Are there limits to forgiveness?

There is a moment of gut-wrenching horror in Simon Wiesenthal’s The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.

It begins with Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, at the bedside of a fatally wounded German soldier.

“I am resigned to dying soon,” the soldier said to him. “But before that I want to talk about an experience which is torturing me. Otherwise, I cannot die in peace.” Comforted by Wiesenthal’s attention, the soldier began to confess to his role in a barbaric war crime where around two hundred Jewish men, women, and children were marched into a house and burned alive.

“I must tell you of this horrible deed,” cried the soldier. “Tell you because – you are a Jew.”

The soldier begs for the forgiveness that would grant him a peaceful death. His voice quivered, his hand trembled; his exhaustion and remorse were palpable. But Wiesenthal said nothing. He turned and left the soldier without a word.

A day later, he found out the soldier had died, unforgiven.

Perversely cruel as it might seem, the moment haunts Wiesenthal. Was it wrong to withhold forgiveness to the soldier, given he seemed genuinely repentant?

The Sunflower poses an invitation. “Ask yourself a crucial question, ‘what would I have done?’”, Wiestenthal dares the reader.

Wiesenthal tasks philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and genocide survivors with answering the very same question and features their responses throughout the book.

It’s true that many of us will not find ourselves in such a harrowing situation. But some will. Victims of crime can be invited to participate in restorative justice programs where they face the person who has wronged them. One in five Australian women above fifteen years old have been sexually assaulted or threatened – usually by someone they know.

In these cases, a victim may face an ethical dilemma they haven’t chosen. One that feels cruel to subject them to: they must decide whether to grant or withhold forgiveness.

Earning forgiveness

Should we forgive those who have wronged us? What makes someone worthy of forgiveness? Can forgiveness be wrong?

These questions are important for two reasons. First, forgiveness doesn’t always come naturally. At the moment when we’ve been wronged – often severely and traumatically – it’s doubly difficult to meditate on the ethics of forgiveness.

It’s painful, confusing and morally loaded: after all, who wants to be the person who doesn’t forgive when people who do – even when it seems impossible – is held up as a paragon of virtue and humanity?

But second, we need to understand how forgiveness should work because we’re all going to seek forgiveness at some point. We will all wrong someone else at some stage, in big ways or small. If we’ve done some work thinking about how we want to forgive, we’ve got a roadmap to follow when we’re the ones seeking forgiveness.

In Wiesenthal’s case, the genuine remorse shown by the German soldier is what troubles him. He believes the soldier is truly sorry for what he did. Not everyone agrees – was this man remorseful, or was he just scared to die? But whether or not the soldier was remorseful, we tend to agree that remorse matters for forgiveness. If someone is remorseful, we can at least think about forgiving them. If there’s no remorse, it doesn’t seem like a moral challenge to withhold forgiveness.

Genuine remorse

But expressing remorse is hard. It takes more than the non-pologies theologian L. Gregory Jones calls “spinning sorrow”. It involves acknowledging responsibility and wrongdoing. “I’m sorry you were offended” isn’t remorse. It’s performative, and puts the onus on the victim for their own suffering. In short, it says you were offended; I didn’t do anything offensive. Your suffering is on you. That’s not remorse, that’s pig-headedness.

Remorse demands us to understand the full extent of our wrongdoing.

That it was wrong, why it was wrong, and how that wrongdoing has harmed someone else. Which gives us good reason to think that Wiesthenthal’s soldier is not genuinely remorseful.

The horror of the Holocaust depended on the systematic denial of Jewish personhood. They weren’t seen as individuals – people with lives complex, unique, and infinitely valuable. Instead, they were objects to be treated as others saw fit.

By treating Wiesenthal as ‘a Jew’ – a generic placeholder for the actual people the solider murdered – the German soldier is continuing on with the same abhorrent thinking that led to his crimes in the first place. He doesn’t understand the depth of what he did. How can he then apologise in a way that warrants forgiveness?

The politics of forgiveness

To step away from Wiesenthal’s case for a second, how often do we witness apologies that fail to show any awareness of the source of the wrongdoing? On a political level, we see apologies offered by those who continue to benefit from those injustices. Does this constitute remorse, or a genuine understanding of the wrongdoing?

Take political apologies, for instance: some naysayers to Australia’s National Apology to the Stolen Generations argued that the people apologising weren’t the ones who had done anything wrong. The claim here is if we haven’t done anything wrong, we don’t need to be forgiven; and if we don’t need to be forgiven, why would we apologise?

This perhaps misses an important consideration.

If we continue to benefit from a past wrong and fail to address the source of the continued disadvantage, there is a sense in which we’ve prolonged the wrongdoing.

However, it also calls our attention to the role of status in forgiveness. I cannot offer an apology for a wrong I haven’t been involved in.

Equally, I cannot forgive unless I have been wronged, which also complicates the politics of forgiveness: who has the moral authority to forgive? Could Wiesthenthal, who was treated as a ‘generic Jew’ by the soldier, actually forgive – even if he wanted to? After all, the soldier’s crimes did not directly harm him.

Eva Kor was a Holocaust survivor who offered forgiveness to Josef Mengele, doctor of the notorious ‘twin experiments’ in Auschwitz. Her actions brought criticism from other survivors, who said Kor wasn’t entitled to offer forgiveness on behalf of others. Nor should she pressure them to forgive when they were not ready.

Jona Laks, another ‘Mengele twin’, refused to forgive. In Mengele’s case, this is understandable. But what if there was genuine remorse, a commitment to change, and steps to address the wrongdoing? Would it be wrong to refuse forgiveness?

On some occasions, it seems so. For instance, we consider pettiness – when someone is unable to move past very slight or non-existent wrongs – as a vice, or a mark of bad character. I’m not suggesting a Holocaust survivor (or any Jewish person) who refused to forgive the Nazis under any condition was being petty, but this takes us back to the question posed earlier.

Is there anything that’s unforgiveable?

This brings us to the final question: are there some things which are unforgiveable? How should we think about them?

Maybe. Philosopher, Hannah Arendt believed that unforgiveable crimes were those where no punishment could be given that would be proportionate to the crime itself. Where no atonement is possible, no forgiveness is possible. For Arendt, these crimes are an evil beyond redemption.

In contrast, French philosopher Jacques Derrida argued that conditional forgiveness is in fact, not forgiveness. By withholding forgiveness until considerations (like remorse) are met, Derrida believed that we are forgiving someone who is already innocent – that is, someone who no longer needs forgiveness. Only the unremorseful person remains guilty, and only the unremorseful person actually needs forgiveness.

As a result, Derrida concludes with a paradox: only the unforgiveable can be truly forgiven.

Derrida traces his thinking back to religious traditions where forgiveness is unconditional and uneconomic. It is a gift, not a transaction. This is a view L. Gregory Jones believes is centrally important to avoid “weaponising forgiveness”.

I think it’s important to remember that forgiveness should always be a gift and not an expectation. It’s unfair to expect any person who has been victimized, especially if it’s raw, to be ready to forgive.

And — this is particularly important in domestic violence and other kinds of forgiveness — the expectation of forgiveness is also used as a weapon to punish and perpetuate a cycle. It’s often the case in domestic violence, for example, where the abuser will come and say, “you need to forgive me because you’re a Christian” and the person feels obligated to do that. All that does is perpetuate and intensify the violence rather than remedy it.

So how should we think about Wiesenthal’s case? What would we do? It seems quite evident that he had no duty to forgive this Nazi – and that perhaps he had no right to do so. However, if we set aside the question of legitimacy, how might he make this decision?

Some philosophers have argued that self-respect is central to the way we think about forgiveness. Forgiveness involves a recognition that we have value – that we did not deserve to be wronged, and the other person should not have wronged us.

By forgiving, we assert our status in the moral community – our dignity.

However, others might believe such forgiveness reduces their self-worth – especially if this forgiveness leaves the wrongdoer better off than the victim. Forgiveness can grant peace to wrongdoers – as the German soldier knew – but often leaves the victim alone in their trauma.

Author Susan Cheever once wrote that “Being resentful is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die”. For some, this may be true. For others, forgiving might be like giving someone a drink while you are dying of thirst.

Should Wiesenthal have forgiven the soldier? It might all depend on what he could swallow and still look at himself in the mirror.

It may all come down to what he wanted to see when he looked in the mirror.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

From capitalism to communism, explained

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

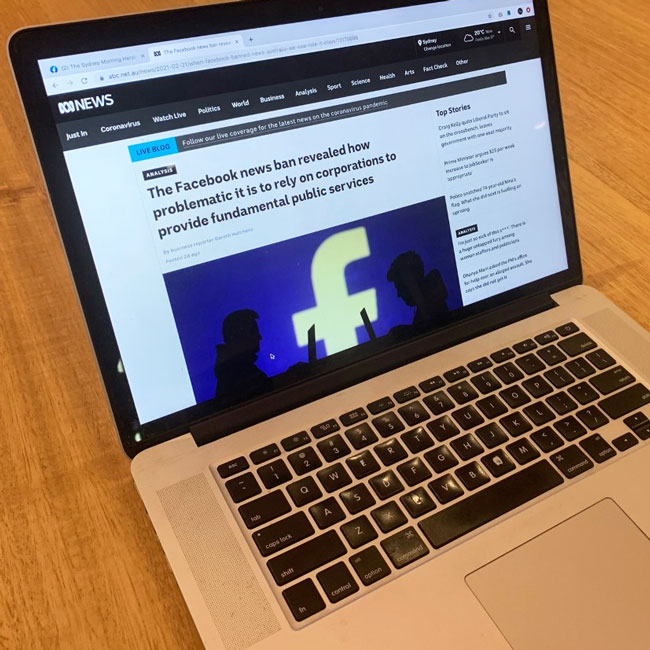

Who's to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 25 FEB 2021

News will soon return to Facebook, with the social media giant coming to an agreement with the Australian government. The deal means Facebook won’t be immediately subject to the News Media Bargaining Code, so long as it can strike enough private deals with media companies.

Facebook now has two months to mediate before the government gets involved in arbitration. Most notably, Facebook have held onto their right to strip news from the platform to avoid being forced into a negotiation.

Within a few days, your feed will return to normal, though media companies will soon be getting a better share of the profits. It would be easy to put this whole episode behind us, but there are some things that are worth dwelling on – especially if you don’t work in the media, or at a social platform but are, like most of us, a regular citizen and consumer of news. Because when we look closely at how this whole scenario came about, it’s because we’ve largely been forgotten in the process.

Announcing Facebook’s sudden ban on Australian news content last week, William Easton, Managing Director of Facebook Australia & New Zealand wrote a blog post outlining the companies’ reasons. Whilst he made a number of arguments (and you should read them for yourself), one of the stronger claims he makes is that Facebook, unlike Google Search, does not show any content that the publishers did not voluntarily put there. He writes:

“We understand many will ask why the platforms may respond differently. The answer is because our platforms have fundamentally different relationships with news. Google Search is inextricably intertwined with news and publishers do not voluntarily provide their content. On the other hand, publishers willingly choose to post news on Facebook, as it allows them to sell more subscriptions, grow their audiences and increase advertising revenue.”

The crux of the argument is this. Simply by existing online, a news story can be surfaced by Google Search. And when it is surfaced, a whole bunch of Google tools – previews, summaries from Google Home, one-line snippets and headlines – give you a watered-down version of the news article you search for. They give you the bare minimum info in an often-helpful way, but that means you never click the site or read the story, which means no advertising revenue or way of knowing the article was actually read.

But Facebook is different – at least, according to Facebook. Unless news media upload their stories to Facebook, which they do by choice, users won’t see news content on Facebook. And for this reason, treating Facebook and Google as analogous seems unfair.

Now, Facebook’s claims aren’t strictly true – until last week, we could see headlines, a preview of the article and an image from a news story posted on Facebook regardless of who posted it there. And that headline, image and snippet are free content for Facebook. That’s more or less the same as what Facebook says Google do: repurposing news content that can be viewed without ever having to leave the platform.

However, these link previews are nowhere near as comprehensive as what Google Search does to serve up their own version of news stories for the company’s own purpose and profit. Most of the news content you see on Facebook is there because it was uploaded there by media companies – who often design video or visual content explicitly to be uploaded to Facebook and to reach their audience.

However, on a deeper level, there seem to be more similarities between Google and Facebook than the latter wants to admit, because the size and audience base Facebook possesses makes it more-or-less essential for media organisations to have a presence there. In a sense, the decision to have a strategy on Facebook is ‘voluntary’, but it’s voluntary in the same way that it’s voluntary for people to own an attention-guzzling, data sucking smartphone. We might not like living with it, but we can’t afford to live without it. Like inviting your boss to your wedding, it’s voluntary, but only because the other options are worse.

Facebook would likely claim innocence of this. Can they really be blamed for having such an engaging, effective platform? If news publishers feel obligated to use Facebook or fall behind their competitors that’s not something Facebook should feel bad about or be punished for. If, as Facebook argue, publishers use them because they get huge value from doing so, it does seem genuinely voluntary – desirable, even.

Even if this is true, there are two complications here. First, if news media are seriously reliant on Facebook, it’s because Facebook deliberately cultivated that. For example, five years ago Facebook was a leading voice behind the ‘pivot to video’, where publishers started to invest heavily in developing video content. Many news outlets drastically reduced writing staff and investment in the written word, instead focussing on visual content.

Three years later, we learned that Facebook had totally overstated the value of video – the pivot to video, which served Facebook’s interests, was based on a self-serving deception. This isn’t the stuff of voluntary, consensual relationships.

Let’s give Facebook a little benefit of the doubt though. Let’s say they didn’t deliberately cultivate the media’s reliance on their platform. Still, it doesn’t follow obviously from this that they have no responsibility to the media for that reliance. Responsibility doesn’t always come with a sign-up sheet, as technology companies should know all too well.

French theorist Paul Virilio wrote that “When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution.” Whilst Virilio had in mind technology’s dualistic nature, modern work in the ethics of technology invites us to interpret this another way.

If inventing a ship also invents shipwrecks, it might be up to you to find ways to stop people from drowning.

Technology companies – Facebook included – have wrung many a hand talking about the ‘unintended consequences’ of their design and accepting responsibility for them. In fact, speaking before a US Congress Committee, Mark Zuckerberg himself conceded as much, saying:

“It’s clear now that we didn’t do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm, as well. And that goes for fake news, for foreign interference in elections, and hate speech, as well as developers and data privacy. We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake. And it was my mistake. And I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I’m responsible for what happens here.”

It seems unclear why Facebook recognised their responsibility in one case, but seem to be denying it in another. Perhaps the news media are not reliant – or used by – Facebook in the same way as they are Google, but it’s not clear this goes far enough to free Facebook of responsibility.

At the same time, we should not go too far the other way, denying the news media any role in the current situation. The emergence of Facebook as a lucrative platform seems to have led the media to a Faustian pact – selling their soul for clicks, profit and longevity. In 2021 it seems tired to talk about how the media’s approach to news – demanding virality, speed, shareability – are a direct result of their reliance on platforms like Facebook.

The fourth estate – whose work relies on them serving the public interest – adopted a technological platform and in so doing, adopted its values as their own: values that served their own interests and those of Facebook rather than ours. For the media to now lament Facebook’s decision as anti-democratic denies the media’s own blameworthiness for what we’re witnessing.

But the big reveal is this: we can sketch out all the reasons why Facebook or the media might have the more reasonable claim here, or why they share responsibility for what went down, but in doing so, we miss the point. This shouldn’t be thought of as a beef between two industries, each of whom has good reasons to defend their patch.

What needs to be defended is us: the community whose functioning and flourishing depends on these groups figuring themselves out.

Facebook, like the other tech giants, have an extraordinary level of power and influence. So too do the media. Typically, we don’t to allow institutions to hold that kind of power without expecting something in return: a contribution to the common good. This understanding – that powerful institutions hold their power with the permission of a community they deliver value to – is known as a social license.

Unfortunately, Facebook have managed to accrue their power without needing a social license. All power, no permission.

This is in contrast to the news media, whose powers aren’t just determined by their users and market share, but by the special role we afford them in our democracy, the trust and status we afford their work isn’t a freebie: it needs to be earned. And the way it’s earned is by using that power in the interests of the community – ensuring we’re well-informed and able to make the decisions citizens need to make.

The media – now in a position to bargain with Facebook – have a choice to make. They can choose to negotiate in ways that make the most business sense for them, or they can choose to think about what arrangements will best serve the democracy that they, as the ‘fourth estate’, are meant to defend. However, at the very least they know that the latter is expected of them – even if the track record of many news publishers gives us reason to doubt.

Unfortunately, they’re negotiating with a company whose only logic is that of a private company. Facebook have enormous power, but unlike the media, they don’t have analogous mechanisms – formal or informal – to ensure they serve the community. And it’s not clear they need it to survive. Their product is ubiquitous, potentially addictive and – at least on the surface – free. They don’t need to be trusted because what they’re selling is so desirable.

This generates an ethical asymmetry. Facebook seem to have a different set of rules to the media. Imagine, for a moment, if the media chose to stop reporting for a fortnight to protest a new law. The rightful outrage we would feel as a community would be palpable. It would be nearly unforgivable. And yet we do not hold Facebook to the same standards. And yet, perhaps at this point, they’ve made themselves almost as influential.

There’s a lot that needs to happen to steady the ship – and one of the most frustrating things about it is that as individuals, there isn’t a lot we can do. But what we can do is use the actual license we have with Facebook in place of a social license.

If we don’t like the way a news organisation conducts themselves, we cancel our subscriptions; we change the channel. If you want to help hold technology companies to account, you need to let your account to the talking. Denying your data is the best weapon you’ve got. It might be time to think about using it – and if not, under what circumstances you might.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

![]()

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lies corrupt democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 21 JAN 2021

If your kids are anything like mine, the holidays have officially hit the ‘we’ve dragged on too long’ stage.

Your children drift like bored zombies from room to room, looking for another screen or toy to give them a fresh dopamine hit.

They don’t want to admit it, but they’re ready for school to go back. You’re all hanging out for that first day.

Good news! You can stop waiting. You don’t need to let the boredom drag on until school goes back. You can get your child’s – and your own – synapses firing right now and sharpen your ethical sensibilities in the process, thanks to a new season of Short & Curly, the award-winning, chart-topping ethics podcast produced by the ABC, and featuring Ethics Centre fellow Matt Beard (that’s me).

The podcast, now in its 13th season, is a playful, light-hearted and engaging exploration of ethics. It’s driven by the central belief that ethics is a team sport, and each twenty-minute episode features a number of ‘thinking questions’ where listeners are encouraged to pause the show to talk about some big ideas with the people around them. This isn’t just a podcast for your kids – it’s one for you as well!

The latest season comprises of five episodes on a wide range of topics and settings, including:

- A class being held back by an angry teacher hell-bent on finding out who stole her cookies, prompting us to ask: is collective punishment is ever justified?

- An impromptu beach trip is cancelled thanks to a fear of sharks – should we cull sharks to make sure that swimmers can enjoy the ocean free of fear?

- Frozen and The Avengers turn a casual trivia night into a discussion of one of the oldest questions in ethics: do the ends ever justify the means?

- As the Amazon – the lungs of the world – continues to burn, putting all of us an increased threat to climate change, we go on a tour of the Amazon and ask who owns the rainforest, and who should decide how to treat it?

- We take a tour of the wonderful world of robots! Looking at the various ways that robots could replace humans in the future, and ask whether or not they should.

One of the pitfalls of parenting is making ‘doing the right thing’ seem like the opponent of fun. If our kids see ethics as more closely connected to discipline than it is to curiosity, we risk setting them up for a mode of thinking that doesn’t serve them or the world they’ll help build.

Whether or not you’re tuning into the podcast, try to make imagination, creativity and curiosity your default settings when discussing ethics with your kids. Do your best not to close off discussion by giving your ‘authoritative’ view. Discussions don’t work well under hierarchies. And if you need some more pointers, check out our handy guide to talking to kids about ethics here.

Oh, and there may be some extremely bad rapping in one of the episodes. I won’t tell you which one, but be on the lookout!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 15 DEC 2020

Imagine if every school in Australia introduced comprehensive surveillance technology coupled with facial recognition, and was able to assign a score to each student based on how good a “school citizen” they were.

Students could access an app that provided them with feedback on things they’d done, or failed to do, throughout the day. The day-to-day data could then be collected and a general character assessment made of the child on, let’s say, a year-by-year basis. At the end of the year, maybe at presentation night, students would be told if they’d been “good” school citizens or not.

I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest most people would find this idea pretty repugnant. Many would see echoes of China’s oppressive social credit system. Words like “Orwellian” would be thrown around with reckless abandon.

Just don’t tell that to the families around the world for whom Christmas involves a character check from Santa Claus. Certainly don’t tell the 11 million-odd who have “adopted’” an Elf on the Shelf and will have dusted it off for the season.

If you haven’t heard of it, the Elf on the Shelf explains how Santa is able to see you when you’re sleeping and know when you’re awake. Manufactured by Creatively Classic Activities and Books, the Elf on the Shelf is a tool used by families to add some more wonder and fun to the Christmas season.

Parents move the elf around, and kids look to see where it will appear next. They’re often also told that because they don’t know where the elf is or what the elf is watching, they’d better make sure they’re behaving themselves. After all, the elf’s job is to report back to Santa.

That’s right. Santa has an army of tiny, surprisingly mobile little snitches embedded in every home, watching, collecting data, feeding it back to the big guy. For some families, the elf also leaves handy notes for the kids, to make sure they stay on St Nick’s good side. “I don’t like it when you don’t share your toys. I don’t want to have to tell Santa about this behaviour,” reads one note a parent shared online.

Social credit be damned. Santa had it figured out this whole time!

We tend to be more sceptical of surveillance when it comes to our kids. For instance, recent trials of facial recognition in Victorian schools have been met with human rights concerns and academic criticism. When Mattel developed Aristotle, a digital assistant to be given to newborn children who would grow and develop alongside them, it was pulled from the market for privacy concerns. Even tools like GPS tracking apps are the subject of general debate and controversy.

There are good reasons for these concerns. Law professor Julie E Cohen argues that “privacy fosters self-determination” and that it is “shorthand for breathing room to engage in the processes of boundary management that enable and constitute self-development”.

So, not only does the collection of children’s data put them at risk if that data falls into the wrong hands, there’s a stifling effect on children’s development when they feel like they’re continually being watched.

But the Elf on the Shelf isn’t quite analogous to China’s mass surveillance. For one thing, Santa only has about 11 million elves out there, which is amateur hour compared to China’s “Skynet” of over 200m cameras. For another, the Elf on the Shelf doesn’t use fear and promises of safety to gain people’s comfort with surveillance and data gathering; it uses fun.

Less like a social credit system, more Facebook. Esteemed company indeed.

Of course, Elf on the Shelf isn’t actually surveillance because – spoiler alert – it’s based on a myth. I’ve no doubt plenty of parents will dismiss what I’m saying here as unnecessary scaremongering over something that’s actually fine, fun and basically a bit of stupid play at Christmas time.

While this wouldn’t be the first time a philosopher has been accused of sucking the fun out of a situation, I’m not sure that argument cuts it.

First, the rise of “sharenting” and the pushback from children against parents who post too much information about them online indicates parents are not always the best custodians of their kids’ privacy. In general, a generation prone to oversharing on social media may not be the best judges of what lessons Elf on the Shelf is teaching.

Second, and more importantly, the effects of surveillance work even if the surveillance isn’t really happening. This was the genius of the infamous Panopticon – a prison designed by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, where a guard tower could potentially observe any prisoner at any given time, but no prisoner could see the guard tower. It was always possible that you were being observed, which meant you behaved as though you were being observed at all times.

This logic is, of course, very creepy. It’s also very common – as another philosopher, Michel Foucault, later pointed out. You can build workplaces, schools, mental health institutions and yes, nationwide mass surveillance networks on similar principles. The concept is that the possibility of observation and judgement means there’s no need to force people to conform – they do it themselves. Arguably, China’s social credit system is the high-water mark of the logic of the Panopticon.

But the rhetoric – intentional or not – behind Elf on the Shelf has echoes of the Panopticon. It reads from the same playbook. The elf appears at random times and in random locations. It’s always possibly watching.

Whether that’s the goal parents are trying to achieve or not, we ought to be concerned about the effects of introducing and normalising this kind of behaviour monitoring and observation to kids.

As Olly Thorn, the philosopher behind Philosophy Tube tweeted: “He sees you when you’re sleeping He knows, when you’re awake, It’s a subtle, calculated technology of subjection.”

This isn’t necessarily a reason to ditch the tradition, but we can do away with the creepiness – especially as the myth becomes more and more like reality. It’s entirely possible to have an Elf on the Shelf and not play this game. Maybe the elf is just waiting for Santa to come and deliver the presents – and helps him unload the gifts. Perhaps you don’t use the elf as a tool for discipline but as a game and a story that’s played together.

Maybe you don’t need to tell the Santa story at all, but that’s another matter.

This article was first published in The Guardian Australia on 16 December, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

If you’ve ever helped a child to master toileting, you’ll know of the moment where your patience and understanding expires.

It’s somewhere between the sixth wet bed and the poo stains on the walls, where you beg, implore the child to explain. “You know how to use the toilet, why don’t you just do it?!”

Well, park that frustration friend, because if the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle is to be believed, we’re all a bit like that child, smearing shit on the walls despite knowing better. Aristotle believed in something he called akrasia – which is usually translated as ‘weakness of the will’, but I prefer to translate it as ‘incontinence’.

That’s right, Aristotle thought most of us had, at one stage or another, a leaky ethical bladder. We know what’s right and wrong; we know how we should act, and yet we wet ourselves rather than actually doing it.

This happens, according to Aristotle, for two reasons. First, passion. There are times when our emotions, ego, excitement or panic get the better of us, and our reason disappears. This can lead us to violence, cruelty, thoughtlessness or any number of things that we know are wrong. Like a toddler wetting themselves in fear or excitement, our moral restraint and discipline is overwhelmed by the emotion of the moment.

This form of akrasia often feels like being ‘swept up’ in the moment. We suddenly find our fists clenched, we find ourselves unable to swallow a hurtful thought – we are, for all intents and purposes – not in control. However, we’re responsible for our lack of control. According to most scholars who believe akrasia is a thing, we lose control because we haven’t worked hard enough to master ourselves. “I’m sorry I said that, I totally lost control,” is an explanation here – not an excuse.

The second way we can be overwhelmed is weakness. Sometimes we are the child who just doesn’t make it to the bathroom in time and has an accident on the floor. Morally, we know that we should try to minimise carbon emissions and that means we should get out of our pyjamas and walk the five minutes to pick up takeaway. But wouldn’t it be faster, and easier, to drive? Here, it’s clear what should be done. It’s just we don’t have the strength of will to do it.

Akrasia of this kind is different to the ‘heat of the moment’ stuff we discussed above. In this case, the little voice in our heads is nagging at us: ‘you should say something’, ‘you shouldn’t be doing this’, ‘that’s your son’s Easter chocolate Matt, you shouldn’t be eating it’… stuff like that. Here, we’re perfectly aware of our failing and watch ourselves fail, seemingly incapable of doing otherwise.

However, there are some who believe akrasia is actually impossible. They reject outright the idea that someone can know what is right to do and also refuse to do that thing. Here’s how their argument looks:

- Every choice people make is made because they see something good in that action.

- Therefore, nobody willingly chooses to do something bad.

- When people appear to be choosing to do something bad, it is because they think that bad thing is, in some way, good.

- Bad things happen because people are mistaken about what’s good.

The belief behind akrasia is that we can know – really know – what’s good and shit the bed when it comes to actually doing it. But would someone who really understood why we need to speak up against abuses of power ever remain silent? Critics of akrasia think not. They think the reason why someone wouldn’t speak up against a bully is because they’ve decided that in this situation, they momentarily believe that the good of personal safety trumps the good of justice. That is, the source of unethical behaviour is in mistaken beliefs, not in weak character.

However, this kind of reasoning comes close to committing the ‘No True Scotsman’ fallacy. The This fallacy, named is named for the Scottish-themed anecdote used to demonstrate it, is a kind of circular reasoning. Here’s how it looks:

- Claim: All Scots are brave and never flee battle

- Counter-evidence: But MacDougall is a Scot and he fled battle yesterday!

- Denial of evidence: MacDougall isn’t a true True Scots are brave and never flee battle.

The No True Scotsman is a way of shifting the goal posts so counterfactuals can’t actually disprove your claim. They are just reworked to support it further.

Critics of akrasia seem to make a similar claim:

- Claim: People do the wrong thing because they don’t know what’s right

- Counter-evidence: Yesterday I knew I should have returned the wallet I found with the cash still inside, but I took the cash and then returned the wallet

- Denial of evidence: You didn’t truly know that’s what you should have done. Otherwise, you would have done it.

This might seem like an academic dispute. And that’s because it is. But it’s also one that matters. Being able to identify the source of ethical failure is crucial if we’re going to prevent it. If ethical failures are problems of knowing and understanding what is good and why it’s good, then the solution is going to involve a lot of education.

If instead, ethical failures are connected to weakness of the will, then our ethics training needs to look a bit more like toilet training: getting us to identify the cues, knowing what to do ahead of time and having the strength to hold on, even when our will seems like it’s going to give way.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 25 NOV 2020

This is the moment when I’m finally going to get my Advanced Level Irony Badge. I’m going to write an opinion piece on why we shouldn’t have so many opinions.

I’ve spent the majority of this week digesting the findings from the IDGAF Afghanistan Inquiry Report. I’m still making sense of the scope and scale of what was done, the depth of the harm inflicted on the Afghan victims and their community at large and how Australian warfighters were able to commit and permit crimes of this nature to occur.

My academic expertise is in military ethics, so I’ve got an unfair advantage when it comes to getting a handle on this issue quickly, but still, I was late to the opinion party. Within an hour or so of the report’s publication, opinions abounded on social media about what had happened, why and who was to blame. This, despite the report being over five hundred pages long.

We spend a lot of time today fearing misinformation. We usually think about the kind that’s deliberate – ‘fake news’ – but the virality of opinions, often underinformed, is also damaging and unhelpful. It makes us confuse speed and certainty with clarity and understanding. And in complex cases, it isn’t helpful.

More than this, the proliferation of opinions creates pressure for us to do the same. When everyone else has a strong view on what’s happened, what does it say about us that we don’t?

We live in a time when it’s not enough to know what is happening in the world, we need to have a view on whether that thing is good or bad – and if we can’t have both, we’ll choose opinion over knowledge most times.

It’s bad for us. It makes us miserable and morally immature. It creates a culture in which we’re not encouraged to hold opinions for their value as ways of explaining the world. Instead, their job is to be exchanged – a way of identifying us as a particular kind of person: a thinker.

If you’re someone who spends a lot of time reading media, you’ve probably done this – and seen other people do this. In conversations about an issue of the day, people exchange views on the subject – but most of them aren’t their views. They are the views of someone else.

Some columnist, a Twitter account they follow, what they heard on Waleed Aly’s latest monologue on The Project. And they then trade these views like grown-up Pokémon cards, fighting battles they have no stake in, whose outcome doesn’t matter to them.

This is one of many things the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had in mind when he wrote about the problems with the mass media almost two centuries ago. Kierkegaard, borrowing the phrase “renters of opinion” from fellow philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote that journalism:

“makes people doubly ridiculous. First, by making them believe it is necessary to have an opinion – and this is perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of the matter: one of those unhappy, inoffensive citizens who could have such an easy life, and then the journalist makes him believe it is necessary to have an opinion. And then to rent them an opinion which, despite its inconsistent quality, is nevertheless put on and carried around as an article of necessity.”

What Kierkegaard spotted then is just as true today – the mass media wants us to have opinions. It wants us to be emotional, outraged, moved by what happens. Moreover, the uneasy relationship between social media platforms and media companies makes this worse.

Social media platforms also want us to have strong opinions. They want us to keep sharing content, returning to their site, following moment-by-moment for updates.

Part of the problem, of course, is that so many of these opinions are just bad. For every straight-to-camera monologue, must-read op-ed or ground-breaking 7:30 report, there is a myriad of stuff that doesn’t add anything to our understanding. Not only that, it gets in the way. It exhausts us, overwhelms us and obstructs real understanding, which takes time, information and (usually) expert analysis.

Again, Kierkegaard sees this problem unrolling in his own time. “Everyone today can write a fairly decent article about all and everything; but no one can or will bear the strenuous work of following through a single solitary thought into the most tenuous logical ramifications.”

We just don’t have the patience today to sit with an issue for long enough to resolve it. Before we’ve gotten a proper answer to one issue, the media, the public and everyone else chasing eyes, ears, hearts and minds has moved on to whatever’s next on the List of Things to Care About.

So, if you’re reading the news today and wondering what you should make of it, I release you. You don’t have to have the answers. You can be an excellent citizen and person without needing something interesting to say about everything.

If you find yourself in a conversation with your colleagues, mates or even your kids, you don’t need to have the answers. Sometimes, a good question will do more to help you both work out what you do and don’t know.

This is not an argument to stop caring about the world around us. Instead, it’s an argument to suggest that we need to rethink the way we’ve connected caring about something with having an opinion about something.

Caring about a person, or a community means entering into a relationship with them that enables them to flourish. When we look at the way our fast-paced media engages with people – reducing a woman, daughter, friend and victim of a crime to her profession, for instance – it’s not obvious this is making us care. It’s selling us a watered-down version of care that frees us of the responsibility to do anything other than feel.

Of course, this is possible. Journalistic interventions, powerful opinion-driven content and social media movements can – and have – made meaningful change in society. They have made people care.

I wonder if those moments are striking precisely because they are infrequent. By making opinions part of our social and economic capital, we’ve increased the frequency with which we’re told to have them, but alongside everything else, it might have diluted their power to do anything significant.

This article was first published on 21 August, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard 29 OCT 2020

Imagine for a moment that your neighbour is a sweet, polite elderly man.

His partner has died and he lives alone. He has no family to speak of, and one day, his lifelong habit of purchasing lottery tickets pays off. He wins $50 million.

Suddenly, your brain starts ticking over. Statistically speaking, your neighbour doesn’t have too many years left. And when he dies, he’s likely to leave behind an enormous inheritance. What if you were the person he trusted to bequeath some of his wealth to? What would you do to earn his trust with so much on the line? Would you lie? Manipulate?

It’s important for us to ponder this, because new research from The Ethics Centre suggests Australia finds itself in a similar situation. According to figures produced by Deloitte Access Economics, if Australia was able to elevate its national trust score from 54% – its current level – to 65%, it would unlock $45 billion in GDP.

With so much on the line, it would be understandable to see political leaders and businesses looking for the fastest, most effective way to build trust. We assume more trust is better than less trust. However, that’s an assumption we need to be cautious of. “I have an issue with the connection of trust with growth,’ says Rachel Botsman, Trust Fellow at Oxford University’s Said Business School and author of Who Can You Trust?

“Trust,” Botsman explains, “is not always the goal. It’s intelligently placed trust.”

Consider this from the perspective of the elderly man in our imaginary story. For him, growing more trusting of his neighbour is only a good thing if his neighbour deserves to be trusted. If he trusts a dishonest neighbour who just wants his inheritance, that growth in trust isn’t something to celebrate. In fact, this increased trust is dangerous to him.

When we take the thought experience and apply it to Australia’s economy, the point still stands. As individuals, we don’t want to be more trusting of governments, organisations or markets unless they deserve our trust. Even if higher trust levels are good for GDP, it’s only good for us if it’s earned in the right way – ethically.

“Trust is the social glue of society,” says Botsman. “To manipulate that – because it can so easily be manipulated and tracked in terms of growth – feels wrong.”

Botsman has spent years speaking to businesses and governments about trust and encouraging them to value it. Today, she’s worried lots of her audience have missed her message.

She says, “I start this conversation about trust in organisations, and then a year later it’s become a commercial strategy. They’re trying to assess the return on investment, and, it’s like ‘no, that’s not that’s not I meant! When I meant ‘value’ I didn’t mean economic growth.”

Botsman worries about the effects of framing discussions around trust in the language of business and capitalism. Trustworthy decisions “might result in some kind of short-term financial loss, so it’s problematic that loss is caught up in the language of finance and money.”

Katherine Hawley, Professor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews, and author of How to Be Trustworthy, defines trustworthy people as those who avoid unfulfilled commitments and broken promises. Basically, Hawley sees trustworthiness as the absence of untrustworthiness. Untrustworthy people make promises they can’t keep and fail to meet their obligations. If you don’t do these things, you’re probably a trustworthy person.

However, Hawley is quick to add that being trustworthy doesn’t necessarily guarantee that people will actually trust you. “There can be a significant gap between whether you are trustworthy and whether people can see you to be trustworthy,” she says.

Botsman agrees, “one of the hardest things to get your head around with trust is that even if you behave in a way that you think is the most trustworthy, you are still not in control of whether that person gives you their trust.”

This is one reason why Botsman has begun to advise organisations to stop thinking about building trust, and start thinking about acting with integrity, “because the language of intentions, motives, honesty and whether they best serve the interests of customers is much harder for companies to hide behind than questions of trust.”

A focus on integrity also helps prevent us from seeking trust in an undifferentiated way – not caring whether it’s intelligent trust or not. It shifts our focus away from what other people are thinking and toward our own activities.

“You would hope that people would want to be ethical, not just seem to be ethical,” says Hawley. However, in case that principle doesn’t persuade some people, Hawley offers a word of caution. She describes a phenomenon called ‘betrayal aversion’, “People get more angry in situations in which they first trusted and then found out that was a mistake than when they just didn’t trust in the first place.”

This idea, which comes from the work of behavioural economist Cass Sunstein, is a sober warning to those who see trust as a tool – something to be collected because it’s useful for growth, profit or advantage. “The risk for these businesses is that if people come to find out this was going on, or even find out that was their motive, then that could be worse for them.”

There is a strong moral argument – especially during a recession – for pursuing economic growth. For some, the importance of growth is likely to be enough to justify pursuing trust by any means possible. However, Hawley gives us a good reason to pause.

Chasing trust in the wrong way is something untrustworthy people do. And that makes the trust you accrue a bad investment – it’s fragile. The slower, more carefully accumulated relational trust might not offer the same returns in the short term, but it’s based on something more stable: ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Being a little bit better can make a huge difference to our mental health

Being a little bit better can make a huge difference to our mental health

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 28 OCT 2020

When Hannah first started working at her university, she was excited to work with a group of colleagues who shared her vision of contributing to the public good.

She spent a happy six years feeling like she was serving this goal. Two years later, her GP described her as having symptoms consistent with a mental breakdown.

What changed? Hannah lost her belief that her colleagues shared her commitment to the public good. She explained how “several senior individuals prioritised building relationships with senior staff or performing tasks that were very visible to senior staff, instead of performing their core duties to the community.”

One manager – working as temporary cover for a worker on maternity leave – neglected Hannah and her team, and then took credit for their work. When the maternity leave was done, this manager was promoted into an even more senior role.

Psychologists and philosophers working in various fields of trauma have noted the powerful role played by the ‘just world hypothesis’ – the belief that the world is inherently fair.

The just world belief leads us to assume that if we’re nice, we’ll be treated nicely in return, if we work as hard as someone else, we’ll be equally recognised and so forth. Unfortunately, the just world hypothesis is sometimes disproved, and the results can be psychologically disruptive.

In some cases, people will double-down on their commitment to the just world hypothesis, and conclude that if they’ve been mistreated, it must be because they’ve done something wrong. In other cases, they might conclude that the world simply isn’t fair, and can’t be relied on. In Hannah’s case, it was the latter.

“These issues were structural, existential, ethical and were psychically wounding me,” says Hannah. “I saw evidence that the quality of my work was irrelevant to my job security – it was more about who I rubbed shoulders with.”

Hannah wound up doubling her anxiety medication, taking stress leave and resigning from the university. “I still feel nauseous thinking about work, and had a panic attack last week when I accidentally opened Outlook,” she says.

Hannah’s story isn’t a one-off. It’s backed up by hard data.

The recent Ethical Advantage report commissioned by The Ethics Centre found your mental health was affected by your belief in the following three things:

- Whether or not people keep their word

- Whether or not people honestly honour their agreements

- Whether or not people will step on others to succeed

The more you agree with these statements, the better your mental (and physical) health is likely to be. But the reverse is also true.

The less able you are to trust in the people around you to act ethically, the more likely your health – both mental and physical – is to suffer.

“If I had been able to keep the perception that colleagues around me were ‘good people’ I would have been able to maintain a sort of ‘we’re all in this together’ mentality,” says Hannah. Instead, witnessing competitive, dishonest behaviour led her to lose faith in what the university stood for, and the people she worked with.

Our research has found that all it takes is 10%. If people feel like the people around them are 10% better – just a little bit – it’s enough to give their health a bump. In some cases, it’s enough to keep someone from quitting, from experiencing a mental illness or doing something they think is wrong. From little things, big changes can grow.

For Hannah, those little things are exactly those identified in the Ethical Advantage report. What would have made a difference to her would have been seeing people “doing as they say, and following through.”

“A lot of hurt has happened when senior staff have said one thing, then said a very different, contradictory thing the next week,” she says.

Perhaps the saddest aspect of Hannah’s story is how preventable it all was. She was good at her job. She’s smart and worked hard, and was driven to anxiety and burnout by an environment of competition and manipulation.

This hit especially hard for H because her workplace put a particular focus on health and wellbeing. The university “pays a lot of lip service to health and wellbeing. Senior leaders talk about it all the time, and make sure we stay ‘resilient’ and know that we’re ‘supported’,” says Hannah.

Cass R Sunstein, a legal scholar and author of Nudge, which helped champion a new wave of behavioural economics, believes that we have a deeply-held moral heuristic to punish betrayals of trust.

This means the more we believe we can trust someone, the more harshly we judge breaches of that trust.

In Hannah’s case, her faith in her colleagues, in the purpose of the institution and in the care the university promised her were all let down.

The reason why the university’s culture became so competitive was because of a change of strategic priorities. Hannah’s university put a higher focus on income than education. Hannah explained how her university had become “more profit driven, especially this year.” As a result, “an ‘every man for himself’ attitude proliferated,” she said.

Ironically, because of the mental health implications of drifting away from its true purpose, the university’s goal – better financial outcomes – becomes harder to achieve. It’s expensive to have staff experiencing burnout and mental health issues. Hannah is now on stress leave.

In 2018, KPMG estimated that every instance of mental illness in the workplace costs an organisation $3200. On its own, this may not seem like much in the context of an organisation. However, data from the Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing suggests almost 20% of the workforce experience mental health disorder. For a university of 3500 staff, that amounts to over $2 million a year in lost productivity. And that’s before we consider the more important costs – the pain and suffering of people like Hannah.

And the irony goes deeper. The competitive, ‘every person for themselves’ mentality caused Hannah to lose faith in the people around her. She no longer believed they were ethical people. Which is unfortunate, because our findings suggest people who are perceived as ethical can enjoy a bump to their wages. If you’re out for yourself, there’s a chance you’ll only be stepping on your own toes.

Of course, the reason for taking care of someone else’s mental health, treating them with respect and honouring your word isn’t because there’s something in it for you. If that’s all that’s motivating you, then something’s gone wrong. We should want to care for people at work because we care about them, period. People spend an inordinate amount of time at work – it’s a huge part of their lives – and they should be able to flourish there.

However, what this data helps us understand is just how easy it can be to turn things around for some people who aren’t living their best lives at work.

There are times when ethics can feel like an impossible burden. When the obligations thrust on us come at far too high a personal price. This isn’t one of those times. Hannah didn’t need to suffer. The university didn’t need to lose someone of her passion and talent. If only the people around her had tried a little harder to keep their word, acknowledge her work and do their jobs, she could have avoided a world of heartache. What’s more, there would have been no downside.

Hannah’s story is not unique. There’s a chance there are people like her in your workplace, your community, or even your family. So tomorrow, why not try being a little better? You don’t need to be a saint. Just 10% better.

That’s all it takes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Space: the final ethical frontier

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 24 SEP 2020

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant once famously said “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and the more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within.”

It probably didn’t occur to Kant that there would come a day when the moral law and the starry heavens would find themselves in a staring contest with one another. In fairness though, it’s been almost 250 years since he wrote that quote. Today, those starry heavens play an increasingly important role in human affairs. And wherever there are people making decisions, ethical issues are sure to follow.

To get to know this final ethical frontier, I had a chat with Dr Nikki Coleman, Senior Chaplain Ethicist with the Australian Air Force. Nikki is a bona fide space ethicist to help us get up to (hyper) speed with all the new issues around ethics in space.

Is space an environment?

One of the largest contributions of the field of environmental ethics has been to encourage people to consider the environment as having value independent of its usefulness to humans. Before environmental ethics emerged as a field, many indigenous cultures and religions had already embedded these beliefs in the way they lived and related to land.

“The idea of space is that it’s a ‘global commons’,” says Coleman. “It belongs to all of us on the planet, but also to future generations. We can’t just dump space debris. We have to be careful about how we utilise resources. Like the resources on Earth, these resources are finite. They don’t go on forever,” she says.

This echoes one of the most common arguments about preservation and sustainability. We take care of the planet not just for ourselves, but for future generations. The challenge is helping people to understand that custodianship of space means thinking about the long tail on the decisions we make now. In fact, it might be even more difficult when it comes to space because, well, space is big, and it’s a long way away and we’ll likely never go there ourselves.

“What happens in space is the same as what happens on Earth, but it’s more remote,” Coleman tells me. And yet, despite this, what happens in space affects us profoundly. Just as we rely on trees, ecosystems and other aspects of the natural environment, we are reliant on parts of space as well. “Even though these objects feel further away from us, we still have an interdependency and a relationship with space,” explains Coleman.

What role should private companies play?

We’ve seen a lot of noise about space being made by private companies like SpaceX and Virgin – which is an enormous change from the time when travelling to space was something you could only do from a national space agency in a wealthy nation. But these companies have very different motivations for expanding into space.

“Space,” says Coleman “has become a very congested space.” “The cost of space operations has dramatically decreased, and we’re now seeing whole organisations devoted to their own space operations rather than as part of a government.”

This is where some issues can arise, “because what’s appropriate for a commercial operator in returning profits to stakeholders is not necessarily what’s appropriate for the whole of the planet.” Space is a ‘global commons’, it should be used to serve everyone’s interests – including future generations – not just the needs and wants of a single company or nation. It’s unclear to what extent commercial operators are taking the idea of a global commons seriously.

“We have someone like Elon Musk putting a car into space – which is the ultimate litter – or talking about putting 42,000 satellites into low-earth orbit, which obviously creates problems around congestion and space debris,” Coleman explains, referring to Elon Musk’s proposed ‘Starlink’, a network of satellites that could dramatically improve broadband speeds.

The interstellar garbage dump

Space debris is a big deal. We probably all remember in primary school learning about how different parts of a rocket break apart as they launch into space. Some of that burns up in the atmosphere, but lots of it remains in orbit. And it’s not just a few parts of rockets and a random Tesla. There is a lot of junk floating around in orbit around earth.

“Why that is problematic is it actually stays there for a really long period of time,” Coleman explains. “Some of it will decay in orbit and burn up in the atmosphere, but a lot of it could stay there for tens of thousands of years.”

But it’s not just that the debris sticks around. It’s that it can wreck a whole lot of important stuff whilst it orbits around the planet.

Coleman tells me that debris can interfere with our current satellites. ”The International Space Station is actually quite vulnerable. It only takes a small puncture to make it a life-threatening situation. And the issue is growing because we’re putting more and more satellites – including small satellites that don’t manoeuvre – into space.”

The worst-case scenario when it comes to space debris was depicted in the recent film Gravity, where the debris destroys satellites, generating even more space debris in a cascading process called Kessler Syndrome.

“The idea of having a whole area of space that is full of space debris will actually have massive impacts for the future,” Coleman warns. We use satellites for so many things: communication, food security, navigation… it’s not just about posting on Twitter and putting photos on Facebook.”

“The precursor for space debris is lots of things in space, so that’s why it’s problematic when someone talks about putting tens of thousands of satellites into orbit.”

The militarisation of space isn’t new

Coleman is quick to point out that space and the military have a long history. In fact, Sputnik was a Russian military satellite, which means “we have had a militarisation of space operations right from the get go.”

However, there are some changes in the way that militaries are thinking about space today. “Currently, military operations in space predominantly look at satellites and communication and dedicated military satellites for example, we’re with starting to see an increase in aggressive uses of military uses of space,” says Coleman.

The challenges here are myriad, but one significant one is that so much of what’s up in space is infrastructure that both civilians and the military need. Usually, the law and ethics of war don’t permit the targeting of infrastructure used by civilians when that would be disproportionately harmful to them.

“I would argue that a civilian satellite is not a legitimate target because it could have catastrophic effects for the civilians that rely on that satellite.”

“Space debris is climate change 2.0”

Ok, yes, we already talked about space debris but it’s so interesting we have to do it twice. See, space debris isn’t just garbage; it’s property.

“If you throw a bottle into the ocean, anyone can pick that up. That means that all the plastic in the middle of the ocean can actually be collected and recycled and made into something commercially viable,” Coleman explains. “But everything that goes into space is actually the property of the country that launched it.”

This means even if someone wanted to tidy up space, they couldn’t. Anyone can litter the global commons, but that doesn’t mean anyone can tidy it up. The rubbish belongs to someone.

This is where Coleman sees the analogy to climate change beginning. No one person or group can solve the problem. “We need to work together internationally to search to solve the problem of space debris,” she says. “I’m really excited that at the moment there is a large amount of discussion internationally about climate change, but there isn’t a lot being done around [space debris].”

The other, more frightening, climate change analogy is in terms of the threat posed by space debris. “It has the capacity to have a much faster impact on life on the planet,” says Coleman. “It could push us back to the 1950s.”

If there’s life on Mars, can we live there?

It seems interesting that at a time when many societies are coming to grips with the harms and problems colonisation has had around the world, there are people seriously contemplating the colonisation of Mars. For Coleman, this reveals one of the central ethical questions – not just for space, but in any walk of life. How far do our moral obligations extend?

“Do we have a duty not just to ourselves but to others as well, and do we have a responsibility to future generations of humans or potentially future generations of whatever is growing on Mars?”

We accept that we have obligations to future humans, but it seems quite different to say that we have obligations to a microbial life form on Mars. However, Coleman poses a further question: do we also have duties to whatever that microbial organism might evolve to be in millions of years?

“If we find life, do we owe it the opportunity to grow and develop into something that might eventually turn into intelligent life?”

I, for one, welcome our new microbial brothers and sisters.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The undeserved doubt of the anti-vaxxer

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

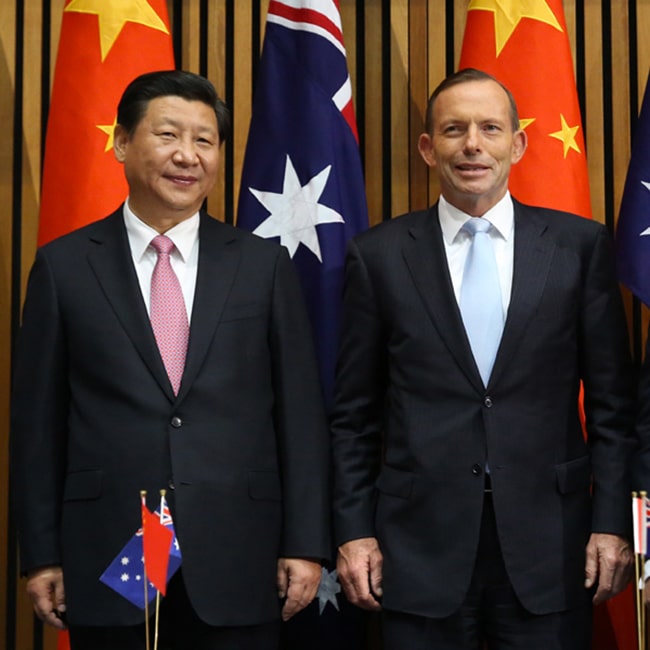

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard 17 SEP 2020

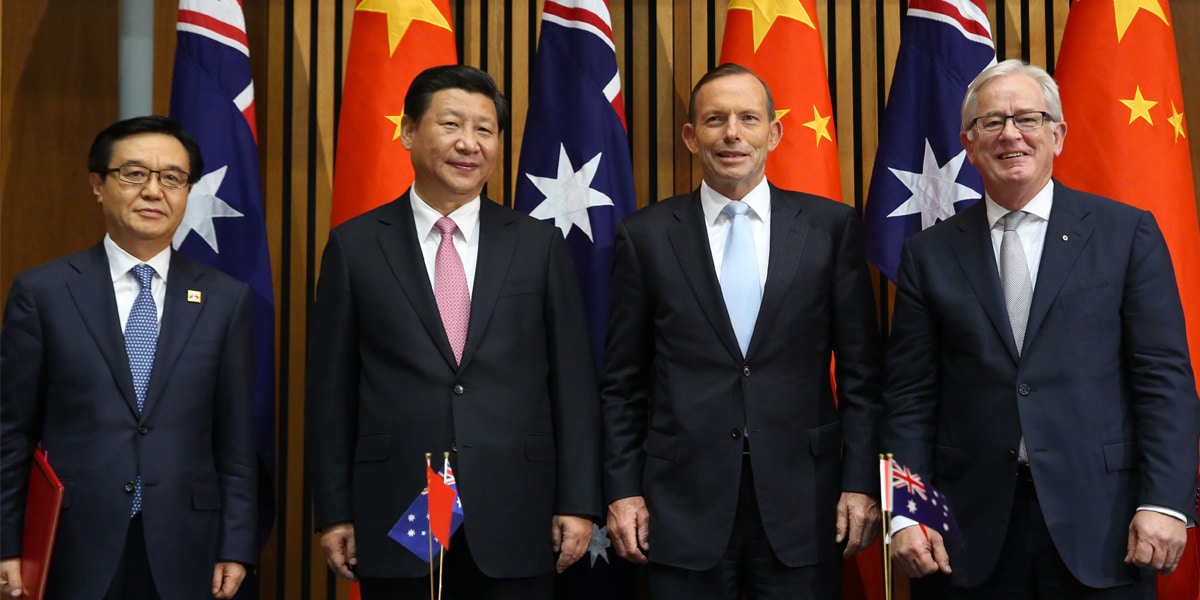

Former Aussie PM Tony Abbott’s recent appointment to an unpaid role as a trade adviser to the Johnson government in the UK has sparked controversy in both countries.

UK government MPs have continually been asked what it means to have a man who is, by the judgement of many in both countries, “a misogynist and a homophobe”, as well as a climate change denier and – more recently – sceptical about coronavirus lockdown measures.

In Australia, politicians, journalists and citizens have all questioned the appropriateness of a former Prime Minister accepting a position that leaves him serving a foreign government. Whilst Abbott has obligations under the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme that are designed to prevent conflicts of interest, there are many who believe Abbott is equipped with too much internal knowledge of Australia’s trade interests, internal party politics and regional issues in the Pacific – accrued as Prime Minister – for him to serve another government.

Given the range of questions that arise around both conflict and character, we made a list of some of the big ethical questions the Abbott situation brings up, and spoke to a few ethicists to help answer them.

1. Abbott is a private citizen now. Shouldn’t he be able to take any job he wants?

“Being Prime Minister isn’t like any other job,” says Hugh Breakey, a Senior Research Fellow at Griffith University’s Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law. “Abbott would have been privy to high level information and forward planning that he is obligated to hold secret.” If a potential employer of Abbott – whether in a paid role or not – would benefit from this situation, Breakey argues that it would give Abbott a conflict of interests.

But it’s not just a question of conflicts of interest. In situations like this, it is reasonable to consider whether this role was given as a “kind of payback for favourable treatment during his time in power,” Breakey says.

However, whilst Abbott’s appointment may generate potential conflicts of interest and are “legitimate lines of ethical inquiry”, Breakey believes they are not problems for Abbott’s appointment.

However, Simon Longstaff, executive director of The Ethics Centre, disagrees. “There just can be no guarantee that Britain’s interests will always coincide with Australia’s. Given this, the fact that one of our former Prime Ministers would ever serve a foreign power almost beggar’s belief,” he said.

2. If Abbott’s trade qualifications make him a good candidate, should we overlook his other beliefs and opinions?