We are pitching for your pledge

In celebration of our 30th anniversary which kicks off in November this year, we are preparing our very first live-crowdfunding ‘Pitch + Pledge’ night on Thursday 14 November.

Meet and hear directly from leaders of three of our flagship programs: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Ethi-call and our Young Philosopher initiative. Each speaker will pitch live on stage for six minutes each, and then answer the audiences questions. What follows is an unforgettable live-pledging experience, based on The Funding Network’s popular format.

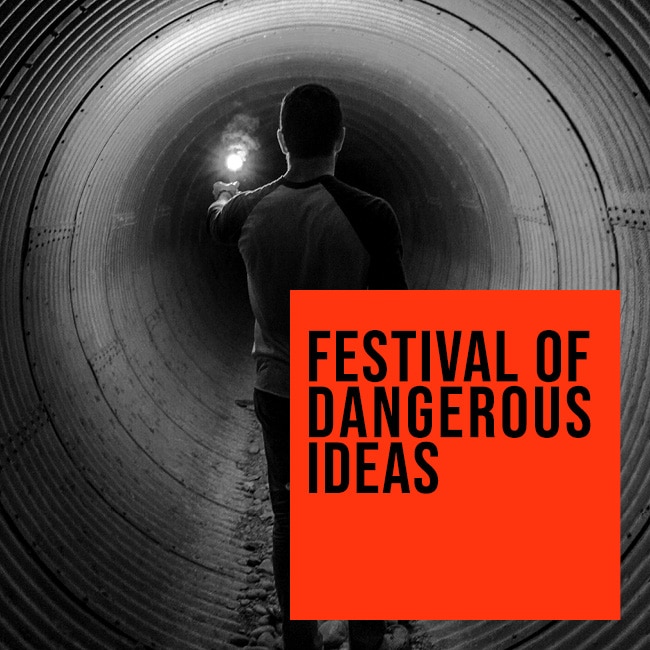

1. Support a Truly Independent Festival of Dangerous Ideas

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas is Australia’s original big thinking festival – bringing leading minds from around the world to explore life’s most problematic and divisive issues.

Delivered in partnership with Sydney Opera House for almost a decade, last year marked the start of an exciting new phase for FODI as we branched out on our own. The 2018 festival was a triumphant sell-out, and audiences told us they walked away with a feast of new ideas and perspectives.

While FODI is well-attended and widely loved, it’s also a hugely risky and expensive event to stage. Our insistence on finding the best international storytellers, and keeping ticket prices affordable for broad audiences, pushes us into uncomfortable financial territory.

Your support will help us stage FODI as a break-even event, and allow us to keep doing it, year after year.

2. Help Us Reach More People in Need with Ethi-call

We’re enormously proud of Ethi-call. It’s our free, independent, national helpline available to all. The service provides expert and impartial guidance to help people make their way through life’s toughest challenges, when there’s nowhere else to turn.

Calls can be about almost anything – from professional issues (fraud, corruption, conflicts of interests) through to the deeply personal (birth, death, relationships, families).

There’s no other service like Ethi-call, so we receive calls from all over Australia, and all over the world. Your assistance will allow us to train more counsellors and ensure more people in need know the service exists.

3. Fund a Young Philosopher

Thirty years ago, a young philosopher with a keen interest in ethics and democracy, Dr Simon Longstaff, was appointed as The Ethics Centre’s first employee and Executive Director – a position he continues to hold today.

We’ve engaged a number of budding minds over the years to bring fresh thinking to our work, most recently Dr Matthew Beard, who plays an increasingly vital role in what we do.

We’re seeking funding to secure another bright young philosopher into our team – to apply their learnings to deliver insights and tools to help people build the skills and capacity to live according to their values and principles.

An opportunity to create a ripple effect of change

It will be a highly engaging and memorable evening for everyone involved and is an opportunity for you to get involved in some very exciting, critical projects here at The Ethics Centre.

We are putting our hearts and work on the line for your support. Pitch and Pledge will kick off at 5.30pm Thursday 14 November, at Clayton Utz offices, 1 Bligh St Sydney. Pledging starts from $100.

Please RSVP to rosemary.smithson@ethics.org.au with your details and your guests’ names to book your place to join us.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Raewyn Connell The Ethics Centre 15 OCT 2019

If we ask the question, ‘are men fragile?’ my answer would be that quite a number certainly are.

We can see this in the health data. Men, compared with women, have higher levels of some kinds of mental health problem – especially alcoholism and sociopathic disorders. Men, again compared with women, have higher levels of occupational injury and coronary heart disease, higher rates of completed suicide, and – especially young men – much higher rates of injury and death on the road.

These are all long-standing patterns, and society should provide support in the form of men’s health programmes. We should also ask why these patterns exist – given that men’s bodies are not notably weaker than women’s bodies. Which leads us to the question of masculinity.

If we ask the question, ‘is masculinity fragile?’ the answer looks different. Masculinity is a social pattern, and our societies usually define its hegemonic form in terms of power, aggression, wealth and authority. So it’s mainly men who are recruited to run the world.

We may celebrate a first female leader of some country or firm, but the enormous majority of Presidents, Prime Ministers and CEOs are actually blokes in suits. (93.4% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 corporations this year, for instance.) There have not been all that many women Popes, archbishops, chief muftis, abbots, generals, admirals, Treasurers or Directors of the CIA.

There’s a robust social basis for these patterns. Part of it is economic – for the real “gender gap”, look at the superannuation statistics. Part of it is institutional – even in our lovely universities, four-fifths of full professors are blokes, though admittedly some of them don’t wear suits.

Part of it is cultural – turn on the television, and you are likely to see a screen full of extremely fit young men giving a display of professional skill and force. Those who do it best become famous role models and are given a lot of money. Last year Cristiano Ronaldo took home 61 million dollars in salary from Real Madrid, plus 47 million in endorsements. And he was only the second highest paid footballer.

Of course there are other patterns of masculinity – we should really speak of masculinities in the plural. When the media speak of “toxic masculinity” they are pointing to a specific pattern of masculinity that is bidding for the dominant place by putting down alternatives. We have a spectacular example in the career of Mr Trump – it’s hard to miss the element of resentment and revenge in his story.

The patriarchal gender order is not a perfectly-functioning machine. Indeed, since the days of President Eisenhower and Sir Robert Menzies it has seen a deep erosion of legitimacy. What would they have made of the gay marriage survey! Well, we get a glimpse in the current authoritarian backlash around the world. Which goes to show, not that masculinity is fragile, but that gender orders change. They can change for the worse; I live in hope they will change for the better.

Raewyn Connell was one of the speakers at our IQ2 Debate ‘Masculinity – is it really so fragile?’. The debate took place at Sydney Town Hall Wednesday 23 October. She was joined by Catharine Lumby, Zac Seidler and David Leser. Watch the full debate here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

BY Raewyn Connell

is one of Australia’s leading social scientists, specialising in class, gender, education, global patterns in knowledge, and most prominently, masculinity. She is one of four speakers at our upcoming debate, 'Masculinity – is it really so fragile'.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 8 OCT 2019

Most people believe it is a good idea to help out others in need, if and when we can. If someone falls over in front of us, we usually stop to see if they need a hand or to check if they are OK.

Donating to charity is also considered to be helping others in need, but we may not always see the person we are helping in this case. Even so, charitable donations are viewed as praiseworthy in our society. We receive a sticker for placing spare change into a coin collection tin, and our donations are tax deductible.

Yet most people see donating to charity as a ‘nice thing to do’, but perhaps not a ‘duty’, obligation or requirement. In Kantian terms, it is ‘supererogatory’, meaning that it is praiseworthy, but above and beyond the call of duty.

However, Peter Singer defends a stronger stance. He argues that we should help others – however we can. All of us. This may look different for different people. It could involve donating money, time, signing petitions, or passing along old clothes to those who need them, for example.

If we can help, then we should, Singer argues, because it results in the greatest overall good. The small efforts of those who can do something greatly reduce the pain and suffering of those who need welfare.

In order to illustrate this argument, Singer provides us with a compelling thought experiment.

The ‘drowning child’ thought experiment

From his 1972 article, ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’, Singer starts with a basic principle:

“if it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems reasonable. He backs this claim up with the following concrete example:

“An application of this principle would be as follows: if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing”.

Obviously, we agree, we should save the child from drowning, even if it comes with the inconvenience and cost of ruining some of our favourite, expensive clothes and shoes. The moral ‘weight’ of saving a life far outweighs the cost in this scenario.

Yet, Singer extends this claim even further.

He notes that if we agree with this principle, then what follows from it is quite radical. If we act on the idea that we should always prevent very bad things from happening, provided we are not sacrificing anything too costly to ourselves, this makes a moral demand upon us.

The biggest implication is that, for Singer, it does not matter whether the drowning child is right in front of us, or in another country on the other side of the world. The principle is one of impartiality, universalizability and equality.

I can easily donate the cost of a new pair of shoes to a respected charitable organisation and save a life with the funds from that donation. In the same way as a moral agent would wade into the pond to rescue the drowning child, we can make some relatively small effort that prevents a very bad thing from occurring.

The ‘very bad thing’ may be that a child in a developing country starves to death or dies because their family cannot afford the treatment for a simple disease.

The expanding moral circle

Now, even for those in favour of charitable giving, some may argue that our duty to help does not extend beyond national borders. It is easier to help the child ‘right in front of us’, they may say. Our moral circle of concern includes our family and friends, and perhaps our fellow Australians.

But I am convinced by Singer’s argument that we ought to expand our moral circle of consideration to those in other countries, to those who live on planet Earth with us. The moral obligation to alleviate suffering has no borders.

And we are now most certainly ‘global citizens’. Thanks to our technology and growing awareness of what occurs around the globe, we have outgrown a nationalistic model and clearly inhabit an international world.

Global Citizens

In his 2002 book, One World: the ethics of globalisation, Singer supports the notion of the global citizen which views all human beings as members of a single, global community. The global citizen is someone who recognises others as more similar to rather than different from oneself, even while taking seriously individual, social, cultural and political differences between people.

In a pragmatic sense, global citizens will support policies that extend aid beyond national borders and cultivate respectful and reciprocal relationships with others regardless of geographical distance or other differences (such as those related to race, religion, ethnicity, disability, sexuality, or gender identification).

For a long time now, Singer has also been pointing out that we are all responsible for important issues that are affecting each and every one of us. Back in 1972, he claimed, “unfortunately, most of the major evils – poverty, overpopulation, pollution – are problems in which everyone is almost equally involved.”

And, with our technology, media and the 24 hour news cycle, we are now confronted with the pain and suffering of those distant others in ways that ensure they are immediately present to us. We can no longer claim ignorance of the help required by others, as social media brings their images and pleas directly to our handheld devices.

So, do we have an obligation to alleviate suffering wherever it is found? Does this obligation extend beyond national borders? Should we do what we can to prevent very bad things from happening, provided in doing so we do not have to sacrifice anything too drastic or comparable? (for instance, we need not reduce ourselves to the levels of poverty of those we seek to assist in doing so).

If you answered yes, then you may already think of yourself as a global citizen.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 3 OCT 2019

Over the past few weeks a lot has been written about the “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” issued by the Business Roundtable in the United States.

The Business Roundtable, an association of chief executive officers from America’s leading companies, has shifted its position on who a corporation principally serves.

The original statement, published in 1997, suggested that companies exist to serve its shareholders. The new statement, signed by 163 chief executive officers, states that “While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.”

This “stakeholder approach” to corporate responsibility is not in itself ground-breaking. Nor is it a recent invention. In Johnson and Johnson’s corporate credo developed in 1943, the company lists patients, doctors and nurses as its primary stakeholders, followed by employees, customers, communities and finally shareholders.

Indeed, the shift to a stakeholder approach may not be as profound in practice as some have suggested. Even the Business Roundtable have said that the previous statement “does not accurately describe the ways in which we and our fellow CEOs endeavour every day to create value for all our stakeholders, whose long-term interests are inseparable.”

Given this, it is possible that chief executive officers only support the stakeholder approach to the extent that it benefits both themselves and the shareholder. And we should not necessarily decry this. Adam Smith, sometimes referred to as the “father of economics”, argued that individual self-interest can produce optimal outcomes, the source of his so-called “invisible hand”.

Even Milton Friedman, the much-maligned University of Chicago economist who is often held out as being the most vocal advocate for shareholder primacy, was not ignorant to the possibility that looking after the needs of stakeholders is not necessarily at odds with generating superior returns for shareholders in the long run. Famously, Friedman wrote:

“It may well be in the long-run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects.”

However, as committed as the Business Roundtable might be, circumstances will prevail that are not supportive of the stakeholder approach. Uncompetitive markets result in companies benefiting at the expense of consumers. Seemingly sensible incentive schemes can drive perverse outcomes. And a company’s products, despite being highly valued by its customers, can have broader, deleterious consequences (fossil fuel companies producing carbon dioxide, social media companies empowering covert actors, and technology companies producing “e-waste” are three examples of the latter).

The signatories to the revamped Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation would have you believe that they can be trusted to manage these types of scenarios. We should be cautious taking them at their word. History shows that even well-intentioned chief executives find it extraordinarily difficult to drive the required change in a system where the incentives endorse the status quo. And in some cases, regardless of how hard they might try, they do not have the ability to do so. The most lucid corporate purpose statement won’t save us here.

It is therefore noteworthy that the Business Roundtable has omitted the idea of accountability from its statement. If chief executive officers are serious about serving all stakeholders, how will they be held accountable?

Milton Friedman also had something to say about this. He believed that corporations should conform “to the basic rules of society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” But more importantly, as laissez faire as he was, he acknowledged that there was a role for government to “enforce compliance” and hold those who don’t “play the game” accountable.

Arguably this is the most important piece of the puzzle. Strong public institutions that develop good policy and hold corporations accountable. It is also the piece that is currently missing.

The recent financial services Royal Commission was a demonstration of what can happen when boundaries are established but not enforced. In a recent speech delivered by Commissioner Kenneth Hayne, he asked us to “grapple closely” with what the seemingly endless calls for Royal Commissions in Australia “are telling us about the state of our democratic institutions.”

But more relevant to this essay, Commissioner Hayne also provided his view on purpose statements and industry codes in the Royal Commission’s final report. He labelled them as mere “public relations puffs”, proposing that the only way they can be effective is by making them enforceable:

“If industry codes are to be more than public relations puffs, the promises made must be made seriously. If they are made seriously (and those bound by the codes say that they are), the promises that are set out in the code … must be kept. This must entail that the promises can be enforced by those to whom the promises are made.”

To be sure, the stance taken by the Business Roundtable should be applauded. Their intentions are without question noble. But more powerful would be a description of how they are going to hold themselves accountable to the statement and create the conditions that deliver value for all their stakeholders over the long-term.

Of course, this exercise would reveal the costs (financial and otherwise) that are associated with being genuinely committed to positive outcomes for all stakeholders. For some chief executive officers, the price would be too high. And because, like all of us, chief executives have their limits, so too does self-regulation.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we can’t learn from our past (and shouldn’t try to)

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The new rules of ethical design in tech

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2019

This article was written for, and first published by Atlassian.

Because tech design is a human activity, and there’s no such thing as human behaviour without ethics.

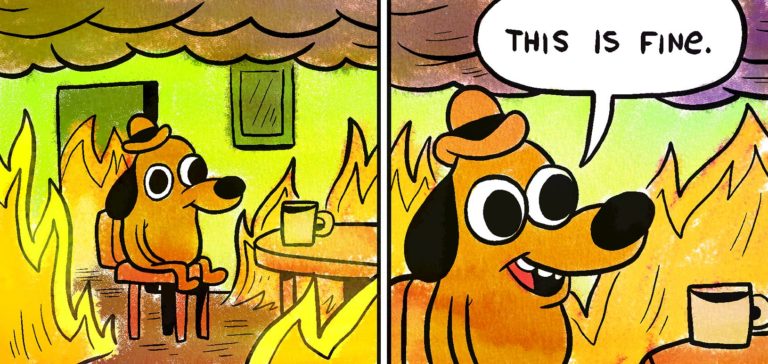

One of my favourite memes for the last few years is This is Fine. It’s a picture of a dog sitting in a burning building with a cup of coffee. “This is fine,” the dog announces. “I’m okay with what’s happening. It’ll all turn out okay.” Then the dog takes a sip of coffee and melts into the fire.

Working in ethics and technology, I hear a lot of “This is fine.” The tech sector has built (and is building) processes and systems that exclude vulnerable users by designing “nudges” that influence users, users who end up making privacy concessions they probably shouldn’t. Or, designing by hardwiring preconceived notions of right and wrong into technologies that will shape millions of people’s lives.

But many won’t acknowledge they could have ethics problems.

This is partly because, like the dog, they don’t concede that the fire might actually burn them in the end. Lots of people working in tech are willing to admit that someone else has a problem with ethics, but they’re less likely to believe is that they themselves have an issue with ethics.

And I get it. Many times, people are building products that seem innocuous, fun, or practical. There’s nothing in there that makes us do a moral double-take.

The problem is, of course, that just because you’re not able to identify a problem doesn’t mean you won’t melt to death in the sixth frame of the comic. And there are issues you need to address in what you’re building, because tech design is a human activity, and there’s no such thing as human behaviour without ethics.

Your product probably already has ethical issues

To put it bluntly: if you think you don’t need to consider ethics in your design process because your product doesn’t generate any ethical issues, you’ve missed something. Maybe your product is still fine, but you can’t be sure unless you’ve taken the time to consider your product and stakeholders through an ethical lens.

Look at it this way: If you haven’t made sure there are no bugs or biases in your design, you haven’t been the best designer you could be. Ethics is no different – making people (and their products) the best they can be.

Take Pokémon Go, for example. It’s an awesome little mobile game that gives users the chance to feel like Pokémon trainers in the real world. And it’s a business success story, recording a profit of $3 billion at the end of 2018. But it’s exactly the kind of innocuous-seeming app most would think doesn’t have any ethical issues.

But it does. It distracted drivers, brought users to dangerous locations in the hopes of catching Pokémon, disrupted public infrastructure, didn’t seek the consent of the sites it included in the game, unintentionally excluded rural neighbourhoods (many populated by racial minorities), and released Pokémon in offensive locations (for instance, a poison gas Pokémon in the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC).

Quite a list, actually.

This is a shame, because all of this meant that Pokemon Go was not the best game it could be. And as designers, that’s the goal – to make something great. But something can’t be great unless it’s good, and that’s why designers need to think about ethics.

Here are a few things you can embed within your design processes to make sure you’re not going to burn to death, ethically speaking, when you finally launch.

1. Start with ethical pre-mortems

When something goes wrong with a product, we know it’s important to do a postmortem to make sure we don’t repeat the same mistakes. Postmortems happen all the time in ethics. A product is launched, a scandal erupts, and ethicists wind up as talking heads on the news discussing what went wrong.

As useful as postmortems are, they can also be ways of washing over negligent practices. When something goes wrong and a spokesperson says, “We’re going to look closely at what happened to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” I want to say, “Why didn’t you do that before you launched?” That’s what an ethical premortem does.

Sit down with your team and talk about what would make this product an ethical failure. Then work backwards to the root causes of that possible failure. How could you mitigate that risk? Can you reduce the risk enough to justify going forward with the project? Are your systems, processes and teams set up in a way that enables ethical issues to be identified and addressed?

Tech ethicist Shannon Vallor provides a list of handy premortem questions:

- How Could This Project Fail for Ethical Reasons?

- What Would be the Most Likely Combined Causes of Our Ethical Failure/Disaster?

- What Blind Spots Would Lead Us Into It?

- Why Would We Fail to Act?

- Why/How Would We Choose the Wrong Action?

What Systems/Processes/Checks/Failsafes Can We Put in Place to Reduce Failure Risk?

2. Ask the Death Star question

The book Rogue One: Catalyst tells the story of how the galactic empire managed to build the Death Star. The strategy was simple: take many subject matter experts and get them working in silos on small projects. With no team aware of what other teams were doing, only a few managers could make sense of what was actually being built.

Small teams, working in a limited role on a much larger project, with limited connection to the needs, goals, objectives or activities of other teams. Sound familiar? Siloing is a major source of ethical negligence. Teams whose workloads, incentives, and interests are limited to their particular contribution seldom can identify the downstream effects of their contribution, or what might happen when it’s combined with other work.

While it’s unlikely you’re secretly working for a Sith Lord, it’s still worth asking:

- What’s the big picture here? What am I actually helping to build?

- What contribution is my work making and are there ethical risks I might need to know about?

- Are there dual-use risks in this product that I should be designing against?

- If there are risks, are they worth it, given the potential benefits?

3. Get red teaming

Anyone who has worked in security will know that one of the best ways to know if a product is secure is to ask someone else to try to break it. We can use a similar concept for ethics. Once we’ve built something we think is great, ask some people to try to prove that it isn’t.

Red teams should ask:

- What are the ethical pressure points here?

- Have you made trade-offs between competing values/ideals? If so, have you made them in the right way?

- What happens if we widen the circle of possible users to include some people you may not have considered?

- Was this project one we should have taken on at all? (If you knew you were building the Death Star, it’s unlikely you could ever make it an ethical product. It’s a WMD.)

- Is your solution the only one? Is it the best one?

4. Decide what your product’s saying

Ever seen a toddler discover a new toy? Their first instinct is to test the limits of what they can do. They’re not asking What was the intention of the designer, they’re testing how the item can satisfy their needs, whatever they may be. In this case they chew it, throw it, paint with it, push it down a slide… a toddler can’t access the designer’s intention. The only prompts they have are those built into the product itself.

It’s easy to think about our products as though they’ll only be used in the way we want them to be used. In reality, though, technology design and usage is more like a two-way conversation than a set of instructions. Given this, it’s worth asking: if the user had no instructions on how to use this product, what would they infer purely from the design?

For example, we might infer from the hidden-away nature of some privacy settings on social media platforms that we shouldn’t tweak our privacy settings. Social platforms might say otherwise, but their design tells a different story. Imagine what your product would be saying to a user if you let it speak for itself.

This is doubly important, because your design is saying something. All technology is full of affordances – subtle prompts that invite the user to engage with it in some ways rather than others. They’re there whether you intend them to be or not, but if you’re not aware of what your design affords, you can’t know what messages the user might be receiving.

Design teams should ask:

- What could a infer from the design about how a product can/should be used?

- How do you want people to use this?

- How don’t you want people to use this?

- Do your design choices and affordances reflect these expectations?

- Are you unnecessarily preventing other legitimate uses of the technology?

5. Don’t forget to show your work

One of the (few) things I remember from my high school math classes is this: you get one mark for getting the right answer, but three marks for showing the working that led you there.

It’s also important for learning: if you don’t get the right answer, being able to interrogate your process is crucial (that’s what a post-mortem is).

For ethical design, the process of showing your work is about being willing to publicly defend the ethical decisions you’ve made. It’s a practical version of The Sunlight Test – where you test your intentions by asking if you’d do what you were doing if the whole world was watching.

Ask yourself (and your team):

- Are there any limitations to this product?

- What trade-offs have you made (e.g. between privacy and user-customisation)?

- Why did you build this product (what problems are you solving?)

- Does this product risk being misused? If so, what have you done to mitigate those risks?

- Are there any users who will have trouble using this product (for instance, people with disabilities)? If so, why can’t you fix this and why is it worth releasing the product, given it’s not universally accessible?

- How probable is it that the good and bad effects are likely to happen?

Ethics is an investment

I’m constantly amazed at how much money, time and personnel organisations are willing to invest in culture initiatives, wellbeing days and the like, but who haven’t spent a penny on ethics. There’s a general sense that if you’re a good person, then you’ll build ethical stuff, but the evidence overwhelmingly proves that’s not the case. Ethics needs to be something you invest in learning about, building resources and systems around, recruiting for, and incentivising.

It’s also something that needs to be engaged in for the right reasons. You can’t go into this process because you think it’s going to make you money or recruit the best people, because you’ll abandon it the second you find a more effective way to achieve those goals. A lot of the talk around ethics in technology at the moment has a particular flavour: anti-regulation. There is a hope that if companies are ethical, they can self-regulate.

I don’t see that as the role of ethics at all. Ethics can guide us toward making the best judgements about what’s right and what’s wrong. It can give us precision in our decisions, a language to explain why something is a problem, and a way of determining when something is truly excellent. But people also need justice: something to rely on if they’re the least powerful person in the room. Ethics has something to say here, but so do law and regulation.

If your organisation says they’re taking ethics seriously, ask them how open they are to accepting restraint and accountability. How much are they willing to invest in getting the systems right? Are they willing to sack their best performer if that person isn’t conducting themselves the way they should?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson’s B Team

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Agape

How many people do you think we can love? Can we love everyone? Can we love everyone equally? The answers to these questions obviously depend on what the nature of this kind of love is, and what it looks like or demands of us in practice.

“Love is all you need”

Agape is a form of love that is commonly referred to as ‘neighbourly love’, the love ethic, or sometimes ‘universal love’. It rests on the idea that all people are our ‘brothers and sisters’ who deserve our care and respect. Agape invites us to actively consider and act upon the interests of other people, in more-or-less the same proportion as you consider (and usually act upon) your own interests.

We can trace the concept back to Ancient Greece, a time in which they had more than one word to describe various kinds of love. Commonly, useful distinctions can be made between eros, philia, and agape.

Eros is the kind of love we most often associate with romantic partners, particularly in the early stages of a love affair. It’s the source of English words like ‘erotic’ and ‘erotica’.

Philia generally refers to the affection felt between friends or family members. It is non-sexual in nature and usually reciprocal. It is characterised by a mutual good will that manifests in friendship.

Although both eros and philia have others as their focus, they can both entail a kind of self-interest or self-gratification (after all, in an ideal world our friends and lovers both give us pleasure).

Agape is often contrasted to these kinds of love because it lacks self-interest, self-gratification or self-preservation. It is motivated by the interest and welfare of all others. It is global and compassionate, rather than focussed on a single individual or a few people.

Another significant difference between agape and other forms of love is that we choose and cultivate agape. It’s not something that ‘happens’ to us like becoming a friend or falling romantically in love, it’s something we work toward. It is often considered praiseworthy and holds the lover to a high moral standard.

Agape is a form of love that values each person regardless of their individual characteristics or behaviour. In this way it is usually contrasted to eros or philia, where we usually value and like a person because of their characteristics.

Agape in traditional texts

The concept of agape we now have has been strongly influenced by the Christian tradition. It symbolises the love God has for people, and the love we (should) have for God in return. By extension, if we love our ‘neighbours’ (others) as we do God, then we should also love everyone else in a universal and unconditional manner, simply because they are created in the likeness of God.

The Jesus narrative asks followers to act with love (agape) regardless of how they feel. This early Christian ethical tradition encourages us to “love thy neighbour as thyself”. In the Buddhist tradition K’ung Fu-tzu (Confucius) similarly says, “Work for the good of others as you would work for your own good.”

Another great exponent of this ethic of love is Mahatma Gandhi who lived, worked, and died to keep this transcendent idea of universal love alive. Gandhi was known for saying, “Hate the sin, love the sinner”.

Advocates for non-violent resistance and pacifism that include Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lennon and Yoko Ono also refer to the power of love as a unifying force that can overcome hate and remind us of our common humanity, regardless of our individual differences.

Such ideology rests on principles that are resonant with agape, urging us to love all people and forgive them for whatever wrongs we believe they have committed. In this way, agape sets a very high moral standard for us to follow.

However, this idea of generalised, unconditional love leaves us with an important and challenging question: is it possible for human beings to achieve? And if so, how far may it extend? Can we really love the whole of humanity?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946—present), one of world’s most influential living philosophers, is best known for applying rigorous logic to a range of practical issues from animal rights, giving to charity to the ethics of abortion and infanticide.

Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946 to Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivors. As a teen he declared his atheism and refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. After studying law, history and philosophy at Melbourne University, he won a scholarship to Oxford University, writing his thesis on civil disobedience. In 1996 he ran unsuccessfully for the Greens in the Victorian State Parliament, and he has held posts at Melbourne, Monash, New York, London and Princeton Universities. His impact on public debate and academic philosophy cannot be overstated.

A key aspect of Singer’s contributions is the idea of ‘equal consideration of interests’. This informs both his views towards animals and charity. It means that we should consider the interests of any sentient beings who have the capacity to suffer and feel pleasure and pain.

Singer is a consequentialist, which means he defines ethical actions as ones that maximise overall pleasure and reduce overall pain. Part of what makes him such a challenging and influential thinker is his application of utilitarianism to real-world problems to offer counter-intuitive yet compelling solutions.’

Are you speciesist?

While at Oxford, Singer recalls a conversation with a friend over lunch that was the “most formative experience of [his] life”. Singer had the meat spaghetti, whereas his friend opted for the salad. His friend was the “first ethical vegetarian” he’d met. Two weeks later, Singer became a vegetarian and several years later published his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975).

Singer’s argument for not eating meat is more-or-less the same as another utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham wrote that “the question is not can they reason or can they talk, but can they suffer?” Similarly, Singer argues that animals have the capacity to suffer. Just as we rightly condemn torture, we should also condemn practices like factory farming that inflict unjustifiable pain on non-human animals. He coined the term ‘speciesism’ to describe the privileging of humans over other animals.

Giving to charity

In Singer’s essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (1972), he argues that people in rich countries have a moral obligation to give to charities that help people in poverty overseas. He uses an analogy of a drowning child: if we were walking past a shallow pond and saw a child drowning, we would wade in and save the child, even if this meant wrecking our favourite and most expensive pair of shoes. Likewise, because we know there are children dying overseas from preventable poverty-related diseases, we should be giving at least some of our income to charities that fight this.

Opponents to Singer argue that his view about giving to charity is psychologically untenable, and that there are differences between giving to charity and saving a drowning child. For example, the physical act of pulling a child out from water is more morally compelling than sending a cheque overseas. Other arguments include: we don’t know the child will definitely be saved when we send the cheque, fighting poverty requires a collective global effort not just an individual donation, and charities are ineffective and have high overhead costs.

Singer concedes that there may be psychological reasons why people would save the drowning child yet don’t give much to charity, but he says even if it seems strange, rationally there are no relevant moral differences between the cases.

Responding to the criticism that charities may not be effective has led Singer to be a proponent of ‘effective altruism’. In his book The Most Good You Can Do (2015) he describes how a number of charity evaluators can recommend the most cost-effective way to do good. Singer recommends giving on a progressive scale, depending on one’s income.

Instead of pursuing careers in academia, some of Singer’s brightest past students have decided to work for Wall Street to make as much money as possible to then give this away to effective charities.

Controversy around infanticide

Singer has faced sustained criticism and protest throughout his career for his views on the sanctity of life and disability – especially in Germany, where in the 90’s, his views were compared to Nazism and university courses that set his books were boycotted. While he has always been a staunch supporter of abortion on the grounds that a foetus lacks self-consciousness and the criteria of personhood, he argues there is no moral difference between abortion in the womb and killing a newborn. Furthermore, because a newborn cannot yet be classified as a person, if its parents do not want it to survive, or if it has an extreme disability meaning that keeping it alive would be very costly, there is potential justification in killing it.

Religious sanctity-of-life critics argue that Singer’s ethics ignore the fundamental sanctity of human life. Disability rights advocates argue that Singer’s views are ableist, explaining that the quality of life of a disabled person is less than that of a non-disabled person ignores the socially-constructed nature of disability – its harms and inconveniences are largely because the built environment is made for able-bodied people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why purpose, values, principles matter

Why purpose, values, principles matter

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 13 AUG 2019

In advising organisations about ethics and culture, our Ethics Centre consultants often start by asking a simple question: “Do you have an ethical framework?” What we’re trying to understand is whether the company has a well-defined purpose, supported by values and principles. It’s the bedrock upon which every successful and well-run company is built.

Over the last twenty years we have witnessed a veritable roll call of organisations who have faced an ethics crisis. And for some, this crisis has threatened their very existence. And while the individual factors will vary, there is often one underlying root cause of this failing – a drift from the organisation’s ethics framework.

An ethics framework is a critical foundation for any organisation. It expresses their purpose, values and principles – quite literally, what they believe in and what standards they’ll uphold. In making these visible, as well as living across everything they do, it allows the organisation to be the best possible version of itself, now and into the future.

If an ethics framework is practically useful, it will provide a way to diagnose ethics failure, apportion responsibility and offer a means to provide justice for victims. However, this is merely the minimum standard. It also provides the ideal that should be strived for.

An ethics framework demands something more than mere compliance. It asks employees to exercise judgement and accept personal responsibility for the decisions they make. In order to be effective, it must be consistently embraced by every member of the organisation.

- Values tell us what’s good – they’re the things we strive for, desire and seek to protect.

- Principles tell us what’s right – outlining how we may or may not achieve our values.

- Purpose is our reason for being – it gives life to our values and principles.

The power of a good ethics framework

A strong ethics framework will unite an organisation’s workforce under a common goal, creating a far better workplace culture in the process. It will help leaders make decisions that are consistent with purpose, and improve decision-making capacity across the organisation. It supports a company to be more adaptable to change and clearly demonstrates to clients, customers and other stakeholders what they stand for and where they’re headed.

A company will struggle to develop consistent workplace policies or a corporate strategy without an ethics framework. But the reverse is also true: with an ethics framework all of these processes become far easier to navigate.

Purpose

In designing an ethics framework, much is made of purpose statements – primarily because they tend to be the most visible, public-facing feature of the framework. Creating a great purpose statement is something of an art form, it needs to achieve a great deal in a few words. It should be inspiring, have an aspirational quality, and capture the essence of your company’s ‘why?’.

Ideally, purpose statements should describe how your company is satisfying a need in society or in the market. Examples include Disney’s “To make people happy” or technology powerhouse Atlassian “To unleash the power in every team”. We’re quite proud of The Ethics Centre’s purpose statement which is “To bring ethics to the centre of everyday life.”

Values and principles

Values and principles enable employees to distinguish between what is regarded as important and the means by which they should be pursued. They help to frame business activity to ensure it stays true to its purpose and contract with society. A good framework will be;

- Stable – will not change significantly (in its essence) over the long term

- Understandable – by all of those required to apply it in practice

- Practical – able to be applied in practice and with consistency

- Authentic – it will ‘ring true’.

Good for business

Having an ethics framework isn’t designed to maximise profits – it’s designed to protect and improve the relationship between business and society. But it does often benefit business as a commercial enterprise as well. By motivating employees and demonstrating the value and purpose of the business to them, they serve as ambassadors for the organisation.

Although purpose statements, corporate values and organisational principles aren’t a guarantee of perfect ethical conduct, they are a crucial ingredient in building a culture in which bad behaviour is discouraged and dis-incentivised. They’re also a flag of goodwill to stakeholders that an organisation is looking to serve humanity and not simply turn a quick buck.

Ethics frameworks are not magic bullets to solve an organisation’s problems – they won’t guarantee that all employees will do the right thing every time. But approached with the proper degree of care and sophistication, the very process of developing these codes can have a profoundly positive effect on the culture of an enterprise. In establishing the things you believe in and identifying the behaviours you wish to encourage, you establish a framework for a great corporate culture – one based on respect, trust, collaboration and accountability. And who wouldn’t want that?

Creating an ethics framework

It may surprise you to learn that many companies have no ethics framework at all. And of those that do, many are working with largely meaningless statements that offer little in the way of guidance. Some were written decades ago. Some were cooked up by marketing strategists as part of a corporate branding exercise. Whatever their provenance, there’s a sense that the framework has ceased to have any meaning for the people who work at the company.

Developing an ethics framework is only the starting point. Ensuring the framework is fully embedded and understood throughout an organisation and lived by its people is the harder challenge. Over three decades of consulting work, we’ve helped countless organisations to develop and embed their ethics frameworks. We’ve worked across multiple sectors and with companies of many shapes and sizes.

If you’d like to talk to The Ethics Centre about creating an ethical framework for your organisation, we’d love to hear from you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to spot an ototoxic leader

How to spot an ototoxic leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 13 AUG 2019

We all know about toxic leaders. There are plenty of them around. Some are especially skilled with the ability to use their words to grind down anyone they perceive as a threat.

I call these leaders ototoxic – named after the medical description of drugs that cause adverse reactions to the ears’ cochlea or auditory nerves.

Ototoxicity is a distinctive quality of a poor leader, who can leave a trail of damage.

Ototoxic leaders betray themselves by a number of logical fallacies – hallmarks of their communication style. US President Donald Trump has given us plenty of examples during his presidency.

They play the person not the argument

The ototoxic leader will go after a person’s character or pick on a personal trait. They take aim at anything personal, but will avoid addressing the logical merits of the argument. This is known as an ad hominem fallacy.

Donald Trump critiqued fellow Republicans – “Lyin’ Ted” (Cruz), “Lil’ Marco” (Rubio), “Low Energy Jeb” (Bush). There were also repeated references to “Crooked Hillary”. He repeatedly accused opponents of being “too aggressive”, (usually a woman) or “not forceful enough” (usually a man), or in the case of “Lil’ Bob” Corker, of not being “tall” enough to be taken seriously.

They use straw-man arguments

An ototoxic leader will also exaggerate, or blatantly fabricate, an opposing point of view. This allows them to position their perspective as more reasonable and practical. In the third presidential debate before his election, Trump accused Hillary Clinton of advocating an open border policy, misquoting comments she made in relation to free trade. In a climate of widespread national hostility towards immigration, the border wall seemed to many as the more reasonable option.

In the workplace, an ototoxic leader will use overblown rhetoric to belittle someone else’s initiative, exaggerating potential cost overruns or overstating other risks in order to then position their proposal as the more reasonable one.

They appeal to hypocrisy

This defensive strategy turns an initial criticism back on the accuser. Trump used this rhetorical flourish during his presidency after refusing to face criticisms that he didn’t take a position on the violence following the Charlottesville rally. Rebutting the criticisms of neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, Trump maintained that ‘many others’ had also done bad things, implying they were equally culpable.

In the workplace, an ototoxic leader can often be heard defending their actions using the appeal to hypocrisy. “You think I’m aggressive? What about that meeting last week when you didn’t agree with me? You were just as bad, if not worse!”

They use the firefighter arsonist tactic

Named after the rare syndrome where firefighters light fires intentionally only to later arrive as a hero to put it out, the ototoxic leader will overly dramatise a potential problem, at the same time pointing the finger of blame at others for causing it. Once the situation reaches a critical mass, the ototoxic leader will then step in with a last-minute solution, ‘saving the day’.

Trump is well versed in this tactic. Stoking anti-Muslim sentiment as early as March 2011 with his calls for then President Obama to show his birth certificate and trading on unfounded ‘birther’ claims, Trump proceeded to inflame fears throughout the election campaign. He threatened the mass deportation of Syrian asylum seekers while promising to create a database of all Muslims in the US, along with making false claims of seeing ‘thousands and thousands’ of people in New Jersey celebrating the collapse of the World Trade Centre Towers in 2001. Trump stepped in to solve the ‘problem’ by signing his two travel bans within the first 100 days of his tenure.

More recently, Trump repeatedly covered himself in glory after meeting Kim Jong-un at their historic first summit in June 2018. Mere months after painting Kim as “Little Rocket Man” who, according to Trump posed the greatest threat to Western civilisation and was enabled by his predecessors who “should have been handled a long time ago”, following the summit Trump celebrated the “success” of the meeting. He waxed lyrical about the leaders “tremendous” relationship, including the beautiful “love letters” he received from the North Korean dictator in the lead up to the summit, while going on to extol the virtues of Kim, including his “great personality”, his sense of humour, intelligence and his negotiation abilities. Following the script of the hero who rides in to save the day, Trump tweeted that “everybody can now feel much safer than the day I took office…there is no longer a nuclear threat from North Korea.”

In the workplace, the ototoxic leader will spark a flame of disquiet around a project or strategy then proceed to escalate concerns – often through back channel politics – before presenting a grand ‘solution’ that saves the day.

Passive and aggressive

Ototoxic leaders can be aggressive or passive. The actively toxic communicator, who uses aggressive and intimidating language to subordinate others, can be bombastic, opinionated and openly dismissive of those who have different views. Their default mode of questioning almost exclusively involves closed questions (yes or no). Their inability to be open and listen to other’s views is usually a symptom of their lack of empathy.

The passive ototoxic leader is no less poisonous. In one-on-one settings, they are an impatient listener and will quickly interrupt their interlocutor in order to express their own view, often cutting the other person off in mid-sentence.

This ototoxic leader will tend to become frustrated in meetings if the consensus view is running contrary to theirs, to the point they will actively disengage from what’s going on in the room. They will resist all attempts to re-engage them by looking to shut down the conversation wherever possible.

Energy suckers

The net effect of the ototoxic leader’s tactics and communication style is to de-energise those they come into contact with.

Research shows that these de-energising ties have a disproportionate impact on an organisation’s culture. They are a ‘toxicity multiplier’, reducing the levels of individual performance, employee engagement and general well-being.

A disproportionate level of conflict between teams is generated and trust decreases. Rather than investing the energy to achieve their goals, those who work under an ototoxic leader spend a disproportionate amount of time analysing the relationship and devising strategies to palliate the person.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The 6 ways corporate values fail

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Georg Kell on climate and misinformation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 AUG 2019

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI), Australia’s original provocative ideas festival, returns in 2020 for its 10th festival. April 3 to 5 will be a milestone weekend of provocation, contemplation, critical thinking and preparation for the battles of the next decade.

Presented by The Ethics Centre, FODI 2020 will once again feature leading thinkers from Australia and around the world to interrogate the issues of today and prepare for the major shifts of tomorrow.

FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey said: “Over the past decade the number of avenues for people to talk and share their opinions has steadily increased, we are more connected than ever with like-minded people, but the cost has been significant. We are losing the ability to listen.

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before.”

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before. The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has always been an opportunity for deep thinking, carving out precious space for disagreement, difference of opinion and critical thinking.

“As we brace for 2020, FODI will celebrate its 10th anniversary by looking again to the future and presenting a cohort of FODI alumni, representing the world’s best thinkers, journalists, creators and specialists, giving Sydneysiders an opportunity to listen to what will be shaping the world tomorrow.”

The Ethics Centre Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff said:

“The Ethics Centre is thrilled to once again be presenting the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. One of The Ethics Centre’s strategic priorities is to build and sustain the ‘ethical infrastructure’ that underpins a free, dynamic and democratic society.

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear.”

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear. FODI tests the truth of the claim that we are a ‘civil’ society – and proves that even in moments of profound disagreement – we have the strength to live an ‘examined life’.”

Last year’s sell-out festival featured Stephen Fry, Rukmini Callimachi, Niall Ferguson, Megan Phelps-Roper, Chuck Klosterman and Toby Walsh.

More information, including the full program and festival venue, will be announced in the coming months. Visit festivalofdangerousideas.com to subscribe to be the first to hear our news.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING