Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Oscar Schwartz The Ethics Centre 19 FEB 2018

Uncannily specific ads target you every single day. With the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’, you get a peek at the algorithm that decides it. Oscar Schwartz explains why that’s more complicated than it sounds.

If you’re an EU resident, you will now be entitled to ask Netflix how the algorithm decided to recommend you The Crown instead of Stranger Things. Or, more significantly, you will be able to question the logic behind why a money lending algorithm denied you credit for a home loan.

This is because of a new regulation known as “the right to an explanation”. Part of the General Data Protection Regulation that has come into effect in May 2018, this regulation states users are entitled to ask for an explanation about how algorithms make decisions. This way, they can challenge the decision made or make an informed choice to opt out.

Supporters of this regulation argue that it will foster transparency and accountability in the way companies use AI. Detractors argue the regulation misunderstands how cutting-edge automated decision making works and is likely to hold back technological progress. Specifically, some have argued the right to an explanation is incompatible with machine learning, as the complexity of this technology makes it very difficult to explain precisely how the algorithms do what they do.

As such, there is an emerging tension between the right to an explanation and useful applications of machine learning techniques. This tension suggests a deeper ethical question: Is the right to understand how complex technology works more important than the potential benefits of inherently inexplicable algorithms? Would it be justifiable to curtail research and development in, say, cancer detecting software if we couldn’t provide a coherent explanation for how the algorithm operates?

The limits of human comprehension

This negotiation between the limits of human understanding and technological progress has been present since the first decades of AI research. In 1958, Hannah Arendt was thinking about intelligent machines and came to the conclusion that the limits of what can be understood in language might, in fact, provide a useful moral limit for what our technology should do.

In the prologue to The Human Condition she argues that modern science and technology has become so complex that its “truths” can no longer be spoken of coherently. “We do not yet know whether this situation is final,” she writes, “but it could be that we, who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do”.

Arendt feared that if we gave up our capacity to comprehend technology, we would become “thoughtless creatures at the mercy of every gadget which is technically possible, no matter how murderous it is”.

While pioneering AI researcher Joseph Weizenbaum agreed with Arendt that technology requires moral limitation, he felt that she didn’t take her argument far enough. In his 1976 book, Computer Power and Human Reason, he argues that even if we are given explanations of how technology works, seemingly intelligent yet simple software can still create “powerful delusional thinking in otherwise normal people”. He learnt this first hand after creating an algorithm called ELIZA, which was programmed to work like a therapist.

While ELIZA was a simple program, Weizenbaum found that people willingly created emotional bonds with the machine. In fact, even when he explained the limited ways in which the algorithm worked, people still maintained that it had understood them on an emotional level. This led Weizenbaum to suggest that simply explaining how technology works is not enough of a limitation on AI. In the end, he argued that when a decision requires human judgement, machines ought not be deferred to.

While Weizenbuam spent the rest of his career highlighting the dangers of AI, many of his peers and colleagues believed that his humanist moralism would lead to repressive limitations on scientific freedom and progress. For instance, John McCarthy, another pioneer of AI research, reviewed Weizenbaum’s book, and countered it by suggesting overregulating technological developments goes against the spirit of pure science. Regulation of innovation and scientific freedom, McCarthy adds, is usually only achieved “in an atmosphere that combines public hysteria and bureaucratic power”.

Where we are now

Decades have passed since these first debates about human understanding and computer power took place. We are only now starting to see them breach the realms of philosophy and play out in the real world. AI is being rolled out in more and more high stakes domains as you read. Of course, our modern world is filled with complex systems that we do not fully understand. Do you know exactly how the plumbing, electricity, or waste disposal that you rely on works? We have become used to depending on systems and technology that we do not yet understand.

But if you wanted to, you could come to understand many of these systems and technologies by speaking to experts. You could invite an electrician over to your home tomorrow and ask them to explain how the lights turn on.

Yet, the complex workings of machine learning means that in the near future, this might no longer be the case. It might be possible to have a TV show recommended to you or your essay marked by a computer and for there to be no-one, not even the creator of the algorithm, to explain precisely why or how things happened the way they happened.

The European Union have taken a moral stance against this vision of the future. In so doing, they have aligned themselves, morally speaking, with Hannah Arendt, enshrining a law that makes the limited scope of our “earth-bound” comprehension a limit for technological progress.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

BY Oscar Schwartz

Oscar Schwartz is a freelance writer and researcher based in New York. He is interested in how technology interacts with identity formation. Previously, he was a doctoral researcher at Monash University, where he earned a PhD for a thesis about the history of machines that write literature.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

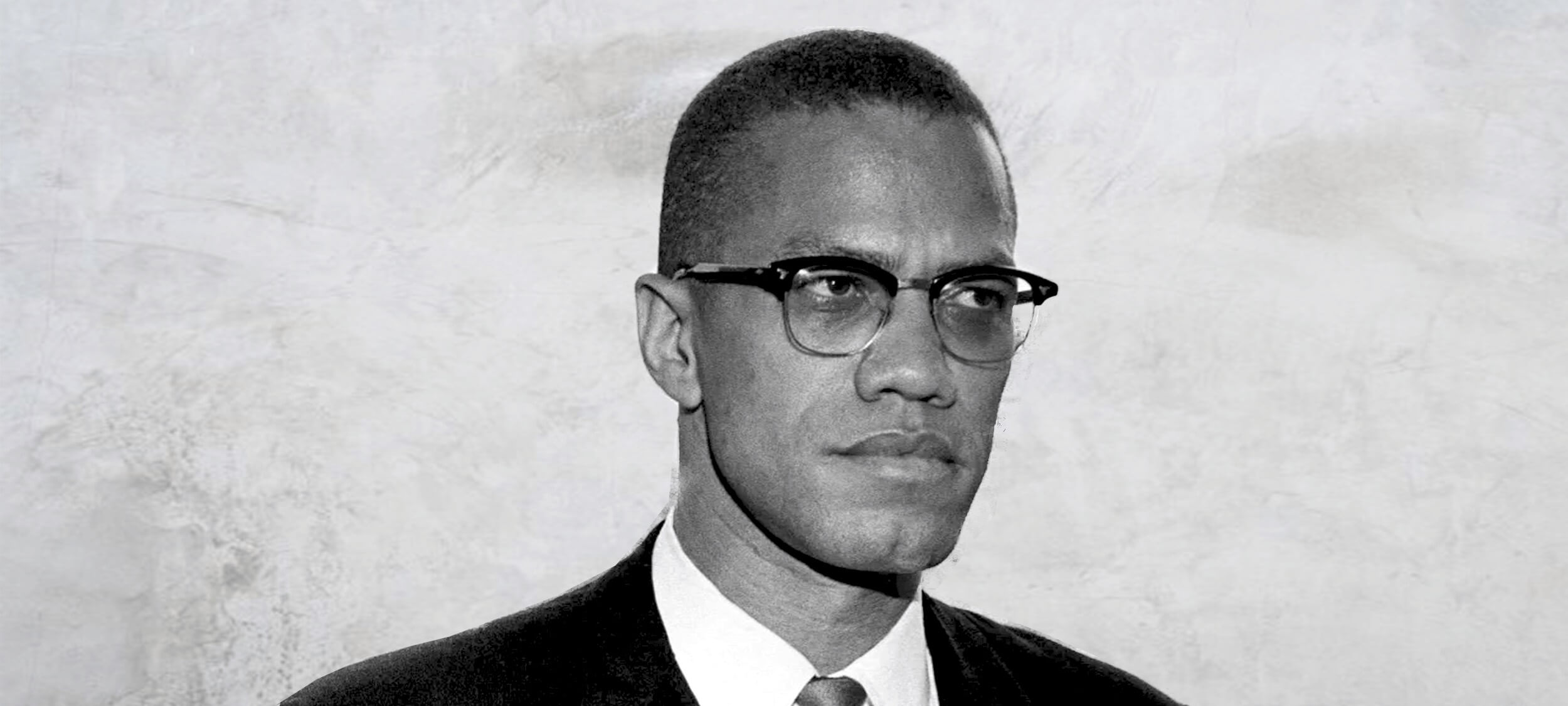

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 7 FEB 2018

Malcolm X (1925—1965) was a Muslim minister and controversial black civil rights activist.

To his admirers, he was a brave speaker of an unpalatable truth white America needed to hear. To his critics, he was a socially divisive advocate of violence. Neither will deny his impact on racial politics.

From tough childhood to influential adult

Malcolm X’s early years informed the man he became. He began life as Malcolm Little in the meatpacking town of Omaha, Nebraska before moving to Lansing, Michigan. Segregation, extreme poverty, incarceration, and violent racial protests were part of everyday life. Even lynchings, which overwhelmingly targeted black people, were still practiced when Malcolm X was born.

Malcolm X lost both parents young and lived in foster care. School, where he excelled, was cut short when he dropped out. He said a white teacher told him practicing law was “no realistic goal for a n*****”.

In the first of his many reinventions, Malcolm Little became Detroit Red, a ginger-haired New York teen hustling on the streets of Harlem. In his autobiography, Malcolm X tells of running bets and smoking weed.

He has been accused of overemphasising these more innocuous misdemeanours and concealing more nefarious crimes, such as serious drug addiction, pimping, gun running, and stealing from the very community he publicly defended.

At 20, Malcolm X landed in prison with a 10 year sentence for burglary. What might’ve been the short end to a tragic childhood became a place of metamorphosis. Detroit Red was nicknamed Satan in prison, for his bad temper, lack of faith, and preference to be alone.

He shrugged off this title and discarded his family name Little after being introduced to the Nation of Islam and its philosophies. It was, he explained, a name given to him by “the white man”. He was introduced to the prison library and he read voraciously. The influential thinker Malcolm X was born.

Upon his release, he became the spokesperson for the Nation of Islam and grew its membership from 500 to 30,000 in just over a decade. As David Remnick writes in the New Yorker, Malcolm X was “the most electrifying proponent of black nationalism alive”.

Be black and fight back

Malcolm X’s detractors did not view his idea of black power as racial equality. They saw it as pro-violent, anti-white racism in pursuit of black supremacy. But after his own life experiences and centuries of slavery and atrocities against African and Native Americans, many supported his radical voice as a necessary part of public debate. And debate he did.

Malcolm X strongly disagreed with the non-violent, integrationist approach of fellow civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. The differing philosophies of the two were widely covered in US media. Malcolm X believed neither of King’s strategies could give black people real equality because integration kept whiteness as a standard to aspire to and non-violence denied people the right of self defence. It was this take that earned him the reputation of being an advocate of violence.

“… our motto is ‘by any means necessary’.”

Malcolm X stood for black social and economic independence that you might label segregation. This looked like thriving black neighbourhoods, businesses, schools, hospitals, rehabilitation programs, rifle clubs, and literature. He proposed owning one’s blackness was the first step to real social recovery.

Unlike his peers in the civil rights movement who championed spiritual or moral solutions to racism, Malcolm X argued that wouldn’t cut it. He felt legalised and codified racial discrimination was a tangible problem, requiring structural treatment.

Malcolm X held that the issues currently facing him, his family, and his community could only be understood by studying history. He traced threads between a racist white police officer to the prison industrial complex, to lynching, slavery, and then to European colonisation.

Despite his great respect for books, Malcolm X did not accept them as “truth”. This was important because the lives of black Americans were often hugely different from what was written about – not by – them.

Every Sunday, he walked around his neighbourhood to listen to how his community was going. By coupling those conversations with his study, Malcolm X could refine and draw causes for grievances black people had long accepted – or learned to ignore.

We are human after all

Dissatisfied with their leader, Malcolm X split from the Nation of Islam (who would go on to assassinate him). This marked another transformation. He became the first reported black American to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. In his final renaming, he returned to the US as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

On his pilgrimage, he had spoken with Middle Eastern and African leaders, and according to his ‘Letter from Mecca’ (also referred to as the ‘Letter from Hajj’), began to reappraise “the white man”.

Malcolm X met white men who “were more genuinely brotherly than anyone else had ever been”. He began to understand “whiteness” to be less about colour, and more about attitudes of oppressive supremacy. He began to see colonialist parallels between his home country and those he visited in the Middle East and Africa.

Malcolm X believed there was no difference between the black man’s struggle for dignity in America and the struggle for independence from Britain in Ghana. Towards the end of his life, he spoke of the struggle for black civil rights as a struggle for human rights.

This move from civil to human rights was more than semantics. It made the issue international. Malcolm X sought to transcend the US government and directly appeal to the United Nations and Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead.

In a way, Malcolm X was promoting a form of globalisation, where the individual, rather than the nation, was on centre stage. Oppressed people took back their agency to define what equality meant, instead of governments and courts. And in doing so, he linked social revolution to human rights.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 31 JAN 2018

The exposure of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein as a serial harasser and alleged rapist in October 2017 was the tipping point in an unprecedented outpouring of sexual coercion and assault disclosures.

As high profile women spoke out about the systemic misogyny of the entertainment industry, they have been joined by women around the globe using #MeToo to make visible a spectrum of experiences from the subtle humiliations of sexism to criminal violation.

The #MeToo movement has exposed not only the pervasiveness of gendered abuse but also its accommodation by the very workplaces and authorities that are supposed to ensure women’s safety. Some women (and men) have been driven to name their perpetrator via the mass media or social media, in frustration over the inaction of their employers, industries, and police. This has sparked predictable complaints about ‘witch hunts’, ‘sex panics’, and the circumvention of ‘due process’ in the criminal justice system.

Mass media and social media have a critical role in highlighting institutional failure and hypocrisy. Sexual harassment and violence are endemic precisely because the criminal justice system is failing to deter this conduct or hold perpetrators to account. The friction between the principles of due process (including the presumption of innocence) and the current spate of public accusations is symptomatic of the wholesale failure of the authorities to uphold women’s rights or take their complaints seriously.

Public allegations are one way of forcing change, and often to great effect. For instance, the recent Royal Commission into child sexual abuse was sparked by years of media pressure over clergy abuse.

While ‘trial by media’ is sometimes necessary and effective, it is far from perfect. Journalists have commercial as well as ethical reasons for pursuing stories of abuse and harassment, particularly those against celebrities, which are likely to attract a significant readership. The implements of media justice are both blunt and devastating, and in the current milieu, include serious reputational damage and potential career destruction.

The implements of media justice are both blunt and devastating.

These consequences seemed fitting for men like Weinstein, given the number, severity and consistency of the allegations against him and others. However, #MeToo has also exposed more subtle and routine forms of sexual humiliation. These are the sexual experiences that are unwanted but not illegal, occurring in ways that one partner would not choose if they were asked. These scenarios don’t necessarily involve harmful intent or threat. Instead, they are driven by the sexual scripts and stereotypes that bind men and women to patterns of sexual advance and reluctant acquiescence.

The problem is that online justice is an all-or-nothing proposition. Punishment is not dolled out proportionately or necessarily fairly. Discussions about contradictory sexual expectations and failures of communication require sensitivity and nuance, which is often lost within spontaneous hashtag movements like #MeToo. This underscores the fragile ethics of online justice movements which, while seeking to expose unethical behaviour, can perpetrate harm of their own.

The Aziz Ansari Moment

The allegations against American comedian Aziz Ansari were the first real ‘record-scratch’ moment of #MeToo. Previous accusations against figures such as Weinstein were broken by reputable outlets after careful investigation, often uncovering multiple alleged victims, many of whom were willing to be publicly named. Their stories involved gross if not criminal misconduct and exploitation. In Ansari’s case, the allegations against him were aired by the previously obscure website Babe.net, who interviewed the pseudonymous ‘Grace’ about a demeaning date with Ansari. Grace did not approach Babe with her account. Instead, Babe heard rumours about her encounter and spoke to several people in their efforts to find and interview Grace.

In the article, Grace described how her initial feelings of “excitement” at having dinner with the famous comedian changed when she accompanied him to his apartment. She felt uncomfortable with how quickly he undressed them both and initiated sexual activity. Grace expressed her discomfort to Ansari using “verbal and non-verbal cues”, which she said mostly involved “pulling away and mumbling”. They engaged in oral sex, and when Ansari pressed for intercourse, Grace declined. They spent more time talking in the apartment naked, with Ansari making sexual advances, before he suggested they put their clothes back on. After he continued to kiss and touch her, Grace said she wanted to leave, and Ansari called her a car.

In the article, Grace she had been unsure if the date was an “awkward sexual experience or sexual assault”, but she now viewed it as “sexual assault”. She emphasised how distressed she felt during her time with Ansari, and the implication of the article was that her distress should have been obvious to him. However, in response to the publication of the article, Ansari stated that that their encounter “by all indications was completely consensual” and he had been “surprised and concerned” to learn she felt otherwise.

Sexual humiliation and responsibility

Responses to Grace’s story were mixed in terms of to whom, and how, responsibility was attributed. Initial reactions on social media insisting that, if Grace felt she had been sexually assaulted, then she had been, gave way to a general consensus that Ansari was not legally responsible for what occurred in his apartment with Grace. Despite Grace’s feelings of violation, there was no description of sexual assault in the article. Even attributions of “aggression” or “coercion” seem exaggerated. Ansari appears, in Grace’s account, persistent and insensitive, but responsive to her when she was explicit about her discomfort.

A number of articles emphasised that Grace’s story was part of an important discussion about how “men are taught to wear women down to acquiescence rather than looking for an enthusiastic yes”. Such encounters may not meet the criminal standard for sexual assault, but they are still harmful and all too common.

For this reason, many believed that Ansari was morally responsible for what happened in his apartment that night. This is the much more defensible argument, and, perhaps, one that Ansari might agree with. After all, Ansari has engaged in acts of moral responsibility. When Grace contacted him via text the next day to explain that his behaviour the night before had made her “uneasy”, he apologised to her with the statement, “Clearly, I misread things in the moment and I’m truly sorry”.

However, attributing moral responsibility to Ansari for his behaviour towards Grace does not justify exposing him to the same social and professional penalties as Weinstein and other alleged serious offenders. Nor does it eclipse Babe’s responsibility for the publication of the article, including the consequences for Ansari or, indeed, for Grace, who was framed in the article as passive and unable to articulate her wants or needs to Ansari.

Discussions about contradictory sexual expectations and failures of communication require sensitivity and nuance, which is often lost within spontaneous hashtag movements like #MeToo.

For some, the apparent disproportionality between Ansari’s alleged behaviour and the reputational damage caused by Babe’s article was irrelevant. One commentator said that she won’t be “fretting about one comic’s career” because Aziz Ansari is just “collateral damage” on the path to a better future promised by #MeToo. At least in part, Ansari is attributed causal responsibility – he was one cog in a larger system of misogyny, and if he is destroyed as the system is transformed, so be it.

This position is not only morally indefensible – dismissing “collateral damage” as the cost of progress is not generally considered a principled stance – but it is unlikely to achieve its goal. A movement that dispenses with ethical judgment in the promotion of sexual ethics is essentially pulling the rug out from under itself. Furthermore, the argument is not coherent. Ansari can’t be held causally responsible for effects of a system that he, himself, is bound up within. If the causal factor is identified as the larger misogynist system, then the solution must be systemic.

Hashtag justice needs hashtag ethics

Notions of accountability and responsibility are central to the anti-violence and women’s movements. However, when we talk about holding men accountable and responsible for violence against women, we need to be specific about what this means. Much of the potency of movements like #MeToo come from the promise that at least some men will be held accountable for their misconduct, and the systems that promote and camouflage misogyny and assault will change. This is an ethical endeavour and must be underpinned by a robust ethical framework.

The Ansari moment in #MeToo raised fundamental questions not only about men’s responsibilities for sexual violence and coercion, but also about our own responsibilities responding to it. Ignoring the ethical implications of the very methods we use to denounce unethical behaviour is not only hypocritical, but fuels reactionary claims that collective struggles against sexism are neurotic and hysterical. We cannot insist on ethical transformation in sexual practices without modelling ethical practice ourselves. What we need, in effect, are ‘hashtag ethics’ – substantive ethical frameworks that underpin online social movements.

This is easier said than done. The fluidity of hashtags makes them amenable to misdirection and commodification. The pace and momentum of online justice movements can overlook relevant distinctions and conflate individual and social problems, spurred on by media outlets looking to draw clicks, eyeballs and advertising revenue. Online ethics, then, requires a critical perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of online justice. #MeToo is not an end in itself that must be defended at all costs. It’s a means to an end, and one that must be subject to ethical reflection and critique even as it is under way.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Want men to stop hitting women? Stop talking about “real men”

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

BY Michael Salter

Scientia Fellow and Associate Professor of Criminology UNSW. Board of Directors ISSTD. Specialises in complex trauma & organisedabuse.com

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia, we urgently need to talk about data ethics

Australia, we urgently need to talk about data ethics

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Ellen Broad The Ethics Centre 25 JAN 2018

An earlier version of this article was published on Ellen’s blog.

Centrelink’s debt recovery woes perfectly illustrate the human side of data modelling.

The Department for Human Services issued 169,000 debt notices after automating its processes for matching welfare recipients’ reported income with their tax. Around one in five people are estimated not to owe any money. Stories abounded of people receiving erroneous debt notices up to thousands of dollars that caused real anguish.

Coincidentally, as this unfolded, one of the books on my reading pile was Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil. She is a mathematician turned quantitative analyst turned data scientist who writes about the bad data models increasingly being used to make decisions that affect our lives.

Reading Weapons of Math Destruction as the Centrelink stories emerged left me thinking about how we identify ‘bad’ data models, what ‘bad’ means and how we can mitigate the effects of bad data on people. How could taking an ethics based approach to data help reduce harm? What ethical frameworks exist for government departments in Australia undertaking data projects like this?

Bad data and ‘weapons of math destruction’

A data model can be ‘bad’ in different ways. It might be overly simplistic. It might be based on limited, inaccurate or old information. Its design might incorporate human bias, reinforcing existing stereotypes and skewing outcomes. Even where a data model doesn’t start from bad premises, issues can arise about how it is designed, its capacity for error and bias and how badly people could be impacted by error or bias.

Weapons of math destruction tend to hurt vulnerable people most.

A bad data model spirals into a weapon of math destruction when it’s used en masse, is difficult to question and damages people’s lives.

Weapons of math destruction tend to hurt vulnerable people most. They might build on existing biases – for example, assuming you’re more likely to reoffend because you’re black or you’re more likely to have car accidents if your credit rating is bad. Errors in the model might have starker consequences for people without a social safety net. Some people may find it harder than others to question or challenge the assumptions a model makes about them.

Unfortunately, although O’Neil tells us how bad data modelling can lead to weapons of math destruction, it doesn’t tell us much about how we can manage these weapons once they’ve been created.

Better data decisions

We need more ways to help data scientists and policymakers navigate the complexities of projects involving personal data and their impact on people’s lives. Regulation has a role to play here. Data protection laws are being reviewed and updated around the world.

For example, in Australia the draft Productivity Commission report on data sharing and use recommends the introduction of new ‘consumer rights’ over their personal data. Bodies such the Office of the Information Commissioner help organisations understand if they’re treating personal data in a principled manner that promotes best practice.

Guidelines are also being produced to help organisations be more transparent and accountable in how they use data to make decisions. For instance, The Open Data Institute in the UK has developed openness principles designed to build trust in how data is stored and used. Algorithmic transparency is being contemplated as part of the EU Free Flow of Data Initiative and has become a focus of academic study in the US.

Ethics can help bridge the gap between compliance and our evolving expectations of what is fair and reasonable data usage.

However, we cannot rely on regulation alone. Legal, transparent data models can still be ‘bad’ according to O’Neil’s standards. Widely known errors in a model could still cause real harm to people if left unaddressed. An organisation’s normal processes might not be accessible or suitable for certain people – the elderly, ill and those with limited literacy – leaving them at risk. It could be a data model within a sensitive policy area, where a higher duty of care exists to ensure data models do not reflect bias. For instance, proposals to replace passports with facial recognition and fingerprint scanning would need to manage the potential for racial profiling and other issues.

Ethics can help bridge the gap between compliance and our evolving expectations of what is fair and reasonable data usage. O’Neil describes data models as “opinions put down in maths”. Taking an ethics based approach to data driven decision making helps us confront those opinions head on.

Building an ethical framework

Ethics frameworks can help us put a data model in context and assess its relative strengths and weaknesses. Ethics can bring to the forefront how people might be affected by the design choices made in the course of building a data model.

An ethics based approach to data driven decisions would start by asking questions such as:

- Are we compliant with the relevant laws and regulation?

- Do people understand how a decision is being made?

- Do they have some control over how their data is used?

- Can they appeal a decision?

However, it would also encourage data scientists to go beyond these compliance oriented questions to consider issues such as:

- Which people will be affected by the data model?

- Are the appeal mechanisms useful and accessible to the people who will need them most?

- Have we taken all possible steps to ensure errors, inaccuracies and biases in our model have been removed?

- What impact could potential errors or inaccuracies have? What is an acceptable margin of error?

- Have we clearly defined how this model will be used and outlined its limitations? What kinds of topics would it be inappropriate to apply this modelling to?

There’s no debate right now to help us understand the parameters of reasonable and acceptable data model design. What’s considered ‘ethical’ changes as we do, as technologies evolve and new opportunities and consequences emerge.

Bringing data ethics into data science reminds us we’re human. Our data models reflect design choices we make and affect people’s lives. Although ethics can be messy and hard to pin down, we need a debate around data ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Twitter made me do it!

Explainer

Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: The Turing Test

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

BY Ellen Broad

Ellen Broad is a freelance consultant and postgraduate student in data science. Until recently, she was Head of Policy for the Open Data Institute in London.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia Day and #changethedate - a tale of two truths

Australia Day and #changethedate – a tale of two truths

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 JAN 2018

The recent debate about whether or not Australia Day should be celebrated on 26th January has been turned into a contest between two rival accounts of history.

On one hand, the ‘white arm band’ promotes Captain Arthur Phillip’s arrival in Port Jackson as the beginning of a generally positive story in which the European Enlightenment is transplanted to a new continent and gives rise to a peaceful, prosperous, modern nation that should be celebrated as the envy of the world.

On the other hand, the ‘black arm band’ describes the British arrival as an invasion that forcefully and unjustly dispossesses the original owners of their land and resources, ravages the world’s oldest continuous culture, and pushes to the margins those who had been proud custodians of the continent for sixty millennia.

This contest has become rich pickings for mainstream and social media where, in the name of balance, each side has been pitched against the other in a fight that assumes a binary choice between two apparently incommensurate truths.

However, what if this is not a fair representation of the what is really at stake here? What if there is truth on both sides of the argument?

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that the First Fleet brought many things. Some were good and some were not. Much that is genuinely admirable about Australia can be traced back to those British antecedents. The ‘rule of law’, the methods of science, the principle of respect for the intrinsic dignity of persons… are just a few examples of a heritage that has been both noble in its inspiration and transformative in its application in Australia.

Of course, there are dark stains in the nation’s history – most notably in relation to the treatment of Indigenous Australians. Not only were the reasonable hopes and aspirations of Indigenous people betrayed – so were the ideals of the British who had been specifically instructed to respect the interests of the Aboriginal peoples of New Holland (as the British called their foothold on the continent).

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that both accounts are true. And so is our current incapacity to realise this.

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that the arrival of the Europeans was a disaster for those already living here for generations beyond human memory. This was the same kind of disaster that befell the Britons with the arrival of the Romans, the same kind of disaster visited on the Anglo-Saxons when invaded by the Vikings and their Norman kin. Land was taken without regard for prior claims. Language was suppressed, if not destroyed. Local religions trashed. All taken – by conquest.

No reasonable person can believe the arrival of Europeans was not a disaster for Indigenous people. They fought. They lost. But they were not defeated. They survive. Some flourish. Yet with only two hundred or so years having passed since European arrival, the wounds remain.

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that both accounts are true. And so is our current incapacity to realise this. Instead we are driven by politicians and commentators and, perhaps, the temper of the times, to see the world as one of polar opposites. It is a world of winners and losers, a world where all virtue is supposed to lie on just one side of a question, a world in which we are cut by the brittle, crystalline edges of ideological certainty.

So, what are we to make of January 26th? The answer depends on what we think is to be done on this day.

One of the great skills cultivated by ethical people is the capacity for curiosity, moral imagination and reasonable doubt. Taken together, these attributes allow us to see the larger picture – the proverbial forest that is obscured by the trees. This is not an invitation to engage in some kind of relativism – in which ‘truth’ is reduced to mere opinion. Instead, it is to recognise that the truth – the whole truth – frequently has many sides and that each of them must be seen if the truth is to be known.

But first you have to look. Then you have to learn to see what might otherwise be obscured by old habits, prejudice, passion, anger… whatever your original position might have been.

So, what are we to make of January 26th? The answer depends on what we think is to be done on this day. Is it a time of reflection and self-examination? If so, then January 26th is a potent anniversary. If, on the other hand, it is meant to be a celebration of and for all Australians, then why choose a date which represents loss and suffering for so many of our fellow citizens?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

ExplainerBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JAN 2018

Social license – or social license to operate – is a term that has been in usage for almost 20 years. At its simplest, it refers to the acceptance granted to a company or organisation by the community.

Of course anyone running a company would be aware that there are many formal legal and regulatory licenses required to operate a legitimate business. Social license is another thing again: the informal “license” granted to a company by various stakeholders who may be affected by the company’s activities. Such a license is based on trust and confidence – hard to win, easy to lose.

It’s useful to understand that the term “social license to operate” first came into the world in reference to the mining and extractive industries. In an era of heightened awareness of environmental protection and sustainability, the legitimacy of mining was being questioned. It became apparent that the industry would need to work harder to obtain the ongoing broad acceptance of the community in order to remain in business.

To give a simple example: a mining company may be properly registered with all appropriate agencies; it may have a mining license, it may be listed with ASIC and be paying its taxes. It may meet every single obligation under the Fair Work Act. But if the mine is using up precious natural resources without taking due care of the environment or local residents, it will have failed to gain the trust and confidence of the community in which it operates.

Over time, the social license terminology has crossed into the mainstream and is now used to describe the corporate social responsibility of any business or organisation. A whole industry has flourished around Sustainability and Corporate Stakeholder Engagement. And there’s a growing view that social responsibility can be good for long-time financial performance and shareholder value.

The social license to operate is made up of three components: legitimacy, credibility, and trust.

- Legitimacy: this is the extent to which an individual or organisation plays by the ‘rules of the game’. That is, the norms of the community, be they legal, social, cultural, formal or informal in nature.

- Credibility: this is the individual or company’s capacity to provide true and clear information to the community and fulfil any commitments made.

- Trust: this is the willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another. It is a very high quality of relationship and takes time and effort to create.

The rise of social license can be traced directly to the well-documented erosion of community trust in business and other large institutions. We’re living in an era in which business (or indeed Capitalism itself) is blamed for many of the world’s problems – whether they be climate change, income inequality, modern slavery or fake news. Many perceive globalisation to have had a negative impact on their quality of life.

There’s a growing expectation that businesses – and business leaders – should take a more active role in leading positive change. There’s a belief that business should be working to eliminate harm and maximise benefits – not just for shareholders or customers, but for everyone. To do this, business would be actively engaging with stakeholders, including the most outspoken or marginalised voices; they should be prepared to listen, and reflect, on the concerns of these often powerless individuals.

There is no simple list of requirements that have to be met in order to be granted a social licence to operate.

Too often, social licence is thought to be something that can be purchased, like an offset. Big companies with controversial practices often give out community grants and investments. Clubs that profit from addictive poker machines provide sports gear for local teams and inexpensive meals for pensioners. Tax minimisers set up foundations; soft drink companies fund medical research.

Here a social licence to operate might be seen as a kind of transaction where community acceptance can be bought. Of course, such an approach will often fail precisely because it is conceived as a calculated and cynical pay-off.

The effective co-existence of businesses and individuals within a community requires the development of rich and enduring relationships based on mutual respect and understanding. That sounds like something we’ll all need to work on.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethics in engineering makes good foundations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil The Ethics Centre 10 JAN 2018

How had I found myself here again?

I tucked my phone away. Apart from all the fun Facebook promised me others were having, I had grown tired of reading the newest obituary of my dwindling friendships. The schoolmate: “No, not free that week.” The travel buddy: “I keep forgetting to call you!” The silent group chat, last message from a fortnight ago: “Due for a catch up?” Even the group of laughing school girls on the bus loomed over me as a promise of what I could have had. If only I wasn’t… a bad friend.

A bad friend.

The very thought made me shudder. A bad friend, that modern spectre of malice. Nice to your face while secretly gossiping about you behind your back. Undercutting your achievements with little barbs of competition. Judging you for your mistakes and holding them against you for years to come. Leaving you feeling like a used tissue. Toxic.

I floundered in denial. I wasn’t one of those! I love my friends. I send birthday messages. I text in stagnant group chats. I offer a warm, understanding, slightly anxious shoulder to lean on. I even hosted Game Night!

Besides, that’s just modern friendships. We work full time. We’re sleep deprived. We’re too poor to brunch. Flush with self righteousness, I turned back to my phone. “Missing you guys! Anyone free tonight?”

(Too short notice. Rookie mistake.)

I wouldn’t say I was primed for loneliness. I was just ready to complain about it when it happened.

After weeks of this I was in a slump. A blind spot lingered in my vision – until a wise colleague offhandedly told me that in her 23 years of marriage, she had to learn how to love. ‘I’ve gotten a lot better at it’, she assured me.

Bingo.

It was so obvious that I wanted to kick myself. Love was a verb. Just like we learn to read, write, walk, and talk, so too do we learn to love. And just like any other skill, we learn by doing – not just by thinking.

Social media didn’t help. By knowing their names, plans and volatile political opinions, I felt like I had spent time with my friends when I was making minimal effort to connect with them at all.

I had fallen prey to this. I had spent so much time thinking and complaining and ruminating and reading about friendship that it began to feel like work. Like I was doing something about it. The old adage ‘friendship takes work’ bloomed into neuroticism. And I furiously dug myself deeper into the same hole.

All of this wasn’t making me a better friend. I thought I was being patient, when I was really being avoidant. I thought I was being strong, when I was scared to ask for help. When I spoke to my friends, I masked the chatter of discontent and unfulfilled longing with carefully crafted text messages, small kindnesses, and pleasant banter. In unintentionally defining love as the balm against loneliness, I’d missed out on crucial considerations along the way. Namely:

A common purpose

Aristotle believed the greatest type of friendship was one forged between people of similar virtue who recognise and appreciate each other’s good character. To him, true happiness and fulfilment came from living a life of virtue. To have a friend who lived by this and helped you achieve the same was one of the greatest and rarest gifts of all.

A spirit of generosity

For Catholic philosopher St Thomas Aquinas, friendship was the ideal form of relationships between rational beings. Why? Because it had the greatest capacity to cultivate selflessness. Friendships let you leave your ego behind. What they love becomes equal to or greater than the things you love. Their flourishing becomes a part of your flourishing. If they’re not doing well, neither are you.

The golden rule

Imam Al-Ghazzali, a Muslim medieval philosopher, wrote friendship was the physical embodiment of treating others as you would like to be treated. In practice, “To be in your innermost heart just as you appear outwardly, so that you are truly sincere in your love for them, in private and in public”.

Knowing and being known

Philosopher Mark Vernon sees friendship as a kind of love that consists of the desire to know another and be known by them in return. This circle of requiting genuine interest and affection is perhaps one the more rewarding elements of friendships.

And most of all, these things take time.

Now, this isn’t a self-help article. I’m not going to tell you if you follow these Four Simple Steps, you too can have real friends. After all, the number of people we can count as friends, however small or large, can be a matter of luck and chance. But understanding what friendships are made of helps you grab an opportunity when it arises.

Later that week, I bit the bullet. My friends were back from overseas, and summer school hadn’t started yet. I stood down from my altar, voice raw from shouting ‘FACE TO FACE CONTACT ONLY’. I downloaded Skype, remembered my password and spent my night ironing clothes and chatting to my friends. Leaning into the ickiness of admitting I needed help with some things rewarded me with laughter, warmth, and plans to buy a 2018 planner.

As lonely and confusing as the world is, it can be even more so if we do so in the absense of good friends. Make an effort to be the friend that helps each other navigate — and avoid — the lonely confusion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

When I am unsure if something is ethical, my favourite ‘ready reckoner’ is to apply the reflection test – I ask myself if I could look myself in the mirror after doing it.

Would my self-image be helped or hindered by the action? I could also call it ‘the slumber test’. Will I be able to sleep at night after doing what I’m setting out to do?

I’ve spent years studying the ethical and psychological toll that comes with doing things that stop us from meeting our own eyes in the mirror. There is a price that comes when we violate our most precious moral beliefs.

In military communities, this price is called a ‘moral injury’. Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay, the foundational voice on the subject, describes it poetically as “the soul wound inflicted by doing something that violates one’s own ethics, ideals, or attachments”.

This needs attention

As parochial as talk of souls might be, organisations should start paying attention to this risk for three reasons:

- So they can take steps to prevent their workers from being affected by moral injuries (basically, as an OH&S issue).

- So they know how to spot and manage moral injuries if they do occur.

- To figure out what support and remuneration they should offer if it turns out moral injuries are an ‘occupational hazard’.

The OH&S analogy is apt. Today, we expect organisations to think about their duty of care in a broad sense – taking an active interest in their employees’ wellbeing, seeking to reduce the risk of physical injuries, managing and minimising psychological stressors and mental illness, and providing fair training, support, and compensation when physical or mental stressors are likely to have a negative effect on employee wellbeing.

So, it follows that if some ethical issues can have an effect on wellbeing, they should be treated seriously by organisations claiming to care about their people.

How moral injury takes place

Moral injury is still a contested topic. Some people think it’s just a variation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), others think it’s no different from moral emotions like guilt, regret or remorse, and others still see it as something distinct.

Among veterans (who tend to dominate discussions of moral injury), the condition is seen as a condition akin to PTSD – a different kind of war trauma with different causes and different treatment pathways.

Whilst PTSD originates in feelings of fear and physical insecurity, moral injuries arise when we witness a betrayal or violation of our most deeply held beliefs about what’s right. It has to happen in a high stakes situation and the wrongdoing has to have been committed by someone in a position of ‘moral authority’ – a position you yourself might hold.

A group of US psychologists who have studied the issue offer a similar definition, describing moral injuries as “maladaptive beliefs about the self and the world” that emerge in response to the betrayal of what’s right. The injury is caused by the betrayal, but it’s in the beliefs and our response to them that it actually resides.

When we suffer a moral injury, our beliefs about ourselves, our world, or both are shattered in the wake of what we’ve witnessed or done.

Our moral beliefs are one of the ways we see the world and one of the ways we conceptualise ourselves. Everything flips when people no longer adhere to a ‘code’, good people are forced to do bad things for good reasons, or our different identities contradict one another.

This contradiction gives rise to ‘fragmentation’. Our moral beliefs, identities and actions no longer harmonise with one another. In the words of Les Miserables’ Inspector Javert, we find ourselves thrown into “a world that cannot hold”. Fragmentation demands reunification, and the way we go about this will determine both the extent of the moral injury and the likelihood of recovery.

How we respond to the conflict

If we can accept the critical event as being a rare product of extreme circumstances and a particular context, it’s possible to move on. We can accept guilt and seek forgiveness, admit our trust in a moral authority was betrayed and sever ties, or concede that the world is not as fair as we had thought.

This approach is relatively risk-free, albeit unpleasant.

However, if we are unable to see the event as context-dependent and, instead, see it as reflecting something universal – or worse, something about us – then a moral injury is likely to occur.

For example, if we have a handshake agreement to honour a business deal which is then betrayed, leading to widespread unemployment, we might decide that people are no longer trustworthy and either withdraw from them altogether or ‘get them before they get us’ next time. Either approach has an impact on a person’s ability to flourish in society.

Another possibility lies in concluding that we must be bad in order for us to have done what we did. Even if we were doing our duty without fault, guilt lingers and an employee could be permanently tainted by what they have done: “How can I say I am a good person when my actions resulted in this?”

Finally, we can recalibrate our moral beliefs. Perhaps, as many veterans argue, we were wrong to think the world was predictable or reliable to begin with. Maybe our moral injury isn’t an injury at all. Perhaps it’s a sign we’ve learned something new.

What employers can do

Moral injuries must be addressed because they affect a person’s future ethical decision making and their capacity for happiness.

This gives organisations another reason to have a robust ethical culture that guards against wrongdoing and refuses to ask people to act against their conscience.

However, this won’t always be possible. Sometimes professional demands require people to ‘get their hands dirty’, witness wrongdoing or even participate in something they feel contradicts their moral beliefs.

A committed parent may be required to decline an insurance claim, leaving the claimants – a family– homeless. How will he go home and sit with his children knowing his actions have put another family in jeopardy? A nurse may be legally prohibited from helping someone to end their life. Can she be a good person while allowing someone to needlessly suffer?

The question of moral injury has typically been posed as an individual problem but, if the OH&S analogy is a valid one, we should think about the responsibilities of organisations in the wake of what we’re learning.

An organisation violates its duty of care if it exposes workers to risk without reason, consent, support or fair compensation. Perhaps we might say the same for moral injuries, with one important caveat: it would be perverse and potentially corruptive to offer financial incentives for people to compromise their values and moral beliefs, offering a salary increase to be exposed to ethical risks, for instance.

A clear ethical purpose with which staff can identify and that is consistent with their moral beliefs is a more appropriate incentive. Not only might this prevent wrongdoing in the first instance, it can help reunify a fragmented identity if a moral injury does occur.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

WATCH

Business + Leadership

The thorny ethics of corporate sponsorships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

Nick Naylor is a man who is comfortable being despised. In the movie Thank You for Smoking, he is the spokesman for the tobacco lobby and happily admits he fronts an organisation responsible for the deaths of 1,200 people every day.

While he excuses his employment as a lobbyist by unconvincingly adopting the “Yuppie Nuremberg defence” of having to pay a mortgage, the audience learns that his real motivation is that he loves to win.

The bigger the odds, the better.

Naylor is not the sort of man who would struggle with ethical distress or moral injury from the work he chooses to do. This work “requires a moral flexibility that is beyond most people”, he says.

He likens his role to that of a lawyer, who has to defend clients whether they are guilty or not.

Partner of law firm Maurice Blackburn, Josh Bornstein, says the convention in law that everyone deserves legal representation can certainly assist lawyers called upon to defend people whose actions they find morally reprehensible – however that argument does not work for everyone.

‘If I don’t, someone else will’

Bornstein says there is no way of knowing how many lawyers refuse to work on cases because of moral conflict, but it happens from time to time. “Not every week or every month”, he adds.

“Do [lawyers] have moral crises? Some people have a strong sense of morality and others try and sweep that to one side and consider that, as professional lawyers, they shouldn’t dwell on moral concerns”, says Bornstein, who specialises in workplace law.

Bornstein is well known for his advocacy for victims of bullying and harassment, however, he has also acted for people accused of those things.

“I’ve found myself, from time to time, acting in matters that have been very morally confronting”, he says.

As a young lawyer, when he was expressing his disapproval of the actions of a client, his mentor told him to stop moralising and indulging himself.

“He said that when people like that get into that trouble, that is the time they need your assistance more than any other. Your job is to help them, even when they have done the wrong thing”, says Bornstein.

Bornstein says ethical distress can occur in all sorts of professions. “I would think the same would occur for a psychologist, social worker, doctors, and maybe even priests.

“Consider the position if you were lawyers for the Catholic Church over the last three decades, dealing with horrific, ongoing cases of child sexual abuse.”

Distress or injury? Making a distinction

The CEO of Relationships Australia NSW, Elisabeth Shaw, says when seeking to understand the psychological damage wrought by such conflicts, a distinction should be made between ethical (or moral) distress and moral injury.

Ethical or moral distress occurs when someone knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.

This definition is often used in nursing, where staff are conflicted between doing what they feel is right for the patient and what hospital protocol and the law allows them to do. They may, for instance, be required to resuscitate a terminally ill patient who had expressed a desire to end the pain and die in peace.

Moral injury is a more severe form of distress and tends to be used in the context of war, describing “the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioural, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations”.

The St John of God Chair of Trauma and Mental Health at the University of New South Wales, Zachary Steel, says most moral injuries stem from “catastrophic traumatic encounters”, such as military and first responder types of duties and responsibilities.

He says he sees moral injury as a variant of post-traumatic stress disorder and distinguishable from the kind of moral harm wrought by bullying and highly dysfunctional workplaces.

Tainted by your compliance

This distinction does not diminish the distress experienced by those who are torn between what they are expected to do, and what they know they should do.

Shaw, who has volunteered at The Ethics Centre’s Ethi-call hotline for eight years as team supervisor, says the service handles around 1,500 calls per year and a typical request for advice may come from an accountant who is pressured to sign off on dodgy records.

“After [complying], you may feel a lesser version of yourself. You may feel you didn’t have a choice, but also feel quite tainted by those actions”, she says.

“Even if you went to great lengths to do all the things that could be seen to be correct, you can still feel very injured at the end of it.”

For some people, it is the nature of the organisation they work for, or its culture, that creates a problem.

“Some people feel like they are part of an organisation that is, perhaps, habitually part of shabby behaviour”, says Shaw.

Someone working for a tobacco company (like the fictional Nick Naylor) may start by shrugging off concerns, reasoning that they need the job and if they don’t do it, someone else will. However, over time, embarrassment grows and they become more aware of the disapproval of others and they start to feel morally compromised, says Shaw.

“And then there is a point where it feels like [your job] has injured your sense of self … or even your professional identity and, in fact, might make you feel less than yourself.”

There are also professions where people sign up for noble reasons, in a not-for-profit, for instance, but then find unjustifiable things are happening.

“You start to feel like there is a huge dissonance – that can no longer be resolved – between what you say you are doing and what you are actually caught up in.”

Can’t tell right from wrong

Burnout and mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression can result from this stress and some people become so ethically compromised they lose their moral compass and no longer can tell right from wrong, she says.

Moral distress is one of a range of factors contributing to the poor record of the law profession when it comes to the incidence of mental health issues, says Bornstein.

A third of solicitors and a fifth of barristers are understood to suffer disability and distress due to depression.

Some of the more “sophisticated” firms encourage their people to seek assistance and offer employee assistance programs, such as hotlines.

Maurice Blackburn has a “vicarious trauma program” for lawyers who may, for instance, work with people dying from asbestosis or medical mishaps or accidents.

“Even in my area of employment [workplace law], vicarious trauma is a real risk and problem”, he says.

“So, we have tried to change our culture to be very open about it, speak about it, to regularly review it, to work with psychologists, to have a program to deal with it, to know what to do if a client threatens suicide or self-harm. But it is an ongoing challenge.”

Bornstein has, himself, sought guidance from the Law Institute on ethical dilemmas.

“The other underestimated, fantastic outlet is to confer with colleagues you respect who are, hopefully, one step or more removed from the situation and can give wise counsel. Another is to seek similar support from barristers, I’ve done that too, and then there is friends and family.”

Bornstein says even though he is not aware of any law firm offering a “moral repugnance policy” that would allow people to avoid working on cases that could cause ethical distress, he is aware there would be little benefit in forcing a lawyer to take one.

“It may be resolved by [getting] someone else working on the case.”

The value of a strong ethical framework

Social work is another area that is fraught with ethical dilemmas and, like lawyers, social workers often see people at their worst.

However, the profession has a developed an ethical framework and support system that ensures workers are not left alone to tackle difficult dilemmas, says Professor Donna McAuliffe, who has spent the past 20 years teaching and researching in the area of social work and professional ethics.

“The decisions that social workers have to make can be very complex and distressing if they are not made well”, says McAuliffe, who is Deputy Head of School at the School of Human Services and Social Work at Griffith University.

Social workers have a responsibility, under their code of ethics, to engage professional supervision provided by their employer.

Because social work in Australia is a self-regulated profession, it is important to have a very robust and detailed code of ethics to give guidance around practise, she says.

“We educate social workers to not go alone with things, that consultation and support of colleagues are going to be the best buffers against burn out and distress and falling apart in the workplace – and there is evidence to show good collegial, supportive relationships at work is the thing that buffers against burnout in the best way.”

McAuliffe says employers in business may think about building into their ethical decision making frameworks some consideration of the emotions, worldview, and cultures of the people affected by difficult workplace choices.

“The decision may still be the same … but the [employee] will feel a hell of a lot better about it if they know they have thought about how the person at the end of that decision can be supported.”

Shaw cautions that people should try and seek other perspectives before making decisions about situations that make them feel morally uncomfortable.

“Part of the process of ethical reflection is to work out, ‘Do I have a point?’

“Because we are all developed in different ways ethically, just because you have a reaction and you are worried about something and you feel ethically compromised doesn’t make you correct.

“What it means is that your own moral code feels compromised. The first thing to do is spend some time working out, is my point valid? Do I have all the facts?

“What do I do about the fact that my colleagues and bosses don’t feel bothered? Should I look at their point of view?

“Sometimes, when you feel like that, it really is a trigger for ethical reflection. Then, on the basis of your ethical reflection, you might say, ‘You know what? Now that I have looked at it from many angles, I think, perhaps I was over-jumpy there and I think if I take these three steps, I could probably iron this out, or if I spoke up, change might happen.’

“And then the whole thing can move on.

“Having a reaction to what feels like an ethical trigger is really just the beginning of a process of self-understanding and the understanding in context.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to spot an ototoxic leader

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Steven York The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

The man waiting for me in the meeting room was an unexpected visitor. He introduced himself as the head of a government department and welcomed me to the Czech Republic. He had brought a “friend”.

“You are going to have meet your budget, but I can give you all the government work you need”, he said with a meaningful look. “I just want you to employ this girl.”

He pointed to the young woman who sat opposite. She was beautiful, breathtakingly so, and I suspected she was to be a “spy” for the government. Working on behalf of British and US lenders, I was leading a team investigating cases of fraud that often wound their way back to organised crime and government figures.

I was just a few months into my posting to Eastern Europe and I knew to be wary. This is a country where surveys show two thirds of Czech citizens (66%) believe that most, or almost all, public officials are corrupt.

I left the room, grabbed the arm of my direct report and said, “I think I have just been offered a bribe”.

My first strategy was to make the problem go away by making it clear that everything was to be “above board”.

I walked back into the meeting room. “Leave it with me”, I said. “Look, it sounds interesting, send me her CV and we will see where she may fit in the organisation.”

I had made no commitment, but had asked him to “make it official”. But that was not the end of it. No CV arrived, but three weeks later he was back, unsmiling this time.

“If you don’t employ her, you won’t get any government work at all”, he threatened. I thanked him, said I understood what he was talking about and asked him once more to send the CV. He left without shaking my hand.

A senior leader within the organisation I worked for pulled me up the following day to berate me for being so stupid. Bribes and corruption are a ubiquitous part of the business environment in some countries.

While the organisation might have seen a brown paper bag full of cash as corruption, “scratching each other’s back” in this way was regarded as mere facilitation.

It came to me right then, that this was a real turning point.

With 20 years in the NSW Police behind me, I thought I was a bit of a tough guy, but I knew my life was about to change if I did not change my mind about hiring the “spy”. This could be a dangerous situation because of the kind of people involved in corruption.

It became clear that I had become a problem to the people running the Prague office. At every executive meeting, the others would roll their eyes when I spoke. Their attitude was that we had to get the business, no matter what. Eventually I had to leave before my contract was up.

Looking back through the intervening years, are there things I would have done differently? Perhaps I should have tried being upfront with the CEO – however, he was new to the job and was part of the “giggle”.

I thought at the time that it was better to leave the matter “intangible”, to not start a fight when I was the only Australian in the office.

I had let them know where I stood – a strategy that worked well in the Police Force where, if you were known as a straight shooter, people wouldn’t approach you with corrupt offers.

I could have done more research to find out what was the normal way of conducting business there. I knew there was a lot of corruption in the country, but I had thought the organisation I was working for was above that. It wasn’t. It was part of it.

I could have made my ethical standards clear to the CEO and management team before I started. If I had known their attitude, I would not have taken the job. If they had known mine, they wouldn’t have hired me.

My advice to others in this situation is to bring the matter out into the open, but think about your personal safety. Make sure you have a good exit plan.

An interesting thing about the culture of corruption is it can be invisible. If you didn’t look out the window into the Prague winter, you would think you were in Australia. The building was the same, the people were the same. So, you could be seduced into thinking you could operate the same way there as you do in Australia, but the culture is so very different.

.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership