How to pick a good friend

How to pick a good friend

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil The Ethics Centre 17 JUL 2018

Fed up with fair weather friends? A bit of ethical reflection will help you figure out which friends to pick – and keep.

It takes very little to make a “friend”.

A bit of spark, some solid banter. A vulnerable confession or two. Sharing the same floor, class, or gym helps lower the stakes even more. This happy conversation: “You’re getting a coffee now? Me too!” Spells the chorus cheer of a budding friendship. Any more than that and phew – let’s not force something that’s meant to be easy!

But is that true? Is effort really the death knell? Stick around in any friendship, and you will find the coveted ease ebbing away. Illness, death, divorce, bankruptcy… Mother Time has a funny way of revealing the friends who will stick by you no matter what, and the friends who will leave at first pinch.

In a 2016 survey conducted by Lifeline with over 3100 respondents, 60 percent of Australians confessed to feeling lonely on a regular basis. A large portion of these people live with a spouse or partner. The stats show its quality we need, not quantity.

Shasta Nelson, author of Frientimacy, argues the loneliness many of us feel isn’t because we don’t know enough people. Instead, it’s because we don’t feel known, supported, and loved by the right few.

How do we find this right few? Ethical reflection can help.

Friendship values

When do you feel loved? And how do you show love?

These questions can help reveal our friendship ‘values’. Knowing which of these we prioritise is key to discerning which of our friendships are valuable and worth investing effort in. Do you feel most loved when you’re accepted unconditionally? When you’re having a good laugh? What about when your achievements are celebrated and encouraged? Or when your ideas are challenged in a lively debate? None of these are mutually exclusive but being clear about what you value makes it easier to decide if this friendship is one to prioritise.

You may think the second question redundant but knowing how we express love can help bring out the subconscious values that drive our behaviour. We each have patterns of love or dependency that are formed in childhood. Knowing what they are helps you be more aware of the ones you naturally tend to lean into, and if those are ones you want to cultivate. As much as we like to believe we naturally gravitate to what’s good for us, we might be more likely to gravitate to what’s familiar.

You might show love by being financially generous, hospitable, or a shoulder for someone to cry on. You might value having shared interests and vibrant conversations or being their emergency contact in a crisis. Maybe you show your love and comfort around someone by letting your hair down and complaining a lot. Hey, it happens.

How to create deeper friendships

Choosing the right types of people as friends can help us cultivate relationships based on shared values and character, not circumstance. And when we have them, let’s treat them well. Nelson’s three principles for deepening an already existing friendship are:

- Positivity: helping each other feel good. Think smiles, laughter, empathy, and validation.

- Consistency: a bank of expected behaviour that builds trust; the opposite of walking on eggshells around someone.

- Vulnerability: sharing the bad and the good.

A friend is one with whom we are willing to share, without fear of judgement, our truest self. It’s worth being picky about.

Next month, we’ll be talking about how to end a friendship – ethically. If you can’t wait that long, Ethi-call can help, our free helpline for life’s ethical struggles. Book your appointment here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Gordon Young The Ethics Centre 14 JUL 2018

One of the more disturbing trends to emerge in public discourse recently has been the idea that we live in a ‘post-truth’ era.

While the phrase has most often been used in reference to President Trump’s frequent and shameless self-contradictions, it is also reflected in other debates. The anti-vaccination movement’s rejection of medical science, increasing distrust of the media, the success of political nihilism, as pioneered by 4-Chan, and the Flat-Earth theorists.

All of these movements reflect a growing idea: truth is simply a matter of opinion. The field of philosophy that deals with such foundational questions is metaphysics. It holds the honour of being both the most important, and most utterly infuriating pursuit one can engage in. On the one hand, metaphysics provides the foundation for all subsequent philosophy and ethics. On the other, it posits questions that are impossible to answer without being an omniscient deity.

But just because metaphysics cannot provide certainty, doesn’t mean it cannot provide conclusions. And in an age where “Well, that’s just your opinion” is considered a legitimate rebuttal, I feel that now is a good time to review a few popular myths of metaphysics:

Nihilism means I can do what I want

It should come as no surprise that post-truth enthusiasts have taken to the concept of Nihilism – or at least a simplified form of it. They argue that since life has no demonstrable ‘purpose’ everything we do is pointless. Ergo, if there’s no grand point to life, our actions are meaningless and we can all do whatever we want.

Nihilism is a serious philosophical theory worthy of deep consideration. It is also fairly easily debunked by slapping its proponents across the face. Life may or may not have a ‘purpose’, but the idea that such a vacuum would single-handedly annihilate the value of ethics blatantly ignores the very tangible existence of consequences.

All rules are constructs, therefore all rules are false

Any thorough analysis of a deontological system of ethics will quickly find exceptions. Since the value of a rule-based approach depends on our ability to rely on those rules, it is both intuitive and compelling to suggest that since all rules are social constructs, none hold inherent meaning.

But the conclusion that follows from this argument would agree that science is wholly void because it doesn’t yet offer us a perfect understanding of the universe. While rules-based approaches will inevitably be flawed to some degree, their ability to provide external accountability makes them invaluable ethical tools. They should be judged according to their merit, not their nature.

A lack of definitive proof makes your position false

Metaphysics is uncertain by nature. Questions like the nature of reality, for instance, cannot be answered while we are simultaneously immersed in it. As such, nearly every ontological theory very well could be true. We could be living in a simulation, we could be programs in a hyper-advanced computer, and it could even be possible that all things cease to exist when you’re not looking at them.

But while such uncertainty cannot be eliminated, we do have tools for managing it. Think of the scientific method, which demands objective evidence before conclusions are drawn. Thus far we have myriad proofs that reality is objective, even if our understanding of it is very much subjective. It is indeed possible that reality can be changed by our perception of it, a la The Secret and it’s ‘law of attraction’, but thus far lacking any evidence whatsoever to support such a theory, we can happily discard it.

My opinion is valid, because it is my opinion

Perhaps the most common post-truther stance is the argument that every opinion is valid, simply because someone holds it. You may believe racial segregation is a destructive force in society, but they believe it is better for all communities. You are entitled to your opinion and they are entitled to theirs – so the correct course of action is to vote and see which idea wins ‘on its merits’.

This argument plays strongly into the popular ideal of ‘freedom of speech’. It also happily bypasses the idea that opinions should be held accountable against available evidence. Apply such a standard, and the argument “I’m entitled to my opinion” quickly gains a qualification: You are not entitled to be wrong.

Who are you to tell me I am wrong?

Finally, we reach what in many ways is the foundation of the post-truth trend: who are you to tell me that something is wrong or right? These are my beliefs. How dare you attack something so important to me?

The practical answer to this question is quite simple: I have a right to challenge your opinion to ensure that factually invalid ideas do not lead to harmful conduct. But the psychological implications are far broader. It’s one thing to demonstrate your opinion is better supported by evidence than another person’s, but that isn’t the goal, is it? We can’t just point out another person’s error and expect them to immediately change their mind. In fact, cognitive biases such as the Backfire Effect, demonstrate that we are likely to get the opposite result.

The question of how best to engage with those that disagree with us is an important topic. But if the purpose of ethics is to help us decide what is right, then efforts to undermine ideas by appealing to uncertainty, relativism, and personal opinion must be seen for what they are: pure intellectual cowardice.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 JUN 2018

Meet Sophie. As the Head of Human Resources in her organisation, she begins to doubt the integrity of her management team when CCTV cameras are installed throughout her workplace with little warning. Sophie has made an appointment to speak with an Ethi-call counsellor.

In what follows, a highly trained counsellor responds to a fictional yet typical dilemma faced by callers who use The Ethics Centre’s free helpline, Ethi-call. Please note, this is not a substitute for an Ethi-call counselling session. It will give you an idea of what to expect if you ever need to use the service.

The counselling session

Sophie: I’ve never come across a situation like this in my 20 years as a HR professional. We are on the edge of a culture crisis and I’m not sure who I can trust.

Recently, a staff member was verbally assaulted by a trespasser on business premises outside of business hours. The victim felt it wasn’t serious enough to warrant legal intervention but he agreed with our workplace it wasn’t harmless enough to shrug off. Wishing to be seen as responsive to the event, management responded without my consultation by installing CCTV cameras inside and outside the office. Their reaction was quick and they did not have a specific policy to guide the decision. Staff arrived at work on Monday to find cameras on the premises without any explanation.

Ethi-call: As head of HR, how does your role fit within your organisation?

I look after the people in the organisation by implementing the HR policies of the business under the direction of general management. I’m a go to person for employees with workplace issues, advocating for staff in situations where they’ve been taken advantage of. I’m trusted by my peers. I’m the messenger for management, but most decisions I share are not mine and at times I even disagree with them. I’ve worked hard to build a culture of transparency and an environment where all staff can speak up.

Ethi-call: What’s the purpose and values of your organisation?

We exist for our customers and shareholders. We value honesty, safety, innovation, and recognition. But I feel the management team has traded honesty for safety in their latest decision.

Ethi-call: In your industry and HR, are there professional standards or a professional body that might be of relevance to this situation?

Yes, there is the Australian HR Institute, which has a professional code of ethics and professional conduct, plus my organisation also has a national peak body. I’ve phoned because it states I should lead others by modelling competent and ethical behaviour but in this situation I’m not sure what that is.

Ethi-call: What obligations do organisations have in relation to employee safety and privacy and where does your organisation fit?

Our privacy policy meets accepted industry standards. People know we can access their emails at any time and activity on our network isn’t private. People are aware about some privacy compromises. That being said, it’s certainly not an expressed part of company policy that we can film and monitor staff in the office.

As for safety, we have a duty of care to our employees and follow required WHS measures. It’s our responsibility to provide a safe workplace.

Ethi-call: Are you aware of any other organisations who have installed CCTV cameras in this way? What did they do?

This is part of the problem. I’m not sure of any business in this industry who has installed cameras in this way. It’s not like we’re a retail or security focused business. I need to seek advice from industry representatives. Maybe even a lawyer….

I want to believe the management team have our best interests at heart but now I’m not sure. Usually when there are big changes in our organisation, we consult with our staff and bring them on the journey with us.

To make matters worse, recent discussions about staff redundancies in the new financial year have leaked through the organisation.

Ethi-call: How would you describe your relationships with staff?

Staff trust me and I’m glad they do. I value the people around me, because without them the organisation would not exist. But I don’t feel comfortable being the mouthpiece for a management team whose motives in installing the cameras may be more sinister.

Ethi-call: What do you normally do when you don’t agree with the decisions of the management team?

Sometimes I speak up and sometimes I don’t. I draw on my HR expertise and my position in the organisation which helps me facilitate open conversations.

I thought we had a culture of transparency and consultation so I’m shocked I wasn’t consulted before this decision was made. Clearly this has implications on staff and my role as a leader in their HR team, given its potential to negatively impact the organisation and our culture. Maybe they thought they were doing the right thing, but it feels like they might be using the assault as an excuse to monitor employees disingenuously.

Ethi-call: You’ve said staff rumours are fearing the cameras will be used for more than security. Do you know for a fact if the cameras will be used for the staff review?

I don’t know this for sure. I completely understand everyone’s concerns though. My gut tells me they might be right. A while back, some employees had their emails audited to support the termination of their contracts. So, while I’m making assumptions at this point, I can’t help but think management has a history of using data in a way that undermines fairness in the workplace. But it’s just not clear yet if a lack of transparency in this instance mean questionable or bad intentions.

Ethi-call: So, what do you think is the purpose of security camera’s in an organisation?

I’ve been told the purpose is to protect the assets of the business, be it staff or equipment. This is a good thing, clearly, but there should be a clear privacy policy around access and use of recordings. It’s also very important the company be transparent when introducing new security measures – like cameras – into the workplace.

So what did Sophie take away from the call?

The conversation with the Ethi-call counsellor made me better understand my professional identity and what values I want to uphold – both within the organisation and in my profession. I have promised to engage and support the staff, but I feel I need to do a little bit more research on this and seek the advice of a trusted advisor before I act.

I feel strongly that if I want to maintain my professional integrity and the trust of my colleagues I can’t sit back and do nothing. I also expect the management team to live the values of the organisation as well and I should be courageous enough to have this conversation with them too.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 year, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-callis the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The value of principle over prescription

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Gordon Young The Ethics Centre 26 JUN 2018

Only two years ago, I said the question of feminism’s success was over. Sure, there was still plenty of mopping up to do – ingrained practices and subconscious beliefs that needed to be rooted out – but the war was won. Feminism was now the socially and institutionally accepted norm in the developed world. Everything else was just details.

As you can imagine, I’m no longer so sure of that stance.

The Trump era demonstrates that for many, the war is far from over. Whether we’re talking about the Men’s Rights Movement, hypermasculine pick-up artists, or the extremist fringe Incel movement, a resurgence of anti-feminist sentiment in recent years raises some serious concerns for the future of the debate.

Sociological analysis of platforms such as YouTube, Reddit, and 4chan have noted that – quite contrary to the overall changes to social norms – anti-feminist sentiments appear to be resurgent in online forums. Feminist campaigners and scholars have approached this issue by attempting to demonstrate the feminist goals of dismantling gender roles and toxic masculinity are beneficial to men too, not just women. In spite of their efforts, anti-feminist sentiments are re-emerging in ‘real world’ political and social discourses.

But I believe that such approaches to this debate miss a key factor that underlines this revival of patriarchal masculinity.

“In the battle of the sexes, there can only be one winner. And it wasn’t men.”

Competing for power

For women, the development of feminism was an experience of expanding freedom, autonomy, and the right to both. Restrictive ideals of ‘feminine’ careers and pursuits were slowly dismantled, economic mobility and independence was gradually wrested from the patriarchy, and both political freedom, and the recognised right to that political freedom, became enshrined in law and the policy of private companies.

While nobody can reasonably deny this hard-earned progress towards equal rights was the ethical imperative, we should recognise that this newly-won power for women came from somewhere. It came from men.

If we understand power as the ability for an individual or group to control their circumstances, and if that power within a given context cannot be shared, it must instead be competed for by the parties involved. And while women have had every justification in seeking their fair share of power in order to control their circumstances, seeing their public role in the world burgeon as a result, this same process has seen men’s shrink.

In the space of one generation they have gone from the undisputed leaders of society and the family unit, to adrift in a sea of uncertainty as the new world order of equal rights asserts itself.

The Incel movement – “involuntarily celibate”

All of this is nicely illustrated by the emergence of the Incel subculture. ‘Incel’ is an abbreviation for ‘involuntarily celibate’. It is a community comprised of young men who feel that sex – or even the opportunity for sex – has been denied to them by women, both individually and collectively. The layers of psychology surrounding this are many and complex, as captured in excellent detail in this piece by philosopher Amia Srinivasan. But while it is both easy and accurate to describe a perceived entitlement to sex as severely problematic, doing so ignores one very important reality: in many regards, men used to have that power.

Even as recently as the 1990s, a masculine trope where men were responsible for providing for and protecting their families was still quite well established. They were told they should be upright, decent, considerate, and strong. And in return for all of this, they would attract female partners who would recognise these qualities, and those female partners would reward them with sex.

Needless to say, this is an incredibly simplistic and largely inaccurate perception of traditional gender roles, ignoring as it does the vast number of people that did not experience this simple equation or who were victimised by it. But the fact remains it was also somewhat true. Where strict gender roles are enforced by society, a man is offered a very simple formula to follow to get female companionship and/or sex. Fulfil the traditional role of a ‘man’ and women would inevitably seek out your company – usually because their traditional role as ‘women’ meant they had few other options.

The rise of feminism has seen increased freedom and opportunity for both genders, but while it saw the role of women grow, it also saw this traditionally dominant role for men shrink. Many men have seen this as an opportunity to grow beyond the old restraints of masculinity, but others have found themselves adrift, lacking even the old traditional guidelines to tell them what their purpose is and how they should conduct themselves.

“Masculinity today is in crisis. Old ways for men to understand themselves, their role and their purpose, have fallen apart.”

Faced with the potentially colossal existential crisis this presents them with, many men are turning to reactionary anti-feminist movements in psychological self-defence, preferring to externalise their crisis into a fightable enemy rather than undertake the daunting task of creating a new and better self – a project which by its very nature must be undertaken alone and is often very painful. The question before us is what we can offer those seeking an identity in this new, dynamic age that can provide that precious sense of self, which doesn’t also depend on unrighteous dominance over others.

This question is neither the fault, nor the responsibility of women. But faced with the reality of a resurgence in patriarchal political sentiment, it is a problem that feminists and their allies are forced to deal with – whether we like it or not.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

We take perfection to mean flawlessness. But it seems we can’t agree on what the fundamental human flaw is. Is it our attachment to things like happiness, status, or security – things that are about as solid as a tissue? Our propensity for evil? Or is it our body and its insatiable appetite for satisfaction?

Four different philosophical traditions have answered this in their own ways and tell us how we can achieve perfection.

Platonism

Plato’s idea of perfection is articulated in his Theory of Forms. The Forms represent the abstract, ideal moulds of all things and concepts in existence, rather than actual things themselves. In short, the idea of something is more perfect than the tangible thing itself.

Take ‘red’ for example. Each of us will have a different understanding of what this means – red lipstick, a red brick house, a red cricket ball… But these are all different manifestations of red so which is the perfect one? For Platonists, the perfect, ideal, universal ‘red’ exists outside of space and time and is only discoverable through lots and lots of philosophical reflection.

Plato wrote:

He will do this [perceive the Forms] most perfectly who approaches the object with thought alone, without associating any sight with his thoughts, or dragging in any sense perception with his reasoning, but who, using pure thought alone, tries to track down each reality pure and by itself, freeing himself as far as possible from eyes, ears, and in a word, from the whole body, because the body confuses the soul and does not allow it to acquire truth and wisdom whenever it is associated with it.

In Platonist thought, the body is a distraction from the abstract thought necessary for philosophical speculation. Its fundamental flaw? Its carnal desires that shackle the soul.

Perfection for the individual, to sum up, is the arrival back to the soul’s state of pure contemplation of the Forms. This out of body state of contemplation is far from the idea of the perfect face and physique we often think about today. Indeed, a perfect physical form for Palto is impossible. It is all in the imagination.

Hinduism

In Hinduism’s Advaita school of philosophy, perfection means the full comprehension and acceptance of Oneness.

It’s when you realise your soul (or your atman) is the same as everyone else’s and you are all part of the one, unchanging, metaphysical reality (the Brahman). In this state of realisation, the always changing, material world of maya reveals itself to be an illusion and anything attached to this world, including your actions, are illusions as well. (There are parallels with this and the idea of Plato’s Cave, which is narratively conceived of in The Matrix.)

To attain this status of perfection, an individual must surrender to their caste role and perform that duty to excellence. No matter what they did, they would understand their actions had no effect on the Brahman and to believe so, was a trick of the ego. They focused on renouncing all earthly desires and striving to become completely detached from the world through the specific rituals of their caste role.

Krishna said:

A man obtains perfection by being devoted to his own proper action. Hear then how one who is intent on his own action finds perfection. By worshipping him [Brahman], from whom all beings arise and by whom all this is pervaded, through his own proper action, a man attains perfection … He whose intelligence is unattached everywhere, whose self is conquered, who is free from desire, he obtains, through renunciation, the supreme perfection of actionlessness. Learn from me, briefly, O Arjuna, how he who has attained perfection, also attains to Brahman, the highest state of wisdom.

By “actionlessness”, Krishna means the supreme effort of surrendering everything, including your own actions, so they become “non-action”. If everything is an illusion in the face of Brahman, we mean everything.

Christianity

A sainted bishop named Gregory of Nyssa classified perfection as being and acting just like God’s human form, Christ – that is, completely free of evil. Nyssa said:

This, therefore, is perfection in the Christian life in my judgement, namely, the participation of one’s soul and speech and activities in all of the names by which Christ is signified, so that the perfect holiness, according to the eulogy of Paul, is taken upon oneself in “the whole body and soul and spirit”, continuously safeguarded against being mixed with evil. Perfection lies in the total transformation of the individual. He/she must live, act, and essentially, be all that Christ was, meaning that, as Christ was God manifest in human form, completely free from evil, so too the Christian individual must sever all evil from his/her being.

While the Socratic ideal of perfection requires pure “abstract” thought, and the Hindu ideal requires sublimating individualism into Oneness, the Christian ideal requires cultivating the characteristics of Christ and expelling all that is unlike him from yourself.

Sufism

The Sufi scholar Ibn ‘Arabi had a concept of perfection that echoes the three discussed above. For him, perfection is the individual’s complete knowledge of the abstract and the material, leading to a prophetic (or Christ like) character.

Let’s break that down. He says:

The image of perfection is complete only with knowledge of both the ephemeral and the eternal, the rank of knowledge being perfected only by both aspects. Similarly, the various other grades of existence are perfected, since being is divided into eternal and non-eternal or ephemeral. Eternal Being is God’s being for Himself, while non-eternal being is the being of God in the forms of the latent Cosmos.

The beginning of the passage states that perfection requires knowledge of the eternal and the material. The eternal is God in Himself, and the non-eternal is the Cosmos, including humanity, who in striving for the perfection of the eternal, expresses it.

But Ibn ‘Arabi stresses neither of these knowledges negate the other. In fact, by learning only of the eternal, or only of the material, both would be incomplete since they are simply different manifestations of the same Being. Perfection, then, is not about negation – but continual striving to transformation. Onwards and upwards!

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Virtue ethics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

“The pen would smoothly write the things it knew, but when it came to love it split in two, a donkey stuck in mud is logic’s fate – Love’s nature only love can demonstrate.” – Rumi

Rumi (1207—1273) has long been recognised as one of the most important contributors to Islamic literature and Sufism, the spiritual and mystic element of Islam. His enormous collection of mystical poetry is considered among the best that has ever been produced. His seminal text is the Masnavi, a six book poem written in rhyming couplets. It is so revered as an expression of Godly knowledge that it is referred to as “The Koran in Persian”.

What is Sufism?

To understand Rumi, you need to understand Sufism. It is often misrepresented as a sect, school, or deviant form of Islam but is better described as a distinct stream in Islamic spirituality. Sufism was first embodied by Muhammad and his early followers, then medieval scholars like Abu Hamid Al-Ghazzali, Ibn Arabi, and of course, Rumi.

Sufism is characterised by its focus on moral cultivation and establishing a personal connection to God through reforming, disciplining, and purifying the ego. It seeks to attain this intuition of God through disciplines that practice an austere lifestyle known as ascetism. One example of this is dhikr, a form of worship where you become absorbed in rhythmic repetitions of God’s name.

Sufism seeks a type of knowledge outside worldly intellect – one that is intuitive and is inextricably tied to the Divine.

Life of Rumi

Rumi, known in Iran and Central Asia as Mowlana Jalaloddin Balkhi, was born in 1207 in the province of Balkh, which is now the border region between Afghanistan and Tajikistan. His family left when he was a child shortly before Genghis Khan and his Mongol army arrived. They settled permanently in Konya, central Anatolia, which was formerly part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Rumi was probably introduced to Sufism through his father, Baha Valad, a popular preacher who also taught Sufi piety to a group of disciples.

The turning point in Rumi’s life came in 1244 when he met a wandering Sufi in Konya called Shamsoddin of Tabriz. Shams, as he was most often referred to by Rumi, taught him the most profound levels of Sufism, transforming him from a devout religious scholar to an ecstatic mystic.

Rumi died on 17 December 1273 shortly after completing his work on the Masnavi. His passing was deeply mourned by the citizens of Konya, including the Christian and Jewish communities. His disciples formed the Mevlevi Sufi order and named it after Rumi, whom they referred to as ‘Our Master’ (which translates to Mevlana in Turkish and Mowlana in Persian). They are better known in the West as the Whirling Dervishes, because of the distinctive dance they now perform as one of their central rituals.

Rumi’s death is commemorated annually in Konya, attracting pilgrims from all corners of the globe and every religion. The popularity of his poetry has risen so much in the last couple of decades that the Christian Science Monitor identified him as the most published poet in America in 1997 and UNESCO declared 2007 to be the Year of Rumi.

Overvaluing intellect

Rumi, like most Sufis, praised the intellect and considered its refinement a religious imperative. But he was clear about the types of knowledge he believed it could sufficiently possess. He considered o domain the sentimental and material world, not the theoretical and metaphysical one.

Rumi’s caution was this: when one relies solely on their own intellect to understand Being and Reality, they risk confining their understanding to a mortal and ultimately finite resource – themselves. He regarded it a folly of the ego to believe one’s intellect limitless and warned against reducing God to abstract puzzles in order to maintain that belief. Rumi scorned placing the intellect too high and pursuing knowledge for knowledge’s own sake.

“He knows a hundred thousand superfluous matters connected with the (various) sciences, (but) that unjust man does not know his own soul.

He knows the special properties of every substance, (but) in elucidating his own substance (essence) he is (as ignorant) as an ass.” – Rumi

The transcendence of man

So, if intellect isn’t enough, what is? Rumi would say, ‘Divine love.’

This divine love can also be translated as grace or friendship with God. In the Islamic worldview, humanity is unique in its capacity to autonomously know God, and this gives people an honoured status. Even so, no human can achieve divine love out of their own efforts. They can only be granted it.

Rumi was of the view that seeking essential knowledge – knowledge about the essence of humanity – was a way one might be granted divine love. It was the best type of knowledge, because it was tied to questions of meaning, purpose, and death. In other words, knowing yourself was a means of knowing God.

According to the Sufis, knowledge of God comes in three levels: material, conceptual, and experiential. Think of it as the different between knowing an apple exists, reading a detailed Wikipedia page about it, and eating one in the flesh. All three are different forms of knowing what an apple is – but each deepens in understanding. The last level is transformative in a way the other two are not. Try explaining what an apple tastes like to someone who has never had one. You may come very close, but they will never know what you mean unless they take a bite themselves.

Likewise, the Sufis believed that the highest knowledge of God was something that could only be experienced. To read and contemplate upon God or the universe was one thing. But experiencing God was something totally different, something impossible to intellectualise.

Rumi believed manifesting the four virtues – courage, wisdom, and temperance, which when balanced, lead to perfect justice, the fourth virtue – would lead to some form of transcendence above the hubbub of life’s claims and counterclaims. But when every human being’s views cannot be divorced from their experience, how was this possible?

For Rumi, this highlighted humanity’s dependence on God. Only a friend of God, or Wali, could be objective enough to see truth and loving enough to be just.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

WATCH

Relationships

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 31 MAY 2018

IQ2 Australia and Vivid Ideas debated whether, ‘#MeToo has gone too far’. Here is a curated snapshot of the public conversation – just in case you’ve had your head in the sand.

Article

Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades

New York Times

Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

5 October 2017

This is the article that broke the Harvey Weinstein story. While it’s now internationally infamous, it is well worth reading to understand how strong the structures that protected Weinstein were. It includes his first official response.

Video

TIME Person of the Year 2017: The Silence Breakers

TIME

Diane Tsai, Spencer Bakalar, Julia Lull [producers]

6 December 2017

Dishwashers, Hollywood stars, academics, hotel staff, journalists, an engineer, and even a senator feature in this short video by TIME of people speaking up against sexual harassment.

Article

I went on a date with Aziz Ansari. It turned into the worst night of my life

babe.net

Katie Way

13 January 2018

This piece wins the title of ‘Most Divisive Contribution to the #MeToo Movement’. It is both celebrated as a precise example of young women’s damaging sexual experiences and scorned for undermining #MeToo by lacking journalistic integrity and conflating “bad sex” with assault.

Article

The Humiliation of Aziz Ansari

Caitlin Flanagan

The Atlantic

14 January 2018

This response to the babe.net article labels it “3,000 words of revenge porn”. Ouch. It highlights the generational differences in attitudes to sex and feminist values that has been underpinning the #MeToo debate.

A separate yet notable moment in the generational rift between women over #MeToo was when Katie Way, the 22 year old author of the Ansari article called Ashleigh Banfield, a 50 year old female news anchor who criticised her piece, “that burgundy lipstick bad highlights second-wave feminist has-been”.

Article

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly

Michael Salter

ethics.org.au

31 January 2018

IQ2 guest Michael Salter is an expert in trauma, gendered violence, sexual abuse, and social media. He reflects on how the #MeToo movement can retain potency and serve justice.

Here seems a good space to explain why we invited two men to be part of this debate – Michael Salter and Benjamin Law. It’s an approach some people disagree with. The Ethics Centre and Vivid Ideas felt the conversation would benefit if both women and men took part and speak with another.

Podcast

Has #MeToo Gone Too Far, or Not Far Enough?

Waleed Aly & Scott Stephens

The Minefield

7 March 2018

A favourite ethicist of ours Scott Stephens poses a key challenge to the #MeToo movement: are we comfortable for this revolution to take innocent people as collateral damage?

It’s a question Teen Vogue columnist Emily Lindin answered with her controversial tweet, “If some innocent men’s reputations have to take a hit in the process of undoing the patriarchy, that is a price I am absolutely willing to pay”.

Video

The Feed SBS VICELAND

Jeanette Francis

“Lads, it’s time to admit if you’ve been gross.” IQ2 guest and TV journalist Jeanette Francis, aka Jan Fran, asks why there isn’t a #MeToo hashtag for men, the ‘doers’ of the harassing. This little video package with its provocation and stats on sexual harassment is a finalist in the mid-year Walkley awards.

Watch the IQ2 debate here: ‘#MeToo has gone too far’

Libby-Jane Charleston & Michael Salter vs Jan Fran & Ben Law

A collaboration between The Ethics Centre and Vivid Ideas

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 22 MAY 2018

Beachgoers would have noticed our lucky country has been hit with a rather European trend. Or is it South American?

Women and girls of all ages and shapes were donning g-string swimsuits and Brazilian bottoms. Arse cheeks were out and as sun-kissed as a brown forearm, curiously suggesting they had never been covered up. Insert thinking emoji face here.

If conversations and interactions underneath Instagram posts are anything to go by, people seem to care a lot about this newish oceanside fashion. People have been looking and commenting and rubbernecking and commenting some more. Was that the sound of a drone hovering over the group of young women lying belly down on the sand?

“Whether a bit more butt cheek is nudity or not, our different reactions to the sight of peach shaped posteriors reflect so much on our different ideas of bodies, gender, and sexuality.”

Whether a bit more butt cheek is nudity or not, our different reactions to the sight of peach shaped posteriors reflect so much on our different ideas of bodies, gender, and sexuality. Australia is one of the most diverse countries in the world, so it makes sense some sort of overarching cultural attitude to how much skin we should show doesn’t exist. Even individuals will sometimes revere and scorn the sight of skin – context is everything.

Nudity can be a beautiful thing. It’s darn delightful to see the kids running around the backyard in the nutter on a hot day as the sprinkler runs, free of all the bodily self-consciousness that will hit them in adolescence. Such sweet, innocent freedom.

But by the time we’re all growed up, we’re sexual beings and our bods better be covered or it’s just down right creepy – unless you’re at the beach of course. It’s often said women are more free to dress how they like in any environment but even a boringly functional shoulder on a hot summer’s day is wildly inappropriate in some workplaces. Then again, imagine a man exposing his knees by wearing shorts in a corporate environment or strutting into the boardroom in flip flops.

Shoulders, knees and toes, so risqué. No wonder people love to get semi-nude when they’re near sand and saltwater. The working week’s uniform is so prudish when compared with the itsy bitsy teenie weenie things we’re permitted to sport in public at the beach. And perhaps that’s the beauty of this summer’s bare butt trend – a liberation of the social and cultural expectations most are happy to play along with but only for limited week day bursts.

Maybe it’s the influence of Kim Kardashian’s glorious glutes. Maybe HBO started the nudity thing years ago – Australians tend to follow northern hemisphere trends a season or more later. Maybe it isn’t about popular culture at all and it’s just that women want more skin tanned and are seeing it’s now acceptable. Could we stretch this to a health argument by bringing up vitamin D? Or is it just that despite the good advocacy work of the Cancer Council, people can’t resist the warm, fuzzy feeling of sunrays touching their arse?

“On one hand, you could argue the butt cheek trend is marking a positive social shift in attitudes to women’s bodies – one where we’re less concerned about the shape or size of anyone’s booty.”

On one hand, you could argue the butt cheek trend is marking a positive social shift in attitudes to women’s bodies – one where we’re less concerned about the shape or size of anyone’s booty and getting it out there shows women and girls in particular aren’t as hung up about their physical selves as we once believed.

On the other hand, you could argue this is a submission to sexism. Plenty of people don’t like to see women and girls enjoying their bodies this way. While arguments in favour of modesty can attract accusations of a controlling type of chauvinism, they are often made in defence of women’s liberty. Why must the so called fairer sex feel an obligation to display so much skin? Can’t women and girls have fun in the sun without feeling they need to sexualise themselves? Is all this bum display a nasty product of patriarchy getting its insidious tentacles into our beachside R&R?

I descend from a people not known for bodily inhibitions. If Hungarians aren’t presented with a sign in public baths telling them to don swimwear, the only suit necessary is the one your mama gave you. Some baths even supply disposable coverings for men and women’s nether regions in case they forget to pack something (although I suspect there are a few Magyars who don’t own a cozzie).

The other side of my family values dressing modestly in public. Headscarves are worn to social gatherings and ankles covered. Someone walking bare butt into a space, let alone naked, is unimaginable.

So, do we care which direction Australian beaches head? And how does a culturally diverse country make a general rule around appropriate levels of dress?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Sally Murphy The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

Torn between rights and obligations, a long-suffering widower agonises over how to divvy up his assets, while an aunt’s growing nest egg is in danger of being squandered. This month we are talking about inheritance on Ethi-call.

Disclaimer: The cases shared here are fictional accounts of typical dilemmas faced by callers who use The Ethics Centre’s free helpline Ethi-call. This is not a substitute for an Ethi-call counselling session.

Inheritance is a sticky issue. No matter your role – the writer of the will, the executor, the recipient, or the advisor – each individual has a view of how important justice, fairness, obligations, or rights are in making their decisions. If you’re lucky, these views are shared among all involved. At Ethi-call, The Ethics Centre’s free counselling service for ethical dilemmas, we know they usually aren’t.

Take this typical scenario:

Peter is a widower with two children in their late 40s. His daughter is a university educated high earner with a husband and two children. His son doesn’t have qualifications and although he works hard, he changes jobs frequently, never having found a satisfying career path. He is divorced and also has two children.

Peter has a degenerative disease and knows he will not live to see his grandchildren grow up. His will provides a 50/50 split of his assets between his children but he feels his son needs more help.

Peter tried talking with his daughter about this but she was upset he was considering treating them differently. She said she should not be penalised for her hard work and her brother is not entitled more because of his own life choices. Peter loves both his children and doesn’t want his daughter to feel undervalued. Some of his friends have even said she deserves more than half as a reward for the disciplined life she’s led. His wife who died four years ago wanted to make sure all her grandchildren were provided for generously and Peter wants his will to be fair, without causing pain or ill will. He just can’t see how he can achieve this. He is very distressed about the decision he has to make.

Ethics asks, “What ought one do?” I put to you, “What should Peter do?” He knows he must consider everyone who might be impacted by his decision and he has already identified the following:

- Wanting to be fair and equal to his children

- The capacity for inheritance to be perceived as a reward or punishment

- His role as a grandfather and the duty he feels to support his grandchildren

- An absolute desire to preserve his relationship with his children and their relationship with each other

If Peter were to contact Ethi-call, some questions he might be asked include:

- What is the purpose of a will?

- What has been your experience of receiving inheritance in the past and do you think it was handled well?

- What are the religious or cultural norms that guide your decisions in life?

There is no doubt his children may each desire different outcomes. But if he has to choose, what is most important to him when allocating his estate?

At least for Peter’s children, his final wishes will be sorted before he passes away. What if the writer of the will is already gone, and the family can only guess what the intentions were behind it?

Take this situation:

Before Sarah’s mother died, she said she wanted her young granddaughter Alexis to inherit a significant sum of money when she turned 18. She asked her only daughter Sarah, Alexis’ aunty, to be trustee of the funds until she turned 18 because Alexis’ father had passed away. Sarah’s investing has seen the funds grow significantly. Alexis’ maturity? Not so much.

Now months away from being eligible to receive her inheritance, Sarah is concerned about Alexis’ behaviour. She dropped out of school, is not working, and smokes a lot of pot. Sarah hopes this is just a phase but sees Alexis’ mum in her and worries it might just be her personality or chosen path.

Alexis and her mum struggle financially. Sarah has no idea how they get by and can see a cash injection could relieve pressure. But she is also concerned they won’t have the willpower, skills, or knowledge to look after the funds appropriately. She believes the signs show if Alexis doesn’t squander it, her mum will.

Sarah is torn between her duty to fulfil her mother’s wishes and her loyalty to her and her memory. She was a woman with a strong work ethic, who was dedicated to growing her personal wealth through prudence and patience. Sarah has every intention of following the requirements of the will, but she is struggling with how much control she is entitled to. What ought Sarah do?

- Should she try and help Alexis learn about money management?

- Is it her right to make suggestions around how the money is invested or saved?

- Whose wishes matter most – Sarah’s deceased mother, Sarah as trustee, Alexis, or Alexis’ mother?

Sarah is a woman of integrity and will respect Alexis’ right to inherit the money. But is there a way she can fulfil her mother’s wishes and do the best she can to ensure Alexis respects her legacy?

Both of these fictional cases depict someone struggling with what to do in a situation. An Ethi-call counsellor will never tell someone what to do. Instead, they follow a framework developed by The Ethics Centre over the last 25 years. This framework is driven by a wide range of questions that can often help unpack a dilemma in a way that the caller was not able to do on their own. And while a counsellor may seem to ask a lot of questions at first, there is a reason for them.

Struggling with inheritance can feel like being inside the home of the loved one you have lost. Memories, treasures, and sentimental trinkets pull you in multiple directions. But every house has a door. And every dilemma has a beginning.

There is no magic dust to make what is difficult, easy. But Ethi-call can help you find relief with understanding. A counsellor’s impartial and expert advice can be a guiding hand through neglected corridors and cobwebbed cupboards. Sometimes, someone removed from the trauma of a loved one’s death is exactly who you need to help you make your way through what is one of life’s hardest challenges.

Tough decisions are part of being human. We can help. Let us show you how. Book your free Ethi-call session here.Sally Murphy is an Ethi-call counsellor and manager of education programs at The Ethics Centre.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

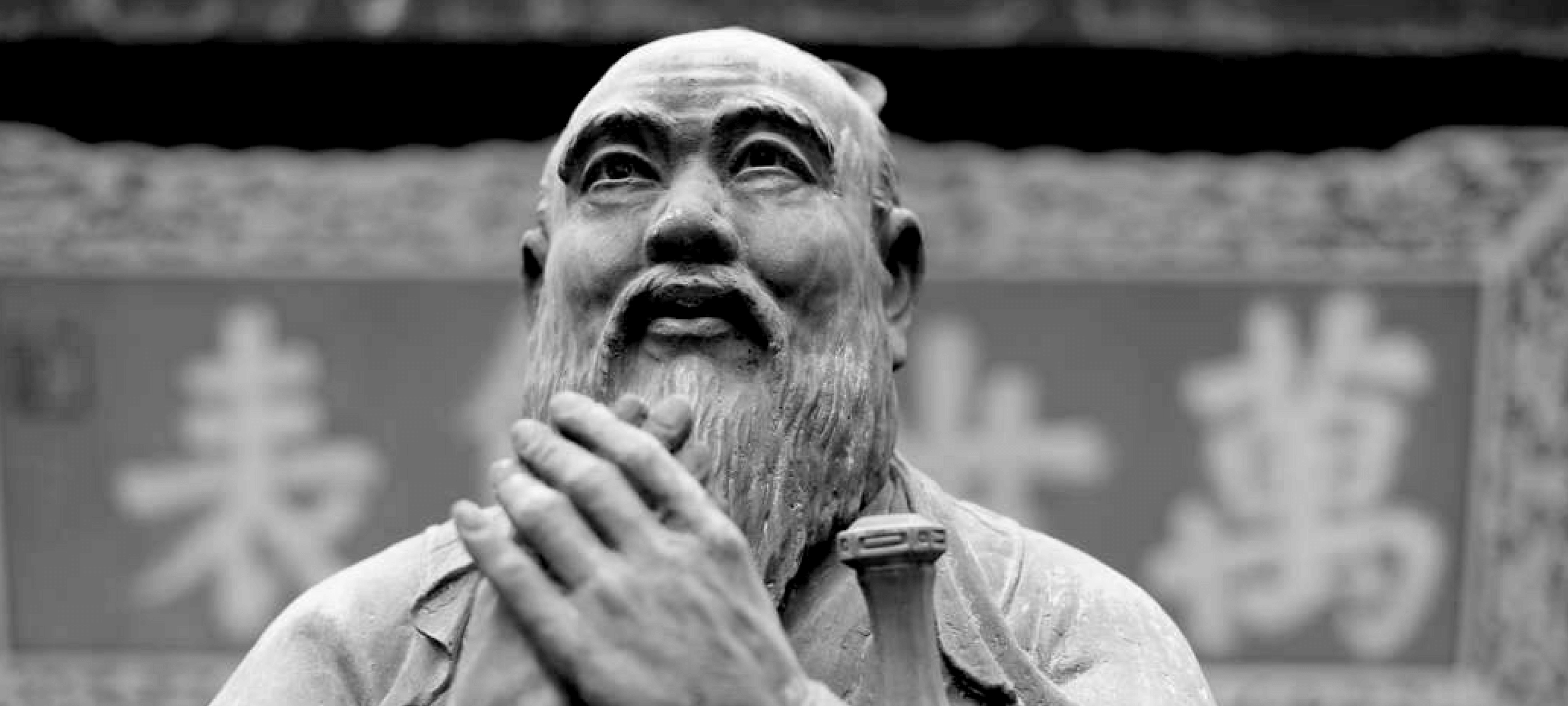

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

Confucius (551 BCE—479 BCE) was a scholar, teacher, and political adviser who used philosophy as a tool to answer what he considered to be the two most important questions in life… What is the right way to rule? And what is the right way to live?

While he never wrote down his teachings in a systematic treatise, bite sized snippets of his wisdom were recorded by his students in a book called the Analects.

Underpinning Confucian philosophy was a deeply held conviction that there is a virtuous way to behave in all situations and if this is adhered to society will be harmonious. Confucius established schools where he gave lectures about how to maintain political and personal virtue.

“It is virtuous manners which constitute the excellence of a neighborhood.”

His ideas set the agenda for political and moral philosophy in China for the next two millennia and are emerging once again as an influential school of thought.

Humble beginnings

Confucius was born in 551 BC in a north-eastern province of China. His father and mother died before he was 18, leaving him to fend for himself. While working as a shepherd and bookkeeper to survive, Confucius made time to rigorously study classic texts of ancient Chinese literature and philosophy.

At the age of 30, Confucius began teaching some of the foundational concepts he formulated through his studies. He developed a loyal following and quickly rose up the political ranks, eventually becoming the Prime Minister of his province.

But at the age of 55 he was exiled after offending a higher ranking official. This gave Confucius an opportunity to travel extensively around China, advising government officials and spreading his teachings.

He was eventually invited back to his home province and was allowed to re-establish his school, which grew to a size of 3000 students by the time he died at age 72.

The golden age

Underpinning much of Confucius’ thought was a belief that Chinese society had forgotten the wisdom of the past and that it was his duty to reawaken the people, particularly the young, to these ancient teachings.

Confucius idealised the historical Western Zhou Dynasty, a time, he claimed, when living standards were high, people lived and worked in peace and contentment, the leaders carried out their duties in accordance with their rank, and the social order was stable and harmonious.

Confucius devoted his life to teaching the wisdom of this ancient society to his contemporaries in the hope of reinventing it in the present. For this reason, he didn’t claim to be an original thinker, but a receptacle of past wisdom. “I transmit but do not innovate”, he said.

Dao, de, and ren

While Confucius never wrote a systematic philosophical treatise, there are three intertwined concepts that run through his philosophy: Dao, De, and Ren.

Dao: Confucius interpreted Dao to mean a Way of living, or more specifically the right Way of living. This was not a concept he made up. It was already a central part of Chinese belief systems about the natural order of the universe. Dao is a slippery but profound concept suggesting there is a singular Way to live that can be intuited from the universe, and that all of life should be directed towards living this Way. If the Way is followed, the individual and society will be in perfect harmony.

De: Confucius saw De as a type of virtue that lay latent in all humans but that had to be cultivated. It was the cultivation of this virtue, Confucius believed, that allowed a person to follow the Way. It was in family life that people learned how to cultivate and practice virtuous behaviours. In fact, many of the main Confucian virtues were derived from familial relationships. For example, the relationship between father and son defined the virtue of piety and the relationship between older and younger siblings defined the virtue of respect. For this reason, Confucian ethics did not leave much room for an individual to exist outside of a family structure. Knowing where you stood in your family and your society was key to living a virtuous life.

Ren: While most Confucian virtues were cultivated within a strict social and family structure, ren was a virtue that existed outside this dynamic. It can be translated loosely as benevolence, goodness, or human-heartedness.

Confucius taught that the ren person is one who has so completely mastered the Way that it becomes second nature to them. In this sense ren is not so much about individual actions but what type of person you are. If you perform your familial duties but do not do so with benevolence, then you are not virtuous. Ren was how something was done, rather than the act itself.

Contemporary influence and relevance

Confucius’ influence on Chinese society during his life and in the two millennia since has been enormous. His sound bite like philosophies became China’s handbook on politics and its code of personal morality.

“He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.”

It wasn’t until Mao’s Cultural Revolution that some of the basic tenets of Confucian ethics were publicly denounced for the first time. Mao was future oriented and utopian in his politics, and so Confucius’ idea of governance and ethics based in the ancient classics was considered dangerous and subversive. In fact, Mao’s Red Guards referred to the old sage as “The Number One Hooligan Old Kong”.

But in the past decade, the Communist Party has realised Confucius’ teachings might be useful again. The surge of wealth that has accompanied free market capitalism in China has meant that many of Mao’s ideologies no longer make sense for the government. This has prompted a resurgence of State led interest in Confucius as an alternative ideological underpinning for the current government.

While this is seen by many as a way for China to build a political future based on its philosophical past, others feel that the Communist Party has emphasised Confucian ideas about hierarchical social structure and obedience, while sidelining notions of virtue and benevolence.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights