Ethics Explainer: Longtermism

Longtermism argues that we should prioritise the interests of the vast number of people who might live in the distant future rather that the relatively few people who do live today.

Do we have a responsibility to care for the welfare of people in future generations? Given the tremendous efforts people are making to prevent dangerous climate change today, it seems that many people do feel some responsibility to consider how their actions impact those who are yet to be born.

But if you take this responsibility seriously, it could have profound implications. These implications are maximally embraced by an ethical stance called ‘longtermism,’ which argues we must consider how our actions affect the long-term future of humanity and that we should prioritise actions that will have the greatest positive impact on future generations, even if they come at a high cost today.

Longtermism is a view that emerged from the effective altruism movement, which seeks to find the best ways to make a positive impact on the world. But where effective altruism focuses on making the current or near-future world as good as it can be, longtermism takes a much broader perspective.

Billions and billions

The longtermist argument starts by asserting that the welfare of someone living a thousand years from now is no less important than the welfare of someone living today. This is similar to Peter Singer’s argument that the welfare of someone living on the other side of the world is no less ethically important than the welfare of your family, friends or local community. We might have a stronger emotional connection to those nearer to us, but we have no reason to preference their welfare over that of people more spatially or temporally removed from us.

Longtermists then urge us to consider that there will likely be many more people in the future than there are alive today. Indeed, humanity might persist for many thousands or even millions of years, perhaps even colonising other planets. This means there could be hundreds of billions of people, not to mention other sentient species or artificial intelligences that also experience pain or happiness, throughout the lifetime of the universe.

The numbers escalate quickly, so if there’s even a 0.1% chance that our species colonises the galaxy and persists for a billion years, then that means the expected number of future people could number in the hundreds of trillions.

The longtermism argument concludes that if we believe we have some responsibility to future people, and if there are many times more future people than there are people alive today, then we ought to prioritise the interests of future generations over the interests of those alive today.

This is no trivial conclusion. It implies that we should make whatever sacrifices necessary today to benefit those who might live many thousands of years in the future. This means doing everything we can to eliminate existential threats that might snuff out humanity, which would not only be a tragedy for those who die as a result of that event but also a tragedy for the many more people who were denied an opportunity to be born. It also means we should invest everything we can in developing technology and infrastructure to benefit future generations, even if that means our own welfare is diminished today.

Not without cost

Longtermism has captured the attention and support of some very wealthy and influential individuals, such as Skype co-founder Jaan Tallinn and Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz. Organisations such as 80,000 Hours also use longtermism as a framework to help guide career decisions for people looking to do the most good over their lifetime.

However, it also has its detractors, who warn about it distracting us from present and near-term suffering and threats like climate change, or accelerating the development of technologies that could end up being more harmful than beneficial, like superintelligent AI.

Even supporters of longtermism have debated its plausibility as an ethical theory. Some argue that it might promote ‘fanaticism,’ where we end up prioritising actions that have a very low chance of benefiting a very high number of people in the distant future rather than focusing on achievable actions that could reliably benefit people living today.

Others question the idea that we can reliably predict the impacts of our actions on the distant future. It might be that even our most ardent efforts today ‘wash out’ into historical insignificance only a few centuries from now and have no impact on people living a thousand or a million years hence. Thus, we ought to focus on the near-term rather than the long-term.

Longtermism is an ethical theory with real impact. It redirects our attention from those alive today to those who might live in the distant future. Some of the implications are relatively uncontroversial, such as suggesting we should work hard to prevent existential threats. But its bolder conclusions might be cold comfort for those who see suffering and injustice in the world today and would rather focus on correcting that than helping build a world for people who may or may not live a million years from now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How can we travel more ethically?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipClimate + Environment

BY Isabella Vacaflores 22 MAR 2022

Consumer responses are crucial to holding businesses accountable for their social and environmental responsibilities.

As of this year, over half of the highest polluting companies in Australia have committed to net-zero emissions targets. Meanwhile, in the Twitter-verse, dating apps and chocolate bars proclaim an end to police brutality, sexism, and the Uighur genocide.

Out of nowhere, big business has seemingly grown a social consciousness – and an impressive marketing budget to match. From fast fashion to mining, you’d be hard-pressed to find a company that doesn’t claim to be doing the right thing by their employees and the environment.

Moral grandstanding: When businesses fail to put their money where their mouth is

Unfortunately, a lot of this moral messaging is nothing more than opportunistic marketing, designed to profit from a societal shift towards conscious consumption. As recent reporting by Greenpeace highlights, of those Australian companies that claim to be going green, only a small fraction are actually taking effective steps by switching to cleaner energy sources.

Likewise, many brands divert attention from dubious business operations by aligning themselves with the popular side of trending moral discourse, tweeting out support for social justice movements while simultaneously being accused of the very issues they rally against. As in the following advertisement, which seemingly suggests that the solution to America’s police brutality problem is drinking Pepsi, even at best case, such messaging can come across as offensively tone-deaf.

This phenomenon is what philosophers Justin Tosi and Brandon Warmke describe as ‘moral grandstanding’ – the insincere use of principled arguments to self-promote or seek status. Similarly, the terms ‘virtue signalling’, ‘performative activism’, ‘green-washing’ and ‘woke capitalism’ describe how moral concerns can be deployed as a front for self-serving behaviour.

Ultimately, all these phrases describe the same thing, which is the failure of businesses to practice what they preach.

This hypocrisy is a problem because it prevents meaningful change from occurring while simultaneously misleading consumers into believing that we are well on the way to a better world when actually, progress flounders.

Doing something is better than doing nothing, except when it isn’t

Consequentialism asserts that actions are good if they cause more benefit than harm. Using this line of reasoning, many argue that insincerity is a small price to pay for having big business commit to less harmful commercial practices, which diminishes moral grandstanding to a largely trivial concern.

Yet, when we contemplate the opportunity cost of accepting such half-baked behaviour from those who have the most power to affect change, this argument quickly becomes self-defeating. Consider what would happen if businesses diverted the money and resources spent on advertising their moral character towards researching and enacting reforms that put substance behind these self-proclaimed progressive values.

As consumers, we cannot accept anything less than this because to do so would cause our planet and people to needlessly suffer – a harm that far outweighs any benefit gained from morally grandstanding promises to “do better”.

Additionally, from a deontological perspective, it can be argued that the intention behind moral actions is what truly determines their worth. Since morally grandstanding companies aren’t motivated by a principled duty, but rather, by a profit outcome, they can hardly be considered good (in a Kantian sense, anyway).

How to spot a moral grandstander

In the past half-decade, energy giant AGL has heavily advertised their pledge to decarbonise while simultaneously remaining Australia’s largest greenhouse emitter. Meanwhile, companies such as Woolworths, Coles and Telstra have quietly gotten on with transitioning to almost 100 per cent renewable energy.

Greenpeace campaign takes aim at AGL. Image by Monster Children Creative

Evidently, some businesses are being genuine with their environmental and social commitments. The problem with moral grandstanders is that they take the spotlight away from such efforts. As consumers, we can have a meaningful impact on our world by choosing to spend our money with the former, but the question remains of how to distinguish between the two:

- Consumers can start by asking themselves about the nature of the company which is making the moral appeal –are harmful business practices embedded in the industry they operate in? Does the business themselves have a poor social or environmental track record? If the answer to either of these questions is ‘yes’, then their claims should be viewed suspiciously.

- Be on the lookout for weasel words – buzz-wordy claims which are deliberately vague. Saying something is “green” or “eco-friendly” isn’t a qualifiable statement. Also, note that the validity of some credentials relating to fair trade and carbon emissions are being increasingly challenged.

- As with any investment, if you’re going to put your money into a business based on their moral claims, fact-checking is always a good idea. This can be done through a quick internet search or a skim through related news results.

Remember that in many countries (including Australia), consumer rights laws exist to ensure companies cannot get away with making false claims about their products. Holding businesses to account for their moral grandstanding is therefore not just an ethical imperative – but a legal one also.

Kendall Jenner advertisement and images courtesy of Pespi

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Business + Leadership

Leading With Purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How can we travel more ethically?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

BY Isabella Vacaflores

Isabella is currently working as a research assistant at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. She has previously held research positions at Grattan Institute, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. She has won multiple awards and scholarships, including recently being named the 2023 Australia New Zealand Boston Consulting Group Women’s Scholar, for her efforts to improve gender, racial and socio-economic equality in politics and education.

How can we travel more ethically?

How can we travel more ethically?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY Simon Longstaff 14 DEC 2021

I used to be an inveterate traveller – so much so that I would take, on average, a minimum of two flights per week. That is no longer the case.

I have trouble recalling the last time I was on an aeroplane. That will change this week, when I board a flight for Tasmania – my third attempt, in two years, to join family there. So, is this the beginning of a return to a life of endless travel – both at home and abroad? Or will a trip to the airport continue to be a relatively rare experience?

Of course, such questions apply to all modes of transport – whether they be by road, rail, air or sea. Perhaps we have become conditioned to think that the answers lie in the hands of public health officials and government ministers who, between them, can stop us in our tracks.

However, every journey begins with us – with a personal decision to travel. So, what should we take into account when making such a decision?

Perhaps one of the most important considerations is to do with who bears the burden of our decision. A 2018 article published in Nature Climate Change estimated that tourism contributes to 8% of the world’s climate emissions, with those emissions likely to grow at the rate of 4% per annum. Of these emissions, 49% were attributable to transport alone. And this was just tourism.

One also needs to add to this the emissions of people, like me, largely travelling for reasons of work rather than leisure. One of the effects of the current global pandemic has been to reduce, to a massive degree, the level of emissions caused by travel. This is welcome news to those most likely to be affected by predicted changes caused by anthropogenic warming – notably those living on low-lying islands and others whose lives (and livelihoods) are at risk of devastating harm.

Yet, it’s easy enough to find advertisements enticing us to travel to the very same low-lying islands whose economies rely on tourism. The paradoxes don’t end there. Another criticism of tourism is that it tends to commodify the cultures of those most visited – and in some cases does so to the point of corruption. Those who mount this criticism argue that we should value the diversity of ‘pristine’ cultures in the same way that we value pristine diversity in nature. Retaining one’s culture free from influences from the wider world is not necessarily the choice that people living within those cultures would make for themselves. Some hold fast to an unsullied form of life. Others are keen to share their experience with the world – not only as a source of income, but also out of a very human sense of curiosity and a desire to share the human experience.

To make matters even more complex, not all travel is for reasons of leisure or work. It is sometimes driven by necessity or a sense of obligation to others, such as when joining a loved one who is sick or dying, or to attend a family ceremony. Even those obliged to travel have, of late, been asked to ‘think twice’ or, in some cases, had the decision taken out of their hands due to border closures that have allowed few (if any) exemptions. And even those few exemptions tend to have been offered only to the very rich, powerful or popular.

This might seem to suggest that we should calibrate our decisions about travel according to its purpose. If one can achieve the same outcome by other means (such as using a video conference rather than meeting in person), then that should be the preferred option. However, I have discovered that this approach only gets you so far (excuse the pun). Some meetings only really work if people are in the same room – especially if the issues require nuanced judgement and there are some obligations (like those owed to a sick or dying relative) that can only be discharged in person.

Despite this, the causes of climate change or life-threatening viruses don’t have any regard for our motives for travelling. A virus can just as easily hitch a ride with a person rushing to the side of an ailing parent as a person off to relax on a beach. All other things being equal, they have the same impact on the environment.

Given this, how should we approach the ethical dimension of travel?

First, I think we need to be ‘mindful travellers’. That is, we should not simply ‘get up and go’ just because we can. We need to think about the implications of our doing so – including the unintended, adverse consequences of whatever decision we make.

Second, we should seek to minimise the unintended, adverse consequences. For example, can we choose a mode of travel that has minimal negative impact? It is this kind of question driving people to explore new forms of low-carbon transport options.

Third, can we mitigate unintended harm – for example, by purchasing offsets (for carbon) or looking to support Indigenous cultures where we might encounter them?

Finally, can we maximise the good that might be done by our travelling?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The right to connect

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

ExplainerClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2021

Imagine for a second that the entire human race has gone extinct, with the exception of one man.

There is no hope for humankind to continue. We know, as a matter of certainty, that when this person dies, so too does the human race.

Got it? Good. Now, imagine that this last person spends their remaining time on Earth as an arbiter of extinction. Being themselves functionally extinct, they make it their purpose to eliminate, painlessly and efficiently, as much life on Earth as possible. Every living thing: animal, plant, microbe is meticulously and painlessly put down when this person finds it.

Intuitively, it seems like this man is doing something wrong. But according to New Zealand philosopher Richard Sylvan (though his argument was published under the name Richard Routley before he took his wife’s name when he married in 1983), traditional ethical theories struggle to articulate exactly why what they’re doing is wrong.

Sylvan, developing this argument in the 1960’s, argues that traditional Western ethics – which at the time consisted largely of variations of utilitarianism and deontology – rested on a single “super-ethic”, which states that people should be able to do what they wish, so long as they don’t harm anyone – or harm themselves irreparably.

A result of this super-ethic is that the dominant Western ethical traditions are “simply inconsistent with an environmental ethic; for according to it nature is the dominion of man and he is free to deal with it as he pleases,” according to Sylvan. And he has a point: traditional formulations of Western ethics have tended to exclude non-human animals (and even some humans) from the sphere of ethical concern.

Traditional formulations of Western ethics have tended to exclude non-human animals (and even some humans) from the sphere of ethical concern.

In fairness, utilitarianism has a better history with considering non-human animals. The founder of the theory, Jeremy Bentham, insisted that since animals can suffer, they deserve moral concern. But even that can’t criticise the actions of our last person, who delivers painless death, free of suffering.

Plus, most versions of utilitarianism focus on the instrumental value of things (basically, their usefulness). Rarely do we consider the fact that when we ask “is it useful?” we’re making an assumption about the user – that they’re human.

Immanuel Kant’s deontology begins with the belief that it is human reason that gives rise to our dignity and autonomy. This means any ethical responsibilities and claims only exist for those who have the right kind of ability: to reason.

Now, some Kantian scholars will argue that we still shouldn’t treat animals or the environment badly because it would make us worse people, ethically speaking. But that’s different to saying that the environment deserves our ethical consideration in its own right. It’s like saying bullying is wrong because it makes you a bad person, instead of saying bullying is wrong because it causes another person to suffer. It’s not all about you!

Sylvan describes this view as “human chauvinism”. Today, it’s usually called “anthropocentrism”, and it’s at the heart of Sylvan’s critique. What kind of a theory can condone the kind of pointless destruction that the Last Man thought experiment describes?

Since Sylvan published, a lot has changed – especially with regard to the animal rights movement. Indeed, Australian philosopher Peter Singer developed his own version of consequentialism precisely so he could address some of the problems the theory had in explaining the moral value of animals. And we can now pretty easily say that modern ethical theories would condemn the wholesale extinction of animal life from the planet, just because humans were gone.

But the questions go deeper than this. American philosopher Mary Anne Warren creates a similar thought experiment. Imagine a lab-grown virus gone wrong, that wipes out all human and animal life. That would be bad. Now, imagine the same virus, but one that wiped out all human, animal and plant life. That would, she thinks, be worse. But why?

What is it that gives plants their ethical status? Do they have intrinsic value – a value in and of themselves, or is their value instrumental – meaning they’re good because they help other things that really matter?

One way to think about this is to imagine a garden on a planet with no sentient life. Is it better, all things considered, for this garden to exist than not? Does it matter if this garden withers and dies?

Or to use a real-life example: who suffered as a result of the destruction of the Jukaan Gorge – a sacred site to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people? Western thought conceptualises this as wrong to destroy this site because it was sacred to people. But for Indigenous philosophical traditions, the destruction was a harm done to the land itself. The land was murdered. The suffering of people is secondary.

Sylvan and others who call for an ecological ethic, believe the failure for Western ethical thought to conceptualise of murdered land or what is good for plants is an obvious shortcoming.

This is revealed by our intuition that the careless destruction of the Last Man on Earth is wrong, even if we can’t quite say why.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How can we travel more ethically?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Space: the final ethical frontier

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 24 SEP 2020

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant once famously said “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and the more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within.”

It probably didn’t occur to Kant that there would come a day when the moral law and the starry heavens would find themselves in a staring contest with one another. In fairness though, it’s been almost 250 years since he wrote that quote. Today, those starry heavens play an increasingly important role in human affairs. And wherever there are people making decisions, ethical issues are sure to follow.

To get to know this final ethical frontier, I had a chat with Dr Nikki Coleman, Senior Chaplain Ethicist with the Australian Air Force. Nikki is a bona fide space ethicist to help us get up to (hyper) speed with all the new issues around ethics in space.

Is space an environment?

One of the largest contributions of the field of environmental ethics has been to encourage people to consider the environment as having value independent of its usefulness to humans. Before environmental ethics emerged as a field, many indigenous cultures and religions had already embedded these beliefs in the way they lived and related to land.

“The idea of space is that it’s a ‘global commons’,” says Coleman. “It belongs to all of us on the planet, but also to future generations. We can’t just dump space debris. We have to be careful about how we utilise resources. Like the resources on Earth, these resources are finite. They don’t go on forever,” she says.

This echoes one of the most common arguments about preservation and sustainability. We take care of the planet not just for ourselves, but for future generations. The challenge is helping people to understand that custodianship of space means thinking about the long tail on the decisions we make now. In fact, it might be even more difficult when it comes to space because, well, space is big, and it’s a long way away and we’ll likely never go there ourselves.

“What happens in space is the same as what happens on Earth, but it’s more remote,” Coleman tells me. And yet, despite this, what happens in space affects us profoundly. Just as we rely on trees, ecosystems and other aspects of the natural environment, we are reliant on parts of space as well. “Even though these objects feel further away from us, we still have an interdependency and a relationship with space,” explains Coleman.

What role should private companies play?

We’ve seen a lot of noise about space being made by private companies like SpaceX and Virgin – which is an enormous change from the time when travelling to space was something you could only do from a national space agency in a wealthy nation. But these companies have very different motivations for expanding into space.

“Space,” says Coleman “has become a very congested space.” “The cost of space operations has dramatically decreased, and we’re now seeing whole organisations devoted to their own space operations rather than as part of a government.”

This is where some issues can arise, “because what’s appropriate for a commercial operator in returning profits to stakeholders is not necessarily what’s appropriate for the whole of the planet.” Space is a ‘global commons’, it should be used to serve everyone’s interests – including future generations – not just the needs and wants of a single company or nation. It’s unclear to what extent commercial operators are taking the idea of a global commons seriously.

“We have someone like Elon Musk putting a car into space – which is the ultimate litter – or talking about putting 42,000 satellites into low-earth orbit, which obviously creates problems around congestion and space debris,” Coleman explains, referring to Elon Musk’s proposed ‘Starlink’, a network of satellites that could dramatically improve broadband speeds.

The interstellar garbage dump

Space debris is a big deal. We probably all remember in primary school learning about how different parts of a rocket break apart as they launch into space. Some of that burns up in the atmosphere, but lots of it remains in orbit. And it’s not just a few parts of rockets and a random Tesla. There is a lot of junk floating around in orbit around earth.

“Why that is problematic is it actually stays there for a really long period of time,” Coleman explains. “Some of it will decay in orbit and burn up in the atmosphere, but a lot of it could stay there for tens of thousands of years.”

But it’s not just that the debris sticks around. It’s that it can wreck a whole lot of important stuff whilst it orbits around the planet.

Coleman tells me that debris can interfere with our current satellites. ”The International Space Station is actually quite vulnerable. It only takes a small puncture to make it a life-threatening situation. And the issue is growing because we’re putting more and more satellites – including small satellites that don’t manoeuvre – into space.”

The worst-case scenario when it comes to space debris was depicted in the recent film Gravity, where the debris destroys satellites, generating even more space debris in a cascading process called Kessler Syndrome.

“The idea of having a whole area of space that is full of space debris will actually have massive impacts for the future,” Coleman warns. We use satellites for so many things: communication, food security, navigation… it’s not just about posting on Twitter and putting photos on Facebook.”

“The precursor for space debris is lots of things in space, so that’s why it’s problematic when someone talks about putting tens of thousands of satellites into orbit.”

The militarisation of space isn’t new

Coleman is quick to point out that space and the military have a long history. In fact, Sputnik was a Russian military satellite, which means “we have had a militarisation of space operations right from the get go.”

However, there are some changes in the way that militaries are thinking about space today. “Currently, military operations in space predominantly look at satellites and communication and dedicated military satellites for example, we’re with starting to see an increase in aggressive uses of military uses of space,” says Coleman.

The challenges here are myriad, but one significant one is that so much of what’s up in space is infrastructure that both civilians and the military need. Usually, the law and ethics of war don’t permit the targeting of infrastructure used by civilians when that would be disproportionately harmful to them.

“I would argue that a civilian satellite is not a legitimate target because it could have catastrophic effects for the civilians that rely on that satellite.”

“Space debris is climate change 2.0”

Ok, yes, we already talked about space debris but it’s so interesting we have to do it twice. See, space debris isn’t just garbage; it’s property.

“If you throw a bottle into the ocean, anyone can pick that up. That means that all the plastic in the middle of the ocean can actually be collected and recycled and made into something commercially viable,” Coleman explains. “But everything that goes into space is actually the property of the country that launched it.”

This means even if someone wanted to tidy up space, they couldn’t. Anyone can litter the global commons, but that doesn’t mean anyone can tidy it up. The rubbish belongs to someone.

This is where Coleman sees the analogy to climate change beginning. No one person or group can solve the problem. “We need to work together internationally to search to solve the problem of space debris,” she says. “I’m really excited that at the moment there is a large amount of discussion internationally about climate change, but there isn’t a lot being done around [space debris].”

The other, more frightening, climate change analogy is in terms of the threat posed by space debris. “It has the capacity to have a much faster impact on life on the planet,” says Coleman. “It could push us back to the 1950s.”

If there’s life on Mars, can we live there?

It seems interesting that at a time when many societies are coming to grips with the harms and problems colonisation has had around the world, there are people seriously contemplating the colonisation of Mars. For Coleman, this reveals one of the central ethical questions – not just for space, but in any walk of life. How far do our moral obligations extend?

“Do we have a duty not just to ourselves but to others as well, and do we have a responsibility to future generations of humans or potentially future generations of whatever is growing on Mars?”

We accept that we have obligations to future humans, but it seems quite different to say that we have obligations to a microbial life form on Mars. However, Coleman poses a further question: do we also have duties to whatever that microbial organism might evolve to be in millions of years?

“If we find life, do we owe it the opportunity to grow and develop into something that might eventually turn into intelligent life?”

I, for one, welcome our new microbial brothers and sisters.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 21 JUL 2020

Everyone, rich and poor alike, should be able to buy the cheapest product with a clean conscience.

This article was written for, and first published by The Guardian.

In the lead-up to a recent buck’s party, the group chat turned to the age-old question: will there be strippers? After some back and forth (for the record, I was opposed), the groom-to-be stepped in with the veto. “No strippers!” he declared.

His reasoning demonstrated a remarkable level of self-knowledge. He explained that he was planning on the weekend being filled with inhibition-reducing substances and didn’t trust his addled self to make smart decisions.

In doing so, he gave voice to a basic moral principle: better to avoid temptation than to overcome it. From Mufasa to Gandalf – and the Lord’s Prayer – we’re told that while it’s good to be able to resist vice when it calls to us, there’s wisdom in arranging our lives in a way that minimises our exposure to vice altogether.

Unfortunately, that advice is nearly impossible to follow when it comes to participating in the market. Increasingly our decisions around what we buy come with a trade-off: the more sustainable, ethical, fair trade option or the cheaper, potentially dodgier one.

Take an easy example: eggs. Do you want to buy them from the farms that give the chooks the best quality of life (comparably speaking)? Free range, organic and more than twice the price of the quick-and-dirty caged eggs stashed at the bottom of the shelves. For many of us, this is a fairly straightforward choice – the price to put our money where our morals are is relatively low, though even here, the lower your budget, the harder the ethical choice becomes. What happens when we increase the costs?

If we stop thinking with our stomachs, the problems get even larger. I recently informed my financial planner that I wanted to move my superannuation to an ethical investment fund. He did his job and showed me the comparison. If fees and returns for each fund performed as they had been, in 30 years’ time my superannuation would be $300,000 worse off investing in an ethical fund. Lead us not into temptation indeed.

There are a few perversities here. The most galling to me is that pitting money against morality is a regressive dilemma. The people who can most afford to pay their ethical way are the uber rich; those battling against the poverty line don’t have the option but to become complicit in animal wellbeing issues and clothing made in questionable conditions. They certainly can’t justify moving to a higher-fee fund just because it doesn’t invest in coal or tobacco.

There seems to be something uniquely cruel about creating a system that determines ethical seriousness by purchasing behaviour, thereby stigmatising the poor and lightening the load on the wealthy.

This only becomes more egregious when you consider the various ways in which wealth is accumulated under capitalism – often on the backs of the same workers who can’t afford not to be complicit in the ethical missteps that often end up lining the pockets of the very same elites who can then afford a clean conscience.

However, the choice remains difficult even for those who ostensibly can afford to take the financial hit for their ethics. It’s easy to compare the immediate, measurable and tangible cost difference of two products. Making a judgement regarding the vague, unquantifiable moral value of not investing in unethical practices or investing in exemplary ones is ambiguous. There’s no obvious benefit and thanks to the anonymity of the global market, we usually don’t see the harms inherent in the products we’re being offered. That’s a recipe for rationalising the choice that’s better for us and ours, no matter what the costs are to anonymous people, animals and ecosystems.

There appears to be little out for those wanting to be ethical consumers on a budget. Compromises and trade-offs will need to be made. You’ll likely need to benefit from practices that don’t align with what you think is right. However, the lie at the heart of the ethical consumption movement is to tell you this is your fault. It’s not. It’s the fault of a much larger system offering you choices that, in many cases, you simply shouldn’t be permitted to make.

I don’t want to be given the choice between forfeiting hundreds of thousands of dollars and compromising on my values. I don’t want to be offered the opportunity to buy clothes that are cheaper for me because disempowered workers paid the price in underpayment and subjugation. It’s too easy to justify the worse option. It’s too easy to be tempted.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Danielle Harvey The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

When we settled on Town Hall as the venue for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) 2020, my first instinct was to consider a choir. The venue lends itself to this so perfectly and the image of a choir – a group of unified voices – struck me as an excellent symbol for the activism that is defining our times.

I attended Spinifex Gum in Melbourne last year, and instantly knew that this was the choral work for the festival this year. The music and voices were incredibly beautiful but what struck me most was the authenticity of the young women in Marliya Choir. The song cycle created by Felix Riebel and Lyn Gardner for Marliya Choir embarks on a truly emotional journey through anger, sadness, indignation and hope.

A microcosm of a much larger phenomenon, Marliya’s work shows us that within these groups of unified voices the power of youth is palpable.

Every city, suburb and school has their own Greta Thurnbergs: young people acutely aware of the dangerous reality we are now living in, who are facing the future knowing that without immediate and significant change their future selves will risk incredible hardship.

In 2012, FODI presented a session with Shiv Malik and Ed Howker on the coming inter-generational war, and it seems this war has well and truly begun. While a few years ago the provocations were mostly around economic power, the stakes have quickly risen. Now power, the environment, quality of life, and the future of the planet are all firmly on the table. This has escalated faster than our speakers in 2012 were predicting.

For a decade now the FODI stage has been a place for discussing uncomfortable truths. And it doesn’t get more uncomfortable than thinking about the future world and systems the young will inherit.

What value do we place on a world we won’t be participating in?

Our speakers alongside Marliya Choir will be tackling big issues from their perspective: mental health, gender, climate change, indigenous incarceration, and governance.

First Nation Youth Activist Dujuan Hoosan, School Strike for Climate’s Daisy Jeffery, TEDx speaker Audrey Mason-Hyde , mental health advocate Seethal Bency and journalist Dylan Storer add their voices to this choir of young Australians asking us to pay attention.

Aged from 12 to 21, their courage in stepping up to speak in such a large forum is to be commended and supported.

With a further FODI twist, you get to choose how much you wish to pay for this session. You choose how important you think it is to listen to our youth. What value do you put on the opinions of the young compared to our established pundits?

Unforgivable is a new commission, combining the music from the incredible Spinifex Gum show I saw, with new songs from the choir and some of the boldest young Australian leaders, all coming together to share their hopes and fears about the future.

It is an invitation to come and to listen. To consider if you share the same vision of the future these young leaders see. Unforgivable is an opportunity to see just what’s at stake in the war that is raging between young and old.

These are not tomorrow’s leaders, these young people are trying to lead now.

Tickets to Unforgivable, at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Saturday 4 April are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

BY Danielle Harvey

Danielle Harvey is Festival Director of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. A curator, creative producer and director, Harvey works across live performance, talks, installation, and digital spaces, creating layered programs that connect deeply with audiences.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

This is what comes after climate grief

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Ketan Joshi The Ethics Centre 21 JAN 2020

I can’t really lie about this. Like so many other people in the climate community hailing from Australia, I expected the impacts of climate change to come later. I didn’t define ‘later’ as much other than ‘not now, not next year, but some time after that’.

Instead, I watched in horror as Australia burst into flames. As the worst of the fire season passes, a simple question has come to the fore. What made these bushfires so bad?

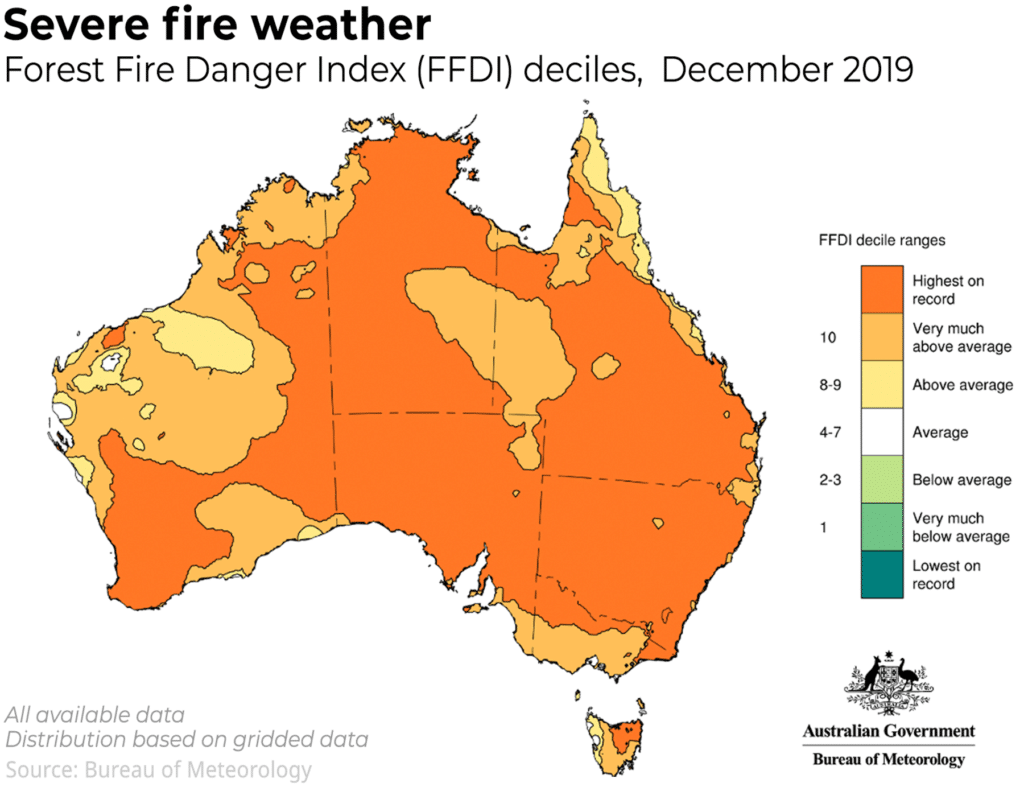

The Bureau of Meteorology confirms that weather conditions have been tilting in favour of worsening fire for many decades. The ‘Forest Fire Danger Index’, a metric for this, hit records in many parts of Australia, this summer.

The Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub is unequivocal: “Human-caused climate change has resulted in more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires in recent decades for many regions of Australia…These trends are very likely to increase into the future”.

Bushfire has been around for centuries, but the burning of fossil fuels by humans has catalysed and worsened it.

Having moved away from Australia, I didn’t experience the physical impacts of the crisis. Not the air thick with smoke, or the dark brown sky or the bone-dry ground.

But I am permanently plugged into the internet, and the feelings expressed there fed into my feed every day. There was shock at the scale and at the science fictionness of it all. Fire plumes that create their own lightning? It can’t be real.

The world grieved at the loss of human life, the loss of beautiful animals and ecosystems, and the permanent damage to homes and businesses.

Rapidly, that grief pivoted into action. The fundraisers were numerous and effective. Comedian Celeste Barber, who set out to raise an impressive $30,000 AUD, ended up at around $51 million. Erin Riley’s ‘Find a Bed’ program worked tirelessly to help displaced Australians find somewhere to sleep. Australians put their heads down and got to work.

It’s inspiring to be a part of. But that work doesn’t stop with funding. Early estimates on the emissions produced by the fires are deeply unsettling. “Our preliminary estimates show that by now, CO2 emissions from this fire season are as high or higher than the CO2 emissions from all anthropogenic emissions in Australia. So effectively, they are at least doubling this year’s carbon footprint of Australia”, research scientist Pep Canadell told Future Earth.

There is some uncertainty about whether the forests destroyed by the blaze will grow back and suck that released carbon back into the Earth. But it is likely that as fire seasons get worse, the balance of the natural flow of carbon between the ground and the sky will begin to tip in a bad direction.

Like smoke plumes that create their own ‘dry lightning’ that ignite new fires, there is a deep cyclical horror to the emissions of bushfire.

It taps into a horror that is broader and deeper than the immediate threat; something lingers once the last flames flicker out. We begin to feel that the planet’s physical systems are unresponsive. We start to worry that if we stopped emissions, these ‘positive feedbacks’ (a classic scientific misnomer) mean we’re doomed regardless of our actions.

“An epidemic of giving up scares me far more than the predictions of climate scientists”, I told an international news journalist, as we sat in a coffee shop in Oslo. It was pouring rain, and it was warm enough for a single layer and a raincoat – incredibly strange for the city in January.

She seemed surprised. “That scares you?” she asked, bemused. Yes. If we give up, emissions become higher than they would be otherwise, and so we are more exposed to the uncertainties and risks of a planet that starts to warm itself. That is paralysing, to me.

It is scarier than the climate change denial of the 2010s, because it has far greater mass appeal. It’s just as pseudoscientific as denialism. “Climate change isn’t a cliff we fall off, but a slope we slide down”, wrote climate scientist Kate Marvel, in late 2018.

In response to Jonathan Franzen’s awful 2019 essay in which he urges us to give up, Marvel explained why ‘positive feedbacks’ are more reason to work hard to reduce emissions, not less. “It is precisely the fact that we understand the potential driver of doom that changes it from a foregone conclusion to a choice”.

A choice. Just as the immediate horrors of the fires translated into copious and unstoppable fundraising, the longer-term implications of this global shift in our habitat could precipitate aggressive, passionate action to place even more pressure on the small collection of companies and governments that are contributing to our increasing danger.

There are so many uncertainties inherent in the way the planet will respond to a warming atmosphere. I know, with absolute certainty, that if we succumb to paralysis and give up on change, then our exposure to these risks will increase greatly.

We can translate the horror of those dark red months into a massive effort to change the future. Our worst fears will only be realised if we persist with the intensely awful idea that things are so bad that we ought to give up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY Ketan Joshi

Was a speaker at IQ2: It's too soon to ditch fossil fuels. He is a science communicator with over eight years experience across The Monthly, Gizmodo, Cosmos and with the CSIRO.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A burning question about the bushfires

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

At the height of the calamity that has been the current bushfire season, people demanded to know why large parts of our country were being ravaged by fires of a scale and intensity seldom seen.

In answer, blame has been sheeted home to the mounting effects of climate change, to failures in land management, to our burgeoning population, to the location of our houses, to the pernicious deeds of arsonists…

However, one thing has not made the list, ethical failure.

I suspect that few people have recognised the fires as examples of ethical failure. Yet, that is what they are. The flames were fuelled not just by high temperatures, too little rain and an overabundance of tinder-dry scrub. They were also the product of unthinking custom and practice and the mutation of core values and principles into their ‘shadow forms’.

Bushfires are natural phenomena. However, their scale and frequency are shaped by human decisions. We know this to be true through the evidence of how Indigenous Australians make different decisions – and in doing so – produce different effects.

Our First Nations people know how to control fire and through its careful application help the country to thrive. They have demonstrated (if only we had paid attention) that there was nothing inevitable about the destruction unleashed over the course of this summer. It was always open to us to make different choices which, in turn, would have led to different outcomes.

This is where ethics comes in. It is the branch of philosophy that deals with the character and quality of our decisions; decisions that shape the world. Indeed, constrained only by the laws of nature, the most powerful force on this planet is human choice. It is the task of ethics to help people make better choices by challenging norms that tend to be accepted without question.

This process asks people to go back to basics – to assess the facts of the matter, to challenge assumptions, to make conscious decisions that are informed by core values and principles. Above all, ethics requires people to accept responsibility for their decisions and all that follows.

This catastrophe was not inevitable. It is a product of our choices.

For example, governments of all persuasions are happy to tell us that they have no greater obligation than to keep us safe. It is inconceivable that our politicians would ignore intelligence suggesting that a terrorist attack might be imminent. They would not wait until there was unanimity in the room. Instead, our governments would accept the consensus view of those presenting the intelligence and take preventative action.

So, why have our political leaders ignored the warnings of fire chiefs, defence analysts and climate scientists? Why have they exposed the community to avoidable risks of bushfires? Why have they played Russian Roulette with our future?

It can only be that some part of society’s ‘ethical infrastructure’ is broken.

In the case of the fires, we could have made better decisions. Better decisions – not least in relation to the challenges of global emissions, climate change, how and where we build our homes, etc. – will make a better world in which foreseeable suffering and destruction is avoided. That is one of the gifts of ethics.

Understood in this light, there is nothing intangible about ethics. It permeates our daily lives. It is expressed in phenomena that we can sense and feel.

So, if anyone is looking for a physical manifestation of ethical failure – breathe the smoke-filled air, see the blood-red sky, feel the slap from a wall of heat, hear the roar of the firestorm.

The fires will subside. The rains will come. The seasons will turn. However, we will still be left to decide for the future. Will our leaders have the moral courage to put the public interest before their political fortunes? Will we make the ethical choice and decide for a better world?

It is our task, at The Ethics Centre, to help society do just that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 6 JUN 2019

IQ2 Australia debates whether we need to ‘Stop Idolising Youth’ on 12 June.

Advertisers market to youth despite boomers having the strongest buying power. Unlike professions such as law and medicine, the creative industries prefer ‘digital natives’ over experience.

Young actors play mature aged characters. Yet openly teasing the young for being entitled and lazy is a popular social sport. Are the ageism insults flung both ways?

1. Why do marketers hate old people?

Ad Contrarian, Bob Hoffman / 2 December 2013

An oldie but a goodie. Bob Hoffman is the entertainingly acerbic critic of marketing and author of books like Laughing@Advertising. In this blog post he aims a crossbow at the seemingly senseless predilection of advertisers for using youth to market their products when older generations have more money and buy more stuff.

“Almost everyone you see in a car commercial is between the ages of 18 and 24,” he says. “And yet, people 75 to dead buy five times as many new cars as people 18 to 24.” He makes a solid argument.

2. It’s time to stop kvetching about ‘disengaged’ millennials

Ben Law, The Sydney Morning Herald / 27 October 2017

Ben Law asks, “Aren’t adults the ones who deserve the contempt of young people?” He argues it is older generations with influence and power who are not addressing things as big as the non-age-discriminatory climate crisis. He also shares some anecdotes about politically engaged and polite public transport riding kids.

You might regard a couple of the jokes in this piece leaning toward ageist quips but Law is also making them at his own expense. He points out millennials – the generation to which he belongs and the usual target for jokes about entitled youth – are nearing middle age.

3. Let’s end ageism

Ashton Applewhite, TED Talk / April 2017

There’s something very likeable about Ashton Applewhite – beyond her endearing name. This is even though she opens her TEDTalk with the confronting fact the one thing we all have in common is we’re always getting older. Sure, we’re not all lucky enough to get old, but we constantly age.

In pointing to this shared aspect of humanity, Applewhite makes the case against ageism. This typically TED nugget of feel good inspiration is great for every age. And if you’re anywhere between late 20s and early 70s, you’ll love the happiness bell curve. In a nutshell: it gets better!

4. Instagram’s most popular nan

Baddiewinkle, Instagram/ Helen Van Winkle

Her tagline is “stealing ur man since 1928”. Get lost in a delightful scroll through fun, colourful images from a social media personality who does not give a flying fajita for “age appropriate” dressing or demeanours. Baddie Winkle was born Helen Ruth Elam Van Winkle in Kentucky over 90 years ago.

Her internet stardom began age 85 when her great granddaughter Kennedy Lewis posted a photo of her in cut-off jeans and a tie-dye tee. Now Winkle’s granddaughter Dawn Lewis manages her profile and bookings. Her 3.8 million followers show us audiences aren’t only interested young social media influencers. “They want to be me when they get older,” Winkle says. Damn right we do.

Event info

IQ2 Australia makes public debate smart, civil and fun. On 12 June two teams will argue for and against the statement, ‘Stop Idolising Youth’. Ad writer Jane Caro and mature aged model Fred Douglas take on TV writer Ben Jenkins and author Nayuka Gorrie. Tickets here.

MOST POPULAR

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

An ethical dilemma for accountants

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

ArticleBeing Human