Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 19 FEB 2020

The Ethics Centre is a strong supporter of human rights. As such, we agree with the principal purpose of the draft Religious Discrimination Bill (2019) legislation – which is to outlaw discrimination against all persons on the basis of their religion. However, we also argue that the exposure draft is deficient in a number of important ways.

We recently made a submission articulating these concerns in response to the second exposure draft of the proposed legislation.

Core to the submission is our belief that human rights form a whole and are indivisible. That is, we are disinclined to support legislation that creates broad, general exceptions to the principle of non-discrimination. This is especially so when the proposed exceptions risk abrogating the human rights of one group in favour of another.

It’s important to make it clear that the Centre’s approach is not based on a naïve belief that human rights cohere without tension. We know that this is not the case – and understand that religion is, by its very nature, a special case.

This flows from the fact that every religion makes rival, exclusive and absolute truth claims that resist any form of independent evaluation.

Add to this religion’s appeal to transcendent authority, its inclination to order the lives of its adherents and the emotional and spiritual investment it requires of individual and communal belief – and it’s not surprising that difficulties arise not only between religions but in connection with the expression of other human rights.

Our submission seeks to affirm the universal principle of ‘respect for persons’ and to propose criteria for limiting (without totally restricting) the extent to which religious belief can be used as a justification for discrimination.

‘Respect for persons’ is the ethical requirement that we each recognise the intrinsic dignity of every other person – irrespective of their, gender, sex, race, religion, age … or any other non-relevant discriminator. It is this principle that underpins all human rights – and cannot be set aside without undermining the whole edifice.

Given this, we argue that any exception to the prohibition of discrimination that is accorded to people of faith must be severely restricted. That is, lawful discrimination, by people of faith, must only be allowed to the extent strictly necessary to avoid material harm to the religious sensibilities of those affected.

In short: we set a very high bar for those seeking to discriminate against others in the name of religion.

For example, there is a good case for allowing a religious school to discriminate against a person seeking employment as its Principal while concurrently rejecting the religious beliefs that inform the school’s defining ethos.

However, there is no good reason for applying such a test to the employment of a member of the same school’s maintenance team. Nor is there any justification for discriminating against a person based, say, on their sexual orientation if, in all other respects, the person aligns with the religious beliefs of the school – as understood by a significant number of believers.

This brings us to another aspect of the Centre’s submission – that discrimination based on religion only be allowed where there is broad consensus, amongst the faithful, that a belief is a legitimate expression of their religion. This should help avoid giving protection to those who occupy the extreme fringes of religious belief.

Finally, none of the above should be read as justifying restrictions on religious belief. On the contrary, we support the right of people to believe whatever they like. Furthermore, we encourage people to act in accordance with a well-informed (and well-formed) conscience.

We also urge people to realise that to act in good conscience entails the possibility of being punished if your conduct is found to be contrary to law. Such is the case of conscientious objectors who resist conscription into the armed forces, or Roman Catholic priests who choose to respect the ‘seal of the confessional’ even if the law compels them to disclose specified admissions by penitents.

This is the balance that a society needs to maintain: respecting the moral courage of those whose religious beliefs compel them to act in a manner that society must prohibit for the sake of all.

For those who are interested, The Ethics Centre’s submission on the proposed legislation will be published by the Commonwealth Attorney General’s Department in due course.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and tyrannicide: Can political violence ever be justified?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

McKenzie... a fractured cog in a broken wheel

McKenzie… a fractured cog in a broken wheel

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

In many cases, the response to scandal is often as instructive as an assessment of its cause. So it has proved to be in the case of the issues that led to the resignation of Senator Bridget McKenzie as a Federal Government Minister.

The findings of the Auditor General unleashed a fair amount of anger and disgust – especially amongst community groups who were deemed to be meritorious recipients of funding but who missed out due to political considerations.

While I understand the outrage, strong emotions can make us blind to areas of ethical importance. As citizens, we need to notice the rapid normalisation of deviance that is eroding the foundations of our representative democracy.

In this, we should look to the insights of Edmund Burke who recognised the role played by traditions and conventions in maintaining the integrity of institutions and societies.

Those who know my writings might be surprised to find me ‘channelling’ Burke. For three decades, I have warned of the perils of unthinking custom and practice. But note that my target has always been practices and arrangements that are unthinking. I am a great admirer of customs and practices that derive their life from a conscious application of purpose, values and principles.

Too often, it is the dead hand of tradition that leads institutions to betray their underlying purposes, lose legitimacy and invite revolution. In that sense, I think that Edmund Burke and I would be in perfect accord.

I also think that Burke would be deeply concerned by the radical turn away from convention taken by the government of Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, in response to the ANAO’s ‘Sports Rort’ Report.

The government’s response has been marked by a persistent refusal to acknowledge and uphold, in practice, a couple of fundamental principles. First, that public power and monies (levied by taxes) should be used exclusively for public purposes. Second, that Ministers are responsible for all that is done in their name.

Instead, the government and its representatives have sought to distract the public by laying some false trails. They have claimed that ‘no rules were broken’. They have argued that the ‘ends justified the means’. They have suggested that the Minister should be excused from responsibility for the activities of her advisers (and possibly advisers in the offices of other ministers) who shaped decisions according to the political interests of the Coalition parties.

The fact that Senator McKenzie resigned over a ‘technical breach’ of the Ministerial Code – without any sense of remorse or censure for the way she exercised discretion in the allocation of public funds – has reinforced the public’s perception that politics and ethics have become estranged.

Just the other day someone said to me, “I can’t believe you expected anything different …”. The person then paused, in mid-sentence, and said, “Did I really just say that …? What has happened to us?”. Indeed, how have we come to accept such low standards as ‘normal’? When will we realise that we are being robbed of our reasonable expectations as citizens in a democracy?

Our government’s behaviour may deserve moral censure. However, we should not let this obscure the fact that its response to the ‘Sports Rort’ reveals a woeful lack of commitment to the preconditions for a functioning representative democracy. It is this, more than anything else, that should really worry us.

“Our government’s behaviour may deserve moral censure. However, we should not let this obscure the fact that its response to the ‘Sports Rort’ reveals a woeful lack of commitment to the preconditions for a functioning representative democracy.”

One result of a lack of clear commitment to ethics within government has been the growing demand for a Federal Integrity Commission. The idea is popular with the general public – who are sick of being held accountable for their conduct while watching the most powerful people in the nation letting each other off the hook. Given this, the major political parties are committed to the creation of this new, independent oversight body.

Personally, I think it incredibly sad that it has come to this. That multiple generations of politicians, from across the political spectrum, have made this necessary is an indictment of their stewardship of our democratic institutions.

However, if it is to be done, then it must be done well. There is no point in the Parliament putting in place a ‘paper tiger’ limited to reviewing the most extreme cases of ethical failure by the smallest possible subset of public officials. It is for that reason, I support the Beechworth Principles which were launched this week.

We deserve governments that earn our trust and preserve their legitimacy. Is that really too much to ask of our politicians?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Danielle Harvey The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

When we settled on Town Hall as the venue for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) 2020, my first instinct was to consider a choir. The venue lends itself to this so perfectly and the image of a choir – a group of unified voices – struck me as an excellent symbol for the activism that is defining our times.

I attended Spinifex Gum in Melbourne last year, and instantly knew that this was the choral work for the festival this year. The music and voices were incredibly beautiful but what struck me most was the authenticity of the young women in Marliya Choir. The song cycle created by Felix Riebel and Lyn Gardner for Marliya Choir embarks on a truly emotional journey through anger, sadness, indignation and hope.

A microcosm of a much larger phenomenon, Marliya’s work shows us that within these groups of unified voices the power of youth is palpable.

Every city, suburb and school has their own Greta Thurnbergs: young people acutely aware of the dangerous reality we are now living in, who are facing the future knowing that without immediate and significant change their future selves will risk incredible hardship.

In 2012, FODI presented a session with Shiv Malik and Ed Howker on the coming inter-generational war, and it seems this war has well and truly begun. While a few years ago the provocations were mostly around economic power, the stakes have quickly risen. Now power, the environment, quality of life, and the future of the planet are all firmly on the table. This has escalated faster than our speakers in 2012 were predicting.

For a decade now the FODI stage has been a place for discussing uncomfortable truths. And it doesn’t get more uncomfortable than thinking about the future world and systems the young will inherit.

What value do we place on a world we won’t be participating in?

Our speakers alongside Marliya Choir will be tackling big issues from their perspective: mental health, gender, climate change, indigenous incarceration, and governance.

First Nation Youth Activist Dujuan Hoosan, School Strike for Climate’s Daisy Jeffery, TEDx speaker Audrey Mason-Hyde , mental health advocate Seethal Bency and journalist Dylan Storer add their voices to this choir of young Australians asking us to pay attention.

Aged from 12 to 21, their courage in stepping up to speak in such a large forum is to be commended and supported.

With a further FODI twist, you get to choose how much you wish to pay for this session. You choose how important you think it is to listen to our youth. What value do you put on the opinions of the young compared to our established pundits?

Unforgivable is a new commission, combining the music from the incredible Spinifex Gum show I saw, with new songs from the choir and some of the boldest young Australian leaders, all coming together to share their hopes and fears about the future.

It is an invitation to come and to listen. To consider if you share the same vision of the future these young leaders see. Unforgivable is an opportunity to see just what’s at stake in the war that is raging between young and old.

These are not tomorrow’s leaders, these young people are trying to lead now.

Tickets to Unforgivable, at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Saturday 4 April are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Society + Culture

Stan Grant: racism and the Australian dream

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

BY Danielle Harvey

Danielle Harvey is Festival Director of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. A curator, creative producer and director, Harvey works across live performance, talks, installation, and digital spaces, creating layered programs that connect deeply with audiences.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data and Development

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

An examination of the profound loss of trust in liberal democratic institutions and the rise of populism.

Until quite recently, the liberal democracies of the West seemed to have it all. Led by the United States, they had defeated the Soviet Union to win the Cold War.

They had created an unprecedented level of prosperity. They had projected their culture – with its underlying values and principles – into every corner of the world.

Yet, in almost no time at all, the threads have been unravelling. Major institutions have lost the trust of the people. Ideological divisions have deepened and potentially destructive forms of populism have been unleashed.

Today, the global, rules-based order is looking shaky and we seem doomed to return to a world where nations act alone and ‘might is right’. How did this happen? What went wrong?

This essay traces how Enlightenment ideals shaped the hopes and expectations of citizens – only to be betrayed by leaders who forgot the defining purposes of the institutions they lead.

"A political system based on the intrinsic dignity of citizens has been replaced with one defined by a series of transactions, in which the government has become a 'providore' hawking its goods to customers whose currency is a vote."

DR SIMON LONGSTAFF

WHAT'S INSIDE?

History of the enlightenment

Current and future states

Recovering intrinsic dignity

The ethics of building anew

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

This is what comes after climate grief

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Ketan Joshi The Ethics Centre 21 JAN 2020

I can’t really lie about this. Like so many other people in the climate community hailing from Australia, I expected the impacts of climate change to come later. I didn’t define ‘later’ as much other than ‘not now, not next year, but some time after that’.

Instead, I watched in horror as Australia burst into flames. As the worst of the fire season passes, a simple question has come to the fore. What made these bushfires so bad?

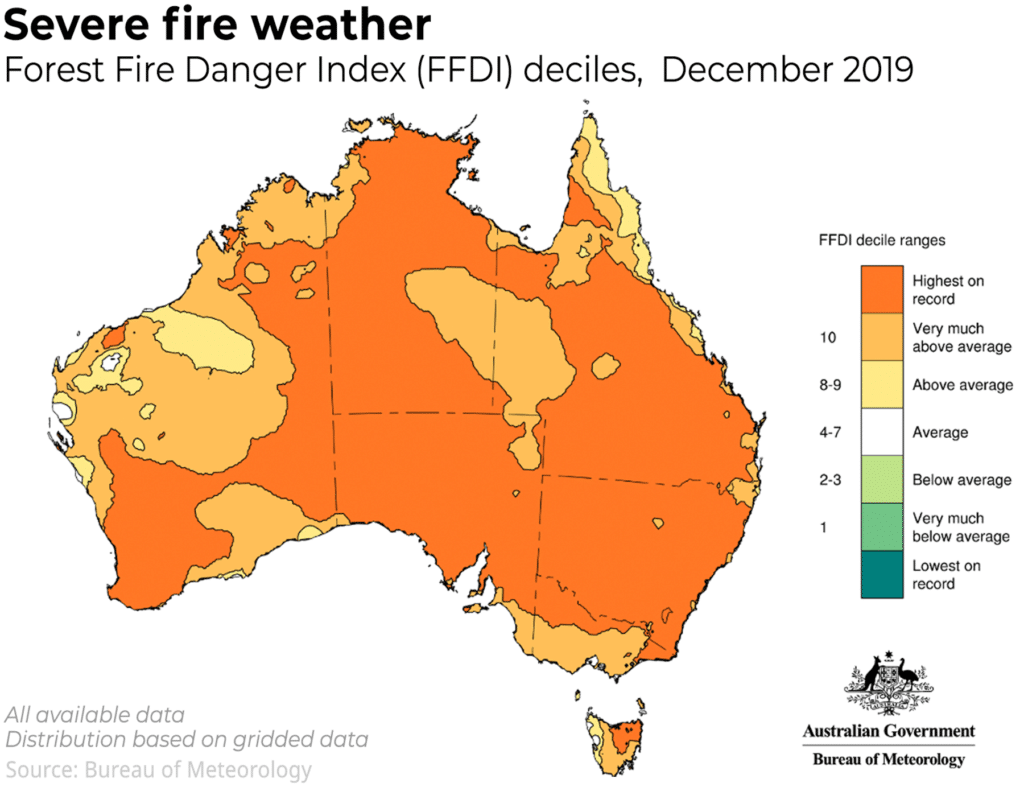

The Bureau of Meteorology confirms that weather conditions have been tilting in favour of worsening fire for many decades. The ‘Forest Fire Danger Index’, a metric for this, hit records in many parts of Australia, this summer.

The Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub is unequivocal: “Human-caused climate change has resulted in more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires in recent decades for many regions of Australia…These trends are very likely to increase into the future”.

Bushfire has been around for centuries, but the burning of fossil fuels by humans has catalysed and worsened it.

Having moved away from Australia, I didn’t experience the physical impacts of the crisis. Not the air thick with smoke, or the dark brown sky or the bone-dry ground.

But I am permanently plugged into the internet, and the feelings expressed there fed into my feed every day. There was shock at the scale and at the science fictionness of it all. Fire plumes that create their own lightning? It can’t be real.

The world grieved at the loss of human life, the loss of beautiful animals and ecosystems, and the permanent damage to homes and businesses.

Rapidly, that grief pivoted into action. The fundraisers were numerous and effective. Comedian Celeste Barber, who set out to raise an impressive $30,000 AUD, ended up at around $51 million. Erin Riley’s ‘Find a Bed’ program worked tirelessly to help displaced Australians find somewhere to sleep. Australians put their heads down and got to work.

It’s inspiring to be a part of. But that work doesn’t stop with funding. Early estimates on the emissions produced by the fires are deeply unsettling. “Our preliminary estimates show that by now, CO2 emissions from this fire season are as high or higher than the CO2 emissions from all anthropogenic emissions in Australia. So effectively, they are at least doubling this year’s carbon footprint of Australia”, research scientist Pep Canadell told Future Earth.

There is some uncertainty about whether the forests destroyed by the blaze will grow back and suck that released carbon back into the Earth. But it is likely that as fire seasons get worse, the balance of the natural flow of carbon between the ground and the sky will begin to tip in a bad direction.

Like smoke plumes that create their own ‘dry lightning’ that ignite new fires, there is a deep cyclical horror to the emissions of bushfire.

It taps into a horror that is broader and deeper than the immediate threat; something lingers once the last flames flicker out. We begin to feel that the planet’s physical systems are unresponsive. We start to worry that if we stopped emissions, these ‘positive feedbacks’ (a classic scientific misnomer) mean we’re doomed regardless of our actions.

“An epidemic of giving up scares me far more than the predictions of climate scientists”, I told an international news journalist, as we sat in a coffee shop in Oslo. It was pouring rain, and it was warm enough for a single layer and a raincoat – incredibly strange for the city in January.

She seemed surprised. “That scares you?” she asked, bemused. Yes. If we give up, emissions become higher than they would be otherwise, and so we are more exposed to the uncertainties and risks of a planet that starts to warm itself. That is paralysing, to me.

It is scarier than the climate change denial of the 2010s, because it has far greater mass appeal. It’s just as pseudoscientific as denialism. “Climate change isn’t a cliff we fall off, but a slope we slide down”, wrote climate scientist Kate Marvel, in late 2018.

In response to Jonathan Franzen’s awful 2019 essay in which he urges us to give up, Marvel explained why ‘positive feedbacks’ are more reason to work hard to reduce emissions, not less. “It is precisely the fact that we understand the potential driver of doom that changes it from a foregone conclusion to a choice”.

A choice. Just as the immediate horrors of the fires translated into copious and unstoppable fundraising, the longer-term implications of this global shift in our habitat could precipitate aggressive, passionate action to place even more pressure on the small collection of companies and governments that are contributing to our increasing danger.

There are so many uncertainties inherent in the way the planet will respond to a warming atmosphere. I know, with absolute certainty, that if we succumb to paralysis and give up on change, then our exposure to these risks will increase greatly.

We can translate the horror of those dark red months into a massive effort to change the future. Our worst fears will only be realised if we persist with the intensely awful idea that things are so bad that we ought to give up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

BY Ketan Joshi

Was a speaker at IQ2: It's too soon to ditch fossil fuels. He is a science communicator with over eight years experience across The Monthly, Gizmodo, Cosmos and with the CSIRO.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A burning question about the bushfires

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

At the height of the calamity that has been the current bushfire season, people demanded to know why large parts of our country were being ravaged by fires of a scale and intensity seldom seen.

In answer, blame has been sheeted home to the mounting effects of climate change, to failures in land management, to our burgeoning population, to the location of our houses, to the pernicious deeds of arsonists…

However, one thing has not made the list, ethical failure.

I suspect that few people have recognised the fires as examples of ethical failure. Yet, that is what they are. The flames were fuelled not just by high temperatures, too little rain and an overabundance of tinder-dry scrub. They were also the product of unthinking custom and practice and the mutation of core values and principles into their ‘shadow forms’.

Bushfires are natural phenomena. However, their scale and frequency are shaped by human decisions. We know this to be true through the evidence of how Indigenous Australians make different decisions – and in doing so – produce different effects.

Our First Nations people know how to control fire and through its careful application help the country to thrive. They have demonstrated (if only we had paid attention) that there was nothing inevitable about the destruction unleashed over the course of this summer. It was always open to us to make different choices which, in turn, would have led to different outcomes.

This is where ethics comes in. It is the branch of philosophy that deals with the character and quality of our decisions; decisions that shape the world. Indeed, constrained only by the laws of nature, the most powerful force on this planet is human choice. It is the task of ethics to help people make better choices by challenging norms that tend to be accepted without question.

This process asks people to go back to basics – to assess the facts of the matter, to challenge assumptions, to make conscious decisions that are informed by core values and principles. Above all, ethics requires people to accept responsibility for their decisions and all that follows.

This catastrophe was not inevitable. It is a product of our choices.

For example, governments of all persuasions are happy to tell us that they have no greater obligation than to keep us safe. It is inconceivable that our politicians would ignore intelligence suggesting that a terrorist attack might be imminent. They would not wait until there was unanimity in the room. Instead, our governments would accept the consensus view of those presenting the intelligence and take preventative action.

So, why have our political leaders ignored the warnings of fire chiefs, defence analysts and climate scientists? Why have they exposed the community to avoidable risks of bushfires? Why have they played Russian Roulette with our future?

It can only be that some part of society’s ‘ethical infrastructure’ is broken.

In the case of the fires, we could have made better decisions. Better decisions – not least in relation to the challenges of global emissions, climate change, how and where we build our homes, etc. – will make a better world in which foreseeable suffering and destruction is avoided. That is one of the gifts of ethics.

Understood in this light, there is nothing intangible about ethics. It permeates our daily lives. It is expressed in phenomena that we can sense and feel.

So, if anyone is looking for a physical manifestation of ethical failure – breathe the smoke-filled air, see the blood-red sky, feel the slap from a wall of heat, hear the roar of the firestorm.

The fires will subside. The rains will come. The seasons will turn. However, we will still be left to decide for the future. Will our leaders have the moral courage to put the public interest before their political fortunes? Will we make the ethical choice and decide for a better world?

It is our task, at The Ethics Centre, to help society do just that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data and Development

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data & Development

Understand the ethical considerations in using big data across aid and development projects, and get a practical framework for decision making.

The increasing focus on impact, and its measurement is not solely about accountability. Instead, in this paper Dr Simon Longstaff presents why it’s driven by the desire to do as much good as possible in resource-constained conditions.

Traditionally the evaluation and monitoring of development based projects has been undertaken on the ground. However new technologies, big data, and AI have given rise to a host of possibilities, and with them, new ethical considerations.

The paper draws on insights generated by a project by Australia’s Department for Foreign Affairs, of which The Ethics Centre has been in consultation.

It offers an example Ethical Framework for decision making in new technology innovation for womens’ empowerment in Afghanistan, and a host of core tenants or considerations specific to the measurement and evaluation of development projects across areas of organisation, projects and data.

The report also provides a practical understanding of the components of an Ethical Framework, the virtue of ethical restraint, and the role of value driven decision making to benefit vulnerable groups in aid development work. Plus access a decision making model to slow down thinking and consider new perspectives.

It’s a great resource for anyone working with or associated with aid work domestically or internationally, particularly those involved in evaluation, measurement and data collection.

"The ethical impulse that drives innovation in development is to be admired. It is the same impulse that has led a range of actors to explore the possibilities of new technologies – not least in the field of data science – to improve the quality of monitoring and evaluation"

DR SIMON LONGSTAFF

WHAT'S INSIDE?

Ethical restraint

Empowering the vulnerable

Ethical Framework

Ethical decision making model

AUTHORS

Authors

Dr Simon Longstaff

Dr Simon Longstaff has been Executive Director of The Ethics Centre for 30 years, working across business, government and society. He has a PhD in philosophy from Cambridge University, is a Fellow of CPA Australia and of the Royal Society of NSW, and an Honorary Professor at ANU National Centre for Indigenous Studies. Simon was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2013.

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946—present), one of world’s most influential living philosophers, is best known for applying rigorous logic to a range of practical issues from animal rights, giving to charity to the ethics of abortion and infanticide.

Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946 to Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivors. As a teen he declared his atheism and refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. After studying law, history and philosophy at Melbourne University, he won a scholarship to Oxford University, writing his thesis on civil disobedience. In 1996 he ran unsuccessfully for the Greens in the Victorian State Parliament, and he has held posts at Melbourne, Monash, New York, London and Princeton Universities. His impact on public debate and academic philosophy cannot be overstated.

A key aspect of Singer’s contributions is the idea of ‘equal consideration of interests’. This informs both his views towards animals and charity. It means that we should consider the interests of any sentient beings who have the capacity to suffer and feel pleasure and pain.

Singer is a consequentialist, which means he defines ethical actions as ones that maximise overall pleasure and reduce overall pain. Part of what makes him such a challenging and influential thinker is his application of utilitarianism to real-world problems to offer counter-intuitive yet compelling solutions.’

Are you speciesist?

While at Oxford, Singer recalls a conversation with a friend over lunch that was the “most formative experience of [his] life”. Singer had the meat spaghetti, whereas his friend opted for the salad. His friend was the “first ethical vegetarian” he’d met. Two weeks later, Singer became a vegetarian and several years later published his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975).

Singer’s argument for not eating meat is more-or-less the same as another utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham wrote that “the question is not can they reason or can they talk, but can they suffer?” Similarly, Singer argues that animals have the capacity to suffer. Just as we rightly condemn torture, we should also condemn practices like factory farming that inflict unjustifiable pain on non-human animals. He coined the term ‘speciesism’ to describe the privileging of humans over other animals.

Giving to charity

In Singer’s essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (1972), he argues that people in rich countries have a moral obligation to give to charities that help people in poverty overseas. He uses an analogy of a drowning child: if we were walking past a shallow pond and saw a child drowning, we would wade in and save the child, even if this meant wrecking our favourite and most expensive pair of shoes. Likewise, because we know there are children dying overseas from preventable poverty-related diseases, we should be giving at least some of our income to charities that fight this.

Opponents to Singer argue that his view about giving to charity is psychologically untenable, and that there are differences between giving to charity and saving a drowning child. For example, the physical act of pulling a child out from water is more morally compelling than sending a cheque overseas. Other arguments include: we don’t know the child will definitely be saved when we send the cheque, fighting poverty requires a collective global effort not just an individual donation, and charities are ineffective and have high overhead costs.

Singer concedes that there may be psychological reasons why people would save the drowning child yet don’t give much to charity, but he says even if it seems strange, rationally there are no relevant moral differences between the cases.

Responding to the criticism that charities may not be effective has led Singer to be a proponent of ‘effective altruism’. In his book The Most Good You Can Do (2015) he describes how a number of charity evaluators can recommend the most cost-effective way to do good. Singer recommends giving on a progressive scale, depending on one’s income.

Instead of pursuing careers in academia, some of Singer’s brightest past students have decided to work for Wall Street to make as much money as possible to then give this away to effective charities.

Controversy around infanticide

Singer has faced sustained criticism and protest throughout his career for his views on the sanctity of life and disability – especially in Germany, where in the 90’s, his views were compared to Nazism and university courses that set his books were boycotted. While he has always been a staunch supporter of abortion on the grounds that a foetus lacks self-consciousness and the criteria of personhood, he argues there is no moral difference between abortion in the womb and killing a newborn. Furthermore, because a newborn cannot yet be classified as a person, if its parents do not want it to survive, or if it has an extreme disability meaning that keeping it alive would be very costly, there is potential justification in killing it.

Religious sanctity-of-life critics argue that Singer’s ethics ignore the fundamental sanctity of human life. Disability rights advocates argue that Singer’s views are ableist, explaining that the quality of life of a disabled person is less than that of a non-disabled person ignores the socially-constructed nature of disability – its harms and inconveniences are largely because the built environment is made for able-bodied people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 21 AUG 2019

The Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has attributed his electoral success to the influence of ‘Quiet Australians’.

It is an evocative term that pitches somewhere between that of the ‘silent majority’ and Sir Robert Menzies’ concept of the ‘Forgotten People’. Unfortunately, I think that the phrase will have a limited shelf-life because increasing numbers of Australians are sick of being quiet and unobserved.

In the course of the last federal election, I listened to three mayors being interviewed about the political mood of their rural and regional electorates. They said people would vote to ensure that their electorates became ‘marginal’. Despite their political differences, they were unanimous in their belief that this was the only way to be noticed. They are the cool tip of a volcano of discontent.

Quiet or invisible?

Put simply, I think that most Australians are not so much ‘quiet’, as ‘invisible’ – unseen by a political class that only notices those who confer electoral advantage. Thus, the attention given to the marginal seat or the big donor or the person who can guarantee a favourable headline and so on…

The ‘invisible people’ are fearful and angry.

They fear that their jobs will be lost to expert systems and robots. They fear that, without a job, they will be unable to look after their families. They fear that the country is unprepared to meet and manage the profound challenges that they know to be coming – and that few in government are willing to name.

They are angry that they are held accountable to a higher standard than government ministers or those running large corporations. They are angry that they will be discarded as the ‘collateral damage’ of progress.

And in many ways, they are right.

Is democracy failing us?

After all, where is the evidence to show that our democracy is consciously crafting a just and orderly transition to a world in which climate change, technological innovation and new geopolitical realities are reshaping our society? Will democracy hold in such a world?

By definition, democracy accords a dignity to every citizen – not because they are a ‘customer’ of government, but – because citizens are the ultimate source of authority. The citizen is supposed to be at the centre of the democratic state. Their interests should be paramount.

Yet this fundamental ‘promise’ seems to have been broken. The tragedy in all of this is that most politicians are well-intentioned. They really do want to make a positive contribution to their society. Yet, somehow the democratic project is at risk of losing its legitimacy – after which it will almost certainly fail.

In the end, while it’s comforting to whinge about politicians, the media, and so on, the quality of democracy lies in the hands of the people. We cannot escape our responsibility. Nor can we afford to remain ‘quiet’. Instead, wherever and whoever we may be, let’s roar: We are citizens. We demand to be seen. We will be heard.

The Ethics Centre’s next IQ2 debate – Democracy is Failing the People – is on Tuesday 27 August at Sydney Town Hall. Presenter and comedian Craig Reucassel will join political veteran Amanda Vanstone to go up against youth activist Daisy Jeffrey and economist Dr Andrew Charlton to answer if democracy is serving us, or failing us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Join our newsletter

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Big Thinker: John Locke

English Philosopher John Locke (1632—1704) is behind many of the ideas we now take for granted in a liberal democracy. Amongst them, his defence of life and liberty as natural and fundamental human rights.

He was especially known for his liberal, anti-authoritarian theory of the state, his empirical theory of knowledge and his advocacy of religious toleration. Much of Locke’s work is characterised by an opposition to authoritarianism, both at the level of the individual and within institutions such as the government and church.

Born in 1632, in his time he gained fame arguing that the divine right of kings is not supported by scripture. Instead, he defended a limited government whose duty is to protect the rights and liberty of its citizens. This idea is familiar to us now, yet at the time it was revolutionary, arguing against the monarchy as the source of society’s governance. A familiar idea in modern day, at the time it was revolutionary – an argument to depart from the monarchy as the source of society’s governance.

In defending his stance, Locke appealed to the notion of natural rights. He invited us to imagine an initial ‘state of nature’ with no government, police or private property. Locke argued that humans could discover, through careful reasoning, that there are natural laws which suggest that we have natural rights to our own persons and to our own labour.

Eventually we could reason that we should create a social contract with others. Out of this contract would emerge our political obligations and the institution of private property. In Locke’s version of the social contract, a human “divests himself of his natural liberty, and puts on the bonds of civil society…agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community” and by submitting to majority rule form a government designed to protect their rights.

The limits of power

Locke’s argument also places limits on the proper use of power by government authorities. While civil society, as viewed through Locke’s liberalism, sees that the individual must sacrifice – or at least compromise – his/her freedom in the name of the public good, the public good ought not to interfere with the individual’s freedom.

Due to this emphasis on liberty, Locke defended a distinction between a public and a private realm. The public realm is that of politics and the individual’s role in the community as a part of the state, which may include, for example, voting or fighting for one’s country. The private realm is that of domesticity where power is parental (traditionally, ‘paternal’).

For Locke, government should not interfere in the private realm. He held the argument that citizens were entitled to protest or revolt or disband a government when it failed to protect their collective interests. On this view it is crucial we distinguish the legitimate from the illegitimate functions of institutions.

Locke asked us to use reason in order to seek the truth, rather than simply accept the opinion of those in positions of power or be swayed by superstition. In this way, we see Locke as an Enlightenment thinker –our natural reason a light that shines, guiding our understanding in order to reveal knowledge.

Knowledge and personal identity

As an empiricist, Locke believed we gain our knowledge through experiences in the world. In contrast to the views of his rationalist predecessor Descartes, Locke argued that we are born as a blank slate or a tabula rasa. This means that at birth our mind has no innate ideas – it is blank. As our mind develops, sensations give rise to simple ideas, from which we form those more complex.

This theory of learning gives rise to another radical idea for his time. Locke asserted that in order to help children avoid developing bad thinking habits, they should be trained to base their beliefs on sound evidence. The strength of our belief should correlate to how strong or weak the evidence for it happens to be.

Furthermore, for Locke, our consciousness is what makes us ‘us’, constituting our personal identity.

Locke’s legacy

We see Locke’s legacy in the 1776 US Declaration of Independence, which was founded on his natural rights theory of government and proclaimed ‘we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’.

Following on from his theory of human rights, we also see Locke’s legacy in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948. Philosophers debate as to whether such rights are indeed ‘natural’, or whether they have been ‘constructed’ and agreed upon by society as useful rules to adopt and enforce.

Locke’s lasting legacy is the argument that society ought to be ruled democratically in such a way as to protect the liberty and rights of its citizens. And that the government should never over-step its boundaries and must always remember it is a glorified secretary of the people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Libertarianism and the limits of freedom

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why certain things shouldn’t be “owned”

Join our newsletter