Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 6 OCT 2023

Ethical dilemmas are, by their nature, uncomfortable or difficult to tackle, but they can also teach us a lot about our own values and principles and prepare us for an ethically complex world.

You’re about to take a major exam that will determine whether you get accepted into a potentially life-changing course. But you hear that there’s a leaked copy of the exam paper doing the rounds, and other students are studying it carefully. There are only a precious few spots available in your desired course, and if you don’t also sneak a peek at the leaked exam paper, you are likely to miss out. Should you cheat by looking at the leaked exam paper, given you know other students are doing the same?

How about if you found out that the company you work for was partnering with an overseas contractor known for running sweatshops and flouting labour laws, meanwhile your company’s branding is all about how ethical and sustainable it is. Would you speak out to management, or on social media, even if doing so might cost you your job and income?

If these scenarios give you pause, you’re not alone. Each represents a different kind of ethical dilemma we might come across, and by their nature they can be highly unsettling and difficult – if not impossible – to resolve in a way that satisfies everyone involved.

But what makes something an ethical dilemma? It’s important to note that an ethical dilemma is not a simple question of doing the ‘right’ thing or the ‘wrong’ thing, like whether you should lie to cover up for something bad that you did.

A genuine ethical dilemma arises when there is a clash between two values (i.e., what you think is good) or principles (i.e., the rules you follow). Or it can be a choice between two bad outcomes, like knowing that whatever you do, someone will get hurt.

That’s what makes them so uncomfortable; we feel like whatever choice we make will involve some kind of compromise.

All in the mind

One way to prepare yourself to face real-world ethical dilemmas is to strengthen your moral muscle by practicing on hypothetical scenarios – a staple of philosophy classes.

Consider this: you’re the captain of a sinking ship, and the lifeboat only has room for five passengers. Yet there are seven people aboard the ship, including yourself. Whom do you choose to board the lifeboat? The pregnant woman? The ageing brain surgeon? The fit young fisherman? The teenage twins? The reformed criminal who is now a priest? Yourself?

Or how about this: you’ve just started your shift as the only surgeon in a small but high-tech hospital. As you walk into your ward, you’re presented with five dying patients. You know nothing else about their personal details except that each is suffering from a different organ failure. Without assistance, all will die within 24 hours. However, at that moment, a healthy patient is wheeled in for an unrelated minor procedure. You also know nothing about their personal circumstances, but you do know they have five perfectly healthy organs. Were you to allow that patient to die (as they will without treatment) you know you could save the lives of the other five dying patients. Would you allow one to die to save five?

Each of these scenarios is carefully constructed to put pressure on your ethical intuitions and force you to make difficult decisions.

Tackling a hypothetical dilemma gives you an opportunity to reflect on your own values and principles, and search for good reasons to justify your choices.

Even if the hypothetical situation is absurdly unreal, you can still learn a lot about yourself and your ethical stance by considering how you would act in these cases.

Your first impulse might be to try and change the circumstances to eliminate or minimise the dilemma. We might speculate that we could squeeze another person on the lifeboat, or that the organ transplants may not succeed, and that might make our decisions easier. This is entirely natural – and sensible – especially because dilemmas in the real world are rarely as clear cut. But dodging the dilemma misses the point of the exercise.

You might decide that a consequentialist approach is the best one for the lifeboat scenario, causing you to pick the people who might end up leading the richest lives or having the most positive impact on others. But you might decide that a deontological approach is most appropriate for the surgeon’s dilemma, arguing that it’s inherently wrong to withhold treatment from an ‘innocent’ patient, even if it ends up saving lives.

It’s important to remember that hypothetical dilemmas like this are designed so that there’s likely no simple answer that will satisfy everybody. Even reasonable people can disagree about what course of action to take. That’s fine. The important bit is not really the answer you come to but the reasons you give to support it. That’s what ethics is all about: finding good reasons to act the way we do.

Most of us are likely to go through life without ever having to put people in lifeboats or contemplate the death of one to save five, but by testing ourselves with these dilemmas we can build our ethical muscles and be more ready to face other dilemmas that world could throw at us at any time.

If you’re struggling with a real-life ethical dilemma, it can be tough finding the best path forward. Ethi-call is a free independent helpline offering decision-making support from trained ethics counsellors. Book a call today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

When identity is used as a weapon

When people reduce an artist to one aspect of their identity, whether it be gender, ethnic or religious, it diminishes their humanity.

Identity is indelibly linked to our individual and collective places in the world. It is a marker, across many classifications, that creates distinctions that can help or harm us. But should it have such power? Is there any neutrality to how we create for public consumption, and if not, how can there be neutrality in how these are critiqued? Even with the cultural, social, sexual and other differences, surely there is acceptance that stories do – and should – have universal value?

A few years ago, Ruby penned an influential essay noting that, sometimes, white arts reviewers seemed unable or unwilling to see past ethnicity in literary criticism. In particular, there was an apparent tendency to take everything an Arab artist says literally, as if style, metaphor, flair and all the other features of literary penmanship were simply beyond our capabilities. It was not an objection to white reviewers critiquing the work of non-white artists. It was simply asking: “How do we respond when white reviewers can’t understand our work fairly enough to critique it?”

It was disheartening to see, some years later, the same issue rear its head, again in the pages of prestigious literary journals, again taking an Arab author to task by refusing to accept his work as fiction and insisting it must be thinly disguised autobiography. This time, however, the criticism was spearheaded by other Arabs.

Acclaimed Arab-Australian poet and novelist Omar Sakr was the subject of a bizarre string of connected critiques of his debut novel Son of Sin, two of which were written by Arabic speakers. What links these essays is not an issue with Sakr’s narrative style, plot structure, or characterisation but a fixation on his personal life and method of transliterating Arabic expressions, with the latter dismissed as too crude and incorrect to pass muster as ‘genuine’ Arab storytelling. His credibility diluted under the more ‘authentically Arab’ gaze of these two reviewers, Sakr’s Arabness was put into question.

It was extraordinary to witness such a coordinated attack on someone’s identity, only for identity itself to then be used to mask the attack. The implication being that as an artist, Sakr’s identity is fair game, but as his critics, theirs is beyond reproach.

As two Arab women who have both been critiqued extensively and who have critiqued the work of others, we are no strangers to writing and talking about these issues. We do not hide our Arab heritage, how this has informed our work, and how we are perceived and treated by wider society.

But what we have to offer is also of value to non-Arabs. Both of us have tried, over many years, to normalise rather than ‘otherise’ our experiences as a minority.

We believed that in being open about our identity – and the backlash we receive for it – we would eventually be able to transcend, not the identity itself, but the defining role it too often plays in our professional as well as personal lives. To make it a part of us but not all of us so that we may break down rather than reinforce the figurative walls that separate us.

Ruby’s portfolio of media work includes more than a decade of arts criticism, political analysis, and feature articles on everything from mental health to homelessness to pop culture. It is her work on race, however, that attracts the most attention and spurs the most backlash. Often, when critics accuse us of “making everything about race,” they are simply revealing their own tendency to see us only in racial terms. Our input on general societal matters considered irrelevant, we are simultaneously expected to have nothing more than our identity to offer and then berated for offering it on our own terms.

There is an endless thirst for stories that confirm the oppressed Arab woman archetype, only for this archetype to then be used against us. A workplace manager once told Amal that her “difficulty” with authority had something to do with her upbringing and the men in her life, while another taunted her about her perceived (lack of) sex life. Even as a journalist reporting for trade publications she was reduced to her identity – and found wanting.

Defying these forced identity markers, Amal went on to write several books that traverse universal themes, from the divine and spiritual belief, to ageing and how we live. Her novels explore connection, love and personal evolution, all centring Arab women raised in Australia but who remain connected to the homeland, primarily Palestine. But the stories are not about this. Navigating dual worlds; these characters acknowledge but are not defined by their heritage. It is their reality and normality. They do not exist to address stereotypes but as characters in their own right. They just are, without apology or reduction or explanation.

Still, media coverage of her work often reverts to stereotype, accompanied by images of women in headscarves or headlines about Amal’s faith. Every image, every headline, seemingly there to remind us that, even when our work subverts it, we cannot outrun that archetype.

We are more than decades of trauma and displacement. We are not conflict. Our dispossession is not the definition of who we are, and what we can achieve. But in a social climate of such gatekeeping as to which Sakr was subjected, can we ever simply be writers or does our ethnicity mean we can only be Arab-Muslim ones? Must we write merely to educate and inform, only to live in fear of being deemed not Arab enough, or can we be creative storytellers in our own right?

For all the discourse about identity and discrimination, including the much-needed influx of historically marginalised voices, it seems that there is an attachment, both from the dominant society and from within these marginalised groups to maintain the status quo. Reducing us to the barest, stereotypical elements of our racial heritage – whether or not we wear a headscarf; if we transliterate “uncle” correctly – we are refused an existence outside of its constraints.

It is hard not to conclude that we are entering – if not already immersed in – a social landscape in which our identities are not lived but performed, and our existence is not normalised but capitalised upon.

How do we recalibrate so that we may embrace identity without being reduced to it? At the very least it requires an acknowledgement that we are not here to tick boxes with our difference. We tell stories not to meet the arbitrary standards of those who unethically wield identity like a cudgel but because humans always have. Our stories are not only cultural records but also historical ones, telling us where we have been and where we can go.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

BY Ruby Hamad

Ruby Hamad is a journalist, author and academic. Her nonfiction book White Tears/Brown Scars traces the role that gender and feminism have played in the development of Western power structures. Ruby spent five years as a columnist for Fairfax media’s flagship feminist portal Daily Life. Her columns, analysis, cultural criticism, and essays have also featured in Australian publications The Saturday Paper, Meanjin, Crikey and Eureka St, and internationally in The Guardian, Prospect Magazine, The New York Times, and Gen Medium.

Do Australian corporations have the courage to rebuild public trust?

Do Australian corporations have the courage to rebuild public trust?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Carl Rhodes 27 SEP 2023

Corporate Australia is having a rough time in 2023.

PwC made headlines for selling out Australian citizens by flogging details of the government’s tax avoidance schemes to potential corporate tax avoiders. Qantas has been raked over the coals for, amongst other things, lying to customers and illegally sacking workers. Elsewhere corporations are pilloried for scandalously excessive executive pay, Dickensian industrial relations standards, wilfully aggressive tax avoidance, and heartless profiteering.

Research by the market researchers at Roy Morgan recently revealed that the level of trust Australians have in corporations is at the lowest it has ever been since they started measuring it. The downward trend started with COVID but has been in free fall since the middle of 2022. Roy Morgan CEO Michelle Levine describes what is going on as the result of ‘moral blindness’ of corporations.

There is an apparent irony in play. Today’s corporations are accused of this moral blindness, while many publicly embrace ethics by taking increasingly active roles in important matters of public purpose and social impact. Corporations are weighing in on a variety of crucial political issues, such as the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, LGBTQIA+ rights, and the climate crisis.

Business as a force for good?

In the era of ‘woke capitalism’ the business world seems to feel little cognitive dissonance, let alone hypocrisy, about parading their ethical credentials in public while acting like ruthless and exploitative profiteers in the market. Being economically exploitative and socially progressive is the name of the game for many corporations.

The socially progressive position regards businesses as having the potential to be a ‘force for good’, especially by adopting progressive positions on social and environmental causes. Think of Qantas’ ‘pride flights’, PwC’s commitment to social impact, or the broad adoption of diversity and climate change initiatives by businesses of all kinds.

Many regard corporate engagement with political causes as being genuinely motivated by ethical care for their ‘stakeholders’. This view is not universal. Others see corporate activism as comprising of shallow, inauthentic and self-interested grandstanding. Between green-washing, woke-washing and virtue-signalling, corporations have been accused of using ethics to feather their own nests.

Yet others see corporate social and environmental engagement as incontrovertible evidence that CEOs have been held captive by radical left-wing activists. By this account weak-willed executives are being exploited by nefarious militants trying to use corporations as a Trojan Horse to infiltrate mainstream society.

The ‘vile maxim’ of corporate selfishness

Whichever position you might be aligned with, so-called ‘woke’ practices are in apparent contrast to the exploitative and ruthless competitive behaviours of companies like Qantas and PwC that have contributed to the demise of trust in corporations. When it comes to business, the ethical principle at play is akin to what, many years ago, economist Adam Smith condemned as the ‘vile maxim’. As he wrote in The Wealth of Nations back in 1776:

“All for ourselves and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind. As soon, therefore, as they could find a method of consuming the whole value of their rents themselves, they had no disposition to share them with any other persons.”

It is clear that many people running businesses today are enthusiastic followers of this vile maxim. To suggest this is ‘moral blindness’ can be misleading because (no matter how vile) there is an ethics at play here, and one that is widely accepted. Ayn Rand notoriously championed such an ethics as being beholden to ‘the virtue of selfishness’. By Rand’s account, pursuing self-interest is a valid, if not desirable, moral position. She stood against sacrifice as being a moral principle, instead seeing merit in “concern with one’s own interests”.

Free market capitalism was, for Rand, an ideal manifestation of her ethics. This all suggests that selfishness is not moral blindness, it is part of an ethical system that drives much business behaviour. It is also the ethics that is at the heart of Australia’s lack of confidence in the corporate world.

How to build trust

Between the twin poles of ‘woke capitalism’ and the ‘vile maxim’ we have something of a corporate identity crisis. Increasingly selfish profit-seeking in the economic sphere is matched with attestations to the pursuit of public good in the social sphere. That is not to say that all companies are vile or woke, clearly many are not. It is a fair call that enough of them are that it has led to a breakdown of public confidence in corporate Australia.

What does this all mean for how Australian corporations can build public trust? One answer is resolving their identity crisis by truly embracing and communicating the role of business in a liberal-democratic society. While businesses are responsible for returns on capital investment, that is neither their sole nor primary purpose. Neither is supporting progressive social positions without concern for the economy.

In its present condition Australian corporate capitalism is characterised by skyrocketing economic inequality, excessive executive pay, inflation fuelled by profiteering, and increasingly precarious employment. That Australian citizens do not trust corporations is an entirely rational assessment.

Corporate Australia’s challenge is to actively recognise and pursue its real social purpose. This purpose is about driving innovation and economic growth for shared prosperity, providing meaningful and secure jobs with decent pay, paying taxes that fund public services, as well as ensuring investors get a reasonable return.

Rebuilding trust is simple. What remains to be seen is which of Australia’s fallen corporations will have the courage to abandon their attachment to the vile maxim.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

David Pocock’s rugby prowess and social activism is born of virtue

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

BY Carl Rhodes

Carl Rhodes is Dean and Professor of Organization Studies at the University of Technology Sydney Business School. Carl writes about the ethical and democratic dimensions of business and work. Carl’s most recent books are Woke Capitalism: How Corporate Morality is Sabotaging Democracy (Bristol University Press, 2022), Organizing Corporeal Ethics (Routledge, 2022, with Alison Pullen) and Disturbing Business Ethics (Routledge, 2020).

We are the Voice

We are the voice! No monarch, no prime minister, no politician can decide how our democracy works. Only we, the people, voting as a whole, can resolve fundamental questions of how we will be governed – and by whom.

And so it has come to us to decide if and how to correct an historic injustice. First perpetrated by British colonists, through the doctrine of ‘terra nullius’ and then compounded by those who drafted the now repealed Section 127 of our nation’s most sacred political document, the Australian Constitution, our ‘original sin’ was to deny the prior existence of Indigenous peoples occupying, for millennia, the territories we now call Australia.

With mixed motivations – some virtuous and some vicious – the colonists sought to silence those whose lands they occupied. Guns, germs and steel – all did their work aided by policies of cultural suppression and assimilation. Yet, while sometimes just a whisper, at other times a mighty roar, the voices of our First Peoples have continued to echo across the lands and waters that make up our modern nation.

The descendants of our First Peoples have now asked us to repair the jagged rip in the fabric of our shared history. Their request is that this be done through the one means directly controlled by Australia’s citizens – an amendment to our Constitution. Their request is that this act of constitutional recognition be in the form of listening. They merely wish to be heard in relation to laws that directly affect their lives. That is all. No right of veto. No right to decide. Not even a right to determine how their voice is to be heard – for that is a matter reserved to Federal Parliament. Just a right to be recognised and heard as a distinct voice, amongst the many others, enshrined in our Constitution.

The debate about how to respond to this request has been intense – occasionally rancorous, confusing and ill-informed. So, here are some of the most important questions to have emerged during the course of debate:

Is the proposal to create the Voice racist?

No. The Voice is intended to recognise First Peoples based on their heritage not their race. As a whole, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders carry within their veins the blood of many races. Some of the staunchest opponents of the voice acknowledge this as a personal truth. The proposed constitutional recognition does not privilege race, it merely recognises people based on their descent from those who held original sovereignty over the lands and waters that, collectively, make up Australia.

Is it not just as wrong to recognise descent as it is race?

Not necessarily so. The Act that establishes the Australian Constitution already applies this principle in Section 2 which reads:

The provisions of this Act referring to the Queen shall extend to Her Majesty’s heirs and successors in the sovereignty of the United Kingdom.

It is the principle of ‘descent’ that made the late Queen Elizabeth our monarch – as it makes Charles our King – as will it make his son and his son rule over us for as long as we remain a constitutional monarchy.

Aren’t Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders divided on this question?

Yes. Some, like critics, such as those amongst the Blak Sovereign movement, demand much more. Others fear that adding a new voice to our Constitution will perpetuate division between the descendants of the First Peoples and those without those ancestral connections. Even so, it is estimated that around 80% of First Nations people support the proposal to recognise them in the Constitution through the establishment of an enshrined Voice to parliament and Government.

However, we should no more expect unanimity amongst our First Peoples than we do amongst any other group. Indigenous people are as divergent in their political opinions as is any other group of Australians.

Besides, if you read the minutes of the earliest constitutional conventions it soon becomes evident that virtually every clause in the current Constitution has been the subject of fierce debate and heated controversies. So, disagreement about potential clauses in our Constitution is nothing new. It is the ‘bread and butter’ of constitutional development and reform.

Is there any guarantee that a Voice will rapidly improve the lives of First Nations people?

A ‘yes’ vote will not immediately solve the problems of post-colonial poverty and disadvantage that blights the lives of so many descendants of our First Peoples. Nor will every grievance be reconciled. But things will be better than before. There will be reasons to hope that progress is possible. Also, it’s pretty clear that what we have been trying up until now has not been working.

What if we change our mind about the need for a Voice?

If at some time in the future the job of listening is done and reconciliation is practically complete, then we can always undo what I hope we will do, together, on October 14th. That’s the most important fact about our Constitution. Nothing is set in stone. Everything can be remade in whatever form the citizens of Australia prefer, from time to time. If something does not work, we can just change it.

Isn’t it undemocratic to confer rights on some citizens that are not enjoyed by others?

Yes, but that is already how our Constitution operates. Australian citizens living in the NT and ACT only have four Senators representing their interests (2 each). Tasmanians have 12 Senators – despite having a population smaller than that of the combined territories. We do not hear too many protests about the ‘undemocratic’ nature of this arrangement.

However, what exactly is the ‘right’ being accorded to First Peoples? And is it a right denied to any others citizen? In fact, the proposed amendment merely confers a right to make representations – and nothing more – which is the same right enjoyed by any Australian citizen whether making representations as an individual, as a member of community defined by ethnicity, faith, location, etc.

How can we vote on constitutional change without first having all of the details about how it will work?

The Australian Constitution contains little detail about how the powers of the Australian Parliament and Government are to be exercised. The Constitution merely lists, in general terms, the various ‘heads of power’ (e.g. see Section 52) – and then leave the rest to parliament and the government to decide the detail. Exactly the same approach is being taken with the proposed Voice. If ‘certainty’ was a precondition for voting in favour of the Constitution, as originally drafted and proposed, then it would never have been passed. Why do we require certainty in this matter alone?

I will be voting ‘yes’ in the referendum. I will do so because I want us to fill a gaping hole in our Constitution. Those who drafted the original document it did a pretty good job. But they left out a crucial ingredient – and we are all poorer for that mistake. The Australian Constitution brought into existence a new nation by preserving the Colonial States in a federation. Even New Zealand was included! But they left out the oldest parts of our nation – the multiple sovereign Indigenous states that existed prior to colonisation. No smaller than places like Monaco, Lichtenstein and San Moreno, our pre-colonial states had well-defined borders, enforceable laws, governance structures and so on.

Like a car without a boot or, a birthday cake without candles or, a paragraph without punctuation, our Constitution works well enough. But it is not complete. It is time that this error was corrected by according our First Peoples a modest but honoured place in our Constitution.

I sincerely believe that the creation of the Voice will benefit the whole nation – not just its First Peoples. It will be a bridge that connects the ancient voice of our country with the modern. It will enable crossings in both directions; making us, as a people, both distinctive and whole.

We are the voice. We need utter just one word to create a new reality… ‘yes’.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

An angry electorate

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Australian debate about asylum seekers and refugees

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 21 SEP 2023

Any fair society should ensure that everyone has dignity in old age. This isn’t some utopian aspiration. It is an ethical minimum required for us not collectively to hang our heads in shame.

But it isn’t easy and it certainly isn’t cheap.

The question of how to fund aged care is a can that has repeatedly been kicked down the road, because it will invariably require unpopular decisions. Recently the Albanese government has shown an inclination to tackle the difficult issue. Anika Wells, the aged care minister, has formed a task force to implement recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. This includes the prospect of introducing an aged care levy, an option dismissed by the previous government.

On its face, a levy seems sensible. Those people earning money ought to be more able to pay than those who are no longer in work. Even if, in the future, these working people do not need to use public aged care, it acts as an insurance policy for them and, on a more fundamental level, it satisfies our ethical obligations to protect the most vulnerable people in our society. Yet, the idea of a levy isn’t popular, which isn’t surprising: people generally don’t like higher taxes. However, scepticism and even anger over the prospect of a new levy doesn’t necessarily come from a place of selfishness.

A levy would affect young people most and they will likely resent the imposition. We are not talking about solipsistic Millennials and Zoomers wanting to indulge in an orgy of avocado toast and flat whites while their elders live in miserable poverty. The levy would require them to pay for the care of an older generation which by almost all metrics has had it easier. The benchmarks of the ‘Australian dream’ have become unobtainable for many young people, who have had to take on extraordinary debt for tertiary education, pay ever rising rents with homeownership out of reach as house prices skyrocket, delay starting families with childcare and associated costs rising, while inflation continues to erode salaries which have been stagnant for years.

All this raises questions about intergenerational justice and the social contract that binds us all together. The liberal tradition of the social contract, embodied in the work of a range of philosophers from 17th century John Locke to 20th century John Rawls, argues that we all can benefit through mutual cooperation, but we need rules to ensure the benefits and burdens are fairly distributed.

Social contract theory is often presented as a deal between the wealthy and the poor. It is a way of ensuring that the worst off in society are better off than they would otherwise be. To this we might add an intergenerational dimension. This makes intuitive sense; many would say that there is an obligation to ensure that each successive generation is better off than the one before or at least enjoys the same standard of living.

Locke’s theory of property helps to flesh out this intuition. On what grounds can we justify taking something out of the commons and saying “I own this”? For Locke two things need to happen:

- You have to mix your labour with something and

- You have to ensure that there is “enough and as good left”.

It is this second condition, which another 20th century philosopher, Robert Nozick called the ‘Lockean Proviso’ that is relevant here. It exists because if the starting point of property is that everything is owned in common, then private property becomes objectionable if it makes other people worse off than they were before. Locke gives the example of filling a bottle of water from a river. The water becomes yours because you’ve mixed your labour with it in the act of filling, but the river remains for anyone else who might wish to do the same. No one’s opportunities are diminished by your appropriation.

This Lockean Proviso connects to the social contract in a direct way. The terms of agreement would have to be such that each generation must leave ‘enough and as good’ for the next. If society does not provide the same set of opportunities, or better, for each generation then something has gone wrong with the distribution of benefits and burdens.

Young people may be able to generate income from work, but they are not the people with the most resources in society. Wealth is increasingly the domain of older people.

You might say “it always has been” – people who have spent their lives working are simply more likely to have more assets than those at the start of their careers.

Yet, if you look at important landmarks in the distribution of wealth, we can see the Lockean Proviso being eroded. In Australia, the proportion of wealth owned by Millennials and Zoomers is significantly smaller than that owned by Baby Boomer and Generation X at the same age. According to the Grattan Institute, the wealth of Australian households under the age of 35 has been stagnant since 2004, while the wealth of older households has grown by 50% in the same time period. This divergence has been exacerbated by generous tax concessions, so that during a period of major wealth accumulation the average income tax paid by over-65s barely changed and the number of older households paying income tax was halved. It is as if a dam has been built on Locke’s common river that provides no benefits for those who live downstream.

With this background, when it comes to aged care, young people may reasonably ask why they ought to carry the burden of paying. Surely, given the intergenerational distribution of opportunity and its fruits, it is fairer to make those who have benefitted most pay more? If the prevailing trend continues and the younger generation is increasingly forced to carry the burdens of social cooperation, then we can expect that more young people will begin to ask why they should continue to cooperate.

This need not be a battle cry to intergenerational warfare or collapse of the social contract. To satisfy the Lockean Proviso, asset-based wealth should be as open to any ‘levy’ as labour-based income.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The ethical price of political solidarity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

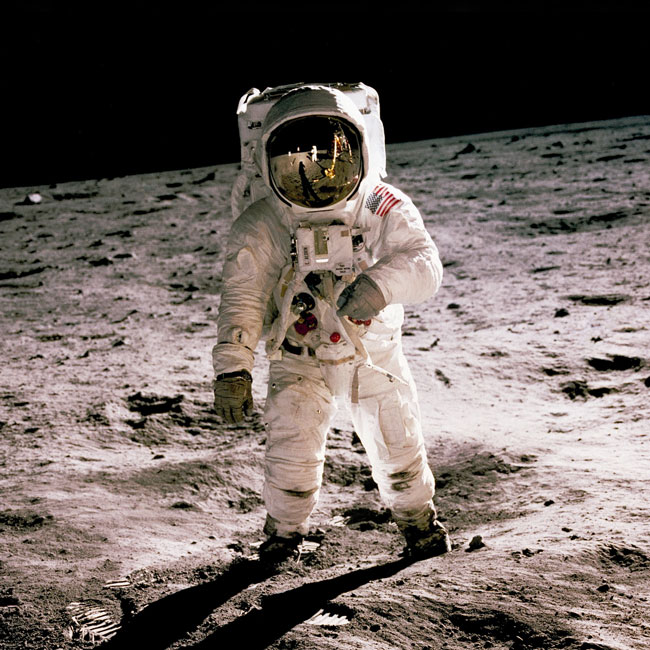

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Dr Elise Stephenson Isabella Vacaflores 14 SEP 2023

Greater representation of women and minoritised groups in the space sector would not only be ethical but could also have great benefits for all of humanity.

The systematic exclusion of women – and other minoritised groups – from all parts of the space sector gravely impacts on our future ability to ‘make good’ our space ambitions and live out the principle of equality. Minoritised groups refer to groups that might not be a minority in the global population (women, for instance) but are minoritised in a particular context, like the space sector.

Currently, more than half of humanity is treated as an afterthought for space tech billionaires and some government space agencies, amplifying dangerous warning signs already heralded by space ethicists and philosophers, including us. If these warning signs are ignored, we are set to repeat earthly inequalities in space.

Addressing the kind of society we want in space is crucial to fair and good decision making that benefits all, helping to mitigate risk and protecting future generations.

What does diversity in the space sector look like right now?

Research reveals that women have held 1 in 5 space sector positions over the past three decades. Across much of the sector, representation is at best marginally improving in public sector roles, whilst at worst, stagnating or regressing over a period where we should have seen the greatest improvements.

For example, of the 634 people that have gone to space, just over 10% have been women.

Our research has found that from the publicly available data, only 3 out of 70 national space agencies have achieved gender parity in leadership. Both horizontal and vertical segregation limits women – even in agencies that are doing well – pushing them down the organisational hierarchy and pigeonholing them out of leadership and operational, engineering and technical roles, which are often better paid and have higher status.

It is not just the most visible part of the space sector that is struggling to address the issue of gender inequality. Exclusion and discrimination have been reported by women occupying roles from astrophysicists and aerospace engineers to space lawyers and academics.

Prejudice is a moral blight for many workplaces, not least because it holds industry back from realising its fullest potential. Research finds that more diverse teams typically do this better and are more innovative – having a diverse mix of perspectives, experience, and knowledge ultimately helps conquer groupthink and allows a broader range of opportunities and complications to be considered. In the intelligence sector, diversity further helps “limiting un-predictability by foreseeing or forecasting multiple, different futures” which may be similarly relevant for the space sector.

Space exploration is a gamble, but getting more women and people from diverse backgrounds into the space sector will improve humanity’s odds.

In the context of space, failing to act on such insights would be morally irresponsible, given the risk taken by the sector on humanity’s behalf every single day.

Space is defined by the Outer Space Treaty as a global commons, meaning it is a resource that is unowned by any one nation or person – yet critically, able to be ‘used’ by any, so long as they have the resources to do so. As it stands, the cost and inaccessibility of space technology means that only a privileged few individuals, companies, and countries are currently represented in the space domain. In broader society, these privileged few are predominantly white, wealthy, connected men.

Being ‘good ancestors’ in the new space age

We might consider the principle of intergenerational justice espoused by governments or the ‘cathedral thinking’ metaphor by Greta Thunberg to describe the trade-off between small sacrifices now for huge benefits moving forward.

To further her metaphor, our ethical legacy is not shaped solely by our past, but also by our ability to be regarded as ‘good ancestors’ for future generations. These arguments are already being spurred in Australia by movements like EveryGen, Orygyn, the Foundation for Young Australians and Think Forward (among others) who are aiming for more intergenerational policymaking across many domains.

As the philosopher Hannah Pitkin notes, our moral failings arise not from malevolent intent, but from refusing to thinking critically about what we are doing.

A new space ethics

Whilst it will take some time to see gender parity occur in the space industry even if quotas or similar approaches are taken, there are still ‘easy wins’ to be had that would help elevate women’s and minoritised voices.

We found many women in the space industry who were interested in forming networks both within and between agencies and organisations. These typically serve a wide range of functions, from networking in the strict sense of the word to enabling a safe space to discuss diversity and inclusion or drive advocacy efforts. Research shows diversity networks having benefits for career development, psychological safety and community building.

Beyond this individualised, sometimes siloed approach, organisations also need to deeply commit to tackling inequality at a systematic level and invest in diversity, inclusion, belonging and equity policies which many in the space sector currently lack. Without transparently defined goals and targets in this area, it is difficult for organisations to measure their progress and, moreover, for us to hold them accountable.

Finally, looking to the next generation, the industry needs to engage a diverse range of students from different educational and demographic backgrounds. This means offering internships and educational opportunities to students that might not adhere to the current ‘mould’ of what someone looking in space looks like. For instance, the National Indigenous Space Academy offers First Nations STEM students a chance to experience life at NASA, whilst other initiatives across the sector include detangling the STEM-space link, to demonstrate the range of roles and opportunities available in the space sector for even non-STEM career paths.

In the height of the Soviet-American space race, JFK said: “we choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard”. Transforming the exclusive structures and patriarchal history of the space sector may not always be a simple task, but it is fundamentally critical on both a practical and moral level.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dark side of the Australian workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

BY Dr Elise Stephenson

Dr Elise Stephenson is the Deputy Director of the Global Institute for Women's Leadership at the Australian National University. Elise is a multi award-winning researcher and entrepreneur focused on gender, sexuality and leadership in frontier international relations, from researching space policy, to AI, climate, diplomacy, national security and intelligence, security vetting, international representation, and the Asia Pacific. She is a Gender, Space and National Security Fellow of the National Security College, an adjunct in the Griffith Asia Institute and a Fulbright Fellow of the Henry M Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington.

BY Isabella Vacaflores

Isabella is currently working as a research assistant at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. She has previously held research positions at Grattan Institute, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. She has won multiple awards and scholarships, including recently being named the 2023 Australia New Zealand Boston Consulting Group Women’s Scholar, for her efforts to improve gender, racial and socio-economic equality in politics and education.

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 13 SEP 2023

The Voice referendum is a high stakes decision that could affect many thousands of lives, and that means we have an ethical responsibility to choose how we vote carefully.

Not all decisions are created equal. Some are trivial in their consequences, like whether you choose the chocolate or strawberry ice cream for dessert. Some have higher stakes, like whether you decide to prioritise your career over travelling the world. Yet, these decisions still only affect how you live and are unlikely to impact anyone else.

You can make these decisions in a considered or a flippant way. Or you can choose to not make them at all (although doing so is still making a choice, of sorts). With low stakes personal decisions, you don’t even need to have a good reason for choosing what you do. The only person to whom you owe a justification is yourself – and you can always choose to free yourself of that burden.

But there are other kinds of decisions, ones that impact not just us but other people too. Decisions like these demand more from us and we cannot be so flippant with them. In these cases, we have a greater ethical responsibility to come to a more considered position, to weigh up the options more carefully, and be ready to justify our decision with good reasons.

This is the type of decision are we making when it comes to the Voice to Parliament referendum.

The stakes

In the case of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, the stakes are whether Indigenous peoples are afforded constitutional protection for a consultatory body that will advise government on legislation affecting their communities – a body that cannot be legislated away with a change of government.

Leading Indigenous figures representing peoples from across Australia and the Torres Strait have asked the Australian people to make the constitutional change because they believe such a consultatory body will have a significant impact on the wellbeing of their peoples and will help correct over two centuries of political disempowerment and discrimination.

Be a good citizen

So, you have a decision to make, one that will likely have a significant impact on a vulnerable population. That places an ethical responsibility on each registered voter to take the decision seriously. This means not treating it flippantly and having a principled reason for voting, regardless of which way you vote. This is what it means to be a “good citizen”.

It’s easy to think of citizenship as simply affording us rights, such a right to have a say in how we’re governed or a right to be treated fairly under the law. However, citizenship also bestows upon us responsibilities, like voting in elections and serving on a jury if called.

But these are just the minimal responsibilities involved in citizenship. We need to do more to be a “good citizen”, including keeping ourselves engaged in issues of public significance and maintaining a basic level of political literacy. A good citizen also doesn’t just grumble about the state of society, they act to make it better. Finally, a good citizen sees themselves as members of an interconnected society, and is willing to make sacrifices or compromise for the common good. So, a good citizen will see the Voice referendum as an opportunity to exercise their responsibilities and engage with the issue actively to make an informed decision.

Be informed

The good news is that there is an abundance of information readily available for each of us to come to a principled decision. However, there is also a wealth of misinformation and disinformation floating around as well. Some of this is shared due to genuine confusion and some is spread by bad faith actors who have their own motivations for attempting to sway votes.

Explore what you really think

This is why it’s important to look at who is speaking and understand their motivations, which might not always be reflected in their arguments. Many people are motivated to vote one way or the other simply because that’s how their perceived political allies are voting, or they might be swayed by unconscious biases and use plausible sounding arguments as post-hoc rationalisations for how they feel deep down.

You can tell that someone is pushing post-hoc rationalisations when you successfully challenge their argument, such as by showing they have been duped by misinformation, but they still don’t change their mind. In this case, simply throwing more facts at them is unlikely to sway them.

A more successful approach is to be sceptical that the first reasons they give are the true motivations for their views. Instead, ask more questions about why they believe what they do and what they’re concerned will happen if the vote doesn’t go their way. Ask questions about how they can be confident their facts are true or what it would take to change their mind.

Rather than positioning yourself as an opponent, try taking the stance as a fellow traveller trying to get to the bottom of the matter. If you’re able to show respect, build trust and lower defensiveness, you’ll have a better chance of opening their mind to alternative perspectives – although it’s also crucial to remain open to alternate perspectives yourself.

There is no right answer

This is because there is no one “right answer” to the referendum question. Reasonable people can disagree on whether a Voice to Parliament is the best mechanism to promote the welfare and representation of Indigenous peoples, or whether a Voice ought to be enshrined in the constitution. When discussing the issue with others, it’s easy to assume that people who disagree with us must harbour some problematic views or that they are simply misguided. Resist that urge and ask questions that aim to tease out good reasons for or against the Voice.

The stakes involved in the Voice referendum mean that we should all take our responsibility to vote in a considered way seriously, and we should be mindful of how we make our decision. Even though there are many pressing issues facing the Australian public, from the cost of living through to climate change, that doesn’t mean we can’t also engage with the longstanding issue of Indigenous disadvantage, especially because there’s often not much we can do about many big issues but we’ve been explicitly invited to have a say on the Voice.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

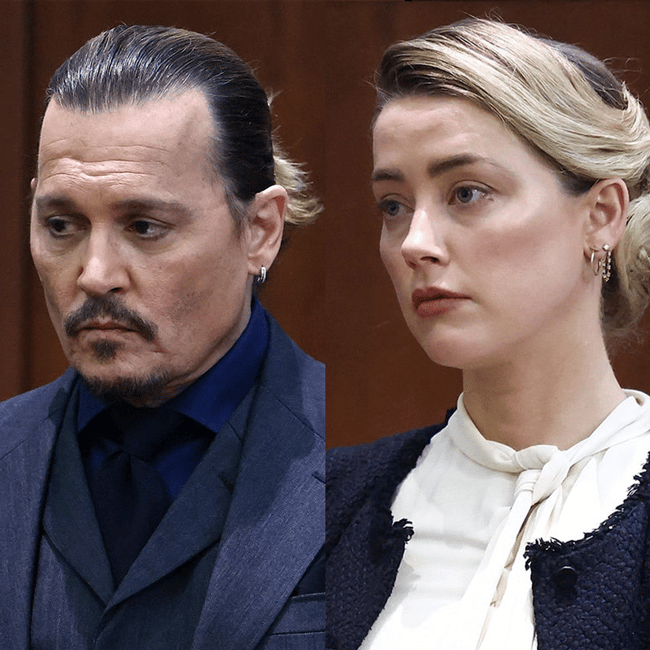

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

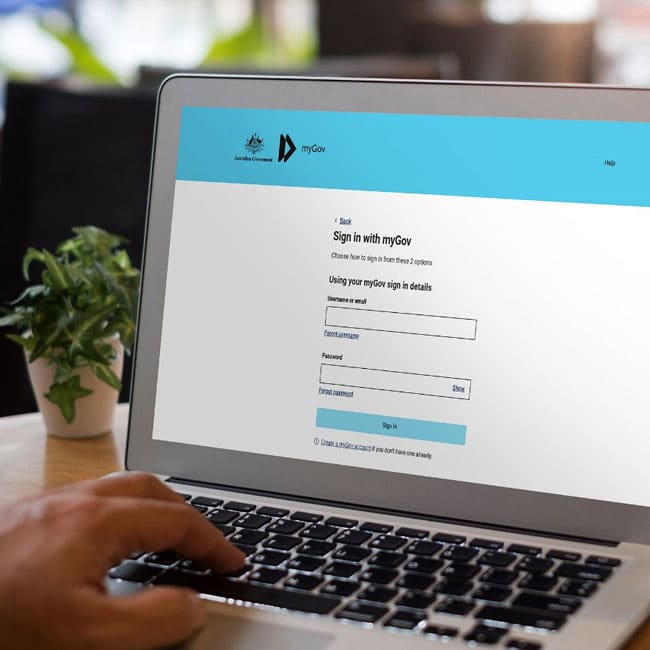

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Cris Parker 5 SEP 2023

Advancements in technology have shown greater efficiency and benefits for many. But if we don’t invest in human-centric thinking, we risk leaving our most vulnerable behind.

As businesses from the private and public sector continue to invest in improved digital processes, tools and services, we are seeing users empowered with greater information, accessibility and connectivity.

However as critical services for healthcare, lifestyle and support systems have become increasingly digitised, the barriers for vulnerable, remote or digitally excluded individuals must also be considered against these benefits.

It’s no wonder the much-maligned MyGov app underwent an audit review earlier this year, resulting in a major overhaul of the service. Reading through their chat rooms and forums where customers can express their experiences, comments like these fill the pages:

“…If you’re trying to do something online, even if you’ve got a super reliable connection, you can spend hours wandering around in a fog because there’s no transparency about – they’re not trying to make it easy for people.”

“You need to have acquired the technology to do it, but you get on their websites, and I don’t know who designs their systems. But you’ve got to be psychic to be able to follow what they want. In order to get what you need, you’ve got to run through this maze, it’s complete bullshit.”

“And you’re already putting elderly people and keeping them in a home, it all goes online and digital, they stop having that outside interaction. It’s another chip away of community. That’s where the isolation comes in.”

Reading these statements, you get a sense of the frustration and confusion felt, not just due to time wasted but also the loss of a personal connection and agency. These experiences can lead users to doubt the reliability of business’ processes and chip away at the trust in their systems.

The Australian Digital Inclusion Index cites digital inclusion as “one of the most important challenges facing Australia.” Their 2023 key findings presented that digital inclusion remains closely linked to age and increases with education, employment and income.

So, as technology becomes more ubiquitous in our lives, how do we maintain human centric thinking? How do we avoid exacerbating existing inequalities while maintaining respect, autonomy and dignity for all?

Looking for some answers, I spoke to Jordan Hatch, a First Assistant Secretary at the Australian Government and someone who is passionate about designing for user needs. Hatch is currently working with the care and support economy task force in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, exploring some of the challenges and opportunities across the care sector.

Hatch is acutely aware that amidst this digital transformation, the welfare of vulnerable individuals remains a priority. He explains human-centered design principles must play a crucial role in shaping digital solutions. Importantly, understanding the user base, including different cohorts and their specific needs, is foundational to designing inclusive services. Extensive research and involvement of First Nations communities, individuals with low digital literacy, or limited internet access are also essential to developing solutions that address their unique challenges.

Hatch explains how technology is transforming the face-to-face experience. He says the digitisation of services has prompted a re-evaluation of the role of physical service centres. The integration of digital and in-person channels is allowing for streamlined processes and improved customer experiences.

A great example is Service NSW, which has become a centralised hub offering access to several support services. The availability of digital options has not led to the exclusion of those who prefer face-to-face interactions. On the contrary, it has allowed for a more comprehensive and improved service for individuals seeking in-person assistance. The digital transformation has become a means to augment the service experience, rather than replacing it. When visiting a Service NSW centre, you are met by a representative who directs you to a computer and, if required, walks you through the online process, offering personalised support. This evolution caters to diverse needs, ensuring that the face-to-face experience remains valuable while offering alternative modes of engagement.

Of course, increasing the capability and use of technology has its downside. Digital interactions have become a societal norm and an opportunity for scams. This has led to a number of digital hoops users are obliged to make in an attempt to protect their data and privacy. This process can impact the users’ wellbeing as passwords are lost or forgotten and the digital path is often confusing.

Hatch explains in this learning journey, how a shift in his perception occurred regarding the relationship between security and usability. Previously, it was believed that security and usability were at opposite ends of the spectrum—either systems were easy to use but lacked security, or they were secure but difficult to navigate. However, recent technological advancements have challenged this notion. Innovations emerged, offering enhanced security measures that were user-friendly. For example, modern password theories promoted the use of longer passphrases consisting of simple words, resulting in both stronger security and increased user-friendliness.

Technological transformation is a process and technology is not a panacea – it is a steppingstone and an opportunity for simplification and identifying unique solutions. What we can’t do is allow technology to overshadow the need to address regulation and the complexity it can create.

Hatch shares an insight from Edward Santos, the former Human Rights Commissioner to Australia: the prevalent mindset of the technology world being, “move fast and break things”. This is often seen as innovation, and an opportunity to learn from failure and adapt. However, in the realm of public service, where real people’s lives are at stake, the stakes are higher. The margin for error in this context can have tangible consequences for vulnerable individuals.

Slowing down is not necessarily the solution, particularly when you see or experience the harm caused by a misalignment between requirements and the capacity to meet them. It is the work Jordan Hatch describes where the issue is not when, but how services are designed and delivered that will make the difference.

The intersection between technology and policy creates an opportunity for regulators and digital experts to come together. Rather than digitise what exists, they can identify the unnecessary complexities and streamline the rules. This then creates a win-win situation – through the lens of human-centred design, it facilitates the digitisation process and creates a simpler regulatory framework for those who choose not to use a digital process.

With this approach we can design technology to work for us rather than against us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Reports

Business + Leadership

Productivity and Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Corporate tax avoidance: you pay, why won’t they?

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 SEP 2023

Fittingly, for a show set in the brutal, immediate environment of a commercial kitchen, The Bear opens with a brutal, immediate metaphor for grief.

In the opening scene of the show, Carmy (Jeremy Allen White) traverses a bridge in the middle of the night. We know nothing of this man yet. He moves fearfully, slowly. And in a moment, we see why – there’s a vicious bear across from him, reared up and snarling, and Carmy is desperately, fearfully trying to placate it.

Within an episode, the symbolism is obvious. The bridge represents what we will soon come to see as an uncomfortable, dangerous transition Carmy has been thrust into – he has left behind a world of chef superstardom, in order to take over ownership of the middling sandwich shop left to him after the suicide of his brother. And the bear? It is the manifestation of the grief he has been left with; this terrible, unpredictable thing, that he has no idea how to confront, or how to contain.

On its surface, The Bear is about kitchen life. It nails perfectly the stress; the heat; the ugly mechanics of what goes into our food. Anthony Bourdain was right – when you eat out, and get served a dish on a perfectly clean plate, what you haven’t seen is the often literal blood, sweat, and tears that produces it. The Bear spends its two seasons documenting those bodily fluids in sometimes gratuitous detail.

But as its opening scene establishes, what The Bear is really about is untethering. More specifically, the way that grief untethers – the way it throws us back into a world we thought we knew but is now suddenly unfamiliar to us, as we stand under its hot kitchen lights, naked and afraid.

What grief does to us

Carmy is a man with his own dark past. In flashbacks, we see him abused by kitchen bosses. We learn more about Michael, his dead brother, who struggled with addiction. And, drip by drip, we learn about the family dynamics and pressures that made Michael both who he was, and who he died as, and who Carmy once was.

What we also learn is the way that grief can provide a sort of brutal reset of personhood. When we lose someone close to us – whether it be a family member, as in the case of Carmy, or a lover, or a friend – we speak often of losing something of ourselves too.

This cuts to the beauty of human interaction – something that the philosopher Derek Parfit often wrote about. Love, be it familial, platonic, or romantic, erodes the boundaries between the self and other. Our natural inclination as humans to learn about each other, to take on the cares and emotional states of those close to us, to constantly empathise and put ourselves in other’s shoes, makes us less like distinct individual entities, and more like what the philosopher Anette Baier once called “heirs and successors to those that we care about.”

This is beautiful, yes, but it also makes us deeply vulnerable. It means that death and suicide doesn’t just have the power to remove one human being from the world. It means that death and suicide has the power to remove part of us as well.

The philosopher Bryanna Moore has written about this in her paper ‘The Three Moral Dimensions of Grief.’ Moore understands human beings as relationally defined. She takes a sort of refined, tweak “no self” view of personal identity. On her reading, we are not hermetically sealed entities, with some stable, unchanging identity. We are who we are because of who we love, hate, and spend time with.

So for Moore, grief “reveals something vital about the way in which we relate to ourselves around us.” When Carmy loses Michael, he is forced into what Moore calls “a powerful reassessment and reevaluation of the self’s relation to the world.” This explains in great part why Carmy decides to take on Michael’s restaurant. It’s not just guilt that makes him want to help the brother who he could not help in life. It’s that he now no longer knows who he is. He is fresh and untethered. There is a gap, where Michael once was, but there’s also a gap where Carmy once was.

The moral value of grief

Robert C. Soloman, another philosopher who has written extensively about grief, argues in tandem with Moore that grief’s power to untether us makes it, to some extent, “morally excellent.” Soloman starts with the idea that grief is morally obligatory. As in, if someone we care about dies, and we do not grieve, then we have done something immoral – we have failed in some way. Grief is a necessity; it isn’t just some replacement of the love we once felt towards the departed, it is that love, taking on a new form.

For Soloman, the excellence comes from the way that grief represents an “emotional process.” It’s not just a feeling, a discrete emotional state that comes over us. It’s something that builds, grows and changes. This, we quickly find, is true with Carmy. We see him move constantly through different stages and states of grief, at times anger, at other times remorseful; always on the move, and always finding himself plunged into new emotions.

As to what kind of process grief is, it’s one of reconstruction. When we are untethered by loss, we are then forced to get to work on rebuilding ourselves. Grief heightens and sharpens us, makes us present in activities and choices. Carmy finds himself suddenly lit up by chefing in a way that he has not been before, dealing with the chaos of his new restaurant, but immersed in it, and learning new things about himself as a result.

It’s Moore who points out that rebuilding oneself need not always be positive, or moral. After all, there are many people who respond to traumatic events by becoming a new type of person, but a worse one – meaner, angrier, less forgiving. Grief gives us a blank slate, and it’s up to us what we then build on top of that slate.

The goodness of grief, then, comes from the way that it makes us present; intentional. So often we move through life making choices passively; letting things happen to us. When we are left with nothing, and we must rebuild, every choice becomes heightened – we become aware of them, in a way that we were not before.

Grief can wake us up from a stupor, shake us out of immoral patterns that we did not even realise that we had fallen into.

This, we see, happen with Carmy. Slowly, sure. He makes mistakes. He hurts others. He fails. But he is, after his hard reset, aware. Paradoxically – beautifully – a death has made him, quite to his surprise, suddenly and thrillingly alive. In that way, Michael’s passing wasn’t just a loss. It was, against the odds, a gift. And there is beauty in the way that Carmy takes it in his pale, open hands.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luara Ferracioli 17 AUG 2023

A liberal society like Australia should recognise that many intimate relationships matter, and in its approach to immigration the federal government should try as much as possible not to prioritise some relationships over others — unless it has a very good rationale for doing so.

A recent report by the Scanlon Foundation has shed some important light on how the current family migration scheme in Australia is failing foreign-born citizens, permanent residents, and their adult parents who want to join them in Australia.

According to the report, there are almost 140,000 Australian residents waiting between 12 and 40 years to be permanently reunited with their parents. The best route is to fork over $48,365 per parent. This contributory visa currently has an expected processing period of 12 years. The cheaper, non-contributory version of this visa costs $4,990 per parent and the application may take 29 years to process.

Since the Parkinson review into Australia’s migration system was established in September 2022, much of the public commentary has focused on the unfairness of leaving adult citizens and their parents in limbo. The expert panel itself puts it bluntly: “Providing an opportunity for people to apply for a visa that will probably never come seems both cruel and unnecessary.”

There is no doubt that the government urgently needs to reform its approach to migration, and visas need to be processed within a reasonable time-frame so that prospective immigrants can move on with their lives. There are, however, two other unfair elements baked into the Australian family migration system that also need addressing.

First, there is the cost of the contributory visas. A visa of almost $50,000 only allows affluent foreign-born citizens to bring their parents to Australia. But if this visa is meant to promote the interest we all have in enjoying territorially located intimate relationships in an on-going fashion, then it is grossly unjust that the wealthy are given a much better shot at having that interest protected.

The second unfairness is perhaps even more under-appreciated. Why prioritise parents as opposed to other adults that citizens and permanent residents might care deeply about? Whereas some are no doubt very close to their parents, others are very close to an uncle, an aunt, or a third-degree cousin. Whereas some individuals long to spend more quality time with a parent, others would really like to live closer to their best friend.

This point becomes clearer when we recognise that sometimes friends are much more emotionally dependent on one another than immediate family members. A citizen who would genuinely lead a much better life if her best friend was allowed to move to Australia then lacks access to a visa that allows a fellow citizen to bring an adult parent into the country, irrespective of how emotionally close they are.

My point is not that the government should assess the level of intimacy between an adult citizen or permanent resident and a parent.

As a liberal society, we need to respect people’s right to privacy, and be extremely careful not to give bureaucrats power to pass judgements about people’s lives in ways that are prone to be informed by sexist, racist, and classist biases.

My point is only that, in a liberal society like Australia, many intimate relationships matter, and the government should try as much as possible not to prioritise some relationships over others unless it has a very good rationale for doing so. Ultimately it was this important requirement that saw many commentators object to Victorian premier Dan Andrews’s exclusion of friends from the remit of the COVID bubble in 2020, and why at some point the state of Victoria pivoted to allowing friends to visit each other during lockdown.

A fair alternative to an unfair immigration system?

But short of completely opening our international borders, is there a solution available to the Australian government? As I see it, the federal government can have a broader intimate relationship visa that is available to all citizens and permanent residents at a reasonable fee. Because the number of interested parties will be very high, the government can then combine that visa with a lottery scheme that gives every adult citizen and permanent resident an equal chance to bring someone they care deeply about to Australia.

In response to suggestions that a lottery scheme should be taken seriously, the author of the Scanlon report writes:

“Just like the faint hope that visa processing times will be faster than anticipated, the slim chance of winning a spot in the lottery will leave families banking on dreams, rather than adjusting to the realities of their situation and fully settling in Australia.”

As someone who has parents overseas, I don’t see why this would leave me “banking on dreams”. We all understand how lotteries work, and we all understand that when everyone has an equal interest in accessing a good or opportunity — in this case, reunification with a loved one — but that good or opportunity cannot be provided to everyone, a lottery may be the only fair way to go about it.

Australians have no appetite for open borders, so we need to come up with a fair way to run our migration schemes. In a world full of refugees whose lives are at risk, it is hard to show that an injustice has taken place when adult citizens are prevented from bringing a parent to Australia. At the same time, if some parents will be allowed to join their adult children in Australia on a permanent basis, we better have a fair system that gives all citizens and permanent residents an equal chance to reunite with someone they care deeply about.

This article was originally published by ABC Religion & Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture