Violence and technology: a shared fate

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

Don’t be distracted by the exploding sheds, steamrolled silverware and factory pressed field of poppies.

Many of the best works in Cornelia Parker’s exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) are small and unassuming. They are the quiet pieces that ask us to contemplate the nature of the technology we use in acts of violence.

A small pile of dust, some short leads of wire, a child’s doll split in two. These found object artworks – sculptures, just not those carved into marble or clay – are less about the state you see them in, but the journey they have taken.

On closer inspection (and with a little gallery guidance) we find intentional transformations of objects often associated with brutal violence: a gun, its bullets, the blade of a guillotine.

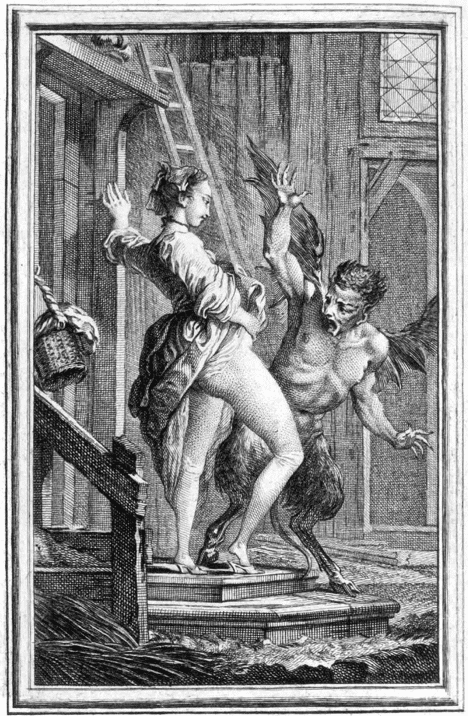

But don’t be alarmed. There is a dark sense of humour at play here. The disemboweled doll, a ginger-haired child in his newsboy cap and overalls, has a cartoon quality to his expression that echoes less of screams of pain than the shock of a bee sting. The boy has been severed at the waist by a guillotine. The very same guillotine that beheaded the infamous Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

We understand a guillotine as a tool of violence and power, designed to distribute French revolutionary justice at speed to behead the head of state. Here Parker has used the same tool that once transformed European history, to split a stuffed toy of Oliver Twist. Its title suggests a shared fate, that this piece of technology link the iconic Dickensian poor boy and the poster woman for opulence.

Shared Fate (Oliver), Cornelia Parker (2008)

The works on display in the gallery often ask us to consider what these tools of violence are used for, and our role in using them.

Sawn Up Sawn Off Shotgun (2015) has a similar tale of transformation. The story goes: a factory manufactured a shotgun, a criminal cut off its barrel to make it deadlier. He used it to murder an innocent person. It was collected as evidence by police to convict the man, before being decommissioned by being cut into smaller segments. It sits lifeless in front of us now in this quartered state.

In what way was the gun designed to kill? How did the modifications by each person impact its deadliness? And how does its use reflect on the ethics and values of those who designed, manufactured and modified this once-deadly artefact? It’s a neat example that calls to mind some of The Ethics Centre’s the principles for the ethics of design.

The design of the original shotgun, manufactured and distributed legally, embodied a set of values. Options include: the ‘good’ of farmers protecting their livestock from predators or the ‘good’ sporting competition using firearms. However, it was also a feature of the shotgun that beyond shooting ducks and foxes, it had the capacity to take a human life including during the commission of crimes. To what extent was that violent possibility actively noted and considered? Did the designer and manufacturer take any steps to protect against unintended uses?

Of course, we know also that the shotgun was modified and used beyond its intended purpose. By cutting off the barrel, the gun was deliberately modified to aid concealment and increase its deadly effect at close range. Whatever values might have been explicit in the original design are subverted by the modification where the explicit aim becomes to maim and kill in confined spaces.

This is what we consider the post-phenomenology of technology. We describe this in Ethics by Design: Principles for Good Technology as “…when a hitman picks up a firearm, he sets the purpose of the gun as a murder weapon. However, he also uses the gun to constitute himself as a murderer.”

We are told that the user in this case used this shotgun for just that purpose and in doing so made himself a murderer.

In its final transformation the design is changed once more. Using the same means as the criminal, cutting the shotgun again, the police officers have rendered it effectively useless. It no longer possesses the affordances of a weapon: no trigger to pull, no barrel to aim. It is a disembodied mess of its former designs, purpose and values. Here then the police constitute themselves as peace-keepers, because by destroying the deadly weapon they embody law and order.

Embryo Firearms (1995) Cornelia Parker.

If you take away from this the mantra that ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’ then there is another piece we are challenged to consider. Embryo Firearms (1995) presents two solid lumps of metal in the crude shape of pistols. At this point in their manufacturing they are absolutely harmless, resembling the type of gun you might cut from wood as a prop. These ‘guns’ are mere symbols – no more dangerous than any other lump of metal of equivalent heft.

We are informed though that this metal was intended to become a Colt firearm; one of millions produced each year.

The fact that any resulting weapon of this production process could be used for multiple purposes does not mean that it is ethically ‘neutral’. While guns themselves don’t have agency or intentions, their design and function shapes the user’s agency and open up a range of possible value-laden activities.

In their embryonic state these handguns provide as much agency as any slab of metal. We know at some point though, as the barrel is hollowed out, the firing pin is placed and the trigger is pulled, a tool of violent potential is born.

Transformation of intended design and purpose is taking place throughout Cornelia Parker’s works. Bullets are reduced to metal threads used to create geometric patterns, murder weapons are reduced to harmless dust via chemical precipitation, and our expectations about technology, art and violence are flipped on their heads.

The Ethics Centre is presenting The Ethics of Art and Violence a special event inspired by the work of acclaimed British artist Cornelia Parker currently on exhibition at the MCA. For more about the event click here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

If you’re gifted with downtime this holiday season, we’ve curated some big ideas for you to read, watch or listen to. These top picks will challenge your thinking over the holiday break.

-

The lost the art disagreement

In his keynote at the last Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Stephen Fry told us that “a Grand Canyon has opened up in our world and the crack grows wider every day. As it widens, enemies speak more and more incontinently about the other side.” Within this great fissure lies the lost art of disagreement. Hear how Fry suggests we begin to navigate through a world of seemingly opposing ideas.

-

Curb immigration, curb growth

Our cities are overcrowded, and our ecosystems are degrading at a rapid rate. Is population growth to blame? This year’s first IQ2 Debate: Curb Immigration, heard from environmental scientist Dr Jonathan Sobels, journalist Satyajet Marar, counter terrorism expert Dr Anne Aly and urban planner Professor Nicole Gurran. Watch the debate and hear their perspective on issues from urban planning and government policy, to environmental impacts and economic advantages.

-

An age of anger

Anarchy, resentment and the urge to smash the system seem to be spreading. What caused us to become so angry? How can we understand and navigate interactions with those who are? Author and academic Pankaj Mishra explains why society seems to be so quick to become outraged, and how transformative thinking might solve the epidemic.

-

Politics and populism

We are seeing a rise of nationalism, racism and authoritarian regimes across the world. Will democracy survive the new decade? At last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas Niall Ferguson contemplated the future of populist movements. Pankaj Mishra, Angela Nagle and Tim Soutphommasane joined a panel to explore if freedom is just too heavy a burden in the new world in the ‘Rehearsal for Fascism’.

-

Masculinity is not so fragile

Following the fallout of the #MeToo movement, many men feel that masculinity is unfairly under attack. David Leser, Zac Seidler, Raewyn Connell and Cath Lumby joined our IQ2 debate: Masculinity is it really so fragile, to share their views on modern masculinity and unpack the dangers or virtues of male normative behaviour.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns in 2020, bringing a host of big thinkers and new perspectives to the dangerous issues we face. Gift vouchers are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Feeling our way through tragedy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

Todd Phillip’s Joker has left audiences around the world outraged, moved and confused with its rewriting of the comic book lore surrounding The Joker.

The film tells the story of Arthur Fleck, a downtrodden man with an unspecified mental illness and an uncontrollable tendency to burst out laughing – whose treatment by society leads him down the path of moral nihilism and violence until he becomes the infamous Clown Prince of Crime.

It has received its share of controversy. Joker won the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, is receiving early Oscar Buzz and has clocked over $850 million in the worldwide box office.

It’s also been heavily criticised for being overly sympathetic to the perpetrators of mass violence. Many critics Fleck’s turn from reserved, alienated performing clown to theatrical mass murderer as analogy for the lives of a number of real-world mass shooters.

Couple this with Joker’s depiction of systemic social forces, not individual people, as the true villains of our time, and it can be argued that the film offers an apology for people who use violence – often against women and people of colour – as a way of expressing their dissatisfaction with a world that hasn’t given them what they want.

The film is shot from Fleck’s perspective, and therefore casts huge doubt on what is real and what’s just happening in Fleck’s mind. Not long after watching it, I found myself trying to piece it all together. Did the climactic final act actually happen?

The genius and mischief of unreliable narrator motifs – think of Inception for example – is that we find ourselves looking for a definitive reading, but none exists. Not even the director is able to close the debate – theirs is just another interpretation.

Interestingly, the unreliable narrator question in Joker serves as a handy metaphor for broader confusion about the ethics and politics of the film. If the critical commentary and public discourse are anything to go by, the film left audiences confused not only about the reality of the story, but about its morality as well.

And here’s the central rub with Joker as a political and ethical challenge. It’s rife with ambiguity. What does it stand for? Who is the villain and who – if anybody – is the hero? Are we meant to empathise with Fleck or judge him? Should we join the masses in being furious at the uber-rich and uber-callous Thomas Wayne, or should we be concerned at the accelerating rate of violence?

Just like we don’t know for sure what was in Fleck’s mind and what really happened in the film, it’s hard to know what the film wants us to think about the events of Joker.

Warner Bros themselves tried to pre-load people’s expectations of the film by saying “make no mistake: neither the fictional character Joker, nor the film, is an endorsement of real-world violence of any kind. It is not the intention of the film, the filmmakers or the studio to hold this character up as a hero.”

Despite this effort, most viewers will have arrived at the film with pre-conceived ideas, because the critical conversations around Joker have been relentless. From the first trailers released and a leaked script, people have been speculating about the political effects it would have. Some critics – even some who think the film has artistic merit – wonder if it should have been made.

There is something interesting going on here. On the one hand, we have people experiencing Joker in wildly different ways. On the other hand, we have critics – and the film developers – moulding people’s views of the film before they’ve even seen it.

Then we have the film itself, which is concerned with how easy it is for people to get swept up in movements. How quickly agency can be taken away. And how recklessly people can fight to reclaim that agency.

In Joker, Fleck is entirely without agency. He can’t control his random outbursts of laughter, he can’t make himself understood to his stand-up audiences and even as he begins to embrace his Joker identity, many of the systemic impacts of his actions aren’t through his design. When Fleck does try to seize some agency over his life, he – like the lower-class Gothamites who burn their city in violent riots – does so recklessly, callously and irresponsibly.

Zooming out to the discourse around the film, you can see life mirroring art. Audiences have been systematically deprived of the agency they need to form their own views around the film.

This happened well before the first trailer dropped. Arguably, it began with the rise of comic book movies more generally.

We live in an age where it’s easy to treat films as just another form of content. Just like we binge through streaming services and mindlessly scroll social media feed, we can let films wash over us without ever actively engaging with the material. Sure, we follow the plot and might have a view on whether we enjoyed the film or not, but that’s not the same as allowing a film (or a series, or whatever) to make us think.

The comic book movie is the embodiment of this trend. The heroes and villains are mapped out in advance. We know what will happen and we watch to find out how it will happen. Consider Avengers: Endgame. We knew Thanos would be defeated and that the heroes who had been snapped out of existence would return – after all, a bunch of them already had sequels in the calendar. There’s no moral ambiguity; just a good story.

Of course, that’s fine. The Marvel Cinematic Universe makes up for in fun what it lacks in moral complexity. But Joker is different. Despite appearing in the guise of a comic book film, it’s not a comic book movie at all. It didn’t need to be about the rise of The Joker. What that’s highlighted is how a generation raised on comic book movies have been left unprepared to engage with a film so rife with complexity.

Many are still trying to do so. Like Immanuel Kant encouraged in ‘What is Enlightment?’, they’re daring to think for themselves. Kant saw this enlightenment as liberating – a freedom from intellectual immaturity. But it might also be reckless – particularly if it ends up with people decided that Warner Bros are wrong and Fleck is the hero of the story.

But the best way to guard against this isn’t to avoid films like Joker, or to be too heavy-handed in how people interpret the film. It’s to create more space in our content consumption for things that are more than just fairy floss for our brains. To put the Iron Mans and Flashes of the world in their proper place and find some balance so that we can enjoy the fun for what it is without dulling our senses when something more complex comes along.

The Ethics Centre is presenting a panel discussion on The Ethics of Art and Violence at the MCA on 12 February. Tickets on sale now. For further information click here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Schools of thought: What is education for?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Renewing the culture of cricket

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 26 NOV 2019

On March 24, 2018, at Newlands field in South Africa, Australian cricketer Cameron Bancroft was captured on camera tampering with the match ball with a piece of sandpaper in the middle of a test match.

It later emerged that the Australian team captain Steve Smith and vice-captain David Warner were complicit in the plan. The cheating was a clear breach of the rules of the game – and the global reaction to Bancroft’s act was explosive. International media seized on the story as commentators sought to unpack cricket’s arcane rules and its code of good sportsmanship. From backyard barbeques to current and former prime ministers, everyone had an opinion on the story.

For the players involved, retribution was swift. Smith and Warner received 12-month suspensions from Cricket Australia, whilst Bancroft received a nine-month suspension. The coach of the Australian team, Darren Lehman, quit his post before he had even left South Africa.

But it didn’t stop there. Within nine months, Cricket Australia lost four board directors – Bob Every, Chairman David Peever, Tony Harrison and former test cricket captain Mark Taylor – and saw the resignation of longstanding CEO James Sutherland as well as two of his most senior executives, Ben Amarfio and Pat Howard.

So, what happened between March and November? How did an ill-advised action on the part of a sportsman on the other side of the world lead to this spectacular implosion in the leadership ranks of a $400 million organisation?

The answer lies in the idea of “organisational culture,” and an independent review of the culture and governance of Cricket Australia by our organisation – The Ethics Centre.

Cricket Australia sits at the centre of a complex ecosystem that includes professional contract players, state and territory associations, amateur players (including many thousands of school children), broadcasters, sponsors, fans and hundreds of full-time staff. As such, the organisation carries responsibility for the success of our national teams, the popularity of the sport and the financial stability of the organisation.

In the aftermath of the Newland’s incident, many wanted to know whether the culture of Cricket Australia had in some way encouraged or sanctioned such a flagrant breach of the sport’s rules and codes of conduct.

Our Everest process was employed to measure Cricket Australia’s culture, by seeking to identify the gaps between the organisations “ethical framework” (its purpose, values and principles) and it’s lived behaviours.

We spoke at length with board members, current and former test cricketers, administrators and sponsors. We extensively reviewed policies, player and executive remuneration, ethical frameworks and codes of conduct.

Our final report, A Matter of Balance – which Cricket Australia chose to make public – ran to 147 pages and contained 42 detailed recommendations. Our key finding was that a focus on winning had led to the erosion of the organisation’s culture and a neglect of some important values. Aspects of Cricket Australia’s player management had served to encourage negative behaviours.

It was clear, with the release of the report, that many things needed to change at Cricket Australia. And change they did.

Cricket Australia committed to enacting 41 of the 42 recommendations made in the report.

In a recent cover story in Company Director magazine – a detailed examination of the way Cricket Australia responded in the aftermath of The Ethics Centre’s report – Cricket Australia’s new chairman Earl Eddings has this to say:

“With culture, it’s something you’ve got to keep working at, keep your eye on, keep nurturing. It’s not: we’ve done the ethics report, so now we’re right.”

Now, one year after the release of The Ethics Centre’s report, the culture of Cricket Australia is making a strong recovery. At the same time as our men’s team are rapidly regaining their mojo (it’s probably worth noting that our women’s team never lost it – but that’s another story).

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The power of community to bring change

The power of community to bring change

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 19 NOV 2019

On Thursday night, a group of impassioned supporters and philanthropists gathered for a raw look at the work required to get an Ethics Centre program off the ground.

It was our very first Pitch & Pledge event – a unique crowdfunding concept by The Funding Network where charities pitch their funding needs live to a room of curious minds.

The format required three of our program leaders – Alex Hirst, Sally Murphy and Matt Beard – to take to the stage to make a six minute appeal for support for their work. Alex shared why she believes the Festival of Dangerous Ideas is critical to a tolerant society, Sally argued why more people need access to our free counselling helpline, Ethi-call, and Matt canvassed the idea of a budding young philosopher to further our work.

Following their pitches and a barrage of interesting questions from the floor, our leaders were asked to leave the room for a nail-biting window of time while guests pledged their support for their favourite program.

In an electric, emotionally charged and heartwarming hour we raised over $80,000 across the three causes, as well as further pro-bono support. We are incredibly grateful for the generosity of those who attended, and invite you to take a look at the pitches below and consider if there’s one worthy of your backing as well.

1. Support a truly independent Festival of Dangerous Ideas

Alex compelled us to realise that 10 years on from the first Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) in 2010, it’s no longer just a world of dangerous ideas we are considering – it’s the dangerous realities we need to be afraid of. Our modern world of opinion echo chambers and media algorithms that serve to confirm our biases, has lead to an inability across society to have informed and hard conversations about opposing views.

FODI is about challenging our ways of thinking, not confirming them. Sharing personal anecdotes and stories from FODI followers, Alex captured, to a rapt crowd, the sheer necessity of expansive thinking and contested ideas.

“Unchallenged ideas are after all some of the most dangerous, and they are reaching us in more ways than ever before. Reaching right into the heart of the home, and into our everyday lives.”

“If we are unable to have hard conversations, if we are untrained at listening to the ideas that we just don’t want to hear, then our ability as a society to face these dangerous realities together doesn’t exist”.

Ticket sales from the annual festival cover just 50% of festival running costs. Alex, and FODI, need support to bring critical thinking back to challenge dangerous realities in 2020.

Donate here: https://www.thefundingnetwork.com.au/ethics-centre

2. Help Ethi-call guide people through life’s tough decisions

Sally knows challenging situations. As a volunteer Ethi-call counsellor and manager of the service, she’s heard first-hand the difficult and often crippling dilemmas people face, and the impact a call with a trained expert can have.

In a landscape where communities are lacking connection, where neighbours don’t drop in for tea, families don’t spend quality time and friendships take place in text messages, more people feel they don’t have anyone to talk to about the challenging and tricky issues that they are facing.

Ethi-call is a free and independent service. It allows callers to share their troubles, explore their options and think about a path where perhaps there was none before.

Delicately sharing the challenges of two callers to the service, Sally showed the breadth of issues the service can help shine a light on. Whether it’s a young Australian choosing between duty and desire, the very hard choice many of us face around aged care for our ageing parents or a rural farmer forced into making the most heartbreaking choices due to drought, choice is a shared human experience and one that we don’t have to face alone.

Ethi-call only works if people use it. And to use it, they need to know it exists. Sally’s hope was to raise enough funding to let more people in need know that this vital service exists and to upgrade call technology to support additional privacy, a barrier to calling for potential users in the past.

Donate here: https://www.thefundingnetwork.com.au/ethics-centre

3. Plant the seed for a better ideas and fund a Young Philosopher

Dr Matt Beard is a philosopher who knows the value of a curious mind. It’s that itch that makes you wonder why the world is the way it is, that drives you to question what you’ve learnt to find a better way. He’s spent his working life scratching that itch.

Philosophy, Matt believes, is curiosity in motion. The history of philosophy is littered with world-changers. And the history of world-changers is littered with philosophy like Martin Luther King, and the foundations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It’s not just that they changed the world. It’s they were fuelled by the work of philosophy and philosophers.

At The Ethics Centre, we’ve spent thirty years developing new ideas and better worlds. We haven’t always gotten it right, and we’ve never done it alone, but there’s been one constant throughout the process – philosophy. From Primary Ethics in schools teaching children how to think critically, to Short & Curly downloaded over one million times, to Ethical by Design, a research paper that introduces much needed principles for designing ethical technology.

As one of just two philosophers on our staff, Matt says there are less philosophers, and less diversity of ideas than we need to address all the issues rising up out of the cracks in Australia. He says the ideas and possibilities for creating powerful positive change are endless, such as teaching ethics classes prisons, lowering recidivism rates, rethinking media ethics and the limits of free speech or understanding and addressing hate speech and political division in Australia.

But what we don’t have is the capital to support growing our staff. With more funding we can recruit, mentor and house the next generation of budding young philosophers at The Ethics Centre.

Donate here: https://www.thefundingnetwork.com.au/ethics-centre

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

We are pitching for your pledge

In celebration of our 30th anniversary which kicks off in November this year, we are preparing our very first live-crowdfunding ‘Pitch + Pledge’ night on Thursday 14 November.

Meet and hear directly from leaders of three of our flagship programs: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Ethi-call and our Young Philosopher initiative. Each speaker will pitch live on stage for six minutes each, and then answer the audiences questions. What follows is an unforgettable live-pledging experience, based on The Funding Network’s popular format.

1. Support a Truly Independent Festival of Dangerous Ideas

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas is Australia’s original big thinking festival – bringing leading minds from around the world to explore life’s most problematic and divisive issues.

Delivered in partnership with Sydney Opera House for almost a decade, last year marked the start of an exciting new phase for FODI as we branched out on our own. The 2018 festival was a triumphant sell-out, and audiences told us they walked away with a feast of new ideas and perspectives.

While FODI is well-attended and widely loved, it’s also a hugely risky and expensive event to stage. Our insistence on finding the best international storytellers, and keeping ticket prices affordable for broad audiences, pushes us into uncomfortable financial territory.

Your support will help us stage FODI as a break-even event, and allow us to keep doing it, year after year.

2. Help Us Reach More People in Need with Ethi-call

We’re enormously proud of Ethi-call. It’s our free, independent, national helpline available to all. The service provides expert and impartial guidance to help people make their way through life’s toughest challenges, when there’s nowhere else to turn.

Calls can be about almost anything – from professional issues (fraud, corruption, conflicts of interests) through to the deeply personal (birth, death, relationships, families).

There’s no other service like Ethi-call, so we receive calls from all over Australia, and all over the world. Your assistance will allow us to train more counsellors and ensure more people in need know the service exists.

3. Fund a Young Philosopher

Thirty years ago, a young philosopher with a keen interest in ethics and democracy, Dr Simon Longstaff, was appointed as The Ethics Centre’s first employee and Executive Director – a position he continues to hold today.

We’ve engaged a number of budding minds over the years to bring fresh thinking to our work, most recently Dr Matthew Beard, who plays an increasingly vital role in what we do.

We’re seeking funding to secure another bright young philosopher into our team – to apply their learnings to deliver insights and tools to help people build the skills and capacity to live according to their values and principles.

An opportunity to create a ripple effect of change

It will be a highly engaging and memorable evening for everyone involved and is an opportunity for you to get involved in some very exciting, critical projects here at The Ethics Centre.

We are putting our hearts and work on the line for your support. Pitch and Pledge will kick off at 5.30pm Thursday 14 November, at Clayton Utz offices, 1 Bligh St Sydney. Pledging starts from $100.

Please RSVP to rosemary.smithson@ethics.org.au with your details and your guests’ names to book your place to join us.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

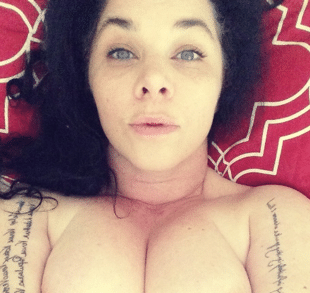

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Amy Gray 22 AUG 2019

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. By emphasising the potential for women to be made victims, we ignore the ways a woman’s body can be an expression of power.

According to the prevailing moral panic of the day, young women take naked selfies in order to please others and not themselves. This, we’re told, leaves them vulnerable to exploitation because women must always be vulnerable.

It’s as though the only mystery afforded to women is not their thoughts or talents but what lies underneath their clothes. Go no deeper than the skin. Deny any complexity that might present her as a human with needs separate from what men may want.

This seems to be a narrative we teach teenagers. My daughter was taught that not only was there no legal recourse for photos shared without consent (untrue) but that the effects on women were so catastrophic that they should never send a naked photo (also, untrue). This happened on International Women’s Day, as if to remind us of our to-do list.

Inevitably, they learn what we teach. When I worked with teens on a short film, they told me how boys pestered every girl in their class for naked selfies. The girls didn’t even think it was sexual; more of a competitive collection like Pokemon Go but for undeveloped breasts. The requests were thought of as frustrating but normal, because “that’s just how they are”. Yet despite the mundanity of such a frequent request, the same teens sincerely believed leaked selfies would hound a woman to her grave.

Naked selfies carry many gendered clashes. I’ve always gasped at the difference between gendered aesthetics: I’ll rush to clean my room, groom and put on makeup before getting into an appropriate outfit of sorts before painstakingly composing shots; men just send a close-up photo of their cock jutting from a thicket of pubes.

It’s an effective example of the differences between the male and female gaze. A woman prepares because she is conditioned to know what men find attractive and that she is expected to deliver that. Men, conditioned to expect immediate access regardless of merit, put almost zero thought into their selfies. In the rare case they do, they project an image of themselves they want to see, rather than women who mirror what men want to see.

This positioning reinforces the power dynamic in heterosexual sexting. Men expect entertainment and women entertain at threat of exposure (also expected).

But why does the power lie with men?

On image sharing site Imgur, men enthusiastically share photos of naked women, even creating themed days for certain ‘types’ of women. But the images presented reflect the male gaze – photos taken of women, not by women.

Generally, whenever women posted selfies on Imgur, sexualised or not, she was immediately inundated with caustic remarks to stop being an exhibitionist (a polite euphemism for attention whore). That these are the same men who think nothing of going into a woman’s DMs to ask for naked photos is just another layer to it all. There is a clear mode of production, where women are the object and men remain in control of when and how they are seen. This is where the phrase “tits or get the fuck out” shows its intent: give us the body parts, not the entire body.

Perhaps this is because it is easier to sexually appreciate an object that has not been humanised or seen as an individual. When things are anonymised or presented in such a volume that they lose all semblance of individuality, they become an object that can be appreciated or abused without shame.

The power balance still rests with men – naked women are objects men readily expect, and demand to be presented in anticipated service of them. In this position of power, men expect women to arouse them, yet rarely consider whether women are aroused. Amazingly, we rarely discuss whether women find joy or pleasure in taking naked selfies, whether for themselves or others because we can’t move past women’s seemingly inevitable victimhood.

I’ve taken naked selfies for well over a decade. I first worried if photos might leak but, somewhat ironically, this concern has disappeared as I do more work in public. In Doing It: Women Tell the Truth About Great Sex, an anthology about sex, I wrote of how selfies can become graphic storytelling that not only builds intimacy but also an understanding of my sexuality and my sexual aesthetic pleasure. It is a power I never want to give up, so the book also contains a naked photo of me I had taken for a lover. It is a deliberate attempt to interrupt the means of production and also claim space within my sexuality, one that is defined by myself, not others.

When the photo was republished (with consent) by SBS, I wrote that “this is not some wishy-washy Stockholm syndrome masquerading as empowerment – there is ferocity in my choice”. It remains true today. By claiming my agency as an individual who feels pleasure and expression, I realise that confidence is not only crucial for my personal survival under patriarchy framed solely for men, but it is also a political act I can define as I choose. It makes me aware that my body, choices and actions are decided by me without reference to others’ expectations and that I contain greater complexity the roles of servant or victim that society allows.

Around this time, Mia Freedman wrote an article entitled ‘The conversation we have to have: Stop taking nude selfies’. Promoting the article on Twitter, Freedman wrote “taking nude selfies is your absolute right. So is smoking. Both come with massive risks.” In response, I took another naked selfie, but this time with a cigarette draped from my mouth and ‘fuck off’ written on my chest in black lipstick. I posted it everywhere without care because – again – my body, choices and actions are decided by me. I made the choice that and every day is that I will not have victims presented as complicit in their abuse. Because the fault will always be with the abuser, not the abused.

An act of power

Despite their conflicting emotions, publishing naked selfies taken in either arousal or anger are fearsome in their power. They are as much a rejection of victimhood as they are an opportunity for retribution. People can try to weaponise my body against me, but I will do it first and use it against them because I know its power.

This is why patriarchal structures and men condition women into submissive disempowerment. Women’s bodies are defined narrowly as vessels for pleasures and service for others, not ourselves. Such narrow and compliant definitions intentionally belie the power and complexity we contain.

Stories abound throughout history of the malevolent power of women’s bodies, so profound was male unease surrounding bloods and births. Women were told their vaginas ruined ship rope or their menstruation damned success. This was an admission women’s bodies were terrifying in their otherness but was also an excuse to contain them to the home rather than out in the community where they might gain power or control.

But history tells us many women believed in the power of their bodies. Balkan women would stand out in the fields, flashing their vaginas to the sky to quell thunderstorms. The Finnish believed in the magic of harakointi, using their exposed bodies to bless or curse on whim. Sheela-na-gigs (carvings of women often found in European architecture) embraced their power by spreading their labia, not to please or welcome men, but scare off evil. Women would lift their skirts to make others laugh in feasts for Roman gods and goddesses or lure lovers. More recently, women have exposed their bodies to protest petroleum in Nigeria or civil war in Liberia in acts of political, angry anasyrma.

Reframing the dialogue

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. Women are presented as passively-defensive vessels in a state of perpetual victimhood. We are tasked with hiding our shameful-yet-coveted nakedness from people who expect to see us but only under their strict conditions.

A truer representation is that power exerts in all manners of life, including how we sexually communicate as equal, consenting partners. The moral panic should focus on when power corrupts that balance and how to correct it, not how to maintain the same corruption.

Join us as on 18 September for an an intimate conversation with Sexologist, Nikki Goldstein and art curator Jackie Dunn to unwrap the ethical dimensions of being nude. Get your ticket to The Ethics of Nudity here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What is all this content doing to us?

Join our newsletter

BY Amy Gray

Amy Gray is a Melbourne-based writer interested in feminism, popular and digital culture and parenting. follow her on twitter @_AmyGray_

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 AUG 2019

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI), Australia’s original provocative ideas festival, returns in 2020 for its 10th festival. April 3 to 5 will be a milestone weekend of provocation, contemplation, critical thinking and preparation for the battles of the next decade.

Presented by The Ethics Centre, FODI 2020 will once again feature leading thinkers from Australia and around the world to interrogate the issues of today and prepare for the major shifts of tomorrow.

FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey said: “Over the past decade the number of avenues for people to talk and share their opinions has steadily increased, we are more connected than ever with like-minded people, but the cost has been significant. We are losing the ability to listen.

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before.”

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before. The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has always been an opportunity for deep thinking, carving out precious space for disagreement, difference of opinion and critical thinking.

“As we brace for 2020, FODI will celebrate its 10th anniversary by looking again to the future and presenting a cohort of FODI alumni, representing the world’s best thinkers, journalists, creators and specialists, giving Sydneysiders an opportunity to listen to what will be shaping the world tomorrow.”

The Ethics Centre Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff said:

“The Ethics Centre is thrilled to once again be presenting the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. One of The Ethics Centre’s strategic priorities is to build and sustain the ‘ethical infrastructure’ that underpins a free, dynamic and democratic society.

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear.”

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear. FODI tests the truth of the claim that we are a ‘civil’ society – and proves that even in moments of profound disagreement – we have the strength to live an ‘examined life’.”

Last year’s sell-out festival featured Stephen Fry, Rukmini Callimachi, Niall Ferguson, Megan Phelps-Roper, Chuck Klosterman and Toby Walsh.

More information, including the full program and festival venue, will be announced in the coming months. Visit festivalofdangerousideas.com to subscribe to be the first to hear our news.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 6 AUG 2019

The Ethics Centre (TEC) has made a submission to the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) regarding its discussion paper, The Regulation of Lobbying, Access and Influence in NSW: A Chance To Have Your Say.

Released in April 2019 as part of Operation Eclipse, it’s public review into how lobbying activities in NSW should be regulated.

As a result of the submission TEC Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff has been invited to bear witness at the inquiry, which will also consider the need to rebuild public trust in government institutions and parliamentarians.

Our submission acknowledged the decline in trust in government as part of a broader crisis experienced across our institutional landscape – including the private sector, the media and the NGO sector. It is TEC’s view that the time has come to take deliberate and comprehensive action to restore the ethical infrastructure of society.

We support the principles being applied to the regulation of lobbying: transparency, integrity, fairness and freedom.

Key points within The Ethics Centres submission include:

-

- There is a difference between making representations to government on one’s own behalf and the practice of paying another person or party with informal government connections to advocate to government. TEC views the latter to be ‘lobbying’

-

- Lobbying has the potential to allow the government to be influenced more by wealthier parties, and interfere with the duty of officials and parliamentarians to act in the public interest

-

- No amount of compliance requirements can compensate for a poor decision making culture or an inability of officials, at any level, to make ethical decisions. While an awareness and understanding of an official’s obligations is necessary, it is not sufficient. There is a need to build their capacity to make ethical decisions and support an ethical decision making culture.

You can read the full submission here.

Update

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director at The Ethics Centre, presented as a witness to the Commission on Monday 5 August. You can read the public transcript on the ICAC website here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 6 MAY 2019

Corruption and probity are hot topics in Australia’s public sector. Even a cursory glance at recent cases brought before corruption watchdogs shows this.

The long running stories and court cases that follow have become a staple of national news bulletins. Any time a state asset is built, sold or disposed of, there are serious questions to be asked.

Probity – which is a corporate noun for ethics or honesty and decency – has established its place in the architecture of technical services that assess, assure and measure high-risk public sector projects. Probity advising and auditing is crucial when how a project is executed is just as important as any intended outcome.

As the line separating public and private sector accountabilities becomes less clear, non-government actors are increasingly looking to probity professionals to help ensure – and show – integrity in their dealings. However, before doing so it is important the probity professionals themselves improve the integrity of their process and gain a more sophisticated understanding of ethical frameworks.

Probity services are provided both by large accounting firms and a growing band of smaller boutique operators. Probity plans (documents that set out how the project will be run to ensure the integrity of the process) are now a mandatory requirement for many public projects.

Probity professionals use a number of lenses to monitor and promote ethical decision making in execution, typically through the following fundamentals:

Value for money: Was the market tested adequately to ensure an organisation was achieving the most competitive result, which made the best use of resources?

Conflicts of interest and impartiality: Were processes in place to manage any actual, perceived or potential conflicts of interests?

Accountability and transparency: Was an auditable trail maintained to provide evidence of the integrity of the process? Was enough information made available to promote confidence – for example, were selection criteria and time lines for decision making adequately communicated?

Confidentiality: When sensitive information from stakeholders is received, such as private or business-in-confidence information, was there a process in place to identify and protect this information?

The growth of probity services over the last 30 years undoubtedly reflects their ability to add value to projects. However, over that same period there has been concern that practitioners have at times diminished, rather than promoted, probity fundamentals. Some of the critical factors include:

- Relying too heavily on compliance monitoring at the expense of ethical considerations

- Allowing their duties to be too narrowly defined by clients

- Lacking the confidence to challenge impropriety

- Allowing themselves to be “shopped” (much like “legal advice shopping,” clients can go from one probity advisor to another until they get the advice they want).

There is also concern that public sector agencies can overuse these services, having the effect of “contracting out” their probity obligations in their regular operations.

To some extent these are symptoms of the unregulated nature of probity services. There are no formal qualifications required for probity advisors and auditors and no professional standard governing them.

Their difference from traditional audits or investigations has led to some misunderstanding of their role and judgements which can lead to unfair criticism of probity professionals, but also to exploitation by both clients and probity practitioners.

To tackle these problems and prepare for a broader role in guiding business dealings, probity practitioners need to acknowledge their own industry’s need for an ethical framework and an increasingly robust standard for professional practice.

This framework would acknowledge their implied obligation to society to be more than a mere compliance check, and, on behalf of the average Joe on the street, to be the one in the room to ask a simple pub test question: after all the boxes have been ticked, does it look and sound like an ethical process?

To do this, the profession needs to imagine its duty in broader terms than self-interest or the interest of clients, but to society in general, in line with other professions tasked with acting in the public interest.

For some time, probity professionals have used policy documents such as the NSW Code of Practice for Procurement to gauge the ethical performance of government projects. However, as their duty and work expands to different sectors and in line with changing community expectations, they will need to be able to identify the ethical frameworks peculiar to those sectors and to the organisations they are commissioned by.

Used effectively, an ethical framework is the foundation of an organisation’s culture.

When requested to provide probity related advice, The Ethics Centre includes the ethical framework amongst its list of fundamentals. This allows our clients to do more than tick boxes. It allows them to assess whether they have lived up to their ethical obligations, the values they proport to uphold and their promise to the community.

In a world in which trust is in deficit, these are important skills to have.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights