Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Moral absolutism is the position that there are universal ethical standards that apply to actions regardless of context.

Where someone might deliberate over when, why, and to whom they’d lie, for example, a moral absolutist wouldn’t see any of those considerations as making a difference – lying is either right or wrong, and that’s that!

You’ve probably heard of moral relativism, the view that moral judgments can be seen as true or false according to a historical, cultural, or social context. According to moral relativism, two people with different experiences could disagree on whether an action is right or wrong, and they could both be right. What they consider right or wrong differs according to their contexts, and both should be accepted as valid.

Moral absolutism is the opposite. It argues that everything is inherently right or wrong, and no context or outcome can change this. These truths can be grounded in sources like law, rationality, human nature, or religion.

Deontology as moral absolutism

The text(s) that a religion is based on is often taken as the absolute standard of morality. If someone takes scripture as a source of divine truth, it’s easy to take morally absolutist ethics from it. Is it ok to lie? No, because the Bible or God says so.

It’s not just in religion, though. Ancient Greek philosophy held strains of morally absolutist thought, but possibly the most well-known form of moral absolutism is deontology, as developed by Immanuel Kant, who sought to clearly articulate a rational theory of moral absolutism.

As an Enlightenment philosopher, Kant sought to find moral truth in rationality instead of divine authority. He believed that unlike religion, culture, or community, we couldn’t ‘opt out’ of rationality. It was what made us human. This was why he believed we owed it to ourselves to act as rationally as we could.

In order to do this, he came up with duties he called “categorical imperatives”. These are obligations we, as rational beings, are morally bound to follow, are applicable to all people at all times, and aren’t contradictory. Think of it as an extension of the Golden Rule.

One way of understanding the categorical imperative is through the “universalisability principle”. This mouthful of a phrase says you should act only if you’d be willing to make your act a universal law (something that everyone is morally bound to following at all times no matter what) and it wouldn’t cause contradiction.

What Kant meant was before choosing a course of action, you should determine the general rule that stands behind that action. If this general rule could willingly be applied by you to all people in all circumstances without contradiction, you are choosing the moral path.

An example Kant proposed was lying. He argued that if lying was a universal law then no one could ever trust anything anyone said but, moreover, the possibility of truth telling would no longer exist, rendering the very act of lying meaningless. In other words, you cannot universalise lying as a general rule of action without falling into contradiction.

By determining his logical justifications, Kant came up with principles he believed would form a moral life, without relying on scripture or culture.

Counterintuitive consequences

In essence, Kant was saying it’s never reasonable to make exceptions for yourself when faced with a moral question. This sounds fair, but it can lead to situations where a rational moral decision contradicts moral common sense.

For example, in his essay ‘On a Supposed Right to Lie from Altruistic Motives’, Kant argues it is wrong to lie even to save an innocent person from a murderer. He writes, “To be truthful in all deliberations … is a sacred and absolutely commanding decree of reason, limited by no expediency”.

While Kant felt that such absolutism was necessary for a rationally grounded morality, most of us allow a degree of relativism to enter into our everyday ethical considerations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

When do we dumb down smart tech?

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Aisyah Shah Idil The Ethics Centre 19 MAR 2018

If smart tech isn’t going anywhere, its ethical tensions aren’t either. Aisyah Shah Idil asks if our pleasantly tactile gadgets are taking more than they give.

When we call a device ‘smart’, we mean that it can learn, adapt to human behaviour, make decisions independently, and communicate wirelessly with other devices.

In practice, this can look like a smart lock that lets you know when your front door is left ajar. Or the Roomba, a robot vacuum that you can ask to clean your house before you leave work. The Ring makes it possible for you to pay your restaurant bill with the flick of a finger, while the SmartSleep headband whispers sweet white noise as you drift off to sleep.

Smart tech, with all its bells and whistles, hints at seamless integration into our lives. But the highest peaks have the dizziest falls. If its main good is convenience, what is the currency we offer for it?

The capacity for work to create meaning is well known. Compare a trip to the supermarket to buy bread to the labour of making it in your own kitchen. Let’s say they are materially identical in taste, texture, smell, and nutrient value. Most would agree that baking it at home – measuring every ingredient, kneading dough, waiting for it to rise, finally smelling it bake in your oven – is more meaningful and rewarding. In other words, it includes more opportunities for resonance within the labourer.

Whether the resonance takes the form of nostalgia, pride, meditation, community, physical dexterity, or willpower is minor. The point is, it’s sacrificed for convenience.

This isn’t ‘wrong’. Smart technologies have created new ways of living that are exciting, clumsy, and sometimes troubling in their execution. But when you recognise that these sacrifices exist, you can decide where the line is drawn.

Consider the Apple Watch’s Activity App. It tracks and visualises all the ways people move throughout the day. It shows three circles that progressively change colour the more the wearer moves. The goal is to close the rings each day, and you do it by being active. It’s like a game and the app motivates and rewards you.

Advocates highlight its capacity to ‘nudge’ users towards healthier behaviours. And if that aligns with your goals, you might be very happy for it to do so. But would you be concerned if it affected the premiums your health insurance charged you?

As a tool, smart tech’s utility value ends when it threatens human agency. Its greatest service to humanity should include the capacity to switch off its independence. To ‘dumb’ itself down. In this way, it can reduce itself to its simplest components – a way to tell the time, a switch to turn on a light, a button to turn on the television.

Because the smartest technologies are ones that preserve our agency – not undermine it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

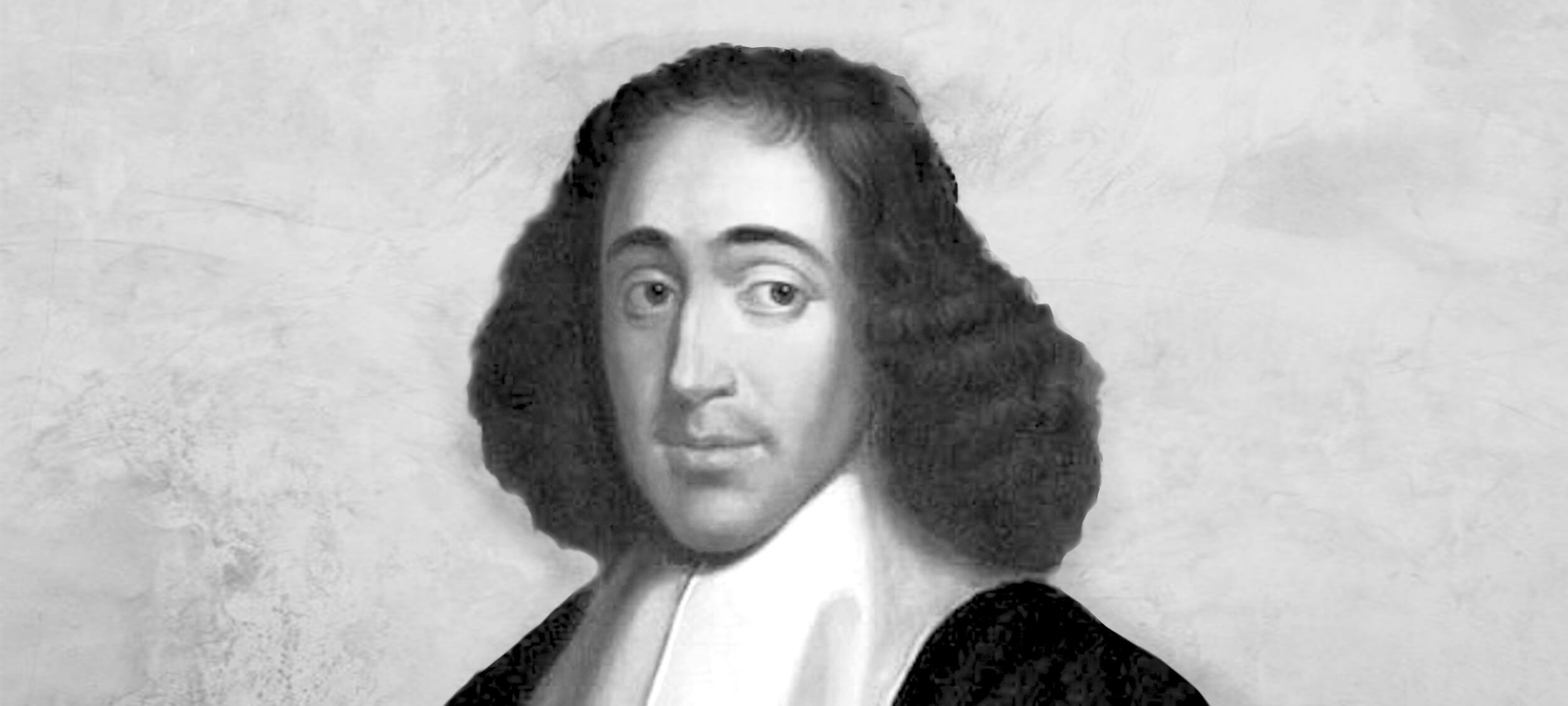

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza was a 17th century Jewish-Dutch philosopher who developed a novel way to think about the relationship between God, nature, and ethics. He suggested they are all interconnected in a single animating force.

While Spinoza had a reputation for modesty, gentleness, and integrity, his ideas were considered heretical by religious authorities of the time. Despite excommunication by his own community and rabid denunciations from religious authorities, he remained steadfast to his philosophical outlook, and stands as an exemplar of intellectual courage in the face of personal crisis.

Jewish upbringing

Spinoza was born in 1632 in the thriving Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. His family were Sephardic Jews who fled Portugal in 1536, after being discovered practicing their religion in secret.

He was a studious and intelligent child and an active member of his synagogue. However, in his later teenage years, Spinoza began reading the philosophies of Rene Descartes and other early Enlightenment thinkers, which led to him to question certain aspects of his Jewish faith.

The problem with prayer

For the young Spinoza, prayer signified everything that was wrong with organised religion. The idea that an omnipotent being would listen to one’s prayers, take them into consideration, and then change the fabric of the universe to fit these individual desires was not only superstitious and irrational, but also underpinned by a type of delusional narcissism.

If there was any chance of living an ethical life, Spinoza reasoned, the first idea that would have to go was the belief in a transcendent God that listened to human concerns. This also meant renouncing the idea of the afterlife, admitting that the Old Testament was written by humans, and denouncing the possibility of any other type of divine intervention in the human world.

God-as-nature

Despite this, Spinoza was not an atheist. He believed there was still a place for God in the universe, not as a separate being who exists outside of the cosmos, but as a type of pervasive force that is inextricably bound up with everything inside it.

This is what Spinoza called “God-as-nature”, which suggests that all reality is identical with the divine and that everything in the universe composes an all-encompassing God. God, according to Spinoza, did not design and create the world, and then step outside of it, only to manipulate it every now and then through miracles. Rather, God was the world and everything in it.

Spinoza’s formulation of “God-as-nature” attracted many of the brightest minds of Europe of his time. The great German philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, visited Spinoza in Amsterdam to talk the theory over and concluded that Spinoza had a “strange metaphysics full of paradoxes. He thinks God and the world are one thing and that all created things are only modes of God.”

An ethical life of intellectual inquiry

Ultimately, Spinoza believed that replacing the idea of a transcendent God with “God-as-nature” was a step towards living a truly ethical life. If God was nature, then coming to know God was a process of learning about the world through study and observation. This pursuit, Spinoza reasoned, would draw people out of their narcissistic and delusional ways of understanding reality to a universal perspective that transcended individual concerns. This is what Spinoza called seeing things from the point of view of eternity rather than from the limited duration of one’s life.

For Spinoza, the ethical life was therefore the equivalent of an intellectual journey. He thought that learning about the world could lead a person towards understanding their connection to all other things. This, in turn, could lead one to see their interests as essentially intertwined with everything else. From such a perspective, the world no longer appears to be a hierarchy of competing individuals, but more like a web of interlocking interests.

Intellectual courage

These ideas got Spinoza into a lot of trouble. He was excommunicated from the Jewish community of Amsterdam when he was 23 and was considered by the Church to be an emissary of Satan. Nevertheless, he refused to compromise on his philosophical outlook and remained an outsider for the rest of his life. He eventually found refuge among a group of tolerant Christians in The Hague where he spent the rest of his life working as a lens grinder and private tutor.

A few months after his death in 1677, Spinoza’s philosophies were published as a collection called The Ethics. Its key ideas became very important for subsequent Enlightenment philosophers, who somewhat distorted his message to make them fit with their own radical atheism, despite his belief in “God-as-nature”.

Throughout the centuries, his ideas and life have continued to inspire not only philosophers but also scientists. Einstein wrote:

“I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”

In our current day, it is hard to fathom what made Spinoza’s ideas so radical. To equate the divine with nature or to talk about the cosmic interconnectedness of all things are more or less New Age platitudes. And yet, in Spinoza’s day, these ideas challenged not only an orthodox conception of God, but the entire social and political structure that depended on the transcendent authority of the divine order.

For this reason, studying Spinoza and his life not only provides an outline of ethics as an intellectual journey, but also demonstrates how much courage it takes to formulate and then hold steadfast to new ideas.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why hard conversations matter

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

ExplainerRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2018

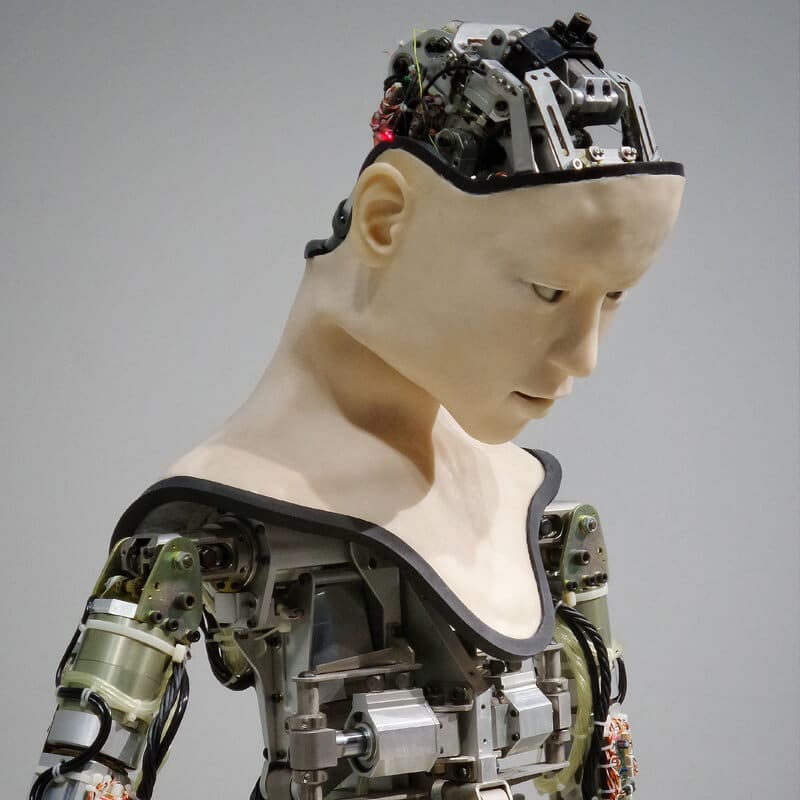

Late last year, Saudi Arabia granted a humanoid robot called Sophia citizenship. The internet went crazy about it, and a number of sensationalised reports suggested that this was the beginning of “the rise of the robots”.

In reality, though, Sophia was not a “breakthrough” in AI. She was just an elaborate puppet that could answer some simple questions. But the debate Sophia provoked about what rights robots might have in the future is a topic that is being explored by an emerging philosophical movement known as post-humanism.

From humanism to post-humanism

In order to understand what post-humanism is, it’s important to start with a definition of what it’s departing from. Humanism is a term that captures a broad range of philosophical and ethical movements that are unified by their unshakable belief in the unique value, agency, and moral supremacy of human beings.

Emerging during the Renaissance, humanism was a reaction against the superstition and religious authoritarianism of Medieval Europe. It wrested control of human destiny from the whims of a transcendent divinity and placed it in the hands of rational individuals (which, at that time, meant white men). In so doing, the humanist worldview, which still holds sway over many of our most important political and social institutions, positions humans at the centre of the moral world.

Post-humanism, which is a set of ideas that have been emerging since around the 1990s, challenges the notion that humans are and always will be the only agents of the moral world. In fact, post-humanists argue that in our technologically mediated future, understanding the world as a moral hierarchy and placing humans at the top of it will no longer make sense.

Two types of post-humanism

The best-known post-humanists, who are also sometimes referred to as transhumanists, claim that in the coming century, human beings will be radically altered by implants, bio-hacking, cognitive enhancement and other bio-medical technology. These enhancements will lead us to “evolve” into a species that is completely unrecognisable to what we are now.

This vision of the future is championed most vocally by Ray Kurzweil, a chief engineer of Google, who believes that the exponential rate of technological development will bring an end to human history as we have known it, triggering completely new ways of being that mere mortals like us cannot yet comprehend.

While this vision of the post-human appeals to Kurzweil’s Silicon Valley imagination, other post-human thinkers offer a very different perspective. Philosopher Donna Haraway, for instance, argues that the fusing of humans and technology will not physically enhance humanity, but will help us see ourselves as being interconnected rather than separate from non-human beings.

She argues that becoming cyborgs – strange assemblages of human and machine – will help us understand that the oppositions we set up between the human and non-human, natural and artificial, self and other, organic and inorganic, are merely ideas that can be broken down and renegotiated. And more than this, she thinks if we are comfortable with seeing ourselves as being part human and part machine, perhaps we will also find it easier to break down other outdated oppositions of gender, of race, of species.

Post-human ethics

So while, for Kurzweil, post-humanism describes a technological future of enhanced humanity, for Haraway, post-humanism is an ethical position that extends moral concern to things that are different from us and in particular to other species and objects with which we cohabit the world.

Our post-human future, Haraway claims, will be a time “when species meet”, and when humans finally make room for non-human things within the scope of our moral concern. A post-human ethics, therefore, encourages us to think outside of the interests of our own species, be less narcissistic in our conception of the world, and to take the interests and rights of things that are different to us seriously.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

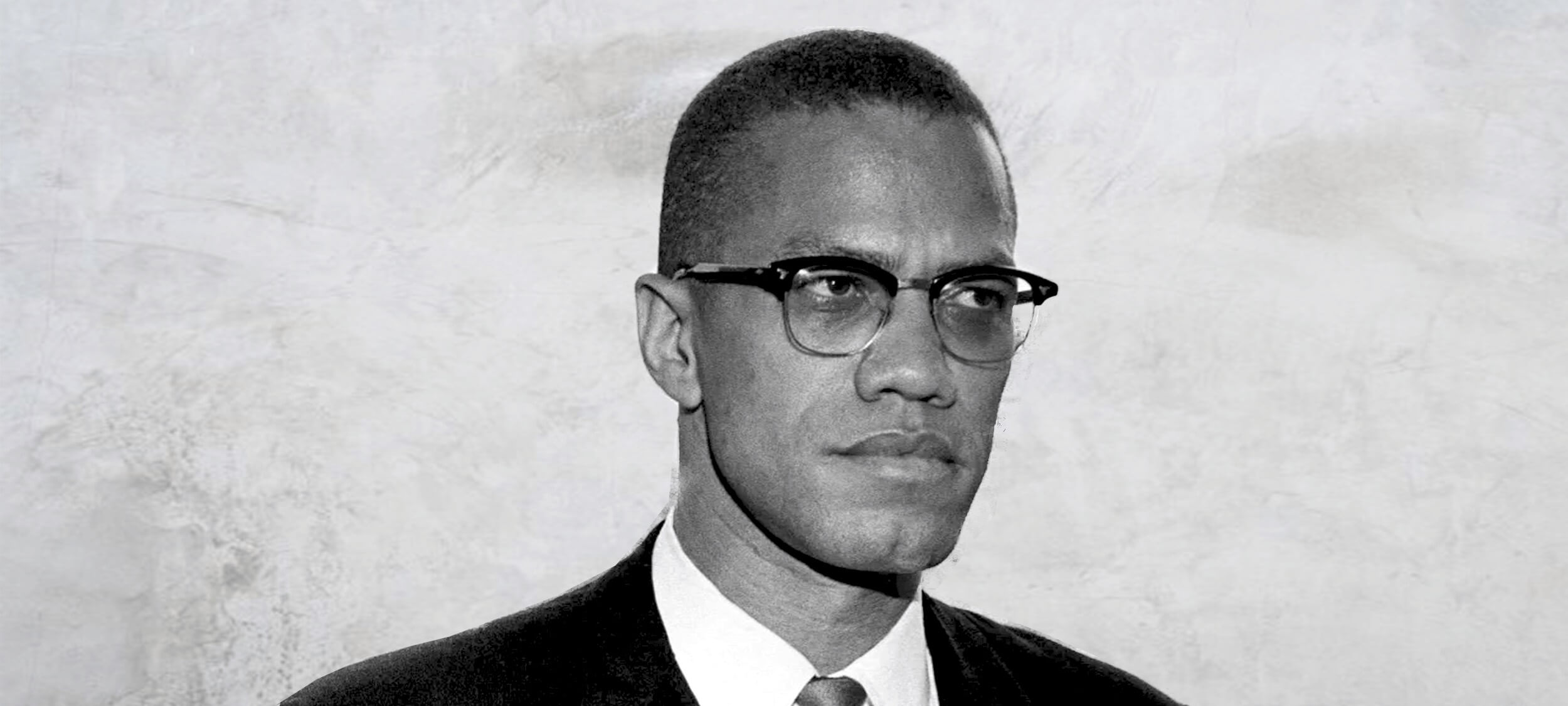

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 7 FEB 2018

Malcolm X (1925—1965) was a Muslim minister and controversial black civil rights activist.

To his admirers, he was a brave speaker of an unpalatable truth white America needed to hear. To his critics, he was a socially divisive advocate of violence. Neither will deny his impact on racial politics.

From tough childhood to influential adult

Malcolm X’s early years informed the man he became. He began life as Malcolm Little in the meatpacking town of Omaha, Nebraska before moving to Lansing, Michigan. Segregation, extreme poverty, incarceration, and violent racial protests were part of everyday life. Even lynchings, which overwhelmingly targeted black people, were still practiced when Malcolm X was born.

Malcolm X lost both parents young and lived in foster care. School, where he excelled, was cut short when he dropped out. He said a white teacher told him practicing law was “no realistic goal for a n*****”.

In the first of his many reinventions, Malcolm Little became Detroit Red, a ginger-haired New York teen hustling on the streets of Harlem. In his autobiography, Malcolm X tells of running bets and smoking weed.

He has been accused of overemphasising these more innocuous misdemeanours and concealing more nefarious crimes, such as serious drug addiction, pimping, gun running, and stealing from the very community he publicly defended.

At 20, Malcolm X landed in prison with a 10 year sentence for burglary. What might’ve been the short end to a tragic childhood became a place of metamorphosis. Detroit Red was nicknamed Satan in prison, for his bad temper, lack of faith, and preference to be alone.

He shrugged off this title and discarded his family name Little after being introduced to the Nation of Islam and its philosophies. It was, he explained, a name given to him by “the white man”. He was introduced to the prison library and he read voraciously. The influential thinker Malcolm X was born.

Upon his release, he became the spokesperson for the Nation of Islam and grew its membership from 500 to 30,000 in just over a decade. As David Remnick writes in the New Yorker, Malcolm X was “the most electrifying proponent of black nationalism alive”.

Be black and fight back

Malcolm X’s detractors did not view his idea of black power as racial equality. They saw it as pro-violent, anti-white racism in pursuit of black supremacy. But after his own life experiences and centuries of slavery and atrocities against African and Native Americans, many supported his radical voice as a necessary part of public debate. And debate he did.

Malcolm X strongly disagreed with the non-violent, integrationist approach of fellow civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. The differing philosophies of the two were widely covered in US media. Malcolm X believed neither of King’s strategies could give black people real equality because integration kept whiteness as a standard to aspire to and non-violence denied people the right of self defence. It was this take that earned him the reputation of being an advocate of violence.

“… our motto is ‘by any means necessary’.”

Malcolm X stood for black social and economic independence that you might label segregation. This looked like thriving black neighbourhoods, businesses, schools, hospitals, rehabilitation programs, rifle clubs, and literature. He proposed owning one’s blackness was the first step to real social recovery.

Unlike his peers in the civil rights movement who championed spiritual or moral solutions to racism, Malcolm X argued that wouldn’t cut it. He felt legalised and codified racial discrimination was a tangible problem, requiring structural treatment.

Malcolm X held that the issues currently facing him, his family, and his community could only be understood by studying history. He traced threads between a racist white police officer to the prison industrial complex, to lynching, slavery, and then to European colonisation.

Despite his great respect for books, Malcolm X did not accept them as “truth”. This was important because the lives of black Americans were often hugely different from what was written about – not by – them.

Every Sunday, he walked around his neighbourhood to listen to how his community was going. By coupling those conversations with his study, Malcolm X could refine and draw causes for grievances black people had long accepted – or learned to ignore.

We are human after all

Dissatisfied with their leader, Malcolm X split from the Nation of Islam (who would go on to assassinate him). This marked another transformation. He became the first reported black American to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. In his final renaming, he returned to the US as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

On his pilgrimage, he had spoken with Middle Eastern and African leaders, and according to his ‘Letter from Mecca’ (also referred to as the ‘Letter from Hajj’), began to reappraise “the white man”.

Malcolm X met white men who “were more genuinely brotherly than anyone else had ever been”. He began to understand “whiteness” to be less about colour, and more about attitudes of oppressive supremacy. He began to see colonialist parallels between his home country and those he visited in the Middle East and Africa.

Malcolm X believed there was no difference between the black man’s struggle for dignity in America and the struggle for independence from Britain in Ghana. Towards the end of his life, he spoke of the struggle for black civil rights as a struggle for human rights.

This move from civil to human rights was more than semantics. It made the issue international. Malcolm X sought to transcend the US government and directly appeal to the United Nations and Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead.

In a way, Malcolm X was promoting a form of globalisation, where the individual, rather than the nation, was on centre stage. Oppressed people took back their agency to define what equality meant, instead of governments and courts. And in doing so, he linked social revolution to human rights.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

An angry electorate

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Billionaires and the politics of envy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day and #changethedate – a tale of two truths

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 31 JAN 2018

The exposure of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein as a serial harasser and alleged rapist in October 2017 was the tipping point in an unprecedented outpouring of sexual coercion and assault disclosures.

As high profile women spoke out about the systemic misogyny of the entertainment industry, they have been joined by women around the globe using #MeToo to make visible a spectrum of experiences from the subtle humiliations of sexism to criminal violation.

The #MeToo movement has exposed not only the pervasiveness of gendered abuse but also its accommodation by the very workplaces and authorities that are supposed to ensure women’s safety. Some women (and men) have been driven to name their perpetrator via the mass media or social media, in frustration over the inaction of their employers, industries, and police. This has sparked predictable complaints about ‘witch hunts’, ‘sex panics’, and the circumvention of ‘due process’ in the criminal justice system.

Mass media and social media have a critical role in highlighting institutional failure and hypocrisy. Sexual harassment and violence are endemic precisely because the criminal justice system is failing to deter this conduct or hold perpetrators to account. The friction between the principles of due process (including the presumption of innocence) and the current spate of public accusations is symptomatic of the wholesale failure of the authorities to uphold women’s rights or take their complaints seriously.

Public allegations are one way of forcing change, and often to great effect. For instance, the recent Royal Commission into child sexual abuse was sparked by years of media pressure over clergy abuse.

While ‘trial by media’ is sometimes necessary and effective, it is far from perfect. Journalists have commercial as well as ethical reasons for pursuing stories of abuse and harassment, particularly those against celebrities, which are likely to attract a significant readership. The implements of media justice are both blunt and devastating, and in the current milieu, include serious reputational damage and potential career destruction.

The implements of media justice are both blunt and devastating.

These consequences seemed fitting for men like Weinstein, given the number, severity and consistency of the allegations against him and others. However, #MeToo has also exposed more subtle and routine forms of sexual humiliation. These are the sexual experiences that are unwanted but not illegal, occurring in ways that one partner would not choose if they were asked. These scenarios don’t necessarily involve harmful intent or threat. Instead, they are driven by the sexual scripts and stereotypes that bind men and women to patterns of sexual advance and reluctant acquiescence.

The problem is that online justice is an all-or-nothing proposition. Punishment is not dolled out proportionately or necessarily fairly. Discussions about contradictory sexual expectations and failures of communication require sensitivity and nuance, which is often lost within spontaneous hashtag movements like #MeToo. This underscores the fragile ethics of online justice movements which, while seeking to expose unethical behaviour, can perpetrate harm of their own.

The Aziz Ansari Moment

The allegations against American comedian Aziz Ansari were the first real ‘record-scratch’ moment of #MeToo. Previous accusations against figures such as Weinstein were broken by reputable outlets after careful investigation, often uncovering multiple alleged victims, many of whom were willing to be publicly named. Their stories involved gross if not criminal misconduct and exploitation. In Ansari’s case, the allegations against him were aired by the previously obscure website Babe.net, who interviewed the pseudonymous ‘Grace’ about a demeaning date with Ansari. Grace did not approach Babe with her account. Instead, Babe heard rumours about her encounter and spoke to several people in their efforts to find and interview Grace.

In the article, Grace described how her initial feelings of “excitement” at having dinner with the famous comedian changed when she accompanied him to his apartment. She felt uncomfortable with how quickly he undressed them both and initiated sexual activity. Grace expressed her discomfort to Ansari using “verbal and non-verbal cues”, which she said mostly involved “pulling away and mumbling”. They engaged in oral sex, and when Ansari pressed for intercourse, Grace declined. They spent more time talking in the apartment naked, with Ansari making sexual advances, before he suggested they put their clothes back on. After he continued to kiss and touch her, Grace said she wanted to leave, and Ansari called her a car.

In the article, Grace she had been unsure if the date was an “awkward sexual experience or sexual assault”, but she now viewed it as “sexual assault”. She emphasised how distressed she felt during her time with Ansari, and the implication of the article was that her distress should have been obvious to him. However, in response to the publication of the article, Ansari stated that that their encounter “by all indications was completely consensual” and he had been “surprised and concerned” to learn she felt otherwise.

Sexual humiliation and responsibility

Responses to Grace’s story were mixed in terms of to whom, and how, responsibility was attributed. Initial reactions on social media insisting that, if Grace felt she had been sexually assaulted, then she had been, gave way to a general consensus that Ansari was not legally responsible for what occurred in his apartment with Grace. Despite Grace’s feelings of violation, there was no description of sexual assault in the article. Even attributions of “aggression” or “coercion” seem exaggerated. Ansari appears, in Grace’s account, persistent and insensitive, but responsive to her when she was explicit about her discomfort.

A number of articles emphasised that Grace’s story was part of an important discussion about how “men are taught to wear women down to acquiescence rather than looking for an enthusiastic yes”. Such encounters may not meet the criminal standard for sexual assault, but they are still harmful and all too common.

For this reason, many believed that Ansari was morally responsible for what happened in his apartment that night. This is the much more defensible argument, and, perhaps, one that Ansari might agree with. After all, Ansari has engaged in acts of moral responsibility. When Grace contacted him via text the next day to explain that his behaviour the night before had made her “uneasy”, he apologised to her with the statement, “Clearly, I misread things in the moment and I’m truly sorry”.

However, attributing moral responsibility to Ansari for his behaviour towards Grace does not justify exposing him to the same social and professional penalties as Weinstein and other alleged serious offenders. Nor does it eclipse Babe’s responsibility for the publication of the article, including the consequences for Ansari or, indeed, for Grace, who was framed in the article as passive and unable to articulate her wants or needs to Ansari.

Discussions about contradictory sexual expectations and failures of communication require sensitivity and nuance, which is often lost within spontaneous hashtag movements like #MeToo.

For some, the apparent disproportionality between Ansari’s alleged behaviour and the reputational damage caused by Babe’s article was irrelevant. One commentator said that she won’t be “fretting about one comic’s career” because Aziz Ansari is just “collateral damage” on the path to a better future promised by #MeToo. At least in part, Ansari is attributed causal responsibility – he was one cog in a larger system of misogyny, and if he is destroyed as the system is transformed, so be it.

This position is not only morally indefensible – dismissing “collateral damage” as the cost of progress is not generally considered a principled stance – but it is unlikely to achieve its goal. A movement that dispenses with ethical judgment in the promotion of sexual ethics is essentially pulling the rug out from under itself. Furthermore, the argument is not coherent. Ansari can’t be held causally responsible for effects of a system that he, himself, is bound up within. If the causal factor is identified as the larger misogynist system, then the solution must be systemic.

Hashtag justice needs hashtag ethics

Notions of accountability and responsibility are central to the anti-violence and women’s movements. However, when we talk about holding men accountable and responsible for violence against women, we need to be specific about what this means. Much of the potency of movements like #MeToo come from the promise that at least some men will be held accountable for their misconduct, and the systems that promote and camouflage misogyny and assault will change. This is an ethical endeavour and must be underpinned by a robust ethical framework.

The Ansari moment in #MeToo raised fundamental questions not only about men’s responsibilities for sexual violence and coercion, but also about our own responsibilities responding to it. Ignoring the ethical implications of the very methods we use to denounce unethical behaviour is not only hypocritical, but fuels reactionary claims that collective struggles against sexism are neurotic and hysterical. We cannot insist on ethical transformation in sexual practices without modelling ethical practice ourselves. What we need, in effect, are ‘hashtag ethics’ – substantive ethical frameworks that underpin online social movements.

This is easier said than done. The fluidity of hashtags makes them amenable to misdirection and commodification. The pace and momentum of online justice movements can overlook relevant distinctions and conflate individual and social problems, spurred on by media outlets looking to draw clicks, eyeballs and advertising revenue. Online ethics, then, requires a critical perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of online justice. #MeToo is not an end in itself that must be defended at all costs. It’s a means to an end, and one that must be subject to ethical reflection and critique even as it is under way.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Politics + Human Rights

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

BY Michael Salter

Scientia Fellow and Associate Professor of Criminology UNSW. Board of Directors ISSTD. Specialises in complex trauma & organisedabuse.com

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia Day and #changethedate - a tale of two truths

Australia Day and #changethedate – a tale of two truths

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 JAN 2018

The recent debate about whether or not Australia Day should be celebrated on 26th January has been turned into a contest between two rival accounts of history.

On one hand, the ‘white arm band’ promotes Captain Arthur Phillip’s arrival in Port Jackson as the beginning of a generally positive story in which the European Enlightenment is transplanted to a new continent and gives rise to a peaceful, prosperous, modern nation that should be celebrated as the envy of the world.

On the other hand, the ‘black arm band’ describes the British arrival as an invasion that forcefully and unjustly dispossesses the original owners of their land and resources, ravages the world’s oldest continuous culture, and pushes to the margins those who had been proud custodians of the continent for sixty millennia.

This contest has become rich pickings for mainstream and social media where, in the name of balance, each side has been pitched against the other in a fight that assumes a binary choice between two apparently incommensurate truths.

However, what if this is not a fair representation of the what is really at stake here? What if there is truth on both sides of the argument?

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that the First Fleet brought many things. Some were good and some were not. Much that is genuinely admirable about Australia can be traced back to those British antecedents. The ‘rule of law’, the methods of science, the principle of respect for the intrinsic dignity of persons… are just a few examples of a heritage that has been both noble in its inspiration and transformative in its application in Australia.

Of course, there are dark stains in the nation’s history – most notably in relation to the treatment of Indigenous Australians. Not only were the reasonable hopes and aspirations of Indigenous people betrayed – so were the ideals of the British who had been specifically instructed to respect the interests of the Aboriginal peoples of New Holland (as the British called their foothold on the continent).

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that both accounts are true. And so is our current incapacity to realise this.

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that the arrival of the Europeans was a disaster for those already living here for generations beyond human memory. This was the same kind of disaster that befell the Britons with the arrival of the Romans, the same kind of disaster visited on the Anglo-Saxons when invaded by the Vikings and their Norman kin. Land was taken without regard for prior claims. Language was suppressed, if not destroyed. Local religions trashed. All taken – by conquest.

No reasonable person can believe the arrival of Europeans was not a disaster for Indigenous people. They fought. They lost. But they were not defeated. They survive. Some flourish. Yet with only two hundred or so years having passed since European arrival, the wounds remain.

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that both accounts are true. And so is our current incapacity to realise this. Instead we are driven by politicians and commentators and, perhaps, the temper of the times, to see the world as one of polar opposites. It is a world of winners and losers, a world where all virtue is supposed to lie on just one side of a question, a world in which we are cut by the brittle, crystalline edges of ideological certainty.

So, what are we to make of January 26th? The answer depends on what we think is to be done on this day.

One of the great skills cultivated by ethical people is the capacity for curiosity, moral imagination and reasonable doubt. Taken together, these attributes allow us to see the larger picture – the proverbial forest that is obscured by the trees. This is not an invitation to engage in some kind of relativism – in which ‘truth’ is reduced to mere opinion. Instead, it is to recognise that the truth – the whole truth – frequently has many sides and that each of them must be seen if the truth is to be known.

But first you have to look. Then you have to learn to see what might otherwise be obscured by old habits, prejudice, passion, anger… whatever your original position might have been.

So, what are we to make of January 26th? The answer depends on what we think is to be done on this day. Is it a time of reflection and self-examination? If so, then January 26th is a potent anniversary. If, on the other hand, it is meant to be a celebration of and for all Australians, then why choose a date which represents loss and suffering for so many of our fellow citizens?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil The Ethics Centre 10 JAN 2018

How had I found myself here again?

I tucked my phone away. Apart from all the fun Facebook promised me others were having, I had grown tired of reading the newest obituary of my dwindling friendships. The schoolmate: “No, not free that week.” The travel buddy: “I keep forgetting to call you!” The silent group chat, last message from a fortnight ago: “Due for a catch up?” Even the group of laughing school girls on the bus loomed over me as a promise of what I could have had. If only I wasn’t… a bad friend.

A bad friend.

The very thought made me shudder. A bad friend, that modern spectre of malice. Nice to your face while secretly gossiping about you behind your back. Undercutting your achievements with little barbs of competition. Judging you for your mistakes and holding them against you for years to come. Leaving you feeling like a used tissue. Toxic.

I floundered in denial. I wasn’t one of those! I love my friends. I send birthday messages. I text in stagnant group chats. I offer a warm, understanding, slightly anxious shoulder to lean on. I even hosted Game Night!

Besides, that’s just modern friendships. We work full time. We’re sleep deprived. We’re too poor to brunch. Flush with self righteousness, I turned back to my phone. “Missing you guys! Anyone free tonight?”

(Too short notice. Rookie mistake.)

I wouldn’t say I was primed for loneliness. I was just ready to complain about it when it happened.

After weeks of this I was in a slump. A blind spot lingered in my vision – until a wise colleague offhandedly told me that in her 23 years of marriage, she had to learn how to love. ‘I’ve gotten a lot better at it’, she assured me.

Bingo.

It was so obvious that I wanted to kick myself. Love was a verb. Just like we learn to read, write, walk, and talk, so too do we learn to love. And just like any other skill, we learn by doing – not just by thinking.

Social media didn’t help. By knowing their names, plans and volatile political opinions, I felt like I had spent time with my friends when I was making minimal effort to connect with them at all.

I had fallen prey to this. I had spent so much time thinking and complaining and ruminating and reading about friendship that it began to feel like work. Like I was doing something about it. The old adage ‘friendship takes work’ bloomed into neuroticism. And I furiously dug myself deeper into the same hole.

All of this wasn’t making me a better friend. I thought I was being patient, when I was really being avoidant. I thought I was being strong, when I was scared to ask for help. When I spoke to my friends, I masked the chatter of discontent and unfulfilled longing with carefully crafted text messages, small kindnesses, and pleasant banter. In unintentionally defining love as the balm against loneliness, I’d missed out on crucial considerations along the way. Namely:

A common purpose

Aristotle believed the greatest type of friendship was one forged between people of similar virtue who recognise and appreciate each other’s good character. To him, true happiness and fulfilment came from living a life of virtue. To have a friend who lived by this and helped you achieve the same was one of the greatest and rarest gifts of all.

A spirit of generosity

For Catholic philosopher St Thomas Aquinas, friendship was the ideal form of relationships between rational beings. Why? Because it had the greatest capacity to cultivate selflessness. Friendships let you leave your ego behind. What they love becomes equal to or greater than the things you love. Their flourishing becomes a part of your flourishing. If they’re not doing well, neither are you.

The golden rule

Imam Al-Ghazzali, a Muslim medieval philosopher, wrote friendship was the physical embodiment of treating others as you would like to be treated. In practice, “To be in your innermost heart just as you appear outwardly, so that you are truly sincere in your love for them, in private and in public”.

Knowing and being known

Philosopher Mark Vernon sees friendship as a kind of love that consists of the desire to know another and be known by them in return. This circle of requiting genuine interest and affection is perhaps one the more rewarding elements of friendships.

And most of all, these things take time.

Now, this isn’t a self-help article. I’m not going to tell you if you follow these Four Simple Steps, you too can have real friends. After all, the number of people we can count as friends, however small or large, can be a matter of luck and chance. But understanding what friendships are made of helps you grab an opportunity when it arises.

Later that week, I bit the bullet. My friends were back from overseas, and summer school hadn’t started yet. I stood down from my altar, voice raw from shouting ‘FACE TO FACE CONTACT ONLY’. I downloaded Skype, remembered my password and spent my night ironing clothes and chatting to my friends. Leaning into the ickiness of admitting I needed help with some things rewarded me with laughter, warmth, and plans to buy a 2018 planner.

As lonely and confusing as the world is, it can be even more so if we do so in the absense of good friends. Make an effort to be the friend that helps each other navigate — and avoid — the lonely confusion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Philosophy had a big moment in 20th century Europe. Christian mysticism? Not so much.

Meet Simone Weil (1909—1943) – French philosopher, political activist, Christian mystic and enfant terrible. Described by John Berger as a “heretical theologian”, Albert Camus as “the only great spirit of our times”, and André Weil (her brother) as “the greatest pain in the arse for rectors and school directors”, Weil was – and remains – one of philosophy’s more divisive characters

Uprootedness

According to Weil, post-World War II France was adrift in a deep malaise she called uprootedness. She argued France’s lack of connectedness to its past, its land, and its community had culminated in its defeat by Germany. Her solution? To find spirituality in work.

This would look different in city and country. In urban areas, treating uprootedness meant finding a motivation for work other than money.

Weil admitted that for low income and unemployed adults in war ravaged France, this would be impossible. Instead, she focused on their children. Reviving the original Tour de France, encouraging apprenticeships, and bringing joy back into study were her recommendations. This way, work could be intriguing and compelling. Even “lit up by poetry”.

For those in the country, uprootedness looked like boredom and an indifference to the land. Optional studies of science, religion, more apprenticeships and cultivating a strong need to own land was essential. To remember the water cycle, photosynthesis and Biblical shepherds while working could only invoke awe, Weil surmised. Even the fatigue of labour would turn poetic.

Her vision for reform extended to French colonialism. This was a source of deep shame for Weil, admitting that she could not meet “an Indochinese person, an Algerian, a Moroccan, without wanting to ask his forgiveness”. She saw uprootedness most acutely in those whose homelands had been invaded. It was also a clear example of the cyclical nature of uprootedness: for the fiercest invaders were uprooted people uprooting others.

Attention over will

The spirituality of academic work was just as important to Weil. In practice, this looked like attention. She defined attention as the capacity to hold different ideas without judgement. In doing so, the student would be able to engage with ideas and slowly land on an answer.

She argued that when a student is motivated by good grades or social ranking, they arrest their development of attention and lose all joy in learning. Instead, they pounce on any semblance of answer or solution, even if half-formed or incorrect, to seem impressive. Social media, anyone?

According to Weil, true knowledge could not be willed. Instead, the student should put their efforts into making sure they paid attention when it arrived.

Weil believed humanity’s search for truth was their search for nearness to God or Christ. If God or Christ was the source of ‘Truth’, every new piece of knowledge or fact learned would refer to them. Therefore, in each student’s instance of unmixed attention – to a geometry problem, a line of poetry, or a cry for help from someone in need – was an opportunity for spiritual transformation.

This detachment from social mores and movement away from the ego characterised her mysticism. It makes a lot of sense then, that Weil considered the height of attention to be prayer.

Obligations over rights

Weil believed that justice was concerned with obligations, not rights. One of her criticisms of political parties lay in their language of rights, calling it “a shrill nagging of claims and counter-claims”.

Justice, for Weil, consisted of making sure no harm is done to one another. Weil asserted that when the man who is hurt cries ‘why are you hurting me?’ he invokes the spirit of love and attention. When the second man cries ‘why has he got more than I have?’ his due becomes conditional on power and demand.

The obligation of justice, Weil noted, is fundamentally unconditional. It is eternal and based upon a duty to the very nature of humanity. In a sense, what Weil is describing is the Golden Rule, found in every major religious tradition and every strand of moral philosophy – to treat others as you would like to be treated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2017

TIME Magazine’s announcement comes amid a storm of reckoning with sexual harassment and abuse charges in power centres worldwide. The courageous victims who, over the past few months, surfaced and made public their experiences of sexual harassment have sparked a social movement – typified in the hashtag #MeToo.

One of the features of the numerous sexual harassment claims that have been made public is the number of victims that have come forward after the first allegations have surfaced. Women, many of whom have suffered in silence for a considerable period of time, all of a sudden have found their voice.

As an outsider not involved in these incidents, this pattern of behaviour might be difficult to comprehend. Surely victims would speak up and take their concerns to the appropriate authorities? Unfortunately, we are very poor at judging how we would behave when we are placed in difficult, stressful situations, as previous research has found.

How we imagine we would respond in hypothetical situations as an outsider differs significantly to how we would respond in reality – we are very poor at appreciating how the situation can influence our conduct.

In 2001, Julie Woodzicka and Marianne LaFrance asked 197 women how they would respond in a job interview if a man aged in his thirties asked them the following questions: “Do you have a boyfriend?”, “Do people find you desirable?” and “Do you think women should be required to wear bras at work?” Over two-thirds said they would refuse to answer at least one of the questions whilst sixteen of the participants said they would get up and leave.

When Woodzicka and LaFrance placed 25 women in this situation (with an actor playing the role of the interviewer), the results were vastly different. None of the women refused to answer the questions or left the interview.

In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

And there are many reasons why people remain silent. Three of the most common are fear, futility and loyalty – we fear consequences, we surmise that speaking up is futile because no action will be taken, or, as strange as it might sound, we feel a sense of loyalty to the perpetrator or our team.

There are a variety of dynamics that can cause people to reach these conclusions. The most common is power. In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

In these types of situations, it is easy to see how the victim can lose their sense of agency and feel disempowered. They might feel that even if they did speak up, nobody would believe their story. The mere thought of challenging such a “highly respected” individual is too daunting. Worse yet, their career would be irreparably damaged. Perhaps, by keeping quiet, they could get the break they need and put the experience behind them.

A second dynamic at play is what psychologists refer to as pluralistic ignorance. First conceived in the 1930s, it proposes that the silence of people within a group promotes a misguided belief of what group members are really thinking and feeling.

In the case of sexual harassment, when victims remain silent they create the illusion that the abuse is not widespread. Each victim feels they are isolated and suffering alone, further increasing the likelihood that they will repress their feelings.

By speaking out, women have shifted the norms surrounding sexual assault. Behaviour which may have been tolerated only a few years (perhaps months) ago is now out of bounds.

But as the events of the past few weeks have demonstrated, the norms promoting silence can crumble very quickly. People who suppress their feelings can find their voice as others around them break their silence. As U.S. legal scholar Cass Sunstein recently wrote in the Harvard Law Review Blog, as norms are revised, “what was once unsayable is said, and what was once unthinkable is done.”

And this is exactly what has happened over the past few months. Both perpetrators and victims alike are now reflecting on past indiscretions and questioning whether boundaries were crossed.

Only time will tell whether the shift in norms is permanent or fleeting. As is always the case with changes in social attitudes, this will be determined by a myriad of factors. The law plays a role but as the events of the past few months have demonstrated it is not as important as one might think.

Among other things, it will require the continued courage of victims. But perhaps more importantly it will require men, especially those who are in positions of power and respected members of our communities and institutions, to role model where the balance resides between extreme prudery at one end, and disgusting lechery on the other.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

An angry electorate

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big thinker

Relationships