Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Social contract theories see the relationship of power between state and citizen as a consensual exchange. It is legitimate only if given freely to the state by its citizens and explains why the state has duties to its citizens and vice versa.

Although the idea of a social contract goes as far back as Epicurus and Socrates, it gained popularity during The Enlightenment thanks to Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Today the most popular example of social contract theory comes from John Rawls.

The social contract begins with the idea of a state of nature – the way human beings would exist in the world if they weren’t part of a society. Philosopher Thomas Hobbes believed that because people are fundamentally selfish, life in the state of nature would be “nasty, brutish and short”. The powerful would impose their will on the weak and nobody could feel certain their natural rights to life and freedom would be respected.

Hobbes believed no person in the state of nature was so strong they could be free from fear of another person and no person was so weak they could not present a threat. Because of this, he suggested it would make sense for everyone to submit to a common set of rules and surrender some of their rights to create an all-powerful state that could guarantee and protect every person’s right. Hobbes called it the ‘Leviathan’.

It’s called a contract because it involves an exchange of services. Citizens surrender some of their personal power and liberty. In return the state provides security and the guarantee that civil liberty will be protected.

Crucially, social contract theorists insist the entire legitimacy of a government is based in the reciprocal social contract. They are legitimate because they are the only ones the people willingly hand power to. Locke called this popular sovereignty.

Unlike Hobbes, Locke thought the focus on consent and individual rights meant if a group of people didn’t agree with significant decisions of a ruling government then they should be allowed to join together to form a different social contract and create a different government.

Not every social contract theorist agrees on this point. Philosophers have different ideas on whether the social contract is real, or if it’s a fictional way to describe the relationship between citizens and their government.

If the social contract is a real contract – just like your employment contract – people could be free not to accept the terms. If a person didn’t agree they should give some of their income to the state they should be able to decline to pay tax and as a result, opt out of state-funded hospitals, education, and all the rest.

Like other contracts, withdrawing comes with penalties – so citizens who decide to stop paying taxes may still be subject to punishment.

Other problems arise when the social contract is looked at through a feminist perspective. Historically, social contract theories, like the ones proposed by Hobbes and Locke, say that (legitimate) state authority comes from the consent of free and equal citizens.

Philosophers like Carole Pateman challenge this idea by noting that it fails to deal with the foundation of male domination that these theories rest on.

For Pateman the myth of autonomous, free and equal individual citizens is just that: a myth. It obscures the reality of the systemic subordination of women and others.

In Pateman’s words the social contract is first and foremost a ‘sexual contract’ that keeps women in a subordinate role. The structural subordination of women that props up the classic social contract theory is inherently unjust.

The inherent injustice of social contract theory is further highlighted by those critics that believe individual citizens are forced to opt in to the social contract. Instead of being given a choice, they are just lumped together in a political system which they, as individuals, have little chance to control.

Of course, the idea of individuals choosing not to opt in or out is pretty impractical – imagine trying to stop someone from using roads or footpaths because they didn’t pay tax.

To address the inherent inequity in some forms of social contract theory, John Rawls proposes a hypothetical social contract based on fundamental principles of justice. The principles are designed to provide a clear rationale to guide people in choosing to willingly agree to surrender some individual freedoms in exchange for having some rights protected. Rawls’ answer to this question is a thought experiment he calls the veil of ignorance.

By imagining we are behind a veil of ignorance with no knowledge of our own personal circumstances, we can better judge what is fair for all. If we do so with a principle in place that would strive for liberty for all at no one else’s expense, along with a principle of difference (the difference principle) that guarantees equal opportunity for all, as a society we would have a more just foundation for individuals to agree to a contract that in which some liberties would be willingly foregone.

Out of Rawls’ focus on fairness within social contract theory comes more feminist approaches, like that of Jean Hampton. In addition to criticising Hobbes’ theory, Hampton offers another feminist perspective that focuses on extending the effects of the social contract to interpersonal relationships.

In established states, it can be easy to forget the social contract involves the provision of protection in exchange for us surrendering some freedoms. People can grow accustomed to having their rights protected and forget about the liberty they are required to surrender in exchange.

Whether you think the contract is real or just a useful metaphor, social contract theory offers many unique insights into the way citizens interact with government and each other.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A note on Anti-Semitism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why hard conversations matter

Why hard conversations matter

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 31 AUG 2016

There are times in the history of a nation when its character is tested and defined. Too often it happens with war, natural disasters or economic collapse. Then the shouting gets our attention.

But there are also our quieter moments – the ones that reveal solid truths about who we are and what we stand for.

How should we recognise Indigenous Australians? Can our economy be repaired in a manner that is even-handed? How will we choose if forced to decide between China and the United States? How do we create safe ways for people seeking asylum? Can we grow our economy and protect our people and environments? These are just some of the questions we face.

Too often, I see conversations shut down before they have even begun. People with a contrary point of view are faced with outrage, shouted down or silenced by others driven by the certainty of righteous indignation.

And here’s another question. Do we have the capacity to talk about these things without tearing ourselves and each other apart?

There are some safe places for open conversation about difficult questions. Thirty years ago I began work at a not-for-profit, The Ethics Centre dedicated to creating them. The Festival of Dangerous Ideas now enters its 11th year with a new digital format to cater to our current times, bringing leading thinkers from around the world together to discuss important issues.

Sadly, there is a growing fragility across Australian society. The demand for ideological purity (you’re completely ‘with us’ or ‘against us’) puts us at risk of a fractured and stuffy world of absolutes.

Too often, I see conversations shut down before they have even begun. People with a contrary point of view are faced with outrage, shouted down or silenced by others driven by the certainty of righteous indignation. In such a world, there is no nuance, no seeking to understand the grey areas or subtleties of argument.

Attempts to prove to people that they are wrong just leads to stalemate. Barricades go up and each side lobs verbal grenades. There is another way.

This phenomenon crosses the political spectrum – embracing conservatives and progressives alike. In my opinion, it is the product of a self-fulfilling fear that our society’s ethical skin is too thin to survive the prick of controversy and debate. This is a poisonous belief that drains the life from a liberal democracy.

Fortunately, the antidote is easily at hand. In essence we need to spend less time trying to change other people’s minds and more time trying to understand their point of view. We do that by taking them entirely seriously.

Why make this change? Because attempts to prove to people that they are wrong just leads to stalemate. Barricades go up and each side lobs verbal grenades. There is another way. We could allow people to work out what the boundaries are for their own beliefs.

Working out the lines we cannot cross is often the first step towards others, but it can only happen when people feel safe. Giving people the space to fall on just the right side of such lines can make a world of difference.

So I wonder, might we pause for a moment, climb down from our battle stations and call a ceasefire in the wars of ideas? Might we recognise the person on the other side of an issue may not be unprincipled? Perhaps they’re just differently principled.

Can we see in the face of our ideological opponent another person of goodwill? What then might we discover about each other; what unites and, yes, what divides? What then might we understand about the issues that will define us as a people?

Let’s rediscover the art of difficult discussions in which success is measured in the combination of passion and respect. Let’s banish the bullies – even those who claim to be well-intentioned. They, alone, have no place in the conversations we now need to have.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

The closest English word for the Ancient Greek term eudaimonia is probably “flourishing”.

The philosopher Aristotle used it as a broad concept to describe the highest good humans could strive toward – or a life ‘well lived’.

Though scholars translated eudaimonia as ‘happiness’ for many years, there are clear differences. For Aristotle, eudaimonia was achieved through living virtuously – or what you might describe as being good. This doesn’t guarantee ‘happiness’ in the modern sense of the word. In fact, it might mean doing something that makes us unhappy, like telling an upsetting truth to a friend.

Virtue is moral excellence. In practice, it is to allow something to act in harmony with its purpose. As an example, let’s take a virtuous carpenter. In their trade, virtue would be excellences in artistic eye, steady hand, patience, creativity, and so on.

The eudaimon [yu-day-mon] carpenter is one who possesses and practices the virtues of his trade.

By extension, the eudaimon life is one dedicated to developing the excellences of being human. For Aristotle, this meant practicing virtues like courage, wisdom, good humour, moderation, kindness, and more.

Today, when we think about a flourishing person, virtue doesn’t always spring to mind. Instead, we think about someone who is relatively successful, healthy, and with access to a range of the good things in life. We tend to think flourishing equals good qualities plus good fortune.

This isn’t far from what Aristotle himself thought. Although he did believe the virtuous life was the eudaimon life, he argued our ability to practice the virtues was dependent on other things falling in our favour.

For instance, Aristotle thought philosophical contemplation was an intellectual virtue – but to have the time necessary for contemplation you would need to be wealthy. Wealth (as we all know) is not always a product of virtue.

Some of Aristotle’s conclusions seem distasteful by today’s standards. He believed ugliness was a hindrance to developing practical social virtues like friendship (because nobody would be friends with an ugly person).

However, there is something intuitive in the observation that the same person, transformed into the embodiment of social standards of beauty, would – everything else being equal – have more opportunities available to them.

In recognising our ability to practice virtue might be somewhat outside our control, Aristotle acknowledges our flourishing is vulnerable to misfortune. The things that happen to us can not only hurt us temporarily, but they can put us in a condition where our flourishing – the highest possible good we can achieve – is irrevocably damaged.

For ethics, this is important for three reasons.

First, because when we’re thinking about the consequences of an action we should take into account their impact on the flourishing of others. Second, it suggests we should do our best to eliminate as many barriers to flourishing as we possibly can. And thirdly, it reminds us that living virtuously needs to be its own reward. It is no guarantee of success, happiness or flourishing – but it is still a central part of what gives our lives meaning.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

From capitalism to communism, explained

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Hannah Dahlen The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2016

Just try mentioning ‘birth plans’ at a party and see what happens. Hannah Dahlen – a midwife’s perspective

Mia Freedman once wrote about a woman who asked what her plan was for her placenta. Freedman felt birth plans were “most useful when you set them on fire and use them to toast marshmallows”. She labelled people who make these plans as “birthzillas” more interested in birth than having a baby.

In response, Tara Moss argued:

The majority of Australian women choose to birth in hospital and all hospitals do not have the same protocols. It is easy to imagine they would, but they don’t, not from state to state and not even from hospital to hospital in the same city. Even individual health practitioners in the same facility sometimes do not follow the same protocols.

The debate

Why the controversy over a woman and her partner writing down what they would like to have done or not done during their birth? The debate seems not to be about the birth plan itself, but the issue of women taking control and ownership of their births and what happens to their bodies.

Some oppose birth plans on the basis that all experts should be trusted to have the best interests of both mother and baby in mind at all times. Others trust the mother as the person most concerned for her baby and believe women have the right to determine what happens to their bodies during this intimate, individual, and significant life event.

As a midwife of some 26 years, I wish we didn’t need birth plans. I wish our maternity system provided women with continuity of care so by the time a woman gave birth her care provider would fully know and support her well-informed wishes. Unfortunately, most women do not have access to continuity of care. They deal with shift changes, colliding philosophical frameworks, busy maternity units, and varying levels of skill and commitment from staff.

There are so many examples of interventions that are routine in maternity care but lack evidence they are necessary or are outright harmful. These include immediate clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord at birth, episiotomy, continuous electronic foetal monitoring, labouring or giving birth laying down and unnecessary caesareans. Other deeply personal choices such as the use of immersion in water for labour and birth or having a natural birth of the placenta are often not presented as options, or are refused when requested.

The birth plan is a chance to raise and discuss your wishes with your healthcare provider. It provides insight into areas of further conversation before labour begins.

I once had a woman make three birth plans when she found out her baby was in a breech presentation at 36 weeks. One for a vaginal breech birth, one for a cesarean, and one for a normal birth if the baby turned. The baby turned and the first two plans were ditched. But she had been through each scenario and carved out what was important for her.

Bashi Hazard – a legal perspective

Birth plans were introduced in the 1980s by childbirth educators to help women shape their preferences in labour and to communicate with their care providers. Women say preparing birth plans increases their knowledge and ability to make informed choices, empowers them, and promotes their sense of safety during childbirth. Some (including in Australia) report that their carefully laid plans are dismissed, overlooked, or ignored.

There appears to be some confusion about the legal status or standing of birth plans. Neither is reflective of international human rights principles or domestic law. The right to informed consent is a fundamental principle of medical ethics and human rights law and is particularly relevant to the provision of medical treatment. In addition, our common law starts from the premise that every human body is inviolate and cannot be subject to medical treatment without autonomous, informed consent.

Pregnant women are no exception to this human rights principle nor to the common law.

If you start from this legal and human rights premise, the authoritative status of a birth plan is very clear. It is the closest expression of informed consent that a woman can offer her caregiver prior to commencing labour. This is not to say she cannot change her mind but it is the premise from which treatment during labour or birth should begin.

Once you accept that a woman has the right to stipulate the terms of her treatment, the focus turns to any hostility and pushback from care providers to the preferences a woman has the right to assert in relation to her care.

Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this.

Care providers who understand the significance of the human and legal right to informed consent begin discussing a woman’s options in labour and birth with her as early as the first antenatal visit. These discussions are used to advise, inform, and obtain an understanding of the woman’s preferences in the event of various contingencies. They build the trust needed to allow the care provider to safely and respectfully support the woman through pregnancy and childbirth. Such discussions are the cornerstone of woman-centred maternity healthcare.

Human Rights in Childbirth

Reports received by Human Rights in Childbirth indicate that care provider pushback and hostility towards birth plans occurs most in facilities with fragmented care or where policies are elevated over women’s individual needs. Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this. If anything, greater planning would facilitate smoother outcomes in the event of unanticipated eventualities.

In truth, it is not the case that these care providers don’t have a birth plan. There is a birth plan – one driven purely by care providers and hospital protocols without discussion with the woman. This offends the legal and human rights of the woman concerned and has been identified as a systemic form of abuse and disrespect in childbirth, and as a subset of violence against women.

It is essential that women discuss and develop a birth plan with their care providers from the very first appointment. This is a precious opportunity to ascertain your care provider’s commitment to recognising and supporting your individual and diverse needs.

Gauge your care provider’s attitude to your questions as well as their responses. Expect to repeat those discussions until you are confident that your preferences will be supported. Be wary of care providers who are dismissive, vague or non-responsive. Most importantly, switch care providers if you have any concerns. The law is on your side. Use it.

Making a birth plan – some practical tips

- Talk it through with your lead care provider. They can discuss your plans and make sure you understand the implications of your choices.

- Make sure your support network know your plan so they can communicate your wishes.

- Attending antenatal classes will help you feel more informed. You’ll discover what is available and the evidence is behind your different options.

- Talk to other women about what has worked well for them, but remember your needs might be different.

- Remember you can change your mind at any point in the labour and birth. What you say is final, regardless of what the plan says.

- Try not to be adversarial in your language – you want people working with you, not against you. End the plan with something like “Thank you so much for helping make our birth special”.

- Stick to the important stuff.

Some tips on the specific content of your birth plan are available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

BY Hannah Dahlen

Hannah Dahlen is a professor of Midwifery at Western Sydney University and a practising midwife.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

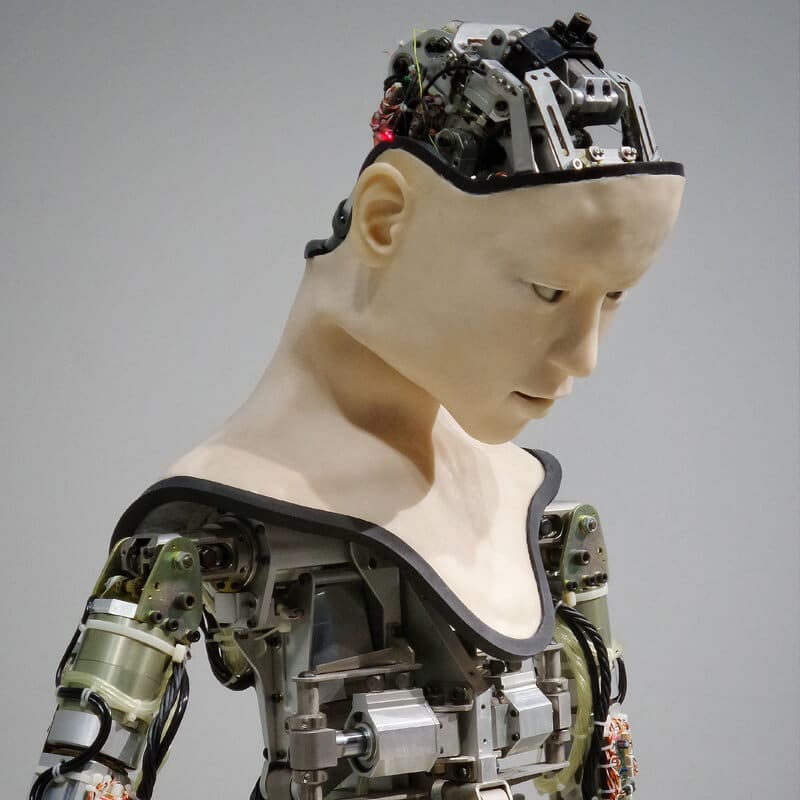

The “good enough” ethical setting for self-driving cars

The “good enough” ethical setting for self-driving cars

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Ryan Jenkins The Ethics Centre 19 JUL 2016

Plenty of electronic ink has been spilled over the benefits self-driving cars offer. We have good reason to believe they could greatly reduce the number of fatalities from car accidents – studies suggest upwards of 90 percent of road accidents are caused by driver error.

Avoiding a crash altogether is clearly the best option, but even in crash scenarios some believe autonomous cars might be preferable. Facing a “no win” situation, a driverless car may have the opportunity to “optimise” the crash by minimising harm to those involved. However, choices about how to direct or distribute harm in these cases (for example, hit that person instead of the other) are ethically fraught and demand extraordinary scrutiny of a number of distinctly philosophical issues.

Can we be punished for inaction?

It would be unfair to expect car manufacturers to program their products to ‘crash ethically’ when the outcomes might get them in legal trouble. The law typically errs on the side of not directly committing harm. This means there might be difficulties in developing algorithms that simply minimise harm.

Given this, the law might condemn an autonomous car that steered away from five people and into one person in order to minimise the harm resulting from an accident. A judge might argue that the car steered into someone and so it did harm. The alternative, merely running over five people, results in more harm, but at least the car did not aim at any one of them.

But is inaction in this case morally justified if it leads to more harm? Philosophers have long disputed this distinction between doing harm and merely allowing harm to occur. It is the basis for perhaps the most famous philosophical thought experiment – the trolley problem.

Some philosophers argue that we can still be held responsible for inaction because not doing something still involves making a decision. For example, a doctor may kill her patient by withholding treatment, or a diplomat may offend a foreign dignitary by not shaking her hand. If algorithms that minimise harm are problematic because of a legal preference for inaction over the active causing of harm, there might be reason to ask the law to change.

Should we always try to minimise harm?

Even if we were to assume autonomous cars should minimise the total amount of harm that comes about from an accident, there are complex issues to resolve. Should cars try to minimise the total number of people harmed? Or minimise the kinds of harms that come about?

For example, if a car must choose between hitting one person head-on (a high risk accident) and steering off the road, endangering several others to a less serious injury, which is preferable? Moral philosophers will disagree about which of these options is better.

Another complication arises when we consider that harm minimisation might require an autonomous car to allow its own passengers to be injured or even killed in cases where inaction wouldn’t have brought them to harm. Few consumers would buy a car they expected to behave this way, even if they would prefer everyone else’s car did.

Are people breaking the law more deserving of harm?

Minimising overall harm might in some cases lead to consequences many would find absurd. Imagine a driver who decided to play ‘chicken’ with an autonomous car – driving on the wrong side of the road and threatening to plough head-long into it. Should the passengers in the autonomous car be put at risk to try to avoid a crash that is only occurring because the other driving is breaking the law?

Perhaps self-driving cars need something like ‘legality-adjusted aggregate harm minimisation’ algorithms. Given the widely-held beliefs that people breaking the law are liable to greater harm, deserve a greater share of any harm and that it would be unjust to require law-abiding citizens to share in the harm equally, self-driving cars will need to reflect these values if they are to be commercially viable.

But this approach also faces problems. Engineers would need a reliable way to predict crash trajectories in a way that provided information about the severity of harms, which they aren’t yet able to do. Philosophers would also need a reliable way to assign weighted values to harms, for example, by assigning values to minor versus major injuries. And as a society we would need to determine how liable to harm someone becomes by breaking the law. For example, someone exceeding the speed limit by a small amount may not be as liable to harm as someone playing ‘chicken’.

None of these issues are easy and seeking sure-fire answers every stakeholder agrees to is likely impossible. Instead, perhaps we should seek overlapping consensus – narrowing down the domain of possible algorithms to those that are technically feasible, morally justified and legally defensible. Every proposal for autonomous car ethics is likely to generate some counterintuitive verdicts but ongoing engagement between various parties should continue in the hopes of finding a set of all-around acceptable algorithms.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

How will we teach the robots to behave themselves?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

BY Ryan Jenkins

Dr Ryan Jenkins studies the moral dimensions of technologies with the potential to profoundly impact human life. He is an assistant professor of philosophy and a Senior Fellow at the Ethics & Emerging Sciences Group at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo. His interests include the ethics of transformative technologies such as driverless cars, robots, algorithms, and autonomous weapons. He is concerned with how these technologies intersect with duties of justice, how they stand to restructure our activities, and how they enable or encumber meaningful human lives.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY James Connor The Ethics Centre 19 JUL 2016

We exist via our social interactions with others. Without these connections embedding us in the social world we have no identity, existence or meaning. These ongoing interactions, made easier through habit and accepted norms, define us.

Central among these habits and norms is the idea of loyalty. Our loyalties provide a guide to what we might expect in an otherwise uncertain world. It is about our expectations of future action – my loyalty is based on the feeling that you will return it in future.

Being loyal is not obligatory, but when you breach someone’s loyalty you lose part of yourself. That’s the inescapable cost of disloyalty, whether minor – a friendship lost – or extreme – the firing squad for treason. That is the challenge with loyalty – there is always a chance to be disloyal. If that opportunity didn’t exist, loyalty wouldn’t make sense at all.

Nobody deserves our unconditional loyalty. However, they do deserve a shared sense of reciprocity based on past actions and hopes for the future. If people are loyal to us, they expect we will return that loyalty at some point in the future. And this is where the problem begins.

It can be hard to imagine a self without certain relationships and so we tend to hold to them more strongly.

The future is unknowable. Our loyalty may be called on in a variety of circumstances, from the mundane to the deeply difficult. A brother asks you to lie – how far are you willing to go to maintain that familial loyalty? What has he done to require you to lie? Is it the socially lubricating ‘white lie’ – “please tell Mum I wasn’t late”, or the far more serious – “please tell the police we were together all evening”.

What’s crucial here is an assessment of the act that generated the need to lie – what is the social expectation regarding the behaviour – is it acceptable? Is it the sort of behaviour other people would overlook in favour of loyalty?

We tend to over-invest in those loyalties that are key to our social milieu. It can be hard to imagine a self without certain relationships and so we tend to hold to them more strongly. Loyalty to family, friends, sports team, social activity – without them we lose parts of our self.

Because these relationships form part of who we are, there is a cost to disloyalty, even when it is the right thing to do. The experience of whistleblowers reveals the loss of identity that can come from breaching loyalty. While whistleblowing is often the ethical choice, the individuals tend to be shunned, excluded, exposed, attacked and betrayed.

If our country provides the basics of existence, security of self, food, shelter and the conditions to live a just life, then don’t we owe a debt of loyalty?

Loyalty can be vexing when it is demanded rather than given freely. Nation-states demand loyalty from their citizens to the point of self-sacrifice, especially in times of war. We also see a demand for loyalty attached to ideologies and beliefs. For example, the McCarthyism in the US in the 1950s saw an aggressive enforcement of compulsory ideological loyalty to one political system over another. Do we as citizens have an obligation to be loyal to our country of birth?

If our country provides the basics of existence, security of self, food, shelter and the conditions to live a just life, then don’t we owe a debt of loyalty? No, we don’t. Loyalty to abstractions shouldn’t be demanded. In fact I think we should avoid such commitments because they ask us to sacrifice real loyalties to people – family, friends and community.

The nation doesn’t care for you or me as an individual, that’s the job of our interpersonal connections. It’s also what makes them more important to us. However, a defender of nationalism might point to the threat a conqueror poses to the individual and family. They might argue that you have an obligation to be conscripted to defend your nation as a way to protect the people you are loyal to, but this is different to being loyal to the state itself.

Our loyalties foster connection, provide us with a map of social obligations and help alleviate the threat of an unknowable future. But to call upon them is fraught with risk – we might be betrayed, exploited or the future may change in ways we don’t anticipate. But if there were no risk, there would be little value to being loyal at all, would there?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

BY James Connor

Dr James Connor is an academic in the School of Business at UNSW Canberra and author of The Sociology of Loyalty.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Learning risk management from Harambe

Learning risk management from Harambe

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gav Schneider The Ethics Centre 2 JUN 2016

Traditional and social media channels were flooded with the story of Harambe, a 17-year-old western lowland silverback gorilla shot dead at Cincinnati Zoo on 28 May 2016 after a four-year-old boy crawled through a barrier and fell into his enclosure.

With the benefit of hindsight, forming an opinion is easy. There are already plenty being thrown around regarding the incident and who was to blame for the tragedy.

The need to kill Harambe is exceptionally depressing: a gorilla lost his life, the zoo lost a real asset, a mother was at risk of losing her child, and staff tasked by the zoo to shoot Harambe faced emotional trauma based on the bond they likely formed with him.

In technical risk management terms, the zoo seems to have been in line with best practice.

Overall, it was a bad state of affairs. Though the case gives rise to a number of ethical issues, one way to consider it is as a risk management issue – where it presents us with some important lessons that might prevent similar circumstances from happening in the future, and ensure they are better managed if they do.

In technical risk management terms, the zoo seems to have been in line with best practice.

According to Cincinnati Zoo’s annual report, 1.5 million visitors visited the park in 2014 to 2015. Included in those numbers are hundreds of parents who visited the zoo with children who didn’t end up in any of the animal enclosures.

According to WLWT-TV, this was the first breach at the zoo since its opening in 1978. There is no doubt the zoo identified this risk and managed it with secure (until now) enclosures. There is also little doubt relevant signage and duty of care reminders would have been placed around the zoo. Staff would assume parents would manage their children and keep them safe. In the eyes of most risk management experts, this would seem to be more than sufficient.

Organisations need to put energy and effort into so called ‘black swan’ events… that are unlikely but have immense consequences if they do occur.

However, as we have seen in several cases (including Cecil the Lion) it does not seem to be the incident itself that brings the massive negative consequences but rather social media, based on the fact that the internet provides a platform for everyone to be judge and jury.

This flags the massive shift required in the way we manage risk. If we look only at the financial losses to the zoo, their decision may seem logical and rational. They were truly put in a no-win position – an immediate tactical decision was required once Harambe began dragging the child around the water.

Imagine if they had decided to tranquillise Harambe and the four-year-old boy had died while they were waiting for the tranquillisers to take effect – what would the impact have been?

The true lesson regarding this issue lies in the need for organisations to put energy and effort into so-called ‘black swan’ events – ones that are unlikely but have immense consequences if they do occur. These events are often overlooked, based only on the fact they are unlikely, leaving organisations unprepared for when they do.

The ethics of what is right and wrong tend to blur when the masses have a platform to pass judgement.

Traditional risk management approaches try to allocate scores to things and then put associated resources to the highest ranking risk issues. In this case, a risk that was deemed managed actually occurred and the result was very negative.

Whether negligent or not, various social media commentators have held the mother accountable. It seems she has been held to account based not on what she did, but for the apparently unapologetic and callous way she responded to the killing of Harambe.

This shows us risk management needs to consider the human element in a way we previously haven’t. The ethics of what is right and wrong tend to blur when the masses have a platform to pass judgement. There are many lessons to be taken from this incident, including the following considerations:

- Risk management and duty of care should be incorporated in a more cohesive manner, focusing on applying a BDA approach (Before, During and After).

- Social media backlash adds a new dimension to the way organisations should make, report and defend their decisions.

- Individuals can no longer purely blame the organisation they believe responsible based on negligence or breach of duty of care. Even if the individual shifts blame onto the organisation entirely, and they are not held to account by the law, they will be held to account by the general public.

- We have entered an era where system- and process-based risk management needs to integrate human and emotive elements to account for emotional responses.

- Lastly – and unrelatedly – the question of why one story attracts massive public outcry and why another doesn’t raises ethical questions regarding the way we consume news, the way the media reports it, and the upsides and downsides of social media.

In short this is another case of how much work we still have to do – especially in the modern internet age – to proactively and ethically manage risk.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The personal vs the political: Resistance in One Battle After Another

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

(Roe)ing backwards: A seismic shift in women’s rights

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

BY Gav Schneider

Dr Gav Schneider is the CEO of the Risk 2 Solution Group and Head of the Australian Catholic Universities Postgraduate Program in The Psychology of Risk.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why it was wrong to kill Harambe

Why it was wrong to kill Harambe

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + Environment

BY Clive Phillips The Ethics Centre 2 JUN 2016

The killing of Harambe the gorilla at Cincinnati Zoo this week has aroused public sentiment in a way reminiscent of the public outrage caused by the killing of Cecil the lion.

This was not an isolated incident. On at least two previous occasions small children have accidentally fallen into gorilla pens. On both occasions the children were ‘protected’ by a prominent gorilla in the group, one female and one male, incidents which were heralded as examples of cross species animal altruism.

The incidents occurred in 1986 and 1991 in Jersey Zoo and Brookfield Zoo respectively – when rapid response teams would have been unknown. They demonstrate that gorillas are not dangerous animals.

This is further supported by the fact some witnesses’ reports said that Harambe was actually protecting the child and had not demonstrated any malevolence.

Animal behaviour expert, Professor Gisella Kaplan of the University of New England, has confirmed that gorillas are not inherently aggressive and would likely have not wanted to harm the child – a result of their social lifestyle and herbivorous diet.

Nowadays zoos have Dangerous Animal Response Teams, which in the ten minutes since the boy entered the enclosure made the decision to euthanise the gorilla. Members of this team are typically trained by the police to react to a dangerous animal threatening a member of the public.

Zoo animals already sacrifice many rights for the sake of human entertainment, education, conservation, and scientific endeavour.

Their first priority is for the safety of the public, then zoo staff. Only after these are assured is the animal’s wellbeing considered. As evidence of such a policy, Thayne Maynard, Director of Cincinnati Zoo, expressed public regret for the loss of Harambe as a future breeding male, a loss of genetic diversity, without any consideration for Harambe’s rights.

Zoos should have a policy based on an ethical appraisal of potential incidents based on higher level principles. These would include utilitarian, deontological, and virtue ethics principles.

From a utilitarian perspective, the harm caused by shooting Harambe, to him, his family, human witnesses, and the public generally, may have outweighed the small risk to the child. Harambe’s family will mourn his loss and may even have been traumatised by the event.

Deontologists would argue taking Harambe’s life would never be justified by the small risk to the child – the shooting constitutes a supreme example of a speciesist approach.

Insights from virtue ethics show how this incident has damaged the zoo’s reputation. Public outcry has accused the zoo of having little regard for the rights of its animal occupants – although the safeguarding of the child’s life may be welcomed by some future visitors. Is this the action we would expect of a ‘good’ zoo?

Instead, the zoo seems to have acted from self-interest, afraid of potential litigation should the child be harmed. From a commercial angle a seventeen year old gorilla is worth $100,000 to $200,000; a child’s life many millions. However, the zoo is likely to experience reduced visitor numbers for a prolonged period, as well as being responsible for damage to the reputation of American zoos more generally.

The zoo may also be liable for placing visitors in a dangerous situation, something not unheard of in zoos around the world. Owners of swimming pools in Australia could teach the zoos a lot about preventing small children entering facilities, with detailed regulations and strict monitoring minimising any risk to children.

Some zoos may have deliberately sacrificed safety for an enhanced visitor experience, with limited barriers between the public and apparently dangerous animals.

Harambe’s killing may yet prompt a renewed movement to provide legal recognition of the rights of great apes.

Zoo animals already sacrifice many rights for the sake of human entertainment, education, conservation and scientific endeavour. Our ‘contract’ with zoo animals, where we provide nutrition, good health, and companionship in return for the animals sacrificing their freedom, right to live, and reproduce naturally in a state of good welfare, stack the terms heavily in our favour.

Indeed, killing a defenceless animal that had not shown any aggression is tantamount to tearing up that contract.

The ethical dilemma over whether to shoot Harambe might have been avoided if a movement known as The Great Ape Project had succeeded. For over twenty years a group of philosophers, primatologists, and anthropologists have attempted to gain great apes, including gorillas, rights through the United Nations that would include the right to life.

The movement is based on overwhelming evidence for self-consciousness and other higher level cognitive abilities in great apes, which are undoubtedly greater than in some disabled humans who are adequately protected in law.

Although this has gained support in some minority states, it has yet to gain widespread acceptance, primarily because of determined opposition from scientists who reserve the right to use chimpanzees – another great ape – for medical research. Harambe’s killing may yet prompt a renewed movement to provide legal recognition of the rights of great apes.

Just like Cecil the lion, the killers of Harambe are being judged in the arena of social media. The pattern of argument there suggests members of the public would have preferred that the zoo accept some risk to the child before taking the extreme action of killing a harmless gorilla.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

BY Clive Phillips

Clive Phillips is Chair of Animal Welfare and Director of the Centre for Animal Welfare Ethics at the University of Queensland.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Does ethical porn exist?

Does ethical porn exist?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Emma Wood The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2016

It’s hard to separate violence and sex in lots of today’s internet pornography. Easily accessible content includes simulated rape, women being slapped, punched, and subject to slews of misogynistic insults.

It’s also harder than ever to deny that pornography use, given its addictive, misogynistic, and violent nature, has a range of negative impacts on consumers. First exposure to internet porn in Western countries takes place before puberty for a significant fraction of children today. A disturbingly high proportion of teenage boys and young men today believe rape myths as a result of porn exposure. There is also evidence suggesting exposure to violent, X-rated material leads to a dramatic increase in the perpetration of sexual violence.

Before we can answer questions about the ethics of porn we need to address fundamental questions about the ethics of sex.

It is also difficult to deny that the practices of the porn industry are exploitative to performers themselves. Stories such as the Netflix documentary Hot Girls Wanted depict cases of female performers agreeing to shoot a scene involving a particular act, only to be coerced on the spot by the producers into a more hard-core scene not previously agreed to. Anecdotes suggest this isn’t uncommon.

While these facts about disturbing content and exploitative practices lead some people to believe consumption of internet porn is unethical or anti-feminist, it prompts others to ask whether there could be such a thing as ethical porn. Are the only objections to pornography circumstantial – based in violent content, exploitation or particular types of pornography? Or is there some deeper fact about porn – any porn – that renders it ethically objectionable?

Suppose the kind of porn commonly found online:

- Depicted realistic, consensual, non-misogynistic, and safe sex – condoms and all.

- Was free of exploitation (a pipe-dream, but let’s imagine).

- Performers fully and properly consented to everything filmed.

- Regulation ensured only people who were educated and had other employment options were allowed to perform.

- Performers did not have a history of sexual abuse or underage porn exposure

- Pristine sexual health was a prerequisite for becoming a porn performer.

- The porn industry cut any ties they are alleged to have with sex trafficking and similarly exploitative activity.

If all this came true, would any plausible ethical objections to the production and consumption of pornography remain?

Before we can answer questions about the ethics of porn, we need to address fundamental questions about the ethics of sex.

One question is this: is sex simply another bodily pleasure, like getting a massage, or do sex acts have deeper significance? Philosopher Anne Barnhill describes sexual intercourse as a type of body language. She thinks that when you have sex with a person, you are not just going through physically pleasurable motions, you are expressing something to another person.

If you have sex with someone you care for deeply, this loving attitude is expressed through the body language of sex. But using the expressive act of sex for mere pleasure with a person you care little about can express a range of callous or hurtful attitudes. It can send the message that the other person is simply an object to be used.

Even if not, the messages can be confusing. The body language of tender kissing, close bodily contact and caresses say one thing to a sexual partner, while the fact that one has few emotional strings attached to them – especially if this is stated beforehand – says another.

We know that such mixed messages are often painful. The human brain is flooded with oxytocin – the same bonding chemical responsible for attaching mothers to their children – when humans have sex. There is a biological basis to the claim that ‘casual sex’ is a contradiction in terms. Sex bonds people to each other, whether we want this to happen or not. It is a profound and relationally significant act.

Porn consumption can become a refuge that prevents people otherwise capable of the daunting but character-building work of seeking a meaningful sexual relationship with a real person.

Let’s bring these ideas about the specialness of sex back to the discussion about porn. If the above ideas about sex are correct, then there is cause for doubt over the idea that it is the sort of thing that people in a casual or even non-existent relationship should be paid for. So long as there are ethical problems with casual sex itself, there will be ethical problems with consuming filmed casual sex.

So what should we say about porn made by adults in a loving relationship, as much ‘amateur’ (unpaid) pornography is? Suppose we have a film made by a happily married couple who love each other deeply and simply want to film and show realistic, affectionate, loving sex. Could consumption of such material pass as ethical?

Maybe it could, but many doubts remain. Porn consumption can become a refuge that prevents people otherwise capable of the daunting but character-building work of seeking a meaningful sexual relationship with a real person from doing so. Porn (even of the relatively wholesome kind described above) carries no risk of rejection, requires no relational effort and doesn’t demand consideration of another person’s sexual wishes or preferences.

Because it promises high reward for little effort, porn has the potential to prolong adolescence – that phase of life dominated by lone sexual fantasies – and be a disincentive to grow into the complicated, sexual relationship building of adulthood.

Based on this line of thinking, there may still be something unvirtuous about the consumption of porn, even that was produced ethically. Perhaps the only truly ethical, sexually explicit film would be of people in a loving relationship, which is seen only by them.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

BY Emma Wood

Dr Emma Wood is a research associate at the Institute for Ethics & Society at the University of Notre Dame Australia. Her research interests include metaethics, applied ethics and philosophy of religion.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

Begging the question is when you use the point you’re trying to prove as an argument to prove that very same point. Rather than proving the conclusion is true, it assumes it.

It’s also called circular reasoning and is a logical fallacy.

Should I trust Steve?

Premise: Steve is a trustworthy person because I trust him.

Conclusion: Therefore, you should trust Steve.

Let’s replace the word ‘trust’ with ‘love’.

Premise: Steve is a lovable person because I love him.

Conclusion: Therefore, you should love Steve.

Are you any closer to figuring out why Steve is trustworthy or loved?

As a logical argument, here’s how it looks.

Premise: Steve is X because X.

Conclusion: Therefore, you should X because X.

The conclusion and the premise make the same claim. That is, they say the same thing.

Though the logical structure is valid, there’s no argument to move on from. We’re no closer to understanding why Steve is trustworthy or lovable.

Rather than assuming the conclusion is true from the beginning, let’s prove it.

Premise 1: Reliable people can be trusted.

Premise 2: Steve is a reliable person.

Conclusion 1: Therefore, Steve can be trusted by any person.

Premise 3: You are a person.

Conclusion 2: Therefore, you should trust Steve.

This way, even if Steve is clearly trustworthy, you’re using a good argument to help his case.

A leading question

Here’s another related example:

‘If we accept your argument that people who download movies should be put in jail, who should provide the education they receive while they’re in prison?’

This is called a leading question. It sneaks in a claim that needs to be argued for in the form of a question.

In this example, the claim is that people who are put in jail should receive education programs. That might be true, it might not, but because it forces the answer to go in a certain direction, it is an example of begging the question.

Radio interviews and talk shows conversations can beg the question by asking leading questions that try to box you in to a certain answer. Being able to spot a leading question is useful – it allows us to be critical not only of other people’s arguments, but the way they frame the question.

Note: when people say ‘this begs the question that’ they actually mean ‘this raises the question that’. In this context, they’re usually not referring to the logical fallacy.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology