Big Thinker: Confucius

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

Confucius (551 BCE—479 BCE) was a scholar, teacher, and political adviser who used philosophy as a tool to answer what he considered to be the two most important questions in life… What is the right way to rule? And what is the right way to live?

While he never wrote down his teachings in a systematic treatise, bite sized snippets of his wisdom were recorded by his students in a book called the Analects.

Underpinning Confucian philosophy was a deeply held conviction that there is a virtuous way to behave in all situations and if this is adhered to society will be harmonious. Confucius established schools where he gave lectures about how to maintain political and personal virtue.

“It is virtuous manners which constitute the excellence of a neighborhood.”

His ideas set the agenda for political and moral philosophy in China for the next two millennia and are emerging once again as an influential school of thought.

Humble beginnings

Confucius was born in 551 BC in a north-eastern province of China. His father and mother died before he was 18, leaving him to fend for himself. While working as a shepherd and bookkeeper to survive, Confucius made time to rigorously study classic texts of ancient Chinese literature and philosophy.

At the age of 30, Confucius began teaching some of the foundational concepts he formulated through his studies. He developed a loyal following and quickly rose up the political ranks, eventually becoming the Prime Minister of his province.

But at the age of 55 he was exiled after offending a higher ranking official. This gave Confucius an opportunity to travel extensively around China, advising government officials and spreading his teachings.

He was eventually invited back to his home province and was allowed to re-establish his school, which grew to a size of 3000 students by the time he died at age 72.

The golden age

Underpinning much of Confucius’ thought was a belief that Chinese society had forgotten the wisdom of the past and that it was his duty to reawaken the people, particularly the young, to these ancient teachings.

Confucius idealised the historical Western Zhou Dynasty, a time, he claimed, when living standards were high, people lived and worked in peace and contentment, the leaders carried out their duties in accordance with their rank, and the social order was stable and harmonious.

Confucius devoted his life to teaching the wisdom of this ancient society to his contemporaries in the hope of reinventing it in the present. For this reason, he didn’t claim to be an original thinker, but a receptacle of past wisdom. “I transmit but do not innovate”, he said.

Dao, de, and ren

While Confucius never wrote a systematic philosophical treatise, there are three intertwined concepts that run through his philosophy: Dao, De, and Ren.

Dao: Confucius interpreted Dao to mean a Way of living, or more specifically the right Way of living. This was not a concept he made up. It was already a central part of Chinese belief systems about the natural order of the universe. Dao is a slippery but profound concept suggesting there is a singular Way to live that can be intuited from the universe, and that all of life should be directed towards living this Way. If the Way is followed, the individual and society will be in perfect harmony.

De: Confucius saw De as a type of virtue that lay latent in all humans but that had to be cultivated. It was the cultivation of this virtue, Confucius believed, that allowed a person to follow the Way. It was in family life that people learned how to cultivate and practice virtuous behaviours. In fact, many of the main Confucian virtues were derived from familial relationships. For example, the relationship between father and son defined the virtue of piety and the relationship between older and younger siblings defined the virtue of respect. For this reason, Confucian ethics did not leave much room for an individual to exist outside of a family structure. Knowing where you stood in your family and your society was key to living a virtuous life.

Ren: While most Confucian virtues were cultivated within a strict social and family structure, ren was a virtue that existed outside this dynamic. It can be translated loosely as benevolence, goodness, or human-heartedness.

Confucius taught that the ren person is one who has so completely mastered the Way that it becomes second nature to them. In this sense ren is not so much about individual actions but what type of person you are. If you perform your familial duties but do not do so with benevolence, then you are not virtuous. Ren was how something was done, rather than the act itself.

Contemporary influence and relevance

Confucius’ influence on Chinese society during his life and in the two millennia since has been enormous. His sound bite like philosophies became China’s handbook on politics and its code of personal morality.

“He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.”

It wasn’t until Mao’s Cultural Revolution that some of the basic tenets of Confucian ethics were publicly denounced for the first time. Mao was future oriented and utopian in his politics, and so Confucius’ idea of governance and ethics based in the ancient classics was considered dangerous and subversive. In fact, Mao’s Red Guards referred to the old sage as “The Number One Hooligan Old Kong”.

But in the past decade, the Communist Party has realised Confucius’ teachings might be useful again. The surge of wealth that has accompanied free market capitalism in China has meant that many of Mao’s ideologies no longer make sense for the government. This has prompted a resurgence of State led interest in Confucius as an alternative ideological underpinning for the current government.

While this is seen by many as a way for China to build a political future based on its philosophical past, others feel that the Communist Party has emphasised Confucian ideas about hierarchical social structure and obedience, while sidelining notions of virtue and benevolence.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

The idea of a UBI isn’t new. In fact, it has deep historical roots.

In Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, he writes that instead of punishing a poor person who steals bread, “it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody’s under the frightful necessity of becoming, first a thief, and then a corpse”.

Over three hundred years later, John Stuart Mill also supported the concept in Principles of Political Economy, arguing that “a certain minimum [income] assigned for subsistence of every member of the community, whether capable of labour or not” would give the poor an opportunity to lift themselves out of poverty.

In the 20th century, the UBI gained support from a diverse array of thinkers for very different reasons. Martin Luther King, for instance, saw a guaranteed payment as a way to uphold human rights in the face of poverty, while Milton Friedman understood it as a viable economic alternative to state welfare.

Would a UBI encourage laziness?

Yet, there has always been strong opposition to implementing basic income schemes. The most common argument is that receiving money for nothing undermines work ethic and encourages laziness. There are also concerns that many will use their basic income to support drug and alcohol addiction.

However, the only successfully implemented basic income scheme has shown these fears might be unfounded. In the 1980s, Alaska implemented a guaranteed income for long term residents as a way to efficiently distribute dividends from a commodity boom. A recent study of the scheme found full-time employment has not changed at all since it was introduced and the number of Alaskans working part-time has increased.

The success of this scheme has inspired other pilot projects in Kenya, Scotland, Uganda, the Netherlands, and the United States.

The rise of the robots

The growing fear that robots are going to take most of our jobs over the next few decades has added an extra urgency to the conversation around UBI. A number of leading technologists, including Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates, have suggested some form of basic income might be necessary to alleviate the effects of unemployment caused by automation.

In his bestselling book Rise of the Robots, Martin Ford argues that a basic income is the only way to stimulate the economy in an automated world. If we don’t distribute the abundant wealth generated by machines, he says, then there will be no one to buy the goods that are being manufactured, which will ultimately lead to a crisis in the capitalist economic model.

In their book Inventing the Future, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams agree that full automation will bring about a crisis in capitalism but see this as a good thing. Instead of using UBI as a way to save this economic system, the unconditional payment can be seen as a step towards implementing a socialist method of wealth distribution.

The future of work

Srnicek and Williams also claim that UBI would not only be a political and economic transformation, but a revolution of the spirit. Guaranteed payment, they say, will give the majority of humans, for the first time in history, the capacity to choose what to do with their time, to think deeply about their values, and to experiment with how to live their lives.

Bertrand Russell made a similar argument in his famous treatise on work, In Praise of Idleness. He writes that in a world where no one is compelled to work all day for wages, all will be able to think deeply about what it is they want to do with their lives and then pursue it. For many, he says, this idea is scary because we have become dependent on paid jobs to give us a sense of value and purpose.

So, while many of the debates about UBI take place between economists, it is possible that the greatest obstacle to its implementation is existential.

A basic payment might provide us with the material conditions to live comfortably, but with this comes the confounding task of re-thinking what it is that gives our lives meaning.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

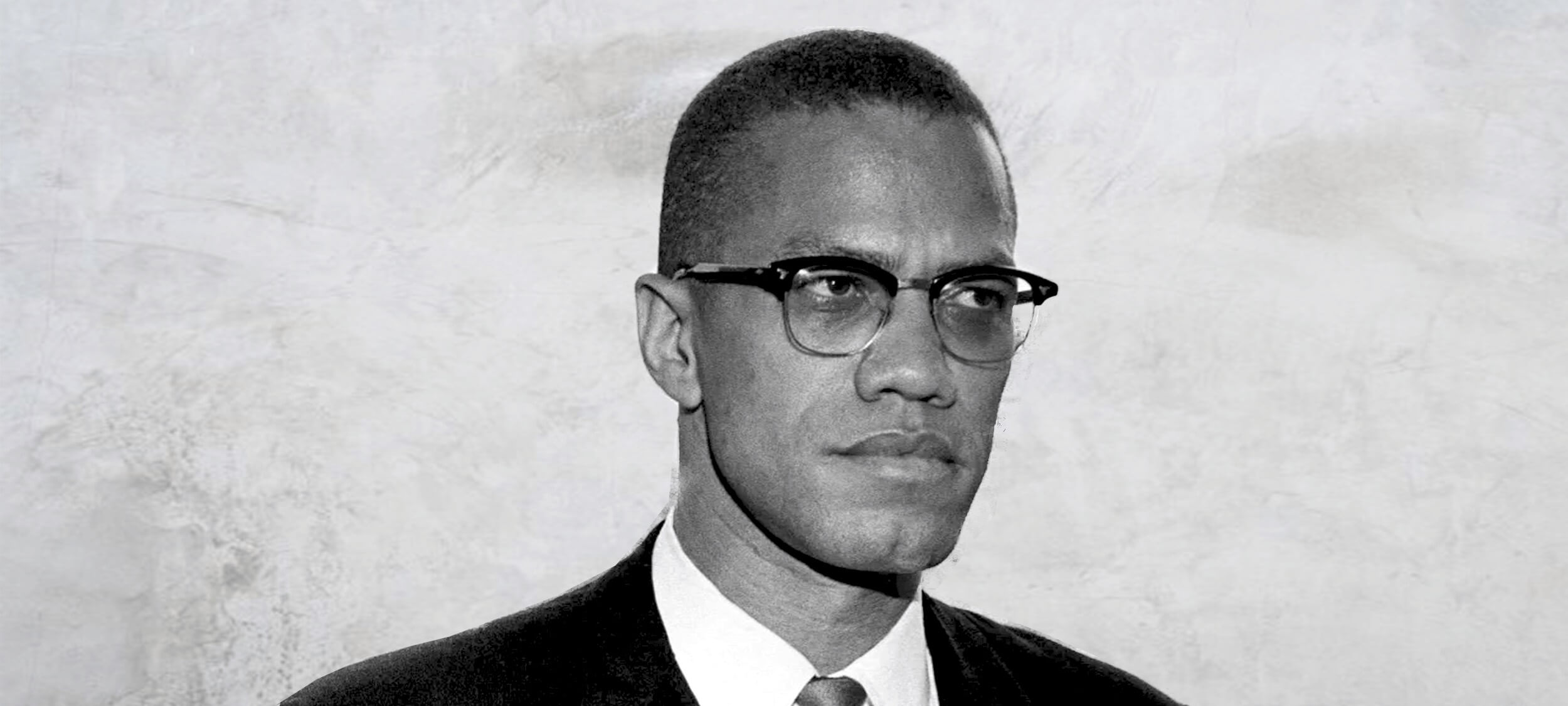

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 7 FEB 2018

Malcolm X (1925—1965) was a Muslim minister and controversial black civil rights activist.

To his admirers, he was a brave speaker of an unpalatable truth white America needed to hear. To his critics, he was a socially divisive advocate of violence. Neither will deny his impact on racial politics.

From tough childhood to influential adult

Malcolm X’s early years informed the man he became. He began life as Malcolm Little in the meatpacking town of Omaha, Nebraska before moving to Lansing, Michigan. Segregation, extreme poverty, incarceration, and violent racial protests were part of everyday life. Even lynchings, which overwhelmingly targeted black people, were still practiced when Malcolm X was born.

Malcolm X lost both parents young and lived in foster care. School, where he excelled, was cut short when he dropped out. He said a white teacher told him practicing law was “no realistic goal for a n*****”.

In the first of his many reinventions, Malcolm Little became Detroit Red, a ginger-haired New York teen hustling on the streets of Harlem. In his autobiography, Malcolm X tells of running bets and smoking weed.

He has been accused of overemphasising these more innocuous misdemeanours and concealing more nefarious crimes, such as serious drug addiction, pimping, gun running, and stealing from the very community he publicly defended.

At 20, Malcolm X landed in prison with a 10 year sentence for burglary. What might’ve been the short end to a tragic childhood became a place of metamorphosis. Detroit Red was nicknamed Satan in prison, for his bad temper, lack of faith, and preference to be alone.

He shrugged off this title and discarded his family name Little after being introduced to the Nation of Islam and its philosophies. It was, he explained, a name given to him by “the white man”. He was introduced to the prison library and he read voraciously. The influential thinker Malcolm X was born.

Upon his release, he became the spokesperson for the Nation of Islam and grew its membership from 500 to 30,000 in just over a decade. As David Remnick writes in the New Yorker, Malcolm X was “the most electrifying proponent of black nationalism alive”.

Be black and fight back

Malcolm X’s detractors did not view his idea of black power as racial equality. They saw it as pro-violent, anti-white racism in pursuit of black supremacy. But after his own life experiences and centuries of slavery and atrocities against African and Native Americans, many supported his radical voice as a necessary part of public debate. And debate he did.

Malcolm X strongly disagreed with the non-violent, integrationist approach of fellow civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. The differing philosophies of the two were widely covered in US media. Malcolm X believed neither of King’s strategies could give black people real equality because integration kept whiteness as a standard to aspire to and non-violence denied people the right of self defence. It was this take that earned him the reputation of being an advocate of violence.

“… our motto is ‘by any means necessary’.”

Malcolm X stood for black social and economic independence that you might label segregation. This looked like thriving black neighbourhoods, businesses, schools, hospitals, rehabilitation programs, rifle clubs, and literature. He proposed owning one’s blackness was the first step to real social recovery.

Unlike his peers in the civil rights movement who championed spiritual or moral solutions to racism, Malcolm X argued that wouldn’t cut it. He felt legalised and codified racial discrimination was a tangible problem, requiring structural treatment.

Malcolm X held that the issues currently facing him, his family, and his community could only be understood by studying history. He traced threads between a racist white police officer to the prison industrial complex, to lynching, slavery, and then to European colonisation.

Despite his great respect for books, Malcolm X did not accept them as “truth”. This was important because the lives of black Americans were often hugely different from what was written about – not by – them.

Every Sunday, he walked around his neighbourhood to listen to how his community was going. By coupling those conversations with his study, Malcolm X could refine and draw causes for grievances black people had long accepted – or learned to ignore.

We are human after all

Dissatisfied with their leader, Malcolm X split from the Nation of Islam (who would go on to assassinate him). This marked another transformation. He became the first reported black American to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. In his final renaming, he returned to the US as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

On his pilgrimage, he had spoken with Middle Eastern and African leaders, and according to his ‘Letter from Mecca’ (also referred to as the ‘Letter from Hajj’), began to reappraise “the white man”.

Malcolm X met white men who “were more genuinely brotherly than anyone else had ever been”. He began to understand “whiteness” to be less about colour, and more about attitudes of oppressive supremacy. He began to see colonialist parallels between his home country and those he visited in the Middle East and Africa.

Malcolm X believed there was no difference between the black man’s struggle for dignity in America and the struggle for independence from Britain in Ghana. Towards the end of his life, he spoke of the struggle for black civil rights as a struggle for human rights.

This move from civil to human rights was more than semantics. It made the issue international. Malcolm X sought to transcend the US government and directly appeal to the United Nations and Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead.

In a way, Malcolm X was promoting a form of globalisation, where the individual, rather than the nation, was on centre stage. Oppressed people took back their agency to define what equality meant, instead of governments and courts. And in doing so, he linked social revolution to human rights.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Education is more than an employment outcome

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 31 JAN 2018

The exposure of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein as a serial harasser and alleged rapist in October 2017 was the tipping point in an unprecedented outpouring of sexual coercion and assault disclosures.

As high profile women spoke out about the systemic misogyny of the entertainment industry, they have been joined by women around the globe using #MeToo to make visible a spectrum of experiences from the subtle humiliations of sexism to criminal violation.

The #MeToo movement has exposed not only the pervasiveness of gendered abuse but also its accommodation by the very workplaces and authorities that are supposed to ensure women’s safety. Some women (and men) have been driven to name their perpetrator via the mass media or social media, in frustration over the inaction of their employers, industries, and police. This has sparked predictable complaints about ‘witch hunts’, ‘sex panics’, and the circumvention of ‘due process’ in the criminal justice system.

Mass media and social media have a critical role in highlighting institutional failure and hypocrisy. Sexual harassment and violence are endemic precisely because the criminal justice system is failing to deter this conduct or hold perpetrators to account. The friction between the principles of due process (including the presumption of innocence) and the current spate of public accusations is symptomatic of the wholesale failure of the authorities to uphold women’s rights or take their complaints seriously.

Public allegations are one way of forcing change, and often to great effect. For instance, the recent Royal Commission into child sexual abuse was sparked by years of media pressure over clergy abuse.

While ‘trial by media’ is sometimes necessary and effective, it is far from perfect. Journalists have commercial as well as ethical reasons for pursuing stories of abuse and harassment, particularly those against celebrities, which are likely to attract a significant readership. The implements of media justice are both blunt and devastating, and in the current milieu, include serious reputational damage and potential career destruction.

The implements of media justice are both blunt and devastating.

These consequences seemed fitting for men like Weinstein, given the number, severity and consistency of the allegations against him and others. However, #MeToo has also exposed more subtle and routine forms of sexual humiliation. These are the sexual experiences that are unwanted but not illegal, occurring in ways that one partner would not choose if they were asked. These scenarios don’t necessarily involve harmful intent or threat. Instead, they are driven by the sexual scripts and stereotypes that bind men and women to patterns of sexual advance and reluctant acquiescence.

The problem is that online justice is an all-or-nothing proposition. Punishment is not dolled out proportionately or necessarily fairly. Discussions about contradictory sexual expectations and failures of communication require sensitivity and nuance, which is often lost within spontaneous hashtag movements like #MeToo. This underscores the fragile ethics of online justice movements which, while seeking to expose unethical behaviour, can perpetrate harm of their own.

The Aziz Ansari Moment

The allegations against American comedian Aziz Ansari were the first real ‘record-scratch’ moment of #MeToo. Previous accusations against figures such as Weinstein were broken by reputable outlets after careful investigation, often uncovering multiple alleged victims, many of whom were willing to be publicly named. Their stories involved gross if not criminal misconduct and exploitation. In Ansari’s case, the allegations against him were aired by the previously obscure website Babe.net, who interviewed the pseudonymous ‘Grace’ about a demeaning date with Ansari. Grace did not approach Babe with her account. Instead, Babe heard rumours about her encounter and spoke to several people in their efforts to find and interview Grace.

In the article, Grace described how her initial feelings of “excitement” at having dinner with the famous comedian changed when she accompanied him to his apartment. She felt uncomfortable with how quickly he undressed them both and initiated sexual activity. Grace expressed her discomfort to Ansari using “verbal and non-verbal cues”, which she said mostly involved “pulling away and mumbling”. They engaged in oral sex, and when Ansari pressed for intercourse, Grace declined. They spent more time talking in the apartment naked, with Ansari making sexual advances, before he suggested they put their clothes back on. After he continued to kiss and touch her, Grace said she wanted to leave, and Ansari called her a car.

In the article, Grace she had been unsure if the date was an “awkward sexual experience or sexual assault”, but she now viewed it as “sexual assault”. She emphasised how distressed she felt during her time with Ansari, and the implication of the article was that her distress should have been obvious to him. However, in response to the publication of the article, Ansari stated that that their encounter “by all indications was completely consensual” and he had been “surprised and concerned” to learn she felt otherwise.

Sexual humiliation and responsibility

Responses to Grace’s story were mixed in terms of to whom, and how, responsibility was attributed. Initial reactions on social media insisting that, if Grace felt she had been sexually assaulted, then she had been, gave way to a general consensus that Ansari was not legally responsible for what occurred in his apartment with Grace. Despite Grace’s feelings of violation, there was no description of sexual assault in the article. Even attributions of “aggression” or “coercion” seem exaggerated. Ansari appears, in Grace’s account, persistent and insensitive, but responsive to her when she was explicit about her discomfort.

A number of articles emphasised that Grace’s story was part of an important discussion about how “men are taught to wear women down to acquiescence rather than looking for an enthusiastic yes”. Such encounters may not meet the criminal standard for sexual assault, but they are still harmful and all too common.

For this reason, many believed that Ansari was morally responsible for what happened in his apartment that night. This is the much more defensible argument, and, perhaps, one that Ansari might agree with. After all, Ansari has engaged in acts of moral responsibility. When Grace contacted him via text the next day to explain that his behaviour the night before had made her “uneasy”, he apologised to her with the statement, “Clearly, I misread things in the moment and I’m truly sorry”.

However, attributing moral responsibility to Ansari for his behaviour towards Grace does not justify exposing him to the same social and professional penalties as Weinstein and other alleged serious offenders. Nor does it eclipse Babe’s responsibility for the publication of the article, including the consequences for Ansari or, indeed, for Grace, who was framed in the article as passive and unable to articulate her wants or needs to Ansari.

Discussions about contradictory sexual expectations and failures of communication require sensitivity and nuance, which is often lost within spontaneous hashtag movements like #MeToo.

For some, the apparent disproportionality between Ansari’s alleged behaviour and the reputational damage caused by Babe’s article was irrelevant. One commentator said that she won’t be “fretting about one comic’s career” because Aziz Ansari is just “collateral damage” on the path to a better future promised by #MeToo. At least in part, Ansari is attributed causal responsibility – he was one cog in a larger system of misogyny, and if he is destroyed as the system is transformed, so be it.

This position is not only morally indefensible – dismissing “collateral damage” as the cost of progress is not generally considered a principled stance – but it is unlikely to achieve its goal. A movement that dispenses with ethical judgment in the promotion of sexual ethics is essentially pulling the rug out from under itself. Furthermore, the argument is not coherent. Ansari can’t be held causally responsible for effects of a system that he, himself, is bound up within. If the causal factor is identified as the larger misogynist system, then the solution must be systemic.

Hashtag justice needs hashtag ethics

Notions of accountability and responsibility are central to the anti-violence and women’s movements. However, when we talk about holding men accountable and responsible for violence against women, we need to be specific about what this means. Much of the potency of movements like #MeToo come from the promise that at least some men will be held accountable for their misconduct, and the systems that promote and camouflage misogyny and assault will change. This is an ethical endeavour and must be underpinned by a robust ethical framework.

The Ansari moment in #MeToo raised fundamental questions not only about men’s responsibilities for sexual violence and coercion, but also about our own responsibilities responding to it. Ignoring the ethical implications of the very methods we use to denounce unethical behaviour is not only hypocritical, but fuels reactionary claims that collective struggles against sexism are neurotic and hysterical. We cannot insist on ethical transformation in sexual practices without modelling ethical practice ourselves. What we need, in effect, are ‘hashtag ethics’ – substantive ethical frameworks that underpin online social movements.

This is easier said than done. The fluidity of hashtags makes them amenable to misdirection and commodification. The pace and momentum of online justice movements can overlook relevant distinctions and conflate individual and social problems, spurred on by media outlets looking to draw clicks, eyeballs and advertising revenue. Online ethics, then, requires a critical perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of online justice. #MeToo is not an end in itself that must be defended at all costs. It’s a means to an end, and one that must be subject to ethical reflection and critique even as it is under way.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

BY Michael Salter

Scientia Fellow and Associate Professor of Criminology UNSW. Board of Directors ISSTD. Specialises in complex trauma & organisedabuse.com

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia Day and #changethedate - a tale of two truths

Australia Day and #changethedate – a tale of two truths

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 JAN 2018

The recent debate about whether or not Australia Day should be celebrated on 26th January has been turned into a contest between two rival accounts of history.

On one hand, the ‘white arm band’ promotes Captain Arthur Phillip’s arrival in Port Jackson as the beginning of a generally positive story in which the European Enlightenment is transplanted to a new continent and gives rise to a peaceful, prosperous, modern nation that should be celebrated as the envy of the world.

On the other hand, the ‘black arm band’ describes the British arrival as an invasion that forcefully and unjustly dispossesses the original owners of their land and resources, ravages the world’s oldest continuous culture, and pushes to the margins those who had been proud custodians of the continent for sixty millennia.

This contest has become rich pickings for mainstream and social media where, in the name of balance, each side has been pitched against the other in a fight that assumes a binary choice between two apparently incommensurate truths.

However, what if this is not a fair representation of the what is really at stake here? What if there is truth on both sides of the argument?

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that the First Fleet brought many things. Some were good and some were not. Much that is genuinely admirable about Australia can be traced back to those British antecedents. The ‘rule of law’, the methods of science, the principle of respect for the intrinsic dignity of persons… are just a few examples of a heritage that has been both noble in its inspiration and transformative in its application in Australia.

Of course, there are dark stains in the nation’s history – most notably in relation to the treatment of Indigenous Australians. Not only were the reasonable hopes and aspirations of Indigenous people betrayed – so were the ideals of the British who had been specifically instructed to respect the interests of the Aboriginal peoples of New Holland (as the British called their foothold on the continent).

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that both accounts are true. And so is our current incapacity to realise this.

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that the arrival of the Europeans was a disaster for those already living here for generations beyond human memory. This was the same kind of disaster that befell the Britons with the arrival of the Romans, the same kind of disaster visited on the Anglo-Saxons when invaded by the Vikings and their Norman kin. Land was taken without regard for prior claims. Language was suppressed, if not destroyed. Local religions trashed. All taken – by conquest.

No reasonable person can believe the arrival of Europeans was not a disaster for Indigenous people. They fought. They lost. But they were not defeated. They survive. Some flourish. Yet with only two hundred or so years having passed since European arrival, the wounds remain.

The truth – that is, the whole truth – is that both accounts are true. And so is our current incapacity to realise this. Instead we are driven by politicians and commentators and, perhaps, the temper of the times, to see the world as one of polar opposites. It is a world of winners and losers, a world where all virtue is supposed to lie on just one side of a question, a world in which we are cut by the brittle, crystalline edges of ideological certainty.

So, what are we to make of January 26th? The answer depends on what we think is to be done on this day.

One of the great skills cultivated by ethical people is the capacity for curiosity, moral imagination and reasonable doubt. Taken together, these attributes allow us to see the larger picture – the proverbial forest that is obscured by the trees. This is not an invitation to engage in some kind of relativism – in which ‘truth’ is reduced to mere opinion. Instead, it is to recognise that the truth – the whole truth – frequently has many sides and that each of them must be seen if the truth is to be known.

But first you have to look. Then you have to learn to see what might otherwise be obscured by old habits, prejudice, passion, anger… whatever your original position might have been.

So, what are we to make of January 26th? The answer depends on what we think is to be done on this day. Is it a time of reflection and self-examination? If so, then January 26th is a potent anniversary. If, on the other hand, it is meant to be a celebration of and for all Australians, then why choose a date which represents loss and suffering for so many of our fellow citizens?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2017

TIME Magazine’s announcement comes amid a storm of reckoning with sexual harassment and abuse charges in power centres worldwide. The courageous victims who, over the past few months, surfaced and made public their experiences of sexual harassment have sparked a social movement – typified in the hashtag #MeToo.

One of the features of the numerous sexual harassment claims that have been made public is the number of victims that have come forward after the first allegations have surfaced. Women, many of whom have suffered in silence for a considerable period of time, all of a sudden have found their voice.

As an outsider not involved in these incidents, this pattern of behaviour might be difficult to comprehend. Surely victims would speak up and take their concerns to the appropriate authorities? Unfortunately, we are very poor at judging how we would behave when we are placed in difficult, stressful situations, as previous research has found.

How we imagine we would respond in hypothetical situations as an outsider differs significantly to how we would respond in reality – we are very poor at appreciating how the situation can influence our conduct.

In 2001, Julie Woodzicka and Marianne LaFrance asked 197 women how they would respond in a job interview if a man aged in his thirties asked them the following questions: “Do you have a boyfriend?”, “Do people find you desirable?” and “Do you think women should be required to wear bras at work?” Over two-thirds said they would refuse to answer at least one of the questions whilst sixteen of the participants said they would get up and leave.

When Woodzicka and LaFrance placed 25 women in this situation (with an actor playing the role of the interviewer), the results were vastly different. None of the women refused to answer the questions or left the interview.

In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

And there are many reasons why people remain silent. Three of the most common are fear, futility and loyalty – we fear consequences, we surmise that speaking up is futile because no action will be taken, or, as strange as it might sound, we feel a sense of loyalty to the perpetrator or our team.

There are a variety of dynamics that can cause people to reach these conclusions. The most common is power. In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

In these types of situations, it is easy to see how the victim can lose their sense of agency and feel disempowered. They might feel that even if they did speak up, nobody would believe their story. The mere thought of challenging such a “highly respected” individual is too daunting. Worse yet, their career would be irreparably damaged. Perhaps, by keeping quiet, they could get the break they need and put the experience behind them.

A second dynamic at play is what psychologists refer to as pluralistic ignorance. First conceived in the 1930s, it proposes that the silence of people within a group promotes a misguided belief of what group members are really thinking and feeling.

In the case of sexual harassment, when victims remain silent they create the illusion that the abuse is not widespread. Each victim feels they are isolated and suffering alone, further increasing the likelihood that they will repress their feelings.

By speaking out, women have shifted the norms surrounding sexual assault. Behaviour which may have been tolerated only a few years (perhaps months) ago is now out of bounds.

But as the events of the past few weeks have demonstrated, the norms promoting silence can crumble very quickly. People who suppress their feelings can find their voice as others around them break their silence. As U.S. legal scholar Cass Sunstein recently wrote in the Harvard Law Review Blog, as norms are revised, “what was once unsayable is said, and what was once unthinkable is done.”

And this is exactly what has happened over the past few months. Both perpetrators and victims alike are now reflecting on past indiscretions and questioning whether boundaries were crossed.

Only time will tell whether the shift in norms is permanent or fleeting. As is always the case with changes in social attitudes, this will be determined by a myriad of factors. The law plays a role but as the events of the past few months have demonstrated it is not as important as one might think.

Among other things, it will require the continued courage of victims. But perhaps more importantly it will require men, especially those who are in positions of power and respected members of our communities and institutions, to role model where the balance resides between extreme prudery at one end, and disgusting lechery on the other.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: Should I tell my student’s parents what they’ve been confiding in me?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

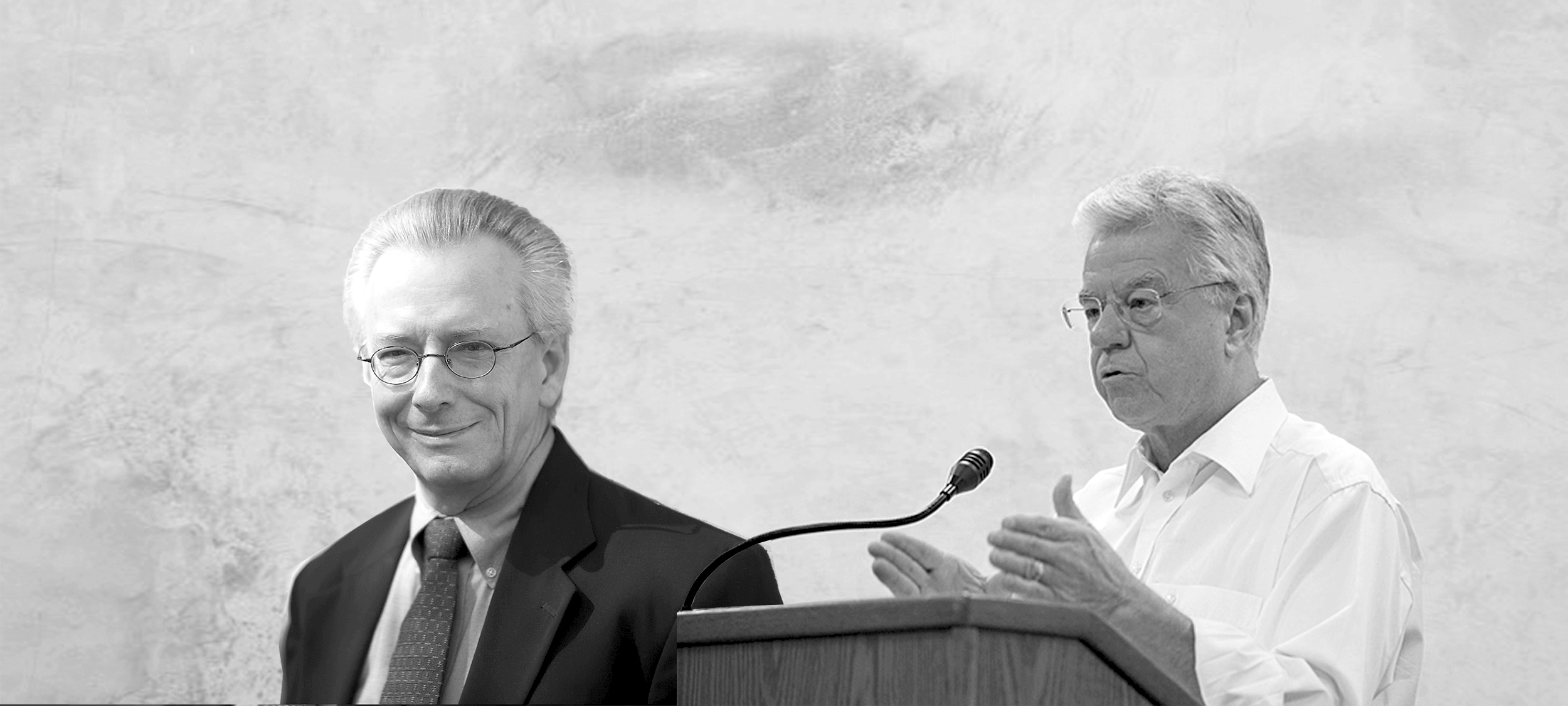

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 1 DEC 2017

Thomas L Beauchamp (1939—present) and James F Childress (1940—present) are American philosophers, best known for their work in medical ethics. Their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics was first published in 1985, where it quickly became a must read for medical students, researchers, and academics.

Written in the wake of some horrific biomedical experiments – most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where hundreds of rural black men, their partners, and subsequent children were infected or died from treatable syphilis – Principles of Biomedical Ethics aimed to identify healthcare’s “common morality”. These are its four principles:

- Respect for autonomy

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

These principles are often in tension with one another, but all healthcare workers and researchers need to factor each into their reflections on what to do in a situation.

Respect for autonomy

Philosophers usually talk about autonomy as a fact of human existence. We are responsible for what we do and ultimately any action we take is the product of our own choice. Recognising this basic freedom at the heart of humanity is a starting point for Beauchamp and Childress.

By itself, the idea human beings are free and in control of themselves isn’t especially interesting. But in a healthcare setting, where patients are often vulnerable and surrounded by experts, it is easy for a patient’s autonomous decision to be disrespected.

Beauchamp and Childress were writing at a time when the expertise of doctors meant they often took extreme measures in doing what they had decided was in the best interests of their patient. They adopted a paternalistic approach, treating their patients like uninformed children rather than autonomous, capable adults. This went as far as performing involuntary sterilisations. In one widely discussed court case in bioethics, Madrigal v Quillian, ten Latina women in the US successfully sued after doctors performed hysterectomies on them without their informed consent.

Legally speaking, the women in Madrigal v Quillian had provided consent. However, Beauchamp and Childress explain clearly why the kind of consent they provided isn’t adequate. The women – who spoke Spanish as a first language – were all being given emergency caesareans. They were asked to sign consent forms written in English which empowered doctors to do what they deemed medically necessary.

In doing so, they weren’t being given the ability to exercise their autonomy. The consent they provided was essentially meaningless.

To address this issue, Beauchamp and Childress encourage us to think about autonomy as creating both ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ duties. The negative duty influences what we must not do: “autonomous actions should not be subject to controlling constraints by others”, they write. But positively, autonomy also requires “respectful treatment in disclosing information” so people can make their own decisions.

Respecting autonomy isn’t just about waiting for someone to give you the OK. It’s about empowering their decision making so you’re confident they’re as free as possible under the circumstances.

Nonmaleficence: ‘first do no harm’

The origins of medical ethics lie in the Hippocratic Oath, which although it includes a lot of different ideas, is often condensed to ‘first do no harm’. This principle, which captures what Beauchamp and Childress mean by non-maleficence, seems sensible on one level and almost impossible to do in practice on another.

Medicine routinely involves doing things most people would consider harmful. Surgeons cut people open, doctors write prescriptions for medicines with a range of side effects, researchers give sick people experimental drugs – the list goes on. If the first thing you did in medicine was to do no harm, it’s hard to see what you might do second.

This is clearly too broad a definition of harm to be useful. Instead, Beauchamp and Childress provide some helpful nuance, suggesting in practice, ‘first do no harm’ means avoiding anything which is unnecessarily or unjustifiably harmful. All medicine has some risk. The relevant question is whether the level of harm is proportionate to the good it might achieve and whether there are other procedures that might achieve the same result without causing as much harm.

Beneficence: do as much good as you can

Some people have suggested Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles are three principles. They suggest beneficence and non-maleficence are two sides of the same coin.

Beneficence refers to acts of kindness, charity and altruism. A beneficent person does more than the bare minimum. In a medical context, this means not only ensuring you don’t treat a patient badly but ensuring you treat them well.

The applications of beneficence in healthcare are wide reaching. On an individual level, beneficence will require doctors to be compassionate, empathetic and sensitive in their ‘bedside manner’. On a larger level, beneficence can determine how a national health system approaches a problem like organ donation – making it an ‘opt out’ instead of ‘opt in’ system.

The principle of beneficence can often clash with the principle of autonomy. If a patient hasn’t consented to a procedure which could be in their best interests, what should a doctor do?

Beauchamp and Childress think autonomy can only be violated in the most extreme circumstances: when there is risk of serious and preventable harm, the benefits of a procedure outweigh the risks and the path of action empowers autonomy as much as possible whilst still administering treatment.

However, given the administration of medical procedures without consent can result in legal charges of assault or battery in Australia, there is clearly still debate around how to best balance these two principles.

Justice: distribute health resources fairly

Healthcare often operates with limited resources. As much as we would like to treat everyone, sometimes there aren’t enough beds, doctors, nurses or medications to go around. Justice is the principle that helps us determine who gets priority in these cases.

However, rather than providing their own theory, Beauchamp and Childress pointed out the various different philosophical theories of justice in circulation. They observe how resources are distributed will depend on which theory of justice a society subscribes to.

For example, a consequentialist approach to justice will distribute resources in the way that generates the best outcomes or most happiness. This might mean leaving an elderly patient with no dependents to die in order to save a parent with young children.

By contrast, they suggest someone like John Rawls would want the access to health resources to be allocated according to principles every person could agree to. This might suggest we allocate resources on the basis of who needs treatment the most, which is the way paramedics and emergency workers think when performing triage.

Beauchamp and Childress’s treatment of justice highlights one of the major criticisms of their work: it isn’t precise enough to help people decide what to do. If somebody wants to work out how to distribute resources, they might not want to be shown several theories to choose between. They want to be given a framework for answering the question. Of course when it comes to life and death decisions, there are no easy answers.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why certain things shouldn’t be “owned”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2017

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759—1797) is best known as one of the first female public advocates for women’s rights. Sometimes known as a “proto-feminist”, her significant contributions to feminist thought were written a century before the word “feminism” was coined.

Wollstonecraft was ahead of her time, both intellectually and in the way she lived. Pursuing a writing career was unconventional for women in 18th century England and she was denounced for nearly a century after her death for having a child out of wedlock. But later, during the rise of the women’s movement, her work was rediscovered.

Wollstonecraft wrote many different kinds of texts – including philosophy, a children’s book, a fictional novel, socio-political pamphlets, travel writings, and a history of the French Revolution. Her most famous work is her essay, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Pioneering modern feminism

Wollstonecraft passionately articulated the basic premise of feminism in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – that women should have equal rights to men. Though the essay was published during the French Revolution in 1792, its core argument that women are unjustifiably rendered subordinate to men remains.

Rather than domestic violence, women in senior roles and the gender pay gap, Wollstonecraft took aim at marriage, beauty, and women’s lack of education.

The good wife: docile and pretty

At the core of Wollstonecraft’s critique was the socioeconomic necessity for marriage – “the only way women can rise in the world”. In short, she argued marriage infantilised women and made them miserable.

Wollstonecraft described women as sacrificing respect and character for far less enduring traits that would make them an attractive spouse – such as beauty, docility, and the 18th century notion of sensibility. She argued, “the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement” and they were “so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence”.

Mother of feminism and victim blamer?

Some readers of A Vindication for the Rights of Woman argued Wollstonecraft was only a small step away from victim blaming. She penned plenty of lines positioning women as wilful and active contributors to their own subjugation.

In Wollstonecraft’s eye, expressions of feminine gender were “frivolous pursuits” chosen over admirable qualities that could lift the social standing of her sex and earn women respect, dignity and quality relationships:

“…the civilised women of the present century, with few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.”

While some might find Wollstonecraft was too harsh on the women she wanted to lift, her spear was very much aimed at men, “who considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives”.

Grab it by the patriarchy

Like the word feminism, the word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft. She nevertheless argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

Wollstonecraft commented on men’s “physical superiority” although she did not accept social superiority should follow.

“…not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment.”

Wollstonecraft’s hammering critique against a male dominated society suggested women were forced to be complicit. They had few work options, no property or inheritance rights, and no access to formal education. Without marriage, women were destined to poverty.

What do we want? Education!

Wollstonecraft pointed out all people regardless of sex are born with reason and are capable of learning.

In a time where it was considered racial to insist women were rational beings, Wollstonecraft raised the common societal belief that women lacked the same level of intelligence as men. Women only appeared less intelligent, Wollstonecraft argued, because they were “kept in ignorance”, housebound and denied the formal education afforded to men.

Instead of receiving a useful education, women spent years refining an appealing sexual nature. Wollstonecraft felt “strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty”. Women’s time was poorly invested.

How could women, who were responsible for raising children and maintaining the home, be good mothers, good household managers or good companions to their husbands, if they were denied education? Women’s education, Wollstonecraft contended, would benefit all of society.

Wollstonecraft suggested a free national schooling system where girls and boys were taught together. Mixed sex education, she argued, “would render mankind more virtuous, and happier” – because society and the term mankind itself would no longer exclude girls and women.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2017

Dennis Altman (1943—present) is an internationally renowned queer theorist, Australian professor of politics and current Professorial Fellow at La Trobe University.

Beginning his intellectual career in the 1970s, his impact on queer thinking and gay liberation can be likened to Germaine Greer’s contributions to the women’s movement.

Much of Altman’s work explores the differences between gay radical activists who question heteronormative social structures like marriage and nuclear family, and gay equality activists who want the same access to such structures.

“Young queers today are caught up in the same dilemma that confronted the founders of the gay and lesbian movements: Do we want to demonstrate that we are just like everyone else, or do we want to build alternatives to the dominant sexual and emotional patterns?”

Divided in diversity, united in oppression

Altman’s influential contribution to gay rights began with his first of many books, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. The 1971 text has been published in several countries and is still widely read today. It is often regarded as an uncannily correct prediction of how gay rights would improve over the decades – something that would have been difficult to imagine when the first Sydney Mardi Gras was met with police violence.

Altman predicted homosexuality would become normalised and accepted over time. As oppressions ceased, and liberation was realised, sexual identities would become less important and the divisions between homosexual and heterosexual would erode. Eventually, openly gay people would come to be defined the way straight people were – by characteristics other than their sexuality like their job, achievements or interests.

Despite gay communities being home to diversity and division, the shared experience of discrimination bonded them, Altman argued. Much like women’s and black civil rights advocates could testify, oppression has an upside – it forms communities.

End of the homosexual?

Altman’s 2013 book The End of the Homosexual? follows on from the ideas in his first. It is often described as a sequel despite the 40 years and several other publications between the two. He wrote it at a time when same sex marriage was beginning to be legalised around the world.

Altman recently reflected on his old work and said he was wrong to believe identity would become less important as acceptance grew but right to predict being gay would not be people’s defining characteristic.

He has come across as both happy and disappointed by the normalisation of same sex relationships. While massive reductions in violence and systemic discrimination is something you can only celebrate, Altman almost mourns the loss of the radical roots of gay liberation that formed in response to such injustices.

Without the oppressions of yesteryear, what binds diverse people into gay communities today? What distinguishes between a ‘gay lifestyle’ and a ‘straight lifestyle’ when they share so many characteristics like marriage, children, and general social acceptance?

Of course, all things are still not equal today. While people in the West largely enjoy safety and equality, people in countries like Russia are experiencing regressions. Altman hopes gay liberationists could have impact there.

Same sex marriage

Although he’s considered a pioneer in queer theory, a field that questions dominant heterosexual social structures, Altman does not support same sex marriage.

Some people might feel a sense of betrayal that such a well respected gay public intellectual has not put his influence behind this campaign. But Altman’s lack of support is completely consistent with the thinking he has been sharing for decades. Like a radical women’s liberationist, he has reservations about marriage itself – whether it’s same sex or opposite sex.

Altman takes issue with traditional marriage’s “assumption that there is only one way of living a life”. He has long been concerned the positioning of wedlock as the norm forgets all the people who are not living in long term, monogamous relationships. He argues marriage isn’t even all that normal in Australia anymore with single person households growing faster than any other category.

Altman was with his spouse for 20 years until death parted them. While that may sound like a marriage, the role of state and Church deeply bothers him, and so they were together without the blessings of those institutions. He has expressed confusion over the popular desire to be approved by the state or religious bodies that do not want to sanction same sex relationships. It’s because he doesn’t consider same sex marriage a human rights issue, when compared to things like starvation, oppression, and other forms of suffering.

Nevertheless, Altman recognises the importance of equal rights and understands why marriage for heterosexuals and not homosexuals is unfair. True to form he continues to question the institution itself by flipping the marriage equality argument on its head. He advocates for “the equal right not to marry”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2017

Making sense of our lives means thinking about death. Some philosophers, like Martin Heidegger and Albert Camus, thought death was a crucial, defining aspect of our humanity.

Camus went so far as to say considering whether to kill oneself was the only real philosophical question.

What these philosophers understood was that the philosophical dream of living a meaningful life includes the question of what a meaningful death looks like, too. More deeply, they encourage us to see that life and death aren’t opposed to one another: dying is a part of life. After all, we’re still alive when we’re dying so how we die impacts how we live.

The Ethics Centre was invited to make a submission to the NSW Parliamentary Group on Assisted Dying regarding a draft bill the parliament will debate soon. The questions we raised were in the spirit of connecting the good life to a good death.

Simon Longstaff, director of the Centre and author of the submission, writes, “It is not the role of The Ethics Centre to prescribe how people ought to decide and act. Our task is a more modest one – to set out some of the ethical considerations a person might wish to take into account when forming a view.”

Here are some of the key issues we explored, which are relevant to any discussion of assisted dying, not just the NSW Bill.

Does a good life involve suffering?

The most common justification for assisted dying or euthanasia is to alleviate unbearable suffering. This is based in a fairly universal sentiment. Longstaff writes, “To our knowledge, there is no religion, philosophical tradition or culture that prizes suffering … as an intrinsic good”.

Good things can come as a result of suffering. For example, you might develop perseverance or be supported by family. But the suffering itself is still bad. This, Longstaff argues, means “suffering is generally an evil to be avoided”.

There are two things to keep in mind here.

First, not all pain is suffering. Suffering is a product of the way we interpret ourselves and the world around us. Whether pain causes suffering depends on our response: It’s a subjective experience. Nobody but the sufferer can really determine the extent of their suffering. Recognising this could suggest a patient’s self-determination is crucial to decisions around assisted dying.

Second, just because suffering is generally a bad thing doesn’t mean that anything aiming to avoid it is good. We can agree that the goal of reducing suffering is probably good but still need to interrogate whether the method we’ve chosen to reduce suffering is itself ethical.

The connection between a good death and a good life

There’s not always a solution to suffering, no matter what anecdote you try, whether it be medicine, psychology, religion or philosophy. Sometimes suffering stays a while.

When there is no avenue to alleviate someone’s pain and anguish, Longstaff suggests “life can be experienced … as nothing more than an unrelenting and extra-ordinary burden”.

This is the context in which we should consider whether to help someone to end their lives or not. Although many faiths and beliefs affirm the importance and sacredness of life, if we’re thinking about a good, meaningful life, we need to pay some attention to whether life is actually of any value to the person living it. As Longstaff writes, “To say that life has value regardless of the conditions of a person’s existence may justify the continuation or glorification of lives that could be best described as a ‘living hell’”.

He continues, “To cause such a state would be indefensible. To allow it to persist without available relief is to act without mercy or compassion. To set aside those virtues is to deny what is best in our form of being.”

A responsible person should have autonomy over their death

Most people think it’s important for adults to be held responsible for their actions. Philosophers think this is a product of autonomy – the ability for people to determine the course of their own actions and lives.

Some philosophers think autonomy has an intrinsic connection to dignity. What makes humans special is their ability to make free choices and decisions. What’s more, we usually think it’s wrong to do things that undermine the free, autonomous choices of another person.

If we see death as a part of life, not distinct from it, it seems like we should allow – even expect – people to be responsible for their deaths. As Longstaff writes, “since dying is a part of life, the choices people make about the manner of their dying are central considerations in taking full responsibility for their lives”.

The role of the terminal disease

Some proposed laws, like the draft NSW Bill, suggest a person can seek to end their own life when their terminal disease causes them unbearable suffering. So, if you’re dying of lung cancer, you can only end your life if the cancer itself is causing you unbearable pain. It is necessary to consider if assisted dying be restricted in this way.

Imagine you’ve got a month to live and the only thing that gives you meaning is your ability to go outside and watch the sunrise. One day, you break your leg and are bedridden. Should you now be forced to live for a month in a state you find agonising and meaningless because your broken leg isn’t what’s killing you?

Longstaff argues, “If severe pain and suffering are essential criteria for being eligible for assistance, then on the basis that like cases should be treated in a like manner, assistance should be offered to a person who meets all the other specified criteria – even if their pain and suffering is not caused by their illness”.

Who is eligible for assisted dying?

Many laws try to carve out special categories of people who are and aren’t eligible to request assisted dying. They might do so on the basis of life expectancy, whether the illness is terminal or the age of the patient.

In determining who should be eligible, two principles are worth thinking about.

First, the principle of just access to medical care. Most bioethicists agree before we can figure out who receives medical treatment, we need to have a broader idea of what justice looks like.

Some think justice means people get what they need. For these people, granting medical care is based on how urgently it’s required. Others think justice means getting the best outcome. These people think we should distribute medicine in a way that creates the most quality of life for patients.

Depending on how we view justice, we’ll have different views on who is eligible for assisted dying. Is it those whose quality of life is lowest? If so, it might not be terminal cases in need of treatment. Is it those who are most in need of treatment? This might include young children who many people are reluctant to provide assisted dying to. Until we’re clear on this principle, it’ll be hard to decide who is eligible and who is not.

The second principle worth thinking about is to treat like cases alike. This idea comes from the legal philosopher HLA Hart. He thought it was essential for ethical and legal distinctions to be made on the basis of good reasons, not arbitrary measures. A good example is if two people committed the same crime, they should receive the same penalty. The only reason for not treating them the same is if there is relevant difference in the two cases.

This is important to think about in terms of strict eligibility criteria. Let’s say we reserve assisted dying for people over 25 years old, which the NSW draft Bill does. Hart would encourage us to wonder, as Longstaff noted in The Ethics Centre’s submission, “what ethically significant difference lies between a 24-year-old with six months to live and who wishes to receive assisted dying and a 25-year-old in the same condition?”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships