What it means to love your country

What it means to love your country

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran 4 FEB 2026

The idea of patriotism has become increasingly contentious in Australia, particularly on January 26, with much wariness and controversy over what to call the day itself.

January 26 is a reopening of the deep wound of colonisation for many Indigenous Australians. It can also be, to a lesser extent, a confusing day to be an Australian patriot who is simultaneously ashamed of their country’s colonial past.

Australia’s colonial roots have always loomed large in its young history, but it is helpful to know that the experience of being conflicted about one’s allegiance to country is not new.

In 1943, the Jewish-heritage French philosopher Simone Weil wrote her last text dissecting the difficulty of patriotism while in WWII France. France had built its modern identity on Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality and universal human rights. Yet at Weil’s time of writing, it was actively building a colonial empire and collaborating with the German fascist state which violated these principles.

In a similar vein, modern Australia prides itself on a narrative of multiculturalism, wealth and safety, whilst also being built on the injustices of colonialism. It is increasingly suffering from fraying social cohesion as a result of this inconsistency. The controversy around January 26 is one clear recurring symptom of this.

Weil would have classified herself as a French patriot, but she was also one of its harshest critics. In her philosophy, love of country and criticism of its past are not mutually exclusive; in fact, love of country can only be authentic if it also includes honest criticism.

Patriotism in its best form is the compassionate love of one’s country and the people, communities, history and memories that comprise it.

But to Weil, this patriotism becomes maligned when it is not based in compassion, and instead entails blind allegiance to an abstract nation or symbol – something she called ‘servile love’, which she names as the ugly shadow of patriotism: nationalism.

In her vocabulary, nationalism is more extreme than loving your country; it is about engaging in idolatry and worshipping a false image of one’s country that is based on wishful thinking, rather than truth.

The wishful thinking of nationalism means making oneself ignorant through selective memory: erasing the difficulties of the past in a hurry to create a new, sanitised future. It uses boastful pride to cover up past shames.

In the same way that it is difficult to respect the integrity of an individual who is insecure about admitting their wrongs and will only assert the ways in which they are right, a nation that also cannot integrate its failings will find it hard to sustain respect.

It’s important to note that this is a collective responsibility: generational injustice requires generational reparation, and it is not possible for sole individuals to bear the whole burden of either harm or reparation for entire generations.

What makes a patriot?

In Weil’s framework, the distinction between patriotism (healthy) and nationalism (unhealthy) is ‘rootedness’, which Weil identifies as one of the deepest but most difficult to identify human needs.

A ‘rooted’ individual, community, or nation is one that is mature and connected to its history deeply enough that it has the resilience to withstand criticisms and accommodate the nurturance of many types of people.

Weil writes: “A human being is rooted through their real, active and natural participation in the life of a collectivity that keeps alive treasures of the past and has aspirations of the future.”

To Australia’s credit, there are many ways in which collective participation is healthy and available to many, which allows people from many walks of life to be rooted here.

Some often-cited reasons: being able to enjoy relative peace and comforts; fond memories of swimming at the beach or hiking nature trails (“Australia is the only country proud of its weather” – the allegations are true!); its cultural diversity. There are many patriots to whom the flag does not represent racism and exclusion, because in it they see genuine, cultivated attachments to their country. They are not focused on asserting the superiority of an identity, but on honouring a meaningful relationship with one’s community and environment – strong roots.

Yet social cohesion feels more fragile lately, partly because of the belief that the ‘rootedness’ of other communities comes at the expense of theirs. Acknowledging that bigotry and a history of colonialism still gnaw at Australia’s national identity feels like a concession or weakness to other communities – but strength can only be built from integrity rather than denial.

It is not talking about a nation’s injustices that threatens its identity, but rather, lies. Weil writes: “This entails a terrible responsibility. Because what we are talking about is recreating the country’s soul, and there is such a strong temptation to do this by dint of lies and partial truths, that it requires more heroism to insist on the truth.”

To those who have been uprooted – whether they are displaced from actual homes, felt excluded or otherised by their fellow neighbours, or felt seething hatred and even violence towards their community – it is difficult to engage with collective life when it lacks common ground built from truth.

If we accept Weil’s claim that rootedness is a fundamental human need, love and criticism of one’s country could be understood as separate species that grow from the same fertile ground: a desire to belong to and steward the country they share.

When it comes to January 26, a call to recognise it as ‘Invasion Day’ is a legitimate criticism because it is truthful to historical events. Australian patriots should not feel threatened if their love of country is deep and sincere; they should take courage that there is a way to mature the national identity in a way that is based in truth, which can allow for the roots of many to grow in its soil.

To Weil, diverse co-existence enriches a community such that “external influences [are not] an addition, but … a stimulus that makes its own life more intense.”

For any patriot, prejudice and lies are the enemy, not their own community.

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran

Marlene Jo Baquiran is a writer and activist from Western Sydney (Dharug land), Australia. Her writing focuses on culture, politics and climate, and is also featured in the book 'On This Ground: Best Australian Nature Writing'. She has worked on various climate technologies and currently runs the grassroots group 'Climate Writers' (Instagram: @climatewriters), which won the Edna Ryan Award for Community Activism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 JAN 2026

The sequence of events that led to the cancellation of Adelaide Writers Week revolve around two central questions. First, what, if any, should be the limits of free speech? Second, what, if anything, should disqualify a person from being heard? In the aftermath of the Bondi Terror Attack, the urgency in answering these questions has seen the Commonwealth Parliament recalled specifically to debate proposed legislation that will, amongst other things, redefine how the law answers such questions.

Beyond the law, what does ethics have to say about such fundamental matters in which freedom, justice and security are in obvious tension?

I have consistently argued for the following position. First, there should be a rebuttable presumption in favour of free speech. That is, our ‘default’ position is that there should be as much free speech as possible. However, I have always set two ‘boundary conditions’. First, there should be a strict prohibition against speech that calls into question or denies the intrinsic dignity and humanity of another person. Anything that implies that one person is not as fully human as another would be proscribed. This is because every human rights abuse – up to and especially including genocide – begins with the denial of the target’s humanity. It is this denial that makes it possible for people to do to others what would otherwise be inconceivable. Second, I would prohibit speech that incites violence against an individual or group.

As will be obvious, these are fairly minimal restrictions. They still leave room for people to cause offense, to harangue, to stoke prejudice, to make people feel unsafe, and so on. That is why I have come to the view that something more is needed. In the past, I have struggled to find a principle that would allow for the degree of free speech that is needed to preserve a vibrant, liberal democracy while, at the same time, limiting the harm done by those who seek to wound individuals, groups or the whole of society by means of what they say.

In particular, how do you respond to someone who foments hatred of others – but falls just short of denying their humanity?

It recently occurred to me that the principle I have been looking for can be found in the most unlikely of places: the football field. I was never any good at sport and was always the obvious ‘weak link’ in any team. So, I took a particular interest in the maxim that one should “play the ball and not the person”. Of course, the idea is not exclusively one for sport. Philosophy has long decried the validity of the ad hominem argument – where you attack the person advancing an argument rather than tackle the idea itself. Christianity teaches one to ‘loathe the sin and love the sinner’. In any case, whether one takes the idea from the football field or the list of logical fallacies or from a religion, the idea is pretty easy to ‘get’. In essence: feel free to discuss what is being done – condemn the conduct if you think this justified. However, with one possible exception, do not attack those whom you believe to be responsible.

The one possible exception relates to those in positions of power – where a decent dose of satire is never wasted. That said, the powerful can make bad decisions without being bad people – and calling their integrity into question is often cruel and unjustified. Beyond this, if powerful people preside over wrongdoing, then let the courts and tribunals hold them to account.

The ‘play the ball’ principle commends itself as a practical tool for distinguishing between what should and should not be said in a society that is trying to balance a commitment to free speech with a commitment to avoid causing harm to others. It is especially important that this curbs the tendency of ‘bad faith’ actors (especially those with power) to cultivate an association between certain ideas and certain people. For example, we see this when someone who merely questions a political, religious or cultural practice is labelled as a ‘bigot’ (or worse).

In practice, we will now explicitly apply the ‘play the ball’ principle when curating of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) – adding it to the matrix of issues we take into account when developing and presenting the program. FODI seeks to create spaces where it is ‘safe to’ encounter challenging ideas. For example, it should be possible to discuss events such as: the civic rebellion and repression in Iran, the Russian war with Ukraine, Israel’s response to Hamas’ terror attack, and so on … without attacking Iranians, Shia, Russians, Ukrainians, Israelis or Palestinians. Indeed, I think most Australians want to be able to discuss the issues – no matter how challenging – knowing that they will not be targeted, shunned or condemned for doing so.

I recognise that there are a couple of weaknesses in what I have outlined above. First, I know that some people identify so closely with an idea that they feel personally attacked even by the most sincerely directed question or comment.

Yet, in my opinion, a measure of discomfort should not be enough to silence the question. We all need to be mature enough to distinguish between challenges to our beliefs and threats to our identity.

Second, while the prohibition against the incitement of violence is clear, the other two I have proposed are much more ambiguous. As such, they might be difficult to codify in law.

Even so, these are principles that I think can be applied in practice – especially if we are all willing to think before we speak. A civil society depends on it.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

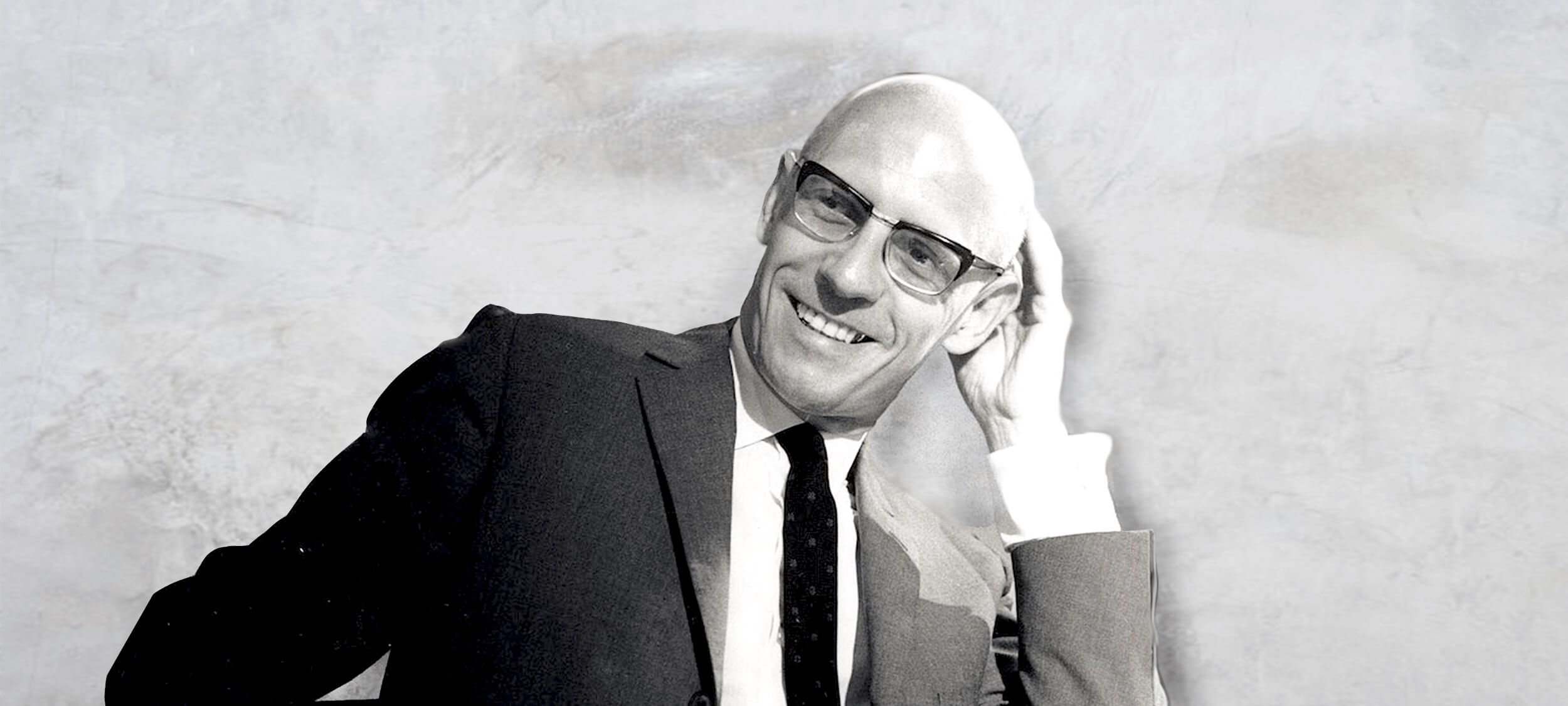

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

ExplainerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 14 JAN 2026

Ethical non-monogamy (ENM), also known as consensual non-monogamy, describes practices that involve multiple concurrent romantic and/or sexual relationships.

What it’s not

First up, it’s important to distinguish the two types of non-monogamy that are often conflated with ENM:

Polygamy, the most prominent kind of culturally institutionalised non-monogamy, is the practice of having multiple marriages. It is a historically significant practice, with hundreds of societies around the world having practiced it at some point, while many still do.

Infidelity, or non-consensual non-monogamy, is something we colloquially refer to as cheating. That is, when one or both partners in a monogamous relationship engage in various forms of intimacy outside of the relationship without the knowledge or consent of the other.

All-party consent

So, what makes ethical non-monogamy, then?

One of the defining features of ethical non-monogamy is its focus on consent.

Polygamy, while it can be consensual in theory, more often occurs alongside arranged marriages, child marriages, dowries and other practices that revoke the autonomy of women and girls. Infidelity is of course inherently non-consensual, but the reasons and ways that it happens inversely influence ENM practices.

Consent needs to be informed, voluntary and active. This means that all people involved in ENM relationships need to understand the dynamics they’re involved in, are not being emotionally or physically coerced into agreement, and are explicitly assenting to the arrangement.

Open communication

There are a multitude of ways that ENM relationships can operate, but each of them relies on a foundation of honesty and effective communication (the basis of informed consent). This often means communicating openly about things that are seen as taboo or unusual in monogamous relationships – attraction to others, romantic or sexual plans with others, feelings of jealousy, vulnerability, or inadequacy.

While all ENM relationships require this commitment to open communication and consent, there can be variation in how that looks based on the kind of relationship dynamic. They’re often broken up into broad categories of polyamory, open relationships, and relationship anarchy.

Polyamory refers to having multiple romantic relationships concurrently. Maintaining ethical polyamorous relationships involves ongoing communication with all partners to ensure that everyone understands the boundaries and expectations of each relationship. Polyamory can look like a throuple, or five people all in a relationship with each other, or one person in a relationship with three separate people, or any other number of configurations that work for the people involved.

Open relationships are focused more on the sexual aspects, where usually one primary couple will maintain the sole romantic relationship but agree to having sexual experiences outside of the relationship. While many still rely on continued communication, there is a subset of open relationships that operate on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. This usually involves consenting to seeking sexual partners outside of the relationship but agreeing to keep the details private. Swinging is also a popular form of open relationship, where monoamorous (romantically exclusive) couples have sexual relations with other couples.

Relationship anarchy rejects most conventional labels and structures, including some of the ones that polyamorous relationships sometimes rely on, like hierarchy. Instead, these relationships are based on personal agreements between each individual partner.

What all of these have in common is a firm commitment to communicating needs, expectations, boundaries and emotions in a respectful way.

These are also the hallmarks of a good monogamous relationship, but the need for them in ethical non-monogamy is compounded by the extra variables that come with multiple relationship dynamics simultaneously.

There are many other aspects of ethical relationship development that are emphasised in ethical non-monogamy but equally important and applicable to monogamous ones. These includes things like understanding and managing emotions, especially jealousy, and practicing safe sex.

Outside the relationships

Unconventional relationships are unrecognised in the law in most countries. This poses ethical challenges to current laws, including things like marriage, inheritance, hospital visitation, and adoption.

If consenting adults are in a relationship that looks different to the monogamous ones most laws are set around, is it ethical to exclude them from the benefits that they would otherwise have? Given the difficultly that monogamous queer relationships have faced and continue to face under the law in many countries, non-monogamy seems to be a long way from legal recognition. But it’s worth asking, why?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 12 JAN 2026

‘We live in a world, in the real world… that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world that have existed since the beginning of time.’ These are the words of Stephen Miller, Deputy Chief of Staff in the Trump White House, while refusing to rule out the possibility of the United States annexing Greenland.

Miller is not an isolated voice. President Trump has escalated his annexationist rhetoric about Greenland as essential to American security and has said that they will ‘take’ the Danish territory whether they ‘like it or not.’

These sentiments have a striking similarity to what the historian and general Thucydides wrote during the Peloponnesian War over two thousand years ago:

‘You know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in powers, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.’

This is the foundation of realism, a philosophy of foreign affairs. It claims that in an anarchic international system, the only rational policy for a state is to pursue its own security by having more power than its neighbours. This is because, in the absence of a world state, power is the final arbiter of disagreements between states.

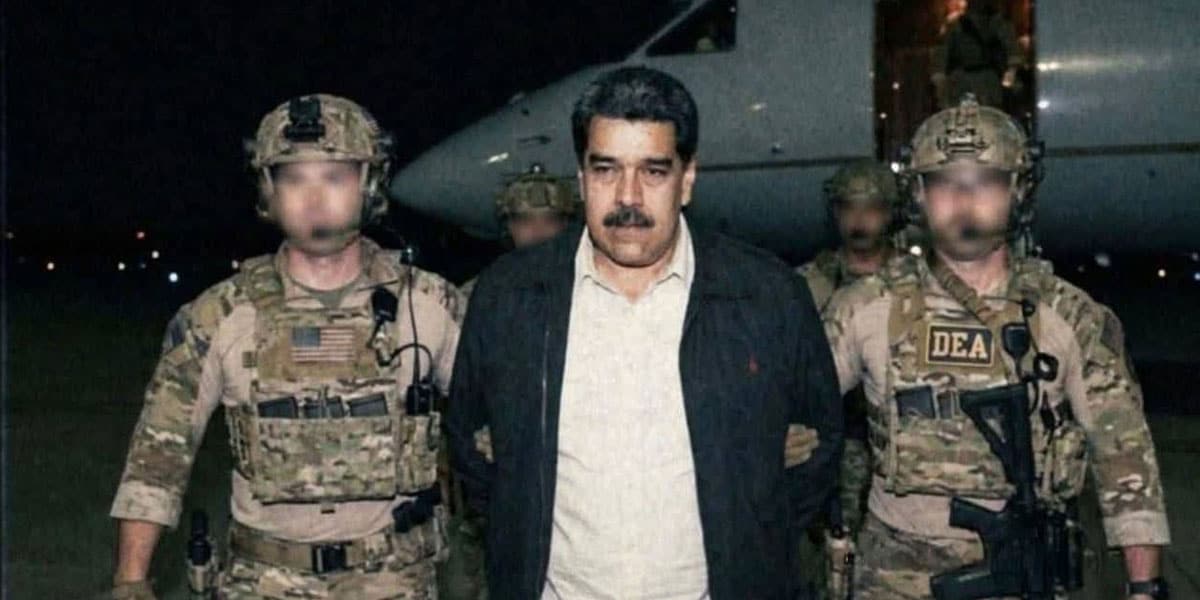

On the back of the abduction of then-Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and the Trump administration’s apparent willingness to allow Ukraine to be subsumed into a Russian sphere of influence, it seems a new realism has taken root in American foreign policy. It is one that has pushed away ethical concerns about human rights and international law and embraced pure power politics. Might makes right, and weaker countries like Venezuela, Denmark, and perhaps Canada must accept their place as mere vassals of Washington.

The problem is that Miller and Trump are not good realists.

Realism is not amoral or unethical. It has an ethical core that is practical, modest, and conservative. Realist ethics do not license something as reckless as kidnapping foreign heads of state, fracturing NATO to seize Greenland, or letting an aggressive rival menace allies. These are acts of bravado, performative and imprudent. Such actions invite unintended and unpleasant consequences.

The vulgar realism of the Trump administration would have appalled Hans Morgenthau, one of the founders of modern realism and advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Although he was attentive to power, Morgenthau never said that there was no such thing as ethics in international politics, but rather that it has a distinct set of ethics that requires a balance of power and principle. He wrote in Politics Among Nations:

‘A man who was nothing but ‘political man’ would be a beast, for he would be completely lacking in moral restraints. A man who was nothing but ‘moral man’ would be a fool, for he would be completely lacking in prudence’

Realist ethics are about survival and security in a complex, dangerous, and unpredictable world. It is wary of transcendent ideas about universal morality because of the crusader spirit they engender. Morgenthau was deeply worried that zealots on both sides of the Cold War might start a nuclear war in the name of democracy or Marxism-Leninism to the detriment of all humanity.

Likewise, the unethical bestial pursuit of power also invites disaster because it can result in a loss of the very thing it seeks to gain. Miller clearly never finished Thucydides’ The History of the Peloponnesian War (and Trump probably has no idea what it is). Athens lost the war and Sparta imposed a harsh peace. The words of the ‘Melian Dialogue’ quoted above serve to highlight the hubris of Athens. They frightened neutral states with their brutality, alienated allies with their high-handedness, and convinced of their own superiority made disastrous military adventures, such as the Sicilian Expedition, which ultimately diminished their power and prestige. In acting like Morgenthau’s beast they authored their own downfall. Hubris and tragedy are themes in the realist tradition.

The actions of the Trump administration threaten to undo the undeniable triumph of American foreign policy which was to turn the wealthy democracies of Europe into dependent but dependable allies. It invites a future where NATO has dissolved, but a rearmed, independent, and unified Europe has taken its place and that views the United States as an unreliable or even hostile power. The consequences of this shift cannot be overstated. A united Europe would have an economy five times the size of India, ten times the size of Russia, and comparable to China in nominal GDP. It would be able to check American influence, especially if it acted in concert with China. America would no longer be a hegemonic power, but simply a great power in an unstable multipolar order.

Hubris, tragedy and an object lesson on how not to be a realist.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What it means to love your country

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Daniel Finlay 8 JAN 2026

As a 16-year-old, I argued with my vegan friend about the various faults in his logic: how he couldn’t possibly be healthy, how we were meant to eat animals, and all the rest. I never could have imagined how embarrassed it would make me many years later.

I wasn’t particularly familiar with veganism as a teenager, but I have always loved animals. While the fervour to prove it wrong dissipated, my knowledge and exposure to it remained very minimal, like most people’s. A little later, I briefly dated someone who was vegetarian, who inevitably but mostly passively increased my exposure and knowledge. I decided to start looking into the validity of my confident preconceptions and realised that they were either completely unfounded or just exaggerated. It wasn’t many years later when I woke up in the middle of the night and decided that I needed to change my actions.

Veganuary

Coincidentally, 2014 was the year that I began changing my lifestyle to better reflect my values – the same year that a British nonprofit began an annual challenge called Veganuary: a call for people to try eating as if they were vegan for the first month of the year. You sign up for free and are provided with daily emails for a month that include information like recipes, cookbook pages, meal plans and general advice for how to navigate the change in habits.

All of this is well and good if you’re already curious about the idea of reducing your animal consumption, but what if you’re not? Let me try and pique your curiosity.

Why you should care

You might already consider yourself someone who cares. Most people do love animals in theory. If you see an injured bird, a run-over kangaroo, or an abused dog, you’re likely to have a compassionate response. But decades of socialisation, billions of dollars in misrepresentative marketing, and the ever-increasing distance between consumers and production means it’s easier than ever to ignore how our values contradict our everyday actions.

So please indulge me by considering the following responses to common arguments for eating animals.

To begin, let’s get the practical stuff out of the way:

Where will I get my protein? We need meat/dairy/eggs to give us all the nutrients we need.

This argument is as unfounded as it is ubiquitous, and one I wasn’t immune to earlier in my life either. Unfortunately, agricultural lobbying groups are much better at getting into the minds of average consumers, otherwise it would be common knowledge that all major dietetic associations agree on the safety (and benefits) of balanced vegan diets (and all types of vegetarian diets). That’s not to demonise the health of any other kind of balanced diet – you can be perfectly healthy on a regular omnivorous diet – but the ethical argument for showing compassion to animals doesn’t require it to be healthier than eating animals, only that it’s not bad for us. The overwhelming evidence shows that it is not.

The question is not “can I?” but “how would I like to?” That’s why something like Veganuary is such a good introduction, because having the initial support to change your shopping and eating habits makes the transition much easier.

It’s too hard.

Maintaining a balanced omnivorous diet is also too hard for most Australians – doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try! Sometimes we have to do difficult things for our own good or the good of others. You will likely find though, as I did, that the hardest part of changing your lifestyle is the social aspect. People can be judgemental, defensive, aggressive, and downright cruel despite your best attempts to minimise the impact that your choices have on others. Contrastingly, changing habits can be difficult in the short term but they soon become second nature. Staple recipes are easily replaced and substituted with similar-tasting alternatives.

Okay so maybe it won’t make my life worse personally, but it’s so bad for the environment. All those almond trees and soy crops use so much water and cause deforestation. We need animals to feed everyone.

Almond water usage obsession arose initially during the early-mid 2010s Californian droughts, where the majority of the world’s almonds are grown, at a time when almond consumption was skyrocketing. I’m not going to rush to almond’s defense, as we should definitely be prioritising mass consumption of soy and oat milk instead, but if we do want to compare it to the animal-derived alternative then almond is still better, using almost half the amount of water and causing almost five times less CO2 emissions.

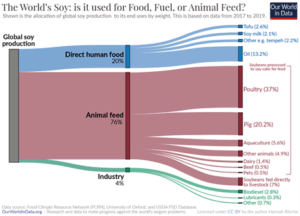

The idea that the soy used for soy milk, tofu, tempeh, etc is driving deforestation is another common myth:

“In fact, more than three-quarters (77%) of global soy is fed to livestock for meat and dairy production. Most of the rest is used for biofuels, industry, or vegetable oils. Just 7% of soy is used directly for human food products such as tofu, soy milk, edamame beans, and tempeh.”

Even further than this, the amount of land cleared for cow pastures is over 7 times that for total soy production. If you’re worried about the environment, reducing or eliminating your animal consumption is the best place to start.

I’ve heard that farming vegetables kills more animals (mice, insects, etc) than eating meat, so if we care about animals, we should really keep eating them.

As we’ve seen, most of these crops go to feeding farmed animals, which means that it is still much preferable to consume these crops ourselves, rather than producing magnitudes more to feed other animals to be killed. The same logic applies if you’re someone who would like to argue that plants have feelings, too.

If you’d like to read more about the arguments against veganism, please see here.

Starting the year right

The overarching consideration here from an ethical standpoint is to reduce unnecessary suffering. For me, this comes mainly from a consequentialist perspective. Suffering is bad, we want to see and contribute to less of it. Eating meat, dairy and eggs necessitates immense amounts of unnecessary suffering and death (even if you think killing an animal that lived a good life is okay, we cannot feed the world with that kind of production – factory farms exist to fill the demand). Therefore, we should stop contributing to that demand.

My suggestion isn’t to make a permanent change overnight, but simply to try something new. You can join millions of other people around the world who are trying out a month of reduced animal harm through Veganuary. Or maybe you’re someone who says things like “I could go vegan except I love cheese too much”. Well, use the start of this year to try being vegan except for cheese. You’ll probably find that the hardest part of doing good is taking the first uncomfortable step.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Aubrey Blanche 20 NOV 2025

In an age where emotionally charged information travels faster than ever, the ability to critically evaluate what we read, watch, and share is the cornerstone of responsible citizenship. It’s essential that we’re able to strengthen our media literacy skills to detect bias, maintain trust and safeguard the integrity of public discourse.

Since the rise of generative AI, we have become inundated with content. It’s easier to generate and disseminate information than ever before. When content is cheap, it’s curation and discernment that becomes ever more critical.

And this matters – how information travels influences policy, the bounds of acceptable discourse, and ultimately how our society functions. This means that each of us, whether a social media user, producer of a major national news program, or just someone chatting with a friend, has an obligation to ensure that the truth we share contributes to human flourishing.

What is verifiable?

The reality is that a huge amount of the information we have access to is, well, fake. Media literacy equips people to recognise bias, detect misinformation, and understand the motives behind content creation. Without these skills, we and those around us become vulnerable to manipulation, whether through sensational headlines, deepfakes, or algorithm-driven echo chambers.

Verifying information before sharing is a critical part of media literacy. Every click and share amplifies a message, whether true or false. For example, deepfakes of Scott Morrison and other politicians have been used to perpetuate investment scams. When inaccurate information spreads unchecked, it can fuel polarisation, erode trust in institutions, and even endanger lives. Taking a moment to analyse the source, check for corroboration in other trusted places, and question the credibility of a claim is a small act with enormous impact. It transforms passive consumers into active participants in a healthier information ecosystem.

Whose truth?

What we see as objective is intrinsically shaped by the voices we are exposed to, and how often. This is as true for our social media feeds as it is for the nightly news. The messages that reach us are all in some way biased, meaning that they possess some kind of embedded agenda. But what we most often mean when we talk about bias, is a systematic and repeated filtering or skewing of information to conform to a particular or narrow agenda or worldview.

Because of this, we should be wary of potential bias when issues are covered by individuals or organisations with financial or political interests at stake. For example, jurisdictions around the world are currently wrestling with questions of how training large language models (LLMs) relates to fair use of copyrighted work. In Australia, the government recently ruled out a special exception for AI models to be trained on Australian works without explicit permission or payment. While there was public consultation conducted, prominent voices didn’t all agree with protecting the labor and output of creators as a priority.

Before the federal government made the determination, powerful members of the technology industry were consulted by journalists for their views on how the interests of AI labs and creators should be considered. These voices included those whose financial holdings include investments in the type of AI companies (and their methods) being discussed. Platforming voices with these interests has important implications for setting the terms of the debate as potentially more pro-technology, rather than encouraging a balance of perspectives.

While this specific issue is critical because it’s an issue that affects all of us, it also illustrates a way that we can practice media responsibly.

When we are sharing information, we should consider the interests and ideological alignment of those who are sharing.

Where possible, we should seek to provide a balanced set of perspectives, and ideally one in which any conflicts of interest are clear and disclosed.

Who gets platformed?

There is no free marketplace of ideas. The question of what voices and perspectives are platformed and held up as truth, whether in the media or on our feeds, greatly impacts our our own narratives of events. For example, since October 2023, more than 67,000 Gazans have been killed by Israeli forces. While the genocide has received significant media coverage, the perspectives of people impacted haven’t been equitably represented in mainstream media sources. Recently, a study found that only one Palestinian guest had been booked to share their views on major US Sunday news shows (which set the national agenda) in the last 2 years. In the same period, 48 Israeli guests had been given airtime.

If we assume that Israeli guests do not have a monopoly on the truth, this pattern looks alarming. While this study didn’t speak to the views of the guests, a reasonable person would assume that such a skew in the identities and affiliations represented present a rather one-sided view of events on the ground.

In this case, the platforming also speaks to the relative power of the perspectives. Despite the Palestinian community having the greatest lived experience of harm, their voices are effectively silenced. As we consider from whom we share information, we should always consider the following questions:

- Which individuals or groups have greater access to institutions – media or otherwise – to share their experience?

- In the case of conflict, are opposing forces equally powerful (eg in terms of financial resources, alliances, etc)?

- Who is marginalised, and what is the impact of not platforming that voice?

In today’s media environment, we are flooded with information. This means that the responsibly each of us must take in our sphere of influence has increased proportionally. In order to act as responsible members of our community, we must question which voices we’re highlighting.

BY Aubrey Blanche

Aubrey Blanche is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of responsible business, finance, and technology, Blanche has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world. As Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, she leads our engagements with organisational partners looking to bring ethics to the centre of their operations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just War Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

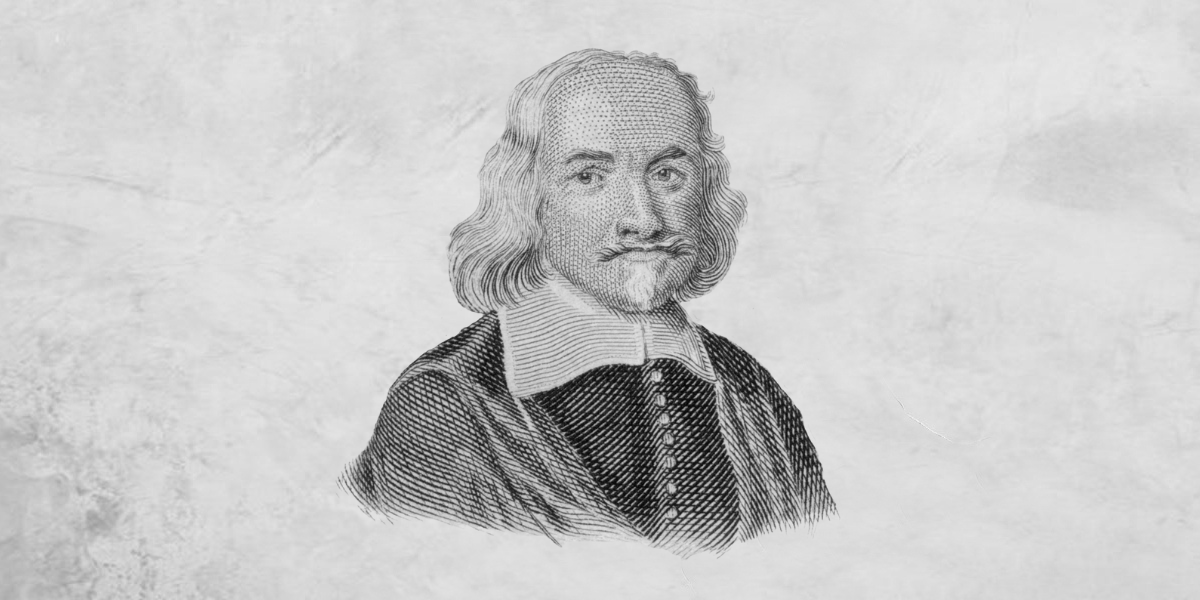

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his explanation of the role of government as an insurer of security, which has had an enduring influence on understandings of political philosophy.

Living through the displacement of the English Civil War (1642-1651), Hobbes was grappling with the question of how societies could keep peace and ensure stability, amid conflict and self-interest. The period was marked by social upheaval with the collapse of royal authority, clashes between the government and monarchy and insecurity, which led to him thinking about the manifestations of power, the human condition and the role of government.

His approach to understanding human behaviour was methodical and scientific, being deeply influenced by the scientific revolution of the time. Hobbes believed that human societies, like physical systems, could be understood through cause and effect and that understandings of order and stability were derived from the predictability of human behaviour and power structures.

The state of nature

It was from this historical and intellectual backdrop that Hobbes produced his most famous work, Leviathan (1651). His masterwork Leviathan: The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, garnered him fame for creating what would later become known as the Social Contract Theory, a framework that explains and justifies the exchange that free, equal and rational citizens make in surrendering certain freedoms in return for collective order and protection. This same contract also serves to provide legitimacy to governments and their use of power and authority over citizens.

In Leviathan and his other work, Hobbes disagrees with Aristotle that humans are naturally suited to life as citizens within a state. Hobbes instead argues that humans are not equipped to be rational citizens, as we are easily swayed, often short sighted and highly competitive. He believes these characteristics make humans more predisposed to violence and war rather than political order, with no natural self-restraint. Hobbes states that in this state of nature, without government and order, the life of man is “poor, nasty, brutish and short”, largely due to the insecurity and conflict. Everyone is free and equal, without any rules or restrictions to their actions and coupled with a self interested nature and limited resources, life in this state is a constant struggle.

The social contract

To escape this constant struggle in this state of nature, Hobbes argues that people, through reason, collectively agree to create a social contract. Hobbes believes that political order is only formed when human beings voluntarily give up some of their rights and freedoms, in exchange for order and security from a common authority, the leviathan (a ruler).

Hobbes uses the Leviathan as a metaphor for a powerful ruler or government that embodies the collective will of the people, possessing absolute authority to maintain peace and prevent society from descending back into chaos. Hobbes conception of a social contract and the role of the sovereign or leviathan, refers to these key characteristics:

- The sovereign or leviathan’s power must be absolute – only one authority, as divided power invites factionalism.

- The contract is driven by the purpose of security.

- Individuals cannot revoke the contract once it’s been made, as it would risk bringing back chaos.

- The contract is between the people and the sovereign is not party to this agreement. However, if the sovereign fails to maintain peace and security, the contract loses legitimacy and people return to the state of nature.

This framework for the social contract theory by Hobbes, was adopted by John Locke and Jean-Jaques Rousseau. However, they differed from Hobbes by offering a more optimistic view of human behaviour and the role of government. Critical responses tended to focus on a lack of accountability measures on the leviathan who has expansive absolute power. Locke for example took a liberal view, involving limited government and argued the leviathan was mutually obligated within a social contract, rather than subjects being expected to obey unconditionally to avoid the collapse of civil society.

Hobbes’s ideas continue to shape how government and authority is understood. While very few modern states reflect the vision of an absolute sovereign, the core principles of the social contract theory remain central to political thought. The consent of citizens to be governed in exchange for protection and the rule of law persists. However, in modern liberal democracies, the power of governments is placed under greater scrutiny through constitutions, elections and other checks and balances. Hobbes’s theory provides the foundation for understanding why societies form governments, even as modern democracies reinterpret his ideas to prioritise liberty, representation, and accountability alongside security and order.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lies corrupt democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Standing up against discrimination

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Mariam Sawan 11 NOV 2025

A fantastic opportunity arrived when Courage to Care NSW and The Ethics Centre launched a pivotal program for young people across our state, proudly funded by Multicultural NSW’s Compact Grant program. The focus? One of the most pressing struggles Australians continue to face or witness: discrimination.

Over three days, Year 9 and 10 students from across the Illawarra gathered at the Wollongong Youth Centre to take part in the Common Ground program. Together, we learnt not only to recognise discrimination in its many forms but also to challenge and overcome it, helping to build a community where everyone feels safe and accepted, regardless of culture, background, or ability.

Before participating in the program, I understood discrimination only as something “bad” – a simple wrong we were all taught to avoid, without ever questioning why it happens or what sustains it.

Growing up with a multicultural background, I have faced many stereotypical insults, but I never really saw them as a big deal. I knew discrimination existed, but I only saw it at face value – people saying hurtful things to make themselves feel better. Through a series of activities, case studies and creative programs, Common Ground showed me just how complex it is. While I knew discrimination could involve gender, religion, disability, and age, I had assumed it only appeared in big, obvious ways like bullying. I had not considered the smaller, everyday forms such as jokes, exclusion, or subtle assumptions. I learnt how hidden these forms of discrimination can be, shifting my mindset completely. Now I am more empathetic and aware, thinking about the meaning behind a joke rather than dismissing it and have the confidence and practical skills needed to fight what can only be described as a virus of hatred.

What stood out most was how effortlessly the organisers drew us into a topic we’d all heard about countless times before. But this time, it felt different. We were guided by “value cards” that highlighted the program’s principles, especially the three C’s: curiosity, carefulness, and courage. These sparked deep discussions about what those values meant to each of us, encouraging us to explore the issue of discrimination on a personal level.

I had previously thought curiosity was only about seeking knowledge, but the program taught me it is about listening and understanding people’s experiences without judgment. Carefulness is not just about thinking before speaking; it is also about considering how my actions affect others. Courage is having the confidence to try something new and to challenge discrimination respectfully. Hearing how other students approached these values showed me there is more than one way to make a difference and that small actions can matter just as much as big ones. My perspective changed completely.

The activities Common Ground provided were equally eye-opening. An online game showed how misinformation spreads like wildfire on social media, shaping perceptions and fuelling prejudice. Another exercise asked us to “buy privileges” for a child, using only a limited budget. The unfairness of unequal resources became painfully clear as some children could afford opportunities while others missed out. In our final group project, we created videos exploring real experiences of discrimination and brainstorming ways to combat it.

The third and final day brought together students from across the Wollongong LGA for a mix of learning, competition, and celebration. Two teams tied for the People’s Choice Award, with powerful presentations on racial and religious discrimination. The overall winners, however, tackled racial discrimination in a striking way. Their victory came with $1,000 in prize money, which they generously donated to Illawarra Multicultural Services, an organisation that supports migrants and refugees with housing, jobs, and community support.

By the end of the program, the message was clear. We, as young people, had not only learned how to recognise discrimination – even in its subtlest forms – but also how to respond with confidence, safety, and integrity.

The Common Ground program didn’t just teach us about injustice; it empowered us to become catalysts for change, fostering communities built on diversity, inclusiveness, and support.

Common Ground is a workshop program for Year 9-10 students that empowers them to stand up against discrimination. We’re taking expressions of interest for schools in South West Sydney to join this free program in Term 2, 2026. Register your school’s interest today by contacting us at learn@ethics.org.au.

BY Mariam Sawan

Mariam Sawan is a high school student who enjoys learning about how people can make a positive impact in their community and understanding people’s points of view. After participating in the Common Ground program on discrimination, she was inspired to write the article “Standing Up Against Discrimination”. Through her writing, she hopes to encourage others to treat everyone with fairness and respect and to feel empowered to speak up against injustice.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 23 SEP 2025

When I facilitate a Circle of Chairs conversation at The Ethics Centre, I always pause before starting and remind myself that I’m about to enter a potentially dangerous space. There are few domains that are as hotly contested and emotionally charged as ethics.

In this space, people might have their deepest values questioned, their most cherished views challenged, and they are likely to encounter people who hold radically different moral and political beliefs to their own.

Yet, after stepping into many Circles, I can’t think of a single time when I haven’t stepped out having witnessed a rich, deep and often challenging conversation that has left everyone feeling closer together as humans, even if they remain far apart in their views.

This is because we don’t just encourage any kind of speech in a Circle of Chairs. We do acknowledge the importance of free speech, not least because it’s our best means of challenging conventional wisdom, correcting errors and seeking the truth. But we also recognise that just protecting free speech sets a perilously low bar for the quality of discourse.

Now seems like a good time to talk about how we talk to each other. Especially so in the wake of conservative commentator, Charlie Kirk’s, assassination in the United States. That horrific event, coupled with two late night talk show hosts being taken off air in recent months, ostensibly due to comments made that have offended the Trump administration and its ideological allies, has sparked numerous conversations about the nature of good faith debate and the limits of free speech.

But if we just limit ourselves to removing speech that is directly harmful, hateful or incites violence, it still leaves a lot of room for speech that can be deceptive, offensive, divisive and dehumanising. Which is why at The Ethics Centre, we treat free speech as a baseline and add other norms on top that serve to promote constructive discourse.

These norms enable people to engage with views that are vastly different to their own – including arguing for their own perspectives and challenging those they believe are wrong – without things slipping into vitriol or worse.

I wonder if these norms might be useful when it comes to think about how we ought to speak to each other. And I stress: these are norms, not laws. They are expectations around how to behave. They’re not intended to be used to silence or punish those who fail to conform to them. They are offered as a guide for those who want to break out of the cycles of polarising and vilifying speech that we see all too often today.

Respect

The first norm is in some ways the simplest, but also the most important: respect. It states that we should always recognise others’ inherent humanity, no matter how obtuse or perverse their beliefs.

What this means is that we might choose not to say something if we think doing so will disrespect or injure their dignity as a person. We already do this in many domains of our lives. If someone has just lost a loved one, we might refrain from criticising the deceased, even if we have a genuine grievance. Likewise, we might choose not to say something we believe is true if it might dehumanise or objectify someone. As they say, “honesty without compassion is cruelty”.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strongly challenge others’ beliefs, especially if we feel they are false or harmful. Sometimes, we should do so even if it might offend them. But there’s a pragmatic element: without mutual respect, our challenges will likely fall on deaf ears, triggering defensiveness rather than encouraging openness.

Showing respect to someone you disagree with is a powerful tool to build the kind of trust that is necessary to have them actually listen to what you have to say. And the more trust and respect you build, the less chance you have of being seen to be disrespectful, and the more frank you can afford to be when you speak.

Good faith

The second norm is to always speak in good faith. This has two elements. The first is that we speak with good intention, with the aim to understand, find the truth and make the world a better place, rather than speaking to intimidate, self-aggrandise or hide an insecurity. The second element is that we speak with intellectual honesty, acknowledging our fallibility and being open to the possibility of being wrong.

We all know it’s all too easy to slip into bad faith, especially when emotions run high or we feel threatened. We might utter a barbed comment, or defend a position we don’t really understand, or we dig in our heels so we don’t look dumb. We also know what it’s like to encounter bad faith, like when you dismantle someone’s argument only to discover they haven’t changed their mind. It’s infuriating, and it can rapidly devolve a conversation into mutual bad faith attacks. You know, like what we see on social media.

Charity

The third norm is charity, which is just the flip side of good faith. Charity means we assume good faith on behalf of the person we’re speaking to rather than assuming the worst about them and their beliefs. It means filling in the blanks with the best possible version of their argument instead of jumping to attack the weakest possible version.

Charity also means giving people an on-ramp back to good faith if we do discover they are speaking in bad faith. Rather than writing them off, we try to show respect and find some mote of common ground – a shared value or belief – and build on that until we can better understand where we diverge, and talk about that.

These norms don’t guarantee all speech will be constructive. They’re not always easy to implement – especially in the unregulated wilderness of social media. But see them as being more aspirational, a kind of soft expectation that we place on ourselves and hope to demonstrate to others through the way we speak.

When we’re mindful of them, they can change conversations. I’ve seen it happen many times. I’ve seen political opponents really listen to each other and acknowledge that the other has a point. I’ve seen a climate denier and an environmental activist hug after a long conversation. I’ve seen an anti-vaxxer thank a science journalist for disagreeing without calling them names. It won’t always go like that. But in a world where we’re thrust into proximity with those we disagree with, where the threat of political violence will always hover in the wings, ready to take the stage when speech fails, I’m convinced these three norms can make a difference.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Can beggars be choosers?

As a shockingly picky child who rejected everything from unpeeled apples to mashed potatoes, I was the victim of every method of persuasion my parents tried to expand my palate — bribes of candy, hiding foods in other foods, even heartfelt pleas about starving kids hungry enough to be grateful to eat anything.

I didn’t think that last part was true — I couldn’t imagine any hunger powerful enough to overcome my disgust at seafood. While this was the naive view of a privileged seven-year-old, I later realised I was right in a different way. Not about chicken nuggets being peak cuisine, but about the idea that emotional reactions to food — often dismissed as “wants” — cannot be ignored, even for those in need. This idea is central to one of the most significant problems we face in humanitarian aid.

While hunger does make us more receptive to different foods, there are limits to this acceptance. We see this clearly in the case study of Plumpy’Nut, an incredibly powerful Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) widely used to combat malnutrition. With its calorie and nutrient-rich mixture of peanut butter, milk powder, and essential vitamins, the paste helped 95% of the Malawian children in its first six-week trial in 2001 make a full recovery, while only 25% of children treated through hospitals did. It’s still being used today, including in the Gaza famine.

However, in her book First Bite (2015), Bee Wilson reveals a different side of this otherwise miraculous invention — its reception outside of Africa. In Bangladesh, a place where 2 in 3 children live in food poverty, the sweet, sticky paste hasn’t been nearly as well-received as we might think. Out of 149 Bangladeshi caregivers, six out of ten said Plumpy’Nut was not an acceptable food, and 37% of caregivers said it made their children vomit. Many children despised the smell of the peanuts, a food foreign to Bangladeshi cuisine, while others reviled its sweetness and thick texture. This is despite 112 parents also admitting that it had helped children gain weight.

It was as if they refused to accept that this strange brown paste, so unlike food as they knew it, could satisfy a child’s hunger even despite seeing real results.

If it were true that a “really hungry” child would eat anything, then residents of Dhaka slums ought to be overjoyed to receive free packets of Plumpy’Nut. However, they were clearly not, showing that food-induced disgust is psychologically and culturally hardwired rather than a mere matter of fussiness.

Cultural beliefs persist even in extreme conditions, so we must take them into account when designing effective humanitarian aid. Even under a utilitarian worldview that prioritises physiological “needs” over “wants” in an attempt to save as many lives as possible, aid only has good consequences if it is accepted. When it incites physical revulsion, the intended benefits vanish, leaving behind not only wasted resources but also preventable lifelong medical consequences. In order to truly “feed the most people,” providers of aid are ethically obligated to ensure that it aligns with cultural expectations.

However, this example also highlights a deeper moral problem. By ranking “needs” over “wants,” we send the message that people in need don’t deserve to have their preferences or cultures considered. When we treat the defining parts of someone’s identity as secondary, we risk dehumanising them — reducing them to interchangeable bodies to be fed, instead of people with dignity. Treating aid as a one-size-fits-all endeavour also renders the recipient’s cultural context, like the Bangladeshi aversion to peanuts, an inconvenient obstacle rather than essential knowledge. This perpetuates the core power imbalance of aid: the giver defines the problem and solution, while the receiver is stripped of agency, reduced to a passive vessel for Western benevolence, resulting in a reinforcement of dependency under the guise of charity rather than any true empowerment.

As philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues in her book Creating Capabilities (2011), true wellbeing isn’t merely about fulfilling basic biological requirements like calories. It’s about expanding the substantive freedoms and capabilities people have to live lives they value, including the ability to use their senses without revulsion, to participate in cultural practices, and to make choices about their own nourishment. Forcing a child to eat something they do not culturally see as food, despite its nutritional value, actively damages this capability.

This hierarchy of needs and wants therefore doesn’t alleviate suffering holistically — it trades one form of deprivation (hunger) for another (the denial of autonomy).

Even though research has now expanded into culturally appropriate RUTFs, such as a mung bean cake called “hebi” for use in Vietnam, it is revealing that these initiatives only began after the failure of Plumpy’Nut. When it comes to for-profit enterprises targeting wealthier consumers, market research is an essential part of preparation — think KFC rice and congee in China, or the Teriyaki McBurger in Japan. We know people have different palates across the world, and usually consider it. So why assume Plumpy’Nut would succeed unchanged in both Malawi and Bangladesh, two places with completely different cuisines?

We cannot simply rely on trial and error to improve the ways we distribute humanitarian aid. To truly help people — people, not just bodies to be sustained — we must consider the full picture of their identities. Dignity is the foundation upon which effective, lasting help is built because ultimately, humanitarianism that ignores the human is a contradiction. As citizens in a world where humanitarian crises dominate headlines, understanding these dynamics matters not just for policymakers, but for anyone who donates, protests, or speaks out in response to global events.

BY Sophie Yu

Sophie Yu is a Year 12 student at Redlands, Sydney, where she studies the International Baccalaureate. She is interested in philosophy, culture, and international affairs, and explores these through the mediums of public speaking, writing and the visual arts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights