Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Elisabeth Shaw 23 NOV 2018

If the problem isn’t in your head or before your eyes, check your ethics.

Ethical decision making isn’t always easy. It can cause stress, anxiety and conflict. Elisabeth Shaw helps ease the tension.

We tend to see human suffering as having two separate branches: psychological and physical. Life events like loss, abuse, disasters or health issues blend the two together, but rarely do we consider including a third. Ethical.

Rita and her two sisters were grieving their mother’s death. Rita had been named as executor.

Over the last few months, Rita had been researching her family tree. She talked with her mother about her memories. Rita learned her mother had a boyfriend she left when she chose her father, and that she deeply regretted her decision.

In my experience as a team leader for Ethi-call, a helpline for people working through ethical conflicts and dilemmas, I commonly hear of peoples’ worry, anxiety and internal conflict about the decisions at hand. People who are anxious tend to ruminate, become preoccupied, sometimes withdraw from social supports and can have disrupted sleep. This can further compromise good decision making.

Research on emotions and ethical decision-making consistently notes the importance of fostering greater emotional capacity and skill. People who are stressed, tired or emotionally conflicted may find the requirement to make quick yet effective and sound decisions more challenging.

A couple of weeks before she died she confessed to Rita she had a son to that man. He had been offered for adoption – a decision that affected her whole life. Rita located the son through an online search.

But emotional maturity is a life-long project. When we are faced with an ethical decision, we have to act quickly and decisively. Sometimes the emotional capacity we need is not yet developed. What should we do?

We now understand unethical decision making tends to be more intuitive and automatic. By contrast, ethical decision making is rational, considered and deliberate. You may not be aware of the ethical dimension of your decision or that you’ve acted unethically – “it just seemed like the thing to do”.

She told her sisters, as Rita believed her mother would want her to find him and include him in the Will distribution. But her siblings were horrified at her proposal. “It’s him or us!” they said.

Stressed people often isolate themselves, making decisions based on anxiety, urgency and reactivity. Isolation is a major issue. Our desire to get rid of a burdensome problem can spur us to act quickly, without taking adequate time for reflection. We are also limited by our own imaginations and life experience.

Rita was torn in her loyalty to her mother, her commitment to family and her siblings. All options seemed flawed and her grief was compounding her distress.

Comparing notes with others can help us see more possibilities and calm ourselves enough to proceed effectively. At the same time, consulting too many people – or worse, the wrong people – can be equally distressing. Hearing conflicting, dogmatic opinions can be stressful as we worry about being judged negatively for declining to act on someone else’s advice.

What we’ve learned from our callers is that they want a pressure-free, neutral and objective space to explore their concerns. Without the bias of colleagues or close friends and the pressure of fast decision making, people can often find their own wisdom and create a reasonable and effective plan of action.

Ethi-call is one way to discover such a space, but it isn’t the only option. We can unlock our own ethical resources by reaching out to wise friends or mentors, allowing adequate time for reflection without being rushed or by challenging ourselves to think more creatively.

Rita thought she had to make a definite decision but she had more work to do before she could. Time was on her side – the probate process can be a long period and lots happened in her family in a short period.

Ethical issues are not always neatly resolved. They need to be deconstructed and disentangled, and achieving room to breathe and think is quite a lot in itself. Sorting out all the different influences, options and relationships takes time and careful thought. But taking care to find a framework to progress the decision, to come to a values driven plan and then live peacefully with one’s decision is work worth doing.

Was Rita leaping to conclusions about her mother’s wishes? Did her brother want to be part of the family at all? With time Rita was able to determine how she felt and how to act. What she ended up doing doesn’t matter. What matters is the way she reached her decision.

Are you currently dealing with an ethical dilemma? A conversation with an objective, independent person can really help. Book a free call with Ethi-call, our confidential ethics helpline.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

BY Elisabeth Shaw

Elisabeth Shaw is a clinical and counselling psychologist, CEO of Relationships Australia and Senior Consultant at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics Explainer: Anarchy

Anarchy isn’t just street protests and railing against the establishment.

It’s a serious political philosophy that believes people will flourish in a leaderless society without a centralised government. It may sound like a crazy ideal, but it’s almost worked before.

A hastily circled letter Aetched into bus windows and spray painted on walls. The vigilante anarchist character known only as V from V for Vendetta. The Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten singing, “I wanna be anarchy”.

Think of anarchy and you might just imagine an 80s punk throwing a Molotov cocktail in a street protest. Easily conjuring rich imagery with a railing-against-the-orthodoxy rebelliousness, there’s more to anarchy than cool cachet. At the heart of this ideology is decentralisation.

