Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 25 AUG 2025

Our society is built on trust. Most of the time, we trust institutions and the government to do what they say they will. But when they break that trust – by not keeping their promises or acting unfairly – that’s when things start to fall apart. The system stops working for the people it’s supposed to serve.

As a result, we trust regulators to protect the things that matter in our society most. Whether it’s holding institutions to account, or ensuring our food, water and transport are safe, a regulator’s role is to ensure society’s safety net.

But when something goes wrong, the finger usually points straight at the regulator. And while it’s tempting to blame regulators about why things have failed, new policy research from former Chairman of ASIC, James Shipton, suggests we’re asking the wrong question.

The real issue isn’t just who’s doing the job, it’s how the whole system is built.

Shipton is working towards optimising regulation by improving regulatory design, strategy and governance. As a Fellow of The Ethics Centre, he has engaged with industry to develop a better understanding of regulators and the regulated. This work aims to crystalise the purpose of regulation and create a pathway where that purpose is most likely to be achieved.

Shipton’s paper, The Regulatory State: Faults, Flaws and False Assumptions, takes the entire regulatory system in Australia into account. His core message is simple but urgent: our regulators are set up to fail by design.

Right now, most regulators operate in a system that lacks clear direction, support, and accountability. Many don’t have a clearly defined purpose in law. That means the people enforcing the rules aren’t always sure what they’re meant to achieve.

This confusion creates a dangerous “expectations gap” where the public thinks regulators are responsible for outcomes they were never actually empowered to deliver. When regulators fall short, they wear the blame, even when the system itself is broken.

Shipton identifies twelve major flaws in our regulatory system and while they might sound technical, they have real-world consequences. He starts with the concept that our regulators are monopolies by design. Each regulator is the only body responsible for its area – there’s no competition, no pressure to innovate, and very little incentive to improve. In the private sector, companies that fail lose customers and reputations, and customers are free to go elsewhere. In regulation, there’s no alternative.

The heart of Shipton’s argument is this: credibility is key. It’s not enough for a regulator to have legal authority, they need public trust. And that trust only comes when the system they work within is built for clarity, accountability, and ethical responsibility.

For example, in aviation, everyone from pilots to engineers shares a common goal: safety. The whole sector becomes a partner in regulation. But in most industries, that kind of alignment doesn’t exist, often because the system hasn’t been designed to make it happen.

Shipton stresses that design matters. Regulators need clear goals, realistic expectations, regular performance reviews, and laws that actually match the industries they oversee. We don’t need another inquiry into regulatory failure. We need to ask why failure keeps happening in the first place. And the answer, Shipton says, is clear: the entire regulatory architecture in Australia needs redesigning from the ground up.

This doesn’t mean tearing everything down. It means recognising that public trust is earned through structure. It means giving regulators the tools, support, and clarity they need to do their job well and making sure they’re accountable for how they use that power.

If we want fairness, safety, and integrity in the things that matter most, we need a regulatory system we can trust. And as Shipton makes clear, trust starts with design.

James Shipton is a Senior Fellow, Melbourne Law School, The University of Melbourne, Fellow, The Ethics Centre, and Visiting Senior Practitioner, Commercial Law Centre, the University of Oxford.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Housing affordability crisis: The elephant in the room stomping young Australians

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is it ok to use data for good?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Businesses can’t afford not to be good

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

David and Margaret spent their careers showing us exactly how to disagree

David and Margaret spent their careers showing us exactly how to disagree

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 19 AUG 2025

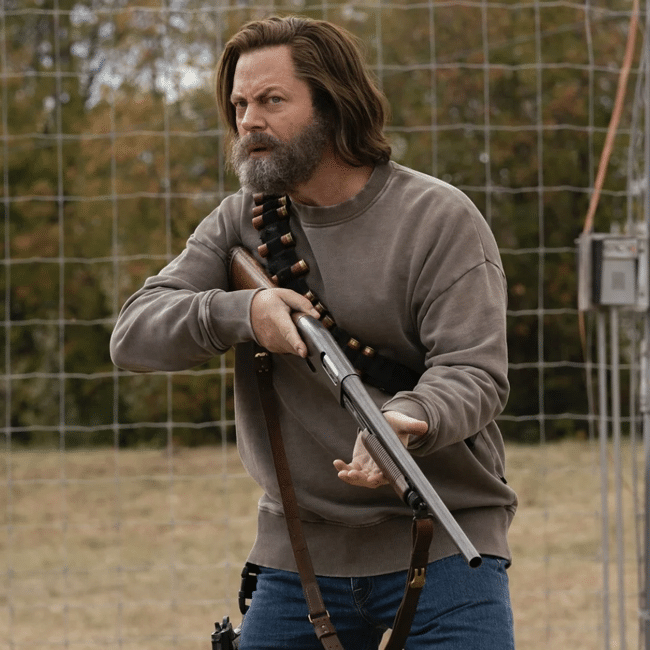

When David Stratton – critic, TV presenter and hero to a generation of movie lovers – died last week at 85, he was immediately honoured as one of this country’s true soldiers of cinema: a relentless advocate who spent his life championing the artform he loved.

Cinema had a loyal, passionate and fiercely intelligent friend in David Stratton. He was a man who worked hard to make loving movies seem serious and worthwhile – so much more than just a hobby.

But over the course of his long and varied career, Stratton didn’t just kindly, patiently and honestly explain his passions. Along with his onscreen co-host Margaret Pomeranz, he also taught us a deeply valuable ethical lesson, time and time again: a lesson in the fine art of disagreement.

What do Lars Von Trier and Vin Diesel have in common?

Pomeranz and Stratton were, from the very start of their time together, opposites. Pomeranz, who began her career in television as a producer, and was encouraged to move in front of the camera by Stratton, prized a curiously outrageous form of entertainment far more than Stratton.

Stratton loved to laugh, make no mistake, but he drew a line at anything he considered tacky. Pomeranz, by contrast, loved that stuff. When they butted heads, it was over films like Team America: World Police (Pomeranz loved it; Stratton hated it); Sex And The City 2 (Pomeranz said it contained a “jacket she’d kill for” and gave it three stars; Stratton called it “offensive”).

These differences in opinion weren’t just a casual “let’s agree to disagree” partings of ways. Once, memorably, Pomeranz gave Lars Von Trier’s Dancer in The Dark five stars, while Stratton gave it zero. When Pomeranz stood up for Vin Diesel, a performer Stratton hated, Stratton lightly poked fun at her, saying she wanted Diesel to “save her.” Possibly their biggest disagreement was over the classic Australian film Romper Stomper, starring Russell Crowe as a wild-eyed neo-Nazi. Stratton not only thought the film was terrible, he thought it was actively ethically harmful. Pomeranz gave it five stars.

Sometimes these disagreements got a little heated. Stratton could be dismissive; Pomeranz seemed occasionally exasperated with him. But the pair never lost respect for one another, no matter how far apart their tastes pulled them – and, importantly, they never started throwing barbs at each other. Their disagreement was localised to the thing they were disagreeing about, not ad hominem snipes at the other’s character.

Pomeranz herself acknowledged this, in a recent tribute written to honour her friend and colleague. “I think it’s extraordinary that, over all the time that David and I worked together, we never had a falling out”, she wrote. Disagreements between the two were common. But true breaks in the relationship – true threats to their working together – never were.

The power of disagreement

Sometimes, disagreement is cast as an impediment to societal functioning. We can all be guilty of occasionally speaking as though disagreement is the enemy – as though for us to all flourish, we should all get along, all the time. That’s not to say that there are some matters where disagreement should be encouraged – the power of disagreement is not a free card to put every matter up for debate, no matter how harmful.

But the history of philosophy shows us there’s power in sometimes parting opinion. Plato, for instance, presented almost all of his arguments in the form of debates, with characters going back and forth amongst each other on what is the correct behaviour. Plato’s “dialogues”, and thus, his entire ethical worldview, were fashioned out of disagreement.

It is in disagreement, after all, that we get to honour one of the beautiful things about our world – difference, uniqueness, and the full richness of human experience.

It would be a very boring, and perhaps even insidious, world if we all thought the same thing. After all, a forced unity of opinion is one of the hallmarks of fascism.

Disagreements, if handled and conducted well, can also guide us away from extremes. In some matters, truth lies in the middle of two poles. So it went on The Movie Show at least – I am not convinced we always agreed with our favourite from the pair. As viewers, our own tastes fluctuated between the extremes of Pomeranz and Stratton. In their disagreements, we could pick and choose elements of their tastes, and construct our own.

And again, these were debates that never descended into name-calling, or anger. In this, Pomeranz and Stratton taught us another ethical lesson – that we can treat someone disagreeing with us as someone offering us kindness. Having to justify and argue for our own positions helps us better understand them. And it helps us better understand the world around us; the people around us.

Laying my own cards on the table, I’ve always been more of a Pomeranz person (I love Von Trier, Romper Stomper, and Team America). But that’s just the thing. No matter how much I, a viewer raised on The Movie Show, found myself grumpily disagreeing with Stratton, it never made me dislike him. And when he passed, the loss I felt was not just the loss of a man I had always admired. It was the loss of a defender of art and a good sparring partner – no matter that it was one-sided sparring, through the TV. Disagreement done well is a gift. And no one more generously gave out that gift than David Stratton.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Cancel Culture

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Daniel Finlay 19 AUG 2025

In early 2025, 60 female students from a Melbourne high school had fake, sexually explicit images of themselves shared around their school and community.

Less than a year prior, a teenage boy from another Melbourne high school created and spread fake nude photos of 50 female students and was let off with only a warning.

These fake photos are also known as deepfakes, a type of AI-augmented photo, video or audio that fabricates someone’s image. The harmful uses of this kind of technology are countless as the technology becomes more accessible and more convincing: porn without consent, financial loss through identity fraud, the harm to a political campaign or even democracy through political manipulation.

While these are significant harms, they also already exist without the aid of deepfakes. Deepfakes add something specific to the mix, something that isn’t necessarily being accounted for both in the reaction to and prevention of harm. This technology threatens our sense of autonomy and identity on a scale that’s difficult to match.

An existential threat

Autonomy is our ability to think and act authentically and in our best interests. Imagine a girl growing up with friends and family. As she gets older, she starts to wonder if she’s attracted to women as well as men, but she’s grown up in a very conservative family and around generally conservative people who aren’t approving of same-sex relations. The opinions of her family and friends have always surrounded her, so she’s developed conflicting beliefs and feelings, and her social environment is one where it’s difficult to find anyone to talk to about that conflict.

Many would say that in this situation, the girl’s autonomy is severely diminished because of her upbringing and social environment. She may have the freedom of choice, but her psychology has been shaped by so many external forces that it’s difficult to say she has a comprehensive ability to self-govern in a way that looks after her self-interests.

Deepfakes have the capacity to threaten our autonomy in a more direct way. They can discredit our own perceptions and experiences, making us question our memory and reality. If you’re confronted with a very convincing video of yourself doing something, it can be pretty hard to convince people it never happened – videos are often seen as undeniable evidence. And more frighteningly, it might be hard to convince yourself; maybe you just forgot…

Deepfakes make us fear losing control of who we are, how we’re perceived, what we’re understood to have said, done or felt.

Like a dog seeing itself in the mirror, we are not psychologically equipped to deal with them.

This is especially true when the deepfakes are pornographic, as is the case for the vast majority of deepfakes posted to the internet. Victims of these types of deepfakes are almost exclusively women and many have commented on the depth of the wrongness that’s felt when they’re confronted with these scenes:

“You feel so violated…I was sexually assaulted as a child, and it was the same feeling. Like, where you feel guilty, you feel dirty, you feel like, ‘what just happened?’ And it’s bizarre that it makes that resurface. I genuinely didn’t realise it would.”

Think of the way it feels to be misunderstood, to have your words or actions be completely misinterpreted, maybe having the exact opposite effect you intended. Now multiply that feeling by the possibility that the words and actions were never even your own, and yet are being comprehended as yours by everyone else. That is the helplessness that comes with losing our autonomy.

The courage to change the narrative

Legislation is often seen as the goal for major social issues, a goal that some relationships and sex education experts see as a major problem. The government is a slow beast. It was only in 2024 that the first ban on non-consensual visual deepfakes was enacted, and only in 2025 that this ban was extended to the creation, sharing or threatening of any sexually explicit deepfake material.

Advocates like Grace Tame have argued that outlawing the sharing of deepfake pornography isn’t enough: we need to outlaw the tools that create it. But these legal battles are complicated and slow. We need parallel education-focused campaigns to support the legal components.

One of the major underlying problems is a lack of respectful relationships and consent education. Almost 1 in 10 young people don’t think that deepfakes are harmful because they aren’t real and don’t cause physical harm. Perspective-taking skills are sorely needed. The ability to empathise, to fully put yourself in someone else’s shoes and make decisions based on respect for someone’s autonomy is the only thing that can stamp out the prevalence of disrespect and abuse.

On an individual level, making a change means speaking with our friends and family, people we trust or who trust us, about the negative effects of this technology to prevent misuse. That doesn’t mean a lecture, it means being genuinely curious about how the people you know use AI. And it means talking about why things are wrong.

We desperately need a culture, education and community change that puts empathy first. We need a social order that doesn’t just encourage but demands perspective taking, to undergird the slow reform of law. It can’t just be left to advocates to fight against the tide of unregulated technological abuse – we should all find the moral courage to play our role in shifting the dial.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The “good enough” ethical setting for self-driving cars

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Economic reform must start with ethics

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 15 AUG 2025

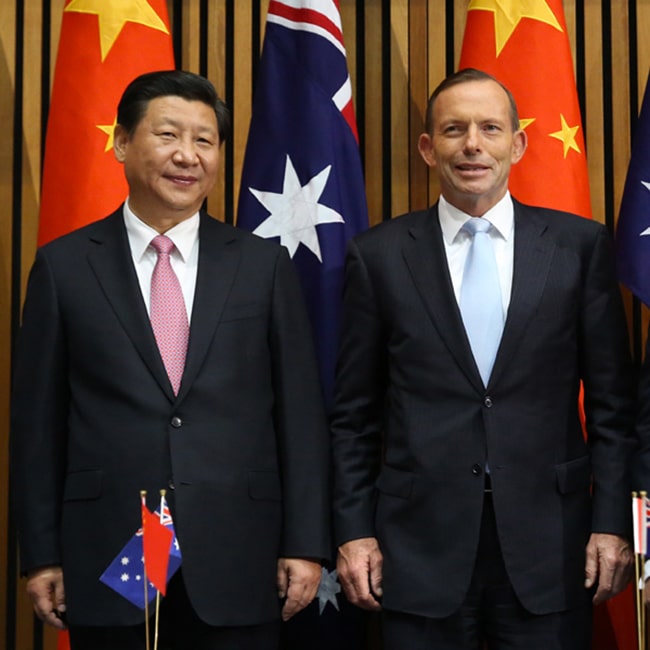

With inflation tamed, interest rates falling and wages rising, the government of Anthony Albanese has worked itself into a position where it can now develop a range of longer-term economic initiatives.

With this in mind, the government will convene an Economic Roundtable next week to consider ideas about how to best to achieve sustainable prosperity.

I suspect that the Roundtable will focus on a range of ‘big ticket’ ideas for innovation and reform in areas such as tax, energy, infrastructure, industrial relations and the like. If all goes well, equal attention will be given to areas of social policy that have a major impact on the economy – including in areas such as childcare, mental health, social welfare, etc. Although not falling under a narrow heading of ‘economic policy’, all of these areas have a significant impact on the productive capacity of the Australian economy. In other words, a strong economy depends as much on sound ‘social’ policies as it does on sound ‘economic’ policies.

However, there is a deeper ethical dimension that we hope will also be taken into account. Over a period of four years, Deloitte Access Economics has been exploring the link between ethics and the economy. Most recently, its work has zeroed in on the connection between ethics and productivity. Their findings are as follows:

The relationship between ethics and productivity is increasingly recognised in economic literature and international practice.

There is capacity for trust and ethical behaviour to:

- Boost worker wellbeing and mental health, which are directly linked to labour productivity.

- Improve business performance, with higher ethical standards leading to stronger returns on investment.

- Reduce red tape, by lowering the perceived need for regulation in high-trust environments.

- Enable economic reform, by building public support for complex policy changes.

- Accelerate the uptake of technology, such as artificial intelligence, where trust remains a key adoption barrier.

This has remarkable implications for our nation’s prosperity (in both economic and social terms):

- A 10% improvement in ethical behaviour yields a 2.7% wage increase and a 1% gain in mental health, worth over $23 billion across the economy.

- A standard deviation increase in business governance is associated with a 7% increase in return on assets.

- Countries with higher social trust experience 15-19% fewer regulatory procedures to start a business.

- Aligning Australia’s trust levels with global leaders could lift GDP by $45 billion, or $1,800 per person.

There should be no mystery in this, and the effects are clear and simple. Much of it comes down to the possibility of reform (of any kind). Identifying areas of reform is relatively easy. The difficulty relies in their adoption. This is because all reform is subject to resistance from those who fear that they will be left worse off. In turn, strong resistance creates friction that either slows or prevents reform – inevitably leading to sub-optimal outcomes for society as a whole. The number of people who fear being left worse off is often greater than the number of people who will actually be adversely affected. Even when people recognise that they are likely to benefit from reform – they will still oppose it in the belief that the ‘people in charge’ cannot be trusted to ensure that the benefits and burdens are fairly distributed. In other words, it all boils down to questions of trust. And as economists have known since the dawn of their ‘dismal science’ – high trust=low cost and low trust=high cost.

Yet, trust itself is a function of ethical alignment. Ethics, and the trust it engenders, reduces ‘friction’. Thus, trust is a catalyst and enabler of productive reform. To put it simply:

Good ethics → improved trust → greater prosperity.

There are some deep paradoxes in this outcome. The most challenging of these is that although ethics produces a demonstrable economic dividend, it only has maximum effect if people act for non-instrumental reasons. In other words, ‘you don’t get the dividend if you do it for the dividend.’

We have long believed that the whole of Australia would benefit if, as a society, we invested more in revitalising our ‘ethical infrastructure’ alongside the physical and technical infrastructure that typically receives all of the attention and funding.

The evidence is clear that good ethical infrastructure enhances the ‘dividend’ earned from these more typical investments – while bad ethical infrastructure only leads to sub-optimal outcomes.

I doubt that the link between ethics, trust and prosperity will capture any headlines when the Economic Roundtable is convened. But wouldn’t it be great if it could at least be noted as a vital enabler of any reform that hopes to succeed.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr. Helen Hoang 12 AUG 2025

“Mum, why can we buy toys, but others can’t?”

My son’s question seemed simple, but behind it lay deeper questions about scarcity and fairness. And like many parents, I found myself unprepared to explain a system even most adults struggle to fully understand.

Growing up in a remote village in northern Vietnam, I experienced scarcity first-hand. Only one child per family could attend school while the rest worked. These were choices shaped by poverty and silence. Worse, no one asked why. And that’s what drew me to economics: to find not just answers, but better questions and solutions.

What if we taught kids not just how economies work, but why they work that way? What if, from a young age, they learned that the economy isn’t just numbers, but a system shaped by values, power, and people? It could transform their worldview and their future.

Australia is facing a quiet crisis in economic and financial literacy. More than 1 in 6 Australian 15-year-olds fail basic financial literacy. The issue is particularly stark among young women: only 15% meet standards, compared to 28% of boys. Meanwhile, enrolments in Year 12 economics have dropped by nearly 70% since the 1990s. The Reserve Bank of Australia warns that a lack of economic understanding not only limits personal well-being but also weakens national participation. The National Australia Bank has reported increasing financial vulnerability among youth with low literacy levels.

But this isn’t just a gap in knowledge, it’s a growing divide in civic understanding.

Why financial and economic literacy must be taught with ethics

Too often, financial and economic literacy are conflated. In truth, they are distinct yet deeply complementary. Financial literacy teaches individuals how to manage money. Economic literacy explains the systems shaping those decisions. One is practical, the other structural.

What’s missing is ethics – understanding who the economy should serve. This requires critical thinking about values, justice, and responsibility. It involves teaching children that every economic decision is a moral one, and that their choices can help shape a fairer world.

By teaching financial and economic literacy alongside ethics, we not only teach survival skills, but cultivate thoughtful participants in a fairer economy.

This approach encourages them to assess trade-offs, consider long-term impacts, and understand the values reflected in their choices. It sharpens understanding of the hidden costs of our financial choices: the underpaid worker behind a “cheap” shirt, the personal data exchanged for a “free” app, and so on. In learning to not just ask “Can I afford this?” but “What does this cost others?”, students can develop both agency and empathy.

Three timeless economic lessons every child should learn

1. Choices and scarcity aren’t just a constraint, they’re questions of justice

Economics begins with scarcity: we live in a world of limited resources, so choices must be made. But helping children make smart trade-offs is often where financial literacy stops.

Ethical economics asks a harder question: Why are some people forced to make impossible choices while others never have to choose at all?

Our resources are not evenly distributed, and how they are distributed reveals the underlying values of our economic systems. Furthermore, the mechanics of limited choices reveal the moral concerns of our society, issues ethical economics serve to investigate.

When we teach children only to manage scarcity, to see limited choice as inevitable, we risk normalising injustice. But when we teach them to understand and question it – Who sets the rules? Who is left out? Why? – we nurture civic responsibility and moral courage.

2. Incentives and transactions: the ethics beneath every exchange

Children learn the logic of trade early: stickers for chores, screen time for good behaviour, lunchbox swaps at school. These are their first lessons in transactional incentives, one of economics’ most powerful tools.

But incentives are not morally neutral. They reflect what we value and who we reward.

When we teach economics as just transactions, kids learn to see the world only through profit and loss. Ethics, however, reminds us that not all trades are fair or impassioned, and not all incentives are neutral. Behind every transaction is a judgement. Behind every incentive is a set of assumptions. Without accounting for context, incentives risk rewarding privilege while penalising disadvantage.

Teaching children to recognise this helps them move beyond “getting what you deserve” to asking: Who is allowed to participate?

This teaches not just how to respond to incentives, but how to question what they promote and whom they serve.

3. Markets need morality

Markets are often framed as natural forces: efficient, self-correcting, and impartial. But they’re not.

Scottish economist Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” theory describes how individual self-interest can lead to collective benefit. Yet Smith, also a moral philosopher, warned that markets only work when anchored in trust, justice and social responsibility.

English economist and philosopher John Maynard Keynes also argued that when markets fail, as they do during crises like the Great Depression, governments have an ethical obligation to intervene. During COVID-19, children saw this play out in real time: their parents receiving stimulus payments, rent relief or panic buying. But did they understand why?

Well, they should. That’s the real lesson: markets need rules, and rules need values. Who gets what, and why? These questions encourage children to investigate systemic motives and hold them accountable to their ethical obligations. Teaching students that both markets and governments are designed by people and reflect our collective choices helps them understand they can shape these systems too.

Raising ethical citizens, not just economic agents

Teaching economic literacy without ethics risks raising informed consumers but disengaged citizens. But when we teach children that every economic choice reflects a set of values, we equip them with something far more powerful than a calculator; we give them a moral compass.

As Nobel Laureate Esther Duflo reminds us, ethical economic education is not about ideology. It is about humility, empathy and evidence. It is about empowering people to improve lives, not only their own, but others’.

So yes, give a child a piggy bank, and they may save for life. But teach them how economies work, who they serve, and what they exclude, and they will reimagine those systems with care. That is what it means to raise not just capable earners, but ethical citizens. And that is what we owe the next generation.

BY Dr. Helen Hoang

Dr. Helen Hoang is an economist, the founder and author of "Economics for Kids: Lessons from Fables to Fairy Tales," a series designed to make economics enjoyable and accessible for children. She advocates for early economic education through storytelling and real-world learning experiences.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Activist CEO’s. Is it any of your business?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

The ethical honey trap of nostalgia

Marvel’s in trouble. The once box office-dominating brand has hit every branch on the way down as of late, from cancelled shows to thinning audiences. So, consider it a sign of the times that the folks behind the behemoth have attempted to enliven their cinematic futures not by looking forward, but instead casting their gaze way back.

The Fantastic Four, the third attempt to make the family of superheroes work on the big screen, jettisons the usual digital sheen of superhero properties in favour of old-fashioned nostalgia. Set in an alternate, 1950s-style world, the film’s visual style and production values have been heralded as a bold break from the norm – which is funny, given how deliberately re–trotted they are.

Not only has ‘50s fantasy been done before in, y’know, the ‘50s, but we’ve already had multiple recycles of that trend, from the glossy world of Mad Men to the screwball textures of films like Down With Love. Marvel’s “new” style is not just a throwback. It’s a throwback of a throwback.

The antidote to irony

The film’s not alone in that open nostalgia, either. James Gunn’s Superman reboot attempts to make the gung-ho, gee-wizz character work by similarly leaning into an old-school fantasy, where journalism is heralded as truth-telling, and unabashed optimism is the name of the day. Then there’s Lena Dunham’s new rom-com series Too Much, which offsets its decidedly modern story with near constant references to Jane Austen-inflected romance, openly lusting after a bygone world where manners ruled the day, and sincerity was the default response.

This sudden rush of nostalgia can be read, above everything else, as a society trying to shake itself free of cynicism and layers of irony. The 90s saw post-modern go mainstream, with every cinematic hero affecting a wise-cracking, subversive mode, and over the decade and a bit after, that irony only got more layered. Eventually, you end up with someone like Deadpool, who can’t take a breath without acknowledging that he’s a character in a movie.

It was the writer David Foster Wallace who saw where this was all going to take us, writing over 20 years ago that “irony and ridicule are entertaining and effective, and that, at the same time, they are agents of a great despair and stasis in US”. Irony reduces and destroys, and is inherently oppositional in nature – not just aesthetically, but ethically, leaving us paralysed by our own smartness and subversion, without any energy left over to actually do anything.

And our need to do something is only greater than ever – as the world gets darker and more dangerous, it makes sense that we would turn back to the forward thinking and action of the ‘50s. The Fantastic Four and Superman come from a time where heroes actually believed that the world was a good place, and fought to make it even better. Being nostalgic for them means being nostalgic for proactive ethical agents, who, rather than spending their time brooding and moaning, fought for something. In short, it means being nostalgic for hope.

Nostalgia’s trap

But if we seek to distance ourselves from the dangerous trap of irony, then we should be careful to not run too open-armed into nostalgia. Nostalgia, after all, is its own kind of trap. Rather than making something genuinely new – something that responds to the world as it actually is – nostalgia is inherently regressive.

Philosopher Mark Fisher wrote about exactly this, seeing nostalgia as part of the “slow cancellation of the future”; the eradication of possibility and free-thinking. No wonder that conservatives the world over, Donald Trump chief among them, have aggressively nostalgic worldviews: nostalgia, when used improperly, can be a form of ethical despair and stasis too.

The nostalgia trap is laid bare in another film released this year – Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later. In the film, an isolated community trying to get by in a post-apocalyptic world, find their strength in visions of nostalgic Britain. In one montage, early in the film, two of our heroes making their way across a dangerous landscape are intercut with images of British soldiers at Agincourt, all scored to a Rudyard Kipling poem – Kipling being that hero of early British imperialism. The heroes in Boyle’s film try to survive and draw their strength from remembering how things used to be. And in turn, they end up trapped, locked into regressive and cruel worldviews that damage them.

That thesis is made shockingly clear in the last five minutes of the film, where the young hero (spoiler alert), finds himself saved by a roaming gang all made up of thugs dressed like disgraced pedophile Jimmy Savile. The young hero accepts them, open-armed. The kind of nostalgia that he has been raised on has no room for nuance. It’s essentially flattening, making a sort of caricature of England’s past.

In this way, Boyle criticises the nullifying effects of nostalgia: it casts the entire past as something to return to, without remembering its horrors and its shortcomings. If all we ever want to be is what we once were, then we will never truly change.

Nostalgia might be useful to energise us, but only if it’s used selectively and critically – if we aim to be better than what we once were, not merely the same.

As with so many things, we find our way forward through the mid-ground. Not just recreating the 50s, but taking what we want from it – the hope, the energy, the sense of optimism – and jettisoning what we don’t. The way to avoid the cancellation of the future, after all, is by believing that the future exists – that there’s still room, even now, to use the past to create something that has never occurred before.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Education is more than an employment outcome

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 30 JUL 2025

Sometimes good people do bad things. It’s important to understand why so we can respond ethically.

The news is filled with stories of everyday people doing bad things. A small business owner might underpay workers, a senior manager in a corporation could be cutting corners to improve profit margins, or a protester damages a precious artwork to promote their cause.

It’s natural to feel outrage when we hear about incidents like this. We might condemn the perpetrator and want to see them punished. But not every wrongdoer is a moustache twirling villain. Often, they’re otherwise good people who are perfectly ethical in other aspects of their lives. This makes their bad behaviour especially puzzling.

If we don’t understand what motivates their behaviour, then we risk responding in a way that won’t fix the problem, or might even make things worse. Here are four different reasons why good people do bad things and some ways to prevent or correct them.

1. Weakness of will

Temptation is everywhere. Sometimes we know something is wrong, but we are tempted to do it anyway because we know doing so will benefit us. The small business owner might be tempted to increase their profits by paying their staff below minimum wage. Or your neighbour could be tempted to poison a beautiful old tree that is protected by council because it’s blocking their view.

When we’re faced with temptation, and if we think we can get away with it, it takes willpower to stop us from doing the wrong thing. Yet, all too often, willpower is insufficient to stop us. This weakness of will, called “akrasia” by Aristotle, is one of the main causes of unethical behaviour.

There are two dimensions to weakness of will: the first is desire, which sits in tension with willpower. As such, one way to prevent weakness of will is to cultivate the virtue of self-control. However, it may not be prudent to rely on self-control entirely, given that it’s an all-too finite resource for many of us.

So, the other approach is to reduce temptation. That could mean removing the source of the temptation from our presence, like hiding the chocolate cookies in the cupboard rather than leaving them out on the kitchen table. It can also mean increasing accountability, such as through transparency and oversight. We’re less likely to be tempted to do something wrong if we feel we’re unlikely to get away with it.

2. Moral blindness

All too often, people simply don’t see that what they’re doing is wrong. Like the banker who is so focused on earning a commission that they turn a blind eye to money laundering. Or the manager who doesn’t realise that they keep unfairly promoting staff who have a similar ethnicity to them.

This is moral blindness. Sometimes it might be excusable, like if they had no way of knowing that they were causing harm. But, ignorance is not always an excuse. We must all be mindful of how our actions affect others, and we can’t avoid responsibility if we could have reasonably anticipated that our actions were unethical.

There’s also the problem of wilful obliviousness, which is where we avoid thinking too hard about what we’re doing because, deep down, we know it could be wrong. It’s like refusing to watch an exposé on animal abuse in farms because we don’t want to stop eating meat.

This is also a common phenomenon in workplaces, where workers can become distracted by chasing KPIs or boosting profits, and ethical concerns fall into the background. The Banking Royal Commission found many instances of wrongdoing because many financial institutions had a culture that rewarded sales over all else.

This is the danger of unthinking custom and practice. When people operate in a culture that is highly conformist, with incentives that reward unethical behaviour, they are less likely to reflect on or question whether what they’re doing is ethical.

One way to combat moral blindness is to create a culture of curiosity, where everyone is encouraged to reflect on and openly question their practices as well as the decisions of leadership. Another preventative is for organisations to be mindful of the goals they set and ensure they are not creating incentives to act unethically.

3. External constraint

Sometimes our hands are tied, and we’re forced to do something we know is wrong. In some cases, there might be nothing we can do to avoid the bad outcome, like a police officer who is forced to shoot someone who is threatening other people’s lives. In other cases, it’s because we’re faced with a moral dilemma, like choosing between keeping a promise to a friend or breaking that promise so they can get the help they need.

External constraints can lead to dirty hands, where someone is forced to do something bad to prevent something even worse from happening. In extreme cases, it can also lead to moral injury, which can cause them to lose faith in their own moral core and become detached or despondent.

An obvious way to prevent external constraints from leading to unethical behaviour is to remove the constraints themselves. That could involve anticipating problematic situations before they occur or making sure that people always have options to do the right thing. However, that’s not always possible. If so, then we should recognise that sometimes people do bad things because they had no other choice, which might result in us being more lenient when it comes to punishing them or correcting the behaviour.

Another way to deal with the problem of external constraints is to cultivate moral courage and moral imagination. Bolstering moral courage makes it easier for people to do the right thing, even when they know doing so might come at a cost. Moral imagination, on the other hand, helps people to expand their possible range of actions, and the chance they might find a way to get around the constraints.

4. Ethical disagreement

When an activist throws paint at a beloved artwork to protest the impact of fossil fuels on climate change, or your local childcare centre refuses to accept children who have not been vaccinated, you might think they’re doing something wrong, even though they are doing what aligns with their deepest moral principles.

We live in a highly diverse world, with countless different moral perspectives and multiple ethical frameworks to guide our behaviour. Until such time that humanity can come together and agree on a common set of values and principles to direct everyone’s behaviour, then ethical disagreement will persist.

One of the compromises we make to live in a liberal society is that we will tolerate some behaviour we believe is unethical, as long as others tolerate our behaviour that they consider to be unethical. Of course, there are limits to tolerance, but it means there will inevitably be cases where two different moral perspectives will clash. The danger is that it’s very easy to judge someone as being a bad person when they are actually acting out of an ethical motive.

This is not to say we can’t criticise them for doing it. Instead, the existence of ethical disagreement highlights the need to create spaces for people to engage with diversity in a safe and constructive way, and to know when we should tolerate or oppose someone else’s actions. If we’re able to recognise that someone is acting out of principle rather than malice, we might engage with them differently compared to going straight to condemnation or punishment.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why businesses need to have difficult conversations

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Reports

Business + Leadership

Trust, Legitimacy & the Ethical Foundations of the Market Economy

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster John Neil 24 JUL 2025

Society asks our teachers to juggle a range of morally rich roles: mentor, motivator, counsellor, disciplinarian, social worker, colleague, and even co-parent – all while guiding academic growth. Arguably the most important of these is being a role model of integrity.

Integrity is more than a momentary choice; it is a core around which personal identity is woven. Personal integrity shows up in daily promises we keep to ourselves – whether finishing a lesson plan after hours or practising a skill no one else will see.

Moral integrity, philosopher Lynne McFall argues, “consists in standing fast by the principles that define who we are”, even when convenience tempts us to drift. In classrooms, those twin forms of integrity are non-negotiable: professional codes embed them, students sense them, and communities scrutinise them. When public trust wavers, integrity is the educator’s most persuasive lesson.

Daniella Forster teaches teachers, and for many of her students, teaching will be more than a job – it’s a calling rooted in a commitment to make a difference for young people. This sense of purpose forms part of teachers’ moral integrity, shaping how they navigate the emotional and ethical demands of the profession. It is also something that can be learned. In class recently, one of Daniella’s pre-service teachers said “I guess as new grad teachers you feel like you can’t speak up, you feel like you don’t have a professional judgment, like you are not qualified enough, or you don’t have enough experience to make your own decisions. But no, you have a responsibility to protect your own integrity and be able to speak up for yourself.”

The multiple overlapping ethical responsibilities teachers are asked to fulfil create complex relational obligations that can challenge their personal boundaries and values. For example, a teacher in an under-resourced community may feel powerless to support students lacking essentials like books, food, or stability. Systemic issues, like poor funding and overcrowded classrooms, can leave them frustrated and guilty for falling short of their moral duty to provide quality education and care.

Enter EdEthics – a growing field that supports educators in confronting ethical dilemmas, much like bioethics does for healthcare. EdEthicists help shape ethical school cultures, guide policy, and offer moral clarity in times of crisis. During the pandemic, Daniella was part of a team of EdEthicists who offered teachers from seven countries guided discussions about the pressures they were facing and how they grappled with exacerbated moral challenges. Teachers expressed their relief in finding ways to interpret and articulate their ethical responsibilities and values and surface underlying assumptions that were examined more closely.

As education evolves, so too must our understanding of the ethical landscape teachers navigate daily. Strengthening moral reflection and support systems isn’t just good practice – it’s essential for a resilient and values-driven education system.

Moral psychology teaches us that knowing the right path doesn’t guarantee we’ll follow it. Most of us can recall a moment when we acted against our own standards and felt the sting of regret – sometimes only after seeing the fallout for others. Psychologists call the deeper wound moral injury: a breach that “ruptures one’s sense of self and leads to moral disorientation”. Moral injury strikes when circumstances push a person to betray their core values, fracturing the very integrity that guides action. It particularly faces teachers when they feel forced to act against their moral and professional identity. Teachers often face this strain when professional values collide, especially when policies offer little clarity on what should take priority .

A unique form of “teacher distress” according to researcher Doris Santoro is ‘demoralisation’, which occurs when teachers are no longer able to receive moral rewards such as when they can “believe that their work contributes to the right treatment of … their students”. Those who have a “strong sense of professional ethics are more likely to experience demoralisation than teachers who have a more functional approach to their work”. Demoralisation means some of its most vocationally committed teachers leave the profession, but there are ways to resist.

While teachers are primarily tasked with building meaningful relationships to support student learning, they work alongside professionals whose ethical priorities differ – school counsellors, learning support and administrators for instance. These colleagues may prioritise student wellbeing, compliance or test performance, creating tension in decision-making and collaboration. It can be a challenge, too, to raise moral uncertainty with colleagues, or to burden them with our concerns, and find safe spaces to talk with them about sensitive issues.

Moral emotions are one of the primary lenses through which teachers view their workday. Feelings such as gratitude, inspiration, pride – and on the darker side, anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, and shame – shape what we notice and how we judge it. These snap judgments crystalise into moral intuitions that steer classroom decisions in an instant. Shame plays a particularly potent role in moral injury. Where guilt condemns an action, shame condemns the self, making it a powerful catalyst for moral injury when educators feel forced to act against their principles.

It’s crucial that teachers develop expertise in how to identify and address ethical issues common in education and establish structured, collegial spaces for deeper reflection. It is difficult to do this during a school day, but important for self-care and the care of colleagues. Making space for safe, ethically guided dialogue along with the development of skills in identifying and responding to ethical issues in the profession is crucial.

What we wish to see is moral repair. When something feels off or goes wrong, it’s easy to jump straight into fixing the problem. But sometimes, what looks like a simple issue is actually part of something deeper. Undertaking moral inquiry can support moral repair. Asking ‘what went wrong?’ both reflectively and verbally with others as a form of interpersonal thinking, questioning assumptions and shared inquiry is a way to create an opportunity to reconstruct one’s habits and the structures which create harm.

Moral injury is not solved by becoming more resilient to factors causing stress at work. Rather, if teachers were to become more resilient to moral injuries against their professional values, this is likely to look like cynicism, defeat and moral detachment – resulting ultimately in ‘demoralisation’. Turning to EdEthicists – specialists in educational ethics – can help schools move away from harmful policies and toward practices that align with teachers’ living moral values. Their guidance supports educators in maintaining integrity, and the work of moral repair – finding a refreshed moral centre from which to teach.

Renewal begins by creating space for collective moral reflection. Creating structured, collegial spaces – after-school ethics circles, reflective supervision using ethical metalanguage and tools, teasing out case studies, or peer-mentoring sessions – where teachers can surface uncertainties and re-examine difficult moments without fear seeds the conditions for renewal and grows ethical confidence in the profession to navigate moral complexity.

If you are a teacher or educator interested in participating in a co-design process to develop professional learning to address moral injury, contact us at learn@ethics.org.au

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster

Dr Daniella J. Forster is an educational ethicist, researcher, and teacher educator with qualifications in philosophy and as a secondary teacher at the School of Education, University of Newcastle, Australia. An Australian leader in normative case study methodology, professional codes and moral dimensions of teaching, with a concern for education’s role in strengthening justice. Current 2025-2026 ADVANCE Research Fellow. Vice President of the Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia and Advisory Board member of Primary Ethics. Visiting Fellow with Justice in Schools/Ed Ethics at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Market logic can’t survive a pandemic

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Naomi Barnes 22 JUL 2025

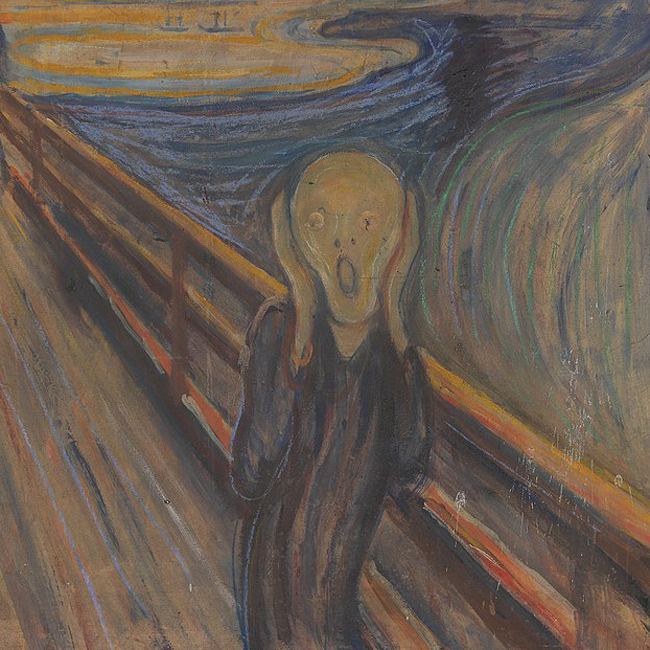

This is a story about moral panic: a familiar social pattern where fear swells, villains are cast, and quick solutions race ahead of careful thought. Like any good tale, it begins with a wolf.

Charles Perrault (1628-1703), grandfather of the modern fairy tale, knew that morality could be controlled through stories – such as those later adapted by the Brothers Grimm – like Little Red Riding Hood, where characters like The Wolf are easily understood as folk devils.

But morality plays, where the terrible actions of evil people teach us to be good, aren’t just a staple of fantasy: they are also a key feature of media storytelling. The British sociologist, Stanley Cohen, argued that the media creates moral panics by creating ‘folk devils’, which incite panic in the community. In a way, the media is saying the Big Bad Wolf is real.

We saw this in the 1980s, when the media fuelled the “Satanic Panic” that surrounded the tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons & Dragons, amplifying claims that it led to self-harm and Satanism. In this story, the children who played the game were folk devils, coordinating to corrupt their peers.

Many times, a moral panic is an exaggeration of a social challenge that does exist. It’s often based on real events, but the story is blown out of proportion, especially compared to other, more serious, problems. When something becomes a moral panic, we’re inspired to act fast, often without careful consideration or scrutiny of the narrative we’re fed. Its moral nature can more easily justify a harsh response because the stakes feel so high. This can lead to hasty or bad decisions, which can end up doing far more harm than good.

It’s important that we can identify the signs of a moral panic, so we can respond appropriately. Using a diagnosis tool with embedded ethical questions, like the steps below, can help us think critically about what we are being told. We can think about which bits might be exaggerated or amplified, and whether the solutions offered will actually address the core issue.

Prevention becomes prejudice

The first stage in the creation of a moral panic is the identification of a folk devil. Cohen noted that there are several clusters of who, or what, gets branded as a folk devil, with it often resting on pre-existing prejudices or stereotypes. Common candidates are young people, working class or violent men. Sometimes it’s new media, like rock music, social media or video games. Other times it’s groups that are often the targets of discrimination, such as single mothers, welfare cheats, refugees or asylum seekers.

One of the risks of a moral panic is that it becomes a mask for prejudice. Not all wolves devour grandmothers, just as not all young men are violent, or all childcare workers are predators. Although real danger can exist, moral panic begins when appearance, identity or difference becomes mistaken as a threat.

It is the leap from concern to caricature that makes a folk devil.

Once we know the villain, we construct the story. A challenge to the social order becomes a moral panic because of the way it’s communicated. When the media goes beyond describing something and injects morally judgemental language, using words like “thug” or “bludger” or “monster”, it is more likely to trigger an emotional response.

How the media and community tell the story also determines not just who the suitable enemy is, but who the suitable victim might be. The victim will be someone the public can easily identify, such as children or innocent girls and women, but typically someone everyone knows.

This next stage is crucial to how moral panic is sustained. This is where the media calls on public experts to comment. Religious leaders are often drawn in to help sustain concern about a social challenge as they are already framed as guardians of morality. Sometimes it’s academics or activists or the representative of a non-government organisation who is called upon to argue over the nuances of the case, lending it greater credibility.

Hasty solutions

A moral panic demands solutions. But, just as there is no rescuing Little Red without an axe, solutions can be extreme while temperatures run high. The very urgency of a moral panic can inspire us to look to options we might normally reject due to their high cost or because of the compromises involved. A moral panic might lead to blanket bans, a reduction in civil liberties or even calls for the death penalty.

This leads to the last step in a moral panic, when policymakers get involved. When the media, backyard barbeques, school pick up and letters to MPs are all begging the government to intervene, it’s more likely for the government to do so, lest it look weak or, worse still, complicit in the moral failing. But good policy can take years to develop, but a moral panic demands it is made fast, as seen with the Australian government’s youth social media ban. Sometimes that produces more problems while failing to solve the deeper underlying issues that contributed to the moral panic. Banning Dungeons & Dragons wouldn’t have solved the underlying mental health issues that triggered the panic in the first place.

The Big Bad Wolf never really left the storybooks, we just keep giving him new names, faces and new reasons to panic. There really are wolves out there, and we need to find ways to deal with them. But when temperatures run high, we risk offering fairy tale solutions to real-world problems.

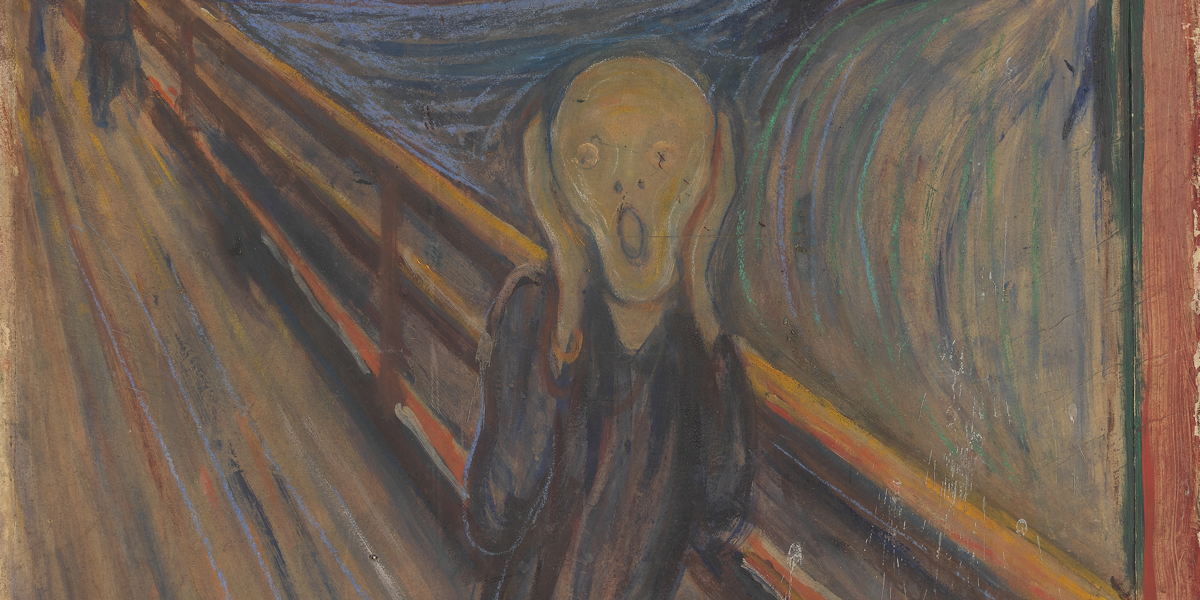

Image: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

BY Naomi Barnes

Associate Professor Naomi Barnes is a researcher at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) interested in how political actors perform and respond to crises. With a specific focus on moral panics and manufactured crises, she focuses on education politics in Australia, the US and the UK. Naomi is editor in chief of a forthcoming International Handbook of Schooling in Times of Crisis. Naomi is regularly asked to comment on how Australian teachers should respond to perceived threats to Australian nationalism, identity, and democracy. Naomi is the co-course co-ordinator of a future-focused Humanities and Social Sciences Curriculum Project at QUT and lectures future teachers in Modern History and Civics and Citizenship.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

There is more than one kind of safe space

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Tim Dean 21 JUL 2025

We’ve heard a lot about safe spaces recently. But there are two kinds of safe space, and one of them has been neglected for too long.

Like many universities today, new students at Western Sydney University are invited to use a range of campus facilities, such as communal kitchens, prayer rooms, parents’ rooms as well as Women’s Rooms and Queer Rooms. But there’s something that sets the latter two apart from the other facilities.

WSU describes the Women’s Room as “a dedicated space for woman-identifying and non-binary students, staff and visitors”, saying they are provided in an effort to “provide a safe space for women on campus”. The Queer Room is described as “a safe place where all people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or otherwise sex and/or gender diverse can relax in an accepting and inclusive environment.” The operative term in both descriptions is “safe”.

We have heard a lot about such “safe spaces” over the past several years. Yet as the number and type of safe spaces has grown, so too has the concept of safety expanded, particularly within United States universities. Many students now expect the entire campus to effectively operate as a safe space, one where they can opt out of lectures that include subjects that could trigger past traumas, raise issues they believe are harmful or involve views they find morally objectionable. The notion of safety has also been invoked to cancel lectures on university campuses by reputable academics because some students on campus claim the talk would make them feel unsafe.

In response, safe spaces have been criticised for shutting down open discourse about difficult or conflicted topics, particularly because such discourse has been seen as an essential part of higher education. Lawyer Greg Lukianoff and psychologist Jonathan Haidt have also argued that safe spaces coddle students by shielding them from the inevitable controversies and offences that they will face beyond university, contributing to greater levels of depression and anxiety.

However, all of the above refers to just a single kind of safe space: one where people are safe from possible threats to their wellbeing.

In a complex and diverse world, where people of different ethnicities, religions, political persuasions and beliefs are bound to mingle, there are good reasons to have dedicated places to where individuals can retreat, spaces where they know they will be safe from prejudice, intolerance, racism, sexism, discrimination or trauma.

But there is another kind of safe space that is equally important: one where people are safe to express themselves authentically and engage in good faith with others around difficult, controversial and even offensive topics.

While safe from spaces might be necessary to shield the vulnerable from harm in the short term, safe to spaces are necessary to help society engage with, and reduce, those harms in the long term.

And while much of the focus in recent years has been on creating safe from spaces, there are those who have been working hard to create more safe to spaces.

A safe to space

More than thirty years ago, philosopher and Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff AO, set up a Circle of Chairs in Sydney’s Martin Place and invited passers-by to sit down and have a conversation. In doing so, he effectively created a powerful safe to space. It was so successful that this model of conversation remains at the heart of how The Ethics Centre operates to this day, through its range of public facing events including Festival of Dangerous Ideas, The Ethics Of…, and In Conversation.

But the success of The Ethics Centre’s events – similar to any other safe to space – is that they don’t just operate according to the norms of everyday conversation, let alone the standards of online comment sections or social media feeds. In these environments, the norms of conversation make it difficult to genuinely engage with challenging or controversial ideas.

In conversations with friends and family, we often feel great pressure to conform with the views of others, or avoid topics that are taboo or that might invite rebukes from others. In many social contexts, disagreement is seen as being impolite or the priority is to reinforce common beliefs rather than challenge them.

In the online space, conversation is more free, but it lacks the cues that allow us to humanise those we’re speaking to, leading to greater outrage and acrimony. The threat of being attacked online causes many of us to self-censor and not share controversial views or ask challenging questions.

For a safe to space to work, it needs a different set of norms that enable people to speak, and listen, in good faith.

These norms require us to withhold our judgement on the person speaking while allowing us to judge and criticise the content of what they’re saying. They encourage us to receive criticism of our beliefs while not regarding them as an attack on ourselves. They prompt us to engage in good faith and refrain from employing the usual rhetorical tricks that we often use to “win” arguments. These norms also demand that we be meta-rational by acknowledging the limits of our own knowledge and rationality, and require us to be open to new perspectives.

Complementary spaces

It takes work to create safe to spaces but the rewards can be tremendous. These spaces offer blessed relief for people who all-too-often hold their tongue and refrain from expressing their authentic beliefs for fear of offence or the social repercussions of saying the “wrong thing”. They also serve to reveal the true diversity of views that exist among our peers, diversity that is often suppressed by the norms of social discourse. But, perhaps most importantly, they help us to confront difficult and important issues together.

Crucially, safe to spaces don’t conflict with safe from spaces; they complement them. If we only had safe from spaces, then many difficult topics would go unexamined, many sources of harm and conflict would go unchallenged, new ideas would be suppressed and intellectual, social and ethical progress would suffer.

Conversely, if we only had safe to spaces, then we wouldn’t have the refuges that many people need from the perils of the modern world; we shouldn’t expect people to have to confront difficulty, controversy or trauma in every moment of their lives.

It is only when safe from and safe to are combined that we can both protect the vulnerable from harm without sacrificing our ability to understand and tackle the causes of harm.

This article has been updated from its original publication in August 2022.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Explainer

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture