and sex selection were not performed, John would not exist. John owes his very existence to the act of sex selection.

There is another kind of harm often invoked in these kinds of debates – a moral harm. John is being used as a means to his parents’ ends of having a child whom they have stereotyped goals for. John is being used as an instrument.

People intuitively believe that children should be “gifts”, not valued for particular characteristics, such as sex, intelligence or athletic ability. We ought to give them their own opportunity to make their own life. That is, they should have a right to an open future.

Enter Immanuel Kant

Such objections are best expressed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who said people should always be treated as an end, and never a means.

But what Kant actually said is never treat people merely or solely as a means. We treat people as a means all the time – shopkeepers, salesmen, repair people and doctors. We respect adults by obtaining their consent to treat them as a means.

It is not possible to obtain consent from children – particularly not regarding their creation. What then does it mean to treat a child merely as a means?

People have children for all sorts of reasons – to be a sibling, to hold a marriage together, to care for parents, to be a companion, to realise the parent’s dreams, to take over the family business or to be king of England. Ethically, these reasons aren’t important. What matters is how well they treat their child once it is born, whether male, female, disabled, tall, short, come what may.

Something like this kind of “instrumentalisation” objection might be behind the NHMRC’s policy:

A conditional life

The Australian Health Ethics Committee believes that admission to life should not be conditional upon a child being a particular sex.

Equality of all people should not be conditional upon any characteristic, such as their sex. But there is a distinction between continued existence and coming into existence. Continued existence should not be conditional on sex.

It might be thought the same follows for admission to life. But the NHMRC does allow medically motivated sex selection to guard against certain diseases and disabilities. This suggests admission to existence can be “conditional” upon being healthy and non-disabled.

What “conditional” means here is “based on reasons”. One can have children for reasons, such as being of certain sex, having certain abilities, being healthy or not disabled. As long as one loves the child, gives the child an open future and good life, having reasons to have that child is perfectly ethically acceptable.

For example, a father wants to have a son to take to football matches. He therefore moulds the child to his needs by sex selecting. He can still treat the child, once born, as an end by respecting the child’s own decision to pursue an interest in music instead.

Harmful sexist stereotypes

The final alleged harm is to society, either by reinforcing sexist stereotypes or disturbing the sex ratio. In some parts of India and China, there are six males to five females.

Such harms could be real and might be a legitimate basis for interfering in liberty. But another basic principle is that the least liberty-restricting (least coercive) means should be adopted to prevent harm.

The present ban on non-medical sex selection is very wide-ranging and coercive. Are there less coercive means that would allow some sex selection but not reinforce sexist stereotypes and disturb the sex ratio? There are at least three better policies:

- Sex selection only in favour of girls.

- Sex selection for family balancing. That is, sex selection for the second or third child, when the existing children are all of one sex and the preference is for the opposite sex. In Australia, this is the most common reason for sex selection and a little more than 50 percent select girls.

- Incidental sex selection. A couple having IVF and genetic diagnosis for infertility and screening of disorders, could be allowed to express a preference over the healthy embryos, at the discretion of their doctors.

Each of these strategies is less liberty-restricting and would protect the public interest.

There are no good grounds for the blanket ban on sex selection. Sex selection does not harm the child and any collateral harm (due to discrimination) can be controlled in better ways. A blanket ban is unethical, excessively restricting procreative liberty.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Stopping domestic violence means rethinking masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

BY Julian Savulescu

Julian Savulescu holds the Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics and is Director of the Centre for Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford. He also directs the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics and the Institute for Science and Ethics. He is Editor of the Journal of Medical Ethics.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How we should treat refugees

How we should treat refugees

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 10 SEP 2015

It may seem harsh to question the heartfelt public response to the image of toddler Aylan Kurdi lying dead on a Turkish beach. However, the motivating force of compassion can easily be reduced to futile gestures, unless it is spliced onto a set of actionable principles that will endure beyond the first wave of sympathy.

Then prime minister Tony Abbott’s 2015 announcement that Australia would permanently resettle an additional 12,000 Syrian refugees was a significant response to the mass exodus of asylum seekers. But we should assess the quality of Australia’s offer against a solid foundation of principles.

In this case, those principles are the institution of sanctuary or, in its modern guise, asylum. Using this approach, I would suggest that asylum is fundamentally about the public and personal good of human safety. As such:

- Those who meet the objective condition of fleeing from persecution and oppression, whether arising in conditions of peace or war, are entitled to seek asylum. Their claims for asylum may never be deemed as ‘unlawful’ or ‘illegal’. To apply these labels to such people is wrong and involves a profound misunderstanding of the law.

- The ways in which people seek asylum may, in some circumstances, be illegal. However, that does not make the asylum seekers themselves ‘illegal’. This focus on legality is a relatively new concern. At the height of the Cold War, the representatives of the liberal democracies weren’t heard to condemn defectors and asylum seekers for breaching borders as they escaped from behind the Iron Curtain. But, moving on…

- Those who have the capacity to offer asylum are obliged to do so when a bona fide request is made. Asylum is an offer of safety (not a promise of prosperity). Nearly everything hangs on the obligation to keep an asylum seeker safe. This is central to the criticism of the conditions under which the Australian government holds people arriving irregularly by boat. To subject an asylum seeker to indefinite detention in conditions like those on Manus Island and Nauru clearly fails this minimal test. The evidence of mental illness and physical abuse suffered by those held in such places makes this clear.

- Not everyone claiming asylum is a bona fide refugee. Some people making such a claim may merely be seeking a more prosperous future. There is no duty to offer asylum to such people. However, given our inability (at least on the high seas) to distinguish between those who are entitled to asylum and those who are not, we should give all the benefit of the doubt. To accept an illegitimate claimant is a lesser evil than it would be to deny asylum to a person with a legitimate claim.

- Finally, the compassionate urge to avoid preventable deaths among those seeking asylum (for example, at sea) is a worthy one and should not be mocked nor denied. That said, the means employed to achieve this end should be consistent with the other principles outlined above.

What effect might these principles have if applied to the tsunami of refugees seeking sanctuary in Europe? Our starting point must be the distinctive nature of the cause of the great displacement.

Abbott labelled Daesh (ISIS) a ‘death cult’ and compared it to the Nazis. Australian Defence Force personnel were posted in Iraq at the request of the Iraqi government to degrade and destroy this pernicious power. We know Daesh was not constrained by established international borders and their actions in one place (Iraq) generated effects not just there but also in the murderous conflict in Syria. So, under any reasonable test, those fleeing from this conflict were refugees and their claims for asylum were lawful and legitimate.

Moreover, as a country that was directly involved in the conflict in Iraq and Syria, Australia could be said to have a particular obligation to these refugees, as their plight was an unintended consequence of our conduct. Given this, a marginal response would be inadequate.

The mayhem was indifferent to the religion, ethnicity, nationality, age or gender of its victims. And so should we be. Any attempt to define a ‘preferred cohort’ of refugees who might receive the benefit of Australian sanctuary would have to be specifically justified – and I doubt that could be done without inviting criticism that our aid is sectarian or self-serving.

We should ensure that the refugees’ passage to Australia is safe. Instead of stopping the boats we might, perhaps, send them.

In an ideal world, Australia would already have developed a comprehensive regional solution based, in part, on mutual interests, shared ethical obligations and a willingness to do our fair share of the ‘heavy lifting’. We might then have led an effort to bring many more people from Europe to the relative safety of our region.

Given our obligation to offer asylum to those whose objective circumstances give rise to a legitimate claim, and given the vast size of the problem we’re involved with, Australia should be generous in its offer of refuge – if only by adopting special measures to increase our humanitarian intake well beyond the current cap. That is the general principle against which the number ‘12,000’ needs to be evaluated.

Finally, we should ensure that the refugees’ passage to Australia is safe. Instead of stopping the boats we might, perhaps, send them.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Flaky arguments for shark culling lack bite

Flaky arguments for shark culling lack bite

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + Environment

BY Clive Phillips The Ethics Centre 10 SEP 2015

Culling sharks is unnecessarily harmful, disproportionate and will do little to protect humans.

The question of whether we should protect humans by culling sharks is not new. There are many parallels to the problems posed by land-based apex predators such as lions and tigers. The solutions we have adopted on land – including widespread culling – are unlikely to be either ethical or effective in dealing with shark attacks.

We must consider whether sharks offer humans indirect benefits. For example, sharks help control the seal population, which eats the fish we rely on for food and trade. Last winter, fishermen called for seal culls in South Australia because of the healthy fur seal population there.

People enjoy observing sharks in the ocean either directly through “shark tourism” or on TV. Discovery Channel’s “Shark Week” has become a cultural phenomenon in many nations. Apex predators hold a certain fascination – we marvel at their control of their territory. The awe we feel when viewing sharks is itself an indirect, unquantifiable benefit.

Even if these indirect benefits did not outweigh the risks to swimmers and surfers, this alone would not justify culling. We would have to consider whether the harms involved in controlling sharks are greater than the harms shark attacks cause to humans.

The numbers of sharks we would need to control for effective protection far exceeds the number of humans who benefit from controlling shark populations. Less aggressive forms of land-based controls for apex predators – for example, excluding lions from agricultural areas – are unlikely to work in the marine environment.

The numbers of sharks we would need to control for effective protection far exceeds the number of humans who benefit from controlling shark populations.

The practical outcome of this means many more sharks are killed than humans. In Queensland alone, about 700 sharks die per year in the culling program. By comparison, only one human has been killed – in an unbaited region.

In addition, baiting – a key tactic in the culling process – generates unintended harms such as “bycatching”. Baiting works on more than just sharks. It also lures turtles, whales and dolphins, which pose no threat to anyone. They are collateral damage in the war against sharks.

Netting beaches has been presented as a viable alternative to culling but here too there is risk of bycatch. Furthermore, netting leaves sharks to suffer and die slowly, giving rise to another raft of ethical concerns.

If culling is to be justifiable we need to consider the steps being taken to minimise shark suffering. Sharks captured on baited hooks suffer extensively, even when patrols detect and shoot injured sharks.

Let us suppose we could eventually devise ways of effectively stopping sharks entering the littoral zone by culling them in a way that minimised suffering. We would still have to consider the desirability of interfering in this way.

The long-term ethical consequences of destroying or reducing the population of an apex predator are considerable. The absence of apex predators in Australia has allowed an enormous kangaroo population to thrive. This population has had to be culled due to the competition they pose to domestic herbivores.

What’s more, the huge population means kangaroos face widespread starvation during droughts. The existence of apex predators may be bad for those caught in their path, but it is good for the entire ecosystem.

Human culling works contrary to the ‘natural’ culling apex predators perform. While predators prey on the weak and elderly, human culling targets the fittest or those with others dependent on them. As such it challenges the continuity of the entire species.

Many will argue that sharks have a right to occupy the territory in which they have evolved over millions of years, and this trumps the alleged right of humans to use territory they are ill-suited to and gain little significant benefit from. Certainly, many surfers respect these rights – acknowledging sharks as fellows in the ocean rather than threats or enemies.

The shark cull may in fact be exacerbating the shark problem in a cruel and ironic circle.

The sharks’ rights are enshrined in our law. Great Whites are an endangered species and therefore enjoy legal protection. Given the legal status sharks enjoy, the benefits to humans would have to be especially high to justify culling as an ethical option.

Surfers can adopt another sport if they are unwilling to assume the risk of shark attacks – and many are. This is particularly true if they are unwilling to explore cheaper, more reasonable ways of protecting themselves.

The shark cull may in fact be exacerbating the shark problem in a cruel and ironic circle. Sharks may be driven to attack humans because of the damage we have done to their environment. Shark experts argue that injured sharks on baited hooks attract other sharks to the area.

The elimination of apex predators such as Great Whites destroys millions of years of evolutionary adaptation. The ethical risks and costs of controlling the environment in this way are rarely contemplated in the face of tragic but rare fatal attacks. Instead of balanced reflection, we see knee-jerk responses that fail to adequately address the broad range of ethical issues.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

BY Clive Phillips

Clive Phillips is Chair of Animal Welfare and Director of the Centre for Animal Welfare Ethics at the University of Queensland.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Sophie Lamond The Ethics Centre 2 JUN 2015

There are 795 million hungry people on Earth. The world produces more food than its human population needs. Between the farm, the processing plant, the retailer and the home, the world discards one-third of all food intended for human consumption.

In Australia, we throw out the equivalent of one in every five bags of groceries we take home. Tens of thousands of us rely on charitable food relief.

Apart from consumers wasting money, producing food that goes to waste accounts for a massive loss of resources, such as energy, water and human labour. After disposal, food rotting in landfill releases potent greenhouse gases.

What did the French do?

At the end of the day, ‘dumpster divers’ scavenge food from supermarket bins. It happens all over the world. In France, supermarket owners were concerned dumpster divers might get sick from eating contaminated food and sue. So supermarkets started pouring bleach in their dumpsters to ward off the divers.

Parisian councillor Arash Derambarsh thought this was “scandalous and absurd”. He proposed large supermarkets donate all their excess stock to food rescue agencies.

Why won’t the French system work in Australia?

France’s law sounds great but there are some translation problems when applying it to the Australian context. France is rushing to regulate because they are several steps behind Australia when it comes to dealing with food waste.

All the major supermarkets in Australia have partnerships with food rescue agencies like Ozharvest, Secondbite, Fareshare and Foodbank as part of their corporate social responsibility strategies. These organisations redistribute surplus supermarket food to charities that feed those in need. Unlike their French counterparts and French supermarkets, Australian food rescue agencies are protected by Good Samaritan Laws, which afford them certain safeguards against litigation.

A spokesperson for the Australian Food and Grocery Council (AFGC) said, “There is enormous goodwill and partnership between industry and agencies to ensure that charities receive food products that are needed – not just what is left over.

“Any proposed legislative intervention will need to guard against any unintended outcome where food companies may be forced to send charities excess stock that is not required. This could place greater burden on charities which are currently subject to dumping charges.”

Elaine Montegriffo, CEO of food rescue agency Secondbite said, “If supermarkets are doing it of their own free will, rather than as a matter of compliance, it is far more likely to work out for the charity”.

Imagine a large shipment of mislabelled muesli bars arrives at a supermarket and can’t be sold. If Australia were to implement a similar law to France, the supermarket can choose to pass on the bars for animal feed or compost, or give them to a food rescue agency. But if the agency has already reached its logistical limit for transport and storage and can’t find a charity to take the bars, it still has to pay for that transport, storage and most likely the disposal of the bars.

Montegriffo would rather serious policy than a mandate on supermarkets. “I would like food waste and food security to sit in somebody’s portfolio,” she said.

The Australian way isn’t perfect

The Australian system might be ahead of France’s but it still has a long way to go. To see the full picture of food waste in the Australian supply chain we need to pull our head out of the back-of-store dumpsters. We need to encourage suppliers, processors and retailers to increase supply chain efficiencies.

Supermarkets often use the visual merchandising tactic of purposefully over-ordering to maintain an aesthetic of abundance. Shelves that look full are more appealing to shoppers, even though supermarkets can dump contracts with farmers on a whim.

With Coles and Woolworths accounting for a 70% share of the market, Australia has one of the most highly concentrated retail grocery sectors in the world. This is problematic for a number of reasons. These practices can lead to massive and unnecessary waste. The emotional, economic and environmental costs of binning the excess produce lies with farmers, not supermarkets.

Where to from here?

While 90 percent of Australia’s food charities report that they do not have enough food to meet the demand for their services, relying on waste to feed the hungry is not a sustainable solution. Our ultimate goal should be to eliminate food waste and food want.

We don’t need to follow France’s new regulatory measures, but we can learn a few things from their consumer education. In addition to its new laws for big supermarkets, France will soon roll out education programs on food waste for schools and businesses. Australia should take note. We can learn to eat in-season produce, no matter how it looks when it grows. Those wonky cucumbers and two legged carrots are just fine. We can shop smarter and buy the right amount of food, and we can re-learn kitchen skills so food and leftovers are used rather than thrown away.

Last week, Environment Minister Greg Hunt announced a multi-partisan dialogue to develop a National Food Waste 2025 Strategy. France’s consumer education is a good start, but let’s hope Hunt’s strategy addresses the full complexity of the problem. This includes improved monitoring of food waste, investment in infrastructure to process it outside landfill, competition laws to help diversify the grocery sector, support of alternative food distribution networks, and fairer relationships between farmers and supermarkets.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Testimonial Injustice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we need land tax, explained by Monopoly

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What it means to love your country

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Marcus Costello The Ethics Centre 27 MAY 2015

There are more references to lighthouses, beacons and buoys in Australia’s Constitution than there are to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. As it stands, our First Peoples aren’t mentioned at all.

Most Australians and the two major political parties agree this must change – but opinion is divided on how such changes should take form.

The then prime minister Tony Abbott had wanted a referendum on Indigenous Constitutional recognition to take place on 27 May 2017 – the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum to include Aborigines in the census and amend racially discriminatory sections of the Constitution. But the 2017 referendum didn’t happen.

What needs amending?

Constitutional law professor George Williams has said, “The 1967 referendum deleted discriminatory references specific to Aboriginal people, but put nothing in their place. Torres Strait Islanders have never been referred to in the constitution. As a result, rather than recognising Indigenous people, the referendum left a silence at the heart of the Constitution”.

While race discrimination specifically against Indigenous people has been deleted, “Australia is now the only democratic nation in the world that has a constitution with clauses that still authorise discrimination on the basis of race”, says Williams.

There are two sections of the Constitution that mention race. The first, section 25, says that the states can ban people from voting based on their race. The second, section 51(26), gives federal parliament power to pass laws that discriminate against people based on their race.

Professor Melissa Castan says, “section 51(26), the so-called “races power”, has been interpreted by the High Court to allow the federal parliament to make laws that discriminate adversely on the basis of race.” She points out, “Parliament only ever used the races power regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

Some are concerned that a Constitutional amendment which states Indigenous people are the original custodians of the land will make non-Indigenous people feel like imposters in the place they call home.

Some concerns from Constitutional conservatives

Some Australians are concerned that a Constitutional amendment which states Indigenous people are the original custodians of the land will make non-Indigenous people feel like imposters in the place they call home.

This concern is an echo of the reluctance to embrace a national apology to Australia’s stolen generations in 2008.

Speaking at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard soon after the apology, former Liberal PM John Howard said, “I do not believe, as a matter of principle, that one generation can accept responsibility for the acts of an earlier generation.”

The apology, however, did not trigger the onset of mass guilt in the non-Indigenous Australian population. It was overwhelmingly celebrated.

Howard went on to say his view was shared by Noel Pearson of the Cape York Indigenous Council, a man whom he regarded as “the voice of contemporary Indigenous Australia”.

Pearson remains an authority for many conservatives. In an effort to temper the concerns of constitutional conservatives, in 2015 Pearson put forward a three-part proposal to minimise Constitutional change:

- Remove racially discriminatory wording in the Constitution

- Devise a Declaration of Recognition to stand alongside the Constitution

- Assemble a parliamentary advisory body to comment on laws affecting Indigenous people

Vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University, Greg Craven, described Pearson’s proposal as “genuinely brilliant”.

The apology did not trigger the onset of mass guilt in the non-Indigenous Australian population. It was overwhelmingly celebrated.

“The greatest danger would be inserting vague, manipulable language into the Constitution,” Craven argued. “There are no references to ‘sovereignty’ or sweeping guarantees of equality and far-flung rights.”

Craven claims Pearson’s proposal will allay constitutional conservatives’ fears that recognition of Indigenous Australians will promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as in some way superior to other races.

“Indigenous identity, indigeneity, is not superior to the identity of other Australians, nor does it in any way threaten that national identity”, Craven wrote. “It simply is the case that an identity based upon millennia of profound connection with this country, physical and spiritual, is sufficiently special to be worthy of safe, certain recognition.”

What are some of the proposals by Indigenous leaders?

The then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Mick Gooda, was reluctant to accept a Declaration that sat outside of the Constitution, so was not a legal document. “It is the law out of which all other law in this country comes from and to be recognised in [the Constitution] is probably the ultimate form of recognition,” he said.

Geoff Clark, former chairman of the disbanded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, had proposed Australia, “include a simple clause in the body of the Constitution that the consent of the Aboriginal people is required for the application [of] laws and policies that may have an effect on Aboriginal people.”

Such a clause would have had the power to stop a government initiative like the Northern Territory Intervention, which has been criticised for lack of consultation with Indigenous communities. On the other hand, Craven says, Pearson’s body of Indigenous representatives, would “advise, suggest and comment. Its views would be debatable, disputable and disposable.”

RECOGNISE was an Indigenous advocacy group governed by the board of Reconciliation Australia, which from 2012 to 2017 ran a campaign “to see fairness and respect at the heart of our Constitution, and to ensure racial discrimination has no place in it. Our goal is a more united nation.”

Based on the recommendations by an Expert Panel in 2012, RECOGNISE proposed Constitutional amendments that included a provision for government to: “pass laws for the benefit of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”.

However, for many Indigenous people, the goal is not constitutional reform, it is sovereignty and a treaty. As mentioned in this Expert Panel report a survey conducted by the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples in July 2011 revealed: “88 per cent of Congress members identified constitutional recognition and sovereignty as a top priority. Unfortunately, it was apparent from consultations and submissions that sovereignty means different things to different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.”

The Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples was established in November 2012 to interpret the findings from the Expert Panel.

What might voting ‘No’ look like?

Senator Cory Bernardi remains opposed to a Constitution that makes special reference to racial groups. “Anything that seeks to divide our country by race, and every proposal that I’ve heard of seeks to do exactly that, I think is doomed to fail … I would be absolutely campaigning for the ‘No’ vote,” Bernardi told AM.

If stamping out racism is what Bernardi was aiming for, that is honourable. But the way he conjures a post-racial society seems to frame race as a distinctly negative quality. Wilful ‘colour blindness’ to what makes us different denies what makes us special. From wherever on earth we descend, we should hope to draw on our racial heritage as a source of pride, and find a comforting sense of community in our culture.

A position statement from The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists states: “The lack of acknowledgement of a people’s existence in a country’s constitution has a major impact on their sense of identity and value within the community, and perpetuates discrimination and prejudice which further erodes the hope of Indigenous people.” The College concluded, “Recognition in the constitution … is an important step to support and improve the lives and mental health of Indigenous Australians.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights