I'm really annoyed right now: 'Beef' and the uses of anger

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 15 MAY 2023

Beef, the acclaimed new Netflix show, starts with an incident of one of the most commonplace examples of extreme emotion in our society – road rage.

We’ve all been there. You’re having a bad day. Or, if you’re the two heroes of Beef, a bad life – Danny (Steven Yeun), is a frustrated contractor, has sailed from one disappointment to the next, while Amy (Ali Wong), has big dreams that she can’t quite seem to realise. In another life, these two might have joined forces to combat the stresses that seem ready to swallow them whole. Instead, Danny almost runs into Amy in a brutalist parking lot.

Rather than either of them letting this go, the pair escalate their titular beef. They swear at one another. They make threatening motions with their cars. And then, before they know it, they’re all-out-furious, embroiled in a comically overblown chase sequence on the highway.

And it doesn’t end there, either. After this one act of aggression, Danny and Amy become locked in a series of escalating vengeful manoeuvres, from pissing on each other’s bathroom floors to all-out violence. It’s one incident of rage that ruins both of their lives. And, most troubling of all, Danny and Amy seem to love their fury. They embrace it totally, even as houses burn to the ground around them.

The consequences of anger

Clearly, Beef tells us that anger has the ability to escalate – that it’s an emotional state that can start minor, and then, if we don’t do anything about it, has the power to totally consume us. As Jennifer S. Lerner and Larissa Z. Tiedens note in their paper Portrait of the Angry Decision Maker, anger has “uniquely captivating properties” – if we’re not careful, it’ll make us one-track minded.

It’s partially for this reason that anger is often viewed as a “negative” emotion, one we would do better without. As philosophers Paul Litvak, Jennifer Lerner, and Larissa Z. Tiedens point out in their paper Fuel In The Fire, “anger makes people indiscriminately punitive, indiscriminately optimistic about their own chances of success, careless in their thought, and eager to take action.”

The angry person is not typically viewed as the one in the best place to make judgements. The angry person can act, as Danny and Amy do, irrationally, frequently moving against their own best interests. How many people have we all met whose rage has made them ruin a relationship that they value, or get themselves in trouble at work?

Much therapeutic practice is designed to eradicate negative emotions. Psychological practices like DBT (Dialectical Behaviour Therapy) encourage patients to rid themselves of anger, so that they might think clearly. This follows a version of the model of emotions favoured by the stoics. Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor and key proponent of the Stoic model, once wrote, “A real man doesn’t give way to anger and discontent, and such a person has strength, courage, and endurance—unlike the angry and complaining.”

On this model of emotional regulation, the right thing to do is take anger as a kind of emotional data, process it, wait for it to pass, and then act. Not out of anger. Deciding what to do only when calm.

What anger does

We might be quick to assume, like the Stoics, that anger is something to always be avoided. But in doing so, we ignore the way anger gets things done. Consider the anger at the heart of key civil rights movements from across the years. “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention,” has been a rallying cry used for everything from the fight for feminist rights, to the struggle against racism. There are clearly injustices that we are right to feel angry about.

In fact, dismissing someone’s concerns because they are angry has sometimes been used to try and deflate moves towards equality. Suffragettes, for instance, were often painted by the press as “hysterical” and out of control, their righteous fury seen as cause to eradicate their movements.

Moreover, anger has uniquely focusing effects. We see this in Beef. Before they almost crash into each other, Danny and Amy are aimless, buffeted around by forces bigger than them. The fury that they feel at one another focuses them. It is something that they control; something within their power. It inspires action from people whose lives have been marked by inaction.

So where is the point of balance between these two perspectives? Can we feel anger, and allow it to focus us, without allowing it to destroy our life, and make us bad decision makers?

The philosopher Martha Nussbaum believes so. Nussbaum is well-known for her rehabilitation of stoic philosophy – much of her philosophical work has been about bringing that ancient movement back into the light.

In her book Anger and Forgiveness, she embraces key features of the stoic opinion on anger. She calls anger a “trap”, and notes that she does not believe that anger “is morally right and justified.” For her, anger has all the negative qualities described above – it often leads to actions designed as “payback”, retaliative gestures that are seen to “assuage the pain or make good the damage.” She does not believe anger does this. She thinks it merely adds more hurt to a pile of hurt, hurting the aggressor as much as the victim they lash out at.

But Nussbaum does not dismiss anger out of hand. This makes her different to many stoics. She thinks anger is to be eradicated, but creates a related category to that feeling called “transition-anger.” This is not simply anger. It is not the desire to punish. It is not defined by wallowing in negative emotions. Instead, she describes the “entire cognitive content” of “transition-anger” as being made up of the thought, “How outrageous. That should not happen again.”

Transition-anger doesn’t make us merely lash out at those who have hurt us. Instead, it directs us towards positive forward action. We use it to focus ourselves. But that focus drives us towards good moral behaviour. It turns unmoved citizens into powerful figures of protest. It creates community, people united in their desire to make the world a better place.

Amy and Danny aren’t bad moral actors merely because they’re angry, then. They’re bad moral actors because they do the wrong things with their anger. It’s not that they should never have felt rage. It’s that they allowed that rage to make them ugly and cruel, when it should have made them kinder.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

WATCH

Relationships

Deontology

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAY 2023

We’re thrilled to announce we’ve appointed Dr Gwilym David Blunt as an Ethics Centre Fellow.

A writer and commentator on global politics and philosophy, David has spent time as a Senior Lecturer in International Politics at City, University of London and as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Cambridge. Now based in Australia, David has published numerous books, appeared on ABC The Drum and Monocle Daily, and has written for The Conversation, ABC and International Affairs.

To welcome him, we sat down with David to discuss the important role ethics can play when it comes to politics, human rights and philanthropy.

What attracts you to the field of philosophy?

We are often told to ‘go with your gut’ when making decisions. This has always struck me as genuinely terrible advice. Our instincts can be conditioned by any number of prejudices or misconceptions. Philosophy is a way of interrogating these instincts and thinking systematically about hard questions.

How does your background in international politics and human rights shape your approach to philosophy and ethics?

International politics fascinates me because it is often treated as a place where ethics don’t apply. It’s seen as a place in which raw power determines the norms that govern politics, something that few would say is acceptable in domestic politics. Yet, this seems ridiculous.

Take the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many people around the world reacted in horror because wars of aggression are wrong. This is more than an intuition. Self-determination is grounded in an ethical judgement that people have a right to determine their collective destiny without interference. We might question the scope of this right, but most people will agree that at the very minimum it prohibits wars of aggression. There is clearly a place for ethics in world politics.

In fact it is more than a place, there is an urgency for ethics in world politics. The Covid-19 pandemic clearly showed how humanity as a whole faces shared challenges. The viruses that cause pandemics and the greenhouse gases that cause climate change don’t respect the arbitrary lines we draw on maps. We cannot hide behind closed borders and hope it all just goes away. These threats raise ethical questions about duties and responsibilities, where burdens lie, and what we owe to the future.

What kind of work will you be engaging with at The Ethics Centre?

The Ethics Centre is hosting me while I work on my next book which is on philanthropy. This is a topic that I’ve been interested in for a long time, but was on the side burner until the pandemic brought it back into focus. My work usually looks at the grimmer aspects of political philosophy, such as war, terrorism, and extreme inequality. So, it is nice to be working on something that gives some reasons to be hopeful about humanity. Although philanthropy raises a lot of interesting questions about justice, reputation laundering, and fairness.

I’ll also be writing some articles and assisting as a media spokesperson.

Which philosopher has most impacted the way you think?

It’s difficult to pick one, but I think it would have to be Philip Pettit, who isn’t a household name, but, along with Quentin Skinner, revived republicanism in political philosophy, which is what grounds my work. Now, don’t confuse republicanism with Donald Trump or right-wing MAGA politics or even with anti-monarchism. Republicanism is at its core a philosophy of freedom; it’s central claim is no person can be free if they are under the arbitrary power of someone else.

You have also done a lot of research on poverty and the distribution of wealth. What role do you think philanthropy and charity has or should have in that space?

I like to compare philanthropy with the façade of a building. It is something that beautifies, but it isn’t necessary to create a stable and functional structure. To continue this analogy, the parts of a building that keep it up, foundations and reinforced concrete, these are the province of justice. My worry with philanthropy is that it is taking up those structural roles, that it is subverting the role of justice. This isn’t a trivial matter because philanthropy is often characterised by the arbitrary power that republicans tend to worry about. Access to healthcare or education should not rest on the whim of a wealthy person, even if they are a good person, these are things that all people are owed as matter of right.

Your recent book Global Poverty, Injustice and Resistance argues our right to politically resist. We’re currently seeing some extreme cases of human right infringements around the world – what’s an example of resistance you’ve noticed that seems to be having a significant effect?

Resistance is such an interesting subject, because it covers such a wide range of activities. Most people tend to think of revolutions or mass civil disobedience as the paradigm examples of resistance, but I find the less visible forms of resistance more compelling.

I think the best example is illegal or irregular immigration for socio-economic reasons. This topic is one that generates a lot of extreme feelings in wealthy states like Australia and the United States, which is why I find it interesting. People who flee extreme poverty are voting with their feet against our current global political system, where many people are denied a reasonably dignified human life simply because they were born in the wrong country.

Many people’s first instinct is to say that illegal immigrants are doing something wrong, because they are breaking the law, but this goes back to what I said that the beginning of this interview: our instincts can be wrong.

We need to seriously start asking questions about why people cross borders illegally. It takes a lot for someone to leave their home to go to a distant land where they might know no one, have to learn new customs and language, and there is a chance they might die in the journey. We need to think about our complicity with the economic systems that produce avoidable poverty and exacerbate climate change, the push factors for this sort of migration. My hope is that this may help to create systemic change.

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

For work, I’m finishing up reading Paul Vallely’s massive Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg which is a good accessible examination of philanthropy and re-reading Will MacAskill’s What We Owe the Future for a short piece I’m working on. And I’m also revisiting some of the greatest hits of republicanism from Pettit and Skinner for a new YouTube series I’m doing.

For pleasure, I’m reading Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, which is really amazingly written. She’s one of those people who makes me actively jealous of their wordcraft. And I’m reading my wife I, Claudius before bed.

Watching, we are doing a nostalgia trip and rewatching the X-Files, which is fun even if the last few seasons are pretty bad. The sad thing about watching it in 2023 is that fringy, conspiracy theory stuff was just fun entertainment 30 years ago and now it has turned extremely sinister, which kind of drains a bit of the joy out of it.

Listening, I’m a big Last Podcast on the Left fan, because sometimes I just need to learn about cults, aliens, cryptids, and true crime. And since moving to Australia I’ve been getting into Australian music and have been bingeing King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Putting it simply, ethics is my ‘bullshit detector’; it helps me recognise my own bullshit, which keeps me from being complacent, and the bullshit of society at large, which seems to be really piling up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How can you love someone you don't know? 'Swarm' and the price of obsession

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 19 APR 2023

When we first meet Dre (Dominique Fishback), the terrifying anti-hero of Swarm, she’s obsessed.

For years, she has been busy constructing a world with the pop singer Ni’Jah at its centre – the musician has become the yardstick by which Dre measures whether anything in her life is worthwhile. This isn’t just a casual interest for Dre. It’s everything.

And because it’s everything, before too long, Dre starts murdering in Ni’Jah’s name. In the world of Swarm, violently dispatching anyone who stands in the way of the Ni’Jah fandom is par for the course. Indeed, much of the show’s dark comedy comes from the messed-up, but eerily logical, motivation behind Dre’s bloodthirsty rampage, which takes her across the United States, and sees her dispatch both Twitter trolls and fellow fans.

No doubt then – love is at the centre of Dre’s life. Only, it’s a violent, obsessive kind of love. And a love that attaches itself to someone that Dre doesn’t even know.

She just gets me

Dre’s form of love is a parasocial one. She pores over the details of Ni’Jah’s life, sharing factoids about the pop star with her fellow stans. No matter that she doesn’t even know Ni’Jah, really. She doesn’t have to meet her. After all, she has Ni’Jah’s music, and music is the language of the soul, right?

This kind of romantic obsession is a common feature of the modern age, though it wasn’t invented by it. Certainly, parasocial relationships aren’t new. They go back as far as the fans who tore at classical composer Franz Liszt’s clothes, gripped by a fever called Lisztomania that resembles the hysteria that has met boy bands over the decades.

When people feel seen by art, it makes sense that they also feel seen by the artist that has made it. You love the music, and then you love the musician. This goes a long way to explaining the behaviour of modern stans, who are not content to merely listen to the newest pop album. They collate pictures of the popstar in question; try to learn details about their personal life; hang on to their every word.

Indeed, what sets Beyonce stans apart from Liszt fanatics is the way that technology has stepped up this fascination with the lives of artists. It used to be you had to mail in a self-addressed envelope to a Beatles fanclub to connect with likeminded folks. Now you can log on, sharing and ramping up your mutual obsession. All in it together.

What love makes us do

Parasocial relationships can spawn a range of immoral acts. They overstep the boundaries of privacy of artists, treating them like commodities, not people.

This is a violation of one of philosopher Immanuel Kant’s most important tenets – Kant says, use people as ends in themselves, their own people, rather than mere means. Pop stans don’t do this. They use popstars as mediums for their art.

Stans also tend to operate under a groupthink mentality, a kind of contagious sharing of values and emotions that the philosopher Derek Matravers called out in his book, Empathy. Matravers noted that crowds can “catch” feelings from each other – that if one person is angry, then a person who witnesses that anger will pick up on it, through what is known as “emotional contagion.” Then, that anger spreads. And when it spreads out of control, violence can occur.

That emotional catching is key to Swarm, and Dre’s obsession – she and her fellow stans whip themselves up into a frenzy of hatred, a virulence particularly directed towards the other. This other-directed hatred has been noted by philosopher Jesse Prinz, who argues that empathy and emotional contagion both tend to be triggered in the cases of perceived likeness. As in, if you think someone resembles you in important ways, you’re more likely to feel what they feel. That’s why groups form. Groups share perceived traits – in the case of Swarm, a love of Ni’Jah – and catch feelings of those in their group, without catching the feelings of those outside the group. Thus – an us and them mentality.

This in turn accounts for the behaviour we see in real life, outside of Swarm, particularly on Twitter. There, stans turn on people who commit the slightest perceived indiscretion, threatening, in some cases, their homes, livelihood, and health. Take the pop music critic, not named here to avoid kicking off a potential wave of abuse, who criticised a pop music stan and had her home address found, and threatening messages left on her voicemail.

A love that doesn’t change

It’s worth noting that parasocial relationships aren’t totally foreign to other forms of love. Many of us are guilty of turning the object of our infatuation into something other than what they are. Consider those early days of romance, when everything that the object of our affection has touched or produced seems blessed by a kind of glow – there’s the coffee cup they drank from, and then left at ours. There’s the toothbrush they used, on the bathroom mantle.

But what makes parasocial relationships different to others is the strange way in which they develop and change. Or, don’t change. When the person you love is right in front of you, your affection molds to their shape. They do things, and you respond to those things. They are human, so they fuck up, and your adoration changes in step with those fuck-ups.

Parasocial relationships lack that constant evolution. Pop albums don’t change. You listen to the new Taylor Swift album, and then months go by, and you listen to it again, and again, and again. Not a note has shifted since that first time. So your love can stay locked in that honeymoon phase – that obsessive, giddy kind of romance, consistent in intensity.

Without evolution, our passion is obsession, and obsession can turn us into bad ethical actors of all sorts.

This unchanging nature also explains that darker side of modern fandoms – the side targeted by Swarm. Dre doesn’t see Ni’Jah’s flaws. Doesn’t get exposed to the healthy regularity that romance descends into. That keeps her obsession at a fever pitch. One with such violent passion at its heart that it’s only a matter of time until it becomes literally violent.

Thus, Swarm, and indeed modern fandom itself, teaches us the ethical importance of evolution. Not only is a static love a dying love – how many relationships break up because of the horrifying routines that we can settle into, years into being with someone? The monotony of it all? Static love is also a dangerous love. Without evolution, our passion is obsession, and obsession can turn us into bad ethical actors of all sorts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Big thinker

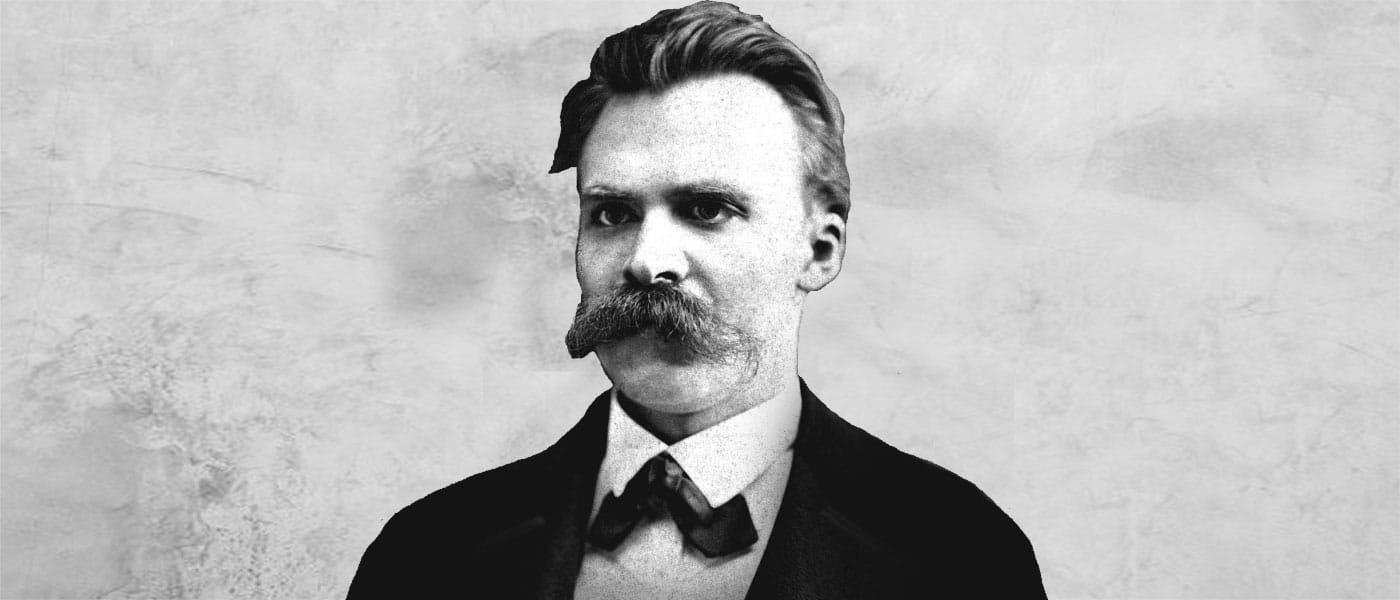

Relationships

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

FODI: The In-Between

An audio time capsule from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, recording this moment in time

We are at the end of an era, and on the precipice of a new one. What do we keep? And what do we leave behind?

FODI: The In-Between features 8 conversations between 16 of the world’s biggest thinkers, featuring Stephen Fry, Roxane Gay, Waleed Aly, Peter Singer, Sam Mostyn, Slavoj Žižek, Naomi Klein and more. Accompanied by 8 short creative sound responses to the themes released alongside each conversation.

FODI: The In-Between tackles the big issues of our world and future, from climate change and global politics to artificial intelligence, truth and social media.

“The In-Between project is like a requiem for a passing age. These are the types of candid and big thinking conversations that you hear in the green room at FODI, which we are recreating in a new audio format.” – Danielle Harvey, Festival Director, Festival of Dangerous Ideas

Listen to FODI: The In-Between trailer

EPISODES

Episode 01 | Joya Chatterji & Stephen Fry | There is no beginning

In a conversation moderated by Simon Longstaff, historians Joya Chatterji and Stephen Fry discuss whether the age of Enlightenment is truly coming to an end. They share varying Enlightenment narratives that cross geographical, cultural and class borders and challenge the attempt to define an era of history as linear, with a definitive start and end point.

Episode 01.5 | Light Shines | B-Side

Sydney-based writer Tasnim Hossain records her written take on the meandering histories of Enlightenment discussed by Joya Chatterji and Stephen Fry, and the experimental sounds of the first known recordings of the human voice. Music is composed from sounds found in the archives of firstsounds.org, and recordings taken from a museum of mechanical music (fairgroundfollies.com).

Episode 02 | Sam Mostyn & Peter Singer | We have failed to protect those who don’t yet exist

A conversation between business sustainability advisor Sam Mostyn and moral philosopher Peter Singer, moderated by Simon Longstaff. Sam and Peter discuss the role of business in sustainability and climate action, the discrepancies between our values and monetary donations for global aid, and the ethics of responsibility we have toward the generation of humans who don’t yet exist. They touch on how the pandemic has highlighted gender and class divisions, along with the significance of community and care.

Episode 02.5 | Anthropocene | B-Side

We hear the recorded sound of the invisible electromagnetic landscape that humans created unintentionally, allowing us to tune in to what our environment has to endure. Against a backdrop, we hear the voices of anonymous FODI listeners, recording their hopes and fears for the future of humanity, and a poem by Sylvie Barber and Simon Longstaff. Anthropocene is a response to Sam Mostyn and Peter Singer’s discussion.

Episode 03 | Lee Vinsel & Tyson Yunkaporta | A gradual decline into disorder

Lee Vinsel and Tyson Yunkaporta speak with Ann Mossop about the passing age, apocalypses, and the cyclical nature of eras. Their conversation is anchored in language: both speak of systems, entropy, the roles of maintainers or custodians, and the machines and languages of capitalism. Tyson explains entropy by connecting an incident of Aboriginal people spearing Dutchmen centuries ago to the modern-day experiences of colonialism, and Lee speaks of entropy as the natural breaking down of systems.

Episode 03.5 | Within Salt | B-Side

During Sydney’s most recent lockdown, sound artist Alexandra Spence submerged a 15 minute-long piece of cassette tape in seawater. The cassette tape contained a field recording of waves, and a recording of Alex’s voice offering a non-definitive, and non-hierarchical list of things found in the Pacific Ocean. The resulting physical deterioration of the magnetic tape and degradation of the audio recording can be heard in this composition. ‘Within Salt’ is a short piece that responds to Lee Vinsel’s take on entropy and the breaking down of technology, along with Tyson Yunkaporta’s words on the importance of story and of preserving nature over data.

Episode 04 | Eleanor Gordon-Smith and Slavoj Žižek | The age of doubt, reason and conspiracy

Against the pillars of Enlightenment, how can we make sense of conspiracy theories, tribalism, and deepening divisions between our beliefs? In a conversation moderated by Simon Longstaff, Eleanor Gordon-Smith and Slavoj Žižek discuss the proliferation and saturation of knowledge, the rise of conspiracy theories, and whether or not the Age of Enlightenment is coming to an end.

Episode 04.5 | The Dancer | B-Side

Recording art for a post-human world, a machine attempts to describe a human dance. The piece responds to Eleanor Gordon-Smith and Slavoj Žižek’s discussion, the power of words to create reality, and the experience of emotion between the digital or artificial and what we take as ‘real’.

Episode 05 | Joanna Bourke & Toby Walsh | Killer robots and the human construction of war

By the year 2062, it is predicted that we will have built machines that are as intelligent as humans. Modern weapons will become more autonomous, machines will further infiltrate our daily lives, and the way we think of humanity will be permanently altered. To understand what lies ahead and learn from our past, Ann Mossop sits between Joanna Bourke and Toby Walsh in a conversation about the future of AI, killer robots and what it means to be human.

Episode 05.5 | Semi-Autonomous | B-Side

A text-generating AI that has been trained with FODI transcripts speaks in conversation with a deepfake AI about violence, conspiracy theories and what it means to be human. Our FODI-trained AI was created using Max Woolf’s simplified version of OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2 (GPT-2) and Google Colab; Max has created a tutorial so that anyone can train an AI model for free. Semi-Autonomous is a response to Joanna Bourke and Toby Walsh’s discussion.

Episode 06 | Roxane Gay & Kate Manne | The mild terror of publishing feminist cultural criticism

Roxane Gay and Kate Manne speak to this moment in time, the nature of progress, and their hopes and fears for the future. In a conversation moderated by Ann Mossop, they discuss modern feminism, online communication and social media, and the “lean white male” bodies that history has centred over those that exist on the periphery.

Episode 06.5 | Tongues | B-Side

Tongues is an explicit, potent musical manifesto, exploring having your voice taken away, in response to Roxane Gay and Kate Manne’s discussion. Tongues is written and performed by Tanya Tagaq, a Canadian Inuk improvisational singer, avant-garde composer, bestselling author, and Saul Williams, Sumach Valentine, Jesse Zubot; published by Songs of Six Shooter B (SOCAN), Martyr Loser King (ASCAP), Warp Music Limited (PRS/ASCAP), Jesse Zubot (SOCAN).

Episode 07 | S. Matthew Liao & John Rasko | Immortality, fraud and the future of the human species

From the ancient tale of Gilgamesh to Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, the dream of immortality has long captured the imagination of writers and scientists. But how close are we to conquering death? In a conversation moderated by Simon Longstaff, neuro-ethicist S. Matthew Liao speaks with stem cell-researcher John Rasko about the age of regenerative medicine, the heroes and fraudsters of the past, and the reality of a distant future where genetic engineering helps humans to colonise future planets.

Episode 07.5 | Revivification | B-Side

CellF is a cybernetic musician and the world’s first neural synthesiser, created by Perth-based artist and researcher, Guy Ben-Ary. Its ‘brain’ is made of biological neural networks bio-engineered from the artist’s own cells, that grow in a petri dish and control in real time its ‘body’ – an array of synthesizers that play music live with human musicians. Revivification is a short piece that responds to S.Matthew Liao and John Rasko’s discussion.

Episode 08 | Waleed Aly & Naomi Klein | Our entanglements have been exposed

On the precipice of a new age, what are the forces that will bring us together, and what is driving us apart? Simon Longstaff sits between Waleed Aly and Naomi Klein as they discuss the decline of meta-narratives in society and politics, reconciling coloniser and Indigenous histories and narratives, and trends of hyper-individualism and conspiracy. Neither are wholly optimistic nor pessimistic about the future that lies ahead.

Episode 08.5 | Endtropy | B-Side

Whats inside the guide?

WITH THANKS

Danielle Harvey, Festival Director and Co-curator

Simon Longstaff, Co-curator

Ann Mossop, Co-curator

Rebecca Blake, Producer, FODI

Jess Hamilton, Senior Audio Producer, Audiocraft

Adam Connelly, Sound Designer and Composer, Audiocraft

Jasmine Mee Lee, Researcher/producer, Audiocraft

Weronika Razna, Mixing engineer, Audiocraft

Kate Montague, Executive Producer, Audiocraft

Michelle Walter, Head of Fundraising and Development, FODI

Jess Lewis, Content Manager, FODI

Kathleen Evesson, Head of Marketing and Communications, FODI

Design by Glider Global

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2023

In a world where some women still struggle to have their voices heard, there are many female thinkers whose contributions throughout history have impacted our thinking today. This International Women’s Day, we’re celebrating five influential Australian philosophers, activists, academics and thinkers who have shaped our ethical landscape and beyond.

Kate Manne

Kate Manne (1983-present) is an Australian philosopher best known for her feminist, moral and social philosophies, and her work around misogyny and masculine entitlement. Notably, instead of thinking of misogyny as hatred for women, Manne redefines the word and focuses on its systematic nature, specifically in how law enforcement polices women and girls to uphold gender norms.

To illustrate masculine entitlement, Manne coined the term “himpathy”, which explains “the disproportionate … sympathy extended to a male perpetrator over his … less privileged, female targets in cases of sexual assault, harassment, and other misogynistic behaviour.” She took a deep dive into this idea in her 2020 book Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women and critiqued Justice Kavanaugh’s appointment to the US Supreme Court, despite allegations of sexual assault, as “himpathy” in action.

Marcia Langton

Marcia Langton (1951-present) is considered one of Australia’s top academics, anthropologists and geographers. As the great–great–granddaughter of survivors of the frontier massacres and a Yiman person, Langton uses her influential platform to advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. When her great aunt Celia Smith, an organiser of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, convinced her to work with the council in 1967, Langton was launched into her outspoken career of Aboriginal activism.

Since, she’s worked on vital pieces of research and legislation impacting Indigenous people and has held the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at University of Melbourne since 2000. More recently, she’s worked on the Voice to Parliament that would recognise First Peoples in the Constitution, permitting them “to have a say in the legislation that affects their lives.” To her, upholding Indigenous knowledge and rights goes beyond environmental preservation: It’s cultural preservation.

Veena Sahajwalla

Veena Sahajwalla (undisclosed-present) is an Australian scientist, inventor and professor. Named one of Australia’s 100 most influential engineers in 2015 and one of the 100 most innovative in 2016, Sahajwalla is putting New South Wales on a path to a net zero carbon, circular economy. Nicknamed “Queen of Waste”, she’s worked to repurpose everything from old clothes to beer bottles and abandoned mattresses. Growing up in Mumbai, India, she was introduced to the art of recycling through waste-pickers.

Her most famous invention, “Green Steel”, replaces coking coal in steel production with old, shredded tyres. The process is much less carbon-intensive and prevents 2 million tyres from hitting the landfill each year. This, in addition to her numerous other achievements – such as being councillor on the Australian Climate Council and opening the world’s first e-waste microfactory on the University of New South Wales’s campus – led to her being named Australian of the Year in 2022

Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (1939-present) is a writer and regarded one of the major voices of the radical feminism movement in the latter half of the 20th century. Born in Melbourne, her 1970 book, The Female Eunuch, made her a household name where she argued the expectation for women to be feminine – in the clothes they wear, in marriage, in having a nuclear family – is what represses them. And so she calls for liberation, for revolution, because this repression cultivates political inaction.

Since then, she’s written several other books on feminism, literature and the environment. Of all her ideas and claims, she holds that freedom is the most dangerous, though critics say otherwise. Some of Greer’s views of have created controversy, including her views on gender binaries and expressions, rape and the #MeToo movement. While her audacious language, beliefs and controversy have cultivated furore at times, Greer remains a prominent participant in intellectual discourse and debate.

Val Plumwood

Val Plumwood (1939-2008) was an Australian philosopher, activist and ecofeminist. Her work focused on anthropocentrism and discouraging the idea that humans are superior to and separate from nature. This “standpoint of mastery”, as she called it, legitimised the “othering” of the natural world, which included women, indigenous and non-humans.

She experienced a major paradigm shift that coloured her opposition to anthropocentrism after she was attacked by a crocodile while canoeing alone at Kakadu National Park. She couldn’t believe such a thing was happening to her, a human. She went from being top of the food chain to part of it, having “no more significance than any other edible being.” To Plumwood, the flawed mindset of only human life mattering is the root of our planet’s degradation. She proposed nurturing the natural world for nature’s own good instead of our own, famously questioning, “Is there a need for a new, an environmental, ethic – an ethic of nature?”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 MAR 2023

The undead are everywhere. It’s not just that our culture is obsessed with zombies, from The Walking Dead to The Last Of Us. It’s that our cultural discussions are zombies themselves – they just won’t die.

We go over the same old arguments time and time again, to no seeming progression or end. Just take the cultural discussions around depiction and endorsement where the lines have been drawn in the sand.

For those on one side of the line – the instigators of this particular debate – artists who depict monstrous acts are seen to be agreeing with these acts. The mere depiction of violence, for instance, is seen as a kind of thumbs up to that violence, tacitly encouraging it.

On this view, artists are moral arbiters, and the images and stories that they put out into the world have a significant, behaviour-altering effect. Depicting criminals means “normalising” criminals, which means that more viewers will believe that criminal acts are acceptable, and, theoretically, start doing them.

This view has a historical precedent. Art has long been political, used by states and religious groups in order to provide a form of moral instruction – consider devotional Christian paintings, which are designed to exhort viewers to better behaviour.

Certainly, there are still artists and artworks with a pointedly ethical and political mode of instruction. From government PSAs that borrow storytelling techniques that artists have used for years, to the glut of Christian-funded films like God Is Real, art objects have been designed as transmission devices for a particular point of ethical view. Even Captain Marvel, another in a seemingly unending glut of superhero movies, was created in partnership with the airforce, and depicts the military in a childishly positive light.

But acting as though all art has this moral framework – that everything is a form of fable, with a clear ethical message – is a mistake. Moreover, it elevates a discussion about art beyond what we usually think of as aesthetic principles, and into political ones. It’s not just that the instigators who view all art as essentially and simply instructional worry we’re getting worse art. It’s that they worry we’re getting more dangerous art.

In just the last 12 months, Martin Scorsese has been condemned at least three times in some circles of the internet for glorifying depravity with his films about criminal underbellies.

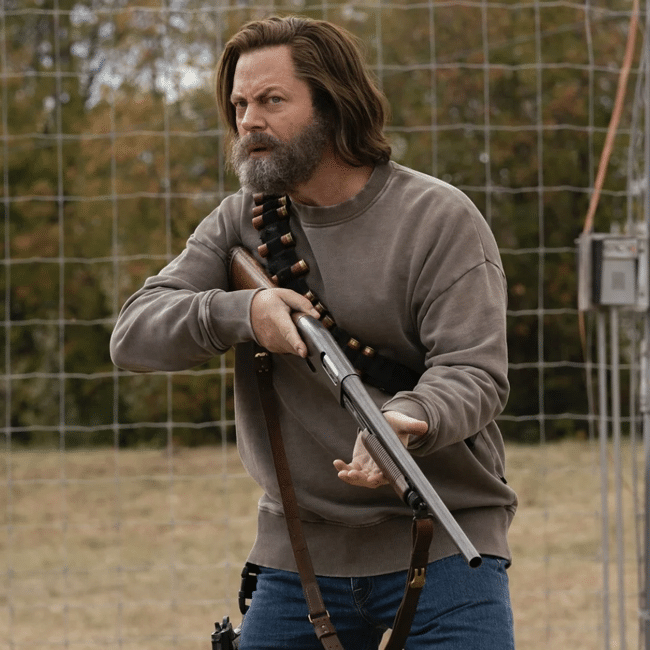

But the argument really saw its time in a sun that won’t set with the release of the bottleneck episode of The Last of Us, a much heralded – and deeply contentious – piece of television.

Fungal Zombies And Queer Representation

In the episode, Parks and Recreation’s Nick Offerman and The White Lotus’ Murray Bartlett embark upon a queer romance while the world ends around them. Though highlighted for its sensitivity in some corners of the discourse, the episode received significant pushback.

For writer Merryana Salem of Junkee, the episode was an example of “pinkwashing”, due to the fact that the characters value “individual liberty over community good.” As in – they try to survive during an apocalypse. Salem criticises the show for depicting queer characters looting and pillaging, rather than sharing resources. By aligning queer representation with selfish behaviour, Salem appears to be arguing that the show will platform and perhaps normalise libertarian values of the self as important above all others.

“Far from framing this attitude as negative, a song plays cheerily over Bill hoarding, looting resources, and setting up security systems that would prevent anyone in the immediate area from even using the electricity in the local plant”, Salem writes.

The argument here is simple. One act is shown onscreen instead of another. That is a choice. The choice, combined with the aesthetics around it – cheery music – means that this choice is designed to impress upon the audience the admirable nature of the character, even as he does less than admirable things.

What such an argument precludes, however, is the complexity inherent in the episode. The Last of Us’ showrunner, Craig Mazin, may not be pointing at good and bad as directly as his critics assume. Bill is a man trying to carve out love and life under impossible circumstances. In an ideal world, he wouldn’t be hoarding resources. In an ideal world, he would be living quietly, in a community. He doesn’t want to make do in the middle of a zombie outbreak.

The beauty of the episode, then, is the way it makes a case for the power of an easy love formed under uneasy circumstances. Bill’s flawed because he’s been made that way by an outbreak of, ya know, fungus zombies. And yet still he finds some crooked form of redemption in the arms of another.

That’s what is missing from so many of these debates about depiction versus endorsement – nuance.

Good storytellers don’t depict flatly. They depict with complexity. With differing shades of light and dark. And so their art should be analysed on those merits, with criticism that is itself complex.

But more than that, we need to ask ourselves, finally, whether depicting reprehensible acts onscreen really has the effect that these critics assume it does.

The Return Of The Big Bad

Take some of the most reprehensible people on television. Walter White of Breaking Bad. Tony Soprano of The Sopranos. Even Don Draper of Mad Men. These men, who washed over our screens during the start of the Golden Age of Television, do bad things.

More than that, they get rewarded for them. Tony is lavished with success of all forms – money, power, opportunity. Walter finds, through drug-dealing, a new level of self-confidence and authority. Don never gets a traditional comeuppance, unless you take the constant unease in his soul as a form of comeuppance.

These characters are explicitly rewarded – in some ways – for their immorality. They get away with it. Even Tony, whose fate is hinted at but never explicitly shown, gets a moment of peace before he goes. Don’s sitting there with a big old grin on his face the last time we see him. And sure, Walter gets snuffed out, but on his own vicious terms.

And so what? Are any of the creators behind these anti-heroes really suggesting that we should turn to crime or adultery? If they are, then they are not artists – they are salesmen.

Art is better when we treat it as nuanced, complex depictions that leave it to us to do the work of untangling.

Indeed, through immorality, these characters suggest that the only thing worse than these flawed and difficult characters is the world around them – the world that rewards them. It’s not Don that’s the isolated problem, cutting a swathe of heartbreak and cashing a big old cheque. It’s that the structure around him is misogynistic and capitalistic. He is the perfect product of his era. And the depiction of his moral crimes isn’t meant to encourage us to applaud those crimes. It’s meant – at least on one interpretation – to make us question the whole system that props us up.

It’s a mistake to hanker for art that only operates in one moral mode; that punishes the wicked, and celebrates the innocent. Not even fairy tales are that simplistic. We live in an era in which even our zombie TV shows are filled with nuance and complexity. Let’s engage in discourse worthy of that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 15 FEB 2023

In celebration of Sydney World Pride and Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, we’ve profiled nine notable thinkers who have contributed to our understanding of gender, sexuality and identity in some way. Whether navigating such spaces themselves or contributing to prominent research in the field, these figures have propelled public awareness of LGBTQIA+ issues in a meaningful way.

Michael Foucault (he/him)

Michael Foucault (1926-1984) was a daring, outspoken French philosopher, historian and psychologist. Much of his work was concerned with power and the random, coincidental ways in which big ideas and movements manifest in public consciousness. He explored the idea of sexuality in great extent and the modern fixation to define it and attribute sexual relations to an identity. To him, such definitions and labels effectively “other” parts of the population whose sexual behaviours are seen as deviant from the norm, even though evidence of same sex relations is present throughout human history.

Foucault thoroughly explored these ideas in his study, The History of Sexuality. He did not believe sexuality could be definitively defined – and any attempt to define it, in his eyes, constrained the mobility of human sexuality, which he believed ought to be fluid. Foucault’s provocative ideas and the content of The History of Sexuality laid the foundation for what Teresa de Lauretis would later call “queer theory”.

Judith Butler (they/them)

Judith Butler (1954-present) is an American activist whose writings and philosophies colour their commitment to radical equality. They are best known for writing Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, which is widely considered a founding text of queer theory. In the world-renowned book, Butler rejects the stance that gender equals biology, instead viewing gender as a product of behaviours and self-expression. To them, gender is produced by performance and is the root of their idea of “gender performativity”.

To eliminate any confusion on its definition, Butler explains that “We are formed through gender assignment, gender norms and expectations. But we’re not trapped. We can work and play with them [and] open-up spaces that feel better or more real for us.”

Audre Lorde (she/her)

Professionally a poet, professor and philosopher, Audre Lorde (1934-1992) also proudly carried the titles of intersectional feminist, civil rights activist, mother, socialist, “Black, lesbian [and] warrior.” She is also the woman behind the popular manifesto “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Lorde’s self-expression and personal philosophy has became one of the greatest contributions to the discourse on discrimination and equality today. By offering an authentic depiction of the female, queer and Black experience, she portrayed the good, the bad and the complex. She felt academic discourse on feminism was white and heterosexual centric, lacking consideration of the lived realities so she put the stories of these women at the centre of her literature. An advocate for difference amongst human beings, Lorde’s difference was key to helping eradicate discrimination and moving forward in unity.

Raewyn Connell (she/her)

Raewyn Connell (1944-present) is an Australian sociologist. Born in Sydney, she approaches her research work with what she calls “southern theory”. Essentially, this perspective gives space to the global south’s backgrounds, which are often overshadowed by northern narratives. Connell was initially recognised for her research on class dynamics, exploring how class and power are inextricably linked and thus defined class as a social structure. This social framework propelled Connell into the realm of sexuality, which she also viewed as a social structure. Exploring how class influences and shapes gender, she understood gender as multi-dimensional and subject to change; something far beyond a mere aspect of our social identity.

In Masculinities – one of her most famous works — Connell coined the term “hegemonic masculinity”, which is the most dominant and socially celebrated version of a man. Though best known for her work in male studies, she explained that “my theoretical concern was the gender order as a whole; masculinity was one piece of the jigsaw”. Additionally, she’s written about her experience as a trans woman, gender equality, poverty, AIDS prevention and education.

Dennis Altman (he/him)

Dennis Altman (1943-present) is an Australian queer thinker and professor of politics at La Trobe University. His 1971 book, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation, kickstarted his outstanding career that eventually led The Bulletin to name him one of the 100 most influential Australians. He primarily pondered the differences between radical gay activists who question heteronormative frameworks versus the tamer gay equality activists who demanded space in such frameworks. As time went on, Altman’s predictions of the normalisation of homosexuality laid out in his 1971 book proved correct. And though such advancements are certainly ones to celebrate, part of Altman mourns the radical roots of gay liberation.

For his complete support of gay rights, his opposition of same sex marriage might come as a surprise, but not if you consider the fact that he opposes marriage of any kind. In rejecting “the assumption that there is only one way of living a life”, Altman never married his partner of twenty years. He vehemently stands by the “equal right not to marry” and refuses to seek permission from the state and religious bodies that don’t want to sanction same sex relationships.

Susan Sontag (she/her)

Susan Sontag (1933-2004) was a relentless and prolific writer, philosopher, playwright, filmmaker and activist. She obsessively pursued the truth and had the courage to express it, no matter how unpalatable. To her, “All understanding begins with our not accepting the world as it appears.” Sontag’s first notable work, Notes on “Camp”, is what propelled her into the public eye, especially after it appeared in Time Magazine. Best known for detailing modern culture and aesthetics, her work expanded definitions of the word “camp” – for instance, using it to define works of art when they fail at being serious.

Her extremely publicised divorce from sociologist and cultural critic Philip Rieff in 1957 forced her into the public eye and involuntarily exposed her sexuality. Rather famously, after that event, she never formally came out as lesbian or bisexual. On this, in an interview with the New Yorker, she said, “That I have had girlfriends as well as boyfriends is what? Is something I never thought I was supposed to say since it seems to me the most natural thing in the world.”

Natalie Wynn (she/her)

Natalie Wynn (1988-present) is an American, Baltimore-based YouTube personality whose work aims to educate via theatrical entertainment and humour. In a play-like fashion, Wynn plays different characters and wears complex costumes to try and voice all sides of an issue, from which the audience can draw their own conclusions. On her channel, ContraPoints (like counterarguments), she tries to make people think; and beyond that, she wants them to question why they think that way in the first place. Wynn questions, “What matters more: The way things are or the way things look?”

As a transgender woman, many of her videos tackle trans experience, sexuality and gender roles. Wynn principally tries to depolarise conversations that typically divide people and humanise those who are questioning their own identity and sexuality. She claims that “in a free society, different people will have lots of different sexual lifestyles,” and she uses her platform to give space to such lifestyles.

Masha Gessen (they/them)

Masha Gessen (1967-present) is an unreserved, influential journalist, activist and author. Born in Russia, they relocated to America to realise greater sexual freedoms. Called “Russia’s leading LGBT rights activist” they have candidly discussed living in Russia as an openly gay person at the time – where homosexual propaganda is illegal and removing children from same sex households is possible.

Gessen has brought international queer issues into academic discourse to better understand the anti-queer movement, like that in Russia. They’ve blatantly critiqued Russia’s president Vladimir Putin since he was first elected and holds that former American president Donald Trump is “worse” than him. Gessen continues to expose injustices and Russia’s rise of LGBTQIA+ hate crimes in the wake of the state’s homophobia.

Alok Vaid-Menon (they/them)

Alok Vaid-Menon (they/them) is an internationally acclaimed writer, comedian, poet, and public speaker whose work explores themes of trauma, belonging, and the human condition. Their 2020 book Beyond the Gender Binary has been described as a “clarion call for a new approach to gender in the 21st century.”

Their approach to fundamental and often violent clashes with peace and compassion can feel radically hopeful. Vaid-Menon says “I’m fighting for trans ordinariness… I want to be able to walk down the street wearing what I want without it having to be an event.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On policing protest

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 9 FEB 2023

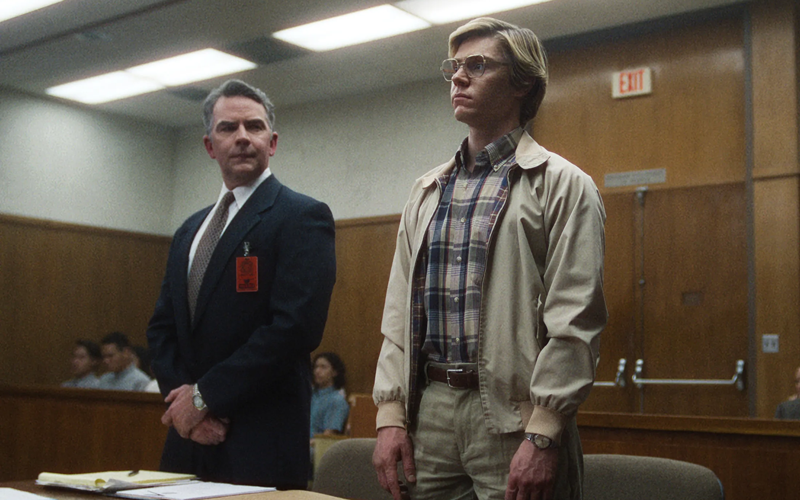

In January 2023, actor Evan Peters took to the stage to accept a Golden Globe for his performance as Jeffrey Dahmer in the surprise streaming success Monster – The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

It was a moment of odd contrast. There was Peters, dressed in a Dior suit, surrounded by opulence of the highest order and luxuriating in the most comfort and security imaginable — rich, safe, protected — accepting an award for his portrayal of a serial killer. More than that, the families of Dahmer’s victims were nowhere to be seen. As the actor collected the gong, those whose lives had been forever shaped by the crimes of a serial killer — second-order victims, whose narratives had been used for art — were off-screen.

It was a moment that crystalised the strangeness of our modern obsession with true crime, an obsession that is taking over the entertainment industry, and swamping podcast feeds and our small screens. In swathes of the Western World, we are safer than ever before from the threat of another Dahmer — and yet, in our post-Making A Murderer world, ripped from the headlines stories of violence and immorality are everywhere, even as such experiences are becoming, for most of us, as alien as stories set on Mars.

And such stories have real-life victims who are still with us; still alive, and in many cases, still grieving. These people who deserve emotional security are being ignored and overwritten by Hollywood.

Why then can’t we get enough of Ed Gein, and Ted Bundy, and the mountain of murderers that fill up our screens? What are the ethics of engaging with these traumas casually, over dinner, or on our way to work? And what can we do to make this immensely popular sub-genre genuinely ethical?

Why Are We Getting Off On Murder?

It would be wrong to suggest that our current moment of true crime consumption is a total deviation from past trends. Stories of horror and amoral behaviour have been with us since at even earlier than the time of the Brothers Grimm — most oral storytelling revolved around bloodshed, deviants, and murder.

It would also be wrong to suggest that true crime is an empty or useless art form. Art is therapeutic because it allows us to explore and imagine heinous violence and immorality from the safety of our homes. It’s a tool for processing collective fear; collective horror. It’s a way for us to explore how we feel about our own moral systems, by examining the lives and actions of those who deviate from those systems.

However, it’s the “based on a true story” tag that makes true crime distinct. It is hard to imagine that Monster would have the same impact on the mass culture if it was a total fiction. The “true” in “true crime” is part of the sell.

Engaging in the world of true crime means engaging in a world where serial killers lurk around every corner. For those of us living in cities in the Western World, that is far from true. Serial killers were always the aberration to the rule. Now, they’re positively alien — in the U.S., serial crime makes up less than one percent of all crimes recorded. For those of us with class privilege, our deaths will come, most likely, from heart disease, not a sociopath in oversized glasses who will later mummify our heads.

Why true crime has blossomed in the context of these cultural shifts is hard to say. Could it be a result of the passivity baked into entertainment these days? So much of us binge shows to tune off, switch out, and relax on the couch. True crime is excitingly different. Podcasts like My Favourite Murder, or smash hits like Making A Murderer gives audiences an opportunity for further engagement that extends after the credits roll. You can read Wikipedia pages. You can listen to more podcasts; watch spin offs; read testimonies. And that means you can become a sort of detective of your own, sniffing out leads, becoming not just a watcher, but a researcher.

Blood On Whose Hands?

The cultural context for our obsession with true crime adds a string of ethical dilemmas to consuming it. For a start, our obsession is coming a time where we are more able than ever to educate ourselves on the crooked and fundamentally broken nature of the police force. Most true crime is ‘copaganda’, saturating the populace with the myth that most police officers are inventive, savvy artists stringing together clues, rather than overfunded, inadequate mental health professionals at best, and the violent arm of the state at worst.

True crime also plays uncomfortably into pre-existing racial divides. In most true crime shows produced in the United States, Australia and the UK, the victims come from ethnic backgrounds that are not white. The cops, by contrast, are white. The looming threat of the white savior narrative is thus unavoidable. Just as problematically, race is an unspoken presence in most true crime, rarely acknowledged, and glossed over by artists in favour of the flashier, gorier elements of these stories.

Finally, real-life crime means real-life victims. Dahmer’s victims have children; friends. These crimes leave intergenerational traces – there is a legacy of pain that drips down bloodlines after a life is cruelly and inhumanely snuffed out. Not only have these second-order victims lost a loved one, they’ve seen that loved one turned into newspaper headlines and bit players in a swathe of miniseries and podcasts.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families. The reason for this responsibility is two-fold. Firstly, these stories would, devastatingly, not have happened were it not for the victims. In the worst, most painful way, Dahmer was who he was because of the people he killed. His story is their story, and any Hollywood creative who tells that story and makes a dime is profiting off the pain of victims. Ryan Murphy, Monster’s creator, has a net worth of $150 million. Evan Peters has a net worth of $4 million. Both have enjoyed significant financial success from Monster that the second-order victims of Dahmer have not.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families… The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment.

The pain of those whose lives were affected by Dahmer provides the second reason for the responsibility of true crime artists — these victims and their families are just that. Victims. The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment. All the award shows that Peters and Murphy get to swan about at seem actively exploitative, given the human suffering that they took from real-life, and fashioned for the screen.

The way to resolve this responsibility is proper financial remuneration. These families deserve to be compensated for their stories, and for their pain. Moreover, such an obligation extends beyond just those involved with Monster, and implicate all true art creators, no matter the medium. How often have you listened to a true crime podcast, in which a grisly murder is being detailed, only to have your experience interrupted by a jocular advert for mattresses and at-home meal kits? These moments sit the grisly murder next to the adverts that make the creators of such content wealthy – throwing into focus that the true crime industry is just that — an industry.

Sure, in a capitalist system, all art has to be commercially minded to some extent – art is expensive to make, and artists deserve to be compensated. But the integration of advertising into true crime feels particularly craven. The money must be shared. Those who deserve to be paid should be paid.

None of this is an argument for shutting down true crime art, or censoring it or banning it in any way. True crime, for its flaws, serves a purpose. It can make us think about class; about context; about law. But to be truly ethical, true crime must shift its relation to the victims who are involved in these stories. Otherwise, there’s blood on the hands of more than just the murderers.

For more insights into our consumption of true crime, tune into the FODI22 discussion, The Crime Paradox

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

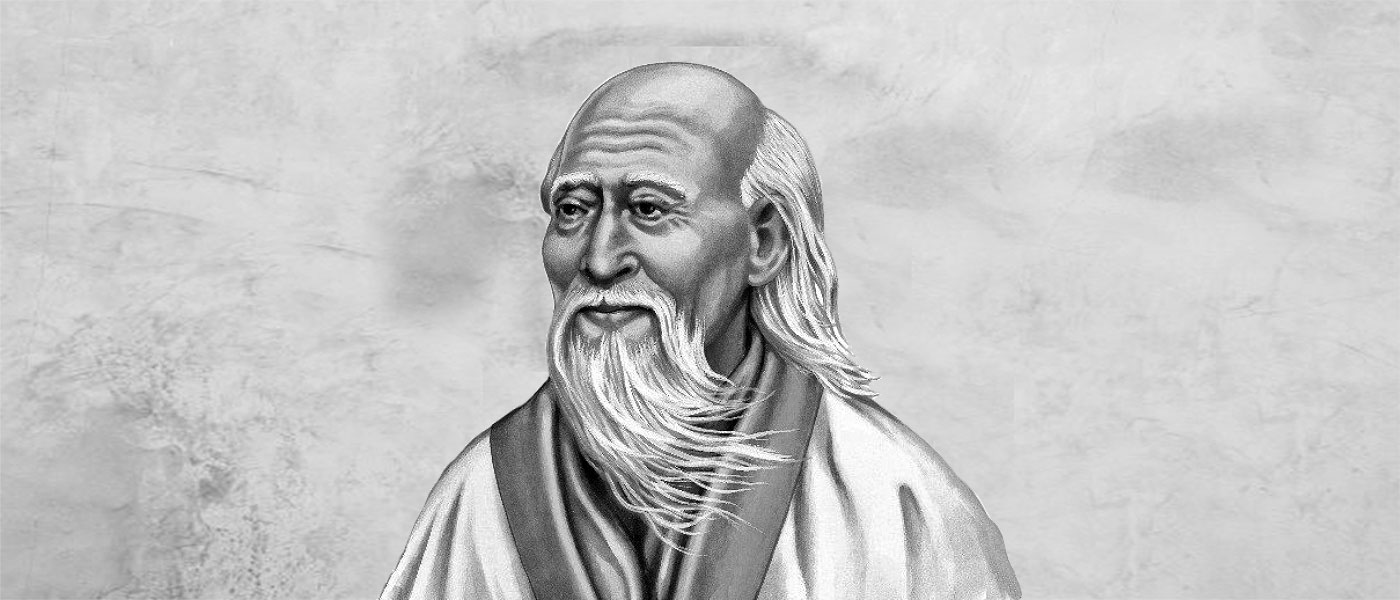

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Am I falling behind in life “milestones”?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

AI is not the real enemy of artists

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 2 FEB 2023

Artificial intelligence is threatening to put countless artists out of work. But the greatest threat to artists is not AI, it’s capitalism. And AI could be the remedy.

“Socrates taking a selfie, Instagram, shot outside the Parthenon, wearing a white toga, white beard, white hair, sunlit.” That’s all the AI image generator Stable Diffusion needed to create the cover image for this article.

But instead of using artificial intelligence, I could have hired a photographer or purchased an image from a stock library to adorn this article. In doing so, I would have funnelled money to a human, who might have spent it on something else created by another human. Instead, I used AI, and no money left my pocket to flow through the economy.

And therein lies the threat posed by artificial intelligence to artists: when AI can produce nearly endless creative works at near zero marginal cost, what will this mean for people who make a living via their artistic talents?

While people have lamented the prospect of AI destroying jobs for years, the discussion has remained largely theoretical. Until now. With the advent of generative AI tools that are readily available to the public, like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E and ChatGPT, the prospect of massive job losses in creative industries is rapidly becoming a reality. Not surprisingly, many creative workers – including artists, illustrators, photographers and copywriters – are fearful for their livelihoods, and not without reason.

If we believe that creative expression is inherently meaningful, and the works it produces are intrinsically valuable, then this assault on artists’ jobs would be a net loss for humanity. It’s one thing for machines to replace labourers on farms; it’s another thing entirely for AI to empty studios of artists.

But despite all the lamentations about the impact of AI on art, when I dug deeper, I realised that it’s not really AI that poses the greatest threat to art. It’s capitalism. And instead of AI accelerating the decline of art, it could actually be the key that unshackles us from our current form of scarcity capitalism and allows art to genuinely flourish.

The alienation of art

As soon as art is brought into the market, it changes. Instead of a work’s value being defined in terms of its meaning or cultural significance, it becomes defined in terms of how much someone else is willing to pay for it. Art effectively becomes a product to be bought and sold.

Given the cost of producing art – and by “art” I mean all modes of creative expression, including music, dance, poetry, fiction, etc. – and the necessity of earning money to exchange for other goods, then art necessarily becomes professionalised.

This creates distinctions between different categories of artist. One is between those who create art for fun, so-called ‘amateurs’ (from the Latin amare, meaning “one who loves”), and those who create art for money, whom we can call ‘professionals’. The latter group, and society in general, tend to look down upon amateurs as engaging in art only frivolously or lacking the talent to make it in the competitive market.

The other distinction is among professionals, and is between those who work as commercial illustrators, designers, photographers, musicians, copywriters, etc., and the very small subset of their number, whom we might call ‘purists’, who are skilled or lucky enough to be able to produce the art they want, and can make a living out of it, either through selling to enthusiasts or collectors, or by securing grants. The purists, in turn, tend to look down on professionals as being sell-outs, or lacking the talent to make it in the rarefied art world.

The capitalist dynamic that produces these distinctions has the unfortunate consequence that many people choose not to create art at all, either because they don’t believe they are skilled enough to compete in the market, as if that were the only standard by which one might be measured, or they consider amateur art to be less than worthy. As a result of the commercialisation of art, there are likely many fewer painters, dancers, musicians and poets, than there might otherwise be.

Who’s under threat?

It’s important to recognise that when it comes to AI, it’s primarily the professionals who are at risk. These are the artists who produce the kinds of products that AI is increasingly able to create at lower cost.

AI doesn’t appear to present much of threat to purists, given that grant-givers and collectors are often spending based on the name in the corner as much as the other marks on the canvas, as it were. Purists can also do something that AI can’t: translate their personal experiences into creative expression. Amateurs are also not much at risk from AI because they don’t, for the most part, seek to derive an income from their works.

If we focus on professionals, we can see something else that the commodification and professionalisation of art have done: alienate the artist from their work.

Professionals often work to a brief defined by another person. Their art is often a means to a commercial end, such as capturing a prospective customer’s attention with a graphic or jingle, or by gussing up the interior of a restaurant. Some of this work can be deeply meaningful and rewarding, but much of it is far removed from what the artist would otherwise create were they not in dire need of money to pay the bills.

As one commenter on YouTube remarked: “As an artist I’m constantly conflicted with needing to make art that has ‘market value’ and can be sold to someone to financially support myself, and just making art for art’s sake because I want to make something that I like, and to express myself through the power of creativity.”

This alienation of the artist from the work they genuinely wish to produce has been discussed at length as far back as by Karl Marx. It’s also the reason why Pablo Picasso joined the Community Party.

It means that much of the art produced by professionals is, by its commercial nature, also helping to reinforce the very commercial system that binds it. This undermines one of the core social functions of art, which is to be a form of political expression, often employed to highlight and challenge the power structures that stifle and oppress humanity.

From this perspective, I saw that capitalism has already made the world hostile to art. AI is just worsening the situation of those have chosen to make a career out of their artistic talents.

AI acceleration

I can see two bad responses to this situation. The first is to attempt to stuff the AI genie back in the bottle. Some are attempting to do that right now, primarily through a series of court cases against some of the major generative AI companies under the pretence of copyright violation.

The outcome of these cases (assuming they are not settled or dismissed) will likely have a tremendous impact on the future of generative AI. However, it’s far from clear that US copyright law, where the cases are being held, will find that generative AI has done anything illegal. At best, the courts might require that artists are able to opt-in or opt-out of the datasets used to train AI. But even that seems unlikely.

The second bad response is to let AI run unfettered within the current economic paradigm, where it could destroy more jobs than it creates, put millions of professional artists out of work, and concentrate wealth and exacerbate inequality to an unprecedented degree. Should that happen, it’d create a genuine dystopia, and not just for artists.

The good news is that I can see at least one good solution. This is to leverage the power of AI to dramatically boost productivity and lower costs, and use that new wealth to improve everyone’s lives through a mechanism such as a universal basic income, greater subsidies or public funding, a shorter working week or a combination of them all.

I’m not alone in endorsing this idea about transforming capitalism. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, which created ChatGPT and DALL-E, has argued something very similar in an essay called Moore’s Law for Everything. In it, he states that “we need to design a system that embraces this technological future and taxes the assets that will make up most of the value in that world – companies and land – in order to fairly distribute some of the coming wealth. Doing so can make the society of the future much less divisive and enable everyone to participate in its gains.”

This would likely be a multi-decadal project, but it would set us on a course that would decouple the work that we do from the income that we earn. This could release artists from the shackles of capitalism, as they’ll be increasingly able to produce the art that is meaningful for them without requiring that it be saleable in a competitive market.

It’d also free up more time for amateurs to explore their creative potential, possibly resulting in an explosion of art. Imagine how many people would pick up a paintbrush, pen or piano if they had the time and financial security to do so.

Much of that creative output will be low quality, but that’s not the point. If we believe that the creative act is inherently valuable, then it’s worth it. Plus, there are likely many people of startling artistic talent who are currently otherwise occupied earning a living to be able to explore and develop their abilities.

The decoupling of art from the market could also help liberate its political power, enabling more artists to question, challenge and offer solutions to society’s many problems without having their livelihood threatened.

The big question is how do we get from a world where AI is stripping people of their livelihoods to one where AI is freeing them from toil? There are no easy answers to that question. But it’s crucial to focus our attention on the root cause of the problem that artists face today, and that’s not AI, it’s capitalism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 22 DEC 2022

One surprising fact about Mike White, the creator, writer and director of HBO’s The White Lotus, is that he’s obsessed with and starred in a season of Survivor, the brutal reality TV show that pits strangers against each other in a complex game of wits and skill.

Of course White’s a Survivor junkie. The two seasons of The White Lotus – a soap opera-cum-murder mystery about a bunch of depraved rich people who exploit the surplus of expendable workers who man the titular hotel they stay at – are united by their fixation on the ways human beings outwit and outgame each other.