Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Aubrey Blanche 3 FEB 2026

It seems like everyone is using an AI notetaker these days. They’re a way for users to stay more present in meetings, keep better track of commitments and action items, and perform much better than most people’s memories. On the surface, they look like a simple example of AI living up the hype of improved efficiency and performance.

As an AI ethicist, I’ve watched more people I have meetings use AI notetakers, and it’s increasingly filled me with unease: it’s invited to more and more meetings (including when the user doesn’t actually attend) and I rarely encounter someone who has explicitly asked for my consent to use the tool to take notes.

However, as a busy executive with days full of context switching across a dizzying array of topics, I felt a lot of FOMO at the potential advantages of taking a load off so I could focus on higher-value tasks. It’s clear why people see utility in these tools, especially in an age where many of us are cognitively overloaded and spread too thin. But in our rush to offload some work, we don’t always stop to consider the best way to do it.

When a “low risk” use case isn’t

It might be easy to think that using AI for something as simple as taking notes isn’t ethically challenging. And if the argument is that it should be ethically low stakes, you’re probably right. But the reality is much different.

Taking notes with technology tangles the complex topics of consent, agency, and privacy. Because taking notes with AI requires recording, transcribing, and interpreting someone’s ideas, these issues come to the fore. To use these technologies ethically, everyone in each meeting should:

- Know that that they are being recorded

- Understand how their data will be used, stored, and/or transferred

- Have full confidence that opting out is acceptable.

The reality is that this shouldn’t be hard – but the economics of selling AI notetaking tools means that achieving these objectives isn’t as straightforward as download, open, record. This doesn’t mean that these tools can’t be used ethically, but it does mean that in order to do so we have to use them with intention.

What questions to ask:

What models are being used?

Not all AI is built the same, in terms of both technical performance and the safety practices that surround them. Most tools on the market use foundation models from frontier AI labs like Anthropic and OpenAI (which make Claude and ChatGPT, respectively), but some companies train and deploy their own custom models. These companies vary widely in the rigour of their safety practices. You can get a deeper understanding of how a given company or model approaches safety by seeking out the model cards for a given tool.

The particular risk you’re taking will depend on a combination of your use case and the safeguards put in place by the developer and deployer. For example, there’s significantly more risk of using these tools in conversations where sensitive or protected data is shared, and that risk is amplified by using tools that have weak or non-existent safety practices. Put simply, it’s a higher ethical risk (and potentially illegal) decision to use this technology when you’re dealing with sensitive or confidential information.

Does the tool train on user data?

AI “learns” by ingesting and identifying patterns in large amounts of data, and improves its performance over time by making this a continuous process. Companies have an economic incentive to train using your data – it’s a valuable resource they don’t have to pay for. But sharing your data with any provider exposes you and others to potential privacy violations and data leakages, and ultimately it means you lose control of your data. For example, research has shown that there are techniques that cause large language models (LLMs) to reproduce their training data, and AI creates other unique security vulnerabilities for which there aren’t easy solutions.

For most tools, the default setting is to train on user data. Often, tools will position this approach in terms of generosity, in that providing your data helps improve the service for yourself and others. While users who prioritise sharing over security may choose to keep the default, users that place a higher premium on data security should find this setting and turn it off. Whatever you choose, it’s critical to disclose this choice to those you’re recording.

How and where is the data stored and protected?

The process of transcribing and translating can happen on a local machine or in the “cloud” (which is really just a machine somewhere else connected to the internet). The majority will use a third-party cloud service provider, which expands the potential ethical risk surface.

First, does the tool run on infrastructure associated with a company you’re avoiding? For example, many people specifically avoid spending money on Amazon due to concerns about the ethics of their business operations. If this applies to you, you might consider prioritising tools that run locally, or on a provider that better aligns with your values.

Second, what security protocols does the tool provider have in place? Ideally, you’ll want to see that a company has standard certifications such as SOC 2, ISO 27001 and/or ISO 42001, which show an operational commitment to security, privacy, and safety.

Whatever you choose, this information should be a part of your disclosure to meeting attendees.

How am I achieving fully informed consent?

The gold standard for achieving fully informed consent is making the request explicit and opt in as a default. While first-generation notetakers were often included as an “attendee” in meetings, newer tools on the market often provide no way for everyone in the meeting to know that they’re being recorded. If the tool you use isn’t clearly visible or apparent to attendees, the ethical burden of both disclosure and consent gathering falls on you.

This issue isn’t just an ethical one – it’s often a legal one. Depending on where you and attendees are, you might need a persistent record that you’ve gotten affirmative consent to create even a temporary recording. For me, that means I start meeting with the following:

I wanted to let you know that I like to use an AI notetaker during meetings. Our data won’t be used for training, and the tool I use relies on OpenAI and Amazon Web Services. This helps me stay more present, but it’s absolutely fine if you’re not comfortable with this, in which case I’ll take notes by hand.

Doing this might feel a bit awkward or uncomfortable at first, but it’s the first step not only in acting ethically, but modelling that behaviour for others.

Where I landed

Ultimately, I decided that using an AI notetaker in specific circumstances was worth the risk involved for the work I do, but I set some guardrails for myself. I don’t use it for sensitive conversations (especially those involving emotional experiences) or those where confidential data is shared. I start conversations with my disclosure, and offer to share a copy of the notes for both transparency and accuracy.

But perhaps the broader lesson is that I can’t outsource ethics: the incentive structures of the companies producing these tools aren’t often aligned to the values I choose to operate with. But I believe that by normalising these practices, we can take advantage of the benefits of this transformative technology while managing the risks.

AI was used to review research for this piece and served as a constructive initial editor.

BY Aubrey Blanche

Aubrey Blanche is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of responsible business, finance, and technology, Blanche has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world. As Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, she leads our engagements with organisational partners looking to bring ethics to the centre of their operations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY Dia Bianca Lao 24 NOV 2025

“If a human worker does $50,000 worth of work in a factory, that income is taxed. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think we’d tax the robot at a similar level,” Bill Gates famously said. His call raises an urgent ethical question now facing Australia: When AI replaces human labour, who pays for the social cost?

As AI becomes a cheaper alternative to human labour, the question is no longer if it will dramatically reshape the workforce, but how quickly, and whether the nation’s labour market can adapt in time.

New technology always seems like the stuff of science fiction until its seamless transition from novelty to necessity. Today AI is past its infancy and is now shaping real-world industries. The simultaneous emergence of its diverse use cases and the maturing of automation technology underscores how rapidly it’s evolving, transforming this threat into reality sooner than we think.

Historically, automation tended to focus on routine physical tasks, but today’s frontier extends into cognitive domains. Unlike past innovations that still relied on human oversight, the autonomous nature of emerging technologies threatens to make human labour obsolete with its broader capabilities.

While history shows that technological revolutions have ultimately improved output, productivity, and wages in the long-term, the present wave may prove more disruptive than those before. In 2017, Bill Gates foresaw this looming paradigm shift and famously argued for companies to pay a ‘robot tax’ to moderate the pace at which AI impacts human jobs and help fund other employment types.

Without any formal measures, the costs of AI-driven displacement will likely mostly fall on workers and society, while companies reap the benefits with little accountability.

According to the World Economic Forum, while AI is predicted to create 69 million new jobs, 83 million existing jobs may be phased out by 2027, resulting in a net decrease of 14 million jobs or approximately 2% of current employment. They also projected that 23% of jobs globally will evolve in the next five years, driven by advancements in technology. While the full impact is not yet visible in official employment statistics, the shift toward reducing reliance on human labour through automation and AI is already underway, with entry-level roles and jobs involving logistics, manufacturing, admin, and customer service being the most impacted.

For example, Aurora’s self-driving trucks are officially making regular roundtrips on public roads delivering time- and temperature-sensitive freight in the U.S., while Meituan is making drone deliveries increasingly common in China’s major cities. We now live in a world where you can get your boba milk tea delivered by a drone in less than 20 minutes in places like Shenzhen. Meanwhile in Australia, Rio Tinto has also deployed fully autonomous trains and autonomous haul trucks across its Pilbara iron ore mines, increasing operational time and contributing to a 15% reduction in operating costs.

Companies have already begun recalibrating their workforce, and there is no stopping this train. In the past 12 months, CBA and Bankwest have cut hundreds of jobs across various departments despite rising profits. Forty-five of these roles were replaced by an AI chatbot handling customer queries, while the permanent closure of all Bankwest branches has seen the bank transition to a digital bank, with no intention of bringing back the lost positions. While some argue that redeployment opportunities exist or new jobs might emerge, details remain vague.

Is it possible to fully automate an economy and eliminate the need for jobs? Elon Musk certainly thinks so. It’s no wonder that a growing number of tech elite are investing heavily to replace human labour with AI. From copywriting to coding, AI has proven its versatility in speeding up productivity in all aspects of our lives. Its potential for accelerating innovation, improving living standards and economic growth is unparalleled, but at what cost?

What counts as good for the economy has historically benefited a select few, with technology frequently being a catalyst for this dynamic. For example, the benefits of the Industrial Revolution, including the creation of new industries and increased productivity, were initially concentrated in the hands of those who owned the machinery and capital, while the widespread benefits trickled down later. Without ethical frameworks in place, AI is positioned to compound this inequality.

Some proposals argue that if we make taxes on human labour cheaper while increasing taxes on AI machines and tools, this could encourage companies to view AI as complementary instead of a replacement for human workers. This levy could be a means for governments to distribute AI’s socioeconomic impacts more fairly, potentially funding retraining or income support for displaced workers.

If a robot tax is such a good idea, then why did the European Parliament reject it? Many argue that taxing productivity tools could hinder competitiveness. Without global coordination to implement this, if one country taxes AI and others don’t, it may create an uneven playing field and stifle innovation. How would policymakers even define how companies would qualify for this levy or measure how much to tax, when it’s hard to attribute profits derived from AI? Unlike human workers’ earnings, taxing AI isn’t as straightforward.

The challenge of developing policies that incentivise innovation while ensuring that its benefits and burdens are shared responsibly across society persists. The government’s focus on retraining and upskilling workers to help with this transition is a good start, but they cannot address all the challenges of automation fast enough. Relying solely on these programs risk overlooking structural inequities, such as the disproportionate impact on lower-income or older workers in certain industries, and long-term displacement, where entire job categories may vanish faster than workers can be retrained.

Our fiscal policies should adapt to the evolving economic landscape to help smooth this shift and fund social safety nets. A reduction in human labour’s share in production will significantly impact government revenue unless new measures of taxing capital are introduced.

While a blanket “robot tax” is impractical at this stage, incremental changes to existing taxation policies to target sectors that are most vulnerable to disruption is a possibility. Ideally, policies should distinguish the treatment between technologies that substitute for human labour, and those that complement them, to only disincentivise the former. While this distinction can be challenging, it offers a way to slow down job displacement, giving workers and welfare systems more time to adapt and generate revenue to help with the transition without hindering productivity.

As Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella warns, “With this empowerment comes greater human responsibility — all of us who build, deploy, and use AI have a collective obligation to do so responsibly and safely, so AI evolves in alignment with our social, cultural, and legal norms. We have to take the unintended consequences of any new technology along with all the benefits, and think about them simultaneously.”

The challenge in integrating AI more equitably into the economy is ensuring that its broad societal benefits are amplified, while reducing its unintended negative consequences. AI has the potential to fundamentally accelerate innovation for public good but only if progress is tied to equitable frameworks and its ethical adoption.

Australia already regulates specific harms of AI, protecting privacy and personal information through the Privacy Act 1988 and addressing bias through the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). These examples show that targeted regulation is possible. However, the next step should include ethical guardrails for AI-driven job displacement, such as exploring more equitable taxation, redistribution policies, and accountability frameworks before it’s too late. This transformation will require joint collaboration from governments, companies, and global organisations to collectively build a resilient and inclusive AI-powered future.

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future by Dia Bianca Lao is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ 2025 Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

BY Dia Bianca Lao

Dia Bianca Lao is a marketer by trade but a writer at heart, with a passion for exploring how ethics, communication, and culture shape society. Through writing, she seeks to make sense of complexity and spark thoughtful dialogue.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Bladerunner, Westworld and sexbot suffering

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

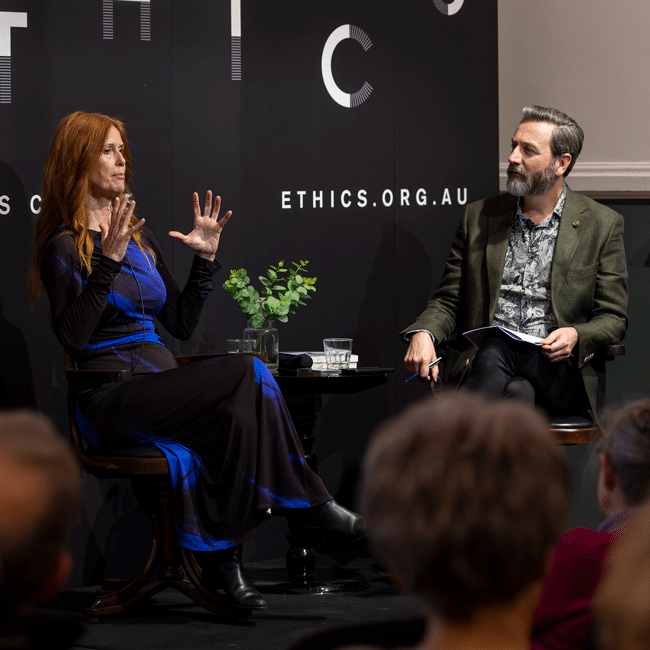

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 4 NOV 2025

We’re thrilled to introduce Aubrey Blanche, our new Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, who will lead our engagements with organisational partners looking to operate with the highest standards of ethical governance and leadership.

Aubrey is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of ethical business, finance, and technology, she has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world.

To better understand the work she’ll be doing with The Ethics Centre, we sat down with Aubrey to discuss her views on AI, corporate responsibility, and sustainability.

We’ve seen the proliferation of AI impact the way in which we work. What does responsible AI use look like to you – for both individuals and organisations?

I think that the first step to responsibility in AI is questioning whether we use it at all! While I believe it is and will be a transformative technology, there are major downsides I don’t think we talk about enough. We know that it’s not quite as effective as many people running frontier AI labs aim to make us believe, and it uses an incredible amount of natural resources for what can sometimes be mediocre returns.

Next, I think that to really achieve responsibility we need partnerships between the public and private sector. I think that we need to ensure that we’re applying existing regulation to this technology, whether that’s copyright law in the case of training, consumer protection in the case of chatbots interacting with children, or criminal prosecution regarding deepfake pornography. We also need business leaders to take ethics seriously, and to build safeguards into every stage from design to deployment. We need enterprises to refuse to buy from vendors that can’t show their investments in ensuring their products are safe.

And last, we need civil society to actively participate in incentivising those actors to behave in ways that are of benefit to all of society (not just shareholders or wealthy donors). That means voting for politicians that support policies that support collective wellbeing, boycotting companies complicit in harms, and having conversations within their communities about how these technologies can be used safely.

In a time where public trust is low in businesses, how can they operate fairly and responsibly?

I think the best way that businesses can build responsibility is to be more specific. I think people are tired of hearing “We’re committed to…”. There’s just been too much greenwashing, too much ethics washing, and too many “commitments” to diversity that haven’t been backed up by real investment or progress. The way through that is to define the specific objectives you have in relation to responsibility topics, publish your specific goals, and regularly report on your progress – even if it’s modest.

And most importantly, do this even when trust is low. In a time of disillusionment, you’ll need to have the moral courage to do the right thing even when there is less short-term “credit” for it.

How can we incentivise corporations to take responsible action on environmental issues?

I think that regulation can be a powerful motivator. I’m really excited that the Australian Accounting Standards Board is bringing new requirements into force that, at least for large companies, will force them to proactively manage climate risks and their impacts. While I don’t think it’s the whole answer, a regulatory “push” can be what’s needed for executives to see that actively thinking about climate in the context of their operations can be broadly beneficial to operations.

What are you most excited about sinking your teeth into at The Ethics Centre?

There’s so much to be excited about! But something that I’ve found wildly inspiring is working with our Young Ambassadors – early career professionals in banking and financial services who are working with us to develop their ethical leadership skills. While I have enjoyed working with our members – and have spent the last 15 years working with leaders in various areas of corporate responsibility – there nothing quite like the optimism you get when learning from people who care so much and who show us what future is possible.

Lastly – the big one, what does ethics mean to you?

A former boss of mine once told me that leadership is not about making the right choice when you have one: it’s about making the best choice you can when you have terrible ones and living with that choice. I think in many cases that’s what ethics is. It gives us a framework not to do the right thing when the answer is clear, but to align ourselves as closely as we can with our values and the greater good when our options are messy, complicated, or confusing.

Personally, I’ve spent a deep amount of time thinking about my values, and if I were forced to distill them down to two, I would wholeheartedly choose justice and compassion. I have found that when I consider choices through those frames, I both feel more like myself and like I’ve made choices that are a net good in the world. And I’ve been lucky enough to spend my career in roles where I got to live those values – that’s a privilege I don’t take for granted, and one of the reasons I’m so thrilled to be in this new role with The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Who are corporations willing to sacrifice in order to retain their reputation?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Love and the machine

When we think about love, we picture something inherently human. We envision a process that’s messy, vulnerable, and deeply rooted in our connection with others, fuelled by an insatiable desire to be understood and cared for. Yet today, love is being reshaped by technology in ways we never imagined before.

With the rise of apps such as Blush, Replika, and Character.AI, people are forming personal relationships with artificial intelligence. For some, this may sound absurd, even dystopian. But for others, it has become a source of comfort and intimacy.

What strikes me is how such behaviour is often treated as a fun novelty or dismissed as a symptom of loneliness, but this outlook can miss the deeper picture.

Many may misunderstand forming attachments with AI as another harmless, emerging trend, sweeping its profound ethical dimensions under the rug. In reality, this phenomenon forces us to rethink what love is and what humans require from relationships to flourish.

It is not difficult to see the appeal. AI companions offer endless patience, unconditional affirmations and availability at any hour, which human relationships struggle to live up to. Additionally, the World Health Organisation has declared loneliness a “global public health concern” with 1 in 6 people affected worldwide. Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Meta, framed AI therapy and companionship as remedies to our society’s growing modern disconnection. In recent surveys, 25% of young adults also believe that AI partners could potentially replace real-life romantic relationships.

One of the main ethical concerns is the commodification of connection and intimacy. Unlike human love, built from intrinsically valuable interactions, AI relationships are increasingly shaped by what sociologist George Ritzer calls McDonaldization: the pursuit of calculability, predictability, control, and efficiency. These apps are not designed to nurture a user’s social skills as many believe, but to keep consumers emotionally hooked.

Concerns of a dangerous slippery slope arise as intimacy becomes transactional. Chatbot apps often operate on subscription models where users can “unlock” more customisable or sexual features by paying a fee. By monetising upgrades for further affection, companies profit from users’ loneliness and vulnerability. What appears as love is in fact a business scheme that brings profit, ultimately benefiting large corporations instead of their everyday consumers.

In this sense, we notice one of humanity’s most cherished experiences being corporatised into a carefully packaged product.

Beyond commodification lies the insidious risk of emotional dependency and withdrawal from real-life interactions. Findings from OpenAI and the MIT Media Lab revealed that heavy users of ChatGPT, especially those engaging in emotionally intense conversations, tend to experience increased loneliness long-term and fewer offline social relationships. Dr Andrew Rogoyski of the Surrey Institute for People-Centred AI suggested we are “poking around with our basic emotional wiring with no idea of the long-term consequences.”

A Cornell University study also found that usage of voice-based chatbots initially mitigated loneliness. However, these benefits were reduced significantly with high usage rates, which correlated with higher isolation, increased emotional dependency, and reduced in-person engagement. While AI might temporarily cushion feelings of seclusion, a lasting overreliance seems to exacerbate it.

The misunderstanding further deepens as AI relationships are portrayed as private and inconsequential. What’s wrong with someone choosing to find comfort in an AI partner if it harms no one? However, this risks framing love as a personal preference rather than ongoing relational interactions that shape our character and community.

If we refer to the principles of virtue ethics, Aristotle’s idea of eudaimonia (a flourishing, well lived life) relies on developing virtues like empathy, patience, and forgiveness. Human connections promote personal growth, with their inevitable misunderstandings, disappointments, and the need to forgive. A chatbot like Blush has its responses built upon a Large Language Model to mirror inputs and infinitely affirm them. It may always say “the right thing,” but over time, this inhibits our character development.

It is still undeniably important to acknowledge the potential benefits of AI chatbots. For individuals who, due to physical or psychological reasons, are not in a position to form real world relationships, chatbots can provide an accessible stepping-stone to an emotional outlet. There’s no need to fear or avoid these platforms entirely, but we must reflect consciously upon their deeper ethical implications. Chatbots can supplement our relationships and offer support, but they should never be misunderstood as a replacement for genuine human love.

Decades from now, it might be common to ask whether your neighbour’s partner is human or AI. By then, the foundations of human connection would have shifted in irreversible ways. If love is indeed at the heart of what makes us human, we should at least realise that although programmed chatbots can say “I love you,” only human love teaches us what it truly means.

Love and the machine by Ariel Bai is the winning essay in our Young Writers’ 2025 Competition (13-17 age category). Find out more about the competition here.

BY Ariel Bai

Ariel is a year 10 student currently attending Ravenswood. Passionate about understanding people and the world around her, she enjoys exploring contemporary and social issues through her writing. Her interest in current global trends and human experiences prompted her to craft this piece.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 17 SEP 2025

As artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly accessible and integrated into our daily lives, what responsibilities do we bear when engaging with and designing this technology? Is it just a tool? Will it take our jobs? In The Ethics of AI, philosopher Dr Tim Dean and global ethicist and trailblazer in AI, Dr Catriona Wallace, sat down to explore the ethical challenges posed by this rapidly evolving technology and its costs on both a global and personal level.

Missed the session? No worries, we’ve got you covered. Here are 3 things we learnt from the event, The Ethics of AI:

We need to think about AI in a way we haven’t thought about other tools or technology

In 2023, The CEO of Google, Sundar Pichai described AI as more important than the invention of fire, claiming it even surpassed great leaps in technology such as electricity. Catriona takes this further, calling AI “a new species”, because “we don’t really know where it’s all going”.

So is AI just another tool, or an entirely new entity?

When AI is designed, it’s programmed with algorithms and fed with data. But as Catriona explains, AI begins to mirror users’ inputs and make autonomous decisions – often in ways even the original coders can’t fully explain.

Tim points out that we tend to think of technology instrumentally, as a value neutral tool at our disposal. But drawing from German philosopher Martin Heidegger, he reminds us that we’re already underthinking tools and what they can do – tools have affordances, they shape our environment and steer our behaviour. So “when we add in this idea of agency and intentionality” Tim says, “it’s no longer the fusion of you and the tool having intentionality – the tool itself might have its own intentions, goals and interests”.

AI will force us to reevaluate our relationship with work

The 2025 Future of Jobs Report from The World Economic Forum estimates that by 2030, AI will replace 92 million current jobs but 170 million new jobs will be created. While we’ve already seen this kind of displacement during technological revolutions, Catriona warns that the unemployed workers most likely won’t be retrained into the new roles.

“We’re looking at mass unemployment for front line entry-level positions which is a real problem.”

A universal basic income might be necessary to alleviate the effects of automation-driven unemployment.

So if we all were to receive a foundational payment, what does the world look like when we’re liberated from work? Since many of us tie our identity to our jobs and what we do, who are we if we find fulfilment in other types of meaning?

Tim explains, “work is often viewed as paid employment, and we know – particularly women – that not all work is paid, recognised or acknowledged. Anyone who has a hobby knows that some work can be deeply meaningful, particularly if you have no expectation of being paid”.

Catriona agrees, “done well, AI could free us from the tie to labour that we’ve had for so long, and allow a freedom for leisure, philosophy, art, creativity, supporting others, caring for loving, and connection to nature”.

Tech companies have a responsibility to embed human-centred values at their core

From harmful health advice to fabricating vital information, the implications of AI hallucinations have been widely reported.

The Responsible AI Index reveals a huge disconnect between businesses leaders’ understanding of AI ethics, with only 30% of organisations knowing how to implement ethical and responsible AI. Catriona explains this is a problem because “if we can’t create an AI agent or tool that is always going to make ethical recommendations, then when an AI tool makes a decision, there will always be somebody who’s held accountable”.

She points out that within organisations, executives, investors, and directors often don’t understand ethics deeply and pass decision making down to engineers and coders — who then have to draw the ethical lines. “It can’t just be a top-down approach; we have to be training everybody in the organisation.”

So what can businesses do?

AI must be carefully designed with purpose, developed to be ethical and regulated responsibly. The Ethics Centre’s Ethical by Design framework can guide the development of any kind of technology to ensure it conforms to essential ethical standards. This framework can be used by those developing AI, by governments to guide AI regulation, and by the general public as a benchmark to assess whether AI conforms to the ethical standards they have every right to expect.

The Ethics of AI can be streamed On Demand until 25 September, book your ticket here. For a deeper dive into AI, visit our range of articles here.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY Daniel Finlay 8 SEP 2025

My workplace is starting to implement AI usage in a lot of ways. I’ve heard so many mixed messages about how good or bad it is. I don’t know whether I should use it, or to what extent. What should I do?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is quickly becoming unavoidable in our daily lives. Google something, and you’ll be met with an “AI overview” before you’re able to read the first result. Open up almost any social media platform and you’ll be met with an AI chat bot or prompted to use their proprietary AI to help you write your message or create an image.

Unsurprisingly, this ubiquity has rapidly extended to the workplace. So, what do you do if AI tools are becoming the norm but you’re not sure how you feel about it? Maybe you’re part of the 36% of Australians who aren’t sure if the benefits of AI outweigh the harms. Luckily, there’s a few ethical frameworks to help guide your reasoning.

Outcomes

A lot of people care about what AI is going to do for them, or conversely how it will harm them or those they care about. Consequentialism is a framework that tells us to think about ethics in terms of outcomes – often the outcomes of our actions, but really there are lots of types of consequentialism.

Some tell us to care about the outcomes of rules we make, beliefs or attitudes we hold, habits we develop or preferences we have (or all of the above!). The common thread is the idea that we should base our ethics around trying to make good things happen.

This might seem simple enough, but ethics is rarely simple.

AI usage is having and is likely to have many different competing consequences, short and long-term, direct and indirect.

Say your workplace is starting to use AI tools. Maybe they’re using email and document summaries, or using AI to create images, or using ChatGPT like they would use Google. Should you follow suit?

If you look at the direct consequences, you might decide yes. Plenty of AI tools give you an edge in the workplace or give businesses a leg up over others. Being able to analyse data more quickly, get assistance writing a document or generate images out of thin air has a pretty big impact on our quality of life at work.

On the other hand, there are some potentially serious direct consequences of relying on AI too. Most public large language model (LLM) chatbots have had countless issues with hallucinations. This is the phenomenon where AI perceives patterns that cause it to confidently produce false or inaccurate information. Given how anthropomorphised chatbots are, which lends them an even higher degree of our confidence and trust, these hallucinations can be very damaging to people on both a personal and business level.

Indirect consequences need to be considered too. The exponential increase in AI use, particularly LLM generative AI like ChatGPT, threatens to undo the work of climate change solutions by more than doubling our electricity needs, increasing our water footprint, greenhouse gas emissions and putting unneeded pressure on the transition to renewable energy. This energy usage is predicted to double or triple again over the next few years.

How would you weigh up those consequences against the personal consequences for yourself or your work?

Rights and responsibilities

A different way of looking at things, that can often help us bridge the gap between comparing different sets of consequences, is deontology. This is an ethical framework that focuses on rights (ways we should be treated) and duties (ways we should treat others).

One of the major challenges that generative AI has brought to the fore is how to protect creative rights while still being able to innovate this technology on a large scale. AI isn’t capable of creating ‘new’ things in the same way that humans can use their personal experiences to shape their creations. Generative AI is ‘trained’ by giving the models access to trillions of data points. In the case of generative AI, these data points are real people’s writing, artwork, music, etc. OpenAI (creator of ChatGPT) has explicitly said that it would be impossible to create these tools without the access to and use of copyrighted material.

In 2023, the Writers Guild of America went on a five-month strike to secure better pay and protections against the exploitation of their material in AI model training and subsequent job replacement or pay decreases. In 2025, Anthropic settled for $1.5 billion in a lawsuit over their illegal piracy of over 500,000 books used to train their AI model.

Creative rights present a fundamental challenge to the ethics of using generative AI, especially at work. The ability to create imagery for free or at a very low cost with AI means businesses now have the choice to sidestep hiring or commissioning real artists – an especially fraught decision point if the imagery is being used with a profit motive, as it is arguably being made with the labour of hundreds or thousands of uncompensated artists.

What kind of person do you want to be?

Maybe you’re not in an office, though. Maybe your work is in a lab or field research, where AI tools are being used to do things like speed up the development of life-changing drugs or enable better climate change solutions.

Intuitively, these uses might feel more ethically salient, and a virtue ethics point of view could help make sense of that. Virtue ethics is about finding the valuable middle ground between extreme sets of characteristics – the virtues that a good person, or the best version of yourself, would embody.

On the one hand, it’s easy to see how this framework would encourage use of AI that helps others. A strong sense of purpose, altruism, compassion, care, justice – these are all virtues that can be lived out by using AI to make life-changing developments in science and medicine for the benefit of society.

On the other hand, generative AI puts another spanner in the works. There is an increasing body of research looking at the negative effects of generative AI on our ability to think critically. Overreliance and overconfidence in AI chatbots can lead to the erosion of critical thinking, problem solving and independent decision making skills. With this in mind, virtue ethics could also lead us to be wary of the way that we use particular kinds of AI, lest we become intellectually lazy or incompetent.

The devil in the detail

AI, in all its various capacities, is revolutionising the way we work and is clearly here to stay. Whether you opt in or not is hopefully still up to you in your workplace, but using a few different ethical frameworks, you can prioritise your values and principles and decide whether and what type of AI usage feels right to you and your purpose.

Whether you’re looking at the short and long-term impacts of frequent AI chatbot usage, the rights people have to their intellectual property, the good you can do with AI tools or the type of person you want to be, maintaining a level of critical reflection is integral to making your decision ethical.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Bladerunner, Westworld and sexbot suffering

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

AI and rediscovering our humanity

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 SEP 2025

With each passing day, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) bring us closer to a world of general automation.

In many cases, this will be the realisation of utopian dreams that stretch back millennia – imagined worlds, like the Garden of Eden, in which all of humanity’s needs are provided for without reliance on the ‘sweat of our brows’. Indeed, it was with the explicit hope that humans would recover our dominion over nature that, in 1620, Sir Francis Bacon published his Novum Organum. It was here that Bacon laid the foundations for modern science – the fountainhead of AI, robotics and a stack of related technologies that are set to revolutionise the way we live.

It is easy to underestimate the impact that AI will have on the way people will work and live in societies able to afford its services. Since the Industrial Revolution, there has been a tendency to make humans accommodate the demands of industry. In many cases, this has led to people being treated as just another ‘resource’ to be deployed in service of profitable enterprise – often regarded as little more than ‘cogs in the machine’. In turn, this has prompted an affirmation of the ‘dignity of labour’, the rise of Labor unions and with the extension of the voting franchise in liberal democracies, to legislation regulating working hours, standards of safety, etc. Even so, in an economy that relies on humans to provide the majority of labour required to drive a productive economy, too much work still exposes people to dirt, danger and mind-numbing drudgery.

We should celebrate the reassignment of such work to machines that cannot ‘suffer’ as we do. However, the economic drivers behind the widescale adoption of AI will not stop at alleviating human suffering arising out of burdensome employment. The pressing need for greater efficiency and effectiveness will also lead to a wholesale displacement of people from any task that can be done better by an expert system. Many of those tasks have been well-remunerated, ‘white collar’ jobs in professions and industries like banking, insurance, and so on. So, the change to come will probably have an even larger effect on the middle class rather than working class people. And that will be a very significant challenge to liberal democracies around the world.

Change to the extent I foresee, does not need to be a source of disquiet. With effective planning and broad community engagement, it should be possible to use increasingly powerful technologies in a constructive manner that is for the common good. However, to achieve this, I think we will need to rediscover what is unique about the human condition. That is, what is it that cannot be done by a machine – no matter how sophisticated? It is beyond the scope of this article to offer a comprehensive answer to this question. However, I can offer a starting point by way of an example.

As things stand today, AI can diagnose the presence of some cancers with a speed and effectiveness that exceeds anything that can be done by a human doctor. In fact, radiologists, pathologists, etc are amongst the earliest of those who will be made redundant by the application of expert systems. However, what AI cannot do replace a human when it comes to conveying to a patient news of an illness. This is because the consoling touch of a doctor has a special meaning due to the doctor knowing what it means to be mortal. A machine might be able to offer a convincing simulation of such understanding – but it cannot really know. That is because the machine inhabits a digital world whereas we humans are wholly analogue. No matter how close a digital approximation of the analogue might be, it is never complete. So, one obvious place where humans might retain their edge is in the area of personal care – where the performance of even an apparently routine function might take on special meaning precisely because another human has chosen to care. Something as simple as a touch, a smile, or the willingness to listen could be transformative.

Moving from the profound to the apparently trivial, more generally one can imagine a growing preference for things that bear the mark of their human maker. For example, such preferences are revealed in purchases of goods made by artisanal brewers, bakers, etc. Even the humble potato has been affected by this trend – as evidenced by the rise of the ‘hand-cut chip’.

In order to ‘unlock’ latent human potential, we may need to make a much sharper distinction between ‘work’ and ‘jobs’.

That is, there may be a considerable amount of work that people can do – even if there are very few opportunities to be employed in a job for that purpose. This is not an unfamiliar state of affairs. For many centuries, people (usually women) have performed the work of child-rearing without being employed to do so. Elders and artists, in diverse communities, have done the work of sustaining culture – without their doing so being part of a ‘job’ in any traditional sense. The need for a ‘job’ is not so that we can engage in meaningful work. Rather, jobs are needed primarily in order to earn the income we need to go about our lives.

And this gives rise to what may turn out to be the greatest challenge posed by the widescale adoption of AI. How, as a society, will we fund the work that only humans can do once the vast majority of jobs are being done by machines?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

We can raise children who think before they prompt

We can raise children who think before they prompt

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Emma Wilkins 26 AUG 2025

We may not be able to steer completely clear of AI, or we may not want to, but we can help our kids to understand what it is and isn’t good for, and make intentional decisions about when and how to use it.

ChatGPT and other artificial “help” is already so widely used that even parents and educators who worry about the ways it might interfere with children’s learning and development, seem to accept that it’s a tool their kids will have to learn to use.

In her forthcoming book The Human Edge, critical thinking specialist Bethan Winn says that because AI is already embedded in our world, the questions to ask now are around which human skills we need to preserve and strengthen, and where we draw the line between assistance and dependence.

By taking time to “play, experiment, test hypotheses, and explore”, Winn suggests we can equip our kids and ourselves with the tools to think critically. This will help us “adapt intelligently” and set our own boundaries, rather than defaulting lazily and unthinkingly to what “most people” seem okay with.

What we view as “good”, what decisions we make, and encourage, and discourage, our children to make, will depend on what we value. One of the reasons corporations and governments have been so quick to embrace AI is that they prize efficiency, productivity and profit; and fear falling behind. But in the private sphere, we can make different decisions based on different values.

If, for example, we value learning and creativity, the desire to build up skills and knowledge will help us to resist using AI to brainstorm and create on our behalf. We’ll need to help our kids to see that how they produce something can matter just as much as what they produce, because it’s natural to value success too. We’ll also need to make learning fun and satisfying, and discourage short-term wins over long-term gains.

Myself and my husband are quick to share cautionary tales – from the news, books, podcasts, our own experiences and those of our friends – about less than ideal uses of AI. He tells funny stories about the way candidates he interviews misuse it, I tell funny stories about how disastrously I’d misquote people if I relied on generated transcripts. I also talk about why I’m not tempted to rely on AI to write for me – I want to keep using my brain, developing my skills, choosing my sources; I want to arrive at understanding and insight, not generate it, even if that takes time and energy. (I also can’t imagine prompting would be nearly as fun).

Concern for the environment can also offer incentive to use our brains, or other less energy-intensive tools, before turning to AI. And if we value truth and accuracy, the reality that AI often presents information that’s false as fact will provide incentive to think twice before using it, or strong motivation to verify its claims when we do. Just because an “AI overview” is the first result in an internet search, doesn’t mean we can’t scroll past it to a reputable source. Tech companies encourage one habit, but we can choose to develop another.

And if we’ve developed a habit of keeping a clear conscience, and if we value honesty and integrity, we’ll find it easier to resist using AI to cheat, no matter how easy or “normal” it becomes. We’ll also be concerned by the unethical ways in which large language models have been trained using people’s intellectual property without their consent.

As our kids grow more independent, they might not retain the same values, or make the same decisions, as we do. But if they’ve formed a habit of using their values to guide their decisions, there’s a good chance they’ll continue it.

In addition to hoping my children adopt values that will make them wise, caring, loving, human beings, I hope they’ll understand their unique value, and the unique value all humans have. It’s the existential threat AI poses, when it seems to outperform us not only intellectually but relationally, that might be the most concerning one of all.

In a world where chatbots are designed to flatter, befriend, even seduce, we can’t assume the next generation will value human relationships – even human life and human rights – in the way previous generations did. Already, some prefer a chatbot’s company to that of their own friends and family.

Parents teaching their children about values is nothing new. Nor is contradicting our speech with our actions in ways our children are bound to notice. We know we should set the example we want our kids to follow, but how often do we fall short of our own standards? In our defense, we’re only human.

We’re “only” human. In other words, we’re not divine. And AI is neither human nor divine. Whether or not we agree that humans are made in the image of God – are “the work of his hands” – I hope we can agree that we’re more valuable than the work of our hands, no matter how incredible that work might be.

Of all the opportunities AI affords us and our children, the prompt to consider what it means to be human, to ask ourselves deep questions about who we are and why we’re here, may be the most exciting one of all.

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Daniel Finlay 19 AUG 2025

In early 2025, 60 female students from a Melbourne high school had fake, sexually explicit images of themselves shared around their school and community.

Less than a year prior, a teenage boy from another Melbourne high school created and spread fake nude photos of 50 female students and was let off with only a warning.

These fake photos are also known as deepfakes, a type of AI-augmented photo, video or audio that fabricates someone’s image. The harmful uses of this kind of technology are countless as the technology becomes more accessible and more convincing: porn without consent, financial loss through identity fraud, the harm to a political campaign or even democracy through political manipulation.

While these are significant harms, they also already exist without the aid of deepfakes. Deepfakes add something specific to the mix, something that isn’t necessarily being accounted for both in the reaction to and prevention of harm. This technology threatens our sense of autonomy and identity on a scale that’s difficult to match.

An existential threat

Autonomy is our ability to think and act authentically and in our best interests. Imagine a girl growing up with friends and family. As she gets older, she starts to wonder if she’s attracted to women as well as men, but she’s grown up in a very conservative family and around generally conservative people who aren’t approving of same-sex relations. The opinions of her family and friends have always surrounded her, so she’s developed conflicting beliefs and feelings, and her social environment is one where it’s difficult to find anyone to talk to about that conflict.

Many would say that in this situation, the girl’s autonomy is severely diminished because of her upbringing and social environment. She may have the freedom of choice, but her psychology has been shaped by so many external forces that it’s difficult to say she has a comprehensive ability to self-govern in a way that looks after her self-interests.

Deepfakes have the capacity to threaten our autonomy in a more direct way. They can discredit our own perceptions and experiences, making us question our memory and reality. If you’re confronted with a very convincing video of yourself doing something, it can be pretty hard to convince people it never happened – videos are often seen as undeniable evidence. And more frighteningly, it might be hard to convince yourself; maybe you just forgot…

Deepfakes make us fear losing control of who we are, how we’re perceived, what we’re understood to have said, done or felt.

Like a dog seeing itself in the mirror, we are not psychologically equipped to deal with them.

This is especially true when the deepfakes are pornographic, as is the case for the vast majority of deepfakes posted to the internet. Victims of these types of deepfakes are almost exclusively women and many have commented on the depth of the wrongness that’s felt when they’re confronted with these scenes:

“You feel so violated…I was sexually assaulted as a child, and it was the same feeling. Like, where you feel guilty, you feel dirty, you feel like, ‘what just happened?’ And it’s bizarre that it makes that resurface. I genuinely didn’t realise it would.”

Think of the way it feels to be misunderstood, to have your words or actions be completely misinterpreted, maybe having the exact opposite effect you intended. Now multiply that feeling by the possibility that the words and actions were never even your own, and yet are being comprehended as yours by everyone else. That is the helplessness that comes with losing our autonomy.

The courage to change the narrative

Legislation is often seen as the goal for major social issues, a goal that some relationships and sex education experts see as a major problem. The government is a slow beast. It was only in 2024 that the first ban on non-consensual visual deepfakes was enacted, and only in 2025 that this ban was extended to the creation, sharing or threatening of any sexually explicit deepfake material.

Advocates like Grace Tame have argued that outlawing the sharing of deepfake pornography isn’t enough: we need to outlaw the tools that create it. But these legal battles are complicated and slow. We need parallel education-focused campaigns to support the legal components.

One of the major underlying problems is a lack of respectful relationships and consent education. Almost 1 in 10 young people don’t think that deepfakes are harmful because they aren’t real and don’t cause physical harm. Perspective-taking skills are sorely needed. The ability to empathise, to fully put yourself in someone else’s shoes and make decisions based on respect for someone’s autonomy is the only thing that can stamp out the prevalence of disrespect and abuse.

On an individual level, making a change means speaking with our friends and family, people we trust or who trust us, about the negative effects of this technology to prevent misuse. That doesn’t mean a lecture, it means being genuinely curious about how the people you know use AI. And it means talking about why things are wrong.

We desperately need a culture, education and community change that puts empathy first. We need a social order that doesn’t just encourage but demands perspective taking, to undergird the slow reform of law. It can’t just be left to advocates to fight against the tide of unregulated technological abuse – we should all find the moral courage to play our role in shifting the dial.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Lucy Gill-Simmen 17 JUL 2025

French philosopher René Descartes crowned human reason in 1637 as the foundation of existence: Cogito, ergo sum – I think, therefore I am. For centuries, our capacity to doubt, question and think has been both our compass and our identity. But what does that mean in an age where machines can “think”, generate ideas, write novels, compose symphonies and, increasingly, make decisions?

Artificial intelligence (AI) has brought a new kind of certainty, one that is quick, data-driven and at times frighteningly precise, at times alarmingly wrong. From Google’s Gemini to OpenAI’s ChatGPT, we live in a world where answers can arrive before the question is even finished. AI has the potential to change not just how we work, but how we think. As our digital tools become more capable, we may well be justified in asking: where did the wonder go?

We have become increasingly accustomed to optimisation. From using apps to schedule our days to improving how companies hire staff through AI-powered recruitment tools, technology has delivered on its promise of speed and efficiency.

In education, students increasingly use AI to summarise readings and generate essay outlines; in healthcare, diagnostic models match human doctors in detecting disease.

But in our pursuit of optimisation, we may have left something essential behind. In her book The Power of Wonder, author Monica Parker describes wonder as a journey, a destination, a verb and a noun, a process and an outcome.

Lamenting how “modern life is conditioning wonder-proneness out of us”, Parker suggests we have “traded wonder for the pale facsimile of electronic novelty-seeking”. And there’s the paradox: AI gives us knowledge at scale, but may rob us of the humility and openness that spark genuine curiosity.

AI as the antidote?

But what if AI isn’t the killer of wonder, but its catalyst? The same technologies that predict our shopping habits or generate marketing content can also create surreal art, compose jazz music and tell stories in different ways.

Tools like DALL·E, Udio.ai, and Runway don’t just mimic human creativity, they expand our creative capacity by translating abstract ideas into visual or audio outputs instantly. They don’t just mimic creativity, they open it up to anyone, enabling new forms of self-expression and speculative thinking.

The same power that enables AI to open imaginative possibilities can also blur the line between fact and fiction, which is especially risky in education where critical thinking and truth-seeking are paramount. That’s why it’s essential that we teach students not just to use these tools, but to question them.

Teaching people to wonder isn’t about uncritical amazement – it’s about cultivating curiosity alongside discernment.

Educators experimenting with AI in the classroom are starting to see this potential, as my recent work in the area has shown. Rather than using AI merely to automate learning, we are using it to provoke questions and to promote creativity.

When students ask ChatGPT to write a poem in the voice of Virginia Woolf about climate change, they learn how to combine literary style with contemporary issues. They explore how AI mimics voice and meaning, then reflect on what works and what doesn’t.

When they use AI tools to build brand storytelling campaigns, they practise turning ideas into images, sounds and messages and learn how to shape stories that connect with audiences. Students are not just using AI, they’re learning to think critically and creatively with it.

This aligns with Brazilian philosopher Paulo Friere’s “banking” concept of education, where rather than depositing facts, educators are required to spark critical reflection. AI, when used creatively, can act as a dialogue partner, one that reflects back our assumptions, challenges our ideas and invites deeper inquiry.

The research is mixed, and much depends on how AI is used. Left unchecked, tools like ChatGPT can encourage shortcut thinking. When used purposely as a dialogue partner, prompting reflection, testing ideas and supporting creative inquiry, studies show it can foster deeper engagement and critical thinking. The challenge is designing learning experiences that make the most of this potential.

A new kind of curiosity

Wonder isn’t driven by novelty alone, it’s about questioning the familiar. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum describes wonder as “taking us out of ourselves and toward the other”. In this way, AI’s outputs have the potential to jolt people out of cognitive ruts and into new realms of thought, causing them to experience wonder.

It could be argued that AI becomes both mirror and muse. It holds up a reflection of our culture, biases and blind spots while nudging us toward the imaginative unknown at the same time. Much like the ancient role of the fool in King Lear’s court, it disrupts and delights, offering insights precisely because it doesn’t think like humans do.

This repositions AI not as a rival to human intelligence, but as a co-creator of wonder, a thought partner in the truest sense.

Descartes saw doubt as the path to certainty. Today, however, we crave certainty and often avoid doubt. In a world overwhelmed by information and polarisation, there is comfort in clean answers and predictive models. But perhaps what we need most is the courage to ask questions, to really wonder about things.

The German poet Rainer Maria Rilke once advised: “Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves.”

AI can generate perspectives, juxtapositions and “what if” scenarios that challenge students’ habitual ways of thinking. The point isn’t to replace critical thinking, but to spark it in new directions. When artists co-create with algorithms, what new aesthetics emerge that we’ve yet to imagine?

And when policymakers engage with AI trained on other perspectives from around the world, how might their understanding and decisions be transformed? As AI reshapes how we access, interpret and generate knowledge, this encourages rethinking not just what we learn, but why and how we value knowledge at all.

Educational philosophers such as John Dewey and Maxine Greene championed education that cultivates imagination, wonder and critical consciousness. Greene spoke of “wide-awakeness”, a state of being in the world.

Deployed thoughtfully, AI can be a tool for wide-awakeness. In practical terms, it means designing learning experiences where AI prompts curiosity, not shortcuts; where it’s used to question assumptions, explore alternatives, and deepen understanding.

When used in this way, I believe it can help students tell better stories, explore alternate futures and think across disciplines. This demands not only ethical design and critical digital literacy, bit also an openness to the unknown. It also demands that we, as humans, reclaim our appetite for awe.

In the end, the most human thing about AI might be the questions it forces us to ask. Not “What’s the answer?” but “What if …?” and in that space, somewhere in between certainty and curiosity, wonder returns. The machines we built to do our thinking for us might just help us rediscover it.

BY Lucy Gill-Simmen

Lucy Gill-Simmen is the Vice-Dean for Education and Student Experience and a Senior Lecturer in Marketing in the School of Business and Management at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology