Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 29 MAR 2016

The problem of dirty hands refers to situations where a person is asked to violate their deepest held ethical principles for the sake of some greater good.

The problem of dirty hands is usually seen only as an issue for political leaders. Ordinary people are typically not responsible for serious enough decisions to justify getting their hands ‘dirty’. Imagine a political leader who refuses to do what is necessary to advance the common good – what would we think of them?

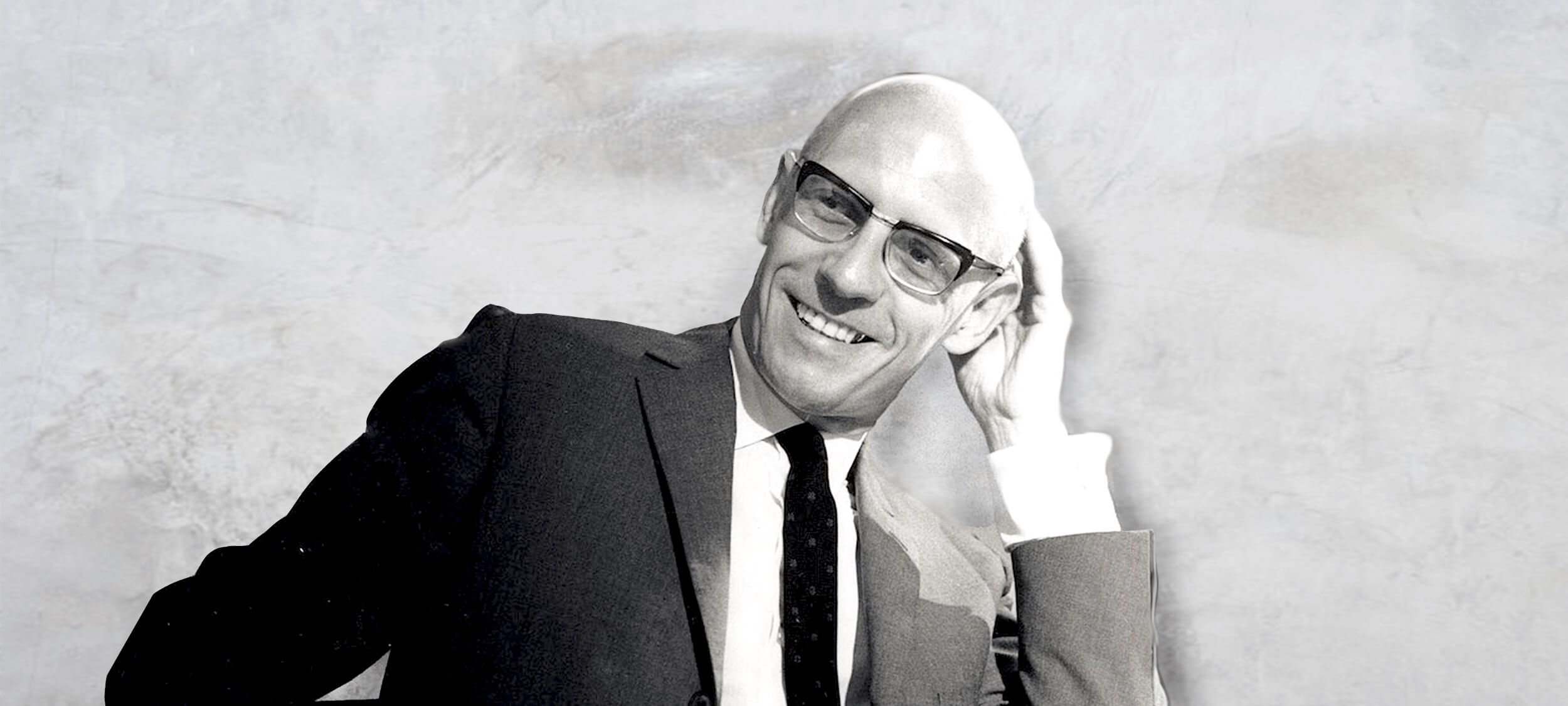

Michael Walzer steps in

This was the question philosopher Michael Walzer asked when he discussed dirty hands, and another philosopher, Max Weber, had asked before him.

Walzer asks us to imagine a politician who is elected in a country that has been devastated by civil war, and who campaigned on policies of peace, reconciliation and an opposition to torture. Immediately after this politician is elected, he is asked to authorise the torture of a terrorist. The terrorist has hidden bombs throughout apartments in the city which will explode in the next 24 hours. Should the politician authorise the torture in the hope the information provided by the terrorist might save lives?

Finding common ground

This is a pretty common ethical dilemma, and different ethical theories will give different answers. Deontologists will mostly refuse, taking the ‘absolutist’ position that torture is an attack on human dignity and therefore always wrong. Utilitarians will probably see the torture as the action leading to the best outcomes and argue it is the right course of action.

What makes dirty hands different is it treats each of these arguments seriously. It accepts torture might always be wrong, but also that the stakes are so high it might also be the right thing to do. So, the political leader might have a duty to do the wrong thing – but what they are required to do is still wrong. As Walzer says, “The notion of dirty hands derives from an effort to refuse ‘absolutism’ without denying the reality of the moral dilemma”.

The paradox of dirty hands – that the right thing to do is also wrong – poses a challenge to political leaders. Are they willing to accept the possibility they might have to get their hands dirty and be held responsible for it? Walzer believes the moral politician is one who has dirty hands, acknowledges it, and is destroyed by it (because of feelings of guilt, punishment and so on): “it is by his dirty hands that we know him”.

Note that we’re not talking about corruption here where politicians get their hands dirty for their own selfish reasons, like fraudulent reelection or profit. What we’re talking about is when a politician might be obliged to violate their deepest personal values or the ethical creeds of their community in order to achieve some higher good, and how the politician should feel about having done so.

A remorseful politician?

Walzer believes politicians should feel wracked with guilt and seek forgiveness (and even demand punishment) in response to having dirtied their hands. Other thinkers disagree, notably Niccolo Machiavelli. He was also aware political leaders would sometimes have to do ‘what’s necessary’ for the public good. But even if those actions would be rejected by private ethics, he didn’t think decision makers should feel guilty about it.

Machiavelli felt indecision, hesitation, or squeamishness in the face of doing what’s necessary wasn’t a sign of a good or virtuous political leader – it was a sign they weren’t cut out for the job. Under this notion, the good political leader won’t just accept getting their hands dirty, they’ll do it whenever necessary without batting an eyelid.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How avoiding shadow values can help change your organisational culture

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAR 2016

Warning – general plot spoilers to follow.

Collateral damage

Eye in the Sky begins as a joint British and US surveillance operation against known terrorists in Nairobi. During the operation, it becomes clear a terrorist attack is imminent, so the goals shift from surveillance to seek and destroy.

Moments before firing on the compound, drone pilots Steve Watts (Aaron Paul) and Carrie Gershon (Phoebe Fox) see a young girl setting up a bread stand near the target. Is her life acceptable collateral damage if her death saves many more people?

In military ethics, the question of collateral damage is a central point of discussion. The principle of ‘non-combatant immunity’ requires no civilian be intentionally targeted, but it doesn’t follow from this that all civilian casualties are unethical.

Most scholars and some Eye in the Sky characters, such as Colonel Katherine Powell (Helen Mirren), accept even foreseeable casualties can be justified under certain conditions – for instance, if the attack is necessary, the military benefits outweigh the negative side effects and all reasonable measures have been taken to avoid civilian casualties.

Risk-free warfare

The military and ethical advantages of drone strikes are obvious. By operating remotely, we prevent the risk of our military men and women being physically harmed. Drone strikes are also becoming increasingly precise and surveillance resources mean collateral damage can be minimised.

However, the damage radius of a missile strike drastically exceeds most infantry weapons – meaning the tools used by drones are often less discriminate than soldiers on the ground carrying rifles. If collateral damage is only justified when reasonable measures have been taken to reduce the risk to civilians, is drone warfare morally justified, or does it simply shift the risk away from our war fighters to the civilian population? The key question here is what counts as a reasonable measure – how much are we permitted to reduce the risk to our own troops?

Eye in the Sky forces us to confront the ethical complexity of war.

Reducing risk can also have consequences for the morale of soldiers. Christian Enemark, for example, suggests that drone warfare marks “the end of courage”. He wonders in what sense we can call drone pilots ‘warriors’ at all.

The risk-free nature of a drone strike means that he or she requires none of the courage that for millennia has distinguished the warrior from all other kinds of killers.

How then should drone operators be regarded? Are these grounded aviators merely technicians of death, at best deserving only admiration for their competent application of technical skills? If not, by what measure can they be reasonably compared to warriors?

Moral costs of killing

Throughout the film, military commanders Catherine Powell and Frank Benson (Alan Rickman) make a compelling consequentialist argument for killing the terrorists despite the fact it will kill the innocent girl. The suicide bombers, if allowed to escape, are likely to kill dozens of innocent people. If the cost of stopping them is one life, the ‘moral maths’ seems to check out.

Ultimately it is the pilot, Steve Watts, who has to take the shot. If he fires, it is by his hand a girl will die. This knowledge carries a serious ethical and psychological toll, even if he thinks it was the right thing to do.

There is evidence suggesting drone pilots suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other forms of trauma at the same rates as pilots of manned aircraft. This can arise even if they haven’t killed any civilians. Drone pilots not only kill their targets, they observe them for weeks beforehand, coming to know their targets’ habits, families and communities. This means they humanise their targets in a way many manned pilots do not – and this too has psychological implications.

Who is responsible?

Modern military ethics insist all warriors have a moral obligation to refuse illegal or unethical orders. This sits in contrast to older approaches, by which soldiers had an absolute duty to obey. St Augustine, an early writer on the ethics of war, called soldiers “swords in the hand” of their commanders.

In a sense, drone pilots are treated in the same way. In Eye in the Sky, a huge number of senior decision-makers debate whether or not to take the shot. However, as Powell laments, “no one wants to take responsibility for pulling the trigger”. Who is responsible? The pilot who has to press the button? The highest authority in the ‘kill chain’? Or the terrorists for putting everyone in this position to begin with?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

HSC exams matter – but not for the reasons you think

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Jane Hunt The Ethics Centre 14 MAR 2016

During the last year, I have listened and talked with practitioners, policy makers, adoptees, adoptive parents, children and young people in care, and birth families.

I have heard of the best and worst of human beings. My heart has constricted hearing about the profound harm some have experienced, and it has swelled in joy at the love that human beings can have for each other.

Research shows unequivocally that multiple placements have a negative impact on children.

Adoption in Australia has become fraught in all aspects – politics, policy and practice. It is a complex social issue that presents ethical and moral dilemmas for Government, the NGOs working with vulnerable and at-risk children, and for the broader community. It is complex and nuanced, with no clear response that will work in all cases. And it is highly emotionally charged.

In Australia, there are more than 43,000 children in ‘out of home care’. These children are identified as being ‘at risk’ and cannot remain in the care of their biological parents. They have been removed by child protection practitioners and, depending on the child’s circumstances, have been placed in the care of extended family, or with a guardian, or in short-term foster care.

Once children have been removed, the efforts of the child protection workers and other support services are framed to support the birth parents and to help them to reunify with their children. And this is where one of many ethical dilemmas emerges for the practitioners, policy makers and legislators.

How many opportunities should biological parents be given to demonstrate they are able keep their children safe and parent them? What level of support and services should they receive? And in the meantime, how long should a child stay in temporary care? How many placements is it tolerable for a child to experience?

These are difficult decisions for practitioners to make – each child’s situation is different. One practitioner described weighing up whether to return a child to their birth family against the risk of harm to the child as one of his hardest challenges. Having worked overseas, he believed that in Australia, the scales have tipped toward ‘restoration’ with birth families at all costs. This is not appropriately counter-balanced with an assessment of the risk of harm to children in the process.

Adoption in Australia has become fraught in all aspects – politics, policy and practice.

Compounding the situation is the problem of the availability and quality of foster carers able to care for vulnerable children. One practitioner in a regional town told me of a situation where she had to make a decision not to remove a child from a harmful situation because they did not have an appropriate foster carer available. The fact the child remained in an abusive family environment weighed heavily on the practitioner’s conscience.

Adoption, child protection and out of home care policy and legislation are founded on the assumption that decisions must be made in the ‘best interests of the child’. There is, however, no universally agreed upon definition of what this means.

Foster care is, by nature, temporary. There is always the possibility for the child that their relationship with their carers will end. This means some children experience multiple placements in foster care.

Sometimes the reasons for a change of placement are compelling – to be nearer their school, with siblings or nearer extended family members. However, research shows unequivocally that multiple placements have a negative impact on children.

Lack of security and attachment can have profound impacts on development. I’ve been told that multiple moves teach children that adults ‘come and go’ and cannot be trusted – a view corroborated by some young people in foster care who report feeling they ‘don’t belong’ anywhere.

Even the ‘Permanent Care Orders’ preferred in Victoria, which enable a child to live with a family until they are 18, fall short of providing a child or young person with the psychological and legal security of a family forever.

Why in Australia do we continue to provide a system that fails to meet children’s long term needs?

At the heart of this discussion lies a paralysing ethical dilemma – when a decision needs to be made to remove a child from their biological parents due to harm, neglect or abuse or when it’s not been successful, whose rights should be protected?

The right of the parent to keep their children, or the rights of the children to the conditions that will help them feel safe, secure and loved? Whose pain takes precedence? The parents’ loss and grief or the child’s trauma and pain?

The trauma caused by the historical practices of forced and closed adoptions has made many practitioners and politicians highly attuned to the needs of birth families. We need to learn from the profound hurt and trauma inflicted on many women who were coerced into relinquishing their children.

Adoption is not a panacea – it won’t be in the best interest of every child in long-term care.

The voices of adult adoptees who experienced secrecy, stigma and shame around their adoptions are deserving of understanding and compassion.

But considering or advocating for children to have access to adoption does not deny or ignore these experiences. It is important to learn from the impact of past practices and develop open adoption practices ensuring transparency and honesty for all involved, and provide support services that assist all parties involved in adoption.

It is also important to recognise that attempting to deal with an historical wrong – forced adoption – by loading the policy scales against adoption, creates a situation where everyone loses.

Adoption is not a panacea – it won’t be in the best interest of every child in long-term care, but it should be an option considered for all children that need permanent loving families. This then allows a decision to be made that is child focused and in their best interest.

There are many policy makers, practitioners, legislators, and families trying to acknowledge and navigate the ethical complexities of child protection, foster care and adoption. It is critical we continue in this direction, without being subsumed by the shame of our cultural past, to put the needs of vulnerable and at risk children first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The Ethics of Online Dating

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Georgie Bright The Ethics Centre 23 FEB 2016

On February 8, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced the appointment of Philip Ruddock – the former immigration minister who presided over the Howard government’s notorious “Pacific Solution” to divert asylum seekers from its shores – as Australia’s first special envoy for human rights.

This surprising recycling of Ruddock is part of the government’s campaign for a seat at the United Nations Human Rights Council for the 2018-2020 term.

Not too long ago, then Prime Minister Tony Abbott said Australia was “sick of being lectured to” by the United Nations. But even the new government is demonstrating a willingness to dismiss inconvenient human rights obligations. In Human Rights Watch’s annual World Report – which documents human rights practices in more than 90 countries – Australia’s human rights record over the last year showed how far the country has to go.

It is difficult not to be disillusioned by the state of human rights in Australia. This is especially the case regarding the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers, and the discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians.

Australia’s candidacy for a seat at the Human Rights Council provides an important opportunity for Australia to address its domestic human rights issues.

Australia’s position on refugee protection has been to undermine and ignore international standards rather than uphold them. The country maintains a harsh boat turn-back policy, returning migrants and asylum seekers to countries including Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam after only the most cursory of screenings.

Australia has a policy of mandatory detention for all unauthorised arrivals, transferring migrants and asylum seekers to offshore processing sites in less-equipped countries such as Nauru and Papua New Guinea. An independent review and a report by the Australian Human Rights Commission found evidence of sexual and physical abuse of children on Nauru.

Instead of trying to ensure the safety of the asylum seekers and refugees in Australian immigration detention facilities, the government acted to limit public discussion of important refugee and migrant issues. It passed a law that makes it a crime punishable by two years jail if immigration service providers disclose “protected information”.

Following a ruling by the High Court, 267 asylum seekers in Australia, including 91 children, faced involuntary transfer to Nauru and Manus Island. The High Court ruled on narrow statutory grounds and did not consider Australia’s compliance with international refugee law.

Another area where Australia is falling behind is Indigenous rights. In November 2015, Australia appeared before the UN Human Rights Council to defend its rights record as part of the Universal Periodic Review process. Many countries urged Australia to address disadvantage and discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians. The government’s “Closing the Gap” report for 2016 highlighted mixed progress in meeting targets in education and health, with Indigenous Australians still living on average 10 years less than non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians remain disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system, with Aboriginal women being the fastest growing prisoner demographic. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under the age of 18 are overrepresented in youth detention facilities—representing more than half of child detainees.

Australia’s candidacy for a seat at the Human Rights Council provides an important opportunity for Australia to address its domestic human rights issues.

Australia is a vibrant democracy with a multicultural society and a solid history of protecting and promoting human rights values. Following the horror of World War II, Australia played an integral role in the development of the United Nations. In 1948, Australia’s Dr Herbert Vere Evatt, as president of the General Assembly, oversaw the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

But to regain the moral high ground and respect international law, Australia should urgently address these and other shortcomings in its human rights record. For starters, the government should stop transferring migrants and asylum seekers offshore, and provide them with fair and timely refugee status determination in Australia.

On Indigenous rights, it needs to intensify its commitment to addressing the underlying causes of gaps in opportunities and outcomes in health, education, housing and employment between Indigenous and non-indigenous and do more to address the high incarceration rate.

Australia once was an international human rights leader – and should be again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Doing good for the right reasons: AMP Capital’s ethical foundations

BY Georgie Bright

Georgie Bright is the Australia Associate Director for Development and Outreach at Human Rights Watch. Prior to joining Human Rights Watch, she worked in criminal law at Legal Aid Queensland. Georgie holds a law degree from Queensland University of Technology and obtained her Masters in International Human Rights Law at the University of York.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Deontology

Deontology is an ethical theory that says actions are good or bad according to a clear set of rules.

Its name comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. Actions that align with these rules are ethical, while actions that don’t aren’t. This ethical theory is most closely associated with German philosopher, Immanuel Kant.

His work on personhood is an example of deontology in practice. Kant believed the ability to use reason was what defined a person.

From an ethical perspective, personhood creates a range of rights and obligations because every person has inherent dignity – something that is fundamental to and is held in equal measure by each and every person.

This dignity creates an ethical ‘line in the sand’ that prevents us from acting in certain ways either toward other people or toward ourselves (because we have dignity as well). Most importantly, Kant argues that we may never treat a person merely as a means to an end (never just as a resource or instrument).

Kant’s ethics isn’t the only example of deontology. Any system involving a clear set of rules is a form of deontology, which is why some people call it a “rule-based ethic”. The Ten Commandments is an example, as is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Most deontologists say there are two different kinds of ethical duties, perfect duties and imperfect duties. A perfect duty is inflexible. “Do not kill innocent people” is an example of a perfect duty. You can’t obey it a little bit – either you kill innocent people or you don’t. There’s no middle-ground.

Imperfect duties do allow for some middle ground. “Learn about the world around you” is an imperfect duty because we can all spend different amounts of time on education and each be fulfilling our obligation. How much we commit to imperfect duties is up to us.

Our reason for doing the right thing (which Kant called a maxim) is also important.

We should do our duty for no other reason than because it’s the right thing to do.

Obeying the rules for self-interest, because it will lead to better consequences or even because it makes us happy is not, for deontologists, an ethical reason for acting. We should be motivated by our respect for the moral law itself.

Deontologists require us to follow universal rules we give to ourselves. These rules must be in accordance with reason – in particular, they must be logically consistent and not give rise to contradictions.

It’s worth mentioning that deontology is often seen as being strongly opposed to consequentialism. This is because in emphasising the intention to act in accordance with our duties, deontology believes the consequences of our actions have no ethical relevance at all – a similar sentiment to that captured in the phrase “Let justice be done, though the heavens may fall”.

The appeal of deontology lies in its consistency. By applying ethical duties to all people in all situations the theory is readily applied to most practical situations. By focussing on a person’s intentions, it also places ethics entirely within our control – we can’t always control or predict the outcomes of our actions, but we are in complete control of our intentions.

Others criticise deontology for being inflexible. By ignoring what’s at stake in terms of consequences, some say it misses a serious element of ethical decision-making. De-emphasising consequences has other implications too – can it make us guilty of ‘crimes of omission’? Kant, for example, argued it would be unethical to lie about the location of our friend, even to a person trying to murder them! For many, this seems intuitively false.

One way of resolving this problem is through an idea called threshold deontology, which argues we should always obey the rules unless in an emergency situation, at which point we should revert to a consequentialist approach.

But is this a cop-out? How do we define ‘emergency’?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY ethics

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 25 JAN 2016

Stan Grant’s speech broke your heart – five views on what to do about it.

1) Tanya Denning-Orman say’s It’s not hard to capitalise on Grant’s momentum.

Last year Stan Grant delivered an address that left a crowd of hundreds speechless. This week, those same words jumped out of computer screens and into the hands of ordinary Australians and polarised millions of lounge room commentators. When this happened, he forced an entire nation to confront a history that no one wants to talk about.

He made you uncomfortable because he put a human face to the stats and figures that so commonly define First Nations peoples. Stan reminded you that we are people of law, lore, music, art and politics, and he inspired you to reimagine who we all are as Australians.

Yesterday, commentators described the impact of this speech as a “Martin Luther King moment”. Today, those of us who live it know that it’s all come and gone before. Noel Pearson delivered a speech that commentators said would be spoken about for years. In the months that followed, there was silence. With just a few words Charlie Perkins could mobilise crowds to take to the streets. Is it that easy to forget?

Knowing this, tomorrow the challenge will be that this momentum, created by a Wiradjuri man, doesn’t drown in a sea of barbecues and beers that is ‘Australia Day’. Just as Stan Grant said, we are better than this.

This time let the power of the word inspire you to make a change beyond ‘a thumbs up’ on a post and clicking the share button. We can insist that schools teach Australia’s silenced history. We can hold our governments to account. We can be empowered by our shared story.

Never before have we been so connected – we can create a global movement through our fingertips.

And I’ll let you in on a little secret. It’s not that hard to do.

Tanya Denning-Orman is the Channel Manager for NITV. Follow her on Twitter @Tanyadenning.

2) Luke Pearson argues that sentiment isn’t social justice. Now is the time to do something

The worry with making white people ‘feel all the feels’ as we sometimes say online, is that it won’t lead to any change in thought, behaviour or actual contributions to the work that needs to be done. Worse, it can actually do the opposite.

White people’s emotional experiences are all too often used to validate privilege and identify themselves as ‘one of the good ones’. This shifts the responsibility to act away from them and onto ‘those other people’.

Novelist Teju Cole labelled this phenomenon the ‘White Saviour Industrial Complex’, saying “The White Saviour Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege.”

This response gives people the moral authority to continue to justify racist responses that make them feel good about their privilege and direct and indirect contributions to racism and oppression. This attitude is what all too often justifies brutal government responses to complex problems.

In Australia this takes the form of punitive approaches to an endless list of humanitarian issues. The NT Intervention, offshore detention, military action overseas, Aboriginal deaths in custody, and increased rates of Indigenous child removal and incarceration whilst simultaneously defunding strategies to reduce these numbers…

This attitude leads people to get upset or feel attacked whenever white privilege is mentioned. They remove themselves from any responsibility purely by virtue of their emotional experiences, not recognising they are the ones who benefit most from their emotional experiences.

The very same people who claim to be our biggest supporters still argue that “we need to stop talking about race” rather than arguing “we need to stop racism”. They say “we are all Australians” without seeing the irony – erasing the identity of others was the outcome intended by culture genocide and assimilationist ideals. They feel betrayed when this is challenged because they feel they are owed for the emotional experiences they have felt.

If your response to videos like Stan Grant’s speech is to pat yourself on the back for a job well done without actually considering your place in the status quo and whether or not your ideas are just rebranded versions of the racism people have been fighting against for centuries, you are a part of the problem.

The same goes if you recognise the above but don’t actually do anything to change things. If you sit silently when you see racism within your own family, your workplace, your social group… If you don’t support those who work at the coalface, addressing the ongoing impacts of colonialism or who work at the highest levels trying to prevent it from continuing…

You are part of the problem.

“I deeply respect American sentimentality, the way one respects a wounded hippo. You must keep an eye on it, for you know it is deadly”, writes Teju Cole.

Ditto for Australia.

Luke Pearson is the Founder of IndigenousX, indigenousx.com.au. Follow them on Twitter @IndigenousX.

3) Anita Heiss anticipates that the real power of Stan’s speech is yet to come

As part of the debate, Stan Grant’s words were powerful. They were honest. They came from the heart and they were passionate. Unfortunately, for many of us they were not something new. They were words we had said ourselves in vain, similar to words we had heard from our parents and our peers. And so, we watched and sat in pain yet again at the reality of what is our great Australian nightmare.

For me the importance of Stan’s speech is that it has managed to reach a global audience. It has been heard by some who, for whatever reason, knew nothing about the facts Stan, a strong Wiradjuri man, was sharing as part of a debate that, in all honesty, was not much of a debate.

Words can be powerful. They can make us change the way we think. They can help us understand and feel empathy, but what are words without actions? I think the real power will come now, post Stan’s speech in a call to action to all those tweeting and facebooking to actually do something!

Teachers, watch the entire debate with your students. Get them to discuss, debate and talk about the issues raised. Parents, do the above also!

Corporates, politicians, policy makers, what are you doing in your worlds to address the inequities Stan mentioned? Immortality rates, incarceration rates, the ongoing removal of children?

Re-tweeting is not enough! You cannot claim to want equality for Indigenous Australians if you are not prepared to participate in the change – the actions – required to make that happen.

Build partnerships with Indigenous organisations that are already working in the areas you have influence in. Form lasting strategies to create the change this country needs. But please know, it’s not going to be easy, or going to be fixed overnight. Over 200 years of damage needs to be repaired to make the nightmare a dream.

Dr Anita Heiss is a proud member of the Wiradjuri nation. She is an author and Manager of the Epic Good Foundation. Follow her on Twitter @AnitaHeiss.

4) Kelly Briggs feels that we’ve had ‘Stan Grant moments’ before

I am confounded that some are comparing Stan Grant’s much admired speech from the IQ2 debate last year on Australia’s racism to Martin Luther King. Doing so erases Aboriginal activists who have come before us, including Dr Charlie Perkins.

Perkins headed what is now known as the ‘Freedom Rides’ – a busload of Sydney University students who toured particularly racist northern New South Wales towns to shine a spotlight on the heinous racism and segregation between blacks and whites in 1965. His passionate activism in towns, pubs, RSLs, swimming pools and the like saw changes to many rules and regulations.

Now that Stan Grant’s speech has gone ‘viral’, will it engender any changes to current governmental policies? Put back any of the money ripped out of the budget allocated to Aboriginal programs and issues? Create a much needed conversation about Australia’s ongoing overt and casual racism?

I don’t think it will. Stan Grant, while passionate, has not added anything new to what Aboriginal people have been saying in blogs, news articles and on social media for the better part of a decade. So, while I admire Stan’s stance, I do not hold out any hope that it will not be forgotten in a week, or that it will make a difference.

Kelly Briggs blogs at thekooriwoman.wordpress.com. Follow her on Twitter @TheKooriWoman.

5) Siv Parker on why we haven’t done this before

We haven’t had enough feel-good moments cast around Aboriginal Australia for this nation to be in a position to waste one. So where to from here?

An icebreaker may help to shake off a few nerves. It would be easier on all of us if we took a breath and agreed that we haven’t done this before.

Bridge walks, town meetings, community events, the apology and the land help to give us all our bearings.

But a digital world makes it easier to satisfy a yearning for substance, to extend ourselves beyond fleeting online interactions.

The anticipated referendum around constitutional reform is a hook on which to hang our shared history. I have no doubt we can agree to include Indigenous Australians in the constitution. I am not the only one willing to make a start on talking about what that could look like.

We won’t need to invoke great moments from foreign countries to define us, we can create our own. Indigenous people are on the crest of a wave in asserting ourselves in words, art, performances and knowledge systems that has been decades in the making. This nation can do better. That is the promise within our ancient storytelling tradition. A story is not a one-sided affair. We don’t listen to a story, we become a part of it. In years to come, they will continue to tell stories that includes us all.

Siv Parker is an award-winning writer and blogger. Follow her on Twitter @SivParker.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Rethinking the way we give

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Feminist porn stars debunked

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Laura McNally The Ethics Centre 9 DEC 2015

So-called feminist porn star James Deen has faced shocking accusations of rape from numerous women, including several female porn actors.

If true, it’s crucial Deen and men like him are held to account. But it’s also vital that porn producers, wholesalers, web hosts, and investors are not given a free pass. The porn industry deserves critique for feigning interest in respectful consensual sex while creating and profiting from its opposite – and doing so under the banner of feminism and ethics.

The porn industry is starting to brand itself as educational and ethical. The likes of Playboy are dedicating column inches to feminism, porn sites are handing out college scholarships and entire genres of porn are being dedicated to feminism.

“Feminist porn” is frequently cited as a solution, despite its limited popularity. Should it give us hope for a future of ethical porn? Recent events suggest not.

Deen’s ex-partner Stoya says he coerced her and pinned her down despite her pleas to stop. Her claims were followed by those of several other women alleging Deen had punched, injured, assaulted or anally raped them either on or off set. According to one:

He starts going crazy … extreme, brutally … He just starts shoving things in to the point where he ripped it [her rectum] and I bled everywhere. There was so much blood I couldn’t finish the scene.

Deen brands himself “a guy who bangs chicks for a living”. He features in numerous titles such as Teenaged Whores 5 and Triple Penetrated in Brutal Gangbang. Deen frequently appears on rough sex sites. He is also viewed as a “male feminist” by supporters.

But the accusations paint a different picture – of dangerous, misogynist ideals that hardly seem out of place in the thinly veiled “ethical” porn industry.

The popular notion that porn is mere fantasy with no link to real-world behaviour is challenged by the suggestion some of Deen’s ‘frape’ (fantasy rape) scenes may have been genuine rape on film. Moreover, it is alleged many of the porn crew were aware these acts were rape and congratulated Deen for getting anal scenes when they hadn’t been consented to.

These rape accusations make it clear pornography is not mere fantasy. Some may be footage of sexual violence and it has real negative effects for producers and consumers.

Yet, those harms are frequently denied. Such was the case when the ABC aired Australians on Porn. A Gold Coast Sexual Assault Centre Director was quoted on porn’s link to sexual violence:

“The biggest common denominator of the increase of intimate partner rape of women between 14 and 80 is the consumption of porn by the offender … We have seen a huge increase in deprivation of liberty, physical injuries, torture, drugging, sharing photos and film without consent and deprivation of liberty.”

This evidence was dismissed as “irrelevant” by some on the panel – the majority of whom were porn users and supporters. Porn, they suggested, isn’t to blame for negatively shaping behaviours. Rather, it opens minds and provides new ideas for the bedroom.

This argument sharply contrasts with police views and consistent research regarding the harmful effects of pornography. Studies backed by numerous meta-analysis show attitudes toward gender equality, sexual aggression and rape acceptance are worse for viewers of pornography.

The question is not whether a man can be feminist and a porn actor, but why an industry that promotes sexual violence and rape porn is regarded as ethical at all.

Young women are increasingly at risk. Forty percent of UK teenage girls report experiencing coerced sex acts and 25 percent report pressure to send pornographic texts. The ABC’s panel failed to include any person who could speak to the effect of porn in normalising harassing behaviours, sexual coercion, non-consensual filming or sexual violence. Nor did the panel give a flicker of thought to those harmed in production, or the girls, women and men who have quit on account of physical or emotional injury due to trends toward rough sex, choking and facial abuse.

After dismissing concerns about porn, the panel swiftly refocused on the positive effects of ethical and feminist porn before cutting to air a porn scene.

The ABC panel exemplified the dismissal of social harms with tokenistic stories of good. Those invested in porn are not unique from other industries in derailing critical dialogue with a perfunctory nod toward ethics.

These cynical displays of ethics are also used to gain greater political reach. Porn as sex education was recommended by some among the panel. James Deen regularly penned sex advice columns for mainstream feminist publications.

The question is not whether a man can be feminist and a porn actor, but why an industry that promotes sexual violence and rape porn is regarded as ethical at all. What of the ethical considerations stemming from the millions masturbating to scenes of sexual violence on film?

An industry that contributes to and profits from rape culture is an unlikely ally for gender equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

BY Laura McNally

Laura McNally is a psychologist, author and PhD candidate researching the political implications of corporate social responsibility. She is the chair of the Australian branch of Endangered Bodies.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Nurses and naked photos

Nurses and naked photos

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 6 NOV 2015

A Sydney nurse took an explicit photo of a schoolteacher who was under anaesthetic and awaiting surgery.

The teacher said, “I am a larger woman. To me, it’s obvious she took it to make fun of fat people.” The teacher is campaigning for legal reform to protect other patients from suffering in similar ways and to see the nurse punished for a criminal offence.

Obviously what this nurse did was wrong. It objectified another human being, treating her as an object of ridicule and subject to the whimsical mood of the nurse. What’s more, the nurse violated the contract of trust that underpins the relationship between patients and the medical profession.

By photographing her naked the nurse also subjected the teacher to deep and ongoing humiliation about her body and usually private sexual organs. The photograph also creates the possibility for further exploitation, distribution, and humiliation.

The teacher said, “I felt like my world was exploding. I felt I was in great peril that this photo was going to destroy my life, my career and that my son would find out.” It seems the psychological ramifications have been severe.

The act was intrinsically wrong. It violated notions of trust, the inherent dignity with which people ought to be treated, and undermined the values that inform the profession of nursing.

But independently of the consequences, the act was intrinsically wrong. It violated notions of trust, the inherent dignity with which people ought to be treated, and undermined the values that inform the profession of nursing.

It will be distressing to learn that there is currently no law in NSW forbidding behaviour like this. A loophole in the law means that because the photo was not motivated by sexual deviancy, but by the desire to make fun of the patient, no legal recourse was available. It seems reasonable to call for legal reform. This is precisely what Fiona McLay, the teacher’s lawyer, is doing.

The act was incontrovertibly unethical regardless of its legal standing and yet this nurse still felt empowered to take the photo. And worse, the nurse is still practising without restrictions or supervision, having apologised and found to have shown “the appropriate level of contrition”.

Despite all this, the instinct to turn to law as a way to amend or prevent unethical behaviour is misguided. What is required is for the nursing profession to demonstrate this behaviour will not be tolerated and is directly against the values nursing stands for.

Making such photographs illegal will do little to return trust – patients will still be vulnerable before surgery occurs and nurses will still have the opportunity to take such photos. Making photographs illegal will do little more than allow wrongdoers to be sent to prison.

Law is a clumsy instrument for enforcing ethical behaviour.

For us to trust nurses in spite of a story like this the profession must uniformly state their disapproval for the conduct and demonstrate willingness to enforce its own ethical standards. Law is a clumsy instrument for enforcing ethical behaviour. Re-committing as a profession and as individual professionals to the core values of the field – trust, respect for persons and patient care – is much more likely to avoid instances like this in the future.

There is no reason to excuse the nurse’s behaviour in this case. However, it is worth understanding this incident occurred in a context where crass jokes may well be the norm.

Jokes help us get through the day and although this one went seriously awry we should recognise the context in which it was made. Nursing is a tough field. It’s demanding on the body and the mind, and sometimes errors of judgement – including insensitive, invasive jokes – are a possibility.

As the old saying goes, sometimes you have to laugh to keep from crying.

Humour is a matter of taste, and much relies on pushing against ordinary modes of thinking – including moral norms. Of late there has been heated debate regarding the place and value of racist and sexist humour in comedy. Regardless of the view we take on that particular subject, we should agree that any form of humour that trades off the humiliation of a particular individual, or is done in ways that can have lasting and severe consequences for a person’s wellbeing will be unethical – even if funny to some.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2015

The New York Times Magazine polled its readers. “If you could go back and kill Hitler as a baby, would you do it?” 42% of people said yes.

Why they decided to ask the question is a mystery, but it sparked a meme that’s been bouncing around the internet ever since. The meme reached its zenith when Huffington Post asked Jeb Bush whether he would do the deed.

“Hell yeah, I would,” he declared. “You gotta step up, man.” Bush acknowledged the inherent fragility of time travel – as explored by scholars Marty McFly and Doc Brown, but ultimately conceded, “I’d do it. I mean, Hitler…”

Before you saddle up behind Jeb on the time travel express to Hitler’s nursery, here are a few things to consider.

Baby Hitler is innocent

Most ethical justifications for killing start with the presumption that people don’t deserve to be killed unless they’ve done something to forfeit their right to life. Depending on who you speak to, this might include being involved in an attack against somebody else, being in the military or even trafficking drugs.

Unless baby Hitler is running a Walter White-esque meth operation out of his preschool, he’s done nothing to forfeit his right to life.

Until he does – say, by orchestrating genocide – Hitler retains it. Killing him as a baby would therefore be wrong.

Acts of evil have personal costs

Knowingly doing the wrong thing – like killing an innocent baby – carries a personal cost. When we transgress against deep moral beliefs we can experience debilitating guilt, shame, anxiety and depression. Such actions can even come to define us permanently.

Some academics are now using the term ‘moral injury’ to describe the personal costs of acting against our moral beliefs. “Don’t kill innocent children” is arguably the most deeply held moral belief any of us have. Violating that norm comes at a severe price.

“Don’t kill innocent children” is arguably the most deeply-held moral belief any of us have. Violating that norm comes at a severe price.

Doing something wrong for the greater good doesn’t always work

German philosopher Immanuel Kant rejected the idea that ethics was just about “the greatest good for the greatest number” (a view known as consequentialism). Instead he argued that ethics was about doing what you are duty-bound to do – such as tell the truth and don’t kill.

He once considered the question of whether you could lie to save someone’s life. A murderer asks you for the location of a certain baby because he wants to murder him. Can you lie to save the baby’s life? Kant argued that you couldn’t – because you can’t guarantee that your lie will save the baby.

If you send the murderer to the bowling alley knowing the baby is upstairs, who’s to say the babysitter hasn’t taken the baby to the bowling alley without your knowledge? Suddenly you’ve told a lie and the baby is still dead, so you’ve made the situation worse overall.

In the case of Hitler, you would need to be certain his death would prevent the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust. If – as many historians contend – the rise of Nazism was a product of a range of social factors in Germany at the time, then killing a baby isn’t going to reverse those social factors. Butchering the babe might even allow for the rise of another power – equal to or worse than Hitler.

And you’ve still killed a baby.

Killing isn’t necessary

Some people argue that killing the innocent might be justified when it is the lesser evil. But even in that case it has to be absolutely necessary. If time travel is possible, it seems unlikely to be necessary to kill baby Hitler as opposed to, say, kidnapping him, adopting him out to a Jewish family or offering him a scholarship to the Vienna School of Fine Arts.

If time travel is possible, it seems unlikely to be necessary to kill baby Hitler.

Human lives are of immense, perhaps even infinite value. To take one – especially an innocent one – when it isn’t absolutely necessary is a serious ethical issue.

Dangerous precedent

Where do we draw the line? Once we’re done with Hitler which baby is on the block next? Pol Pot? Stalin? The guy who spoiled the end of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix for me in high school? We would require a set of consistent, universal ethical principles by which to determine which babies deserve death and which don’t.

Giving baby Hitler all of our murderous attention betrays our cognitive and personal bias – surely there are other worthy candidates? How many lives must a person take before their infant self is a legitimate target for killing? What standard will be applied?

For me, I wouldn’t do it. I mean, just look at baby Adolf…

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Hope

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why hard conversations matter

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Orphanage ‘voluntourism’ makes school students complicit in abuse

Orphanage ‘voluntourism’ makes school students complicit in abuse

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Karleen Gribble The Ethics Centre 23 OCT 2015

It’s great that Australian schools want to encourage their students to help others and gain perspective on their privilege. But visits to orphanages overseas are not the answer. To quote from the Friends International campaign, “Children are not tourist attractions”.

The first thing to understand is that orphanage life is damaging to children.

Children in orphanages are cared for as a group rather than as individuals. Life is regimented – each child has many different caregivers and little individual attention. Such care hurts children and may result in psychological damage and developmental delays.

Rates of physical and sexual abuse are also high in orphanages. The detrimental impact of institutional care closed all orphanages in Australia decades ago.

Short-term orphanage volunteers who play with and care for children are just adding to this harm. They increase the number of caregivers a child experiences and are just more people who abandon them.

Most children living in orphanages around the world have at least one living parent.

Visiting students may not see these harms. Necessity has forced children in orphanages to act cute to get scarce attention – something called “indiscriminate affection”. School students easily mistake this for genuine happiness. Some of those who run orphanages will also encourage children to be friendly to the visitors in the hope this will increase donations.

Donations are a big problem. In some cases “orphans” are actually created by unscrupulous organisations who pay families to hand over their children in order to collect visitor donations. In Cambodia, orphanage numbers have doubled during a time when the number of children without parents has declined.

Australian schools sometimes seek to improve conditions in orphanages by funding education or medical resources. This can also draw children into orphanages. It’s a dire state of affairs when a loving family sends their child away because an orphanage is the only option for their child to go to school or get medical care.

This is what happened in Aceh, Indonesia where 17 new orphanages were built for “tsunami orphans”. However, 98% of the children in these orphanages had families and had been placed there to gain an education.

Most children living in orphanages around the world have at least one living parent.

Child protection authorities in Australia would not allow school students to go into the homes of vulnerable children so that they could gain an understanding of their situation. Schools should not take advantage of lower standards in other places to give their students a good experience.

What I know from talking to those involved in orphanage volunteering is that they often believe what they are doing is somehow exempt from these problems. Is it possible for school orphanage volunteering trips to be OK? What might harm mitigation look like?

Due diligence may reduce the possibility of working with orphanages that are exploiting children for financial gain.

Schools should resource orphanages in a way that avoids drawing children away from their families. They can do this by making the education programs or medical care they fund equally available to poor children in the community.

Schools can ensure their students do not interact with children. This prevents the harm to children arising from having too many caregivers. Students can instead take on tasks that free up caregivers to spend more time with children, such as cooking, cleaning or maintenance work.

Child protection authorities in Australia would not allow school students to go into the homes of vulnerable children so they could gain an understanding of their situation.

When visiting the orphanages, school staff might educate their students about orphanages. They might talk about children having at least one parent who could care for them if given support.

Perhaps they could discuss the high rates of physical and sexual abuse within orphanages. Or explain child development principles and the importance of one-on-one care for young children. They can help their students understand why keeping children in families and out of orphanages is important.

Theoretically, it might be possible for schools to do all of these things but I am not aware of any school that has. In particular, not allowing students to interact with children removes what schools seem to consider an essential component of these trips.

Schools should develop sister-school relationships with overseas schools or even schools in disadvantaged communities in Australia. It’s great to see that some schools are already leading the way on this front.

Such arrangements foster understanding in a situation where there is more equality in the relationships and fewer pitfalls. If Australian schools are genuine about cross-cultural exchange, they shouldn’t be fostering last century’s model of child welfare.

Read Rev Dr Richard Umbers‘ counter-argument here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights