Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 12 FEB 2025

Many of us know how easy it is for our New Year resolutions to fail. And that’s ok, we’re only human. But how do we bring about change, if we want to?

For many people, the start of a new year is a time to make resolutions. For others, it’s a time to reflect on how to make the world a little better by becoming a little better as a person.

Unfortunately, for the majority of people, our commitment to change often fails and the gap between our intentions and actions can feel insurmountable. The Ethics Centre’s Director of Innovation and Education, John Neil says this is because, well, we’re human beings. He offers at least three factors behind this:

- We overestimate the power of ‘willpower.’ Often linked to adjacent concepts like resilience and impulse inhibition, the long-standing belief in psychology is that willpower is a finite resource and people have varying reservoirs of it to draw on. The belief was that by bolstering our willpower we’re better able to attain our goals and those that don’t achieve their goals lack willpower. Unfortunately, it’s more complicated than that. Our ability to maintain choices and attain goals is as much about situational context, genetics, and socioeconomic standing as it is about individual psychological traits.

- As a result, any significant behaviour change requires long-standing practice, environmental changes and thoughtfully designed behavioural cues to create pathways of reinforcement to form new habits. In short, even the simplest resolutions require habitual practice.

- Most resolutions are goal-focused – stop smoking, lose weight – so they take on instrumental importance, meaning they focus exclusively on achieving an end state or outcome. With the high difficulty in achieving these outcomes resolutions can become self-defeating – the end becomes the goal rather than a focus on the motivating reason that inspired the goal.

That’s not to say that resolutions are a bad thing. We are hard-wired to demarcate life into phases. Birthdays, seasons, events, and the change of year are all relatively arbitrary events but are full of symbolic significance. They are moments that matter because we invest these occasions with meaning. They can provide a much-needed pause in the busy and difficult aspects of life to reflect and reassess what’s important to us.

So, how can we reset to focus on what we want more of in our lives?

The Ethics Centre has developed Ethics Reboot, a new, free, online 21-day challenge designed to create better habits.

Rather than feeling the pressure to write down a long list of goals, that have little chance of sticking, the course asks you to think instead about the qualities you’d like to cultivate. What qualities for you express the best aspects of a life well lived? Which of those would you choose to have more of in your life?

Some philosophers refer to these qualities as virtues – those behaviours, skills or mindsets that are worthy to be regarded as features of living a good life. Wisdom, justice, and courage were on Aristotle’s shortlist.

Rather than setting goals like reading more books or spending less time on my phone – think instead of the quality you are calling more of into your world – like being curious, courageous or compassionate.

Ethics Reboot provides you with one new quality or virtue to focus on each day for 21 days. Each daily challenge will give you guidance, motivation and inspiration to bring that quality into your every day.

In the midst of busy lives – and an increasingly tumultuous world – the challenge of the course is to carve out a few minutes each day to learn something new, put it into practice and reflect on it’s impact in your life. The result? Creating a new habit of daily self-reflection that might just help kick-start new ways of thinking, being and doing life that little bit better.

The course kicks off from when you sign up and lasts for 21 days – just enough time to develop some fresh new habits. You can join by signing up on our website.

Each day you’ll receive:

- A daily email explainer introducing you to a new virtue

- A guided activity to help practice what you’ve learnt

- A reflection exercise to build your ethical muscle and integrate the virtue into your everyday

In a time where many aspects of life can feel tough, focus on what you can control. And you might just see that resolution through.

Take our 21-day challenge and sign up for Ethics Reboot here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is every billionaire a policy failure?

Is every billionaire a policy failure?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 29 JAN 2025

Is it fair that some people have more money than they can possibly spend while others are struggling to pay for essentials? It depends on what you mean by “fair”.

There’s never been a better time to be a billionaire. An Oxfam report released last week reveals that billionaires around the world have added a tidy $3.2 trillion to their wealth in 2024 alone. To put that in context: on average, each billionaire expanded their wallet by 3.2 million bucks every day over the last 12 months. That’s a tidy $400,000 an hour, or over 6,000 times the median hourly rate.

If you believe that innovation and hard work ought to be well rewarded, you might not be perturbed by these numbers. Except that the Oxfam report found that around 60 percent of the wealth captured by billionaires didn’t come from their labour, but was handed to them via an inheritance, or was secured through cronyism, corruption or their ability to exert monopoly power. So, there’s also never been a better time to have ultra-rich parents, or to have enough power to tilt the playing field in your favour.

Meanwhile, millions of hard-working people are struggling with cost-of-living pressures while their wages have stagnated. It’s probably no surprise that the phrase “every billionaire is a policy failure” – coined in another Oxfam report from 2023 – is having another surge in popularity.

But is the existence of billionaires itself a bad thing? Or is the existence of poverty the real problem? Should we change the way our economy works to make it impossible for someone to accrue that much money and power? Should we spread some of that wealth around to people who didn’t happen to be born with wealth and privilege?

These are not new questions. Ever since human societies started to accumulate wealth, inequality has been a hot topic for philosophers. But questions about inequality are fundamentally questions about fairness. The problem is that there are different ideas about what is fair.

Just deserts

One way to think about fairness is in terms of what someone deserves. Intuitively, if someone is talented, works hard and produces things that other people want, then they ought to be rewarded for doing so. A society that operates this way is often called a “meritocracy”.

This approach is often used to justify the vast wealth accrued by billionaires; presumably they’ve earnt their wealth because they’ve worked harder and smarter than most, and produced things that society wants or needs. And, on the flip side, many people assume that someone who’s living in poverty must be lazy or they made some dumb decisions, so they deserve their lot too.

But things aren’t so simple. Is it talent that we’re rewarding? Or is it effort? Or one’s contribution to society? Because what someone deserve differs depending on which we focus on.

If we focus on talent, then it’s clear that the world isn’t a level playing field. Some people are genetically endowed with higher intelligence, imagination or tenacity, or they’re born into a family that can afford a top-class education, all of which can give that person a huge boost to their talent. And, if they haven’t earnt any of those advantages, we might be reluctant to say they’ve earnt the disproportionate benefits that accrue because of them.

If we focus on effort instead, then the harder someone works, the more they deserve in return for their labour. Setting aside the question of whether tenacity is to some degree genetic, by this logic, someone who works long hours doing two jobs – as do many people to make ends meet – ought to be paid more than someone who earns a passive income from huge investments or a trust fund, let alone the significant proportion who were just handed their fortune.

Perhaps we should focus on contribution instead. Not all work is created equal. Some work only benefits the worker rather than society as a whole, and some is outright destructive or harmful. That brings us to the idea that people ought to be rewarded for what they offer society as a whole. No doubt, many billionaires own or head companies that produce things that people want. But is their personal contribution to society proportionate to the huge salaries they demand or the value of their share portfolio? Is a CEO really contributing more than hundreds of workers who actually produce the products and services? Many people would say no.

There are also many people performing essential jobs, like nursing, teaching and aged care, who are paid a lot less than people who just shuffle stocks around or who produce things like cigarettes or fast food, which are known to cause harm.

And there are plenty of people living in poverty who made all the right decisions in life but ended up unlucky. They’ve worked hard, taken risks – as all good entrepreneurs do too – and it just didn’t pay off, or they were struck by some illness or disability that prevented them from hitting the big time.

Libertarianism

There is another avenue of argument that has been used to justify the wealth of billionaires: libertarianism. American philosopher Robert Nozick argued that people have a fundamental right to own and trade property, and as long as they do so according to principles of justice, then they can accumulate as much as they want. In fact, taking someone’s property away and giving it to someone else, such as through taxation and welfare spending, is unjust.

Nozick’s argument harkens back to one offered by the English philosopher John Locke. Locke argued that raw natural resources, like land or minerals, start off belonging to no-one, and while they’re left idle, they’re worth nothing. But as soon as someone claims some natural resources (provided there’s still some left for others) and works or improves them to produce value, then they deserve to keep that value.

The problem is whether those who have amassed great fortunes today actually acquired their original property justly.

If it turns out that the property or resources they are using to generate wealth were appropriated from others, such as through conquest or colonialism, or if others were not given the same opportunity to put a fence around their own bit of nature, then the billionaires have received an unjust and unfair advantage.

Egalitarianism

If it’s the case that the world isn’t a level playing field, then perhaps we should focus less on what people currently have and do, and focus more on what they are owed as human beings. This brings us to egalitarianism. The most radical version states that every person, having fundamentally equal moral worth, has an equal right to share in what their society produces. According to this view, then everybody would have basically the same amount of wealth at all times.

However, this might not feel satisfactory if it means that people get the same amount regardless of whether they work hard or not at all, or whether they contribute to society or just laze around the beach.

Economists have also argued that a world where everyone has the same amount of stuff would be substantially less productive than a world where people are able to accumulate more resources and be rewarded for innovating and investing them efficiently. So, a world with perfect equality might see everyone living in poverty, while a world with some inequality might generate so much more wealth that everyone would, in principle, be better off.

This has led to yet another approach, called the “difference principle”, which was advocated by the American political philosopher John Rawls. Rawls argued that we should allow some inequality, but only if those inequalities end up benefiting the least advantaged people in society. So, it doesn’t matter if a few people accrue billions, as long as it means that the poorest people also benefit to some degree. One might imagine Rawls saying: “every billionaire is a policy failure as long as there are people in poverty”.

What’s fair?

No matter which way you think about fairness, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to justify the existence of billionaires in a world where millions of people are struggling to satisfy their basic needs.

However, while our economic system is geared to generate the maximum possible wealth, if we leave it alone to do its thing, inequality is likely to continue to surge. The challenge of tempering inequality falls into the political sphere, with mechanisms like taxation and welfare spending being highly effective at spreading wealth and opportunity around.

The problem is that those who are the beneficiaries of the current system – i.e. the billionaires – have a strong vested interested in preserving the status quo in order to maintain their wealth and lavish lifestyles. And it certainly helps their cause that wealth buys power and influence on the political level, as described in the Oxfam report.

Even if we can solve the question of how best to distribute wealth in our society, which is no easy task, we are still faced by an even harder question of how to change the system to make it just.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

The right to connect

The right to connect

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran 28 JAN 2025

Gen Zs are terrifying: we are the wizards of the digital world that is increasingly alien to the older generations.

We are hooked up by the veins to the ever flowing current of information and all of its chaos and simulacra, often seen as being emblematic of technology gone too far; escapists subsumed to a Matrix-like existence.

The other terrifying thing about us: we’re all mentally ill, apparently. So much so that Jonathan Haidt released a book about us called “The Anxious Generation”, expanding on the most popular explanation for rising mental illness in youth: the infamous ‘phone bad’ argument.

This claim has undeniable legitimacy: studies correlate social media usage with mental illness, including rising self-harm ER admissions for American teenage girls. There is no world in which a teen scrolling TikTok in their bed after a long day at school can defend their attention from a trillion-dollar organisation of world-class optimisers. Our generational psyche has been crafted into a consumer mind by a minority of technocrats.

In short, our generation has been raised into addiction. Understandably, this problem is now starting to drive policy, underlying a social media blanket ban for youth, as is being proposed by the Australian government.

I don’t think I would miss social media necessarily. But when I entertain what it would look like to close the portal to that void world, I do wonder: what then would I build on that empty plot?

My addict attention-span, whittled down to the duration of a good reel, attempts to ground itself firmly into the real world: OK, I’ve wasted so much time. I should focus on work — earning money. Money for what? Perpetual rent, until I can double my salary to buy a house. A house for what? My future family. But it feels unfair to have kids in this future, anticipating worsening climate disaster. Can I even manage a family when I can barely manage my own life? Or, well, this is kind of exhausting… I should relax… I’ll just quickly check Instagram to see if my friend sent something funny…

The checking is an itch. I scratch it compulsively when distracted, anxious, bored, or depressed, thereby gaining short-term relief. But like other types of addiction, while the object of addiction makes it worse, it is not the same as the source. Psychiatrist Gabor Mate’s mantra is: “Don’t ask why the addiction, ask why the pain.”

Perhaps my train of thought seems overly catastrophic — the kind of hysteria to be expected from the ‘anxious generation’. But the content of these anxieties driving addiction has real, material legitimacy, and they are not arbitrary. A home, a community, and a safe climate: these are frequently cited themes driving Gen Z’s anxieties.

They are recurring themes because they are how we connect to the outside world. Johann Hari wrote that the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety: it’s connection. A physical home is the cradle of our connection to a place; a safe base. A community and friends who know and care for us is our connection to people, allowing us to develop fluid and dynamic social identities. A safe climate represents the connection to any foundational future; a promise that our actions today are and will continue to be meaningful. Therefore, these basics are also our critical defences against addiction — or more precisely, they are the salve for the part of us that is drawn to the escape it offers.

When basic needs for connection have become unattainable fantasies, it is less mysterious why mental illness in youth may not be easily solved by unplugging.

Home ownership is a pipe dream rather than a mundane right in an absurdly land-rich city like Sydney. Neoliberal market logic reigns supreme over the provision of basic needs, treating houses as a class of speculative investment assets over functional shelter. Alan Kohler notes house prices have increased from four to eight times annual income in one generation. This is not just an aberrant property of Australia, but a global crisis as pointed out by the World Economic Forum.

This alienation is worsened by looming climate disasters which can uproot entire homes, as it does so for many people in rural communities and the global south, with its reach to the rest of the world only being a matter of time. Yet while three-quarters of Australians aged 18-29 believe climate change is a pressing problem, only ~50% of Australians aged over 50 do.

The epidemic of loneliness is also a global epidemic, according to the World Health Organisation. The average person has fewer and fewer friends, with Gen Zs feeling more lonely than other generations, including those aged 65 and over. On the flipside, young people increasingly engage in unsatisfying forms of intimacy like non-committal relationships (situationships) and AI personas such as Character.AI — forms of commoditised connection which, similar to social media, are exacerbating symptoms of disconnection rather than drivers.

There is a clear inequality in the opportunities to build physical, social and lasting connections between young people now and the older generations who also comprise most positions of power. Without recognising this structural unfairness, it is too easy to imagine mental illness as a linear consequence of technology, which incidentally has the unfortunate side effect of hysterical social complaints.

But our ‘hysteria’ is Janus-faced: yes, young people may be ungrounded, overstimulated and sensitive — but we are also flexible, intensely curious, and sensitive. Behind our grief is a quiet hope that needs to be understood and nurtured — never belittled. It is correct but incomplete to say that our generation is overly anxious and negative: many Gen Zs often through social media write letters to MPs, courageously reaching for environmental justice. When understood and armed with the right tools for connection and change, our sensitivity is a source of strength.

Fixing ‘phone bad’ with a blanket ban will not fix the root causes of mental illness, particularly for a generation with so few existing tools for coping and connection. Experts on digital media fear that a social media ban will further isolate already-isolated youth, and with social media being a nexus for youth activism, it will only serve to silence youth voices further. Practically speaking, this legislation has also failed to work in other countries. Fundamentally, the escapism of the digital world is driven by the hostility of the real world towards youth.

What the older generations owe us, then, is to form solutions that sincerely integrate the experiences of youth to treat the structural sources of illness: the lack of Gen Z’s physical security, social connection and a future. Technology should be regulated through a framework of harm reduction, recognising its role as an object of addiction.

Lastly, they should recognise that our visible vulnerability is not the sole problem but reflective of the system’s failures; in the age of climate collapse, we are canaries in a coal mine. That does not make us weak, but protectors of what is soft. And if we are no longer willing to create structures to protect the soft, then what, exactly, do we create our society for?

This is one of the Highly Commended essays in our 2025 Young Writers’ Competition over 18s category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran

Marlene Jo Baquiran is a writer and activist from Western Sydney (Dharug land), Australia. Her writing focuses on culture, politics and climate, and is also featured in the book 'On This Ground: Best Australian Nature Writing'. She has worked on various climate technologies and currently runs the grassroots group 'Climate Writers' (Instagram: @climatewriters), which won the Edna Ryan Award for Community Activism.

Big Thinker: Epicurus

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher and founder of the highly influential school of philosophy, Epicureanism.

In a time dominated by Platonism, Epicurus established a competing school in Athens known as “the Garden”. Many of his teachings were direct contradictions of the teachings of Plato, other schools of thought and generally accepted ideas in areas like theology and politics. He also flouted norms of the time by openly allowing women and slaves to join and participate in the school.

Though he strongly insisted otherwise, dubbing himself “self-taught”, records indicate Epicurus was greatly influenced by many philosophers of and before his time such as Democritus, Pyrrho and Plato.

Theology and Ethics

Two significant departures from the popular ancient Greek thought involved Epicurus’ ideas about theology. In general, he was critical of popular religion, though in a much more restrained way than his later followers.

One departure was his thoughts on the afterlife. Epicurus believed that there was no afterlife, and that any belief in it, especially the idea that the afterlife could involve punishment and suffering, was a harmful superstition that prevented people from living a good life.

“Accustom thyself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply sentience, and death is the privation of all sentience; . . . Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.”

From Letter to Menoeceus

Another departure was his thoughts on the gods, and specifically their involvement in human affairs, also known as divine providence. Unlike most, Epicurus believed in the gods while simultaneously believing that they were completely removed from the mortal realm and uninvolved in human affairs.

The Epicurean view of the gods was that they were perfect beings, and involvement in anything outside their perfection would tarnish that perfection. The view denies that they exhibit any control over humans or the world, and that they instead function mainly as aspirational figures – beings to admire and emulate.

Both of these departures from popular ancient Greek religion came from his unique hedonistic philosophy. Epicurus believed that the ultimate purpose of philosophy was to achieve, and help others to achieve, certain states of being that characterise the eudaimonic (happy, flourishing) life.

Specifically, he thought that eudaimonia was attained through internal peace (ataraxia), an absence of pain (aponia) and a life of friendship.

This was the basis of his hedonism – unique in that he defined pleasure as an absence of suffering and so had a far greater focus on moderation than what is typically associated with hedonism.

In fact, Epicurus was disapproving of excessiveness generally:

“…the pleasant life is produced not by a string of drinking bouts and revelries, nor by the enjoyment of boys and women, nor by fish and the other items on an expensive menu, but by sober reasoning.”

These ideas informed his theological thoughts. He believed that a belief in the afterlife was superstitious and bad because it was most often a source of fear. Instead of acting morally to avoid the risk of punishment in the afterlife, which causes suffering in the current life, Epicurus taught that we should instead act morally because we will inevitably suffer from guilt or the fear of being discovered if we do not.

Likewise, he taught that while the gods had no interest in the affairs of humans, we should still act morally and kindly because those who do will have no fear, leading to ataraxia.

“…it is not possible to live pleasurably without living sensibly and nobly and justly.”

Pleasure and Desire

As part of his ethical teachings, Epicurus noted different types of pleasures and desires that prevent us from achieving a life free from suffering and trouble.

He was particularly focused on desire because he saw it, like fear, as a ubiquitous source of suffering. He taught that there are three kinds of desires: two natural, and one empty. Natural desires can be necessary (like food or shelter) or unnecessary (like luxury food or recreational sex). Empty desires on the other hand correspond to no genuine, natural need and often can never be satisfied (wealth, fame, immortality), leading to continuous pain of unfulfilled desire.

Unfortunately, like many Hellenistic philosophers, the vast majority of Epicurus’ writings have remained undiscovered, instead pulled together largely through the writings of contemporaries, followers and later historians. Despite this, his ideas have resurfaced throughout the centuries since and influenced the thinking of ancient and modern philosophers alike.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Survivor bias: Is hardship the only way to show dedication?

Survivor bias: Is hardship the only way to show dedication?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 21 JAN 2025

Survivor bias assumes a direct link between sacrifice and success, which risks creating rigid and unhealthy work cultures.

Meeting with young people in business can give a fresh perspective on an organisation’s culture. They bring new ideas and a clear view, often unclouded by the blind spots experience can create and their expectations for work are shaped by a completely different set of values and norms compared to previous generations. From seeking work/life balance to finding meaningful work, these evolving values can sometimes clash with the more traditional belief that success requires long hours, stress, and personal sacrifice. At a recent Young Person’s Alliance gathering, this tension was brought to light and named: survivor bias.

Survivor bias happens when those who’ve faced tough paths to success believe that’s the only, or the best, way to achieve it. For example, many senior leaders in corporate environments, particularly women in male-dominated fields, often had to adopt intense work ethics and make personal sacrifices. Stories of working late into the night or juggling work while caring for sick kids are worn as badges of honour.

This can lead to an expectation, conscious or not, that younger employees should follow the same path: that sacrifice builds resilience and proves commitment. “I’m actually really proud of the struggles I had, it taught me a lot and it’s made me who I am today. You miss out on that if everything comes easy”, remarked a senior leader.

But is hardship the only way to show dedication? Or is this bias simply a product of individual survival stories?

In conversations I’ve had with finance or law workers, this bias shows up as an “all or nothing” mentality. Leaders who built their careers on 80-hour weeks might see flexibility or work-life balance as a lack of commitment. For instance, a senior female executive who climbed the ranks through relentless hours said “We just got on with it, no one was holding my hand.”

While this impacts both men and women, the pressure is often greater for young women trying to balance career and family. Survivor bias fosters a “suffer to succeed” culture, where personal sacrifice feels like a necessary step toward leadership.

Survivor bias can also create a scepticism that can create a lack of generosity in the workplace as about resourcing good mental health opportunities such as counselling or other support and even stagnating salaries as leaders reflect on their own experiences. “I remember when I went through that in my life, I got through it ok, and I didn’t have nearly the same help as there is today”, said a senior not-for-profit leader.

This mindset isn’t limited to the business sector. It’s seen in politics, sports, law, and even nursing. Serena Williams, for example, has spoken about the pressures she faced to prove her dedication to tennis after becoming a mother. Similarly, Julia Gillard’s time as Prime Minister is often framed as a testament to resilience, overlooking the intense sexism and personal costs she endured to succeed.

The danger of survivor bias lies in how it normalises burnout and undervalues the priorities of today’s workforce, like mental health and diverse perspectives. It assumes a direct link between sacrifice and success, which risks creating rigid and unhealthy work cultures.

It looks to ‘survivors’ as the standards people should aspire to but the word survival itself represents the limited few who have overcome the odds at all costs.

The first step to tackling survivor bias is awareness. By reflecting on how past struggles have shaped their expectations, leaders can start recognising this bias. Mentoring programs can also foster conversations across generations, allowing senior leaders to share their stories while understanding new ways of thinking about resilience and success.

Many organisations already have flexible and inclusive policies like parental leave, but true change requires a shift in mindset. Leaders can redefine hard work to focus on efficiency and impact rather than hours worked. This sends a clear signal that organisations value healthier, more innovative approaches.

As we engage with a new generation of professionals, especially young women, there’s an ethical responsibility to create paths that don’t equate suffering with commitment. By challenging survivor bias and embracing the values of today’s workforce, we can build cultures where resilience, fulfilment, and success go hand in hand.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Money talks: The case for wage transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 17 JAN 2025

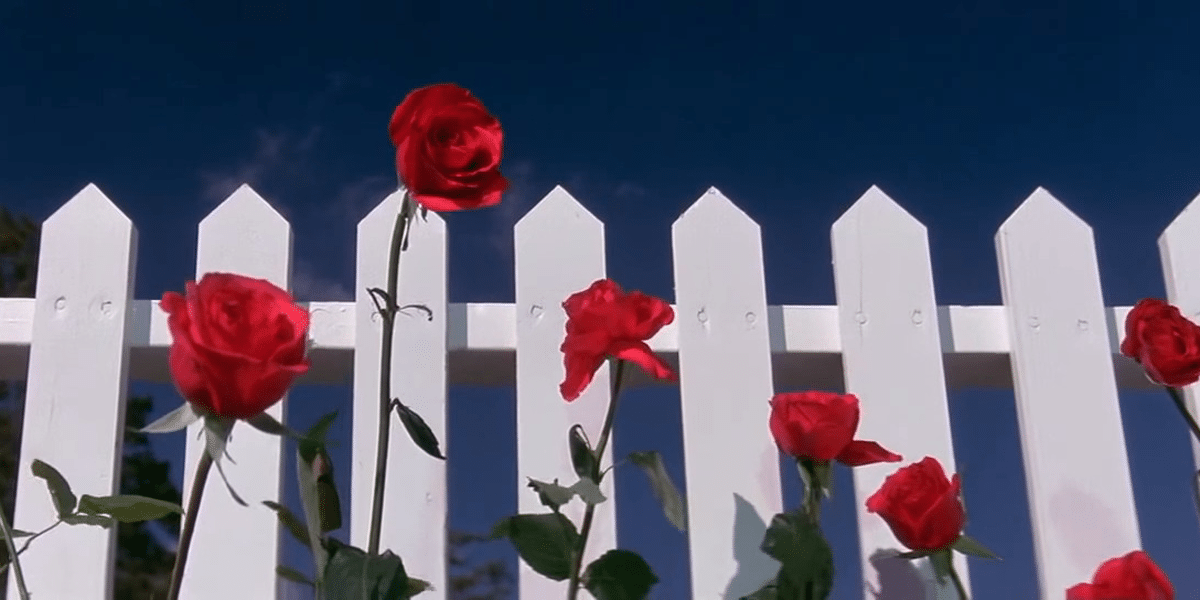

David Lynch’s Blue Velvet – the film that turned an outsider auteur into something approaching a genuine cultural sensation – is, even after all these years, a hard watch.

The film sets up its thesis almost immediately. A montage of quaint images of small-town life, all blue skies and white picket fences, is disrupted by tragedy – the father of the film’s hero, Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) collapses in his yard, killed by a heart attack. The man’s dog laps at the hose clung in his dead, tight hands. And then Lynch’s camera, still exploring, does something both beautiful and terrible: it burrows under the soil, where a nightmarish cacophony of insects forage.

So there it is, Blue Velvet’s message – that beneath Americana, with its bright smiles and cups of coffee, lies horror. From that starting point, rape, torture and abuse abound, as Jeffrey’s voyeurism sends his path crashing into the orbit of Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper, in one of cinema’s most terrifying performances, all gritted teeth and mummy issues). We watch Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) get tortured in various ways; we see Jeffrey beaten and humiliated. And perhaps most unsettlingly of all, we come to realise that the likes of Frank, a personification of pure evil, are more plentiful than we might ever want to believe. Even, if not especially, here, where the skies are blue.

The world is wild at heart and weird on top

Much has been made of this quality found in the films of Lynch, who died today after a battle with emphysema – the contrast between ethical virtue, and deep ethical horror. Throwing up these two disparate forces – good and evil – was the modus operandi of Lynch’s one-of-a-kind career.

Twin Peaks, his hit television show, unraveled the angelic exterior of murdered teenager Laura Palmer, and pit her against another of Lynch’s satanic figures, the supernatural drifter Bob. Wild at Heart, one of the more underrated films he ever made, plunged a loving young couple, Sailor and Lula, into an impossibly evil world. And The Elephant Man, a black-and-white muted howl of pain, saw a man with disabilities try to find hope amongst objectification and cruelty.

But what is not often discussed about Lynch is that he did find beauty, time and time again. Contrary to what some have written, Lynch’s veneer of smiles and blue skies wasn’t some ironic posturing, established merely to make the horror more horrifying. Other filmmakers have untangled the way that evil thrives in darkness, out of sight – that’s not what made Lynch special.

Lynch’s power – his genius, even – is that he believed fully in both of the forces that make the world what it is, the darkness and the light.

This is a rare sort of ethical dialectics: rare both in art, and in our personal lives. Believe too deeply in the evil of the world, and you will simply never get out of bed. Ignore that evil, and strive forward as though it isn’t there, and you will fall prey to an ignorance that will make you a poor ethical actor. The real trick in all things is to understand that truth, if we ever find it, exists in the middle of extremes.

Hence the model of the archetypal Lynch hero: Dale Cooper (MacLachlan, again), the handsome, profoundly odd detective hero of Twin Peaks. Dale has a goofy, almost unrepentant enthusiasm. He loves coffee; he loves pie; he loves the town of Twin Peaks. He’s all broad smiles, and dorky thumbs up, perpetually grinning to the small town residents that come to love him. But this optimism doesn’t exist in spite of the darkness of the world – it exists because of it.

That understanding is expressed through his deep affection for Laura Palmer, the dead young woman he never met. The more he learns about Laura, believed by the town to be the perfect all-American girl, the more he loves her, even as he comes to see the precise shape of her demons.

Lynch’s lesson is contained here. Cooper doesn’t choose to believe in the goodness of people at the expense of acknowledging their capacity for great harm. He understands that the world is built, in many ways, for cruelty to flourish; for abusers to thrive, for casual unkindness to go unremarked upon. And he also understands that, surprisingly, time and time again, human beings will decide to love each other.

The art life

This complicated optimism was also at the heart of Lynch’s deeply inspiring life outside of filmmaking. Like Cooper, Lynch was a famous lover of little treats, the kind of tiny slithers of goodness that aren’t just a distraction from the world – they are the world. There are countless memes of Lynch expounding the beauty of a good cup of coffee; enjoying two cookies and a Coke in the back seat of a car; and, perhaps most movingly of all, speaking lovingly of the importance of what he called “the art life.”

For Lynch, the art life was painting, thinking, and making things with your hands. “I had this idea that you drink coffee, you smoke cigarettes, and you paint, and that’s it”, Lynch said once, happily. There is horror in this world, but being an artist isn’t just an aesthetic choice – it’s an ethical one. Being an artist means being curious; looking; creating.

Rather than being swamped by the inexorable downward slide of humanity, the artistic life allows one to see the things that make us, at the end of the day, so blessed. So loved.

Blue Velvet contains that hope in its final scene. After taking a long drive through hell, the film wraps up not with an image of suffering or pain. Instead, one of its last shots is a robin sitting on a branch. A robin – that most ordinary of birds, so small as to be invisible, but a symbol, built up over the course of the film, representing love itself. “Maybe the robins are here,” Jeffrey says, cautiously. But, despite it all, they are.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

How to live a good life

What do you need to flourish in life? Philosophy and science suggest there are six key ingredients.

How do you decide where to live, what work to do, what kinds of relationships to cultivate and generally what kind of life to live? These are some of the most important questions we can ask, and the answers we arrive at can have profound impacts on whether we end up flourishing or miserable.

At the heart of these decisions is some implicit idea of what a good life looks like. But which picture should guide our actions? There is no shortage of voices selling us a range of visions of a good life, including our family, the media, pop culture, our workplace and, of course, advertising. We might hear that we should pursue wealth, status, success, comfort, happiness, etc., but philosophers and scientists have shown that these goals don’t necessarily lead to a better life.

So how should you guide the big decisions in your life? Here are six pillars that make up a good life.

Wisdom

Socrates famously said “the unexamined life is not worth living”. This relates to what we call wisdom. It’s a precondition that enables us to understand what a good life is, as well as gain knowledge about ourselves, what makes us tick and what causes our suffering.

Gaining wisdom is a life-long pursuit that requires a healthy dose of what we call ‘loving self-scepticism,’ because we are so good at fooling ourselves into taking the easy option rather than one that will be genuinely rewarding.

You can start cultivating wisdom by engaging in mindful behaviour, where you focus on being aware of your own internal state as well as what’s around you, rather than just running on auto-pilot all the time. You can deepen this by practicing meditation, but that’s not a requirement. Simply acknowledging what’s happening, and then taking time to reflect on it with a critical eye and an open mind can help you to better understand yourself and the world around you.

Purpose

Purpose means pursuing meaningful goals. Of course, many of the goals we pursue are imposed on us, whether that’s due to life’s necessities or because of our responsibilities. But we can also create goals for ourselves, and these often guide our big decisions, such as what career to pursue or whether to become a parent.

The key is pursuing meaningful goals that connect with our intrinsic aspirations rather than just pursuing things that seem important, like money or status, but that don’t actually help us flourish. An intrinsic aspiration is something that you find meaningful in its own right, and these are often activities that don’t just benefit ourselves, but have a positive impact on the world and other people. This could be through the work you do, helping other people in need or bettering your environment, or it could be through the time you spend caring for your family. There is abundant evidence that people who toil to help others report greater life satisfaction, even if they receive less money and status than if they did an easier job.

Agency

Agency is connected to the work we do in the world – your ability to have a sense of control in your life and to attain and practice mastery in what you do.

We probably all know that feeling when we’re deep in a task, using and stretching our abilities, we’re fully present in the moment and lose all sense of time. That’s called a ‘flow’ state, and it’s an indication that you’re exercising your agency. The task itself might even be unimportant: perhaps you’re creating art or music that no-one else will ever see or hear, but it’s in the making that you experience your agency. Some people can connect purpose and agency, and strive for mastery while doing meaningful work – but that’s not required for a good life.

Intimacy

Intimacy speaks to our fundamentally social nature. This means more than just having a lot of friends, in the real or online worlds. Casual friends are fine, but what is truly nourishing is having at least a few close friends, the kind of people around whom we can be our authentic selves, express vulnerability safely, and feel like we are seen and understood while reciprocating back. This could be your partner, but you can also have intimate friends. You don’t need many intimate relationships like this to flourish. Even a handful can give help you live a good life.

Of course, intimate friendships are not easy to cultivate, not least in the massively anonymous, technologically-mediated world many of us live in. One way to build meaningful friendships is to seek out people with similar values to you, whether that be through shared activities or just by keeping an eye out for people you admire and click with.

The trick is then to move from a superficial relationship into a closer one. While we often expect that we have to project our best, most confident and successful persona to the world, it’s actually when we lower the mask slightly, and reveal a bit of who’s underneath – including our uncertainties, anxieties and vulnerabilities – that we can build a deeper connection with someone, especially if they are willing to lower their mask in turn. We can do this by practicing what’s called escalating self-disclosure. This is about gradually lowering that mask and building trust and respect, which can then lead to a closer relationship.

Belonging

In addition to a few intimate friends, we also need to belong. This means that we feel like we’re a member of a social group that we care about, and that we’re seen, recognised and respected by other members of that group. This dimension of social life is often overlooked in modern society, which tends to promote atomic individualism, neglecting the importance of group identity.

We probably already belong to several different identity groups, whether that be connected to ethnicity, religion, local community or even our profession or a hobby. But cultivating a sense of belonging means more than just sharing some customs or activities, it means contributing something meaningful back to that community, and being proud of what your group represents – while also ensuring that belonging doesn’t slip into insularism or elitism.

Elevation

The final pillar of a good life is perhaps an odd one, but is no less important for many people. Elevation is captured in those experiences where we forget about ourselves, our problems, goals and anxieties for a moment, and we allow ourselves to sink into the background, focusing instead on the wonders of the world around us.

We can find elevation by spending time in nature or contemplating the vast stretches of space and time at an observatory or museum. We can find it by connecting with our ancestors by studying history or by walking through a cemetery. We find elevation by recognising the sacred is all around us, not just in religion, but in the rituals, objects and places that we hold dear. We can also experience elevation by acknowledging remarkable people around us, such as those who have performed great acts of kindness, compassion or self-sacrifice. Elevation reminds us that we are just a small part of a bigger system, and it helps us to escape our self-obsession and appreciate the world we live in.

Of course, there’s a lot more to each of these pillars, and different ones will resonate with different people based on your ability to choose how to live your life. But consider this guide to help you start the process of self-examination to discover what constitutes a good life for you.

Ethics Tune Up is an innovative and engaging masterclass series that will take your ethical skills to the next level. Our next series of workshops is running during May and June 2025. Book your tickets here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 7 JAN 2025

If I were a reviewer at a writers’ festival and I spotted an author whose work I’d praised – but also criticised – I’d be tempted to look the other way.

But, far from avoiding Christos Tsiolkas at last year’s Canberra Writers’ Festival, literary critic and Festival Artistic Director, Beejay Silcox chose to share the stage with him.

When asked if she felt uncomfortable, Silcox said that because she felt she’d done her job well – reflecting on the work, dealing with it on its own terms, choosing her words carefully – she didn’t. If she couldn’t be honest about “the loveliest man in Australian literature”, she didn’t deserve her job.

She did, however, describe that job as “inherently uncomfortable”. It’s the reason people often call her “brave”. But Silcox doesn’t share their view. “If what I do counts for bravery in our culture, we are f*cked,” she told the audience. “I know what bravery looks like; I’ve seen brave people. I’m just being honest.”

Point taken. There’s a difference between being honest and being brave. Honesty might require bravery, but the words aren’t interchangeable. If we use words like “bravery” too readily, we broaden its definition and reduce its potency.

It was the expanded application of certain words, that led psychology professor Nick Haslam to coin the term “concept creep”. More than a decade ago, he started noticing the widespread adoption of certain psychological terms in non-clinical settings was broadening people’s conceptions of harm. In a recent ABC interview, he said more expansive definitions of terms like “abuse” and “bullying” have had clear advantages, such as making it easier to call out bad behaviour. But mistakenly framing an unpleasant experience as “trauma”, or speaking as if ordinary worries constitute anxiety disorders, can make people feel, and become, more fragile.

This year, Australia introduced legislation that gives employers a positive duty to protect workers from psychosocial hazards and risks. It’s right to recognise that psychosocial harm can be as damaging as physical harm, but it’s important to understand what psychological safety isn’t. As Harvard business school professor Amy Edmondson stresses, it isn’t “feeling comfortable all the time”. It isn’t simply safety from discomfort, it’s safety to engage in conversations that might be uncomfortable. A manager should be able to gently raise an issue with an employee that might make them feel uncomfortable, without being accused of deliberately “violating” their safety – and vice versa. But I’ve heard managers, and educators, express concern that even well-intentioned, carefully delivered, feedback, could be perceived as an attack.

We can be uncomfortable and still be safe. If we lose this distinction, if managers in workplaces and teachers in schools, parents in the home and politicians in parliament, feel obliged to keep everyone comfortable all the time, we’ll end up in dangerous territory. We’ll be less able to express our views, and less able to hear each other out, less able to learn from each other.

Honest, measured, criticism plays an important role in society. We need to value it; even (perhaps especially) if it’s hard to hear. We also need to recognise that avoiding exposure to any and all discomfort will only heighten the sensation; and consider the merit, case by case, of facing it.

So, what might this look like?

C.S Lewis said that if you look for truth, “you may find comfort in the end”, but if you look for comfort, “you will not get either comfort or truth”. He wasn’t talking about performance reviews or reports or assignments, but the principle is still relevant.

If I seek the truth about my performance at work, I might find ways to improve it, gaining competence and confidence. A by-product will be a broader comfort zone. If I only want to hear praise, I can look for people who will only give it or find ways to only get it. I can avoid trying if I think I’ll fail, or I can start cheating to ensure success. In the short-term I might feel better, but over time, I’ll be progressively worse off.

We need more expansive conversations – more discomfort which, through exposure, will expand our comfort zones and increase our resilience. Silcox talks about how we need fewer “gatekeepers” – those who close doors and shut down important conversations – and more “locksmiths” – those who open them.

We can start by considering the way we speak, and think, and act. Are we using words that make others more cautious, risk averse, fearful, fragile, than they need to be? What about when talking to ourselves? Are we so focussed on staying safe from risk, that we forget about how many risks are safe to take? With this in mind, we can resolve to sit with discomfort, to recognise the doors that it can open, that comfort can’t. We can welcome feedback, even ask for it; embrace challenges, even set them for ourselves; replace complete avoidance, with strategic exposure. And if we’re in positions of authority, we can give those we oversee genuine permission to try and fail and try again.

It’s natural to avoid discomfort. But if we continually avoid what’s hard, it will feel harder still. If we want to talk about what matters and do it well; exercise moral courage; make a difference in the world – we’ll have to expand our comfort zones, not narrow them. We’ll have to take some risks. But do you know what else is risky? Sitting still.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Rethinking the way we give

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Tim Dean 19 DEC 2024

I love going home to see my family for Christmas. But over the past year I’ve noticed my uncle posting on Facebook about politics and conspiracy theories that are completely different to what I believe. I’m worried he might make an offensive quip about the news over dinner. How do I defend my point of view without it erupting into an argument?

Unlike most of the year, where we can comfortably reside within our own social bubbles, Christmas is when we’re thrust into the midst of that diverse range of personalities, generations and political persuasions that make up our extended family. This means we’re often faced with views we don’t normally encounter, and sometimes forced to defend our own views in the face of staunch opposition.

So, if you’re dreading the prospect of a stormy argument at the holiday dinner table, here are some tips for navigating the perilous territory of contentious topics and steering the conversation towards calmer waters.

Why conversations go bad

If humans were truth-seeking robots, then we’d welcome criticism of our views and thank others for showing that our beliefs are in error. But we’re not robots. We’re vulnerable social creatures, absorbing ideas and norms from our peers and those we admire, all while defending our identity and status from perceived attacks.

Compounding the complexity of how we form our beliefs and attitudes is that emotion often leads the way, with reason lagging behind, and we scramble to find arguments to support the way we feel. This means that many of the arguments we offer to support our views are actually not the cause of our belief, but the effect. They’re post-hoc rationalisations that we use to defend our underlying attitudes.

You can tell when someone is arguing using a post-hoc rationalisation, because if you surgically dismantle it, showing that it’s false, they still don’t change their mind. You might have knocked down one post-hoc rationalisation, but you haven’t challenged the actual reason they hold their attitude.

All this messy business of not being a robot means that disagreement about an issue where we hold strong feelings – and ethical questions are often the things we feel the most strongly about – can easily slip into conflict, where we rapidly find ourselves defending our turf and fighting back against threats to our identity and desperately trying to change the other person’s mind.

How to not spoil the dinner table conversation

The good news is that there are some techniques you can use to lower the temperature in contentious conversations, and possibly even walk away with a stronger relationship and some new perspectives to consider.

The first step is to stop trying to win! If you think about it, it’s strange that we even think that we can change someone’s mind in a single heated conversation. When was the last time such a conversation changed your mind? Instead, it takes a different kind of conversation – often multiple conversations – to encourage someone to adopt a different perspective, especially around topics where they already hold strong views.

So, when you hear someone state a view that you believe is wrong, try to resist doing the natural human thing of stating an opposite view. Doing so immediately locks the conversation in the Thunderdome, where two viewpoints enter, and only can survive. It’s even worse if the views battling it out are post-hoc rationalisations, because then you’re both just whiffing at ghosts.

Instead, pause. Take a deep breath. Then ask a question. And really listen to the answer. This does two important things. The first is that it actually gives you a fighting chance of understanding the detail of the other person’s view. We usually only get a chance to express a fragment of our full beliefs on a topic. And often others will fill in bit we leave unsaid with an uncharitable interpretation, sometimes even outright misrepresenting what we believe. Asking and listening allows them to fill in those gaps themselves.

The second thing that asking and listening does is arguably more important: it signals respect. Listening to someone is like giving them a gift (possibly an even more valuable one than they got out of the Secret Santa). It shows you actually care about what they think and that you want to know more. Sometimes, all people want is to get something off their chest, and giving them a chance to do so will cause them to temper their beliefs in the process, landing somewhere more reasonable.

The respect that listening generates becomes the bedrock of a good conversation about a contentious issue. It means they are more likely to want to listen to you in return, and it reduces the perception that their identity is under attack, so they might even be more willing to take your perspectives on board.

Story time

Once you’ve had a chance to listen to what they have to say (and hopefully had the chance to be listened to in return), then a next step can be to tell some stories that can shed light on your point of view.

You can talk about how you formed your belief, or share a perspective that you found surprising but persuasive. You can even invite them to share a story about how they came to their view, or ask if they know someone who has been affected by the issue you’re discussing. Techniques like this have been shown to humanise what can be otherwise abstract or dehumanised perspectives, grounding them in the real world and shifting the conversation away from stereotypes and glib generalisations.

If the conversation is getting heated at any point, there’s no shame in backing out or changing the subject. This is supposed to be a harmonious family gathering, after all. And relationships are fundamentally important to a good life, so it can sometimes be more important to preserve a relationship than it is to be right. Plus, reinforcing that relationship is precisely what is needed if you ever want to continue the conversation down the track and have them be receptive to your point of view.

Christmas dinner is not about changing minds. It’s about coming together as a family or a community to engage in ritual activities that are supposed to bring us together. At least, that’s the ideal. For many people, Christmas can be laced with tension, simmering resentments, power plays and drunken debates. While the techniques here won’t solve all those problems, they might help to lower the temperature, build some stronger relationships, and hopefully allow you to enjoy your post-meal nap in some peace.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How much should politics influence my dating decisions?

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY William Salkeld 16 DEC 2024

“If there are no dogs in heaven, I want to go where they go”, said the American performer, Will Rogers.

It is no secret that we are deeply connected to the animals we keep as pets. In Australia, most pet owners would like to think they treat their animals well. 52% of Australians consider their pets to be family members, and in 2021 Australians spent $30.7 billion on food, healthcare, and enrichment for their cats and dogs.

Studying animal ethics, I used to believe that pet ownership was a good thing. Following the arguments of moral philosopher Christine Korsgaard and many others, I saw it as a mutually beneficial situation. We provide our animals with the necessary conditions for a good life, such as food, shelter, healthcare, love and attention. In return, they provide us with companionship and countless other life-affirming benefits.

As long as we can provide our pets with the kind of life that is good for them, then having pets is a good thing, I reasoned. After all, how could I deny that my family’s Golden Retriever, Ruby, lived a charmed life full of play, food, and affection? As I would soon find out, the ethics of pet-keeping is far more complicated than ensuring our furry friends are ‘well taken care of’.

My view about pets was turned upside down after listening to a podcast with legal scholar and animal ethicist Gary Francione. Francione is an abolitionist, meaning that he believes that we should abolish all use and ownership of nonhuman animals, including pets. To understand this view, it is first important to understand the history of domesticated animals and pets.

Domesticated animals are those animals like dogs, cats, or sheep who have adapted or ‘tamed’ because of or by humans. While the jury is still out on how wolves initially interacted with humans to become dogs, humans have subsequently spent millennia forcibly breeding dogs to make them less aggressive, ‘cuter’, or specialised in some activity like cattle herding. Or, in the case of my family’s Golden Retriever, Ruby, it seems she has been bred to chew up sofas and love carrots (don’t ask).

As Francione puts it, we have domesticated dogs and cats into a state of perpetual childhood where they are dependent on us for basic care. Yet, unlike children, cats and dogs don’t grow up and become independent; they remain in a state of dependency for their entire lives.

The animals we keep as pets are a subset of domesticated animals. The concept of pet ownership in Western countries is surprisingly recent, beginning in the Victorian era. Our entitlement to owning pets has not existed throughout history, meaning we should be critical of current ethical attitudes towards pets.

For abolitionists like Francione, the problem of pet ownership is twofold. One, the state of dependency is problematic because we have bred animals to become dependent on us. Imagine if someone raised their child to be completely dependent on them and to never reach true adulthood; we would likely call it emotional abuse. Yet in the case of pets, it is considered ‘proper training’.

Second is the problem of ownership and possession. Animals (including pets) are treated as property in the law. It’s even in the name: ‘pet ownership’. Most of us know that animals are sentient, and perhaps even that they are individuals with rights. However, if this was truly the case, then it would be nonsensical that an animal could be ‘owned’ as property in the same way it is morally outrageous for a human to be owned.

For these two reasons, abolitionists like Francione think that if we could wave a magic wand, we should remove all domesticated animals like cats and dogs who depend on us from existence. While we should adopt and care for the current animals that are already alive, we should also aim to abolish the institution of owning pets.

The abolitionist position is confronting and uncomfortable. I love my dog Ruby, and I was initially defensive against Francione’s argument. Has my family really been doing something wrong by pouring hours of our lives and thousands of our (my parents’) dollars into caring for a dog who we treat as a member of a family? Even if we have not personally been doing anything wrong, the world without cats and dogs that Francione envisages seems like a slightly less happy world.

I was struggling with this dilemma when my partner and I met a cat at a guesthouse in Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands, curled up in a box in the corner of the reception. When we asked the guesthouse owners what his name was, they said that he didn’t have a name yet because he only arrived three weeks earlier.

He, the cat, had picked them. In return for his company, the guesthouse owners gave him as much kibble as he would like and took him to the vet. On the same trip, I also learned that in Türkiye, many people have a ‘tab’ at the vet they use for vagabond cats who choose to live with them. This framework of domesticated animals without ‘owners’ is what I call the ‘free roaming’ model, an idea tentatively welcomed by animal studies scholar Claudia Hirtenfelder that, as Eva Meijer argues, acknowledges the agency of nonhuman animals.

Perhaps a more familiar example of a free-roaming animal is the life of the eponymous dog from the beloved Australian film, Red Dog. In the film, Red Dog is no one’s pet. Rather, he is cared for by the employees of a mine in Western Australia’s Pilbara and eventually decides to live with an American man named John Grant. Red Dog has agency, and [spoiler alert] uses that agency to travel across Australia in search of John after his premature death.

The key difference between free-roaming domesticated animals and pets is that these animals are not owned. Yes, many free-roaming cats and dogs may still depend on some human care, but they have a choice in how and from whom they receive that care.

The free-roaming model is not perfect, however. According to the Humane Society, 25% of outdoor (commonly referred to as ‘feral’) kittens do not survive past 6 months. This is not the case for kittens bred in captivity. And while some cats are lucky, like the one we met in Malaysia, many endure lives of illness and famine. And, as Korsgaard points out, domesticated cats are a predatorial threat to native wildlife, which is why, for example, they are not allowed outside without a leash in the Australian Capital Territory.

For the free-roaming model of animal companionship to work, we would have to make our urban spaces more hospitable to other animals. There would have to be a significant attitude shift in our tolerance of animals in public spaces where we usually don’t see them.

Until that day, perhaps the best thing we can do is adopt pets from shelters like the RSPCA, rather than breeders who perpetuate the institution of animal dependency and pet ownership. However, the free-roaming model gives hope for a post-pet world. As Korsgaard puts it:

“There is something about the naked, unfiltered joy that animals take in little things—a food treat, an uninhibited romp, a patch of sunlight, a belly rub from a friendly human—that reawakens our sense of the all-important thing that we share with them: the sheer joy and terror of conscious existence.”

This article won the 2024 Young Writers’ Competition 18-29 category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The right to connect

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Does ‘The Traitors’ prove we’re all secretly selfish, evil people?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture