Ethics on your bookshelf

Ever wondered what we’re reading over at The Ethics Centre? Well here’s your chance! We asked some of our thought leaders for their best ethical reads this year.

She Who Became the Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan

To take a break from reading so much non-fiction in prep for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, our FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey returns to her first love – fantasy. This re-imagining of the rise to power of the Hongwu Emperor in 14th century China combines gender, rebellion, power and faith in a powerful and fun novel.

Exhalation by Ted Chiang

Our Senior Philosopher, Dr Tim Dean recommends this startling collection of science-fiction short stories, which is as philosophically stimulating as it is deeply engaging. Chiang is one of those precious few writers who genuinely groks both science and philosophy, and does both of them justice without compromising creativity or narrative. His ‘what if’ worlds are plausible and provocative, exploring themes like freedom, fate, existentialism, memory and moral responsibility.

How to be Perfect by Michael Schur

Whether you’re a philosophy buff or you have no idea who Plato is, our Youth Coordinator and philosopher, Daniel Finlay says Schur’s writing will have you laughing, learning, thinking and reflecting all at once. This is an engaging and entertaining introduction into lots of aspects of moral philosophy, with plenty of anecdotes and comparisons to keep you from feeling like you’re in school.

Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

Making decisions we can be proud of means that sometimes we need to do things we don’t want to or have the patience for. After reading Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus, our Director of the Ethics Alliance and the BFO, Cris Parker realised how easily we can be distracted, how desperately we can crave reward and that how the technology we take for granted is contributing to this. Stolen Focus identifies the ways we can lose our capacity to make choices and provides techniques to change that. The challenge for us now is actually implementing them!

The March of Folly by Barbara Tuchman

Our Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff says in exploring some of the worst decisions made in human history, The March of Folly reveals the root cause that lies in one of the great enemies of ethics – the baleful effects of unthinking custom. In this historical survey, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Barbara W. Tuchman grapples with the pervasive presence through the ages, of failure, mismanagement, and delusion in government.

John Ashbery, Collected Poems 1991-2000

Philosopher and Ethics Centre Fellow, Joseph Earp doesn’t think that ethical education is complete without poetry, nor is poetry complete without John Ashbery. Ashbery is a strange, elliptical writer, who fosters attention, and shows us the rewards of paying attention. Which is where the ethics of it all comes in – what is the ethical life, if not one where we pay attention?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 4 NOV 2022

In 2021, the star of the US iteration of The Bachelorette, Katie Thurston, made international news off the back of one thirty second clip. In it, Thurston, all smiles and fey giggles, announced that she was forbidding the male contestants searching for her endless love from masturbating.

“I kind of had this idea I thought would be fun, where the guys in the house all have to agree to withhold their self-care as long as possible, if you know what I mean,” Thurston told the show’s two hosts, to a great deal of laughter and blushing. What was she was doing was what Bachelorette stars – and indeed many of those who feature in that brand of modern reality television focused on love and sex – have done for years.

Namely, she was upholding the show’s characteristic, and very strange, mix of euphemism and the explicit stating of norms that are so well-trodden in the culture that they’re not even acknowledged as norms at all.

Indeed, the most surprising thing about the clip was that it generated chatter, from both mainstream outlets and social media, in the first place. The Bachelorette’s habit of not so much ignoring the elephant in the corner, but ignoring the corner, and the walls connected to the corner, and perhaps even the entire room, has been part of its fabric from its very conception.

This is a show ostensibly about desire and love – which is a way of saying that it is about different states that circle around, and often lead to or follow from, sex – that shirks desperately away from most of the ways that we understand these things.

All we get on the desire front is a lot of people who pay a certain kind of attention to their bodies, occasionally – extremely occasionally – kissing one another. And all we get on the love front is a lot of talk about forever and eternity, along with roses, champagne flutes, and tears. Sex, meanwhile, lies far beyond the show’s window of acceptable or even conceivable behaviours. It’s there but it’s not there, a part of the very foundation of the show that’s still so taboo that if someone dares speak it aloud, as Thurston did, they’ll be the odd one.

This backlash to a bizarre norm constructed and maintained by the cameras was taken to an extreme in the case of Abbie Chatfield, a contestant on the Australian version of the show. For daring to tell Bachelor Matt Agnew that she “really wanted” to have sex with him, and admitting that she was “really horny”, Chatfield drew ire from not only the usual anti-sex bores, but from the so-called “sensible mainstream centre.” She was called a slut; her behaviour designated outrageous.

Such a backlash wasn’t just a policing of women’s bodies, though it was that. It was also a policing of the very standards of desire, part of a long attempt to prettify and clean up matters of sex and love, into “good” (read: socially acceptable) talk about these matters, and “bad” (read: unhinged, dangerous, impolite) talk about them.

In a society with a healthier understanding of sexuality, Chatfield wouldn’t be the deviation. The whole strange apparatus around her would be.

Whose Normal?

What makes The Bachelor and The Bachelorette such fascinating, internally frustrated objects is that their restating of the normal reaches such a volume, and resists so many specifics, that it reveals how utterly not-normal, arbitrary, and ill-defined most normal stuff is.

For instance, there is much talk in The Bachelor and The Bachelorette about romantic “compatibility”, a bizarre standard frequently talked about in the culture without ever being actually, you know, talked about. On this compatibility view of love, the pursuit of a significant other is a process of finding someone to fit into your life, as though you have one goal for how you want to be, and only one person who can help you achieve that. It’s that popular meme of the human being as an incomplete jigsaw puzzle, picking up pieces, one by one, and trying to slot them in.

What The Bachelor and The Bachelorette usually reveal, however, is that actually working out who is “the one” for you is much more difficult than the show’s own repeated emphasis on compatibility implies.

The stars of these shows frequently love and desire multiple people at the same time – the entire dramatic tension of the show comes from their final selection of a partner being surprising and tense.

If this compatibility stuff was as simple as it often described – or even clearly explicated – then we’d know after thirty seconds spent between potential two life partners that they’d end up together. There’d be no hook; no narrative arc. Eyes would lock, hearts would flutter, and the puzzle piece would just slot in.

In actuality, on both of these shows, the decision to pick one person over another frequently feels deeply random, and the always vague star usually has to blur their explanations even further into the abstract to justify why they want to be with him, and not with him, or with him.

The Bachelor and The Bachelorette are supposedly triumphant testaments to monogamy – almost all seasons of the show, except the one starring Nick Cummins, the Honey Badger, end with two and only two people walking off together.

But actually, in their typically confused way, they also end up explicating the benefits of polyamory. Often, the stars of these shows have a lot of fun, and derive a lot of pleasure and purpose from being intimate and romantic with a number of people at the same time. When it comes time to choose their “one”, it is frequently with tears – on a number of occasions, the stars have said, in so many words, “why not both?”

Get Those Freaks Away From Me

And why not both? Or more than both? The season of The Bachelor where no contestant is eliminated, everyone goes on dates together, and they all end up having sex and falling in love with one another, is no stranger than the season where only two walk into the sunset.

Monogamy is a norm, which is to say that it is an utterly arbitrary thing spoken loudly enough to seem iron-wrought. Norms are forceful; they tell us that things are the way they are, and could be no other way. In fact, they are so forceful that they have to state not only their own definitional boundaries, but also the boundaries of the thing that they are not – not just pushing the alien away, but the very act of designating things alien in the first place.

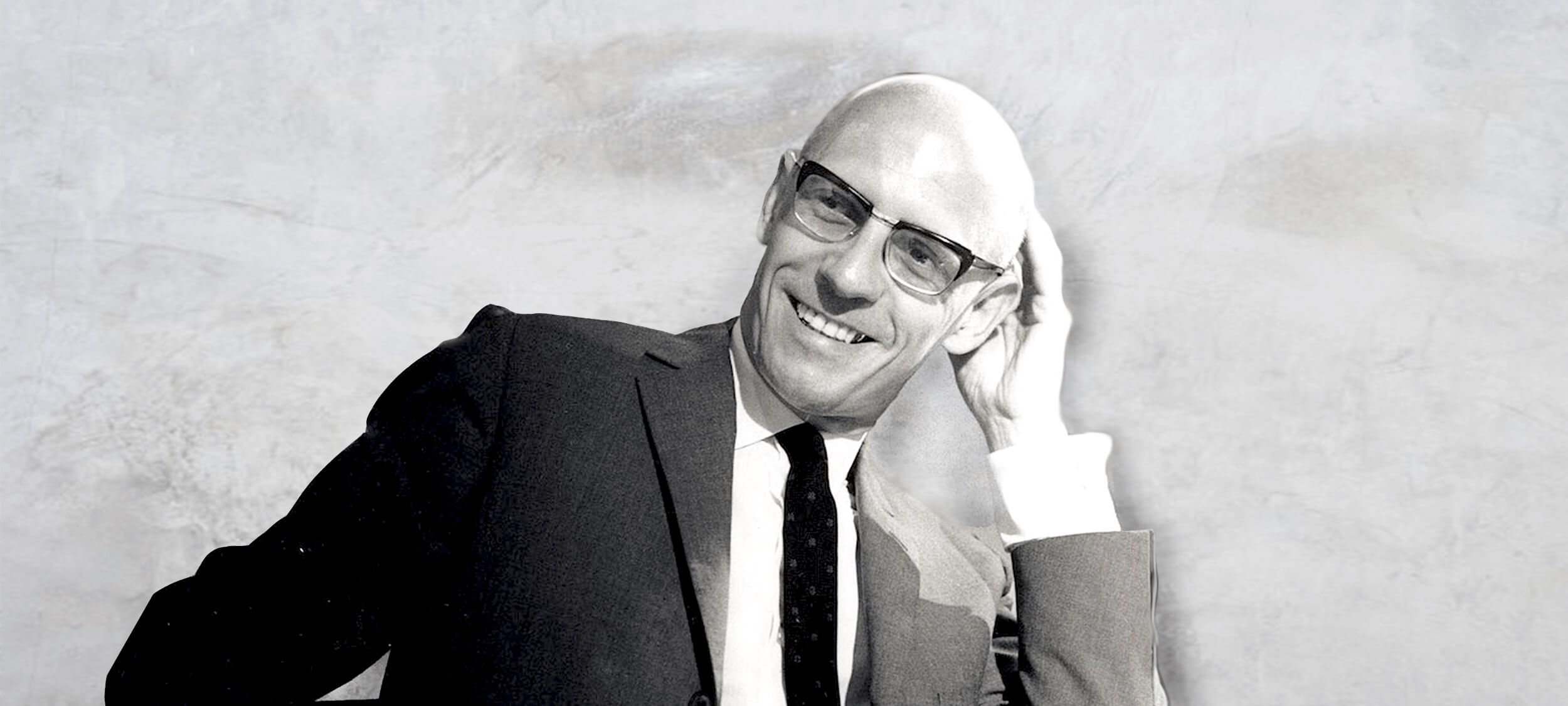

It was the philosopher Michel Foucault who noted this habit of branding certain objects, habits, or people as “other” in order to better understand and designate the normal. The Bachelor and The Bachelorette do this both frequently and implicitly, never drawing attention to the hand that is forever sketching abrupt and hurried lines in the sand.

Just consider the things that would be astonishing in the shows’ worlds, without even having to be taboo. For instance, imagine a star being perfectly happy committing to none of the contestants, and merely having sex with a few of them, one after the other. Or a star choosing a contestant but, rather than speaking of their flawless connection together, emphasising “mere” fun, or “mere” pleasure.

None of the preceding critique of these shows is a call to eradicate romantic and sexual norms altogether, if such an definitional cleansing were even possible. We have to make decisions about how we navigate the world together, and norms become a shorthand way of describing these decisions. What we should remember throughout, however, is that we are free to change this shorthand up whenever we like. And more than that, we should resist, wherever possible, the urge to create the other.

After all, if The Bachelor and The Bachelorette tell us anything, it’s that those regular folks are the real sickos.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

I'd like to talk to you: 'The Rehearsal' and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 6 OCT 2022

Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, perhaps one of the slipperiest works of modern television, aims to solve a very complex, deeply recurrent problem: how do we navigate our interpersonal relations, which are ever-changing, and filled with opportunities to let people down and harm those we love?

In the show, which constantly blends the real with the fake, the documentary with the theatrical, the off-kilter comedian Nathan Fielder’s solution is supposedly simple: he finds people who are preparing to have difficult conversations with friends and loved ones, and gives them the opportunity to rehearse these encounters ahead of time.

The idea behind this ridiculous, though oddly logical practice is thus: if these people have already rehearsed an uncomfortable exchange with a loved one, then they can predict for every variable. They can polish their approach. When conversations branch off into different directions, they will have accounted for that branching already, leaving them to always choose the best, most impactful response.

To aid his mentees in this practice, Fielder uses an ever-escalating series of interventions. He creates dialogue flow trees, in which conversations can be unveiled in their full myriad of possibilities. He stages strange obstructions, ranging from fake babies to simulated drug overdoses. He takes the joyous chaos of being what Jean-Paul Sartre called “a thing in a world” – an agent who is perceived by other agents, and whose actions affect them – and he tries to simplify it.

Saying The Rehearsal is definitively “about” anything is a mistake – it’s too ever-changing, too messy, for that. But certainly, in its focus on trying to do the right thing by simplifying a complex world so that it might be predicted, the show can serve as a model of the pitfalls of trying to rationalise and generalise. It is a warning to those philosophers from the analytic tradition who reduce a world that is precisely so joyous and beautiful because it is so chaotic. So complex. And so filled with the potential for harm.

Fielder’s methods for helping people confront their own mistruths, find love, or fit better into their communities, are guided by the principle of a kind of lopsided rationality. The methods are laughable, of course – Fielder is a comedian. But they follow a strict, internally coherent form of thought.

In essence, what Fielder tries to do is generalise. He takes the nuances of life’s difficult conversations, and he strips them down to their component parts – maps them out on a board, uses actors to play them out ahead of time.

For instance, in the show’s first episode, Fielder recruits Kor, a competitive and trivia-obsessed young man who is preparing to tell his close friends that he has lied for years about getting a master’s degree. Fielder hires an actress to play Kor’s most abrasive friend, gets that actress to uncover as much information as possible about the real person she is stepping into the shoes of, and then puts Kor and this performer in a set that precisely replicates the dimensions of the bar where the actual conversation will go down.

The method – reduce. Simplify. Abstract. And use that generalised version of a real-life situation to guide how the actual situation will play out. This kind of ethical reasoning is highly tempting to us. We often find ourselves drawn to it, as we move through our lives.

Sure, we might not go to the lengths that Fielder does in The Rehearsal. But we do practice tough conversations in the shower with ourselves, ahead of time. We draft and re-draft text messages, and base them on how we might imagine the person we send them to will respond. In essence, we use our “rationality” and “reason” to help us move through the world, drawing on past experiences to help us navigate future ones.

Trivia-obsessed Kor, in fact, is a specific example of this. He is most worried about revealing his deception to his abrasive friend because of how she’s behaved in the past. He rationalises that because he has seen her blow up at others, getting angry at the drop of a hat, that she’ll do the same in the future, and more specifically, do it to him. He starts with a real-world experience – incidents of her temper – and then generalises them to a rule – she will always get angry – using his rationality to try and deduce the future, and thus the best action.

But what this kind of rationality does not take into account is the way that human beings shift and change; the way that they surprise us. How often have we prepared for an outcome that hasn’t come to light? Stressed about confrontations that turn out not to be confrontations at all?

Rather than generalising away from the inherent changeability of those we love, or indeed any of those who we surround ourselves with, we should instead embrace what the philosopher Jurgen Habermas described as “communicative rationality.”

For Habermas, our rational faculties shouldn’t generalise us away from the world – they shouldn’t isolate us. Instead, they should be part of a process of “achieving consensus”, as Habermas put it. We make decisions with other people. While staying in contact with them.

This means, rather than being a witness to the world – viewing it and then reviewing it, and using what we see and learn to guide our ethics – we are an active participant in it. On this model, our thoughts, desires, and ethical behaviours are essentially collaborative. They are grounded in the real world, and the people around us.

Thus, on Habermas’ view, we never stop discussing, talking, engaging. We don’t do as Kor does – using his rationality to effectively step himself away from his abrasive friend, halting in the process of communicating with her. And we don’t do as Fielder does – creating an artificial replica of the world, rather than just living in the actual world.

When we take the Fielder method, instead of adopting Habermas’ position of making everything communicative, we lose that which makes the world what it is: its messiness, its changeability, its dynamic and fluid nature.

There is nothing logically wrong, broadly speaking, about the kind of rationality that involves a step away from the world – that leads us to run through possible outcomes in our head with ourselves. Difficult conversations do move through different points; do branch off. So it makes some kind of sense to imagine that we should be able to predict them. The error here is not one in internal consistency. The error is taking a step backwards from those around us when trying to work out what to do, rather than taking a step forward.

The joke of The Rehearsal is precisely that this internally consistent form of rationality is remarkably, laughably devoid of life. It’s cold. Alien. It aims to solve real world problems, but it does that by turning to a printed board of branching lines of dialogue, instead of other human beings.

And it’s not even useful. As it turns out, Kor, who is highly nervous about the encounter with his abrasive friend, has little to worry about. When he confronts her, rather than the actress he has been rehearsing with, she is largely unfussed. She doesn’t mind that Kor has misrepresented himself. She expresses understanding for his duplicity. It is all pretty chill. Laughably so, in fact.

What Kor shows us is the importance of remaining in the world. That means we might fail them – that we might do the wrong thing. But that’s better than hiding away in a world of Fielder’s whiteboards. Indeed, our failures tell us that we’re human, bungling from one awful mistake to another, trying, and then failing, and then, beautifully, trying again. Guided always by people. Living always in communities. Staying blissfully, painfully connected.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

WATCH

Relationships

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

Big thinker

Relationships

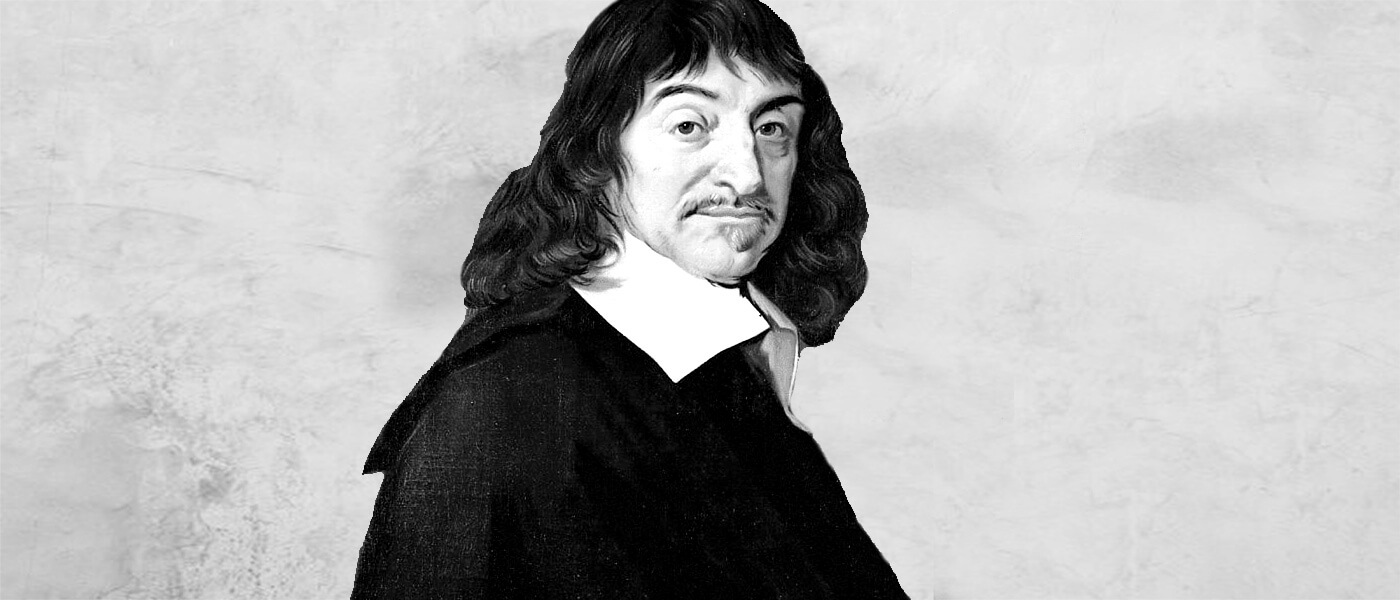

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2022

Crime, culture, contempt and change – this year our Festival of Dangerous Ideas speakers covered some of the dangerous issues, dilemmas and ideas of our time.

Here are 5 things we learnt from FODI22:

1. Humans are key to combating misinformation

Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen says the world’s biggest social media platform’s slide into a cesspit of fake news, clickbait and shouty trolling was no accident – “Facebook gives the most reach to the most extreme ideas – and we got here through a series of individual decisions made for business reasons.”

While there are design tools that will drive down the spread of misinformation and we can mobilise as customers to put pressure on the companies to implement them, Haugen says the best thing we can do is have humans involved in the decision-making process about where to focus our attention, as AI and computers will automatically opt for the most extreme content that gets the most clicks and eyeballs.

2. We must allow ourselves to be vulnerable

In an impassioned love letter “to the man who bashed me”, poet and gender non-conforming artist, Alok teaches us the power of vulnerability, empathy and telling our own stories. “What’s missing in this world is a grief ritual – we carry so much pain inside of us, and we have nowhere to put the pain so we put it in each other.”

The more specific our words are the more universally we resonate, Alok says, “what we’re looking for as a people is permission – permission not just to tell our stories, but also to exist.”

3. We have to know ourselves better than machines do

Tech columnist and podcaster, Kevin Roose says “we are all different now as a result of our encounters with the internet.” From ‘recommended for you’ pages to personalisation algorithms, every time we pick up our phones, listen to music, watch Netflix, these persuasive features are sitting on the other side of our screens, attempting to change who we are and what we do. Roose says we must push back on handing all control to AI, even if it’s time consuming or makes us feel uncomfortable.

“We need a deeper understanding of the forces that try to manipulate us online – how they work, and how to engage wisely with them is the key not only to maintaining our independence and our sense of selves, but also to our survival as a species.”

4. We can use shame to change behaviour

Described by writer Jess Hill as “the worst feeling a human can possibly have”, the World Without Rape the panel discuss the universal theme of shame when it comes to sexual violence and its use as a method of control.

Instead of it being a weight for victims to bear, historian Joanna Bourke talks about shame as a tool to change perpetrator behaviour. “Rapists have extremely high levels of alcohol abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame… if we have feminists affirming that you ought to feel shame then we can use that to change behaviour.”

5. Reason, science and humanism are the key to human progress

Steven Pinker believes in progress, arguing that the Enlightenment values of reason, science and humanism have transformed the world for the better, liberating billions of people from poverty, toil and conflict and producing a world of unprecedented prosperity, health and safety.

But that doesn’t mean that progress is inevitable. We still face major problems like climate change and nuclear war, as well as the lure of competing belief systems that reject reason, science and humanism. If we remain committed to Enlightenment values, we can solve these problems too. “Progress can continue if we remain committed to reason, science and humanism. But if we don’t, it may not.”

Catch up on select FODI22 sessions, streaming on demand for a limited time only.

Photography by Ken Leanfore

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Explainer

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 29 AUG 2022

Truth, trust, tech, tattoos and taboos – The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns live to Sydney 17-18 September with big ideas, dicey topics and critical conversations.

From history and science, to art, politics, and economics, FODI holds issues up to the light – challenging, celebrating and debating some of the most complex questions of our times.

In partnership with Gleebooks, these 10 reads from this year’s line-up of thinkers, artists, experts and disruptors will sharpen your mind, put your mettle to the test and help you stay ahead of the discussion:

Beyond the Gender Binary by Alok Vaid-Menon

Talking from their own experiences as a gender non-conforming artist, Alok Vaid-Menon challenges the world to see gender in full colour.

Alok // Live at FODI22 // Beyond the Gender Binary // Sat 17 Sept // 7:15pm

Lies, Damned Lies by Claire G. Coleman

A deeply personal exploration of Australia’s past, present and future, and the stark reality of the ongoing trauma of Australia’s violent colonisation.

Claire G. Goleman // Live at FODI22 // Words are Weapons // Sun 18 Sept // 11am

See What You Made Me Do by Jess Hill

A confronting and deeply researched account uncovering the ways in which abusers exert control in the darkest, and most intimate, ways imaginable.

Jess Hill // Live at FODI22 // World Without Rape // Sun 18 Sept // 2pm

Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker

Exploring the formidable challenges we face today – rather than sinking into despair we must treat them as problems we can solve.

Steven Pinker // Live at FODI22 // Enlightenment or a dark age? // Sun 18 Sept // 6pm

Futureproof: 9 rules for humans in the age of automation by Kevin Roose

A hopeful, pragmatic vision for how we can thrive in the age of AI and automation.

Kevin Roose // Live at FODI22 // Caught in a Web // Sat 17 Sept // 3pm

Rebel with a cause by Jacqui Lambie

The Senator’s memoir that is as fascinating, honest, surprising and headline-grabbing as the woman herself.

Jacqui Lambie // Live at FODI22 // On Blowing Things Up // Sat 17 Sept // 11am

The Uncaged Sky by Kylie Moore-Gilbert

The extraordinary true story of Moore-Gilbert’s fight to survive 804 days imprisoned in Iran, exploring resilience, solidarity and what it means to be free.

Kylie Moore-Gibert // Live at FODI22 // Expendable Australians // Sat 17 Sept // 4pm

Quarterly Essay 87: The Ethics and Politics of Public Debate by Waleed Aly & Scott Stephens

In this edition of Quarterly Essay, Aly and Stephens explore why public debate is increasingly polarised – and what we can do about it.

Waleed Aly & Scott Stephens present a special edition of The Minefield live at FODI22 // Contempt is Corroding Democracy // Sun 18 Sept // 3pm

Strongmen by Ruth Ben-Ghiat

A fierce and perceptive history, and a vital step in understanding how to combat the forces which seek to derail democracy and seize our rights.

Ruth Ben-Ghiat // Live at FODI22 // Return of the Strongman // Sat 17 Sept // 5pm

When America Stopped Being Greatby Nick Bryant

The history of Trump’s rise is also a history of America’s fall – not only are we witnessing America’s post-millennial decline, but also the country’s disintegration.

Nick Bryant // Live at FODI22 // American Decadence // Sun 18 Sept // 12pm

These titles, plus more will be available at the FODI Dangerous Books popup – running 10am-8pm across 17-18 September at Carriageworks, Sydney. Check out the full FODI program at festivalofdangerousideas.com

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We are pitching for your pledge

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 AUG 2022

There are certain things that some of us choose and do not choose, to tell those who we work with.

You come in on a Monday, and you stand around the coffee machine (the modern-day equivalent of the water cooler), and somebody asks you: “so, what did you get up to this weekend?”

Then you have a choice. If you fought with your partner, do you tell your colleague that? If you had sex, do you tell them that? If your mother is sick, or you’re dealing with a stress that society has broadly considered “intimate” to reveal, do you say something? And if you do, do you change the nature of the work relationship? Do you, in a phrase, “freak people out?”

These social conditions – norms, established and maintained by systems – are not specific to work, of course. Most spaces that we enter into and share with other people have an implicit code of conduct. We learn these codes as children – usually by breaking the rules of the codes, and then being corrected. And then, for the rest of our lives, we maintain these codes, often without explicitly realising what we are doing.

There are things you don’t say at church. There are things you do say in a therapist’s office. This is a version of what is called, in the world of politics, the “Overton Window”, a term used to describe the range of ideas that are considered “normal” or “acceptable” to be discussed publicly.

These social conditions are formed by us, and are entirely contingent – we could collectively decide to change them if we wanted to. But usually – at most workplaces, importantly not all – we don’t. Moreover, these conditions go past certain other considerations, about, say honesty. It doesn’t matter that some of us spend more time around our colleagues than those we call our partners. This decision about what to withhold in the office is frequently described as a choice about “professionalism”, which is usually a code word for “politeness.”

Severance, the new Apple television show which has been met with broad critical acclaim, takes the way that these concepts of professionalism and politeness shape us to its natural endpoint. The sci-fi show depicts an office, Lumon Industries, where employees are implanted with a chip that creates “innie” and “outie” selves.

Their innie self is their work self – the one who moves through the office building, and engages in the shadowy and disreputable jobs required by their employer. Their outie self is who they are when they leave the office doors. These two selves do not have any contact with, or knowledge of each other. They could be, for all intents and purposes, strangers, even though they are – on at least one reading – the “same person.”

The chip is thus a signifier for a contingent code of social practices. It takes something that is implicit in most workplaces, and makes it explicit. We might not consider it a “big deal” when we don’t tell Roy from accounts that, moments before we walked in the front door of the office, we had a massive blow-up over the phone with our partner. Which may help Roy understand why we are so ‘tetchy’ this morning. But it is, in some ways, a practice that shapes who we are.

According to the social practices of most businesses, it is “professional” – as in “polite” – not to, say, sob openly at one’s desk. But what if we want to sob? When we choose not to, we are being shaped into a very particular kind of thing, by a very particular form of etiquette which is tied explicitly to labor.

And because these forms of etiquette shape who we are, they also shapes what we know. This is the line pushed by Miranda Fricker, the leading feminist philosopher and pioneer in the field of social epistemology – the study of how we are constructed socially, and how that feeds into how we understand and process the world.

For Fricker, social forces alter the knowledge that we have access to. Fricker is thinking, in particular, about how being a woman, or a man, or a non-binary person, changes the words we have access to in order to explain ourselves, and thus how we understand things. That access is shaped by how we are socially built, and when we are blocked from access, we develop epistemic blindspots that we are often not even aware that we have.

In Severance, these social forces that bar access are the forces of capitalism. And these forces make the lives of the characters swamped with blindspots. Mark, the show’s hero, has two sides – his innie, and his outie. Things that the innie Mark does hurt and frustrate the desires of the outie Mark.

Both versions of him have such significant blindspots, that these “separate” characters are actively at odds. Much of the show’s first few episodes see these two separate versions of the same person having to fight, and challenge one another, with Mark striving for victory over outie Mark.

The forces of etiquette are always for the benefit of those in power. We, the workers at certain organisations, might maintain them, but their end result is that they meaningfully commodify us – make us into streamlined, more effective and efficient workers.

So many of us have worked a job that has asked us to sacrifice, or shape and change certain parts of ourselves, so as to be more “professional”. Which is a way of saying that these jobs have turned us into vessels for labour – emphasised the parts of us that increase productivity, and snipped off the parts that do not.

The employees of Lumon live sad, confused lives full of pain, riddled with hallucinations. The benefit of the code of etiquette is never to them. They get paid, sure. But they spend their time hurting each other, or attempting suicide, or losing their minds. Their titular severance helps the company, never them.

This is what the theorist Mark Fisher refers to when he writes about the work of Franz Kafka, one of our greatest writers when it comes to the way that politeness is weaponised against the vulnerable and the marginalized. As Fisher points out, Kafka’s work examines a world in which the powerful can manipulate those that they rule and control through the establishment of social conduct; polite and impolite; nice and not nice.

Thus, when the worker does something that fights back against their having become a vessel for labour, the worker can be “shamed”, the structure of etiquette used against them. This happens all the time in the world of Severance. As the season progresses, and the characters get involved in complex plots that involve both their innie and outie selves, the threat is always that the code of conduct will be weaponised against them, in a way that further strips down their personality; turns them into more of a vessel.

And, as Fisher again points out, because these systems of etiquette are for the benefit of the powerful, the powerful are “unembarrassable.” Because they are powerful – because they are the employer – whatever they do is “right” and “correct” and “polite.” Again, the rules of the game are contingent, which means that they are flexible. This is what makes them so dangerous. They can be rewritten underneath our feet, to the benefit of those in charge.

Moreover, in the world of the show, the characters “choose” to strip themselves of agency and autonomy, because of the dangling carrot of profit. This sharpens the satirical edge of Severance. It’s not just that the snaking rules of the game that we talk about when we talk about “good manners” make them different people. It’s that the characters of the show submit to these rules. They themselves maintain them.

Nobody’s being “forced”, in the traditional sense of that word, into becoming vessels for labour. This is not the picture of worker in chains. They are “choosing” to take the chip, and to work for Lumon. But are they truly free? What is the other alternative? Poverty? And what, actually, makes Lumon so different? A swathe of companies have these rules of etiquette. Which means a swathe of companies do precisely the same thing.

This is a depressing thought. But the freedom from this punishment lies, as it usually does, in the concept of contingency. Etiquette enforces itself; it punishes, through social isolation and exclusion, those who break its rules.

But these rules are not written on a stone tablet. And the people who are maintaining them are, in fact, all of us. Which means that we can change them. We can be “unprofessional.” We can be “impolite”. We can ignore the person who wants to alter our behaviour by telling us that we are “being rude.” And in doing so, we can fight back against the forces that want to make us one kind of vessel. And we can become whatever we’d like to be.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith 18 JUL 2022

Anyone who has sat through sex ed class in school or the workplace knows how difficult it is to discuss sexual ethics.

From puberty and relationships to consent and self-expression, our sexual experiences are so varied that it’s no small feat for our education to accommodate them all.

Here are 12 of my favourite books, tv shows and podcasts that thoughtfully consider the ethics around sex:

Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again by Katherine Angel

A critically-acclaimed analysis of female desire, consent and sexuality, spanning science, popular culture, pornography and literature.

The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan

A whip-smart contemporary philosophical exploration of how morality intersects with sex, particularly whether any of us can have a moral obligation to assist anothers’ sexual fulfilment.

I May Destroy You

British dark comedy-drama television series tracing the impact of sexual assault on memory, self-understanding, and relationships, and especially other sexual desires and expectations.

Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee

Multi award winning novel tracing misogyny, consent, power and indifference as they play out in one professor’s own actions and family in divided South Africa.

Love and Virtue by Diana Reid

Reid’s debut novel explores Australian college life and accompanying issues of consent, class, feminism and institutional privilege.

Sex Education

British comedy-drama series entering on the experience of adolescent sex education, thoughtful and nuanced around issues of consent, puberty, betrayal, love.

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

A memoir and series of ethical reflections weaving personal and detailed sexual experience together with gender and the family unit.

Masters of Sex

American drama exploring the research and relationship of William Masters and Virginia Johnson Masters and their pioneering scientific work on human sexuality.

On Seeing a Sex Surrogate by Mark O’ Brien

Photo courtesy of Jessica Yu

A short personal memoir about disability and sexual expression, through the particular experience of seeing a sexual surrogate.

Fleabag

British television series exploring sex, infidelity, ageism and how casual sexual identity joins up with the rest of a person’s identity.

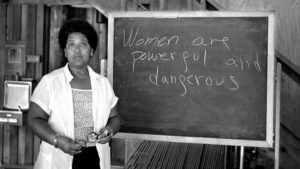

The Uses of the Erotic essay by Audre Lorde

A beautiful series of literary reflections on the power of the erotic, along with an exploration of why it is kept hidden, private, and denied, especially to particular groups.

Do the right thing from Little Bad Thing

From the podcast, Little Bad Thing about the things we wish we hadn’t done. This episode features a thoughtful conversation about the aftermath of assault, choices and healing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Epicurus

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 12 JUL 2022

After a two-year hiatus, the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI), is returning live and unfiltered to Sydney from 17–18 September at Carriageworks.

Ahead of the eleventh festival’s program release, we sat down with Festival Director, Danielle Harvey to get a sneak peek into the 2022 program and what it takes to create Australia’s original disruptive festival.

Our world has so rapidly changed over the past few years. How do you determine what makes an idea truly dangerous in this climate?

The thing with dangerous ideas is that they react and change with what’s going on in the world. When we consider FODI programming we always look to talk about the ideas that perhaps we’re not addressing in the mainstream media enough. The quiet, wicked ideas, that will be snapping at our heels before we know it!

FODI is about creating a space for unconstrained enquiry — for both audiences and speakers, so we aim to find different ways of talking about things; a different perspective or angle — whether that comes from putting people from different backgrounds or disciplines together or encouraging speakers to push their idea as far as it could possibly go.

The 2022 program will explore an ‘All Consuming’ theme. How do you feel this reflects our world at the moment?

This year’s theme responds to and critiques an age consumed by environmental disaster, disease, war, identity, political games and 24/7 digital news cycle.

It considers the constant demands for our attention and our own personal habits formed to deal with an avalanche of information, opportunity, and distraction. In an all-consuming time where there is so much vying for our attention, what exactly should we give it to?

How do you ensure a balance of ideas when putting a program together?

Our team has such a range of diverse roles and practices that provide us access to a very complementary range of experts across the arts, academia, business and politics. Some of us have worked together for over a decade which has meant we’ve developed an enduring dialogue that facilitates building a program in an exciting and agile manner.

After 10 festivals, we also have a fabulous and engaged speaker alumni network who keep us informed of any interesting developments in their respective fields.

FODI has been dubbed as Australia’s original disruptive festival, what is it about disruption that makes it important to base a festival around?

Progress happens when we are bold enough to interrogate ideas — when we’re able to have uncomfortable conversations and be unafraid to question the status quo. Holding the space open for critique without censure is incredibly important. It’s your choice if you come, if you want to sit in the uncomfortable, if you want to be curious about the world around you.

This year the festival will be held at Carriageworks. How does the festival align with this choice of site?

FODI has been privileged to have been housed in so many iconic Sydney venues, from Sydney Opera House to Cockatoo Island and Sydney Town Hall. Carriageworks is now a new home for FODI, that has empowered us to be bolder and provides a fantastic canvass for creating a truly ‘All Consuming’ experience for audiences, speakers and artists.

How would you reflect on the festival’s journey over the past few years to where it is now?

Obviously coming out of COVID in the last couple of years we’ve had some time to reflect, and perhaps the 2020 theme ‘Dangerous Realities’ was a little too prophetic! During that time we were one of the first festivals to turn that program digital, which aired over one weekend. We ended up having 10,000 people tune in live and then another 15,000 and a few days after it. I don’t think I’ve really seen any other festival that moved online and get those sorts of numbers that quickly. It’s a real credit to the FODI team and audiences.

Then in 2021 we embarked on a special audio project, ‘The In-Between’ which saw us pair unlikely people together to have a conversation about what this moment — pandemic, global power shifts, social shifts — might mean. That more open questioning was really enlightening, with some feeling afraid — like it is the end of an era. While others were more hopeful or unconvinced that it is anything new at all.

We’ve also been mining many of our FODI archival talks and released them as podcast episodes, which now have over 165,000 listens globally. It’s been fantastic to be reminded of how eerily relevant so many of these ideas were and how often we should look to the past in order to look forward.

As a result of our great digital programming and on demand content, we’ve now got this huge extended audience now and it’s been a joy to engage with people who weren’t physically able to join us previously.

What’s the most dangerous idea out there for you right now?

For the past two years we’ve been told that being with other humans is one of the most dangerous things you can do! So, I’m excited to see us come together, in person, this year and connect in a festival setting.

And finally, what are you most excited to see at FODI this year — what do you think sets this year’s program apart from others?

2022 heralds a return to public gatherings. We’re thrilled to support the arts and a return to live events and cultural activity after a very challenging time for so many in NSW and nationally.

I’m excited by bringing so many international speakers to Sydney, to hear some deep global analysis and different voices. The experiential elements we are planning will also provide another fabulous reason to get out of the house and back into our unique festival setting.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns 17–18 September 2022. Program announcement and tickets on sale in July. Sign up to festivalofdangerousideas.com for latest updates.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Feeling our way through tragedy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 29 JUN 2022

In October of 2021, The New York Times published a long article called ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, a story of kidney donations, poetic license, and vicious authors falling over one another to write damning words about those they publicly called their friends. Within hours of it hitting the internet, it had become the story of the day. And then the day after that. And then the day after that.

The thrust of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ is simple. Seven years ago, an aspiring author named Dawn Dorland donated a kidney, a selfless act motivated – at least on first glance – by pure charity. Rather than let this act remain anonymous, Dorland instead posted about it frequently across the internet, particularly in a digital writer’s group she was part of. One of the members of that group, Sonya Larson, began murmuring to other authors about what she saw as Dorland’s shameless desire for attention, turning Dorland and her donation into a particularly damning punchline.

But rather than keep her takedowns to private messages, Larson wrote a not-so-veiled short fiction story about Dorland and her perceived bent towards self-celebration. Titled ‘The Kindest’, the story draws heavily on Dorland’s life, and turns her into a warped and twisted version of herself; too arrogant and self-involved to behave in a genuinely charitable way, motivated only by pride and sickening grandiosity. Flash forward a few years, and Dorland had launched legal action against Larson over the story, a protracted battle that serves as the climax for ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’

There is a good reason that the fallout between the two writers so firmly captured the attention of the internet. It’s not just the tone of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, the writing is unabashedly gossipy, filled with back-and-forths between Larson and Dorland that are laced with enough invective to make your toes curl. It’s that the story provided an opportunity for the internet to agonize over a very old argument, given new life in the era of streaming and a fixation on true crime: who has the right to tell another’s story?

This Is Your Life

We tend to believe that we are the authors of our own life story – that we have an essential and inalienable hold over our own narratives. There is nothing, so one cultural myth goes, as sacrosanct and personal as our identity.

As such, those who adopt this view on identity consider the act of turning another human being’s life into art to be one steeped in ethical conundrums: an issue of consent and privacy, where the wishes of the subject must be valued over the artistic decisions of the author.

These are the people who took Dorland’s side in the ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ argument. They are also the people who have a bone to pick with the recent glut of “ripped from the headlines” media content, from Hulu’s Pam & Tommy, a fictionalised version of the media fallout after the release of Pamela Anderson’s sex tape, to Inventing Anna, a series following the rise and fall of Anna Delvey (real name Sorokin), a socialite who scammed her way through America’s upper class.

In each of these cases, a real-life story – with, in many cases, real-life victims – has been shaped into fiction, often without the subject’s consent.

Anderson herself pushed against Pam & Tommy being made, while Sorokin wrote an angry letter about the series from her jail cell.

But to believe that you – and only you – can tell your own story is to believe in a shaky foundational premise. Such an argument rests on the idea that each of us is hermetically sealed away from the world, and hold important and relevant insight into ourselves that no others hold.

It is the case that we know certain things about our lives that others do not. But we are embedded in a web of social relations, and in the imaginations and minds of all those we encounter. We are not, in fact, the faultless experts on ourselves. Our personality, such as it is, is shaped and tested in the minds of those who receive us. The delineations between “my story” and “your story” or “our story” are shakier than it might first appear. We are constructed by the world, not sat in opposition to it.

Why This Argument? Why Now?

People’s sacrosanct belief in the importance of their own personal identity – treated as though our narratives about ourselves are delicate pieces of crystal we hold close to our chests, too fragile to let anyone else hold, is tied to a growing retreat from structural and systemic issues, and an embracing of personal ones. The ultimate social currency is often not based in the story of many, but the story of one. “I am me, and nobody else could be me, and for that reason, nobody else could tell my story but me.”

On the whole, the creative scope of the streaming giants, particularly Netflix, and major Western movie studios, has changed tremendously, from the cultural to the individual. Adam Curtis, the documentarian, has pointed this out, bemoaning the fact that there are few artists looking to describe how life right now feels. In America, Australia and the UK in particular, mainstream creatives have limited desire to capture any experience that expands beyond very particular lived ones, that are presented as isolated, and unique.

The theorist and philosopher Christopher Lasch covered this decades ago, in his groundbreaking work The Culture of Narcissism. He addressed what he saw as a tendency to go inwards: faced by a souring political climate, Lasch argued Americans had traded a hope for big change, with a fixation on smaller, more intimate and cosmetic shifts.

It is no surprise then that, though arguments around the ethics of storytelling have been waging for decades, they have been given new poignancy by the frequency of creative projects that fixate on only one life, and the increasingly popular belief that we are alone, and lonely, and utterly unlike even those from our same cultural and class background.

The beauty of art is that it need never be blinkered in this way. I am not advocating for only one type of art, the cultural instead of the personal – and I don’t believe that Curtis or Lasch are either. That’s one way of falling into precisely the artistic stalemate we find ourselves in. It’s not hopping from one mode of storytelling to another, it’s mixing the two, providing a rich, mainstream creative palette.

In fact, the problem is a creative fixation, one that has begun to dominate swathes of cultural discourse and entertainment. A generation of storytellers have settled themselves into a rut, hashing the same old beats over and over, telling stories with the same foundational premise – we are not like each other. In turn, that means our questions about so much mainstream art are becoming repetitive, the discourses surrounding ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ and Pam & Tommy and Inventing Anna just familiar talking points shot weakly through with a desperate, failing dose of adrenaline.

The question, asked over and over again, is: “Who can tell my story?” But perhaps we should ask why we even consider it “my” story in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Infographic: Tear Down the Tech Giants

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethical dilemma: how important is the truth?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Life and Debt

A new podcast series with valuable insights on business sustainability, social responsibility and ethical decision making.

A podcast series that takes a deep dive into debt, what role it has in our lives and how we can make better decisions about it.

Australians are more in debt than ever before. A third of us are under financial stress. But how much do we actually know about debt? And why don’t we talk about it more often?

Created by Young Ambassadors from The Ethics Centre’s Banking and Finance Oath initiative (The BFO), the series aims to start a national conversation about what debt is and how we might make better decisions about it.

“Debt stood out to us as something that’s a challenge for everyone, but young people in particular,” said Iqra Bhatia, a young ambassador from the BFO, “because debt is a part of life, and it will be a part of our future.”

In this concise, four-part series, hosted by The Ethics Centre’s Cris Parker, hear from financial advisors, journalists, finfluencers, psychologists and historians about the psychology, the history, the marketing and the future of debt.

Because managing debt might be a part of life, but it’s not black and white.

Available to listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

This podcast is a project from the Young Ambassadors in The Ethics Centre’s Banking and Finance Oath initiative. Our work is made possible by donations including the generous support of Ecstra Foundation – helping to build the financial wellbeing of Australians. This series was released in 2022, ahead of our recent follow-up series Life and Shares.

Life and Debt Podcast Trailer

Whats inside the guide?

EPISODES

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF DEBT

How we make decisions about debt is shaped by more than just numbers on a spreadsheet; our childhood experiences, values and beliefs play a huge role. What role does shame and guilt play in the decisions we make about debt?

Australians are obsessed with buying their own home – more so than anywhere else in the world. Why? And what does this mean for our level of debt?

Hear from:

- Jess Brady, who has fourteen years of experience in the financial services industry and is the co-founder of the platform Ladies Talk Money – dedicated to supporting women from all walks of life in their journey toward financial freedom.

- Fiona Guthrie, CEO of Financial Counselling Australia who has been involved with the consumer movement for over 30 years.

- Rebecca Huntley, one of Australians foremost researchers on social trends.

- Nathalie Spencer, a behavioural scientist specialising in financial capability.

Listen to Ep 1 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

THE HISTORY OF DEBT

Today, most of us just accept that debt is a part of life, but how did we get here? In this episode we talk to financial journalist Alan Kohler and lecturer in philosophy Dr Alex Douglas, about how debt as we know it today came to be and what role it has in our society.

Hear from:

- Alex Douglas, a senior lecturer in philosophy in the School of Philosophical, Anthropological, and Film Studies at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland and author of the book, The Philosophy of Debt.

- Alan Kohler, who has been a financial journalist for 46 years. He currently works for the ABC and recently started a new publication – The Constant Investor.

Listen to Ep 2 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

THE MARKETING OF DEBT

Debt as a concept can be unpalatable. It can mean mortgages, decades long contracts and a total loss of freedom. But for some people, debt isn’t synonymous with restriction and constraint; it’s an opportunity. But the way debt is sold to us influences the way we perceive it. And in the new world order of buy now pay later, how is the way debt is marketed to us shifting?

Hear from:

-

-

-

- Finfluencer Natasha Etschmann, who shares how she saves, invests and makes money through her ‘@tashinvests’ channels on TikTok and Instagram.

- Adam Ferrier, a consumer psychologist, advertising creative and founder of the agency Thinkerbell.

- Fiona Guthrie, CEO of Financial Counselling Australia who has been involved with the consumer movement for over 30 years.

- Jonathan Shapiro, senior reporter at the Australian Financial Review.

-

-

Listen to Ep 3 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

THE FUTURE OF DEBT

We know that debt can be emotional. That sometimes it’s neutral. That debt is often necessary. And that debt has a long, long history. But what’s the future of debt? Will credit cards disappear from our lives? Will our concept of work itself change? In the context of a costly climate future, what are we going to have to let go of as a society? How do we need to adapt?

Hear from:

-

-

-

- Brett King, a futurist, author, host of a globally-recognised radio show, and the Founder and Executive Chairman of neo-bank Moven.

- Alan Kohler, who has been a financial journalist for 46 years. He currently works for the ABC and recently started a new publication – The Constant Investor.

-

-

Listen to Ep 4 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode: