It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Tim Soutphommasane 25 NOV 2020

Citizenship isn’t often the stuff of inspiration. We tend to talk about it only when we are thinking of passports, as when migrants take out citizenship and gain new entitlements to travel.

When we do talk about the substance of citizenship, it often veers into legal technicalities or tedium. Think of the debates about section 44 of the Constitution or boring classes about the history of Federation at school. Hardly the stuff that gets the blood pumping.

Yet not everything that’s important is going to be exciting. The idea of citizenship is a critical foundation of a democratic society. To be a citizen is not merely to belong to such a society, and to enjoy certain rights and privileges; it goes beyond the right to have a passport and to cast a vote at an election.

To be a citizen includes certain responsibilities to that society – not least to fellow citizens, and to the common life that we live.

Citizenship, in this sense, involves not just a status. It also involves a practice.

And as with all practices, it can be judged according to a notion of excellence. There is a way to be a citizen or, to be precise, to be a good citizen. Of course, what good or virtuous citizenship must mean naturally invites debate or disagreement. But in my view, it must involve a number of things.

There’s first a certain requirement of political intelligence. A good citizen must possess a certain literacy about their political society, and be prepared to participate in politics and government. This needn’t mean that you can only be a good citizen if you’ve run for an elected office.

But a good citizen isn’t apathetic, or content to be a bystander on public issues. They’re able to take part in debate, and to do so guided by knowledge, reason and fairness. A good citizen is prepared to listen to, and weigh up the evidence. They are able to listen to views they disagree with, even seeing the merit in other views.

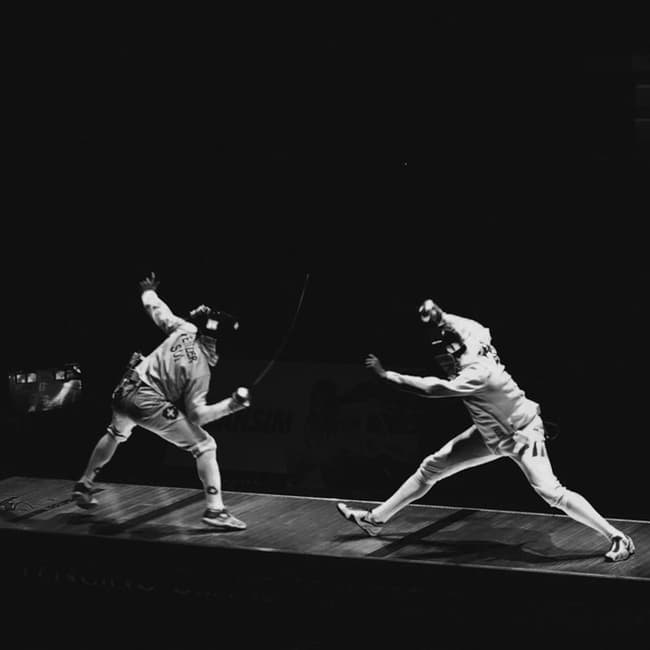

This brings me to the second quality of good citizenship: courage. Citizenship isn’t a cerebral exercise. A good citizen isn’t a bookworm or someone given to consider matters only in the abstract. Rather, a good citizen is prepared to act.

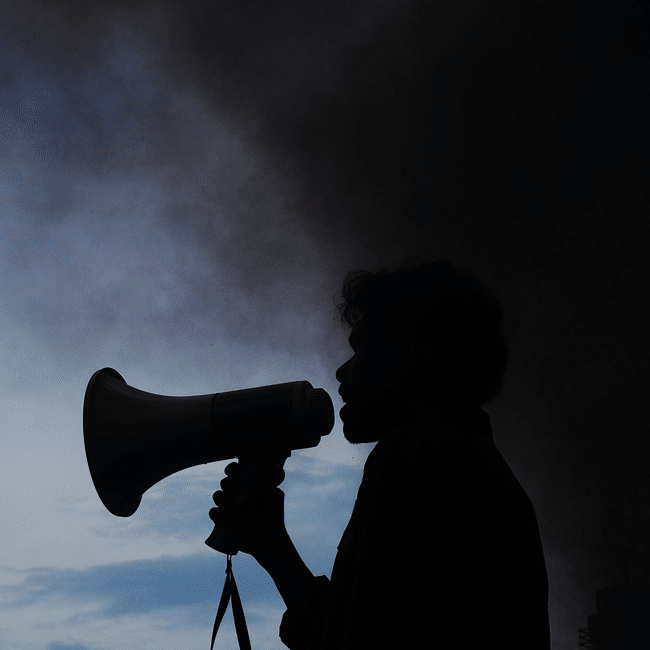

They are willing to speak out on issues, to express their views, and to be part of disagreements. They are willing to speak truth to power and willing to break with received wisdom.

And finally, good citizenship requires commitment. When a good citizen acts, they do so not primarily in order to advance their own interest; they do what they consider is best for the common good.

They are prepared to make some personal sacrifice and to make compromises, if that is what the common good requires. The good citizen is motivated by something like patriotism – a love of country, a loyalty to the community, a desire to make their society a better place.

How attainable is such an ideal of citizenship? Is this picture of citizenship an unrealistic conception?

You’d hope not. But civic virtue of the sort I’ve described has perhaps become more difficult to realise. The conditions of good citizenship are growing more elusive. The rise of disinformation, particularly through social media, has undermined a public debate regulated by reason and conducted with fidelity to the truth.

Tribalism and polarisation have made it more difficult to have civil disagreements, or the courage to cross political divides. With the rise of nationalist populism and white supremacy, patriotism has taken an illiberal overtone that leaves little room for diversity.

And while good citizenship requires practice, it can all too often collapse into curated performance and disguised narcissism: in our digital age, some of us want to give the impression of virtue, rather than exhibit it more truly.

Moreover, good citizenship and good institutions go hand in hand.

Virtue doesn’t emerge from nowhere. It needs to be seen, and it needs to be modeled.

But where are our well-led institutions right now? In just about every arena of society – politics, government, business, the military – institutional culture has become defined by ethical breaches, misconduct and indifference to standards.

And where can we in fact see examples of the common good guiding behaviour and conduct? In a society where public goods have been increasingly privatised, we have perhaps forgotten the meaning of public things. Our language has become economistic, with a need to justify the economic value of all things, as though the dollar were the ultimate measure of worth.

When we do think about the public, we think of what we can extract from it rather than what we can contribute to it.

We’ve stopped being citizens, and have started becoming taxpayers seeking a return. It’s as though we’re in perpetual search of a dividend, as though our tax were a private investment. As one jurist once put it, tax is better understood as the price we pay for civilisation.

But our present moment is a time for us to reset. The public response to COVID-19 has been remarkable precisely because it is one of the few times where we see people doing things that are for the common good. And good citizens, everywhere, are rightly asking what post-pandemic society should look like.

The answers aren’t yet clear, and we all should consider how we shape those answers. It may just be the right time for us to take citizenship seriously again.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conservatism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

BY Tim Soutphommasane

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Bryan Mukandi 25 NOV 2020

The wing of the philosophy department that I occupied during my PhD studies is known as ‘Continental’ philosophy. You see, in Australia, in all but the most progressive institutions, colonial chauvinism so prevails that philosophy is by definition, Western.

A domestic dispute, however, means that most aspiring academic philosophers must choose between the Anglo-American tradition, or the Continental European one. I chose the latter because of what struck me as the suffocating rigidity of the former. Yet while Continental philosophy is slightly more forgiving, it generally demands that one pick a master and devote oneself to the study of the works of this (almost always dead, white, and usually male) person.

I chose for my master a white man of questionable whiteness. Born and raised on African soil, Jacques Derrida was someone who caused discomfort as a thinker in part because of his illegitimate origins. In response, Derrida worked so hard to be accepted that one of the emerging masters of the discipline wrote an approving book about him titled The Purest of Bastards. I, not wanting to undergo this baptism in bleach, ran away into the custody of a Black man, Frantz Fanon.

Born in Martinique, even further in the peripheries of empire than Derrida; a qualified medical practitioner and specialist psychiatrist rather than armchair thinker; and worst of all, someone who cast his lot with anti-colonial fighters – Fanon remains a most impure bastard. My move towards him was therefore a moment of the exercise of what Paul Beatty calls ‘Unmitigated Blackness’ – the refusal to ape and parrot white people despite the knowledge that such refusal, from the point of view of those invested in whiteness, ‘is a seeming unwillingness to succeed’.

It’s not that I didn’t want to succeed. Rather, I found Fanon’s words compelling. The Black, he laments, ought not be faced with the dilemma: ‘whiten yourself or disappear’. I didn’t want to have to put on whiteface each morning. I didn’t want to have to translate myself or my knowledge for the benefit of white comprehension, because that work of translation often disfigures both the work and the translator.

I couldn’t stomach the conflation of white cultural norms with professionalism; the false belief that familiarity with (white) canonical texts amounts to learning, or worse, intelligence; or the assessment of my worth on the basis of my learnt domesticity.

The mistake I made, though, was to assume that moving to the Faculty of Medicine would exempt me from the demand to whiten.

Do you know that sticker, the one you’ll sometimes see on the back of a ute, and often a ute bearing a faux-scrotum at the bottom of the tow bar: “Australia! Love It or Leave It!”? I don’t think that’s a bad summation of the dominant political philosophy in this country. It comes close. Were I to correct the authors of that sticker, I would suggest: “Australia: whiten, or disappear!” This, I think, is the overarching ethos of the country, emanating as much from faux-scrotum laden utes, to philosophy departments, medical institutions, and I suspect board rooms and even the halls of parliament.

What else does, for example, Closing the Gap mean? Doesn’t it boil down to ‘whiten or disappear’, with both reduction to sameness and annihilation constituting paths to statistical equivalence?

I marvel at the ways in which Indigenous organisations manoeuvre the policy, but I suppose First Nations peoples have been manoeuvring genocidal impulses cast in terms of beneficence – ‘bringing Christian enlightenment’, ‘comforting a dying race’, ‘absorption into the only viable community’ – since 1788.

Furthermore, speak privately to Australians from black and brown migrant backgrounds, and ask how many really think the White Australia Policy is a thing of the past. Or just read Helen Ngo’s article on Footscray Primary School’s decision to abolish its Vietnamese bilingual program in favour of an Italian one. As generous as she is, it’s difficult to read the school’s position as anything but the idea that Vietnamese is fine for those with Vietnamese heritage; but at a broader level, for the sake of academic outcomes, linguistic development and cultural enrichment, Italian is the self-evidently superior language.

The difference between the two? One is Asian, while the other is European, where Europe designates a repository into which the desire for superiority is poured, and from which assurance of such is drawn. Alexis Wright says it all far better than I can in The Swan Book.

There sadly prevails in this country the brutal conflation of the acceptance of others into whiteness; with tolerance, openness or even justice.

The Italian-speaking Vietnamese child supposedly attests to ‘our’ inclusivity. Similarly, so long as the visible Muslim woman isn’t (too) veiled, refrains from speaking anything but English in public, and is unflinching throughout the enactment of all things haram (forbidden) – provided that her performance of Islam remains within the bounds of whiteness, she is welcome.

This is why so many the medical students whom I now teach claim to be motivated by the hope of tending to Indigenous, ethnically diverse, differently-abled and poor people. Yet only a small fraction of those same students are genuinely willing to learn how to approach those patients on those patients’ terms, rather than those of a medical establishment steeped in whiteness. To them, the idea of the ‘radical reconfiguration of power’ that Chelsea Bond and David Singh have put forward – that there are life affirming approaches, terms of engagement, even ways of being beyond those conceivable from the horizon of whiteness – is anathema.

Here, we come to the crux of the matter: a radical reconfiguration is called for. Please allow me to be pedantic for a moment. In her Raw Law, Tanganekald and Meintangk Law Professor, Irene Watson, writes about the ‘groundwork’ to be done in order to bring about a more just state of affairs. This is unlike German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Groundwork for a Metaphysics of Morals, by my reading a demonstration of the boundlessness of white presumption and white power, disguised as the exercise of reason. Instead, like African philosopher Omedi Ochieng’s Groundwork for the Practice of a Good Life, but also unlike that text, Watson’s is a call to the labour of excavation, overturning, loosening.

As explained in Asian-Australian philosopher Helen Ngo’s The Habits of Racism, a necessary precondition and outcome of this groundwork – particularly among us settlers, long-standing and more recent, who would upturn others’ lands – is the ongoing labour of ethical, relational reorientation.

Only then, when investment in and satisfaction with whiteness are undermined, can all of us sit together honestly, and begin to work out terms.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

BY Bryan Mukandi

is an academic philosopher with a medical background. He is currently an ARC DECRA Research Fellow working on Seeing the Black Child (DE210101089).

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 25 NOV 2020

This is the moment when I’m finally going to get my Advanced Level Irony Badge. I’m going to write an opinion piece on why we shouldn’t have so many opinions.

I’ve spent the majority of this week digesting the findings from the IDGAF Afghanistan Inquiry Report. I’m still making sense of the scope and scale of what was done, the depth of the harm inflicted on the Afghan victims and their community at large and how Australian warfighters were able to commit and permit crimes of this nature to occur.

My academic expertise is in military ethics, so I’ve got an unfair advantage when it comes to getting a handle on this issue quickly, but still, I was late to the opinion party. Within an hour or so of the report’s publication, opinions abounded on social media about what had happened, why and who was to blame. This, despite the report being over five hundred pages long.

We spend a lot of time today fearing misinformation. We usually think about the kind that’s deliberate – ‘fake news’ – but the virality of opinions, often underinformed, is also damaging and unhelpful. It makes us confuse speed and certainty with clarity and understanding. And in complex cases, it isn’t helpful.

More than this, the proliferation of opinions creates pressure for us to do the same. When everyone else has a strong view on what’s happened, what does it say about us that we don’t?

We live in a time when it’s not enough to know what is happening in the world, we need to have a view on whether that thing is good or bad – and if we can’t have both, we’ll choose opinion over knowledge most times.

It’s bad for us. It makes us miserable and morally immature. It creates a culture in which we’re not encouraged to hold opinions for their value as ways of explaining the world. Instead, their job is to be exchanged – a way of identifying us as a particular kind of person: a thinker.

If you’re someone who spends a lot of time reading media, you’ve probably done this – and seen other people do this. In conversations about an issue of the day, people exchange views on the subject – but most of them aren’t their views. They are the views of someone else.

Some columnist, a Twitter account they follow, what they heard on Waleed Aly’s latest monologue on The Project. And they then trade these views like grown-up Pokémon cards, fighting battles they have no stake in, whose outcome doesn’t matter to them.

This is one of many things the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had in mind when he wrote about the problems with the mass media almost two centuries ago. Kierkegaard, borrowing the phrase “renters of opinion” from fellow philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote that journalism:

“makes people doubly ridiculous. First, by making them believe it is necessary to have an opinion – and this is perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of the matter: one of those unhappy, inoffensive citizens who could have such an easy life, and then the journalist makes him believe it is necessary to have an opinion. And then to rent them an opinion which, despite its inconsistent quality, is nevertheless put on and carried around as an article of necessity.”

What Kierkegaard spotted then is just as true today – the mass media wants us to have opinions. It wants us to be emotional, outraged, moved by what happens. Moreover, the uneasy relationship between social media platforms and media companies makes this worse.

Social media platforms also want us to have strong opinions. They want us to keep sharing content, returning to their site, following moment-by-moment for updates.

Part of the problem, of course, is that so many of these opinions are just bad. For every straight-to-camera monologue, must-read op-ed or ground-breaking 7:30 report, there is a myriad of stuff that doesn’t add anything to our understanding. Not only that, it gets in the way. It exhausts us, overwhelms us and obstructs real understanding, which takes time, information and (usually) expert analysis.

Again, Kierkegaard sees this problem unrolling in his own time. “Everyone today can write a fairly decent article about all and everything; but no one can or will bear the strenuous work of following through a single solitary thought into the most tenuous logical ramifications.”

We just don’t have the patience today to sit with an issue for long enough to resolve it. Before we’ve gotten a proper answer to one issue, the media, the public and everyone else chasing eyes, ears, hearts and minds has moved on to whatever’s next on the List of Things to Care About.

So, if you’re reading the news today and wondering what you should make of it, I release you. You don’t have to have the answers. You can be an excellent citizen and person without needing something interesting to say about everything.

If you find yourself in a conversation with your colleagues, mates or even your kids, you don’t need to have the answers. Sometimes, a good question will do more to help you both work out what you do and don’t know.

This is not an argument to stop caring about the world around us. Instead, it’s an argument to suggest that we need to rethink the way we’ve connected caring about something with having an opinion about something.

Caring about a person, or a community means entering into a relationship with them that enables them to flourish. When we look at the way our fast-paced media engages with people – reducing a woman, daughter, friend and victim of a crime to her profession, for instance – it’s not obvious this is making us care. It’s selling us a watered-down version of care that frees us of the responsibility to do anything other than feel.

Of course, this is possible. Journalistic interventions, powerful opinion-driven content and social media movements can – and have – made meaningful change in society. They have made people care.

I wonder if those moments are striking precisely because they are infrequent. By making opinions part of our social and economic capital, we’ve increased the frequency with which we’re told to have them, but alongside everything else, it might have diluted their power to do anything significant.

This article was first published on 21 August, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 SEP 2020

At TEC, we firmly believe ethics is a team sport. It’s a conversation about how we should act, live, treat others and be treated in return.

That means we need a range of people participating in the conversation. That’s why last year, we asked for funding support to bring another philosopher into our team. Thanks to our donors, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Eleanor Gordon-Smith as a Fellow. Already established as one of Australia’s leading young thinkers, Eleanor is a published author, broadcaster and in demand speaker. She’s also currently reading for her PHD at Princeton University. To welcome her on board and introduce her to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat with her.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

I remember sitting in my first philosophy class and feeling like this was what thinking should really be like. I left knowing less than I thought I did when I arrived – all my other classes were about the legislative agenda around human rights and my philosophy class said wait, what’s a right and what counts as human? I loved the ability to ask those questions and from that day on it’s always felt like that’s where the real action is: the deep questions that we too easily take for granted.

Do you specialise in a key area or areas?

I cross-specialise in ethics, language, and epistemology [the study of knowledge]. In all three areas I am interested in the powers we can only have because we are social creatures. I work on moral powers that we can only exercise in social settings – such as consent, and promise – how linguistic meaning can be constructed and destroyed by social relationships, and how being embedded in societies can facilitate or disrupt our processes of gaining knowledge. The uniting theme across my work is that we depend on each other for many of our most important abilities and powers, such as speaking, learning, or coming up with moral frameworks, and yet a lot of the time other people are very bad. So what are we to do, if we rely on each other for our most foundational abilities but frequently “each other” is the source of our problems? So far I only have the question. But that’s where all good philosophy starts…

Sounds like a phenomenal place to start. Now let’s have a fan-girl moment. Who is your favourite philosopher?

There are too many to name but Rae Langton, who spent a lot of time in Australia, is a huge inspiration for me, and I like to think about how to precissify Robert Adams’ remark which seems to me to get to the heart of moral philosophy: “we ought, in general, to be treated better than we deserve”.

Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions, the impact these are having on our lives, our interactions, how we work and so on. What do you hope we learn or gain from this experience?

Truthfully I think the most we can hope for is a greater appreciation for the profound fragility of the things that normally keep us functioning. Our friendships, entertainment, ways of being in the world, all so easily threatened by simply not being able to leave the house very much. I have found that very humbling, and very difficult. I hope also we can learn to be a little more compassionate with ourselves about the fact that we are all creatures who need to live and will one day die. Before Covid, it was very easy to see each other and ourselves as our jobs, or athletic achievements, or how we’re measuring up to a set of criteria about how our lives “should” be going. Seeing everybody’s houses and children and needs via Zoom will I hope let us be compassionate about the fact that we all have them, and there’s no shame in taking care of them.

We’ve all had a guilty pleasure of sorts during the pandemic. Can you share with us yours?

I bought a robot vacuum cleaner and I like to follow him around and tell him he’s missed a spot.

Amazing. Let’s get to know you better. What is a standard day in your life?

I read a lot, work on [podcast] episode plans, put several thousand post-it notes on the wall – each one a piece of tape from an interview, a fact, a piece of theory, a well-phrased, or a scene – and rearrange them until I can see a story unfolding alongside a philosophical idea. I read philosophy, listen to a lot of radio and podcasts because there are so many clever people in that sphere whose work I admire, and try to stop by 9pm. Although if I’m honest, that’s rare these days.

You wrote a book – what is it about?

Stop Being Reasonable. It’s a series of true stories about how we change our minds in high-stakes moments and how rarely that measures up to our ideal of rationality. Each chapter features interviews I conducted with someone about a moment in their life that they changed their mind in a really drastic way: a man who left a cult, a woman who questioned her own memory of being abused, a man who changed his mind about his entire personality after appearing on reality TV, someone who learned their family wasn’t really their family, and so on. Each story highlights a sometimes-maligned strategy for reasoning that many of us turn out to use all the time, especially when it really matters: believing other people, trusting our gut, thinking emotionally, and so on. The book is a plea for a more capacious ideal of rationality, such that these things ‘count’ as rational thinking as well as the emotionless first-principles reasoning we usually associate with that term.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

People sometimes think ethical thinking promises a set of answers. It might, but I think it’s much more about learning to ask a different set of questions. So many of our disagreements and deepest divisions are built on argumentative frameworks that we almost never dredge to the surface and examine. We take things for granted about what matters, why, how to measure it, and what follows from the fact that those things matter. Learning to think ethically is about examining those things – about realising which systems of value we subscribe to by accident, and trying to make our value systems more deliberate.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The art of appropriation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 SEP 2020

What underlying driver created the great toilet paper gate panic of 2020?

At the onset of the pandemic, The Ethics Centre Fellow, Dr Matt Beard, University of Queensland philosopher and health researcher Bryan Mukandi, University of Queensland, and Australian philosopher and Princeton PhD candidate Eleanor Gordon-Smith joined in conversation. Together they discussed, dissected and explored a range of ethical issues rising during the early stages of the pandemic. In this extract, they discuss what COVID panic buying reflects about who we are, and what we value..

Matt Beard, TEC Fellow:

The kind of panic buying responsive that we saw from ordinary people at the beginning of this, what did that tell us about ourselves? For me that was a moment to really reckon and say what does it tell us that in the first sniff of a crisis, the first thing that we did was take care of us and ours. What does that say to us about the way in which we’ve set up this society?

Eleanor Gordon Smith, Philosopher:

The United States, the land that brought us Black Friday sales, did not hold back when it came to panic buying. What did it reveal about us? Less I think then it revealed about our circumstance.

Here’s what I think it revealed about us. We were afraid, and we didn’t feel secure, and we didn’t trust either us or the government around us to provide for us in the moment of crises where we would most need both those things.

More than anything particularly deep about our innate nature, which I know people argue about a lot, does this reveal that we’re fundamentally selfish? Well yes, but then people also drove themselves to food banks, and it revealed other things about kindness and solidarity, and all the nice things as well.

I think more than that it revealed something that we kind of already know, which is that the right configuration of circumstances can push ordinary people to behave in profoundly selfish and possibly evil ways.

We know that a lot of exercises of bad behaviour are perfectly ordinary, and what happens when people are frightened and insecure. More than what I think it told us about us, I think it told us something really disquieting about the faith that we had in our systems, which was that unless we did this unless we went out and kind of did this end of days, treading on each other’s necks for a can of beans we wouldn’t have enough.

I’ve been saying this for weeks, I don’t even like beans, I don’t know why I bought so many beans, everyone just transformed into people who really liked beans all of a sudden. But it told us that we were willing to do that.

In fact, we thought it is necessary that we do that because we were so unsure of the fact that other people, and or the government, and or the system would be able to provide for us if we didn’t do this kind of absurd others sacrificing thing. I think we were entirely wrong.

Byran Mukandi, Philosopher:

Here I disagree with Eleanor. Irene Watson, a legal scholar, in her book, “Raw Law”, she uses a Nunga word, Muldarbi for colonialism. There’s an image she paints of colonialism as this voracious monster, this voracious animal that just devours and consumes. And I just find that so incredibly apt.

I think it’s telling that for some groups in Australia, the relationship between ‘mainstream society’, and some communities is one that’s best classed as this voracious, consuming animal. This devouring thing.

As a sub-Saharan African, the quality of life I enjoy today as an Australian citizen, is inextricably linked to the poverty and deprivation, and the suffering that a lot continent sub-Saharan Africans, and a whole bunch of people around the world experience. Those two things are intimately intertwined.

There’s a lot of posturing in terms of our response to climate crisis around why China needs to do something first, but the fact is the Chinese industrial work, manufacturing work, goes into providing that which we, in the Western world, consume. There’s a sense in which we are ferocious, we devour.

The rush to buy toilet paper as though when the zombie apocalypse comes, the most needful thing is toilet paper… I mean, this isn’t a gastroenteric virus, it’s not like everybody’s going to be on the toilet, but little things, baking powder, toilet paper, tins of tomatoes and tomato paste, people were hoarding and panic buying non-essential goods.

I don’t think it was because the idea was this non-essential good is going to run out and I’m not going to make brownies or cupcakes, or whatever, and my life is going to come to an end.

I think we have a voracious appetite, I think we have a voracious consuming, devouring appetite. I think we have a particular relationship to the environment and to others, and I think this pandemic has just shone a light on who we are, as opposed to who we like to pretend we are and the image of ourselves we like to project.

This is an extract from a live-streamed event. Watch the full conversation from FODI Digital event, Ethics of the Pandemic, below. Don’t miss our next live-stream events at www.festivalofdangerousideas.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 9 SEP 2020

In the pandemic landscape, individual rights were challenged against a mutuality of care for our neighbours.

At the onset of the pandemic, The Ethics Centre Fellow, Dr Matt Beard, University of Queensland philosopher and health researcher Bryan Mukandi, University of Queensland, and Australian philosopher and Princeton PhD candidate Eleanor Gordon-Smith joined in conversation.

Together they discussed, dissected and explored a range of ethical issues rising during the early stages of the pandemic. This extract from the discussion considers Carol Gilligan’s theory around the ethics of care, and in particular her ideas around the mutuality of care and the idea that individual actions impact the whole.

Matt Beard, TEC Fellow:

One of the things that I keep coming back to, is this quote from the feminist philosopher, Carol Gilligan, who championed an approach, “the ethics of care”. She talks about this idea that we live on a trampoline, and whenever we move it kind of affects everybody else in the same way, it makes other people wobble, your activities cause discomfort to others.

And one of the things that this pandemic has crystallized for me is this sense that, this whole idea of this atomized individual with rights that cluster them off and divide us from other people, is kind of illusory. We are radically dependent on other people, we have this interdependence and these mutual obligations that inform our moral response.

And that got me thinking about how difficult it can be to muster that sense of mutual obligation. In a society that does just talk so heavily about ourselves as individuals, we’ve been conditioned to think about ourselves in almost exactly the opposite way to the way that this response requires us.

Have I set this up in the right way? Is it true we’ve been conditioned in this way? How do you think about this?

Bryan Mukandi, Philosopher:

It’s really complex, because on the one hand I think you’re absolutely right. I love that metaphor of the trampoline, and I completely agree, this idea of this autonomous free liberal individual, it just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. But at the same time, on the other hand, the fractiousness and fracturedness we’re witnessing in the US applies here too, in some really interesting ways, right.

So, yes, we’re all on this trampoline, but the real estate that you occupy on that trampoline makes the world of difference. And we have a kind of social structure, social organisation where there’s an investment in occupying good real estate [so] that when something happens – a natural disaster, a fire, floods, a pandemic – there’s an investment in being in a position of being able to enact something like that illusory autonomy.

I think about Martin Luther King’s idea of an inextricable “network of mutuality”. But he raises this in a sort of moment where African Americans are in a particular kind of relationship with white America. He acknowledges that there’s this mutuality, there’s this connection, but the nature of this connection is one that’s really detrimental to some groups of people as opposed to others.

And I also think about Frantz Fanon contribution to Hegel’s dialectic of recognition. This idea that our selfhood emerges in relationship with others, it’s like it falls apart in the colony because in the colony the white doesn’t want the colonized recognition, they want their labour.

So I think, while on the one hand, COVID has shown us that this ideal of autonomy – it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. It’s in really interesting ways though, I think it may, at least for some groups of people, legitimate this project of striving towards that kind of autonomy of occupying the best possible real estate on that trampoline, as opposed to reconfiguring the trampoline itself.

Eleanor Gordon Smith, Philosopher:

It’s a really good question.

And like Bryan, I think it’s a very complex one and one that we’re not going to compress either now or in a pandemic writ large. One thing I think that is kind of a shame for me living in the states and seeing the way the states is covered internationally is the way that a lot of the pressure to reopen is construed in these kinds of individual autonomous terms.

I have a lot of family and a lot of friends who I think are really genuinely very concerned about my proximity to New York at the moment. They feel like crisis, real proper, ‘everyone’s dead’ crisis, like blood –in–the–streets–type crisis, is right around the corner.

And my suspicion about why they feel like that is that they’ve seen these videos of women hanging out of cars at intersections blowing the horn at medical workers or protesters walking into government buildings, people with the American flag painted on their face, holding banners about the right to return to work.

These people are both, they’re a very individualistic face of this movement and the movement that they claim to be espousing is very individualistic. They’re making claims about people’s individual rights to get back to work and they are doing so claiming to speak as individuals.

But one of the things that I think it’s a shame that [coverage] obscures is that the pressure to reopen America comes from the fact that it’s a non-accidental feature of the US American system and the US economic system that it wants people to be back at work more than it wants them to be safe and well.

We encounter that from the mouths of individuals who present themselves as autonomous in saying things like ‘the cure cannot be worse than the disease’, but the pressure isn’t just from rhetoric or from individuals, it’s from the way the system is set up.

You look at the kinds of costs and debts that Americans incur just for functioning. Like if you get sick, that costs money and that creates debt, if you have a higher education system, even one that is continuing on Zoom at the moment, that costs money and that causes debt.

Both of these things coupled with just the usual systems of credit means that most Americans are in eye–watering amounts of debt, and then debt has interest which means that you’re incentivized to get back to work as fast as possible and you put people in a position where it’s not only rational but critical to get back to earning money because it costs money to earn less.

The way the system functions is such that not only do you create all these pressures, it’s then coupled with this narrative of individualism, telling people that both the source of the problem and the nearest solution is to be conceived of in these individualistic autonomous senses.

It’s a real shame when we reinforce and circulate these images of Americans protesting in the way that they are right now, because we obscure the fact that even these apparently maniacally individual faces are in fact the product of the same system that crushes the rest of us.

This is an extract from a live-streamed event. Watch the full conversation from FODI Digital event, Ethics of the Pandemic, below. Don’t miss our next live-stream events at www.festivalofdangerousideas.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 25 AUG 2020

It can be argued that life isn’t something we have, it’s something we do.

It is a set of activities that we can fuse with meaning. There doesn’t seem much value to living if all we do with it is exist. More is demanded of us.

One of my favourite quotes about living comes from French Philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau.

“To live is not to breathe but to act. It is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence. The man who has lived the most is not he who has counted the most years but he who has most felt life. Men have been buried at one hundred who have died at their birth.”

Rousseau’s quote isn’t just sage; it’s inspiring. It makes us want to live better – more fully. It captures an idea that moral philosophers have been exploring for thousands of years: what it means to ‘live well’ – to have a life worth living.

Unfortunately, it also illustrates a bigger problem. Because we tend to interpret Rousseau’s guide to ‘Really Good Living’ in a particularly narrow way – that it’s all about vitality, seizing the day and YOLO.

This is a reality that professionals working in the aged care sector should know all too well. They work directly with people who don’t have full use of their organs, their faculties or their senses.

Months ago, before the pandemic, I presented Rousseau’s thoughts to a room full of aged care professionals. They felt the same inspiration and agreement that I felt.

That’s a problem.

If the good life looks like a robust, activity-filled life, what does that tell us about the possibility for the elderly to live well? And if we don’t believe that the elderly can live well, what does that mean for aged care?

The findings from the recent Aged Care Royal Commission reveal galling evidence of misconduct, negligence and at times outright abuse. The most vulnerable members of our communities, and our families, have been subject to mistreatment due in part to a commercial drive to increase the profitability of aged care facilities at the expense of person-centred care.

More recently, we have seen aged care at the centre of the Covid-19 pandemic. Over 250 deaths have been recorded in facilities across Australia from the virus and our State and Federal governments are fighting out responsibility.

Elderly residents have been prevented from being treated in hospitals, their facilities have been drastically understaffed and public commentators have wondered whether we ought simply to allow more of them to die.

Absent from the discussion thus far has been the question of ‘the good life’. That’s understandable given the range of much more immediate and serious concerns facing the aged care sector, but it is one that cannot be ignored, despite the urgent matters before us.

Whilst leaders and decision-makers must be held accountable, there is a deeper sense of shared responsibility we should all carry when it comes to our attitudes toward ageing and aged care.

In 2015, celebrity chef and aged care advocate Maggie Beer told The Ethics Centre that she wanted “to create a sense of outrage about [elderly people] who are merely existing”. Since then she has gone on to provide evidence to the Royal Commission because she believes that food is about so much more than nutrition. It’s about memory, community, pleasure and taking care and pride in your work.

Consider the evidence given around food standards in aged care. There have been suggestions that uneaten food is being collected and reused in the kitchens for the next meal; that there is a “race to the bottom” to cut costs of meals at the expense of quality, and that the retailers selling to aged care facilities wildly inflate their prices. The result? Bad food for premium prices.

We should be disturbed by this. This food doesn’t even permit people to exist, let alone flourish. It leaves them wasting away, undernourished. It’s abhorrent. But what should be the appropriate standard for food within aged care? How should we determine what’s acceptable? Do we need food that is merely nutritious and of an acceptable standard, or does it need to do more than that?

Answering that question requires us to confront an underlying question: Do we believe aged care is simply about providing people’s basic needs until they eventually die?

Or is it much more than that? Is it about ensuring that every remaining moment of life provides the “sentiment of existence” that Rousseau was concerned with?

When you look at the testimony provided to the Aged Care Royal Commission, a clear answer begins to emerge. Alongside terms like ‘rights’, ‘harms’ and ‘fairness’ –which capture the bare minimum of ethical treatment for other people – appear words such as ‘empathy’, ‘love’ and ‘connection’.

These words capture more than basic respect for persons, they capture a higher standard of how we should relate to other people. They’re compassionate words. People are expressing a demand not just for the elderly to be cared for but to be cared about.

Counsel assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Gray QC, recently told the commission that “a philosophical shift is required, placing the people receiving care at the centre of quality and safety regulation. This means a new system, empowering them and respecting their rights.”

It’s clear that a philosophical shift is necessary. However, I would argue that what’s not clear is if ‘person-centred care’ is enough. There is an ageist belief embedded within our society that all of the things that make life worth living are unavailable to the elderly.

As long as we accept that to be true, we’ll be satisfied providing a level of care that simply avoids harm, rather than one that provides for a rich, meaningful and satisfying life.

Unless we are able to confront the underlying social belief that at a certain age, all that remains for you in life is to die, we won’t be able to provide the kind of empowerment you felt reading Rousseau at the start of this article.

What it will do is provide a better version of what we already believe – that once you are at a certain age and stage of life, ‘living’ is no longer a real option? You must settle for existing.

At this stage, we can pump you full of our care, love, empathy and respect – and most people accept that we should do that – but you are no longer living for yourself. You are waiting, as humanely as possible, to die.

Unless we confront this deeper belief, any positive movement in aged care will struggle to provide residents with what we all hope for – a life worth living.

*This is an edited version of an article first published on 10th September 2019

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What's the use in trying?

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2020

In early 2020 I sat in a friend’s house on the coast of New South Wales listening to smoke alarms go off in canon, triggered by the air itself, thick with smoke from the active fronts of the worst bushfire season in living memory.

The roads were lined with scorched animals and the climate crisis seemed as inevitable as it did cataclysmic. It was unthinkable then that this moment of apparently superlative awfulness would, in a matter of months, recede to just one more entry in a year-long list of suffering, death, and massive-scale crisis.

The lucky of us stayed inside afraid for months. The unlucky died, or lost loved ones and could not go to their funerals. There was widespread and systematic police violence against black people and against the people who protested it. USD $3.6 trillion was wiped off the stock market in one week.

The first six months of 2020 presented an unusually literal illustration of an old ethical question: why bother when the conclusion feels foregone?

What many of us felt about the climate in January was a well-known phenomenon: the fatigue of feeling useless when we felt we could not rely on the powerful to make changes or on other people to do their part. This feeling was quickly matched by parallels in resistance to systemic racism, in fighting an economic downturn and even in pandemic compliance.

Early on in the COVID-19 outbreak, data modelling revealed that social distancing would only work if 8 out of 10 of us followed the rules. If only 70% of us stood six feet apart, washed our hands, and stayed inside for weeks on end, it would be as though none of us had. To the misanthropist who felt that 30% of people would surely disregard the rules, a motivational gap loomed: why do what I can to help, when I’m not confident it will.

Even to the most resiliently motivated, parts of 2020 posed this problem. Hundred-thousand strong protests in the United States were not enough to prevent the deaths of more unarmed black people, nor to prevent protestors themselves from being pepper-sprayed at close range.

The indefatigability of the protests seemed met by the indefatigability of the problem. For many people it became impossible to feel calm or ordered anywhere as long as case numbers rose. So it seemed foregone that our homes would not feel calm or ordered either, and the motivation to improve them frayed in proportion to the dishes in the sink.

The philosopher and psychologist William James knew that certain beliefs can be self-validating; that confidence in outcomes, however, we come by it, can make itself well placed. The sailors who think they can pull the heavy rope are more likely to summon the gusto and collective coordination required to make it the case that they can. This first half of 2020 was a vivid illustration of the photonegative; the fact that uncertainty about outcomes can be enough to puncture our drive to pursue them.

So what is there to be done? Few of us believe that this pessimism or uncertainty in fact means that it is not worth protesting, or washing our hands, or doing the dishes. We still rationally endorse that we ought to do these things. But it becomes a wrench, an act of shepherding ourselves, parent-like, and it wears us down. It leads us to misanthropy.

An answer lies in looking more closely at one facet of what 2020 has cost us. We lost the most unthinking parts of our lives; the well-worn routine of the drive home or the setup at the gym, the clockwork Wednesday night choir, the disappearance into a team practicing a physical skill.

These were moments where what we did was not to achieve, or to think, but to be in a process. It was immaterial to us whether we achieved victory or even improvement, since our commitment to doing them was not dependent on whether we did. What we wanted was to be absorbed, to be a creature who acts.

We are, unavoidably, creatures who act. But as philosopher Mark Schroeder has noted, there is an asymmetry between our options in thought and our options in action. We have three options about what to think: we can believe what is on offer, reject it, or withhold judgement. But in action we have only two options; act or do not. There is no way to be in the world that avoids this two-prong choice.

When we realize this, we can shift our focus in a way that avoids futility fatigue. Our moral duty to act – and so too, our motivation – need not be entirely derived from what will happen once we do. It may be that what we owe each other is action itself, and effort itself.

In turn, this can release us from some pressure that comes with knowing that our goals will be difficult to achieve and fragile once we get them. We can simply aim at the action itself. We can find in resistance, in participation, and in care, a goal which is not about the altering of the world but about the observation of the act itself.

In this state, our uncertainty is no longer a threat to our motivation. With this as our focus and our source of energy, we may find that we are, in the end, more effective at altering the world.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Whose home, and who’s home?

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2020

Australian citizens who live overseas and want to return to Australia, with some exceptions, now have to pay for their mandatory two-week hotel quarantine.

This new rule applies for those returning to New South Wales or Queensland. It means that a single adult returning home must have AUD $3000 to pay for their stay. Last week New Zealand announced a similar policy: citizens returning home to stay less than 90 days will be charged for their quarantine.

Announcing the policy, NSW Premier Gladys Berijiklian said “Australian residents have been given plenty of time to return home, and we feel it is only fair that they cover some of the costs of their hotel accommodation”.

The locution of having “been given” time to return home sounded curious to many of us who reside overseas. We were unaware that living elsewhere had been a matter of taking.

In the comments sections of news articles about the announcement, the Premier’s sentiment was echoed by other Australians. A recurring theme appeared: overseas Australians who returned home now are being selfish to expect taxpayer help

What could fairness require, in a pandemic? It is not fair that some people will get COVID and others will not. It is not fair that some will die while others survive. These are circumstances where a question about fairness is simply not askable; there is only tragedy, which does not have a possible equitable distribution.

One way to be unfair in a pandemic might be to expose other people to risk. People arriving from overseas certainly do that, and it is crucial to Australia’s efforts to contain the coronavirus that it curbs the risk from international travellers. Like many other countries, Australia was within its rights to close its borders early to international travellers in recognition of this risk.

The very concept of citizenship, however, prohibits closing borders entirely. No matter where citizens ordinarily live, their government has a duty to allow them to cross the border of their home. This is what it means to be a citizen.

There is a problem of incommensurability here. How does the need to mitigate a biothreat weigh against the standing rights of citizens to cross a border? One is a value of rights and obligations; the other is a value of consequences and threat reduction. Neither of these values presents itself in a standardised unit to be compared against the other.

The question is not quite “how do we make a good decision?” but “which kind of good should we be interested in?”. This is a fairly common problem.

Not all of the things we want governments to provide can be coherently measured against each other, so when they come into conflict, it’s not clear how to even begin making the trade. Privacy against safety, health against freedom, service provision against non-interference.

The Government appears to have chosen fairness as the value to adjudicate between the two. The Premier described the policy as “only fair”, since “Aussies overseas have had three or four months to figure out what they want to do”. Prime Minister Scott Morrison echoed this, saying overseas Australians “obviously delayed [their] decision”, and Winston Peters of the New Zealand First Party said that asking taxpayers to pay for fellow citizens’ quarantine was “grossly unfair”.

There are two features of the decision that challenge the terms of fairness here. One is that it seems only to apply to Australians overseas. We would not, for instance, describe it as “only fair” to deny Medicare coverage to an Australian at home who contracted COVID-19 after breaking quarantine rules, even though there is an argument that this is ‘only fair’. Like the quarantine fee, it would mean that those who had ‘plenty of time’ to follow the rules did not impose a burden on the taxpayer when an emergency befell them.

The second is that it is not clear that fairness is the value we should default to in the midst of a global pandemic. In an article for Guardian New Zealand, Elle Hunt suggested that these policies are a failure of empathy. “Discriminating against all but the most wealthy members of the diaspora is a rare failure of not just compassion but imagination – to reach a more equal solution, and to imagine the painful personal circumstances in which it might be warranted.”

Empathy asks different things of a government than fairness. It asks for mercy and the maximum provision of services to those who are suffering. It asks for an imaginative capaciousness about what life is like for citizens whose jobs, families, friends and visas would have been in peril if they had returned earlier. It asks for magnanimity, forgiveness, and generosity.

Empathy may not be a viable long term guiding principle for a political party. But in a pandemic, we may find that the alternative language of fairness and moralising either loses its footing entirely or forces us to absurd conclusions.

“Only fair” was how the Premier described the policy, but we have more values than only fairness. A global emergency may be the time to use some.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 6 AUG 2020

As Melbourne goes into the most intense lockdown measures we’ve seen during the Covid-19 pandemic, activity in the state grinds to a halt.

In media outlets around the country, contrarian commentators are running pell-mell to explain why the lockdowns are the wrong move, and why we should be hastening to open the economy, even if it means paying a price in lives.

Others have been sprinting at a similar speed to disprove them – perhaps moving too fast, and in so doing so, having the argument on their terms.

Consider two of the loudest critics of the purpose of the lockdown: UNSW Economics professor Gigi Forster and Adam Creighton, economics editor at the Australian newspaper. Forster has argued that the costs – measured in terms of overall wellbeing – are more greatly increased by our response to Covid-19 than by the virus itself.

Creighton’s arguments are related, though he has emphasised more the difference between quantity and quality of life. On the lockdowns in Melbourne, he recently tweeted “What’s the point in being alive if you can’t live?

Shameful what’s occurring in Victoria.

Effective dictatorship declared.

Devastating, destructive power of the state on full display.

Respect for the individual clearly irrelevant.

What’s the point in being alive if you can’t live?— Adam Creighton (@Adam_Creighton) August 2, 2020

Perhaps the loudest response to each of them has been to say that a successful economic exit from the COVID-19 pandemic relies on successfully controlling the virus through measures like lockdowns, social distancing and so on. Even on economic terms, it won’t work to allow the virus to run through the community. We can’t come back economically unless we succeed medically. It’s not a zero-sum game.

I’m not the right person to decide whether or not that argument is correct. But that’s not my primary concern either. Instead, my concern is that in arguing the facts on this particular issue – that economically we are better off by controlling the spread of the virus – we have granted them their first principle. Namely, that the correct course of action is whichever one makes the most sense economically and does the most work to maximise quality of life for the largest number of people.

In granting this principle, we’re rushing over a lot of controversial territory. For instance, we might want to take issue with Creighton’s argument on other grounds – that whilst it is important to be able to live fully, in order to so, we need to be alive. The idea that ‘life is for living’ only makes sense if we also say that some people shouldn’t be permitted to stay alive. And many people won’t want to say that.

The point is, the ‘maximise wellbeing’ argument implies a harsh form of utilitarianism. It suggests we accept that there are some people who will have to pay the price for our flourishing.

Maximising benefit still leaves some people to suffer. Usually, it means leaving the same people who have suffered before to suffer again. After all, the most vulnerable already have a low quality of life, so if they end up dying, statistically speaking, it doesn’t show up as much of a loss.

When we encounter arguments like those of Creighton and Forster, we have a choice to make: what matters most to us? Is our primary concern making as many people as possible as well off as we can? Or do we to stand in solidarity with those who are worst off, and refuse to flourish at their expense?

There are schools of thought and philosophers and arguments that will give you cover whichever way you make that choice. But it is a choice to be made. We can’t just interrogate the conclusions of these arguments, we need to question their starting (and often hidden) premises.

During this pandemic we have started to see some of the hidden premises bubble to the surface. Overwhelmingly, the result has been a discomfort at the idea that we get to decide who we are willing to sacrifice for our collective benefit.

I hope that’s an idea that we remember. Because that’s not a problem that started with COVID-19. Instead, it’s a trade-off that is hard–wired into our economic system. In many ways, it’s perfectly logical to suggest we let more people die from Covid-19 if it means we all benefit. After all, it’s what we’ve always done.

We need to recognise that it’s not just people who champion beliefs and values. It’s the very systems that inform and shape our world.

If we don’t want our collective benefit to be paid for by those who most need our care, we need to do more than debate the people floating this idea. We must interrogate the system that gave rise to those views at all. We need to recognise the ways in which it is our default setting and find the courage to imagine another way of doing things.

It’s often said there are no atheists in the foxholes. It feels like there are also few nihilists in a crisis. Circumstances like these sharpen our moral intuitions and surface underlying tensions in society.

Our responsibility, as well as getting through this and getting each other through this, is to ensure that in times of comfort we retain that ethical sharpness and continue to refuse to flourish when that requires others to fail.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships