A framework for ethical AI

Artificial intelligence has untold potential to transform society for the better. It also has equal potential to cause untold harm. This is why it must be developed ethically.

Artificial intelligence is unlike any other technology humanity has developed. It will have a greater impact on society and the economy than fossil fuels, it’ll roll out faster than the internet and, at some stage, it’s likely to slip from our control and take charge of its own fate.

Unlike other technologies, AI – particularly artificial general intelligence (AGI) – is not the kind of thing that we can afford to release into the world and wait to see what happens before regulating it. That would be like genetically engineering a new virus and releasing it in the wild before knowing whether it infects people.

AI must be carefully designed with purpose, developed to be ethical and regulated responsibly. Ethics must be at the heart of this project, both in terms of how AI is developed and also how it operates.

This sentiment is the main reason why many of the world’s top AI researchers, business leaders and academics signed an open letter in March 2023 calling for “all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4”, in order to “jointly develop and implement a set of shared safety protocols for advanced AI design and development that are rigorously audited and overseen by independent outside experts”.

Some don’t think a pause goes far enough. Eliezer Yudkowsky, the lead researcher at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute has called for a complete, worldwide and indefinite moratorium on training new AI systems. He argued that the risks posed by unrestrained AI are so great that countries ought to be willing to use military action to enforce the moratorium.

It is probably impossible to enforce a pause on AI development without backing it with the threat of military action. Few nations or businesses will willingly risk falling behind in the race to commercialise AI. However, few governments are likely to be willing to go to war force them to pause.

While a pause is unlikely to happen, the ethical challenge facing humanity is that the pace of AI development is significantly faster than the pace at which we can deliberate and resolve ethical issues. The commercial and national security imperatives are also hastening the development and deployment of AI before safeguards have been put in place. The world now needs to move with urgency to put these safeguards in place.

Ethical by design

At the centre of ethics is the notion that we must take responsibility for how our actions impact the world, and we should direct our action in ways that are beneficent rather than harmful.

Likewise, if AI developers wish to be rewarded for the positive impact that AI will have on the world, such as by deriving a profit from the increased productivity afforded by the technology, then they must also accept responsibility for the negative impacts caused by AI. This is why it is in their interest (and ours) that they place ethics at the heart of AI development.

The Ethics Centre’s Ethical by Design framework can guide the development of any kind of technology to ensure it conforms to essential ethical standards.This framework should be used by those developing AI, by governments to guide AI regulation, and by the general public as a benchmark to assess whether AI conforms to the ethical standards they have every right to expect.

The framework includes eight principles:

Ought before can

This refers to the fact that just because we can do something, it doesn’t mean we should. Sometimes the most ethically responsible thing is to not do something.

If we have reasonable evidence that a particular AI technology poses an unacceptable risk, then we should cease development, or at least delay until we are confident that we can reduce or manage that risk.

We have precedent in this regard. There are bans in place around several technologies, such as human genetic modification or biological weapons that are either imposed by governments or self-imposed by researchers because they are aware they pose an unacceptable risk or would violate ethical values. There is nothing in principle stopping us from deciding to do likewise with certain AI technologies, such as those that allow the production of deep fakes, or fully autonomous AI agents.

Non-instrumentalism

Most people agree we should respect the intrinsic value of things like humans, sentient creatures, ecosystems or healthy communities, among other things, and not reduce them to mere ‘things’ to be used for the benefit of others.

So AI developers need to be mindful of how their technologies might appropriate human labour without offering compensation, as has been highlighted with some AI image generators that were trained on the work of practising artists. It also means acknowledging that job losses caused by AI have more than an economic impact and can injure the sense of meaning and purpose that people derive from their work.

If the benefits of AI come at the cost of things with intrinsic value, then we have good reason to change the way it operates or delay its rollout to ensure that the things we value can be preserved.

Self-determination

AI should give people more freedom, not less. It must be designed to operate transparently so individuals can understand how it works, how it will affect them, and then make good decisions about whether and how to use it.

Given the risk that AI could put millions of people out of work, reducing incomes and disempowering them while generating unprecedented profits for technology companies, those companies must be willing to allow governments to redistribute that new wealth fairly.

And if there is a possibility that AGI might use its own agency and power to contest ours, then the principle of self-determination suggests that we ought to delay its development until we can ensure that humans will not have their power of self-determination diminished.

Responsibility

By its nature, AI is wide-ranging in application and potent in its effects. This underscores the need for AI developers to anticipate and design for all possible use cases, even those that are not core to their vision.

Taking responsibility means developing it with an eye to reducing the possibility of these negative cases becoming a reality and mitigating against them when they’re inevitable.

Net benefit

There are few, if any, technologies that offer pure benefit without cost. Society has proven willing to adopt technologies that provide a net benefit as long as the costs are acknowledged and mitigated. One case study is the fossil fuel industry. The energy generated by fossil fuels has transformed society and improved the living conditions of billions of people worldwide. Yet once the public became aware of the cost that carbon emissions impose on the world via climate change, it demanded that emissions be reduced in order to bring the technology towards a point of net benefit over the long term.

Similarly, AI will likely offer tremendous benefits, and people might be willing to incur some high costs if the benefits are even greater. But this does not mean that AI developers can ignore the costs nor avoid taking responsibility for them.

An ethical approach means doing whatever they can to reduce the costs before they happen and mitigating them when they do, such as by working with governments to ensure there are sufficient technological safeguards against misuse and social safety nets in place should the costs rise.

Fairness

Many of the latest AI technologies have been trained on data created by humans, and they have absorbed the many biases built into that data. This has resulted in AI acting in ways that negatively discriminate against people of colour or those with disabilities. There is also a significant global disparity in access to AI and the benefits it offers. These are cases where the AI has failed the fairness test.

AI developers need to remain mindful of how their technologies might act unfairly and how the costs and benefits of AI might be distributed unfairly. Diversity and inclusion must be built into AI from the ground level through training data and methods, and AI must be continuously monitored to see if new biases emerge.

Accessibility

Given the potential benefits of AI, it must be made available to everyone, including those who might have greater barriers to access, such as those with disabilities, older populations, or people living with disadvantage or in poverty. AI has the potential to dramatically improve the lives of people in each of these categories, if it is made accessible to them.

Purpose

Purpose means being directed towards some goal or solving some problem. And that problem needs to be more than just making a profit. Many AI technologies have wide applications, and many of their uses have not even been discovered yet. But this does not mean that AI should be developed without a clear goal and simply unleased into the world to see what happens.

Purpose must be central to the development of ethical AI so that the technology is developed deliberately with human benefit in mind. Designing with purpose requires honesty and transparency at all stages, which allows people to assess whether the purpose is worthwhile and achieved ethically.

The road to ethical AI

We should continue to press for AI to be developed ethically. And if technology companies are reluctant to pay careful attention to ethics, then we should call on our governments to impose sensible regulations on them.

The goal is not to hinder AI but to ensure that it operates as intended and that the benefits flow on to the greatest possible number. AI could usher in a fourth industrial revolution. It would pay for us to make this one even more beneficial and less disruptive than the past three.

As a Knowledge Partner in the Responsible AI Network, The Ethics Centre helps provide vision and discussion about the opportunity presented by AI.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 12 APR 2023

Ahead of an automation and artificial intelligence revolution, and a possible global recession, we are sizing up ways to ‘work smarter, not harder’. Could the 4-day work week be the key to helping us adapt and thrive in the future?

As the workforce plunged into a pandemic that upended our traditional work hours, workplaces and workloads, we received the collective opportunity to question the 9-5, Monday to Friday model that has driven the global economy for the past several decades.

Workers were astounded by what they’d gained back from working remotely and with more flexible hours. Not only did the care of elderly, sick or young people become easier from the home office, but also hours that were previously spent commuting shifted to more family and personal time.

This change in where we work sparked further thought about how much time we spend working. In 2022, the largest and most successful trial of a four-day working week delivered impressive results. Some 92% of 61 UK companies who participated in a two-month trial of the shorter week declared they’d be sticking with the 100:80:100 model in what the 4 Day Week director Joe Ryle called a “major breakthrough moment” for the movement.

Momentum Mental Health chief executive officer Debbie Bailey, who participated in the study, said her team had maintained productivity and increased output. But what had stirred her more deeply was a measurable “increase in work-life balance, happiness at work, sleep per night, and a reduction in stress” among staff.

However, Bailey said, the shorter working week must remain viable for her bottom line, something she ensures through a tailor-made ‘Rules of Engagement’ in her team. “For example, if we don’t maintain 100 per cent outputs, an individual or the full team can be required to return to a 5-day week pattern,” she explained.

Beyond staff satisfaction, a successful implementation of the 4-day week model could also boost the bottom line for businesses.

Reimagining a more ethical working environment, advocates say, can yield comprehensive social benefits, including balancing gender roles, elongated lifespans, increased employee well-being, improved staff recruitment and retention and a much-needed reduction in workers’ carbon footprint as Australia works towards net-zero by 2050.

University of Queensland Business School’s associate professor Remi Ayoko says working parents with a young family will benefit the most from a modified work week, with far greater leisure time away from the keyboard offering more opportunity for travel and adventure further afield, as well as increased familial bonding and life experiences along the way.

However, similar to remote work, the 4-day working week has not been without its criticisms. Workplace connectivity is one aspect that can fall by the wayside when implementing the model – a valuable culture-building part of work, according to the University of Auckland’s Helen Delaney and Loughborough University’s Catherine Casey.

Some workers reported that “the urgency and pressure was causing “heightened stress levels,” leaving them in need of the additional day off to recover from work intensity. This raises the question of whether it is ethical for a workplace to demand a more robotic and less human-focussed performance.

In November last year, Australian staff at several of Unilever’s household names, including Dove, Rexona, Surf, Omo, TRESemmé, Continental and Streets, trialed a 100:80:100 model in the workplace. Factory workers did not take part due to union agreements.

To maintain productivity, Unilever staff were advised to cut “lesser value” activities during working hours, like superfluous meetings and the use of staff collaboration tool Microsoft Teams, in order to “free up time to work on items that matter most to the people we serve, externally and internally”.

If eyebrows were raised by that instruction, they needed only look across the ditch at Unilever New Zealand, where an 18-month trial yielded impressive results. Some 80 staff took a third (34%) fewer sick days, stress levels fell by a third (33%), and issues with work-life balance tumbled by two-thirds (67%). An independent team from the University of Technology Sydney monitored the results.

Keogh Consulting CEO Margit Mansfield told ABC Perth that she would advise business leaders considering the 4-day week to first assess the existing flexibility and autonomy arrangements in place – put simply, looking into where and when your staff actually want to work – to determine the most ethically advantageous way to shake things up.

Mansfield says focussing on redesigning jobs to suit new working environments can be a far more positive experience than retrofitting old ones with new ways. It can mean changing “the whole ecosystem around whatever the reduced hours are, because it’s not just simply, well, ‘just be as productive in four days’, and ‘you’re on five if the job is so big that it just simply cannot be done’.”

New modes of working, whether in shorter weeks or remote, are also seeing the workplace grappling with a trust revolution. On the one hand, the rise of project management software like Asana is helping managers monitor deliverables and workload in an open, transparent and ethical way, while on the other, controversial tracking software installed on work computers is causing many people, already concerned about their data privacy, to consider other workplaces.

It is important to recognise that the relationship between employer and employee is not one-sided and the reciprocation of trust is essential for creating a work environment that fosters productivity, innovation and wellbeing.

While employees now anticipate flexibility to maintain a healthy work-life balance, employers also have expectations – one of which is that employees still contribute to the culture of the organisation.

When employees are engaged and motivated they are more likely to contribute to the culture of the organisation which can inform the way the business interacts with society more broadly. Trust reciprocation is not just about meeting individual needs but also working together on a common purpose. By prioritising the well-being of their employees and empowering them to contribute to the culture of the organisation a virtuous cycle is being created. Whether this is a 4-day working week or a hybrid structure is for the employer and employee to explore.

CEO of Microsoft, Satya Nadella says forming a new world working relationship based on trust between all parties can be far more powerful for a business than building parameters around workers. After all, “people come to work for other people, not because of some policy”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Joshua Pearl 31 MAR 2023

Nothing is certain, except death and taxes. We can’t make the former fair but we can at least try when it comes to taxation.

Tax is fundamental to government. It is essential to fund the services we require to live in a modern society, including military, police, judiciary, roads, healthcare and education. It has also become more important in recent decades. At the time of Federation, the Australian tax system collected around 5% of GDP. Today this number stands at around 29%.

But is it fair? Are we paying too little or too much tax? Should those with greater means pay more? These are questions that must be asked of any tax system, and two works by philosophers offer very different answers.

The first is Robert Nozick’s Anarchy State and Utopia. It argues that individuals (and, by extension, the corporations they own) ought to own 100% of their income. Individual property rights are paramount, and any taxation beyond what is required to protect borders and protect these property rights is unjust. In short: only public expenditure on the police and military can be justified.

One of Nozick’s more colourful claims is that taxation is on par with forced labour. Tax forces workers to work in part for themselves, and in part for government.

But while Anarchy State and Utopia is a cult favourite of many modern-styled libertarians arguing for lower taxes, most people consider its position on tax unfair. Many find the consequences of the gross inequalities Nozick permits objectionable, while others argue a child’s right to public education, or a citizen’s right to universal healthcare, outweighs the right individuals or corporations have to their pre-tax wealth and income.

An additional issue for Nozick is how to determine who funds the military and police. Should it be a fee for service? And if so, does this mean only the very wealthy who pay tax should enforce property rights, given they have the most to benefit and lose without military and police? Or should everyone pay an equal amount of tax, regardless of their income or wealth or their ability to pay? (The fallout of this was seen in the 1990’s in the UK when a Thatcher Government head tax proposal was met with violence and riots in the street).

The other side of the tax coin

The second perspective comes from Thomas Nagel and Liam Murphy in their book The Myth of Ownership. They tackle the definition of tax fairness in a nearly opposite way to Nozick. They argue that it does not make sense that citizens have full (or any) rights to their pre-tax income and wealth because income and wealth cannot exist without government. Individual and corporate incomes, and the level of incomes, occur because of the existence of government, not despite it.

They have a point. A successful Australian economy requires the enforcement of law, market regulation, monetary policy (not least for the currency we use), and regulation that prohibits collusion, intimidation and other forms of business malpractice. A banker earns money because the government has mandated a currency – and she keeps her money because property rights exist. A lawyer’s income occurs because of the legal system, not despite it. We might also argue that a successful Australian economy requires investments in public education and public healthcare.

Yet, while individual and corporate income may be contingent on the existence of government, and markets might not be considered perfectly fair nor free, it doesn’t follow that market determined outcomes are completely arbitrary. We often say that someone deserves to earn more if they work harder. So if someone decides to go to university or undertake a trade, rather than surf all day, we might think they deserve a higher salary.

This very simple point (not to mention the very real practical issues with discarding market-based outcomes) mean Nagel and Murphy, like Nozick, fail to provide a complete blueprint for us to determine tax fairness. Nozick fails because he assumes market distributions are 100% fair; Nagel and Murphy fail because they assume market distributions (and any and all inputs that determine these distributions such as hard work and effort) are irrelevant.

And yet both philosophies help us focus on important tax fairness elements. Nagel and Murphy show it is important to focus on people’s post-tax positions and effectively highlight that pre-tax market determined income and wealth are not necessarily “fair”, largely because these incomes and wealth cannot exist without tax and government. Nozick effectively highlights that income and corporate tax can only be justified if associated government expenditure can also be justified.

Even if you find that neither of these perspectives to be the right one, they help establish the parameters of a fair tax system. It’s then up to us to inject our values to determine which system is right for the kind of society we wish to live in.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

LISTEN

Business + Leadership

Leading With Purpose

BY Joshua Pearl

Joshua Pearl is the head of Energy Transition at Iberdrola Australia. Josh has previously worked in government and political and corporate advisory. Josh studied economics and finance at the University of New South Wales and philosophy and economics at the London School of Economics.

How far should you go for what you believe in?

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Cameryn Cass 28 MAR 2023

Do we all have a right to protest? And does it count if it doesn’t result in radical change? Grappling with its many faces and forms, philosopher Dr Tim Dean, and human rights lawyer and chair of Amnesty International UK, Dr Senthorun (Sen) Raj unpack what it means to ethically protest in our modern society.

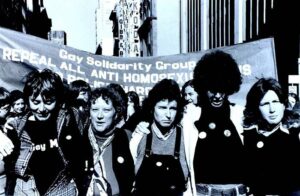

In the wake of 2023 World Pride and Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, Raj and Dean reflect on a fundamental question present in all protest: What is it you’re protesting?

The first challenge is in agreeing on what the problem is: Is it freedom we’re fighting for? Equal rights? Sustainability? From there, you’ve got to expose the fault to enough people who are motivated to join in on the resistance.

“We can hope for a better future, but is it enough to just hope?” – Sen Raj

Even if a protest is small in numbers, it can be lasting in impact; just consider Sydney’s first Mardi Gras. It was a relatively modest event that’s now grown to nearly 12,500 marchers and 300,000 spectators. But it began with a fraction of those numbers. Late in the evening on 24 June 1978, a group marched toward Hyde Park with a small stereo system and banners decorating the back of a single flat-bed truck, like a scaled-down parade float. The march intentionally coincided with anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall riots, which remains a symbol of resistance and solidarity among the gay and lesbian community. As the night progressed, police confiscated the truck and sound system. Eventually, 53 people were charged – despite having a permit to march – after they fought back in response to the police violence. To this, Ken Davis, who helped lead the march, said, “The police attack made us more determined to run Mardi Gras the next year.”

“Protest” has multiple meanings

A meaningful protest doesn’t have to be major like Mardi Gras. Sometimes, protests by brave individuals alone have extraordinary impacts.

Thích Quảng Đức, a Mahayana Buddhist monk, famously burned himself to death at a busy intersection in Vietnam on 11 June 1963. In the height of the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam, Quảng Đức performed this self-immolation to protest Buddhist persecution. The harrowing photo of him calmly seated while burning alive touched all corners of the globe and inspired similar acts of sacrifice in the name of religious freedom.

Protests need not be so drastic, though, to have an impact. On 16 December 1965, a group of American students protested the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands with peace signs on them to school. When administrators told the students to remove the bands and they refused, they were sent home. Backed by their families, the Iowa school’s barring of student protest reached the Supreme Court. The famed Tinker v. Des Moines decision held that students don’t “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Tinker case is proof that protests, no matter how minor, can give rise to reformation. But we shouldn’t enter all protests with an expectation of radical change. Dean and Raj agree the assumption that transformation is the mark of a successful protest ought to be re-examined, as a clear outcome isn’t the only metric of success. As Raj said, “There is a tendency at times to assume that a protest will have a very clear message – a defined endpoint or outcome.”

Though progress might prove slow, it’s progress, nonetheless. We should act with the intention of spreading a message and entering a larger conversation that may or may not modify the status quo. Does a protest count for nothing if it doesn’t result in sweeping change? Is it not enough to ignite the spirit of defiance in just one soul? Or to simply express your authentic self even if it has no impact?

“For me, being queer, being trans, being part of a community that is marginalised and stigmatised for who you are or what you do, in itself, is a form of protest.” – Sen Raj

For members of the LGBTQIA+ community, Raj highlights how, “by virtue of existing, these individuals are being policed.” He says, “For me, being queer, being trans, being part of a community that is marginalised and stigmatised for who you are or what you do, in itself, is a form of protest.” So by refusing to conform and loving who they want, not holding themselves to gender or sexual norms, LGBTQIA+ people protest every day. It’s not a large mass gathering, but it’s a kind of protest, nonetheless. Authentic expression begets liberation; we ought not trivialise the importance of any protest, big or small, as it takes real courage to take part in something larger than yourself.

Does violence have a place in protests?

Just as protests can manifest in many forms, they can also be carried out differently.

Because tragedy and injustice are what usually catalyse protests, they’re often charged with strong – and sometimes overwhelmingly negative – emotions. It’s no surprise, then, that some protests turn violent.

But is violence ever permissible in a protest? And if police instigate it, do protesters have a right to protect themselves?

During the racial tensions in 1960s America, many protests ended in violence, especially by police. Images capture the savage behaviour in Birmingham, Alabama, where police unleashed high-powered hoses and dogs on Black protesters. In spite of such violence, they had no space to defend themselves; fighting back meant certain arrest. As Dean and Raj detailed in the discussion, sometimes authorities use this tendency towards self-defence to provoke violence and thus justify further oppression. Race riots persist in America as the fight against systematic racism and police brutality continues. The Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), founded in 2013 and popularised after a policeman wrongfully killed George Floyd in 2020, continues the fight for Black rights.

The fragility of protesting

The right to protest isn’t guaranteed and must be protected. In the absence of protest, the government and other institutions could operate unchallenged.

In Hong Kong, China enacted a new national security law in 2020 that’s a major barrier to protesting. Already, hundreds of protesters have been arrested. On paper, the law protects against terrorism and subversion, but in practice, it criminalises dissent. In the absence of protest, the powerful can ignore and silence the concerns of the masses. If a system is broken, binding together and protesting is an essential step in fixing it. Without protests, a broken system will remain broken.

“That’s what gives rise to protests, is that refusal. That refusal to allow for social or political worlds that oppress you to continue unchecked, and to say ‘Enough’.” – Sen Raj

Anti-protest laws aren’t a uniquely Hong Kong phenomenon. In April 2022, the New South Wales government passed more stringent legislation that punishes both protests and protesters that illegally dissent on public land. By blocking protests that prevent economic activity, critics say it’s an extremely undemocratic measure and threatens protests at large. Plus, it creates a hierarchy among protests, where some are viewed as valid while others aren’t. This raises the larger question of whether it’s the government’s place to determine which protests should be allowed. Does asking permission to protest do an injustice to the demonstration?

A way forward

It’s important to note that there’s no one way to protest. The textbook protest of a group of angry, fed-up citizens waving signs and shouting in the streets doesn’t always hold true. And so we’ve got to remember that protest need not look a certain way or foster radical change to be successful. It need not be a grandiose display of floats and intricate costumes parading down Oxford Street, like today’s Mardi Gras; sometimes it’s enough for one person to speak their mind.

Raj reminds us that protest ought to be messy, joyous and painful but should include care, respect and solidarity. He encourages us to abandon the stereotypical depiction of protest and embrace the possibility of many protests. It’s limiting to try and definitively define what it means. “Protest” is encapsulating of so many movements, minor and mammoth. Instead of trying to box it into one definition, let’s find beauty in its vastness.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

BY Cameryn Cass

Cameryn Cass is a curious writer and an editor-in-training who studied at Michigan State University. Her primary focus is environmental storytelling, as she deeply loves the natural world and intends to use her voice to defend it. Outside of work, she loves to hike, rock climb and practice yoga.

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 21 MAR 2023

Parental leave policies are designed to support and protect working parents. However, we need to exercise greater imagination when it comes to the roles of women, family and care if we are to promote greater social equity.

In October 2022, prime minister Anthony Albanese announced a major reform to Australia’s paid parental leave scheme, making it more flexible for parents and extending the period that it covers. Labor’s reforms are undoubtedly an improvement over the existing scheme, which has been insufficient to address gender-based disadvantage.

Labor’s new arrangement builds on the current Parental Leave Pay (PLP) scheme. This entitles a primary carer – usually the mother – to 18 weeks paid leave at the national minimum wage, along with any parental leave offered by their employer. It runs in parallel to the Dad and Partner Pay scheme, which offers “eligible working dads and partners” two weeks paid leave at the minimum wage. Recipients of this scheme are required to be employed and recipients of both need to be earning less than ~$156,000 annually.

Albanese’s announced expansion of the PLP will increase it to 26 weeks paid leave by 2026, which can be shared between carers if they wish. Labor claims that this will offer parents greater flexibility while retaining continuity with the existing scheme.

Labor’s new scheme is an improvement over the older arrangement, but is it enough to move society closer to the goal of social equity? To do so, we need to do more to reduce the marginalisation of women economically, in the home and in the workplace, and to expand our imagination when it comes to parenthood and caring responsibilities.

Uneven playing field

Gender-based disadvantage is a global occurrence. Currently, being a woman acts as a reliable determining factor of that person’s social, health and economic disadvantage throughout their life. Paid parental schemes are one type of governmental policy that can facilitate and encourage the structural reform necessary to address gender-based disadvantage. Certain parental leave policies can help reconfigure conceptions about parenting, family and work in ways that better align with a country’s goals and attitudes surrounding both gender equity and economic participation.

Paid parental leave schemes that provide adequate leave periods, pay rates, and encourage shared caring patterns across households, can fundamentally impact the degree to which one’s gender acts a significant determining factor of their opportunities and wellbeing across their lifetime.

The Parenthood, an Australian not-for-profit, emphasises that motherhood acts as a penalty against women, children and their families. This penalty is experienced acutely by women who have children and manifests as diminished health and economic security, reducing women’s social capacity to achieve shared gender equity goals. Their research highlights that countries that offer higher levels of maternity and paternity leave, such as Germany, in combination with access to affordable childcare results in higher lifetime earnings and work participation rates for women.

Australia’s existing PLP scheme, on the other hand, works to both create and foster conditions that reduce the capacity for women to achieve the same social and economic security as their male peers. It hugely limits women’s capacity to return to work, to remain at home, and to freely negotiate alternative patterns of care with their partners. This in combination with a growing casualised workforce who remain unable to access adequate employer support emphasises the need for extensive policy amendments if we hope to realise our goals of social equity.

Labour’s proposed expansion incrementally begins to better align the PLP with the goals set forth by organisations like The Parenthood.

Providing women and their families with more freedom to independently determine their work and social structures may mark the beginning of a positive move against gender-based disadvantage. However, the proposed expansion is not a cure-all for a society that remains wedded to particular conceptions of women, parenting, and labour more broadly.

The working rights of mothers

We can see how disadvantage goes beyond parental leave by looking at how mothers are treated in workplaces such as universities. Dr Talia Morag at the University of Wollongong advocates for the working rights of mothers employed within her university. Prior to Albanese’s announcement, Morag emphasised the cultural resistance, or rather a lack of imagination, when it came to merging the concept of motherhood with an academic career.

Class scheduling, travel funding and networking capacities are all important features of an academic career that require attention and reconfiguration if mothers, especially of infants and young children, are to be sufficiently included and afforded equal capacities to succeed in university settings.

Even under expanded PLP schemes, mothers who breastfeed, for example, face difficulty when returning to work if they remain unsupported and marginalised in those workplaces. As Morag emphasises, many casual or early-career academic staff are unentitled to receive government PLP or university funded parental leave.

Critically, the associations between being woman and being taken to be an impediment to one’s workplace is not an issue faced solely by those who become mothers.

As Morag remarks, “it does not matter if you are or are not going to be a mother, you will be labelled as a potential mother for most of your career. And that will come with expectations and discrimination.”

The gender-based disadvantage emergent from these cultural associations will remain if broader cultural change is not sought alongside expanded PLP schemes.

Expanding our imaginations as to how current notions of motherhood, family and caring patterns can look will require the combined efforts of expanded PLP schemes and the creation of more hospitable working environments for parents. Women may remain being seen as potential mothers and potential liabilities to places of work, however this liability may slowly begin to shift.

We historically have, and seemingly remain, committed to reproducing our species. This means we continue to produce little people who grow up to experience pleasure, pain, and everything in between. If we also see ourselves as committed to managing some of that pain, to expanding the opportunities these little people get, as well as reducing how gender unfairly determines opportunity on their behalf, we will require policies that assist parents to do so.

Affording families this chance benefits not only mothers, or parents, but also their children, their children’s children, and all others in our communities. Granting parents the capacity to choose who works where and when can help us, incrementally, along a long path to a world that is perhaps more dynamic and equitable than we can even begin to envision.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Thought experiment: "Chinese room" argument

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

ExplainerScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 10 MAR 2023

If a computer responds to questions in an intelligent way, does that mean it is genuinely intelligent?

Since its release to the public in November 2022, ChatGPT has taken the world by storm. Anyone can log in, ask a series of questions, and receive very detailed and reasonable responses.

Given the startling clarity of the responses, the fluidity of the language and the speed of the response, it is easy to assume that ChatGPT “understands” what it’s reporting back. The very language used by ChatGPT, and the way it types out each word individually, reinforces the feeling that we are “chatting” with another intelligent being.

But this raises the question of whether ChatGPT, or any other large language model (LLM) like it, is genuinely capable of “understanding” anything, at least in the way that humans do. This is where a thought experiment concocted in the 1980s becomes especially relevant today.

“The Chinese room”

Imagine you’re a monolingual native English speaker sitting in a small windowless room surrounded by filing cabinets with drawers filled with cards, each featuring one or more Chinese characters. You also have a book of detailed instructions written in English on how to manipulate those cards.

Given you’re a native English speaker with no understanding of Chinese, the only thing that will make sense to you will be the book of instructions.

Now imagine that someone outside the room slips a series of Chinese characters under the door. You look in the book and find instructions telling you what to do if you see that very series of characters. The instructions culminate by having you pick out another series of Chinese characters and slide them back under the door.

You have no idea what the characters mean but they make perfect sense to the native Chinese speaker on the outside. In fact, the series of characters they originally slid under the door formed a question and the characters you returned formed a perfectly reasonable response. To the native Chinese speaker outside, it looks, for all intents and purposes, like the person inside the room understands Chinese. Yet you have no such understanding.

This is the “Chinese room” thought experiment proposed by the philosopher John Searle in 1980 to challenge the idea that a computer that simply follows a program can have a genuine understanding of what it is saying. Because Searle was American, he chose Chinese for his thought experiment. But the experiment would equally apply to a monolingual Chinese speaker being given cards written in English or a Spanish speaker given cards written in Cherokee, and so on.

Functionalism and Strong AI

Philosophers have long debated what it means to have a mind that is capable of having mental states, like thoughts or feelings. One view that was particularly popular in the late 20th century was called “functionalism”.

Functionalism states that a mental state is not defined by how it’s produced, such as requiring that it must be the product of a brain in action. It is also not defined by what it feels like, such as requiring that pain have a particular unpleasant sensation. Instead, functionalism says that a mental state is defined by what it does.

This means that if something produces the same aversive response that pain does in us, even if it is done by a computer rather than a brain, then it is just as much a mental state as it is when a human experiences pain.

Functionalism is related to a view that Searle called “Strong AI”. This view says that if we produce a computer that behaves and responds to stimuli in exactly the same way that a human would, then we should consider that computer to have genuine mental states. “Weak AI”, on the other hand, simply claims that all such a computer is doing is simulating mental states.

Searle offered the Chinese room thought experiment to show that being able to answer a question intelligently is not sufficient to prove Strong AI. It could be that the computer is functionally proficient in speaking Chinese without actually understanding Chinese.

ChatGPT room

While the Chinese room remained a much-debated thought experiment in philosophy for over 40 years, today we can all see the experiment made real whenever we log into Chat GPT. Large language models like ChatGPT are the Chinese room argument made real. They are incredibly sophisticated versions of the filing cabinet, reflecting the corpus of text upon which they’re trained, and the instructions, representing the probabilities used to decide how to pick which character or word to display next.

So even if we feel that ChatGPT – or a future more capable LLM – understands what it’s saying, if we believe that the person in the Chinese room doesn’t understand Chinese, and that LLMs operate in much the same way as the Chinese room, then we must conclude that it doesn’t really understand what it’s saying.

This observation has relevance for ethical considerations as well. If we believe that genuine ethical action requires the actor to have certain mental states, like intentions or beliefs, or that ethics requires the individual to possess certain virtues, like integrity or honesty – then we might conclude that a LLM is incapable of being genuinely ethical if it lacks these things.

A LLM might still be able to express ethical statements and follow prescribed ethical guidelines imposed by its creators – as has been the case in the creators of ChatGPT limiting its responses around sensitive topics such as racism, violence and self-harm – but even if it looks like it has its own ethical beliefs and convictions, that could be an illusion similar to the Chinese room.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2023

In a world where some women still struggle to have their voices heard, there are many female thinkers whose contributions throughout history have impacted our thinking today. This International Women’s Day, we’re celebrating five influential Australian philosophers, activists, academics and thinkers who have shaped our ethical landscape and beyond.

Kate Manne

Kate Manne (1983-present) is an Australian philosopher best known for her feminist, moral and social philosophies, and her work around misogyny and masculine entitlement. Notably, instead of thinking of misogyny as hatred for women, Manne redefines the word and focuses on its systematic nature, specifically in how law enforcement polices women and girls to uphold gender norms.

To illustrate masculine entitlement, Manne coined the term “himpathy”, which explains “the disproportionate … sympathy extended to a male perpetrator over his … less privileged, female targets in cases of sexual assault, harassment, and other misogynistic behaviour.” She took a deep dive into this idea in her 2020 book Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women and critiqued Justice Kavanaugh’s appointment to the US Supreme Court, despite allegations of sexual assault, as “himpathy” in action.

Marcia Langton

Marcia Langton (1951-present) is considered one of Australia’s top academics, anthropologists and geographers. As the great–great–granddaughter of survivors of the frontier massacres and a Yiman person, Langton uses her influential platform to advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. When her great aunt Celia Smith, an organiser of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, convinced her to work with the council in 1967, Langton was launched into her outspoken career of Aboriginal activism.

Since, she’s worked on vital pieces of research and legislation impacting Indigenous people and has held the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at University of Melbourne since 2000. More recently, she’s worked on the Voice to Parliament that would recognise First Peoples in the Constitution, permitting them “to have a say in the legislation that affects their lives.” To her, upholding Indigenous knowledge and rights goes beyond environmental preservation: It’s cultural preservation.

Veena Sahajwalla

Veena Sahajwalla (undisclosed-present) is an Australian scientist, inventor and professor. Named one of Australia’s 100 most influential engineers in 2015 and one of the 100 most innovative in 2016, Sahajwalla is putting New South Wales on a path to a net zero carbon, circular economy. Nicknamed “Queen of Waste”, she’s worked to repurpose everything from old clothes to beer bottles and abandoned mattresses. Growing up in Mumbai, India, she was introduced to the art of recycling through waste-pickers.

Her most famous invention, “Green Steel”, replaces coking coal in steel production with old, shredded tyres. The process is much less carbon-intensive and prevents 2 million tyres from hitting the landfill each year. This, in addition to her numerous other achievements – such as being councillor on the Australian Climate Council and opening the world’s first e-waste microfactory on the University of New South Wales’s campus – led to her being named Australian of the Year in 2022

Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (1939-present) is a writer and regarded one of the major voices of the radical feminism movement in the latter half of the 20th century. Born in Melbourne, her 1970 book, The Female Eunuch, made her a household name where she argued the expectation for women to be feminine – in the clothes they wear, in marriage, in having a nuclear family – is what represses them. And so she calls for liberation, for revolution, because this repression cultivates political inaction.

Since then, she’s written several other books on feminism, literature and the environment. Of all her ideas and claims, she holds that freedom is the most dangerous, though critics say otherwise. Some of Greer’s views of have created controversy, including her views on gender binaries and expressions, rape and the #MeToo movement. While her audacious language, beliefs and controversy have cultivated furore at times, Greer remains a prominent participant in intellectual discourse and debate.

Val Plumwood

Val Plumwood (1939-2008) was an Australian philosopher, activist and ecofeminist. Her work focused on anthropocentrism and discouraging the idea that humans are superior to and separate from nature. This “standpoint of mastery”, as she called it, legitimised the “othering” of the natural world, which included women, indigenous and non-humans.

She experienced a major paradigm shift that coloured her opposition to anthropocentrism after she was attacked by a crocodile while canoeing alone at Kakadu National Park. She couldn’t believe such a thing was happening to her, a human. She went from being top of the food chain to part of it, having “no more significance than any other edible being.” To Plumwood, the flawed mindset of only human life mattering is the root of our planet’s degradation. She proposed nurturing the natural world for nature’s own good instead of our own, famously questioning, “Is there a need for a new, an environmental, ethic – an ethic of nature?”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 MAR 2023

The undead are everywhere. It’s not just that our culture is obsessed with zombies, from The Walking Dead to The Last Of Us. It’s that our cultural discussions are zombies themselves – they just won’t die.

We go over the same old arguments time and time again, to no seeming progression or end. Just take the cultural discussions around depiction and endorsement where the lines have been drawn in the sand.

For those on one side of the line – the instigators of this particular debate – artists who depict monstrous acts are seen to be agreeing with these acts. The mere depiction of violence, for instance, is seen as a kind of thumbs up to that violence, tacitly encouraging it.

On this view, artists are moral arbiters, and the images and stories that they put out into the world have a significant, behaviour-altering effect. Depicting criminals means “normalising” criminals, which means that more viewers will believe that criminal acts are acceptable, and, theoretically, start doing them.

This view has a historical precedent. Art has long been political, used by states and religious groups in order to provide a form of moral instruction – consider devotional Christian paintings, which are designed to exhort viewers to better behaviour.

Certainly, there are still artists and artworks with a pointedly ethical and political mode of instruction. From government PSAs that borrow storytelling techniques that artists have used for years, to the glut of Christian-funded films like God Is Real, art objects have been designed as transmission devices for a particular point of ethical view. Even Captain Marvel, another in a seemingly unending glut of superhero movies, was created in partnership with the airforce, and depicts the military in a childishly positive light.

But acting as though all art has this moral framework – that everything is a form of fable, with a clear ethical message – is a mistake. Moreover, it elevates a discussion about art beyond what we usually think of as aesthetic principles, and into political ones. It’s not just that the instigators who view all art as essentially and simply instructional worry we’re getting worse art. It’s that they worry we’re getting more dangerous art.

In just the last 12 months, Martin Scorsese has been condemned at least three times in some circles of the internet for glorifying depravity with his films about criminal underbellies.

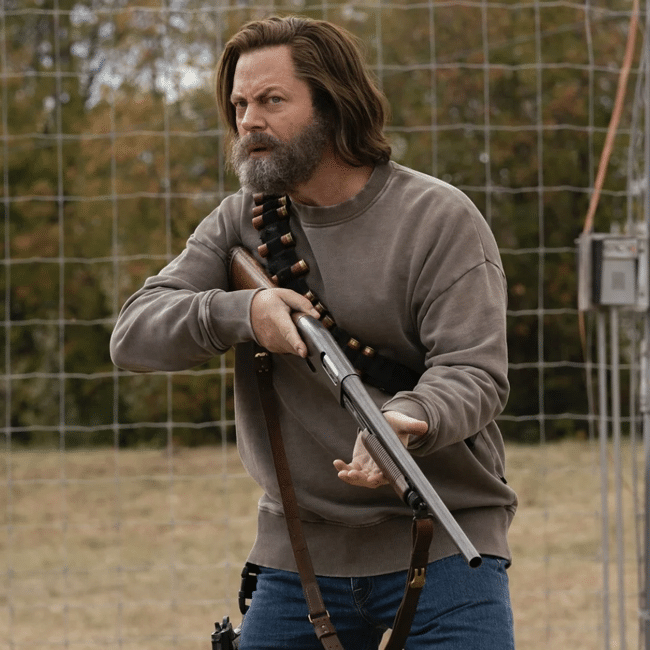

But the argument really saw its time in a sun that won’t set with the release of the bottleneck episode of The Last of Us, a much heralded – and deeply contentious – piece of television.

Fungal Zombies And Queer Representation

In the episode, Parks and Recreation’s Nick Offerman and The White Lotus’ Murray Bartlett embark upon a queer romance while the world ends around them. Though highlighted for its sensitivity in some corners of the discourse, the episode received significant pushback.

For writer Merryana Salem of Junkee, the episode was an example of “pinkwashing”, due to the fact that the characters value “individual liberty over community good.” As in – they try to survive during an apocalypse. Salem criticises the show for depicting queer characters looting and pillaging, rather than sharing resources. By aligning queer representation with selfish behaviour, Salem appears to be arguing that the show will platform and perhaps normalise libertarian values of the self as important above all others.

“Far from framing this attitude as negative, a song plays cheerily over Bill hoarding, looting resources, and setting up security systems that would prevent anyone in the immediate area from even using the electricity in the local plant”, Salem writes.

The argument here is simple. One act is shown onscreen instead of another. That is a choice. The choice, combined with the aesthetics around it – cheery music – means that this choice is designed to impress upon the audience the admirable nature of the character, even as he does less than admirable things.

What such an argument precludes, however, is the complexity inherent in the episode. The Last of Us’ showrunner, Craig Mazin, may not be pointing at good and bad as directly as his critics assume. Bill is a man trying to carve out love and life under impossible circumstances. In an ideal world, he wouldn’t be hoarding resources. In an ideal world, he would be living quietly, in a community. He doesn’t want to make do in the middle of a zombie outbreak.

The beauty of the episode, then, is the way it makes a case for the power of an easy love formed under uneasy circumstances. Bill’s flawed because he’s been made that way by an outbreak of, ya know, fungus zombies. And yet still he finds some crooked form of redemption in the arms of another.

That’s what is missing from so many of these debates about depiction versus endorsement – nuance.

Good storytellers don’t depict flatly. They depict with complexity. With differing shades of light and dark. And so their art should be analysed on those merits, with criticism that is itself complex.

But more than that, we need to ask ourselves, finally, whether depicting reprehensible acts onscreen really has the effect that these critics assume it does.

The Return Of The Big Bad

Take some of the most reprehensible people on television. Walter White of Breaking Bad. Tony Soprano of The Sopranos. Even Don Draper of Mad Men. These men, who washed over our screens during the start of the Golden Age of Television, do bad things.

More than that, they get rewarded for them. Tony is lavished with success of all forms – money, power, opportunity. Walter finds, through drug-dealing, a new level of self-confidence and authority. Don never gets a traditional comeuppance, unless you take the constant unease in his soul as a form of comeuppance.

These characters are explicitly rewarded – in some ways – for their immorality. They get away with it. Even Tony, whose fate is hinted at but never explicitly shown, gets a moment of peace before he goes. Don’s sitting there with a big old grin on his face the last time we see him. And sure, Walter gets snuffed out, but on his own vicious terms.

And so what? Are any of the creators behind these anti-heroes really suggesting that we should turn to crime or adultery? If they are, then they are not artists – they are salesmen.

Art is better when we treat it as nuanced, complex depictions that leave it to us to do the work of untangling.

Indeed, through immorality, these characters suggest that the only thing worse than these flawed and difficult characters is the world around them – the world that rewards them. It’s not Don that’s the isolated problem, cutting a swathe of heartbreak and cashing a big old cheque. It’s that the structure around him is misogynistic and capitalistic. He is the perfect product of his era. And the depiction of his moral crimes isn’t meant to encourage us to applaud those crimes. It’s meant – at least on one interpretation – to make us question the whole system that props us up.

It’s a mistake to hanker for art that only operates in one moral mode; that punishes the wicked, and celebrates the innocent. Not even fairy tales are that simplistic. We live in an era in which even our zombie TV shows are filled with nuance and complexity. Let’s engage in discourse worthy of that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What it means to love your country

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Donation? More like dump nation

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY Amal Awad 27 FEB 2023

In the desire to clean up our living and mental spaces, we need not create a costly mess for charitable organisations receiving our donations.

Several years ago when I was producing for radio, I found myself knee-deep in the topic of minimalism. I was fascinated by the concept: living with a minimal number of possessions, replacing rather than accumulating, being ‘timeless’ rather than at the mercy of trends. At the forefront of the movement were Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, aka The Minimalists, whom The New Yorker called ‘Sincere prophets of anti-consumerism’. They rose to fame with documentaries, a podcast and a best-selling book, all of which promoted this ‘minimalist lifestyle’.

A minimalist approach does not preclude you from purchasing the latest smartphone, it resists desiring that smartphone, which, like most on-trend technology, will either get superseded by a newer version within a year, or break the moment its two-year warranty has expired. (Remember your childhood TV that worked for 17 years?)

I interviewed Nicodemus and easily understood how his austere approach to housekeeping might have its appeal. What would it be like to not be weighed down by your possessions? To actually derive full use out of what you already owned? To simply not want the newest shiny thing?

At the heart of this approach is a mental philosophy that fuels a mindset, not just a way of life. Being a minimalist will mean you’re not part of the problem in what seems to be an ever-expanding consumerist wasteland. You’re better for the environment because you don’t accumulate. You’re not someone who, in the process of divesting yourself of unneeded possessions, overloads your local op shop because you have five different versions of a favourite item.

While the ability to not accumulate possessions may be harder to achieve for most people, as each new year rolls in with the proclamation of a ‘New Year, New Me’, we tend to become minimalists.

In a fever, we rule out bad habits and embrace healthy ones. Invariably, this involves some level of decluttering because we acknowledge that we are wasting money on things we don’t need.

And this is why it’s not uncommon to drive past a Vinnie’s in January and see half-opened bags of donations strewn across the pavement.

That ardent desire to strip away the baggage in our lives ends up becoming someone else’s problem when we dump donations, rather than engaging with charitable organisations and op-shops directly.

Unfortunately, this is a cumbersome, costly problem for the charitable organisations receiving these donations. Rather than an orderly, well-packed offering of useable items, charities are reporting the prevalence of irresponsible offloading of unusable items. As Tory Shepherd reported for The Guardian, “Australian charities are forking out millions of dollars to deal with donation ‘dumping’ at the same time that they are seeing rising demand for their services ‘as the cost-of-living crisis bites’”.

Not for the first time, we are seeing op shops plead with their local communities to not dump and run, leaving behind what is often rubbish, or items that the shop cannot accommodate, such as furniture. Following Covid lockdowns, we saw a similar phenomenon as people took stock of their lives and possessions—and left it to charities to take care of their unwanted items. The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and Charitable Recycling Australia are pushing this message of responsible donating.

As a deeply consumerist society, we’re at the mercy of goods that are not built to last.

There is a need for donations; organisations like Vinnies are clearly welcoming of reusable, recyclable goods that can be repurposed. However, instead of owning the act of throwing something away, we might pass on the responsibility by giving it away and making it a charitable act. There are deeply-felt financial and practical impacts on these organisations when they have to clean up the mess of people who don’t take the time to sort through their possessions, or who are careless in how they deliver their donations. The resounding advice is that if it’s something you’d give to a friend, it’s suitable for a donation.

Not everyone can afford goods made of recyclable or sustainable material. But we can try to create a new way forward. We can reconsider our approach to ownership and divestment; buy what we need and try to purchase higher quality, sustainable goods whenever possible. We can also appeal to businesses to enact more sustainable practices. We can lobby local councils and government.

In the meantime, while it’s a positive that we don’t want to just throw things out, it does not take much to do a stocktake before offering up donations: is what am I giving away something I would give to someone I care about? Is it in working order? For large items, check with your op shop or organisation before delivering them. Don’t leave items in front of a closed shopfront. Don’t treat charities like a garbage dump.

There is tidying a la Marie Kondo but then there is medically-reviewed physical decluttering that research suggests is good for our mental health. Even digital decluttering can have a positive impact on our productivity. But it’s worth considering, when we divest ourselves of unwanted goods, whether we are making sustainable donations or trashing items simply to upgrade.

If we can accept that decluttering is good for us, does that not also suggest that having cleaner spaces with fewer possessions is a better way to live? Perhaps a more worthy and sustainable goal is to take some cues from the minimalist mindset. I’m all for annual purges but even better would be to not need to declutter in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Being a little bit better can make a huge difference to our mental health

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 17 FEB 2023

On July 9, 1900, Royal Assent was given to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. This act made provision for a series of sovereign colonial states to come together and form “one indissoluble federal commonwealth”. Section 6 of the act defines the states. It lists by name an initial seven colonies – and allows for others to be admitted at a later time.

“Hang on,” you might object, “everyone knows that there were, and are, only six states. What’s this nonsense about there being a seventh?”

Well, the framers of the Constitution wanted to recognise all of the smaller sovereign states that might make up the larger whole. So, the list included New Zealand. Indeed, when in 1902 the Commonwealth Parliament determined who could vote in federal elections, it singled out New Zealand’s Maori people for inclusion – while excluding the vast majority of Australia’s own Indigenous peoples.

This is breathtaking.

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the proposed referendum about the Voice to Parliament, then consider this.

Those who put together the Constitution never finished the job. They left out those with the greatest claim to sovereignty of all.

Now we have the chance to finish the job – to make our Constitution whole.

We are on the cusp of resolving one of the most profound questions we face as citizens: will we afford constitutional recognition to the descendants of those First Nations peoples whose sovereignty was ignored by the European colonists?

A number of arguments have been put forward as reasons to oppose constitutional recognition of First Nations peoples in the form of a Voice to Parliament. Those arguments include that a Voice:

- Weakens First Nations’ claims to sovereignty.

- Will not lead to a tangible improvement in the lives of Indigenous peoples.

- Is “racist” and undemocratic in that it affords a privilege to one “race” over all others.

- Will increase legal uncertainty – especially when interpreting the Constitution.

In every case, framing the debate in terms of sovereignty helps us to see why these objections, while sincerely made, are not well founded.

It is feared, by some, that constitutional recognition will weaken the claims to sovereignty made by First Nations peoples. However, the Australian Constitution specifically preserves the sovereignty of each of the states that were recognised at Federation. Furthermore, all of their state laws remain intact. The only effect of the Constitution is to render state laws inoperative to the extent that they are inconsistent with valid Commonwealth legislation. Rather than destroying sovereignty, the Constitution recognises and preserves it – even as earlier laws become attenuated.

It might be objected that the First Nations of pre-colonial Australia were not “sovereign states”. However, they meet all of the accepted criteria. They may have been small – but size of territory or population does not matter (think of Monaco, Liechtenstein, Tuvalu and so on – all states). The First Nations had clearly defined borders. They had distinct laws – and processes for their enforcement. They traded – domestically and internationally (for example, centuries of trade between the Makassan people of modern Indonesia and the Anindilyakwa people of the Groote Eylandt archipelago, and others). They fought wars over people and resources and to defend their territory. All of this was anticipated by British law and policy. It was only blind ignorance and prejudice that stopped the colonists recognising the sophisticated array of states they encountered here.

A second objection is that constitutional recognition will do little or nothing to “close the gap”. Surely, Indigenous peoples have a far better idea of what is needed to address the enduring legacies of colonisation than do the rest of us. Certainly, they could not do a worse job than we have so far. So, I believe a Voice to Parliament will make a positive difference in the material circumstances of First Nations peoples. However, while important, this misses the point.

Imagine someone heading out into remote Queensland in 1899 – to tell the people living there that remaining as a crown colony might lead to better outcomes in the future. There would have been a riot in response to the suggestion that Queensland should be left a colony while the rest of the colonial states formed a federation. Even the West Australians decided to join – not because Federation guaranteed a better outcome for the people of each state, but because of the dignity it conferred on citizens of the newly established nation. It’s the same for those forgotten or ignored when the first round of Constitutional crafting was done.

The next “bad” argument claims that the creation of a Voice confers a benefit on one group of people because of their “race” – and that to do so is racist and undemocratic. Once again, the argument fails to take account of First Nations peoples as members of sovereign states. Those states existed – certainly in Natural Law (and probably more formally) for centuries prior to colonisation. The citizens of those states were exclusively Indigenous – not as a matter of racial policy but as a simple fact of history. The same would have been true of other ancient states in other parts of the world which, at one time or another, would have been made up of groups of people related through kinship and so on.

So, if we see our late recognition of the peoples of the First Nations through the lens of sovereignty and citizenship, there is necessarily going to be overlap between that citizenship and membership of a distinct group of related people.

This is not about privileging one “race” over another. It is simply acknowledging the fact that the citizens of the First Nations that we hope to recognise are all bound by a kinship grounded in deep history.

Finally, we come to the argument that an amendment to the Constitution will cause legal uncertainty – with the High Court spending wasted hours in interpreting the new provisions of an amended Constitution. If this is a valid reason for not amending the Constitution, then it is better that we should not have had a Constitution at all. Every clause in the Constitution of 1900 is open to interpretation by the High Court. Indeed, the High Court has spent a vast amount of time interpreting provisions (especially concerning the valid powers of the commonwealth). So, yes, an amendment might lead to disputes in the Federal and High Court. So what? That happens every day in relation to sections of the Constitution that are more or less taken for granted.

Finally, I am happy to see a decreasing number of people are arguing that the voice will be a “third chamber” of parliament. It will not. The Voice will be able to make representations and to advise – using whatever mechanisms the Commonwealth Parliament prescribes. The Voice will decide nothing on its own. It cannot veto any act of parliament or decision of government.

First Nations peoples have asked for something very modest. They want to be recognised. They simply want to be heard in relation to matters that have a direct bearing on their lives.

Our Constitution is a pretty good document. However, its authors left something out. While recognising the sovereignty of all others (even Fiji was in the mix for a while), they overlooked those with the best claim of all.

Imagine a fence made without a gate, a car without brakes and a cake without icing. They’ll work well enough. But they’re not complete. That’s the deficiency in our Constitution – it also works well enough, but it is not complete.

Let’s recognise what was forgotten. Let’s finish the job.

This article was first published in The Australian.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy