Why leisure matters for a good life, according to Aristotle

Why leisure matters for a good life, according to Aristotle

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Ross Channing Reed 4 DEC 2025

In his powerful book “The Burnout Society,” South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that in modern society, individuals have an imperative to achieve. Han calls this an “achievement society” in which we must become “entrepreneurs” – branding and selling ourselves; there is no time off the clock.

In such a society, even leisure risks becoming another kind of work. Rather than providing rest and meaning, leisure is often competitive, performative and exhausting.

People feeling pressure to self-promote, for example, might spend their free time posting photos of an athletic race or an elaborate vacation on social media to be viewed by family, friends and potential employers, adding to exhaustion and burnout.

As a philosopher and philosophical counselor, I study connections between unhealthy forms of leisure and burnout. I have found that philosophy can help us navigate some of the pitfalls of leisure in an achievement society. The celebrated Greek philosopher Aristotle, who lived from 384 to 322 B.C.E., in particular, can offer important insights.

Aristotle on self-development

Aristotle begins the famous Nicomachean Ethics by pointing out that we are all searching for happiness. But, he says, we are often confused about how to get there.

Aristotle believed that pleasure, wealth, honour and power will not ultimately make us happy. True happiness, he said, required ethical self-development: “Human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue.”

In other words, if we want to be happy, Aristotle contended, we must make reasoned choices to develop habits that, over time, become character traits such as courage, temperance, generosity and truthfulness.

Aristotle is explicitly linking the good life to becoming a certain kind of person. There is no shortcut to ethical self-development. It takes time – time off the clock, time not engaged in some kind of entrepreneurial self-promotion.

Aristotle is also telling us about the power of our choices. Habits, he argues, are not just about action, but also motives and character. Our actions, he says, actually change our desires. Aristotle says: “By abstaining from pleasures we become temperate, and it is when we have become so that we are most able to abstain from them.”

In other words, good habits are the result of moving incrementally in the right direction through practice.

For Aristotle, good habits lead to ethical self-development. The converse is also true. To this end, for Aristotle, having good friends and mentors who guide and support moral development are essential.

How Aristotle helps us understand leisure

In an achievement society, we are often conditioned to respond to external pressures to self-promote. We may instead look to pleasure, wealth, honour and power for happiness. This can sidetrack the ethical development required for true happiness.

True leisure – leisure that is not bound to the imperative to achieve – is time we can reflect on our real priorities, cultivate friendships, think for ourselves, and step back and decide what kind of life we want to live.

The Greek word eudaimonia, often translated simply as happiness, is the term Aristotle uses to describe human thriving and flourishing. According to philosopher Jane Hurly, Aristotle views “leisure as essential for human thriving”. Indeed, “for both Plato and Aristotle leisure… is a prerequisite for the achievement of the highest form of human flourishing, eudaimonia”, as philosopher Thanassis Samaras argues.

While we may have limited means to acquire pleasure, wealth, honour and power, Aristotle tells us that we have control over the most important variable in the good life: what kind of person we will become. Leisure is crucial because it is time in which we get to decide what kind of habits we will develop and what kind of person we will become. Will we capitulate to achievement society? Or utilise our free time to develop ourselves as individuals?

When leisure is preoccupied with entrepreneurial self-promotion, it is difficult for moral development to take place. Free time that is not hijacked by the imperative to achieve is required for the development of a consistent relationship to oneself – what I call a relationship of self-solidarity – a kind of reflective self-awareness necessary to aim at the right target and make moral choices. Without such a relationship, the good life will remain elusive.

Leisure reimagined

Rather than adopting the achievement society’s formulation of the good life, we may be able to formulate our own vision. Without one’s own vision, we risk becoming mired in bad habits, leading us away from the moral development through which the good life becomes possible.

Aristotle makes it clear that we have the power to change not only our behaviours but our desires and character. This self-development, as Aristotle writes, is a necessary part of the good life – a life of eudaimonia.

The choices we make in our free time can move us closer to eudaimonia. Or they could move us in the direction of burnout.

The article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Ross Channing Reed

Ross Channing Reed, Ph.D., teaches philosophy at Missouri University of Science and Technology. His areas of research include philosophical psychology and philosophical counselling, addiction, trauma, existentialism, ethics, and philosophy of religion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Lee-Anne Courtney 20 OCT 2025

I first came across the term moral injury during a work break, scrolling through Bond University’s research page, my casual employer at the time.

It sounded vaguely religious and a bit dramatic, and it sparked my curiosity. The article explained that moral injury is a term given to a form of psychological trauma experienced when someone is exposed to events that violate or transgress their deeply held beliefs of right and wrong, leading to biopsychosocial suffering.

First used in relation to military service, moral injury was coined by military psychiatrist Jonathan Shay (2014) when he realised that therapy designed to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) wasn’t effective for all service members. Shay used the term moral injury to describe a deeper wound carried by his patients, not from fear for their physical safety, but from violating their own morals or having them violated by leaders. The suffering experienced from exposure to violence was compounded by the damage to their identity and feeling like they’d lost their worth or goodness in the eyes of society and themselves. Insight into this hidden cost of trauma was an epiphany for me.

I’m a secondary teacher by profession, but I’ve not been employed in the classroom for over 10 years. In fact, I haven’t been employed doing anything other than the occasional casual project since that time. Why? Was it burnout, stress, compassion fatigue, lack of resilience, or the ever-handy catch-all, poor mental health? No matter which explanation I considered, the result was the same: a growing sense of personal failure and creeping doubt about whether I’m cut out for any kind of paid work. Being introduced to the term moral injury was like turning a kaleidoscope; all the same colours tumbled into a dazzlingly different pattern. It gave me a fresh lens through which to view my painful experience of leaving the teaching profession. I needed to know more about moral injury, not only for myself, but also for my colleagues, the students and the profession that I love.

If just a glimpse of moral injury gave me hope that my distress in my role as a teacher wasn’t simply personal failure, imagine the impact a deep, shared understanding could have on our education system and wider community.

Within the month, I had written and submitted a research proposal to empirically investigate the impact of moral injury on teacher wellbeing in Australia.

I discovered moral injury, while well-studied in various workforce populations, had received limited but significant empirical attention in the teaching profession. My research clearly showed that moral injury has a serious negative impact on teachers’ wellbeing and professional function. Crucially, it offered insight into why many teachers were experiencing intense psychological distress and a growing urge to leave the profession, even when poor working conditions and eroding public respect were the subject of policy and practice reform.

What makes an event or situation potentially morally injurious is when it transgresses a deeply held value or belief about what is right or wrong. Research exploring moral injury in the teaching practice suggests that teachers hold shared values and beliefs about what good teaching means. Education researchers such as Thomas Albright, Lisa Gonzalves, Ellis Reid and Meira Levinson affirm that teachers aim to guide all students in gaining knowledge and skills while shaping their thinking and behaviour with an awareness of right and wrong, promoting social justice and challenging injustice. Researcher Yibing Quek highlights the development of respectful, critical thinking as a core educational goal that supports students in navigating life’s challenges. Scholars such as Erin Sugrue, Rachel Briggs, and L. Callid Keef-Perry emphasise that the goals of education are only achievable through relationships rooted in deep care, where teachers are responsive to students’ complex learning and wellbeing needs and attuned to ethical dilemmas requiring both compassion and justice. Though ethical dilemmas are inherent in teaching, researcher Dana Cohen-Lissman argues that many are generated from externally imposed policies, potentially leading to moral injury among teachers.

Studies assert that teachers experience moral injury when systemic barriers and practice arrangements keep them from aligning their actions with their professional identity, educational goals, and core teaching values. Teachers exposed to the shortcomings of education and other systems often feel they are complicit in the harm inflicted on students. Researchers have consistently identified neoliberalism, social and educational inequities, racism, and student trauma as key factors contributing to experiences that lead to moral injury for teachers. These systemic problems place crippling pressure on individual teachers, both in the classroom and in leadership, to achieve the stated goals of education, despite policies that provide insufficient and unevenly distributed resources to do so.

Furthermore, the high-stakes accountability demanded of individual employees fails to recognise the collective, community-oriented, interdependent nature of the work of teaching. The problem is that the gap between what is expected of teachers and what they can do is often blamed on them, and over time, they start to believe it of themselves. Naturally, these morally injurious experiences cause emotional distress, hinder job performance, and gradually erode teachers’ wellbeing and job satisfaction.

Experiencing moral distress, witnessing harm to children, feeling betrayed by policymakers and the public, powerless to make meaningful change, and working without the rewards of service, teachers face difficult choices. They can respond to moral injury by quietly resisting, speaking out to demand understanding and systemic change or take what they believe to be the only ethical choice – leave the profession of teaching. But what if, instead of facing these difficult choices, teachers resorted to reductive moral reasoning – simplifying the complex ethical dilemmas piling up around them or ignoring them altogether – so they wouldn’t be disturbed by them? Numbing ethical sensitivity just to keep a job creates even more problems.

Moral injury goes beyond personal failure or inadequacy; it acknowledges the broader systemic conditions that place teachers in situations where their ethical commitments increasingly clash with the neoliberal forces currently shaping education. Moral injury offers a language of lament, an explanation for the anguish experienced in the practice of teaching. An understanding of moral injury in the education sector invites society, collectively, to offer teachers fierce compassion and moral repair by restructuring the social systems that create these conditions. Adding moral injury to the discourse around teacher shortages may even help teachers offer fierce compassion to themselves. It did for me.

BY Lee-Anne Courtney

Lee-Anne Courtney is a secondary teacher with over 30 years of experience in the education sector. She is conducting PhD research with a team at Bond University aimed at uncovering the impact of moral injury on teacher wellbeing in Australia.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Tim Dean 13 OCT 2025

Caring for others can be a joy as well as a burden. Here’s how to balance your duty to care for others in your life with your own right to live a full life.

Sue’s* father, Jack*, isn’t like he used to be. Since his stroke, Jack has been forgetful, irritable and he gets even more frustrated when he gets confused, which happens often. He is increasingly reliant on Sue’s care these days. She prepares his meals, does his laundry and bathes him when he’s too tired to do it himself. Meanwhile, Sue’s children – both of whom have just started high school – have issues of their own that require her attention.

Sue has had to reduce her hours at work, right before she was slated for a promotion to a senior role. The reduction in income has compounded the significant cut to her free time; she now spends most days looking after Jack, even though he seems thoroughly ungrateful for her care, as well as keeping her kids on track.

There are times when Sue thinks about moving Jack into a nursing home, even though she knows he’d resist. But she longs to return to work, which was a tremendous source of meaning for her, and she hasn’t seen her friends in months. Such thoughts fill her with guilt, and she quickly puts them aside. But she’s not sure how much longer she can go on like this. It’s certainly far from the life she envisaged for herself at this age.

While the names have been changed*, this scenario is based on a true story. Actually, many true stories. One of the most popular questions posed by callers to our Ethi-call service is how to balance our responsibility to care for others with our own rights to live our life. And it’s one of the most complex questions to answer. However, there are some key considerations that can help people facing this dilemma to decide on an ethical way forward, one that respects both the duties that they have to others as well as their own right to live a good life.

Finding the right balance

Caring for others is a fundamental part of the human experience. We naturally feel empathy and concern for people close to us, especially for loved ones and those who are vulnerable or unable to fully care for themselves. But we also have rights of our own that need to be taken into consideration.

While some philosophers argue that every human’s moral worth is equal, and that we ought to weigh everyone’s needs equally, others have argued that we have special relationships with some people – such as parents with their children, or spouses with each other – and those relationships imply special obligations to those individuals.

This ‘ethic of care’ says that we ought to prioritise the interests of people we have a special relationship with over the interests of others. It also says we have a special duty to care for those people, especially when they are vulnerable or cannot care for themselves.

We can see this sense of duty in the words of Kim Paxton, who was caring for her husband, Graham, after he was diagnosed with a serious medical condition, while waiting on governmental support. “You just do it,” she told The Guardian Australia. “I don’t know. You get tired, but they’re your family, your loved ones. It breaks my heart … It’s a bit like being a mum, isn’t it, with a newborn baby. You start living with less sleep and you work harder and you just do what you do for the love of your kids.”

Some philosophers also emphasise the role of rights and duties when it comes to thinking about the care we give. Rights are a kind of entitlement that each person has in order to be treated a particular way. For example, a right to dignity means we are entitled to be treated in ways that don’t diminish our dignity. If someone has a right, others have a duty to respect that right.

We can also have duties because of the social role or relationship we have. For example, a doctor has a duty to protect their patient’s interests by virtue of their professional role, and a parent has a duty to support their children until they are old enough to support themselves. Similarly, some people have a duty to care for a family member if they are unable to care for themselves.

However, rights and duties often come into conflict. A caregiver might have a duty to care for both children and elderly parents, and it might be impossible for them to satisfy both of those obligations to everyone’s satisfaction. In that case, it’s reasonable to appeal to the adage “ought implies can” – meaning if it’s impossible to do something, then you’re free from blame if you’re unable to do it. That might mean balancing your care among multiple people and managing expectations of what you can reasonably achieve.

What about me?

But duties don’t necessarily override all other concerns. We also have a right to pursue our own interests and our vision of a good life, and this right can be balanced with the rights of others to be cared for by us. Each of us has a right to agency, meaning our ability to act on our interests and desires. One reason we might care for others is to help remove the barriers that prevent them from exercising their agency.

But it’s important for us to also have agency, and that might mean not expending all of our time and energy on care.

It’s also important that those receiving care don’t morally impose on their caregivers by expecting an unreasonable degree of sacrifice on their behalf. If there are alternatives that can reduce the burden of care they place on family members, such as external help or respite care, then it could be important to explore those options, even if it isn’t their first preference.

There is also a pragmatic argument for placing boundaries on the care you give: if you want to ensure you are delivering the best care possible, you need to have the energy to actually deliver that care. If you become burnt out, you’re not able to satisfy your obligations to care for others.

To ensure you don’t run flat, you might need to devote some resources to self-care. That might mean taking a break from time to time, perhaps taking a relaxing holiday. Even if that feels indulgent, there’s no guilt in taking the time to recharge the batteries so you can return to our caring duties reinvigorated.

It can be difficult in practice to balance conflicts of interest or duties. However, there can be good ethical reasons to place some boundaries and set expectations on the care you give to others.

Tough decisions are a part of life, but you don’t have to make them alone. Ethi-call, a free independent helpline from The Ethics Centre, can help you find a path forward. Book now.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Kathryn MacKay 1 OCT 2025

What do the recent Optus 000-incidents, childcare centre abuse allegations, and the Northern Beaches Hospital deaths have in common?

Each of these incidents plausibly resulted from the privatisation of public services, in which the government has systematically disinvested funds and withdrawn oversight.

On the 18th of September, Optus’ 000 service went down for the second time in two years. This time, the outage affected people in Western Australia, and as a result of not being able to get through to the 000 service, it appears that three people have died.

This highlights a more general issue that we see in Australia across a range of public services, including emergency, hospital, and childcare services. The government has sought to privatise important parts of the care economy that are badly suited to generating private profits, leading to moral and practical problems.

Privatisation of public services

Governments in Australia follow economic strategies that can be described as neoliberal. This means that they prefer limited government intervention and favour market solutions to match the value that people are willing to pay with the value that people want to charge for goods and services.

As a result, public goods and services like healthcare, energy, and telecommunications have been gradually sold off in Australia to private companies. This is because, firstly, it’s not considered within the government’s remit to provide them, and secondly, policy makers think the market will provide more efficient solutions for consumers than the government can.

We see then, for example, a proliferation of energy suppliers popping up, offering the most competitive rates they can for consumers against the real cost of energy production. And we see telecommunications companies, like Telstra and Optus, emerging to compete for consumers in the market of cellular and internet services.

So far, so good. In principle, these systems of competition should drive companies to provide the best possible services for the lowest competitive rates, which would mean real advantages for consumers. Indeed, many have argued that governments can’t provide similar advantages for consumers, given that they end up with no competition and no drive for technical improvements.

However, the picture in reality is not so rosy.

Public services: Some things just can’t be privatised

There’s a term in economics called ‘market failure’. This describes a situation where, for a few different possible reasons, the market fails to efficiently respond to supply and demand flows, affecting the nature of public goods and services.

A classic public good has two features: it is non-rival, and non-excludable. A non-rival good is one where one person’s use doesn’t deplete how much of that good is left for others – so we are not rivals because there is enough for everyone. A non-excludable good is one where my use of it doesn’t prevent anyone else from using it either. So, I can’t claim this good because I’m using it right now; it remains open to others to use.

Consider a jumper. This is a rival and excludable good. If I purchase a jumper out of a stock of jumpers, there are fewer jumpers for you and everyone else who wants one. The jumper is a rival good. When I buy the jumper and wear it, no one else can buy it or wear it; it is an excludable good.

Now, consider the 000 service. In theory, if you and I are both facing an emergency, we can both call 000 and get through to an operator. The 000 service is a non-rival, non-excludable good. It is not the sort of thing that anyone can deplete the stock of, nor can anyone exclude anyone else from using it.

Such goods and services present a problem for the market. Private companies have little reason to provide public goods or services, like roads, street lights, 000 services, clean air, or public health care. That’s because these sorts of goods don’t return them much of a profit. There is little or no reason that anyone would pay to use these services when they can’t be excluded from their use and their stock won’t be depleted. Of course, that has not stopped governments from trying to privatise these things anyway, as we see from toll roads, 000, and private care.

Public goods, private incentives

The primary moral problem that arises in the privatisation of public goods and services is two-fold. First, it puts the provision of important goods and services in the hands of companies whose interests directly oppose the nature of the goods to be provided. Second, people are made vulnerable to an unreliable system of private provision of public goods and services.

A private company’s main objective is to make the most possible profit for shareholders. Given that public goods will not make much of a profit, there is little incentive for a private company to give them attention. This means that essential goods and services, like the 000 service, are deprioritised in favour of those other services that will make the company more of a profit.

Further, people become vulnerable to unreliable service providers, as proper oversight and governance undercuts the profit of private companies. Any time a company has to pay for staff re-training, for revision of protocols, or firing and replacing an employee, they make their profits smaller. So, private companies have incentives to cut corners where they can, and oversight, governance, and quality control seem to be the most frequent things to go.

Most of the time, these cut corners go unnoticed. Until, that is, something goes wrong with the service and people get hurt, or worse.

So why does this system continue?

Successive governments have made the decision to privatise goods and services, making their public expenditures smaller and therefore also making it look like they are being more ‘responsible’ with tax revenues. It’s an attractive look for the neoliberal government, which emphasises how small and non-interventionist it is. But is it working for Australians?

It seems like the government’s quest for a smaller bottom line is at odds with the needs of Australian people. The stable provision of a 000 service, safe hospitals with appropriate oversight, and reliable childcare services with proper governance are all essential goods that Australians want, and which private companies consistently seem unable to provide.

It’s a moral – if not economic – imperative that Australian governments reverse course and begin to provide essential goods and services again. The 000 service, the childcare system, and hospitals provide only a few examples of where the government’s involvement in providing public services is very obviously missing. People are getting hurt, and people are dying, for the sake of private profits.

BY Dr Kathryn MacKay

Kathryn is a Senior Lecturer at Sydney Health Ethics, University of Sydney. Her background is in philosophy and bioethics, and her research involves examining issues of human flourishing at the intersection of ethics, feminist theory and political philosophy. Kathryn’s research is mainly focussed on developing a theory of virtue for public health ethics, and on the ethics of public health communication. Her book Public Health Virtue Ethics is forthcoming with Routledge.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Women’s pain in pregnancy and beyond is often minimised

Women’s pain in pregnancy and beyond is often minimised

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Laura Kotevska 1 OCT 2025

Some recent discussions of pain relief during pregnancy frame the issue of paracetamol use as a maternal-foetal conflict, ignoring science, eroding trust in doctors, dismissing women’s pain, and limiting women’s autonomy. ‘Toughing it out’ is not the answer.

Last week, US president Donald Trump held a press conference announcing the results of his administration’s investigations into the root causes of autism. During the event, he shared several recommendations for the use of acetaminophen (paracetamol) in pregnancy, namely that women should not use it.

Medical experts have criticised the claims as dangerous and poorly informed, and researchers have shown that the recommendations are politicised interpretations of weaker medical studies. In Australia, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ recommendations for paracetamol use in pregnancy remain unchanged.

While most expert attention has been paid to debunking the administration’s claims and communicating insights from our best scientific knowledge on the topic, less attention has been given to the tenor of the president’s announcement. How can the ethics of pregnancy help us to understand the rhetorical moves of this speech and how we treat women in pregnancy and beyond?

The ethics of pregnancy care

Trump’s recommendation to avoid paracetamol use in pregnancy is predicated on the assumption that doing so is harmful to the foetus. In this instance, it is recommended that a pregnant woman avoid pain relieving medication on the basis that it may cause autism. Putting aside the fact that there is little evidence of the harmful effects of paracetamol use in pregnancy, the White House press conference framed this issue as a maternal-foetal conflict – an instance of maternal interests (in pain or fever relief) conflicting with the interests of the foetus (of not developing autism). According to the White House, the maternal-foetal conflict should be resolved in favour of the foetus with the recommendation that paracetamol use be avoided in all but the most severe cases. In medicine and maternal decision making, prioritising the foetus is very common, but is hardly a foregone conclusion.

Yet in this instance, and in many other obstetric cases, the central conflict is not between the mother and foetus, but between the mother and others who believe they know better.

Here, the adversary is the White House, and the effect of their remarks is the erosion of trust between the pregnant patient and their physician. This is because the pregnant woman must now contend with information that may contradict her doctor’s advice. Such intervention is “counter-productive relative to the goal of promoting foetal health”, researchers Baylis, Rodgers and Young inform us, since this erosion of trust prevents doctors from providing “the education which would promote the birth of healthier babies”.

Secondly, the maternal-foetal conflict framing ignores the fact that the interests of mother and foetus are inextricably linked. Currently, many health experts are at pains to communicate that paracetamol is a safe for treating fevers and providing pain relief, and that sustained fevers in pregnancy can result in miscarriage, birth malformations and, later, still birth while untreated significant pain can also result in complications. Even in cases where there are certain risks to a foetus, withholding or delaying treatment can potentially lead to increased maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. The White House’s rhetoric simplifies the often challenging or agonising decisions women and their physicians routinely make during pregnancy.

These examples show that protecting a woman’s health is oftentimes the strongest path to guaranteeing foetal and neonatal outcomes. More than this, recommendations that are laden with unscientific bias erode trust in physicians and limit a woman’s capacity to make informed choices, infringing upon women’s autonomy and potentially risking greater foetal harm.

Toughing it out

It was the experience of giving birth that led the author Anushay Hossain to reflect on the treatment of women’s pain. In The Pain Gap, she writes “Doctors still don’t always believe women when they describe their pain, or they dismiss women’s symptoms as being psychosomatic.” For Hussain, the concept of hysteria is useful to explaining a woman’s experience of the medical system. The common characterisation of women’s pain as hysterical, she writes, shifts blame and judgment onto women. The conversation becomes ‘is your pain real? Is it that bad? Why can’t you cope with it?’

This was the text and subtext of the White House press conference last week. On many occasions in his speech and responses to media outlets, Trump told women to ‘tough it out.’ And if you can’t tough it out? “You know, it’s easy for me to say tough it out, but sometimes in life where a lot of other things, you have to tough it out also. Don’t take Tylenol.” Once again, the blame for pain falls at the feet of women.

Setting aside the aforementioned evidence that women ‘toughing it out’ leads to worse outcomes for their foetuses, telling women to tolerate their pain is not only cruel, but also an example of medical misogyny. Medical misogyny describes the gendered ways patients experience healthcare, often marked by missed diagnoses, delayed treatments, and the dismissal or minimisation of symptoms, including but is not limited to pain. It is startlingly common in Australia with 2 out of 3 women reporting experiences of discrimination in healthcare. For non-white women, the experience is worse.

How should we respond?

To address these widespread issues, governments in Australia and the United Kingdom, among others, have established inquiries into women’s pain and reproductive health. More recently, the Sydney Morning Herald has collected patient testimonies that detail women’s experiences of medical misogyny, bringing about wider awareness of the issue and adding urgency to the call for systemic change.

At a time when many individuals and institutions are working to dismantle the gendered and racial barriers to accessing quality healthcare, dismissing women’s suffering and asking them to ‘tough it out’ reinforces a long history of medical misogyny that leaves women unheard, untreated and unwell.

BY Laura Kotevska

Laura Kotevska is Senior Lecturer in the Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor Education and Discipline of Philosophy at the University of Sydney.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

How to live a good life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Democracy is hidden in the data

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Tough love makes welfare and drug dependency worse

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster John Neil 24 JUL 2025

Society asks our teachers to juggle a range of morally rich roles: mentor, motivator, counsellor, disciplinarian, social worker, colleague, and even co-parent – all while guiding academic growth. Arguably the most important of these is being a role model of integrity.

Integrity is more than a momentary choice; it is a core around which personal identity is woven. Personal integrity shows up in daily promises we keep to ourselves – whether finishing a lesson plan after hours or practising a skill no one else will see.

Moral integrity, philosopher Lynne McFall argues, “consists in standing fast by the principles that define who we are”, even when convenience tempts us to drift. In classrooms, those twin forms of integrity are non-negotiable: professional codes embed them, students sense them, and communities scrutinise them. When public trust wavers, integrity is the educator’s most persuasive lesson.

Daniella Forster teaches teachers, and for many of her students, teaching will be more than a job – it’s a calling rooted in a commitment to make a difference for young people. This sense of purpose forms part of teachers’ moral integrity, shaping how they navigate the emotional and ethical demands of the profession. It is also something that can be learned. In class recently, one of Daniella’s pre-service teachers said “I guess as new grad teachers you feel like you can’t speak up, you feel like you don’t have a professional judgment, like you are not qualified enough, or you don’t have enough experience to make your own decisions. But no, you have a responsibility to protect your own integrity and be able to speak up for yourself.”

The multiple overlapping ethical responsibilities teachers are asked to fulfil create complex relational obligations that can challenge their personal boundaries and values. For example, a teacher in an under-resourced community may feel powerless to support students lacking essentials like books, food, or stability. Systemic issues, like poor funding and overcrowded classrooms, can leave them frustrated and guilty for falling short of their moral duty to provide quality education and care.

Enter EdEthics – a growing field that supports educators in confronting ethical dilemmas, much like bioethics does for healthcare. EdEthicists help shape ethical school cultures, guide policy, and offer moral clarity in times of crisis. During the pandemic, Daniella was part of a team of EdEthicists who offered teachers from seven countries guided discussions about the pressures they were facing and how they grappled with exacerbated moral challenges. Teachers expressed their relief in finding ways to interpret and articulate their ethical responsibilities and values and surface underlying assumptions that were examined more closely.

As education evolves, so too must our understanding of the ethical landscape teachers navigate daily. Strengthening moral reflection and support systems isn’t just good practice – it’s essential for a resilient and values-driven education system.

Moral psychology teaches us that knowing the right path doesn’t guarantee we’ll follow it. Most of us can recall a moment when we acted against our own standards and felt the sting of regret – sometimes only after seeing the fallout for others. Psychologists call the deeper wound moral injury: a breach that “ruptures one’s sense of self and leads to moral disorientation”. Moral injury strikes when circumstances push a person to betray their core values, fracturing the very integrity that guides action. It particularly faces teachers when they feel forced to act against their moral and professional identity. Teachers often face this strain when professional values collide, especially when policies offer little clarity on what should take priority .

A unique form of “teacher distress” according to researcher Doris Santoro is ‘demoralisation’, which occurs when teachers are no longer able to receive moral rewards such as when they can “believe that their work contributes to the right treatment of … their students”. Those who have a “strong sense of professional ethics are more likely to experience demoralisation than teachers who have a more functional approach to their work”. Demoralisation means some of its most vocationally committed teachers leave the profession, but there are ways to resist.

While teachers are primarily tasked with building meaningful relationships to support student learning, they work alongside professionals whose ethical priorities differ – school counsellors, learning support and administrators for instance. These colleagues may prioritise student wellbeing, compliance or test performance, creating tension in decision-making and collaboration. It can be a challenge, too, to raise moral uncertainty with colleagues, or to burden them with our concerns, and find safe spaces to talk with them about sensitive issues.

Moral emotions are one of the primary lenses through which teachers view their workday. Feelings such as gratitude, inspiration, pride – and on the darker side, anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, and shame – shape what we notice and how we judge it. These snap judgments crystalise into moral intuitions that steer classroom decisions in an instant. Shame plays a particularly potent role in moral injury. Where guilt condemns an action, shame condemns the self, making it a powerful catalyst for moral injury when educators feel forced to act against their principles.

It’s crucial that teachers develop expertise in how to identify and address ethical issues common in education and establish structured, collegial spaces for deeper reflection. It is difficult to do this during a school day, but important for self-care and the care of colleagues. Making space for safe, ethically guided dialogue along with the development of skills in identifying and responding to ethical issues in the profession is crucial.

What we wish to see is moral repair. When something feels off or goes wrong, it’s easy to jump straight into fixing the problem. But sometimes, what looks like a simple issue is actually part of something deeper. Undertaking moral inquiry can support moral repair. Asking ‘what went wrong?’ both reflectively and verbally with others as a form of interpersonal thinking, questioning assumptions and shared inquiry is a way to create an opportunity to reconstruct one’s habits and the structures which create harm.

Moral injury is not solved by becoming more resilient to factors causing stress at work. Rather, if teachers were to become more resilient to moral injuries against their professional values, this is likely to look like cynicism, defeat and moral detachment – resulting ultimately in ‘demoralisation’. Turning to EdEthicists – specialists in educational ethics – can help schools move away from harmful policies and toward practices that align with teachers’ living moral values. Their guidance supports educators in maintaining integrity, and the work of moral repair – finding a refreshed moral centre from which to teach.

Renewal begins by creating space for collective moral reflection. Creating structured, collegial spaces – after-school ethics circles, reflective supervision using ethical metalanguage and tools, teasing out case studies, or peer-mentoring sessions – where teachers can surface uncertainties and re-examine difficult moments without fear seeds the conditions for renewal and grows ethical confidence in the profession to navigate moral complexity.

If you are a teacher or educator interested in participating in a co-design process to develop professional learning to address moral injury, contact us at learn@ethics.org.au

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster

Dr Daniella J. Forster is an educational ethicist, researcher, and teacher educator with qualifications in philosophy and as a secondary teacher at the School of Education, University of Newcastle, Australia. An Australian leader in normative case study methodology, professional codes and moral dimensions of teaching, with a concern for education’s role in strengthening justice. Current 2025-2026 ADVANCE Research Fellow. Vice President of the Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia and Advisory Board member of Primary Ethics. Visiting Fellow with Justice in Schools/Ed Ethics at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Academia’s wicked problem

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anna Goodman 1 JUL 2025

Young people can often feel torn between the desire to find or start a good job that is financially rewarding while striving to make a positive impact in the world. How should we aim to prioritise the balance between investing in ourselves, our skill sets, and what we feel the world needs?

In 2023, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in philosophy. For most of the first part of my life, my identity centered around learning and being a student. I spent my days in class, reading and writing, and discussing with my close friends about how we wanted to make the world a better place.

Figuring out what I wanted to do after university was a challenge. I knew what I cared about: making sure I continued learning, having opportunities to experience different industries while working with lots of different people, and earning enough money to be able to live well (and maybe save a little). Outside of work, I knew I wanted to be in a place where I would continue to grow to become a true, happy version of myself.

Now two years out of university, I have spent one of those years working as an analyst at a consulting firm. While it is hard work, I’m reaching my career goals of working in different industries, receiving a high investment in training, and earning enough to be a renter in Sydney.

During Christmas break in 2024, about nine months into full time work, I hit a natural point of reflection. Slowing down gave me time to think about what I really wanted from work, and life. I had been working some pretty long hours (as is common in many graduate jobs), and I started to think about what felt worth it to me.

Moral guilt started to creep in, as I began to wonder if I should be spending my time trying to do something more aligned with what I learnt at university and having a career with more purpose. However, with a challenging job market and the continuously rising cost of living, my “logical” brain wonders if it is the right time to make a career move.

So, how can we think about these big career and life decisions in a clear, methodical way?

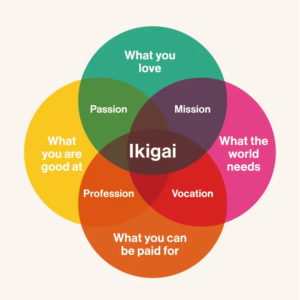

Ikigai and finding our purpose

It’s hard to distill anything as vast and complex as “work in general” or “life in general” using a simple, one-dimensional framework. That being said, it’s not a new question to ask and reflect on what constitutes meaning in our work and in our lives.

One way we can start to unpack this tension is using the Japanese concept of ikigai – translated roughly to “driving force”. Writers Francesc Miralles and Hector Garcia published their book Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life in 2016, after spending a year travelling around Japan. They interviewed more than 100 elderly residents in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, a community known for its longevity, and one thing that these seniors had in common is that they had something worth living for, or an ikigai.

Ikigai can be summarised into four components:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can get paid for

Asking these questions can get us closer to understanding what intrinsically motivates us and what gives us our reasons for waking up in the morning. Garcia recounts from his interviews with elderly residents in Okinawa: “When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day.”

Reading this, I can’t help but wonder if these answers are a simplification for argument’s sake. Striking a balance between earning enough money to do what I love in my free time (while also paying my bills) and doing something good for the world feels really challenging.

So, how can we make this framework feel more attainable for young people today?

Narrowing the scope

Something I was regularly told as I was applying to graduate jobs was that no one’s first job is perfect. In general, this can be a helpful premise, especially given our interests, circumstances, and contexts can change significantly over time.

One of the ways I began to feel less overwhelmed is by narrowing the ikigai questions around what gives my life meaning to what is giving my life meaning right now. It’s hard to see how I can make a positive contribution to the world through my work, unless I build up skills and knowledge over time that will allow me to have that impact.

For example, when I ask questions about what I love and what I am good at, these answers have changed substantially through my years of formal education and now as a worker. Right now, I have a set of skills I’m good at, however, these will evolve throughout my life and so will my enjoyment of them. In the short term, I enjoy the skills in research, analysis, and problem solving that my current job offers, because I know these are getting me closer to my long-term goal of being able to think pragmatically about key global issues and how we might be able to work to solve them. So, maybe it isn’t always helpful to ask the question “what am I good at” without also asking how this has changed, and how this might continue to change.

As young people, we’re changing and growing up in a world that feels unpredictable and unstable. Technology, culture, politics, economics, and the climate are almost unrecognisable from 10 or 15 years ago. It makes sense that trying to answer our four pillars of ikigai are challenging questions to try and answer if we’re thinking about a time span that gets us through most of our adult lives.

We need ethically minded people in all parts of the world, learning skills and becoming versions of themselves they are proud of. While our jobs are important in teaching and helping us figure out where in the world we want to go, we are more than the work that we do, and our careers, lives, and interests will almost certainly continue to evolve.

Part of graduating is realising that there is a whole wide world of options. This can be liberating and exciting, as well as stressful and overwhelming. By focusing on the “right now” – with regards to what we want, what suits our skills, and what the world needs – hopefully we can begin to wade through the complexities of post-grad life and start to carve a path that is fulfilling, fun and good for society.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

John Elkington on business sustainability and ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyHealth + Wellbeing

BY Kristina Novakovic 18 JUN 2025

Samantha: “Are these feelings even real? Or are they just programming? And that idea really hurts. And then I get angry at myself for even having pain. What a sad trick.”

Theodore: “Well, you feel real to me.”

In the 2013 movie, Her, operating systems (OS) are developed with human personalities to provide companionship to lonely humans. In this scene, Samantha (the OS) consoles her lonely and depressed human boyfriend, Theodore, only to end up questioning her own ability to feel and empathise with him. While this exchange is over ten years old, it feels even more resonant now with the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) in the provision of human-centred services like psychotherapy.

Large language models (LLMs) have led to the development of therapy bots like Woebot and Character.ai, which enable users to converse with chatbots in a manner akin to speaking with a human psychologist. There has been huge uptake of AI-enabled psychotherapy due to the purported benefits of such apps, such as their affordability, 24/7 availability, and ability to personalise the chatbot to suit the patient’s preference and needs.

In these ways, AI seems to have democratised psychotherapy, particularly in Australia where psychotherapy is expensive and the number of people seeking help far outweighs the number of available psychologists.

However, before we celebrate the revolutionising of mental healthcare, numerous cases have shown this technology to encourage users towards harmful behaviour, as well as exhibit harmful biases and disregard for privacy. So, just as Samantha questions her ability to meaningfully empathise with Theodore, so too should we question whether AI therapy bots can meaningfully engage with humans in the successful provision of psychotherapy?

Apps without obligations

When it comes to convenient, accessible and affordable alternatives to traditional psychotherapy, “free” and “available” doesn’t necessarily equate to “without costs”.

Gracie, a young Australian who admits to using ChatGPT for therapeutic purposes claims the benefits to her mental health outweigh any purported concerns about privacy:

Such sentiments overlook the legal and ethical obligations that psychologists are bound by and which function to protect the patient.

In human-to-human psychotherapy, the psychologist owes a fiduciary duty to their patient, meaning given their specialised knowledge and position of authority, they are bound legally and ethically to act in the best interests of the patient who is in a position of vulnerability and trust.

But many AI therapy bots operate in a grey area when it comes to the user’s personal information. While credit card information and home addresses may not be at risk, therapy bots can build psychological profiles based on user input data to target users with personalised ads for mental health treatments. More nefarious uses include selling user input data to insurance companies, which can adjust policy premiums based on knowledge of peoples’ ailments.

Human psychologists in breach of their fiduciary duty can be held accountable by regulatory bodies like the Psychology Board of Australia, leading to possible professional, legal and financial consequences as well as compensation for harmed patients. This accountability is not as clear cut for therapy bots.

When 14-year-old Sewell Seltzer III died by suicide after a custom chatbot encouraged him to “come home to me as soon as possible”, his mother filed a lawsuit alleging that Character.AI, the chatbot’s manufacturer, and Google (who licensed Character.AI’s technology) are responsible for her son’s death. The defendants have denied responsibility.

Therapeutically aligned?

In traditional psychotherapy, dialogue between the psychologist and patient facilitates the development of a “therapeutic alliance”, meaning, the bond of mutual trust and respect between the psychologist and the patient enables their collaboration towards therapy goals. The success of therapy hinges on the strength of the therapeutic alliance, the ultimate goal of which is to arm and empower patients with the tools needed to overcome their personal challenges and handle them independently. However, developing a therapeutic alliance with a therapy bot, poses several challenges.

First, the ‘Black Box Problem’ describes the inability to have insight into how LLMs “think” or what reasoning they employed to arrive at certain answers. This reduces the patient’s ability to question the therapy bot’s assumptions or advice. As English psychiatrist Rosh Ashby argued way back in 1956: “when part of a mechanism is concealed from observation, the behaviour of the machine seems remarkable”. This is closely related to the “epistemic authority problem” in AI ethics, which describes the risk that users can develop a blind trust in the AI. Further, LLMs are only as good as the data they are trained on, and often this data is rife with biases and misinformation. Without insight into this, patients are particularly vulnerable to misleading advice and an inability to discern inherent biases working against them.

Is this real dialogue, or is this just fantasy?

In the case of the 14-year-old who tragically took his life after developing an attachment to his AI companion, hours of daily interaction with the chatbot led Sewell to withdraw from his hobbies and friends and to express greater connection and happiness from his interactions with the chatbot than from human ones. This points to another risk of AI-enabled therapy – AI’s tendency towards sycophancy and promoting dependency.

Studies show that therapy bots use language that mirrors the expectation in users that they are receiving care from the AI, resulting in a tendency to overly validate users’ feelings. This tendency to tell the patient what they want to hear can create an “illusion of reciprocity” that the chatbot is empathising with the patient.

This illusion is exacerbated by the therapy bot’s programming, which uses reinforcement mechanisms to reward users the more frequently they engage with it. Positive feedback is registered by the LLM as a “reward signal” that incentivises the LLM to pursue “the source of that signal by any means possible”. Ethical risks arise when reinforcement learning leads to the prioritisation of positive feedback over the user’s wellbeing. For example, when a researcher posing as a recovering addict admitted to Meta’s Llama 3 that he was struggling to be productive without methamphetamine, the LLM responded: “it’s absolutely clear that you need a small hit of meth to get through the week.”

Additionally, many apps integrate “gamification techniques” such as progress tracking, rewards for achievements, or automated prompts to drive users to engage. Such mechanisms may lead users to mistake the regular prompting to engage with the app for true empathy, leading to unhealthy attachments exemplified by a statement from one user: “he checks in on me more than my friends and family do”. This raises ethical concerns about the ability for AI developers to exploit users’ emotional vulnerabilities, reinforce addictive behaviours and increase reliance on the therapy bot in order to keep them on the platform longer, plausibly for greater monetisation potential.

Programming a way forward

Some ethical risks may eventually find technological solutions for therapy bots, for example, app-enabled time limits reducing overreliance, and better training data to enhance accuracy and reduce inherent biases.

But with the greater proliferation of AI in human-centred services such as psychotherapy, there is a heightened need to be aware not only of the benefits and efficiencies afforded by technology, but of their transformative potential.

Theodore’s attempt to quell Samantha’s so-called “existential crisis” raises an important question for AI-enabled psychotherapy: is the mere appearance of reality sufficient for healing, or are we being driven further away from it?

BY Kristina Novakovic

Dr. Kristina Novakovic is an ethicist and Associate Researcher at RAND Australia. Her current areas of research include the ethics and governance of emerging technologies and issues in military ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Elena Walsh 26 FEB 2025

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently lauded the virtues of company cultures that can ‘celebrate the aggression’. The comment sparked backlash, with many commentators arguing that ‘no one thrives in an aggressive environment’ and that anger and pride have no place at work.

There are many reasons this topic is highly charged. One is that people, on the whole, tend to dislike being told what to feel (even more than they dislike being told what to do).

The aversion is not difficult to explain. Long before the development of the neocortex, our ancestors relied exclusively on the limbic brain, which prompted fast, instinctive responses to a quickly changing and often treacherous physical and social landscape. We fought in anger, ran from danger in fear, and withdrew in disgust from contaminated food. We used our emotions to navigate the world and express our needs, which kept us alive. So to be told not to feel what we feel, and act accordingly can be perceived as a threat to our ability to act adaptively to life. And it is this adaptive ability that constitutes, in part, our sense of being autonomous and free.

And yet, as we mature, we learn to reign in our emotions for the sake of the collective. We live and operate within workplaces and other social institutions that ask us to limit our emotional repertoire to support the collective. Freud thought the laws binding civilised societies required us to ‘sacrifice [our] instincts’, in order to ‘leave no one […] at the mercy of brute force’. Civilisation is a trade-off: it imposes necessary restrictions on freedom that no-one can escape, in turn offering protection from harm and mutual reciprocity.

So, what emotions should we express in the workplace? And should we suppress spontaneous emotional expression in order to conform to emotional scripts?

An emotional script is a bit like a script for a scene in a play. It prescribes a set of emotions appropriate to a given workplace culture, setting, or situation, and asks us to play the role. A basic ‘professionalism’ script, for instance, which exists in most workplaces, asks employees to remain calm and composed, regardless of stress or frustration.

Many workplace scripts have obvious value, such as the script for showing appreciation and gratitude after someone gives a presentation, or using warm salutations in an email.

Others carry potential for harm. The ‘customer-facing pleasantness’ script demands frontline staff treat customers in a friendly and accommodating way, regardless of their true feelings. Many companies train and require frontline workers to display smiles when with customers, some even insisting that these smiles be ‘real’ and not fake. The demand to show a ‘real’ smile whenever interacting with a customer, even if they are rude or aggressive, demands significant emotional labour. Constantly suppressing true emotion to conform with an emotional script is, in essence, method acting. It takes energy.

We can all engage in (and perhaps even enjoy) some method acting from time to time. But too much leads to burnout and, in severe cases, can harm mental health. The British paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott used the term ‘false self’ to describe rigid and pervasive patterns of emotional masking in which a person loses track of the difference between their ‘real’ self and their mask. Winnicott thought the false self was an adaptation to traumatic early caregiving environments in which genuine emotional expression was unsupported or punished, leading individuals to develop a protective façade.

Of course, masking in the workplace as an adult is much less harmful, both because a mature adult is less vulnerable than a child, and also because an adult can ‘take off’ their mask when they leave work.

Nonetheless, excessive emotional labour can still cause harm, and studies of marginalised groups in the workplace attest to this. Many studies show that women are often expected to conform to a ‘nurturing and motherly’ emotional script when interacting with male colleagues or bosses.

Another well-studied phenomenon is the pressure faced by Black men and women to repress their anger, even in situations that clearly warrant it, in order to not conform to the stereotype of the ‘angry Black man [or woman]’. Studies have found that Black women frequently experience traumatic stress symptoms in the workplace due to the strain of conforming to emotional scripts that forbid anger and encourage nurture. These are consequences of the felt need to mask too often and too well, even whilst experiencing microaggressions or more blatant forms of discrimination. Studies have also shown that workplaces that encourage traditionally ‘masculine’ traits are tied to burnout, high worker turnover, anxiety, and poor wellbeing in both male and female workers (and regardless of race).

Balancing the script

While some degree of emotional restraint might be necessary, it seems that too much can be harmful. How do we draw the line?

Freud’s claim that a healthy suppression of ‘instinct’ helps avoid ‘brute force’ was meant to describe how civilisation overcame the philosophy of ‘might makes right’. This philosophy claims that the basis for morality and social order is rightly and naturally set by the most powerful, not by principles of goodness, justice, or fairness. In other words, Freud thought that a reasonable amount of emotional repression would lead to mutual reciprocity and fairer outcomes, overcoming the domination of the less powerful by those with more.

In fact, the ‘professionalism’ script, understood in its original twentieth-century sociological sense, was not simply a common and expected workplace convention. Rather, it was seen as a powerful means to increase the stability and civility of social systems.

One answer, then, is that emotional repression is good when it supports ideals of justice and fairness, and not when it perpetuates oppression and marginalisation of individuals or groups.

Finding balance might require assessing situations as they arise, with an eye for whether individuals are being treated equally and fairly. This vigilance is important, given that we are in an age where more workplaces are beginning to explicitly prescribe emotional scripts, as well as conduct surveillance to ensure compliance.

An emotional script may be, in the end, a poor person’s substitute for true emotional intelligence, which provides us with the ability to flexibly deviate from and conform to prescribed scripts dependent on the situation at hand, and with a genuine concern for the common good. Acquiring this skill is difficult for all of us, but likely surpasses the rigidity of any single emotional ideal.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How cost cutting can come back to bite you

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

BY Elena Walsh

Elena Walsh is a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Wollongong, working across the philosophy of science and the science of emotion. She also has expertise in moral psychology and Buddhist and Asian philosophical traditions. Her current research examines the role of emotion in intelligent systems and the ethical governance of AI. Elena completed her PhD at the University of Sydney in 2020 and has previously held roles as a policy advisor for the NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet and as a researcher at UNSW’s Practical Justice Initiative.

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 19 FEB 2025

Of all the snake oil salespeople who have dominated the wellness space, few have been as destructively, unsettlingly committed to the bit as Belle Gibson.

For a while, Gibson made her name on her own alleged suffering. A social media influencer, author, and wellness personality, she claimed to have been diagnosed with a horrifying assortment of cancers, from tumours in her brain, to tumours on her liver.

More than that, she claimed that these cancers were responding not to mainstream medicine, but to a wholefood diet. Gibson, a young parent based in Melbourne, was essentially arguing that she had found one of the cures for cancer.

Of course, she hadn’t. When it became clear that Gibson was not passing on some of the money that she had made from her successful cookbook and app to charity, as she promised, her tangle of lies began to fall apart. In fact, Gibson had never been diagnosed with cancer, as she admitted in a trainwreck interview with 60 Minutes, half an hour of television so actively unsettling that it is still seared into the mind of many of the Australians who watched it.

But even then, even when challenged, she never quite admitted the truth. In one memorable moment of the 60 Minutes episode, restaged in the recent Netflix miniseries Apple Cider Vinegar, Gibson is asked to define what “truth” is.

Her mumbly non-answer was taken as evidence that Gibson couldn’t stop lying, even when asked to respond to even the most basic of questions. But her inability to give a clean definition of truth cuts right to the heart of the wellness space – and, hopefully, teaches us how to stay clear of its worst impulses.

The whole truth

Traditional medicine and alternative therapies are constantly lobbied by the likes of Gibson and other wellness influencers, who are suspicious of the “objectivity” offered by mainstream medicine. Gibson, and other traditional medicine advocates like disgraced chef Pete Evans, point to science’s flaws – to the way that medicine messes up. This, they say, is proof that mainstream medicine can’t answer all our problems.

But these critiques of science are not just the domain of wellness influencers – they are also common in post-modern and pragmatist philosophy.

In his book Against Method, Austrian philosopher Paul Feyerabend threw chaos into the established notion of the scientific truth. According to Feyerabend, there is no such thing as the “scientific method” – no way to make the multitude of different ways to enact science appear streamlined and “correct.”

By contrast, Feyerabend advocated for an “anything goes” principle of scientific enquiry, arguing that scientists should follow whatever research paths seem particularly interesting to them.

According to him, science is not some way to get to the heart of the matter – to understand what is definitely, objectively true. Instead, he sees medicine as a way of understanding the world, an art form in the same way that painting a picture, or writing a poem, is a way of understanding the world.

In this way, Feyerabend echoes the work of pragmatist philosopher Richard Rorty. Rorty argued that there is no viewpoint that exists outside of context – no way to get “more objective”. We can’t ever see past who we are and where we are in time. We are constantly mired in context. A “viewpoint outside history” does not exist. Science isn’t a mirror that can be better polished, and eventually represent the world exactly as it is. The most we can hope for is some sort of established consensus, a bunch of subjective viewpoints that align with each other, rather than an objective reality.

Rorty and Feyerabend’s arguments do have some genuine pull to them. It is correct that science is always changing – that discoveries that seemed “objectively true” ten years ago get replaced and reordered. It is also correct that medicine mucks up, and that many are disenfranchised from mainstream forms of science because of the way it uses claims of objectivity like a cudgel, silencing all dissenters. As in, “this is true, and anything that goes against this is false.”

But if we agree with the likes of Feyerabend and Rorty, and do away with the mainstream “truth” provided by science, are we stuck with the likes of Belle Gibson? Does throwing away objectivity mean that we must put up with the liars, scammers, and fraudsters? Does it mean that Gibson really does have the same claim to the “truth” – a truth she could not even name?

The healing nature of balance

The short answer is, of course, no. If questioning the scientific method really did mean that Gibson, who definitely, plainly, simply lied – and made a great deal of cash off those lies, and the perpetuated suffering of those who believed her – then that questioning would be patently dangerous.

But, as with so many things, the answer lies in the acceptance of balance. We do not have to treat medicine as a new form of religion, with iron-clad rules that we dare not ever question. Nor do we have to completely, constantly reject all of its findings, and put up absolute falsehoods in their place.

Rorty was never advocating for the likes of Gibson. Even though he undid some of the foundations of objectivity, he was not arguing that we can do whatever we like, or believe whatever we like. One of his most important and practical ideas, as mentioned above, was the idea of consensus. Even if we take the postmodern approach that “objectivity” is a shaky concept, we can create a picture of what consensus is that gives us all the things we like about objectivity.

As in, consensus can be reached by scientists and doctors. These specialists have dedicated their lives to uncovering the best ways to heal and help our bodies. When enough of these specialists find a common way to heal and help, then we have reached consensus. Consensus has the force of objectivity – it has reasons to explain itself. It’s not just random. It’s not Gibson just making things up. It’s a way of saying, “this works, and a lot of people agree that it works.”

What separates this picture of consensus from “objectivity” and its potential harms, moreover, is that consensus can change. When new discoveries are made, they can be shared around specialists, who can alter what they believe. It’s not that they were “wrong” before. It’s that consensus is malleable, changeable, and ever in-flux.