Disorder versus political philosophy

The word anarchy is often used as an adjective to describe a state of public chaos. You’ll hear it dropped in news reports of civil unrest and riots with flavours of vandalism and violence. But anarchists aren’t traditionally looters throwing bricks through shop windows.

Anarchy is a political philosophy. Philographics – a series that defines complex philosophical concepts with a short sentence and simple graphic – describes anarchy as:

“A range of views that oppose the idea of the state as a means of governance, instead advocating a society based on non-hierarchical relationships.”

Instead of structured governments enforcing laws, anarchists believe people should be free to voluntarily organise and cooperate as they please. And because governments around the world are already established states with legal systems, many anarchists see their work is to abolish them.

The word anarchy derives from the ancient Greek term anarchia, which basically means “without leader” or “without authority”. Some literal translations put it as “not hierarchy”.

That may conjure notions of disorder, but the founder of anarchy imagined it to be a peaceful, cooperative thing.

“Anarchy is order without power” – Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the ‘father of anarchy’

The “father of anarchy”

The first known anarchist was French philosopher and politician Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. It’s perhaps notable he took office after the French Revolution of 1848 overthrew the monarchy. Eight years prior, Proudhon published the defining theoretical text that influenced later anarchist movements.

“Property is theft!”, Proudhon declared in his book, What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government. His starting point for this argument was the Christian point of view that God gave Earth to all people.

This idea that natural resources are for equal share and use is also referred to as the universal commons. Proudhon felt it followed that private ownership meant land was stolen from everyone who had a right to benefit from it.

This premise is a crucial basis to Proudhon’s anarchist thesis because it meant people weren’t rightfully free to move in and use lands as they wished or required. Their means of production had been taken from them.

Anarchy’s heyday: the Spanish Civil War

Anarchy has usually been a European pursuit and it has waxed and waned in popularity. It had its most influence and reach in the years leading up to and during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), a time of great unrest and inequality between the working classes and ruling elite – which turned out to be a breeding ground for revolutionary thought.

Like the communist and socialist movements that grew alongside them, anarchists opposed the monarchy, land owning oligarchs and the military general Francisco Franco, who eventually took power.

Many different threads of the ideology gained popularity across Spain – some of it militant, some of it peaceful – and its sentiment was widely shared among everyday people.

Anarchist terrorists

While violence was never part of Proudhon’s ideal, it did become a key feature of some of the more well known examples of anarchy. First there was Spain which, perhaps by the nature of a civil war, saw many violent clashes between armed anarchists and the military.

Then there were the anarchist bomb attackers who operated around the world, perhaps most notably in late 19thand early 20thcentury America. They were basically yesteryear’s lone wolf terrorists.

Luigi Galleani was an Italian pro-violence anarchist based in the United States. He was eventually deported for taking part in and inspiring many bomb attacks. Reportedly, his followers, called Galleanists, were behind the 1920 Wall Street bombing that killed over 30 people and injured hundreds – the most severe terror attack in the US at the time.

No one ever claimed responsibility or was arrested for this bombing but fingers have long pointed at anti-capitalist anarchists inspired by post WWI conditions.

Could it come back?

While the law-breaking mayhem that can accompany a protest and the chaos of a collapsing society are labelled anarchy, there’s more to this sociopolitical philosophy. And if the conditions are right, we may just see another anarchist age.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Threatened by Muslim extremists, boycotted by Western activists, Ayaan Hirsi Ali (1969—present) has literally put her life on the line to promote her ideals of rational thinking over religious dogma.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali is a Somali born Dutch American writer best known for her fierce criticism of Islam – the religion of her birth.

She sprung to international notoriety in 2004, when a Muslim extremist killed her Dutch filmmaker colleague Theo Van Gogh, knifing a hand written letter into his chest which called for Hirsi Ali to die next. The extremist targeted the pair for making a film mocking Islam’s treatment of women.

This brush with death only strengthened Hirsi Ali’s resolve to champion her ideals of enlightenment values over religious intolerance. She went on to author four books condemning Islamic teaching and practice.

Fluent in six languages, Hirsi Ali regularly travels the globe on speaking tours, skewering Islam and its local defenders in her articulate, charming style.

She doesn’t appeal to everyone though. The controversial writer has drawn the ire of Muslims and left wing groups who accuse her of anti-Islamic bigotry. Loathed by fundamentalists, she is forced to travel with armed security.

From believer to infidel

Hirsi Ali’s 2006 autobiography Infidel chronicled her extraordinary life journey from devout Somali child to Dutch politician to celebrity atheist intellectual.

Born to a Muslim family, Hirsi Ali says she was five years old when her grandmother ordered a man to undertake a female genital mutilation procedure on her. As a child, she was a believer who read the Qu’ran, wore a hijab and attended an Islamic school.

Looking back, the writer could see all that was wrong with her upbringing – violent beatings, unquestioning faith and rigid enforcement of gender roles.

Hirsi Ali says she sought asylum in the Netherlands in 1992 to flee her father’s attempt to arrange her marriage.

In her new home, the avid reader devoured the writing of enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire, Mill and Locke. These authors taught her to question blind faith and instead embrace science and rational thought.

After working as a translator and researcher, Hirsi Ali was elected to Dutch Parliament in 2002. She used her platform to criticise Islam and Muslim immigration.

Islam ‘is the problem’

Hirsi Ali holds the view that the problem with Islam is not simply a minority of extremists who give the religion a bad name:

“The assumption is that, in Islam, there are a few rotten apples, not the entire basket. I’m saying it’s the entire basket” – Ayaan Hirsi Ali

She argues violence is inherent in the core Islamic text and this is something most Muslims fail to recognise.

According to Hirsi Ali, Muslims can be categorised into three groups.

First, there are “Medina Muslims”, who seek to force extreme sharia law out of their religious duty.

Second, “Mecca Muslims”, are a majority of the faith who are devout but don’t practice violence. The problem with this group, says Hirsi Ali, is they fail to acknowledge or reject the violence in their own religious text.

The third group, “Muslim reformers”, explicitly reject terrorism and promote the separation of religion and politics.

Hirsi Ali argues this third reformer group must overcome the extremists to win the hearts and minds of a majority of Muslims.

Feminist hero or anti-Muslim bigot?

Ayaan Hirsi Ali was initially seen as a feminist activist who championed the cause of oppressed Muslim women. After moving to the US in 2006, she’s associated herself more with right wing groups than women rights’ activists. She became a fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute and a regular interviewee on Fox News.

Married to historian Niall Ferguson, the couple have been described as “the Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie of the intellectual right”.

She has also tweeted her support for Brett Kavanaugh, who was confirmed to the US Supreme Court despite allegations of past sexual assault.

Hirsi Ali’s right wing views and harsh criticism of Islam has seen Western activists target her alongside Muslim fundamentalists.

In 2014, Brandeis University in the US reversed its decision to award her with an honorary degree following objections from students.

In 2017, she cancelled a planned visit to Australia amid security concerns and a petition protesting her speaking appearance.

The Southern Poverty Law Center – a US advocacy group famous for defending civil rights – once categorised her as an anti-Muslim extremist.

Hirsi Ali says she can’t understand why she’s become the enemy:

“It has always struck me as odd that so many supposed liberals in the West take their side rather than mine … I am a black woman, a feminist and a former Muslim who has consistently opposed political violence”.

But if terrorists don’t deter her, activists have no chance. Hirsi Ali will continue to tread her dangerous path to promote what she believes are true liberal values.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 NOV 2018

Being tied in a knot of lies, the danger of scepticism, micro-dosing LSD and dismantling bi-partisan politics were just some of the themes threaded throughout this year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

Thousands crossed the threshold into the Festival’s new home on Cockatoo Island. Two days, 31 sessions, and 45 speakers later, they left with a feast of ideas and new perspectives.

For the first time, the island’s unique location and new full-day festival pass meant that you could delve deeper into FODI than ever before.

Caliphate host Rukmini Callimachi shared aching stories of violence and honour in ISIS camps; conservative historian Niall Ferguson forced us all to rethink before we retweet; and pop-culture savant Chuck Klosterman had us empathising with the unlucky aliens who colonise us.

“Hard truths, fleshy realities, blunt edged disagreement and sharp new ideas – all mixed together with a throng of people in an iconic location that spoke alongside the artists and speakers. It was a brilliant amalgam, FODI at its best,” said Dr Simon Longstaff, co-founder, co-curator, and executive director of The Ethics Centre.

For the first time, the island’s unique location and new full-day festival pass format allowed FODI-goers to attend a number of the 31 sessions and delve deeper into different topics and viewpoints while enjoying talks and panels, art installations, ethics workshops and even a touch of cabaret!

Even the master-of-all-trades, Stephen Fry, couldn’t avoid the glamour. A standing ovation roared through Sydney’s Town Hall for his delivery of the inaugural keynote, The Hitch. In honour of his dear friend, the late Christopher Hitchens, Fry had the sold-out venue in oscillating between stitches of laugher and solemn agreement when he lamented the lost art of disagreement in an age of deepening extremes.

Thinkers from around the globe tackled issues of truth, trust and technological disruption, including Caliphate podcast host and New York Times ISIS foreign correspondent Rukmini Callimachi, British conservative commentator Niall Ferguson, AI man-of-the-moment Professor Toby Walsh, and pop-culture savant Chuck Klosterman.

The sold out festival drew crowds of over 16,500 seats across the weekend, with #FODI trending across social media channels all weekend.

The Centre is enormously proud of this festival which we started a decade ago to provide a space to talk about the issues that divide and baffle us without tearing tearing ourselves and each other apart. And we’re thrilled it’s been a continued success in 2018 with a fantastic new partner, The University of New South Wales Centre for Ideas, and a fitting new home.

If you weren’t able to join us, many of our sessions were recorded and we’ll be releasing them over the coming weeks and months.

We’ll keep you posted in our enews or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn for more release updates.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Get mad and get calm: the paradox of happiness

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

From capitalism to communism, explained

From capitalism to communism, explained

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 NOV 2018

Everything, from your clothes to your phone to the train you last caught, has gone through what economists call ‘the means of production’.

This is the way a commercial good or service is created and sold, all the way from its raw materials to how it arrives in your hands… or to your platform.

Most of these things (also referred to as capital) can only be created as a result of collective effort. No individual can reliably ensure everyone in a country of twenty-five million has a safe way to dispose of their waste or a place to go to when they’re sick. One person can’t even meet the most basic requirement of that population and ensure sure everyone is fed.

Of course, these things cost money to maintain. Whenever cost is involved, people want to know who pays. This is where it gets hairy. If one person owns ‘the means of production’, they have to pay for everything – and keep any and all profit made. If everyone involved owns ‘the means of production’ collectively, they share the cost – and any profit.

This is where the branches of different economic systems begin.

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic systemwhere the ‘means of production’ and resulting capital are owned by private individuals and businesses. It is based on voluntary relationships of supply and demand instead of centralised (usually government) planning.

This system is rooted in classical liberal philosophy and its conception of the rational, freethinking, autonomous individual. It claims market competition forces people to act in a way that benefits others, regardless of their intention.

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system borne out of opposition to capitalism where the ‘means of production’ are collectively owned and shared. It prioritises production for use rather than profit and achieves this through centralised planning – like a government.

The value of whatever is produced is determined by the amount of time and labour required, not market supply and demand. Socialism claims sharing resources and work according to need, rather than competition, creates a more equitable and secure society.

Communism

Communism is a utopian political economic system where a society is reorganised without hierarchy, states, money or class. The ‘means of production’ are shared communally and private property is non-existent or severely restricted. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the seminal political pamphlet on this, A Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Communism’s modern adherents claim it has not happened yet, while its critics cite Maoist China, Stalin’s Soviet Union, the Cold War, and many other historical crises to signal its danger.

Fascism

Fascism is an economic system based on self-sufficiency of the state, ethnic purity, and one-party ownership over the means of production. There’s usually a dictatorial leader and little to no tolerance of political opposition. Fascism claims the strength of a nation comes from unity and unity depends on fixed identities.

Though commonly associated with Nazi Germany, many other countries have been considered fascist at some point too, such as Brazil, Iraq and Japan.

Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire translates to ‘leave alone’ or ‘let them do’. Laissez-faire is an economic system that leaves transactions and trade free from government regulation, subsidies, tariffs, and privileges. It claims the economy is a natural system and the market is an organic part of it. Government interference hinders something nature can mediate.

Which economic-political system is best?

When discussing what economic system we prefer, it’s important to know what we’re talking about. The economies of most modern countries today are rarely pure capitalism or pure socialism. Most have a mixed capitalist system where private individuals or businesses make profit off labour, while operating within government regulations.

At the bare bones of economic theory, you find philosophy. Questions like ‘What is the purpose of government?’, ‘What is a human right?’, ‘What can we expect from our relationships?’, or ‘What does equality and justice look like?’ inform the different perspectives that manifest into policy.

Which one would you stand for?

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 NOV 2018

Your child is getting married. A mixture of pride, grief and trepidation have been gathering steam for a while now.

You don’t know how you’re going to feel on the day, but when you see your child go through one of the most ubiquitous rites of passage there is, you can’t guarantee there won’t be tears of love.

Except for one snag.

You don’t like their fiancé.

It’s heartbreaking. What should have been a moment of elation at your child’s joy is soured. You don’t understand why they’re making such a huge commitment to their partner or how you will live with that choice.

Perhaps you don’t think they’re good enough, or you don’t get along with them as much as you’d like. Maybe you see them bringing unhappiness into your child’s life – now or in the future. They might have strange attitudes to parenting or relationships. They might seem plain dangerous. Either way, there’s one question you’re asking…

What should you do?

In this situation, consider what a good parent looks like. Do they support, protect, and nurture their child? Do they allow them to make their own mistakes? Are they honest and fair?

Being honest may mean causing great hurt. Being fair may mean accepting the consequences of your child’s independence. Protecting your child may mean treating your fears as truth. But to what end? And by what means?

Wedding dilemmas splitting you in two? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you see through chiffon to make decisions you can live by.

On one hand, what actions present you as the person you want to be? Are they the actions of someone courageous, patient, and wise? Or someone petty, panicky, and controlling?

On the other hand, what actions risk damaging the relationship between you and your child? Or your future child-in-law? What situation necessitates speaking up? Or more drastic measures?

If you decide your concerns aren’t that serious, is there a way you could use this situation to build a stronger relationship with your child and a better understanding of the partner they love?

A lot of the time, when we are faced with an ethical dilemma, we see in binaries. Black or white, either or. Taking the time to slow down our thinking and consider the situation in different ways can help new pathways emerge – even if that means stepping back and living with the decisions another person has made.

So, before you end up expressing your reservations in panic, blame, and threats to boycott the wedding, take a breath. Step back, contemplate who you aspire to be as parent, what actions you feel are right and available to you and get creative.

If you or someone you know is experiencing violence and need help or support, please contact 1800RESPECT. Call 000 for Police and Ambulance help if you are in immediate danger.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 16 NOV 2018

Almost everywhere I go to talk about ethics, I face some variation of the question: ‘Why be ethical?’ The question flummoxes and depresses me.

That’s partly because I can’t help but feel the question is basically ‘What’s in it for me?’ dressed up with a bit of academic, devil’s advocate flavour. But it’s also because to ask that question at all, you’ve got to have a pretty bleak sense of who people, at their core, really are.

But all the same, there are lots of people who have set out to answer precisely this question. Most of them are somehow connected to the world of institutions — government, business, non-profits and so on. You know, all the groups who studies suggest are haemorrhaging trust.

There’s nothing wrong with answering this question per se — in fact, it’s an interesting and challenging project that’s challenged philosophers since more or less the time the disciplined divorced from theology. But the answers are leaving me more-or-less equally disheartened as the questions themselves.

One common answer has to do with trust. And the thinking fits pretty well into the carrot/stick dialectic. The carrot approach goes a bit like this: data tells us ethical organisations are more trusted by other stakeholders, recruit and retain better staff and might even make more money.

The stick approach goes like this: unethical behaviour leads to a decline in trust, which leads to increased regulation, reporting and accountability. It stifles innovation, restricts opportunities and costs money.

The second answer is alluded to in the discussion of trust: regulation. The reason you should be ethical is because if you don’t we’ll catch you and hold you accountable for what you’ve done. People can’t be trusted to do the right thing, so we introduce safeguards to stop them from doing the wrong thing.

These two arguments boil down to self-interest on one hand and fear on the other. They respond to the part of humanity that is self-interested, petty and manipulative. That’s not necessarily a problem — failing to manage this aspect of humanity usually leaves the most vulnerable to suffer — but it’s an incomplete picture of who we are.

“The more we conflate ethics with trust, regulatory standards or “enlightened self-interest”, the less space we allow for morality to play a salvific role — not just to stop bad, but to make good.”

About 250 years ago, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote The Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals. Kant, in his brilliant but not-very-pithy way, argued that the only thing that has true moral worth is what he called ‘the good will’. The good will is the desire to do good for its own sake — regardless of the effects. Here’s Kant at his most poetic:

‘Even if by some particular disfavour of fate, or by the scanty endowment of a stepmotherly nature, this will should entirely lack the capacity to carry through its purpose; if despite its greatest striving it should still accomplish nothing, and only the good will were to remain … then, like a jewel, it would still shine by itself, as something that has full worth in itself.’

I worry that the way we talk about ethics today makes the formation of a good will, or some variation on it, impossible. This is because for regulatory and trust-based approaches to ethics, there’s always something outside morality that serves as motivation. It’s Santa Claus for grown-ups: we behave so we get presents instead of coal. And I’m not certain it works — I’m not inclined to trust someone who has ulterior motives for gaining my trust.

What’s more, it’s not clear how this approach to trust applies to groups who don’t need trust — think ‘too big to fail’ — and don’t have to fear regulation (perhaps they’re the ones who make the law). What reasons do they have for doing the right thing? And how might they define the right thing in a more morally sensitive way than pointing to their clean hands in the eyes of the law?

What is missing from this picture is anything that might generate a deep understanding — and love — of what’s good. The more we conflate ethics with trust, regulatory standards or “enlightened self-interest”, the less space we allow for morality to play a salvific role — not just to stop bad, but to make good.

I wholly understand the desire to minimise harm, prevent wrongdoing and serve justice. I also acknowledge the utility value in speaking the language of people’s desires — if people have been taught to think in terms of outcomes and self-interest, we may as well turn it to our advantage. But the more we do it, the more we entrench a mode of thinking that is at best narrow and at worst antithetical to the moral life itself.

It might still be that in the great moral trade-offs of life, protecting the vulnerable is more important that my high-minded philosophy. But we should at least know what we’re turning our back on — because in stopping people from doing bad, we might be preventing them from ever being good.

This article was originally written for Eureka St. Republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The right to connect

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

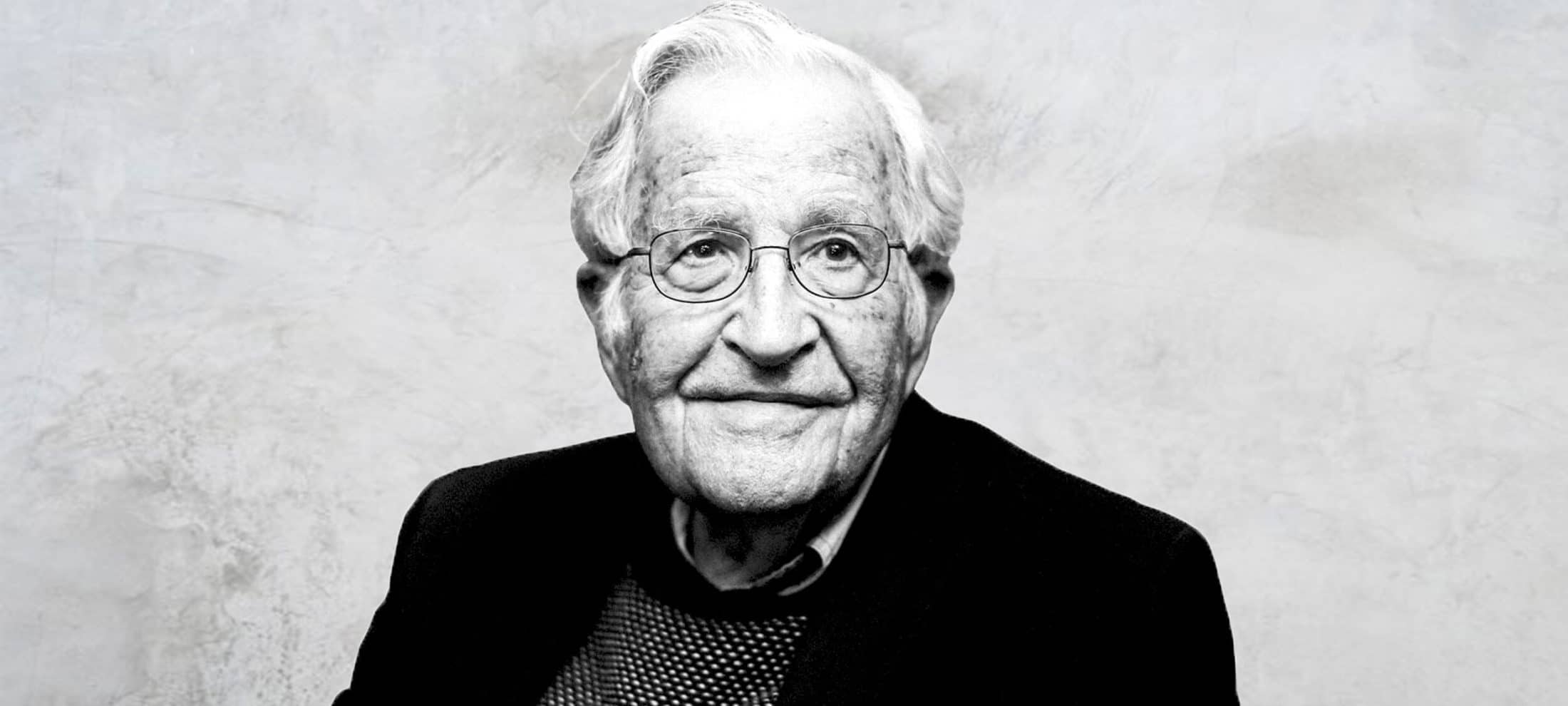

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 NOV 2018

Noam Chomsky (1928—present) is one of the foremost scholars and activists of our time.

With over a hundred books, thirty honorary degrees, and a generation of aspiring leftists behind him, Chomsky’s life puts a practical lens on the motto ‘protest is patriotic’.

The human tendency towards freedom

Chomsky earned a PhD in linguistics for his theory of “universal grammar”, a theory where all people are “born knowing” shared properties that underpin all human language. These properties, which create what he calls a “language acquisition device”, are what helps babies pick complex languages up instinctively.

According to Chomsky, while language’s laws and principles are fixed, the manner in which they are generated are free and infinitely varied. This view of human nature is one that runs through Chomsky’s attitudes to linguistics or politics: we must protect the innate human tendency towards freedom.

Pessimist of intellect

Chomsky’s opposition to war and totalitarianism started early. He wrote his first paper on the threat of fascism at ten. He opposed the Vietnam War while working at MIT, a military-funded university. He called Gaza the world’s “largest open-air prison” and said the US bears full responsibility for Israel’s war crimes.

Chomsky’s public denunciations of US foreign policy in Central America and East Timor, its interference in Middle Eastern elections and the shoot-first-ask-later’ type of diplomacy have drawn widespread ire and admiration. At the height of his fame in the 70s, it was discovered the CIA was keeping tabs on him and publicly lying about doing so.

Noam Chomsky’s consistent and vocal criticism of the US government comes from the belief that he, as a member of that country, holds a moral responsibility to stop it from committing crimes. That, and it’s far more effective than criticising a government that isn’t responsible for him.

“States are not moral agents; people are, and can impose moral standards on powerful institutions.”

Manufacturing consent

In what is arguably Chomsky’s most famous work, ‘Manufacturing Consent’, he outlined mainstream media’s complicity with government and business interests. He traced the capitalist formula of selling a product at a profit to the highest bidder in relation to the media. Here, people are the product and advertisers are bidding for our attention. Compare this with the monopoly social media has over our time and the ensuing competition for available ad space, and you’ll notice this line of argument growing in prescience.

Chomsky argued the advertising market is shaped by the external conditions of the state. It’s in their best interests to placate their ‘product’ and water down anything that would spur them to act against it. Any dissenting opinion is either ignored or presented as an anomaly. This is anti-democratic, said Chomsky, for a nation is only democratic insofar as government policy accurately reflects informed public opinion.

“If we don’t believe in free expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.”

Speak truth to power

Fred Halliday, an Irish academic, has criticised Chomsky for overestimating the power and influence of the US. Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, Oxford historian Stephen Howe, and linguist Neil Smith, have called him a fierce and aggressive moral crusader, who dismisses critics as unqualified, mistaken, or even “charlatans“.

Today, Chomsky is outspoken on what he considers the two greatest threats to humanity: nuclear war and climate change. But with NEG scrapped, the Doomsday Clock inching to midnight, and Congress split, it looks unlikely that decisive action against either of these threats will be carried out anytime soon.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 NOV 2018

Eleanor Roosevelt (1884—1962) was an American diplomat and longest serving First Lady of the United States, best known for her work on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

She was affectionately dubbed “The First Lady of the World”. The thread running through her massive body of work is the single idea: fear threatens our lives and our democracies.

To live well means to live free from fear

Roosevelt lived in a world reeling from fascism. Though the Second World War had ended, the horrors of Nazism, the Holocaust and Stalinism revealed the depths people would succumb to out of fear and insecurity.

It wasn’t your garden variety type of fear she was concerned with. It was the type of widespread fear that debilitates courage, rewards conformity and stifles “the spirit of dissent”. By succumbing to this immobilising fear, Roosevelt said, we waste our lives.

“Not to arrive at a clear understanding of one’s own values is a tragic waste. You have missed the whole point of what life is for.”

Roosevelt wanted all people to know their values. As an influential public figure and patriotic American, she especially wanted this for her country.

This wasn’t without reason. The growing fear of political others (McCarthyism) and racial others (the push for segregation) mobilised Roosevelt and emboldened her stance. She didn’t want conformity to win.

“When you adopt the standards and the values of someone else or a community or a pressure group, you surrender your own integrity. You become, to the extent of your own surrender, less of a human being.”

Find a teacher in every person you meet

Roosevelt felt the danger of fear and conformity went beyond the trauma of war. It could quash “a spirit of adventure”, a way of viewing and experiencing everyday life that made you a better person.

She wasn’t talking about a thrill seeking, you-only-live-once, way of navigating the world. She meant close mindedness – denying your life experiences the opportunity to change your mind and mould your actions.

“Learning and living are really the same thing, aren’t they? There is no experience from which you can’t learn something. When you stop learning you stop living in any vital or meaningful sense. And the purpose of life is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear for newer and richer experience.”

Roosevelt believed that everyone has something to teach you, and you are the ultimate beneficiary. Your character, your actions and your democratic polity.

And some might find being motivated by self-betterment alone to be selfish. After all, shouldn’t we do good simply because it is good? Isn’t it more noble to be motivated by what Kant called “good will”, or a moral duty?

Even if it’s possible that realizing motivation from a place of moral obligation is a higher ideal, Roosevelt was grounded in the everyday. She wasn’t concerned with principles the vast majority of a traumatised, distrustful nation would find out of reach, so she focused on the individual.

A principled life

The most remarkable thing about Roosevelt aren’t necessarily her ideals. It was her moral gumption to act on them even if they were unorthodox for the times or grossly unpopular.

She lobbied for greater intakes of World War II refugees when immigration was not supported by many Americans still reeling from the hardships of the Great Depression. She criticised her husband, President Franklin Roosevelt, for a policy intended to address the post-Depression housing market crash that segregated black and white citizens.

She broke with tradition by inviting African American guests to the White House. She spoke out against the internment of Japanese soldiers to the very population grieving the 2403 Americans they killed at Pearl Harbour (in comparison, it’s reported 55 Japanese lives were lost).

Roosevelt’s reputation for loving all has not gone unchallenged. She has been accused of taking sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a way that contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights she worked on. While famous for wanting to protect displaced post WWII refugees, who were often Jewish, she felt the solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict was to resettle indigenous Palestinians in Iraq – the suggestion being she had a Zionist bias.

Roosevelt nevertheless maintains her name as a pioneer in humanitarian efforts who walked her talk. Fast forward to today’s polarised political spectrum, and her story reminds us the tools to make it through are there.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The danger of a single view

There are times in the history of every nation when its character is tested and defined. Too often it happens with war, natural disasters or economic collapse. Then the shouting gets our attention.

But there are also our quieter moments – the ones that reveal solid truths about who we are and what we stand for. We are in one of those moments right now.

How should we recognise Indigenous Australians? Can our economy be repaired in an even-handed manner? How will we choose if forced to decide between China and the United States? How do we create safe ways for people seeking asylum? Can we grow our economy and protect our people and environments? These are just some of the questions we face.

And here’s another question. Do we have the capacity to talk about these things without tearing ourselves and each other apart? There are some safe places for open conversation about difficult questions. Twenty five years ago I began work at The Ethics Centre, a not-for-profit dedicated to creating such questions.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas is one such place. This weekend, 1400 Sydneysiders will gather at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas – in a brand new home on Cockatoo Island – to explore different views and perspectives on issues surrounding truth, trust and the battle of polarities in our society.

Why host a festival to explore dangerous ideas?

Sadly, there is a growing ‘fragility’ across Australian society. The demand for crystalline ideological purity (you’re completely ‘with us’ or ‘against us’) puts us at risk of a fractured and stuffy world of absolutes.

Too often, I see conversations shut down before they have even begun. People with a contrary point of view are faced with outrage, shouted down or silenced by others driven by the certainty of righteous indignation. In such a world, there is no nuance, no seeking to understand the grey areas or subtleties of argument.

“Attempts to prove to people that they are wrong just leads to stalemate. Barricades go up and each side lobs verbal ‘grenades’. There is another way. “

This phenomenon crosses the political spectrum – embracing ‘conservatives’ and ‘progressives’ alike. In my opinion, it is the product of a self-fulfilling fear that our society’s ‘ethical skin’ is too thin to survive the prick of controversy and debate. This is a poisonous belief that drains the life from a liberal democracy.

Fortunately, the antidote is easily at hand. In essence we need to spend less time trying to change other people’s minds and more in trying to understand their point of view – by taking them entirely seriously.

Why make this change? Because attempts to prove to people that they are wrong just leads to stalemate. Barricades go up and each side lobs verbal ‘grenades’. There is another way. We could allow people to work out what the boundaries are for their own beliefs. Working out the lines we cannot cross is often the first step towards others and can only happen constructively when people feel safe. Giving people the space to fall on just the right side of such lines can make a world of difference.

So I wonder, might we pause for a moment, climb down from our battle stations and call a cease-fire in the wars of ideas? Might we recognise the person on the other side of an issue may not be unprincipled? Perhaps they’re just differently principled. Can we see in the face of our ideological opponent another person of good will? What then might we discover about each other; what unites and what divides? What then might we understand about the issues that will define us as a people?

Let’s rediscover the art of difficult discussions in which success is measured in the combination of passion and respect. Let’s banish the bullies – even those who claim to be ‘well-intentioned’. They have no place in the conversations we now need to have.

Follow the #FODI conversation on Twitter, and keep an eye on our Instagram for on the ground action at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture