Big tech's Trojan Horse to win your trust

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 26 MAY 2020

Technology has created bad trust habits in all of us. We shouldn’t be tricked into giving tech our trust, but that’s exactly what happens when everything is about making life easier.

During this lockdown period, I’ve been thinking a lot about the difference between states and habits. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, we’ve all learned what proper hand washing hygiene looks like, how to prevent the risk of spreading disease when we’re in public and what kinds of places to avoid.

For many of us, health used to be a state that we enjoyed without having to develop too many of the habits that help guarantee that health. We’ve had all the benefit without the effort. However, we’re now recognising that if we want the best chance of maintaining our health in a time of uncertainty, we need to be intentional about the habits and behaviours we develop.

I think it’s helpful to think about trust in the same way. For many people and organisations, being trusted is a state: we want to be in a situation where people have high confidence in us. What hasn’t always happened is to think about the intentional practices, behaviours and habits that are likely to secure trust in times of crisis.

This is particularly true for technology and tech companies, who have enjoyed a disproportionately high level of trust for a simple reason: they make our lives easier. The convenience we receive by interacting with technology means we’re likely to continue to engage with them, even when there are very good reasons not to.

Take Uber, for example. Uber is highly reliable and very convenient, which means people are willing to get into cars with complete strangers. Their behaviour indicates they trust the service, even if they say they don’t (surveys find that people find taxi drivers more trustworthy than Uber drivers). This kind of behavioural trust, born of convenience, holds even in situations where people have very good reasons not to ride.

In 2016, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Jason Dalton – an Uber driver – murdered six people whilst working his nightly Uber driving route. As news broke that there was a suspected murderer picking up rides via Uber, people continued to use the service. One rider who caught a ride with Dalton (thankfully, he wasn’t murdered) actually asked him ‘you’re not the one whose been driving around killing people, are you?’. Despite being aware there was a real threat to life, the convenience of a cheap ride home secured consumer trust in Uber.

Of course, it’s only trust of a certain kind. The trust we confer on convenient technology isn’t genuine trust – where we rationally, consciously believe that our interests align to the tech developers and that they want to take care of us. It’s implied trust; whether we believe the technology will deliver, we act as though it will.

This is the kind of trust we show in large tech platforms like Facebook. A 2018 YouGov survey commissioned by the Huffington Post found 66% of Facebook users have little to no trust in the platforms use of their data. Despite this, those users have given Facebook their data, and continue to do so, which is the kind of trust we provide when there’s something convenient on offer.

We cannot understate the significance that convenience plays as a trust lubricant. Trust expert Rachel Botsman, author of Who Can You Trust?, argues that “Money is the currency of transactions. Trust is the currency of interactions.” We need to add another layer to this: trust is the currency of conscious interactions, but convenience is the currency of the unthinking consumer (and we are all, at times, unthinking consumers).

This generates some real challenges for tech companies. It’s easy to use convenience to secure behavioural trust – to be in the ‘state’ of trust with customers – so that they’ll use your services, hand over data or spend their money, without developing the habits that generate rational, genuine trust. It’s easier to be trusted than to be trustworthy, but it might also be less valuable in the long run.

Moreover, the tendency to reward the convenience-seeking part of ourselves might generate problems with a very long tail. Some problems are not easily solved, nor is there an app to solve wealth inequality, climate change or discrimination. Many of our problems require a willingness to persevere; whilst technology can help, and might help resolve the symptoms of some of these issues, the underlying causes require rethinking our social, political and economic beliefs. Technology alone cannot get us there.

And yet, we continually look to technology as a solution for these woes. The Australian government’s first response to climate change after the 2020 bushfires was a large-scale investment in new climate technologies. Several people have released ‘consent apps’, aimed at preventing rape and false rape claims by having people sign a waiver to confirm they’ve consented to sex. There is no app to solve misogyny; no one technology that will fix our approach to the environment.

The reality is, trading on convenience can make us lazy – not just as individuals, but as a society. It’s bad for us. Moreover, it’s bad for business.

Although people often make decisions based on convenience, they pass judgements based on trust. This means they will often feel duped, exploited or betrayed, feeling ‘tricked’ into signing up to something just because it was convenient at the time.

This makes for a fickle customer and is an unreliable basis on which to build a business. Recognising this, a number of successful organisations are now seeking to build genuine trust. Salesforce CEO Mark Benioff recently stated, “trust has to be the highest value in your company, and if it’s not, something bad is going to happen to you.”

However, for people to trust you, they need to be able to slow down, think, form an ethical judgement. Today, one of the major goals of technology is to be frictionless. Hopefully by now you can see why that’s an unwise goal. If you want people to genuinely trust you, then you can’t give them a seamless experience. You need to create some friction.

Remember, convenience can be a lubricant. It might help you get people through the door more quickly, but it makes them slippery and hard to hold on to.

If you found this article interesting, download our paper, Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology for free to further explore ethical tech. Learn the principles you need to consider when designing ethical technology, how to balance the intentions of design and use, and the rules of thumb to prevent ethical missteps. Understand how to break down some of the biggest challenges and explore a new way of thinking for creating purpose-based design.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Are we ready for the world to come?

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 15 MAY 2020

We are on the cusp of civilisational change driven by powerful new technologies – most notably in the areas of biotech, robotics and expert AI. The days of mass employment are soon to be over.

While there will always be work for some – and that work is likely to be extremely satisfying – there are whole swathes of the current economy where it will make increasingly little sense to employ humans. Those affected range from miners to pathologists: a cross-section of ‘blue collar’ and ‘white collar’ workers, alike in their experience of displacement.

Some people think this is a far too pessimistic view of the future. They point to a long history of technological innovation that has always led to the creation of new and better jobs – albeit after a period of adjustment.

This time, I believe, will be different. In the past, machines only ever improved as a consequence of human innovation. Not so today. Machines are now able to acquire new skills at a rate that is far faster than any human being. They are developing the capacity for self-monitoring, self-repair and self-improvement. As such, they have a latent ability to expand their reach into new niches.

This doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Working twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week in environments that no human being could tolerate, machines may liberate the latent dreams of humanity to be free from drudgery, exploitation and danger.

However, society’s ability to harvest the benefits of these new technologies crucially depends on planning and managing a just and orderly transition. In particular, we need to ensure that the benefits and burdens of innovation are equitably distributed. Otherwise, all of the benefits of technological innovation could be lost to the complaints of those who feel marginalised or abandoned. On that, history offers some chilling lessons for those willing to learn – especially when those displaced include representatives of the middle class.

COVID-19 has given us a taste of what an unjust and disorderly transition could look like. In the earliest days of the ‘lockdown’ – before governments began to put in place stabilising policy settings such as the JobKeeper payment – we all witnessed the burgeoning lines of the unemployed and wondered if we might be next.

As the immediate crisis begins to ease, Australian governments have begun to think about how to get things back to normal. Their rhetoric focuses on a ‘business-led’ return to prosperity in which everyone returns to work and economic growth funds the repayment of debts accumulated during the the pandemic.

Attempting to recreate the past is a missed opportunity at best, and an act of folly at worst. After all, why recreate the settings of the past if a radically different future is just a few years away?

In these circumstances, let’s use the disruption caused by COVID-19 to spur deeper reflection, to reorganise our society for a future very different from the pre-pandemic past. Let’s learn from earlier societies in which meaning and identity were not linked to having a job.

What kind of social, political and economic arrangements will we need to manage in a world where basic goods and services are provided by machines? Is it time to consider introducing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) for all citizens? If so, how would this be paid for?

If taxes cannot be derived from the wages of employees, where will they be found? Should governments tax the means of production? Should they require business to pay for its use of the social and natural capital (the commons) that they consume in generating private profits?

These are just a few of the most obvious questions we need to explore. I do not propose to try to answer them here, but rather, prompt a deeper and wider debate than might otherwise occur.

Old certainties are being replaced with new possibilities. This is to be welcomed. However, I think that we are only contemplating the ‘tip’ of the policy iceberg when it comes to our future. COVID-19 has given us a glimpse of the world to come. Let’s not look away.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Bryan Mukandi The Ethics Centre 9 MAY 2020

In their recent article, ‘Who gets the ventilator in the coronavirus pandemic?’, bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Dominic Wilkinson note that we may soon be faced with a situation in which the demand for medical resources is greater than what is available.

At that point, decisions about who gets what medical resources ought to be just, they argue. The trouble with the article however, is that the two men seem to approach our present crisis as though it were just that, a present tense phenomenon. They view COVID-19 not as a something that has emerged over time as a result of our social configuration and political choices, but as something that appeared out of nowhere, an atemporal phenomenon.

Treating the pandemic as atemporal means that the two scholars only focus on the fact of this individual here and that one over there, suffering in this moment, from the same condition. They fail to ask how how this person came to be prone to the virus, or what resources that person has had at their disposal, let alone the socio-political and historical circumstances by which those resources were acquired. Karla Holloway, Professor of English and Professor of Law, makes the point that stripping away the textual details around our two patients simplifies the decision making process, but the price paid for that efficiency might be justice.

We know that there are systematic discrepancies in medical outcomes for marginalised groups at the best of times.We know that structural inequalities inform discrepancies around the degree to which people can practice social distancing and reduce the risk of infection. We know that those most likely to be most severely affected in the wake of the pandemic are those belonging to already marginalised communities. As public health medicine specialist, Papaarangi Reid, put it in a recent interview:

“We’ve got layers that we should be worried about. We should be worried about people who have difficulty accessing services … people who are stigmatised … While we are very worried about our elderly, we’re also worried about our precariat: those who are homeless; we’re worried about those who are impoverished; those who are the working poor; we’re worried about those who are in institutions, in prisons.”

Every time Reid says that we ought to worry about this group or that, I am confronted by Arendt’s take on just how difficult it is to think in that manner. I’m currently teaching a Clinical Ethics course for second year medical students, one of whose central pillars is Hannah Arendt’s understanding of thought. Standing on the other side of the catastrophe that was the second world war, she warned that thinking is incredibly difficult; so much so it demands that one stop, and it can be paralysing.

Arendt pointed out those algorithmic processes on the basis of which we usually navigate day-to-day life: clichés, conventional wisdom, the norms or ‘facts’ that seem so self-evident, we take them for granted. She argued that those are merely aids, prostheses if you like, which stand in the place of thinking – that labour of conceptually wading through a situation, or painstakingly kneading a problem. The trouble is, in times of emergency, where there is panic and a need for quick action, we are more likely to revert to our algorithms, and so reap the results of our un-interrogated and unresolved lapses and failures.

Australia today is a case in point. “The thing that I’m counting on, more than anything else,” noted Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently, “Is that Australians be Australian.” He went on to reiterate at the same press conference, “So long as Australians keep being Australians, we’ll get through this together.”

I’m almost sympathetic to this position. A looming disaster threatens the status quo, so the head of that status quo attempts to reassure the public of the durability of the prevailing order. What goes unexamined in that reflex, however, is the nature of the order. The prime minister did not stop to think what ‘Australia’ and ‘Australianness’ mean in more ordinary times.

Nor did he stop to consider recent protests by First Nations peoples, environmental activists, refugee and asylum seeker advocates and a raft of groups concerned about those harmed in the course of ‘Australians being Australian’. Instead, with the imperative to act decisively as his alibi, he propagated the assumption that whatever ‘Australia’ means, it ought to be maintained and protected. But what if that is merely the result of a failure to think adequately in this moment?

In his excellent article, calling on the nation to learn from past epidemics, Yuggera/Warangu ophthalmologist Kris Rallah-Baker, writes: ‘This is just the beginning of the crisis and we need to get through this together; Covid-19 has no regard for colour or creed’. In one sense, he seems to arrive at a position that is as atemporal as that of Savulescu and Wilkinson, with a similar stripping away of particularity (colour and creed). It’s an interesting position to come to given the continuity between post-invasion smallpox and COVID-19 that his previous paragraphs illustrate.

Read another way, I wonder if Rallah-Baker is provoking us; challenging us to think. What if this crisis is not the beginning, but the result of a longstanding socioeconomic, political and cultural disposition towards First Nations peoples, marginalised groups more broadly, and the prevailing approach to social organisation?

Could it then also be the case that the effect of the presence of novel coronavirus in the community is in fact predicated, to some degree, on social categories such as race and creed? Might a just approach to addressing the crisis, even in the hospital, therefore need to grapple with temporal and social questions?

There will be many for whom the days and weeks ahead will rightly be preoccupied with the practical tasks before them: driving trucks; stacking supermarket shelves; manufacturing protective gear; mopping and disinfecting surfaces; tending to the sick; ensuring the continuity of government services; and so forth. For the rest of us, there is an imperative to think. We ought to think deeply about how we got here and where we might go after this.

Perhaps then, as health humanities researchers Chelsea Bond and David Singh recently noted in the Medical Journal of Australia:

“we might also come to realise the limitations of drawing too heavily upon a medical response to what is effectively a political problem, enabling us to extend our strategies beyond affordable prescriptions for remedying individual illnesses to include remedying the power imbalances that cause the health inequalities we are so intent on describing.”

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Hope

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

BY Bryan Mukandi

is an academic philosopher with a medical background. He is currently an ARC DECRA Research Fellow working on Seeing the Black Child (DE210101089).

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to put a price on a life - explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

In all the time I’ve spent teaching ethics – from trolley problems to discussions of civilian casualties at war to the ethics of firefighting – there have been a few consistent trends in what matters to people.

One of the most common is that in life-and-death situations, details matter. People want to know exactly who might die or be rescued: how old are they? Are they healthy? Do they have children? What have they done with their life?

What they’re doing, whether they know it or not, is exploring what factors could help decide which life it would be most reasonable, or most ethical to save, relative to the other lives on the table.

Moreover, it’s not only in times of war or random thought experiments that these questions arise. Every decision about where to allocate health resources is likely to have life-or-death consequences. Allocate more funding to women’s shelters to address domestic violence and you’ll save lives. However, how many lives would you save if that same money were used to fund more hospital beds, or was invested into mental health support in rural communities?

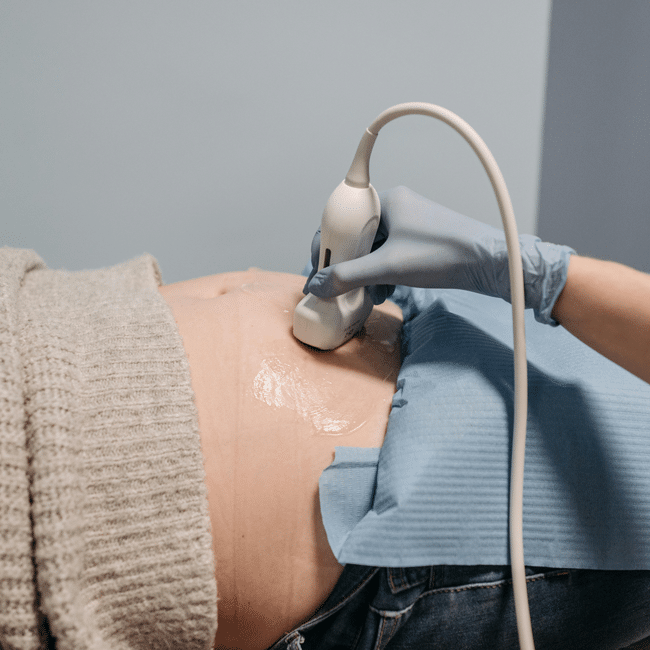

One widely-used method for ensuring health resources are allocated as efficiently as possible is to use QALY’s – quality-adjusted life years. QALY is an approach that was developed in the 1970’s to more precisely, consistently and objectively determine the effectiveness and efficiency of different health measures.

Here’s how it works: imagine a year of life enjoyed at full health. It gets assigned a score of 1. Every year of life lived at less than full health gets assigned a lower score. The worse off the person’s health, the lower the score.

For example, take someone who has to undergo chemotherapy for five years. They have full mobility, but have some difficulty with usual activities, severe pain and mild mental health challenges. They might be given a QALY score of 0.55.

Once we’ve gotten a QALY score, we then need to work out how much the healthcare costs. Then, it’s simple maths: multiply the cost by the QALY score and you get an idea of how much each QALY is costing you. Then you can compare the cost effectiveness of different health programs.

QALY’s are usually seen as a utilitarian method of allocating health resources – it’s about maximising the utility of the healthcare system as a whole. However, like most utilitarian approaches, what works best overall doesn’t work best in individual cases. And that’s where criticisms of QALY arise.

Let’s say two patients come in with the same condition – COVID-19. One of them is young, non-disabled and has no other health conditions affecting their quality of life. The other person is elderly, has a range of other health conditions and is in the early stages of dementia. Both patients have the same condition. However, according to the QALY approach, they are not necessarily entitled to the same level of care – for example, a ventilator if resources are scarce. The cost per QALY for the younger patient is far lower than for the elderly patient.

For this reason, QALY’s are sometimes seen as inherently unjust. They fail to provide all people with equal access to healthcare treatment. Moreover, as philosopher and medical doctor Bryan Mukandi argues, if two patients with the same condition are expected to have different health outcomes, there’s a chance that’s the result of historical injustices. Say, a person with type-2 diabetes receives a lower QALY score as a result, but type-2 diabetes is correlated with lower income, the scoring system might serve to entrench existing advantage and disadvantage.

Like any algorithmic approach to decision-making, QALYs present as neutral, mathematic and scientific. That’s why it’s important to remember, as Cathy O’Neil says in Weapons of Math Destruction, that algorithms are “opinions written in code.”

Embedded within QALY’s method are a range of assumption about what ‘full health’ is and what it is not. For instance, a variation on the QALY methodology call DALY – disability-adjusted life years – “explicitly presupposes that the lives of disabled people have less value than those of people without disabilities.”

An alternative to the QALY approach is to adopt what is known simply as a ‘needs-based’ approach. It’s sometimes described as a ‘first come, first served’ approach. It prioritises the ideal of healthcare justice above health efficiency – everyone deserves equal access to healthcare, so if you need treatment, you get treatment.

This means, to go back to our elderly and young patients with COVID-19, that whoever arrives at the hospital first and has a clinical need of a ventilator will get one. QALY advocates will argue that in times of scarcity, this is an inefficient approach that may border on immoral. After all, shouldn’t the younger person be given the same chance at life as the elderly person?

However, there is something radical underneath the needs-based approach. QALY’s starting point is that there are limited health resources, and therefore some people will have to miss out. A needs-based approach allows us to do something more radical: to demand that our healthcare is equipped, as much as possible, to respond to the demand. Rather than doing the best with what we have, we make sure we have what is necessary to do the best job.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The value of a human life

The value of a human life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

One of the most enduring points of tension during the COVID-19 pandemic has concerned whether the national ‘lockdown’ has done more harm than good.

This issue was squarely on the agenda during a recent edition of ABC TV’s Q+A. The most significant point of contention arose out of comments made by UNSW economist, Associate Professor Gigi Foster. Much of the public response was critical of Dr. Foster’s position – in part because people mistakenly concluded she was arguing that ‘economics’ should trump ‘compassion’.

That is not what Gigi Foster was arguing. Instead, she was trying to draw attention to the fact that the ‘lockdown’ was at risk of causing as much harm to people (including being a threat to their lives) as was the disease, COVID-19, itself.

In making her case, Dr. Foster invoked the idea of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). As she pointed out, this concept has been employed by health economists for many decades – most often in trying to decide what is the most efficient and effective allocation of limited funds for healthcare. In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

So, Gigi Foster was not lacking in compassion. Rather, I think she wanted to promote a debate based on the rational assessment of options based on calculation, rather than evaluation. In doing so, she drew attention to the costs (including significant mental health burdens) being borne by sections of the community who are less visible than the aged or infirm (those at highest risk of dying if infected by this coronavirus).

I would argue that there are two major problems with Gigi Foster’s argument. First, I think it is based on an understandable – but questionable – assumption that her way of thinking about such problems is either the only or the best approach. Second, I think that she has failed to spot a basic asymmetry in the two options she was wanting to weigh in the balance. I will outline both objections below.

In invoking the idea of QALYs, Foster’s argument begins with the proposition that, for the purpose of making policy decisions, human lives can be stripped of their individuality and instead, be defined in terms of standard units. In turn, this allows those units to be the objects of calculation. Although Gigi Foster did not explicitly say so, I am fairly certain that she starts from a position that ethical questions should be decided according to outcomes and that the best (most ethical) outcome is that which produces the greatest good (QALYs) for the greatest number.

Many people will agree with this approach – which is a limited example of the kind of Utilitarianism promoted by Bentham, the Mills, Peter Singer, etc. However, there will have been large sections of the Q+A audience who think this approach to be deeply unethical – on a number of levels. First, they would reject the idea that their aged or frail mother, father, etc. be treated as an expression of an undifferentiated unit of life. Second, they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

…they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

To do so, they might think, is to violate the ethical precept that every human being possesses an intrinsic dignity. Gigi Foster’s argument sits squarely in a tradition of thinking (calculative rationality) that stems from developments in philosophy in the late 16th and 17th Centuries. It is a form of thinking that is firmly attached to Enlightenment attempts to make sense of existence through the lens of reason – and which sought to end uncertainty through the understanding and control of all variables. It is this tendency that can be found echoing in terms like ‘human resources’.

Although few might express a concern about this in explicit terms, there is a growing rejection of the core idea – especially as its underlying logic is so closely linked to the development of machines (and other systems) that people fear will subordinate rather than serve humanity. This is an issue that Dr Matthew Beard and I have addressed in the broader arena of technological design in our publication, Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology.

The second problem with Dr. Foster’s position is that it failed to recognise a fundamental asymmetry between the risks, to life, posed by COVID-19 and the risks posed by the ‘lockdown’. In the case of the former: there is no cure, there is no vaccine, we do not even know if there is lasting immunity for those who survive infection.

We do not yet know why the disease kills more men than women, we do not know its rate of mutation – or its capacity to jump species, etc. In other words, there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

…there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

On the other hand, we have available to us a significant number of options for preventing or minimising the harms caused by the lockdown. For example, in advance of implementing the ‘lockdown’, governments could have anticipated the increased risks to mental health leading to a massive investment in its prevention and treatment.

Governments have the policy tools to ensure that there is intergenerational equity and that the burdens of the ‘lockdown’ do not fall disproportionately on the young while the benefits were enjoyed disproportionately by the elderly.

Governments could have ensured that every person in Australia received basic income support – if only in recognition of the fact that every person in Australia has had to play a role in bringing the disease under control. Is it just that all should bear the burden and only some receive relief – even when their needs are as great as others?

Whether or not governments will take up the options that address these issues is, of course, a different question. The point here is that the options are available – in a way that other options for controlling COVID-19 are not. That is the fundamental asymmetry mentioned above.

I think that Gigi Foster was correct to draw attention to the potential harm to life, etc. caused by the ‘lockdown’. However, she was mistaken not to explore the many options that could be taken up to prevent the harm she and many others foresee. Instead, she went straight to her argument about QALYs and allowed the impression to form that the old and the frail might be ‘sacrificed’ for the greater good.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Women’s pain in pregnancy and beyond is often minimised

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 5 DEC 2019

This article was written for, and first published by The Guardian. Republished with permission.

Once technology is released, it’s like herding cats. Why do we continue to let the tech sector manage its own mess?

We haven’t yet seen a clear frontrunner emerge as the Democratic candidate for the 2020 US election. But I’ve been interested in another race – the race to see which buzzword is going to be a pivotal issue in political reporting, hot takes and the general political introspection that elections bring. In 2016 it was “fake news”. “Deepfake” is shoring up as one of the leading candidates for 2020.

This week the US House of Representatives intelligence committee asked Facebook, Twitter and Google what they were planning to do to combat deepfakes in the 2020 election. And it’s a fair question. With a bit of work, deepfakes could be convincing and misleading enough to make fake news look like child’s play.

Deepfake, a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake”, refers to AI software that can superimpose a digital composite face on to an existing video (and sometimes audio) of a person.

The term first rose to prominence when Motherboard reported on a Reddit user who was using AI to superimpose the faces of film stars on to existing porn videos, creating (with varying degrees of realness) porn starring Emma Watson, Gal Gadot, Scarlett Johansson and an array of other female celebrities.

However, there are also a range of political possibilities. Filmmaker Jordan Peele highlighted some of the harmful potential in an eerie video produced with Buzzfeed, in which he literally puts his words in Barack Obama’s mouth. Satisfying or not, hearing Obama call US president Trump a “total and complete dipshit” is concerning, given he never said it.

Just as concerning as the potential for deepfakes to be abused is that tech platforms are struggling to deal with them. For one thing, their content moderation issues are well documented. Most recently, a doctored video of Nancy Pelosi, slowed and pitch-edited to make her appear drunk, was tweeted by Trump. Twitter did not remove the video, YouTube did, and Facebook de-ranked it in the news feed.

For another, they have already tried, and failed, to moderate deepfakes. In a laudably fast response to the non-consensual pornographic deepfakes, Twitter, Gfycat, Pornhub and other platforms quickly acted to remove them and develop technology to help them do it.

However, once technology is released it’s like herding cats. Deepfakes are a moving feast and as soon as moderators find a way of detecting them, people will find a workaround.

But while there are important questions about how to deal with deepfakes, we’re making a mistake by siloing it off from broader questions and looking for exclusively technological solutions. We made the same mistake with fake news, where the prime offender was seen to be tech platforms rather than the politicians and journalists who had created an environment where lies could flourish.

The furore over deepfakes is a microcosm for the larger social discussion about the ethics of technology. It’s pretty clear the software shouldn’t have been developed and has led – and will continue to lead – to disproportionately more harm than good. And the lesson wasn’t learned. Recently the creator of an app called “DeepNude”, designed to give a realistic approximation of how a woman would look naked based on a clothed image, cancelled the launch fearing “the probability that people will misuse it is too high”.

What the legitimate use for this app is, I don’t know, but the response is revealing in how predictable it is. Reporting triggers some level of public outcry, at which suddenly tech developers realise the error of their ways. Theirs is the conscience of hindsight: feeling bad after the fact rather than proactively looking for ways to advance the common good, treat people fairly and minimise potential harm. By now we should know better and expect more.

“Technology is a way of seeing the world. It’s a kind of promise – that we can bring the world under our control and bend it to our will.”

Why then do we continue to let the tech sector manage its own mess? Partly it’s because it is difficult, but it’s also because we’re still addicted to the promise of technology even as we come to criticise it. Technology is a way of seeing the world. It’s a kind of promise – that we can bring the world under our control and bend it to our will. Deepfakes afford us the ability to manipulate a person’s image. We can make them speak and move as we please, with a ready-made, if weak, moral defence: “No people were harmed in the making of this deepfake.”

But in asking for a technological fix to deepfakes, we’re fuelling the same logic that brought us here. Want to solve Silicon Valley? There’s an app for that! Eventually, maybe, that app will work. But we’re still treating the symptoms, not the cause.

The discussion around ethics and regulation in technology needs to expand to include more existential questions. How should we respond to the promises of technology? Do we really want the world to be completely under our control? What are the moral costs of doing this? What does it mean to see every unfulfilled desire as something that can be solved with an app?

Yes, we need to think about the bad actors who are going to use technology to manipulate, harm and abuse. We need to consider the now obvious fact that if a technology exists, someone is going to use it to optimise their orgasms. But we also need to consider what it means when the only place we can turn to solve the problems of technology is itself technological.

Big tech firms have an enormous set of moral and political responsibilities and it’s good they’re being asked to live up to them. An industry-wide commitment to basic legal standards, significant regulation and technological ethics will go a long way to solving the immediate harms of bad tech design. But it won’t get us out of the technological paradigm we seem to be stuck in. For that we don’t just need tech developers to read some moral philosophy. We need our politicians and citizens to do the same.

“At the moment we’re dancing around the edges of the issue, playing whack-a-mole as new technologies arise.”

At the moment we’re dancing around the edges of the issue, playing whack-a-mole as new technologies arise. We treat tech design and development like it’s inevitable. As a result, we aim to minimise risks rather than look more deeply at the values, goals and moral commitments built into the technology. As well as asking how we stop deepfakes, we need to ask why someone thought they’d be a good idea to begin with. There’s no app for that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The new rules of ethical design in tech

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2019

This article was written for, and first published by Atlassian.

Because tech design is a human activity, and there’s no such thing as human behaviour without ethics.

One of my favourite memes for the last few years is This is Fine. It’s a picture of a dog sitting in a burning building with a cup of coffee. “This is fine,” the dog announces. “I’m okay with what’s happening. It’ll all turn out okay.” Then the dog takes a sip of coffee and melts into the fire.

Working in ethics and technology, I hear a lot of “This is fine.” The tech sector has built (and is building) processes and systems that exclude vulnerable users by designing “nudges” that influence users, users who end up making privacy concessions they probably shouldn’t. Or, designing by hardwiring preconceived notions of right and wrong into technologies that will shape millions of people’s lives.

But many won’t acknowledge they could have ethics problems.

This is partly because, like the dog, they don’t concede that the fire might actually burn them in the end. Lots of people working in tech are willing to admit that someone else has a problem with ethics, but they’re less likely to believe is that they themselves have an issue with ethics.

And I get it. Many times, people are building products that seem innocuous, fun, or practical. There’s nothing in there that makes us do a moral double-take.

The problem is, of course, that just because you’re not able to identify a problem doesn’t mean you won’t melt to death in the sixth frame of the comic. And there are issues you need to address in what you’re building, because tech design is a human activity, and there’s no such thing as human behaviour without ethics.

Your product probably already has ethical issues

To put it bluntly: if you think you don’t need to consider ethics in your design process because your product doesn’t generate any ethical issues, you’ve missed something. Maybe your product is still fine, but you can’t be sure unless you’ve taken the time to consider your product and stakeholders through an ethical lens.

Look at it this way: If you haven’t made sure there are no bugs or biases in your design, you haven’t been the best designer you could be. Ethics is no different – making people (and their products) the best they can be.

Take Pokémon Go, for example. It’s an awesome little mobile game that gives users the chance to feel like Pokémon trainers in the real world. And it’s a business success story, recording a profit of $3 billion at the end of 2018. But it’s exactly the kind of innocuous-seeming app most would think doesn’t have any ethical issues.

But it does. It distracted drivers, brought users to dangerous locations in the hopes of catching Pokémon, disrupted public infrastructure, didn’t seek the consent of the sites it included in the game, unintentionally excluded rural neighbourhoods (many populated by racial minorities), and released Pokémon in offensive locations (for instance, a poison gas Pokémon in the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC).

Quite a list, actually.

This is a shame, because all of this meant that Pokemon Go was not the best game it could be. And as designers, that’s the goal – to make something great. But something can’t be great unless it’s good, and that’s why designers need to think about ethics.

Here are a few things you can embed within your design processes to make sure you’re not going to burn to death, ethically speaking, when you finally launch.

1. Start with ethical pre-mortems

When something goes wrong with a product, we know it’s important to do a postmortem to make sure we don’t repeat the same mistakes. Postmortems happen all the time in ethics. A product is launched, a scandal erupts, and ethicists wind up as talking heads on the news discussing what went wrong.

As useful as postmortems are, they can also be ways of washing over negligent practices. When something goes wrong and a spokesperson says, “We’re going to look closely at what happened to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” I want to say, “Why didn’t you do that before you launched?” That’s what an ethical premortem does.

Sit down with your team and talk about what would make this product an ethical failure. Then work backwards to the root causes of that possible failure. How could you mitigate that risk? Can you reduce the risk enough to justify going forward with the project? Are your systems, processes and teams set up in a way that enables ethical issues to be identified and addressed?

Tech ethicist Shannon Vallor provides a list of handy premortem questions:

- How Could This Project Fail for Ethical Reasons?

- What Would be the Most Likely Combined Causes of Our Ethical Failure/Disaster?

- What Blind Spots Would Lead Us Into It?

- Why Would We Fail to Act?

- Why/How Would We Choose the Wrong Action?

What Systems/Processes/Checks/Failsafes Can We Put in Place to Reduce Failure Risk?

2. Ask the Death Star question

The book Rogue One: Catalyst tells the story of how the galactic empire managed to build the Death Star. The strategy was simple: take many subject matter experts and get them working in silos on small projects. With no team aware of what other teams were doing, only a few managers could make sense of what was actually being built.

Small teams, working in a limited role on a much larger project, with limited connection to the needs, goals, objectives or activities of other teams. Sound familiar? Siloing is a major source of ethical negligence. Teams whose workloads, incentives, and interests are limited to their particular contribution seldom can identify the downstream effects of their contribution, or what might happen when it’s combined with other work.

While it’s unlikely you’re secretly working for a Sith Lord, it’s still worth asking:

- What’s the big picture here? What am I actually helping to build?

- What contribution is my work making and are there ethical risks I might need to know about?

- Are there dual-use risks in this product that I should be designing against?

- If there are risks, are they worth it, given the potential benefits?

3. Get red teaming

Anyone who has worked in security will know that one of the best ways to know if a product is secure is to ask someone else to try to break it. We can use a similar concept for ethics. Once we’ve built something we think is great, ask some people to try to prove that it isn’t.

Red teams should ask:

- What are the ethical pressure points here?

- Have you made trade-offs between competing values/ideals? If so, have you made them in the right way?

- What happens if we widen the circle of possible users to include some people you may not have considered?

- Was this project one we should have taken on at all? (If you knew you were building the Death Star, it’s unlikely you could ever make it an ethical product. It’s a WMD.)

- Is your solution the only one? Is it the best one?

4. Decide what your product’s saying

Ever seen a toddler discover a new toy? Their first instinct is to test the limits of what they can do. They’re not asking What was the intention of the designer, they’re testing how the item can satisfy their needs, whatever they may be. In this case they chew it, throw it, paint with it, push it down a slide… a toddler can’t access the designer’s intention. The only prompts they have are those built into the product itself.

It’s easy to think about our products as though they’ll only be used in the way we want them to be used. In reality, though, technology design and usage is more like a two-way conversation than a set of instructions. Given this, it’s worth asking: if the user had no instructions on how to use this product, what would they infer purely from the design?

For example, we might infer from the hidden-away nature of some privacy settings on social media platforms that we shouldn’t tweak our privacy settings. Social platforms might say otherwise, but their design tells a different story. Imagine what your product would be saying to a user if you let it speak for itself.

This is doubly important, because your design is saying something. All technology is full of affordances – subtle prompts that invite the user to engage with it in some ways rather than others. They’re there whether you intend them to be or not, but if you’re not aware of what your design affords, you can’t know what messages the user might be receiving.

Design teams should ask:

- What could a infer from the design about how a product can/should be used?

- How do you want people to use this?

- How don’t you want people to use this?

- Do your design choices and affordances reflect these expectations?

- Are you unnecessarily preventing other legitimate uses of the technology?

5. Don’t forget to show your work

One of the (few) things I remember from my high school math classes is this: you get one mark for getting the right answer, but three marks for showing the working that led you there.

It’s also important for learning: if you don’t get the right answer, being able to interrogate your process is crucial (that’s what a post-mortem is).

For ethical design, the process of showing your work is about being willing to publicly defend the ethical decisions you’ve made. It’s a practical version of The Sunlight Test – where you test your intentions by asking if you’d do what you were doing if the whole world was watching.

Ask yourself (and your team):

- Are there any limitations to this product?

- What trade-offs have you made (e.g. between privacy and user-customisation)?

- Why did you build this product (what problems are you solving?)

- Does this product risk being misused? If so, what have you done to mitigate those risks?

- Are there any users who will have trouble using this product (for instance, people with disabilities)? If so, why can’t you fix this and why is it worth releasing the product, given it’s not universally accessible?

- How probable is it that the good and bad effects are likely to happen?

Ethics is an investment

I’m constantly amazed at how much money, time and personnel organisations are willing to invest in culture initiatives, wellbeing days and the like, but who haven’t spent a penny on ethics. There’s a general sense that if you’re a good person, then you’ll build ethical stuff, but the evidence overwhelmingly proves that’s not the case. Ethics needs to be something you invest in learning about, building resources and systems around, recruiting for, and incentivising.

It’s also something that needs to be engaged in for the right reasons. You can’t go into this process because you think it’s going to make you money or recruit the best people, because you’ll abandon it the second you find a more effective way to achieve those goals. A lot of the talk around ethics in technology at the moment has a particular flavour: anti-regulation. There is a hope that if companies are ethical, they can self-regulate.

I don’t see that as the role of ethics at all. Ethics can guide us toward making the best judgements about what’s right and what’s wrong. It can give us precision in our decisions, a language to explain why something is a problem, and a way of determining when something is truly excellent. But people also need justice: something to rely on if they’re the least powerful person in the room. Ethics has something to say here, but so do law and regulation.

If your organisation says they’re taking ethics seriously, ask them how open they are to accepting restraint and accountability. How much are they willing to invest in getting the systems right? Are they willing to sack their best performer if that person isn’t conducting themselves the way they should?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: The Turing Test

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How avoiding shadow values can help change your organisational culture

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 18 SEP 2019

When convicted sex offender, alleged sex trafficker and financier to the rich and famous Jeffrey Epstein was arrested and subsequently died in prison, there was a sense that some skeletons were about to come out of the closet.

However, few would have expected that the death of a well-connected, social high-flying predator would call into disrepute one of the world’s most reputable AI research labs. But this is 2019, so anything can happen. And happen it has.

Two weeks ago, New Yorker magazine’s Ronan Farrow reported that Joi Ito, the director of MIT’s prestigious Media Lab, which aims to “focus on the study, invention, and creative use of digital technologies to enhance the ways that people think, express, and communicate ideas, and explore new scientific frontiers,” had accepted $7.5 million in anonymous funding from Epstein, despite knowing MIT had him listed as a “disqualified donor” – presumably because of his previous convictions for sex offences.

Emails obtained by Farrow suggest Ito wrote to Epstein asking for funding to continue to pay staff salaries. Epstein allegedly procured donations from other philanthropists – including Bill Gates – for the Media Lab, but all record of Epstein’s involvement was scrubbed.

Since this has been made public, Ito – who lists one of his areas of expertise as “the ethics and governance of technology” – has resigned. The funding director who worked with Ito at MIT, Peter Cohen, now working at another university, has been placed on administrative leave. Staff at MIT Media Lab have resigned in protest and others are feeling deeply complicit, betrayed and disenchanted at what has transpired.

What happened at MIT’s Media Lab is an important case study in how the public conversation around the ethics of technology needs to expand to consider more than just the ethical character of systems themselves. We need to know who is building these systems, why they’re doing so and who is benefitting. In short, ethical considerations need to include a supply chain analysis of how the technology came to be created.

This is important is because technology ethics – especially AI ethics – is currently going through what political philosopher Annette Zimmerman calls a “gold rush”. A range of groups, including The Ethics Centre, are producing guides, white papers, codes, principles and frameworks to try to respond to the widespread need for rigorous, responsive AI ethics. Some of these parties genuinely want to solve the issues; others just want to be able to charge clients and have retail products ready to go. In either case, the underlying concern is that the kind of ethics that gets paid gets made.

For instance, funding is likely to dictate where the world’s best talent is recruited and what problems they’re asked to solve. Paying people to spend time thinking about these issues, providing the infrastructure for multidisciplinary (or in MIT Media Lab’s case, “anti disciplinary”) groups to collaborate is expensive. Those with money will have a much louder voice in public and social debates around AI ethics and have considerable power to shape the norms that will eventually shape the future.

This is not entirely new. Academic research – particularly in the sciences – has always been fraught. It often requires philanthropic support, and it’s easy to rationalise the choice to take this from morally questionable people and groups (and, indeed, the downright contemptible). Vox’s Kelsey Piper summarised the argument neatly: “Who would you rather have $5 million: Jeffrey Epstein, or a scientist who wants to use it for research? Presumably the scientist, right?”

What this argument misses, as Piper points out, is that when it comes to these kinds of donations, we want to know where they’re coming from. Just as we don’t want to consume coffee made by slave labour, we don’t want to chauffeured around by autonomous vehicles whose AI was paid for by money that helped boost the power and social standing of a predator.

More significantly, it matters that survivors of sexual violence – perhaps even Epstein’s own – might step into vehicles, knowingly or not, whose very existence stemmed from the crimes whose effects they now live with.

Paying attention to these concerns is simply about asking the same questions technology ethicists already ask in a different context. For instance, many already argue that the provenance of a tech product should be made transparent. In Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology, we argue that:

The complete history of artefacts and devices, including the identities of all those who have designed, manufactured, serviced and owned the item, should be freely available to any current owner, custodian or user of the device.

It’s a natural extension of this to apply the same requirements to the funding and ownership of tech products. We don’t just need to know who built them, perhaps we also need to know who paid for them to be built, and who is earning capital (financial or social) as a result.

AI and data ethics have recently focused on concerns around the unfair distribution of harms. It’s not enough, many argue, that an algorithm is beneficial 95% of the time, if the 5% who don’t benefit are all (for example) people with disabilities or from another disadvantaged, minority group. We can apply the same principle to the Epstein funding: if the moral costs of having AI funded by a repeated sex offender are borne by survivors of sexual violence, then this is an unacceptable distribution of risks.

MIT Media Lab, like other labs around the world, literally wants to design the future for all of us. It’s not unreasonable to demand that MIT Media Lab and other groups in the business of designing the future, design it on our terms – not those of a silent, anonymous philanthropist.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Day trading is (nearly) always gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Managing corporate culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 30 JUL 2019

Until last week, you would have been forgiven for thinking a meme couldn’t trigger fears about international security.

But since the widespread concerns over FaceApp last week, many are asking renewed questions about privacy, data ownership and transparency in the tech sector. But most of the reportage hasn’t gotten to the biggest ethical risk the FaceApp case reveals.

What is FaceApp?

In case you weren’t in the know, FaceApp is a ‘neural transformation filter’.

Basically, it uses AI to take a photo of your face and make it look different. The recent controversy centred on its ability to age people, pretty realistically, in just a short photo. Use of the app was widespread, creating a viral trend – there were clicks and engagements to be made out of the app, so everyone started to hop on board.

Where does your data go?

With the increasing popularity comes increasing scrutiny. A number of people soon noticed that FaceApp’s terms of use seemed to give them a huge range of rights to access and use the photos they’d collected. There were fears the app could access all the photos in your photo stream, not just the one you chose to upload.

There were questions about how you could delete your data from the service. And worst of all for many, the makers of the app, Wireless Labs, are based in Russia. US Minority Leader Chuck Schumer even asked the FBI to investigate the app.

The media commentary has been pretty widespread, suggesting that the app sends data back to Russia, lacks transparency about how it will or won’t be used and has no accessible data ethics principles. At least two of those are true. There isn’t much in FaceApp’s disclosure that would give a user any sense of confidence in the app’s security or respect for privacy.

Unsurprisingly, this hasn’t amounted to much. Giving away our data in irresponsible ways has become a bit like comfort eating. You know it’s bad, but you’re still going to do it.

The reasons are likely similar to the reasons we indulge other petty vices: the benefits are obvious and immediate; the harms are distant and abstract. And whilst we’d all like to think we’ve got more self-control than the kids in those delayed gratification psychology experiments, more often than not our desire for fun or curiosity trumps any concern we have over how our data is used.

Should you be worried?

Is this a problem? To the extent that this data – easily accessed – can be used for a range of goals we likely don’t support, yes. It also gives rise to a range of complex ethical questions concerning our responsibility.

Let’s say I willingly give my data to FaceApp. This data is then aggregated and on-sold in a data marketplace. A dataset comprising of millions of facial photos is then used to train facial recognition AI, which is used to track down political dissidents in Russia. To what extent should I consider myself responsible for political oppression on the other side of the world?

In climate change ethics, there is a school of thought that suggests even if our actions can’t change an outcome – for instance, by making a meaningful reduction to emissions – we still have a moral obligation not to make the problem worse.

It might be true that a dataset would still be on sold without our input, but that alone doesn’t seem to justify adding our information or throwing up our arms and giving up. In this hypothetical, giving up – or not caring – means abandoning my (admittedly small) role in human rights violations and political injustice.

A troubling peek into the future

In reality, it’s really unlikely that’s what FaceApp is actually using your data to do. It’s far more likely, according to the MIT Technology Review, that your face might be used to train FaceApp to get even better at what it does.

It might use your face to help improve software that analyses faces to determine age and gender. Or it might be used – perhaps most scarily – to train AI to create deepfakes or faces of people who don’t exist. All of this is a far cry from the nightmare scenario sketched out above.

But even if my horror story was accurate, would it matter? It seems unlikely.

By the time tech journalists were talking about the potential data issues with FaceApp, millions had already uploaded their photos into the app. The ship had sailed, and it set off with barely a question asked of it. It’s also likely that plenty of people read about the data issues and then installed the app just to see what all the fuss is about.

Who is responsible?

I’m pulled in two directions when I wonder who we should hold responsible here. Of course, designers are clever and intentionally design their apps in ways that make them smooth and easy to use. They eliminate the friction points that facilitate serious thinking and reflection.

But that speed and efficiency is partly there because we want it to be there. We don’t want to actually read the terms of use agreement, and the company willingly give us a quick way to avoid doing so (whilst lying, and saying we have).

This is a Faustian pact – we let tech companies sell us stuff that’s potentially bad for us, so long as it’s fun.

The important reflection around FaceApp isn’t that the Russians are coming for us – a view that, as Kaitlyn Tiffany noted for Vox, smacks slightly of racism and xenophobia. The reflection is how easily we give up our principled commitments to ethics, privacy and wokeful use of technology as soon as someone flashes some viral content at us.

In Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology, Simon Longstaff and I made the point that technology isn’t just a thing we build and use. It’s a world view. When we see the world technologically, our central values are things like efficiency, effectiveness and control. That is, we’re more interesting in how we do things than what we’re doing.

Two sides of the story

For me, that’s the FaceApp story. The question wasn’t ‘is this app safe to use?’ (probably no less so than most other photo apps), but ‘how much fun will I have?’ It’s a worldview where we’re happy to pay any price for our kicks, so long as that price is hidden from us. FaceApp might not have used this impulse for maniacal ends, but it has demonstrated a pretty clear vulnerability.

Is this how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a chuckle and a hashtag?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Allan Waddell 27 JUN 2019

The great promise of artificial intelligence is efficiency. The finely tuned mechanics of AI will free up societies to explore new, softer skills while industries thrive on automation.

However, if we’ve learned anything from the great promise of the Internet – which was supposed to bring equality by leveling the playing field – it’s clear new technologies can be rife with complications unwittingly introduced by the humans who created them.

The rise of artificial intelligence is exciting, but the drive toward efficiency must not happen without a corresponding push for strong ethics to guide the process. Otherwise, the advancements of AI will be undercut by human fallibility and biases. This is as true for AI’s application in the pursuit of social justice as it is in basic business practices like customer service.

Empathy

The ethical questions surrounding AI have long been the subject of science fiction, but today they are quickly becoming real-world concerns. Human intelligence has a direct relationship to human empathy. If this sensitivity doesn’t translate into artificial intelligence the consequences could be dire. We must examine how humans learn in order to build an ethical education process for AI.

AI is not merely programmed – it is trained like a human. If AI doesn’t learn the right lessons, ethical problems will inevitably arise. We’ve already seen examples, such as the tendency of facial recognition software to misidentify people of colour as criminals.

Biased AI

In the United States, a piece of software called Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (Compas) was used to assess the risk of defendants reoffending and had an impact on their sentencing. Compas was found to be twice as likely to misclassify non-white defendants as higher risk offenders, while white defendants were misclassified as lower risk much more often than non-white defendants. This is a training issue. If AI is predominantly trained in Caucasian faces, it will disadvantage minorities.

This example might seem far removed from us here in Australia but consider the consequences if it were in place here. What if a similar technology was being used at airports for customs checks, or part of a pre-screening process used by recruiters and employment agencies?

“Human intelligence has a direct relationship to human empathy.”

If racism and other forms of discrimination are unintentionally programmed into AI, not only will it mirror many of the failings of analog society, but it could magnify them.

While heightened instances of injustice are obviously unacceptable outcomes for AI, there are additional possibilities that don’t serve our best interests and should be avoided. The foremost example of this is in customer service.

AI vs human customer service

Every business wants the most efficient and productive processes possible but sometimes better is actually worse. Eventually, an AI solution will do a better job at making appointments, answering questions, and handling phone calls. When that time comes, AI might not always be the right solution.

Particularly with more complex matters, humans want to talk to other humans. Not only do they want their problem resolved, but they want to feel like they’ve been heard. They want empathy. This is something AI cannot do.

AI is inevitable. In fact, you’re probably already using it without being aware of it. There is no doubt that the proper application of AI will make us more efficient as a society, but the temptation to rely blindly on AI is unadvisable.

We must be aware of our biases when creating new technologies and do everything in our power to ensure they aren’t baked into algorithms. As more functions are handed over to AI, we must also remember that sometimes there’s no substitute for human-to-human interaction.

After all, we’re only human.

Allan Waddell is founder and Co-CEO of Kablamo, an Australian cloud based tech software company.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.